Jesus

Jesus of Nazareth | |

|---|---|

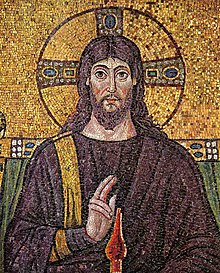

6th-century mosaic in Ravenna, Italy portrays Jesus dressed as a philosopher king in a cloak of Tyrian purple. He appears as the Pantocrator, enthroned as in the Book of Revelation, with the characteristic Christian cross inscribed in the halo behind his head. Though depictions of Jesus are culturally important, no undisputed record of Jesus' appearance is known to exist.[1] | |

| Born | 7–2 BC/BCE |

| Died | 26–36 AD/CE. (According to Christians, he rose three days later.) |

| Cause of death | Crucifixion |

| Resting place | Church of the Holy Sepulchre according to some Christians |

| Occupation(s) | Carpenter, itinerant preacher. God incarnate to most Christians; prophet of Islam. |

Jesus of Nazareth (7–2 BC/BCE to 26–36 AD/CE),[2][3] also known as Jesus Christ, is the central figure of Christianity, revered by most Christians as the incarnation of God, and is also an important figure in several other religions.

The name "Jesus" is an Anglicization of the Greek Ίησους (Iēsous), itself a Hellenization of the Hebrew יהושע (Yehoshua) or Hebrew-Aramaic ישוע (Yeshua), meaning "YHWH rescues". "Christ" is a title derived from the Greek Χριστός (Christós), meaning the "Anointed One," which corresponds to the Hebrew-derived "Messiah".[4]

The main sources of information regarding Jesus' life and teachings are the gospels. Most scholars in the fields of history and biblical studies agree that Jesus was a Galilean Jew, was regarded as a teacher and healer, was baptized by John the Baptist, and was crucified in Jerusalem on orders of Roman Governor Pontius Pilate, on the charge of sedition against the Roman Empire.[5][6] Most critical scholars believe that ancient texts on Jesus' life are at least partially accurate.[7][8]

Christian views of Jesus (see also Christology) center on the belief that Jesus is divine, is the Messiah whose coming was prophesied in the Old Testament, and that he was resurrected after his crucifixion. Christians predominantly believe that Jesus is the "Son of God" (meaning that he is God the Son, the second person in the Trinity), who came to provide salvation and reconciliation with God. Other Christian beliefs include Jesus' virgin birth, performance of miracles, ascension into Heaven, and future Second Coming. While the doctrine of the Trinity is widely accepted by Christians, a small minority instead hold various nontrinitarian beliefs concerning the divinity of Jesus.

In Islam, Jesus (Template:Lang-ar, commonly transliterated as Isa) is considered one of God's important prophets,[9][10] a bringer of scripture, a worker of miracles, and the Messiah. Muslims, however, believe Jesus was not divine and not crucified, but ascended bodily to heaven.

Chronology

Scholars do not know the exact year or date of Jesus' birth or death. The Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke place Jesus' birth under the reign of Herod the Great, who died in 4 BC/BCE,[11] although the Gospel of Luke also describes the birth as taking place during the first census of the Roman provinces of Syria and Iudaea in 6 AD/CE.[12] Scholars generally assume a date of birth between 6 and 4 BC/BCE.[13] Jesus' ministry followed that of John the Baptist.[14] The Gospels name Pontius Pilate as the Roman prefect that had Jesus crucified, and Pilate was prefect of Iudea between 26 and 36 AD/CE.[15]

The common Western standard for numbering years, in which the current year is 2024, is based on an early medieval attempt to count the years from Jesus' birth.

While Christmas, in honor of Jesus' birth, is celebrated December 25, there is no indication that this was his actual birthday. Jesus died after Passover, a Jewish holiday occurring in northern spring. Christians commemorate Jesus' death at this time of year, on Good Friday.

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

Life and teachings, as told in the Gospels

The Bible's four canonical gospels are the main sources for the traditional Christian biography of Jesus' life. Scholars, although considering the gospel accounts to be historically useful, differ widely as to their reliability. Each gospel portrays Jesus' life and its meaning differently.[16][17] To combine these four stories into one story is tantamount to creating a fifth story, one different from each original.[17] The gospel of John is not a biography of Jesus but a theological presentation of him as the divine Logos.[18]

Genealogy and family

Of the four gospels, only Matthew and Luke give accounts of Jesus' genealogy. The accounts in the two gospels are substantially different, and various theories have been proposed to explain the discrepancies.[19] Both accounts, however, trace his line back to King David and from there to Abraham. These lists are identical between Abraham and David, but they differ between David and Joseph. Matthew starts with Solomon and proceeds through the kings of Judah to the last king, Jeconiah. After Jeconiah, the line of kings terminated when Babylon conquered Judah. Thus, Matthew shows that Jesus is the legal heir to the throne of Israel. Luke's genealogy is longer than Matthew's; it goes back to Adam and provides more names between David and Jesus.

Joseph, husband of Mary, appears in descriptions of Jesus' childhood. No mention, however, is made of Joseph during the ministry of Jesus.

The New Testament books of Matthew, Mark, and Galatians tell of Jesus' relatives, including what may have been brothers and sisters.[20] The Greek word adelphos in these verses, often translated as brother, can refer to any familial relation, and most Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians translate the word as kinsman or cousin in this context (see Perpetual virginity of Mary). Luke also mentions that Elizabeth, mother of John the Baptist, was a "cousin" or "relative" of Mary (1:36 Luke 1:36), which would make John a distant cousin of Jesus.

Nativity and early life

According to Matthew and Luke, Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea to Mary, a virgin, by a miracle of the Holy Spirit. The Gospel of Luke gives an account of the angel Gabriel visiting Mary to tell her that she was chosen to bear the Son of God (1:26–38 Luke 1:26–38). According to Luke, an order of Caesar Augustus had forced Mary and Joseph to leave their homes in Nazareth and come to the home of Joseph's ancestors, the house of David, for the Census of Quirinius.

After Jesus' birth, the couple was forced to use a manger in place of a crib because of a shortage of accommodation (2:1–7 Luke 2:1–7). According to Luke, an angel announced Jesus' birth to shepherds who left their flocks to see the newborn child and who subsequently publicized what they had witnessed throughout the area (see The First Noël). Matthew tells of the "Wise Men" or "Magi" who brought gifts to the infant Jesus after following a star which they believed was a sign that the King of the Jews had been born (2:1–12 Matthew 2:1–12).

Jesus' childhood home is identified as the town of Nazareth in Galilee. Except for a journey to Egypt by his family in his infancy to escape Herod's Massacre of the Innocents and a short trip to Tyre and Sidon (in what is now Lebanon), the Gospels place all other events in Jesus' life in ancient Israel.[21] According to Matthew, the family remained in Egypt until Herod's death, whereupon they returned to Nazareth to avoid living under the authority of Herod's son and successor Archelaus (2:19–23 Matthew 2:19–23).

Only Luke tells that Jesus was found teaching in the temple by his parents after being lost. The Finding in the Temple (2:41–52 Luke 2:41–52) is the only event between Jesus' infancy and baptism mentioned in any of the canonical Gospels. According to Luke, Jesus was "about thirty years of age" when he was baptized (3:23 Luke 3:23). In Mark, Jesus is called a carpenter. Matthew says he was a carpenter's son, suggesting to some that Jesus may have spent some of his first 30 years practicing carpentry with his father (6:3 Mark 6:3, 13:55 Matthew 13:55).

Baptism and Temptation

All three synoptic Gospels describe the Baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist, an event which Biblical scholars describe as the beginning of Jesus' public ministry. According to these accounts, Jesus came to the Jordan River where John the Baptist had been preaching and baptizing people in the crowd. Matthew describes John as initially hesitant to comply with Jesus' request for John to baptize him, stating that it was Jesus who should baptize him. Jesus persisted, "It is proper for us to do this to fulfill all righteousness" (3:15 Matthew 3:15). After Jesus was baptized and rose from the water, Mark states Jesus "saw the heavens parting and the Spirit descending upon Him like a dove. Then a voice came from heaven saying: 'You are My beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased'" (1:10–11 Mark 1:10–11). The Gospel of John does not describe the baptism, but it does attest that Jesus is the very one about whom John the Baptist had been preaching — the Son of God.

Following his baptism, Jesus was led into the desert by God where he fasted for forty days and forty nights (4:1–2 Matthew 4:1–2). During this time, the devil appeared to him and tempted Jesus three times. Each time, Jesus refused temptation with a quotation of scripture from the Book of Deuteronomy. The devil departed and angels came and brought nourishment to Jesus (4:1–11 Matthew 4:1–11, 1:12–13 Mark 1:12–13, 4:1–13 Luke 4:1–13).

Ministry

The Gospels state that Jesus, as Messiah, came to "give his life as a ransom for many" and "preach the good news of the Kingdom of God."[22] Over the course of his ministry, Jesus is said to have performed various miracles, including healings, exorcisms, walking on water, turning water into wine, and raising several people, such as Lazarus, from the dead (11:1–44 John 11:1–44, 9:25 Matthew 9:25, and 7:15 Luke 7:15).

The Gospel of John describes three different passover feasts over the course of Jesus' ministry. This implies that Jesus preached for a period of at least "two years plus a month or two",[23] although some interpretations of the Synoptic Gospels suggest a span of only one year.[24] The focus of his ministry was toward his closest adherents, the Twelve Apostles, though many of his followers were considered disciples. The Twelve Apostles and others closest to Jesus were all Jews as shown by Jesus’ statements that his mission is directed only to those of the house of Israel (15:24 Matthew 15:24, 10:1-6 Matthew 10:1–6) and by the fact that only after the death of Jesus did the apostles agree with Paul that the teaching of the gospel could be extended to uncircumcised Gentiles (15:1–31 Acts 15:1–31, 2:7-9 Galatians 2:7–9, 10:1–11:18 Acts 10:1–11:19). Jesus led an apocalyptic following. He preached that the end of the current world would come unexpectedly, and that he would return to judge the world, especially according to how they treated the vulnerable; for this reason, he called on his followers to be ever alert and faithful. Jesus also taught that repentance was necessary to escape hell, and promised to give those who believe in him eternal life (3:16–18 John 3:16–18).

At the height of his ministry, Jesus attracted huge crowds numbering in the thousands, primarily in the areas of Galilee and Perea (in modern-day Israel and Jordan respectively).[25] Some of Jesus' most famous teachings come from the Sermon on the Mount, which contained the Beatitudes and the Lord's Prayer. Jesus often employed parables, such as the Parable of the Prodigal Son and the Parable of the Sower. His teachings encouraged unconditional self-sacrificing God-like love for God and for all people. During his sermons, he preached about service and humility, the forgiveness of sin, faith, turning the other cheek, love for one's enemies as well as friends, and the need to follow the spirit of the law in addition to the letter.[26]

Jesus often met with society's outcasts, such as the publicani (Imperial tax collectors who were despised for extorting money), including the apostle Matthew; when the Pharisees objected to Jesus' meeting with sinners rather than the righteous, Jesus replied that it was the sick who need a physician, not the healthy (9:9–13 Matthew 9:9–13). According to Luke and John, Jesus also made efforts to extend his ministry to the Samaritans, who followed a different form of the Israelite religion. This is reflected in his preaching to the Samaritans of Sychar, resulting in their conversion (4:1–42 John 4:1–42).

According to the synoptic gospels, Jesus led three of his apostles — Peter, John, and James — to the top of a mountain to pray. While there, he was transfigured before them, his face shining like the sun and his clothes brilliant white; Elijah and Moses appeared adjacent to him. A bright cloud overshadowed them, and a voice from the sky said, "This is my beloved son, with whom I am well pleased."[27] The gospels also state that toward the end of his ministry, Jesus began to warn his disciples of his future death and resurrection (16:21–28 Matthew 16:21–28).

Arrest, trial, and death

In the account given by the synoptic gospels, Jesus came with his followers to Jerusalem during the Passover festival where a large crowd came to meet him, shouting, "Hosanna! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Blessed is the King of Israel!"[28] Following his triumphal entry,[29] Jesus created a disturbance at Herod's Temple by overturning the tables of the moneychangers who set up shop there, and claiming that they had made the Temple a "den of robbers." (11:17 Mark 11:17). Later that week, Jesus celebrated the Passover meal with his disciples — an event subsequently known as the Last Supper — in which he prophesied that he would be betrayed by one of his disciples, and would then be executed. In this ritual he took bread and wine in hand, saying: "this is my body which is given for you" and "this cup which is poured out for you is the New Covenant in my blood," and instructed them to "do this in remembrance of me" (22:7–20 Luke 22:7–20). Following the supper, Jesus and his disciples went to pray in the Garden of Gethsemane.

While in the Garden, Jesus was arrested by temple guards on the orders of the Sanhedrin and the high priest, Caiaphas (22:47–52 Luke 22:47–52, 26:47–56 Matthew 26:47–56). The arrest took place clandestinely at night to avoid a riot, as Jesus was popular with the people at large (14:2 Mark 14:2). Judas Iscariot, one of his apostles, betrayed Jesus by identifying him to the guards with a kiss. Simon Peter, another one of Jesus' apostles, used a sword to attack one of Jesus' captors, cutting off his ear, which, according to Luke, Jesus immediately healed miraculously.[30] Jesus rebuked the apostle, stating "all they that take the sword shall perish by the sword" (26:52 Matthew 26:52). After his arrest, Jesus' apostles went into hiding.

During the Sanhedrin Trial of Jesus, the high priests and elders asked Jesus, "Are you the Son of God?" When he replied, "You are right in saying I am," they condemned Jesus for blasphemy (22:70–71 luke 22:70–71). The high priests then turned him over to the Roman procurator Pontius Pilate, based on an accusation of sedition for forbidding the payment of taxes Luke 23:1-2 and claiming to be King of the Jews.[31] When Jesus came before Pilate, Pilate asked him, "Are you the king of the Jews?" to which he replied, "It is as you say." According to the Gospels, Pilate personally felt that Jesus was not guilty of any crime against the Romans, and since there was a custom at Passover for the Roman governor to free a prisoner (a custom not recorded outside the Gospels), Pilate offered the crowd a choice between Jesus of Nazareth and an insurrectionist named Barabbas. The crowd chose to have Barabbas freed and Jesus crucified. Pilate washed his hands to indicate that he was innocent of the injustice of the decision (27:11–26 Matthew 27:11–26).

According to all four Gospels, Jesus died before late afternoon at Calvary, which was also called Golgotha. The wealthy Judean Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Sanhedrin according to Mark and Luke, received Pilate's permission to take possession of Jesus' body, placing it in a tomb.[32] According to John, Joseph was aided by Nicodemus, who joined him to help bury Jesus, and who appears in other parts of John's gospel (19:38–42 John 19:38–42). The three Synoptic Gospels tell of the darkening of the sky from twelve until three that afternoon; Matthew also mentions an earthquake (27:51 Matthew 27:51).

Resurrection and Ascension

According to the Gospels, Jesus rose from the dead on the third day after his crucifixion.[33] The Gospel of Matthew states that an angel appeared near the tomb of Jesus and announced his resurrection to Mary Magdelene and "another Mary" who had arrived to anoint the body (28:1–10 Matthew 28:1–10). According to Luke there were two angels (24:4 Luke 24:4), and according to Mark there was a youth dressed in white (16:5 Mark 16:5). The "longer ending" to Mark states that on the morning of his resurrection, Jesus first appeared to Mary Magdalene (16:9 Mark 16:9). John states that when Mary looked into the tomb, two angels asked her why she was crying; and as she turned round she initially failed to recognize Jesus until he spoke her name (20:11–18 john 20:11–18).

The Acts of the Apostles state that Jesus appeared to various people in various places over the next forty days. Hours after his resurrection, he appeared to two travelers on the road to Emmaus (24:13–35 Luke 24:13–35). To his assembled disciples he showed himself on the evening after his resurrection (20:19 John 20:19). Although his own ministry had been specifically to Jews, Jesus is said to have sent his apostles to the Gentiles with the Great Commission and ascended to heaven while a cloud concealed him from their sight. According to Acts, Paul of Tarsus had a vision of Jesus during his Road to Damascus experience. Jesus promised to come again to fulfill the remainder of Messianic prophecy.[34]

Fulfillment of prophecy

The Gospels present Jesus' birth, life, death, and resurrection as fulfillments of prophecies found in the Hebrew Bible. See, for example, the virgin birth, the flight into Egypt, Immanuel (Isaiah 7:14), and the suffering servant.[35]

Historical Jesus

Scholars have used the historical method to develop probable reconstructions of Jesus' life. Over the past two hundred years, the image of Jesus among historical scholars has come to be very different than the common image of Jesus that was based on the gospels.[36] Some scholars draw a distinction between Jesus as reconstructed through historical methods and Jesus as understood through a theological point of view, while other scholars hold that a theological Jesus represents a historical figure.[37] The main sources of information regarding Jesus' life and teachings are the gospels, especially the synoptic gospels: Mark, Matthew, and Luke. Biblical scholars and most historians accept the historical existence of Jesus and regard claims against his existence as "effectively refuted".[38]

The English title of Albert Schweitzer's 1906 book, "The Quest of the Historical Jesus," is a label for the post-Enlightenment effort to describe Jesus using critical historical methods.[39] Since the end of the 18th century, scholars have examined the gospels and tried to formulate historical biographies of Jesus. Contemporary efforts benefit from a better understanding of 1st-century Judaism, renewed Roman Catholic biblical scholarship, broad acceptance of critical historical methods, sociological insights, and literary analysis of Jesus' sayings.[39]

Constructing a historical Jesus

Historians analyze the gospels to try to discern the historical man on whom these stories are based. They compare what the gospels say to historical events relevant to the times and places where the gospels were written. They try to answer historical questions about Jesus, such as why he was crucified.

Most scholars agree the Gospel of Mark was written about the time of the destruction of the Jewish Temple by the Romans under Titus in the year 70, and that the other gospels were written between 70–100.[41] The historical outlook on Jesus relies on critical analysis of the Bible, especially the gospels. Many scholars have sought to reconstruct Jesus' life in terms of contemporaneous political, cultural, and religious currents in Israel, including differences between Galilee and Judea, and between different sects such the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes and Zealots,[42][43] and in terms of conflicts among Jews in the context of Roman occupation.

Peter Kirby's Historical Jesus Theories gives an overview of the conflicting answers that recent writers have given to these questions. The variety and contradictory character of these answers indicate that what follows here is not to be taken as representing a consensus among scholars.

Descriptions of historical Jesus

Historians generally describe Jesus as an healer who preached the restoration of God's kingdom.[44] Most historians agree he was baptized by John the Baptist, and was crucified by the Romans.

John the Baptist led a large apocalyptic movement. He demanded repentance and baptism. Jesus was baptized and later began his ministry. After John was executed, some of his followers apparently took Jesus as their new leader.[45]

Historians are nearly unanimous in accepting Jesus' baptism as a historical event.[46]

According to Robert Funk, Jesus taught in pithy parables and with striking images.[47] He likened the Kingdom of Heaven to small and lowly things, such as yeast or a mustard seed,[47] that have great effects. Historians often see Jesus' theological pronouncements in the gospels as coming from the Christian tradition but not from Jesus' himself.

Jesus placed a special emphasis on God as one's heavenly father.[47]

Names and titles

| Part of a series on |

|

The name Jesus is an anglicization of the Hebrew name that would have more closely been pronounced as spelled Yeshua.[citation needed]

Jesus probably lived in Galilee for most of his life and he probably spoke Aramaic and Hebrew.[48] The name "Jesus" is an English transliteration of the Latin (Iēsus) which in turn comes from the Greek name Iesous ( Ιησους). The name has also been translated into English as "Joshua".[49] Further examination of the Septuagint finds that the Greek, in turn, is a transliteration of the Hebrew/Aramaic Yeshua (ישוע) (Yeshua — he will save) a contraction of Hebrew name Yehoshua (יהושוע Yeho — Yahweh [is] shua` — deliverance/rescue, usually Romanized as Joshua). Scholars believe that one of these was likely the name that Jesus was known by during his lifetime by his peers.[50]

Christ (which is a title and not a part of his name) is an Anglicization of the Greek term for Messiah (χριστός, from the verb χρίω "to anoint"), and literally means "anointed one." Historians have debated what this title might have meant at the time Jesus lived; some historians have suggested that other titles applied to Jesus in the New Testament had meanings in the first century quite different from those meanings ascribed today.[51]

The titles "Divine", "Son of God", "God", "God from God", "Lord", "Redeemer", "Liberator", and "Saviour of the World" were each applied to the Roman emperors. John Dominic Crossan considers that the application of them to Jesus by the early Christians would have been regarded as denying them to the emperor(s). "They were taking the identity of the Roman emperor and giving it to a Jewish peasant. Either that was a peculiar joke and a very low lampoon, or it was what the Romans called majestas and we call high treason."[52]

The title Son of God has often been taken as a claim to divinity. Likewise, Jesus claimed the title "I AM" in 8:58 John 8:58 which designates God in the Hebrew Bible, especially in 3:14 Exodus 3:14.[53] Some New Testament scholars, however, argue that Jesus himself made no claims to being God.[54][55][56][57][58][59][60] Most Christians identified Jesus as divine from a very early period, although holding a variety of views as to what exactly this implied.[61]

Religious groups

Scholars refer to the religious background of the early 1st century to better reconstruct Jesus' life. Some scholars identify him with one or another group.

Pharisees were a powerful force in 1st-century Judaism. After the fall of the Temple, the Pharisee outlook was established in Rabbinic Judaism. Some scholars speculate that Jesus was himself a Pharisee.[62] In Jesus' day, the two main schools of thought among the Pharisees were the House of Hillel, which had been founded by the eminent Tanna, Hillel the Elder, and the House of Shammai. Jesus' assertion of hypocrisy may have been directed against the stricter members of the House of Shammai, although he also agreed with their teachings on divorce (10:1–12 Mark 10:1–12).[63] Jesus also commented on the House of Hillel's teachings (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 31a) concerning the greatest commandment (12:28–34 Mark 12:28–34) and the Golden Rule (7:12 Matthew 7:12).

The Sadducee sect was particularly powerful in Jerusalem. They accepted the written Law only, rejecting the traditional interpretations accepted by the Pharisees, such as belief in retribution in an afterlife, resurrection of the body, angels, and spirits. They appear to have opposed Jesus' ministry, perhaps because they feared trouble from the Roman power, and in any case because they opposed his doctrines. After the fall of Jerusalem, they disappeared from history.[64]

Essenes were apocalyptic ascetics, one of the three (or four) major Jewish schools of the time, though they were not mentioned in the New Testament.[65] Some scholars theorize that Jesus was an Essene, or close to them. Among these scholars is Pope Benedict XVI, who supposes in his book on Jesus that "it appears that not only John the Baptist, but possibly Jesus and his family as well, were close to the Qumran community."[66]

Still other scholars hypothesize that Jesus led a new apocalyptic sect, possibly related to John the Baptist,[67] who became early Christian after the Great Commission spread his teachings to the Gentiles.[68] This is distinct from an earlier commission Jesus gave to the twelve Apostles, limited to "the lost sheep of the house of Israel" and specifically excluding the Gentiles or Samaritans (10 Matthew 10).

The Gospels record that Jesus was a Nazarene, a term commonly taken to refer to his place of birth, but sometimes as a religious affiliation.[43]

The Zealots were a revolutionary party opposed to Roman rule, one of those parties that, according to Josephus inspired the fanatical stand in Jerusalem that led to its destruction in the year 70.[69] Luke identifies Simon, a disciple, as a "zealot," which might mean a member of the Zealot party (which would therefore have been already in existence in the lifetime of Jesus) or a zealous person.[69] The notion that Jesus himself was a Zealot does not do justice to the earliest Synoptic material describing him.[70]

Gospels as historical texts

The New Testament, especially the synoptic gospels, were written soon after Jesus' life, making them relevant to historical analysis.[71] Modern scholars use various methods for sorting out the historical Jesus who inspired the gospels from the Jesus of faith that the gospel authors wrote about.

After the original oral stories were written down in Greek, they were transcribed, and later translated into other languages. This is not unique to the Bible — other documents of antiquity have been scrutinized for gaps between the date of an event and the date it was written. Having been written, the New Testament sources encountered insignificant changes, according to scholars such as the late Sir Frederic Kenyon (1863 - 1952).[72]

Contemporary textual critic Bart D. Ehrman cites numerous places where the gospels, and other New Testament books, were apparently altered by Christian scribes.[73] The scribes, largely amateurs, worked to make the gospels more similar and to remove verses that could be taken to support unorthodox beliefs common in early Christianity.[73] For example, Luke portrays Jesus as implacable in the face of his crucifixion, contrary to Mark, which portrays him in agony. Ehrman considers that verses in Luke in which Jesus sweats blood to be a later interpolation, made to include agony in Luke's account.[73] The views of intellectuals who entirely reject Jesus' historicity are summarized in the chapter on Jesus in Will Durant's Caesar and Christ. It is based on a scarcity of eyewitness accounts, a lack of direct archaeological evidence, the failure of specific ancient works to mention Jesus, and similarities between early Christianity and contemporary mythology.[74]

One method used to estimate the factual accuracy of stories in the gospels is known as the "criterion of embarrassment," which holds that stories about events with embarrassing aspects (such as the denial of Jesus by Peter, or the fleeing of Jesus' followers after his arrest) would likely not have been included if those accounts were fictional.[75] Biblical scholars hold that the works describing Jesus were initially communicated by oral tradition, and were not committed to writing until several decades after Jesus' crucifixion. The earliest extant texts which refer to Jesus are Paul's letters, which are usually dated from the mid-1st century. Paul wrote that he only saw Jesus in visions, but that they were divine revelations and hence authoritative (1:11–12 Galatians 1:11–12). The earliest extant texts describing Jesus in any detail were the four Gospels.

Jesus as myth

A few scholars have questioned the existence of Jesus as an actual historical figure. Among the proponents of non-historicity have been Bruno Bauer in the 19th century. Non-historicity was somewhat influential in biblical studies during the early 20th century. (The views of scholars who entirely rejected Jesus' historicity then were summarized in the chapter on Jesus in Will Durant's Caesar and Christ (in 1944); they were based on a suggested lack of eyewitness, a lack of direct archaeological evidence, the failure of certain ancient works to mention Jesus, and similarities early Christianity shares with then-contemporary religion and mythology.[76])

Michael Grant stated (in 1977) that the view is derived from a lack of application of historical methods:

…if we apply to the New Testament, as we should, the same sort of criteria as we should apply to other ancient writings containing historical material, we can no more reject Jesus' existence than we can reject the existence of a mass of pagan personages whose reality as historical figures is never questioned. ... To sum up, modern critical methods fail to support the Christ myth theory. It has 'again and again been answered and annihilated by first rank scholars.' In recent years, 'no serious scholar has ventured to postulate the non historicity of Jesus' or at any rate very few, and they have not succeeded in disposing of the much stronger, indeed very abundant, evidence to the contrary.[77]

More recently, arguments for non-historicity have been discussed by scholars such as George Albert Wells and Robert M. Price. Additionally, The Jesus Puzzle and The Jesus Mysteries are examples of popular works promoting the non-history hypothesis. Nevertheless, non-historicity is still regarded as effectively refuted by almost all Biblical scholars and historians.[78][79][80]

Religious perspectives

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christian views

Though Christian views of Jesus vary, it is possible to describe a general majority Christian view by examining the similarities between specific Western Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and many Protestant doctrines found in their catechetical or confessional texts.[81] This view, given below as the Principal view, does not encompass all groups which describe themselves as Christian, with other views immediately following.

Majority view

Christians profess that Jesus is the Messiah (Greek: Christos; English: Christ) prophesied in the Old Testament,[82] who, through his life, death, and resurrection, restored humanity's communion with God in the blood of the New Covenant. His death on a cross is understood as the redemptive sacrifice: the source of humanity's salvation and the atonement for sin[83] which had entered human history through the sin of Adam.[84]

They profess Jesus to be the only Son of God, the Lord,[85] and the eternal Word (which is a translation of the Greek Logos),[86] who became man in the incarnation,[87] so that those who believe in him might have eternal life.[88] They further hold that he was born of the Virgin Mary by the power of the Holy Spirit in an event described as the miraculous virgin birth or Incarnation.[89] In his life Jesus proclaimed the "good news" (Middle English: gospel; Greek: euangelion) that the coming Kingdom of Heaven was at hand,[90] and established the Christian Church, which is the seed of the kingdom, into which Jesus calls the poor in spirit.[91] Jesus' actions at the Last Supper, where he instituted the Eucharist, are understood as central to communion with God and remembrance of Jesus' sacrifice.[92]

The satisfaction view of atonement for sin, first articulated by Anselm of Canterbury, is that humanity owes God a debt of honor. This debt creates essentially an imbalance in the moral universe; it could not be satisfied by God's simply ignoring it. In this view, the only possible way of repaying the debt was for a being of infinite greatness, acting as a man on behalf of men, to repay the debt of honor owed to God. Therefore, when Jesus died, he paid a debt to God, his father. Thomas Aquinas consider atonement and articulated that rather than seeing the debt as one of honor, he sees the debt as a moral injustice to be righted. Aquinas concludes that punishment is a morally good response to sin, "Christ bore a satisfactory punishment, not for His, but for our sins," and substitution for another's sin is entirely possible.[citation needed]

Christians also profess that Jesus suffered death by crucifixion,[93] and rose bodily from the dead in the definitive miracle that foreshadows the resurrection of humanity at the end of time,[94] when Christ will come again to judge the living and the dead,[95] resulting in either entrance into heaven or damnation.[96] The resurrection is perhaps the most controversial aspect of the life of Jesus. Christianity hinges on this point of Christology, both as a response to a particular history and as a confessional response.[97] Christians believe that Jesus’ resurrection brings reconciliation with God (II Corinthians 5:18), the destruction of death (I Corinthians 15:26), and forgiveness of sins for followers of Jesus.[citation needed]

In the beginning of the second century, the Roman official and writer, Pliny the Younger (63 - ca. 113), stated that Christians were "singing responsively a hymn to Christ as to god" (carmenque Christo quasi deo dicere secum invicem).[98] Between 325 and 681, Christians theologically articulated and refined their view of the nature of Jesus by a series of seven ecumenical councils (see Christology). These councils described Jesus as one of the three divine hypostases or persons of the Holy Trinity: the Son is defined as constituting, together with God the Father and the Holy Spirit, the single substance of the One God (see Communicatio idiomatum).[99] Furthermore, Jesus is defined to be one person with a fully human and a fully divine nature, a doctrine known as the Hypostatic union.[100] However, the Oriental Orthodoxy, the Assyrian Church of the East and the Church of the East & Abroad do not accept the hypostatic union.[citation needed]

The Gospels of Matthew and Luke suggest the virgin birth of Jesus. Barth speaks of the virgin birth as the divine sign “which accompanies and indicates the mystery of the incarnation of the Son.”[101] Donald MacLeod[102] gives several Christological implications of a virgin birth: it highlights salvation as a supernatural act of God rather than an act of human initiative, avoids adoptionism (which is virtually required if a normal birth), and reinforces the sinlessness of Christ, especially as it relates to Christ being outside the sin of Adam (original sin).

Jesus Christ, the Mediator of humankind, fulfills the three offices of Prophet, Priest, and King. Eusebius of the early church worked out this threefold classification, which John Calvin developed[103] and John Wesley discussed.[104]

Alternative views

Current religious groups that do not accept the doctrine of the Trinity include the The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), Jehovah's Witnesses and the Christadelphians.

Latter-day Saints (Mormons)

Latter-day Saints theology maintains that Heavenly Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Ghost are three separate and distinct beings, though all eternal and equally divine, who together constitute the Godhead. Though described as "one God"[105] each play different roles: the Holy Ghost is a spirit without a physical body, the Father and Son possess distinct and perfected bodies of flesh and bone as recorded in Luke 24:39.[106]

The Book of Mormon records that the resurrected Jesus visited and taught some of the inhabitants of the early Americas after he appeared to his apostles in Jerusalem.[107] Mormons also believe that an apostasy occurred after the death of Christ and his apostles. They believe that Christ and Heavenly Father appeared to Joseph Smith in 1820 as part of a series of heavenly visits to restore the fullness of the gospel of Jesus Christ. They believe Jesus (not the Father) is the same as Jehovah or Yahweh of the Old Testament. See Jesus in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Based on a claimed divine revelation of Smith, they state that Jesus was born on April 06.[108]

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses believe Jesus to be God's (or Jehovah's) son, rather than being God himself. Jehovah's Witnesses believe he was the same divine created being as Michael the Archangel,[109][110] and that God made him a perfect human by transferring his life to the womb of Mary.[111] During the time Jesus was on earth he was simply a man, not a god-man.[112] They also believe that he is "the word" of John 1:1. This is understood to mean that he is God's spokesman, likely the one speaking in God's name to Adam, and to the Israelites in the wilderness.[113] In line with this, they point out that the Bible presents him as the only way humans can approach God. They include words like 'in Jesus name' in every prayer.[114] They view the term "Son of God" as an indication of Jesus' importance to the creator and his status as God's "only-begotten (unique) Son,"[115] the "firstborn of all creation,"[116] the one "of whom, and through whom, and to whom, are all things."[117] They believe that Jesus died on a single-piece torture stake, not a cross.[118] They believe that he is currently ruling in heaven as king of God's heavenly Kingdom, and will soon extend his rule to earth for a reign of peace.[119] They also believe he is now immortal[120] and can never die again.[121]

Unity

The Unity Church considers Jesus the master teacher and "way show-er," citing Jesus' frequent calls to emulate him rather than worship him, and the ability of others to be like him, such as in John 10:34 and John 14:12. Jesus is not worshiped as God, but regarded as someone who had achieved a complete connection with God the Father.

Christadelphians

Christadelphians believe that Jesus is literally God's son, hence the Biblical title son of God,[122] not God the Son. They believe that Jesus was in God's plan right from the beginning of creation,[123] but that he came into existence at his birth.[124] Quoting Biblical passages such as 2:10-14 and 17-18 hebrews 2:10–14,17–18, they maintain that Jesus was fully human, and that Jesus' total humanity was vital in saving people from their sins. This, Christadelphians believe, would not have been possible had Jesus actually been God.[125] They believe that Jesus is now in heaven, at God's right hand, waiting to return to the Earth to establish God's kingdom here forever.[126]

Other alternative views

Others believe that the one God, who revealed himself in the Old Testament as Jehovah, came to earth, taking on the human form of Jesus Christ. They believe Jesus is Jehovah, is the Holy Spirit, and is the one Person who is God. Examples of such churches today are Oneness Pentecostals and the New Church.

Other early views

Various early Christian groups and theologians held differing views of Jesus. The Ebionites, an early Jewish Christian community, believed that Jesus was the last of the prophets and the Messiah. They believed that Jesus was the natural-born son of Mary and Joseph, and thus they rejected the Virgin Birth. The Ebionites were adoptionists, believing that Jesus was not divine, but became the son of God at his baptism. They rejected the Epistles of Paul, believing that Jesus kept the Mosaic Law perfectly and wanted his followers to do the same. However, they felt that Jesus' crucifixion was the ultimate sacrifice, and thus animal sacrifices were no longer necessary. Therefore, some Ebionites were vegetarian and considered both Jesus and John the Baptist to have been vegetarians.[127]

In Gnosticism, Jesus is said to have brought the secret knowledge (gnosis) of the spiritual world necessary for salvation.[128] Their secret teachings were paths to gnosis, and not gnosis itself. While some Gnostics were docetics, other Gnostics believed that Jesus was a human who became possessed by the spirit of Christ during his baptism.[129] Many Gnostics believed that Christ was an Aeon sent by a higher deity than the evil demiurge who created the material world. Some Gnostics believed that Christ had a syzygy named Sophia. The Gnostics tended to interpret the books that were included in the New Testament as allegory, and some Gnostics interpreted Jesus himself as an allegory. The Gnostics also used a number of other texts that did not become part of the New Testament canon.

Marcionites were 2nd century Gentile followers of the Christian theologian Marcion of Sinope. They believed that Jesus rejected the Jewish Scriptures, or at least the parts that were incompatible with his teachings.[130] Seeing a stark contrast between the vengeful God of the Old Testament and the loving God of Jesus, Marcionites, like some Gnostics, came to the conclusion that the Jewish God was the evil creator of the world and Jesus was the savior from the material world. They also believed Jesus was not human, but instead a completely divine spiritual being whose material body, and thus his crucifixion and death, were divine illusions.[131] Marcionism was declared a heresy by proto-orthodox Christianity.

Sabellius in the 3rd century taught that the Trinity represented not three persons but a single person in three "modes." Jerome reported that the Montanists of his day shared this view.

Islamic views

Islam holds Jesus (Template:Lang-ar `Īsā) to have been a messenger of God who had been sent to guide the Children of Israel (banī isrā'īl) with a new scripture, the Injīl (gospel).[132] According to the Qur'an, believed by Muslims to be God's final revelation, Jesus was born to Mary (Arabic: Maryam) as the result of virginal conception, a miraculous event which occurred by the decree of God (Arabic: Allah). To aid him in his quest, Jesus was given the ability to perform miracles. These included speaking from the cradle, curing the blind and the lepers, as well as raising the dead; all by the permission of God. Furthermore, Jesus was helped by a band of disciples (the ḥawāriyūn). Islam states that Jesus was not killed nor crucified by the Jews, but that he had been raised alive up to heaven. Islamic traditions narrate that he will return to earth near the day of judgement to restore justice and defeat al-Masīḥ ad-Dajjāl (lit. "the false messiah", also known as the Antichrist) and the enemies of Islam. As a just ruler, Jesus will then die.[133]

Like all prophets in Islam, Jesus is considered to have been a Muslim, as he preached for people to adopt the straight path in submission to God's will. Islam rejects that Jesus was God or the son of God, stating that he was an ordinary man who, like other prophets, had been divinely chosen to spread God's message. Islamic texts forbid the association of partners with God (shirk), emphasizing the notion of God's divine oneness (tawhīd). As such, Jesus is referred to in the Qur'an frequently as the "son of Mary" ("Ibn Maryam").[133][134] Numerous titles are given to Jesus in the Qur'an, such as mubārak (blessed) and `abd-Allāh (servant of God). Another title is al-Masīḥ ("the messiah; the anointed one" i.e. by means of blessings), although it does not correspond with the meaning accrued in Christian belief. Jesus is seen in Islam as a precursor to Muhammad, and is believed by Muslims to have foretold the latter's coming.[133]

Ahmadiyya views

The Ahmadiyya Movement, was founded in 19th century India. Ahmadis interpret the Bible to show that Jesus was taken down from the cross while unconscious, not dead.[135] They believe that he revived, appeared to his disciples in the flesh, and fled eastward to Kashmir, where he died of old age under the name Yuz Asaf ("Leader of the Healed"). They believe his tomb is located in Srinagar, Kashmir. This view has also been taken up by some western authors and historians.[136]

Ahmadis believe that the prophecy concerning Jesus' second coming indicated a spiritual return, and that it was fulfilled in the person of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, identified as the Imam Mahdi (Promised Messiah).

Judaism's view

Mainstream Judaism holds the idea of Jesus being God, or part of a Trinity, or a mediator to God, to be heresy.[137] Judaism also holds that Jesus is not the Messiah, arguing that he had not fulfilled the Messianic prophecies in the Tanakh nor embodied the personal qualifications of the Messiah.[138] According to Jewish tradition, there were no more prophets after Malachi, who lived centuries before Jesus and delivered his prophesies about 420 BC/BCE. Judaism states that Jesus did not fulfill the requirements set by the Torah to prove that he was a prophet. Even if Jesus had produced such a sign that Judaism recognized, Judaism states that no prophet or dreamer can contradict the laws already stated in the Torah, which Judaism states Jesus did.[139][140]

The Mishneh Torah (an authoritative work of Jewish law) states in Hilkhot Melakhim 11:10–12 that Jesus is a "stumbling block" who makes "the majority of the world err to serve a divinity besides God".[141] According to Conservative Judaism, Jews who believe Jesus is the Messiah have "crossed the line out of the Jewish community".[142] Reform Judaism, the modern progressive movement, states "For us in the Jewish community anyone who claims that Jesus is their savior is no longer a Jew and is an apostate."[143]

Buddhist views

Buddhists' views of Jesus differ, since Jesus is not mentioned in any Buddhist text as Buddha preceded him by approximately 500 years. Some Buddhists, including Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama[144] regard Jesus as a bodhisattva who dedicated his life to the welfare of human beings.

Hindu views

Hindu beliefs about Jesus vary. Contemporary Sant Mat movements regard Jesus as a Satguru. Ramakrishna believed that Jesus was an Incarnation of God.[145] Swami Vivekananda has praised Jesus and cited him as a source of strength and the epitome of perfection.[146] Paramahansa Yogananda taught that Jesus was the reincarnation of Elisha and a student of John the Baptist, the reincarnation of Elijah.[147] Mahatma Gandhi considered Jesus one of his main teachers and inspirations for nonviolent resistance, saying "I like your Christ, I do not like your Christians. Your Christians are so unlike your Christ."[148]

Bahá'í views

The Bahá'í Faith, founded in 19th-century Persia, considers Jesus, along with Muhammad, the Buddha, Krishna, and Zoroaster, and other messengers of the great religions of the world to be Manifestations of God (or prophets), with both human and divine stations.[149] In their divine station Bahá'ís view them in essential unity with each other and with God, and in their human station they view them as distinct individuals.[149] Thus, in the Bahá'í view, Jesus incarnates God's attributes, perfectly reflecting and expressing them.[149] However, the Bahá'í view rejects the belief that the essence of God was perfectly or completely contained in Jesus or any other human body, since Bahá'í scripture emphasizes the transcendence of the essence of God.[149] Jesus is believed to be the "Son of God" though not literally a biological son. The title "Son of God" in the Bahá'í view is seen as entirely spiritual and shows the close relationship between him and God.[150]

Bahá'ís accept Jesus as the Messiah foretold in the Jewish Scriptures.

Mandaean views

Mandaeanism, a very small Mideastern, Gnostic sect that reveres John the Baptist as God's greatest prophet, regards Jesus as a false prophet of the false Jewish god of the Old Testament, Adonai,[151] and likewise rejects Abraham, Moses, and Muhammad.

Other views

The New Age movement entertains a wide variety of views on Jesus. Some New Age practitioners (such as the creators of A Course In Miracles) claim to go so far as to trance-channel his spirit. However, the New Age movement generally teaches that Christhood is something that all may attain. Theosophists, from whom many New Age teachings originated (a Theosophist named Alice A. Bailey invented the term New Age), refer to Jesus of Nazareth as the Master Jesus and believe he had previous incarnations and is presently one of the Masters of the Ancient Wisdom (deities responsible for governing the planet Earth).

Many writers emphasize Jesus' moral teachings. Garry Wills argues that Jesus' ethics are distinct from those usually taught by Christianity.[152] The Jesus Seminar portrays Jesus as an itinerant preacher who taught peace and love, rights for women and respect for children, and who spoke out against the hypocrisy of religious leaders and the rich.[153] Thomas Jefferson, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and a deist, created the Jefferson Bible entitled "The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth" that included only Jesus' ethical teachings because he did not believe in Jesus' divinity or any of the other supernatural aspects of the Bible.

Philosopher and atheist Bertrand Russell saw Jesus' teachings and values as surpassed by other philosophers; Russell writes 'I cannot myself feel that either in the matter of wisdom or in the matter of virtue Christ stands quite as high as some other people known to History. I think I should put Buddha and Socrates above Him in those respects.'[154] Friedrich Nietzsche saw Socrates and Jesus as foundational to Western culture and criticized them both. He considered Jesus' concern for the weak to be a reversal of noble morality and accused Christianity of spreading the concept of equal rights for all, which he opposed.[155]

Legacy

According to most Christian interpretations of the Bible, the theme of Jesus' teachings was that of repentance, unconditional love,[156] forgiveness of sin, grace, and the coming of the Kingdom of God.[157] Starting as a small Jewish sect,[158] it developed into a religion clearly distinct from Judaism several decades after Jesus death. Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire under a version known as Nicene Christianity and became the state religion under Theodosius I. Over the centuries, it spread to most of Europe, and around the world.

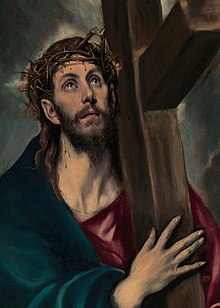

Jesus has been drawn, painted, sculpted and portrayed on stage and in films in many different ways, both serious and humorous. The figure of Jesus features prominently in art and literature. A number of popular novels, such as The Da Vinci Code, have also portrayed various ideas about Jesus, and a number of films, such as The Passion of the Christ, have portrayed his life, death, and resurrection. Many of the sayings attributed to Jesus have become part of the culture of Western civilization. There are many items purported to be relics of Jesus, of which the most famous are the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo.

Other legacies include a view of God as more lovingly parental, merciful, and more forgiving, and the growth of a belief in a blissful afterlife and in the resurrection of the dead. His teaching promoted the value of those who had commonly been regarded as inferior: women, the poor, ethnic outsiders, children, prostitutes, the sick, prisoners, etc. For over a thousand years, countless hospitals, orphanages, and schools have been founded explicitly in Jesus' name. Jesus and his message have been interpreted, explained and understood by many people. Jesus has been explained notably by Paul of Tarsus, the Church Fathers, including Augustine of Hippo, Martin Luther, and more recently by C. S. Lewis and Pope John Paul II. Thomas Jefferson considered Jesus' teaching to be "the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man."[159]

For some Jews, the legacy of Jesus has been a history of Christian antisemitism,[160] although in the wake of the Holocaust many Christian groups have gone to considerable lengths to reconcile with Jews and to promote interfaith dialog and mutual respect. For others, Christianity has often been linked to European colonialism.[161] Conversely, some have argued that through Bartolomé de las Casas' defense of the indigenous inhabitants of Spain's New World empire, one of the legacies of Jesus has been the notion of universal human rights.

See also

|

|

Notes

- ^ Bouteneff, Peter C. (2006). Sweeter Than Honey: Orthodox Thinking on Dogma and Truth. Crestwood: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. pp. p. 191. ISBN 0-88141-307-0.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Some of the historians and Biblical scholars who place the birth and death of Jesus within this range include D. A. Carson, Douglas J. Moo and Leon Morris. An Introduction to the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1992, 54, 56

- ^ Michael Grant, Jesus: An Historian's Review of the Gospels, Scribner's, 1977, p. 71; John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew, Doubleday, 1991–, vol. 1:214; E. P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus, Penguin Books, 1993, pp. 10–11, and Ben Witherington III, "Primary Sources," Christian History 17 (1998) No. 3:12–20.

- ^ per The Catholic Encyclopedia [1]

- ^ Raymond E. Brown, The Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave (New York: Doubleday, Anchor Bible Reference Library 1994), p. 964; D. A. Carson, et al., p. 50–56; Shaye J.D. Cohen, From the Maccabees to the Mishnah, Westminster Press, 1987, p. 78, 93, 105, 108; John Dominic Crossan, The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant, HarperCollins, 1991, p. xi – xiii; Michael Grant, p. 34–35, 78, 166, 200; Paula Fredriksen, Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews, Alfred B. Knopf, 1999, p. 6–7, 105–110, 232–234, 266; John P. Meier, vol. 1:68, 146, 199, 278, 386, 2:726; E.P. Sanders, pp. 12–13; Geza Vermes, Jesus the Jew (Philadelphia: Fortress Press 1973), p. 37.; Paul L. Maier, In the Fullness of Time, Kregel, 1991, pp. 1, 99, 121, 171; N. T. Wright, The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions, HarperCollins, 1998, pp. 32, 83, 100–102, 222; Ben Witherington III, pp. 12–20.

- ^ Though many historians may have certain reservations about the use of the Gospels for writing history, "even the most hesitant, however, will concede that we are probably on safe historical footing" concerning certain basic facts about the life of Jesus; Jo Ann H. Moran Cruz and Richard Gerberding, Medieval Worlds: An Introduction to European History Houghton Mifflin Company 2004, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Strobel, Lee. The Case for Christ: A Journalist's Personal Investigation of the Evidence for Jesus. Zondervan, 1998. ISBN 0310209307; Wright, N.T. The Challenge of Jesus: Rediscovering Who Jesus Was and Is. InterVarsity Press, 1999. ISBN 0830822003; Dunn, James D.G. The Evidence for Jesus." Westminster John Knox Press, 1985. ISBN 0664246982

- ^ Examples of authors who argue the Jesus myth hypothesis: Thomas L. Thompson The Messiah Myth: The Near Eastern Roots of Jesus and David (Jonathan Cape, Publisher, 2006); Michael Martin, The Case Against Christianity (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991), 36–72; John Mackinnon Robertson

- ^ James Leslie Houlden, "Jesus: The Complete Guide", Continuum International Publishing Group, 2005, ISBN 082648011X

- ^ Prof. Dr. Şaban Ali Düzgün, "Uncovering Islam: Questions and Answers about Islamic Beliefs and Teachings", Ankara: The Presidency of Religious Affairs Publishing, 2004

- ^ Edwin D. Freed, Stories of Jesus' Birth, (Continuum International, 2004), page 119.

- ^ Geza Vermes, The Nativity: History and Legend, London, Penguin, 2006, page 22.

- ^ James D. G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered, Eerdmans Publishing (2003), page 324.

- ^ Luke states that John's ministry began in the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar, when Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea, and Herod was tetrarch of Galilee, and his brother Philip was tetrarch of the region of Iturea and Trachonitis, and Lysanias was tetrarch of Abilene, during the high priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas.

- ^ Joel B. Green, The Gospel of Luke, (Eerdmans, 1997), page 168.

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ^ a b Ehrman, Bart D.. Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins, 2005. ISBN 978-0-06-073817-4

- ^ Durant, Will. Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1972

- ^ Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Gospel According to Luke I-IX. Anchor Bible. Garden City: Doubleday, 1981, pp. 499–500; I. Howard Marshall, The Gospel of Luke (The New International Greek Testament Commentary). Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1978, p. 158;

- ^ 13:55–56 Matthew 13:55–56, 6:3 Mark 6:3, and 1:19 Galatians 1:19

- ^ For Egypt: 2:13–23 Matthew 2:13–23; For Tyre and sometimes Sidon:15:21–28 Matthew 15:21–28 and 7:24–3 Mark 7:24–30

- ^ 10:45 Mark 10:45, 4:43 Luke 4:43, 20:31 John 20:31.

- ^ Meier 1991 vol. 1:405

- ^ "The Thompson Chain-Reference Study Bible NIV," published December 1999, B.B. Kirkbride Bible Co., Inc.; William Adler & Paul Tuffin, "The Chronography of George Synkellos: A Byzantine Chronicle of Universal History from the Creation," Oxford University Press (2002), p. 466

- ^ In John, Jesus' ministry takes place in and around Jerusalem.

- ^ Sermon on the Mount: 5–7 Matthew 5–7; Prodigal Son: 15:11–32 Luke 15:11–32; Parable of the Sower: 13:1–9 Matthew 13:1–9; Agape: 22:34–40 Matthew 22:34–40.

- ^ 17:1–6 Matthew 17:1–6, 9:1–8 Mark 9:1–8, 9:28–36 Luke 9:28–36

- ^ The crowd was quoting 118:26 Psalms 118:26; found in 12:13–16 John 12:13–16.

- ^ John puts the cleansing of the temple at the start of Jesus' ministry.

- ^ The apostle is identified as Simon Peter in 18:10 john 18:10; the healing of the ear is found in 22:51 luke 22:51.

- ^ 27:11 Matthew 27:11; 15:12 Mark 15:2.

- ^ 15:42–46 Mark 15:42–46; 23:50–56 Luke 23:50–56.

- ^ Matthew 28:5-10; 16:9 mark 16:9; 24:12–16 luke 24:12–16; 20:10–17 John 20:10–17; 2:24 Acts 2:24; 6:14 1Cor 6:14

- ^ Ministering to Israel: 15:24 Matthew 15:24; ascension: 16:19 Mark 16:19; 24:51 Luke 24:511:6–11. Acts 1:6–11; Paul's conversion on the road to Damascus: 9:1–19. Acts 9:1–19, 22:1–22; 26:9–24; Second coming: 24:36–44 Matthew 24:36–44

- ^ ""What the Old Testament Prophesied About the Messiah"". Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Borg, Marcus J. in Borg, Marcus J. and N. T. Wright. The Meaning of Jesus: Two visions. New York: HarperCollins. 2007.

- ^ See, for an example of the latter, Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth. Doubleday, 2007. ISBN 978-0-385-52341-7

- ^ "The nonhistoricity thesis has always been controversial, and it has consistently failed to convince scholars of many disciplines and religious creeds. ... Biblical scholars and classical historians now regard it as effectively refuted." - Van Voorst, Robert E. Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000), p. 16.

- ^ a b Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 - article "Historical Jesus, Quest of the"

- ^ Faces of Jesus

- ^ Meier (1991), pp.43–4

- ^ For a comparison of the Jesus movement to the Zealots, see S. G. F. Brandon, Jesus and the Zealots: a study of the political factor in primitive Christianity, Manchester University Press (1967) ISBN 0–684–31010–4

- ^ a b For a general comparison of Jesus' teachings to other schools of first century Judaism, see John P. Meier, Companions and Competitors (A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Volume 3) Anchor Bible, 2001. ISBN 0–385–46993–4. Cite error: The named reference "comparison" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Shaye J.D. Cohen, From the Maccabees to the Mishnah, Westminster Press, 1987, p. 78, 93, 105, 108; John Dominic Crossan, The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant, HarperCollins, 1991, p. xi – xiii; Michael Grant, p. 34–35, 78, 166, 200; Paula Fredriksen, Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews, Alfred B. Knopf, 1999, p. 6–7, 105–110, 232–234, 266; John P. Meier, vol. 1:68, 146, 199, 278, 386, 2:726; E.P. Sanders, pp. 12–13; Geza Vermes, Jesus the Jew (Philadelphia: Fortress Press 1973), p. 37.;

- ^ Sanders, E.P. Jesus and Judaism. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1987; Vermes, Geza. Jesus the Jew: A Historian's Reading of the Gospels. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1981; Fredriksen, Paula. From Jesus to Christ. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

- ^ Sanders, E.P. Jesus and Judaism. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1987; Vermes, Geza. Jesus the Jew: A Historian's Reading of the Gospels. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1981; Fredriksen, Paula. From Jesus to Christ. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

- ^ a b c Funk, Robert W., Roy W. Hoover, and the Jesus Seminar. The five gospels. HarperSanFrancisco. 1993. Cite error: The named reference "5G" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Brian Knowles: Which Language Did Jesus Speak – Aramaic or Hebrew?".

- ^ "Origin of the Name of Jesus Christ". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ^ Durant, Will. Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1944. p. 558; John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew. New York: Doubleday, 1991 vol. 1:205–7;

- ^ Vermes, "Jesus the Jew: A Historian's Reading of the Gospels"

- ^ Crossan, John Dominic, God and Empire, 2007, p. 28

- ^ "Jesus was claiming for himself the title "I AM" by which God designates himself... he was claiming to be God." - Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology, page 546, Zondervan.

- ^ "A further point of broad agreement among New Testament scholars is ... that the historical Jesus did not make the claim to deity that later Christian thought was to make for him: he did not understand himself to be God, or God the Son, incarnate. " - John Hick, The Metaphor of God Incarnate: Christology in a Pluralistic Age, Westminster John Knox Press, page 27.

- ^ Michael Ramsey, Jesus and the Living Past (Oxford University Press, 1980), page 39: 'Jesus did not claim deity for himself’

- ^ C. F. D. Moule, The Origin of Christology : 'Any case for a "high" Christology that depended on the authenticity of the alleged claims of Jesus about himself, especially in the Fourth Gospel, would indeed be precarious'

- ^ James Dunn (theologian), Christology in the Making, (SCM Press 1980), page 254: 'We cannot claim that Jesus believed himself to be the incarnate Son of God' and 'There is no question in my mind that the doctrine of incarnation comes to clear expression within the NT…John 1.14 ranks as a classic formulation of the Christian belief in Jesus as incarnate God.' Page xiii. .

- ^ Brian Hebblethwaite, The Incarnation (Cambridge University Press, 1987), page 74: 'it is no longer possible to defend the divinity of Jesus by reference to the claims of Jesus' .

- ^ John A. T. Robinson, Honest to God, Westminster Press (1963), Page 47: 'It is, indeed, an open question whether Jesus ever claimed to be the Son of God, let alone God.'

- ^ Larry Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity, page 5, describes the view that Jesus made 'both his messiahship and his divinity clear to his disciples during his ministry' as 'naive and ahistorical'.

- ^ Larry Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity, (Eerdmans, 2005), page 650.

- ^ Based on a comparison of the Gospels with the Talmud and other Jewish literature. Maccoby, Hyam Jesus the Pharisee, Scm Press, 2003. ISBN 0–334–02914–7; Falk, Harvey Jesus the Pharisee: A New Look at the Jewishness of Jesus, Wipf & Stock Publishers (2003). ISBN 1–59244–313–3.

- ^ Neusner, Jacob A Rabbi Talks With Jesus, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2000. ISBN 0–7735–2046–5. Rabbi Neusner contends that Jesus' teachings were closer to the House of Shammai than the House of Hillel.

- ^ "Sadducees." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ Based on a comparison of the Gospels with the Dead Sea Scrolls, especially the Teacher of Righteousness and Pierced Messiah. Eisenman, Robert James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls, Penguin (Non-Classics), 1998. ISBN 0–14–025773-X; Stegemann, Hartmut The Library of Qumran: On the Essenes, Qumran, John the Baptist, and Jesus. Grand Rapids MI, 1998. See also Broshi, Magen, "What Jesus Learned from the Essenes," Biblical Archaeology Review, 30:1, pg. 32–37, 64. Magen notes similarities between Jesus' teachings on the virtue of poverty and divorce, and Essene teachings as related in Josephus' The Jewish Wars and in the Damascus Document of the Dead Sea Scrolls, respectively. See also Akers, Keith The Lost Religion of Jesus. Lantern, 2000. ISBN 1-930051-26-3.

- ^ Joseph Ratzinger, Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, p. 14

- ^ See Schwietzer, Albert The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede, pp. 370–371, 402. Scribner (1968), ISBN 0–02–089240–3; Ehrman, Bart Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, Oxford University Press USA, 1999. ISBN 0–19–512474-X. Crossan, however, makes a distinction between John's apocalyptic ministry and Jesus' ethical ministry. See Crossan, John Dominic, The Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Jesus, pp. 305–344. Harper Collins, 1998. ISBN 0–06–061659–8.

- ^ This includes the belief that Jesus was the Messiah. Brown, Michael L. Answering Jewish Objections to Jesus: Messianic Prophecy Objections Baker Books, 2003. ISBN 0–8010–6423–6. Brown shows how the Christian concept of Messiah relates to ideas current in late Second Temple period Judaism. See also Klausner, Joseph, The Messianic Idea in Israel: From its Beginning to the Completion of the Mishnah, Macmillan 1955; Patai, Raphael, Messiah Texts, Wayne State University Press, 1989. ISBN 0–8143–1850–9; Crossan, John Dominic, The Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Jesus, pg. 461. Harper Collins, 1998. ISBN 0–06–061659–8. Patai and Klausner state that one interpretation of the prophecies reveal either two Messiahs, Messiah ben Yosef (the dying Messiah) and Messiah ben David (the Davidic King), or one Messiah who comes twice. Crossan cites the Essene teachings about the twin Messiahs. Compare to the Christian doctrine of the Second Coming.

- ^ a b "Zealots." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "Jesus Christ." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "The New Testament was complete, of substantially complete, about AD 100, the majority of the writings being in existence twenty to forty years before this ...the situation is encouraging from the historian's point of view, for the first three Gospels were written at a time when many were alive who could remember the things that Jesus said and did... At any rate, the time elapsing between the evangelic events and the writing of most of the New Testament books was, from the standpoint of historical research, satisfactorily short." Bruce, F. F.: The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable?, pp. 12-14, InterVarsity Press, USA, 1997.

- ^ "The interval then between the dates of the original composition and the earliest extant evidence becomes so small as to be in fact negligible, and the last foundation for any doubt that the Sciptures have come down to us substantially as they were written has now been removed. Both the authenticity and the general integrity of the books of the New Testament may be regarded as finally established." As quoted in Bruce, F. F.: The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable?, p. 20, InterVarsity Press, USA, 1997.

- ^ a b c Ehrman, Bart (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 0-06-073817-0.

- ^ Durant 1944:553–7

- ^ Meier, John P., A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Doubleday: 1991. vol 1: p. 168–171.

- ^ Durant 1944:553-7

- ^ M. Grant, Jesus: An Historian's Review, pp. 199-200

- ^ Bruce, FF (1982). New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? InterVarsity Press, ISBN 087784691X

- ^ Herzog II, WR (2005). Prophet and Teacher. WJK, ISBN 0664225284

- ^ Komoszewski, JE (2006). Reinventing Jesus. Kregel Publications. pp. 195f. ISBN 978-0825429828.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ This section draws on a number of sources to determine the doctrines of these groups, especially the early Creeds, the Catechism of the Catholic Church, certain theological works, and various Confessions drafted during the Reformation including the Thirty Nine Articles of the Church of England, works contained in the Book of Concord, and others.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church §436–40; Thirty Nine Articles of the Church of England, article 2; Irenaeus Adversus Haereses in Patrologia Graeca ed. J. P. Migne (Paris, 1857–1866) 7/1, 93; 2:11 Luke 2:1; 16:16 Matthew 16:16

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church §606–618; Council of Trent (1547) in Denzinger-Schönmetzer, Enchiridion Symbolorum, definitionum et declarationum de rebus fidei et morum (1965) §1529;14:2–3 John 14:2–3

- ^ Thirty Nine Articles of the Church of England, article 9; Augsburg Confession, article 2; Second Helvetic Confession, chapter 8; 5:12–21 Romans 5:12–21; cor 15:21–22 1_Corthians 15:21–22Template:Bibleverse with invalid book.

- ^ Apostles' Creed; Nicene Creed; Catechism of the Catholic Church §441–451; Augsburg Confession, article 3; Luther's Small Catechism, commentary on Apostles' Creed; 16:16–17 Matthew 16:16–17; corinthians 2:8 1_Corinthians 2:8

- ^ Augsburg Confession, article 3; 1:1 John 1:1

- ^ Apostles' Creed; Nicene Creed; Catechism of the Catholic Church §461–463;Thirty Nine Articles of the Church of England, article 2; Luther's Small Catechism commentary on Apostles' Creed; 1:14, 16 John 1:14–16; 10:5–7 Hebrews 10:5–7

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church §456–460; Gregory of Nyssa, Orat. catech. 15 in Patrologia Graeca ed. J. P. Migne (Paris, 1857–1866) 45, 48B; St. Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses 3.19.1 in ibid. 7/1, 939; St. Athanasius, De inc., 54.3 in ibid. 25, 192B. St. Thomas Aquinas, Opusc. in ibid. 57: 1–4; 4:4–5 Galatians 4:4–5

- ^ Apostles' Creed; Nicene Creed; Catechism of the Catholic Church §484–489, 494–507; Luther's Small Catechism commentary on Apostles' Creed

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church §541–546

- ^ Apostles' Creed; Catechism of the Catholic Church §551–553; Augsburg Confession, article 8; Luther's Small Catechism commentary on Apostles' Creed; Second Helvetic Confession, chapter 9; Leo the Great, Sermo 4.3 in Patrologia Latina ed. J. P. Migne (Paris, 1841–1855); 16:18 Matthew 16:18

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church"§1322–1419; Martin Luther, Augsburg Confession, article 10; Luther's Small Catechism: the Sacrament of the Altar

- ^ Apostles' Creed; Nicene Creed;Luther's Small Catechism commentary on Apostles' Creed; Second Helvetic Confession, chapter 9

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church §638–655; Byzantine Liturgy, Troparion of Easter; Thirty Nine Articles of the Church of England, article 4 and 17; Augsburg Confession, article 3; Second Helvetic Confession, chapter 9.

- ^ Apostles' Creed; Nicene Creed; Catechism of the Catholic Church §668–675, 678–679; Luther's Small Catechism commentary on Apostles' Creed; 25:32–46 Matthew 25:32–46

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church §1021-1022

- ^ Fuller 1965, p. 15

- ^ Pliny the Younger: C. Plinius Traino Imperatori Liber Decimus Epistula XCVI

- ^ Nicene Creed; Thirty Nine Articles of the Church of England, article 1; Augsburg Confession, article 1; Second Helvetic Confession, chapter 3; Council of Nicaea I (325) in Denzinger-Schönmetzer, Enchiridion Symbolorum, definitionum et declarationum de rebus fidei et morum (1965) §126; Council of Constantinople II (553) in ibid. §424 and 424; Council of Ephesus in ibid. §255; 1:1 John 1:1; John 8:58; John 10:30

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church §464–469; Thirty Nine Articles of the Church of England, article 2 and 3 Second Helvetic Confession, chapter 9; Council of Ephesus (431) in Denzinger-Schönmetzer, Enchiridion Symbolorum, definitionum et declarationum de rebus fidei et morum (1965) §250; Council of Ephesus in ibid. §251; Council of Chalcedon (451) in ibid. §301 and 302; 4:15 Hebrews 4:15.

- ^ Barth 1956, p. 207

- ^ MacLeod 1998, p. 37-41

- ^ John Calvin, Calvins Calvinism BOOK II Chapter 15 Centers for Reformed Theology and Apologetics [resource online] (1996-2002, accessed 03 June 2006); available here

- ^ H. Orton Wiley, Christian Theology Chapter 22 [resource online] (Nampa, Idaho: 1993-2005, accessed 03 June 2006); available here

- ^ "Doctrine and Covenants 20".

- ^ "Luke 24:39".

- ^ 3 Nephi 11:8

- ^ "Doctrine and Covenants 20".

- ^ “Revelation—Its Grand Climax at Hand!” –1988 | chap. 27 pp. 180-181 par. 15 “God’s Kingdom Is Born!” | . © Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania | “But who is Michael? The name “Michael” means “Who Is Like God?” So Michael must be interested in vindicating Jehovah’s sovereignty by proving that no one is to be compared to Him. In Jude verse 9, he is called “Michael the archangel.” Interestingly, the title “archangel” is used elsewhere in the Bible with reference to only one person: Jesus Christ. Paul says of him: “The Lord himself will descend from heaven with a commanding call, with an archangel’s voice”

- ^ “Insight On The Scriptures 2” –1988 | p. 393 “Michael” | . © Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania | “Scriptural evidence indicates that the name Michael applied to God’s Son before he left heaven to become Jesus Christ and also after his return. Michael is the only one said to be “the archangel,” meaning “chief angel,” or “principal angel.” The term occurs in the Bible only in the singular. This seems to imply that there is but one whom God has designated chief, or head, of the angelic host. At 1 Thessalonians 4:16 the voice of the resurrected Lord Jesus Christ is described as being that of an archangel, suggesting that he is, in fact, himself the archangel”

- ^ "Jesus The Ruler Whose Origin Is From Early Times," The Watchtower (15 June 1998) p. 22. | "Some centuries later came Jesus’ greatest assignment up to that time. Jehovah transferred the life force of his beloved Son from heaven into the womb of Mary. Nine months later she gave birth to a baby boy, Jesus. (Luke 2:1-7, 21)"

- ^ “Reasoning From The Scriptures” –1985 © Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania | p. 257 par. 1 Mary (Jesus’ Mother) “Heb. 2:14, 17, JB: “Since all the children share the same blood and flesh, he Jesus too shared equally in it . . . It was essential that he should in this way become completely like his brothers.” (But would he have been “completely like his brothers” if he had been a God-man?)”

- ^ “Insight On The Scriptures” –1988 | p. 53 “Jesus Christ” | . © Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania | “Doubtless on many occasions during his prehuman existence as the Word, Jesus acted as Jehovah’s Spokesman to persons on earth. While certain texts refer to Jehovah as though directly speaking to humans, other texts make clear that he did so through an angelic representative. (Compare Ex 3:2-4 with Ac 7:30, 35; also Ge 16:7-11, 13; 22:1, 11, 12, 15-18.) Reasonably, in the majority of such cases God spoke through the Word. He likely did so in Eden, for on two of the three occasions where mention is made of God’s speaking there, the record specifically shows someone was with Him, undoubtedly his Son. (Ge 1:26-30; 2:16, 17; 3:8-19, 22) The angel who guided Israel through the wilderness and whose voice the Israelites were strictly to obey because ‘Jehovah’s name was within him,’ may therefore have been God’s Son, the Word.—Ex 23:20-23; compare Jos 5:13-15.”

- ^ Watchtower 9/1/06 1 p. 28 par. 5 “Let Your Petitions Be Made Known to God” © Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania | “5 Jehovah does not lay down a lot of rigid rules on how to pray. Nevertheless, we need to learn the proper approach to God, which is explained in the Bible. For instance, Jesus taught his followers: “If you ask the Father for anything he will give it to you in my name.” (John 16:23) Hence, we are required to pray in Jesus’ name, recognizing Jesus as the sole channel through which God’s blessings are extended to all mankind.”

- ^ 3:16 John 3:16

- ^ 1:15 Colossians 1:15

- ^ 11:36 romans 11:36

- ^ "What Do They Believe?", Watchtower Bible and Tract Society c.f., Retrieved April 14, 2007