U.S. state

| U.S. states | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Category | Federated state |

| Location | |

| Number | 50 |

| Populations | 584,153 (Wyoming) – 38,802,500 (California)[1] |

| Areas | 1,214 square miles (3,140 km2) (Rhode Island) – 663,268 square miles (1,717,860 km2) (Alaska)[2] |

| Government | |

| Subdivisions |

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Political divisions of the United States |

|---|

|

| First level |

|

|

| Second level |

|

| Third level |

|

|

| Fourth level |

| Other areas |

|

|

|

United States portal |

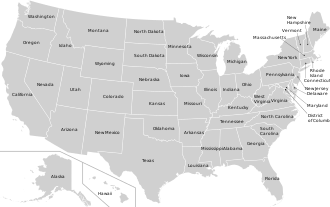

A state of the United States of America is one of the 50 constituent political entities that shares its sovereignty with the United States federal government. Due to the shared sovereignty between each state and the federal government, Americans are citizens of both the federal republic and of the state in which they reside.[3] State citizenship and residency are flexible and no government approval is required to move between states, except for persons covered by certain types of court orders (e.g., paroled convicts and children of divorced spouses who are sharing custody).

States range in population from just under 600,000 (Wyoming) to over 38 million (California), and in area from 1,214 square miles (3,140 km2) (Rhode Island) to 663,268 square miles (1,717,860 km2) (Alaska). Four states use the term commonwealth rather than state in their full official names.

State governments are allocated power by the people (of each respective state) through an individualized written constitution, which each state has adopted. All are required to be grounded in republican principles, and each provides for a government, consisting of three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial.[4] States are divided into counties or county-equivalents, which may be assigned some local governmental authority but are not sovereign. County or county-equivalent structure varies widely by state.

States possess a number of powers and rights under the United States Constitution; among them ratifying constitutional amendments. Historically, the tasks of local law enforcement, public education, public health, regulating intrastate commerce, and local transportation and infrastructure have generally been considered primarily state responsibilities, although all of these now have significant federal funding and regulation as well. Over time, the U.S. Constitution has been amended, and the interpretation and application of its provisions have changed. The general tendency has been toward centralization and incorporation, with the federal government playing a much larger role than it once did. There is a continuing debate over states' rights, which concerns the extent and nature of the states' powers and sovereignty in relation to the federal government and the rights of individuals.

States and their residents are represented in the federal Congress, a bicameral legislature consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. Each state is represented by two Senators, and at least one Representative, while additional representatives are distributed among the states in proportion to the most recent constitutionally mandated decennial census.[5] Each state is also entitled to select a number of electors to vote in the Electoral College, the body that elects the President of the United States, equal to the total of Representatives and Senators from that state.[6]

The Constitution grants to Congress[7] the authority to admit new states into the Union. Since the establishment of the United States in 1776, the number of states has expanded from the original 13 to 50. Alaska and Hawaii are the most recent states admitted, both in 1959.

The Constitution is silent on the question of whether states have the power to secede (withdraw from) from the Union. Shortly after the Civil War, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Texas v. White, held that a state cannot unilaterally do so.[8][9]

States of the United States

The 50 U.S. states (in alphabetical order), along with state flag and date each joined the union:

![]() Alabama • December 14, 1819

Alabama • December 14, 1819

![]() Alaska • January 3, 1959

Alaska • January 3, 1959

![]() Arizona • February 14, 1912

Arizona • February 14, 1912

![]() Arkansas • June 15, 1836

Arkansas • June 15, 1836

![]() California • September 9, 1850

California • September 9, 1850

![]() Colorado • August 1, 1876

Colorado • August 1, 1876

![]() Connecticut • January 9, 1788

Connecticut • January 9, 1788

![]() Delaware • December 7, 1787

Delaware • December 7, 1787

![]() Florida • March 3, 1845

Florida • March 3, 1845

![]() Georgia • January 2, 1788

Georgia • January 2, 1788

![]() Hawaii • August 21, 1959

Hawaii • August 21, 1959

![]() Idaho • July 3, 1890

Idaho • July 3, 1890

![]() Illinois • December 3, 1818

Illinois • December 3, 1818

![]() Indiana • December 11, 1816

Indiana • December 11, 1816

![]() Iowa • December 28, 1846

Iowa • December 28, 1846

![]() Kansas • January 29, 1861

Kansas • January 29, 1861

![]() Kentucky • June 1, 1792

Kentucky • June 1, 1792

![]() Louisiana • April 30, 1812

Louisiana • April 30, 1812

![]() Maine • March 15, 1820

Maine • March 15, 1820

![]() Maryland • April 28, 1788

Maryland • April 28, 1788

![]() Massachusetts • February 6, 1788

Massachusetts • February 6, 1788

![]() Michigan • January 26, 1837

Michigan • January 26, 1837

![]() Minnesota • May 11, 1858

Minnesota • May 11, 1858

![]() Mississippi • December 10, 1817

Mississippi • December 10, 1817

![]() Missouri • August 10, 1821

Missouri • August 10, 1821

![]() Montana • November 8, 1889

Montana • November 8, 1889

![]() Nebraska • March 1, 1867

Nebraska • March 1, 1867

![]() Nevada • October 31, 1864

Nevada • October 31, 1864

![]() New Hampshire • June 21, 1788

New Hampshire • June 21, 1788

![]() New Jersey • December 18, 1787

New Jersey • December 18, 1787

![]() New Mexico • January 6, 1912

New Mexico • January 6, 1912

![]() New York • July 26, 1788

New York • July 26, 1788

![]() North Carolina • November 21, 1789

North Carolina • November 21, 1789

![]() North Dakota • November 2, 1889

North Dakota • November 2, 1889

![]() Ohio • March 1, 1803

Ohio • March 1, 1803

![]() Oklahoma • November 16, 1907

Oklahoma • November 16, 1907

![]() Oregon • February 14, 1859

Oregon • February 14, 1859

![]() Pennsylvania • December 12, 1787

Pennsylvania • December 12, 1787

![]() Rhode Island • May 29, 1790

Rhode Island • May 29, 1790

![]() South Carolina • May 23, 1788

South Carolina • May 23, 1788

![]() South Dakota • November 2, 1889

South Dakota • November 2, 1889

![]() Tennessee • June 1, 1796

Tennessee • June 1, 1796

![]() Texas • December 29, 1845

Texas • December 29, 1845

![]() Utah • January 4, 1896

Utah • January 4, 1896

![]() Vermont • March 4, 1791

Vermont • March 4, 1791

![]() Virginia • June 25, 1788

Virginia • June 25, 1788

![]() Washington • November 11, 1889

Washington • November 11, 1889

![]() West Virginia • June 20, 1863

West Virginia • June 20, 1863

![]() Wisconsin • May 29, 1848

Wisconsin • May 29, 1848

![]() Wyoming • July 10, 1890

Wyoming • July 10, 1890

Governments

As each state is itself a sovereign entity, it reserves the right to organize its individual government in any way (within the broad parameters set by the U.S. Constitution) deemed appropriate by its people. As a result, while the governments of the various states share many similar features, they often vary greatly with regard to form and substance. No two state governments are identical.

Constitutions

The government of each state is structured in accordance with its individual constitution. In practice, each state has adopted a three-branch system of government, modeled after the federal government, and consisting of three branches (although the three-branch structure is not required): executive, legislative, and judicial.[10][11]

Executive

In each state, the chief executive is called the governor, who serves as both head of state and head of government. The governor may approve or veto bills passed by the state legislature, as well as push for the passage of bills supported by the party of the Governor. In 43 states, governors have line item veto power.[12]

Most states have a "plural executive" in which two or more members of the executive branch are elected directly by the people. Such additional elected officials serve as members of the executive branch, but are not beholden to the governor and the governor cannot dismiss them. For example, the attorney general is elected, rather than appointed, in 43 of the 50 U.S. states.

Legislative

The legislatures of 49 of the 50 states are made up of two chambers: a lower house (termed the House of Representatives, State Assembly, General Assembly or House of Delegates) and a smaller upper house, always termed the Senate. The exception is the unicameral Nebraska Legislature, which is composed of only a single chamber.

Most states have part-time legislatures, while six of the most populated states have full-time legislatures. However, several states with high population have short legislative sessions, including Texas and Florida.[13]

In Baker v. Carr (1962) and Reynolds v. Sims (1964), the U.S. Supreme Court held that all states are required to elect their legislatures in such a way as to afford each citizen the same degree of representation (the one person, one vote standard). In practice, most states choose to elect legislators from single-member districts, each of which has approximately the same population. Some states, such as Maryland and Vermont, divide the state into single- and multi-member districts, in which case multi-member districts must have proportionately larger populations, e.g., a district electing two representatives must have approximately twice the population of a district electing just one. If the governor vetoes legislation, all legislatures may override it, usually, but not always, requiring a two-thirds majority.

In 2013, there were a total of 7,383 legislators in the 50 state legislative bodies. They earned from $0 annually (New Mexico) to $90,526 (California). There were various per diem and mileage compensation.[14]

Judicial

States can also organize their judicial systems differently from the federal judiciary, as long as they protect the federal constitutional right of their citizens to procedural due process. Most have a trial level court, generally called a District Court or Superior Court, a first-level appellate court, generally called a Court of Appeal (or Appeals), and a Supreme Court. However, Oklahoma and Texas have separate highest courts for criminal appeals. In New York State the trial court is called the Supreme Court; appeals are then taken to the Supreme Court's Appellate Division, and from there to the Court of Appeals.

Most states base their legal system on English common law (with substantial indigenous changes and incorporation of certain civil law innovations), with the notable exception of Louisiana, a former French colony, which draws large parts of its legal system from French civil law.

Only a few states choose to have the judges on the state's courts serve for life terms. In most of the states the judges, including the justices of the highest court in the state, are either elected or appointed for terms of a limited number of years, and are usually eligible for re-election or reappointment.

Policies

- Property law

- Education

- Estate and inheritance law

- Commerce laws of ownership and exchange

- Banking and credit laws

- Labor law and professional licensure

- Insurance laws

- Family laws

- Morals laws

- Public health and quarantine laws

- Public works laws, including eminent domain

- Building codes

- Corporations law

- Land use laws

- Water and mineral resource laws

- Judiciary and criminal procedure laws

- Electoral laws, including parties

- Civil service laws

Relationships

Among states

Each state admitted to the Union by congress since 1789 has entered it on an equal footing with the original States in all respects.[15] With the growth of states' rights advocacy during the antebellum period, the Supreme Court asserted, in Lessee of Pollard v. Hagan (1845), that the Constitution mandated admission of new states on the basis of equality.[16]

Under Article Four of the United States Constitution, which outlines the relationship between the states, each state is required to give full faith and credit to the acts of each other's legislatures and courts, which is generally held to include the recognition of legal contracts and criminal judgments, and before 1865, slavery status. Regardless of the Full Faith and Credit Clause, some legal arrangements, such as professional licensure and marriages, may be state-specific, and until recently states have not been found by the courts to be required to honor such arrangements from other states.[17]

Such legal acts are nevertheless often recognized state-to-state according to the common practice of comity. States are prohibited from discriminating against citizens of other states with respect to their basic rights, under the Privileges and Immunities Clause. Under the Extradition Clause, a state must extradite people located there who have fled charges of "treason, felony, or other crimes" in another state if the other state so demands. The principle of hot pursuit of a presumed felon and arrest by the law officers of one state in another state are often permitted by a state.[18]

With the consent of Congress, states may enter into interstate compacts, agreements between two or more states. Compacts are frequently used to manage a shared resource, such as transportation infrastructure or water rights.[19]

With the federal government

Every state is guaranteed[20] a form of government that is grounded in republican principles, such as the consent of the governed.[21] This guarantee has long been at the fore-front of the debate about the rights of citizens vis-à-vis the government. States are also guaranteed protection from invasion, and, upon the application of the state legislature (or executive, if the legislature cannot be convened), from domestic violence. This provision was discussed during the 1967 Detroit riot, but was not invoked.

Since the early 20th century, the Supreme Court has interpreted the Commerce Clause of the Constitution of the United States to allow greatly expanded scope of federal power over time, at the expense of powers formerly considered purely states' matters. The Cambridge Economic History of the United States says, "On the whole, especially after the mid-1880s, the Court construed the Commerce Clause in favor of increased federal power."[22] In Wickard v. Filburn 317 U.S. 111 (1942), the court expanded federal power to regulate the economy by holding that federal authority under the commerce clause extends to activities which may appear to be local in nature but in reality effect the entire national economy and are therefore of national concern.[23]

For example, Congress can regulate railway traffic across state lines, but it may also regulate rail traffic solely within a state, based on the reality that intrastate traffic still affects interstate commerce. In recent years, the Court has tried to place limits on the Commerce Clause in such cases as United States v. Lopez and United States v. Morrison.[clarification needed]

Another example of congressional power is its spending power—the ability of Congress to impose taxes and distribute the resulting revenue back to the states (subject to conditions set by Congress).[24] An example of this is the system of federal aid for highways, which include the Interstate Highway System. The system is mandated and largely funded by the federal government, and also serves the interests of the states. By threatening to withhold federal highway funds, Congress has been able to pressure state legislatures to pass a variety of laws.[citation needed] An example is the nationwide legal drinking age of 21, enacted by each state, brought about by the National Minimum Drinking Age Act. Although some objected that this infringes on states' rights, the Supreme Court upheld the practice as a permissible use of the Constitution's Spending Clause in South Dakota v. Dole 483 U.S. 203 (1987).

Admission into the Union

Article IV, Section 3, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution grants to Congress the authority to admit new states into the Union. Since the establishment of the United States in 1776, the number of states has expanded from the original 13 to 50. Each new state has been admitted on an equal footing with the existing states.[16] It also forbids the creation of new states from parts of existing states without the consent of both the affected states and Congress. This caveat was designed to give Eastern states that still had Western land claims (there were 4 in 1787), to have a veto over whether their western counties could become states,[15] and has served this same function since, whenever a proposal to partition an existing state or states in order that a region within might either join another state or to create a new state has come before Congress.

Most of the states admitted to the Union after the original 13 have been created from organized territories established and governed by Congress in accord with its plenary power under Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2.[25] The outline for this process was established by the Northwest Ordinance (1787), which predates the ratification of the Constitution. In some cases, an entire territory has become a state; in others some part of a territory has.

When the people of a territory make their desire for statehood known to the federal government, Congress may pass an enabling act authorizing the people of that territory to organize a constitutional convention to write a state constitution as a step towards admission to the Union. Each act details the mechanism by which the territory will be admitted as a state following ratification of their constitution and election of state officers. Although the use of an enabling act is a traditional historic practice, a number of territories have drafted constitutions for submission to Congress absent an enabling act and were subsequently admitted. Upon acceptance of that constitution, and upon meeting any additional Congressional stipulations, Congress has always admitted that territory as a state.

In addition to the original 13, six subsequent states were never an organized territory of the federal government, or part of one, before being admitted to the Union. Three were set off from an already existing state, two entered the Union after having been sovereign states, and one was established from unorganized territory:

- California, 1850, from land ceded to the United States by Mexico in 1848 under the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.[26][27][28]

- Kentucky, 1792, from Virginia (District of Kentucky: Fayette, Jefferson, and Lincoln counties)[26][27][29]

- Maine, 1820, from Massachusetts (District of Maine)[26][27][29]

- Texas, 1845, previously the Republic of Texas[26][27][30]

- Vermont, 1791, previously the Vermont Republic (also known as the New Hampshire Grants and claimed by New York)[26][27][31]

- West Virginia, 1863, from Virginia (Trans-Allegheny region counties) during the Civil War[27][29][32]

Congress is under no obligation to admit states, even in those areas whose population expresses a desire for statehood. Such has been the case numerous times during the nation’s history. In one instance, Mormon pioneers in Salt Lake City sought to establish the state of Deseret in 1849. It existed for slightly over two years and was never approved by the United States Congress. In another, leaders of the Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole) in Indian Territory proposed to establish the state of Sequoyah in 1905, as a means to retain control of their lands.[33] The proposed constitution ultimately failed in the U.S. Congress. Instead, the Indian Territory, along with Oklahoma Territory were both incorporated into the new state of Oklahoma in 1907. The first instance occurred while the nation still operated under the Articles of Confederation. The State of Franklin existed for several years, not long after the end of the American Revolution, but was never recognized by the Confederation Congress, which ultimately recognized North Carolina's claim of sovereignty over the area. The territory comprising Franklin later became part of the Southwest Territory, and ultimately the state of Tennessee.

Additionally, the entry of several states into the Union was delayed due to distinctive complicating factors. Among them, Michigan Territory, which petitioned Congress for statehood in 1835, was not admitted to the Union until 1837, due to a boundary dispute the adjoining state of Ohio. The Republic of Texas requested annexation to the United States in 1837, but fears about potential conflict with Mexico delayed the admission of Texas for nine years.[34] Also, statehood for Kansas Territory was held up for several years (1854–61) due to a series of internal violent conflicts involving anti-slavery and pro-slavery factions.

Possible new states

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico referred to itself as the "Commonwealth of Puerto Rico" in the English version of its constitution, and as "Estado Libre Asociado" (literally, Associated Free State) in the Spanish version.

As with any non-state territory of the United States, its residents do not have voting representation in the federal government. Puerto Rico has limited representation in the U.S. Congress in the form of a Resident Commissioner, a delegate with limited voting rights in the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union, and no voting rights otherwise.[35]

A non-binding referendum on statehood, independence, or a new option for an associated territory (different from the current status) was held on November 6, 2012. Sixty one percent (61%) of voters chose the statehood option, while one third of the ballots were submitted blank.[36][37]

On December 11, 2012, the Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico enacted a concurrent resolution requesting the President and the Congress of the United States to respond to the referendum of the people of Puerto Rico, held on November 6, 2012, to end its current form of territorial status and to begin the process to admit Puerto Rico as a State.[38]

Washington, D.C.

The intention of the Founding Fathers was that the United States capital should be at a neutral site, not giving favor to any existing state; as a result, the District of Columbia was created in 1800 to serve as the seat of government. The inhabitants of the District do not have full representation in Congress or a sovereign elected government (they were allotted presidential electors by the 23rd amendment, and have a non-voting delegate in Congress).

Some residents of the District support statehood of some form for that jurisdiction—either statehood for the whole district or for the inhabited part, with the remainder remaining under federal jurisdiction.

Others

Various proposals to divide California, usually involving splitting the south half from the north or the urban coastline from the rest of the state, have been advanced since the 1850s.[39] Similarly, numerous proposals to divide New York, all of which involve to some degree the separation of New York City from the rest of the state, have been promoted over the past several decades.[40] The partitioning of either state is, at the present, highly unlikely.

Other even less likely possible new states are Guam and the Virgin Islands, both of which are unincorporated organized territories of the United States. Also, either the Northern Mariana Islands or American Samoa, an unorganized, unincorporated territory, could seek statehood.

Secession from the Union

The Constitution is silent on the issue of the secession of a state from the union. However, its predecessor document, the Articles of Confederation, stated that the United States "shall be perpetual." The question of whether or not individual states held the right to unilateral secession remained a difficult and divisive one until the American Civil War. In 1860 and 1861, eleven southern states seceded, but following their defeat in the American Civil War were brought back into the Union during the Reconstruction Era. The federal government never recognized the secession of any of the rebellious states.[8][41]

Following the Civil War, the United States Supreme Court, in Texas v. White, held that states did not have the right to secede and that any act of secession was legally void. Drawing on the Preamble to the Constitution, which states that the Constitution was intended to "form a more perfect union" and speaks of the people of the United States in effect as a single body politic, as well as the language of the Articles of Confederation, the Supreme Court maintained that states did not have a right to secede. However, the court's reference in the same decision to the possibility of such changes occurring "through revolution, or through consent of the States," essentially means that this decision holds that no state has a right to unilaterally decide to leave the Union.[8][41]

Commonwealths

Four states—Kentucky, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia —adopted Constitutions early in their post-colonial existence identifying themselves as commonwealths, rather than states. These commonwealths are states, but legally, each is a commonwealth because the term is contained in its constitution.[42] As a result, “commonwealth” is used in all public and other state writings, actions or activities within their bounds.

The term, which refers to a state in which the supreme power is vested in the people, was first used in Virginia during the Interregnum, the 1649–60 period between the reigns of Charles I and Charles II during which parliament's Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector established a republican government known as the Commonwealth of England. Virginia became a royal colony again in 1660, and the word was dropped from the full title. When Virginia adopted its first constitution on June 29, 1776, it was reintroduced.[43] Pennsylvania followed suit when it drew up a constitution later that year, as did Massachusetts, in 1780, and Kentucky, in 1792.[42]

The U.S. territories of the Northern Marianas and Puerto Rico are also referred to as commonwealths. This designation does have a legal status different from that of the 50 states. Both of these commonwealths are unincorporated territories of the United States.

Origins of states' names

The 50 states have taken their names from a wide variety of languages. Twenty-four state names originate from Native American languages. Of these, eight are from Algonquian languages, seven are from Siouan languages, three are from Iroquoian languages, one is from Uto-Aztecan languages and five others are from other indigenous languages. Hawaii's name is derived from the Polynesian Hawaiian language.

Of the remaining names, 22 are from European languages: Seven from Latin (mainly Latinized forms of English names), the rest are from English, Spanish and French. Eleven states are named after individual people, including seven named for royalty and one named after an American president. The origins of six state names are unknown or disputed. Several of the states that derive their names from (corrupted) names used for Native peoples, have retained the plural ending of "s".

Geography

Borders

The borders of the 13 original states were largely determined by colonial charters. Their western boundaries were subsequently modified as the states ceded their western land claims to the Federal government during the 1780s and 1790s. Many state borders beyond those of the original 13 were set by Congress as it created territories, divided them, and over time, created states within them. Territorial and new state lines often followed various geographic features (such as rivers or mountain range peaks), and were influenced by settlement or transportation patterns. At various times, national borders with territories formerly controlled by other countries (British North America]], New France, New Spain including Spanish Florida, and Russian America) became institutionalized as the borders of U.S. states. In the West, relatively arbitrary straight lines following latitude and longitude often prevail, due to the sparseness of settlement west of the Mississippi River.

Once established, most state borders have, with few exceptions, been generally stable. Only two states, Missouri (Platte Purchase) and Nevada, grew appreciably after statehood. Several of the original states ceded land, over a several year period, to the Federal government, which in turn became the Northwest Territory, Southwest Territory, and Mississippi Territory. In 1791 Maryland and Virginia ceded land to create the District of Columbia (Virginia's portion was returned in 1847). In 1850, Texas ceded a large swath of land to the federal government. Additionally, Massachusetts and Virginia (on two occasions), have lost land, in each instance to form a new state.

There have been numerous other minor adjustments to state boundaries over the years due to improved surveys, resolution of ambiguous or disputed boundary definitions, or minor mutually agreed boundary adjustments for administrative convenience or other purposes.[26] Occasionally the United States Congress or the United States Supreme Court have settled state border disputes. One notable example is the case New Jersey v. New York, in which New Jersey won roughly 90% of Ellis Island from New York in 1998.[44]

Regional grouping

States may be grouped in regions; there are endless variations and possible groupings. Many are defined in law or regulations by the federal government. For example, the United States Census Bureau defines four statistical regions, with nine divisions.[45] The Census Bureau region definition is "widely used … for data collection and analysis,"[46] and is the most commonly used classification system.[47][48][49] Other multi-state regions are un-official, and defined by geography or cultural affinity rather than by state lines.

See also

References

- ^ "Table 1: Annual Estimates for the Resident Populations of the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico". Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ^ "United States Summary: 2000" (PDF). U.S. Census 2000. U. S. Census Bureau. April 2004. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ Erler, Edward. "Essays on Amendment XIV: Citizenship". The Heritage Foundation.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions About the Minnesota Legislature". Minnesota State Legislature.

- ^ Kristin D. Burnett. "Congressional Apportionment (2010 Census Briefs C2010BR-08)" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration.

- ^ Elhauge, Einer R. "Essays on Article II: Presidential Electors". The Heritage Foundation.

- ^ Article IV, Section 3, Clause 1 of the Constitution

- ^ a b c Aleksandar Pavković, Peter Radan, Creating New States: Theory and Practice of Secession, p. 222, Ashgate Publishing, 2007.

- ^ "Texas v. White 74 U.S. 700 (1868)". Justia.com.

- ^ "State & Local Government". whitehouse.gov. The White House.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions About the Minnesota Legislature". Minnesota State Legislature.

- ^ "Gubernatorial Veto Authority with Respect to Major Budget Bill(s)". National Conference of State Legislatures.

- ^ http://www.reformcal.com/citleg_historical.pdf

- ^ Wilson, Reid (August 23, 2013). "GovBeat:For legislators, salaries start at zero". Washington Post. Washington, DC. pp. A2. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Forte, David F. "Essays on Article IV: New States Clause". The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. The Heritage Foundation.

- ^ a b "Doctrine of the Equality of States". Justia.com. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ Adam Liptak (March 17, 2004). "Bans on Interracial Unions Offer Perspective on Gay Ones". New York Times.

- ^ "Hot Pursuit Law & Legal Definition". USLegal, Inc. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ deGolian, Crady. "Interstate Compacts: Background and History". Council on State Governments. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- ^ Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution

- ^ Ernest B. Abbott; Otto J. Hetzel (2010). Homeland Security and Emergency Management: A Legal Guide for State and Local Governments. American Bar Association. p. 52.

- ^ Stanley Lewis Engerman (2000). The Cambridge economic history of the United States: the colonial era. Cambridge University Press. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-521-55307-0.

- ^ David Shultz (2005). Encyclopedia of the Supreme Court. Infobase Publishing. p. 522. ISBN 978-0-8160-5086-4.

- ^ "Constitution of the United States, Article I, Section 8". Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ "Property and Territory: Powers of Congress". Justia.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Stein, Mark (2008). How the States Got Their Shapes. New York: HarperCollins. pp. xvi, 334. ISBN 9780061431395.

- ^ a b c d e f "Official Name and Status History of the several States and U.S. Territories". TheGreenPapers.com.

- ^ "California Admission Day September 9, 1850". CA.gov. California Department of Parks and Recreation.

- ^ a b c Michael P. Riccards, "Lincoln and the Political Question: The Creation of the State of West Virginia" Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 27, 1997 online edition

- ^ Holt, Michael F. (200). The fate of their country: politicians, slavery extension, and the coming of the Civil War. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8090-4439-9.

- ^ "The 14th State". Vermont History Explorer. Vermont Historical Society.

- ^ "A State of Convenience: The Creation of West Virginia, Chapter Twelve, Reorganized Government of Virginia Approves Separation". Wvculture.org. West Virginia Division of Culture and History.

- ^ "Museum of the Red River - The Choctaw". Museum of the Red River. 2005. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- ^ Winders, Richard Bruce (2002). Crisis in the Southwest: the United States, Mexico, and the Struggle over Texas. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 82, 92. ISBN 978-0-8420-2801-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Rules of the House of Representatives" (PDF). Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ^ "Puerto Ricans favor statehood for first time". CNN. November 7, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ "Puerto Ricans opt for statehood". Fox News. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ The Senate and the House of Representative of Puerto Rico Concurrent Resolution

- ^ Pierce, Tony (July 11, 2011). "'South California' proposed as 51st state by Republican supervisor". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ "New York: Mailer for Mayor". Time. June 12, 1969. Retrieved June 3, 2010.

- ^ a b Texas v. White, 74 U.S. 700 (1868) at Cornell University Law School Supreme Court collection.

- ^ a b "Why is Massachusetts a Commonwealth?". Mass.Gov. Commonwealth of Massachusetts. 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ Salmon, Emily J.; Edward D. C. Campbell, Jr., eds. (1994). The Hornbook of Virginia History (4th ed.). Richmond, VA: Virginia Office of Graphic Communications. p. 88. ISBN 0-88490-177-7.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda (May 27, 1998). "The Ellis Island Verdict: The Ruling; High Court Gives New Jersey Most of Ellis Island". The New York Times. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ United States Census Bureau, Geography Division. "Census Regions and Divisions of the United States" (PDF). Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ^ "The National Energy Modeling System: An Overview 2003" (Report #:DOE/EIA-0581, October 2009). United States Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration.

- ^ "The most widely used regional definitions follow those of the U.S. Bureau of the Census." Seymour Sudman and Norman M. Bradburn, Asking Questions: A Practical Guide to Questionnaire Design (1982). Jossey-Bass: p. 205.

- ^ "Perhaps the most widely used regional classification system is one developed by the U.S. Census Bureau." Dale M. Lewison, Retailing, Prentice Hall (1997): p. 384. ISBN 978-0-13-461427-4

- ^ "(M)ost demographic and food consumption data are presented in this four-region format." Pamela Goyan Kittler, Kathryn P. Sucher, Food and Culture, Cengage Learning (2008): p.475. ISBN 9780495115410

Further reading

- Stein, Mark, How the States Got Their Shapes, New York : Smithsonian Books/Collins, 2008. ISBN 978-0-06-143138-8

External links

- Information about All States from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- State Resource Guides, from the Library of Congress

- Tables with areas, populations, densities and more (in order of population)

- Tables with areas, populations, densities and more (alphabetical)

- State and Territorial Governments on USA.gov

- StateMaster – statistical database for U.S. states

- U.S. States: Comparisons, rankings, demographics

Template:Articles on first-level administrative divisions of North American countries