History of Canada

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Canada |

|---|

|

Inhabited for millennia by First Nations (aboriginals), Canada has evolved from a group of European colonies into a bilingual, multicultural federation, having peacefully obtained sovereignty from its last colonial possessor, the United Kingdom. France sent the first large group of settlers in the 17th century, but the collection of territories and colonies now comprising Canada came to be ruled by the British until attaining full independence in the 20th century.

Prehistory

According to archeological and genetic evidence, North and South America were the last continents in the world to be inhabited by human beings. The most widely accepted theory is that during the last ice age, the Wisconsin glaciation, falling sea levels allowed people to move across the Bering land bridge which joined Siberia to Alaska. At that point, they were blocked by the massive glaciers that covered most of Canada, which confined them to Alaska for thousands of years. Alaska, however, is believed to have been generally ice-free due to low snowfall, allowing a small population to exist. Sometime around 16,500 years ago, the glaciers began melting, allowing people to move south and east into Canada. The exact migration route is uncertain, however two main possibilities have been proposed. One is that people walked south via an ice-free corridor on the east side of the Rocky Mountains, and then fanned out across North America before continuing on to South America. The other is that they migrated, either on foot or using primitive boats, down the Pacific Coast to the tip of South America, and then crossed the Rockies and Andes to populate the rest of the lands. Either or both are possible, but evidence of the latter would have been covered by a sea level rise of hundreds of metres since the last ice age. Regardless of their entry route or method, the descendants of the original paleoindians lived in Canada for 10,000 to 17,000 years before Europeans arrived.

European contact

There are several reports of contact made before Christopher Columbus between the first peoples and those from other continents.

The earliest known European explorations in Canada are described in the Icelandic Sagas, especially the Saga of Erik the Red and Saga of the Greenlanders which document the attempted Norse colonization of the Americas. According to the sagas, the first European to see Canada was Bjarni Herjólfsson, a Norse merchant who was blown off course en route from Iceland to Greenland in the summer of 985 or 986. He found himself off a heavily forested coast to his west, and knowing that Greenland had no forests, followed the coast north to the latitude of the Greenland settlement, and then turned east and sailed to Greenland. Bjarni sold his boat to Leif Erikson, who sailed with a crew of 35 to investigate Bjarni's discovery around the year 1000 or so. Leif made landings in three places, the first which he called Helluland or "land of the flat stones", and the second which he called Markland or "land of forests". Many historians have identified Helluland with Baffin Island and Markland with Labrador. His third landing was at a place he called Vinland, where he reportedly found grapes growing wild. Following Leif's voyage, several Norse groups attempted to colonize the new land, but they were driven out by the native people.[1] Erikson is credited as being the first European to set foot on North America.

Archaeological evidence of a Viking settlement was found in L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, a UNESCO World Heritage Site which generally matches the description of Leif's landing place in Vinland, except that grapes do not grow there today. However, the Norse explorations occurred during the Medieval Warm Period, when it may have been warmer. The artifacts at L'Anse aux Meadows include evidence of iron smelting, bronze pins, nails, spindles, and knitting needles, which are clearly Norse in origin and also show that women were present as well as men.[2]

The presence of Basque cod fishermen and whalers, just a few years after Columbus discovered the Americas, has also been cited, with at least nine fishing outposts having been established on Labrador and Newfoundland. The largest of these settlements was Red Bay, where several stations were established. Basque whaling began in southern Labrador in mid-16th century. There are claims on the Pacific Coast that Buddhist missionaries sent east by the Chinese Emperor may have made contact with British Columbia and other parts of North America, and while some Asian artifacts have been found in British Columbia, there is no hard evidence these are connected to the search for Fusang.

The next European explorer acknowledged as landing in what is now Canada was John Cabot, an Italian who was under the patronage of Henry VII of England. He sailed west from Bristol, England in an attempt to find a trade route for King Henry VII to the Orient. He ended up landing somewhere on the coast of North America (probably Newfoundland or Cape Breton Island) in 1497 and claimed it for King Henry VII of England. Cabot was confident he had found a new seaway to Asia and on a second voyage the following year he explored and charted the east coast of North America from Baffin Island to Maryland. His voyages gave England a claim by right of discovery to an indefinite amount of area of eastern North America, in fact, it's later claims to Newfoundland, Cape Breton and neighoburing regions were based partly on Cabot's exploits. Of great significance were Cabot's reports of immensely rich fishing waters. The Roman Catholic countries of Western Europe furnished the fishing market, and every year after 1497 an international mixture of fishing vessels staked grounds off the southeast shore of Newfoundland and east of Nova Scotia. Sometimes these ships would traverse into Gulf of St. Lawrence, encountering native peoples on the shore who would trade their valuable furs for trinkets and other items brought by the fishers.

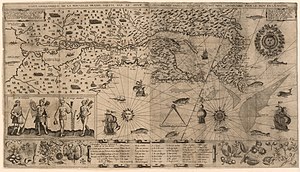

Portuguese and Spanish explorers also visited Canada, but the French first began to explore further inland and set up colonies. In 1524 King Francis I of France sent a florentine navigator, Giovanni da Verrazano, on a voyage of reconnaissance overseas. He explored the eastern coastline of North America from North Carolina to Newfoundland, giving France some claim to the new world as well. Ten years later in 1534 Francis I would follow up on the work of Verrazano by dispatching an expedition under Jacques Cartier to report on the lands he discovered and the people he met. Cartier named most of the important coasts of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and viewed by Anticosti Island what might be the mouth of a great river. An attempt to penetrate beyond the St. Lawrence River was carried out by Cartier the following year on a second expedition. Cartier traveled up stream with three small vessels where he discovered the native village of Stadacona, near the present day city of Quebec. 150 miles further up the river Cartier came upon an island in the river where he discovered another native settlement called Hochelaga on the site of present day Montreal. The Lachine Rapids blocked his navigation further upstream and Cartier would return to France before making one last expedition. In 1541 made his third and last voyage up the St. Lawrence, leading a group of French colonists under Jean Francois de la Rocque which would mark the first attempt by France to settle in Canada. The project failed though and 60 colonists died before the attempt was abandoned and France would not attempt further colonization for another 60 years.

Throughout the rest of the 16th century the European fleets continued to make almost annual visits to the eastern shores of Canada to cultivate the fishing opportunities there. A sideline industry emerged as well though in the unorganized traffic of furs. In Europe methods of processing the furs developed and Beavers pelt hats became particularly fashionable. European countries encouraged the development of this infant trade and thus a new emphasis was put on settlement in Canada. In 1598, Troilus de Mesgouez, marquis de la Roche, set out for Canada armed with a new kind of authority--a royal monopoly which gave him the exclusive right to trade in furs. La Roche established a small colony on Sable Island, southeast of Nova Scotia. The settlement, which was a dismal failure, was the first of many French sponsored colonization attempts in Canada with the promise of a monopoly on the fur trade. An attempt at settlement was made in 1600 at Tadoussac by Pierre Chauvin; the settlement failed, but Tadoussac remained a trading post.[3]

In 1604 the fur trade monopoly was granted to Pierre du Guast. de Guast led his first colonization expedition to an island located near to the mouth of the St. Croix River. Among his lieutenants was a geographer named Samuel de Champlain, who promptly carried out a major exploration of the northeastern coastline of what is now the United States. Under Samuel de Champlain, the St. Croix settlement was moved to Port-Royal (today's Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia), a new site across the Bay of Fundy, on the shore of the Annapolis Basin, an inlet in western Nova Scotia. Britain also had a presence in Newfoundland, and with the advent of settlements they claimed the south of Nova Scotia as well as the areas around the Hudson Bay. It was France's most successful colony to date and the settlement came to be known as Acadia. The French claimed Canada as their own, and 6,000 settlers arrived, settling along the St. Lawrence and in the Maritimes. The cancellation of de Guast's fur monopoly in 1607 brought the Port Royal settlement to a temporary end. Champain was able to persuade de Guast though to allow him to take some colonists and settle on the St. Lawrence, where in 1608 he would found France's first permanent colony in Canada at Quebec.

The first contact with the Europeans was disastrous for the first peoples. Explorers and traders brought European diseases, such as smallpox, which killed off entire villages. Relations varied between the settlers and the Natives. The French befriended several Algonquin nations, the Huron (Wyandot) people and nations of the Wabanaki Confederacy, and entered into a mutually beneficial trading relationship with them. The Iroquois, however, became dedicated opponents of the French, and warfare between the two was unrelenting, especially as the British armed the Iroquois in an effort to weaken the French.

The first agricultural settlements were located around the French settlement of Port Royal in what is now Nova Scotia. The population of Acadians, as this group became known, reached 5,000 by 1713.

New France 1604–1763

Main Article: New France

After Champlain's founding of Quebec City in 1608, it became the capital of New France. The early days of the French colony were hard and the population grew slowly. Champlain took personal administration over the city and it's affairs and sent out expeditions to explore the interior land. Champlain himself discovered Lake Champlain in 1609; and by 1615 he had traveled by canoe up the Ottawa River, through Lake Nipissing and through Georgian Bay to the center of Huron country, near Lake Simcoe. During these voyages Champlain aided the Huron's in their battles against the Iroquois Confederacy. As a result, the Iroquois would become mortal enemies of the French. In 1629 Champlain suffered the humiliation of having to surrender his almost starving garrison to an English fleet, and he himself was taken prisoner back to England. Peace had been declared by England and France however before the surrender, and the settlement was restored to French rule. Champlain would return from Europe to spend his remaining years in the colony. He became governor of New France in 1633.

The coastal communities of New France were based upon the cod fishery, and the economy along the St. Lawrence River was based on farming. French voyageurs travelled deep into the hinterlands (of what is today Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba, as well as what is now the American Midwest and the Mississippi Valley) trading guns, gunpowder, cloth, knives, and kettles for beaver furs. The fur trade kept the interest in Frances overseas colonies alive, yet only encouraged a small population, however, as minimal labour was required, and also discouraged the development of agriculture, the surest foundation of a colony in the New World. Encouraging settlement was difficult, and while some immigration did occur, by 1759 New France only had a population of some 65,000. New France had other problems besides low immigration. The French government had little interest or ability in supporting their colony, and it was mostly left to its own devices. The economy was primitive, and much of the population was involved in little more than subsistence agriculture. The colonists also engaged in a long running series of wars with the Iroquois.

Despite it's problems New France continued to grow; however slowly. Settlers founded Trois-Rivieres, farther up the St. Lawrence, in 1634. The farthest outpost of New France for many years was Montreal, founded by Paul de Chomedy on May 18, 1642. First known as Ville-Marie, this settlement, one day to become Canada's largest city, was begun as a mission post. One of the most famous of the leaders who accompanied de Cgomedy was Jeanne Mance, founder of the Hotel-Dieu, the first hospital at Ville-Marie. The establishing of Montreal was part of a large Missionary movement based in France. Over the next 40 years after Quebec's founding, dozens of missionary posts would be built in Huron territory. The Huron's were under threat of attack from Iroquois tribes dwelling south and east of Lake Ontario. In 1648 the Iroquois invaded Huronia and wiped out most of the Huron's and French missionaries living in the territory. The Iroquois threat became a great obstacle against New France expansion. The French settlers and Iroquois would fight many battles around the outskirts of New France.

The feudal system of landholding, which had long been established in France, was adopted in the colony. The nobles, in this case the seigneurs, were granted lands and titles by the king in return for their oath of loyalty and promise to support him in time of war. The seigneur in turn granted rights to work farm plots on his land to his vassals, or habitants. In exchange, the habitants were required to pay certain feudal dues each year, to work for the seigneur for a given number of days annually, and to have their grain ground in the seigneurial mill. In underpopulated New France the habitants welcomed the fact that the seigneur was obligated to build a mill. They had no military duties to perform except their common defense against the Indians. There was little money and not much use for it; and so the taxes took the form of payments in chickens, geese, or other farm products. These obligations were hardly burdensome. The seigneurs were anxious that their habitants should wish to stay farmers, and there was as much land as anyone could till.

As in France, there was nothing resembling a democratic system of government in the colony. The senior official was the governor, appointed by the king. In the exercise of his almost absolute power he felt more responsible to the king in France than to the people he governed. Another post of French officialdom was established in Canada in 1665 with the appointment of an intendant, whose chief duties concerned finance and the administration of justice. However, there was sufficient overlapping of authority between governor and intendant to breed more jealousy than cooperation between the two offices. Jean Talon, who arrived in the colony in 1665, brought about rapid expansion of New France as it's first intendant. He encouraged agriculture, immigration businesses and exploration of the region. In 1672 Count Louis de Frontenac arrived in the colony as governor. He built a fort at Cataraqui, near present-day Kingston, and brought the Iroquois into an enforced peace. He directed a series of major exploratory voyages to the interior. Among the greatest explorations were those made by Louis Jolliet, Father Jacques Marquette, and Rene Cavelier, sieur de La Salle. By 1682, however, the troubles between Frontenac and the intendant, Jacques Duchesneau, had become so serious that the king recalled both governor and intendant.

Wars in the colonial era

While the French were well established in large parts of Eastern Canada, Britain had control over the Thirteen Colonies to the south; and laid claim (from 1670, via the Hudson's Bay Company) to Hudson Bay, and its drainage basin (known as Rupert's Land). The British colonies were rapidly expanding, while the French fur traders and explorers were extended long by thinly. La Salle's exploration of the Mississippi to its mouth in 1682 gave France a claim to a vast area bordering the American Colonies from the Great Lakes and the Ohio River valley southward to the Gulf of Mexico. England had feared the fact France threatened to control almost half the continent which would give them indisputable control of the fur trade, an industry England was just realizing could be more profitable then gold. Thus England was quick to follow up on it's claim to the back-door route towards fur country by establishing the Hudsons Bay Company in 1670. French expansion soon began to threaten it's claim though, and in 1686 Pierre Troyes led an overland expedition from Montreal to the shore of the bay where they managed to capture many of the company's forts by surprise. New France would wage several naval raids into the bay the following years and almost succeeded in driving the English from this part of the continent altogether.

Britain and France repeatedly went to war in the 17th and 18th centuries and made their colonial empires into battlefields. Numerous naval battles were fought in the West Indies; the main land battles were fought in and around Canada. The first areas won by the British were the Maritime provinces. After Queen Anne's War, Nova Scotia, other than Cape Breton, was ceded to the British by the Treaty of Utrecht. This gave Britain control over thousands of French-speaking Acadians. Not trusting these new subjects, who repeatedly proclaimed their neutrality, the British first tried to dilute their numbers by bringing in Protestant settlers from Europe. Finally the British ordered the Great Upheaval of 1755, deporting about 12,000 Acadians to destinations throughout their North American holdings. Many settled in southern Louisiana, creating the Cajun culture there. Some Acadians managed to hide and others eventually returned to Nova Scotia, but they were far outnumbered by a new migration of Yankees from New England who transformed Nova Scotia.

During King George's War, British colonial forces captured the French stronghold of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, but this gain was returned to France under the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.

Canada was also an important battlefield in the Seven Years' War, during which Great Britain gained control of Quebec City after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759, and Montreal in 1760.

Canada under British imperial control 1764–1867

With the end of the Seven Years' War and the signing of the Treaty of Paris on February 10, 1763, France ceded almost all of its territory in North America. The new British rulers left alone much of the religious, political and social culture of the French-speaking habitants. Violent conflict continued during the next century, leading Canada into the War of 1812 and a pair of Rebellions in 1837.

The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and the United Kingdom with the British North American colonies being used as pawns.[4] Although the causes of the war are still being debated by historians, one the most common assumptions is that the tensions in the maritime region between the United States and Britain reached a boiling point.[4] Although not as important as the tensions between the two powers in the Maritimes, another speculation is that the United States went to war with plans of invading Canada and annexing them to the United States.[4] Another possible reason for the war was the tensions that were rising on the western front, which was becoming increasingly more difficult to navigate.[4] The United States Congress declared war on Britain in June 1812, with the majority of the votes coming from delegates of the south and the west, who believed that the only way to expand westward would be to defeat Canada, as well as the Natives, and that would open the west.[4]

The War of 1812 ended with the Treaty of Ghent of 1814, and the Rush-Bagot agreement of 1817.[4] Neither side saw any land gains or losses; the only people who really lost were the Natives who fought for the British and were important in turning the U.S. away from Canada, and they received nothing except to choose between the United States or the British who may be more charitable.[4] One thing that the War of 1812 did accomplish was the shifting of American migration from north into Upper Canada to west into Ohio and Michigan.[4] The war was another example of Canada rejecting the United States and their idea of republicanism.[4]

In 1837, rebellions against the British colonial government took place in both Upper and Lower Canada. In Upper Canada, a band of Reformers under the leadership of William Lyon Mackenzie took up arms in a disorganized and ultimately unsuccessful series of small-scale skirmishes around Toronto, London, and Hamilton.

In Lower Canada, a more substantial rebellion occurred against British rule. Both English- and French-Canadian rebels, with some U.S. backing, fought several skirmishes against the authorities. The towns of Chambly and Sorel were taken by the rebels, and Quebec City was isolated from the rest of the colony. Montreal rebel leader Robert Nelson read a declaration of independence to a crowd at Napierville in 1838. Les Patriotes, however, were defeated after battles across Quebec. Hundreds were arrested, and several villages were burnt in reprisal.

A new Whig government sent Lord Durham to examine the situation, and his Durham Report strongly recommended responsible government. A less well received recommendation, however, was the amalgamation of Upper and Lower Canada in order to forcibly assimilate the French speaking population; The Canadas were merged into a single, quasi-federal colony, the United Province of Canada, with the Act of Union (1840).

On the Pacific, competing imperial claims between Russia, Spain and Britain were compounded by treaties between the former two powers and the United States, which pressed for annexation of most of what is now British Columbia. Although the boundary between Rupert's Land and Louisiana Territory was resolved at the 49th Parallel in 1818 (with Britain losing most of the rich arable lands of the Red River Valley, west of the Rockies the two powers came to an agreement "not to decide" and established what has been called "joint occupancy" over the lands known to the Hudson's Bay Company as the Columbia District, and to the Americans as the Oregon Country. This arrangement was ended, under the prospect of potential war over the issue, by the Oregon Treaty of 1846, which extended the 49th Parallel west of the Rockies to the Strait of Georgia, a result which saw Britain give up claims to lands north of the Columbia River which were the focus of what is known as the Oregon boundary dispute. The Colony of Vancouver Island was chartered from some of the remaining British territories in 1849, followed by the Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands in 1853, and by the creation of the Colony of British Columbia in 1858, with the latter two founded expressly to keep those regions from being overrun and annexed by American gold miners. In 1863 the Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands was merged into the Colony of British Columbia, which until that time had consisted only of the mainland (and no islands). The Island and Mainland Colonies were shepherded into union in 1866 because of mounting debts and economic inviability and also to prepare the way for merger with Confederation, which came in 1871.

A set of proposals called the Seventy-Two Resolutions were drafted at the 1864 Quebec Conference. They laid out the framework for uniting British colonies in North America into a federation. They were adopted by the majority of the provinces of Canada and became the basis for the London Conference of 1866. The move towards uniting the British North American provinces and territories began out of several of concerns; one was English Canadian nationalism which sought to unite the lands into one country. Concerns over U.S. expansion westward which could endanger the British colonies also helped foster a desire to formally unify the colonies. On a political level, there was a desire for the expansion of responsible government and elimination of the legislative union of Upper and Lower Canada, and their replacement with provincial legislatures in a federation. This was especially pushed by the liberal Reform movement of Upper Canada and the French-Canadian rouges in Lower Canada who favoured a decentralized union in comparison to the Upper Canadian Conservative party and to some degree the French-Canadian bleus which favoured a centralized union.[5]

Post-Confederation Canada 1867–1914

On July 1 1867, with the coming into force of the British North America Act (enacted by the British Parliament), the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia became a federation, regarded as a kingdom in her own right.[6] John A. Macdonald had spoken of "founding a great British monarchy" and wanted the newly created country to be called the "Kingdom of Canada."[7] Although it had its monarch in London, the Colonial Office opposed as "premature" and "pretentious" the term "kingdom", as it was felt it might antagonize the United States. The term dominion was chosen to indicate Canada's status as a self-governing colony of the British Empire, the first time it was used in reference to a country.

With the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, the new country expanded east, west and north, to assert its authority over a greater territory. Manitoba joined the Dominion in 1870, British Columbia in 1871, and Prince Edward Island in 1873. British Columbia, upset that the promises of the original agreement were not being met, threatened to withdraw from Confederation but was finally mollified by the project's resurrection; the railway to BC was not completed until 1885, ten years after it was supposed to have been completed. In 1871, territory was lost to the Americans in an arbitration of the San Juan Island dispute, which had resulted from vagaries in the wording of the 1846 Oregon Treaty.

A major means to achieve the westward expansion of Canada was the foundation of the North-West Mounted Police (now the Royal Canadian Mounted Police), which was founded as a "paramilitary organization" to "subdue the West" as laid out in its charter's opening words. The NWMP's first mission was to suppress the stated desire for independence by the region's Métis inhabitants, which erupted in the form of the Red River Rebellion and the North-West Rebellion. In 1905, Saskatchewan and Alberta were admitted as provinces.

Tension with the United States over western borders continued into the early years of the 20th Century, with the US threatening to invade and annex British Columbia if Britain and Canada did not comply with American territorial demands. The Hay-Herbert Treaty of 1903, which like the treaty ending the San Juan dispute was aribtrated by the German Emperor, saw the loss of British Columbia to mainland parts of what is now the Alaska Panhandle, which had been leased from Russian America since 1839. As with previous disputes on the Pacific, London and Ottawa ignored British Columbia's protests and gave up the region rather than risk war with the United States.

World wars

Canada's participation in the First World War helped to foster a sense of Canadian nationhood. The highpoints of Canadian military achievement came at the Battle of Vimy Ridge on April 9 1917, and later, what became known as Canada's 100 Days. At Vimy the Canadian Corps captured a fortified German hill that had resisted British and French attacks earlier in the war. In the Autumn of 1918, the last 100 days of the war have been labeled Canada's 100 Days in that the Canadian Corps repeatedly spearheaded Allied attacks, with the 4 Canadian Divisions defeating well over 40 German Divisions during this period. The result was that the Canadian Corps became one of the most respected battle tested groups on the Allied side, and one of the most feared by the Germans who referred to them as shock troops. The reputation Canadian troops earned, along with the success of Canadian flying aces including William George Barker and Billy Bishop, helped to give the nation a new sense of identity. As a result of the war, the Canadian government became more assertive and less deferential to British authority, because many Canadians were dismayed by what they saw as British command failures.

Canada is sometimes considered to be the country hardest hit by the interwar Great Depression. The economy fell further than that of any nation other than the United States. It hit especially hard in Western Canada, where a full recovery did not occur until the Second World War began in 1939. Hard times led to the creation of new political parties such as the Social Credit movement and the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, as well as popular protest in the form of the On to Ottawa Trek.

Canada's involvement in the Second World War began when Canada declared war on Germany on September 10 1939, one week after Britain. Canadian forces were involved in the failed defence of Hong Kong, the Dieppe Raid in August 1942, the Allied invasion of Italy, and the Battle of Normandy. Of a population of approximately 11.5 million, 1.1 million Canadians served in the armed forces in the Second World War. Many thousands more served in the merchant marines. In all, more than 45,000 gave their lives, and another 55,000 were wounded. Countless others shared the suffering and hardship of war. By the end of the war, Canada had, temporarily at least, become a significant military power. However, the Big Three paid little attention to Canada.

Conscription legislation was enacted during both wars (though on the initial promise of home-front service only in World War II), leading to increased tension between French and English Canadians. During the First World War, Prime Minister Robert Borden's government enfranchised women who had close male relatives serving overseas, in the hopes of securing their support in the 1917 federal election.

1945–1960

Prosperity returned to Canada during Second World War. With continued Liberal governments, national policies increasingly turned to social welfare, including universal health care, old-age pensions, and veterans' pensions.

The financial crisis of the Great Depression, soured by rampant corruption, had led Newfoundlanders to relinquish responsible government in 1934 and become a crown colony ruled by a British governor. Prosperity returned when the U.S. military arrived in 1941 with over 10,000 soldiers and huge investments in air and naval bases. Popular sentiment grew favourable toward the United States, alarming the Canadian government, which now wanted Newfoundland to enter into confederation instead of joining with the U.S. In 1948, the British government gave voters three Referendum choices: remaining a crown colony, returning to Dominion status (that is, independence), or joining Canada. Joining the U.S. was not made an option. After bitter debate Newfoundlanders voted to join Canada in 1949 as a province.[8]

Canada's foreign policy during the Cold War was closely tied to that of the U.S., which was demonstrated by membership in NATO, sending combat troops into the Korean War, and establishing a joint air defence system (NORAD) with the U.S. The federal government's desire to assert sovereignty in the High Arctic was one of the reasons for the High Arctic relocation, in which scores of Inuit were moved from Northern Quebec to barren Cornwallis Island[9], which decades later was the subject of a long investigation by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.[10]

1960–1981

In the 1960s, a Quiet Revolution took place in Quebec, overthrowing the old establishment which centred on the Catholic Church and modernizing the economy and society. Québécois nationalists demanded independence, and tensions rose until violence erupted during the 1970 October Crisis. During his long tenure in the office (1968–79, 1980–84), Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau made social and cultural change his political goal for Canada.

1982–1992

In 1982, the Canada Act was passed by the British parliament and granted Royal Assent by Queen Elizabeth II on March 29, while the Constitution Act was passed by the Canadian parliament and granted Royal Assent by the Queen on April 17, thus patriating the Constitution of Canada. Previously, the constitution has existed only as an act passed of the British parliament, and was not even physically located in Canada. At the same time, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was added in place of the previous Bill of Rights. The patriation of the constitution was Trudeau's last major act as Prime Minister; he resigned in 1984.

The Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney began efforts to recognize Quebec as a "distinct society" and end western alienation. The National Energy Program was scrapped and in 1987, talks began with Quebec to officially have Quebec sign the Canadian Constitution. Under Mulroney, relations with the United States improved and both Canada and the U.S. began to grow more closely integrated. In 1986, Canada and the U.S. signed the Acid Rain Treaty to reduce acid rain. In 1989, the federal government adopted the Free Trade Agreement with the United States despite significant animosity from the Canadian public who were concerned about the economic and cultural impacts of close integration with the United States.

During the Oka crisis in 1990, the Canadian armed forces was sent in to stop a protest by aboriginals who refused to allow the building of a golf club on land claimed by aboriginals.

1992–present

In the 1990s, anger in predominantly French-speaking Quebec with the failure of constitutional reform talks, and the rising sense of alienation in Canada's western provinces due to the government's preoccupation with attempting to convince Quebec's government to officially endorse the Constitution. After Mulroney resigned as Prime Minister in 1993, Kim Campbell took over and became Canada's first woman Prime Minister. Campbell only remained in office for a few months and the 1993 election saw the collapse of the Progressive Conservative Party from government to only 2 seats, while two new regional political parties: the Quebec-based sovereigntist Bloc Québécois became the official opposition and the largely Western Canada-supported Reform Party of Canada took most of Canada's western ridings. In 1995, the government of Quebec held a second referendum on sovereignty that was rejected by a slimmer margin of just 50.6% to 49.4%.[11] In 1997, the Canadian Supreme Court ruled unilateral secession by a province to be unconstitutional, and Parliament passed the Clarity Act outlining the terms of a negotiated departure.[11]

The 1990s was a period of economic turmoil in Canada as Canada suffered from high unemployment in the early 1990s and a large debt and deficit that had been accumulating for years. Both Progressive Conservative and Liberal governments in the federal government and Progressive Conservative governments in Alberta and Ontario made major cutbacks in social welfare spending and significant privatization of government-provided services, government-owned corporations (crown corporations), and utilities occurred during this period as a means to end government deficit and reduce government debt.

In 1995, a controversial standoff in Ipperwash, Ontario resulted in an aboriginal protester being shot dead and a subsequent inquiry discovered prevalent racism amongst the police officers involved in the standoff. Despite this a number of high-profile changes occurred to improve aboriginal rights, such as the signing of the Nisga'a Final Agreement, a treaty between the Nisga'a people, the provincial government of British Columbia and the federal government signed in 1999 which resolved land claims issues. The federal government responded to demands by the Arctic Inuit people for self-governance and in 1999 granted the creation of the territory of Nunavut, which allowed the Inuktitut language to be an official language of the new territory.

In the 2000s, significant social and political changes have occurred in Canada. Canada's border control policy and foreign policy were altered as a result of the political impact of the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States in 2001 resulting in increased pressure from the U.S. and adoption by Canada of initiatives to secure Canada's side of the border to the U.S. and Canada supported U.S.-led military action in Afghanistan. Canada did not support the U.S.-led war in Iraq in 2003 which led to increased political animosity between the Canadian and U.S. governments at the time.

Environmental issues increased in importance in Canada resulting in the signing of the Kyoto Accord on climate change by Canada's Liberal government in 2002 but recently nullified by the present government which has proposed a "made-in-Canada" solution to climate change. A merger of the Canadian Alliance and PC Party into the Conservative Party of Canada was completed in 2003, ending a ten year division of the conservative vote, and was elected as a minority government under the leadership of Stephen Harper in the 2006 federal election, ending thirteen years of Liberal party dominance in elections.

In 2006, the House of Commons passed a motion recognizing the Québécois as a nation within Canada, and,

in 2008, the Prime Minister officially apologized on behalf of the sitting Cabinet for the endorsement by previous cabinets of the Canadian residential school system, which had promoted forced cultural assimilation oppression of aboriginal peoples, and in which physical and emotional abuse took place. Canada's aboriginal leaders accepted the apology.

See also

Power

- Territorial evolution of Canada

- List of Canadian monarchs

- History of monarchy in Canada

- Military history of Canada

- Diffusion of technology in Canada

- Economic history of Canada

Prosperity

Creativity

Other

- List of Canadian historians

- History of the United Kingdom

- History of England

- History of France

- History of North America

Film, television and culture

- Canada: A People's History

- Canadian pioneers in early Hollywood

- History of Canadian animation

- History of cinema in Canada

- Postage stamps and postal history of Canada

Notes

- ^ Pálsson, Hermann (1965). The Vinland sagas: the Norse discovery of America. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0140441549.

- ^ "L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada". Parks Canada. 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ The Canadian Encyclopedia, Tadoussac, retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i John Herd Thompson and Stephen J. Randall, Canada and the United States: Ambivalent Allies (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2002), 19-24

- ^ Romney, Paul (1999). Getting it Wrong: How Canadians Forgot Their Past and Imperilled Confederation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p.78

- ^ The Crown in Canada

- ^ Farthing, John; Freedom Wears a Crown; Toronto, 1957

- ^ Karl Mcneil Earle, "Cousins of a Kind: The Newfoundland and Labrador Relationship with the United States", American Review of Canadian Studies, Vol. 28, 1998

- ^ McGrath, Melanie. The Long Exile: A Tale of Inuit Betrayal and Survival in the High Arctic. Alfred A. Knopf, 2006 (268 pages) Hardcover: ISBN 0007157967 Paperback: ISBN 0007157975

- ^ The High Arctic Relocation: A Report on the 1953-55 Relocation by René Dussault and George Erasmus, produced by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, published by Canadian Government Publishing, 1994 (190 pages)[1]

- ^ a b Dickinson, John Alexander (2003). A Short History of Quebec (3rd edition ed.). Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2450-9.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2007) |

Further reading

- See Bibliography of Canadian History for an extensive list of sources.

- The Dictionary of Canadian Biography(1966-2006), thousands of scholarly biographies of those who died by 1930

- Bercuson, David J., Canada and the Burden of Unity (MacMillan, 1977).

- Bercuson, David J., The Collins dictionary of Canadian history: 1867 to the present, 1988.

- Bercuson, David J. & Granatstein, J. L., Dictionary of Canadian Military History (Oxford University Press, 1994).

- Bercuson, David J. & Granatstein, J. L., War and Peacekeeping, 1990.

- Bliss, Michael. Northern Enterprise: Five Centuries of Canadian Business. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1987.

- Brune, Nick and Sweeny, Alastair.History of Canada Online. Waterloo: Northern Blue Publishing, 2005.

- Bumsted, J.M. The Peoples of Canada: A Pre-Confederation History; and The Peoples of Canada: A Post-Confederation History. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Conrad, Margaret and Finkel, Alvin. Canada: A National History. Toronto: Pearson Education Canada, 2003.

- Conrad, Maragaret and Finkel, Alvin eds. Foundations: Readings in Post-Confederation Canadian History. and Nation and Society: Readings in Post-Confederation Canadian History. Toronto: Pearson Longman, 2004. articles by scholars

- Costain, Thomas B., The White and the Gold: The French Regime in Canada (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co, Inc., 1960).

- Dickason, Olive P. Canada's First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times (2001).

- Francis, R. Douglas & Smith, Donald B., eds., Readings in Canadian History 3rd ed (1990).

- Who Killed Canadian History? / Jack Granatstein (2007) ISBN 0002008955

- Hallowell, Gerald, ed. The Oxford Companion to Canadian History (2004) 1650 short entries

- Marsh, James C., ed. The Canadian Encyclopedia 4 vol 1985; also cd-rom editions

- McKay, Ian, Rebels, Reds, Radicals: Rethinking Canada's Left History, Between the lines 2006, ISBN 1896357970

- Morton, Desmond. A Short History of Canada 5th ed (2001)

- Morton, Desmond. A Military History of Canada (1999)

- Morton, Desmond. Working People: An Illustrated History of the Canadian Labour Movement (1999)

- Myers, Gustavus. "History of Canadian Wealth" 1914 "His facts are not denied, but his inferences from them will not be admitted generally. All he says may be true, and yet there are other offsetting facts which compensate for the blemishes disclosed." http://www.yamaguchy.netfirms.com/7897401/myers/myers_index.html

- Norrie K. H. and Owram, Doug. A History of the Canadian Economy, 1991

- Pryke, Kenneth G. and Soderlund, Walter C., eds. Profiles of Canada. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press, 2003. 3rd edition.

- Taylor, M. Brook, ed. Canadian History: A Reader's Guide. Vol. 1.

- Owram, Doug, ed. Canadian History: A Reader's Guide. Vol. 2. Toronto: 1994. historiography

- Statistics Canada. Historical Statistics of Canada. 2d ed., Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 1983.

- Canadawiki features hundreds of stories from Canadian History as well as the CanText text library and CanLine Chronology of Canadian History.

- Thorner, Thomas and Frohn-Nielsen, Thor, eds. "A Few Acres of Snow": Documents in Pre-Confederation Canadian History, and "A Country Nourished on Self-Doubt": Documents on Post-Confederation Canadian History, 2nd ed. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2003.

- Wade, Mason, The French Canadians, 1760-1945 (1955) 2 vol