Chromatin

Chromatin is the complex of DNA and protein that makes up chromosomes. It is found inside the nuclei of eukaryotic cells, and within the nucleoid in prokaryotes.[1] The nucleic acids are in the form of double-stranded DNA (a double helix). The major proteins involved in chromatin are histone proteins, although many other chromosomal proteins have prominent roles too. The functions of chromatin are to package DNA into a smaller volume to fit in the cell, to strengthen the DNA to allow mitosis and meiosis, and to serve as a mechanism to control expression. Changes in chromatin structure are affected mainly by methylation (DNA and proteins) and acetylation (proteins). Chromatin structure is also relevant to DNA replication and DNA repair.

Chromatin is easily visualised by staining, hence its name, which literally means coloured material.

Basic Structure

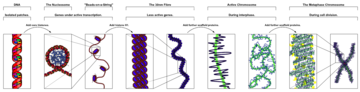

Simplistically, there are three levels of chromatin organization (Fig. 1):

- DNA wrapping around nucleosomes - The "beads on a string" structure.

- A 30 nm condensed chromatin fiber consisting of nucleosome arrays in their most compact form.

- Higher level DNA packaging into the metaphase chromosome.

These structures do not occur in all eukaryotic cells; there are examples of more extreme packaging, for example spermatozoa and avian red blood cells.

The different levels of chromatin compaction are clearly visible in cells. In non-dividing cells there are two types of chromatin: euchromatin and heterochromatin. These correspond to uncompacted actively transcribed DNA and compacted untranscribed DNA.

The structure of chromatin varies considerably as the cell progresses through the cell cycle. The changes in structure are required to allow the DNA to be used and managed, whilst minimising the risk of damage.

History

In 1882 Walther Flemming used the term chromatin for the first time. Flemming assumed that within the nucleus there was some kind of nuclear-scaffold. Furthermore, there were nucleoli, the nuclear plasm and the nuclear membranes. He wrote (transl. from German): “The scaffold owes its capability of refraction, the way how it behaves, and in particular its colorability to a substance which, with regard to its latter attribute, I have termed Chromatin. It is possible that this substance is really identical with the Nuclein-bodies. .... I’ll retain the name Chromatin as long as Chemistry has decided about it, and I empirically refer to it as that substance in the cell's nucleus which takes up the dye upon staining the nucleus ("Kerntinktionen").

Interphase chromatin

The structure of chromatin during interphase is optimised to allow easy access of transcription and DNA repair factors to the DNA while compacting the DNA into the nucleus. The structure varies depending on the access required to the DNA. Genes that require regular access by RNA polymerase require the looser structure provided by euchromatin.

Change in chromatin structure

Chromatin undergoes various forms of change in its structure. Histone proteins, the foundation blocks of chromatin, are modified by various post-translational modification to alter DNA packing. Acetylation results in the loosening of chromatin and lends itself to replication and transcription. When methylated they hold DNA together strongly and restrict access to various enzymes. A recent study showed that there is a bivalent structure present in the chromatin: methylated lysine residues at location 4 and 27 on histone 3. It is thought that this may be involved in development; there is more methylation of lysine 27 in embryonic cells than in differentiated cells, whereas lysine 4 methylation positively regulates transcription by recruiting nucleosome remodeling enzymes and histone acetylases.[2]

DNA structure

The vast majority of DNA within the cell is the normal DNA structure. However in nature DNA can form three structures, A-, B- and Z-DNA. A and B-DNA are very similar, forming right handed helices, while Z-DNA is a more unusual left handed helix with a zig-zag phosphate backbone. Z-DNA is thought to play a specific role in chromatin structure and transcription because of the properties of the junction between B- and Z-DNA.

At the junction of B- and Z-DNA one pair of bases is flipped out from normal bonding. These play a dual role of a site of recognition by many proteins and as a sink for torsional stress from RNA polymerase or nucleosome binding.

The nucleosome and "beads-on-a-string"

- Main articles: Nucleosome, Chromatosome and Histone

The basic repeat element of chromatin is the nucleosome, interconnected by sections of linker DNA, a far shorter arrangement than pure DNA in solution.

In addition to the core histones there is the linker histone, H1, which contacts the exit/entry of the DNA strand on the nucleosome. The nucleosome, together with histone H1, is known as a chromatosome. Chromatosomes, connected by about 20 to 60 base pairs of linker DNA, form an approximately 10nm "beads-on-a-string" fibre. (Fig. 1-2).

The nucleosomes bind DNA non-specifically, as required by their function in general DNA packaging. There is, however, some preference in the sequences the nucleosomes will bind. This is largely through the properties of DNA; adenosine and thymine are more favorably compressed into the inner minor grooves. This means nucleosomes bind preferentially at one position every 10 base pairs - where the DNA is rotated to maximise the number of A and T bases which will lie in the inner minor groove. (See mechanical properties of DNA.)

30 nm chromatin fibre

Left: 1 start helix "solenoid" structure.

Right: 2 start loose helix structure.

Note: the nucleosomes are omitted in this diagram - only the DNA is shown.

The "beads-on-a-string" structure in turn coils into a 30 nm diameter helical structure known as the 30nm fibre or filament. The precise structure of the chromatin fibre in the cell is not known in detail, and there is still some debate over this.

This level of chromatin structure is thought to be the form of euchromatin, which contains actively transcribed genes. EM studies have demonstrated the 30 nm fibre is highly dynamic such that it unfold into a 10 nm fiber ("beads-on-a-string") structure when transversed by an RNA polymerase engaged in transcription.

Linker DNA in yellow and nucleosomal DNA in pink.

The existing models commonly accept that the nucleosomes lie perpendicular to the axis of the fibre, with linker histones arranged internally. A stable 30 nm fibre relies on the regular positioning of nucleosomes along DNA. Linker DNA is relatively resistant to bending and rotation. This makes the length of linker DNA critical to the stability of the fibre, requiring nucleosomes to be separated by lengths that permit rotation and folding into the required orientation without excessive stress to the DNA. In this view, different length of the linker DNA should produce different folding topologies of the chromatin fiber. Recent theoretical work, based on electron-microscopy images[3] of reconstituted fibers support this view.[4]

Spatial organization of chromatin in the cell nucleus

The layout of the genome within the nucleus is not random - specific regions of the genome are always found in certain areas. Specific regions of the chromatin are thought to be bound to the nuclear membrane, while other regions are bound together by protein complexes. The layout of this is not, however, well characterised apart from the compaction of one of the two X chromosomes in mammalian females into the Barr body. This serves the role of permanently deactivating these genes, which prevents females getting a 'double dose' of relative to males.

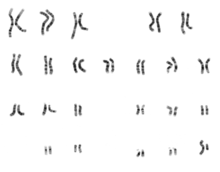

Metaphase chromatin

The metaphase structure of chromatin differs vastly to that of interphase. It is optimised for physical strength and manageability, forming the classic chromosome structure seen in karyotypes. The structure of the condensed chromosome is thought to be loops of 30nm fibre to a central scaffold of proteins. It is, however, not well characterised.

The physical strength of chromatin is vital for this stage of division to prevent shear damage to the DNA as the daughter chromosomes are separated. To maximise strength the composition of the chromatin changes as it approaches the centromere, primarily through alternative histone H1 anologues.

Non-histone chromosomal proteins

The proteins that are found associated with isolated chromatin fall into several functional categories:

- chromatin-bound enzymes

- high mobility group (HMG) proteins

- transcription factors

- scaffold proteins

- transition proteins (testis specific proteins)

- protamines (present in mature sperm)

Enzymes associated with chromatin are those involved in DNA transcription, replication and repair, and in post-translational modification of histones. They include various types of nucleases and proteases. Scaffold proteins encompass chromatin proteins such as insulators, domain boundary factors and cellular memory modules (CMMs).

Chromatin: alternative definitions

- Simple and concise definition: Chromatin is DNA plus the proteins (and RNA) that package DNA within the cell nucleus.

- A biochemists’ operational definition: Chromatin is the DNA/protein/RNA complex extracted from eukaryotic lysed interphase nuclei. Just which of the multitudinous substances present in a nucleus will constitute a part of the extracted material will depend in part on the technique each researcher uses. Furthermore, the composition and properties of chromatin vary from one cell type to the another, during development of a specific cell type, and at different stages in the cell cycle.

- The DNA – plus – histone – equals – chromatin definition: The DNA double helix in the cell nucleus is packaged by special proteins termed histones. The formed protein/DNA complex is called chromatin. The structural entity of chromatin is the nucleosome.

Nobel Prizes

The following scientists were recognized for their contributions to what we know about chromatin:

Albrecht Kossel (University of Heidelberg) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1910 "in recognition of the contributions to our knowledge of cell chemistry made through his work on proteins, including the nucleic substances"

Thomas Hunt Morgan (California Institute of Technology) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1933 "for his discoveries concerning the role played by the chromosome in heredity".

Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins (MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Harvard University, London University) were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1962 "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material".

Aaron Klug (MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1982 "for his development of crystallographic electron microscopy and his structural elucidation of biologically important nucleic acid-protein complexes".

Roger Kornberg (Stanford University) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2006 "for his studies of the molecular basis of eukaryotic transcription". In 1974 published the discovery that the nucleosome consists of a tetramer of histones H3 and H4 and two dimers of histones H2A and H2B.

See also

References

- ^

Dame, R.T. (2005). "The role of nucleoid-associated proteins in the organization and compaction of bacterial chromatin". Mol. Microbiol. 56 (4): 858–70. PMID 15853876.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

Bernstein, B.E., T.S. Mikkelsen, X. Xie, M. Kamal, D.J. Huebert, J. Cuff, B. Fry, A. Meissner, M. Wernig, K. Plath, R. Jaenisch, A. Wagschal, R. Feil, S.L. Schreiber & E.S. Lander (2006). "A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells". Cell. 125 (2): 315–26. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 16630819.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Robinson PJ, Fairall L, Huynh VA, Rhodes D. (2006). "EM measurements define the dimensions of the "30-nm" chromatin fiber: evidence for a compact, interdigitated structure". PNAS. 103 (17): 6506–11. PMID 16617109.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Wong H, Victor JM, Mozziconacci J. (2007). "An all-atom model of the chromatin fiber containing linker histones reveals a versatile structure tuned by the nucleosomal repeat length". PLoS ONE. 2 (9). PMID 17849006.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Corces, V. G. 1995. Chromatin insulators. Keeping enhancers under control. Nature 376:462-463.

- Cremer, T. 1985. Von der Zellenlehre zur Chromosomentheorie: Naturwissenschaftliche Erkenntnis und Theorienwechsel in der frühen Zell- und Vererbungsforschung, Veröffentlichungen aus der Forschungsstelle für Theoretische Pathologie der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. Springer-Vlg., Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Elgin, S. C. R. (ed.). 1995. Chromatin Structure and Gene Expression, vol. 9. IRL Press, Oxford, New York, Tokyo.

- Gerasimova, T. I., and V. G. Corces. 1996. Boundary and insulator elements in chromosomes. Current Op. Genet. and Dev. 6:185-192.

- Gerasimova, T. I., and V. G. Corces. 1998. Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins mediate the function of a chromatin insulator. Cell 92:511-521.

- Gerasimova, T. I., and V. G. Corces. 2001. CHROMATIN INSULATORS AND BOUNDARIES: Effects on Transcription and Nuclear Organization. Annu Rev Genet 35:193-208.

- Gerasimova, T. I., K. Byrd, and V. G. Corces. 2000. A chromatin insulator determines the nuclear localization of DNA [In Process Citation]. Mol Cell 6:1025-35.

- Ha, S. C., K. Lowenhaupt, A. Rich, Y. G. Kim, and K. K. Kim. 2005. Crystal structure of a junction between B-DNA and Z-DNA reveals two extruded bases. Nature 437:1183-6.

- Pollard, T., and W. Earnshaw. 2002. Cell Biology. Saunders.

- Saumweber, H. 1987. Arrangement of Chromosomes in Interphase Cell Nuclei, p. 223-234. In W. Hennig (ed.), Structure and Function of Eucaryotic Chromosomes, vol. 14. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Sinden, R. R. 2005. Molecular biology: DNA twists and flips. Nature 437:1097-8.

- Van Holde KE. 1989. Chromatin. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-96694-3.

- Van Holde, K., J. Zlatanova, G. Arents, and E. Moudrianakis. 1995. Elements of chromatin structure: histones, nucleosomes, and fibres, p. 1-26. In S. C. R. Elgin (ed.), Chromatin structure and gene expression. IRL Press at Oxford University Press, Oxford.