H. P. Lovecraft

H. P. Lovecraft | |

|---|---|

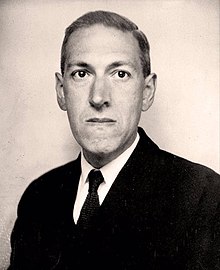

Lovecraft in 1934 | |

| Born | Howard Phillips Lovecraft August 20, 1890 Providence, Rhode Island, USA |

| Died | March 15, 1937 (aged 46) Providence, Rhode Island |

| Resting place | Swan Point Cemetery, Providence, Rhode Island |

| Pen name | Lewis Theobald Humphrey Littlewit Ward Phillips Edward Softly |

| Occupation | Short-story writer, editor, novelist, poet |

| Period | 1917–1937 |

| Genre | Dark, Fantasy, Gothic, Horror, Science fiction, Weird |

| Literary movement | Cosmicism |

| Notable works | |

| Spouse | Sonia Greene (1924–1926) |

| Signature | |

Howard Phillips Lovecraft (/ˈlʌvkræft, -ˌkrɑːft/;[1] August 20, 1890 – March 15, 1937), known as H. P. Lovecraft, was an American author who achieved posthumous fame through his influential works of horror fiction. Virtually unknown and only published in pulp magazines before he died in poverty, he is now regarded as one of the most significant 20th-century authors in his genre.

Lovecraft was born in Providence, Rhode Island, where he spent most of his life. His father was confined to a mental institution when Lovecraft was three years old. His grandfather, a wealthy businessman, enjoyed storytelling and was an early influence. Intellectually precocious but sensitive, Lovecraft began composing rudimentary horror tales by the age of eight, but suffered from overwhelming feelings of anxiety. He encountered problems with classmates in school, and was kept at home by his highly strung and overbearing mother for illnesses that may have been psychosomatic. In high school, Lovecraft was able to better connect with his peers and form friendships. He also involved neighborhood children in elaborate make-believe projects, only regretfully ceasing the activity at seventeen years old. Despite leaving school in 1908 without graduating—he found mathematics particularly difficult—Lovecraft had developed a formidable knowledge of his favored subjects, such as history, linguistics, chemistry, and astronomy.

Although he seems to have had some social life, attending meetings of a club for local young men, Lovecraft, in early adulthood, was established in a reclusive "nightbird" lifestyle without occupation or pursuit of romantic adventures. In 1913 his conduct of a long running controversy in the letters page of a story magazine led to his being invited to participate in an amateur journalism association. Encouraged, he started circulating his stories; he was 31 at the time of his first publication in a professional magazine. Lovecraft contracted a marriage to an older woman he had met at an association conference. By age 34, he was a regular contributor to the newly founded Weird Tales magazine; he turned down an offer of the editorship.

Lovecraft returned to Providence from New York in 1926 and, over the next nine months, he produced some of his most celebrated tales, including "The Call of Cthulhu", canonical to the Cthulhu Mythos. Never able to support himself from earnings as author and editor, Lovecraft saw commercial success increasingly elude him in this latter period, partly because he lacked the confidence and drive to promote himself. He subsisted in progressively straitened circumstances in his last years; an inheritance was completely spent by the time he died at the age of 46.[2]

Early life

Family

Lovecraft was born on August 20, 1890, in his family home at 194 (later 456) Angell Street in Providence, Rhode Island.[3] (The house was demolished in 1961.) He was the only child of Winfield Scott Lovecraft, a traveling salesman of jewelry and precious metals, and Sarah Susan Phillips Lovecraft, who could trace her ancestry to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1631.[4] Both of his parents were of entirely English ancestry, all of which had been in New England since the colonial period.[5][6] In 1893, when Lovecraft was three, his father became acutely psychotic and was placed in the Providence psychiatric institution, Butler Hospital, where he remained until his death in 1898.[3] H. P. Lovecraft maintained throughout his life that his father had died in a condition of paralysis brought on by "nervous exhaustion". Although it has been suggested his father's mental illness may have been caused by syphilis, neither the younger Lovecraft nor his mother (who also died in Butler Hospital) seems to have shown signs of being infected with the disease.[7]

After his father's hospitalization, Lovecraft was raised by his mother, his two aunts (Lillian Delora Phillips and Annie Emeline Phillips), and his maternal grandfather, Whipple Van Buren Phillips, an American businessman. All five resided together in the family home. Lovecraft was a prodigy, reciting poetry at the age of three, and writing complete poems by six. His grandfather encouraged his reading, providing him with classics such as The Arabian Nights, Bulfinch's Age of Fable, and children's versions of the Iliad and the Odyssey. His grandfather also stirred the boy's interest in the weird by telling him his own original tales of Gothic horror.[8]

Upbringing

Lovecraft was frequently ill as a child. Because of his sickly condition, he barely attended school until he was eight years old, and then was withdrawn after a year. He read voraciously during this period and became especially enamored of chemistry and astronomy. He produced several hectographed publications with a limited circulation, beginning in 1899 with The Scientific Gazette. Four years later, he returned to public school at Hope High School.[9] Beginning in his early life, Lovecraft is believed to have suffered from night terrors, a form of parasomnia; he believed himself to be assaulted at night by horrific "night gaunts". Much of his later work is thought to have been directly inspired by these terrors. (Indeed, "Night Gaunts" became the subject of a poem he wrote of the same name, in which they were personified as devil-like creatures without faces.)

His grandfather's death in 1904 greatly affected Lovecraft's life. Mismanagement of his grandfather's estate left his family in a poor financial situation, and they were forced to move into much smaller accommodations at 598 (now a duplex at 598–600) Angell Street. In 1908, prior to his high school graduation, he said to have suffered what he later described as a "nervous breakdown", and consequently never received his high school diploma (although he maintained for most of his life that he did graduate).[citation needed] S. T. Joshi suggests in his biography of Lovecraft that a primary cause for this breakdown was his difficulty in higher mathematics, a subject he needed to master to become a professional astronomer.[citation needed]

Adulthood

Reclusion

The adult Lovecraft was gaunt with dark eyes set in a very pale face (he rarely went out before nightfall).[10] For five years after leaving school, he lived an isolated existence with his mother, writing primarily poetry without seeking employment or new social contacts. This changed in 1913 when he wrote a letter to The Argosy, a pulp magazine, complaining about the insipidness of the love stories in the publication by writer Fred Jackson.[11] The ensuing debate in the magazine's letters column caught the eye of Edward F. Daas, president of the United Amateur Press Association (UAPA), who invited Lovecraft to join the organization in 1914.

Writing

The UAPA reinvigorated Lovecraft and incited him to contribute many poems and essays; in 1916, his first published story, The Alchemist, appeared in the United Amateur. The earliest commercially published work came in 1922, when he was thirty-one. By this time he had begun to build what became a huge network of correspondents. His lengthy and frequent missives would make him one of the great letter writers of the century. Among his correspondents were Robert Bloch (Psycho), Clark Ashton Smith, and Robert E. Howard (Conan the Barbarian series). Many former aspiring authors later paid tribute to his mentoring and encouragement through the correspondence.[10]

His oeuvre is sometimes seen as consisting of three periods: an early Edgar Allan Poe influence; followed by a Lord Dunsany inspired Dream Cycle; and finally the Cthulhu Mythos stories. However, many distinctive ideas and entities present in the third period were introduced in the earlier works, such as the 1917 story "Dagon", and the threefold classification is partly overlapping.[12]

Death of mother

In 1919, after suffering from hysteria and depression for a long period of time, Lovecraft's mother was committed to the mental institution—Butler Hospital—where her husband had died.[13] Nevertheless, she wrote frequent letters to Lovecraft, and they remained close until her death on May 24, 1921, the result of complications from gall bladder surgery.

Marriage and New York

A few days after his mother's death, Lovecraft attended a convention of amateur journalists in Boston, Massachusetts, where he met and became friendly with Sonia Greene, owner of a successful hat shop and seven years his senior. Lovecraft's aunts disapproved of the relationship. Lovecraft and Greene married on March 3, 1924, and relocated to her Brooklyn apartment; she thought he needed to get out of Providence in order to flourish and was willing to support him financially.[14] Greene, who had been married before, later said Lovecraft had performed satisfactorily as a lover, though she had to take the initiative in all aspects of the relationship.[14] She attributed Lovecraft's passive nature to a stultifying upbringing by his mother.[14] Lovecraft's weight increased to 90 kg (200 lb) on his wife's home cooking.[14]

He was enthralled by New York, and, in what was informally dubbed the Kalem Club, he acquired a group of encouraging intellectual and literary friends who urged him to submit stories to Weird Tales; editor Edwin Baird accepted many otherworldly 'Dream Cycle' Lovecraft stories for the ailing publication, though they were heavily criticized by a section of the readership.[citation needed] Established informally some years before Lovecraft lived in New York, the core Kalem Club members were boys' adventure novelist Henry Everett McNeil; the lawyer and anarchist writer James Ferdinand Morton, Jr.; and the poet Reinhardt Kleiner. In 1925 these four regular attendees were joined by Lovecraft along with his protégé Frank Belknap Long, bookseller George Willard Kirk, and Lovecraft's close friend Samuel Loveman. Loveman was Jewish, but was unaware of Lovecraft's nativist attitudes. Conversely, it has been suggested Lovecraft, who disliked mention of sexual matters, was unaware that Loveman and some of his other friends were homosexual.[15]

Financial difficulties

Not long after the marriage, Greene lost her business and her assets disappeared in a bank failure; she also became ill. Lovecraft made efforts to support his wife through regular jobs, but his lack of previous work experience meant he lacked proven marketable skills. After a few unsuccessful spells as a low level clerk, his job-seeking became desultory. The publisher of Weird Tales attempted to put the loss-making magazine on a business footing and offered the job of editor to Lovecraft, who declined, citing his reluctance to relocate to Chicago; "think of the tragedy of such a move for an aged antiquarian," the 34-year-old writer declared. Baird was replaced with Farnsworth Wright, whose writing Lovecraft had criticized. Lovecraft's submissions were often rejected by Wright. (This may have been partially due to censorship guidelines imposed in the aftermath of a Weird Tales story that hinted at necrophilia, although after Lovecraft's death Wright accepted many of the stories he had originally rejected.)[16][17]

Red Hook

Greene, moving where the work was, relocated to Cincinnati, and then to Cleveland; her employment required constant travel. Added to the daunting reality of failure in a city with a large immigrant population, Lovecraft's single room apartment in the run down area of Red Hook was burgled, leaving him with only the clothes he was wearing. In August 1925 he wrote "The Horror at Red Hook" and "He", in the latter of which the narrator says "My coming to New York had been a mistake; for whereas I had looked for poignant wonder and inspiration ... I had found instead only a sense of horror and oppression which threatened to master, paralyze, and annihilate me". It was at around this time he wrote the outline for "The Call of Cthulhu" with its theme of the insignificance of all humanity. In the bibliographical study H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life, Michel Houellebecq suggested that the misfortunes fed Lovecraft's central motivation as a writer, which he said was racial resentment.[18] With a weekly allowance Greene sent, Lovecraft moved to a working class area of Brooklyn Heights where he subsisted in a tiny apartment. He had lost 40 lb of bodyweight by 1926, when he left for Providence.[18][19]

Return to Providence

Back in Providence, Lovecraft lived in a "spacious brown Victorian wooden house" at 10 Barnes Street until 1933. The same address is given as the home of Dr. Willett in Lovecraft's The Case of Charles Dexter Ward. The period beginning after his return to Providence—the last decade of his life—was Lovecraft's most prolific; in that time he produced short stories, as well as his longest work of fiction The Case of Charles Dexter Ward and At the Mountains of Madness. He frequently revised work for other authors and did a large amount of ghost-writing, including "The Mound", "Winged Death", "The Diary of Alonzo Typer". Client Harry Houdini was laudatory, and attempted to help Lovecraft by introducing him to the head of a newspaper syndicate. Plans for a further project were ended by Houdini's death.[20]

Although he was able to combine his distinctive style (allusive and amorphous description by horrified though passive narrators) with the kind of stock content and action Weird Tales's editor wanted—Wright paid handsomely to snap up "The Dunwich Horror" which proved very popular with readers—Lovecraft increasingly produced work that brought him no remuneration. Affecting a calm indifference to the reception of his works, Lovecraft was in reality extremely sensitive to criticism and easily precipitated into withdrawal. He was known to give up trying to sell a story after it had been once rejected. Sometimes, as with The Shadow Over Innsmouth (which included a rousing chase that supplied action) he wrote a story that might have been commercially viable, but did not try to sell it. Lovecraft even ignored interested publishers. He failed to reply when one inquired about any novel Lovecraft might have ready, although he had completed such a work: The Case of Charles Dexter Ward; it was never typed up.[21]

Last years

Throughout his life, selling stories and paid literary work for others did not provide enough to cover Lovecraft's basic expenses. Living frugally, he subsisted on an inheritance that was nearly depleted by the time of his last years. He sometimes went without food to afford the cost of mailing letters.[10] Eventually, he was forced to move to smaller and meaner lodgings with his surviving aunt. He was also deeply affected by the suicide of his correspondent Robert E. Howard. In early 1937, Lovecraft was diagnosed with cancer of the small intestine,[22] and suffered from malnutrition as a result. He lived in constant pain until his death on March 15, 1937, in Providence.

In accordance with his lifelong scientific curiosity, he kept a diary of his illness until close to the moment of his death.

Lovecraft was listed along with his parents on the Phillips family monument (41°51′14″N 71°22′52″W / 41.8540176°N 71.3810921°W). That was not enough for his fans, who in 1977 raised the money to buy him a headstone of his own in Swan Point Cemetery, on which they had inscribed Lovecraft's name, the dates of his birth and death, and the phrase "I AM PROVIDENCE", a line from one of his personal letters.[citation needed]

Groups of enthusiasts annually observe the anniversaries of Lovecraft's death at Ladd Observatory and of his birth at his grave site. In July 2013, the Providence City Council designated the intersection of Angell and Prospect streets near the author's former residences as "H. P. Lovecraft Memorial Square" and installed a commemorative sign.[23]

Appreciation

Within genre

According to Joyce Carol Oates, Lovecraft – as with Edgar Allan Poe in the 19th century – has exerted "an incalculable influence on succeeding generations of writers of horror fiction".[24] Horror, fantasy, and science fiction author Stephen King called Lovecraft "the twentieth century's greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale."[25][26] King has made it clear in his semi-autobiographical non-fiction book Danse Macabre that Lovecraft was responsible for King's own fascination with horror and the macabre, and was the single largest figure to influence his fiction writing.[27]

Literary

Early efforts to revise an established literary view of Lovecraft as an author of 'pulp' were resisted by some eminent critics; in 1945 Edmund Wilson expressed the opinion that "the only real horror in most of these fictions is the horror of bad taste and bad art". But "Mystery and Adventure" columnist Will Cuppy of the New York Herald Tribune recommended to readers a volume of Lovecraft's stories, asserting that "the literature of horror and macabre fantasy belongs with mystery in its broader sense." [28] In 2005 the status of classic American writer conferred by a Library of America edition was accorded to Lovecraft with the publication of Tales, a collection of his weird fiction stories.[29]

Philosophical

Philosopher Graham Harman, seeing Lovecraft as having a unique—though implicit—anti-reductionalist ontology, says "No other writer is so perplexed by the gap between objects and the power of language to describe them, or between objects and the qualities they possess."[30] Harman said of leading figures at the initial speculative realism conference (which included philosophers Quentin Meillassoux, Ray Brassier, and Iain Hamilton Grant) that, though they shared no philosophical heroes, all were enthusiastic readers of Lovecraft.[31] According to scholar S. T. Joshi: "There is never an entity in Lovecraft that is not in some fashion material".[32]

Themes

This section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (February 2009) |

Several themes recur in Lovecraft's stories:

| Now all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large. To me there is nothing but puerility in a tale in which the human form—and the local human passions and conditions and standards—are depicted as native to other worlds or other universes. To achieve the essence of real externality, whether of time or space or dimension, one must forget that such things as organic life, good and evil, love and hate, and all such local attributes of a negligible and temporary race called mankind, have any existence at all. Only the human scenes and characters must have human qualities. These must be handled with unsparing realism, (not catch-penny romanticism) but when we cross the line to the boundless and hideous unknown—the shadow-haunted Outside—we must remember to leave our humanity and terrestrialism at the threshold. |

| — H. P. Lovecraft, in note to the editor of Weird Tales, on resubmission of "The Call of Cthulhu".[33] |

Forbidden knowledge

Forbidden, darkly esoterically veiled knowledge is a central theme in many of Lovecraft's works.[34] Many of his characters are driven by curiosity or scientific endeavor, and in many of his stories the knowledge they uncover proves Promethean in nature, either filling the seeker with regret for what they have learned, destroying them psychically, or completely destroying the person who holds the knowledge.[34][35][36][37][38][39]

Some critics argue that this theme is a reflection of Lovecraft's contempt of the world around him, causing him to search inwardly for knowledge and inspiration.[40]

Non-human influences on humanity

The beings of Lovecraft's mythos often have human servants; Cthulhu, for instance, is worshiped under various names by cults amongst both the Greenland Inuit and voodoo circles of Louisiana, and in many other parts of the world.

These worshippers served a useful narrative purpose for Lovecraft. Many beings of the Mythos were too powerful to be defeated by human opponents, and so horrific that direct knowledge of them meant insanity for the victim. When dealing with such beings, Lovecraft needed a way to provide exposition and build tension without bringing the story to a premature end. Human followers gave him a way to reveal information about their "gods" in a diluted form, and also made it possible for his protagonists to win paltry victories. Lovecraft, like his contemporaries, envisioned "savages" as closer to supernatural knowledge unknown to civilized man.

Inherited guilt

Another recurring theme in Lovecraft's stories is the idea that descendants in a bloodline can never escape the stain of crimes committed by their forebears, at least if the crimes are atrocious enough. Descendants may be very far removed, both in place and in time (and, indeed, in culpability), from the act itself, and yet, they may be haunted by the revenant past, e.g. "The Rats in the Walls", "The Lurking Fear", "Arthur Jermyn", "The Alchemist", "The Shadow Over Innsmouth", "The Doom that Came to Sarnath" and The Case of Charles Dexter Ward.

Fate

Often in Lovecraft's works the protagonist is not in control of his own actions, or finds it impossible to change course. Many of his characters would be free from danger if they simply managed to run away; however, this possibility either never arises or is somehow curtailed by some outside force, such as in "The Colour Out of Space" and "The Dreams in the Witch House". Often his characters are subject to a compulsive influence from powerful malevolent or indifferent beings. As with the inevitability of one's ancestry, eventually even running away, or death itself, provides no safety ("The Thing on the Doorstep", "The Outsider", The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, etc.). In some cases, this doom is manifest in the entirety of humanity, and no escape is possible ("The Shadow Out of Time").

Civilization under threat

Lovecraft was familiar with the work of the German conservative-revolutionary theorist Oswald Spengler, whose pessimistic thesis of the decadence of the modern West formed a crucial element in Lovecraft's overall anti-modern worldview. Spenglerian imagery of cyclical decay is present in particular in At the Mountains of Madness. S. T. Joshi, in H. P. Lovecraft: The Decline of the West, places Spengler at the center of his discussion of Lovecraft's political and philosophical ideas.[41]

Lovecraft wrote to Clark Ashton Smith in 1927: "It is my belief, and was so long before Spengler put his seal of scholarly proof on it, that our mechanical and industrial age is one of frank decadence".[42] Lovecraft was also acquainted with the writings of another German philosopher of decadence: Friedrich Nietzsche.[43]

Lovecraft frequently dealt with the idea of civilization struggling against dark, primitive barbarism. In some stories this struggle is at an individual level; many of his protagonists are cultured, highly educated men who are gradually corrupted by some obscure and feared influence.

In such stories, the "curse" is often a hereditary one, either because of interbreeding with non-humans (e.g., "Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family" (1920), "The Shadow over Innsmouth" (1931) or through direct magical influence (The Case of Charles Dexter Ward). Physical and mental degradation often come together; this theme of 'tainted blood' may represent concerns relating to Lovecraft's own family history, particularly the death of his father due to what Lovecraft must have suspected to be a syphilitic disorder.

In other tales, an entire society is threatened by barbarism. Sometimes the barbarism comes as an external threat, with a civilized race destroyed in war (e.g., "Polaris"). Sometimes, an isolated pocket of humanity falls into decadence and atavism of its own accord (e.g., "The Lurking Fear"). But most often, such stories involve a civilized culture being gradually undermined by a malevolent underclass influenced by inhuman forces.

There is a lack of analysis as to whether England's gradual loss of prominence and related conflicts (Boer War, India, World War I) had an influence on Lovecraft's worldview. It is likely that the "roaring twenties" left Lovecraft disillusioned as he was still obscure and struggling with the basic necessities of daily life, combined with seeing non-Western European immigrants in New York City.

Race, ethnicity, and class

Racism is the most controversial aspect of Lovecraft's works which "does not endear Lovecraft to the modern reader," and it comes across through many disparaging remarks against the various non-Anglo-Saxon races and cultures within his work. As he grew older, the more "jagged" aspects of his original Anglo-Saxon racial worldview softened into a universal classism or elitism regarding any fellow human being of self-ennobled high culture as of metaphorical "superior race." Lovecraft did not from the start hold all white people in uniform high regard, but rather he held English people and people of English descent, above all others.[44][45][46][46] However some groups, such as people of Spanish descent are praised in his work as well. An example of this is the short story "Cool Air" in which a Latino doctor of Spanish descent in New York who is central to the story is described as being "A Spanish physician" of "striking intelligence and superior blood and breeding", and he is described as "short but exquisitely proportioned", with a "high-bred face of masterful though not arrogant expression", "a short iron-grey full beard", "full, dark eyes" and "an aquiline nose".[47] While his racist perspective is undeniable, many critics argue this does not detract from his ability to create compelling philosophical worlds which have inspired many artists and readers.[22][46] In his early published essays, private letters and personal utterances, he argued for a strong color line, for the purpose of preserving race and culture.[22][44][45][48] These arguments occurred through direct statements against different races in his journalistic work and personal correspondence,[18][22][44][45][46] or perhaps allegorically in his work using non-human races.[36][44][49][50] Some have interpreted his racial attitude as being more cultural than brutally biological: Lovecraft showed sympathy to others who pacifically assimilated into Western culture, to the extent of even marrying a Jewish woman whom he viewed as "well assimilated."[22][44][45][50] While Lovecraft's racial attitude has been seen as directly influenced by the time, a reflection of the New England society he grew up in,[44][45][46][51][52] his racism appeared stronger than the popular viewpoints held at that time.[46][50] Some researchers also note that his views failed to change in the face of increased social change of that time.[22][44]

Risks of a scientific era

At the turn of the 20th century, man's increased reliance upon science was both opening new worlds and solidifying the manners by which he could understand them. Lovecraft portrays this potential for a growing gap of man's understanding of the universe as a potential for horror. Most notably in "The Colour Out of Space", the inability of science to comprehend a contaminated meteorite leads to horror.

In a letter to James F. Morton in 1923, Lovecraft specifically points to Einstein's theory on relativity as throwing the world into chaos and making the cosmos a jest; in a letter to Woodburn Harris in 1929, he speculates that technological comforts risk the collapse of science. Indeed, at a time when men viewed science as limitless and powerful, Lovecraft imagined alternative potential and fearful outcomes. In "The Call of Cthulhu", Lovecraft's characters encounter architecture which is "abnormal, non-Euclidean, and loathsomely redolent of spheres and dimensions apart from ours".[53] Non-Euclidean geometry is the mathematical language and background of Einstein's general theory of relativity, and Lovecraft references it repeatedly in exploring alien archaeology.

Religion

Lovecraft's works are ruled by several distinct pantheons of deities (actually aliens who are worshiped by humans as deities) who are either indifferent or actively hostile to humanity. Lovecraft's actual philosophy has been termed "cosmic indifferentism" and this is expressed in his fiction. Several of Lovecraft's stories of the Old Ones (alien beings of the Cthulhu Mythos) propose alternate mythic human origins in contrast to those found in the creation stories of existing religions, expanding on a natural world view. For instance, in Lovecraft's "At the Mountains of Madness" it is proposed that humankind was actually created as a slave race by the Old Ones, and that life on Earth as we know it evolved from scientific experiments abandoned by the Elder Things. Protagonist characters in Lovecraft are usually educated men, citing scientific and rationalist evidence to support their non-faith. Herbert West–Reanimator reflects on the atheism common within academic circles. In "The Silver Key", the character Randolph Carter loses the ability to dream and seeks solace in religion, specifically Congregationalism, but does not find it and ultimately loses faith.

Lovecraft himself adopted the stance of atheism early in his life. In 1932 he wrote in a letter to Robert E. Howard: "All I say is that I think it is damned unlikely that anything like a central cosmic will, a spirit world, or an eternal survival of personality exist. They are the most preposterous and unjustified of all the guesses which can be made about the universe, and I am not enough of a hairsplitter to pretend that I don't regard them as arrant and negligible moonshine. In theory I am an agnostic, but pending the appearance of radical evidence I must be classed, practically and provisionally, as an atheist."[54]

Influences on Lovecraft

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2012) |

Some of Lovecraft's work was inspired by his own nightmares. His interest started from his childhood days when his grandfather would tell him Gothic horror stories.

Lovecraft's most significant literary influence was Edgar Allan Poe. He had a British writing style due to his love of British literature. Like Lovecraft, Poe's work was out of step with the prevailing literary trends of his era. Both authors created distinctive, singular worlds of fantasy and employed archaisms in their writings. This influence can be found in such works as his novella The Shadow Over Innsmouth[55] where Lovecraft references Poe's story ‘’The Imp of the Perverse’’ by name in Chapter 3, and in his poem "Nemesis", where the “…ghoul-guarded gateways of slumber"[56] suggest the "…ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir"[57] found in Poe's "Ulalume". A direct quote from the poem and a reference to Poe's only novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket is alluded to in Lovecraft's magnum opus At the Mountains of Madness. Both authors shared many biographical similarities as well, such as the loss of their fathers at young ages and an early interest in poetry.

He was influenced by Arthur Machen's carefully constructed tales concerning the survival of ancient evil into modern times in an otherwise realistic world and his beliefs in hidden mysteries which lay behind reality. Lovecraft was also influenced by authors such as Oswald Spengler and Robert W. Chambers. Chambers was the writer of The King in Yellow, of whom Lovecraft wrote in a letter to Clark Ashton Smith: "Chambers is like Rupert Hughes and a few other fallen Titans – equipped with the right brains and education but wholly out of the habit of using them". Lovecraft's discovery of the stories of Lord Dunsany, with their pantheon of mighty gods existing in dreamlike outer realms, moved his writing in a new direction, resulting in a series of imitative fantasies in a "Dreamlands" setting.

Lovecraft also cited Algernon Blackwood as an influence, quoting The Centaur in the head paragraph of "The Call of Cthulhu". He declared Blackwood's story "The Willows" to be the single best piece of weird fiction ever written.[58]

Another inspiration came from a completely different source: scientific progress in biology, astronomy, geology, and physics. His study of science contributed to Lovecraft's view of the human race as insignificant, powerless, and doomed in a materialistic and mechanistic universe. Lovecraft was a keen amateur astronomer from his youth, often visiting the Ladd Observatory in Providence, and penning numerous astronomical articles for local newspapers. His astronomical telescope is now housed in the rooms of the August Derleth Society.

Lovecraft's materialist views led him to espouse his philosophical views through his fiction; these philosophical views came to be called cosmicism. Cosmicism took on a dark tone with his creation of what is today often called the Cthulhu Mythos, a pantheon of alien extra-dimensional deities and horrors which predate humanity, and which are hinted at in eons-old myths and legends. The term "Cthulhu Mythos" was coined by Lovecraft's correspondent and fellow author, August Derleth, after Lovecraft's death; Lovecraft jocularly referred to his artificial mythology as "Yog-Sothothery".

Lovecraft considered himself a man best suited to the early 18th century. His writing style, especially in his many letters, owes much to Augustan British writers of the Enlightenment like Joseph Addison and Jonathan Swift.

Among the books found in his library (as evidenced in Lovecraft's Library by S. T. Joshi) was The Seven Who Were Hanged by Leonid Andreyev and A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder by James De Mille.

Lovecraft's style has often been criticized by unsympathetic critics, yet scholars such as S. T. Joshi have shown that Lovecraft consciously utilized a variety of literary devices to form a unique style of his own – these include conscious archaism, prose-poetic techniques combined with essay-form techniques, alliteration, anaphora, crescendo, transferred epithet, metaphor, symbolism, and colloquialism.

Influence on culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2012) |

Lovecraft was relatively unknown during his own time. While his stories appeared in the pages of prominent pulp magazines such as Weird Tales (eliciting letters of outrage as often as letters of praise from regular readers of the magazines), not many people knew his name. He did, however, correspond regularly with other contemporary writers, such as Clark Ashton Smith and August Derleth, people who became good friends of his, even though they never met in person. This group of writers became known as the "Lovecraft Circle", since they all freely borrowed elements of Lovecraft's stories – the mysterious books with disturbing names, the pantheon of ancient alien entities, such as Cthulhu and Azathoth, and eldritch places, such as the New England town of Arkham and its Miskatonic University – for use in their own works with Lovecraft's encouragement.

After Lovecraft's death, the Lovecraft Circle carried on. August Derleth in particular added to and expanded on Lovecraft's vision. However, Derleth's contributions have been controversial. While Lovecraft never considered his pantheon of alien gods more than a mere plot device, Derleth created an entire cosmology, complete with a war between the good Elder Gods and the evil Outer Gods, such as Cthulhu and his ilk. The forces of good were supposed to have won, locking Cthulhu and others up beneath the earth, in the ocean, and so forth. Derleth's Cthulhu Mythos stories went on to associate different gods with the traditional four elements of fire, air, earth and water—an artificial constraint which required rationalizations on Derleth's part as Lovecraft himself never envisioned such a scheme.

Lovecraft's fiction has been grouped into three categories by some critics. While Lovecraft did not refer to these categories himself, he did once write: "There are my 'Poe' pieces and my 'Dunsany pieces'—but alas—where are any Lovecraft pieces?"[59]

- Macabre stories (c. 1905–1920);

- Dream Cycle stories (c. 1920–1927);

- Cthulhu / Lovecraft Mythos stories (c. 1925–1935).

Lovecraft's writing, particularly the so-called Cthulhu Mythos, has influenced fiction authors including modern horror and fantasy writers. Stephen King, Ramsey Campbell, Bentley Little, Joe R. Lansdale, Alan Moore, Junji Ito, F. Paul Wilson, Brian Lumley, Caitlín R. Kiernan, William S. Burroughs, and Neil Gaiman, have cited Lovecraft as one of their primary influences. Beyond direct adaptation, Lovecraft and his stories have had a profound impact on popular culture. Some influence was direct, as he was a friend, inspiration, and correspondent to many of his contemporaries, such as August Derleth, Robert E. Howard, Robert Bloch and Fritz Leiber. Many later figures were influenced by Lovecraft's works, including author and artist Clive Barker, prolific horror writer Stephen King, comics writers Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman and Mike Mignola, film directors John Carpenter, Stuart Gordon, Guillermo Del Toro and artist H. R. Giger.[60] Japan has also been significantly inspired and terrified by Lovecraft's creations and thus even entered the manga and anime media. Chiaki J. Konaka is an acknowledged disciple and has participated in Cthulhu Mythos, expanding several Japanese versions.[61] He is an anime scriptwriter who tends to add elements of cosmicism, and is credited for spreading the influence of Lovecraft among anime base.[62] Manga artist Junji Ito has also been inspired by Lovecraft.[63][64] Novelist and manga author, Hideyuki Kikuchi, incorporated a number of locations, beings and events from the works of Lovecraft into the manga Taimashin.[65]

Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges wrote his short story "There Are More Things" in memory of Lovecraft. Contemporary French writer Michel Houellebecq wrote a literary biography of Lovecraft called H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life. Prolific American writer Joyce Carol Oates wrote an introduction for a collection of Lovecraft stories. The Library of America published a volume of Lovecraft's work in 2005, essentially declaring him a canonical American writer.[66][67][68] French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari refer to Lovecraft in A Thousand Plateaus, calling the short story "Through the Gates of the Silver Key" one of his masterpieces.[69]

Music

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (July 2015) |

Lovecraft's fictional Mythos has influenced a number of musicians. The psychedelic rock band H. P. Lovecraft (who shortened their name to Lovecraft and then Love Craft in the 1970s) released the albums H. P. Lovecraft and H. P. Lovecraft II in 1967 and 1968 respectively; their titles included "The White Ship". Metallica recorded a song inspired by "The Call of Cthulhu", an instrumental titled "The Call of Ktulu", and another song based on The Shadow Over Innsmouth titled "The Thing That Should Not Be", and another based on Frank Belknap Long's "The Hounds of Tindalos", titled "All Nightmare Long".[70] Black Sabbath's "Behind the Wall of Sleep" appeared on their 1970 debut album and is based on Lovecraft's short story "Beyond the Wall of Sleep". The Darkest of the Hillside Thickets entire repertoire is Lovecraft-based. Melodic death metal band The Black Dahlia Murder produced "Throne of Lunacy" and "Thy Horror Cosmic" based on the Cthulhu Mythos. Progressive metal band Dream Theater's song "The Dark Eternal Night" is based on Lovecraft's story "Nyarlathotep". UK anarcho-punk band Rudimentary Peni make repeated references in their song titles, lyrics and artwork, including in the album Cacophony, all 30 songs of which are inspired by the life and writings of Lovecraft.[71] In the Iron Maiden album Live After Death, the band mascot, Eddie, is rising from a grave inscribed with the name "H. P. Lovecraft" and a quotation from The Nameless City: "That is not dead which can eternal lie yet with strange aeons even death may die." German metal group Mekong Delta made an album called The Music of Erich Zann.

- UK band The Liverpool Scene makes a long reference to ingredients of the "Cthulhu Mythos" in their 1968 sci-fi ode "Universe" on the album "The Amazing Adventures".

- Australian experimental blackened death metal band Portal bases all of their lyrics on Lovecraft's writings.

- German death metal band Morgoth ends their second album "Cursed" (1991) with the song "Darkness". The lyrics consist of these three verses from Lovecraft's "Nemesis": "I have seen the dark universe yawning/ Where the black planets roll without aim,/ Where they roll in their horror unheeded, without knowledge or lustre or name."

- The first track in the Greek symphonic death metal band Septic Flesh's album Communion is titled "Lovecraft's Death".

- Gothic/doom metal band The Vision Bleak dedicated the album Carpathia (2005) to H. P. Lovecraft.

- American doom metal band Catacombs has an album based on Lovecraft titled In the Depths of R'lyeh.

- Danish heavy metal band Mercyful Fate includes "The Mad Arab" on their 1994 album Time and Kutulu (The Mad Arab, Part 2) on their 1996 album Into the Unknown

- Swedish death metal band Paganizer provides a song called "Total Lovecraftian Armageddon" in their album Into The Catacombs.

- Swedish doom metal band Draconian includes a track entitled "Cthulhu Rising" on one of their demos Dark Oceans We Cry

- Other metal bands who use these themes include:

- "Cthulhu Dawn" from Cradle of Filth's 2000 album Midian, and "The Abhorrent" and "Siding with the Titans" from their 2012 album The Manticore and Other Horrors, all make displays of Lovecraftian horror. They also released a compilation album in 2002 called Lovecraft & Witch Hearts. "Mother of Abominations", from their 2004 album, Nymphetamine, is introduced with the repetitive chant, "Ia ia Cthulhu Fhtagn".

- In the electro house genre, producer deadmau5 wrote a song called "Cthulhu Sleeps", which appears on his album 4×4=12.

- Darkwave / dark ambient music duo Nox Arcana released an entire album, Necronomicon, inspired by the Cthulhu mythos.

- British post-punk band The Fall has several Lovecraft-inspired songs, the most direct of which is "Spectre Vs Rector" from the Dragnet album, which contains the chant "Yog-Sothoth, rape me lord".

- UK doom/stoner metal band Electric Wizard have dedicated their whole concept to Lovecraft novels in which the music as well as lyrics have been largely inspired by Lovecraft's novels.

- French Dark Ambient/Industrial/IDM project Flint Glass's 2006 album Nyarlathotep is heavily influenced by the author, with the majority of song titles directly referencing Lovecraft's work.

- On October 12, 2013, a concept album called "Dreams in the Witch House - A Lovecraftian Rock Opera" was released by the H. P. Lovecraft Historical Society. The album is based on Lovecraft's novel "The Dreams in the Witch House" and features (among others) guitarist Bruce Kulick, (Kiss), (Grand Funk Railroad), Doug Blair (W.A.S.P.) and Broadway musical artist Alaine Kashian ("Cats" and the Las Vegas version of "We Will Rock You").

- Arctic Monkeys reference Lovecraft in their 2013 B-side "You're So Dark"

- "Goblin Metal" band Nekrogoblikon based their band name off of goblins and H. P. Lovecraft's "Necronomicon"

- Mention of H. P. Lovecraft also appears in the long-running television series Supernatural. The character Bobby Singer visits a Lovecraft enthusiast, Judah. When he asks about the date that Moishe Campbell visited Lovecraft, Judah tells him about the dinner party Lovecraft held on that day attended by six friends who Judah describes as "co-worshippers in a black magic cult." They perform a ritual to open a door to an alternate dimension. They think it hasn't worked, but each of them die or disappear within a year. Unbeknownst to them, a creature has come through and possesses Lovecraft's maid Eleanor. Only her 9-year-old son Westborough realizes this, and he is not believed but committed to a psychiatric institution.[72]

- The 2008 album Heretic Pride by The Mountain Goats features the song Lovecraft in Brooklyn, which references H. P. Lovecraft's residence in Brooklyn.

Games

Lovecraft has also influenced gaming. Chaosium's role-playing game Call of Cthulhu (currently in its seventh major edition) has been in print for 30 years. The board games Arkham Horror, Eldritch Horror, and dice game Elder Sign are derived from mechanisms first introduced in the Call of Cthulhu RPG. Two collectible card games are Mythos and Call of Cthulhu, the Living Card Game. Several video games are based on or influenced heavily by Lovecraft such as Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth, Quest for Glory IV: Shadows of Darkness, Shadow of the Comet, Prisoner of Ice, Shadowman, Alone in the Dark, Chzo Mythos, Eternal Darkness: Sanity's Requiem, Cthulhu Saves the World, Sherlock Holmes: The Awakened, Amnesia: The Dark Descent, Amnesia: A Machine For Pigs, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, Bloodborne, Dead Space, Terraria, Splatterhouse, Darkness Within: In Pursuit of Loath Nolder, Darkness Within 2: The Dark Lineage, Penumbra, Blood (according to Nick Newhard, its designer), The Last Door, the megami tensei franchise and Quake. The MMORPG The Secret World is heavily based on Lovecraftian lore. In The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim – Dragonborn the Daedric Prince Hermaeus Mora and his realm of Oblivion, Apocrypha, are both heavily influenced by Lovecraft.

In the MMORPG World of WarCraft, the names of the Old Gods and other non-player character names are heavily influenced by H. P. Lovecraft's character names.[73]

The board game The Doom that Came to Atlantic City created by Lee Moyer and Keith Baker is a game of Lovecraftian Great Old Ones fighting to destroy Atlantic City. With playing pieces by sculptor Paul Komoda, the game is currently in production through Cryptozoic Entertainment.[74]

Lovecraft as a character in fiction

Aside from his thinly veiled appearance in Robert Bloch's "The Shambler from the Stars", Lovecraft continues to be used as a character in supernatural fiction. An early version of Ray Bradbury's "The Exiles"[75] uses Lovecraft as a character, who makes a brief, 600-word appearance eating ice cream in front of a fire and complaining about how cold he is. Lovecraft and some associates are included at length in Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea's The Illuminatus! Trilogy (1975). Lovecraft makes an appearance as a rotting corpse in The Chinatown Death Cloud Peril by Paul Malmont, a novel with fictionalized versions of a number of period writers.

Other notable works with Lovecraft as a character include Richard Lupoff's Lovecraft's Book (1985), Cast a Deadly Spell (1991), H.P. Lovecraft's: Necronomicon (1993), Witch Hunt (1994), Out of Mind: The Stories of H.P. Lovecraft (1998) and Stargate SG-1: Roswell (2007). Lovecraft also appears in the Season 6, Episode 21 episode "Let it Bleed" of the TV show Supernatural. A satirical version of Lovecraft named "H. P. Hatecraft" appeared as a recurring character on the Cartoon Network television series Scooby-Doo! Mystery Incorporated. A character based on Lovecraft also appears in the visual novel Shikkoku no Sharnoth: What a Beautiful Tomorrow, under the name "Howard Phillips" (or "Mr. Howard" to most of the main characters).[citation needed]. Another character based on Lovecraft appears in Afterlife with Archie.[76] He appears as a minor character in Brian Clevinger's comic book series Atomic Robo, as an aquintance and fellow scientist of Nikola Tesla, having been driven insane by his involvement in the Tunguska Event which exposed him to the hidden horrors of the wider universe. He is eventually killed when his body becomes host to an extradimensional being infecting the timestream.[citation needed]

Editions and collections of Lovecraft's work

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2012) |

For most of the 20th century, the definitive editions (specifically At the Mountains of Madness and Other Novels, Dagon and Other Macabre Tales, The Dunwich Horror and Others, and The Horror in the Museum and Other Revisions) of his prose fiction were published by Arkham House, a publisher originally started with the intent of publishing the work of Lovecraft, but which has since published a considerable amount of other literature as well. Penguin Classics has at present issued three volumes of Lovecraft's works: The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories, The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories, and most recently The Dreams in the Witch House and Other Weird Stories. They collect the standard texts as edited by S. T. Joshi, most of which were available in the Arkham House editions, with the exception of the restored text of "The Shadow Out of Time" from The Dreams in the Witch House, which had been previously released by small-press publisher Hippocampus Press. In 2005 the prestigious Library of America canonized Lovecraft with a volume of his stories edited by Peter Straub, and Random House's Modern Library line have issued the "definitive edition" of Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness (also including "Supernatural Horror in Literature").

Lovecraft's poetry is collected in The Ancient Track: The Complete Poetical Works of H. P. Lovecraft (Night Shade Books, 2001), while much of his juvenilia, various essays on philosophical, political and literary topics, antiquarian travelogues, and other things, can be found in Miscellaneous Writings (Arkham House, 1989). Lovecraft's essay "Supernatural Horror in Literature", first published in 1927, is a historical survey of horror literature available with endnotes as The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature.

Letters

Although Lovecraft is known mostly for his works of weird fiction, the bulk of his writing consists of voluminous letters about a variety of topics, from weird fiction and art criticism to politics and history. Lovecraft's biographer L. Sprague de Camp estimates that Lovecraft wrote 100,000 letters in his lifetime, a fifth of which are believed to survive.

He sometimes dated his letters 200 years before the current date, which would have put the writing back in U.S. colonial times, before the American Revolution (a war that offended his Anglophilia). He explained that he thought that the 18th and 20th centuries were the "best", the former being a period of noble grace, and the latter a century of science.

Lovecraft was not an active letter-writer in youth. In 1931 he admitted: "In youth I scarcely did any letter-writing — thanking anybody for a present was so much of an ordeal that I would rather have written a two hundred fifty-line pastoral or a twenty-page treatise on the rings of Saturn." (SL 3.369–70). The initial interest in letters stemmed from his correspondence with his cousin Phillips Gamwell but even more important was his involvement in the amateur journalism movement, which was initially responsible for the enormous number of letters Lovecraft produced.

Despite his light letter-writing in youth, in later life his correspondence was so voluminous that it has been estimated that he may have written around 30,000 letters to various correspondents, a figure which places him second only to Voltaire as an epistolarian. Lovecraft's later correspondence is primarily to fellow weird fiction writers, rather than to the amateur journalist friends of his earlier years.

Lovecraft clearly states that his contact to numerous different people through letter-writing was one of the main factors in broadening his view of the world: "I found myself opened up to dozens of points of view which would otherwise never have occurred to me. My understanding and sympathies were enlarged, and many of my social, political, and economic views were modified as a consequence of increased knowledge." (SL 4.389).

Today there are five publishing houses that have released letters from Lovecraft, most prominently Arkham House with its five-volume edition Selected Letters. (Those volumes, however, severely abridge the letters they contain). Other publishers are Hippocampus Press (Letters to Alfred Galpin et al.), Night Shade Books (Mysteries of Time and Spirit: The Letters of H. P. Lovecraft and Donald Wandrei et al..), Necronomicon Press (Letters to Samuel Loveman and Vincent Starrett et al.), and University of Tampa Press (O Fortunate Floridian: H. P. Lovecraft's Letters to R. H. Barlow). S.T. Joshi is supervising an ongoing series of volumes collecting Lovecraft's unabridged letters to particular correspondents.

"Lord of a Visible World: An Autobiography in Letters" was published in 2000, in which his letters are arranged according to themes, such as adolescence and travel.

Copyright

There is controversy over the copyright status of many of Lovecraft's works, especially his later works. Lovecraft had specified that the young R. H. Barlow would serve as executor of his literary estate,[77] but these instructions had not been incorporated into his will. Nevertheless his surviving aunt carried out his expressed wishes, and Barlow was given charge of the massive and complex literary estate upon Lovecraft's death.

Barlow deposited the bulk of the papers, including the voluminous correspondence, with the John Hay Library, and attempted to organize and maintain Lovecraft's other writing. August Derleth, an older and more established writer than Barlow, vied for control of the literary estate. One result of these conflicts was the legal confusion over who owned what copyrights.

All works published before 1923 are public domain in the U.S.[78] However, there is some disagreement over who exactly owns or owned the copyrights and whether the copyrights apply to the majority of Lovecraft's works published post-1923.

Questions center over whether copyrights for Lovecraft's works were ever renewed under the terms of the United States Copyright Act of 1976 for works created prior to January 1, 1978. The problem comes from the fact that before the Copyright Act of 1976 the number of years a work was copyrighted in the U.S. was based on publication rather than life of the author plus a certain number of years and that it was good for only 28 years. After that point, a new copyright had to be filed, and any work that did not have its copyright renewed fell into the public domain. The Copyright Act of 1976 retroactively extended this renewal period for all works to a period of 47 years[79] and the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998 added another 20 years to that, for a total of 95 years from publication. If the works were renewed, the copyrights would still be valid in the United States.

The European Union Copyright Duration Directive of 1993 extended the copyrights to 70 years after the author's death. So, all works of Lovecraft published during his lifetime, became public domain in all 27 European Union countries on January 1, 2008. In those Berne Convention countries who have implemented only the minimum copyright period, copyright expires 50 years after the author's death.

Lovecraft protégés and part owners of Arkham House, August Derleth and Donald Wandrei, often claimed copyrights over Lovecraft's works. On October 9, 1947, Derleth purchased all rights to Weird Tales. However, since April 1926 at the latest, Lovecraft had reserved all second printing rights to stories published in Weird Tales. Hence, Weird Tales may only have owned the rights to at most six of Lovecraft's tales. Again, even if Derleth did obtain the copyrights to Lovecraft's tales, no evidence as yet has been found that the copyrights were renewed.[80] Following Derleth's death in 1971, his attorney proclaimed that all of Lovecraft's literary material was part of the Derleth estate and that it would be "[protected] to the fullest extent possible."[81]

S. T. Joshi concludes in his biography, H. P. Lovecraft: A Life, that Derleth's claims are "almost certainly fictitious" and that most of Lovecraft's works published in the amateur press are most likely now in the public domain. The copyright for Lovecraft's works would have been inherited by the only surviving heir of his 1912 will: Lovecraft's aunt, Annie Gamwell. Gamwell herself perished in 1941 and the copyrights then passed to her remaining descendants, Ethel Phillips Morrish and Edna Lewis. Morrish and Lewis then signed a document, sometimes referred to as the Morrish-Lewis gift, permitting Arkham House to republish Lovecraft's works but retaining the copyrights for themselves. Searches of the Library of Congress have failed to find any evidence that these copyrights were then renewed after the 28-year period and hence, it is likely that these works are now in the public domain.

Chaosium, publishers of the Call of Cthulhu role-playing game, have a trademark on the phrase "The Call of Cthulhu" for use in game products. TSR, Inc., original publisher of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game, included a section on the Cthulhu Mythos in one of the game's earlier supplements, Deities & Demigods (originally published in 1980 and later renamed to "Legends & Lore"). TSR later agreed to remove this section at Chaosium's request.[citation needed]

In 2009, the H. P. Lovecraft Literary Estate established Lovecraft Holdings, LLC, a company based out of Providence, which has filed trademark claims for Lovecraft's name and silhouette,[82] and also claims ownership over Lovecraft's stories, letters, and essays.

Regardless of the legal disagreements surrounding Lovecraft's works, Lovecraft himself was extremely generous with his own works and encouraged others to borrow ideas from his stories and build on them, particularly with regard to his Cthulhu Mythos. He encouraged other writers to reference his creations, such as the Necronomicon, Cthulhu and Yog-Sothoth. After his death, many writers have contributed stories and enriched the shared mythology of the Cthulhu Mythos, as well as making numerous references to his work.

Locations featured in Lovecraft stories

Lovecraft drew extensively from his native New England for settings in his fiction. Numerous real historical locations are mentioned, and several fictional New England locations make frequent appearances.

Historical

- Pascoag, Rhode Island, in "The Horror at Red Hook".

- Chepachet, Rhode Island, in "The Horror at Red Hook".

- Binger, Caddo County, Oklahoma, in "The Mound".

- Copp's Hill, Boston, Massachusetts

- Red Line

- Pawtuxet (now Cranston, Rhode Island).

- Newburyport, Massachusetts

- Ipswich, Massachusetts

- Dunedin, New Zealand

- Ayer, Massachusetts

- Bolton, Massachusetts

- Salem, Massachusetts

- Brattleboro, Vermont

- Albany, New York

- Many locations within his hometown of Providence, Rhode Island, including the (then purportedly haunted) Halsey House, Prospect Terrace and Brown University's John Hay Library and John Carter Brown Library.

- Danvers State Hospital, in Danvers, Massachusetts, which is largely believed to have served as inspiration for the infamous Arkham sanatorium from "The Thing on the Doorstep".

- Catskill Mountains, New York.

- New York City, New York.

- Mainalo Mountain, Arcadia, Greece.

- Tegea, Arcadia, Greece.

- Kilderry, Ireland.

- Nome, Alaska

- Noatak, Alaska

- Fort Morton, Alaska, in "The Horror in the Museum".

- New Orleans, Louisiana (and a mention of Tulane University) in "The Call of Cthulhu".

- Newport, Rhode Island

- Paterson, New Jersey, in "The Call of Cthulhu".

- Mammoth Cave, Kentucky, in "The Beast in the Cave".

- Oslo, Norway, in "The Call of Cthulhu".

Fictional locations

- Miskatonic University in the fictional Arkham, Massachusetts.

- Dunwich, Massachusetts.

- Innsmouth, Massachusetts.

- Kingsport, Massachusetts.

- Aylesbury, Massachusetts.

- Martin's Beach

- The Miskatonic River.

- The fictional Central University Library at the real University of Buenos Aires in Buenos Aires, Argentina. According to Lovecraft, there is a copy of the Necronomicon here, but the University of Buenos Aires has never had a "central" library.

Bibliography

Documentary video and audio biographies

- Lovecraft: Fear of the Unknown (2008).

- Weird Tales: The Strange Life of H.P. Lovecraft, BBC Radio 3, December 3, 2006.[83]

Notes

- ^ "Lovecraft". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Joshi, S. T. (September 2003). "Introduction". The Weird Tale. Wildside Press. ISBN 978-0-8095-3123-3.

- ^ a b Joshi, Schultz 2001, p. xiii

- ^ The Dream World of H. P. Lovecraft, Donald Tyson, Chapter 1 'Silver Spoon' page 18

- ^ http://www.esotericorderofdagon.org/cults_of_cthulhu.pdf

- ^ The Dream World of H. P. Lovecraft, Donald Tyson, Chapter 1 'Silver Spoon'

- ^ Joshi 1996, p. 14

- ^ The Dream World of H. P. Lovecraft - Page 25

- ^ "H.P. Lovecraft Biography". biography.com. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c Ronan, Margaret, Forward to The Shadow Over Innsmouth and Other Stories of Horror, Scholastic Book Services, 1971

- ^ Murrary, Will (1991). "Lovecraft and the Pulp Magazine Tradition". In Schultz, David E.; Joshi, S. T. (eds.). An Epicure in the Terrible: A Centennial Anthology of Essays in Honor of H.P. Lovecraft. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-8386-3415-X. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Weinstock, J.R., in Forward to The Call of Cthulhu and Other Dark Tales (2009) Barnes and Noble, page X

- ^ Joshi, Schultz 2001, p. xv

- ^ a b c d de Camp, L Sprague. Lovecraft: a Biography.

- ^ The Dream World of H. P. Lovecraft: His Life, His Demons, His Universe (2010) - Donald Tyson ISBN 9780738728292

- ^ S. T. Joshi; David E. Schultz, eds. (2001). "Weiss, Henry George". An H.P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-313-31578-7.

- ^ Donald Tyson (November 1, 2010). The Dream World of H. P. Lovecraft. Llewellyn Worldwide. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7387-2829-2.

- ^ a b c Michel Houellebecq. H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life. San Francisco: Believer Books, 2005.

- ^ S. T. Joshi (2001). A Dreamer and a Visionary: H.P. Lovecraft in His Time. Liverpool University Press. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-0-85323-946-8.

- ^ An H.P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia, edited by S. T. Joshi, David E. Schultz, page 117

- ^ James Arthur Anderson (September 30, 2014). "Charles Dexter Ward". Out of the Shadows: A Structuralist Approach to Understanding the Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft. Wildside Press LLC. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-4794-0384-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Joshi, S. T. (2001). A Dreamer and a Visionary: H.P. Lovecraft in His Time. Liverpool University Press. pp. 95, 97, 111, 221–222, 359–360. ISBN 978-0-85323-946-8. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Bilow, Michael (July 27, 2013). "We are Providence: The H.P. Lovecraft Community". Motif Magazine. Providence, Rhode Island. Retrieved August 4, 2013.

- ^ Joyce Carol Oates (October 31, 1996). "The King of Weird". The New York Review of Books. 43 (17). Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Wohleber, Curt (December 1995). "The Man Who Can Scare Stephen King". American Heritage. 46 (8). Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre, Del Rey Books, 1982, front cover.

- ^ King, Stephen (February 1987). Danse Macabre. Berkley. p. 63. ISBN 9-780-42510-433-0. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Michael Saler (2011). As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199887802., note no. 66

- ^ LA Review of Books, April 6, 2013 Let’s Get Weird

- ^ Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy (2013) Graham Harman

- ^ ASK/TELL, October 23, 2011 Interview with Graham Harman

- ^ New Critical Essays on H.P. Lovecraft,(2013)Chapter nine

- ^ H. P. Lovecraft Letter to Farnsworth Wrigth (July 27, 1927), in Selected Letters 1925–1929 (Sauk City, Wisconsin: Arkham House, 1968), p.150.

- ^ a b Burleson, Donald R. (1991). "On Lovecraft's Themes: Touching the Glass". In Schultz, David E.; Joshi, S. T. (eds.). An Epicure in the Terrible: A Centennial Anthology of Essays in Honor of H.P. Lovecraft. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 135–147. ISBN 0-8386-3415-X. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Dziemianowicz, Stefan (1991). "Outsiders and Aliens: The Uses of Isolation in Lovecraft's Fiction". In Schultz, David E.; Joshi, S. T. (eds.). An Epicure in the Terrible: A Centennial Anthology of Essays in Honor of H.P. Lovecraft. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 159–187. ISBN 0-8386-3415-X. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ a b Hambly, Barbara (1996). Introduction: The Man Who Loved His Craft. The Random House Publishing Group. p. viii. ISBN 0-345-38422-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Burleson, Donald (1990). Lovecraft: Disturbing the Universe. the University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1728-3.

- ^ Schweitzer, Darrell (2001). Discovering H. P. Lovecraft. Borgo Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-58715-471-3.

- ^ Price, Robert M. (1991). Introduction:The New Lovecraft Circle. Random House Publishing. ISBN 0-345-44406-X.

- ^ St. Armand, Barton Levi (1991). "Synchronistic Worlds: Lovecraft and Borges". In Schultz, David E.; Joshi, S. T. (eds.). An Epicure in the Terrible: A Centennial Anthology of Essays in Honor of H.P. Lovecraft. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 319–320. ISBN 0-8386-3415-X. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ S. T. Joshi, H. P. Lovecraft: Decline of the West, (Starmont Studies in Literary Criticism, No. 37), Borgo Pr, 1991, ISBN 978-1-55742-208-8.

- ^ China Miéville's introduction to "At the Mountains of Madness", Modern Library Classics, 2005

- ^ Joshi 1996, p. 38

- ^ a b c d e f g Joshi, S. T. (1996). A Subtler Magick: The Writings and Philosophy of H. P. Lovecraft. Borgo Press. pp. 22, 41–42, 76–77, 107–108, 162, 229, 230. ISBN 1-880448-61-0.

- ^ a b c d e Steiner, Bernd (2005). H. P. Lovecraft and the Literature of the fantastic: explorations in a Literary Genre. GRIN Verlag. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-3-638-84462-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Tyson, Donald (2010). The Dream World of H. P. Lovecraft: His Life, His Demons, His Universe. Llewellyn Publications. pp. 5–6, 57–59. ISBN 978-0-7387-2284-9.

- ^ Lovecraft, "Cool Air", pp. 201–202.

- ^ David Punter, (1996), The Literature of Terror: A History of Gothic Fictions from 1765 to the Present Day, Vol. I, 'Modern Gothic", p. 40.

- ^ Bloch, Robert (1982). Introduction: Heritage of Horror. The Random House Publishing Group. p. xii. ISBN 0-345-38422-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Mieville, China (2005). Introduction. The Random House Publishing Group. p. xvii–xx. ISBN 0-8129-7441-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Schweitzer, Darrell (1998). Windows of the Imagination. Wildside Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 1-880448-60-2.

- ^ Schwader, Ann (2004). Mail Order Bride. Lindisfarne Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-9740297-5-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu", p. 151.

- ^ H. P. Lovecraft Letter to Robert E. Howard (August 16, 1932), in Selected Letters 1932–1934 (Sauk City, Wisconsin: Arkham House, 1976), p.57."

- ^ "Lovecraft's Shadow Over Innsmouth". Donovan K. Loucks.

- ^ "Lovecraft's Nemesis". Donovan K. Loucks.

- ^ Poe, Edgar Allan. . – via Wikisource.

- ^ Lovecraft, H. P. (1938) [Written 1927]. . Supernatural Horror in Literature – via Wikisource.

The well-nigh endless array of Mr. Blackwood's fiction includes both novels and shorter tales... Foremost of all must be reckoned The Willows... Here art and restraint in narrative reach their very highest development, and an impression of lasting poignancy is produced without a, [sic] single strained passage or a single false note.

- ^ Letter to Elizabeth Toldridge, March 8, 1929, quoted in Lovecraft: A Look Behind the Cthulhu Mythos

- ^ Giger, Hansruedi (2005): Necronomicon I & II. Erftstadt: Area.

- ^ "Ask John: Is There Any Lovecraftian Anime?". AnimeNation. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ^ Bush, Laurence (2001). Asian Horror Encyclopedia. Writers Club Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 0-595-20181-4.

- ^ Ito, Junji (October 2007) [1998]. Uzumaki, Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Viz Media. p. 207. ISBN 1-4215-1389-7.

- ^ Mira Bai Winsby (March 2006). "Into the Spiral: A Conversation with Japanese Horror Maestro Junji Ito". 78 Magazine. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ "TAIMASHIN: Vol. 1 Hideyuki Kikuchi, Author, Misaki Saitoh, Illustrator". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ^ H. P. Lovecraft. "H.P Lovecraft: Tales (The Library of America)". Loa.org. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ "The Horror, the Horror!". The Weekly Standard. March 7, 2005. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ Kenney, Michael (February 15, 2005). "The Library of America scares up a collection of Lovecraft's local lore — The Boston Globe". Boston.com. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ Deleuze, Gilles & Guattari, Félix (translated by Brian Massumi). A Thousand Plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993, p. 240, 539

- ^ "CANOE – JAM! Music – Artists – Metallica: Interview with James Hetfield". Jam.canoe.ca. December 8, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ "Rudimentary Peni: Cacophony". Deathrock.com. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ "H.P. Lovecraft". supernaturalwiki.com.

- ^ Old Gods - Wowpedia - Your wiki guide to the World of Warcraft. Wowpedia. Retrieved on 2014-04-12.

- ^ The Doom That Came to Atlantic City | Cryptozoic Entertainment. Cryptozoic.com. Retrieved on 2014-04-12.

- ^ Published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Volume 1 No. 2 (Winter-Spring 1950), and later to become part of Bradbury's Martian Chronicles

- ^ Sullivan, Justin (July 22, 2014). "'Afterlife With Archie': Sabrina the Teenage Witch returns". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Joshi, Schultz 2001, p. 16

- ^ How to Investigate the Copyright Status of a Work- U.S. Copyright Office

- ^ Copyright Basics by Terry Carroll 1994

- ^ William, Johns. "Copyright". Archived from the original on October 3, 2003. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Karr, Chris J. "The Black Seas of Copyright: Arkham House Publishers and the H.P. Lovecraft Copyrights". Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- ^ "Lovecraft Holdings, LLC Trademarks". Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- ^ "BBC - (none) - Sunday Feature - Weird Tales: The Strange Life of H P Lovecraft". bbc.co.uk.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 30 (help)

References

- Dziemianowicz, Stefan (July 12, 2010), "Terror Eternal: The enduring popularity of H. P. Lovecraft", Publishers Weekly

- Extract from H P Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life by Michel Houellebecq

- "H. P. Lovecraft's Afterlife" by John J. Miller of the Wall Street Journal

- Michael Saler (2011). As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199887802.

- Sante, Luc (October 19, 2006), "The Heroic Nerd", The New York Review of Books, vol. 53, no. 16, New York, p. 37

- Joshi, S. T. (1996). A Subtler Magick: The Writings and Philosophy of H. P. Lovecraft (3rd ed.). Wildside Press LLC. ISBN 1-880448-61-0.

- Joshi, S. T.; Schultz, David E. (2001). An H. P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Further reading

- Anderson, James Arthur. Out of the Shadows: A Structuralist Approach to Understanding the Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft (ISBN 978-0-8095-3002-1) A close reading of Lovecraft's fiction. The Milford Series, Popular Writers of Today, Vol. 75; Wildside Press, 2011.

- Burleson, Donald R. Lovecraft: Disturbing the Universe (ISBN 0-8131-1728-3) This book is the only volume to date analyzing Lovecraft's literature from a deconstructionist standpoint. University Press of Kentucky, November 1990.

- Carter, Lin. Lovecraft: A Look Behind the Cthulhu Mythos (ISBN 0-586-04166-4), is a survey of Lovecraft's work (along with that of other members of the Lovecraft Circle) with considerable information on his life.

- De Camp, L. Sprague Lovecraft: A Biography (ISBN 0-345-25115-6) The first full-length biography, published in 1975, now out of print. It reflected the state of scholarship at the time but is now completely superseded by S.T. Joshi's biography I Am Providence.

- Eddy, Muriel and C. M. Eddy, Jr. The Gentleman From Angell Street: Memories of H. P. Lovecraft (ISBN 978-0-9701699-1-4), is a collection of personal remembrances and anecdotes from two of Lovecraft's closest friends in Providence. The Eddys were fellow writers, and Mr. Eddy was a frequent contributor to Weird Tales.

- Hill, Gary. The Strange Sound of Cthulhu: Music Inspired by the Writings of H. P. Lovecraft (ISBN 978-1-84728-776-2).

- Joshi, S. T. H. P. Lovecraft: A Life (ISBN 0-940884-88-7) The most complete and authoritative biography of Lovecraft, later abridged as A Dreamer & a Visionary: H. P. Lovecraft in His Time (ISBN 0-85323-946-0). An unabridged reprint in two volumes of Joshi's biography, newly retitled I Am Providence, was published in 2010 by Hippocampus Press.

- Joshi S. T. The Rise and Fall of the Cthulhu Mythos (Mythos Books, 2008) is the first full-length critical study since Lin Carter's to examine the development of Lovecraft's Mythos and its outworking in the oeuvres of various modern writers.

- Joshi, S. T. "H. P. Lovecraft: Alone in Space," chapter 3 in Emperors of Dreams: Some Notes on Weird Poetry by S. T. Joshi (Sydney: P'rea Press, 2008: ISBN 978-0-9804625-3-1 (pbk) and ISBN 978-0-9804625-4-8 (hbk)), discusses some of Lovecraft's weird poetry.

- Long, Frank Belknap Howard Phillips Lovecraft: Dreamer on the Nightside (Arkham House, 1975, ISBN 0-87054-068-8) Presents a personal look at Lovecraft's life, combining reminiscence, biography and literary criticism. Long was a friend and correspondent of Lovecraft, as well as a fellow fantasist who wrote a number of Lovecraft-influenced Cthulhu Mythos stories (including The Hounds of Tindalos).

- An English translation of Michel Houellebecq's H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life (ISBN 1-932416-18-8) was published by Believer Books in 2005.

- Ludueña, Fabián, H.P. Lovecraft. The Disjunction in Being (translation and epilogue by Alejandro de Acosta), New York, Schism, 2015 (ISBN 978-1505866001). A study of Lovecraft's conceptions about philosophy and literature.

- Other significant Lovecraft-related works are An H. P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia by Joshi and David S. Schulz; Lovecraft's Library: A Catalogue (a meticulous listing of many of the books in Lovecraft's now scattered library), by Joshi; Lovecraft at Last, an account by Willis Conover of his teenage correspondence with Lovecraft; Joshi's A Subtler Magick: The Writings and Philosophy of H. P. Lovecraft.

- Andrew Migliore and John Strysik's Lurker in the Lobby: The Guide to the Cinema of H. P. Lovecraft and Charles P. Mitchell's The Complete H. P. Lovecraft Filmography both discuss films containing Lovecraftian elements.

- Lovecraft's prose fiction being published as corrected texts were released by Arkham House in the 1980s, and many other collections of his stories have appeared, including Ballantine Books editions and three Del Rey editions. The three collections published by Penguin, The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories, The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories, and The Dreams in the Witch House and Other Weird Stories, incorporate the modifications made in the corrected texts as well as the annotations provided by Joshi.

- Lovecraft's ghost-written works are compiled in The Horror in the Museum and Other Revisions, edited again by Joshi.

- Some of Lovecraft's writings are annotated with footnotes or endnotes. In addition to the Penguin editions mentioned above and The Annotated Supernatural Horror in Literature, Joshi has produced The Annotated H. P. Lovecraft as well as More Annotated H. P. Lovecraft, both of which are footnoted extensively.

- An Epicure in the Terrible (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1991), edited by David E. Schultz and S. T. Joshi is an anthology of 13 essays on Lovecraft (excluding Joshi's lengthy introduction) on the centennial of Lovecraft's birth. The essays are arranged into 3 sections; Biographical, Thematic Studies and Comparative and Genre Studies. The authors include S. T. Joshi, Kenneth W. Faig, Jr, Jason C. Eckhardt, Will Murray, Donald R. Burleson, Peter Cannon, Stefan Dziemianowicz, Steven J. Mariconda, David E. Schultz, Robert H. Waugh, Robert M. Price, R. Boerem, Norman R. Gatford and Barton Levi St. Armand.

- The Intersection of Fantasy and Native America: From H. P. Lovecraft to Leslie Marmon Silko edited by Amy H. Sturgis and David D. Oberhelman (Mythopoeic Press, 2009: ISBN 978-1-887726-12-2).

External links

- The H. P. Lovecraft Archive

- Howard P. Lovecraft Collection in the Special Collections at the John Hay Library (Brown University).

- The H. P. Lovecraft Historical Society

- Works by H. P. Lovecraft at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about H. P. Lovecraft at Internet Archive

- Works by H. P. Lovecraft at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The eBook Lovecraft Collection

- H. P. Lovecraft at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Howard Phillips Lovecraft by S. T. Joshi at The Scriptorium (themodernword.com)

- The H. P. Lovecraft Film Festival and CthulhuCon

- A Virtual Walking Tour of Lovecraft's Providence