Satan

Satan (Hebrew: שָּׂטָן satan, meaning "adversary";[1] Arabic: شيطان shaitan, meaning; "astray", "distant", or sometimes "devil") is a figure appearing in the texts of the Abrahamic religions[2][3] who brings evil and temptation, and is known as the deceiver who leads humanity astray. Some religious groups teach that he originated as an angel who fell out of favor with God, seducing humanity into the ways of sin, and who has power in the fallen world. In the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, Satan is primarily an accuser and adversary, a decidedly malevolent entity, also called the devil, who possesses demonic qualities.

In Theistic Satanism, Satan is considered a positive force and deity who is either worshipped or revered. In LaVeyan Satanism, Satan is regarded as holding virtuous characteristics.[4][5]

Judaism

Hebrew Bible

The original Hebrew term satan is a noun from a verb meaning primarily "to obstruct, oppose", as it is found in Numbers 22:22, 1 Samuel 29:4, Psalms 109:6.[6] Ha-Satan is traditionally translated as "the accuser" or "the adversary". The definite article ha- (English: "the") is used to show that this is a title bestowed on a being, versus the name of a being. Thus, this being would be referred to as "the satan".[7]

Thirteen occurrences

Ha-Satan with the definite article occurs 13 times in the Masoretic Text, in two books of the Hebrew Bible: Job ch.1–2 (10x)[8] and Zechariah 3:1–2 (3x).[9]

Satan without the definite article is used in 10 instances, of which two are translated diabolos in the Septuagint and "Satan" in the King James Version:

- 1 Chronicles 21:1, "Satan stood up against Israel" (KJV) or "And there standeth up an adversary against Israel" (Young's Literal Translation)[10]

- Psalm 109:6b "and let Satan stand at his right hand" (KJV)[11] or "let an accuser stand at his right hand." (ESV, etc.)

The other eight instances of satan without the definite article are traditionally translated (in Greek, Latin and English) as "an adversary", etc., and taken to be humans or obedient angels:

- Numbers 22:22,32 "and the angel of the LORD stood in the way for an adversary against him."

- 32 "behold, I went out to withstand thee,"

- 1 Samuel 29:4 The Philistines say: "lest he [David] be an adversary against us"

- 2 Samuel 19:22 David says: "[you sons of Zeruaiah] should this day be adversaries (plural) unto me?"

- 1 Kings 5:4 Solomon writes to Hiram: "there is neither adversary nor evil occurrent."

- 1 Kings 11:14 "And the LORD stirred up an adversary unto Solomon, Hadad the Edomite"[12]

- 1 Kings 11:23 "And God stirred him up an adversary, Rezon the son of Eliadah"

- 25 "And he [Rezon] was an adversary to Israel all the days of Solomon"

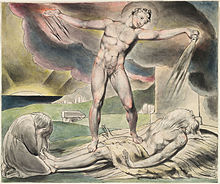

Book of Job

At the beginning of the book, Job is a good person "who revered God and turned away from evil" (Job 1:1), and has therefore been rewarded by God. When the angels present themselves to God, Satan comes as well. God informs Satan about Job's blameless, morally upright character. Between Job 1:9–10 and 2:4–5, Satan points out that God has given Job everything that a man could want, so of course Job would be loyal to God; Satan suggests that Job's faith would collapse if all he has been given (even his health) were to be taken away from him. God therefore gives Satan permission to test Job.[13] In the end, Job remains faithful and righteous, and there is the implication that Satan is shamed in his defeat.[14]

Second Temple period

Septuagint

In the Septuagint, the Hebrew ha-Satan in Job and Zechariah is translated by the Greek word diabolos (slanderer), the same word in the Greek New Testament from which the English word devil is derived. Where satan is used of human enemies in the Hebrew Bible, such as Hadad the Edomite and Rezon the Syrian, the word is left untranslated but transliterated in the Greek as satan, a neologism in Greek.[15] In Zechariah 3, this changes the vision of the conflict over Joshua the High Priest in the Septuagint into a conflict between "Jesus and the devil", identical with the Greek text of Matthew.

Dead Sea scrolls and Pseudepigrapha

In Enochic Judaism, the concept of Satan being an opponent of God and a chief evil figure in among demons seems to have taken root in Jewish pseudepigrapha during the Second Temple period,[16] particularly in the apocalypses.[17] The Book of Enoch contains references to Satariel, thought also to be Sataniel and Satan'el (etymology dating back to Babylonian origins). The similar spellings mirror that of his angelic brethren Michael, Raphael, Uriel, and Gabriel, previous to the fall from Heaven.

The Second Book of Enoch, also called the Slavonic Book of Enoch, contains references to a Watcher (Grigori) called Satanael.[18] It is a pseudepigraphic text of an uncertain date and unknown authorship. The text describes Satanael as being the prince of the Grigori who was cast out of heaven[19] and an evil spirit who knew the difference between what was "righteous" and "sinful".[20] A similar story is found in the book of 1 Enoch; however, in that book, the leader of the Grigori is called Semjâzâ.

In the Book of Wisdom, the devil is represented as the being who brought death into the world.[21]

In the Book of Jubilees, Mastema induces God to test Abraham through the sacrifice of Isaac. He is identical to Satan in both name and nature.[22]

Rabbinical Judaism

In Judaism, Satan is a term used since its earliest biblical contexts to refer to a human opponent.[23] Occasionally, the term has been used to suggest evil influence opposing human beings, as in the Jewish exegesis of the Yetzer hara ("evil inclination" Genesis 6:5). Micaiah's "lying spirit" in 1 Kings 22:22 is sometimes related. Thus, Satan is personified as a character in three different places of the Tenakh, serving as an accuser (Zechariah 3:1–2), a seducer (1 Chronicles 21:1), or as a heavenly persecutor who is "among the sons of God" (Job 2:1). In any case, Satan is always subordinate to the power of God, having a role in the divine plan. Satan is rarely mentioned in Tannaitic literature, but is found in Babylonian aggadah.[17]

In medieval Judaism, the Rabbis rejected these Enochic literary works into the Biblical canon, making every attempt to root them out.[16] Traditionalists and philosophers in medieval Judaism adhered to rational theology, rejecting any belief in rebel or fallen angels, and viewing evil as abstract.[24] The Yetzer hara ("evil inclination" Genesis 6:5) is a more common motif for evil in rabbinical texts. Rabbinical scholarship on the Book of Job generally follows the Talmud and Maimonides as identifying the "Adversary" in the prologue of Job as a metaphor.[25]

In Hasidic Judaism, the Kabbalah presents Satan as an agent of God whose function is to tempt one into sin, then turn around and accuse the sinner on high. [vague] The Chasidic Jews of the 18th century associated ha-Satan with Baal Davar.[26]

Dualism and Zoroastrianism

Some scholars see contact with religious dualism in Babylon, and early Zoroastrianism in particular, as being influenced by Second Temple period Judaism, and consequently early Christianity.[27][28] Subsequent development of Satan as a "deceiver" has parallels with the evil spirit in Zoroastrianism, known as the Lie, who directs forces of darkness.[29]

Christianity

Satan is traditionally identified as the serpent who tempted Eve to eat the forbidden fruit, as he was in Judaism.[30] Thus Satan has often been depicted as a serpent. Christian agreement with this can be found in the works of Justin Martyr, in Chapters 45 and 79 of Dialogue with Trypho, where Justin identifies Satan and the serpent.[31] Other early church fathers to mention this identification include Theophilus and Tertullian.[32]

From the fourth century, Lucifer is sometimes used in Christian theology to refer to Satan, as a result of identifying the fallen "son of the dawn" of Isaiah 14:12 with the "accuser" of other passages in the Old Testament.[citation needed]

For most Christians, Satan is believed to be an angel who rebelled against God. His goal is to lead people away from the love of God; i.e., to lead them to evil.[citation needed]

In the New Testament he is called "the ruler of the demons" (Matthew 12:24), "the ruler of the world", and "the god of this world" (2 Cor. 4:4). The Book of Revelation describes how Satan was cast out of Heaven, having "great anger" and waging war against "those who obey God's commandments". Ultimately, Satan will be thrown into the lake of fire.[33]

The early Christian church encountered opposition from pagans such as Celsus, who claimed that "it is blasphemy...to say that the greatest God...has an adversary who constrains his capacity to do good" and said that Christians "impiously divide the kingdom of God, creating a rebellion in it, as if there were opposing factions within the divine, including one that is hostile to God".[34]

Terminology

In Christianity, there are many synonyms for Satan. The most common English synonym for "Satan" is "Devil", which descends from Middle English devel, from Old English dēofol, that in turn represents an early Germanic borrowing of Latin diabolus (also the source of "diabolical"). This in turn was borrowed from Greek diabolos "slanderer", from diaballein "to slander": dia- "across, through" + ballein "to hurl".[35] In the New Testament, "Satan" occurs more than 30 times in passages alongside Diabolos (Greek for "the devil"), referring to the same person or thing as Satan.[36]

Beelzebub, meaning "Lord of Flies", is the contemptuous name given in the Hebrew Bible and New Testament to a Philistine god whose original name has been reconstructed as most probably "Ba'al Zabul", meaning "Baal the Prince".[37] This pun was later used to refer to Satan as well.

The Book of Revelation twice refers to "the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is called the devil and Satan" (12:9, 20:2). The Book of Revelation also refers to "the deceiver", from which is derived the common epithet "the great deceiver".[38]

Islam

Shaitan (شيطان) is the equivalent of Satan in Islam. While Shaitan (شيطان, from the root šṭn شطن) is an adjective (meaning "astray" or "distant", sometimes translated as "devil") that can be applied to both man ("al-ins", الإنس) and Jinn, Iblis (Arabic pronunciation: [ˈibliːs]) is the personal name of the Devil who is mentioned in the Qur'anic account of Genesis.[39] According to the Qur'an, Iblis (the Arabic name used) disobeyed an order from Allah to bow to Adam, and as a result Iblis was forced out of heaven. However, he was given respite from further punishment until the day of judgment.

When Allah commanded all of the angels to bow down before Adam (the first Human), Iblis, full of hubris and jealousy, refused to obey God's command (he could do so because he had free will), seeing Adam as being inferior in creation due to his being created from clay as compared to him (created of fire).[40]

It is We Who created you and gave you shape; then We bade the angels prostrate to Adam, and they prostrate; not so Iblis (Lucifer); He refused to be of those who prostrate. (Allah) said: "What prevented thee from prostrating when I commanded thee?" He said: "I am better than he: Thou didst create me from fire, and him from clay."

— Qur'an 7:11–12

It was after this that the title of "Shaitan" was given, which can be roughly translated as "Enemy", "Rebel", "Evil", or "Devil". Shaitan then claims that, if the punishment for his act of disobedience is to be delayed until the Day of Judgment, then he will divert many of Adam's own descendants from the straight path during his period of respite.[41] God accepts the claims of Iblis and guarantees recompense to Iblis and his followers in the form of Hellfire. In order to test mankind and jinn alike, Allah allowed Iblis to roam the earth to attempt to convert others away from his path.[42] He was sent to earth along with Adam and Eve, after eventually luring them into eating the fruit from the forbidden tree.[43]

Yazidism

An alternative name for the main deity in the tentatively Indo-European pantheon of the Yazidis, Melek Taus, is Shaitan.[44] However, rather than being Satanic, Yazidism is better understood as a remnant of a pre-Islamic Middle Eastern Indo-European religion, and/or a ghulat Sufi movement founded by Shaykh Adi. The connection with Satan, originally made by Muslim outsiders, attracted the interest of 19th-century European travelers and esoteric writers.

Bahá'í Faith

In the Bahá'í Faith, Satan is not regarded as an independent evil power as he is in some faiths, but signifies the lower nature of humans. `Abdu'l-Bahá explains: "This lower nature in man is symbolized as Satan — the evil ego within us, not an evil personality outside."[45][46] All other evil spirits described in various faith traditions—such as fallen angels, demons, and jinns—are also metaphors for the base character traits a human being may acquire and manifest when he turns away from God.[47]

Satanism

Within Satanism, two major trends exists, theistic Satanism and atheistic Satanism, both having different views regarding the essence of Satan.

Theistic Satanism

Theistic Satanism, commonly referred to as 'devil-worship',[48] holds that Satan is an actual deity or force to revere or worship that individuals may contact and supplicate to,[49][50] and represents loosely affiliated or independent groups and cabals which hold the belief that Satan is a real entity[51] rather than an archetype.

Among non-Satanists, much modern Satanic folklore does not originate with the beliefs or practices of theistic or atheistic Satanists, but a mixture of medieval Christian folk beliefs, political or sociological conspiracy theories, and contemporary urban legends.[52][53][54][55] An example is the Satanic ritual abuse scare of the 1980s—beginning with the memoir Michelle Remembers—which depicted Satanism as a vast conspiracy of elites with a predilection for child abuse and human sacrifice.[53][54] This genre frequently describes Satan as physically incarnating in order to receive worship.[55]

Atheistic Satanism

Atheistic Satanism, most commonly referred to as LaVeyan Satanism, holds that Satan does not exist as a literal anthropomorphic entity, but rather a symbol of pride, carnality, liberty, enlightenment, undefiled wisdom, and of a cosmos which Satanists perceive to be permeated and motivated by a force that has been given many names by humans over the course of time. To adherents, he also serves as a conceptual framework and an external metaphorical projection of [the Satanists] highest personal potential.[56][57][58][59][60][61]

In his essay, "Satanism: The Feared Religion", the current High Priest of the Church of Satan, Peter H. Gilmore, further expounds that "...Satan is a symbol of Man living as his prideful, carnal nature dictates. The reality behind Satan is simply the dark evolutionary force of entropy that permeates all of nature and provides the drive for survival and propagation inherent in all living things. Satan is not a conscious entity to be worshiped, rather a reservoir of power inside each human to be tapped at will."[62]

Notes

- ^ http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/13219-satan "Term used in the Bible with the general connotation of "adversary", being applied (1) to an enemy in war (I Kings v. 18 [A. V. 4]; xi. 14, 23, 25), from which use is developed the concept of a traitor in battle (I Sam. xxix. 4); (2) to an accuser before the judgment-seat (Ps. cix. 6); and (3) to any opponent (II Sam. xix. 23 [A. V. 22]). The word is likewise used to denote an antagonist who puts obstacles in the way, as in Num. xxii. 32, where the angel of God is described as opposing Balaam in the guise of a satan or adversary; so that the concept of Satan as a distinct being was not then known."

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions, page 290, Wendy Doniger

- ^ Leeming, David Adams (2005). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-19-515669-0.

- ^ Contemporary Religious Satanisim: A Critical Reader, Jesper Aagaard Petersen – 2009

- ^ Who's ? Right: Mankind, Religions and the End Times, page 35, Kelly Warman-Stallings – 2012

- ^ ed. Buttrick, George Arthur; The Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, An illustrated Encyclopedia

- ^ Crenshaw, James L. Harper Collins Study Bible (NRSV), 1989

- ^ Stephen M. Hooks – 2007 "As in Zechariah 3:1–2 the term here carries the definite article (has'satan="the satan") and functions not as a ... the only place in the Hebrew Bible where the term "Satan" is unquestionably used as a proper name is 1 Chronicles 21:1."

- ^ Coogan, Michael D.; A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: The Hebrew Bible in its context, Oxford University Press, 2009

- ^ Rachel Adelman The Return of the Repressed: Pirqe De-Rabbi Eliezer p65 "However, in the parallel versions of the story in Chronicles, it is Satan (without the definite article),"

- ^ Septuagint 108:6 κατάστησον ἐπ᾽ αὐτὸν ἁμαρτωλόν καὶ διάβολος στήτω ἐκ δεξιῶν αὐτοῦ

- ^ Ruth R. Brand Adam and Eve p88 – 2005 "Later, however, King Hadad 1 Kings 11:14) and King Rezon (verses 23, ... Numbers 22:22, 23 does not use the definite article but identifies the angel of YHWH as "a satan."

- ^ HarperCollins Study Bible (NRSV)

- ^ Steinmann, AE. "The structure and message of the Book of Job". Vetus testamentum.

- ^ Henry Ansgar Kelly Satan: a biography 2006 "However, for Hadad and Rezon they left the Hebrew term untranslated and simply said satan.. in the three passages in which a supra-Human satan appears: namely, Numbers, Job, Zechariah

- ^ a b Jackson, David R. (2004). Enochic Judaism. London: T&T Clark International. pp. 2–4. ISBN 0826470890.

- ^ a b Berlin, editor in chief, Adele (2011). The Oxford dictionary of the Jewish religion (2nd ed. ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 651. ISBN 0199730040.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 2 Enoch 18:3. On this tradition, see A. Orlov, "The Watchers of Satanael: The Fallen Angels Traditions in 2 (Slavonic) Enoch," in: A. Orlov, Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology (Albany: SUNY, 2011) 85–106.

- ^ "And I threw him out from the height with his angels, and he was flying in the air continuously above the bottomless" – 2 Enoch 29:4

- ^ "The devil is the evil spirit of the lower places, as a fugitive he made Sotona from the heavens as his name was Satanail, thus he became different from the angels, but his nature did not change his intelligence as far as his understanding of righteous and sinful things" – 2 Enoch 31:4

- ^ See The Book of Wisdom: With Introduction and Notes, p. 27, Object of the book, by A. T. S. Goodrick.

- ^ [ Introduction to the Book of Jubilees, 15. Theology. Some of our Author's Views: Demonology, by R.H. Charles.

- ^ Based on the Jewish exegesis of 1 Samuel 29:4 and 1 Kings 5:18 – Oxford dictionary of the Jewish religion, 2011, p. 651 "Satan is rarely mentioned in tannaitic literature; later, chiefly Babylonian, aggadah enlarges the scope of his influence and activities. Perhaps because of the influential presence of Satan as a name or character in the New Testament and the"

- ^ Bamberger, Bernard J. (2006). Fallen angels : soldiers of satan's realm (1. paperback ed. ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Jewish Publ. Soc. of America. p. 148,149. ISBN 0827607970.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Robert Eisen Associate Professor of Religious Studies George Washington University The Book of Job in Medieval Jewish Philosophy 2004 p120 "Moreover, Zerahfiiah gives us insight into the parallel between the Garden of Eden story and the Job story alluded to ... both Satan and Job's wife are metaphors for the evil inclination, a motif Zerahfiiah seems to identify with the imagination."

- ^ The Dictionary of Angels" by Gustav Davidson, © 1967

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell, The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive ...1977, page 102 "This conflict between truth and the lie was one of the main sources of Zarathushtra's dualism: the prophet perceived Angra Mainyu, the lord of evil, as the personification of the lie. For Zoroastrians (as for the Egyptians), the lie was the essence ... "

- ^ Peter Clark, Zoroastrianism: An Introduction to Ancient Faith 1998, page 152 "There are so many features that Zoroastrianism seems to share with the Judeo-Christian tradition that it would be difficult to ... Historically the first point of contact that we can determine is when the Achaemenian Cyrus conquered Babylon ..539 BC"

- ^ Winn, Shan M.M. (1995). Heaven, heroes, and happiness : the Indo-European roots of Western ideology. Lanham, Md.: University press of America. p. 203. ISBN 0819198609.

- ^ http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/13219-satan.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Kelly, Harry Ansgar (2007). Satan: a Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-521-84339-3.

- ^ Kelly, Harry Ansgar (2007). Satan: a Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-521-84339-3.

- ^ Revelation 20:10

- ^ Origen. Contra Celsum. Book 6. Ch 42.

- ^ "American Heritage Dictionary: Devil". Retrieved 2006-05-31.

- ^ Revelation 12:9

- ^ K. van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter Willem van der Horst, Baalzebub, "Dictionary of deities and demons in the Bible", p. 155

- ^ B. W. Johnson (1891). "The Revelation of John. Chapter XX. The Millennium". The People's New Testament. Memorial University of Newfoundland. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ Iblis

- ^ [Quran 17:61]; [Quran 2:34]

- ^ [Quran 17:62]

- ^ [Quran 17:63–64]

- ^ [Quran 7:20–22]

- ^ Drower, E.S. The Peacock Angel. Being Some Account of Votaries of a Secret Cult and their Sanctuaries. London: John Murray, 1941. [1]

- ^ ʻAbduʾl-Bahá (1982) [1912]. The Promulgation of Universal Peace. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. pp. 294–295. ISBN 0-87743-172-8.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2000). A Concise Encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford, UK: Oneworld. pp. 135–136, 304. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2008). An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-521-86251-5.

- ^ http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-29448079

- ^ Partridge, Christopher Hugh (2004). The Re-enchantment of the West. p. 82. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ Satanism and Demonology, by Lionel & Patricia Fanthorpe, Dundurn Press, 8 Mar 2011, p. 74, "If, as theistic Satanists believe, the devil is an intelligent, self-aware entity..." "Theistic Satanism then becomes explicable in terms of Lucifer's ambition to be the supreme god and his rebellion against Yahweh. [...] This simplistic, controntational view is modified by other theistic Satanists who do not regard their hero as evil: far from it. For them he is a freedom fighter..."

- ^ "Interview_MLO". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- ^ Cinema of the Occult: New Age, Satanism, Wicca, and Spiritualism in Film, Carrol Lee Fry, Associated University Presse, 2008, pp. 92–98

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of Urban Legends, Updated and Expanded Edition, by Jan Harold Brunvand, ABC-CLIO, 31 Jul 2012 pp. 694–695

- ^ a b Raising the Devil: Satanism, New Religions, and the Media, by Bill Ellis, University Press of Kentucky p. 125 In discussing myths about groups accused of Satanism, "...such myths are already pervasive in Western culture, and the development of the modern "Satanic Scare" would be impossible to explain without showing how these myths helped organize concerns and beliefs." Accusations of Satanism are traced from the witch hunts, to the Illuminati, to the Satanic Ritual Abuse panic in the 1980s, with a distinction made between what modern Satanists believe and what is believed about Satanists.

- ^ a b Satan in America: The Devil We Know, by W. Scott Poole, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 16 Nov 2009, pp. 42–43

- ^ name="altreligion.about.com">http://altreligion.about.com/od/alternativereligionsaz/a/satanism.htm

- ^ http://www.churchofsatan.com/Pages/WhatTheDevil.html

- ^ http://www.churchofsatan.com/Pages/_FAQ03.html

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ http://www.churchofsatan.com/Pages/ChaplainsHandbook.html

- ^ Contemporary religious Satanism: a critical anthology, page 45, Jesper Aagaard Petersen, 2009

- ^ http://churchofsatan.com/satanism-the-feared-religion.php

References

- Bamberger, Bernard J. (2006). Fallen Angels: Soldiers of Satan's Realm. Jewish Publication Society of America. ISBN 0-8276-0797-0.

- Caldwell, William. "The Doctrine of Satan: I. In the Old Testament", The Biblical World, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Jan., 1913), pp. 29–33 in JSTOR

- Caldwell, William. "The Doctrine of Satan: II. Satan in Extra-Biblical Apocalyptical Literature", The Biblical World, Vol. 41, No. 2 (Feb., 1913), pp. 98–102 in JSTOR

- Caldwell, William. "The Doctrine of Satan: III. In the New Testament", The Biblical World, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Mar., 1913), pp. 167–172 in JSTOR

- Empson, William. Milton's God (1966)

- Forsyth, Neil (1987). The Old Enemy: Satan & the Combat Myth. Princeton University Press; Reprint edition. ISBN 0-691-01474-4.

- Forsyth, Neil (1987). The Satanic Epic. Princeton University Press; Reprint edition. ISBN 0-691-11339-4.

- Gentry, Kenneth L. Jr (2002). The Beast of Revelation. American Vision. ISBN 0-915815-41-9.

- Graves, Kersey (1995). Biography of Satan: Exposing the Origins of the Devil. Book Tree. ISBN 1-885395-11-6.

- ‘’The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, An illustrated Encyclopedia’’;ed. Buttrick, George Arthur; Abingdon Press 1962

- Jacobs, Joseph, and Ludwig Blau. "Satan," The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) online pp 68–71

- Kelly, Henry Ansgar. Satan: A Biography. (2006). 360 pp. excerpt and text search ISBN 0-521-60402-8, a study of the Bible and Western literature

- Kent, William. "Devil." The Catholic Encyclopedia (1908) Vol. 4. online older article

- Osborne, B. A. E. "Peter: Stumbling-Block and Satan," Novum Testamentum, Vol. 15, Fasc. 3 (Jul., 1973), pp. 187–190 in JSTOR on "Get thee behind me, Satan!"

- Pagels, Elaine (1995). The Origin of Satan. Vintage; Reprint edition. ISBN 0-679-72232-7.

- Rebhorn Wayne A. "The Humanist Tradition and Milton's Satan: The Conservative as Revolutionary," Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900, Vol. 13, No. 1, The English Renaissance (Winter, 1973), pp. 81–93 in JSTOR

- Rudwin, Maximilian (1970). The Devil in Legend and Literature. Open Court. ISBN 0-87548-248-1.

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton. The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity (1987) excerpt and text search

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton. Satan: The Early Christian Tradition (1987) excerpt and text search

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton. Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages (1986) excerpt and text search

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton. Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World (1990) excerpt and text search

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton. The Prince of Darkness: Radical Evil and the Power of Good in History (1992) excerpt and text search

- Schaff, D. S. "Devil" in New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (1911), Mainline Protestant; vol 3 pp 414–417 online

- Scott, Miriam Van. The Encyclopedia of Hell (1999) excerpt and text search comparative religions; also popular culture

- Wray, T. J. and Gregory Mobley. The Birth of Satan: Tracing the Devil's Biblical Roots (2005) excerpt and text search

External links

- Catholic Encyclopedia — "Devil"

- Jewish Encyclopedia — "Satan"

- The Internet Sacred Texts Archive hosts texts—scriptures, literature and scholarly works—on Satan, Satanism and related religious matters

- The Brotherhood of Satan’s perspective on Satan and Lucifer.