Dick Cheney

Richard Bruce Cheney | |

|---|---|

| |

| 46th Vice President of the United States | |

| Assumed office January 20, 2001 | |

| President | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Albert Gore, Jr. |

| 17th United States Secretary of Defense | |

| In office March 21, 1989 – January 20, 1993 | |

| President | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Frank Carlucci |

| Succeeded by | Les Aspin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 30, 1941 Lincoln, Nebraska |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Lynne Cheney |

Richard Bruce Cheney (born January 30, 1941) is the 46th and current Vice President of the United States, serving under President George W. Bush. Previously, he served as White House Chief of Staff, member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Wyoming, and Secretary of Defense. In the private sector, he was the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Halliburton Energy Services; he is still a major stockholder. On June 29, 2002, he briefly assumed the duties and responsibilities of the President when Bush underwent a medical exam involving anesthetics.

Early life and family

Cheney was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, to Richard Herbert Cheney and Marjorie Dickey. As a child, he attended Calvert Elementary School[1][2] before his family moved to Casper, Wyoming[3] where he attended Natrona County High School. His father worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture as a soil conservation agent. He has a brother, Robert, and a sister, Susan. He briefly studied at Yale University, but left after performing poorly academically. He earned his bachelor's and master's of arts degrees from the University of Wyoming.[3]

In 1964, he married Lynne Vincent, his high-school sweetheart, whom he had met at age fourteen. Mrs. Cheney served as Chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities from 1986 to 1996. She is now a public speaker, author, and a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Cheney has two children, Elizabeth and Mary, and five grandchildren. Elizabeth, his eldest daughter, is married to Philip J. Perry, General Counsel of the Department of Homeland Security. Mary is one of her father's top campaign aides and closest confidantes; she currently lives in Great Falls, Virginia. Her sexual orientation as a lesbian has become a source of increasing public attention for Dick Cheney in light of the same-sex marriage debate and Ms. Cheney's pregnancy. On August 25, 2004, Cheney said that same sex marriage is an issue that should be decided by individual states.[4]

Cheney attends the United Methodist Church.

Cheney and the draft

Cheney was of military age and a supporter of the Vietnam War but he did not serve in the war, applying for and receiving five draft deferments. In an interview with George C. Wilson that appeared in the April 5, 1989 issue of The Washington Post, when asked about his deferments the future Defense Secretary said, "I had other priorities in the '60s than military service."[5] There continues to be controversy involving Dick Cheney and the draft, due in part to Cheney's five draft deferments. In January 1959, when Mr. Cheney reached age 18 and was classified as 1-A — available for service — he was doing poorly at Yale. At that time, however, the military was taking only older men, and like most others who were in college at the time, Cheney had little concern about being drafted. In June 1962, Cheney left Yale to return home to Casper, where he worked as a lineman for a power company. In 1962, only 82,060 men were inducted into the service, the fewest since 1949. While Cheney was eligible for the draft, as he said during his confirmation hearings in 1989, he was not called up because the Selective Service System was taking only older men.

By January 1963, with the US actively advising South Vietnamese forces, Cheney enrolled in Casper Community College and turned 22 that month. At that time, he sought his first student deferment which was granted on March 20, according to records from the Selective Service System. After transferring to the University of Wyoming at Laramie, Cheney sought his second student deferment on July 23, 1963. On August 7, 1964, Congress approved the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, which allowed President Lyndon B. Johnson to use military force in Vietnam. From that point on, American involvement in Vietnam began to escalate rapidly.

On August 29, 1964, 22 days after the resolution, Cheney married his high school sweetheart, Lynne. He sought and was granted his third student deferment on October 14, 1964. In May 1965, Cheney graduated from college and his draft status changed to 1-A. Since he was married, however, he had somewhat better protection from being drafted. In July 1965, Johnson announced that he was doubling the number of men drafted. The number of inductions soared, to 382,010 in 1966 from 230,991 in 1965 and 112,386 in 1964. Cheney obtained his fourth deferment because he started graduate school at the University of Wyoming on November 1, 1965.

On October 6, 1965, the Selective Service lifted its ban against drafting married men who had no children. On January 19, 1966, when his wife was about 10 weeks pregnant, Mr. Cheney applied for 3-A status, the "hardship" exemption, which excluded men with children or dependent parents. It was granted. In January 1967, Cheney turned 26 and was no longer eligible for the draft.[6]

Political career

Early White House appointments

Dick Cheney's political career began in 1969, as an intern during the Nixon administration. The intern Cheney then joined the staff of Donald Rumsfeld, who was then Director of the Office of Economic Opportunity from 1969–70. He held a number of positions in the years that followed: White House staff assistant in 1971, assistant director of the Cost of Living Council from 1971–73, and Deputy Assistant to the President from 1974–1975. From 1973–1974, Cheney worked in the private sector as vice president of Bradley, Woods, and Company, an investment firm.[7]

Under President Gerald Ford, Cheney worked as Assistant to the President as Rumsfeld first oversaw Ford's White House "transition team" and then later became Ford's Chief of Staff. In what was later termed by political insiders as the "Halloween Massacre", Cheney and Rumsfeld began consolidating political power by replacing or re-assigning high-ranking government officals. An article in Rolling Stone later summed up the changes as, "Having turned Ford into their instrument, Rumsfeld and Cheney staged a palace coup. They pushed Ford to fire Defense Secretary James Schlesinger, tell Vice President Nelson Rockefeller to look for another job and remove Henry Kissinger from his post as national security adviser. Rumsfeld was named secretary of defense, and Cheney became chief of staff to the president."[8] In addition, Cheney and Rumsfeld successfuly pushed for George H. W. Bush to replace William Colby as the Director of the CIA, forging what would become a long-term relationship with the future president.

He was campaign manager for Ford's 1976 presidential campaign, while James Baker served as campaign chairman.

Congress

In 1978, Cheney was elected to represent Wyoming in the U.S. House of Representatives to replace resigning Congressman Teno Roncalio, defeating his Democrat opponent, Bill Bailey. He was Chairman of the Republican Policy Committee from 1981 to 1987 when he was elected Chairman of the House Republican Conference. The following year, he was elected House Minority Whip. Cheney was reelected five times, serving until 1989.

Among the many votes he cast during his tenure in the House, he voted in 1979 with the majority against making Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s birthday a national holiday, and again voted with the majority in 1983 when the measure passed.

He voted against the creation of the U.S. Department of Education, citing his concern over budget deficits and expansion of the federal government. He also claimed the department was an encroachment on states' rights.[9]

He also voted against funding Head Start. As a vice presidential candidate in 2000, he reversed his position.[10]

In 1986, after President Reagan vetoed a bill to impose economic sanctions against South Africa for its official policy of apartheid, Cheney was one of 83 Representatives who voted against overriding the veto. In later years, Cheney articulated his opposition to "unilateral sanctions," against many different countries, stating "they almost never work."[11] He also opposed unilateral sanctions against communist Cuba, and later in his career he would support multilateral sanctions against Iraq. However the comparison to Cuba is not exactly apt, as the European Community had voted to place limited sanctions upon South Africa in 1986.

In 1986, Cheney, along with 145 Republicans and 31 Democrats, voted against a nonbinding Congressional resolution calling on the South African government to release Nelson Mandela from prison, after the majority Democrats defeated proposed amendments to the language that would have required Mandela to renounce violence sponsored by the ANC and requiring the ANC to oust the Communist faction from leadership. The resolution was defeated. Appearing on CNN during the Presidential campaign in 2000, Cheney addressed criticism for this, saying he opposed the resolution because the ANC "at the time was viewed as a terrorist organization and had a number of interests that were fundamentally inimical to the United States."[12]

As a Wyoming representative, he was also known for his vigorous advocacy of the state's petroleum and coal businesses. The federal building in Casper, a regional center of the oil and coal business, was named the "Dick Cheney Federal Building."

House Minority Whip

In December 1988, the House Republicans elected Cheney to the second spot in the leadership, but he only served two and a half months, as he was appointed Secretary of Defense (see below) to replace chose former Texas Sen.John G. Tower, whose nomination had been rejected by the Senate.

Secretary of Defense

Cheney served as the Secretary of Defense from March 1989 to January 1993 under President George H. W. Bush. He directed the United States invasion of Panama and Operation Desert Storm in the Middle East. In 1991 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for "preserving America's defenses at a time of great change around the world."[13]

Early tenure

President George H. W. Bush initially chose former Texas Sen. John G. Tower to be his secretary of defense. When the Senate, in March, 1989, rejected his nomination, Bush selected Cheney, who was a Congressional Representative of Wyoming at the time.

Cheney generally focused on external matters and delegated most internal Pentagon management details to Deputy Secretary of Defense Donald J. Atwood, Jr. He worked closely with Pete Williams, assistant secretary of defense for public affairs, and Paul Wolfowitz, under secretary of defense for policy. For chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff he selected General Colin Powell, who assumed the post on October 1, 1989. Many of Cheney's major decisions resulted from the almost daily meetings he had in the Pentagon with Powell and Atwood.

Cheney met regularly with Bush and other top-level members of the administration, including Secretary of State James Baker, national security adviser Brent Scowcroft, White House Chief of Staff John Sununu, and General Powell. Occasionally Bush consulted with Cheney on matters unrelated to defense, such as White House organization and management. When not at the White House, Cheney was often on Capitol Hill. He understood how Congress, and more particularly the legislative process, operated, and he used this knowledge and experience to avoid the kind of difficulties Caspar Weinberger had encountered with Congress. In general Cheney got along well with Congress and with the Department of Defense's main oversight committees in the House and the Senate, though he suffered disappointments and frustrations.

Political climate and agenda

Although some of the usual turf battles between the State and Defense Departments continued during his term, Cheney and Secretary of State Baker were old friends and avoided the acrimony that sometimes occurred between the two departments during the Weinberger period. On the important problem of arms control, Cheney and Powell tried to reach consensus on Department of Defense's position in order to deal more effectively with the State Department. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Cheney worried about the dangers of nuclear proliferation and effective control of nuclear weapons from the Soviet nuclear arsenal that had come under the control of newly independent republics — Belarus, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan — as well as in Russia itself. Cheney warned about the possibility that other nations, such as Iraq, Iran, and North Korea, would acquire nuclear components after the Soviet collapse. He supported the initiatives that Bush and Russian President Boris Yeltsin took in 1991 and 1992 to cut back the production and deployment of nuclear weapons and to move toward new arms control agreements.

The end of the Cold War, the fall of the Soviet Union, and the disintegration of the Warsaw Pact obliged the Bush administration to reevaluate NATO's purpose and makeup. How to restructure the alliance and modify its strategy to reflect changes in the military situation posed major questions for Cheney. He believed that NATO had to remain the foundation of European security relationships and that it would continue to be important to the United States in the long term. At the last NATO meeting he attended, in Brussels in December 1992, Cheney said that the alliance needed to lend more assistance to the new democracies in Eastern Europe and eventually offer them membership in NATO. Central and Eastern Europe, he told his NATO colleagues, presented the most threatening potential security problems in the years ahead. The current problem, rather than East versus West, was East and West versus instability.

Cheney's views on NATO reflected his skepticism about prospects for peaceful evolution in the former Soviet areas. He saw high potential for uncertainty and instability, and he felt that the Bush administration was too optimistic in supporting Mikhail Gorbachev and his successor, Boris Yeltsin. Cheney believed that as the United States downsized its military forces, reduced its troops in Europe, and moved forward with arms control, it needed to keep a watchful eye on Russia and other successor states of the Soviet Union.

Budgetary practices

The Department of Defense budget faced Cheney with his most immediate and pressing problem when he came to the Pentagon. President Bush had already said publicly that the proposed FY 1990 Defense budget of more than $300 billion had to be cut immediately by $6.3 billion, and soon after Cheney began work the president increased the amount to $10 billion. Cheney recognized the necessity of cutting the budget and downsizing the military establishment, but he favored a cautious approach. In making decisions on the FY 1990 budget, the secretary had to confront the wish list of each of the services. The Air Force wanted to buy 312 B-2 stealth bombers at over $500 million each; the Marine Corps wanted 12 V-22 Osprey tilt-rotor helicopters, $136 million each; the Army wanted some $240 million in FY 1990 to move toward production of the LHX, a new reconnaissance and attack helicopter, to cost $33 billion eventually; and the Navy wanted 5 Aegis guided-missile destroyers, at a cost of $3.6 billion. A policy on ballistic missiles also posed a difficult choice. One option was to build 50 more MX missiles to join the 50 already on hand, at a cost of about $10 billion. A decision had to be made on how to base the MX—whether on railroad cars or in some other mode. Another option was to build 500 single-warhead Midgetman missiles, still in the development stage, at an estimated cost of $24 billion.

In April, Cheney recommended to Bush that the United States move ahead to deploy the 50 MXs and discontinue the Midgetman project. While not unalterably opposed to the Midgetman, Cheney questioned how to pay for it in a time of shrinking defense budgets. Cheney's plan encountered opposition both inside the administration and in Congress. Bush decided not to take Cheney's advice; he said he would seek funding to put the MXs on railroad cars by the mid-1990s and to develop the Midgetman, with a goal of 250 to 500.

When Cheney's FY 1990 budget came before Congress in the summer of 1989, the Senate Armed Services Committee made only minor amendments, but the House Armed Services Committee cut the strategic accounts and favored the V-22, F-14D, and other projects not high on Cheney's list. The House and Senate in November 1989 finally settled on a budget somewhere between the preferences of the administration and the House committee. Congress avoided a final decision on the MX/Midgetman issue by authorizing a $1 billion missile modernization account to be apportioned as the president saw fit. Funding for the F-14D was to continue for another year, providing 18 more aircraft in the program. Congress authorized only research funds for the V-22 and cut SDI funding more than $1 billion, much to the displeasure of President Bush.

In subsequent years under Cheney the budgets proposed and the final outcomes followed patterns similar to the FY 1990 budget experience. Early in 1991 the secretary unveiled a plan to reduce military strength by the mid-1990s to 1.6 million, compared to 2.2 million when he entered office. In his budget proposal for FY 1993, his last one, Cheney asked for termination of the B-2 program at 20 aircraft, cancellation of the Midgetman, and limitations on advanced cruise missile purchases to those already authorized. When introducing this budget, Cheney complained that Congress had directed Defense to buy weapons it did not want, including the V-22, M-1 tanks, and F-14 and F-16 aircraft, and required it to maintain some unneeded reserve forces. His plan outlined about $50 billion less in budget authority over the next 5 years than the Bush administration had proposed in 1991. Sen. Sam Nunn of the Senate Armed Services Committee said that the 5-year cuts ought to be $85 billion, and Rep. Les Aspin of the House Armed Services Committee put the figure at $91 billion.

Over Cheney's four years as secretary of defense, encompassing budgets for fiscal years 1990-93, the Department of Defense's total obligational authority in current dollars declined from $291.3 billion to $269.9 billion. Except for FY 1991, when the TOA budget increased by 1.7 percent, the Cheney budgets showed negative real growth: -2.9 percent in 1990, -9.8 percent in 1992, and -8.1 percent in 1993. During this same period total military personnel declined by 19.4 percent, from 2.202 million in FY 1989 to 1.776 million in FY 1993. The Army took the largest cut, from 770,000 to 572,000-25.8 percent of its strength. The Air Force declined by 22.3 percent, the Navy by 14 percent, and the Marines by 9.7 percent.

The V-22 question caused friction between Cheney and Congress throughout his tenure. The Department of Defense spent some of the money Congress appropriated to develop the aircraft, but congressional sources accused Cheney, who continued to oppose the Osprey, of violating the law by not moving ahead as Congress had directed. Cheney argued that building and testing the prototype Osprey would cost more than the amount appropriated. In the spring of 1992 several congressional supporters of the V-22 threatened to take Cheney to court over the issue. A little later, in the face of suggestions from congressional Republicans that Cheney's opposition to the Osprey was hurting President Bush's reelection campaign, especially in Texas and Pennsylvania where the aircraft would be built, Cheney relented and suggested spending $1.5 billion in fiscal years 1992 and 1993 to develop it. He made clear that he personally still opposed the Osprey and favored a less costly alternative.

International situations

Panama, controlled by General Manuel Antonio Noriega, the head of the country's military, against whom a U.S. grand jury had entered an indictment for drug trafficking in February 1988, held Cheney's attention almost from the time he took office. Using economic sanctions and political pressure, the United States mounted a campaign to drive Noriega from power. In May 1989 after Guillermo Endara had been duly elected president of Panama, Noriega nullified the election outcome, incurring intensified U.S. pressure on him. In October Noriega succeeded in quelling a military coup, but in December, after his defense forces shot a U.S. serviceman, 24,000 U.S. troops invaded Panama. Within a few days they achieved control and Endara assumed the presidency. U.S. forces arrested Noriega and flew him to Miami where he was held until his trial, which led to his conviction and imprisonment on racketeering and drug trafficking charges in April 1992.

Cheney took a strong stand against use of U.S. ground troops in the Bosnian War between Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks that began in April 1992. After the collapse of a collective presidency in Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, the country split into several independent republics, including the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which declared its independence in March 1992. Whether and how to intervene in Bosnia evoked an emotional debate in the United States, but Cheney left office before any firm decisions were made, and his successors inherited the knotty issue.

In Somalia also, a civil war that began in 1991 claimed the world's attention. In August 1992 the United States began to provide humanitarian assistance, primarily food, through a military airlift. In December, only a month before he left office, at President Bush's direction Cheney dispatched the first of 26,000 U.S. troops to Somalia as part of the Unified Task Force (UNITAF), designed to provide security and food relief. Cheney's successors as secretary of defense, Les Aspin and William J. Perry, had to contend with both the Bosnian and Somali issues.

Iraq invasion of Kuwait

Cheney's biggest challenge came in the Persian Gulf. On August 1, 1990, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein sent invading forces into neighboring Kuwait, a small oil-rich country long claimed by Iraq. An estimated 140,000 Iraqi troops quickly took control of Kuwait City and moved on to the Saudi Arabia/Kuwait border. Cheney regarded Iraq's intrusion into Kuwait as a grave threat to U.S. interests. The United States had already begun to develop contingency plans for defense of Saudi Arabia by the U.S. Central Command, headed by General Norman Schwarzkopf.

Shortly after the Iraqi invasion, Cheney made the first of several visits to Saudi Arabia and secured King Fahd's permission to bring U.S. troops into his country. The United Nations took action, passing a series of resolutions condemning Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, and eventually demanded that Iraq withdraw its forces by January 15, 1991. By then, the United States had a force of about 500,000 stationed in Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf. Other nations, including Great Britain, Canada, France, Italy, Syria, and Egypt, contributed troops, and other allies, most notably Germany and Japan, agreed to provide financial support for the coalition effort, named Operation Desert Shield.

In the meantime a congressional and public debate developed in the United States about whether to rely on economic sanctions against Iraq or to use military force. Bush in October 1990 settled on military action if Iraq's troops had not left Kuwait by the January 15, 1991 deadline. In November 1990 UN Resolution 678 authorized "all necessary means" to expel Iraq from Kuwait. The debate ended on January 12, 1991, when both houses of Congress agreed to a joint resolution stating that the president was to satisfy Congress that he had exhausted all means to secure Iraq's compliance with UN resolutions on Kuwait before he initiated hostilities. Cheney signed an order, not publicly released at the time, stating that the president would make the determination required by the joint resolution and that offensive operations against Iraq would begin on January 17.

As the military buildup in Saudi Arabia (Desert Shield) proceeded in the fall of 1990 and as the UN coalition moved toward military action, Cheney worked closely with General Powell in directing the movement of U.S. personnel, equipment, and supplies to Saudi Arabia. He participated intently with Powell, Schwarzkopf, and others in overseeing planning for the operation. Cheney, according to Powell, "had become a glutton for information, with an appetite we could barely satisfy. He spent hours in the National Military Command Center peppering my staff with questions." When hostilities began in January 1991, Cheney turned most other Department of Defense matters over to Deputy Secretary Atwood. Cheney spent many hours briefing Congress during the air and ground phases of the war.

In an incident in September 1990 involving General Michael Dugan, who had replaced General Welch as Air Force chief of staff, Cheney again demonstrated the primacy of civilian authority over the military. On a return flight from Saudi Arabia, in discussions with reporters about the Kuwait situation, Dugan was guilty of indiscretions that became public and could not help but invite Cheney's attention. Powell's later recollection of this episode summed up the problem: "Dugan had made the Iraqis look like a pushover; suggested that American commanders were taking their cue from Israel, a perception fatal to the Arab alliance we were trying to forge; suggested political assassination... ; claimed that air power was the only option; and said... that the American people would not support any other administration strategy." Cheney quickly decided to fire Dugan, who had been Air Force chief of staff for less than three months.

The first phase of Operation Desert Storm, which began on January 17, 1991, was an air offensive to secure air superiority and attack Iraq's forces in Kuwait and Iraq proper. Targets included key Iraqi command and control centers, including Baghdad and Basra. Iraq retaliated by firing Scud missiles against locations in Saudi Arabia and Israel. The United States used Patriot missiles to defend against the Scuds, which were old and unsophisticated, and diverted some aircraft to seek out and bomb the missile sites. The Israeli government wanted to use its own air power to hunt down and destroy Scud launch sites in western Iraq, but U.S. officials, concerned about the effect on the Arab members of the coalition, succeeded in persuading Israel not to intervene.

After an air offensive of more than five weeks, the UN coalition launched the ground war, with the first forces thrusting into Kuwait from Saudi Arabia early in the morning of February 24. Within four days Iraqi forces had been routed from Kuwait and pushed into the interior of Iraq after suffering heavy losses. Although easily defeated, Iraq's army did considerable damage while retreating, including setting fire to many oil wells. By February 27 General Schwarzkopf reported that the basic objective-expelling Iraqi forces from Kuwait-had been met. After consultation with Cheney, Powell, and other members of his national security team, Bush declared a suspension of hostilities effective at midnight on February 27, Washington time. A total of 147 U.S. military personnel died in combat, and another 236 died as a result of accidents or other causes. Iraq agreed to a formal truce on March 3, and a permanent cease-fire on April 6.

Subsequently there was debate about whether the UN coalition should have driven all the way to Baghdad to oust Saddam Hussein from power. Bush and his advisers agreed unanimously on the decision to end the ground war when they did. The UN resolutions on the war limited military action to expelling Iraq from Kuwait. Cheney thought that if the campaign continued, the invading force probably would get bogged down and suffer many casualties. The debate persisted for years after the war as Saddam Hussein remained in power, rebuilt his military forces, resisted full implementation of the cease-fire terms, and periodically threatened Kuwait.

Appearing on ABC's This Week, Cheney was asked why Operation Desert Storm had not gone "all the way" to remove Saddam Hussein from power. "I think for us to get American military personnel involved in a civil war inside Iraq would literally be a quagmire," Cheney replied. "Once we got to Baghdad, what would we do? Who would we put in power? What kind of government? Would it be a Sunni government, a Shia government, a Kurdish government? Would it be secular, along the lines of the Baath party, would it be fundamentalist Islamic? I do not think the United States wants to have U.S. military forces accept casualties and accept responsibility of trying to govern Iraq. I think it makes no sense at all."

Cheney regarded the Gulf War as the first example of the kind of regional problem the United States was likely to face in the aftermath of the Cold War. He thought the successful campaign validated the broad strategy developed under his direction. A draft Defense Planning Guidance issued early in 1992 envisioned several scenarios in which the United States might have to fight two large regional wars at one time-for example, against Iraq again, against North Korea, or in Europe against a resurgent, expansionist Russia. The Pentagon later modified this document, but it gave some indication of what the Defense Department saw as future threats to the United States.

Private sector career

With Democrats returning to the White House in January 1993, Cheney left the Department of Defense and joined the American Enterprise Institute. From 1995 until 2000, he served as Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer of Halliburton, a Fortune 500 company and market leader in the energy sector.[citation needed] Under Cheney's tenure, the number of Halliburton subsidiaries in offshore tax havens increased from 9 to 44.[14] As CEO of Halliburton, Cheney lobbied to lift U.S. sanctions against Iran and Libya, saying that unilateral moves to isolate countries damaged U.S. interests.[15] He also sat on the Board of Directors of Procter & Gamble, Union Pacific, and Electronic Data Systems.[citation needed] According to the CBC's the Fifth Estate ""During the election campaign Cheney tells ABC News. “I had a firm policy that we wouldn’t do anything in Iraq, even arrangements that were supposedly legal.”[citation needed]

However, during his time as CEO, Halliburton was selling millions of dollars to Iraq in supplies for its oil industry. The deals were done through old subsidiaries of Dresser Industries. It was done under the auspices of the corrupt UN Oil for Food Program." CBC The Fifth Estate. Link http://www.cbc.ca/fifth/dickcheney/vice.html

In 1997, he, along with Donald Rumsfeld and others, founded the "Project for the New American Century," a think tank whose self-stated goal is to "promote American global leadership". He was also part of the board of advisers of the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs (JINSA) before becoming Vice President.

He also makes a cameo in Die Hard 3 as a police official.[16]

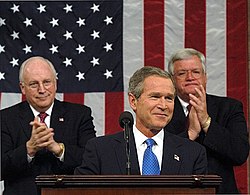

Vice-Presidency

First and second terms

In the spring of 2000, while serving as Halliburton's CEO, he headed George W. Bush's Vice-Presidential search committee. After reviewing Cheney's findings, Bush surprised pundits by asking Cheney himself to join the Republican ticket.

In the 2000 presidential election, a question was raised by the Democrats as to Cheney's state of residency since he had been living in Texas. A lawsuit was brought in Jones v. Bush attempting to invalidate electoral votes from Texas under the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment, but was rejected by a federal district court in Texas.

After taking office, Cheney quickly earned a reputation as a very "hands-on" Vice President, taking an active role in cabinet meetings and policy formation. He is often described as the most active and powerful Vice President in recent years. Some, like Kenneth Duberstein (Reagan's last Chief of Staff), have likened him to a prime minister because of his powerful position inside the Bush Administration. Bush himself has described the relationship between him and his vice president in the language of corporate governance: the president likened himself to a chief executive officer and Cheney to a chief operating officer.[citation needed]

As President of the Senate, he has cast seven tie-breaking votes to date, including deciding votes on concurring in the conference reports of the 2004 congressional budget and the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003.

Cheney directed the National Energy Policy Development Group (NEPDG)[17] commonly known as the Energy task force. Comprised by people in the energy industry, this group included several Enron executives. Because of the subsequent Enron scandal, critics accused the Bush Administration of improper political and business ties. In July 2003, the Supreme Court ruled that the Department of Commerce must make the NEPDG's documents public. The documents included information on companies that had made agreements with Saddam Hussein to develop Iraq's oil. The documents also included maps of oil deposits in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and the United Arab Emirates. The NEPDG's report contains several chapters, covering topics such as environmental protection, energy efficiency, renewable energy, and energy security. Critics focus on the eighth chapter, "Strengthening Global Alliances,"[18] claiming that this chapter urges military actions to remove strategic, political, and economic obstacles to increased U.S. consumption of oil, while others argue that the report contains no such recommendation.[citation needed]

Following the uncertainty immediately after the events of September 11, 2001, Cheney and President Bush were kept in physically distant locations for security reasons. For a period Cheney was not seen in public, remaining in an undisclosed location and communicating with the White House via secure video phones.

On the morning of June 29, 2002, Cheney became only the second man in history to serve as Acting President of the United States under the terms of the 25th Amendment to the Constitution, while President Bush was undergoing a colonoscopy. Cheney acted as President from 11:09 UTC that day until Bush resumed control at 13:24 UTC.[19][20] (See Bush transfer of power.)

In March 2003 Executive Order 13292 gave the Vice President the power to classify documents. However, the Vice President's ability to de-classify documents exists in a legal grey area and, as of 2006, remains as a point of controversy.[21]

Both supporters and opponents of Cheney point to his reputation as a very shrewd and knowledgeable politician who knows the functions and intricacies of the federal government. Opponents however accuse him of following policies that indirectly subsidize the oil industry and major campaign contributors and hold that Cheney strongly influenced the decision to use military force in Iraq. Critics state he is the leading proponent within the Bush administration of the right of the United States to use torture as part of the War on Terrorism[22] and has been lobbying Congress to exempt the CIA from Senator John McCain's proposed anti-torture bill.[23]

One sign of Cheney's active policy-making role is the fact that the Speaker of the House gave him an office near the House floor[24] in addition to his office in the West Wing, his ceremonial office in the Old Executive Office Building, and his Senate offices (one in the Dirksen Senate Office Building and another off the floor of the Senate).[25] Cheney's former chief legal council, David Addington, is currently his chief of staff.

Cheney's critics have commented on what they perceive to be his penchant for excessive secrecy. They cite his unknown whereabouts in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, his legal battle to keep the notes of his Energy Task Force meetings private, his silence in the days following his hunting incident, and even his disinclination to disclose who works in his office. "We just don't give out that kind of information," one of his aides told a reporter. "It's just not something we talk about."[26]

Controversies

DUI arrests

In November 1962 at the age of twenty-one, Cheney was convicted for the first of two offenses of driving while intoxicated (DWI). According to the docket from the Municipal Court in Cheyenne, Wyoming, Cheney was arrested for drunkenness and, "operating a motor vehicle while intoxicated." A Cheyenne Police Judge found Cheney guilty of the two charges. Cheney's driving license was suspended for 30 days and he had to forfeit a $150 bond posted at the time of his arrest.

Eight months later, in July 1963, Cheney was arrested in Rock Springs, Wyoming and fined $100 for his second DWI conviction. At the time, it was not possible for the authorities in each area to link the two convictions, which would have resulted in the second offense being viewed much more seriously. Since this arrest, Cheney has had no further documented convictions.[27]

Cheney discussed his record in a May 7, 2001, interview in The New Yorker. Cheney said that he found himself, "working, building power lines, having been in a couple of scrapes with the law."[28] He said that the arrests made him, "think about where I was and where I was headed. I was headed down a bad road if I continued on that course."[28]

Relationship to Halliburton as Vice President

Cheney has a Gift Trust Agreement pursuant to which an Administrative Agent has the right to exercise those options and distribute the proceeds from the sale of the resulting stock to certain charitable organizations.[29][failed verification] All proceeds of the options will be split between the George Washington University Medical Faculty Associates, Inc. for the benefit of the Cardiothoracic Institute, the University of Wyoming for the benefit of the University of Wyoming Foundation, and Capital Partners for Education for the benefit of low-income high school students in the Washington, D.C. area.[citation needed]

Cheney resigned as CEO of Halliburton on July 25, 2000, and put all of his corporate shares into a blind trust. As part of his deferred compensation agreements with Halliburton contractually arranged prior to Cheney becoming Vice President, Cheney's public financial disclosure sheets filed with the U.S. Office of Government Ethics showed he received $162,392 in 2002 and $205,298 in 2001.[citation needed] Upon his nomination as a Vice Presidential candidate, Cheney purchased an annuity that would guarantee his deferred payments regardless of the company's performance.[citation needed] He argued that this step removed any conflict of interest. Cheney's net worth, estimated to be between $30 million and $100 million, is largely derived from his post at Halliburton.[citation needed]

In 2005, the Cheneys reported their gross income as nearly $8.82 million. This was largely the result of exercising Halliburton stock options that had been set aside in 2001 with the Gift Trust Agreement. The Cheneys donated just under $6.87 million to charity from the stock options and royalties from Mrs. Cheney's books.[30][failed verification]

On May 17 2006 Kiplinger's Personal Finance reported that, based on Cheney's financial disclosures, his "...financial advisers are apparently betting on a rise in inflation and interest rates and on a decline in the value of the dollar against foreign currencies."[31]

Rebuilding of Iraq

Halliburton was granted a $7 billion no-bid contract, the execution of which received much scrutiny from U.S. Government auditors along with the media and various political opponents who also scrutinized the awarding of the contract, claiming that it represented a conflict of interest for Mr. Cheney. In June 2004, the General Accounting Office reviewed the contracting procedures and found Halliburton's no-bid contracts were legal and likely justified by the Pentagon's wartime needs.[32]

A few days after accusing the Vice President of cronyism regarding Halliburton, Democratic senator Patrick Leahy crossed the Senate floor to the Republican side to speak with Vice President Cheney during a Senate photo shoot. According to Cheney, Leahy was trying to "make small talk" and "act like everything's peaches and cream." Cheney ended the conversation by saying "go fuck yourself" to Leahy.[33][34] These same words were shouted at Cheney on live television on September 8, 2005, in Gulfport, Mississippi, while he was touring the destroyed neighborhood of Ben Marble, M.D. Dr. Marble said "Go fuck yourself, Mr. Cheney!"[35] in reference to Cheney's comments on the Senate floor as justification.

Plame incident

On October 18, 2005, The Washington Post reported that the Vice President's office was central to the investigation of the Plame affair. Cheney's former chief of staff, Lewis Libby, is one of the main figures under investigation. On October 28, Libby was indicted on five felony counts.[36]

On February 9, 2006, The National Journal reported that Libby had said before a grand jury that his superiors, including Dick Cheney, had authorized him to disclose classified information to the press regarding Iraq's weapons intelligence.[37] Many people believe that Cheney ordered Libby to expose Plame as a CIA agent to punish her husband for questioning the validity of White House memos asserting that Saddam Hussein sought large amounts of uranium from Niger.[citation needed]

On July 13, 2006, Plame sued the Vice President and several others because he allegedly "illegally conspired to reveal her identity."[38]

On Sept 8, 2006, Richard Armitage, former Deputy Secretary of State, publicly announced that he was the source of the revelation of Plame's status. Armitage said he was not a part of a conspiracy to reveal Plame's identity and did not know whether one existed.[39]

On December 19, 2006, news organizations reported that Vice President Dick Cheney would be called to testify as a witness for the defense during Libby's trial in January 2007.[40][41]

Hunting incident

On February 11, 2006, Cheney, reportedly, in view of six witnesses, accidentally shot Harry Whittington, a 78-year-old Texas attorney, in the face, neck, and upper torso with birdshot pellets from a shotgun when he turned to shoot a quail while hunting on a southern Texas ranch. The owner of the ranch stated that, "Mr. Whittington got peppered pretty good."

Whittington suffered a "minor heart attack," and atrial fibrillation due to a pellet that embedded in the outer layers of his heart. The Kenedy County Sheriff's office cleared Cheney of any criminal wrongdoing in the matter, and in an interview with Fox News, Cheney accepted full responsibility for the incident.[42] Whittington was discharged from the hospital on February 17, 2006, and characterized the incident as being quite brutal. Later, Whittington apologized to the vice-president for the trouble the event had caused him and his family. Cheney has stated many times that it was an honest accident.[43]

Future as Vice President

Since 2001, when asked if he is interested in the Republican presidential nomination, Cheney has said he wishes to retire to private life after his term as Vice President expires. In 2004, he reaffirmed this position strongly on Fox News Sunday, saying, "I will say just as hard as I possibly know how to say... 'If nominated, I will not run,' 'If elected, I will not serve,' or not only no, but 'Hell no,' I've got my plans laid out. I'm going to serve this president for the next four years, and then I'm out of here." Such a categorical rejection of a candidacy is often referred to as a "Sherman Statement" for Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman after his dismissal of presidential considerations in 1884.

The conservative Insight magazine reported on February 27, 2006 that "senior GOP sources" had said Cheney was expected to resign after the mid-term Congressional elections in November 2006; however, only Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld left office following the elections.

In November 2006, Vice President Cheney's approval rating was 31 percent according to a poll conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International.[44] Other polls, including the Harris Poll, showed his approval rating within the same range.[44]

Because there is less than two years remaining in Bush's current term, Cheney would not be restricted by the twenty-second amendment if he were to succeed to the Presidency during the current term. He would be eligible to seek two additional full terms as President.

Health problems

Cheney's long histories of cardiovascular disease and periodic need for urgent health care have raised the question of whether he is medically fit to serve as Vice President. Formerly a heavy smoker, Cheney sustained the first of four heart attacks in 1978, at age 37. Subsequent attacks in 1984, 1988, and 2000 have resulted in moderate contractile dysfunction of his left ventricle. He underwent four-vessel coronary artery bypass grafting in 1988, coronary artery stenting in November 2000, and urgent coronary balloon angioplasty in March 2001.

As Vice President, Cheney is cared for by the White House Medical Group. Staff from the WHMG accompany the President and the Vice President while either are traveling, and make advance contact with local emergency medical services to ensure that urgent care is available immediately should it be necessary.[45]

In 2001, a Holter monitor disclosed brief episodes of (asymptomatic) ectopy. An electrophysiologic study was performed, at which Cheney was found to be inducible. An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was therefore implanted in his left upper anterior chest.[46] As of 2004, it has never discharged.

On September 24, 2005, Cheney had an endo-vascular procedure to repair popliteal artery aneurysms bilaterally, a catheter treatment technique used in the artery behind each knee. The condition was discovered at a regular physical in July, and, while not life-threatening itself, is likely an indicator that Cheney's atherosclerotic disease is progressing despite aggressive treatment.[47]

On January 9, 2006, Cheney was taken to the hospital for tests after experiencing shortness of breath. He was given heart tests and tests for retention of water (he had been retaining water due to medication he had been taking for a foot complaint) before being discharged. He was placed on a diuretic to help get rid of the fluids.

Cheney occasionally requires the use of a cane for walking. This, according to Cheney, is due to a foot condition and is unrelated to his cardiovascular disease.

See also

References

- ^ "Bio on Kids' section of [[White House]] site". White House. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "Flyer for [[Calvert Elementary School]]" (PDF). Lincoln Public Schools. 2006-05-15. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ a b "Official US Biography". White House. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- ^ "Cheney describes same-sex marriage as state issue." CNN. August 25, 2004. Retrieved on August 2, 2006.

- ^ Noah, Timothy. "How Dick Cheney Is Like Dan Quayle." Slate. July 27, 2000. Retrieved on August 2, 2006.

- ^ Cheney's Five Draft Deferments During the Vietnam Era Emerge as a Campaign Issue at The New York Times.

- ^ The New York Times, 7/26/00

- ^ Allman, T.D. "The Curse of Dick Cheney." Rolling Stone. August 25, 2004. Retrieved on August 2, 2006.

- ^ http://www.issues2000.org/2004/Dick_Cheney_Education.htm

- ^ http://www.commondreams.org/views/072800-101.htm

- ^ http://www.cato.org/speeches/sp-dc062398.html

- ^ Article Cheney defends voting record, blasts Clinton on talk-show circuit from CNN.

- ^ Bio at the U.S. Department of Defense site

- ^ http://www.commondreams.org/views03/0403-10.htm

- ^ http://www.counterpunch.org/leopold07222004.html

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0155515/

- ^ http://www.whitehouse.gov/energy/

- ^ Template:Pdflink.

- ^ http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2002/06/20020629-1.html

- ^ CNN Transcripts (2002-06-29). "White House Physician Provides Update on Bush's Condition". Retrieved 2006-06-04.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://www.nationalreview.com/york/york200602160841.asp

- ^ Making torture official

- ^ Cheney Plan Exempts CIA From Bill Barring Abuse of Detainees

- ^ http://archives.cnn.com/2001/ALLPOLITICS/stories/01/05/cheney.hill/

- ^ Office of the Vice President on www.americanpresident.org

- ^ "Cheney: The Fatal Touch", The New York Review of Books

- ^ Staff Writer. "Dick Cheney's Youthful Indiscretions." The Smoking Gun. Retrieved on August 2, 2006.

- ^ a b Lemann, Nicholas. "The Quiet Man." The New Yorker. May 7, 2001. Retreived on August 2, 2006.

- ^ Senator Lautenburg Press Release - September 15, 2005

- ^ Bushes Pay $187,768 in Taxes for 2005 - Deb Reichman, AP April 14, 2006

- ^ Are Dick Cheney's Money Managers Betting on Bad News? By Steven Goldberg, Kiplinger's Personal Finance, May 17 2006

- ^ Template:Pdflink General Accounting Office (June 2004). Retrieved on December 20, 2006.

- ^ Helen Dewar and Dana Milbank (2004-06-25). "Cheney Dismisses Critic With Obscenity". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Dana Milbank and Helen Dewar (2004-06-26). "Cheney Defends Use Of Four-Letter Word, Retort to Leahy 'Long Overdue,' He Says". The Washington Post as reported by mindfully.org. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Weekly Review". Harper's Magazine. 2005-09-13. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Text "author - Paul Ford" ignored (help) - ^ Dan Froomkin (2006-10-24). "Spinning the Course". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://nationaljournal.com/about/njweekly/stories/2006/0209nj1.htm

- ^ Bloomberg.com article Cheney, Rove, Libby Sued by Ex-CIA Agent Over Leak (Update1)

- ^ Matt Apuzzo (2006-09-08). "Armitage Says He Was Source on Plame". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ James Vicini (Reuters). "Cheney to Be Called to Testify in CIA Leak Case." Washington Post December 19, 2006. Retrieved on December 20, 2006.

- ^ Matt Apuzzo (AP). "Cheney to Be Defense Witness in CIA Case." San Francisco Chronicle December 19, 2006. Retrieved on December 20, 2006.

- ^ Staff Writer. "Cheney: 'One of the worst days of my life'." CNN. February 16, 2006. Retrieved on August 2, 2006.

- ^ Staff Writer. "Harry Whittington's hospital statement." MSNBC. Retrieved on August 2, 2006.

- ^ a b The Polling Report, Vice President Dick Cheney: Job Ratings. Retrieved Dec. 31, 2006.

- ^ George F. Fuller (2004-04-02). "White House Medical Support" (PDF). The Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Heart Rhythm Society, Why Vice President Richard Cheney Has an ICD. Retrieved Dec. 31, 2006.

- ^ Dr. Zebra (2006-06-06). "Health & Medical History of Richard "Dick" Cheney". Dr Zebra. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Further reading

Works by

- Professional Military Education: An Asset for Peace and Progress : A Report of the Crisis Study Group on Professional Military Education (Csis Report) 1997. ISBN 0-89206-297-5

- Kings of the Hill: How Nine Powerful Men Changed the Course of American History 1996. ISBN 0-8264-0230-5

Works about

- Andrews, Elaine. Dick Cheney: A Life Of Public Service. Millbrook Press, 2001. ISBN 0-7613-2306-6

- Mann, James. Rise of the Vulcans: The History of Bush's War Cabinet. Viking, 2004. ISBN 0-670-03299-9

- Nichols, John. Dick: The Man Who is President. New Press, 2004. ISBN 1-56584-840-3

External links

- Official homepage at whitehouse.gov

- United States Congress. "Dick Cheney (id: C000344)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- US Department of State

- Cheney's DWIs

- Template:SourceWatch

- Dick Cheney at RichardBruceCheney

- Website for PBS Frontline's "The Dark Side" special Focuses on Cheney's involvement in Post-9/11 intelligence gathering, the use and alleged mis-use of intelligence and the effective dismantling of the CIA in favor of the NSA. Includes link to a streaming video version of the program.

- An archive of articles on Cheney at The New York Times.

Critical views

- Joan Didion's review of several books about Cheney in The New York Review of Books

- Allman, T.D. (August 25, 2004). "The Curse of Dick Cheney The veep's career has been marred by one disaster after another". Rolling Stone.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Doubts About Official Shooting Story- MediaChannel

- Borger, Julian (November 30 2005). "Cheney "may be guilty of war crime" Vice-president accused of backing torture - Claims on BBC by former insider add to Bush's woes". The Guardian.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Editorial (December 23, 2005). "Mr. Cheney's Imperial Presidency". New York Times.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Editorial (October 18, 2004). "Dick Cheney: Whip of the Republicans". Voltaire Network.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Editorial (October 26 2005). "Vice President for Torture". Washington Post: A18.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Ireland, Doug (June 18 - June 24 2004). "The Cheney Connection Tracing the Halliburton money trail to Nigeria". LA Weekly.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Manjoo, Farhad (June 24, 2004). "The United States of Texas". Salon.com.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) Two new books document the hold that Bush, Cheney and their corporate allies have on America. - The Unauthorized Biography Of Dick Cheney (TV-Series). Canada. 2004.

{{cite AV media}}: Unknown parameter|crew=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|distributor=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) 42 minute video critical of Cheney - Mike Allen (February 13, 2006). "Slow Leak: How Cheney Stalled News Reports of Hunting Accident". Time.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Howard Kurtz (February 14, 2006). "Monumental Misfire". Washington Post.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Murray Waas (February 9, 2006). "Cheney 'Authorized' Libby to Leak Classified Information". National Journal.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Greg Mitchell (February 9, 2006). "'National Journal': Libby Authorized to Leak by Cheney". Editor & Publisher.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - "Senators: Cheney should be investigated if he OK'd leak". Associated Press (USA Today). February 12, 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Neil A. Lewis (February 10, 2006). ""Libby Testifies Leak Was Ordered, Counsel Says". New York Times.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link)

Speeches and interviews

- Vice President Cheney on September 11, 2001; Norman Mineta, testimony to the 9/11 Commission

- "The Gulf War: A First Assessment" Cheney at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy's Soref Symposium on April 29 1991 outlining his analysis of Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War (archive.org)

- Seattle Post-Intelligencer article containing quotes from a speech on Iraq that Cheney gave at the Discovery Institute in 1992

- Cheney speech given to the Federalist Society in 2001

- Cheney speech given to the Veterans of Foreign Wars 103rd convention in 2003

- Interview of the Vice President by Dave Elswick, KARN, May 3 2004 (audio and text).

- Neil Cavuto interviews Cheney on Fox News, June 25 2004 .

- Vice Presidential Debate, October 5 2004: Transcript text, Audio and Video (RealPlayer or MPG format)

- American conservatives

- American Methodists

- Methodist politicians

- Vice Presidents of the United States

- United States Secretaries of Defense

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Wyoming

- Project for the New American Century

- Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees

- Members of the Trilateral Commission

- Members of the Council on Foreign Relations

- Neoconservatives

- Plame affair

- American chief executives

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Yale University alumni

- Cheney family

- People from Lincoln, Nebraska

- People from Nebraska

- People from Casper, Wyoming

- American hunters

- 1941 births

- Living people