Greenpeace

| Founded | 1971 Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada |

|---|---|

| Type | Non-governmental organization |

| Focus | Environmentalism, peace |

| Location |

|

Area served | Worldwide |

| Method | Direct action, lobbying, research, innovation |

Members | 2.86 million (2008) |

Key people |

|

Revenue | €196.6 million (2008) |

| Website | www.GreenPeace.org www.GreenPeace.mobi |

Greenpeace is a non-governmental environmental organization[1] with offices in over forty countries and with an international coordinating body in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.[2] Greenpeace states its goal is to "ensure the ability of the Earth to nurture life in all its diversity"[3] and focuses its campaigning on world wide issues such as global warming, deforestation, overfishing, commercial whaling and anti-nuclear issues. Greenpeace uses direct action, lobbying and research to achieve its goals. The global organization does not accept funding from governments, corporations or political parties, relying on more than 2.8 million individual supporters and foundation grants.[4][5] Greenpeace is a founding member of the INGO Accountability Charter; an international non-governmental organization that intends to foster accountability and transparency of non-governmental organizations.

Greenpeace evolved from the peace movement and anti-nuclear protests in Vancouver, British Columbia, in the early 1970s. On September 15, 1971, the newly founded Don't Make a Wave Committee sent a chartered ship, Phyllis Cormack, renamed Greenpeace for the protest, from Vancouver to oppose United States testing of nuclear devices in Amchitka, Alaska. The Don't Make a Wave Committee subsequently adopted the name Greenpeace.[6]

In a few years, Greenpeace spread to several countries and started to campaign on other environmental issues such as commercial whaling and toxic waste. In the late 1970s, the different regional Greenpeace groups formed Greenpeace International to oversee the goals and operations of the regional organizations globally.[7] Greenpeace received international attention during the 1980s when the French intelligence agency bombed the Rainbow Warrior in Auckland's Waitemata Harbour, one of the most well-known vessels operated by Greenpeace, killing one individual.[8] In the following years, Greenpeace evolved into one of the largest environmental organizations in the world.[9][10]

Greenpeace is known for its direct actions[11][12] and has been described as the most visible environmental organization in the world.[13][14] Greenpeace has raised environmental issues to public knowledge,[15][16][17] and influenced both the private and the public sector.[18][19] Greenpeace has also been a source of controversy;[20] its motives and methods have received criticism[21][22] and the organization's direct actions have sparked legal actions against Greenpeace activists.[23][24]

History

Origins

In the late 1960s, the U.S. had plans for an underground nuclear weapon test in the tectonically unstable island of Amchitka in Alaska. Because of the 1964 Alaska earthquake, the plans raised some concerns of the test triggering earthquakes and causing a tsunami. Anti-nuclear activists protested against the test on the border of the U.S. and Canada with signs reading "Don't Make A Wave. It's Your Fault If Our Fault Goes". The protests did not stop the U.S. from detonating the bomb.[25]

While no earthquake or tsunami followed the test, the opposition grew when the U.S. announced they would detonate a bomb five times more powerful than the first one. Among the opposers were Jim Bohlen, a veteran who had served the U.S. Navy and Irving and Dorothy Stowe, a Jewish couple, who had recently become Quakers. As members of the Sierra Club Canada, they were frustrated by the lack of action by the organization.[25] From Irving Stowe, Jim Bohlen learned of a form of passive resistance, "bearing witness", where objectionable activity is protested simply by mere presence.[25] Jim Bohlen's wife Marie came up with the idea to sail to Amchitka, inspired by the anti-nuclear voyages of Albert Bigelow in 1958. The idea ended up in the press and was linked to The Sierra Club.[25] The Sierra Club did not like this connection and in 1970 The Don't Make a Wave Committee was established for the protest. Early meetings were held in the home of Robert and Bobbi Hunter in Vancouver's Shaughnessy neighbourhood. Subsequently the Stowe home at 2775 Courtenay St. became the HQ.[26] The first office was opened in a back-room, storefront on Cypress and Bwy SE corner in Vancouver's Kitsilano, (Vancouver) before moving to West 4th at Maple (see below).[27]

There is some debate as to who are the actual founders of The Don't Make a Wave Committee. Researcher Vanessa Timmer has referred the early members as "an unlikely group of loosely organized protestors".[28] According to the current Greenpeace web page, the founders were Dorothy and Irving Stowe, Marie and Jim Bohlen, Ben and Dorothy Metcalfe, and Robert Hunter.[29] The book The Greenpeace Story states that the founders were Irving Stowe, Jim Bohlen and Paul Cote, a law student and peace activist.[25] An interview with Dorothy Stowe, Dorothy Metcalfe, Jim Bohlen and Robert Hunter identifies the founders as Paul Cote, Irving and Dorothy Stowe and Jim and Marie Bohlen.[30] Paul Watson, who also participated in the anti-nuclear protests, maintains that he also was one of the founders.[31] Another early member, Patrick Moore also has stated that he was one of the founders.[32] Greenpeace used to list Moore among "founders and first members" of The Don't Make a Wave Committee but has later stated that while Moore was a significant early member, he was not a founder.[30][33] According to Moore's own letter he applied to the already existing organization in March 1971.[34]

Irving Stowe arranged a benefit concert (supported by Joan Baez) that took place on October 16, 1970 at the Pacific Coliseum in Vancouver. The concert created the financial basis for the first Greenpeace campaign.[35] Amchitka, the 1970 concert that launched Greenpeace has been published by Greenpeace in November 2009 on CD and is also available as mp3 download via the Amchitka concert website. Using the money raised with the concert, the Don't Make a Wave Committee chartered a ship, the Phyllis Cormack owned and sailed by John Cormack. The ship was renamed Greenpeace for the protest after a term coined by activist Bill Darnell.[25]

In the fall of 1971 the ship sailed towards Amchitka and faced the U.S. Coast Guard ship Confidence[25] which forced the activists to turn back. Because of this and the increasingly bad weather the crew decided to return to Canada only to find out that the news about their journey and reported support from the crew of the Confidence had generated sympathy for their protest.[25] After this Greenpeace tried to navigate to the test site with other vessels, until the U.S. detonated the bomb.[25] The nuclear test was criticized and the U.S. decided not to continue with their test plans at Amchitka.

In 1972, The Don't Make a Wave committee changed their official name to Greenpeace Foundation.[25] While the organization was founded under a different name in 1970 and was officially named Greenpeace in 1972, the organization itself dates its birth to the first protest of 1971.[36] Greenpeace also states that "there was no single founder, and the name, idea, spirit, tactics, and internationalism of the organization all can be said to have separate lineages".[29]

As Rex Weyler put it in his chronology, Greenpeace, in 1969, Irving and Dorothy Stowe's "quiet home on Courtenay Street would soon become a hub of monumental, global significance". Some of the first Greenpeace meetings were held there, and it served as the first office of the Greenpeace Foundation.

After the office in the Stowe home, (and after the first concert fund-raiser) Greenpeace functions moved to other private homes before settling, in the fall of 1974, in a small office shared with the SPEC environmental group, at 2007 W. 4th Avenue, at Maple Street, across from the Bimini neighbourhood pub. The address of this office has since been changed to 2009 W. 4th Avenue. The building still exists, and the office is up the stair at the “2009” door.

First campaigns after Amchitka

After the nuclear tests at Amchitka were over, Greenpeace moved its focus to the French atmospheric nuclear weapons testing at the Moruroa Atoll in French Polynesia. The young organization needed help for their protests and were contacted by David McTaggart, a former businessman living in New Zealand. In 1972 the yacht Vega, a 12.5-metre (41 ft) ketch owned by David McTaggart, was renamed Greenpeace III and sailed in an anti-nuclear protest into the exclusion zone at Moruroa to attempt to disrupt French nuclear testing. This voyage was sponsored and organized by the New Zealand branch of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.[37] The French Navy tried to stop the protest in several ways, including assaulting David McTaggart. McTaggart was supposedly beaten to the point that he lost sight in one of his eyes. Luckily, one of McTaggart's crew members photographed the incident and went public. After the assault was publicized, France announced it would stop the atmospheric nuclear tests.[25]

In the mid-1970s some Greenpeace members started an independent campaign, Project Ahab, against commercial whaling, since Irving Stowe was against Greenpeace focusing on other issues than nuclear weapons. After Irving Stowe died in 1975, Phyllis Cormack left from Vancouver to face Soviet whalers on the coast of California. Greenpeace activists disrupted the whaling by going between the harpoons and the whales, and the footage of the protests spread across the world. Later in the 1970s the organization widened its focus to include toxic waste and commercial seal hunting.[25]

Organizational development

Greenpeace evolved from a group of Canadian protesters in a sail boat, into a less conservative group of environmentalists who were more reflective of the counterculture and hippie youth movements of the 1960s and 1970s.[38] The social and cultural background from which Greenpeace emerged heralded a period of de-conditioning away from old world antecedents and sought to develop new codes of social, environmental and political behavior.[6][39] Historian Frank Zelko has commented that "unlike Friends of the Earth, for example, which sprung fully formed from the forehead of David Brower, Greenpeace developed in a more evolutionary manner."[7]

In the mid-1970s independent groups using the name Greenpeace started springing up world wide. By 1977 there were 15 to 20 Greenpeace groups around the world.[7] At the same time the Canadian Greenpeace office was heavily in debt. Disputes between offices over fund-raising and organizational direction split the global movement as the North American offices were reluctant to be under the authority of the Vancouver office and its president Patrick Moore.[7]

After the incidents of Moruroa, David McTaggart had moved to France to battle in court with the French state and helped to develop the cooperation of European Greenpeace groups.[25] David McTaggart lobbied the Canadian Greenpeace Foundation to accept a new structure which would bring the scattered Greenpeace offices under the auspices of a single global organization. The European Greenpeace paid the debt of the Canadian Greenpeace office and on October 14, 1979, Greenpeace International came into existence.[7][28] Under the new structure, the local offices would contribute a percentage of their income to the international organization, which would take responsibility for setting the overall direction of the movement with each regional office having one vote.[7] Some Greenpeace groups, namely London Greenpeace (dissolved in 2001) and the US-based Greenpeace Foundation (still operational) however decided to remain independent from Greenpeace International.[40][41]

Priorities and campaigns

On its official website, Greenpeace defines its mission as the following:

Greenpeace is an independent global campaigning organization that acts to change attitudes and behaviour, to protect and conserve the environment and to promote peace by:

- Catalysing an energy revolution to address the number one threat facing our planet: climate change.

- Defending our oceans by challenging wasteful and destructive fishing, and creating a global network of marine reserves.

- Protecting the world’s remaining ancient forests which are depended on by many animals, plants and people.

- Working for disarmament and peace by reducing dependence on finite resources and calling for the elimination of all nuclear weapons.

- Creating a toxin free future with safer alternatives to hazardous chemicals in today's products and manufacturing.

- Campaigning for sustainable agriculture by encouraging socially and ecologically responsible farming practices.

— Greenpeace International[42]

Climate and energy

Greenpeace was one of the first parties to formulate a sustainable development scenario for climate change mitigation, which it did in 1993.[43] According to sociologists Marc Mormont and Christine Dasnoy, Greenpeace played a significant role in raising public awareness of global warming in the 1990s.[44] The organization has also focused on CFCs, because of both their global warming potential and their effect on the ozone layer. Greenpeace was one of the leading participants advocating early phase-out of ozone depleting substances in the Montreal Protocol.[18] In the early 1990s, Greenpeace developed a CFC-free refrigerator technology, "Greenfreeze" for mass production together with the refrigerator industry.[18] United Nations Environment Programme awarded Greenpeace for "outstanding contributions to the protection of the Earth's ozone layer" in 1997.[45] In 2007 one third of the world's total production of refrigerators were based on Greenfreeze technology, with over 200 million units in use.[18]

Currently Greenpeace considers global warming to be the greatest environmental problem facing the Earth.[42] Greenpeace calls for global greenhouse gas emissions to peak in 2015 and to decrease as close to zero as possible by 2050. For this Greenpeace calls for the industrialized countries to cut their emissions at least 40% by 2020 (from 1990 levels) and to give substantial funding for developing countries to build a sustainable energy capacity, to adapt to the inevitable consequences of global warming, and to stop deforestation by 2020.[46] Together with EREC, Greenpeace has formulated a global energy scenario, "Energy [R]evolution", where 80% of the world's total energy is produced with renewables, and the emissions of the energy sector are decreased by over 80% of the 1990 levels by 2050.[47]

Using direct action, Greenpeace has protested several times against coal by occupying coal power plants and blocking coal shipments and mining operations, in places such as New Zealand,[48] Svalbard,[49] Australia,[50] and the United Kingdom.[51] Greenpeace is also critical of extracting petroleum from oil sands and has used direct action to block the oil sand operations at Athabasca, Canada.[52][53]

The Kingsnorth court case

In October 2007, six Greenpeace protesters were arrested for breaking in to the Kingsnorth power station, climbing the 200 metre smokestack, painting the name Gordon on the chimney, and causing an estimated £30,000 damage. At their subsequent trial they admitted trying to shut the station down, but argued that they were legally justified because they were trying to prevent climate change from causing greater damage to property elsewhere around the world. Evidence was heard from David Cameron's environment adviser Zac Goldsmith, climate scientist James E. Hansen and an Inuit leader from Greenland, all saying that climate change was already seriously affecting life around the world. The six activists were acquitted. It was the first case where preventing property damage caused by climate change has been used as part of a "lawful excuse" defence in court.[54] Both The Daily Telegraph and The Guardian described the acquittal as embarrassment to the Brown Ministry.[55][56] In December 2008 The New York Times listed the acquittal in its annual list of the most influential ideas of the year.[57]

"Go Beyond Oil"

As part of their stance on the subject re-newable energy, Greenpeace have launched the "Go Beyond Oil" campaign.[58] The campaign is focused on slowing, and eventually ending, the world's consumption of oil; with activist activities taking place against companies that pursue oil drilling as a venture. Much of the activities of the "Go Beyond Oil" campaign have been focused on drilling for oil in the Arctic and areas affected by the Deepwater Horizon disaster. The activities of Greenpeace in the arctic have mainly involved the Edinburgh-based oil and gas exploration company, Cairn Energy; and range from protests at the Cairn Energy's headquarters[59] to scalling their oil rigs in an attempt to halt the drilling process.[60]

The "Go Beyond Oil" campaign also involves applying political pressure on the governments who allow oil exploration in their territories; with the group stating that one of the key aims of the "Go Beyond Oil" campaign is to "work to expose the lengths the oil industry is willing to go to squeeze the last barrels out of the ground and put pressure on industry and governments to move beyond oil."[58]

Nuclear power

Greenpeace views nuclear power as a relatively minor industry with major problems, such as environmental damage and risks from uranium mining, nuclear weapons proliferation, and unresolved questions concerning nuclear waste. The organization argues that the potential of nuclear power to mitigate global warming is marginal, referring to the IEA energy scenario where an increase in world's nuclear capacity from 2608 TWh in 2007 to 9857 TWh by 2050 would cut global greenhouse gas emissions less than 5% and at require 32 nuclear reactor units of 1000MW capacity built per year until 2050. According to Greenpeace the slow construction times, construction delays, and hidden costs, all limit the mitigation potential of nuclear power. This makes the IEA scenario technically and financially unrealistic. They also argue that binding massive amounts of investments on nuclear energy would take funding away from more effective solutions.[47] Greenpeace views the construction of Olkiluoto 3 nuclear power plant in Finland as an example of the problems on building new nuclear power.[61]

Anti-nuclear advertisement

In 1994, Greenpeace published an anti-nuclear newspaper advert which included a claim that nuclear facilities Sellafield would kill 2000 people in the next 10 years, and an image of a hydrocephalus-affected child said to be a victim of nuclear weapons testing in Kazakhstan. Advertising Standards Authority viewed the claim concerning Sellafield unsubstantiated, and ASA did not accept that the child's condition was caused by radiation. This resulted in banning of the advert. Greenpeace did not admit fault, stating that a Kazakhstan doctor had said that the child's condition was due to nuclear testing. Adam Woolf from Greenpeace also stated that, "fifty years ago there were many experts who would be lined up and swear there was no link between smoking and bad health."[62] The UN has estimated that the nuclear weapon tests in Kazakhstan caused about 100,000 people to suffer over three generations.[63]

Press release blunder

In Philadelphia, in 2006, Greenpeace issued a press release that said "In the twenty years since the Chernobyl tragedy, the world's worst nuclear accident, there have been nearly [FILL IN ALARMIST AND ARMAGEDDONIST FACTOID HERE]," The final report warned of plane crashes and reactor meltdowns.[64] According to a Greenpeace spokesman, the memo was a joke that was accidentally released.[64]

EDF spying conviction

In 2011, a French court fined Électricité de France (EDF) €1.5m and jailed two senior employees for spying on Greenpeace, including hacking into Greenpeace's computer systems. Greenpeace was awarded €500,000 in damages.[65] Although EDF claimed that a security firm had only been employed to monitor Greenpeace, the court disagreed, jailing the head and deputy head of EDF's nuclear security operation for three years each. Two employees of the security firm, Kargus, run by a former member of France's secret services, received sentences of three and two years respectively.[66]

Forest campaign

Greenpeace aims at protecting intact primary forests from deforestation and degradation with the target of zero deforestation by 2020. Greenpeace has accused several corporations, such as Unilever,[67] Nike,[68] and McDonald's[69] of having links to the deforestation of the tropical rainforests, resulting in policy changes in several of the companies under criticism.[70][71][72] Greenpeace, together with other environmental NGOs, also campaigned for ten years for the EU to ban import of illegal timber. The EU decided to ban illegal timber on July 2010.[73] As deforestation contributes to global warming, Greenpeace has demanded that REDD (Reduced Emission from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) should be included in the climate treaty following the Kyoto treaty.[74]

Removal of ancient tree

In June 1995, Greenpeace took a trunk of a tree from the forests of the proposed national park of Koitajoki[75] in Ilomantsi, Finland and put it on display at exhibitions held in Austria and Germany. Greenpeace said in a press conference that the tree was originally from a logged area in the ancient forest which was supposed to be protected. Metsähallitus accused Greenpeace of theft and said that the tree was from a normal forest and had been left standing because of its old age. Metsähallitus also said that the tree had actually crashed over a road during a storm.[76] The incident received publicity in Finland, for example in the large newspapers Helsingin Sanomat and Ilta-Sanomat.[77] Greenpeace replied that the tree had fallen down because of the protective forest around it had been clearcut, and that they wanted to highlight the fate of old forests in general, not the fate of one particular tree.[78] Greenpeace also highlighted that Metsähallitus admitted the value of the forest afterwards as Metsähallitus currently refers to Koitajoki as a distinctive area because of its old growth forests.[79][80]

The 'Tokyo Two'

In 2008, two Greenpeace anti-whaling activists, Junichi Sato and Toru Suzuki, stole a case of whale meat from a delivery depot in Aomori prefecture, Japan. Their intention was to expose what they considered embezzlement of the meat collected during whale hunts. After a brief investigation of their allegations was ended, Sato and Suzuki were arrested and charged with theft and trespass.[81] Amnesty International said that the arrests and following raids on Greenpeace Japan office and homes of five of Greenpeace staff members were aimed at intimidating activists and non-governmental organizations.[82] They were convicted of theft and trespass in September 2010 by the Aomori district court.

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs)

Greenpeace has also supported the rejection of GM food from the US in famine-stricken Zambia as long as supplies of non-genetically engineered grain exist, stating that the US "should follow in the European Union's footsteps and allow aid recipients to choose their food aid, buying it locally if they wish. This practise can stimulate developing economies and creates more robust food security", adding that, "if Africans truly have no other alternative, the controversial GE maize should be milled so it can't be planted. It was this condition that allowed Zambia's neighbours Zimbabwe and Malawi to accept it."[83] After Zambia banned all GM food aid, the former agricultural minister of Zambia criticized, "how the various international NGOs that have spoken approvingly of the government's action will square the body count with their various consciences."[84] Concerning the decision of Zambia, Greenpeace has stated that, "it was obvious to us that if no non-GM aid was being offered then they should absolutely accept GM food aid. But the Zambian government decided to refuse the GM food. We offered our opinion to the Zambian government and, as many governments do, they disregarded our advice."[85]

Greenpeace on golden rice

Greenpeace opposes the planned use of golden rice, a variety of Oryza sativa rice produced through genetic engineering to biosynthesize beta-carotene, a precursor of pro-vitamin A in the edible parts of rice. According to Greenpeace, golden rice has not managed to do anything about malnutrition for 10 years during which alternative methods are already tackling malnutrition. The alternative proposed by Greenpeace is to discourage mono-cropping and to increase production of crops which are naturally nutrient-rich (containing other nutrients not found in golden rice in addition to beta-carotene). Greenpeace argues that resources should be spent on programs that are already working and helping to relieve malnutrition.[86] The Golden Rice Project acknowledges that, "While the most desirable option is a varied and sufficient diet, this goal is not always achievable, at least not in the short term."[87]

The renewal of these concerns coincided with the publication of a paper in the journal Nature about a version of golden rice with much higher levels of beta carotene.[88] This "golden rice 2" was developed and patented by Syngenta, which provoked Greenpeace to renew its allegation that the project is driven by profit motives.[89] Dr. C.S. Prakash, who is the director of the Center for Plant Biotechnology Research at Tuskegee University and is president of the AgBioWorld Foundation expressed the opinion that, "[c]ritics condemned biotechnology as something that is purely for profit, that is being pursued only in the West, and with no benefits to the consumer. Golden Rice proves them wrong, so they need to discredit it any way they can."[90]

Although Greenpeace had admitted efficiency to be its primary concern, as early as 2001,[91] statements from March and April 2005 also continued to express concern over human health and environmental safety[92][93] Greenpeace has opposed releasing golden rice to fields as opposed to farming in greenhouses, which according to golden rice developer Ingo Potrykus, limits the amount of material needed for human safety testing.[94]

Toxics

In July 2011, Greenpeace released its Dirty Laundry report accusing some of the world's top fashion and sportswear brands of releasing toxic waste into China's rivers.[95] The report profiles the problem of water pollution resulting from the release of toxic chemicals associated with the country's textile industry. Investigations focused on wastewater discharges from two facilities in China; one belonging to the Youngor Group located on the Yangtze River Delta and the other to Well Dyeing Factory Ltd. located on a tributary of the Pearl River Delta. Scientific analysis of samples from both facilities revealed the presence of hazardous and persistent hormone disruptor chemicals, including alkylphenols, perfluorinated compounds and perfluorooctane sulfonate.

The report goes on to assert that the Youngor Group and Well Dyeing Factory Ltd. - the two companies behind the facilities - have commercial relationships with a range of major clothing brands, including Abercrombie & Fitch, Adidas, Bauer Hockey, Calvin Klein, Converse (shoe company), Cortefiel, H&M, Lacoste, Li Ning (company), Metersbonwe Group, Nike, Phillips-Van Heusen and Puma AG.

Organizational structure

Governance

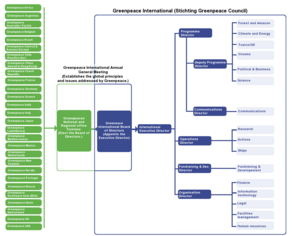

Greenpeace consists of Greenpeace International (officially Stichting Greenpeace Council) based in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and 28 regional offices operating in 45 countries.[96] The regional offices work largely autonomously under the supervision of Greenpeace International. The executive director of Greenpeace is elected by the board members of Greenpeace International. The current director of Greenpeace International is Kumi Naidoo and the current Chair of the Board is Lalita Ramdas.[97][98] Greenpeace has a staff of 2,400[5] and 15,000 volunteers globally.[99]

Each regional office is led by a regional executive director elected by the regional board of directors. The regional boards also appoint a trustee to The Greenpeace International Annual General Meeting, where the trustees elect or remove the board of directors of Greenpeace International. The role of the annual general meeting is also to discuss and decide the overall principles and strategically important issues for Greenpeace in collaboration with the trustees of regional offices and Greenpeace International board of directors.[100]

Funding

Greenpeace receives its funding from individual supporters and foundations.[3][4] Greenpeace screens all major donations in order to ensure it does not receive unwanted donations.[101] The organization does not accept money from governments, intergovernmental organizations, political parties or corporations in order to avoid their influence.[3][4][101] Donations from foundations which are funded by political parties or receive most of their funding from governments or intergovernmental organizations are rejected. Foundation donations are also rejected if the foundations attach unreasonable conditions, restrictions or constraints on Greenpeace activities or if the donation would compromise the independence and aims of Greenpeace.[101] Since in the mid-1990s the number of supporters started to decrease, Greenpeace pioneered the use of face-to-face fundraising where fundraisers actively seek new supporters at public places, subscribing them for a monthly direct debit donation.[102][103] In 2008, most of the €202.5 million received by the organization was donated by about 2.6 million regular supporters, mainly from Europe.[5]

In September 2003, the Public Interest Watch (PIW) complained to the Internal Revenue Service, claiming that Greenpeace USA tax returns were inaccurate and in violation of the law.[104] PIW charged that Greenpeace was using non-profit donations for advocacy instead of charity and educational purposes. PIW asked the IRS to investigate the complaint. Greenpeace rejected the accusations and challenged PIW to disclose its funders, a request rejected by then-Executive Director of PIW, Mike Hardiman, because PIW does not have 501c3 tax exempt status like Greenpeace does in the U.S.[105] The IRS conducted an extensive review and concluded in December 2005 that Greenpeace USA continued to qualify for its tax-exempt status. In March 2006 The Wall Street Journal reported that PIW had been funded by ExxonMobil prior to PIW's request to investigate Greenpeace.[106]

Ships

Since Greenpeace was founded, seagoing ships have played a vital role in its campaigns. Now that the Rainbow Warrior III has been completed, the group has three ocean-going ships, the Esperanza, Arctic Sunrise and Rainbow Warrior III.[107]

The first Rainbow Warrior

In 1978, Greenpeace launched the original Rainbow Warrior, a 40-metre (130 ft), former fishing trawler named for the Cree legend that inspired early activist Robert Hunter on the first voyage to Amchitka. Greenpeace purchased the Rainbow Warrior (originally launched as the Sir William Hardy in 1955) at a cost of £40,000. Volunteers restored and refitted it over a period of four months. First deployed to disrupt the hunt of the Icelandic whaling fleet, the Rainbow Warrior would quickly become a mainstay of Greenpeace campaigns. Between 1978 and 1985, crew members also engaged in direct action against the ocean-dumping of toxic and radioactive waste, the Grey Seal hunt in Orkney and nuclear testing in the Pacific. Japan's Fisheries Agency has labeled Greenpeace ships as "anti-whaling vessels" and "environmental terrorists".[108] In May 1985, the vessel was instrumental for 'Operation Exodus', the evacuation of about 300 Rongelap Atoll islanders whose home had been contaminated with nuclear fallout from a US nuclear test two decades ago which had never been cleaned up and was still having severe health effects on the locals.[109]

Later in 1985 the Rainbow Warrior was to lead a flotilla of protest vessels into the waters surrounding Moruroa atoll, site of French nuclear testing. The sinking of the Rainbow Warrior occurred when the French government secretly bombed the ship in Auckland harbour on orders from François Mitterrand himself. This killed Dutch freelance photographer Fernando Pereira, who thought it was safe to enter the boat to get his photographic material after a first small explosion, but drowned as a result of a second, larger explosion. The attack was a public relations disaster for France after it was quickly exposed by the New Zealand police. The French Government in 1987 agreed to pay New Zealand compensation of NZ$13 million and formally apologised for the bombing. The French Government also paid ₣2.3 million compensation to the family of the photographer.

The second Rainbow Warrior

In 1989 Greenpeace commissioned a replacement vessel, also named the Rainbow Warrior (also referred as Rainbow Warrior II), which was retired from service on the 16th of August 2011 to be replaced by the third Rainbow Warrior. In 2005 the Rainbow Warrior II ran aground on and damaged the Tubbataha Reef in the Philippines while inspecting the reef for coral bleaching. Greenpeace was fined US$7,000 for damaging the reef and agreed to pay the fine saying they felt responsible for the damage, although Greenpeace stated that the Philippines government had given it outdated charts. The park manager of Tubbataha appreciated the quick action Greenpeace took to assess the damage to the reef.[110] .

Other vessels

Along with the Rainbow Warriors, Greenpeace has had several other ships in its service: MV Sirius, MV Solo, MV Greenpeace, MV Arctic Sunrise and MV Esperanza, the last two being in service today.

Reactions and responses to Greenpeace activities

Lawsuits have been filed against Greenpeace for lost profits,[111] reputation damage[112] and "sailor mongering".[113] In 2004 it was revealed that the Australian government was willing to offer a subsidy to Southern Pacific Petroleum on the condition that the oil company would take legal action against Greenpeace, which had campaigned against the Stuart Oil Shale Project.[114]

Some corporations, such as Royal Dutch Shell, BP and Électricité de France have reacted to Greenpeace campaigns by spying on Greenpeace activities and infiltrating Greenpeace offices.[115][116] Greenpeace activists have also been targets of phone tapping, death threats, violence[28] and even state terrorism in the case of bombing of the Rainbow Warrior.[117][118]

Criticism

Early Greenpeace member Canadian Ecologist Patrick Moore left the organization in 1986 when it, according to Moore, decided to support a universal ban on chlorine[119] in drinking water.[21] Moore has argued that Greenpeace today is motivated by politics rather than science and that none of his "fellow directors had any formal science education".[21] Bruce Cox, Director of Greenpeace Canada, responded that Greenpeace has never demanded a universal chlorine ban and that Greenpeace does not oppose use of chlorine in drinking water or in pharmaceutical uses, adding that "Mr. Moore is alone in his recollection of a fight over chlorine and/or use of science as his reason for leaving Greenpeace."[120] Paul Watson, an early member of Greenpeace has said that Moore "uses his status as a so-called co-founder of Greenpeace to give credibility to his accusations. I am also a co-founder of Greenpeace and I have known Patrick Moore for 35 years.[...] Moore makes accusations that have no basis in fact".[121]

A French journalist under the pen name Olivier Vermont wrote in his book La Face cachée de Greenpeace ("The Hidden Face of Greenpeace") that he had joined Greenpeace France and had worked there as a secretary. According to Vermont he found misconduct, and continued to find it, from Amsterdam to the International office. Vermont said he found classified documents[122] according to which half of the organization's € 180 million revenue was used for the organization's salaries and structure. He also accused Greenpeace of having unofficial agreements with polluting companies where the companies paid Greenpeace to keep them from attacking the company's image.[123] Animal protection magazine Animal People reported in March 1997 that Greenpeace France and Greenpeace International had sued Olivier Vermont and his publisher Albin Michel for issuing "defamatory statements, untruths, distortions of the facts and absurd allegations".[124]

Writing in Cosmos, journalist Wilson da Silva reacted to Greenpeace's destruction of a genetically modified wheat crop in Ginninderra as another sign that the organization has "lost its way" and had degenerated into a "sad, dogmatic, reactionary phalanx of anti-science zealots who care not for evidence, but for publicity".[125]

Local greenpeaces

Greenpeace Chile

In Chile, the organization is affiliated as "Greenpeace Chile" was founded in 1981 and is a government recognized NGO there.[126]

Greenpeace East Asia

Greenpeace East Asia's first China office was opened in Hong Kong in 1997. Headquartered in Beijing, the office now campaigns in Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea.[127]

See also

- European Renewable Energy Council

- Fund for Wild Nature

- Civil disobedience

- World Wide Fund for Nature

References

- ^ United Nations, Department of Public Information, Non-Governmental Organizations[dead link]

- ^ Background – January 7, 2010 (2010-01-07). "Greenpeace International: Greenpeace worldwide". Greenpeace.org. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Background – January 8, 2009 (2009-01-08). "Greenpeace International FAQ: Questions about Greenpeace in general". Greenpeace.org. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Sarah Jane Gilbert (2008-09-08). "Harvard Business School, HBS Cases: The Value of Environmental Activists". Hbswk.hbs.edu. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ a b c Greenpeace, Annual Report 2008 (pdf)

- ^ a b Robert Hunter: Greenpeace to Amchitka, An Environmental Odyssey

- ^ a b c d e f Waves of Compassion. The founding of Greenpeace. by Rex Weyler p.19. Retrieved on December 1, 2009 Cite error: The named reference "Waves of Compassion. The founding of Greenpeace." was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Goldenberg, Suzanne (2007-05-25). "Rainbow Warrior ringleader heads firm selling arms to US government". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ^ Luke Cole & Sheila Foster: From the ground up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement (2000)

- ^ "And the biggest NGO in Bali?". New Statesman. 2010-01-07. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ^ Chiara Ciorgetti – From Rio to Kyoto: A Study of the Involvement of Non-Governmental Organizations in the Negotiations on Climate Change N.Y.U. Environmental Law Journal, Volume 7, Issue 2

- ^ "Another summit, another Greenpeace gatecrasher". AFP. 2009-12-17. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- ^ Henry Mintzberg & Frances Westley – Sustaining the Institutional Environment BNET.com

- ^ Canada: A People's History – Greenpeace CBC

- ^ EU commissioner hails blockade on waste shipEUbusiness, 28 September 2006

- ^ Marc Mormont & Christine Dasnoy; Source strategies and the mediatization of climate change. Media, Culture & Society, Vol. 17, No. 1, 49–64 (1995)

- ^ Milmo, Cahal (2009-02-18). "The Independent Wednesday, 18 February 2009: Dumped in Africa: Britain's toxic waste". London: Independent.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ a b c d "UNEP: Our Planet: Celebrating 20 Years of Montreal Protocol" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Adidas, Clarks, Nike and Timberland agree moratorium on illegal Amazon leather Telegraph, 4 August 2009

- ^ Paul Huebener, McMaster University. "Paul Huebener: Greenpeace, ''Globalization and Autonomy Online Compendium''". Globalautonomy.ca. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ a b c Moore, Patrick (2008-04-22). "Why I Left Greenpeace". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- ^ "Top Secret: Greenpeace Report Misleading and Incompetent". Roughlydrafted.com. 2006-09-02. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Shaw, Anny (2010-01-07). "Greenpeace activists arrested for gatecrashing royal gala dinner in Copenhagen released from jail". London: The Daily Mail. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- ^ "Greenpeace members charged in Mount Rushmore G-8 protest". CNN.com. 2010-01-07. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Michael Brown & John May: The Greenpeace Story, ISBN 0-86318-691-2

- ^ Hawthorn, Tom (2011-03-30). "Tom Hawthorn's blog: For sale: The house where Greenpeace was born". Tomhawthorn.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ Greenpeace to Amchitka, An Environmental Odyssey by Robert Hunter.

- ^ a b c "BeforeChaptersMay07" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ a b Background – October 29, 2008 (2008-10-29). "Greenpeace Official page: The Founders". Greenpeace.org. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Interview by Michael Friedrich: Greenpeace Founders". Archive.greenpeace.org. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ "Sea Shepherd Conservation Society: Greenpeace Attempts to Make Captain Paul Watson "Disappear"". Seashepherd.org. 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ "Greenpsirit: Who is Patrick Moore?". Greenspirit.com. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Patrick Moore background information

- ^ Patrick Moore's application letter and Greenpeace's reply (PDF)

- ^ Lost 1970 Amchitka Concert Featuring Joni Mitchell and James Taylor Surfaces The Wall Street Journal, November 22, 2009

- ^ Background – September 14, 2009 (2009-09-14). "Greenpeace International: The History of Greenpeace". Greenpeace.org. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Making Waves the Greenpeace New Zealand Story by Michael Szabo ISBN

- ^ "Greenpeace". Rex Weyler. 1954-03-01. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ [1]| Greenpeace founder Bob Hunter

- ^ "London Greenpeace – A History of Peace, Protest and Campaigning". McSpotlight. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ "About the". Greenpeace Foundation. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ a b Background – March 29, 2007 (2007-03-29). "Who we are". Greenpeace. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "IPCC, Climate Change 2007: Working Group III: Mitigation of Climate Change". Ipcc.ch. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Marc Mormont & Christine Dasnoy; Source strategies and the mediatization of climate change. Media, Culture & Society, Vol. 17, No. 1, 49–64 (1995)

- ^ "UNEP: The 1997 Ozone Awards". Ozone.unep.org. 1997-09-16. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Greenpeace Climate Vision, May 2009

- ^ a b Energy (R)evolution, A Sustainable Global Energy Outlook, 2010, 3rd edition, Greenpeace & EREC:

- ^ "Climate activists shut down coal mine in protest against Fonterra". Stock & Land. 2009-11-23. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ Moskwa, Wojciech (2009-10-02). "Greenpeace blocks Arctic coal mine in Svalbard". Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ "BHP Coal Berth Blocked by Greenpeace Ship as Protest Continues". Bloomberg. 2009-08-06. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ "Greenpeace protestors scale tower in protest at 'Blair's legacy of fumes'". London: Daily Mail. 2006-11-02. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ "Greenpeace activists block giant tar sands mining operation – Message to Obama and Harper: Climate leaders don't buy tar sands". CNW Group. 2009-11-15. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ "Greenpeace blocks 2nd Canada oil sands operation". Thomson Reuters. 2009-10-01. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ Vidal, John (2008-10-06). "Kingsnorth trial: Coal protesters cleared of criminal damage to chimney". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ Clover, Charles (2008-09-11). "Greenpeace Kingsnorth trial collapse is embarrassing for Gordon Brown". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ Vidal, John (2008-09-11). "Not guilty: the Greenpeace activists who used climate change as a legal defence". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ Mingle, Jonathan (2008-12-14). "8th annual year in ideas – Climate-Change Defense". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ a b "Go beyond oil | Greenpeace UK". Greenpeace.org.uk. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ "Paula Bear: Where's your spill response plan, Cairn? | Greenpeace UK". Greenpeace.org.uk. 2011-05-29. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ "Update from the Arctic pod: 48 hours and going strong! | Greenpeace UK". Greenpeace.org.uk. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ "Greenpeace International: 'Nuclear Power: a dangerous waste of time'" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Williams, Rhys (1994-09-07). "Greenpeace accused of telling lies in advert". London: The Independent. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ^ "Kazakhstan highlights nuclear test aftermath". BBC News. 2001-08-30.

- ^ a b Washington Post. Greenpeace Just Kidding About Armageddon. Friday, June 2, 2006; Page A17

- ^ Richard Black (10 November 2011). "EDF fined for spying on Greenpeace nuclear campaign". BBC. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ Hanna Gersmann (10 November 2011). "EDF fined €1.5m for spying on Greenpeace". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ How Unilever Palm Oil Suppliers are burning up Borneo. Greenpeace.org (2008-04-21). Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ Slaughtering the Amazon | Greenpeace USA. Greenpeace.org (2009-06-01). Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ 吃掉亚马逊 | Greenpeace International. Greenpeace.org (2006-04-06). Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ Adidas, Clarks, Nike and Timberland agree moratorium on illegal Amazon leather Telegraph.co.uk, 4 August 2009

- ^ Two-Way Communication: A Win-Win Model for Facing Activist Pressure: A Case Study on McDonalds and Unilever's Responses to Greenpeace. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ Media: Press Releases:2009:Amazon Leather Policy. Nikebiz (2009-07-22). Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ Projects and Activities> Forest carbon > News & commentary > EU bans illegal wood imports. Carbonpositive.net (2010-07-08). Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ Greenpeace Summary of the “REDD from the Conservation Perspective” report, June 2009

- ^ "Finland's environmental administration, 1995". Ymparisto.fi. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ "Stolen trunk of a tree: references from Iltasanomat. 9.6.1995". Vihreavoima.tripod.com. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ "References from Helsingin Sanomat, 1.8.1995". Hs.fi. 1995-01-08. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Häirikkö lintukodossa : Suomen Greenpeace 1989–1998 (vastuullinen julkaisija: Matti Vuori, toimitus: Laura Hakoköngäs, 1998, ISBN 951-97079-3-X)

- ^ Häirikkö lintukodossa : Suomen Greenpeace 1989–1998 (vastuullinen julkaisija: Matti Vuori, toimitus: Laura Hakoköngäs, 1998, ISBN 951-97079-3-X).

- ^ "Metsähallitus: The Nature of Koitajoki (in Finnish)". Luontoon.fi. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Georgina Robinson (June 9, 2010). "Whaling protesters demand release of Tokyo Two". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Japan must respect rights of detained Greenpeace activists | Amnesty International. Amnesty.org (2008-07-15). Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ Feature story – September 30, 2002 (2002-09-30). "Eat this or die, The poison politics of food aid". Greenpeace. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Rory, Carrol (2002-10-30). "Zambia slams door shut on GM relief food". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ "Greenpeace, GM food aid and Zambia". Greenpeace. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Background – November 5, 2010 (2010-11-05). "and golden rice". Greenpeace. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "goldenrice.org". goldenrice.org. 2008-10-17. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Paine JA, Shipton CA, Chaggar S, Howells RM, Kennedy MJ, Vernon G, Wright SY, Hinchliffe E, Adams JL, Silverstone AL, Drake R (2005) A new version of Golden Rice with increased pro-vitamin A content. Nature Biotechnology 23:482–487.

- ^ Greenpeace. Patents on Rice: the Genetic Engineering Hypocrisy. 26 April 2005.

- ^ Checkbiotech.org. Scientists Rebuke Critics of Golden Rice; Biotech Rice Can Benefit Developing World Says AgBioWorld Foundation. February 14, 2001.

- ^ Prof. Dr. Ingo Potrykus Addresses Claims of Anti-Biotechnology Activists. 15 February 2001.

- ^ Greenpeace. Golden Rice: All glitter, no gold. 16 March 2005.

- ^ Greenpeace. Golden Rice is a technical failure standing in way of real solutions for vitamin A deficiency

- ^ Article: Genetically Engineered “Golden” Rice is Unlikely to Overcome Vitamin A Deficiency; Response by Ingo Potrykus.

- ^ Greenpeace.Dirty Laundry: Unravelling the corporate connections to toxic water pollution in China.

- ^ Background – November 13, 2008 (2008-11-13). "Greenpeace, organization". Greenpeace.org. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Background – November 16, 2009 (2009-11-16). "Greenpeace International, Executive Director". Greenpeace.org. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Background – June 8, 2009 (2009-06-08). "Greenpeace International, Board of Directors". Greenpeace.org. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ International home page, Get involved[dead link]

- ^ Governance Structure | Greenpeace International. Greenpeace.org (2006-09-29). Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ a b c "Greenpeace Fundaising policies" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ Relationship Fundraising: A Donor-based Approach to the Business of Raising Money, Ken Burnett, The White Lion Press Limited, 2002

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ [4][dead link]

- ^ Stecklow, Steve (2006-03-21). "Did a Group Financed by Exxon Prompt IRS to Audit Greenpeace?". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Vidal, John (18 January 2010). "Greenpeace commissions third Warrior". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ "Greenpeace Rejects Terrorism Label, 14 December 2001". Archive.greenpeace.org. 2001-12-14. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ The evacuation of Rongelap (from the Greenpeace website. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ^ BBC News. Greenpeace fined for reef damage. 1 November 2005.

- ^ "Suncor sues Greenpeace over protest". CBC News. 2009-10-14.

- ^ Greenpeace sued for Esso logo abuse | Pinsent Masons LLP. Out-law.com (2002-06-27). Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ "U.S. Suit Against Greenpeace Dismissed". Los Angeles Times. 2004-05-20. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ^ Howard Government Offered Oil Firm Millions to Sue Greenpeace. Ens-newswire.com. Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ Campbell, Matthew; Gourlay, Chris (2009-04-26). "French spies targeted UK Greenpeace". London: Times. Retrieved 2010-04-04.

- ^ "MI6 'Firm' Spied on Green Groups". London: The Sunday Times. 2001-06-17. Retrieved 2010-04-04.

- ^ "The Rainbow Warrior bombers, the media and the judiciary, Robie, David, 2007" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Suter, Keith (2003). Global order and global disorder: globalization and the nation-state. Praeger Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 0-275-97388-3.

- ^ Baden, John A. "The anti-chlorine chorus is hitting some bum notes". Seattle Times.

- ^ Cox, Bruce (2008-05-20). "Bruce Cox defends Greenpeace (and takes on Patrick Moore)". National Post. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ Watson, Paul (July 31, 2005). "Solutions instead of sensationalism". The San Francisco Examiner.

- ^ Olivier Vermont (1997), Albin Michel (ed.), La Face cachée de Greenpeace (in French), p. 337, ISBN 978-2226087751

- ^ Développement durable : le concept dévoyé qui ne doit plus durer !, from the Autor of "La Servitude Climatique".

- ^ "Animal People, March 1997". Animalpeoplenews.org. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Wilson da Silva. "The sad, sad demise of Greenpeace". Cosmos. July 14, 2011

- ^ [5]

- ^ "Official website". greenpeace.org/eastasia/. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

Further reading

- Hunter, Robert (2004), The Greenpeace to Amchitka: an environmental odyssey, Arsenal Pulp Press, ISBN 1551521784

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help) - Hunter, Robert and McTaggart, David, Greenpeace III: Journey into the Bomb (London: William Collins Sons & Co., 1978). ISBN 0 211885 8

- Hunter, Robert Warriors of the Rainbow: A Chronicle of the Greenpeace Movement (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1979). ISBN 0-03-043736-9

- Michael King, Death of the Rainbow Warrior (Penguin Books, 1986). ISBN 0-14-009738-4

- John McCormick, The Global Environmental Movement (John Wiley, 1995)

- David Robie, Eyes of Fire: The Last Voyage of the Rainbow Warrior (Philadelphia: New Society Press, 1987). ISBN 0-86571-114-3

- Michael Brown and John May, The Greenpeace Story (1989; London and New York: Dorling Kindersley, Inc., 1991). ISBN 1-879431-02-5

- Ostopowich, Melanie (2002), Greenpeace, Weigl Publishers, ISBN 1590360206

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help) - Rex Weyler (2004), Greenpeace: How a Group of Ecologists, Journalists and Visionaries Changed the World, Rodale ISBN 594861064

- Kieran Mulvaney and Mark Warford (1996): Witness: Twenty-Five Years on the Environmental Front Line, Andre Deutsch.

External links

- Official website

- Greenpeace.mobi: Official mobile homepage

- Waves of Compassion: The Founding of Greenpeace by Rex Weyler

- ReferenceForBusiness.com

- FBI file on Greenpeace

- Greenpeace Sues Chemical Companies for Corporate Espionage – video report by Democracy Now!

- Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (Website)

- Thought Economics interviews Greenpeace Executive Director, Kumi Naidoo - Naidoo looks at the profound issues affecting our earth, including energy and climate change, food security, oceans, forests, international trade, economics and the structure of society.

- Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes from July 2011

- Greenpeace

- Environmental organizations

- Sustainability organisations

- Anti-nuclear organizations in the United States

- Anti–nuclear weapons movement

- Anti–nuclear power movement

- Civil disobedience

- Climate change organizations

- Organizations established in 1971

- International nongovernmental organizations

- Free Your Mind Award winners