Ayurveda: Difference between revisions

Itsmejudith (talk | contribs) rewrite in lede to remove the dubious bits |

Summarise safety section in lead |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Current practices derived (or reportedly derived) from Ayurvedic medicine are regarded as part of [[complementary and alternative medicine]].<ref name="nccam1">{{cite journal|url= http://nccam.nih.gov/news/newsletter/2006_winter/ayurveda.htm |title=A Closer Look at Ayurvedic Medicine|journal=Focus on Complementary and Alternative Medicine|volume=XII|issue=4|year=Fall 2005/Winter 2006|publisher=[[National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine]] (NCCAM), US [[National Institutes of Health]] (NIH)|location=[[Bethesda, MD]]|author1= <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.>}} {{dead link|date=July 2010}}</ref> |

Current practices derived (or reportedly derived) from Ayurvedic medicine are regarded as part of [[complementary and alternative medicine]].<ref name="nccam1">{{cite journal|url= http://nccam.nih.gov/news/newsletter/2006_winter/ayurveda.htm |title=A Closer Look at Ayurvedic Medicine|journal=Focus on Complementary and Alternative Medicine|volume=XII|issue=4|year=Fall 2005/Winter 2006|publisher=[[National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine]] (NCCAM), US [[National Institutes of Health]] (NIH)|location=[[Bethesda, MD]]|author1= <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.>}} {{dead link|date=July 2010}}</ref> |

||

Safety concerns have been raised about Ayurveda: [[Rasa shastra]], the practice of adding metals, minerals or gems to herbs, is a source of toxic heavy metals such as [[lead]], [[Mercury (element)|mercury]] and [[arsenic]], and studies have indicated that around 20% of ayurvedic products available for sale in America contain dangerous levels of these minerals.<ref name="Saper2008" /><ref name="pmid15598918" /><ref name="Saper2008" /><ref name="NewYorkTimes2008-09-17" /> Likewise, some of the herbs used have toxic components, which are not always detoxified by the methods intended to do so.<ref name="Urmila2008" /> |

|||

==Overview== |

==Overview== |

||

[[File:Ayurveda humors.png|thumb|right|The three doṣas and the 5 elements from which they are composed.]] |

[[File:Ayurveda humors.png|thumb|right|The three doṣas and the 5 elements from which they are composed.]] |

||

Revision as of 13:49, 12 September 2011

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

Ayurveda (Sanskrit: आयुर्वेद; Āyurveda, "the complete knowledge for long life"; /ˌaɪ.ərˈveɪdə/[1]) or ayurvedic medicine is a system of traditional medicine native to India[2] and a form of alternative medicine.[3] In Sanskrit, words āyus, meaning "longevity", and veda, meaning "related to knowledge" or "science".[2][4] The earliest literature on Indian medical practice appeared during the Vedic period in India,[3] i.e., in the mid-second millennium BCE. The Suśruta Saṃhitā and the Caraka Saṃhitā are great encyclopedias of medicine compiled from various sources from the mid-first millennium BCE to about 500 CE.[5] They are among the foundational works of Ayurveda. Over the following centuries, ayurvedic practitioners developed a number of medicinal preparations and surgical procedures for the treatment of various ailments .[6]

Current practices derived (or reportedly derived) from Ayurvedic medicine are regarded as part of complementary and alternative medicine.[7]

Safety concerns have been raised about Ayurveda: Rasa shastra, the practice of adding metals, minerals or gems to herbs, is a source of toxic heavy metals such as lead, mercury and arsenic, and studies have indicated that around 20% of ayurvedic products available for sale in America contain dangerous levels of these minerals.[8][9][8][10] Likewise, some of the herbs used have toxic components, which are not always detoxified by the methods intended to do so.[11]

Overview

At an early period, Ayurveda adopted the physics of the "five elements" (Devanāgarī: [महा] पञ्चभूत;Pṛthvī- (earth), Jala(water), Agni (fire), Vāyu (air) and Ākāśa (Sky)) — that compose the universe, including the human body.[2] Chyle or plasma (called rasa dhātu), blood (rakta dhātu), flesh (māṃsa dhātu), fat (medha dhātu), bone (asthi dhātu), marrow (majja dhātu), and semen or female reproductive tissue (śukra dhātu) are held to be the seven primary constituent elements – saptadhātu (Devanāgarī: सप्तधातु) of the body.[12] Ayurvedic literature deals elaborately with measures of healthful living during the entire span of life and its various phases. Ayurveda stresses a balance of three elemental energies or humors: vāta (air & space – "wind"), pitta (fire & water – "bile") and kapha (water & earth – "phlegm"). According to ayurvedic medical theory, these three substances — doṣas (literally that which deteriorates – Devanāgarī: दोष)—are important for health, because when they exist in equal quantities, the body will be healthy, and when they are not in equal amounts, the body will be unhealthy in various ways. One ayurvedic theory asserts that each human possesses a unique combination of doṣas that define that person's temperament and characteristics. Another view, also present in the ancient literature, asserts that humoral equality is identical to health, and that persons with preponderances of humours are proportionately unhealthy, and that this is not their natural temperament. In ayurveda, unlike the Sāṅkhya philosophical system, there are 20 fundamental qualities, guṇa (Devanāgarī: गुण, meaning qualities) inherent in all substances.[13] Surgery and surgical instruments were employed from a very early period,[13] Ayurvedic theory asserts that building a healthy metabolic system, attaining good digestion, and proper excretion leads to vitality.[13] Ayurveda also focuses on exercise, yoga, meditation, and massage.[14]

The practice of pañcakarma (Devanāgarī: पंचकर्म) is a therapeutic regime of purgation, sweating and massage that aims at eliminating toxic elements from the body.[15]

As early as the Mahābhārata, ayurveda was called "the science of eight components" (Skt. aṣṭāṅga, Devanāgarī: अष्टांग), a classification that became canonical for ayurveda. They are:[16]

- Internal medicine (Kāya-cikitsā)

- Paediatrics (Kaumārabhṛtyam)

- Surgery (Śalya-cikitsā)

- Eye and ENT (Śālākya tantra)

- Fear possession (Bhūta vidyā): Bhūta vidyā has been called psychiatry.[3]

- Toxicology (Agadatantram)

- Prevention diseases and improving immunity and rejuvenation (rasayana)

- Aphrodisiacs and improving health of progeny (Vajikaranam)

In Hindu mythology, the origin of ayurvedic medicine is attributed to the physician of the gods, Dhanvantari.[17]

Practices

Balance

Hinduism and Buddhism have been an influence on the development of many of ayurveda's central ideas — particularly its fascination with balance, known in Buddhism as Madhyamaka (Devanāgarī: माध्यात्मिक).[19] Balance is emphasized; suppressing natural urges is seen to be unhealthy, and doing so may almost certainly lead to illness.[19] However, people are cautioned to stay within the limits of reasonable balance and measure.[19] For example, emphasis is placed on moderation of food intake,[2] sleep, sexual intercourse, and the intake of medicine.[19]

Diagnosis

The Charaka Samhita recommends a tenfold examination of the patient.[20] The qualities to be judged are:[20]

- constitution

- abnormality

- essence

- stability

- body measurements

- diet suitability

- psychic strength

- digestive capacity

- physical fitness

- age

In addition, Chopra (2003) identifies five influential criteria for diagnosis:[20]

- origin of the disease

- prodrominal (precursory) symptoms

- typical symptoms of the fully developed disease

- observing the effect of therapeutic procedures

- the pathological process'

Ayurvedic practitioners approach diagnosis by using all five senses.[20] Hearing is used to observe the condition of breathing and speech.[12] The study of the lethal points or marma is of special importance.[13] Ayurvedic doctors regard physical and mental existence together with personality as a unit, each element having the capacity to influence the others. One of the fundamental aspects of ayurvedic medicine is to take this into account during diagnosis and therapy.

Hygiene

Hygiene is an Indian cultural value and a central practice of ayurvedic medicine. Hygienic living involves regular bathing, cleansing of teeth, skin care, and eye washing. Occasional anointing of the body with oil is also prescribed.[12]

Treatments

Ayurveda stresses the use of plant-based medicines and treatments. Hundreds of plant-based medicines are employed, including cardamom and cinnamon. Some animal products may also be used, for example milk, bones, and gallstones. In addition, fats are used both for consumption and for external use. Minerals, including sulfur, arsenic, lead, copper sulfate and gold are also consumed as prescribed.[12] This practice of adding minerals to herbal medicine is known as rasa shastra.

In some cases, alcohol is used as a narcotic for the patient undergoing an operation. The advent of Islam introduced opium as a narcotic.[16] Both oil and tar are used to stop bleeding.[12] Traumatic bleeding is said to be stopped by four different methods ligation of the blood vessel; cauterisation by heat; using different herbal or animal preparations locally which facilitate clotting; and different medical preparations which constrict the bleeding or oozing vessels. Different oils may be used in a number of ways including regular consumption as a part of food, anointing, smearing, head massage, and prescribed application to infected areas.[22]

-

Foot massage

-

Head massage

-

Facemask

-

Massage table

-

Steambox

Srotas

Ensuring the proper functions of channels (srotas) that transport fluids from one point to another is a vital goal of ayurvedic medicine, because the lack of healthy srotas is thought to cause rheumatism, epilepsy, autism, paralysis, convulsions, and insanity. Practitioners induce sweating and prescribe steam-based treatments as a means to open up the channels and dilute the doshas that cause the blockages and lead to disease.[23]

History

One view of the early history of ayurveda asserts that around 1500 BC, ayurveda's fundamental and applied principles got organised and enunciated. In this historical construction, Ayurveda traces its origins to the Vedas, Atharvaveda in particular, and is connected to Hindu religion. Atharvaveda (one of the four most ancient books of Indian knowledge, wisdom and culture) contains 114 hymns or formulations for the treatment of diseases. Ayurveda originated in and developed from these hymns. In this sense, ayurveda is considered by some to have divine origin. Indian medicine has a long history, and is one of the oldest organised systems of medicine. Its earliest concepts are set out in the sacred writings called the Vedas, especially in the metrical passages of the Atharvaveda, which may possibly date as far back as the 2nd millennium BC. According to a later writer, the system of medicine was received by Dhanvantari from Brahma, and Dhanvantari was deified as the god of medicine. In later times his status was gradually reduced, until he was credited with having been an earthly king[12] named Divodasa.[25]

A different historical narrative been developed by professional historians of medicine during the last twenty years. In this account, the medicine of the Atharvaveda and other Vedas is not directly connected to the origins of Ayurveda, although there are some continuities, especially in the area of pharmacology. The first traces of the ideas that become central to ayurvedic medical theory, such as the theories of doshas (humours) and the classification of disease causes, occur in the Pali Tripitaka, the Buddhist Canon. It has therefore been proposed that ayurvedic theory and practice owes a great deal to the practices and ideas of the ascetic milieu of the fifth to the third centuries BCE. This would include the early Buddhists, the Ajivikas, the Jains, and the ascetics mentioned in the Upanisads, as well as non-denominational renouncers.

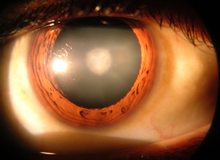

Underwood & Rhodes (2008) hold that this early phase of traditional Indian medicine identified 'fever (takman), cough, consumption, diarrhea, dropsy, abscesses, seizures, tumours, and skin diseases (including leprosy)'.[12] Treatment of complex ailments, including angina pectoris, diabetes, hypertension, and stones, also ensued during this period.[6][27] Plastic surgery, cataract surgery, puncturing to release fluids in the abdomen, extraction of foreign elements, treatment of anal fistulas, treating fractures, amputations, cesarean sections, and stitching of wounds were known.[12] The use of herbs and surgical instruments became widespread.[12] The Charaka Samhita text is arguably the principal classic reference. It gives emphasis to the triune nature of each person: body care, mental regulation, and spiritual/consciousness refinement.

Other early works of ayurveda include the Charaka Samhita, attributed to Charaka.[12] The earliest surviving excavated written material which contains references to the works of Sushruta is the Bower Manuscript, dated to the 6th century AD. The Bower manuscript is of special interest to historians due to the presence of Indian medicine and its concepts in Central Asia.[28] Vagbhata, the son of a senior doctor by the name of Simhagupta,[29] also compiled his works on traditional medicine.[12] Early ayurveda had a school of physicians and a school of surgeons.[3] Tradition holds that the text Agnivesh tantra, written by the sage Agnivesh, a student of the sage Bharadwaja, influenced the writings of ayurveda.[30]

The Chinese pilgrim Fa Hsien (ca. 337–422 AD) wrote about the health care system of the Gupta empire (320–550) and described the institutional approach of Indian medicine, also visible in the works of Charaka, who mentions a clinic and how it should be equipped.[31] Madhava (fl. 700), Sarngadhara (fl. 1300), and Bhavamisra (fl. 1500) compiled works on Indian medicine.[28] The medical works of both Sushruta and Charaka were translated into the Arabic language during the Abbasid Caliphate (ca. 750).[32] These Arabic works made their way into Europe via intermediaries.[32] In Italy, the Branca family of Sicily and Gaspare Tagliacozzi (Bologna) became familiar with the techniques of Sushruta.[32]

British physicians traveled to India to see rhinoplasty being performed by native methods.[33] Reports on Indian rhinoplasty were published in the Gentleman's Magazine in 1794.[33] Joseph Constantine Carpue spent 20 years in India studying local plastic surgery methods.[33] Carpue was able to perform the first major surgery in the western world in 1815.[34] Instruments described in the Sushruta Samhita were further modified in the Western World.[34]

Current status

Within India

In 1970, the Indian Medical Central Council Act which aims to standardize qualifications for ayurveda and provide accredited institutions for its study and research was passed by the Parliament of India.[35] In India, over 100 colleges offer degrees in traditional ayurvedic medicine.[14] The Indian government supports research and teaching in ayurveda through many channels at both the national and state levels, and helps institutionalize traditional medicine so that it can be studied in major towns and cities.[36] The state-sponsored Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha (CCRAS) is the premier institution for promotion of traditional medicine in India.[37] The studies conducted by this institution encompass clinical, drug, literary, and family welfare research.[37] To fight biopiracy and unethical patents, the Government of India, in 2001, set up the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library as repository of 1200 formulations of various systems of Indian medicine, such as ayurveda, unani and siddha.[38][39] The library also has 50 traditional ayurveda books digitized and available online.[40]

Central Council of Indian Medicine (CCIM) a statutory body established in 1971, under Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy (AYUSH), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, monitors higher education in ayurveda.[41] The Bachelor of Ayurveda, Medicine and Surgery (BAMS) degree is the basic five-and-a-half year course of graduation. It includes eighteen different subjects comprising courses on anatomy with cadaver dissections, physiology, pharmacology, pathology, modern clinical medicine & clinical surgery, pediatrics, along with subjects on ayurveda like Charaka Samhita, history and evolution of ayurveda, identification and usage of herbs (dravyaguna), and ayurvedic philosophy in diagnostics and treatment. post graduation programmes are also available in various specialities in ayurveda including surgery, paediatrics etc. The degree is awarded as m.d (ayurveda vachaspati) and m.s ayurveda (ayurveda dhanvantri). CCIM has also started the post graduation diplomas in various specialities of ayurveda.

Many clinics in urban and rural areas are run by professionals who qualify from these institutes.[35] Mukherjee & Wahile cite World Health Organization statistics to demonstrate the popularity of traditional medicine as the primary system of health care.[42]

Outside India

Several international and national initiatives have been formed to legitimize the education and practice of ayurvedic medicine as CAM in countries outside India:

- WHO policy of traditional medicine practice[43] and standardized benchmarks for training of Ayurvedic practitioners[44]

- The European Federation for Complementary and Alternative Medicine[45]

- The European Ayurveda Association[46]

In Sri Lanka

- Institute of Indigenous Medicine affiliated to University of Colombo[47]

- Gampaha Wickramarachchi Ayurveda Institute affiliated to University of Kelaniya[48]

- Seemasahitha Gampaha Siddhayrveda Rasayanoushadha Samagama[49]

- Ayurveda Lanka Hospital Pvt Ltd.

- Dr Eliyantha White – spiritual healer from Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Due to different laws and medical regulations in the rest of the world, the unregulated practice and commercialization of ayurvedic medicine has raised ethical and legal issues; in some cases, this damages the reputation of ayurvedic medicine outside India.[50][51][52]

In the United States

Early contributors to the promotion of Ayurveda in the United States include the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi's Transcendental Meditation group along with Dr. Deepak Chopra. Other important early promoters include Dr. David Frawley, Dr. Vasant Lad, Dr. Robert Svoboda Dr. John Douillard, Dr. Sarita Shrestha and Dr. Marc Halpern. In 1995, the California College of Ayurveda became the first State-Approved institution for training practitioners of Ayurveda in the United States marking the beginning of the formalization of Ayurvedic education in the United States. In 1997, Dr. Marc Halpern and several graduates of the California College of Ayurveda formed the California Association of Ayurvedic Medicine. This association was the first State association promoting the interests of Ayurveda in the United States. In 1998, four individuals founded the National Ayurvedic Medical Association. These four individuals were Dr. Marc Halpern, Wynn Werner, Dr. Kumar Batra and Cynthia Copple. In 2009, the United States of America National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) of the National Institutes of Health expended $1.2 million[53] of its $123 million annual budget on ayurvedic medicine-related research.

In the United Kingdom

Ayurveda was introduced to UK in early eighties. In 2001, the Thames Valley University started the first degree qualification in Ayurveda. It was followed by Manipal Ayurvedic University of Europe (BSc- Ayurveda) in 2006 and Middlesex University offering bachelors and masters degree programmes in Ayurveda.

The Secretary of State for Health has announced in a Ministerial Statement issued on 16 February 2011 by the UK Department of Health that the Health Professions Council (HPC) has been asked to establish a statutory register for practitioners supplying unlicensed herbal medicines including Ayurveda.A formal consultation exercise will take place on specific legislative proposals for establishing the register and proposed reforms of medicines legislation later in 2011. Subject to Parliamentary procedures, the Department of Health aims to have the legislation in place in 2012.

Journals

A variety of journals focus on the topic of ayurvedic medicine:

- Ancient Science of Life[54]

- Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine[55]

- Journal of Research & Education in Indian Medicine (JREIM),[56]

- AYU[57]

- The International Journal for Ayurveda Research (IJAR)[58]

None of the journals except IJAR [59] and JAIM [60] are PubMed indexed. The first subspeciality journal for the field of ayurvedic medicine was launched in July 2010. Its focus is rheumatology and it is titled the Journal of Clinical Rheumatology in Ayurveda.[61]

Patents

In December 1993, the University of Mississippi Medical Center had a patent issued to them by United States Patent and Trademark Office on the use of turmeric for healing.[62] The patent was contested by India's industrial research organization, Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), on the grounds that traditional ayurvedic practitioners were already aware of the healing properties of the substance for centuries, and that this prior art made the patent a case of bio-piracy.[63] The Government of India had become involved in promoting traditional medicine by 1997.[4] R A Mashelkar, director-general of the Indian Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, made the following observation:[64]

This is a significant development of far-reaching consequences for the protection of the traditional knowledge base in the public domain, which has been an emotional issue for not only the people of India but also for the other third world countries.

Scientific evidence

As a traditional medicine, many ayurveda products have not been tested in rigorous scientific studies and clinical trials. In India, research in ayurveda is largely undertaken by the statutory body of the Central Government, the Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha (CCRAS), through a national network of research institutes.[65] A systematic review of ayurveda treatments for rheumatoid arthritis concluded that there was insufficient evidence, as most of the trials were not done properly, and the one high-quality trial showed no benefits.[66] A review of ayurveda and cardiovascular disease concluded that while the herbal evidence is not yet convincing, the spices are appropriate, some herbs are promising, and yoga is also a promising complementary treatment.[67]

Some ayurvedic products, mainly herbs used for phytotherapy, have been tested with promising results. Studies suggest that Turmeric and its derivative curcumin are antioxidants.[68][69] Tinspora cordifolia has been tested.[70] Among the medhya rasayanas (intellect rejuvenation), two varieties of Salvia have been tested in small trials; one trial provided evidence that Salvia lavandulifolia (Spanish sage) may improve word recall in young adults,[71] and another provided evidence that Salvia officinalis (Common sage) may improve symptoms in Alzheimer's patients.[72] In some cases, ayurvedic medicine may provide clues to therapeutic compounds. For example, derivatives of snake venom have various therapeutic properties.[73] Many plants used as rasayana (rejuvenation) medications are potent antioxidants.[74] Neem appears to have beneficial pharmacological properties.[75]

Mitra & Rangesh (2003) hold that cardamom and cinnamon stimulate digestive enzymes that break down polymeric macromolecules in the human body.[21] Research suggests that T. arjuna is useful in alleviating the pain of angina pectoris and in treating heart failure and coronary artery disease.[76] T. arjuna may also be useful in treating hypercholesterolemia.[76]

Safety

Rasa shastra, the practice of adding metals, minerals or gems to herbs, is a source of toxic heavy metals such as lead, mercury and arsenic.[8] Adverse reactions to herbs due to their pharmacology are described in traditional ayurvedic texts, but ayurvedic practitioners are reluctant to admit that herbs could be toxic and the reliable information on herbal toxicity is not readily available.[11]

A 2004 study found such toxic metals in 20% of ayurvedic preparations that were made in South Asia for sale around Boston and extrapolated the data to the United States more broadly. It concluded that excess consumption of these products could cause health risks.[9] A 2008 study of more than 230 products found that approximately 20% of remedies (and 40% of rasa shastra medicines) purchased over the Internet from both US and Indian suppliers contained lead, mercury or arsenic.[8][10][79]

Traditionally, the toxicity of these materials are believed to be reduced through purification processes such as samskaras or shodhanas (for metals), which is similar to the Chinese pao zhi, although the ayurvedic technique is more complex and may involve prayers as well as physical pharmacy techniques. Following concerns about metal toxicity, the Government of India ruled that ayurvedic products must specify their metallic content directly on the labels of the product.[80]

Notes

- ^ Wells, John C. (2009). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. London: Pearson Longman.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d Chopra 2003, p. 75

- ^ a b c d "Ayurveda". New Delhi, India: Department of Ayurveda, Yoga & Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Sharma, H. M. (1997). "Alternative Medicine (medical system)". Encyclopædia Britannica (2008 ed.).

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wujastyk (2003)

- ^ a b Dwivedi & Dwivedi (2007)

- ^ <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.> (Fall 2005/Winter 2006). "A Closer Look at Ayurvedic Medicine". Focus on Complementary and Alternative Medicine. XII (4). Bethesda, MD: National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), US National Institutes of Health (NIH).

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) [dead link] - ^ a b c d Saper, R. B.; Phillips, R. S.; et al. (2008). "Lead, Mercury, and Arsenic in US- and Indian-manufactured ayurvedic Medicines Sold via the Internet". Journal of the American Medical Association. 300 (8): 915–923. doi:10.1001/jama.300.8.915. PMC 2755247. PMID 18728265.

- ^ a b Saper, R. B.; Kales, S. N.; Paquin, J.; et al. (2004). "Heavy Metal Content of Ayurveda Herbal Medicine Products". Journal of the American Medical Association. 292 (23): 2868–2673. doi:10.1001/jama.292.23.2868. PMID 15598918.

- ^ a b Ellin, Abby (September 17, 2008). "Skin Deep: Ancient, but How Safe?". The New York Times. New York, NY: NYTC. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

A report in the August 27 issue of The Journal of the American Medical Association found that nearly 21% of 193 ayurvedic herbal supplements bought online, produced in both India and the United States, contained lead, mercury or arsenic.

- ^ a b Urmila, T (2008). "Pharmacovigilance of Ayurvedic Medicines in India". Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 40 (S1): 10–12.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Underwood & Rhodes (2008)

- ^ a b c d Chopra 2003, p. 76

- ^ a b <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.> (2008). "Ayurveda". Encarta. Redmond, WA: Microsoft. Archived from the original on October 31, 2009.

- ^ Sharma, A. K. (2003). "Panchkarma Therapy in Ayurvedic Medicine". In Mishra, Lakshmi Chandra (ed.). Scientific Basis for Ayurvedic Therapies. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-8493-1366-X.

- ^ a b Chopra 2003, p. 80

- ^ Dhanvantari. (2010). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 04, 2010, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/160641/Dhanvantari

- ^ Clifford, Terry (2003). Tibetan Buddhist Medicine and Psychiatry. 42. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. ISBN 81-208-1784-2.

- ^ a b c d Wujastyk, p. XVIII

- ^ a b c d Chopra 2003, p. 79

- ^ a b Mitra & Rangesh, p. 363

- ^ Wujastyk, p. XX

- ^ Wujastyk, pp. XIX-XX

- ^ Kasulis, Thomas P. (1993). Self as Body in Asian Theory and Practice. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-7914-1079-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Singh, P.B. (2002). Banaras Region: A Spiritual and Cultural Guide. Varanasi: Indica Books. p. 31. ISBN 81-86569-24-3.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Finger, p. 66

- ^ Lock et al., p. 836

- ^ a b Wujastyk, p. XXVI

- ^ Wujastyk, p. 224

- ^ Ṭhākara, Vināyaka Jayānanda (1989). Methodology of Research in Ayurveda. Jamnagar, India: Gujarat Ayurved University Press. p. 7.

- ^ Wujastyk, pp. XV-XVI

- ^ a b c Lock et al., p. 607

- ^ a b c Lock "et al., p. 651

- ^ a b Lock et al., p. 652

- ^ a b Wujastyk, p. XXII

- ^ Wujastyk, p. XVI

- ^ a b Kurup, p. 7

- ^ Traditional Knowledge Digital Library website.

- ^ "Know Instances of Patenting on the UES of Medicinal Plants in India". PIB, Ministry of Environment and Forests. May 6, 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ 50 Ayurveda books online Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (Govt. of India)

- ^ CCIM. Ccimindia.org. Retrieved on 2011-08-29.

- ^ Mukherjee, P. K. (2006). "Integrated Approaches Towards Drug Development from Ayurveda and Other Indian System of Medicines". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 103 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.09.024. PMID 16271286.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ SEA/RC55/13. Searo.who.int. Retrieved on 2011-08-29.

- ^ Benchmarks for Training in Ayurveda. World Health Organization. Switzerland (2010) ISBN 978 9241599627

- ^ European Federation for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (EFCAM). Efcam.eu. Retrieved on 2011-08-29.

- ^ Ayurveda Start. P121583.mittwaldserver.info. Retrieved on 2011-02-15.

- ^ Institute of indigenous Medicine. Iim.cmb.ac.lk. Retrieved on 2011-08-29.

- ^ Gampaha Wickramarachchi Ayurveda Institute[dead link]

- ^ About: Gampaha Siddhayurveda Rasayanaushada Samagama. Siddhayurveda.lk. Retrieved on 2011-08-29.

- ^ Skolnick, Andrew A. (1991). "The Maharishi Caper: Or How to Hoodwink Top Medical Journals". ScienceWriters (New York, NY: National Association of Science Writers) Fall. Archived from the original on Jul 16, 2008. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ^ Skolnick, A. A. (1991). "Maharishi Ayur-Veda: Guru's marketing scheme promises the world eternal 'perfect health'". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 266 (13): 1741–2. doi:10.1001/jama.266.13.1741. PMID 1817475.

- ^ National Policy on Traditional Medicine and Regulation of Herbal Medicines – Report of a WHO Global Survey

- ^ NihReporter Query Form. Projectreporter.nih.gov. Retrieved on 2011-08-29.

- ^ Ancient Science of Life web site. Asl.ayurvedajournals.org. Retrieved on 2011-08-29.

- ^ "Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine". homepage. Retrieved Aug 23, 20011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Journal of Research & Education in Indian Medicine". homepage. Retrieved May 1, 2009.

- ^ "AYU: An International Quarterly Journal of Research in Ayurveda". homepage. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "International Journal for Ayurveda Research". homepage. Retrieved May 1, 2009.

- ^ International Journal of Ayurveda Research. Ijaronline.com (2009-03-05). Retrieved on 2011-08-29.

- ^ Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine. Jaim.in (2010-02-01). Retrieved on 2011-08-29.

- ^ "Journal of Clinical Rheumatology in Ayurveda". homepage. Retrieved Aug 23, 20011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ US Patent No. 5,401,504

- ^ Johnston, Barbara & Webb, Ginger (1997). "Turmeric Patent Overturned in Legal Victory". HerbalGram. Fall 1997 (41): 11.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kumar, Sanjay. India wins battle with USA over turmeric patent. The Lancet, Volume 350, Issue 9079, Page 724, 6 September 1997. The Lancet, Volume 350, Issue 9079, Page 724, 6 September 1997

- ^ "Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha (Government of India)".

- ^ Park, J. (2005). "Ayurvedic Medicine for Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 34 (5): 705–713. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.11.005. PMID 15846585.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mamtani, R. (2005). "Ayurveda and Yoga in Cardiovascular Diseases". Cardiology Review. 13 (3): 155–162. doi:10.1097/01.crd.0000128730.31658.36. PMID 15834238.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Tilak, JC, M Banerjee, H Mohan, TP Devasagayam (2004). "Antioxidant availability of turmeric in relation to its medicinal and culinary uses". Phytother Res. 18 (10): 798–804. doi:10.1002/ptr.1553. PMID 15551376.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aggarwal, B. B. (2007). "Curcumin: the Indian Solid Gold". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. ADVANCES IN EXPERIMENTAL MEDICINE AND BIOLOGY. 595: 1–75. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_1. ISBN 978-0-387-46400-8. PMID 17569205.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Panchabhai T.S., Kulkarni U.P., Rege N.N., TS; Kulkarni, UP; Rege, NN (2008). "Validation of therapeutic claims of Tinospora cordifolia: a review". Phytother Res. 22 (4): 425–41. doi:10.1002/ptr.2347. PMID 18167043.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tildesley, N. T.; Kennedy, D. O.; Perry, E. K.; et al. (2003). "Salvia lavandulaefolia (Spanish Sage) Enhances Memory in Healthy Young Volunteers". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 75 (3): 669–674. doi:10.1016/S0091-3057(03)00122-9. PMID 12895685.

- ^ Akhondzadeh, S. (2003). "Salvia officinalis Extract in the Treatment of Patients with Mild to Moderate Alzheimer's Disease: A Double Blind, Randomized and Placebo-controlled Trial". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 28 (1): 53–59. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2710.2003.00463.x. PMID 12605619.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Koh, D. C. (2006). "Snake Venom Components and Their Applications in Biomedicine". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 63 (24): 3030–3041. doi:10.1007/s00018-006-6315-0. PMID 17103111.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Govindarajan, R. (2005). "Antioxidant Approach to Disease Management and the Role of 'Rasayana' Herbs of Ayurveda". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 99 (2): 165–178. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.02.035. PMID 15894123.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Subapriya, R. (2005). "Medicinal Properties of Neem Leaves: A Review". Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 5 (2): 1496. doi:10.2174/1568011053174828. PMID 15777222.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Miller, A. L. (1998). "Botanical Influences on Cardiovascular Disease". Alternative Medicine Review. 3 (6): 422–431. PMID 9855567.

- ^ Mungantiwar, A. A. (2003). "Immunomodulation: Therapeutic Strategy through Ayurveda". Scientific Basis for Ayurvedic Therapies. op. cit. p. 72.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mitra & Rangesh, p. 319

- ^ Szabo, Liz (August 26, 2008). "Study Finds Toxins in Some Herbal Medicines". USA Today. McLean, VA: Gannett Co.

- ^ Valiathan, M. S. (2006). "Ayurveda: Putting the House in Order". Current Science. 90 (1). Indian Academy of Sciences: 5–6.

'What is Ayurvedic Medicine', http://www.dr-wakde.com/Ayurvedic_medicine1.html

References

- Chopra, Ananda S. (2003). "Āyurveda". In Selin, Helaine (ed.). Medicine Across Cultures: History and Practice of Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 75–83. ISBN 1-4020-1166-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dwivedi, Girish (2007). "History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence" (PDF). Indian Journal of Chest Diseases and Allied Sciences. 49. Delhi, India: Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute, U. of Delhi / National College of Chest Physicians: 243–244.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) (Republished by National Informatics Centre, Government of India.) - Finger, Stanley (2001). Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations into Brain Function. Oxford, England/New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514694-8.

- Kurup, P. N. V. (2003). "Ayurveda – A Potential Global Medical System". Scientific Basis for Ayurvedic Therapies. op. cit.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) in Lakshmi C. Mishra (2004). Scientific basis for Ayurvedic therapies. Boca Raton: CRC. ISBN 0-8493-1366-X. - Kutumbian, P. (1999). Ancient Indian Medicine. Andhra Pradesh, India: Orient Longman. ISBN 978-81-250-1521-5.

- Lock, Stephen (2001). The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine. Oxford U. Pr. ISBN 0-19-262950-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|display-authors=1(help) - Mitra, K. S. (2003). "Irritable Colon (Grahni)". Scientific Basis for Ayurvedic Therapies. op. cit.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Sharma, H. M. (1997). "Alternative Medicine (medical system)". Encyclopædia Britannica (2008 ed.).

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Underwood, E. Ashworth (2008). "Medicine, History of". Encyclopædia Britannica (2008 ed.).

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Wujastyk, D. (2003). The Roots of Ayurveda: Selections from Sanskrit Medical Writings. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044824-1.

Further reading

- Drury, Col. Heber (1873). The Useful plants of India. William H Allen & Co., London. ISBN 1446023729.

- Hoernle, Rudolf August Friedrich (1907). Studies in the Medicine of Ancient India: Part I: Osteology. The Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Kishor Patwardhan 2008. Concepts of Human Physiology in Ayurveda, in Sowarigpa and Ayurveda, Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies, Sarnath, Varanasi. Samyak Vak Series-14, Editor: Pabitra Kumar Roy, pp. 53–73. ISBN 978-81-87127-76-5 Kishor Patwardhan Concepts of Human Physiology in Ayurveda

External links

- Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes from August 2011

- Article Feedback Pilot

- Science and technology in India

- Ayurveda

- Vedic civilization

- Hindu philosophical concepts

- History of ancient medicine

- Sanskrit words and phrases

- Sakaldwipiya

- Traditional medicine

- Whole medical systems

- Pharmacy

- Alternative medical systems

- Massage therapy

- Healthcare in India