Salton Sea

| Salton Sea | |

|---|---|

| Location | Colorado Desert Imperial / Riverside counties, California, USA |

| Coordinates | 33°19′59″N 115°50′03″W / 33.333°N 115.8342°W |

| Type | Endorheic rift lake |

| Primary inflows | Alamo River New River Whitewater River |

| Catchment area | 8,360 square miles (21,700 km2) |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Surface area | 974 km2 (376 sq mi) |

| Max. depth | 16 m (52 ft) |

| Water volume | 9.25 km3 (7,500,000 acre⋅ft) |

| Surface elevation | -69 m (226 ft) (below sea level) |

| Settlements | Bombay Beach, Desert Beach, Desert Shores, Salton City, Salton Sea Beach, North Shore |

| References | U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Salton Sea |

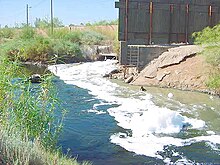

The Salton Sea is a saline, endorheic rift lake located directly on the San Andreas Fault predominantly in California's Imperial Valley. The lake occupies the lowest elevations of the Salton Sink in the Colorado Desert of Imperial and Riverside Counties in Southern California. Like Death Valley, it is below sea level; currently, its surface is 226 ft (69 m) below sea level. The deepest area of the sea is 5 ft (1.5 m) higher than the lowest point of Death Valley. The sea is fed by the New, Whitewater, and Alamo rivers, as well as agricultural runoff drainage systems and creeks.

The lake covers about 376 sq mi (970 km2), 241,000+/- acres, making it the largest in California. While it varies in dimensions and area with changes in agricultural runoff and rain, it averages 15 mi (24 km) by 35 mi (56 km), with a maximum depth of 52 ft (16 m), giving a total volume of about 7,500,000 acre⋅ft (9.3 km3), and annual inflows averaging 1,360,000 acre⋅ft (1.68 km3). The lake's salinity, about 44 g/L, is greater than the waters of the Pacific Ocean (35 g/L), but less than that of the Great Salt Lake; the concentration is increasing by about 1 percent annually.[1]

The airspace above the lake consists mostly of the Kane West and Kane East MOAs, although a small section above the northern reaches is Class E and G. Much of the airspace to the southwest, south, and east is restricted. The Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge is identified on VFR sectional charts (used by pilots to navigate in fair weather) as occupying most of the southeast quarter of the lake.

History

It is estimated that for 3 million years, at least through all the years of the Pleistocene glacial age, the Colorado River worked to build its delta in the southern region of the Imperial Valley. Eventually, the delta had reached the western shore of the Gulf of California (the Sea of Cortez/Cortés) creating a massive dam which excluded the Salton Sea from the northern reaches of the Gulf.[2]

As a result, the Salton Sink or Salton Basin has long been alternately a fresh water lake and a dry desert basin, depending on random river flows and the balance between inflow and evaporative loss. A lake would exist only when it was replenished by the river and rainfall, a cycle that repeated itself countless times over hundreds of thousands of years - most recently when the lake was recreated in 1905.[3]

There is evidence that the basin was occupied periodically by multiple lakes. Wave-cut shorelines at various elevations are still preserved on the hillsides of the east and west margins of the present lake, the Salton Sea, showing that the basin was occupied intermittently as recently as a few hundred years ago. The last of the Pleistocene lakes to occupy the basin was Lake Cahuilla, also periodically identified on older maps as Lake LeConte, and the Blake Sea, after American professor and geologist William Phipps Blake.

Once part of a vast inland sea that covered a large area of Southern California, the endorheic Salton Sink was the site of a major salt mining operation.[4] Throughout the Spanish period of California's history the area was referred to as the "Colorado Desert" after the Rio Colorado (Colorado River). In the 1853/55 railroad survey, it was called "The Valley of the Ancient Lake". On several old maps from the Library of Congress, it has been found labeled "Cahuilla Valley" (after the local Indian tribe) and "Cabazon Valley" (after a local Indian chief - Chief Cabazon). "Salt Creek" first appeared on a map in 1867 and "Salton Station" is on a railroad map from 1900, although this place had been there as a rail stop since the late 1870s.[5]

Creation of the current Salton Sea

The creation of the Salton Sea of today started in 1905, when heavy rainfall and snowmelt caused the Colorado River to swell, overrunning a set of headgates for the Alamo Canal. The resulting flood poured down the canal and breached an Imperial Valley dike, eroding two watercourses, the New River in the west, and the Alamo River in the east, each about 60 miles (97 km) long.[6] Over a period of approximately two years these two newly created rivers sporadically carried the entire volume of the Colorado River into the Salton Sink.[7]

The Southern Pacific Railroad attempted to stop the flooding by dumping earth into the canal's headgates area, but the effort was not fast enough, and as the river eroded deeper and deeper into the dry desert sand of the Imperial Valley, a massive waterfall was created that started to cut rapidly upstream along the path of the Alamo Canal that now was occupied by the Colorado. This waterfall was initially 15 feet (4.6 m) high but grew to a height of 80 feet (24 m) before the flow through the breach was finally stopped. It was originally feared that the waterfall would recede upstream to the true main path of the Colorado, attaining a height of up to 100 to 300 feet (30 to 91 m), from where it would be practically impossible to fix the problem. As the basin filled, the town of Salton, a Southern Pacific Railroad siding and Torres-Martinez Indian land were submerged. The sudden influx of water and the lack of any drainage from the basin resulted in the formation of the Salton Sea.[8][9]

The continuing intermittent flooding of the Imperial Valley from the Colorado River led to the idea of the need for a dam on the Colorado River for flood control. Eventually, the federal government sponsored survey parties in 1922 that explored the Colorado River for a dam site, ultimately leading to the construction of Hoover Dam in Black Canyon, which was constructed beginning in 1929 and completed in 1935. The dam effectively put an end to the flooding episodes in the Imperial Valley.

Subsequent evolution of the Sea

In the 1920s, the Salton Sea developed into a tourist attraction, because of its water recreation, and waterfowl attracted to the area. The Salton Sea remains a major resource for migrating and wading birds.[citation needed]

The Salton Sea has had some success as a resort area, with Salton City, Salton Sea Beach, and Desert Shores on the western shore and Desert Beach, North Shore, and Bombay Beach built on the eastern shore in the 1950s. The town of Niland is located 2 miles (3 km) southeast of the Sea as well. The evidence of geothermal activity is also visible. There are mud pots and mud volcanoes on the eastern side of the Salton Sea.[10]

Avian population

The Salton Sea has been termed a "crown jewel of avian biodiversity" (Dr. Milt Friend, Salton Sea Science Office). Over 400 species have been documented at the Salton Sea. The Salton Sea supports 30% of the remaining population of the American white pelican.[11] The Salton Sea is also a major resting stop on the Pacific Flyway. On 18 November 2006, a Ross's gull, a high Arctic bird, was sighted and photographed there.[12]

Environmental decline

The lack of an outflow means that the Salton Sea is a system of accelerated change. Variations in agricultural runoff cause fluctuations in water level (and flooding of surrounding communities in the 1950s and 1960s), and the relatively high salinity of the inflow feeding the Sea has resulted in ever increasing salinity. By the 1960s it was apparent that the salinity of the Salton Sea was rising, jeopardizing some of the species in it. The Salton Sea currently has a salinity exceeding 4.0% w/v (saltier than seawater) and many species of fish are no longer able to survive. It is believed that once the salinity surpasses 4.4% w/v, only the tilapia will survive. Fertilizer runoffs combined with the increasing salinity have resulted in large algal blooms and elevated bacteria levels.[13]

Remediation efforts

Past efforts and proposals for a sea level canal

Alternatives for "saving" the Salton Sea have been evaluated since 1955. Early concepts included costly "pipe in/pipe out" options, which would import lower salinity seawater from the Gulf of California or Pacific Ocean and export higher salinity Salton Sea water; evaporation ponds that would serve as a salt sink, and large dam structures that would partition the sea into a marine lake portion and a brine salt sink portion. Others advocate building a sea-level canal to the Salton Sea from the Gulf of California. Given that the Sea is over 200 feet (60m) below sea level, a sea level canal would allow thousands of tons of lower-salinity sea water to flow into the Sea without costly pumping or pipelines. Such a canal could be built large enough for recreational use and ocean-going vessels. A sea-level canal would promote dual purposes, as both an inland port for Southern California and a recreational/environmental asset along its course for humans and wildlife in Mexico and the U.S. A sea-level canal would also likely provide a way to regulate the shoreline of the Sea in a predictable manner. However, without a means to export salt, even this approach would eventually leave the sea with ever-increasing salinity levels.

Much of the current interest in the sea was sparked in the 1990s by the late Congressman Sonny Bono.[14] His widow, Mary Bono Mack, was elected to fill his seat and has continued interest in the Salton Sea, as has Representative Jerry Lewis of Redlands.[14] In 1998, the Sonny Bono Salton Sea Restoration Project was named for the politician.[14]

In the late 1990s, the Salton Sea Authority, a local joint powers agency, and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation began efforts to evaluate and develop an alternative to save the Salton Sea. A draft Environmental Impact Report/Environmental Impact Statement, which did not specify a preferred alternative, was released for public review in 2000. Since that time, the Salton Sea Authority has developed a preferred concept [15] that involves the construction of a large dam that would impound water to create a marine sea in the northern and southern parts of the sea and along the western edge. The plan has been subject to some criticism for failing to address ecosystem needs, and for engineering practicality concerns such as local faulting, potentially devastating to such a plan.

Criticisms of the preferred plan issued by the Salton Sea Authority include:[citation needed]

- Construction failure when identified 200 feet (60m) of sediments fail to hold up the rock structures placed on top of them

- Geological catastrophe when a major earthquake hits the nearby San Andreas Fault (feet (meters) away from the east end of the dike)

- Physical catastrophic failure as water is depleted from the south pond and water pressure pushes across the north pond against the soft sedimentary underlayment

- Possible catastrophic failure by water blowing under the dike as water from the higher north pond etches its way under the dike

- Massive alkali storms blowing across the area destroying crops from the south basin[16] exposing dried salt sediments, resulting in crop damage and increased respiratory problems.

Many other concepts have been proposed,[17] including piping water from the Sea to a wetland in Mexico, Laguna Salada, as a means of salt export, and one by Aqua Genesis Ltd to bring in sea water from the Gulf of California, desalinate it at the Sea using available geothermal heat, and selling the water to pay for the plan. This concept would involve the construction of over 20 miles (30 km) of pipes and tunneling, and, with the increasing demand for water at the coastline, would provide an additional 1,000,000 acre feet (1.2 km³) of water to Southern California coastal cities each year.[18]

Current state restoration process

The California State Legislature, by legislation enacted in 2003 and 2004, directed the Secretary of the California Resources Agency to prepare a restoration plan for the Salton Sea ecosystem, and an accompanying Environmental Impact Report.[19] As part of this effort, which is based on State legislation enacted in 2003 and 2004, the Secretary for Resources has established an Advisory Committee to provide recommendations to assist in the preparation of the Ecosystem Restoration Plan, including consultation throughout all stages of the alternative selection process. The California Department of Water Resources and California Department of Fish and Game are leading the effort to develop a preferred alternative for the restoration of the Salton Sea ecosystem and the protection of wildlife dependent on that ecosystem.

On January 24, 2008, the California Legislative Analysis Office released a report entitled "Saving the Salton Sea."[19] The preferred alternative outlined within this draft plan calls for spending a total of almost $9 billion over 25 years and proposes a smaller but more manageable Salton Sea. The amount of water available for use by humans and wildlife would be reduced by 60 percent from 365 square miles (945 square kilometers) to about 147 square miles (381 square kilometers). Fifty-two miles (84 km) of barrier and perimeter dikes - constructed most likely out of boulders, gravel and stone columns - would be erected along with earthen berms to corral the water into a horseshoe shape along northern shoreline of the sea from San Felipe Creek on the west shore to Bombay Beach on the east shore. The central portion of the sea would be allowed to almost completely evaporate and would serve as a brine sink, while the southern portion of the sea would be constructed into a saline habitat complex. If approved, construction on this project is slated to begin in 2011 and would be completed by 2035.

Media attention

The documentary, Plagues & Pleasures on the Salton Sea, narrated by John Waters, covers the first 100 years of the Salton Sea along with the environmental issues and offbeat residents of the region.

The episode "Future Conditional" (#302) from the series Journey to Planet Earth (narrated by Matt Damon) talks about the plight of the sea, and if nothing is done, a repeat of the fate of the Aral Sea will occur.[20]

The episode "Holliday Hell" (#206) from the series Life After People uses the Salton Sea as an example of how a resort town like Palm Springs would decay if no humans were there to maintain it. [21]

On March 24, 2009, a Los Angeles Times article reported a series of earthquakes in the Salton Sea. The article also quoted prominent geophysicists and seismologists who discuss the potential for these small quakes to spawn a massive earthquake on the San Andreas Fault.[22]

See also

Notes

- ^ Khaled M. Bali (27 March 2009). "Salton Sea Salinity and Saline Water". UC Davis, Cooperative Extension Imperial County. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ Alles, David L. (2007-08-06). "Geology of the Salton Trough" (PDF). Biology Department. Western Washington University. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ^ Eugene Singer. "Ancient Lake Cahuilla - Geology of the Imperial Valley". Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- ^ The Salton Sea – Its Beginnings. Accessed 2010-06-14

- ^ History of the Salton Sea, Accessed 2010-06-14

- ^ Detailed maps, and a film of the breach (and subsequent re-damming) are in Plagues & Pleasures on the Salton Sea, a 2006 documentary

- ^ Laflin, Pat. "THE SALTON SEA CALIFORNIA'S OVERLOOKED TREASURE" (PDF). Coachella Valley Historical Society. pp. 21–26. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ Kennan, George (1917). The Salton Sea: An Account of Harriman's Fight With The Colorado River. New York: The MacMillan Company.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|title= - ^ Larkin, Edgar L. (1907). "A Thousand Men Against A River: The Engineering Victory Over The Colorado River And The Salton Sea". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XIII: 8606–8610.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|title=|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lynch, David K.; Hudnut, Kenneth W. (2008). "The Wister Mud Pot Lineament: Southeastward Extension or Abandoned Strand of the San Andreas Fault?". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 98 (4): 1720–1729. doi:10.1785/0120070252.

- ^ http://ca.audubon.org/Salton_Sea_Avifauna.pdf

- ^ http://www.southwestbirders.com/rogu_ss111806.htm

- ^ NASA page: "Algal bloom in the Salton Sea, California".

- ^ a b c CNN article: "Salton Sea rescue to be named for Sonny Bono".

- ^ State of California

- ^ http://www.saltonsea.ca.gov/Concept7-20-2005SouthDetail8x11.pdf

- ^ http://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/saltnsea/ssbro.html#steps

- ^ http://www.sandiegoreader.com/news/2004/feb/26/inventor-tackles-salton-sea-disaster/ San Diego Union Times: Ronald Newcomb's Salton Sea proposal

- ^ a b Salton Sea Ecosystem Restoration Program

- ^ "Future Conditional" (#302) - Journey to Planet Earth

- ^ "Life after people" (#206) - Life after people

- ^ Chong, Jia-Rui (2009-03-24). "At the Salton Sea, a warning sign of the Big One?". LA Times. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

References

- Metzler, Chris and Springer, Jeff - "Plagues & Pleasures on the Salton Sea" Tilapia Film, [2006] - Thorough history of the first 100 years at the Salton Sea and the prospects for the future

- Stevens, Joseph E. Hoover Dam. University of Oklahoma Press, 1988. (Extensive details on the Salton Sea disaster.)

Further reading

- Setmire, James G., et al. (1993). Detailed study of water quality, bottom sediment, and biota associated with irrigation drainage in the Salton Sea area, California, 1988–90 [Water-Resources Investigations Report 93-4014]. Sacramento, Calif.: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- Setmire, James G., Wolfe, John C., and Stroud, Richard K. (1990). Reconnaissance investigation of water quality, bottom sediment, and biota associated with irrigation drainage in the Salton Sea area, California, 1986–87 [Water-Resources Investigations Report 89-4102]. Sacramento, Calif.: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- Sperry, Robert L. (Winter 1975). "When the Imperial Valley Fought for its Life". Journal of San Diego History. 21 (1).

- Greenfield, Steven (Winter 2006). "A Lake by Mistake". Invention & Technology. 21 (3).

External links

- Salton Sea Authority

- Salton Basin overview

- Salton Sea data and other resources

- US Bureau of Reclamation's Salton Sea Restoration Project Office

- The Salton Sea - A Photo Essay by Scott London

- National Geographic photos of the Salton Sea

- Calexico New River Committee, New River Tributary

- The Salton Sea: an account of Harriman's fight with the Colorado River

- Disasters in California

- Dry areas below sea level

- Engineering failures

- Environment of California

- Environmental disasters in the United States

- Geography of the Colorado Desert

- Landforms of Imperial County, California

- Important Bird Areas of the United States

- Lakes of Riverside County, California

- Saline lakes

- Endorheic lakes

- Shrunken lakes

- Visitor attractions in Imperial County, California