Coffee

Coffee is a widely consumed beverage prepared from the roasted seeds—commonly called "beans"—of the coffee plant. Coffee was first consumed as early as the 9th century, when it appeared in the highlands of Ethiopia.[1] From Ethiopia, it spread to Egypt and Yemen, and by the 15th century had reached Persia, Turkey, and northern Africa. From the Muslim world, coffee spread to Italy, then to the rest of Europe and the Americas.[2] Today, coffee is one of the most popular beverages worldwide.[3]

The two most commonly grown species of the coffee plant are C. canephora and C. arabica, which are cultivated in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa. Coffee berries are picked, processed, and dried. The seeds are roasted at temperatures around 200°C (392°F), during which the sugars in the bean caramelize, the bean changes color, and flavor develops. The beans are roasted to a light, medium, or dark brown color, depending on the desired flavor.[4] The roasted beans are ground and brewed in order to create the beverage coffee.[5]

Coffee has played an important role in many societies throughout history. In Africa and Yemen, it was used in religious ceremonies. In the 17th century, it was banned in Ottoman Turkey.[2] In Europe, it was once associated with rebellious political activities. Today, trade in coffee has a large economic impact. Coffee is one of the world's most important primary commodities; in 2003, coffee was the world's sixth-largest legal agricultural export in value.[6] From 1998 to 2000, 6.7 million tons of coffee were produced annually, and it is predicted that by 2010 production will rise to 7 million tons annually.

The health effects of coffee are controversial, and many studies have examined the relationship between coffee consumption and certain medical conditions. Studies have suggested that the consumption of coffee lowers the risk of certain diseases but may have negative effects as well, especially when excessive.

Etymology

The English word coffee first came into use in the early- to mid-1600s, but early forms date back to the last decade of the 1500s. It comes from the Italian caffè. This, in turn, was borrowed from the Ottoman Turkish kahveh, borrowed from the Arabic qahwa.[7]

The origin of the Arabic qahwa (قهوة), is uncertain. It is either derived from the name of the Kaffa region in southern Ethiopia, where coffee was cultivated, or by a truncation of qahwat al-būnn, meaning "wine of the bean" in Arabic.[8]

History

The history of coffee can be traced to at least as early as the 9th century, when it appeared in the highlands of Ethiopia.[1] According to legend, shepherds were the first to observe the influence of the caffeine in coffee beans when, after their goats consumed some wild coffee berries in the pasture, the goats appeared to "dance" and have an increased level of energy.[9] From Ethiopia, coffee spread to Egypt and Yemen,[10] and by the fifteenth century had reached Persia, Turkey, and northern Africa.

In 1583, Leonhard Rauwolf, a German physician, after returning from a ten-year trip to the Near East, gave this description of coffee:[11][12]

A beverage as black as ink, useful against numerous illnesses, particularly those of the stomach. Its consumers take it in the morning, quite frankly, in a porcelain cup that is passed around and from which each one drinks a cupful. It is composed of water and the fruit from a bush called bunnu.

From the Muslim world, coffee spread to Italy. The thriving trade between Venice and the Muslims of North Africa, Egypt, and the Middle East brought many African goods, including coffee, to this port. Merchants introduced coffee to the wealthy in Venice, charging them heavily for it, and introducing it to Europe. Coffee became more widely accepted after it was deemed an acceptable Christian beverage by Pope Clement VIII in 1600, despite appeals to ban the "Muslim drink". The first European coffee house opened in Italy in 1645.[2] The Dutch were the first to import it on large scale, and they eventually smuggled seedlings into Europe in 1690, defying the Arab prohibition on the exportation of plants or unroasted seeds. The Dutch later grew the crop in Java and Ceylon.[13] Through the efforts of the British East India Company, coffee became popular in England as well. It was introduced in France in 1657, and in Austria and Poland following the 1683 Battle of Vienna, when coffee was captured from supplies of the defeated Turks.[14]

When coffee reached the Thirteen Colonies, it was initially not as successful as it had been in Europe. However, during the Revolutionary War, the demand for coffee increased so much that dealers had to hoard their scarce supplies and raise prices dramatically; this was partly due to the reduced availability of tea from British merchants.[15] After the War of 1812, during which Britain had temporarily cut off access to tea imports, the Americans' taste for coffee grew, and high demand during the American Civil War together with advances in brewing technology secured the position of coffee as an everyday commodity in the United States.[16]

Biology

The Coffea plant resides in a genus of ten species of flowering plants in the family Rubiaceae. The plant is an evergreen shrub or small tree which may reach 5 meters (16.40 ft) in height when unpruned. The leaves are dark green and glossy, usually 10–15 centimeters (3.9–1.9 in) long and 6 centimeters (2.4 in) broad. It produces clusters of white, fragrant flowers which open simultaneously. Its fruit is oval and about 1.5 centimeters (.6 in) long.[17] The fruits, known as berries, are green when immature but ripen to yellow, then crimson, becoming black upon drying. Two seeds are usually contained in each berry, but in 5–10% of berries,[18] only one is produced; these are known as peaberries.[19] Berries ripen in 7–9 months. The coffee plant is native to subtropical Africa and southern Asia.[20]

Cultivation

r:Coffea canephora

m:Coffea canephora and Coffea arabica.

a:Coffea arabica.

Coffee is usually propagated by seed. The traditional method of planting coffee is to put 20 seeds in each hole at the beginning of the rainy season; half are eliminated naturally. Coffee is often intercropped with food crops, such as corn, beans, or rice, during the first few years.[17]

There are two main cultivated species of the coffee plant, Coffea canephora and Coffea arabica. Arabica coffee (from C. arabica) is considered more suitable for drinking than robusta (from C. canephora), which, compared to arabica, tends to be bitter and have less flavor. For this reason, about three fourths of coffee cultivated worldwide is C. arabica.[20] However, C. canephora is less susceptible to disease than C. arabica and can be cultivated in environments where C. arabica will not thrive. Robusta coffee also contains about 40–50% more caffeine than arabica.[1] For this reason it is used as an inexpensive substitute for arabica in many commercial coffee blends. Good quality robustas are used in some espresso blends to provide a better foam head and to lower the ingredient cost.[21] Other species include Coffea liberica and Coffea esliaca, believed to be indigenous to Liberia and southern Sudan respectively.[1]

Most arabica coffee beans originate from either Latin America, East Africa/Arabia, or Asia/Pacific. Robusta coffee beans are grown in West and Central Africa, throughout Southeast Asia and to some extent in Brazil.[20] Beans from different countries or regions usually have distinctive characteristics such as flavor, aroma, body, and acidity.[22] These taste characteristics are dependent not only on the coffee's growing region, but also on genetic subspecies (varietal) and processing.[23]

Processing

Roasting

Coffee berries and their seeds undergo multi-step processing before they become the roasted coffee with which most Western consumers are familiar. First, coffee berries are picked, generally by hand. Then, the flesh of the berry is removed, usually by machine, and the seeds are dried and sorted. The seeds are then labeled green coffee beans.[12]

The next step in the process is the roasting of the green coffee. Coffee is usually sold in a roasted state, and all coffee is roasted before being consumed. Coffee can be sold roasted by the supplier or it can be home roasted.[12] The roasting process has a considerable degree of influence on the taste of the final product, creating the distinctive flavor of coffee from a bland bean, by changing the coffee bean both physically and chemically.

Physically, the bean decreases in weight as moisture is lost, but increases in volume, causing the bean to become less dense. When bean temperature reaches 200°C (392°F), the actual roasting begins. Different varieties and ages of beans differ in density and moisture content, causing them to roast at different rates. The density of the bean is important because it influences the strength of the coffee and requirements for packaging it.[5]

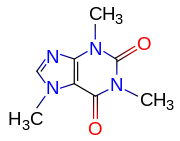

During roasting, caramelization occurs as the intense heat breaks down starches in the bean, changing them to to simple sugars which begin to brown, adding color to the bean.[12] Sucrose is lost rapidly during the roasting process; in darker roasts, it may disappear entirely. As the bean roasts, aromatic oils, acids and caffeine weaken, changing the flavor. When the internal temperature of the bean reaches 205°C (400°F), other oils will start to develop.[5] One of these oils is caffeol, created at about 200°C (392°F), which is largely responsible for coffee's aroma and flavor.[13]

Depending on the color of the roasted beans, they will be labeled as light, cinnamon, medium, high, city, full city, French or Italian roast.[24] Darker roasts are generally smoother, because they have less fiber content and a more sugary flavor. Lighter roasts have more caffeine, resulting in a slight bitterness, and a stronger flavor from aromatic oils and acids which are destroyed by longer roasting times.[25]

A small amount of chaff is produced during roasting from the skin left on the bean after processing.[4] Chaff is usually removed from the beans by air movement, though a small amount is added to dark roast coffees to soak up oils on the beans.[5]Decaffeination may also be part of the processing that coffee seeds undergo. Decaffeination is often done by processing companies, and the extracted caffeine is usually sold to the pharmaceutical industry.[13]

Preparation

Coffee beans must be ground and brewed in order to create a beverage. Grinding the roasted coffee beans is done at a roastery, in a grocery store, or in the home. They are most commonly ground at a roastery then packaged and sold to the consumer, though "whole-bean" coffee that is ground at home is becoming more popular. Coffee beans may be ground using a burr mill, an electric grinder which chops the beans, or, for certain types of coffee, by a mortar and pestle. The fineness of the grind is often identified by the usual brewing method for which it is appropriate. Turkish grind is the finest grind, while the coarsest grinds, such as coffee percolator or French press, are at the other extreme. The most common grinds are between the extremes: drip and paper filter grinds, which are used in most common home coffee brewing machines.[26]

Coffee may be brewed by several methods: by boiling, gravity, steeping, or pressure. Brewing coffee by boiling was the earliest method used, and Turkish coffee is an example of this method. It is prepared by powdering the beans with a mortar and pestle, then adding the powder to water and bringing it to a boil in a pot.[26]

Drip machines such as percolators or automatic coffeemakers brew coffee by gravity. In a drip machine, hot water seeps through ground coffee, absorbing its oils and essences, solely under gravity, then passes through the bottom of the filter. The used coffee grounds are retained in the filter with the liquid dripping into a carafe or pot. This is the most commonly used method for brewing coffee in North American and most European countries.[26] It may also be brewed by steeping, in a device such as a French press. In a French press, ground coffee and hot water are combined in a coffee press and left to brew for a few minutes. A plunger is then depressed to separate the coffee grounds at the bottom of the jug. This method leaves all of the coffee oils in the liquid, giving it a unique flavor. The espresso method uses more advanced technology to force very hot, pressurized water through the ground coffee, resulting in a stronger flavor and chemical changes that result in more coffee bean matter in the drink. Once brewed, coffee may be presented in a variety of ways: with no additives (colloquially known as black), with sugar, with milk or cream, hot or cold.[26]

A number of products are sold for the convenience of consumers who do not want to prepare their own coffee. Instant coffee is coffee dried into soluble powder or freeze-dried into granules, which can be quickly dissolved in hot water for consumption. Canned coffee is a beverage that has been popular in Asian countries for many years, particularly in Japan and South Korea, where vending machines typically sell a number of varieties of canned coffee, available both hot and cold. To match the often busy life of Korean city dwellers, companies mostly offer canned coffee in a wide variety of flavors. Japanese convenience stores and groceries also have a wide availability of plastic-bottled coffee drinks, which are typically lightly sweetened and pre-blended with milk.

Liquid coffee concentrates are sometimes used in large institutional situations where coffee needs to be produced for thousands of people at the same time. It is described as having a flavor about as good as low-grade robusta coffee, and costs about 10 cents a cup to produce. The machines used can process up to 500 cups an hour, or 1,000 if the water is preheated.[27]

Social aspects

- See also: Coffeehouse for a social history of coffee, and caffè for specifically Italian traditions.

In ancient times, coffee was initially used for spiritual reasons. At least 1,000 years ago, traders brought coffee across the Red Sea into Arabia (modern-day Yemen), where Muslim monks began cultivating the shrub in their gardens. At first, the Arabians made wine from the pulp of the fermented coffee berries. This beverage was known as Qishr (Kisher in modern usage) and was used during religious ceremonies. Coffee became the substitute beverage in spiritual practice in place of wine where wine was forbidden.[9]

Coffee drinking was briefly prohibited to Muslims as haraam in the early years of the 16th century, but this was quickly overturned. Use in religious rites among the Sufi branch of Islam led to coffee's being put on trial in Mecca, accused of being a heretic substance, much as wine was, and its production and consumption was briefly repressed. It was was later prohibited in Ottoman Turkey under an edict by the Sultan Murad IV .[28] Later, regarded as a Muslim drink, it was prohibited to Ethiopian Orthodox Christians until as late as 1900. Today, coffee is now considered a national drink of Ethiopia for people of all faiths. Its early association in Europe with rebellious political activities led to its banning in England, among other places.[29]

A contemporary example of coffee prohibition can be found in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a religion with about 12.5 million followers worldwide, which calls for complete coffee abstinence. The Church of Latter-Day Saints claims that it is both physically and spiritually unhealthy to consume coffee.[30] This comes from the Mormon doctrine of health, given in 1833 by Mormon founder Joseph Smith, in a revelation called the Word of Wisdom. It does not identify coffee by name, but includes the statement that "hot drinks are not for the belly", a statement which was later applied to coffee or tea.[30]

Health and pharmacology

Many scientific studies have examined the relationship between coffee consumption and a wide array of medical conditions. Most studies are contradictory as to whether coffee has any specific health benefits, and results are similarly conflicting with respect to negative effects of coffee consumption.[31] Studies have suggested that the consumption of coffee is beneficial to health in some ways. Coffee appears to reduce the risk of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, heart disease, diabetes mellitus type 2, cirrhosis of the liver,[32], and gout. Some health effects are due to the caffeine content of coffee, as the benefits are only observed in those who drink caffeinated coffee, while others appear to be due to other components.[33] Coffee contains antioxidants, which prevent free radicals from causing cell damage.[34]

Coffee has negative health effects associated with it, most of them due to its caffeine content. Research suggests that drinking caffeinated coffee can cause a temporary increase in the stiffening of arterial walls.[35] Excess coffee consumption may lead to a magnesium deficiency or hypomagnesemia.[36]

Caffeine content

The majority of all caffeine consumed worldwide comes from coffee—in some countries, this figure is as high as 85%.[37] Depending on the type of coffee and method of preparation, the caffeine content of a single serving can vary greatly. On average, the following amounts of caffeine can be expected in a single cup of coffee—about 207 milliliters (7 fluid ounces)—or single shot of espresso—about 44–59 mL (1.5–2 fl oz):[38][39][40]

- Drip coffee: 115–175 mg

- Espresso: 100 mg

- Brewed: 80–135 mg

- Instant: 65–100 mg

- Decaf, brewed: 3–4 mg

- Decaf, instant: 2–3 mg

Economics

Coffee is one of the world's most important primary commodities, as it is one of the world's most popular beverages. Coffee ingestion on average is about a third that of tap water in most of North America and Europe.[3] In total, 6.7 million metric tons of coffee were produced annually in 1998–2000, and the forecast is a rise to 7 million metric tons annually by 2010.[41]

Brazil remains the largest coffee exporting nation, but in recent years the green coffee market has been flooded by large quantities of robusta beans from Vietnam.[42] Robusta coffees, traded in London at much lower prices than New York's arabica, are preferred by large industrial clients, such as multinational roasters and instant coffee producers, because of the lower cost. Four single roaster companies buy more than 50% of all of the annual production: Kraft, Nestlé, Procter & Gamble, and Sara Lee.[43] The preference of the "Big Four" coffee companies for cheap robusta is believed by many to have been a major contributing factor to the crash in coffee prices,[44] and the demand for high-quality arabica beans is only slowly recovering. Many experts believe the giant influx of cheap green coffee after the collapse of the International Coffee Agreement of 1975–1989 led to the prolonged pricing crisis from 2001 to 2004.[45] In 1997 the price of coffee in New York broke US$3.00/lb, but by late 2001 it had fallen to US$0.43/lb.[46]

One issue of coffee cultivation is ecological. Originally, coffee farming was done in the shade of trees, which provided natural habitat for many animals and insects, roughly approximating the biodiversity of a natural forest.[47] Sun cultivation requires the clearing of trees and heavy fertilizer and pesticide use. Environmental problems such as deforestation, pesticide pollution, habitat destruction, and soil and water degradation are the side effects of these practices.[47] The American Birding Association has led a campaign for sustainably harvested, shade-grown and organic coffees vs. the newer mono-cropped full-sun varieties, which lead to deforestation and loss of bird habitat.[48]

The Dutch brand "Max Havelaar" started the concept of fair trade labeling, which guarantees coffee growers a negotiated pre-harvest price.[49] In 2004, 24,222 metric tons out of 7,050,000 produced worldwide were free trade; in 2005, 33,991 metric tons out of 6,685,000 were free trade, an increase from 0.34% to 0.51%.[50][51] A number of studies have shown that fair trade coffee has a positive impact on the communities which grow it. A study in 2002 found that fair trade strengthened producer organizations, improved returns to small producers, and positively affected their quality of life and the health of the organizations that represent.[52] A 2003 study concluded that fair trade has "greatly improved the well-being of small-scale coffee farmers and their families"[53] by providing access to credit and external development funding[54] and greater access to training, giving them the ability to improve the quality of their coffee.[55] The families of fair trade producers were also more stable than those who were not involved in fair trade, and their children had better access to education.[56] A 2005 study of Bolivian coffee producers concluded that Fairtrade certification has had a positive impact on local coffee prices, economically benefiting all coffee producers, Fairtrade certified or not. Fair trade also strengthened producer organizations and increased their political influence.[57]

References

- ^ a b c d Mekete Belachew, "Coffee," in von Uhlig, Siegbert, ed., Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (Weissbaden: Horrowitz, 2003), p.763.

- ^ a b c Meyers, Hannah (2005-03-07). ""Suave Molecules of Mocha" -- Coffee, Chemistry, and Civilization". Retrieved 2007-02-03.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Villanueva, Cristina M. (2006). "Total and specific fluid consumption as determinants of bladder cancer risk". International Journal of Cancer. 118 (8): 2040–2047. doi:10.1002/ijc.21587.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Coffee Roasting Operations". Bay Area Air Quality Management District. May 15, 1998. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- ^ a b c d Ball, Trent. "Coffee Roasting". Washington State University. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "FAOSTAT Agriculture Data". United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 2005-10-31.

- ^ "Coffee". Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- ^ "Coffee". The Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- ^ a b "History of Coffee". Jameson Coffee.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ John K. Francis. "Coffea arabica L. RUBIACEAE" (PDF). Factsheet of U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- ^ Léonard Rauwolf. Reise in die Morgenländer (in German).

- ^ a b c d Kummer, Corby. The Joy of Coffee: The Essential Guide to Buying, Brewing, and Enjoying, Houghton Mifflin, August 19, 2003. ISBN 978-0618302406.

- ^ a b c Dobelis, Inge N., Ed.: Magic and Medicine of Plants. Pleasantville: The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc., 1986. Pages 370-371.

- ^ Pendergrast, Mark (1999). Uncommon Grounds: The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-05467-6.

- ^ Columbia Encyclopedia. "Coffee". Columbia University Press. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ "Roasted Coffee (SIC 2095)". All Business.

- ^ a b James A. Duke. "Coffea arabica L." Purdue University. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ^ "Feature Article: Peaberry Coffee". Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ^ S. Hamon, M. Noirot, and F. Anthony, Developing a coffee core collection using the principal components score strategy with quantitative data (PDF), Core Collections of Plant Genetic Resources, 1995.

- ^ a b c "Botanical Aspects". International Coffee Organization. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ^ Reynolds, Richard. "Robusta's Rehab". Coffee Geek. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ Coffee: A Guide to Buying Brewing and Enjoying, 5th Edition, by Kenneth Davids

- ^ The Perfect Cup, by Timothy James Castle

- ^ a b Davids, Kenneth (1996). Home Coffee Roasting: Romance & Revival (excerpt). New York: St. Martin's Press. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- ^ Cipolla, Mauro. "Educational Primer: Degrees of Roast". Bellissimo Info Group. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ^ a b c d Rothstein, Scott. "Brewing Techniques". Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ^ Regarding liquid coffee concentrate: Wall Street Journal, March 21, 2005, page C4, Commodities Report

- ^ Hopkins, Kate (2006-03-24). "Food Stories: The Sultan's Coffee Prohibition". Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ^ Allen, Stewart. The Devil's Cup. Random House. ISBN 978-0345441492.

- ^ a b "Who Are the Mormons?". Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- ^ Kummer, Corby (2003). The Joy of Coffee, pp 160–165.

- ^ Klatsky, Arthur L. (12 June 2006). "Coffee, Cirrhosis, and Transaminase Enzymes". Archives of Internal Medicine. 166 (11): 1190–1195. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.11.1190.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pereira MA (2006). "Coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus". Arch Intern Med. 166 (12): 1311–1316. PMID 16801515.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bakalar, Nicholas (August 15, 2006). "Coffee as a Health Drink? Studies Find Some Benefits". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-07-28.

- ^ Mahmud, A. (2001). "Acute Effect of Caffeine on Arterial Stiffness and Aortic Pressure Waveform". Hypertension. 38 (2): 227–231. PMID 11509481.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The multifaceted and widespread pathology of magnesium deficiency

- ^ Drug Addiction & Advice Project, Facts About Caffeine, from the Addictions Research Foundation. Retrieved on May 16, 2007.

- ^ Coffee and Caffeine's Frequently Asked Questions from the alt.drugs.caffeine, alt.coffee, rec.food.drink.coffee Newsgroups, January 7, 1998

- ^ Bunker, M. L. (1979). "Caffeine content of common beverages". J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 74: 28–32.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mayo Clinic Staff. "Caffeine content of common beverages". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2007-07-22.

- ^ FAO (2003). "Coffee". Medium-term prospects for agricultural commodities. Projections to the year 2010. Retrieved 2006-10-16.

Global output is expected to reach 7.0 million metric tons (117 million bags) by 2010 compared to 6.7 million metric tons (111 million bags) in 1998–2000

- ^ Alex Scofield. "Vietnam: Silent Global Coffee Power". Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ^ Stein, Nicholas (9, 2002). "Crisis in a Coffee Cup". CNNMoney.com. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "CoffeeGeek - So You Say There's a Coffee Crisis". Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- ^ "Amsterdam coffee shop, Amsterdam coffee shop information". Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- ^ Cost Pass-Through in the U.S. Coffee Industry / ERR-38 (PDF), Economic Research Service, USDA.

- ^ a b Janzen, Daniel H. (Editor) (1983). Natural History of Costa Rica. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226393348.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Song Bird Coffee. Thanksgiving Coffee Company.

- ^ "Fair Trade Coffee". Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- ^ "Total Production of Exporting Countries". Retrieved 2007-07-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sales Volumes of Coffee". Retrieved 2007-07-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ Ronchi, L. (2002). The Impact of Fair Trade on Producers and their Organizations: A Case Study with Coocafe in Costa Rica. University of Sussex. p25-26.

- ^ Murray D., Raynolds L. & Taylor P. (2003). One Cup at a time: Poverty Alleviation and Fair Trade coffee in Latin America. Colorado State University, p28

- ^ Taylor, Pete Leigh (2002). Poverty Alleviation Through Participation in Fair Trade Coffee Networks, Colorado State University, p18.

- ^ Murray D., Raynolds L. & Taylor P. (2003). One Cup at a time: Poverty Alleviation and Fair Trade coffee in Latin America. Colorado State University, p8

- ^ Murray D., Raynolds L. & Taylor P. (2003). One Cup at a time: Poverty Alleviation and Fair Trade coffee in Latin America. Colorado State University, p10-11

- ^ Eberhart, N. (2005). Synthèse de l'étude d'impact du commerce équitable sur les organisations et familles paysannes et leurs territoires dans la filière café des Yungas de Bolivie. Agronomes et Vétérinaires sans frontières, p29.

External links

- Coffee and caffeine information

- Coffee & Conservation - Many resources on sustainable coffee, including reviews, especially shade coffee and biodiversity

- Coffee and caffeine health information - A collection of peer reviewed & journal published studies on coffee health benefits is evaluated, cited & summarized.

- Benjamin Joffe-Walt and Oliver Burkeman, The Guardian, 16 September 2005, "Coffee trail" - from Ethiopian village of Choche to London coffee shop

- Coffee on a Grande Scale - Article about the biology, chemistry, and physics of coffee production

- This is Coffee - Short tribute to coffee in the form of a documentary film (1961), made by "The Coffee Brewing Institute". The movie includes some do's and don'ts of making "the perfect cup of coffee" and an overview of different ways to enjoy coffee throughout the world.

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA