Japanese people

The Japanese people (日本人, Nihonjin, Nipponjin) are an ethnic group native to Japan[1][2][3][4][5] Japanese make up 98.5% of the total population.[6] Worldwide, approximately 130 million people are of Japanese descent; of these, approximately 127 million are residents of Japan. People of Japanese ancestry who live in other countries are referred to as nikkeijin (日系人). The term ethnic Japanese may also be used in some contexts to refer to a locus of ethnic groups including the Yamato, Ainu and Ryukyuan people.

Language

The Japanese language is a Japonic language that is sometimes treated as a language isolate; it is also related to the Ryukyuan languages, and both are suggested to be part of the proposed Altaic language family. The Japanese language has a tripartite writing system using Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji. Domestic Japanese people use primarily Japanese for daily interaction. The adult literacy rate in Japan exceeds 99%.[7]

Religion

Japanese religion has traditionally been syncretic in nature, combining elements of Buddhism and Shinto. Shinto, a polytheistic religion with no book of religious canon, is Japan's native religion. Shinto was one of the traditional grounds for the right to the throne of the Japanese imperial family, and was codified as the state religion in 1868 (State Shinto was abolished by the American occupation in 1945). Mahayana Buddhism came to Japan in the sixth century and evolved into many different sects. Today the largest form of Buddhism among Japanese people is the Jōdo Shinshū sect founded by Shinran.[citation needed]

Most Japanese people (84% to 96%)[8] profess to believe in both Shinto and Buddhism. The Japanese people's religion functions mostly as a foundation for mythology, traditions, and neighborhood activities, rather than as the single source of moral guidelines for one's life.[citation needed]

Literature

a character from Japanese literature and folklore.

Certain genres of writing originated in and are often associated with Japanese society. These include the haiku, tanka, and I Novel, although modern writers generally avoid these writing styles. Historically, many works have sought to capture or codify traditional Japanese cultural values and aesthetics. Some of the most famous of these include Murasaki Shikibu's The Tale of Genji (1021), about Heian court culture; Miyamoto Musashi's The Book of Five Rings (1645), concerning military strategy; Matsuo Bashō's Oku no Hosomichi (1691), a travelogue; and Jun'ichirō Tanizaki's essay "In Praise of Shadows" (1933), which contrasts Eastern and Western cultures.

Following the opening of Japan to the West in 1854, some works of this style were written in English by natives of Japan; they include Bushido: The Soul of Japan by Nitobe Inazo (1900), concerning samurai ethics, and The Book of Tea by Okakura Kakuzo (1906), which deals with the philosophical implications of the Japanese tea ceremony. Western observers have often attempted to evaluate Japanese society as well, to varying degrees of success; one of the most well-known and controversial works resulting from this is Ruth Benedict's The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (1946).

Twentieth-century Japanese writers recorded changes in Japanese society through their works. Some of the most notable authors included Natsume Sōseki, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, Osamu Dazai, Yasunari Kawabata, Fumiko Enchi, Yukio Mishima, and Ryōtarō Shiba. In contemporary Japan, popular authors such as Ryū Murakami, Haruki Murakami, and Banana Yoshimoto are highly regarded.

Arts

Decorative arts in Japan date back to prehistoric times. Jōmon pottery includes examples with elaborate ornamentation. In the Yayoi period, artisans produced mirrors, spears, and ceremonial bells known as dōtaku. Later burial mounds, or kofun, preserve characteristic clay haniwa, as well as wall paintings.

Beginning in the Nara period, painting, calligraphy, and sculpture flourished under strong Confucian and Buddhist influences from China. Among the architectural achievements of this period are the Hōryū-ji and the Yakushi-ji, two Buddhist temples in Nara Prefecture. After the cessation of official relations with the Tang Dynasty in the ninth century, Japanese art and architecture gradually became less influenced by China. Extravagant art and clothing was commissioned by nobles to decorate their court life, and although the aristocracy was quite limited in size and power, many of these pieces are still extant. After the Todai-ji was attacked and burned during the Gempei War, a special office of restoration was founded, and the Todai-ji became an important artistic center. The leading masters of the time were Unkei and Kaikei.

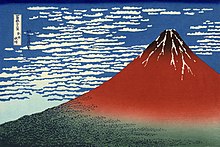

Painting advanced in the Muromachi period in the form of ink and wash painting under the influence of Zen Buddhism as practiced by such masters as Sesshū Tōyō. Zen Buddhist tenets were also elaborated into the tea ceremony during the Sengoku period. During the Edo period, the polychrome painting screens of the Kano school were made influential thanks to their powerful patrons (including the Tokugawas). Popular artists created ukiyo-e, woodblock prints for sale to commoners in the flourishing cities. Pottery such as Imari ware was highly valued as far away as Europe.

In theater, Noh is a traditional, spare dramatic form that developed in tandem with kyōgen farce. In stark contrast to the restrained refinement of noh, kabuki, an "explosion of color," uses every possible stage trick for dramatic effect. Plays include sensational events such as suicides, and many such works were performed in both kabuki and bunraku puppet theaters.

Since the Meiji Restoration, Japan has absorbed elements of Western culture. Its modern decorative, practical, and performing arts works span a spectrum ranging from the traditions of Japan to purely Western modes. Products of popular culture, including J-pop, manga, and anime have found audiences around the world.

Theories of origins

Arai Hakuseki, who knew in the 18th century that there were stone tools in Japan, suggested that there was Shukushin in ancient Japan, and then Philipp Franz von Siebold claimed that indigenous Japanese was Ainu people.[9] Iha Fuyū suggested that Japanese and Ryukyuan people have the same ethnic origin, based on his 1906 research of the Ryukyuan languages.[10] In the Taishō period, Torii Ryūzō claimed that Yamato people used Yayoi pottery and Ainu used Jōmon pottery.[9]

A common origin of Japanese and Koreans has been proposed by a number of scholars since Arai Hakuseki first brought up the theory and Fujii Sadamoto, a pioneer of modern archeology in Japan, also treated the issue in 1781.[11] But after the end of World War II, Kotondo Hasebe and Hisashi Suzuki claimed that the origin of Japanese people was not the newcomers in the Yayoi period (300 BCE – 300 CE) but the people in the Jōmon period.[12]

However, Kazuro Hanihara announced a new racial admixture theory in 1984.[12] Hanihara also announced the theory "dual structure model" in English in 1991.[13] According to Hanihara, modern Japanese lineages began with Jōmon people, who moved into the Japanese archipelago during Paleolithic times from their homeland in southeast Asia. Hanihara believed that there was a second wave of immigrants, from northeast Asia to Japan from the Yayoi period. Following a population expansion in Neolithic times, these newcomers then found their way to the Japanese archipelago sometime during the Yayoi period. As a result, miscegenation was rife in the island regions of Kyūshū, Shikoku, and Honshū, but did not prevail in the outlying islands of Okinawa and Hokkaidō, and the Ryukyuan and Ainu people continued to dominate here. Mark J. Hudson claimed that the main ethnic image of Japanese people was biologically and linguistically formed from 400 BCE to 1,200 CE.[12]

Masatoshi Nei opposed the "dual structure model" and alleged that the genetic distance data show that the Japanese people originated in northeast Asia, moving to Japan perhaps more than thirty thousand years ago.[14]

On the other hand, research in October 2009 by the National Museum of Nature and Science et al. concluded that the Minatogawa Man, who was found in Okinawa and was regarded as evidence that Jōmon people came to Japan via the southern route, had a slender face unlike the Jōmon.[15] Hiroto Takamiya of the Sapporo University suggested that the people of Kyushu immigrated to Okinawa between the 10th and 12th centuries CE.[16]

A 2011 study by Sean Lee and Toshikazu Hasegawa[17] reported that a common origin of Japonic languages had originated around 2,182 years before present.[18]

Origin of Jōmon and Yayoi

Currently, the most well-regarded theory is that present-day Japanese are descendants of both the indigenous Jōmon people and the immigrant Yayoi people. The origins of the Jōmon and Yayoi people have often been a subject of dispute, and a recent Japanese publisher[19] has divided the potential routes of the people living on the Japanese archipelago as follows:

- Aboriginals that have been living in Japan for more than 10,000 years. (Without geographic distinction, which means, the group of people living in islands from Hokkaido to Okinawa may all be considered to be Aboriginals in this case.)

- Immigrants from the northern route (北方ルート in Japanese) including the people from the Korean Peninsula, Mainland China, Sakhalin Island, Mongolia, and Siberia.

- Immigrants from the southern route (南方ルートin Japanese) including the people from the Pacific Islands, Southeast Asia, and in some context, India.

However, a clear consensus has not been reached.[20]

History

Paleolithic era

Archaeological evidence indicates that Stone Age people lived in the Japanese archipelago during the Paleolithic period between 39,000 and 21,000 years ago.[21][22] Japan was then connected to mainland Asia by at least one land bridge, and nomadic hunter-gatherers crossed to Japan from East Asia, Siberia, and possibly Kamchatka. Flint tools and bony implements of this era have been excavated in Japan.[23]

Jōmon people

Some of the world's oldest known pottery pieces were developed by the Jōmon people in the Upper Paleolithic period, 14th millennium BC. The name, "Jōmon" (縄文 Jōmon), which means "cord-impressed pattern", comes from the characteristic markings found on the pottery. The Jōmon people were Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, though at least one middle to late Jōmon site (Minami Mizote (南溝手), ca. 1200–1000 BC) had a primitive rice-growing agriculture. They relied primarily on fish for protein. It is believed that the Jōmon had very likely migrated from North Asia or Central Asia and became the Ainu of today. Research suggests that the Ainu retain a certain degree of uniqueness in their genetic make-up, while having some affinities with other regional populations in Japan as well as the Nivkhs of the Russian Far East. Based on more than a dozen genetic markers on a variety of chromosomes and from archaeological data showing habitation of the Japanese archipelago dating back 30,000 years, it is argued that the Jōmon actually came from northeastern Asia and settled on the islands far earlier than some have proposed.[24]

Yayoi people

Around 400–300 BC, the Yayoi people began to enter the Japanese islands, intermingling with the Jōmon. The Yayoi brought wet-rice farming and advanced bronze and iron technology to Japan. Although the islands were already abundant with resources for hunting and dry-rice farming, Yayoi farmers created more productive wet-rice paddy field systems. This allowed the communities to support larger populations and spread over time, in turn becoming the basis for more advanced institutions and heralding the new civilization of the succeeding Kofun period.

The estimated population in the late Jōmon period was about one hundred thousand, compared to about three million by the Nara period. Taking the growth rates of hunting and agricultural societies into account, it is calculated that about one and half million immigrants moved to Japan in the period.

Genetics

Y-chromosome DNA

An early study of human Y-DNA variation published in 1999 included a sample of 118 Japanese males, among whom haplogroup DE-YAP(xE-SRY4064) was found to be predominant (47%). Other haplogroups detected in this sample include haplogroup K-M9(xN1c-Tat, M2a-SRY9138, P-DYS257) (46%), haplogroup C-M130 (5%), haplogroup P-DYS257(xQ1a3a1-DYS199, R1a1-SRY10831) (2%), and haplogroup BT-SRY10831(xC-RPS4Y711, K-M9, DE-YAP) (1%).[25]

A 2004, Y-DNA study by Tajima et al. reported that the Ainu mainly belong to haplogroup D (87.5%).[26]

A 2005 study by Michael F. Hammer reports genetic similarities between the Japanese and several other Asian populations, which shows that the common Y-DNA haplogroups of Japanese are D-P37.1 (34.7%), O-P31 (31.7%), O-M122 (20.1%), C-M8 (5.4%), C-M217 (3.1%), NO (2.3%) and N (1.5%).[27] The patrilines belonging to D-P37.1 are found in all Japanese groups, but are more frequently found in Ainu (75.0%) and Okinawa (55.6%) and are less frequently found in Shikoku (25.7%) and Kyushu (26.4%).[27] Haplogroup O and C-M8 are not found in Ainu, and C-M217 is not found in Okinawa.[27] Haplogroup N is detected in samples of central Japanese, but is not found in Ainu and Okinawa.[27] This study, and others, report that Y-chromosome patrilines crossed from the Asian mainland into the Japanese archipelago, and continue to make up a large proportion of the Japanese male lineage.[28] If focusing haplogroup O-P31 in those researches, the patrilines derived from its subclade O-SRY465 are frequently found in both Japanese (mean 32%,[29] with frequency in various samples ranging from 26%[30][31] to 36%[32]) and Koreans (mean 30%,[33] with frequency in various samples ranging from 19%[30][34] to 40%[32]). According to the research, these patrilines have undergone extensive genetic admixture with the Jōmon period populations previously established in Japan.[27]

Hammer estimated in 2005 that D-P37.1 and C-M8 emerged around 19,400 and 14,500 years ago respectively and those patrilines are referred to as descendants of indigenous people in Jōmon period.[27] According to a 2008 study by Shi et al., however, if focusing haplogroup D, Andamanese and Tibetan people diverged from the original haplogroup D around from 66,400 to 51,600 years ago, and the Japanese subclade emerged around 37,700 years ago.[35] The study suggested that those patrilines belonging to haplogroup D are possibly the first modern human groups in East Asia based on the Out of Africa theory because their ancestor haplogroup DE is found in African people in Nigeria along with Tibetan in East Asia.[35]

A 2007 study by Nonaka et al. reported that Japanese males in the Kantō region, which includes the Greater Tokyo Area and is the most densely populated region of Japan, mainly belong to haplogroup D-M55 (48%), haplogroup O2b (31%), haplogroup O3 (15%), or haplogroup C-M130 (4%).[36]

A 2010 study by Matsukusa et al. about the peoples in the Sakishima Islands reported that a part of the peoples in Miyako Island and Ishigaki Island also show the marks of YAP+ (53% and 26% respectively), being clearly different from Taiwanese aborigines.[37]

Mitochondrial DNA

A 2002 study by Kivisild et al. reported that Japanese people descended from indigenous Jōmon people may belong to human mitochondrial DNA haplogroup M's subclades—M7a and M7b2.[38] The matrilines of haplogroup M7 are especially common among Ryukyuans, while the matrilines of haplogroup Y1 among Ainu have been interpreted to suggest Eastern Siberian (Okhotsk) immigration to Japan.[38] Although the study reported that those M7 matrilines seem to emerge in up to 18,000 years ago, the study also pointed out that their settlements may have occurred over 30,000 years ago if there was a population bottleneck in Japan.[38]

In another study, ancient DNA recovered from 16 Jomon skeletons excavated from Funadomari site, Hokkaido, Japan was analyzed to elucidate the genealogy of the early settlers of the Japanese archipelago. Both the control and coding regions of their mitochondrial DNA were analyzed in detail, and 14 mtDNAs could be securely assigned to relevant haplogroups. Haplogroups D1a, M7a, and N9b were observed in these individuals, and N9b was by far the most predominant. The fact that haplogroups N9b and M7a were observed in Hokkaido Jomons bore out the hypothesis that these haplogroups are the (pre-) Jomon contribution to the modern Japanese mtDNA pool.[39] In another study of ancient DNA published by the same authors in 2011, both the control and coding regions of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) recovered from Jomon skeletons excavated from the northernmost island of Japan, Hokkaido, were analyzed in detail, and 54 mtDNAs were confidently assigned to relevant haplogroups. Haplogroups N9b, D4h2, G1b, and M7a were observed in these individuals, with N9b being the predominant one.[40] Studies published in 2004 and 2007 show the combined frequency of M7a and N9b to be at least 28% in Okinawans (7/50 M7a1, 6/50 M7a(xM7a1), 1/50 N9b), 17.6% in Ainus (8/51 M7a(xM7a1), 1/51 N9b), and 10% to 17% in mainstream Japanese.[41][42]

After a 2004 study by Tanaka et al. showed that Japanese belongs to various human mitochondrial DNA haplogroups—A, B, C, D, F, G, M, N and Z, a 2008 study by Bilal et al. estimated that haplogroup D4a is related to longevity among Japanese people.[43]

According to an analysis of the 1000 Genome Project's sample of Japanese from the Tokyo metropolitan area, the mtDNA haplogroups found among modern Japanese include D (42/118 = 35.6%, including 39/118 = 33.1% D4 and 3/118 = 2.5% D5), B (16/118 = 13.6%, including 11/118 = 9.3% B4 and 5/118 = 4.2% B5), M7 (12/118 = 10.2%), G (12/118 = 10.2%), N9 (10/118 = 8.5%), F (9/118 = 7.6%), A (8/118 = 6.8%), Z (4/118 = 3.4%), M9 (3/118 = 2.5%), and M8 (2/118 = 1.7%).[44] In another study, the mtDNA of a sample of 100 modern Japanese individuals from Miyazaki Prefecture of eastern Kyushu was tested and assigned to the following haplogroups: 30% D (25/100 D4, 5/100 D5), 22% M7 (15/100 M7a1, 5/100 M7b2, 2/100 M7a(xM7a1)), 12% A (4/100 A4, 4/100 A5, 4/100 A(xA4, A5)), 9% B (3/100 B4b1a1, 2/100 B4a, 2/100 B4(xB4a, B4b1), 2/100 B5b), 6% F, 6% G, 6% N9, 2% M*, 2% M8(xCZ), 1% C, 1% M9a, 1% M10, 1% M11, and 1% Other.[42]

A 2008 study by Nohira et al. reported that Japanese and Koreans shared various haplotypes of haplogroup D4.[45] However, Haplogroup D4 is found at very low frequently in Korean (2,3%) therefore there was an existence of Japanese immigration in Korea peninsula for a period of a time.

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

A 1996 study by Yoshiyuki Okano (Japanese:岡野 滋行) et al. of the Department of Pediatrics, Osaka City University Medical School, said that Japanese people descend from a Northern Mongoloid population from the Baikal area and said the presence of PKU mutation R413P in Northern China as well as Japan showed the effect of the founder effect or genetic drift.[46]

A 2008 study about genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) by Yamaguchi-Kabata et al. reported that the most significant difference between Ryukyuan and Japanese outside Okinawa is the different frequencies of the T allele of rs3827760 in the human EDAR gene.[47]

A 2008 study about genome-wide SNPs of East Asians by Chao Tian et al. reported that Japanese, Koreans and Han Chinese are far from southeast Asians, and Japanese is related to Koreans who are related to Han Chinese, but Japanese is relatively far from Han Chinese if compared to Koreans.[48]

However in another large genome-wide association study of East Asian populations,[49] it was both found that the Japanese are closer to Han Chinese, but the Koreans are relatively far away from Han Chinese if compared to Japanese. This study also included Native Americans, Vietnamese, Cambodians, Europeans and Africans. It was also found in the same paper that, going by Identity By State (a more accurate indicator of genetic similarity and distance compared to Fixation Index[citation needed]) results, the Japanese are more related to the Vietnamese when compared to the Mongolians and Koreans. The Koreans and Mongolians were found to be the least genetically related to the Vietnamese. The Japanese were also more similar by IBS to the Mongolians than the Koreans were. However further studies need to be conducted to infer about relationships between the Jomon Japanese and their genetic relationships to other East Asian ethnic groups to better understand the origins of the Japanese people.

Japanese colonialism

During the Japanese colonial period of 1895 to 1945, the phrase "Japanese people" was used to refer not only to residents of the Japanese archipelago, but also to people from colonies who held Japanese citizenship, such as Taiwanese people and Korean people. The official term used to refer to ethnic Japanese during this period was "inland people" (内地人, naichijin). Such linguistic distinctions facilitated forced assimilation of colonized ethnic identities into a single Imperial Japanese identity.[50]

After the end of World War II, many Nivkh people and Orok people from southern Sakhalin, who held Japanese citizenship in Karafuto Prefecture, were forced to repatriate to Hokkaidō by the Soviet Union as a part of Japanese people. On the other hand, many Sakhalin Koreans who had held Japanese citizenship until the end of the war were left stateless by the Soviet occupation.[51]

Japanese as a Japanese Citizen

Article 10 of the Constitution of Japan defines the term Japanese based on the Japanese Nationality.[52] Indeed, Japan accepts a steady flow of 15,000 new Japanese citizens by naturalization (帰化) per year.[53] The concept of the ethnic groups by the Japanese statistics is different from the ethnicity census of North American or some Western European statistics. For example, the United Kingdom Census asks ethnic or racial background which composites the population of the United Kingdom, regardless of their nationalities.[54] The Japanese Statistics Bureau, however, does not have this question. Since the Japanese population census asks the people's nationality rather than their ethnic background, naturalized Japanese citizens and Japanese nationals with multi-ethnic background are considered to be ethnically Japanese in the population census of Japan. Thus, in spite of the widespread belief that Japan is ethnically homogeneous, it is probably more accurate to describe it as a multiethnic society.[55]

As a result, the word kei (系, can be translated roughly as lineage or origin) is used when the Japanese citizen describe their origin of ancestors other than the Japanese archipelago. For example, Tanya Ishii, a former Japanese member to the Japanese Diet referred herself as a "Russian Japanese" (ロシア系日本人, Roshiakeinihonjin), since she had Russian roots from her maternal lineage.

Japanese diaspora

The term nikkeijin (日系人) is used to refer to Japanese people who emigrated from Japan and their descendants.

Emigration from Japan was recorded as early as the 12th century to the Philippines and Borneo,[56] but did not become a mass phenomenon until the Meiji Era, when Japanese began to go to the Philippines, United States, Canada, Peru, Colombia, Brazil, and Argentina. There was also significant emigration to the territories of the Empire of Japan during the colonial period; however, most such emigrants repatriated to Japan after the end of World War II in Asia.[57]

According to the Association of Nikkei and Japanese Abroad, there are about 2.5 million nikkeijin living in their adopted countries. The largest of these foreign communities are in the Brazilian states of São Paulo and Paraná.[58] There are also significant cohesive Japanese communities in the Philippines, East Malaysia, Peru, Buenos Aires, Córdoba and Misiones in Argentina, and the U.S states of Hawaii, California, and Washington. There is also a small group of Japanese descendants living in Caribbean countries such as Cuba and the Dominican Republic, where hundreds of these immigrants were brought in by Rafael L. Trujillo in the 1930s.[citation needed] Separately, the number of Japanese citizens living abroad is over one million according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

See also

- Ethnic issues in Japan

- Foreign-born Japanese

- Japantown

- List of Japanese people

- Nihonjinron

- Demographics of Japan

- Ainu people

- Azumi (people), an ancient group of peoples who inhabited parts of northern Kyūshū

- Burakumin

- Dekasegi

- Ryukyuan people

- Yamato people

- Emishi, a group of people who lived in the northeastern Tōhoku region of Japan.

References

- ^ "Japanese ethnicity". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Japan. B. Ethnic Groups". Encarta.

- ^ "人類学的にはモンゴロイドの一。皮膚は黄色、虹彩は黒褐色、毛髪は黒色で直毛。言語は日本語。" ("日本人". Kōjien. Iwanami.)

- ^ "人類学上は,旧石器時代あるいは縄文時代以来,現在の北海道〜沖縄諸島(南西諸島)に住んだ集団を祖先にもつ人々。" ("日本人". マイペディア. 平凡社.)

- ^ "日本民族という意味で、文化を基準に人間を分類したときのグループである。また、文化のなかで言語はとくに重要なので、日本民族は日本語を母語としてもちいる人々とほぼ考えてよい。" ("日本人". エンカルタ. Microsoft.)

- ^ CIA World Factbook Retrieved on 11 June 2012.

- ^ United States CIA factbook. Accessed 2007-01-15.

- ^ [1], [2], [3]

- ^ a b Imamura, Keiji (2000). "Archaeological Research of the Jomon Period in the 21st Century". The University Museum, The University of Tokyo. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ^ "伊波普猷の卒論発見 思想骨格 鮮明に" (in Japanese). Ryūkyū Shimpō. July 25, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ Roy A. Miller, The Japanese Language. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle. 1967, pp. 61-62

- ^ a b c Nanta, Arnaud (2008). "Physical Anthropology and the Reconstruction of Japanese Identity in Postcolonial Japan". Social Science Japan Journal. 11 (1). Oxford University Press: 29–47. doi:10.1093/ssjj/jyn019. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- ^ Hanihara.K., Dual structure model for the population history of the Japanese. Japan Review, 2:1-33, 1991

- ^ Nei, M., In : Brenner, S. and Hanihara, K.(eds.), The Origin and Past of Modern Humans as Viewed from DNA. World Scientific, Singapore, 71-91, 1995

- ^ Watanabe, Nobuyuki (October 1, 2009). "旧石器時代の「港川1号」、顔ほっそり 縄文人と差". Asahi.com (in Japanese). Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ Nakamura, Shunsuke (April 16, 2010). "沖縄人のルーツを探る". Asahi.com (in Japanese). Asahi Shimbun. p. 2. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ Hasegawa Laboratory/ College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Tokyo [4]

- ^ Lee, Sean; Hasegawa, Toshikazu (2011). "Bayesian phylogenetic analysis supports an agricultural origin of Japonic languages". Royal Society. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0518. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ {{from the book, 2009, Japanese published by Heidansha. "日本人". マイペディア. 平凡社. Original sentence:旧石器時代または縄文時代以来、現在の北海道から琉球諸島までの地域に住んだ集団を祖先に持つ。シベリア、樺太、朝鮮半島などを経由する北方ルート、南西諸島などを経由する南方ルートなど複数の渡来経路が考えられる}}

- ^ See the following for more information: [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15]

- ^ Global archaeological evidence for proboscidean overkill in PNAS online; Page 3 (page No.6233), Table 1. The known global sample of proboscidean kill/scavenge sites :Lake Nojiri Japan 33-39 ka (ka: thousand years).

- ^ "Prehistoric Times". Web Site Shinshu. Nagano Prefecture. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Lake Nojiri Museum, Lake Nojiri Excavation and Research Team (in Japanese); many flint tools and bony implements were found with the same age of Naumann Elephant in Lake Nojiri.

- ^ Abstract of article from The Journal of Human Genetics. Accessed 2007-01-15.

- ^ T. M. Karafet, S. L. Zegura, O. Posukh et al., "Ancestral Asian Source(s) of New World Y-Chromosome Founder Haplotypes," American Journal of Human Genetics 64 : 817–831, 1999

- ^ Tajima, Atsushi; Hayami, Masanori; Tokunaga, Katsushi; Juji, Takeo; Matsuo, Masafumi; Marzuki, Sangkot; Omoto, Keiichi; Horai, Satoshi (2004). "Genetic origins of the Ainu inferred from combined DNA analyses of maternal and paternal lineages" (PDF). The Japan Society of Human Genetics and Springer-Verlag. 49 (4). Springer Science+Business Media via Invint.Net: 187–193. doi:10.1007/s10038-004-0131-x. PMID 14997363. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Hammer, Michael F. (2005). "Dual origins of the Japanese: common ground for hunter-gatherer and farmer Y chromosomes" (PDF). The Japan Society of Human Genetics and Springer-Verlag. 51 (1). Springer Science+Business Media via Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology: 47–58. doi:10.1007/s10038-005-0322-0. PMID 16328082. Retrieved January 19, 2007.

- ^ Travis, John (February 15, 1997). "Jomon genes: using DNA, researchers probe the genetic origins of modern Japanese - Cover Story". Science News. BNET. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ 238/744 = 32.0% O2b-SRY465 in a pool of all Japanese samples of Xue et al. (2006), Katoh et al. (2004), Han-Jun Jin et al. (2009), Nonaka et al. (2007), and all non-Ainu and non-Okinawan Japanese samples of Hammer et al. (2006).

- ^ a b Han-Jun Jin, Kyoung-Don Kwak, Michael F. Hammer, Yutaka Nakahori, Toshikatsu Shinka, Ju-Won Lee, Feng Jin, Xuming Jia, Chris Tyler-Smith and Wook Kim, "Y-chromosomal DNA haplogroups and their implications for the dual origins of the Koreans," Human Genetics (2003)

- ^ Jin, Han-Jun; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Kim, Wook (2009). "The Peopling of Korea Revealed by Analyses of Mitochondrial DNA and Y-Chromosomal Markers". PLoS ONE. 4 (1): e4210. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004210. PMID 19148289.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Katoh, Toru; Munkhbat, Batmunkh; Tounai, Kenichi; Mano, Shuhei; Ando, Harue; Oyungerel, Ganjuur; Chae, Gue-Tae; Han, Huun; Jia, Guan-Jun; Tokunaga, Katsushi; Munkhtuvshin, Namid; Tamiya, Gen; Inoko, Hidetoshi (2004). "Genetic features of Mongolian ethnic groups revealed by Y-chromosomal analysis". Gene. 346: 63–70. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2004.10.023. PMID 15716011.

- ^ 202/677 = 29.8% O2b-SRY465 in a pool of all ethnic Korean samples of Hammer et al. (2006), Xue et al. (2006), Katoh et al. (2004), Wook Kim et al. (2007), and Han-Jun Jin et al. (2009).

- ^ Kim, Wook; Yoo, Tag-Keun; Kim, Sung-Joo; Shin, Dong-Jik; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Jin, Han-Jun; Kwak, Kyoung-Don; Kim, Eun-Tak; Bae, Yoon-Sun (January 24, 2007). "Lack of Association between Y-Chromosomal Haplogroups and Prostate Cancer in the Korean Population". PLoS ONE. 2 (1): e172. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000172. PMC 1766463. PMID 17245448.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Shi, Hong; Zhong, Hua; Peng, Yi; Dong, Yong-li; Qi, Xue-bin; Zhang, Feng; Liu, Lu-Fang; Tan, Si-jie; Ma, Run-lin (October 29, 2008). "Y chromosome evidence of earliest modern human settlement in East Asia and multiple origins of Tibetan and Japanese populations". BMC Biology. 6. BioMed Central: 45. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-6-45. PMC 2605740. PMID 18959782. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Nonaka, I.; Minaguchi, K.; Takezaki, N. (February 2, 2007). "Y-chromosomal Binary Haplogroups in the Japanese Population and their Relationship to 16 Y-STR Polymorphisms". Annals of Human Genetics. 71 (Pt 4). John Wiley & Sons: 480–95. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00343.x. PMID 17274803.

- ^ Matsukusa, Hirotaka; Oota, Hiroki; Haneji, Kuniaki; Toma, Takashi; Kawamura, Shoji; Ishida, Hajime (2010). "A Genetic Analysis of the Sakishima Islanders Reveals No Relationship With Taiwan Aborigines but Shared Ancestry With Ainu and Main-Island Japanese". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 142 (2). John Wiley & Sons: 211–223. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21212. PMID 20091849.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Kivisild, Toomas; Tolk, HV; Parik, J; Wang, Y; Papiha, SS; Bandelt, HJ; Villems, R (October 19, 2002). "The Emerging Limbs and Twigs of the East Asian mtDNA Tree". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 19 (10). Oxford University Press: 1737–51. PMID 12270900. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18951391

- ^ Adachi N, Shinoda K, Umetsu K, Kitano T, Matsumura H, Fujiyama R, Sawada J, and Tanaka M, "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Hokkaido Jomon skeletons: remnants of archaic maternal lineages at the southwestern edge of former Beringia," Am J Phys Anthropol. 2011 Nov;146(3):346-60. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21561. Epub 2011 Sep 27.

- ^ M. Tanaka, V. M. Cabrera, A. M. González et al. (2004), "Mitochondrial Genome Variation in Eastern Asia and the Peopling of Japan" [16]

- ^ a b Taketo Uchiyama, Rinnosuke Hisazumi, Kenshi Shimizu et al., "Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variation and Phylogenetic Analysis in Japanese Individuals from Miyazaki Prefecture," 日本法科学技術学会誌 (Japanese Journal of Forensic Science and Technology) 12(1), 83-96 (2007)

- ^ Bilal, Erhan; Rabadan, Raul; Alexe, Gabriela; Fuku, Noriyuki; Ueno, Hitomi; Nishigaki, Yutaka; Fujita, Yasunori; Ito, Masafumi; Arai, Yasumichi (June 11, 2008). Kronenberg, Florian (ed.). "Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroup D4a Is a Marker for Extreme Longevity in Japan". PLoS ONE. 3 (6). Public Library of Science: e2421. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002421. PMC 2408726. PMID 18545700. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Zheng H-X, Yan S, Qin Z-D, Wang Y, Tan J-Z, et al. 2011 Major Population Expansion of East Asians Began before Neolithic Time: Evidence of mtDNA Genomes. PLoS ONE 6(10): e25835. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025835

- ^ Nohira, C.; Maruyama, S.; Minaguchi, K. (2010). "Phylogenetic classification of Japanese mtDNA assisted by complete mitochondrial DNA sequences" (PDF). International Journal of Legal Medicine. 124 (1). Springer Science+Business Media: 7–12. doi:10.1007/s00414-008-0308-5. PMID 19066930. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ Y. OKANO, Y. HASE, D.-H. LEE 3, G. TAKADA, Y. SHIGEMATSU, T. OURA 6 and G. ISSHIKI Molecular and Population Genetics of Phenylketonuria in Orientals: Correlation between Phenotype and Genotype. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 17 (1994) 156-159

- ^ Yamaguchi-Kabata, Yumi; Nakazono, K; Takahashi, A; Saito, S; Hosono, N; Kubo, M; Nakamura, Y; Kamatani, N (October 10, 2008). "Japanese Population Structure, Based on SNP Genotypes from 7003 Individuals Compared to Other Ethnic Groups: Effects on Population-Based Association Studies". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 83 (4): 445–456. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.019. PMC 2561928. PMID 18817904.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help) - ^ Tian, Chao; Kosoy, Roman; Lee, Annette; Ransom, Michael; Belmont, John W.; Gregersen, Peter K.; Seldin, Michael F. (December 5, 2008). "Analysis of East Asia Genetic Substructure Using Genome-Wide SNP Arrays". PLoS ONE. 3 (12). Public Library of Science: e3862. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003862. PMC 2587696. PMID 19057645. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Karafet TM, Jung J, Kang H, Cho YS, Oh JH, Ryu MH, Chung HW, Seo JS, Lee JE, Oh B, Bhak J, Kim HL, "Gene flow between the Korean peninsula and its neighboring countries," PLoS One (2010)

- ^ Eika Tai (2004). "Korean Japanese". Critical Asian Studies. 36 (3). Routledge: 355. doi:10.1080/1467271042000241586.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lankov, Andrei (January 5, 2006). "Stateless in Sakhalin". The Korea Times. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ^ [日本国憲法]

- ^ 帰化許可申請者数等の推移

- ^ "United Kingdom population by ethnic group". United Kingdom Census 2001. Office for National Statistics. 2001-04-01. Retrieved 2009-09-10. [dead link]

- ^ John Lie Multiethnic Japan (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001)

- ^ [17]

- ^ Lankov, Andrei (March 23, 2006). "The Dawn of Modern Korea (360): Settling Down". The Korea Times. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ IBGE. Resistência e Integração: 100 anos de Imigração Japonesa no Brasil apud Made in Japan. IBGE Traça o Perfil dos Imigrantes; 21 de junho de 2008 Accessed September 4, 2008. Template:Pt icon

External links

- C3-M217, FTDNA [DNA project]

- CIA The World Fact Book 2006

- The Association of Nikkei & Japanese Abroad

- Discover Nikkei- Information on Japanese emigrants and their descendants

- Jun-Nissei Literature and Culture in Brazil

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan Template:En icon

- The National Museum of Japanese History Template:En icon

- Japanese society and culture

- Dekasegi and their issues living in Japan Template:Pt icon Template:Ja icon