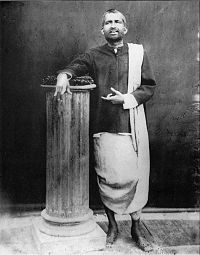

Ramakrishna

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa | |

|---|---|

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa | |

| Born | February 18, 1836 |

| Died | 16 August 1886 (aged 50) Garden House in Cossipore. |

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (Bangla: রামকৃষ্ণ পরমহংস Ramkrishno Pôromôhongsho) (February 18, 1836 - August 16, 1886), born Gadadhar Chattopadhyay (Bangla: গদাধর চট্টোপাধ্যায় Gôdadhor Chôţţopaddhae), [1] was a rustic Bengali religious ecstatic[2] who practiced Vaishnava and Shakti bhakti, Vedanta, Tantra, and other spiritual disciplines. Toward the end of his life, he became a guru to many educated Bengalis, including Narendranath Dutta—the future Swami Vivekananda—and also became an influential figure in the Bengal Renaissance.[3] He was considered an avatar or incarnation of God by many of his disciples, and is considered as such by many of his devotees today. Though recent academic scholarship has concentrated on his ambiguous sexuality,[4] the Ramakrishna Mission and other scholars have criticized the work of these scholars.[5]

Biographical sources

Like Jesus and Socrates, Ramakrishna wrote nothing himself. Some say that he was illiterate or semi-literate.[6] Thus, everything that we know about Ramakrishna comes through the writings of his disciples. Additionally, only a few of the primary sources have been translated into English and scholars find those translations to be highly problematic.[7]

There are four major sources of information for the life of Ramakrishna:

- Ram Chandra Datta's 1885 Srisriramakrsna Paramahamsadever Jivanavrttanta ("The Life of Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa")[8]

- Akshay Kumar Sen's 1901 śrīśrīrāmkrsna punthi ("scriptures of the double-blessed Ramakishna")

- Mahendranath Gupta's 1902-32 Sri-Sri-Ramakrisna-kathamrta ("story-nectar of the double-blessed Ramakrishna")

- Swami Saradananda's 1911 Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lilaprasanga ("divine play of the double-blessed Ramakishna")

There are also other sources, such as Vivekananda's 1896 biographical lecture "My Master", Mahendranath Dutta's Sri Ramakrishner Anudhyan, ("Sacred Memories of Sri Ramakrishna")[9], Satyacharan Mitra's 1897 Sri Sri Ramakrsna Paramahamsadeber Jiboni o Upadesh ("The Life and Teachings of Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa")[10], and Surescanrda Datta's 1886 Sriramakrsnadber Upades.

Datta's Jivanavrttānta

In November of 1894, Vivekananda wrote his disciple Alasingha Perumal a letter, calling Datta's Jivanavrttānta "nonsense", saying that he was "simply ashamed" of it, and giving specific instructions regarding how to write a biography of Ramakrishna (non-bracketed ellipses are in the translation):

- Avoid all irregular indecent expressions about sex etc...because other nations think it the height of indecency to mention such things, and his life in English is going to be read by the whole world.[...]The writer perhaps thought he was a frank recorder of truth and keeping the very language of Paramahamsa. But he does not remember that Ramakrishna would never use that language before ladies. And this man expects his work to be read by men and women alike! Lord, save me from fools! They, again, have their own freaks; they all knew him! Bosh and rot....[11]

On the same day, Vivekananda wrote Singaravelu Mudaliar ("Kidi"):

- ...As to the wonderful stories published about Shri Ramakrishna, I advise you to keep clear of them and the fools who write them. They are true, but the fools will make a mess of the whole thing, I am sure. He had a whole world of knowledge to teach, why insist upon unnecessary things as miracles really are! They do not prove anything.[12]

Religious scholar Jeffrey Kripal says that, although the Ramakrishna Order produced a Bengali version in 1995, the Ramakrishna Mission has suppressed the book in the past, and that Datta was threatened with a lawsuit when the book was originally published.[13] According to Narasingha Sil, Datta's Jivanvrttanta is the most scandalous biography of Ramakrishna, "containing the lurid details of his sadhana as well as his quite suggestive encounters with his patron Mathur."[14] According to Somnath Bhattacharyya, Datta's Jivanavrittanta has not been translated into English.[15]

Vivekananda's "My Master"

Vivekananda gave two lectures on his master in 1896, one in London, and a second in New York. These were later combined and published as “My Master”.[16] Narasingha Sil describes it as "shot through with the author's very personalized interpretation of Ramakrishna's preachings and teaching and his claims on behalf of the Ramakrishna phenomenon.” [17]

1897 edition of The Gospel of Ramakrishna

There was an English translation of portions of Gupta's diary published in 1897 as The Gospel of Ramakrishna. Vivekananda praised it exuberantly.[18]

Sen's Punthi

The 1901 edition of Sen's poetic biography of Ramakrishna incorporated all four parts of his Bhagaban Srisriramakrsna Paramahamsadeber Caritamrta, which were written from 1894-1901[19]. Vivekananda loved the 1894 edition. "I cannot tell in words the joy I have experienced by reading the book," he wrote. However, he also offered editorial suggestions for future editions of Sen's poem.[20]

Gupta's Kathamrta

By far the best known source is Gupta's Kathamrta, five volumes published in 1902, 1905, 1908, 1910 and 1932. It contains vivid descriptions of dialogue between Ramakrishna, his disciples, and visitors. These scenes were recalled or re-imagined by Gupta from notes in his personal diary. Each of the five volumes recapitulates the last six years of Ramakrishna's life. Naransingha Sil speculates that Gupta did not dare to publish the Kathamrta while Vivekananda was still alive.[21]

It was translated into English in 1942 as The Gospel of Ramakrishna by Swami Nikhilananda of the Ramakrishna Mission. Although Nikhilananda calls The Gospel "a literal translation," he substantially altered Gupta's text, combining the five parallel narratives into a single volume (which is often sold as a two-volume set), as well as deleting some passages which he claimed were "of no particular interest to English-speaking readers."[22] According to William Radice, "the standard translation of the Kathamrta by Swami Nikhilananda is bowdlerized, with the 'vulgar expressions' in Ramakrishna's earthy, rustic Bengali either removed or smoothed over: so that 'raman' (sexual intercourse) has become "communion" in the Gospel.'"[23] In a review of Kali's Child, religious scholar Brian Hatcher noted that a passage in the Kathamrta in which Ramakrishna describes how he "...could not resist worshipping the penises of boys with flowers and sandalwood paste" was paraphrased by Nikhilananda as: "I practiced a number of mystic postures" [24]

Malcolm McLean of Otago University translated the entire Kathamrta as his 1983 dissertation, entitled A Translation of the Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita. Only a few copies of this work exist.

Saradananda's Lilaprasanga

Sil speculates that "It is quite possible that Saradananda's Lilaprasanga was influenced by Vivekananda's ideas and suggestions."[25]

In 1952, the Lilaprasanga was translated into English as Ramakrishna the Great Master by Swami Jagadananda of the Ramakrishna Mission. In 2003, the Lilaprasanga was re-translated by Swami Chetanananda of the Ramakrishna Mission as Sri Ramakrishna and His Divine Play.

Biography

Birth and childhood

Various supernatural incidents are recounted by Saradananda in connection with Ramakrishna’s birth. It is said that Kshudiram, Ramakrishna’s father, named him Gadadhar in response to a dream he had had in Gaya before Ramakrishna’s birth, in which Lord Gadadhara, the form of Vishnu worshipped at Gaya, appeared to him and told him he would be born as his son. Chandramani Devi, Ramakrishna’s mother, is said to have had a vision of light entering her womb before Ramakrishna was born. Even in his childhood, some villagers considered Ramakrishna to be an incarnation of God.

According to his biographers, Ramakrishna was born in the village of Kamarpukur, in the Hooghly district of West Bengal, into a very poor but pious brahmin family. The young Ramakrishna, known as Gadadhar, was an extremely popular figure in his village. He was considered handsome and had a natural gift for the fine arts. However, he disliked attending school, and was not interested in earning money. As he was growing up, he was barely literate.[26] He loved nature and spent much time in fields and fruit orchards outside the village with his friends. He would visit with wandering monks who stopped in Kamarpukur on their way to Puri. He would serve them and listen to their religious debates with rapt attention.

When arrangements for Gadadhar to be invested with the sacred thread were nearly complete, he declared that he would have his first alms from a certain low-caste woman of the village, as he had promised this to her. This was met with firm opposition from Gadadhar’s family, as tradition required that the first alms be received from a brahmin, but the boy was adamant that a promise made could not be broken. Finally, Ramkumar, his eldest brother and head of the family after the passing away of their father, gave in.

Meanwhile, the family's financial position worsened every day. Ramkumar ran a Sanskrit school in Calcutta and also served as a purohit priest in some families. About this time, Rani Rashmoni, a rich woman of Calcutta who belonged to the untouchable kaivarta community,[27] founded a temple at Dakshineswar. She approached Ramkumar to serve as priest at the temple of Kali and Ramkumar agreed. Ramkumar recruited assistants among his relatives, including Gadadhar, who agreed only after some persuasion and was given the task of decorating the deity. When Ramkumar passed away in 1856, Gadadhar took his place as priest.

Career as priest

When Gadadhar started worshipping the deity Bhavatarini, he began to question if he was worshipping a piece of stone or a living Goddess. If he was worshipping a living Goddess, why should she not respond to his worship? This question nagged him day and night. Then, he began to pray to Kali: "Mother, you've been gracious to many devotees in the past and have revealed yourself to them. Why would you not reveal yourself to me, also? Am I not also your son?"

He is known to have wept bitterly and sometimes even cry out loudly while worshipping. At night, he would go into a nearby jungle and spend the whole night praying. One day, the famous account goes, he was so impatient to see Mother Kali that he decided to end his life. He seized a sword hanging on the wall and was about to strike himself with it, when he is reported to have seen light issuing from the deity in waves. He is said to have been soon overwhelmed by the waves and fell unconscious on the floor.

Gadadhar, however, unsatisfied, prayed to Mother Kali for more religious experiences. He especially wanted to know the truths that other religions taught. Strangely, these teachers came to him when necessary and he is said to have reached the ultimate goals of those religions with ease. Soon word spread about this remarkable man and people of all denominations and all stations of life began to come to him.

Heterodox religious practices

At Dakshineswar, Ramakrishna engaged in a practice called madhura bhava, in which he imitated the "sweet mood" of the goddess Radha waiting for her lover Krishna. He wore female clothing and jewelry, and imitated female speech and behavior. This practice culminated with a vision of Krishna, in which Krishna's body merged with Ramakrishna's.[26] He said:

- I spent many days as the handmaid of God. I dressed myself in women's clothes, put on ornaments, and covered the upper part of my body with a scarf, just like a woman...Otherwise, how could I have kept my wife with me for eight months? Both of us behaved as if we were the handmaids of the Divine Mother. I cannot speak of myself as a man.[26]

For a period, while he was practicing bhakti, he was supposed to have resembled the monkey-god Hanuman, the servant of Ram. He lived on roots and fruit, and a growth which resembled a tail was supposed to have grown from his spine. Later, Ramakrishna experienced the goddess Sita's body merging with his own (Sita is the consort of Ram).[26]

At some point, Ramakrishna visited Nadia, the home of Chaitanya and Nityananda, the 15th-century founders of Bengali Gaudiya Vaishnava bhakti. He had an intense vision of two young boys merging into his body.[26]

Totapuri and Vedanta

Ramakrishna was initiated in Advaita Vedanta by a wandering monk named Totapuri, in the city of Dakshineswar. Totapuri was "a teacher of masculine strength, a sterner mien, a gnarled physique, and a virile voice". Ramakrishna would soon affectionately address the monk as Nangta or Langta, the "Naked One". Nikhilananda interjects that this is because as a renunciate, Nangta did not wear any clothing.[28]

- I [Ramakrishna] said to Totapuri in despair: "It's no good. I will never be able to lift my spirit to the unconditioned state and find myself face to face with the Atman." He [Totapuri] replied severely: "What do you mean you can't? You must!" Looking about him, he found a shard of glass. He took it and stuck the point between my eyes saying: "Concentrate your mind on that point." [...] The last barrier vanished and my spirit immediately precipitated itself beyond the plane of the conditioned. I lost myself in samadhi.[29]

After the departure of Totapuri, Ramakrishna reportedly remained for six months in a state of absolute contemplation:

- For six months in a stretch, I [Ramakrishna] remained in that state from which ordinary men can never return; generally the body falls off, after three weeks, like a mere leaf. I was not conscious of day or night. Flies would enter my mouth and nostrils as they do a dead's body, but I did not feel them. My hair became matted with dust.[30]

Marriage

Rumors spread to Kamarpukur that Ramakrishna had gone mad as a result of his over-taxing spiritual exercises at Dakshineswar. Alarmed, neighbors advised Ramakrishna’s mother that he be persuaded to marry, so that he might be more conscious of his responsibilities to the family. Far from objecting to the marriage, he, in fact, mentioned Jayrambati, three miles to the north-west of Kamarpukur, as being the village where the bride could be found at the house of one Ramchandra Mukherjee. The five-year-old bride, Sarada, was found and the marriage was duly solemnised in 1859.[31] Ramakrishna was 23 at this point, but the age difference was typical for 19th century rural Bengal. Ramakrishna left Sarada in December 1860 and did not return until May 1867.[31]

According to the Ramakrishna Mission, Sarada was Ramakrishna’s first disciple. He attempted to teach her everything he had learned from his various gurus. She is believed to have mastered every religious secret as quickly as Ramakrishna had. Impressed by her religious potential, he began to treat her as the Universal Mother Herself and performed a puja considering Sarada as a veritable Tripura Sundari Devi.

Yogeshwari and Tantra

In 1861, a female guru named Yogeshwari appeared at Dakshineshwar. Reportedly, she taught Ramakrishna 64 Tantric sadhanas. She tried to teach him kumari-puja ("virgin worship"), — which reportedly can include ritualized copulation with a young girl — but Ramakrishna fainted.[31] Datta said: "We have heard many tales of the brahmani but we hesitate to divulge them to the public."[31]

Sarada, now a young woman, heard rumors of Ramakrishna's bizarre practices and came to Dakshineshwar to protect him from Yogeshwari. They began to relate to each other as husband and wife, but did not consummate their marriage, due to Ramakrishna's severe asceticism.[31]

Islam and Christianity

In 1866, Govinda Roy, a Hindu guru who practiced Sufism, initiated Ramakrishna into Islam. According to Christopher Isherwood, Ramakrishna said:

- I devoutly repeated the name of Allah, wore a cloth like the Arab Moslems, said their prayer five time daily, and felt disinclined even to see images of the Hindu gods and goddesses, much less worship them—for the Hindu way of thinking had disappeared altogether from my mind.

His Muslim practices culminated in Ramakrishna experiencing the prophet Muhammad merging with his body.[26]

Years later, as he contemplated an image of the Madonna and Christ child at a devotee's house, he began a phase of Christian spiritual practice. This phase culminated in a vision of the merging of Ramakrishna's body with that of Christ.[26]

Later life

By the 1870s, Ramakrishna had established a reputation as a mystic and had attracted a large number of male devotees from the emerging urban Bengali bourgeoisie class, most of whom including Narendranath Dutta, had been educated at English schools. He came to be known among his devotees as Sri Ramakrishna Paramahansa. The name Ramakrishna is said to have been given him by Mathur Babu, the son-in-law of Rani Rasmani.[32] Many prominent people of Calcutta like Pratap Chandra Mazumdar, Shivanath Shastri and Trailokyanath Sanyal began visiting him during this time (1871-1885). He also met Swami Dayananda. Through his meetings with Keshab Chandra Sen of the Brahmo Samaj, he had become known to the general populace of Calcutta.

After fifteen years of teaching, in April 1885 the first symptoms of throat cancer appeared and in the beginning of September 1885 he was moved to Shyampukur. But the illness showed signs of aggravation and he was moved to a large garden house at Cossipore on December 11, 1885 on the advice of Dr. Sarkar, who was treating him. On August 15, 1886 his health deteriorated, and at 01:02 a.m. on the 16th he attained mahasamadhi. At noon, Dr. Sarkar pronounced that life had departed not more than half an hour before.[33] He left behind a devoted band of 16 young disciples headed by Swami Vivekananda.

Teachings

God-realisation

The key concepts in Ramakrishna’s teachings were the oneness of existence; the divinity of all living beings; and the unity of God and the harmony of religions.

Ramakrishna emphasised that God-realisation is the supreme goal of all living beings.[34] Religion, for him, was merely a means for the achievement of this goal. Ramakrishna’s mystical realisation, classified by Hindu tradition as nirvikalpa samadhi (literally, "involuntary meditation", thought to be absorption in the all-encompassing Consciousness), led him to know that the various religions are different ways to reach The Absolute, and that the Ultimate Reality could never be expressed in human terms.

Kamini-kanchan

Ramakrishna taught that that the primal bondage in human life is to kaminikanchan, or "women and gold". Devotees insist that this phrase warns against lust and greed, but religion scholars and historians have tended to take it more literally. He seems to have overcome sexual desires by "becoming female":

- A man can change his nature by imitating another's character. By transposing onto yourself the attributes of a woman, you gradually destroy lust and the other sensual drives. You begin to behave like a women. I have noticed that men who play female parts in the theater speak like women or brush their teeth like women while bathing.[26]

Various scholars have come to opposing conclusions about Ramakrishna's attitude toward women. Some say that he was simply an ascetic and avoided lust in order to retain mystical clarity.[citation needed] Others say that he feared women deeply or pathologically, especially women as sexual beings.[citation needed] Narasingha Sil links this to misogyny.[35] Sil also says that Ramakrishna made his wife into a deity in order to avoid thinking of her as sexual.[36]

Avidyamaya and vidyamaya

Devotees believe that Ramakrishna’s realisation of nirvikalpa samadhi also led him to an understanding of the two sides of maya, or illusion, to which he referred as Avidyamaya and vidyamaya. He explained that avidyamaya represents dark forces (e.g. sensual desire, evil passions, greed, lust and cruelty), which keep the world-system on lower planes of consciousness. These forces are responsible for human entrapment in the cycle of birth and death, and they must be fought and vanquished. Vidyamaya, on the other hand, represents higher forces (e.g. spiritual virtues, enlightening qualities, kindness, purity, love, and devotion), which elevate human beings to the higher planes of consciousness. With the help of vidyamaya, he said that devotees could rid themselves of avidyamaya and achieve the ultimate goal of becoming mayatita - that is, free from maya.

Harmony of religions

Ramakrishna recognised differences among religions but realised that in spite of these differences, all religions lead to the same ultimate goal, and hence they are all valid and true. Regarding this, the distinguished British historian Arnold J. Toynbee has written: “… Mahatma Gandhi’s principle of non-violence and Sri Ramakrishna’s testimony to the harmony of religions: here we have the attitude and the spirit that can make it possible for the human race to grow together into a single family – and in the Atomic Age, this is the only alternative to destroying ourselves.” [37]

Other teachings

Ramakrishna’s proclamation of jatra jiv tatra Shiv (wherever there is a living being, there is Shiva) stemmed from his Advaitic perception of Reality. This would lead him teach his disciples, "Jive daya noy, Shiv gyane jiv seba" (not kindness to living beings, but serving the living being as Shiva Himself). This view differs considerably from what Ramakrishna’s followers call the "sentimental pantheism" of, for example, Francis of Assisi.

Ramakrishna, though not formally trained as a philosopher, had an intuitive grasp of complex philosophical concepts.[38] According to him brahmanda, the visible universe and many other universes, are mere bubbles emerging out of Brahman, the supreme ocean of intelligence [39].

Like Adi Sankara had done more than a thousand years earlier, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa revitalised Hinduism which had been fraught with excessive ritualism and superstition in the Nineteenth century and helped it become better-equipped to respond to challenges from Islam, Christianity and the dawn of the modern era[40]. However, unlike Adi Sankara, Ramakrishna developed ideas about the post-samadhi descent of consciousness into the phenomenal world, which he went on to term "vignana". While he asserted the supreme validity of Advaita Vedanta, he also he accepted both the Nitya (or the eternal substance) and the Leela (literally, "play", indicating the dynamic phenomenal reality) as aspects of Brahman.

The idea of the descent of consciousness shows the influence of the Bhakti movement and certain sub-schools of Shaktism on Ramakrishna’s thought. The idea would later influence Aurobindo's views about the Divine Life on Earth.

Ramakrishna’s impact

| Part of a series on | |

| Hindu philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orthodox | |

|

|

|

| Heterodox | |

|

|

|

Born as he was during a social upheaval in Bengal in particular and India in general, Ramakrishna and his movement were an important part of the direction that Hinduism and Indian nationalism took in the coming years.

On Hinduism

His career was an important part of the renaissance that Bengal, and later India, experienced in the 19th century. Hinduism faced a huge intellectual challenge in the 19th century, from Westerners and Indians alike. The Hindu practice of murti came under intense pressure specially in Bengal, then the center of British India, and was declared intellectually unsustainable by some intellectuals. Response to this was varied, ranging from the Young Bengal movement that denounced Hinduism and embraced Christianity or atheism, to the Brahmo movement that retained primacy of Hinduism but gave up idol worship, and to the staunch Hindu nationalism of Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay. Ramakrishna’s influence was crucial in this period for a Hindu revival of a more traditional kind, and can be compared to that of Chaitanya's contribution centuries earlier, when Hinduism in Bengal was under similar pressure from the growing power of Islam.[41]

Among his contributions is a strong affirmation of the presence of the divine in an idol.[42][43] To the many that revered him, this reinforced centuries-old traditions that were in the spotlight at the time. Ramakrishna also advocated an inclusive version of the religion, declaring Joto mot toto path (meaning As many faiths, so many paths). He was given a name that is clearly Vaishnavite (Rama and Krishna are both incarnations of Vishnu), but was a devotee of Kali, the mother goddess, and known to have followed various other religious paths including Tantrism and even Christianity and Islam.

On Indian Nationalism

Ramakrishna’s impact on the growing Indian nationalism was, if more indirect, nevertheless quite notable. A large number of intellectuals of that age had regular communication with him and respected him, though not all of them necessarily agreed with him on religious matters. Numerous members of the Brahmo Samaj respected him. Though some of them embraced his form of Hinduism, the fact that many others didn't shows that they detected in him a possibility for a strong national identity in the face of a colonial adversary that was intellectually undermining the Indian civilisation. As Amaury de Riencourt states,"The greatest leaders of the early twentieth century, whatever their walk of life -- Rabindranath Tagore, the prince of poets; Aurobindo Ghosh, the greatest mystic-philosopher; Mahatma Gandhi, who eventually shook the Anglo-Indian Empire to destruction -- all acknowledged their over-riding debt to both the Swan and the Eagle, to Ramakrishna who stirred the heart of India, and to Vivekananda who awakened its soul."[44] This is particularly evident in Ramakrishna’s development of the Mother-symbolism and its eventual role in defining the incipient Indian nationalism. [45]

Vivekananda, Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission

Vivekananda, Ramakrishna’s most illustrious disciple, is considered by some to be one of his most important legacies. Vivekananda spread the message of Ramakrishna across the world. He also helped introduce Hinduism to the west. He founded two organisations based on the teachings of Ramakrishna. One was Ramakrishna Mission, which is designed to spread the word of Ramakrishna. Vivekananda also designed its emblem. Ramakrishna Math was created as a monastic order based on Ramakrishna’s teachings.

Legacy

It could be argued that Ramakrishna’s vision of Hinduism and its popularisation in the West, by converts like Christopher Isherwood and admirers like Aldous Huxley and Romain Rolland, have largely coloured Western notions of what Hinduism is.

Many great thinkers of the world have acknowledged Ramakrishna's contribution to humanity. Max Müller, who was inspired by Ramakrishna, said:[46]

Sri Ramakrishna was a living illustration of the truth that Vedanta, when properly realised, can become a practical rule of life... the Vedanta philosophy is the very marrow running through all the bones of Ramakrishna’s doctrine.

Leo Tolstoy saw similarities between his and Ramakrishna's thoughts. He described him as a "remarkable sage".[47] Romain Rolland considered Ramakrishna to be the "consummation of two thousand years of the spiritual life of three hundred million people." He said[48]:

Allowing for differences of country and of time, Ramakrishna is the younger brother of Christ.

Mohandas Gandhi wrote:[49]

Ramakrishna's life enables us to see God face to face. He was a living embodiment of godliness.

Sri Aurobindo considered Ramakrishna to be an incarnation, or avatar, of God on par with Gautama Buddha.[50] He wrote:

When scepticism had reached its height, the time had come for spirituality to assert itself and establish the reality of the world as a manifestation of the spirit, the secret of the confusion created by the senses, the magnificent possibilities of man and the ineffable beatitude of God. This is the work whose consummation Sri Ramakrishna came to begin and all the development of the previous two thousand years and more since Buddha appeared has been a preparation for the harmonisation of spiritual teaching and experience by the Avatar of Dakshineshwar.

Christopher Isherwood also considered Ramakrishna to be an incarnation of God. [51]

Jawaharlal Nehru described Ramakrishna as "one of the great rishis of India, who had come to draw our attention to the higher things of life and of the spirit."[52] Subhas Chandra Bose was also influenced by Ramakrishna. He said:[53]

The effectiveness of Ramakrishna's appeal lay in the fact that he had practised what he preached and that... he had reached the acme of spiritual progress.

Contemporary reception

In 1991, historian Narasingha Sil wrote Ramakrishna Paramahamsa. A Psychological Profile, an account of Ramakrishna that suggests that Ramakrishna's mystical experiences were pathological and originated from alleged childhood sexual trauma.[54]Other scholars, most notably psychologist Sudhir Kakar, judged Sil's study to be simplistic and misleading.[55] Sil's theory has also been viewed as reductive by William B. Parsons, who has called for an increased empathetic dialogue between the classical/adaptive/transformative schools and the mystical traditions for an enhanced understanding of Ramakrishna's life and experiences.[56]

In 1991, Sudhir Kakar wrote "The Analyst and the Mystic." [57] Gerald James Larson wrote, "Indeed, Sudhir Kakar...indicates that there would be little doubt that from a psychoanalytic point of view Ramakrishna could be diagnosed as a secondary transsexual."[58] Kakar sought a meta-psychological non-pathological explanation that connects Ramakrishna's mystical realization with creativity. Kakar also argues that culturally relative concepts of eroticism and gender have contributed to the Western difficulty in comprehending Ramakrishna.[55]In 2003, Sudhir Kakar wrote a novel, Ecstasy, in which an aspiring sadhu in 20th century India endures sexual molestation as a child, and has a feminine appearance and ambiguous sexuality. According to the author, the characters were modelled on Ramakrishna and Vivekananda.[59]

In 1995, Jeffrey Kripal wrote Kali's Child: The Mystical and the Erotic in the Life and Teachings of Ramakrishna, which he called a psychoanalytic study of Ramakrishna.[60][61] Kali's Child's conclusion is that "Ramakrishna’s mystical experiences...were in actual fact profoundly, provocatively, scandalously erotic."[62] Kali's Child provoked controversy after Narasingha Sil wrote a scathing review of Kali's Child in The Statesman which produced a great deal of angry correspondence.[63] In subsequent articles, Kripal's translations, his conclusions, and his authority to apply psychoanalysis to Ramakrishna were questioned by several scholars, including Alan Roland, Huston Smith, and Somnath Bhattacharya.[64][65][66] According to Brian Hatcher, although some had their misgivings, the overall verdict of scholars of religion and of experts on South Asian culture regarding Kali's Child has been approving, and at times highly laudatory.[67] Kripal responded to the criticisms in journal articles and postings on his website, but stopped participating in the discussion in late 2002.[68]

Attempts by modern authors to psychoanalyze Ramakrishna are questioned by practicing psychoanalyst Alan Roland, who has written extensively about applying Western psychoanalysis to Eastern cultures,[69][70][71][72] and charges that psychoanalysis has been misapplied to Ramakrishna.[73][74] Roland decries the facile decoding of Hindu symbols, such as Kali’s sword and Krishna’s flute, into Western sexual metaphors—thereby reducing Ramakrishna’s spiritual aspiration to the basest psychopathology.[75] The conflation of Ramakrishna’s spiritual ecstasy, or samadhi, with unconscious dissociated states due to repressed homoerotic feelings is not based on common psychoanalytic definitions of these two different motivations, according to Roland.[76] He also writes that it is highly questionable whether Ramakrishna’s spiritual aspirations and experiences involve regression—responding to modern attempts to reduce Ramakrishna’s spiritual states to a subconscious response to an imagined childhood trauma.[77]

In 2006, composer Philip Glass wrote The Passion of Ramakrishna, a choral work. It premiered on September 16, 2006 at the Orange County Performing Arts Center in Costa Mesa, California, performed by Orange County’s Pacific Symphony Orchestra conducted by Carl St. Clair with the Pacific Chorale directed by John Alexander.[78]

References

- ^ Smart, Ninian The World’s Religions (1998) p.409, Cambridge

- ^ Narasingha P. Sil, "Vivekananda's Ramakrishna: An Untold Story of Mythmaking and Propaganda" Numen 40 (1): Jan 1993 p 38-62 "However, the transformation of Ramakrishna from religious ecstatic to a religious eclectic, especially a Vedantin prophet of the highest caliber, is an interesting development that calls for a closer scrutiny."

- ^ Sumit Sarkar (1999). "Post-Modernism and the Writing of History" (PDF). Studies in History. 15 (2). SAGE Publications: 293–322.

Finding traces in the Kathamrita of a learned literate knowledge unlearned oral wisdom binary, I had seen it as evidence of a liminal moment, where a rustic near-illiterate Brahmin becomes the guru of highly educated bhadralok.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|quotes=ignored (help) - ^ McLean 1983; Kakar 1991; Sil 1991, 1998, 2003; Larson 1997; Radice 1998; Kripal 1998; Hatcher 1999

- ^ Bhattacharya, "Kali's Child: Psychological And Hermeneutical Problems", Tyagananda 2000; Roland, "The Uses (and Misuses) Of Psychoanalysis in South Asian Studies: Mysticism and Child Development", 2002

- ^ Narasingha P. Sil, "Vivekananda's Ramakrishna: An Untold Story of Mythmaking and Propaganda" Numen 40 (1): Jan 1993 p 61

- ^ Sil, 1993; Hatcher, 1999; McLean, 1983; Radice, 1995; Kripal 1998

- ^ Amiya P. Sen, "Sri Ramakrishna, the Kathamrita and the Calcutta middle Classes: an old problematic revisited" Postcolonial Studies, 9: 2 p 176

- ^ Amiya P. Sen, "Sri Ramakrishna, the Kathamrita and the Calcutta middle Classes: an old problematic revisited" Postcolonial Studies, 9: 2 p 176

- ^ Amiya P. Sen, "Sri Ramakrishna, the Kathamrita and the Calcutta middle Classes: an old problematic revisited" Postcolonial Studies, 9: 2 p 176

- ^ Wikisource, The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, Volume 5, XXII. There are ellipses in the edition of Vivekananda's letters from which this text is quoted. It seems that text has been removed by the editors. My ellipses are bracketed.

- ^ Ellipses are in the translation of Vivekananda's letters. The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 5

- ^ Jeffrey Kripal, "Pale Plausibilities: A Preface for the Second Edition" "I have also, I believe, overplayed the degree to which the tradition has suppressed Datta's Jivanavrttanta. Indeed, to my wonder (and embarrassment), the Ramakrishna Order reprinted Datta's text the very same summer Kali's Child appeared, rendering my original claims of a conscious concealment untenable with respect to the present (but still solidly in place with respect to the past--Datta, after all, faced a possible lawsuit, and Satyacharan Mitra, Ramakrishna's "second biographer," hints that many were deeply troubled and offended by earlier treatments of Ramakrishna's life, a likely reference to Datta's text)."

- ^ Narasingha P. Sil, "Vivekananda's Ramakrishna: An Untold Story of Mythmaking and Propaganda" Numen 40 (1): Jan 1993 p 38-62

- ^ "The point is, unlike the LP the much smaller Jivanavrittanta text remains as yet untranslated into English, and Kripal can safely read and translate it to his convenience." "Kali's Child: Psychological And Hermeneutical Problems"

- ^ Marie Louise Burke, page number needed

- ^ Sil, "Vivekananda's Ramakrishna", 55

- ^ Narasingha P. Sil, "Vivekananda's Ramakrishna: An Untold Story of Mythmaking and Propaganda" Numen 40 (1): Jan 1993 p 52

- ^ Sil, "Vivekananda's Ramakrishna", p 60

- ^ Narasingha P. Sil, "Vivekananda's Ramakrishna: An Untold Story of Mythmaking and Propaganda" Numen 40 (1): Jan 1993 p 50

- ^ Narasingha P. Sil, "Vivekananda's Ramakrishna: An Untold Story of Mythmaking and Propaganda" Numen 40 (1): Jan 1993 p 50

- ^ Kripal 1995, (329-336)

- ^ William Radice[1], untitled review of Rāmakṛṣṇa Paramahaṁsa: A Psychological Profile by Narasingha P. Sil Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 58, No. 3, (1995), pp. 589-590 Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African Studies http://www.jstor.org/stable/620150

- ^ The Nikhilananda quotation is from 1996: 814. Brian A. Hatcher, "Kali's Problem Child: Another look at Jeffrey Kripal's study of Sri Ramakrishna" International Journal of Hindu Studies 3: 2 (Aug 1999), p 170-171 The Bengali is as follows: "...sei avasthāy cheleder dhan, phul-candan diye pūjā nā ka'rle thākte pārtām na (Gupta 1987, 4:232)"

- ^ Narasingha P. Sil, "Vivekananda's Ramakrishna: An Untold Story of Mythmaking and Propaganda" Numen 40 (1): Jan 1993 p 50

- ^ a b c d e f g h Parama Roy, Indian Traffic: Identities in Question in Colonial and Post-Colonial India Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998

- ^ Amiya P. Sen, "Sri Ramakrishna, the Kathamrita and the Calcutta middle Classes: an old problematic revisited" Postcolonial Studies, 9: 2 p 176

- ^ Swami Nikhilananda, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna (1972), Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, New York

- ^ Roland, Romain The Life of Ramakrishna (1984), Advaita Ashram

- ^ Swami Nikhilananda, Ramakrishna, Prophet of New India, New York, Harper and Brothers, 1942, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e Sil, Divine Dowager, p. 42

- ^ Life of Sri Ramakrishna, Advaita Ashrama, Ninth Impression, December 1971, p. 44

- ^ Last days

- ^ Kathamrita, 1/10/6

- ^ Sil, Divine Dowager, p. 52

- ^ Sil, Divine Dowager, p. 55

- ^ Contributions of Sri Ramakrishna to World Culture

- ^ Hixon, Lex, Great Swan: Meetings with Ramakrishna, (New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1992, 2002), p. xvi

- ^ Gospel of Ramakrishna, vol. 4

- ^ Das, Prafulla Kumar, "Samasamayik Banglar adhymatmik jibongothone Sri Ramakrishner probhab", in Biswachetanay Ramakrishna, (Kolkata: Udbodhon Karyaloy, 1987,1997- 6th rep.), pp.299-311

- ^ Mukherjee, Jayasree, "Sri Ramakrishna’s Impact on Contemporary Indian Society". Prabuddha Bharata, May 2004 Online article

- ^ Swami Saradananda,Sri Sri Ramakrishna Leelaproshongo, (Kolkata:Udbodhon Karyaloy, 1955), Part I, pp.113-125

- ^ Gupta, Mahendranath, Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita, (Kolkata: Kathamrita Bhavan, 1901, 1949 17th edition), Part I, pp. 20-21

- ^ de Riencourt, Amaury, The Soul of India, (London: Jonathan Cape, 1961), p.250

- ^ Jolly, Margaret,"Motherlands? Some Notes on Women and Nationalism in India and Africa".The Australian Journal of Anthropology,Volume: 5. Issue: 1-2,1994

- ^ Vedanta Society of New York

- ^ World Thinkers on Ramakrishna-Vivekananda, The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, pp.15-16

- ^ The Life of Ramakrishna, Advaita Ashrama

- ^ Life of Sri Ramakrishna, Advaita Ashrama, Foreword

- ^ World Thinkers on Ramakrishna-Vivekananda, The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, p.16

- ^ Ramakrishna and His Disciples, Advaita Ashrama, p.2

- ^ World Thinkers on Ramakrishna-Vivekananda, The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, p.28

- ^ World Thinkers on Ramakrishna-Vivekananda, The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, p.29

- ^ Sil, Narasingha, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa. A Psychological Profile, (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 1991), p.16

- ^ a b Kakar, Sudhir, The Analyst and the Mystic, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), p.34

- ^ Parsons, William B., The Enigma of the Oceanic Feeling: Revisioning the Psychoanalytic Theory of Mysticism, (New York, Oxford University Press, 1999), pp.125-139

- ^ In The Indian Psyche, 125-188. 1996 New Delhi: Viking by Penguin. Reprint of 1991 book.

- ^ Gerald James Larson (Autumn 1997). "Polymorphic Sexuality, Homoeroticism, and the Study of Religion". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 65 (3). London: Oxford University Press: 655–665.

- ^ "The characters are modelled on Ramakrishna and Vivekananda." The Rediff Interview/Psychoanalyst Sudhir Kakar Date accessed: 1 April 2008

- ^ Kripal, Jeffrey J.: Kali's Child

- ^ Kripal, Jeffrey J., Kali's Child: The Mystical and the Erotic in the Life and Teachings of Ramakrishna, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995, 1998)

- ^ Jeffrey J. Kripal, Kali's Child: The Mystical and the Erotic in the Life and Teachings of Ramakrishna, p. 2

- ^ Brian A. Hatcher (August 1999). "Kali's problem child: Another look at Jeffrey Kripal's study of Ramakrishna". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 3 (2). World Heritage Press Inc: 165–82.

Most of the people in the room were familiar with the book, since not long before there had been a scathing review of the book and a welter of angry correspondence in the pages of Calcutta's major English daily, the Statesman. Judging from those reviews, one would have thought Kali's child had to be right up there with Lady Chatterly's lover.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|quotes=ignored (help) Sil went even further when "in one Calcutta newspaper, The Statesman, Narasingha Sil recently decried Kripal as a shoddy scholar with a perverse imagination who has thoughtlessly "ransacked" another culture and produced a work which is, in short, "plain shit" (January 31, 1997)..." Urban, Hugh (Apr., 1998). "Kālī's Child: The Mystical and the Erotic in the Life and Teachings of Ramakrishna". The Journal of Religion. Vol. 78, No. 2: pp. 318-320. Retrieved 2008-03-18.{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Smith derided Kripal's work as "colonialism updated".Smith, Huston (Spring 2001). "Letters to the Editor". Harvard Divinity Bulletin. 30/1: Letters.

- ^ "Freud never had access to non-Western patients, so he never established the validity of his theories in other cultures. This is a point emphasized by Alan Roland, who has researched and published extensively to show that Freudian approaches are not applicable to study Asian cultures." Ramaswamy and De Nicholas, p. 39.

- ^ Somnath Bhattacharyya is emeritus professor and former head of the Psychology Department at Calcutta University(Ramaswamy and DeNicholas, p. 152), and a practicing psychotherapist(Ramaswamy and DeNicholas, p. 152) who is fluent in Bengali(Ramaswamy and DeNicholas, p. 152) and familiar with the primary source material used by Kripal(Ramaswamy and DeNicholas, p. 152). In addition to pointing out that Kripal is not qualified in psychoanalysis, he says the textual errors in Kali’s Child are “particularly grave”, and “large scale distortions of source material in an ill attempted effort at establishing a thesis, is certainly not academically acceptable.” Ramaswamy and DeNicholas, p. 162.

- ^ Brian A. Hatcher (August 1999). "Kali's problem child: Another look at Jeffrey Kripal's study of Ramakrishna". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 3 (2). World Heritage Press Inc: 165–82.

As a glance at the reviews will show, Kali's child has been praised by scholars of religion (see Haberman 1997; Parsons 1997) and by experts on South Asian culture more generally (see Radice 1998; Vaidyanathan 1997). Granted, some of these reviewers have their misgivings--and later in this essay I will raise one of my own---but their overall verdict has been an approving, and at times highly laudatory, one.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|quotes=ignored (help) - ^ Kali's Child

- ^ Roland, Alan. (1996) Cultural Pluralism and Psychoanalysis: The Asian and North American Experience. Routledge. ISBN 0415914787.

- ^ Roland, Alan (1998) In Search of Self in India and Japan: Toward a Cross-cultural Psychology. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691024588.

- ^ Roland, A. (1991). Sexuality, the Indian Extended Family, and Hindu Culture. J. Amer. Acad. Psychoanal., 19:595-605.

- ^ Roland, A. (1980). Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Personality Development in India. Int. R. Psycho-Anal., 7:73-87.

- ^ Roland, Alan (October 1972). "Ramakrishna: Mystical, Erotic, or Both?". Journal of Religion and Health. 37: 31–36.

- ^ Roland, Alan. (2007) The Uses (and Misuses) Of Psychoanalysis in South Asian Studies: Mysticism and Child Development. Invading the Sacred: An Analysis of Hinduism Studies in America. Delhi, India: Rupa & Co. ISBN 978-8129111821

- ^ Roland, Ramakrishna: Mystical, Erotic, or Both?, p. 33.

- ^ Roland, Ramakrishna: Mystical, Erotic, or Both?, p. 33.

- ^ Roland, The Uses (and Misuses) Of Psychoanalysis in South Asian Studies: Mysticism and Child Development, published in Invading the Sacred: An Analysis of Hinduism Studies in America. Delhi, India: Rupa & Co. ISBN 978-8129111821, p. 414.

- ^ Philipglass.com

Further reading

- Bhattacharyya, Somnath. "Kali's Child: Psychological And Hermeneutical Problems". Infinity Foundation. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- Chetanananda, Swami (1990). Ramakrishna As We Saw Him. St. Louis: Vedanta Society of St Louis. ISBN 978-0916356644.

- Gupta, Mahendranath (1985). The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna. Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center. ISBN 978-0911206012.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hixon, Lex. Great Swan: Meetings With Ramakrishna. Burdett, N.Y: Larson Publications. ISBN 0-943914-80-9.

- Paul Hourihan. Ramakrishna & Christ, the Supermystics: New Interpretations. Vedantic Shores Press. ISBN 1-931816-00-X.

- Isherwood, Christopher. Ramakrishna and His Disciples. Hollywood, Calif: Vedanta Press. ISBN 0-87481-037-X.

- Kripal, Jeffrey J. (1994). "Kālī's Tongue and Ramakrishna: 'Biting the Tongue' of the Tantric Tradition". University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- Jeffrey J. Kripal (1995). Kali's Child: The Mystical and the Erotic in the Life and Teachings of Ramakrishna. University of Chicago Press.

- Max Muller. Ramakrishna: His Life and Sayings. Advaita Ashrama. ISBN 81-7505-060-8.

- Rajagopalachari, Chakravarti (1973). Sri Ramakrishna Upanishad. Vedanta Press. ASIN B0007J1DQ4.

- Ramaswamy, Krishnan (2007). Invading the Sacred: An Analysis of Hinduism Studies in America. Delhi, India: Rupa & Co. ISBN 978-8129111821.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Rolland, Romain (1929). Life of Ramakrishna. Vedanta Press. ISBN 978-8185301440.

- Saradananda, Swami (2003). Sri Ramakrishna and His Divine Play. St. Louis: Vedanta Society. ISBN 978-0916356811.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Saradananda, Swami (1952). Sri Ramakrishna The Great Master. Sri Ramakrishna Math. ASIN B000LPWMJQ.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Satyananda Saraswati. Ramakrishna: The Nectar of Eternal Bliss. Devi Mandir Publications. ISBN 1-877795-66-6.

- Torwesten, Hans (1999). Ramakrishna and Christ, or, The paradox of the incarnation. The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture. ISBN 978-8185843971.

- Ananyananda, Swami (1981). Ramakrishna: a biography in pictures. Advaita Ashrama, Calcutta. ISBN 978-8185843971.

- Tyagananda, Swami. "Kali's Child Revisited or Didn't Anyone Check the Documentation?". Infinity Foundation. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

External links

- Ramakrishna, His Life and Sayings by Max Müller

- My Master- from Vivekananda's 1896 Lectures on Ramakrishna

- Ramakrishna Kathamrita literally, The Nectar of Ramakrishna’s Words

- Works of Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda

- Was Ramakrishna a Hindu? Article by Dr. Koenraad Elst

- Official website of the Headquarters of Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission

- Direct Disciples of Sri Ramakrishna

- Main page of Ramakrishna Math, Chennai