Crusading movement

The crusading movement was a framework of ideologies and institutions that described, regulated, and promoted the Crusades. These were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Christian Latin Church in the Middle Ages. Members of the Church defined the movement in legal and theological terms based on the concepts of holy war and pilgrimage. Theologically, the movement merged ideas of Old Testament wars that were instigated and assisted by God with New Testament ideas of forming personal relationships with Christ. Crusading was a paradigm that grew from the encouragement of the Gregorian Reform of the 11th century and the movement declined after the 16th century Ptotestant Reformation. The ideology continued, but in practical terms dwindled.

The concept of crusading as holy war was based on the Greco-Roman idea of just war, in which an authority initiates the war, there is just cause, and the war is waged with pureness of intention. Adherents saw Crusades as a special form of Christian pilgrimage – a physical and spiritual journey under the authority and protection of the Church. Pilgrimage and crusade were penitent acts and participants were considered part of Christ's army. Crusaders attached crosses of cloth to their outfits, marking them as followers and devotees of Christ, responding to the biblical passage in Luke 9:23 which instructed them "to carry one's cross and follow Christ". Anyone could be involved and the church considered anyone who died campaigning a Christian martyr. The movement became an important part of late-medieval western culture, impacting politics, the economy and society.

Crusading was closely linked with the liberation of Jerusalem and the sacred sites of Palestine from non-Christians. Jerusalem, deemed Christ's legacy, symbolised divine restoration. Its significance as the site of Christ's redemptive acts was pivotal for the inception of the First Crusade and the subsequent establishment of crusading as an institution. Campaigns to reclaim the Holy Land garnered fervent support. Nonetheless, Crusades extended beyond Palestine, encompassing regions like the Iberian Peninsula, northeastern Europe against the Wends, the Baltic region, campaigns against heretics in France, Germany, and Hungary, as well as Italian endeavours targeting the papacy's adversaries. All Crusades bore papal approval and reinforced the Western European concept of a unified Christian Church under papal primacy.

Background

The Crusading movement's beginnings were propelled by a significant shift in the western Church during the mid-eleventh century. Reformers, supported initially by Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor and later opposing his son Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor, assumed power over the papacy around 1040. They astutely perceived the papacy as the optimal vehicle for their mission to eliminate corruption in the Church and strategically took control of it.[3] The phrase Gregorian Reform—the term popularised by Augustin Fliche for all inovation and named after Pope Gregory VII—oversimplifies the complexity of the situation. The reforms emerged from various initiatives across Europe and within different segments of the Church. Not all endeavors were initiated by the papacy; they encompassed opposition to practices like simony and clerical marriage, as well as pushback against papal legates. Eventually, the reformist faction within the Roman Church took the lead, although internal opposition arose due to Gregory VII's policies, resulting in a rift with the emperor and a schism within the papacy.[4] An ideological framework was created by this faction within the clergy who saw themselves as God's agents for the moral and spiritual renewal of Christendom.[5] This is now seen by historians as an important turning point for the movement because these were men who stood for a concept of holy war and would later seek to enact it.[6][7]

Three essential pre-conditions for the enduring crusading movement during the Middle Ages were:[8][9]

- Reform of the Latin Church identity: The Latin Church underwent a significant transformation, becoming an independent force motivated by divine authority for religious revitalisation. This new identity led to conflicts with various entities, including the Holy Roman Empire, Muslim states, other Christian sects, and pagans.

- Emergence of Crusading as a social institution: Crusading evolved into a distinct social institution, with the Church acting as a militarised entity supported by armed nobility referred to as milites Christi or knights of Christ.[10]

- Development of Formal Army Structures: The establishment of formal structures for raising armies was crucial in advancing the Church's interests in crusading endeavors.

These developments led to violent conflicts between the Church and its adversaries, demonstrating the integral role of the crusades in broader social and political transformations. These pre-conditions enabled the crusading movement, and its decline corresponded with the decreasing significance of these factors.[11]

Christianity and war

The Church defined crusading in legal and theological terms based on the theory of holy war and the concept of Christian pilgrimage. Theology merged Old Testament Israelite wars that were instigated and assisted by God with New Testament Christocentric views on forming individual relationships with Christ. Holy war was based on bellum justum, the Greco-Roman idea of just war theory. It was the 4th-century theologian Augustine of Hippo who Christianised this, and canon lawyers developed it from the 11th century into bellum sacrum, the paradigm of Christian holy war.[12][13] He argued that war was sinful, but in certain circumstances, a "just war" could be rationalised. The criteria were:[14][15]

- if an legitimate authority proclaimed the war;

- if it was defensive or for the recovery of rights or property;

- If the intentions were good.

Anselm of Lucca consolidated the just war theories in Collectio Canonum or Collection of Canon Law.[16] In the 11th century, the Church sponsored conflict with Muslims on the southern peripheries of Christendom, including the siege of Barbastro in what is now northern Spain and the Norman conquest of the Emirate of Sicily.[17] In 1074, Gregory VII planned a holy war in support of Byzantium's struggles with Muslims, which produced a template for a crusade, but he was unable to garner the required support, possibly because he stated he intended to lead the campaign himself.[18]

Augustine's principles formed the basis of a doctrine of religious war that was later developed in the 13th century by Thomas Aquinas, canon lawyers, and theologians.[19] Historians, such as Erdmann, thought that from the 10th century the Peace and Truce of God movement restricted conflict between Christians. This movement's influence is apparent in Pope Urban II's speeches, but historians now assert that that influence was limited and had ended by the time of the crusades.[20]

Erdmann documented in The Origin of the Idea of Crusade the three stages of the development of a Christian institution of crusade:

- the Augustinian argument that the preservation of Christian unity was a just cause for warfare;

- the idea developed under Pope Gregory I that the conquest of pagans in an indirect missionary war was also in accordance;

- The paradigm developed under the reformist popes Leo IX, Alexander II, and Gregory VII, in the face of Islamic conflict, that it was right to wage war in defence of Christendom.[21]

The Church viewed Rome as the Patrimony of Saint Peter. This enabled the application of canon law to justify various Italian wars waged by the church as purely defensive crusades to protect theoretical Christian territory.[22][23]

Penance and indulgence

By the 11th century, the Latin Church formulated a system enabling forgiveness and pardon for sins in exchange for genuine remorse, admission of wrongdoing, and acts of penance. Yet, the requirement of refraining from military engagement posed a significant obstacle for warriors. Towards the close of the century, a groundbreaking shift occurred when Gregory VII introduced a novel approach, offering forgiveness for sins accrued through Church-sanctioned violence in backing his endeavours, provided such actions were altruistically motivated.[16][24] This was developed by subsequent Popes into the granting of plenary indulgence that reduced all God-imposed temporal penalties.[12] At the Council of Clermont in November 1095, Urban II effectively founded the crusading movement with two directives: the exemption from atonement for those who journeyed to Jerusalem to free the Church; and that while doing so all goods and property were protected.[25]

The weakness of conventional theologies in the face of crusading euphoria is shown in a letter critical of Pope Paschal II from the writer Sigebert of Gembloux to the crusader Robert II, Count of Flanders. Sigebert referred to Robert's safe return from Jerusalem but completely avoided mentioning the crusade.[26] It was Calixtus II who first promised the same privileges and protections of property to the families of crusaders.[27][28] Under the influence of Bernard of Clairvaux, Eugenius III revised Urban's ambiguous position with the view that the crusading indulgence was remission from God's punishment for sin, as opposed to only remitting ecclesiastical confessional discipline.[29] Innocent III emphasised crusader oaths and clarified that the absolution of sins was a gift from God, rather than a reward for the crusaders' suffering.[30][31] With his 1213 bull Quia maior, he appealed to all Christians, not just the nobility, offering the possibility of vow redemption without crusading. This set a precedent for trading in spiritual rewards, a practice that scandalised devout Christians and became a contributing cause of the 16th century Protestant Reformation.[32][33]

As late as the 16th century, writers sought redemptive solutions in the traditionalist wars of the cross, while others – such as English martyrologist John Foxe – saw these as examples of papist superstition, corruption of religion, idolatry, and profanation.[34][35] Critics blamed the Roman Church for the failure of the crusades. War against the infidel was laudable, but not crusading based on doctrines of papal power, indulgences, and against Christian religious dissidents such as the Albigensian and Waldensians. Justifying war on juristic ideas of just war to which Lutherans, Calvinists, and Roman Catholics could all subscribe, and the role of indulgences, diminished in Roman Catholics tracts on the Turkish wars. Alberico Gentili and Hugo Grotius developed international laws of war that discounted religion as a cause, in contrast to popes, who persisted in issuing crusade bulls for generations.[34]

Knights and chivalry

In the early stages of the crusading movement, chivalry was nascent, yet it eventually came to shape the ideals and principles of knights, playing a central role in the crusading ethos. Literature depicted the esteemed status of knighthood, which, however, remained separate from the aristocracy. Texts from the 11th and 12th{{nbsp}centuries portray a class of knights who were comparatively closer in status to peasants within the preceding generations.[36][37] In the 13th century knighthood became equated with nobility, as a social class with legal status, closed to non-nobles.[37] Chivalric development grew from a society dominated by the possession of castles. Those who defended these became knights. At the same time, a novel form of combat evolved, based on the use of heavy cavalry, coupled with the growing naval capability of Italy's maritime republics, that strengthened the feasibility of the First Crusade.[38][39] These new methods of warfare led to the development of codes, ethics, and ideologies. Contrary to the representation in the romances, battles were rare. Instead, raids and sieges predominated, for which there was only a minimal role for knights. During the 11th and 12th centuries, the armies had a ratio of one knight to between seven and twelve infantry, mounted sergeants, and squires.[38]

Knighthood required combat training, which created solidarity and gave rise to combat as a sport.[40] Crusade preachers used tournaments and other gatherings to obtain vows of support from attending dignitaries, begin persuasive campaigns, and announce a leader's taking of the cross.[41] Military strategy and medieval institutions were immature in feudal Europe, with power too fragmented for the formation of disciplined units. Despite the courage of knights and some notable generalship, the crusades in the Levant were typically unimpressive.[42]

Developing vernacular literature glorified the idea of adventure and the virtues of valour, largesse, and courtesy. This created an ideal of the perfect knight. Chivalry was a way of life, a social and moral model that evolved into a myth. The chivalric romantic ideals of excellence, martial glory, and carnal—even adulterous—love conflicted with the spiritual views of the Church. Whilst fearing this knightly caste, the Church co-opted it in conflicts with feudal lords. Writers lauded those who fought for the Church; others were excommunicated. By the 11th century, the Church developed liturgical blessings sanctifying new knights; and existing literary themes, such as the legend of the Grail, were Christianized and treatises on chivalry written.[43] In 1100, kings depicted themselves as knights to indicate their power.[44] Participation in crusades was considered integral to idealized knightly behaviour.[45] Crusading became part of the knightly class's self-identification, creating a cultural gap with other social classes.[46] From the Fourth Crusade, it became an adventure normalised in Europe, which altered the relationship between knightly enterprise, religious, and worldly motivation.[47]

Military orders

The crusaders' propensity to follow the customs of their western European homelands meant that there were very few innovations adopted from the culture of the Crusader states. Three notable exceptions to this were the military orders, warfare, and fortifications.[48] The Knights Hospitaller were founded in Jerusalem before the First Crusade but added a martial element to their ongoing medical functions to become a much larger military order.[49] In this way, knighthood entered the previously monastic and ecclesiastical sphere.[50]

Military orders – like the Knights Hospitaller and Knights Templar – provided Latin Christendom's first professional armies, to support the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the other crusader states. The Templars were founded around 1119 by a small band of knights who dedicated themselves to protecting pilgrims en route to Jerusalem.[51] These orders became supranational organizations with papal support, leading to rich donations of land and revenue across Europe. This led to a steady flow of recruits and the wealth to maintain multiple fortifications in the crusader states. In time, the orders developed into autonomous powers.[52]

After the fall of Acre, the Hospitallers relocated to Cyprus, then conquered and ruled Rhodes (1309–1522) and Malta (1530–1798), and continue to exist to the present-day. King Philip IV of France had financial and political reasons to oppose the Knights Templar, which led him to exert pressure on Pope Clement V. The pope responded in 1312, with a series of papal bulls including Vox in excelso and Ad providam, which dissolved the order on alleged and false grounds of sodomy, magic, and heresy.[53]

Common people

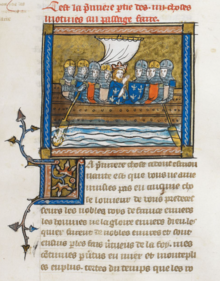

There were contributions to the crusading movement from classes other than the nobility and knights. Grooms, servants, smiths, armourers, and cooks provided services and could fight if required. Women also formed part of the armies. Despite papal recruitment concentrating on warriors in the movement's early years, it proved impossible to exclude non-knightly participants.[54] Historians have increasingly researched the motivations of the poor who joined the early crusades in large numbers and engaged in popular unsanctioned events during the 13th and 14th centuries. Participation was voluntary, so preaching needed to propagandise theology in popular forms, which often led to misunderstanding. For example, crusading was technically defensive, but amongst the poor, Christianity and crusading were aggressive.[55] An emphasis on popular preaching, developed in the 12th century, generated a wealth of useful resources. The most popular example began in 1268, Humbert of Romans collected, what he considered, the best arguments into a single guide.[56] The popular but short-lived outbreaks of crusading enthusiasm after Acre fell to Egypt were largely driven by eschatological perceptions of crusading amongst the poor rather than the advanced, professionalized plans advocated by theorists.[57]

Pilgrimage was not a mass activity. To develop an association with the Holy Sepulchre, western Christians built models of the site across Europe and dedicated chapels. Although these acts predated crusading, they became increasingly popular and may have provided a backdrop to Easter Drama or sacramental liturgy. In this way, what was known as the remotest place in 1099 became embedded in daily devotion, providing a visible sign of what crusading was about.[58]

Ungoverned, uncontrolled peasant crusading erupted in 1096, 1212, 1251, 1309, and 1320. Apart from the Children's Crusade of 1212, these were accompanied by violent antisemitism; it is unexplained why this was the exception. The literate classes were hostile to this particular unauthorized crusade but mytho-historicized it so effectively that it is one of the most evocative verbal artefacts from the Middle Ages that remained in European and American imagination. The term "Children's Crusade" requires clarification in that neither "children" – in Latin pueri – nor "crusade" – described in Latin as peregrinatio, iter, expeditio, or crucesignatio – are completely wrong or correct.[59] Although there are a number of written sources, they are of doubtful veracity, differing about dates and details while exhibiting mytho-historical motifs and plotlines.[60] Clerics used the sexual purity and "innocence" of the pueri as a critique of the sexual misbehaviour in the formal crusades, which was seen to be the source of God's anger and the failure of campaigns.[61]

Perception of Muslims

In medieval times, ethnic identity was a social construct, defined in terms of culture rather than race; and Christians considered all of humanity common descendants of Adam and Eve. Chroniclers used the ethno-cultural terms "barbarians" or barbarae nationes, which were inherited from the Greeks of antiquity, for "others" or "aliens", which were thus differentiated from the self-descriptive term "Latins" that the crusaders used for themselves.[62]

Although there are no specific references to crusading in the 11th century chanson de geste Chanson de Roland, the author, for propaganda purposes, represented Muslims as monsters and idolators. Christian writers repeated this image elsewhere.[63] Visual cues were used to represent Muslims as evil, dehumanized, and monstrous aliens with black complexions and diabolical physiognomies. This portrayal remained in western literature long after the territorial conflict of the crusades had faded into history. The term "Saracen" designated a religious community rather than a racial group, while the word "Muslim" is absent from the chronicles. Instead, various terms are used – such as "infidels", "gentiles", "enemies of God", and "pagans". The conflict was seen as a Manichean contest between good and evil.[64] Historians have been shocked by the inaccuracy and hostility involved in such representations, which included crude insults to Mohammad, caricatures of Islamic rituals, and the representation of Muslims as libidinous gluttons, blood-thirsty savages, and semi-human.[65] Historian Jean Flori argues that to self-justify Christianity's move from pacifism to warfare, their enemies needed to be ideologically destroyed.[66]

Despite the negative representations, the Turks were respected as opponents in the Gesta Francorum, which considered only the Turks and the Franks as having a knightly lineage. Some, such as the character Aumont in the Chanson d'Aspremont, were represented as equals, even as far as being seen as following the chivalric code. By the Third Crusade, there is evidence of a class division within the nobility in both camps who shared a chivalric identity that overcame religious and political differences. This differentiated the two elites from their common co-religionists who had other loyalties. Increasingly, epics involved instances of conversion to Christianity, which promised a solution to the conflict in favour of the Franks at a time they were being defeated militarily.[67] Poets often relied on the patronage of leading crusaders, so they extolled the values of the nobility, the feudal status quo, chivalry, martial prowess, and the idea of the Holy Land being God's territory usurped and despoiled. Writers designed works encouraging revenge on Muslims, who deserved punishment and were God's enemies. The artists addressed their works to the patrons, often beginning with Chevalier or Seigneur, based on dialectical understanding of rhetoric in terms of praise or blame. Works praised those who answered the call to crusade, writers vilified those who did not.[68] The reformist Church's identity-interest complex framed Islam as a particular form of heresy. Muslim rule in formerly Christian territory was an "unjust" confiscation of Christian property, and this persecution of Christians required repayment. The view was that these injustices demanded Christian action. Islamic polities' own identity-interest complexes led them to be equally violently opposed to the restoration of Christian rule.[69]

Evolution

The papacy developed "political Augustinianism" into attempts to remove the Church from secular control by asserting ecclesiastical supremacy over temporal polities and the Eastern Orthodox Church. This was associated with the idea that the Church should actively intervene in the world to impose "justice".[70] In the 12th century, Gratian and the Decretists elaborated on this, and Aquinas refined it in the 13th century.[12] In the late 11th and early 12th century the papacy became a unit for organized violence in the Latin world order, equivalent to other kingdoms and principalities. This required what were partly inefficient mechanisms of control that mobilised secular military forces under direct control of the papacy.[71]

The sanctification of war developed during the 11th century through campaigns fought for, instigated, or blessed by the pope, including the Norman conquest of Sicily, the recovery of Iberia from the Muslims, and the Pisan and Genoese Mahdia campaign of 1087 to North Africa. Crusading followed this tradition, assimilating chivalry within the locus of the Church through:

- The concept of pilgrimage, the primary focus in Pope Urban II's call to crusade.

- The view on penance, that it could apply to killing adversaries.

- The identification of Muslims as pagans. This made those killed by them martyrs, equivalent to early Christian victims of pagan persecution.

- The identification of the recovery of the Holy Land, the land of Christ that was seen to have been despoiled bu Muslims. Urban assembled his own army to re-establish the patrimony of Christ over the heads of kings and princes.

- The principle that crusade knights were Christ's vassals. This refined the term used originally for Christians, then only for clergy and monks fighting evil through prayer, and from 1075 warriors fighting for St. Peter before the term became synonymous with crusaders. Knights no longer needed to abandon their way of life or become monks to achieve salvation. Crusading was a break with chivalry; Urban II denounced war among Christians as sinful, but fighting for Jerusalem led by a new class of knights was meritorious and holy. This ideology did not support chivalry – only crusading.[72]

Urban II made decisions that were fundamental for the nascent religious movements, rebuilding papal authority and restoring its financial position. It was at the Council of Clermont that he arranged the juristic foundation of the crusading movement.[25] The catalyst was an embassy from the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos to the earlier Council of Piacenza, requesting military support in his conflict with the Seljuk Empire. These Turks were expanding into Anatolia and threatening Constantinople.[73] He subsequently expressed the dual objectives for the campaign: firstly, freeing Christians from Islamic rule; secondly, freeing the Holy Sepulchre – the tomb of Christ in Jerusalem – from Muslim control.[2] This led to what is recognised as the first crusading expedition.[25]

The First Crusade was a military success, but a papal failure. Urban initiated a Christian movement seen as pious and deserving but not fundamental to the concept of knighthood. Crusading did not become a duty or a moral obligation – like a pilgrimage to Mecca or jihad were to Islam – and the creation of military religious orders is indicative of this failure.[74] Canon law forbade priests from warfare, so the orders consisted of a class of lay brothers, but the orders were otherwise remarkably like other monastic orders.[75] The difference was that these became orders of monks called to the sword and to blood-shedding. This was a doctrinal revolution within the Church regarding warfare. Its acknowledgement in 1129 at the Council of Troyes integrated the concept of holy war into the doctrines of the Latin Church. This illustrated the failure of the Church to assemble a force of knights from the laity and the ideological split between crusades and chivalry.[74] The military vulnerability of the settlers in the East required further supportive expeditions through the 12th and 13th centuries. In each generation, these followed the pattern of a military setback in the East, a request for aid, and crusade declarations from the papacy.[76]

12th century

The first century of crusading coincided with the Renaissance of the 12th century, and crusading was represented through the rich vernacular literature that evolved in France and Germany during the period. There are French language versions, and in the literary language of southern France – Occitan, of epic poems such as the Chanson d'Antioche about the Siege of Antioch (1268) and the Canso de la Crozada about the Albigensian Crusade. In French, these were known as Chansons de geste, taken literally from the Latin for "deeds done".[77] Songs dedicated to the subject of crusading – known as crusade songs – are rare. Still, from the time of the Second Crusade onwards, many works survive in Occitan, French, German, Spanish, and Italian that include crusading as a topic or use it as an allegory. Poet-composers such as the Occitan troubadours Marcabru and Cercamon wrote songs with themes called sirventes and about absent loves called pastorela. Crusading became the subject of songs and poems rather than creating new genres. Troubadours, and their northern French Trouvère and German Minnesänger equivalents, grew in popularity from 1160, leaving many songs about the third and fourth crusades.[78] Crusade songs served multiple purposes:

- They provided material for the poet/performer, variations on courtly love, allegories, and paradigms.

- Audiences learnt doctrine, information, and propaganda unmediated by the Church.

- They reinforced the nobility's self-image, confirmed its position in society, and inspired esprit de corps.

- They provided for the expression of injustice and criticism of mismanagement when events did not go well.[79]

There is little evidence of protest by senior churchmen. The crusade's success was astonishing and seen as only possible via a manifestation of God's will.[80] When Paschal succeeded Urban he defeated the three anti-popes that followed Clement III. He also quarreled with Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor, his eventual successor Guy, archbishop of Vienne (later Calixtus II), and Church reformists over the right to invest bishops. His legislation developed that of his predecessors in connection with crusading. After the failed 1101 crusade, he supported Bohemond I of Antioch's gathering of another army with the provision of the flag of St. Peter and a cardinal legate, Bruno of Segni.[81] Calixtus II extended the definition of crusading during his five years as Pope. He was one of the six sons of Count William I of Burgundy, and a distant relation to Baldwin II of Jerusalem. Three of his brothers died taking part in the 1101 Crusade which exemplifies the fact that early crusade recruitment concentrated in certain families and networks of vassals. These groups demonstrated their commitment through funding, although the sale of churches and tithes may have been a pragmatic acceptance that retaining these properties was unsustainable in the face of the reform movement in the Church. These kinship groups often exhibited traditions of pilgrimage to Jerusalem, association with Cluniac monasticism, the reformed papacy, and the veneration of certain saints. Female relatives spread these values through marriage.[82] He also equated the reconquest of Iberia from the Muslims with crusading in the Holy Land, proposing a war on two fronts and posthumously leading to the campaign by Alfonso the Battler against Granada in 1125.[27][28]

Strategically, the crusaders could not hold Jerusalem in isolation, which led to the establishment of other western polities known as the Latin East. Even then, these required regular missions for their defence, supported by the developing military orders. The movement expanded into Spain with campaigns in 1114, 1118, and 1122.[27] Eugenius III was influenced by Bernard of Clairvaux to join the Cistercians. Exiled by an antipapal commune, Eugenius III encouraged King Louis VII of France and the French to defend Edessa from the Muslims with the bull Quantum predecessores in 1145, and again, slightly amended, in 1146. Eugenius III commissioned Bernard of Clairvaux to the crusade and travelled to France where he issued Divini dispensatione (II) under the influence of Bernard, associating attacks on the Wends and the reconquest of Spain with crusading. The crusade in the East was not a success, and he subsequently resisted further crusading.[29] Although there were three campaigns in Spain, and in 1177 one in the East, the next three decades saw the lowest ebb of the movement until the 15th century. This lull ended when news of the defeat at the hands of the Muslims at the Battle of Hattin created consternation throughout Europe and reignited enthusiasm.[27] Early crusades – such as the First, Second and Albigensian – included peasants and non-combatants until the high costs of journeying by sea made participation in the Third and Fourth Crusade impossible for the general populace. Afterward, the professional and popular crusades diverged, such as in 1309 when the Crusade of the Poor and one by the Hospitallers occurred simultaneously, both responding to Pope Clement V's crusading summons of the previous year. [83]

From the latter part of the century, Europeans adopted the terms crucesignatus or crucesignata, meaning "one signed by the cross", with crusaders marking themselves as a follower of Christ by attaching cloth crosses to their clothing. The fashion derived from the biblical passages in Luke 9:23, Mark 8:34 and Matthew 16:24 "to carry one's cross and follow Christ".[84][85] Through this action, a personal relationship between Crusaders and God was formed that marked the crusader's spirituality. Anyone could become a crusader, irrespective of gender, wealth, or social standing. This was an imitatio Christi, an "imitation of Christ", a sacrifice motivated by charity for fellow Christians; and those who died campaigning were martyrs.[86] The Holy Land was the patrimony of Christ; its recovery was on behalf of God. The Albigensian Crusade was a defence of the French Church, the Baltic Crusades were campaigns conquering lands beloved of Christ's mother Mary for Christianity.[87]

13th century

Crusade providentialism was intricately linked with a prophetic sensibility at the end of the 12th century. Joachim of Fiore included the war against the infidels in his cryptic conflations of history combining past, present, and future.[88] Foreshadowing the Children's Crusade, the representatives of the third age were children, or pueri. Franciscans such as Salimbene saw themselves as ordo parvulorum – an "order of little ones" amongst a revivalist enthusiasm and a spirit of prophetic elation. The Austrian Rhymed Chronicle added prophetic elements of mytho-history to the Children's Crusade. In 1213, Innocent III called for the Fifth Crusade by announcing that the days of Islam were over.[89]

Propaganda

Advocates within papal circles, specific monastic orders, mendicant friars, and the burgeoning universities portrayed the crusading movement as a unified Christian endeavor. Nevertheless, achieving uniformity in medieval Christendom proved unattainable in practice. The central authorities of the church lacked the bureaucratic infrastructure and authoritative control necessary to enforce such uniformity.[90] The Cistercian Order, the Dominicans and Franciscans provided propaganda for campaigns. The message varied, but the aim of papal control remained. Aristocratic family networks and feudal hierarchies played key roles in disseminating informal propaganda about crusades during the medieval era. Courts and tournaments served as platforms where people exchanged stories, songs, poems, and news. Despite troubadours' hostility following the Albigensian Crusade, songs about the crusades gained popularity. Visual representations in various mediums such as books, churches, and palaces also contributed to this dissemination of information. Church art and architecture, including murals, stained glass windows, and sculptures, often depicted themes related to the movement.[91][92][93]

There are numerous texts written between approximately 1225 and 1500 featuring crusading themes. These works were performed to audiences for entertainment and as propaganda, emphasising political and religious identity by distinguishing between Christian and non-Christian realms.[94] Examples include romances, travelogues like Mandeville's Travels, poems such as Piers Plowman and John Gower's Confessio Amantis, and works by Geoffrey Chaucer.[95][96][97][98] Despite being written after the decline of crusading fervour, they indicate a sustained interest in the topic. Authors depicted a triumphant and morally superior chivalric Christendom. Some likened Muslim leaders to contemporary politicians. Common motifs included Christian knights engaging in chivalrous adventures against Muslim adversaries. Legendary figures like Charlemagne were depicted with both military prowess and moral authority, lauded for victories over pagans and fervent religious zeal, even through forced conversions. The entertainment value of these narratives played a crucial role in fostering anti-Muslim sentiment, demonstrating populist religious animosity and curiosity toward "Saracens," who were viewed as rivals in economic, political, military, and religious spheres.[94]

Institutional reform

In 1198, Innocent III was elected pope, and he reshaped the ideology and practice of crusading. This was done by creating a new executive office to organize the Fourth Crusade, appointing executors in each province of the Church, as well as having freelancers, such as Fulk of Neuilly, preaching. This system developed further in time for the Fifth Crusade, with executive boards, that held legatine power, established in each province. Delegates in dioceses and archdioceses reported to these bodies on promotional policy while the papacy codified preaching. Political circumstances meant that more pragmatic and ad-hoc approaches followed, but the coherence of local promotion remained greater than before.[99] Under Innocent III the papacy introduced taxation to fund the campaigns and encouraged donations.[30][31] In 1199, he was the first pope to deploy the conceptual and legal apparatus developed for crusading to enforce papal rights.[32][33] From the 1220s, crusader privileges were regularly granted to those who fought against heretics, schismatics, or those Christians the papacy considered non-conformist.[100]

Popular crusading

Crusade scholars like Gary Dickson have delved into popular crusades, which others like Riley-Smith exclude by definition, showcasing the varied nature of the crusading movement.[101] Part of the tradition of outbreaks of popular crusading spanning from 1096 until the 1514 Hungarian Peasants' Crusade, the 1212 Children's Crusade marked the inaugural independent popular crusade. It emerged from preaching associated with the Albigensian Crusade and processions seeking divine intervention for the Iberian crusades. Unauthorised by the Church and lacking papal endorsement, such crusades were considered illegitimate, with participants being unconventional crusaders.[102] Despite this, they perceived themselves as genuine crusaders, utilizing pilgrimage and crusade symbols like the cross. Historians refer to these events by various names, such as people's crusades, peasants' crusades, shepherds' crusades, and crusades of the poor. Despite a wide array of research, common features remain difficult for historians to pinpoint. Charismatic leadership was evident until the 14th century, while eschatological beliefs led to anti-Semitic violence and movements of self-determination among the impoverished. Although diverse, popular crusades shared historical contexts with official crusades, illustrating the enduring influence of crusading concepts and the involvement of non-noble believers in significant events within Latin Christendom. Emphasising the role of clerics and warrior knights overlooks the significance of the movement.[83]

Early century

Between 1217 and 1221, Cardinal Hugo Ugolino of Segni led a preaching team in Tuscany and northern Italy as papal legate. At this time:

- he negotiated the end of various conflicts in Lucca, Pisa, Pistola, the Republic of Genoa, Bologna and the Republic of Venice;

- used the five percent income tax on the Church, a tax known as the "clerical twentieth";

- paid mercenaries to join the Fifth Crusade, which was delayed by Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor's repeatedly postponed embarkation;

- provided grants to crucesignati.

In this way, the development of more lax rules regarding Church funding and crusade recruitment is evidenced.[103]

Ugolino became pope in 1227, taking the name Pope Gregory IX, and excommunicated Frederick for his prevarication.[104] Frederick finally arrived in the Holy Land where he negotiated Christian access to Jerusalem, but his claim to the crown through marriage and his excommunicate status created political conflict in the kingdom. The settlement was decried by Gregory, but he used the resulting peace to further develop the wider movement:

- The poor orders organized inquisitions into heretics.

- The Church expanded crusade recruitment.

- Missionaries evangelized.

- Negotiations opened with the Greek Church.

- The Dominican Order channelled support to the Teutonic Order.[22]

Gregory was the first pope to deploy the full range of crusading mechanisms – such as indulgences, privileges, and taxes – against the emperor, and extended commutation of crusader vows to other theatres. These measures and the use of clerical income tax in the conflict with the emperor formed the foundations for political crusades by Gregory's successor, Innocent IV.[22] Frederick II attempted to increase his influence in areas under papal control, such as Lombardy and Sardinia. In 1239, Gregory IX responded by excommunicating him. Two years later Frederick II's army threatened Rome after Gregory IX gathered a general council to depose him. Gregory IX responded to this with crusading terminology but died during the conflict.[22][23] Innocent IV based crusading ideology on the Christians' right to ownership. He acknowledged Muslims' land ownership but emphasised that this was subject to Christ's authority.[105] Rainald of Segni, who became pope in December 1254, taking the name Alexander IV, continued the policies of Gregory IX and Innocent IV. This meant supporting crusades against the Hohenstaufen dynasty, the North African Moors, and pagans in Finland and the Baltic region. He attempted to give Sicily to Edmund Crouchback, the son of King Henry III, in return for a campaign to win it from Manfred, King of Sicily, the son of Frederick II. But this was logistically impossible, and the campaigns were unsuccessful. Alexander failed to form a league to confront the Mongols in the East or the invasion of Poland and Lithuania. Frequent calls to fight in eastern Europe (1253–1254, 1259) and for the Outremer (1260–1261) raised small forces, but Alexander's death prevented a crusade.[106] At the Second Council of Lyons in 1274, Bruno von Schauenburg, Humbert, Guibert of Tournai, and William of Tripoli produced treatises articulating the requirements for success. Crusading appears to have maintained popular appeal, with recruits from a wide geographical area continuing to take the cross.[107]

Criticism

Early criticism of crusading and the conduct of crusaders is evident. While the concept itself was seldom questioned in the 12th and 13th centuries, there were vigorous objections to crusades targeting heretics and Christian secular powers. The assault on Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade and the diversion of resources against Church enemies in Europe, such as the Albigensian heretics and the Hohenstaufen, drew condemnation. Troubadours in southern France expressed discontent with expeditions, lamenting the neglect of the Holy Land. The behavior of participants was seen as falling short of the expectations of a holy war, with chroniclers and preachers decrying instances of sexual immorality, greed, and arrogance. Western Europeans attributed failures and setbacks, such as those during the First Crusade and the defeat of the kingdom of Jerusalem at Hattin by Saladin, to human frailty. Gerhoh of Reichersberg linked the shortcomings of the Second Crusade to the arrival of the Antichrist and accused the movement of fostering increased puritanism.[107][108][109]

In response to criticism, the movement implemented ceremonial processions, calls for reform, bans on gambling and extravagance, and restrictions on the participation of women. The Würzburg Annals condemned the conduct of the crusaders, attributing it to diabolical influence. The defeat of Louis IX of France at the Battle of Mansurah in 1250 triggered debates on crusading in sermons and writings, including Humbert of Romans's work De praedicatione crucis—concerning the preaching of the cross. Humbert raised doubts about the method of forcible conversion.[110]

The expense of maintaining armies resulted in taxation, a notion vehemently opposed by Roger Wendover, Matthew Paris, and Walther von der Vogelweide. Critics expressed apprehensions regarding Franciscan and Dominican friars exploiting the vow redemption system for monetary benefits. While the peaceful conversion of Muslims was considered a possibility, there is no indication that it reflected the prevailing public sentiment, as the ongoing crusades suggest otherwise.[111]

Later century

The triumph of the Egyptian Mamluk in the Holy Land plunged the crusading movement into turmoil. Despite successes in Spain, Prussia, and Italy, the loss of the Holy Land remained irreparable. This crisis encompassed both a crisis of faith and military strategy, deemed religiously disgraceful by the Second Council of Lyon.[112]

Prominent critics such as Matthew Paris in Chronica Majora and Richard of Mapham, the dean of Lincoln, voiced notable concerns at the council. The military orders, especially the Teutonic Order, faced censure for their arrogance, greed, luxurious lifestyles funded by their wealth, and inadequate deployment of forces in the Holy Land. Internal conflicts between the Templars and Hospitallers, as well as among Christians in the Baltic, hindered collaborative efforts. The Church perceived military actions in the East as less effective due to the independence of these orders and their perceived reluctance to engage in combat with Muslims, with whom critics believed they maintained overly cordial relations. A minority perspective, advocated by Roger Bacon and others, argued that aggressive actions, particularly in the Baltic, impeded the conversion efforts.[113]

The movement continued to exhibit traits of innovation, commitment, resilience, and flexibility by consolidating methods of organisation and finance, which facilitated its survival.[114] General opinion did not consider the loss of the Holy Land as final, only later when the Hundred Years' War began in 1337 did hopes for recovery fade.[112] One of Pope Gregory X's objectives was the reunification of the Latin and Greek churches, which he viewed as essential for a new crusade. At the Second Council of Lyon, he demanded the Eastern Orthodox delegation accept all Latin teaching. In return, Gregory offered a reversal of papal support for Charles I of Anjou, the king of Sicily, to meet the Byzantines' primary motivation of the cessation of Western attacks. However, there was little interest from European monarchs, who were focussed on their own conflicts.[112] Gregory created a complex tax gathering system for the funding of crusading, dividing Western Christendom in 1274 into twenty-six collectorates. Each of these was under the direction of a general collector who further delegated the assessment of tax liability to reduce fraud. The vast amounts raised by this system led to clerical criticism of obligatory taxation.[115]

14th century

Between the councils of Lyon in 1274 and Vienna in 1314, there existed over twenty treatises concerning the recovery of the Holy Land. These were instigated by Popes who, following the lead of Innocent III, sought counsel on the matter. This led to unfulfilled strategies for the blockading Egypt and possible expeditions to establish a foothold that would pave the way for full-scale crusades with professional armies. Discussions among writers often revolved around the intricacies of Capetian and Aragonese dynastic politics. Periodic bursts of popular crusading occurred throughout the decades, spurred by events like the Mongol victory at Homs and grassroots movements in France and Germany. Despite numerous obstacles, the papacy's establishment of taxation, including a six-year tithe on clerical incomes, to fund contracted professional crusading armies, represented a remarkable feat of institutionalisation.[116] The 1320 pastores of the Second Shepherds' Crusade was the first time that the papacy decried a popular crusade.[83]

Beginning in 1304 and lasting the entire 14th century, the Teutonic Order used the privileges Innocent IV had granted in 1245 to recruit crusaders in Prussia and Livonia, in the absence of any formal crusade authority. Knightly volunteers from every Catholic state in western Europe flocked to take part in campaigns known as Reisen, or journeys, as part of a chivalric cult.[117] Commencing in 1332, the numerous Holy Leagues in the form of temporary alliances between interested Christian powers, were a new manifestation of the movement. Successful campaigns included the capture of Smyrna in 1344, the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, and the recovery of territory in the Balkans between 1684 and 1697.[118]

After the Treaty of Brétigny between England and France, the anarchic political situation in Italy prompted the curia to begin issuing indulgences for those who would fight the merceneries threatening the pope and his court at Avignon. In 1378, the Western Schism split the papacy into two and then three, with rival Popes declaring crusades against each other. The growing threat from the Ottoman Turks provided a welcome distraction that would unite the papacy and divert the violence to another front.[119] By the end of the century, the Teutonic Order's Reisen had become obsolescent. Commoners had limited interaction with crusading beyond the preaching of indulgences, the success of which depended on the preacher's ability, local powers' attitudes, and the extent of promotion. However, there is no evidence that the failure to organize anti-Turkish crusading was due to popular apathy or hostility rather than to finance and politics.[120]

15th century

Gabriel Condulmaro, hailing from Venice, ascended to the papal throne as Eugenius IV in 1431 and pursued a policy of ecumenical negotiation with the Byzantine Empire. John V Palaiologos, accompanied by a sizable delegation, engaged in discussions with Eugenius that ultimately led to the proclamation of union among the Latin, Greek Orthodox, Armenian, Nestorian, and Cypriot Maronite churches. As a gesture of gratitude, the Byzantines received military assistance. Between 1440 and 1444, Eugenius coordinated efforts to defend Constantinople from the Turks through various crusading movements involving Balkan Christians, particularly under the leadership of Hungarian commander John Hunyadi, as well as the Venetian navy, the papacy, and other Western rulers. However, this strategy faltered following the disastrous defeat of the Balkan powers at the Battle of Varna in November 1444. Despite facing opposition at the Council of Basel in 1439, where opponents favoured the election of Felix V as pope, Eugenius retained support and continued his policies until his death in 1447. The fall of Constantinople to Mehmed II in 1453 marked the beginning of a twenty-eight-year expansion of the sultanate.[121][122]

Enea Silvio Piccolomini, known as a prominent Renaissance humanist, ascended to the papacy as Pope Pius II in 1458, with his primary objective being the recovery of Constantinople. Utilising humanist principles along with inspiration from Pope Urban II's sermon at Clermont, the First Crusade, Robert of Rheims's chronicle, and Bernard of Clairvaux's exhortation, Pius II advocated for this cause through letters and speeches delivered at events such as the Congress of Mantua, the Diets of Regensburg, and Frankfurt. Despite Pius's efforts to blend crusading with humanist ideology to form a European alliance, as seen in the unsuccessful Mantua congress where he pledged personal involvement in the expedition, his endeavours were unfruitful.[123]

Moreover, Pius II suggested to Mehmed II the possibility of converting to Christianity and emulating the legacy of Constantine. Despite coming close to organizing an anti-Turkish crusade in 1464, his plans ultimately failed. Throughout his papacy and those of his immediate successors, the raised funds and military resources were insufficient, poorly timed, or misallocated for effective action against the Turks. This was despite:

- the commissioning of advisory tracts reconsidering the political, financial, and military issues;

- Frankish rulers exiled from the Holy Land who toured Christendom's courts seeking assistance;

- individuals, such as Cardinal Bessarion, dedicating themselves to the crusading movement; and

- the continued levying of church taxes and preaching of indulgences.[124]

Warfare was now more professional and costly.[120] This was driven by factors including contractual recruitment, increased intelligence and espionage, a greater emphasis on naval warfare, the grooming of alliances, new and varied tactics to deal with different circumstances and opposition, and the hiring of experts in siege warfare.[125] There was disillusionment and suspicion of how practical the objectives of the movements were. Lay sovereigns were more independent and prioritized their own objectives. The political authority of the papacy was reduced by the Western Schism, so popes such as Pius II and Innocent VIII found their congresses ignored. Politics and self-interest wrecked any plans. All of Europe acknowledged the need for a crusade to combat the Ottoman Empire, but effectively all blocked its formation. Popular feeling is difficult to judge: actual crusading had long since become distant from most commoners' lives. One example from 1488 saw Wageningen parishioners influenced by their priest's criticism of crusading to such a degree they refused to allow the collectors to take away donations. This contrasts with chronicle accounts of successful preaching in Erfurt at the same time and the extraordinary response for a crusade to relieve Belgrade in 1456.[120]

Rodrigo Borja, who ascended to the papacy as Pope Alexander VI in 1492, endeavored to revive crusading efforts as a response to the growing threat posed by the Ottoman Empire. However, his primary focus remained on advancing the secular ambitions of his son, Cesare, and preventing Charles VIII of France of France from conquering Naples. While the sale of indulgences garnered significant funds, there was resistance to the imposition of clerical tithes and other fundraising endeavors aimed at supporting mercenary crusade armies. Critics argued that the papacy diverted funds to Italian interests, while secular rulers were accused of misusing allocated resources. Plans for a crusade by Hungary, Bohemia, and Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor in 1493 were thwarted by Charles VIII's invasion schemes, leading to alliances between Italy and Turkey instead. Despite these challenges, figures like Marino Sanuto the Younger, Stephen Teglatius, and Alexander himself, in works like Inter caetera, emphasized the ongoing commitment to crusading. They discussed organizational hurdles, theoretical frameworks, the significance of the Spanish Reconquista culminating in the capture of Granada in 1492, efforts to defend and expand the faith, and the division of territories in northern Africa and the Americas between Portugal and Spain. Pope Alexander VI even granted crusading privileges and financial support to facilitate these conquests.[126]

Around the end of the 15th century, the military orders were transformed. Castile nationalized its orders between 1487 and 1499. In 1523, the Hospitallers retreated from Rhodes to Crete and Sicily and in 1530 to Malta and Gozo. The State of the Teutonic Order became the hereditary Duchy of Prussia when the last Prussian master, Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach, converted to Lutheranism and became the first duke under oath to his uncle the Polish king.[127]

16th century

In the 16th century, the rivalry between Catholic monarchs prevented anti-Protestant crusades, but individual military actions were rewarded with crusader privileges, including Irish Catholic rebellions against English Protestant rule and the Spanish Armada's attack on England under Queen Elizabeth I.[128] In 1562, Cosimo I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, became the hereditary Grand Master of the Order of Saint Stephen, a Tuscan military order he founded, which was modelled on the knights of Malta.[129] The Hospitallers remained the only independent military order with a positive strategy. Other orders continued as aristocratic corporations while lay powers absorbed local orders, outposts, and priories.[130] Political concerns provoked self-interested polemics that mixed the legendary and historical past. Humanist scholarship and theological hostility created an independent historiography. The rise of the Ottomans, the French Wars of Religion, and the Protestant Reformation encouraged the study of crusading. Some Roman Catholic writers considered the crusades gave precedents for dealing with heretics. It was thought that the crusaders were sincere, but there was increasing uneasiness with considering war as a religious exercise as opposed to having a territorial objective.[34]

17th century and later

Crusading continued in the 17th century, mainly associated with the Hapsburgs and the Spanish national identity. Crusade indulgences and taxation were used in support of the Cretan War (1645–1669), the Battle of Vienna, and the Holy League (1684). Although the Hospitallers continued the military orders in the 18th century, the crusading movement soon ended in terms of acquiescence, popularity, and support.[131]

The French Revolution resulted in widespread confiscations from the military orders, which were now largely irrelevant, apart from minor effects in the Hapsburg Empire.[130] The Hospitallers continued acting as a military order from its territory in Malta until the island was conquered by Napoleon in 1798.[118][132] In 1809, Napoleon went on to suppress the Order of St Stephen, and the Teutonic Order was stripped of its German possessions before relocating to Vienna. At this point, its identity as a military order ended.[129]

In 1936, the Catholic Church in Spain supported the coup of Francisco Franco, declaring a crusade against Marxism and atheism. Thirty-six years of National Catholicism followed, during which the idea of Reconquista as a foundation of historical memory, celebration, and Spanish national identity became entrenched in conservative circles. Reconquista lost its historiographical hegemony when Spain restored democracy in 1978, but it remains a fundamental definition of the medieval period within conservative sectors of academia, politics, and the media because of its strong ideological connotations.[133]

Legacy

Inspired by the first crusades, the crusading movement defined late medieval western culture and had an enduring impact on the history of the western Islamic world. This influence was in every area of life across Europe.[134] Christendom was geopolitical, and this underpinned the practice of the medieval Church. These ideas arose with the encouragement of the reformists of the 11th century and declined after the Reformation. The ideology of crusading continued after the 16th century with the military orders but dwindled in competition with other forms of religious war and new ideologies.[135]

Some historians have maintained that the Latin states in the Holy Land were the first experiment in western European colonialism, seeing the Outremer as a "Europe Overseas".[53][136] Certainly by the mid-19th century, the crusader states that had existed in the East were both a nationalist rallying point and emblematic of European colonialism.[137] This is a contentious issue, as others maintain that the Latin settlements in the Levant did not meet the accepted definition of a colony, that of territory politically directed by or economically exploited for the benefit of a homeland. Writers at the time did refer to colonists and migration, this means that academics find the concept of a religious colony useful, defined as territory captured and settled for religious reasons whose inhabitants maintain contact with their homelands due to a shared faith, and the need for financial and military assistance.[138] That said, the crusading movement led directly to the occupation of the Byzantine Empire by western colonists after the Fourth Crusade. In Venetian Greece, the relationship with Venice and the political and economic direction the city provided matches the more conventional definition of colonialism. In fact, its prosperity and relative safety drained settlers from the Latin East, which weakened the religious colonies of the Levant.[138]

The raising, transporting, and supply of large armies led to a flourishing trade between Europe and the Outremer. The Italian city-states of Genoa and Venice flourished, planting profitable trading colonies in the eastern Mediterranean.[139] The crusades consolidated the papal leadership of the Latin Church, reinforcing the link between the Catholic Church, feudalism, and militarism, and increased the tolerance of the clergy for violence.[53] Muslim libraries contained classical Greek and Roman texts that allowed Europe to rediscover pre-Christian philosophy, science, and medicine.[140] Opposition to the growth of the system of indulgences became a catalyst for the Reformation in the early 16th century.[141] The crusades also had a role in the formation and institutionalisation of the military and the Dominican orders as well as of the Medieval Inquisition.[142]

The behaviour of the crusaders in the eastern Mediterranean area appalled the Greeks and Muslims, creating a lasting barrier between the Latin world and the Islamic and Eastern Christian regions. This became an obstacle to the reunification of the Christian churches and fostered a perception of Westerners as defeated aggressors.[53] Many historians argue that the interaction between the western Christian and Islamic cultures played an ultimately positive part in the development of European civilization and the Renaissance.[143] Relations between Europeans and the Islamic world stretched across the entire length of the Mediterranean Sea, leading to an improved perception of Islamic culture in the West. But this broad area of interaction also makes it difficult for historians to identify the specific sources of cultural cross-fertilisation.[144]

Historical parallelism and the tradition of drawing inspiration from the Middle Ages have become keystones of political Islam, encouraging ideas of modern jihad and long struggle, while secular Arab nationalism highlights the role of Western imperialism.[145] Muslim thinkers, politicians, and historians have drawn parallels between the crusades and modern political developments such as the League of Nations mandates to govern Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, then the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine.[146] Right-wing circles in the Western world have drawn opposing parallels, considering Christianity to be under an Islamic religious and demographic threat that is analogous to the situation at the time of the crusades. Advocates present crusader symbols and anti-Islamic rhetoric as an appropriate response, even if only for propaganda. These symbols and rhetoric are used to provide a religious justification and inspiration for a struggle against a religious enemy.[147] Some historians, such as Thomas F. Madden, argue that modern tensions result from a constructed view of the crusades created by colonial powers in the 19th century, which provoked Arab nationalism. For Madden, the crusades are a medieval phenomenon in which the crusaders were engaged in a defensive war on behalf of their co-religionists.[148]

Historiography

The description and interpretation of crusading began with accounts of the First Crusade. The image and morality of the first expeditions served as propaganda for new campaigns.[149] The understanding of the crusades was based on a limited set of interrelated texts. Gesta Francorum (Exploits of the Franks) created a papist, northern French, and Benedictine template for later works that contained a degree of martial advocacy that attributed both success and failure to God's will.[150] This clerical view was challenged by vernacular adventure stories based on the work of Albert of Aachen. William of Tyre expanded Albert's writing in his Historia, which was completed by 1200. His work described the warrior state the Outremer became as a result of the tension between the providential and the worldly.[151] Medieval crusade historiography predominately remained interested in moralistic lessons, extolling the crusades as moral and cultural norms.[152] Academic crusade historian Paul Chevedden argued that these accounts are anachronistic, in that they were aware of the success of the First Crusade. He argues that, to understand the state of the crusading movement in the 11th century, it is better to examine the works of Urban II who died unaware of the outcome.[153]

Independent historiography emerged in the 15th century and was informed by humanism and hostility to theology. This grew in popularity in the 16th century, encouraged by events such as the rise of the Ottoman Turks, the French Wars of Religion, and the Protestant Reformation. Traditional crusading provided exemplars of redemptive solutions that were, in turn, disparaged as papal idolatry and superstition. War against the infidel was laudable, but crusading movement doctrines were not. Popes persisted in issuing crusade bulls for generations, but international laws of war that discounted religion as a cause were developed.[34] A nationalist view developed, providing a cultural bridge between the papist past and Protestant future based on two dominant themes for crusade historiography: firstly, intellectual, or religious disdain; and secondly, national, or cultural admiration. Crusading now had only a technical impact on contemporary wars but provided imagery of noble and lost causes. Opinions of crusading moved beyond the judgment of religion and increasingly depicted crusades as models of the distant past that were either edifying or repulsive.[154]

18th century Age of Enlightenment philosopher historians narrowed the chronological and geographical scope to the Levant and the Outremer between 1095 and 1291. There were attempts to set the number crusades at eight while others counted five large expeditions that reached the eastern Mediterranean – 1096–1099, 1147–1149, 1189–1192, 1217–1229, and 1248–1254. In the absence of an Ottoman threat, influential writers considered crusading in terms of anticlericalism, viewing crusading with disdain for its apparent ignorance, fanaticism, and violence.[155] By the 19th century, crusade enthusiasts disagreed with this view as being unnecessarily hostile and ignorant.[156]

Increasingly positive views of the Middle Ages developed in the 19th century. A fascination with chivalry developed to support the moral, religious, and cultural mores of established society. In a world of unsettling change and rapid industrialization, nostalgic escapist apologists and popular historians developed a positive view of crusading.[157] Jonathan Riley-Smith considers that much of the popular understanding of the crusades derives from the 19th century novels of Sir Walter Scott and the French histories of Joseph François Michaud. Michaud married admiration of supremacist triumphalism – supporting the nascent European commercial and political colonialism of the Middle East – to the point where the Outremer were "Christian colonies". The Franco-Syrian society in the Outremer became seen as benevolent, an attractive idea justifying the French mandates in Syria and Lebanon. In 1953, Jean Richard described the kingdom of Jerusalem as "the first attempt by the Franks of the West to found colonies". In the absence of widespread warfare, 19th century Europe created a cult of war based on the crusades, linked to political polemic and national identities. After World War I, crusading no longer received the same positive responses; war was now sometimes necessary but not good, sanctified, or redemptive.[158] Michaud's viewpoint provoked Muslim attitudes. The crusades had aroused little interest among Islamic and Arabic scholars until the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the penetration of European power.[159]

Jonathan Riley-Smith straddles the two schools regarding the motives and actions of early crusaders. The definition of a crusade remains contentious. Historians accept Riley-Smith's view that "everyone accepted that the crusades to the East were the most prestigious and provided the scale against which the others were measured". There is disagreement whether only those campaigns launched to recover or protect Jerusalem were proper crusades or whether those wars to which popes applied temporal and spiritual authority were equally legitimate. Today, crusade historians study the Baltic, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and even the Atlantic, and crusading's position in, and derivation from, host and victim societies. Chronological horizons have crusades existing into the early modern world, e.g. the survival of the Order of St. John on Malta until 1798.[160] The academic study of crusading in the West has integrated mainstream theology, the Church, law, popular religion, aristocratic society and values, and politics. The Muslim context now receives attention from Islamicists. Academics have replaced disdain with attempts to situate crusading within its social, cultural, intellectual, economic, and political context. Historians employ a wide range of evidence, including charters, archaeology, and the visual arts, to supplement chronicles and letters. Local studies have lent precision as well as diversity.[160]

The Byzantines harboured a negative perspective on holy warfare, failing to grasp the concept of the Crusades and finding them repugnant. Although some initially embraced Westerners due to a common Christianity, their trust soon waned. With a pragmatic approach, the Byzantines prioritised strategic locations such as Antioch over sentimental objectives like Jerusalem. They couldn't comprehend the merging of pilgrimage and warfare. The advocacy for infidel eradication by St. Bernard and the militant role of the Templars would deeply shock them. Suspicions arose among the Byzantines that Westerners aimed for imperial conquest, leading to growing animosity. Despite occasionally using the term "holy war" in historical contexts, Byzantine conflicts were not inherently holy but perceived as just, defending the empire and Christian faith. War, to the Byzantines, was justified solely for the defence of the empire, in contrast to Muslim expansionist ideals and Western knights' notion of holy warfare to glorify Christianity.[162]

Scholarly exploration of the Crusades from Arabic and Muslim perspectives faces considerable challenges due to the loss or lack of translation of many relevant sources. Within existing works, references to the crusading movement are sporadic, often lacking in detail, and embedded in broader historical narratives. The paradigms of the Crusades were foreign to medieval Muslims, who viewed the primary motivation of the crusaders as rooted in greed.[163] Notably, scholars like Carole Hillenbrand assert that within the broader context of historical events, the Crusades were considered a marginal issue when compared to the collapse of the Caliphate, the Mongol invasions, and the rise of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, supplanting Arab rule.[164] Arab historians, influenced by historical opposition to Turkish control over their homelands, adopted a Western perspective on the Crusades.[164] Syrian Christians proficient in Arabic played a vital role by translating French histories into Arabic. The first modern biography of Saladin was authored by the Ottoman Turk Namık Kemal in 1872, while the Egyptian Sayyid Ali al-Hariri produced the initial Arabic history of the Crusades in response to Kaiser Wilhelm II's visit to Jerusalem in 1898.[165] The visit triggered a renewed interest in Saladin, who had previously been overshadowed by more recent leaders like Baybars. The reinterpretation of Saladin as a hero against Western imperialism gained traction among nationalist Arabs, fueled by anti-imperialist sentiment.[166] The intersection of history and contemporary politics is evident in the development of ideas surrounding jihad and Arab nationalism. Historical parallels between the Crusades and modern political events, such as the establishment of Israel in 1948, have been drawn.[167] In contemporary Western discourse, right-wing perspectives have emerged, viewing Christianity as under threat analogous to the Crusades, using crusader symbols and anti-Islamic rhetoric for propaganda purposes.[168] Madden argues that Arab nationalism absorbed a constructed view of the Crusades created by colonial powers in the 19th century, contributing to modern tensions. Madden suggests that the crusading movement, from a medieval perspective, engaged in a defensive war on behalf of co-religionists.[169]

See also

- History of the Jews and the Crusades

- List of principal crusaders

- List of Crusader castles

- Women in the Crusades

- Criticism of crusading

References

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. xxiii.

- ^ a b Riley-Smith 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Morris 1989, p. 81.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 110.

- ^ Morris 1989, p. 144.

- ^ Lock 2006, p. 277.

- ^ Latham 2011, p. 240.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 108.

- ^ Morris 1989, p. 338.

- ^ Latham 2011, pp. 240–241.

- ^ a b c Maier 2006a, pp. 627–629.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 14–16, 338, 359.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 98.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 14.

- ^ a b Tyerman 2011, p. 61.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 18–19, 289.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Jotischky 2004, pp. 30–38.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d Bird 2006d, pp. 546–547.

- ^ a b Jotischky 2004, pp. 195–198.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 123.

- ^ a b c Blumenthal 2006, pp. 1214–1217.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995b, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d Riley-Smith 1995, p. 2.

- ^ a b Blumenthal 2006c, pp. 202–203.

- ^ a b MacEvitt 2006a.

- ^ a b Tyerman 2019, pp. 235–237.

- ^ a b Asbridge 2012, pp. 524–525.

- ^ a b Asbridge 2012, pp. 533–535.

- ^ a b Tyerman 2019, pp. 238–239.

- ^ a b c d Tyerman 2006c, pp. 582–583.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Bull 1995, p. 22.

- ^ a b Flori 2006, p. 244.

- ^ a b Flori 2006, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Morris 1989, p. 150.

- ^ Flori 2006, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Lloyd 1995, p. 45.

- ^ Honig 2001, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Flori 2006, p. 246-247.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 53.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, p. 50.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, p. 64.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995b, p. 84.

- ^ Prawer 2001, p. 252

- ^ Asbridge 2012, p. 169

- ^ Prawer 2001, p. 253

- ^ Asbridge 2012, p. 168

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 169–170

- ^ a b c d Davies 1997, p. 359

- ^ Bull 1995, p. 25.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Lloyd 1995, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 263.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. xxv.

- ^ Dickson 2008, p. xiii.

- ^ Dickson 2008, pp. 9–14.

- ^ Dickson 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Jubb 2005, p. 226.

- ^ Routledge 1995, p. 93

- ^ Jubb 2005, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Jubb 2005, p. 229.

- ^ Jubb 2005, p. 232.

- ^ Jubb 2005, pp. 234–235.

- ^ Routledge 1995, pp. 95–99

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 120.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 118.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 117.

- ^ Flori 2006, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 124.

- ^ a b Flori 2006, p. 248.

- ^ Latham 2012, p. 116.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, p. 36.

- ^ Routledge 1995, pp. 91–92

- ^ Routledge 1995, pp. 93–94

- ^ Routledge 1995, p. 111

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995b, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Blumenthal 2006b, pp. 933–934.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995b, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Dickson 2006, pp. 975–979.

- ^ Morris 1989, p. 478.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Buck 2020, p. 298.

- ^ Maier 2006a, pp. 629–630.

- ^ Barber 2012, p. 408.

- ^ Dickson 2008, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Forey 1995, p. 196.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 117.

- ^ Maier 2006b, pp. 984–988.

- ^ a b Cordery 2006, pp. 399–403.

- ^ Madden 2013, p. 155.

- ^ Housley 2002, p. 29.

- ^ Mannion 2014, p. 21.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 330.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, p. 46.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 336.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, p. 223.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 258–260.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 620.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 648.

- ^ Jotischky 2004, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Bird 2006c, p. 41.

- ^ a b Siberry 2006, p. 300.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 247.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, p. 28.

- ^ Tyerman 2006c, p. 314.

- ^ Siberry 2006, pp. 299–301.

- ^ a b c MacEvitt 2006c.

- ^ Forey 1995, p. 211.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 260.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, p. 57.

- ^ Housley 1995, pp. 262–265.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 275.

- ^ a b Riley-Smith 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 270.

- ^ a b c Housley 1995, p. 281.

- ^ MacEvitt 2006b.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 279.

- ^ Orth 2006, pp. 996–997.

- ^ Housley 1995, pp. 279–280.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 264.

- ^ Bird 2006b, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Luttrell 1995, pp. 348.

- ^ Tyerman 2019, pp. 358–359.

- ^ a b Luttrell 1995, p. 352.

- ^ a b Luttrell 1995, p. 364.

- ^ Housley 1995, p. 293.

- ^ Luttrell 1995, p. 360.

- ^ García-Sanjuán 2018, p. 4

- ^ Riley-Smith 1995, pp. 4–5, 36.

- ^ Maier 2006a, pp. 630–631.

- ^ Morris 1989, p. 282.

- ^ Madden 2013, p. 227

- ^ a b Phillips 1995, pp. 112–113

- ^ Housley 2006, pp. 152–154

- ^ Nicholson 2004, pp. 93–94

- ^ Housley 2006, pp. 147–149

- ^ Strayer 1992, p. 143

- ^ Nicholson 2004, p. 96

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 667–668

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 675–680

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 674–675

- ^ Koch 2017, p. 1

- ^ Madden 2013, pp. 204–205

- ^ Tyerman 2006c, p. 582.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 8–12.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, p. 32.

- ^ Chevedden 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Tyerman 2006c, pp. 583–584.

- ^ Tyerman 2006c, p. 584.

- ^ Tyerman 2011, pp. 71, 79.

- ^ Tyerman 2006c, pp. 584–585.

- ^ Tyerman 2006c, p. 586.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 675–680.

- ^ a b Tyerman 2006c, p. 587.

- ^ France 2006, p. 81.

- ^ Dennis 2001, pp. 31–40.

- ^ Christie 2006, p. 81.

- ^ a b Hillenbrand 1999, p. 5.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 675–677.

- ^ Riley-Smith 2009, pp. 6–66.

- ^ Asbridge 2012, pp. 674–675.

- ^ Koch 2017, p. 1.

- ^ Madden 2013, pp. 204–205.

Bibliography

- Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84983-688-3.

- Barber, Malcolm (2012). The Two Cities: Medieval Europe 1050-1320. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17414-7.

- Bird, Jessalynn (2006b). "Alexander VI". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I:A-C. ABC-Clio. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Bird, Jessalynn (2006c). "Alexander IV". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. I:A-C. ABC-CLIO. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Bird, Jessalynn (2006d). "Gregory IX, Pope (d. 1241)". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. II:D-J. ABC-CLIO. pp. 546–547. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.

- Blumenthal, Uta-Renate [in German] (2006). "Urban II". In Murray, Alan V. (ed.). The Crusades: An Encyclopedia. Vol. IV:Q-Z. ABC-Clio. pp. 1214–1217. ISBN 978-1-57607-862-4.