Writing system

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Writing systems |

|---|

|

| Abjad |

| Abugida |

| Alphabetical |

| Logographic |

| Syllabic |

| Hybrids |

|

Japanese (Logographic and syllabic) Hangul (Alphabetic and syllabic) |

A writing system comprises a particular set of symbols, called a script, as well as the rules by which the script represents a particular language. Writing systems can generally be classified according to how symbols function according to these rules, with the most common types being alphabets, syllabaries, and logographies. Alphabets use symbols called letters that correspond to spoken phonemes. Abjads generally only have letters for consonants, while pure alphabets have letters for both consonants and vowels. Abugidas use characters that correspond to consonant–vowel pairs. Syllabaries use symbols called syllabograms to represent syllables or moras. Logographies use characters that represent semantic units, such as words or morphemes.

Alphabets typically use fewer than 100 symbols, while syllabaries and logographies may use hundreds or thousands respectively. Writing systems also include punctuation to aid interpretation and encode additional meaning, including that which is communicated verbally by qualities such as rhythm, tone, pitch, accent, inflection or intonation.

Writing was first invented in the late 4th millennium BC. Each independently invented writing system in human history evolved from a system of proto-writing not fully capable of encoding spoken language. These systems used a small number of ideograms, but were not fully capable of encoding spoken language, and lacked the ability to express a broad range of ideas.

General properties

Writing systems are distinguished from other symbolic communication systems in that a writing system is always associated with at least one spoken language. In contrast, visual representations such as drawings, paintings, and non-verbal features of maps, such as contour lines, are not language-related. Some symbols on informational signs, such as the symbols for male and female, are also not language related, but can grow to become part of language if they are often used in conjunction with language elements. Some other symbols, such as numerals and the ampersand, are not directly linked to any specific language, but are used in writing and thus must be considered part of writing systems.

Every human community possesses language, and language is arguably an innate and defining condition of humanity. However, the development of writing systems and the process by which they have supplanted traditional oral systems of communication have been sporadic, uneven and slow. Once established, writing systems generally change more slowly than their spoken counterparts. Thus they often preserve features and expressions which are no longer present in the spoken language. One of the great benefits of writing systems is that they can preserve a permanent record of information expressed in a language.

All writing systems require a set of defined base elements, individually termed signs or graphemes and collectively called a script.[1] The orthography of the writing system is the set of rules and conventions understood and shared by a community, which assigns meaning to the ordering of and relationship between the graphemes. The orthography represents the constructions of at least one (generally spoken) language.

Writing systems also require some physical means of representing symbols in a permanent or semi-permanent medium where the symbols may then be interpreted, for example writing may be done by pen on paper. Writing systems are usually visual, but tactile writing systems also exist.

The exact relationship between writing systems and languages can be complex. A single language (e.g. Hindustani) can have multiple writing systems, and a writing system can also represent multiple languages. Chinese characters, for example, represent multiple spoken languages within China, and also were the early writing system for the Vietnamese language until Vietnamese switched to the Latin script.

Basic terminology

The terminology used to describe writing systems differs somewhat from field to field.

Text, writing, reading and orthography

The generic term text[2] refers to an instance of written material, or spoken material that has been transcribed in some way. The act of composing and recording a text may be referred to as writing,[3] and the act of viewing and interpreting the text as reading.[4] Orthography (lit. 'correct writing') refers to the structural method and rules of writing, and, particularly for alphabetic systems, includes the concept of spelling.

Grapheme and phoneme

A grapheme is a specific base unit of a writing system. They are the minimally significant elements which taken together comprise the set of "building blocks" out of which texts may be constructed. The concept of the grapheme is similar to that of the phoneme used in the study of spoken languages. For example, in the writing system of standard contemporary English, examples of graphemes include the uppercase and lowercase forms of the twenty-six letters of the Latin alphabet (with these graphemes corresponding to various phonemes), punctuation marks (mostly non-phonemic), and a few other symbols such as Arabic numerals (logograms representing numbers).

An individual grapheme may be represented in a wide variety of ways, where each variation is visually distinct in some regard, but all are interpreted as representing the "same" grapheme. These individual variations are known as allographs of a grapheme. For example, the lowercase letter a has different allographs when written as a cursive, block, or typed letter. The choice of a particular allograph may be influenced by the medium used, the writing instrument used, the stylistic choice of the writer, the preceding and succeeding graphemes in the text, the time available for writing, the intended audience, and the largely unconscious features of an individual's handwriting.

Glyph, sign and character

The terms glyph, sign and character are sometimes used to refer to graphemes. Glyphs in linear writing systems are made up of lines or strokes. Linear writing is most common, but there are non-linear writing systems where glyphs consist of other types of marks, such as in cuneiform and Braille.

Complete and partial writing systems

Writing systems may be regarded as complete if they are able to represent all that may be expressed in the spoken language, while a partial writing system cannot represent the spoken language in its entirety.[5]

History

Proto-writing systems

Writing systems were preceded by proto-writing systems consisting of ideograms and early mnemonic symbols. The best-known examples are:

- "Token system", a recording system used for accounting purposes in Mesopotamia c. 9000 BC[6]

- Jiahu symbols, carved on tortoise shells in Jiahu, c. 6600 BC

- Vinča symbols (Tărtăria tablets), c. 5300 BC

- Proto-cuneiform c. 3500 BC[7]

- Possibly the early Indus script, c. 3500 BC, as its nature is disputed[8][better source needed]

- Nsibidi script, c. before 500 AD[citation needed]

Invention of writing systems

Writing has been invented independently multiple times in human history.

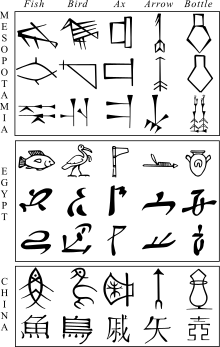

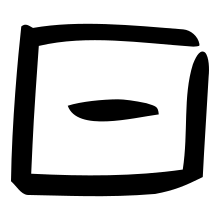

The invention of the first writing systems is roughly contemporary with the beginning of the Bronze Age following the late Neolithic in the late 4th millennium BC. The archaic cuneiform script used to write Sumerian is generally considered to be the earliest true writing system, closely followed by the Egyptian hieroglyphs. Both evolved from proto-writing systems between 3400 and 3200 BC, with the earliest coherent texts dating to c. 2600 BC. It is generally agreed that the two systems were invented independently from one another.

Chinese characters were developed independently c. 1200 BC in the Yellow River valley. There is no evidence of contact between China and the literate peoples of the Near East, and the Mesopotamian and Chinese approaches to logography and phonetic representation are distinct.[9][10][11]

The Mesoamerican writing systems, including Olmec and the Maya scripts, were also invented independently. Additionally, in North America, a set of symbols used by pre-colonial Mi'kmaq is also thought to have developed independently, although it remains unknown whether these symbols constitute a fully formed writing system or just a series of mnemonic pictographs.

Alphabetic writing

The first known consonantal alphabetic writing appeared before 2000 BC, and was used to write a Semitic language spoken in the Sinai Peninsula. Most of the world's alphabets either descend directly from this Proto-Sinaitic script, or were directly inspired by its design. Descendants include the Phoenician alphabet and its child system, the Greek alphabet—which in 800 BC became was the first system to represent vowels.[12][13] The Latin alphabet, which descended from the Greek alphabet, is by far the most common writing system in use.[14]

Functional classification

Several approaches have been taken to classify writing systems, the most common and basic one being a broad division into three categories: logographic, syllabic, and alphabetic (or segmental). Logographies use characters that represent semantic units, such as words or morphemes. Syllabaries use symbols called syllabograms to represent syllables or moras. Alphabets use symbols called letters that correspond to spoken phonemes. Alphabets consist of three types: Abjads generally only have letters for consonants, while pure alphabets have letters for both consonants and vowels. Abugidas use characters that correspond to consonant–vowel pairs.

Along these lines, linguist David Diringer proposed a classification of five types of writing systems: pictographic script, ideographic script, analytic transitional script, phonetic script, alphabetic script[15]

However, a single writing system may include aspects of multiple of these categories in different proportions, often making it difficult to categorise a system uniquely. The term complex system is sometimes used to describe those where the mixture makes classification problematic. Modern linguists, therefore, often regard this type of categorization of writing systems as too simplistic.

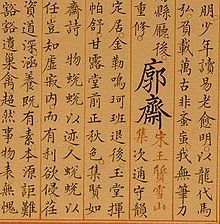

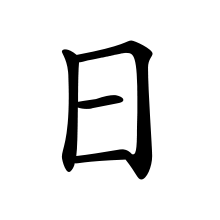

Logographic systems

A logogram is a character that represents a morpheme within a language. The most important (and, to a degree, the only surviving) modern logographic writing system is the Chinese one, whose characters have been used with varying degrees of modification in varieties of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and other east Asian languages. Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and the Mayan writing system are also systems with certain logographic features, although they have marked phonetic features as well and are no longer in current use.

In Chinese, each character represents a syllabic morpheme, or, occasionally half of a morpheme for very limited numbers of disyllabic morphemes. In such a system, se(x)dec-, hexa(kai)deca-, hexadec- and sixteen would all be written with the same set of two logograms, one logogram for all cognates for six and one for all cognates for -teen, leaving the reader to choose whether to read it in the Greek way or the Roman way, or mixed Greco-Roman way, although conventions inform and constrain the reader's choice.

As each character represents a single word (or, more precisely, a morpheme), many different logograms are required in order to write all the words of a language. If the logograms do not adequately represent all meanings and words of a language, written language can be confusing or ambiguous to the reader. The vast array of logograms and the need to remember what they all mean are considered by many as major disadvantages of logographic systems compared to alphabetic systems.

Since the meaning is inherent to the symbol, the same logographic system could theoretically be used to write different spoken languages. In practice, the ability to communicate across languages works best in closely related languages, like the varieties of Chinese, and works only to a lesser extent for less closely related languages, as differences in syntax reduce the cross-linguistic portability of a given logographic system. For example, Japanese uses Chinese logograms (known as kanji) extensively in its writing systems, with most (but not all) of the symbols carrying the same or similar meanings as in Chinese. As a result, short and concise phrases written in Chinese such as those on signs and in newspaper headlines are often easy for a Japanese reader to comprehend. However, the grammatical differences between Japanese and Chinese are large enough that a long Chinese text is not readily understandable to a Japanese reader without knowledge of basic Chinese grammar. Similarly, a Chinese reader can get a general idea of what a long Japanese kanji text means, but usually cannot understand the text fully.

While most languages do not use wholly logographic writing systems, many languages use a few logograms. A good example of modern western logograms is the Arabic numerals: readers across many different languages understand what 1 means whether they read it as one, eins, uno, yi, ichi, ehad, ena, or jedan. Other western logograms include the ampersand &, used for and, the at sign @, used in many contexts for at, the percent sign % and the many signs representing units of currency ($, ¢, €, £, ¥ and so on).

The apostrophe can also be regarded as a logogram, corresponding to the kana の in Japanese.[further explanation needed]

Logograms are sometimes called ideograms, a word that refers to symbols which graphically represent abstract ideas, but linguists avoid this term, as Chinese characters are often semantic–phonetic compounds, symbols which include an element that represents the meaning and a phonetic complement element that represents the pronunciation. Some non-linguists distinguish between lexigraphy and ideography, where symbols in lexigraphies represent words and symbols in ideographies represent morphemes.

Syllabaries

A syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent (or approximate) syllables, which make up words. A symbol in a syllabary typically represents a consonant sound followed by a vowel sound, or just a vowel alone.

In a "true syllabary", there is no systematic graphic similarity between phonetically related characters (though some do have graphic similarity for the vowels). That is, the characters for /ke/, /ka/ and /ko/ have no similarity to indicate their common "k" sound (voiceless velar plosive). Some more recently created writing systems such as the Cree syllabary are not true syllabaries, but instead use related symbols for phonetically similar syllables.

Syllabaries are best suited to languages with relatively simple syllable structure, since a different symbol is needed for every syllable. Japanese, for example, contains about 100 syllables, which are represented by the syllabic Hiragana characters. The English language, on the other hand, uses complex syllable structures with a relatively large inventory of vowels and complex consonant clusters, adding up to about 15,000 to 16,000 different syllables, which would make it cumbersome to write English words with a syllabary..

Syllabaries with much larger character inventories do exist. The Yi script, for example, contains 756 different symbols (or 1,164, if symbols with a particular tone diacritic are counted as separate syllables, as in Unicode). Because words in the Chinese languages are generally one syllable, characters in the Chinese script also represent syllables, when used to write any of the varieties of Chinese, and the script includes separate glyphs for nearly all of the many thousands of syllables in Middle Chinese; however, because it primarily represents morphemes and includes different characters to represent homophonous morphemes with different meanings, the Chinese script is normally considered a logography rather than a syllabary.

Other languages that use true syllabaries include Mycenaean Greek (Linear B) and Indigenous languages of the Americas such as Cherokee. Several languages of the Ancient Near East used forms of cuneiform, which is a syllabary with some non-syllabic elements.

Alphabets

An alphabet is a small set of letters (basic written symbols), each of which roughly represents or represented historically a segmental phoneme of a spoken language. The word alphabet is derived from alpha and beta, the first two symbols of the Greek alphabet.

The first type of alphabet that was developed was the abjad. An abjad is an alphabetic writing system where there is one symbol per consonant. Abjads differ from other alphabets in that they have characters only for consonantal sounds. Vowels are not usually marked in abjads. All known abjads (except maybe Tifinagh, which is used to write the Berber languages) belong to the Semitic family of scripts, and derive from the original Northern Linear Abjad. Semitic languages and the related Berber languages have a morphemic structure which makes the denotation of vowels redundant in most cases.

Some abjads, like Arabic and Hebrew, have markings for vowels as well. However, they use them only in special contexts, such as for teaching. Many scripts derived from abjads have been extended with vowel symbols to become full alphabets. Of these, the most famous example is the derivation of the Greek alphabet from the Phoenician abjad. This has mostly happened when the script was adapted to a non-Semitic language. The term abjad takes its name from the old order of the Arabic alphabet's consonants 'alif, bā', jīm, dāl, though the word may have earlier roots in Phoenician or Ugaritic. "Abjad" is the word for alphabet in Arabic, Malay and Indonesian.

An abugida is an alphabetic writing system whose basic signs denote consonants with an inherent vowel and where consistent modifications of the basic sign indicate other following vowels than the inherent one. Thus, in an abugida there may or may not be a sign for "k" with no vowel, but also one for "ka" (if "a" is the inherent vowel), and "ke" is written by modifying the "ka" sign in a way that is consistent with how one would modify "la" to get "le". In many abugidas the modification is the addition of a vowel sign, but other possibilities are imaginable (and used), such as rotation of the basic sign, addition of diacritical marks and so on.

The contrast with "true syllabaries" is that the latter have one distinct symbol per possible syllable, and the signs for each syllable have no systematic graphic similarity. The graphic similarity of most abugidas comes from the fact that they are derived from abjads, and the consonants make up the symbols with the inherent vowel and the new vowel symbols are markings added on to the base symbol. In the Ge'ez script, for which the linguistic term abugida was named, the vowel modifications do not always appear systematic, although they originally were more so.

Canadian Aboriginal syllabics can be considered abugidas, although they are rarely thought of in those terms. The largest single group of abugidas is the Brahmic family of scripts, however, which includes nearly all the scripts used in India and Southeast Asia. The name abugida is derived from the first four characters of an order of the Ge'ez script used in some contexts. It was borrowed from Ethiopian languages as a linguistic term by Peter T. Daniels.

Featural systems

A featural script represents finer detail than an alphabet. Here symbols do not represent whole phonemes, but rather the elements (features) that make up the phonemes, such as voicing or its place of articulation. Theoretically, each feature could be written with a separate letter; and abjads or abugidas, or indeed syllabaries, could be featural, but the only prominent system of this sort is Korean hangul. In hangul, the featural symbols are combined into alphabetic letters, and these letters are in turn joined into syllabic blocks, so that the system combines three levels of phonological representation.

Many scholars, e.g. John DeFrancis, reject this class or at least labeling hangul as such.[citation needed] The Korean script is a conscious script creation by literate experts, which Daniels calls a "sophisticated grammatogeny".[citation needed] These include stenographies and constructed scripts of hobbyists and fiction writers (such as Tengwar), many of which feature advanced graphic designs corresponding to phonologic properties. The basic unit of writing in these systems can map to anything from phonemes to words. It has been shown that even the Latin script has sub-character "features".[16]

Ambiguous systems

Most writing systems are not purely one type. The English writing system, for example, includes numerals and other logograms such as #, $, and &, and the written language often does not match well with the spoken one. As mentioned above, all logographic systems have phonetic components as well, whether along the lines of a syllabary, such as Chinese ("logo-syllabic"), or an abjad, as in Egyptian ("logo-consonantal").

Some scripts, however, are truly ambiguous. The semi-syllabaries of ancient Spain were syllabic for plosives such as p, t, k, but alphabetic for other consonants. In some versions, vowels were written redundantly after syllabic letters, conforming to an alphabetic orthography. Old Persian cuneiform was similar. Of 23 consonants (including null), seven were fully syllabic, thirteen were purely alphabetic, and for the other three, there was one letter for /Cu/ and another for both /Ca/ and /Ci/. However, all vowels were written overtly regardless; as in the Brahmic abugidas, the /Ca/ letter was used for a bare consonant.

The zhuyin phonetic glossing script for Chinese divides syllables in two or three, but into onset, medial, and rime rather than consonant and vowel. Pahawh Hmong is similar, but can be considered to divide syllables into either onset-rime or consonant-vowel (all consonant clusters and diphthongs are written with single letters); as the latter, it is equivalent to an abugida but with the roles of consonant and vowel reversed. Other scripts are intermediate between the categories of alphabet, abjad and abugida, so there may be disagreement on how they should be classified.

Alternative categorizations of writing systems

Modern linguists have proposed a number of alternative ways to categorize writing systems.

Archibald Hill[17] split writing into three major categories of linguistic analysis, one of which covers discourses and is not usually considered writing proper:

- discourse system

- iconic discourse system, e.g. Amerindian

- conventional discourse system, e.g. Quipu

- morphemic writing system, e.g. Egyptian, Sumerian, Maya, Chinese, Anatolian Hieroglyphs

- phonemic writing system

- partial phonemic writing system, e.g. Egyptian, Hebrew, Arabic

- poly-phonemic writing system, e.g. Linear B, Kana, Cherokee

- mono-phonemic writing system

- phonemic writing system, e.g. Ancient Greek, Old English

- morpho-phonemic writing system, e.g. German, Modern English

Computational linguist Geoffrey Sampson draws a distinction between semasiography and glottography:

- semasiography, relating visible marks to meaning directly without reference to any specific spoken language

- glottography, using visible marks to represent forms of a spoken language

- logography, representing a spoken language by assigning distinctive visible marks to linguistic elements of André Martinet's "first articulation" (Martinet 1949), i.e. morphemes or words

- phonography, achieving the same goal by assigning marks to elements of the "second articulation", e.g. phonemes, syllables

DeFrancis,[18] criticizing Sampson's[19] introduction of semasiographic writing and featural alphabets stresses the phonographic quality of writing proper

- pictures

- nonwriting

- writing

- rebus

- syllabic systems

- pure syllabic, e.g. Linear B, Yi, Kana, Cherokee

- morpho-syllabic, e.g. Sumerian, Chinese, Mayan

- consonantal

- morpho-consonantal, e.g. Egyptian

- pure consonantal, e.g. Phoenician

- alphabetic

- pure phonemic, e.g. Greek

- morpho-phonemic, e.g. English

- syllabic systems

- rebus

Faber[20] categorizes phonographic writing by two levels, linearity and coding:

- logographic, e.g. Chinese, Ancient Egyptian

- phonographic

- syllabically linear

- segmentally linear

- complete (alphabet), e.g. Greco-Latin, Cyrillic

- defective, e.g. Ugaritic, Phoenician, Aramaic, Old South Arabian, Paleo-Hebrew

| Type | Each symbol represents | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Logosyllabary | word or morpheme as well as syllable | Chinese characters |

| Syllabary | syllable | Japanese kana |

| Abjad (consonantary) | consonant | Arabic alphabet |

| Alphabet | consonant or vowel | Latin alphabet |

| Abugida | consonant accompanied by specific vowel, modifying symbols represent other vowels |

Indian Devanagari |

| Featural system | distinctive feature of segment | Korean Hangul |

Graphic classification

Perhaps the primary graphic distinction made in classifications is that of linearity. Linear writing systems are those in which the characters are composed of lines, such as the Latin alphabet and Chinese characters. Chinese characters are considered linear whether they are written with a ball-point pen or a calligraphic brush, or cast in bronze. Similarly, Egyptian hieroglyphs and Maya glyphs were often painted in linear outline form, but in formal contexts they were carved in bas-relief. The earliest examples of writing are linear: the Sumerian script of c. 3300 BC was linear, though its cuneiform descendants were not. Non-linear systems, on the other hand, such as braille, are not composed of lines, no matter what instrument is used to write them.

Cuneiform was probably the earliest non-linear writing. Its glyphs were formed by pressing the end of a reed stylus into moist clay, not by tracing lines in the clay with the stylus as had been done previously.[22][23] The result was a radical transformation of the appearance of the script.

Braille is a non-linear adaptation of the Latin alphabet that completely abandoned the Latin forms. The letters are composed of raised bumps on the writing substrate, which can be leather (Louis Braille's original material), stiff paper, plastic or metal.

There are also transient non-linear adaptations of the Latin alphabet, including Morse code, the manual alphabets of various sign languages, and semaphore, in which flags or bars are positioned at prescribed angles. However, if "writing" is defined as a potentially permanent means of recording information, then these systems do not qualify as writing at all, since the symbols disappear as soon as they are used. (Instead, these transient systems serve as signals.)

Directionality

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

Scripts are graphically characterized by the direction in which they are written. Egyptian hieroglyphs were written either left to right or right to left, with the animal and human glyphs turned to face the beginning of the line. The early alphabet could be written in multiple directions:[24] horizontally (side to side), or vertically (up or down). Prior to standardization, alphabetical writing was done both left-to-right (LTR or sinistrodextrally) and right-to-left (RTL or dextrosinistrally). It was most commonly written boustrophedonically: starting in one (horizontal) direction, then turning at the end of the line and reversing direction.

The Greek alphabet and its successors settled on a left-to-right pattern, from the top to the bottom of the page. Other scripts, such as Arabic and Hebrew, came to be written right-to-left. Scripts that historically incorporate Chinese characters (including Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese etc.) have traditionally been written, on the character-level, vertically (top-to-bottom), from the right to the left of the page, but nowadays are frequently written left-to-right, top-to-bottom, due to Western influence, a growing need to accommodate terms in the Latin script, and technical limitations in popular electronic document formats, and the fact that strokes are predominantly written from top to bottom ("丨", "丿", "㇏" or "丶") and left to right ("一"), so are their orders within every single character.

Chinese characters sometimes, as in signage, especially when signifying something old or traditional, may also be written from right to left if written horizontally, but this is a special case of the traditional "vertical (top-to-bottom), from the right to the left of the board" (tbrl) direction, although every column has only one character. No boards with more than two rows adopt the rltb direction, four characters forming a square must either follow tbrl or lrtb. The Old Uyghur alphabet (and some Sogdian) and its descendants are unique in being written top-to-bottom, left-to-right; this direction originated from an ancestral Semitic direction by rotating the page 90° counter-clockwise to conform to the appearance of vertical Chinese writing. However, except for Old Uyghur itself, all its descendant are quoted in lrtb articles with a rotated ltr directionality when vertical quoting is impractical. When Chinese characters are quoted in Mongolian articles, they will fit into a tblr scheme.

Several scripts used in the Philippines and Indonesia, such as Hanunó'o, are traditionally written with lines moving away from the writer, from bottom to top, but are read horizontally left to right; however, Kulitan, another Philippine script, is written top to bottom and right to left. Ogham is written bottom to top and read vertically, commonly on the corner of a stone. The ancient Libyco-Berber alphabet was also written from bottom to top.[25]

Left-to-right writing has the advantage that, since most people are right-handed,[26][27] the hand does not interfere with the just-written text—which might not yet have dried—since the hand is on the right side of the pen. Right-to-left writing, by contrast, may have been advantageous back when writing was done with hammer and chisel; the scribe would hold the hammer in their right hand and chisel in their left, and going right-to-left would mean the hammer was less likely to hit the left hand, as the right hand had more control.[28][29]

On computers

In computers and telecommunication systems, writing systems are generally not codified as such,[clarification needed] but graphemes and other grapheme-like units that are required for text processing are represented by "characters" that typically manifest in encoded form. There are many character encoding standards and related technologies, such as ISO/IEC 8859-1 (a character repertoire and encoding scheme oriented toward the Latin script), CJK (Chinese, Japanese, Korean) and bi-directional text.

Today, many such standards are re-defined in a collective standard, the ISO/IEC 10646 "Universal Character Set", and a parallel, closely related expanded work, The Unicode Standard. Both are generally encompassed by the term Unicode. In Unicode, each character, in every language's writing system, is (simplifying slightly) given a unique identification number, known as its code point. Computer operating systems use code points to look up characters in the font file, so the characters can be displayed on the page or screen.

A keyboard is the device most commonly used for writing via computer. Each key is associated with a standard code which the keyboard sends to the computer when it is pressed. By using a combination of alphabetic keys with modifier keys such as Ctrl, Alt, Shift and AltGr, various character codes are generated and sent to the CPU. The operating system intercepts and converts those signals to the appropriate characters based on the keyboard layout and input method, and then delivers those converted codes and characters to the running application software, which in turn looks up the appropriate glyph in the currently used font file, and requests the operating system to draw these on the screen.

See also

- List of writing systems

- Constructed script

- Calligraphy

- Defective script

- Digraphia

- Epigraphy

- Formal language

- Grammatology

- International phonetic alphabet

- ISO 15924

- Orthography

- Pasigraphy

- Penmanship

- Paleography

- Phonemic orthography

- Phonetic transcription

- Numeral system

- Transliteration

- Transcription (linguistics)

- Writing

- Written language

- X-SAMPA

References

- ^ Coulmas 2003, p. 35.

- ^ David Crystal (2008), A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics, 6th Edition, p. 481, Wiley

- ^ Hadumod Bußmann (1998), Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics, p. 1294, Taylor & Francis

- ^ Hadumod Bußmann (1998), Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics, p. 979, Taylor & Francis

- ^ Harriet Joseph Ottenheimer (2012), The Anthropology of Language: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology, p. 194, Cengage Learning

- ^ Denise Schmandt-Besserat, "An Archaic Recording System and the Origin of Writing." Syro-Mesopotamian Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–32, 1977

- ^ Woods, Christopher (2010), "The earliest Mesopotamian writing", in Woods, Christopher (ed.), Visible language. Inventions of writing in the ancient Middle East and beyond (PDF), Oriental Institute Museum Publications, 32, Chicago: University of Chicago, pp. 33–50, ISBN 978-1-885923-76-9

- ^ "Machine learning could finally crack the 4,000-year-old Indus script". 25 January 2017.

- ^ Robert Bagley (2004). "Anyang writing and the origin of the Chinese writing system". In Houston, Stephen (ed.). The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 9780521838610. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ William G. Boltz (1999). "Language and Writing". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press. p. 108. ISBN 9780521470308. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ David N. Keightley, Noel Barnard. The Origins of Chinese civilization. Page 415-416

- ^ Coulmas, Florian (1996). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd. ISBN 0-631-21481-X.

- ^ Millard 1986, p. 396

- ^ Haarmann 2004, p. 96

- ^ David Diringer (1962): Writing. London.

- ^ See Primus, Beatrice (2004), "A featural analysis of the Modern Roman Alphabet" (PDF), Written Language and Literacy, 7 (2): 235–274, doi:10.1075/wll.7.2.06pri, archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-10, retrieved 2015-12-05

- ^ Archibald Hill (1967): The typology of Writing systems. In: William A. Austin (ed.), Papers in Linguistics in Honor of Leon Dostert. The Hague, 92–99.

- ^ John DeFrancis (1989): Visible speech. The diverse oneness of writing systems. Honolulu

- ^ Geoffrey Sampson (1986): Writing Systems. A Linguistic Approach. London

- ^ Alice Faber (1992): Phonemic segmentation as an epiphenomenon. Evidence from the history of alphabetic writing. In: Pamela Downing et al. (ed.): The Linguistics of Literacy. Amsterdam. 111–134.

- ^ Daniels & Bright 1996, p. 4

- ^ Cammarosano, Michele. "Cuneiform Writing Techniques". cuneiform.neocities.org. Retrieved 2018-07-18.

- ^ Cammarosano, Michele (2014). "The Cuneiform Stylus". Mesopotamia. XLIX: 53–90.

- ^ Threatte, Leslie (1980). The grammar of Attic inscriptions. W. de Gruyter. pp. 54–55. ISBN 3-11-007344-7.

- ^ "Berber". Ancient Scripts. Archived from the original on 2017-08-26. Retrieved 2017-10-09.

- ^ de Kovel, Carolien G. F.; Carrión-Castillo, Amaia; Francks, Clyde (2019-01-24). "A large-scale population study of early life factors influencing left-handedness". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 584. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9..584D. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-37423-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6345846. PMID 30679750.

- ^ Papadatou-Pastou, Marietta; Ntolka, Eleni; Schmitz, Judith; Martin, Maryanne; Munafò, Marcus R.; Ocklenburg, Sebastian; Paracchini, Silvia (2020-06-01). "Human handedness: A meta-analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 146 (6): 481–524. doi:10.1037/bul0000229. hdl:10023/19889. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 32237881. S2CID 214768754.

- ^ Why is Hebrew written from right to left? Israeli Box

- ^ "Why Do We Read English From Left To Right?". March 11, 2012.

Sources

- Cisse, Mamadou (2006). "Ecrits et écriture en Afrique de l'Ouest". Sudlangues (in French). 6. Dakar. ISSN 0851-7215. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- Coulmas, Florian (2002) [1996]. The Blackwell encyclopedia of writing systems (reprint ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19446-0.

- Coulmas, Florian (2003). Writing systems: an introduction to their linguistic analysis. Cambridge textbooks in linguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78217-3.

- Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William, eds. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-07993-0.

- DeFrancis, John (1990) [1986]. The Chinese language: fact and fantasy. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-824-81068-9.

- Haarmann, Harald (2004). Geschichte der Schrift [History of Writing] (in German) (2nd ed.). München: C. H. Beck. ISBN 3-406-47998-7.

- Hannas, William C. (1997). Asia's orthographic dilemma. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1842-5.

- Millard, A. R. (1986). "The Infancy of the Alphabet". World Archaeology. 17 (3): 390–398. doi:10.1080/00438243.1986.9979978.

- Nishiyama, Yutaka (2010). "The Mathematics of Direction in Writing" (PDF). International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics. 61 (3): 347–356.

- Rogers, Henry (2005). Writing systems: a linguistic approach. Blackwell textbooks in linguistics. Malden, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-23463-0.

- Sampson, Geoffrey (1985). Writing systems: a linguistic introduction. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-804-71254-5.

- Smalley, William A. (1964). Smalley, William A. (ed.). Orthography studies: articles on new writing systems. London: United Bible Society. OCLC 5522014.

External links

- The World's Writing Systems – All 294 known writing systems, each with a typographic reference glyph and Unicode status