French Communist Party

French Communist Party | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Marie-George Buffet (General Secretary) |

| Founded | 1920 (SFIC) 1921 (PCF) |

| Headquarters | 2, place du Colonel Fabien 75019 Paris |

| Ideology | Communism |

| European affiliation | European Left |

| European Parliament group | European United Left–Nordic Green Left |

| International affiliation | unknown |

| Colours | Red, yellow |

| Website | |

| www.pcf.fr | |

The French Communist Party (Template:Lang-fr or PCF) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. Although its electoral support has greatly declined in recent decades, it remains the largest party in France advocating communist views, and retains a large membership (behind only that of the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) and the Socialist Party (PS)) and considerable influence in French politics. It is a member of the European Left group. Since its participation in François Mitterrand's government, however, it has sometimes been considered by the far left to be a social democratic party. It supports alter-globalization movements although it may sometimes also criticize them (in particular their alleged lack of organization). After a poor performance in the legislative election of 2007, the party was unable, for the first time in the history of the Fifth Republic, to gain the minimum level of 20 deputies in order to form a parliamentary group by itself. The PCF then allied itself with the Greens and other left-wing MPs to be able to form a parliamentary group to the left of the Socialist Party, called Gauche démocrate et républicaine (Democratic and Republican Left).

History

Foundation

The PCF was founded in 1920 by those in the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) who supported the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and opposed World War I.

Tensions within the Socialist Party had emerged in 1914 with the start of the First World War, which saw the majority of the SFIO take what left-wing socialists called a "social-chauvinist" line in support of the French war effort. At the Tours congress of the SFIO in 1920, the left-wing faction (Boris Souvarine, Fernand Loriot) and the center faction (Ludovic Frossard, Marcel Cachin) had agreed to join the Third International, and consequently to fulfill the 21 conditions imposed by Vladimir Lenin. They obtained 3/4 of the votes of the representatives and split away to form the Section Française de l'Internationale Communiste (SFIC). Nevertheless, the majority of the elects and MPs was reluctant towards the principle of the "democratic centralism", written in Lenin's conditions, and remained in the SFIO.

The founders of the SFIC took with themselves the party paper L'Humanité, founded by Jean Jaurès in 1904, with them, which remained tied to the party until the 1990s. The newly created party, later renamed Parti Communiste Français (PCF), was three times larger than the SFIO (120 000 members). Ho Chi Minh, who would create the Viet Minh in 1941 and then declare the independence of Vietnam, was one of the founding members.

1920s and early 1930s

Although at first the PCF rivalled the SFIO for leadership of the French socialist movement, but many members were expelled from the party (including Boris Souvarine), and within a few years its support declined, and for most of the 1920s it was a small and isolated party. Its first elected deputies were opposed to the Cartel des gauches ("Left-wing coalition") formed by the SFIO and the Radical-Socialists. The first Cartel governed from 1924 to 1926.

The Communist Party attracted various intellectuals and artists in the 1920s, including André Breton, the leader of the surrealist movement, Henri Lefebvre (who would be expelled in 1958), Paul Éluard, Louis Aragon, etc.

In the late 1920s the policies of the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin, under which the PCF denounced the SFIO as "social fascists" and refused any co-operation, kept the left weak and divided. Like all Comintern parties, the PCF underwent a process of "Stalinisation" in which a pro-Stalin leadership under Maurice Thorez was installed in 1930 and all internal dissent banned.

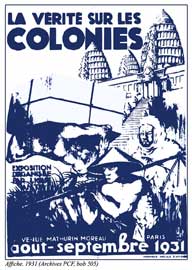

The PCF was the main organizer of a counter-exhibition to the 1931 Colonial Exhibition in Paris, called "The Truth on the Colonies". In the first section, it recalled Albert Londres and André Gide's critics of forced labour in the colonies and others crimes of the New Imperialism period; in the second section, it opposed "imperialist colonialism" to "the Soviets' policy on nationalities".

The second Cartel des gauches was elected in 1932. This time, although the PCF did not take part in the coalition, it did support the government without participating in it (soutien sans participation), in the same way that before World War I (1914-18) the socialists had supported the Republicans and the Radicals' governments without participating. This second Cartel fell following the far-right 6 February 1934 riots, which forced president of the Council Edouard Daladier to pass on the power to conservative Gaston Doumergue. Following this crisis, the PCF, as the whole of the socialist movement, feared that a fascist conspiracy had almost succeeded. Furthermore, Adolf Hitler's access to power in 1933 and the destruction of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) following the 27 February 1933 Reichstag fire and Stalin's new "popular front" policy led the PCF to get closer to the SFIO. Thus, the Popular Front was prepared, and got elected in 1936.

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the following Great Depression, which affected France in 1931, caused much anxiety and disturbance, as in other countries. As economic liberalism failed, new solutions were being looked for. The technocracy ideas were born during this time (Groupe X-Crise), as well as autarky and corporativism in the fascism movement, which advocated union of workers' and employers. Some socialist members became attracted to these new ideas, among whom Jacques Doriot. A member of the Presidium of the Executive Committee of the Comintern from 1922 on, and from 1923 on Secretary of the French Federation of Young Communists, later elected to the French Chamber of Deputies, he came to advocate an alliance between the Communists and Social Democrats. Doriot was then expelled in 1934, and with his followers. Afterwards he moved sharply to the right and formed the Parti Populaire Français, which would be one of the most collaborationist parties during Vichy.

In 1934 the Tunisian Federation of PCF became the Tunisian Communist Party.[1]

The Popular Front

During the 1930s the PCF grew rapidly in size and influence, its growth fuelled by the popularity of the Comintern's Popular Front strategy, which allowed an alliance with the SFIO and the Radicals to fight against fascism. The Popular Front won the 1936 elections, and Léon Blum formed a Socialist-Radical government. The PCF supported this government but did not join it. The Popular Front government soon collapsed under the strain of domestic (financial problems, including inflation) and foreign policy issues (the radicals were against an intervention in the Spanish Civil War while the socialists and communists were in favour), and was replaced by Edouard Daladier's government.

On August 12, 1936, a party organization was formed in Madagascar, the Communist Party (French Section of the Communist International) of the Region of Madagascar.[2]

World War II

After the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the PCF was declared a proscribed organisation by Edouard Daladier's government. At first the PCF reaffirmed its committment to national defense, but after Comintern addressed French Communists by declaring the war to be 'imperialist', the party changed its stance. PCF members of Parliament signed a letter calling for peace and a favorable view of Hitler's forthcoming peace proposals. Party leader, Maurice Thorez, deserted the army and fled to Moscow in order to escape prosecution. [3]

During the occupation the relationship between the Communists and the occupation was strained. One of the major actions organized by the Communists against the occupation forces was a demonstration of thousands of students and workers, which was staged in Paris on Nov. 11, 1940. In May 1941, the PCF helped to organize more than 100,000 miners in the Nord and Pas-de-Calais departments in a strike. On 26 April 1941, the PCF called for a National Front for the independence of France with the Gaullists. [4]

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, the PCF expanded Resistance efforts within France notably advocating the use of direct action and political assassinations which had not been systematically organized up until this point. By 1944 the PCF had reached the height of its influence, controlling large areas of the country through the Resistance units under its command. Some in the PCF wanted to launch a revolution as the Germans withdrew from the country, but the leadership, acting on Stalin's instructions, opposed this and adopted a policy of co-operating with the Allied powers and advocating a new Popular Front government. Many well-known figures joined the party during the war, including Pablo Picasso, who joined the PCF in 1944.

Fourth Republic (1947-58)

The Communists had done particularly well from their war-time efforts in the Resistance, in terms of both organisation and prestige. With the liberation of France in 1944, the PCF, along with other resistance groups, entered the government of Charles de Gaulle. As in post-war Italy, the communists were at that time very popular and a strong political force. The PCF was nicknamed the "party of the 75,000 executed people" (le parti des 75 000 fusillés) because of its important role during the Resistance,

By the close of 1945 party membership stood at half a million, an enormous increase from its pre-Popular Front figure of less than thirty thousand. In the elections of 21 October 1945 for the then-unicameral interim Constitutional National Assembly, the PCF had 159 deputies elected out of 586 seats. Two subsequent elections in 1946, first still for the Constitutional National Assembly, then for the National Assembly of the new Fourth Republic – now the lower house of a bicameral system – gave very similar results. In the election of November 1946, the PCF received the most votes of any party, finishing narrowly ahead of the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) and the Christian democratic Popular Republican Movement (MRP). The party's strong electoral showing and surge in membership led some observers, including American under-secretary of state Dean Acheson, to believe that a Communist takeover of France was imminent. However, as in Italy, the PCF was forced to quit Paul Ramadier's government in May 1947 in order to secure Marshall Plan aid from the United States.

The Italian Communist Party (PCI) was never to return to power, despite a historic compromise attempt in the 1970s, and the PCF was also isolated until François Mitterrand's electoral victory in 1981. A strong political force, the PCF nevertheless remained isolated due to persistent anti-communism. It thus began to pursue a more militant policy, alienating it from the SFIO and allowing the right-wing parties to stay in power.

The PCF, no longer restrained by the responsibilities of office, was free after 1947 to channel the widespread discontent among the working class with the poor economic performance of the new Fourth Republic. Furthermore, the Party was under orders from Moscow to take a more radical course, reminiscent of the Third Period policy once pursued by the Comintern. In September 1947 several European Communist parties came to a meeting at Szklarska Poręba in Poland, where a new international agency, the Cominform, was set up. During this meeting Andrei Zhdanov, standing in for Joseph Stalin, denounced the 'moderation' of the French Communists, even though this policy had been previously approved by Moscow.

Out of government, and newly instructed, the PCF denounced the administration as the tool of American capitalism. Following the arrest of some steel workers in Marseille in November, the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT), the Communist dominated Trade Union block, called a strike, as PCF activists attacked the town hall and other 'bourgeoise' targets in the city. When the protests spread to Paris, and as many as 3 million workers came out on strike, Ramadier resigned, fearing that he faced a general insurrection. This is probably the closest France came to a Communist take-over.

This development was prevented by the determination of Robert Schuman, the new Prime Minister, and Jules Moch, his Minister of the Interior. It was also prevented by a growing sense of disquiet among sections of the labour movement with Communist tactics, which included the derailment in early December of the Paris-Tourcoing Express, which left twenty-one people dead. Sensing a change of mood, the CGT leadership backed down and called off the strikes. From this point forward the PCF moved into permanent opposition and political isolation, a large but impotent presence on the political map of France.

During the 1950s, the PCF critically supported French imperialism during the Indochina War (1947-54) and the Algerian War (1954-62), although many French communists also worked against colonialism. Thus Jean-Paul Sartre, a "comrade" of the Communist party, actively supported the National Liberation Front (FLN) (the porteurs de valises networks, in which Henri Curiel took part). Long debates took place on the role of conscription. While this stance by the PCF may have helped it retain widespread popularity in metropolitan France, it lost it credibility on the radical left. During his scholarship to study radio engineering in Paris (from 1949 to 1953), Pol Pot, like many other colonial elites educated in France (Ho Chi Minh in 1920), joined the French Communist Party.

The second half of the 1950s was also marked by some dissatisfaction with the pro-Moscow line continuously pursued by party leaders. However, no definitive eurocommunist aspirations developed at the time. A major split occurred as Maoists left during the late 1950s. Some moderate communist intellectuals, such as historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, disillusioned with the actual policies of the Soviet Union, left the party after the violent suppression of Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

In 1959 the PCF federation in Réunion was separated from the party, and became the Reunionese Communist Party.[5]

1960s and 1970s

In 1958, the PCF was the only big party which opposed Charles de Gaulle's return to power and the French Fifth Republic. Little by little, it was joined in opposition by the center and center-left parties. It advocated left-wing union against De Gaulle. Waldeck Rochet became PCF leader after Thorez's death in 1964.

In the mid 1960s the U.S. State Department estimated the party membership to be approximately 260 000 (0.9% of the working age population of France).[6]

For the 1965 presidential election, thinking a Communist candidate could not obtain a good result, it supported the candidacy of François Mitterrand. Then, it made an electoral agreement with the Federation of the Democratic and Socialist Left coming up to 1967 legislative election.

In May 1968 widespread student riots and strikes broke out in France. The PCF initially supported the general strike but opposed the revolutionary student movement, which was dominated by Trotskyists, Maoists and anarchists, and the so-called "new social movements" (including environmentalists, gay movements, prisoners' movement — see Michel Foucault, etc.) At the end of May 1968, the PCF sided with de Gaulle, who was menacing the use of the army, and called for the end of the strike. The PCF also alienated many on the left by supporting the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

Nevertheless, the PCF benefited from the left-wing mood of the period, and from the collapse of the socialists. Because of Waldeck Rochet's ill health, Jacques Duclos was the candidate at the 1969 presidential election. Duclos polled 21% of the vote, completely eclipsing the SFIO whom, represented by Gaston Defferre, came in third in the first round. For the second round, the PCF refused to distinguish between Gaullist Georges Pompidou and Centrist Alain Poher, considering that was "six of one and half a dozen of the other" (in French: blanc bonnet ou bonnet blanc).

In 1970, Roger Garaudy, a member of the Central Committee of the PCF from 1945 on, was expelled from the party for his revisionist tendencies, being criticised for his attempt to reconcile Marxism with Roman Catholicism. Starting in 1982, Garaudy emerged as a major Holocaust denier and was effectively condemned in 1998.

In 1972 Waldeck Rochet was succeeded by Georges Marchais, who had effectively controlled the party since 1970. Marchais began a moderate liberalisation of the party's policies and internal life, although dissident members, particularly intellectuals, continued to be expelled. The PCF entered an alliance with Mitterrand's new Socialist Party (PS). They signed a Common Programme in view to the 1973 legislative election. The difference between the two parties decreased: the PCF had taken 21.5% of the vote as against 19% for the PS.[7]

Nominally the French communists supported Mitterrand's candidacy in 1974 presidential election, but the Soviet ambassador to Paris and the director of L'Humanité did not hide their satisfaction with Mitterrand's defeat. According to Jean Lacouture, Raymond Aron and François Mitterrand himself, the Soviet government and the French communist leaders had done everything in order to prevent Mitterrand from being elected: they regarded him as too anti-communist and too skillful in his strategy of rebalancing the Left on account of PCF.

During Mitterrand's term as PS first secretary, the socialists re-emerged as the principal party of the left. Indeed, Marchais asked to update the Common Programme, but the negotiations failed. The PS accused Marchais of being responsible for the division of the left and of its defeat at the 1978 legislative election. For the first time since 1936, the PCF lost its place as "first left-wing party", which the Socialists assumed.

At the 22nd party congress in February 1976, reeling from fallout caused by the publication of The Gulag Archipelago, the PCF abandoned the dictatorship of the proletariat and references to it;[8] it began to follow a line closer to that of the Italian Communist Party's eurocommunism. However, this was only a relative change of direction, as the PCF globally remained loyal to Moscow, and in 1979, Georges Marchais supported the invasion of Afghanistan. Its assessment of the Soviet and East-European Communist governments was "positive overall".

Marchais was a candidate in the 1981 presidential election. During the campaign, he criticized the "turn to the right" of the PS. But some Communist voters, wanting the left-wing union in order to win after 23 years in opposition, chose Mitterrand. The PS leader obtained 25% against 15% for Marchais. For the second round, the PCF called on its supporters to vote for Mitterrand, who was elected President of France.

Decline

Under Mitterrand the PCF held ministerial office for the first time since 1947, but this had the effect of locking the PCF into Mitterrand's reformist agenda, and the PCF's more moderate supporters drained away to the PS.

When PCF ministers resigned in 1984 to protest Mitterrand's change of economic policies, the party's electoral decline accelerated. André Lajoinie obtained only 6.7% in the 1988 presidential election. From 1988 to 1993, the PCF supported the Socialist governments at various times, depending on the issues.

The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 led to a crisis in the PCF, but it did not follow the example of some other European communist parties by dissolving itself or changing its name. In 1994 Marchais retired and was succeeded by Robert Hue. Under Hue the party embarked on a process called la mutation. La mutation, which included the thorough reorganization of party structure and move away from Leninist dogmas, was intended to revitalize the stagnant left and attract non-affiliated leftists to join the party. However, it failed to stop the decline of the party. Under Lionel Jospin, the PCF again held ministerial offices from 1997 to 2002 (Jean-Claude Gayssot as Minister of Transportation, etc.). The party became riddled with internal conflict, as many sectors opposed la mutation and the policy of co-governing with the Socialists.

In the first round of the 2002 presidential elections, Hue received just 3.4% of the vote. For the first time, the PCF candidate obtained fewer votes than the Trotskyist candidates (Arlette Laguiller and Olivier Besancenot). In the 2002 legislative elections, the PCF came in fourth, polling 4.8% of the vote (the same as the center-right Union for French Democracy, UDF) and won 21 seats. Chirac's UMP came in first, followed by the Socialist Party, the National Front, UDF, PCF, the Greens, and then the Trotskyist Revolutionary Communist League (LCR) and Lutte Ouvrière. Eventually Robert Hue had to resign, and in 2002 Marie-George Buffet took over the leadership of the party. Under Buffet the party embarked on a process of reconstruction, reversing some of the moves made during la mutation.

In 2005, during the referendum campaign on the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe (TCE), the PCF supported the 'No' side alongside other left-wing groups, much of the Socialist Party, the Greens, and right wing eurosceptics. The victory of the 'No' vote, along with a campaign against the Bolkestein directive, earned the party some positive publicity.

In 2005, a labour conflict at the SNCM in Marseille, followed by a 4 October 2005 demonstration against the New Employment Contract (CNE) marked the opposition to Dominique de Villepin's right-wing government, who shared his authority with Nicolas Sarkozy as Ministry of Interior, leader of the UMP right-wing party and already then a probable 2007 presidential candidate. Marie-George Buffet also heavily criticized the government's response to the riots in autumn, speaking of a deliberate "strategy of tension" employed by Sarkozy who called youth from the housing projects "scum" (racaille) which needed to be cleaned up with a "Kärcher" high pressure hose. While most of the Socialist deputies voted for the declaration of a state of emergency during the riots, which lasted until January 2006, the PCF, along with the Greens, opposed it.

In 2006, the PCF and other left-wing groups supported protests against the First Employment Contract, which finally forced president Chirac to scrap plans for the bill, aimed at creating a more flexible labour law.

During the run-up to the first round of the 2007 presidential election, Buffet hoped that her candidacy would be supported by the left-wing groups who had participated in the "No" campaign in the referendum on the EU constitution. This support was not forthcoming and she scored only 1.94%, even less than Robert Hue's 3.4% in the previous presidential election. The PCF's score was low even in its traditional strongholds such as the "red belt" around Paris. The disastrously low vote means that the PCF has not met the 5% threshold for reimbursement of its campaign expenses, and could portend a similarly low vote in the next general election. However, the party had prepared for this eventuality, and thus kept its expenses low for the presidential campaign. However, its very low score at the subsequent legislative elections did weigh a lot on its budget [9]. One possible reason for this particularly low vote is that some PCF supporters may have voted tactically for Ségolène Royal so as to be sure that a candidate from the left would be present in the second round runoff[citation needed]. Another factor seems to have been competition from the young and charismatic candidate, Olivier Besancenot, of the LCR (Revolutionary Communist League)[citation needed].

In the legislative election of 2007, the PCF gained 15 seats, five below the minimum required to form a parliamentary group by itself. This was the first time the PCF had ever fallen below that threshold in the history of the Fifth Republic. The PCF subsequently allied itself with the Greens and other left-wing MP's to be able to form a parliamentary group to the left of the Socialist Party, called Gauche démocrate et républicaine (Democratic and Republican Left). Although the PCF and the Greens agree on a number of issues, especially on economic and social policies (consensus on the necessity to support lower classes, right of foreigners to vote at municipal elections, regularization of aliens, etc.), but also on others themes (by contrast with the Socialist Party, both refused to vote for the state of emergency during the 2005 civil unrest, they also distinguished themselves on a number of other issues, including the use of nuclear energy.

In the municipal elections of 2008, the PCF fared better than expected[10]. It won Dieppe, Saint Claude, Firminy and Vierzon as well as other smaller towns and kept most of its large towns, such as Arles, Bagneux, Bobigny, Champigny-sur-Marne, Echirolles, Fontenay-sous-Bois, Gardanne, Gennevilliers, Givors, Malakoff, Martigues, Nanterre, Stains, Venissieux. However, the PCF lost some key communes on the second round, such as Montreuil, Aubervilliers and particularly Calais, where an UMP candidate ousted the PCF after 37 years.

In the 2009 European Parliament election, the party will run as part of the Left Front with the Convention for a Progressive Alternative and the Left Party.

Currently, the PCF retains some strength in suburban Paris, in the industrial areas around Lille, in some departments of central France, such as Allier and Cher and in some cities of the south, such as Marseille and nearby towns, as well as the working-class communes surrounding Lyon, Saint-Étienne, Alès and Grenoble [11].

Election results

The share of the French national vote won by the PCF in its history:

- 1924: 9.84%

- 1928: 11.26%

- 1932: 8.32%

- 1936: 15.26%

- 1945: 26.23%

- June 1946: 25.98%

- November 1946: 28.3%

- 1951: 26.27%

- 1956: 25.36%

- 1958: 18.9%

- 1962: 21.8%

- 1967: 22.5%

- 1968: 20%

- 1969 (presidential election): 21.27%

- 1973 (legislative election): 21.3%

- 1978 (legislative): 20.5%

- 1981 (presidential): 15.35%

- 1981 (legislative): 16.17%

- 1986 (legislative): 9.78%

- 1988 (presidential): 6.76% (Pierre Juquin, a dissident Communist, received 2.10%)

- 1988: 11.32%

- 1993 (legislative): 9.30%

- 1995 (presidential): 8.66%

- 1997 (legislative): 9.92%

- 2002 (presidential): 3.37%

- 2002 (legislative): 4.82%

- 2007 (presidential): 1.93%

- 2007 (legislative): 4.29%

Publications

The PCF publishes the following:

- Communistes (Communists)

- Info Hebdo (Weekly News)

- Economie et Politique (Economics and Politics)

Traditionally, it was also the owner of the French daily L'Humanité (Humanity), founded by Jean Jaurès. Although the newspaper is now independent, it remains close to the PCF. The paper is sustained by the annual Fête de L'Humanité festival, held in La Courneuve, a working class suburb of Paris.

During the 1970s, the PCF registered success with the children's magazine it founded, Pif gadget.

References

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2007) |

- ^ Gilberg, Trond. Coalition Strategies Of Marxist Parties. Durham: Duke University Press, 1989. p. 256

- ^ Thomas, Martin. The French empire between the wars : imperialism, politics and society. New York: Manchester University Press, 2005. p. 289

- ^ Julian Jackson, The Fall of France: The Nazi Invasion of 1940

- ^ Matt Perry, Prisoners of Want

- ^ Gilberg, Trond. Coalition Strategies Of Marxist Parties. Durham: Duke University Press, 1989. p. 265

- ^ Benjamin, Roger W.; Kautsky, John H.. Communism and Economic Development, in The American Political Science Review, Vol. 62, No. 1. (Mar., 1968), pp. 122.

- ^ Gildea, Robert. France Since 1945, p. 213. Oxford University Press, London, 1996.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ Cash-strapped Communists hawk treasures, The Telegraph, 2007-06-10, accessed on 2007-06-11

- ^ www.psa.ac.uk/journals/pdf/5/2008/Cole2.pdf

- ^ http://www.atlaspol.com/

See also

- List of foreign delegations at 24th PCF Congress (1982)

- Place du Colonel Fabien

- Louis Althusser's Reading Capital (1965)

- MRAP anti-racist NGO, created in 1941