Jabir ibn Hayyan: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

Major rewrite of most things except lead, infobox, and biography |

|||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

==The Jabirian corpus== |

==The Jabirian corpus== |

||

[[File:Jabir ibn Hayyan Geber, Arabian alchemist Wellcome L0005558.jpg|thumb|European depiction of "Geber".]] |

|||

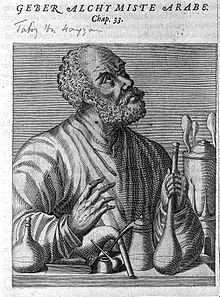

[[File:PSM V51 D390 Old stills from an early edition of geber.png|200px|thumb|An illustration of the various experiments and instruments used by Jabir Ibn Hayyan.]] |

|||

There are about 600 Arabic works attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan that are known by name,<ref>These are listed in Kraus 1942−1943: I: 203–210.</ref> approximately 215 of which are still extant today.<ref>Lory 1983: 51</ref> Though some of these are full-length works (e.g., ''The Great Book on Specific Properties''),<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 148–152, 205 (counted as one of the c. 600 works there).</ref> most of them are relatively short treatises and belong to larger collections (''The One Hundred and Twelve Books'', ''The Five Hundred Books'', etc.) in which they are rather more like chapters.<ref>Lory 1983: 51–52; Delva 2017: 37 n. 9.</ref> When the individual chapters of full-length works are counted as separate treatises too,<ref>See, e.g., ''The Great Book on Specific Properties'', whose 71 chapters are counted by Kraus 1942−1943: I: 148–152 as nos. 1900–1970. Note, however, that this procedure is not always followed: e.g., even though the ''The Book of the Rectifications of Plato'' consists of 90 chapters, it is still counted as only one treatise (Kr. no. 205, see Kraus 1942−1943: I: 64–67).</ref> the total length of the corpus may be estimated at about 3000 treatises/chapters.<ref>This is the number arrived at by Kraus 1942−1943: I. Kraus' method of counting has been criticized by [https://books.google.be/books?id=rydrCQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false Nomanul Haq 1994]: 11–12, who warns that "we should view with a great deal of suspicion any arguments for a plurality of authors which is based on Kraus' inflated estimate of the volume of the Jabirian corpus".</ref> |

|||

In total, nearly 3,000 treatises and articles are credited to Jabir ibn Hayyan.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Medieval Islamic Civilization|author1=[[Josef W. Meri]]|author2=[[Jere L. Bacharach]]|publisher=Taylor and Francis|year=2006|isbn=978-0-415-96691-7|page=25}}</ref> Following the pioneering work of [[Paul Kraus (Arabist)|Paul Kraus]], who demonstrated that a corpus of some several hundred works ascribed to Jābir were probably a medley from different hands,<ref name="Haq1994" /><ref>Jabir Ibn Hayyan. Vol. 1. Le corpus des ecrits jabiriens. George Olms Verlag, 1989</ref> mostly dating to the late 9th and early 10th centuries, many scholars believe that many of these works consist of commentaries and additions by his followers,{{Citation needed|date=May 2009}} particularly of an [[Ismaili]] persuasion.<ref>Paul Kraus, ''Jabir ibn Hayyan: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam'', cited Robert Irwin, 'The long siesta' in ''[[Times Literary Supplement]]'', 25 January 2008 p.8</ref> On the other hand, contemporary scholar [[Syed Nomanul Haq]] refuses the multiplicity of authors hypothesis, and says that Kraus has misrepresented the Jabirian corpus for three main reasons : a) he hasn't inspected the bibliographies correctly, considering that there have been many leaps (in one instance, we have no titles between 500 and 530), so, all in all, the numbers are more over 500 than close to 3000 ; b) in many cases, a part or chapter of a book has been counted as a book itself, like with the Kitab al-Jumal al-'Ishrin (book of twenty maxims), which has been counted for 20 books and c) finally, many of the supposed "books" are not so in the formal sense, the Kitab al-Sahl occupying a single paragraph and many others few folios. Syed Nomanul Haq concludes that "this rough investigation makes it abundantly clear that we should view with a great deal of suspicion any arguments for a plurality of authors which is based on Kraus' inflated estimate of the volume of the Jabirian corpus."<ref name="Haq1994" />{{rp|11–12}} |

|||

The overwhelming majority of Jabirian treatises that are still extant today deal with [[alchemy]] or [[chemistry]] (though these may also contain religious speculations, and discuss a wide range of other topics ranging from [[History of cosmology|cosmology]] to [[Arabic grammar|grammar]]).<ref>See the section 'Alchemical writings' below. Religious speculations occur throughout the corpus (see, e.g., [https://doi.org/10.3989/alqantara.2016.009 Lory 2016]), but are especially prominent in ''The Five Hundred Books'' (see below). ''The Books of the Balances'' deal with alchemy from a philosophical and theoretical point of view, and contain treatises devoted to a wide range of topics (see below).</ref> Nevertheless, there are also a few extant treatises which deal with [[Magic (supernatural)|magic]], or to be more precise, with "the science of [[Talisman|talismans]]" (''ʿilm al-ṭilasmāt'', a form of [[theurgy]]) and with the "science of specific properties" (''ʿilm al-khawāṣṣ'', i.e., the science dealing with the hidden powers of mineral, vegetable and animal substances, and with their practical applications in medical and various other pursuits).<ref>See the section 'Writings on magic (talismans, specific properties)' below. Kraus refers to ''ʿilm al-ṭilasmāt'' as "théurgie" ([[theurgy]]) throughout; see, e.g., Kraus 1942−1943: I: 75, 143, ''et pass.'' On the "science of specific properties" (''ʿilm al-khawāṣṣ''), see Kraus 1942−1943: II: 61–95.</ref> Other writings dealing with a great variety of subjects were also attributed to Jabir (this includes such subjects as [[History of engineering|engineering]], [[History of medicine|medicine]], [[History of pharmacy|pharmacology]], [[History of zoology through 1859|zoology]], [[History of botany|botany]], [[History of logic|logic]], [[History of metaphysics|metaphysics]], [[History of mathematics|mathematics]], [[History of astronomy|astronomy]] and [[History of astrology|astrology]]), but almost all of these are lost today.<ref>Only one full work (''The Book on Poisons and on the Repelling of their Harmful Effects'', ''Kitāb al-Sumūm wa-dafʿ maḍārrihā'', Kr. no. 2145, medical/pharmacological) and a long extract of another one (''The Book of Comprehensiveness'', ''Kitāb al-Ishtimāl'', Kr. no. 2715, philosophical) are still extant today; see the section 'Other writings' below, with Sezgin 1971: 264–265. Sezgin 1971: 268–269 also lists 30 extant works which were not known to Kraus, and whose subject matter and place in the corpus has not yet been determined.</ref> |

|||

The scope of the corpus is vast: [[cosmology]], [[music]], [[medicine]], [[Magic (supernatural)|magic]], [[biology]], [[chemical technology]], [[geometry]], [[grammar]], [[metaphysics]], [[logic]], artificial generation of living beings, along with astrological predictions, and symbolic Imâmî myths.<ref name="Haq1994" />{{rp|5}} |

|||

* '''The 112 Books''' dedicated to the [[Barmakids]], viziers of Caliph [[Harun al-Rashid]]. This group includes the Arabic version of the ''[[Emerald Tablet]]'', an ancient work that proved a recurring foundation of and source for alchemical operations. In the Middle Ages it was translated into Latin (''Tabula Smaragdina'') and widely diffused among European alchemists. |

|||

* '''The Seventy Books''', most of which were translated into Latin during the Middle Ages. This group includes the ''Kitab al-Zuhra'' ("Book of Venus") and the ''Kitab Al-Ahjar'' ("Book of Stones").<!--I'm guessing that they are in this group. Someone please check...--> |

|||

* '''The Ten Books on Rectification''', containing descriptions of alchemists such as [[Pythagoras]], [[Socrates]], [[Plato]] and [[Aristotle]]. |

|||

* '''The Books on Balance'''; this group includes his most famous 'Theory of the balance in Nature'. |

|||

Jabir states in his ''[[Book of Stones]]'' (4:12) that "The purpose is to baffle and lead into error everyone except those whom God loves and provides for". His works seem to have been deliberately written in highly esoteric code (see [[steganography]]), so that only those who had been initiated into his alchemical school could understand them. It is therefore difficult at best for the modern reader to discern which aspects of Jabir's work are to be read as ambiguous symbols, and what is to be taken literally. |

|||

=== |

===Alchemical writings=== |

||

Note that [[Paul Kraus (Arabist)|Paul Kraus]], who first [[Cataloging|catalogued]] the Jabirian writings and whose numbering will be followed here, conceived of his division of Jabir's alchemical writings (Kr. nos. 5–1149) as roughly chronological in order.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I. Kraus based this order on an extensive analysis of the many internal references to other treatises in the corpus. A slightly different chronological order is postulated by Sezgin 1971: 231–258 (who places ''The Books of the Balances'' after the ''The Five Hundred Books'', see pp. 252–253).</ref> |

|||

Jabir professed to have drawn his alchemical inspiration from earlier writers, both legendary and historic, on the subject.<ref>Julian, Franklyn, ''Dictionary of the Occult'', Kessinger Publishing, 2003, {{ISBN|0-7661-2816-4|978-0-7661-2816-3}}, p. 9.</ref> In his writings, Jabir pays tribute to Egyptian and Greek alchemists [[Zosimos of Panopolis|Zosimos]], [[Democritus]], [[Hermes Trismegistus]], [[Agathodaemon (alchemist)|Agathodaemon]], but also [[Plato]], [[Aristotle]], [[Galen]], [[Pythagoras]], and [[Socrates]], as well as the commentators [[Alexander of Aphrodisias]], [[Simplicius of Cilicia|Simplicius]], [[Porphyry (philosopher)|Porphyry]] and others.<ref name="Haq1994" />{{rp|5}} |

|||

* '''The Great Book of Mercy''' (''Kitāb al-Raḥma al-kabīr'', Kr. no. 5): This was considered by Kraus to be the oldest work in the corpus, from which it may have been relatively independent. Some early (10th century) sceptics considered it to be the only authentic work written by Jabir himself.<ref>All of the preceding in Kraus 1942−1943: I: 5–9.</ref> [[Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi|Abū Bakr al-Rāzī]] (c. 854–925) appears to have written a (lost) commentary on it.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: lx–lxi</ref> It was translated into Latin in the thirteenth century under the title ''Liber Misericordiae''.<ref>Edited by Darmstaedter 1925.</ref> |

|||

A huge pseudo-epigraphic literature of alchemical books was composed in Arabic, among which the names of [[Persian people|Persian]] authors also appear like [[Jāmāsb]], [[Ostanes]], [[Mani (prophet)|Mani]], testifying that alchemy-like operations on metals and other substances were also practiced in Persia. The great number of [[Persian language|Persian]] technical names (zaybaq = mercury, nošāder = sal-ammoniac) also corroborates the idea of an important Iranian root of medieval alchemy.<ref name="KIMIĀ Alchemy">[http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kimia KIMIĀ ("Alchemy")], [[Encyclopedia Iranica]], Retrieved on 19 November 2017.</ref> Ibn al-Nadim reports a dialogue between [[Aristotle]] and [[Ostanes]], the Persian alchemist of [[Achaemenid Empire|Achaemenid]] era, which is in Jabirian corpus under the title of Kitab Musahhaha Aristutalis.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/private/cmje/heritage/History_of_Islamic_Science.pdf |title=History of Islamic Science |publisher=University of Southern California |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131007200209/http://www.usc.edu/schools/college/crcc/private/cmje/heritage/History_of_Islamic_Science.pdf |archivedate= 7 October 2013 }}</ref> [[Julius Ruska|Ruska]] had suggested that the [[Sasanian]] medical schools played an important role in the spread of interest in alchemy.<ref name="KIMIĀ Alchemy"/> |

|||

He emphasizes the long history of alchemy, "whose origin is [[Arius]] ... the first man who applied the ''first'' experiment on the [philosopher's] stone... and he declares that man possesses the ability to imitate the workings of Nature" (Nasr, Seyyed Hussein, ''Science and Civilization of Islam''). |

|||

* '''The One Hundred and Twelve Books''' (''al-Kutub al-miʾa wa-l-ithnā ʿashar'', Kr. nos. 6–122): This collection consists of relatively independent treatises dealing with different practical aspects of alchemy, often framed as an explanation of the symbolic allusions of the 'ancients', and in which an important role is played by organic alchemy. Its theoretical foundations are similar to those of the ''Seventy Books'' (i.e., the reduction of bodies to the elements fire, air, water and earth, and of the elements to the 'natures' hot, cold, moist, and dry), though their exposition is less systematic than in the later ''Seventy Books''. Just like in the ''The Seventy Books'', the quantitative directions in ''The One Hundred and Twelve Books'' are of a practical and 'experimental' nature rather than of a theoretical and speculative nature, such as will be the case in the ''Books of Balances''.<ref>All of the preceding in Kraus 1942−1943: I: 11.</ref> The first four treatises in this collection, i.e., the three-part ''Book of the Element of the Foundation'' (''Kitāb Usṭuqus al-uss'', Kr. nos. 6–8, the second part of which contains an early version of the famous ''[[Emerald Tablet]]'' attributed to [[Hermes Trismegistus]])<ref>Zirnis 1979: 64–65, 90. Jabir explicitly notes that the version of the ''Emerald Tablet'' quoted by him is taken from "Balīnās the Sage" (i.e., [[Pseudepigrapha|pseudo]]-[[Apollonius of Tyana]]), although it differs slightly from the (probably even earlier) version preserved in pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana's ''Sirr al-khalīqa'' (''The Secret of Creation''): see Weisser 1980: 46.</ref> and a commentary on it (''Tafsīr kitāb al-usṭuqus'', Kr. no. 9), have been translated into English.<ref>Zirnis 1979. On some [[Shia Islam|Shi'ite]] aspects of the ''Book of the Element of the Foundation'', see [https://doi.org/10.3989/alqantara.2016.009 Lory 2016].</ref> |

|||

===Theories=== |

|||

Jabir's alchemical investigations ostensibly revolved around the ultimate goal of ''[[takwin]]'', the artificial creation of life. The ''Book of Assemblage'' "Kitāb Al-Tajmi' "<ref>{{cite book |last1=Jābir Ben Hayyān |last2=Al-Mizyadi |first2=Ahmad |title=Rasāil Jābir Ben Hayyān (Letters of Jābir Ben Hayyān) |date=2006 |publisher=Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah |location=Lebanon |page=229 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fJ9uDwAAQBAJ|isbn=978-2-7451-5398-2 }}</ref> includes several recipes for creating creatures such as [[scorpion]]s, [[snake]]s, and even humans in a laboratory environment, which are subject to the control of their creator. What Jabir meant by these recipes is unknown. |

|||

* '''The Seventy Books''' (''al-Kutub al-sabʿūn'', Kr. nos. 123–192) (also called ''The Book of Seventy'', ''Kitāb al-Sabʿīn''): This contains a systematic exposition of Jabirian alchemy, in which the several treatises form a much more unified whole as compared to ''The One Hundred and Twelve Books''.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 43–44.</ref> It is organized into seven parts, containing ten treatises each: three parts dealing with the preparation of the elixir from animal, vegetable, and mineral substances, respectively; two parts dealing with the four elements from a theoretical and practical point of view, respectively; one part focusing on the alchemical use of animal substances, and one part focusing on minerals and metals.<ref>Forster 2018.</ref> It was translated into Latin by a certain Magister Renaldus Cremonensis under the title ''Liber de Septuaginta''.<ref>Edited by Berthelot 1906.</ref> |

|||

Jabir's alchemical investigations were theoretically grounded in an elaborate [[numerology]] related to [[Pythagoras|Pythagorean]] and [[Neoplatonism|Neoplatonic]] systems.{{citation needed|date=July 2014}} The nature and properties of elements were defined through numeric values assigned to the [[Arabic language|Arabic]] consonants present in their name. |

|||

* '''Ten books added to the Seventy''' (''ʿasharat kutub muḍāfa ilā l-sabʿīn'', Kr. nos. 193–202): The sole surviving treatise from this small collection (''The Book of Clarification'', ''Kitāb al-Īḍāḥ'', Kr. no. 195) briefly discusses the different methods for preparing the elixir, criticizing the philosophers who have only expounded the method of preparing the elixir starting from mineral substances, to the exclusion of vegetable and animal substances.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 63.</ref> |

|||

By Jabir's time [[Aristotelian physics]] had become Neoplatonic. Each [[Classical element|Aristotelian element]] was composed of these qualities: [[fire (classical element)|fire]] was both hot and dry, [[earth (classical element)|earth]], cold and dry, [[water (classical element)|water]] cold and moist, and [[air (classical element)|air]], hot and moist. This came from the elementary qualities which are theoretical in nature plus substance. In metals two of these qualities were interior and two were exterior. For example, lead was cold and dry and gold was hot and moist. Thus, Jabir theorized, by rearranging the qualities of one metal, a different metal would result. Like [[Zosimos of Panopolis|Zosimos]], Jabir believed this would require a catalyst, an ''al-iksir'', the elusive elixir that would make this transformation possible – which in European alchemy became known as the [[philosopher's stone]].<ref name="Haq1994" /> |

|||

* '''The Ten Books of Rectifications''' (''al-Muṣaḥḥaḥāt al-ʿashara'', Kr. nos. 203–212): Relates the successive improvements ('rectifications', ''muṣaḥḥaḥāt'') brought to the art by such 'alchemists' as '[[Pythagoras]]' (Kr. no. 203), '[[Socrates]]' (Kr. no. 204), '[[Plato]]' (Kr. no. 205), '[[Aristotle]]' (Kr. no. 206), '[[Archigenes]]' (Kr. nos. 207–208), '[[Homer]]' (Kr. no. 209), '[[Democritus]]' (Kr. no. 210), Ḥarbī al-Ḥimyarī (Kr. no. 211),<ref>Ḥarbī al-Ḥimyarī occurs several times in the Jabirian writings as one of Jabir's teachers. He supposedly was 463 old when Jabir met him (see Kraus 1942−1943: I: xxxvii). According to Sezgin 1971: 127, the fact that Jabir dedicated a book to Ḥarbī's contributions to alchemy points to the existence in Jabir's time of a written work attributed to him.</ref> and Jabir himself (Kr. no. 212). The only surviving treatise from this small collection (''The Book of the Rectifications of Plato'', ''Kitāb Muṣaḥḥaḥāt Iflāṭūn'', Kr. no. 205) is divided into 90 chapters: 20 chapters on processes using only mercury, 10 chapters on processes using mercury and one additional 'medicine' (''dawāʾ''), 30 chapters on processes using mercury and two additional 'medicines', and 30 chapters on processes using mercury and three additional 'medicines'. All of these are preceded by an introduction describing the laboratory equipment mentioned in the treatise.<ref>All of the preceding in Kraus 1942−1943: I: 64–67. On the meaning here of ''muṣaḥḥaḥāt'', see esp. p. 64 n. 1 and the accompanying text. See also Sezgin 1971: 160–162, 167–168, 246–247.</ref> |

|||

According to Jabir's [[Classical element#Medieval alchemy|mercury-sulfur theory]], metals differ from each in so far as they contain different proportions of the sulfur and mercury. These are not the elements that we know by those names, but certain principles to which those elements are the closest approximation in nature.<ref>{{Cite book | publisher = Clarendon Press | last = Holmyard | first = E.J. | title = Makers of Chemistry | location = Oxford | year = 1931 |url=https://archive.org/details/makersofchemistr029725mbp | pages = 57–58}}</ref> Based on Aristotle's "exhalation" theory the dry and moist exhalations become ''sulfur'' and ''mercury'' (sometimes called "sophic" or "philosophic" mercury and sulfur). The sulfur-mercury theory is first recorded in a 7th-century work ''Secret of Creation'' credited (falsely) to [[Balinus]] ([[Apollonius of Tyana]]). This view becomes widespread.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Norris|first=John|date=March 2006|title=The Mineral Exhalation Theory of Metallogenesis in Pre-Modern Mineral Science|journal=Ambix|volume=53|pages=43–65|doi=10.1179/174582306X93183|s2cid=97109455}}</ref> In the ''Book of Explanation'' Jabir says<blockquote> |

|||

''the metals are all, in essence, composed of mercury combined and coagulated with sulphur [that has risen to it in earthy, smoke-like vapors]. They differ from one another only because of the difference of their accidental qualities, and this difference is due to the difference of their sulphur, which again is caused by a variation in the soils and in their positions with respect to the heat of the sun''</blockquote> |

|||

Holmyard says that Jabir proves by experiment that these are not ordinary sulfur and mercury.<ref name="Holmyard1931" /> |

|||

* '''The Twenty Books''' (''al-Kutub al-ʿishrūn'', Kr. nos. 213–232): Only one treatise (''The Book of the Crystal'', ''Kitāb al-Billawra'', Kr. no. 220) and a long extract from another one (''The Book of the Inner Consciousness'', ''Kitāb al-Ḍamīr'', Kr. no. 230) survive.<ref>Sezgin 1971: 248.</ref> ''The Book of the Inner Consciousness'' appears to deal with the subject of specific properties (''khawāṣṣ'') and with [[Talisman|talismans]] (''ṭilasmāt'').<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 69. On the "science of specific properties" (''ʿilm al-khawāṣṣ'', i.e., the science dealing with the hidden powers of mineral, vegetable and animal substances, and with their practical applications in medical and various other pursuits), see Kraus 1942−1943: II: 61–95.</ref> |

|||

The seeds of the modern classification of elements into [[metals]] and non-metals could be seen in his chemical nomenclature. He proposed three categories:<ref>Georges C. Anawati, "Arabic alchemy", in R. Rashed (1996), ''The Encyclopaedia of the History of Arabic Science'', Vol. 3, pp. 853–902 [866].</ref> |

|||

* "Spirits" which vaporise on heating, like [[arsenic]] ([[realgar]], [[orpiment]]), [[camphor]], [[mercury (element)|mercury]], [[sulfur]], [[sal ammoniac]], and [[ammonium chloride]]. |

|||

* "[[Classical metals|Metals]]", like [[gold]], [[silver]], [[lead]], [[tin]], [[copper]], [[iron]], and ''khar-sini'' (Chinese iron) |

|||

* Non-[[Malleability|malleable]] substances, that can be converted into [[Powder (substance)|powders]], such as [[Rock (geology)|stones]]. |

|||

* '''The Seventeen Books''' (Kr. nos. 233–249); '''three treatises added to the Seventeen Books''' (Kr. nos. 250–252); '''thirty unnamed books''' (Kr. nos. 253–282); '''The Four Treatises''' and some related treatises (Kr. nos. 283–286, 287–292); '''The Ten Books According to the Opinion of Balīnās, the Master of Talismans''' (Kr. nos. 293–302): Of these, only three treatises appear to be extant, i.e., the ''Kitāb al-Mawāzīn'' (Kr. no. 242), the ''Kitāb al-Istiqṣāʾ'' (Kr. no. 248), and the ''Kitāb al-Kāmil'' (Kr. no. 291).<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 70–74; Sezgin 1971: 248.</ref> |

|||

The origins of the idea of chemical [[Equivalent (chemistry)|equivalents]] might be traced back to Jabir, in whose time it was recognized that "a certain quantity of acid is necessary in order to neutralize a given amount of base."<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Equivalent Weights from Bergman's Data on Phlogiston Content of Metals|first1=J.A.|last1=Schufle|first2=George|last2=Thomas|journal=[[Isis (journal)|Isis]]|volume=62|issue=4|date=Winter 1971|page = 500 | doi=10.1086/350792|s2cid=145658080}}</ref>{{Verify source|date=June 2011}} |

|||

* '''The Books of the Balances''' (''Kutub al-Mawāzīn'', Kr. nos. 303–446): This collection appears to have consisted of 144 treatises of medium length, 79 of which are known by name and 44 of which are still extant. Though relatively independent from each other and devoted to a very wide range of topics ([[History of cosmology|cosmology]], [[Arabic grammar|grammar]], [[History of music theory|music theory]], [[History of medicine|medicine]], [[History of logic|logic]], [[History of metaphysics|metaphysics]], [[History of mathematics|mathematics]], [[History of astronomy|astronomy]], [[History of astrology|astrology]], etc.), they all approach their subject matter from the perspective of the "science of the balance" (''ʿilm al-mīzān'', a theory which aims at reducing all phenomena to a system of measures and quantitative proportions).<ref>All of the preceding in Kraus 1942−1943: I: 75–76. The theory of the balance is extensively discussed by Kraus 1942−1943: II: 187–303; see also Lory 1989: 130–150.</ref> ''The Books of the Balances'' are also an important source for Jabir's speculations regarding the apparition of the "two brothers" (''al-akhawān''),<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 76; Lory 1989: 103–105.</ref> a doctrine which was later to become of great significance to the Egyptian alchemist [[Muhammed ibn Umail al-Tamimi|Ibn Umayl]] (c. 900–960).<ref>[http://jas.cankaya.edu.tr/gecmisYayinlar/yayinlar/jas11/05%20Peter%20STARR.pdf Starr 2009]: 74–75.</ref> |

|||

===Laboratory equipment and material=== |

|||

[[File:Zosimosapparat.jpg|thumb|left|300px| Ambix, [[Alembic|cucurbit]] and [[retort]] of [[Zosimos of Panopolis|Zosimus]], from [[Marcelin Berthelot]], ''Collection of ancient Greek alchemists'' (3 vol., Paris, 1887–1888).]] |

|||

* '''The Five Hundred Books''' (''al-Kutub al-Khamsumiʾa'', Kr. nos. 447–946): Only 29 treatises in this collection are known by name, 15 of which are extant. Its contents appear to have been mainly religious in nature, with moral exhortations and alchemical allegories occupying an important place.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 100–101</ref> Among the extant treatises, ''The Book of the Glorious'' (''Kitāb al-Mājid'', Kr. no. 706) and ''The Book of Explication'' (''Kitāb al-Bayān'', Kr. no. 785) are notable for containing some of the earliest preserved [[Shia Islam|Shi'ite]] [[Eschatology|eschatological]] and [[Imamate in Shia doctrine|imamological]] doctrines.<ref>Corbin 1950; [https://doi.org/10.4000/remmm.249 Lory 2000].</ref> |

|||

The Jabirian corpus is renowned for its contributions to [[alchemy]]. It shows a clear recognition of the importance of experimentation, "The first essential in chemistry is that thou shouldest perform practical work and conduct experiments, for he who performs not practical work nor makes experiments will never attain to the least degree of mastery."<ref name="Holmyard 1931 60">{{Cite book | publisher = Clarendon Press | last = Holmyard | first = E.J. | title = Makers of Chemistry | location = Oxford | year = 1931 |url=https://archive.org/details/makersofchemistr029725mbp | page = 60 | authorlink = Eric John Holmyard}}</ref> He is credited with the use of over twenty types of now-basic chemical [[laboratory]] equipment,<ref name=Ansari/> such as the [[alembic]]<ref name=Durant>[[Will Durant]] (1980). ''The Age of Faith ([[The Story of Civilization]], Volume 4)'', pp. 162–186. Simon & Schuster. {{ISBN|0-671-01200-2}}.</ref> and [[retort]], and with the description of many now-commonplace chemical processes – such as [[crystallisation]], various forms of alchemical "distillation", and substances [[citric acid]] (the sour component of lemons and other unripe fruits), [[acetic acid]] (from vinegar) and [[tartaric acid]] (from wine-making residues), [[arsenic]], [[antimony]] and [[bismuth]], [[sulfur]], and [[Mercury (element)|mercury]]<ref name="Holmyard 1931 60"/><ref name=Ansari>{{Cite book|title=Electrocyclic reactions: from fundamentals to research|first1=Farzana Latif|last1=Ansari|first2=Rumana|last2=Qureshi|first3=Masood Latif|last3=Qureshi|year=1998|publisher=Wiley-VCH|isbn=978-3-527-29755-9|page=2}}</ref> that have become the foundation of today's [[chemistry]].<ref name="meyerhoff"/> |

|||

* '''The Books on the Seven Metals''' (Kr. nos. 947–956): Seven treatises which are closely related to ''The Books of the Balances'', each one dealing with one of Jabir's [[Metals of antiquity|seven metals]] (respectively gold, silver, copper, iron, tin, lead, and ''khārṣīnī'' or "chinese metal"). In one manuscript, these are followed by the related three-part ''Book of Concision'' (''Kitāb al-Ījāz'', Kr. nos. 954–956).<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 111–116. On ''khārṣīnī'', see Kraus 1942−1943: II: 22–23.</ref> |

|||

According to [[Ismail al-Faruqi]] and [[Lois Lamya al-Faruqi]], "In response to [[Ja'far al-Sadiq|Jafar al-Sadiq]]'s wishes, [Jabir ibn Hayyan] invented a kind of paper that [[Fireproofing|resisted fire]], and an ink that could be [[Chemiluminescence|read at night]]. He invented an additive which, when applied to an iron surface, inhibited [[rust]] and when applied to a textile, would make it [[Waterproofing|water repellent]]."<ref>[[Ismail al-Faruqi]] and [[Lois Lamya al-Faruqi]] (1986), ''The Cultural Atlas of Islam'', p. 328, New York</ref> |

|||

* '''Diverse alchemical treatises''' (Kr. nos. 957–1149): In this category, Kraus placed a large number of named treatises which he could not with any confidence attribute to one of the alchemical collections of the corpus. According to Kraus, some of them may actually have been part of the ''The Five Hundred Books''.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 117–140.</ref> |

|||

====Mineral acids and alcohol==== |

|||

Directions to make [[mineral acids]] such as [[sulfuric acid]], [[nitric acid]] and ''[[aqua regis]]'' appear in the Arabic Jabirian corpus,<ref name="hassan2005"/> and later in the [[pseudo-Geber]]ian works ''Liber Fornacum'', ''De inventione perfectionis'', and the ''Summa''.<ref name="Forbes1970" /> |

|||

===Writings on [[Magic (supernatural)|magic]] ([[Talisman|talismans]], specific properties)=== |

|||

According to Forbes, there is no proof that Jabir knew [[alcohol (drug)|alcohol]].<ref name="Forbes1970">{{cite book|last=Forbes|first=Robert James|title=A short history of the art of distillation: from the beginnings up to the death of Cellier Blumenthal|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XeqWOkKYn28C|accessdate=26 June 2010|year=1970|publisher=Brill|isbn=978-90-04-00617-1}}</ref> Later, [[Al-Kindi]] unambiguously described the [[Distilled beverage|distillation of wine]] in the 9th century.<ref>[[Ahmad Y. al-Hassan]] (2001), [https://books.google.com/books?id=h2g1qte4iegC&pg=PA65 ''Science and Technology in Islam: Technology and applied sciences'', pp. 65–69], [[UNESCO]]</ref><ref name=Hassan-Alcohol>{{cite web |url=http://www.history-science-technology.com/notes/notes7.html |title=Alcohol and the Distillation of Wine in Arabic Sources |accessdate=2014-04-19 |last=Hassan |first=Ahmad Y |authorlink=Ahmad Y Hassan |work=History of Science and Technology in Islam}}</ref><ref>[http://www.economist.com/node/2281757 The Economist: "Liquid fire – The Arabs discovered how to distill alcohol. They still do it best, say some"] 18 December 2003</ref> |

|||

Among the surviving Jabirian treatises, there are also a number of relatively independent treatises dealing with [[Talisman|talismans]] and/or specific properties.<ref>A number of non-extant treatises (Kr. nos. 1750, 1778, 1795, 1981, 1987, 1992, 1994) are also discussed by Kraus 1942−1943: I: 142–154.</ref> These are: |

|||

===Legacy=== |

|||

[[File:The Works of Geber book cover.jpg|thumb|300px|The book cover of The Works of Geber book by E J Holmyard and Richard Russell.]] |

|||

* '''The Book of the Search''' (''Kitāb al-Baḥth'', also known as ''The Book of Extracts'', ''Kitāb al-Nukhab'', Kr. no. 1800): This long work deals with the philosophical foundations of [[theurgy]] or "the science of talismans" (''ʿilm al-ṭilasmāt''). It is also notable for citing a significant number of Greek authors: there are references to (the works of) [[Plato]], [[Aristotle]], [[Archimedes]], [[Galen]], [[Alexander of Aphrodisias]], [[Porphyry (philosopher)|Porphyry]], [[Themistius]], ([[Pseudepigrapha|pseudo]]-)[[Apollonius of Tyana]], and others.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 142–143.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Jabir ibn Hayyan Geber, Arabian alchemist Wellcome L0005558.jpg|thumb|European depiction of "Geber".]] |

|||

* '''The Book of Fifty''' (''Kitāb al-Khamsīn'', perhaps identical to ''The Great Book on Talismans'', ''Kitāb al-Ṭilasmāt al-kabīr'', Kr. nos. 1825–1874): This work, only extracts of which are extant, deals with subjects such as the theoretical basis of [[theurgy]], specific properties, [[astrology]], and [[demonology]].<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 146–147.</ref> |

|||

* '''The Great Book on Specific Properties''' (''Kitāb al-Khawāṣṣ al-kabīr'', Kr. nos. 1900–1970): This is Jabir's main work on the "science of specific properties" (''ʿilm al-khawāṣṣ''), i.e., the science dealing with the hidden powers of mineral, vegetable and animal substances, and with their practical applications in medical and various other pursuits.<ref>On the "science of specific properties" (''ʿilm al-khawāṣṣ''), see Kraus 1942−1943: II: 61–95.</ref> However, it also contains a number of chapters on the "science of the balance" (''ʿilm al-mīzān'', a theory which aims at reducing all phenomena to a system of measures and quantitative proportions).<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 148–152. The theory of the balance, which is mainly expounded in ''The Books of the Balances'' (Kr. nos. 303–446, see above), is extensively discussed by Kraus 1942−1943: II: 187–303; see also Lory 1989: 130–150.</ref> |

|||

* '''The Book of the King''' (''Kitāb al-Malik'', kr. no. 1985): Short treatise on the effectiveness of [[Talisman|talismans]].<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 153.</ref> |

|||

* '''The Book of Black Magic''' (''Kitāb al-Jafr al-aswad'', Kr. no. 1996): This treatise is not mentioned in any other Jabirian work.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 154.</ref> |

|||

===Other writings=== |

|||

* '''Catalogues''' (Kr. nos. 1–4): There are three [[Cataloging|catalogues]] which Jabir is said to have written of his own works (Kr. nos. 1–3), and one ''Book on the Order of Reading our Books'' (''Kitāb Tartīb qirāʾat kutubinā'', Kr. no. 4). They are all lost.<ref>All of the preceding in Kraus 1942−1943: I: 3–4.</ref> |

|||

* '''The Books on Stratagems''' (''Kutub al-Ḥiyal'', Kr. nos. 1150–1449) and '''The Books on Military Stratagems and Tricks''' (''Kutub al-Ḥiyal al-ḥurūbiyya wa-l-makāyid'', Kr. nos. 1450–1749): Two large collections on 'mechanical tricks' (the Arabic word ''ḥiyal'' translates Greek μηχαναί, ''mēchanai'')<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 141 n. 1.</ref> and military [[History of engineering|engineering]], both lost.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: I: 141–142.</ref> |

|||

* '''[[History of medicine|Medical]] and [[History of pharmacy|pharmacological]] writings''' (Kr. nos. 2000–2499): Seven treatises are known by name, the only one extant being ''The Book on Poisons and on the Repelling of their Harmful Effects'' (''Kitāb al-Sumūm wa-dafʿ maḍārrihā'', Kr. no. 2145). Kraus also included into this category a lost treatise on [[History of zoology through 1859|zoology]] (''The Book of Animals'', ''Kitāb al-Ḥayawān'', Kr. no. 2458) and a lost treatise on [[History of botany|botany]] (''The Book of Plants'' or ''The Book of Herbs'', ''Kitāb al-Nabāt'' or ''Kitāb al-Ḥashāʾish'', Kr. no. 2459).<ref>All of the preceding in Kraus 1942−1943: I: 155–160.</ref> |

|||

* '''Philosophical writings''' (''Kutub al-falsafa'', Kr. nos. 2500–2799): Under this heading, Kraus mentioned 23 works, most of which appear to deal with [[Aristotelianism|Aristotelian philosophy]] (titles include, e.g., ''The Books of [[History of logic|Logic]] According to the Opinion of Aristotle'', Kr. no. 2580; ''The Book of [[Category of being|Categories]]'', Kr. no. 2582; ''The Book on [[History of hermeneutics|Interpretation]]'', Kr. no. 2583; ''The Book of [[History of metaphysics|Metaphysics]]'', Kr. no. 2681; ''The Book of the Refutation of Aristotle in his Book [[On the Soul]]'', Kr. no. 2734). Of one treatise (''The Book of Comprehensiveness'', ''Kitāb al-Ishtimāl'', Kr. no. 2715) a long extract is preserved by the poet and alchemist [[Al-Tughrai|al-Ṭughrāʾī]] (1061–c. 1121), but all other treatises in this group are lost.<ref>All of the preceding in Kraus 1942−1943: I: 161–166.</ref> |

|||

* '''[[History of mathematics|Mathematical]], [[History of astronomy|astronomical]] and [[History of astrology|astrological]] writings''' (Kr. nos. 2800–2899): Thirteen treatises in this category are known by name, all of which are lost. Notable titles include a ''Book of Commentary on [[Euclid]]'' (''Kitāb Sharḥ Uqlīdiyas'', Kr. no. 2813), a ''Commentary on the Book of the Weight of the Crown by [[Archimedes]]'' (''Sharḥ kitāb wazn al-tāj li-Arshamīdas'', Kr. no. 2821), a ''Book of Commentary on the [[Almagest]]'' (''Kitāb Sharḥ al-Majisṭī'', Kr. no. 2834), a ''Subtle Book on [[Ephemeris|Astronomical Tables]]'' (''Kitāb al-Zāj al-laṭīf'', Kr. no. 2839), a ''Compendium on the [[Astrolabe]] from a Theoretical and Practical Point of View'' (''Kitāb al-jāmiʿ fī l-asṭurlāb ʿilman wa-ʿamalan'', Kr. no. 2845), and a ''Book of the Explanation of the Figures of the [[Zodiac]] and Their Activities'' (''Kitāb Sharḥ ṣuwar al-burūj wa-afʿālihā'', Kr. no. 2856).<ref>All of the preceding in Kraus 1942−1943: I: 167–169.</ref> |

|||

* '''Religious writings''' (Kr. nos. 2900–3000): Apart from those known to belong to the ''The Five Hundred Books'' (see above), there are a number of religious treatises whose exact place in the corpus is uncertain, all of which are lost. Notable titles include ''Books on the [[Shia Islam|Shi'ite]] Schools of Thought'' (''Kutub fī [[madhhab|madhāhib]] al-shīʿa'', Kr. no. 2914), ''Our Books on the [[Metempsychosis|Transmigration of the Soul]]'' (''Kutubunā fī l-tanāsukh'', Kr. no. 2947), ''The Book of the [[Imamate]]'' (''Kitāb al-Imāma'', Kr. no. 2958), and ''The Book in Which I Explained the [[Torah]]'' (''Kitābī alladhī fassartu fīhi al-tawrāt'', Kr. no. 2982).<ref>All of the preceding in Kraus 1942−1943: I: 170–171.</ref> |

|||

==Historical Background== |

|||

===Greco-Egyptian, Byzantine and Persian alchemy=== |

|||

[[File:Liebig Company Trading Card Ad 01.12.002 front.tif|thumb|250px| Geber, Chimistes Celebres, [[Liebig's Extract of Meat Company]] Trading Card, 1929.]] |

[[File:Liebig Company Trading Card Ad 01.12.002 front.tif|thumb|250px| Geber, Chimistes Celebres, [[Liebig's Extract of Meat Company]] Trading Card, 1929.]] |

||

The Jabirian writings contain a number of references to Greco-Egyptian alchemists such as [[Pseudepigrapha|pseudo]]-[[Pseudo-Democritus|Democritus]] (fl. c. 60), [[Mary the Jewess]] (fl. c. 0–300), [[Agathodaemon (alchemist)|Agathodaemon]] (fl. c. 300), and [[Zosimos of Panopolis]] (fl. c. 300), as well as to legendary figures such as [[Hermes Trismegistus]] and [[Ostanes]], and to historical figures such as [[Moses]] and [[Jesus]] (to whom a number alchemical writings were also ascribed).<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: II: 42–45.</ref> However, these references may have been meant as an appeal to ancient authority rather than as an acknowledgement of any intellectual borrowing,<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: II: 35.</ref> and in any case Jabirian alchemy was very different from what is found in the extant Greek alchemical treatises: it was much more systematic and coherent,<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: II: 31–32.</ref> it made much less use of allegory and symbols,<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: II: 32–33.</ref> and a much more important place was occupied by philosophical speculations and their application to laboratory experiments.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: II: 40.</ref> Furthermore, whereas Greek alchemical texts had been almost exclusively focused on the use of mineral substances (i.e., on '[[inorganic chemistry]]'), Jabirian alchemy pioneered the use of vegetable and animal substances, and so represented an innovative shift towards '[[organic chemistry]]'.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: II: 41.</ref> |

|||

Whether Jabir lived in the 8th century or not, his name would become the most famous in alchemy.<ref name="Iranica jafar" /> |

|||

He paved the way for most of the later alchemists, including [[al-Kindi]], [[Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi|al-Razi]], [[al-Tughrai]] and [[Abu' l-Qasim al-Iraqi|al-Iraqi]], who lived in the 9th–13th centuries. His books strongly influenced the medieval European alchemists<ref name="meyerhoff"/> and justified their search for the [[philosopher's stone]].<ref name="Ragai 1992 58–77">{{Cite journal|title=The Philosopher's Stone: Alchemy and Chemistry|first=Jehane|last=Ragai|journal=Journal of Comparative Poetics|volume=12|issue=Metaphor and Allegory in the Middle Ages|year=1992|pages=58–77|doi=10.2307/521636|jstor=521636}}</ref><ref name="Holmyard 1924 293–305">{{Cite journal|title=Maslama al-Majriti and the Rutbatu'l-Hakim|first=E. J.|last=Holmyard|journal=[[Isis (journal)|Isis]]|volume=6|issue=3|year=1924|pages=293–305|doi=10.1086/358238|s2cid=144175388}}</ref> |

|||

In the [[Middle Ages]], Jabir's treatises on alchemy were [[Latin translations of the 12th century|translated into Latin]] and became standard texts for [[Europe]]an alchemists. These include the ''[[Kitab al-Kimya]]'' (titled ''Book of the Composition of Alchemy'' in Europe), translated by [[Robert of Chester]] (1144); and the ''[[Kitab al-Sab'een]]'' (''Book of Seventy'') by [[Gerard of Cremona]] (before 1187). [[Marcelin Berthelot]] translated some of his books under the fanciful titles ''Book of the Kingdom'', ''Book of the Balances'', and ''Book of Eastern Mercury''. Several technical [[Influence of Arabic on other languages|Arabic terms]] introduced by Jabir, such as ''[[alkali]]'', have found their way into various European languages and have become part of scientific vocabulary. |

|||

Nevertheless, there are some important similarities between Jabirian alchemy and contemporary [[Byzantine Empire|Byzantine]] alchemy,<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: II: 35–40.</ref> and even though the Jabirian authors do not seem to have known Byzantine works that are extant today such as the alchemical works attributed to the [[Neoplatonism|Neoplatonic]] philosophers [[Olympiodorus the Younger|Olympiodorus]] (c. 495–570) and [[Stephanus of Alexandria]] (fl. c. 580–640),<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: II: 40. Kraus also notes that this is rather remarkable given the existence of works attributed to Stephanus of Alexandria in the Arabic tradition.</ref> it seems that they were at least partly drawing on a parallel tradition of Neoplatonizing alchemy.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: II: 40–41.</ref> In any case, it appears that the Jabirian authors were mainly drawing upon alchemical works falsely attributed to [[Socrates]], [[Plato]], and [[Apollonius of Tyana]],<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: II: 41.</ref> only some of which are still extant today.<ref>Manuscripts of extant works are listed by Sezgin 1971 and Ullmann 1972.</ref> |

|||

Max Meyerhoff states of Jabir ibn Hayyan: {{quote|"His influence may be traced throughout the whole historic course of European alchemy and chemistry."<ref name="meyerhoff">Ḥusain, Muẓaffar. ''Islam's Contribution to Science.'' p. 94.</ref>}} |

|||

One of the innovations of Jabirian alchemy was the addition of [[sal ammoniac]] ([[ammonium chloride]]) to the category of chemical substances known as 'spirits' (i.e., strongly volatile substances). This included both naturally occurring sal ammoniac and synthetic ammonium chloride as produced from [[Organic compound|organic substances]], and so the addition of sal ammoniac to the list of 'spirits' is likely a product of the new focus on organic chemistry. Since the word for sal ammoniac used in the Jabirian corpus (''nūshādhir'') is Iranian in origin, it has been suggested that the direct precursors of Jabirian alchemy may have been active in the [[Hellenization|Hellenizing]] and [[Syriac language|Syriacizing]] schools of the [[Sasanian Empire|Sassanid Empire]].<ref>All of the preceding in Kraus 1942−1943: II: 41–42; cf. Lory 2008b.</ref> |

|||

The historian of chemistry [[Eric John Holmyard|Erick John Holmyard]] gives credit to Jabir for developing alchemy into an experimental science and he writes that Jabir's importance to the [[history of chemistry]] is equal to that of [[Robert Boyle]] and [[Antoine Lavoisier]]. |

|||

The historian Paul Kraus, who had studied most of Jabir's extant works in Arabic and Latin, summarized the importance of Jabir to the history of chemistry by comparing his experimental and systematic works in chemistry with that of the allegorical and unintelligible works of the [[ancient Greek]] alchemists.<ref name=Kraus>Kraus, Paul, Jâbir ibn Hayyân, ''Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque,''. Cairo (1942–1943). Repr. By Fuat Sezgin, (Natural Sciences in Islam. 67–68), Frankfurt. 2002</ref> |

|||

The word [[gibberish]] is theorized to be derived from the Latinised version of Jabir's name,<ref>[http://www.fromoldbooks.org/Grose-VulgarTongue/g/gibberish.html gibberish], ''Grose 1811 Dictionary''</ref> in reference to the incomprehensible technical [[jargon]] often used by alchemists, the most famous of whom was Jabir.<ref>{{Cite journal|first=Glenn T.|last=Seaborg|title=Our heritage of the elements|journal=[[Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B]]|volume=11|issue=1|date=March 1980|pages=5–19|doi=10.1007/bf02657166|bibcode=1980MTB....11....5S|s2cid=137614510}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Amr |first1=Samir S. |last2=Tbakhi |first2=Abdelghani |title=Jabir ibn Hayyan |journal=Annals of Saudi Medicine |pages=52–53 |doi=10.5144/0256-4947.2007.53 |date=2007|volume=27 |issue=1 |pmc=6077026 }}</ref> The [[Oxford English Dictionary]] suggests the term stems from [[gibber]]; however, the first known use of the term "[[gibberish]]" dates prior to the first known use of the word "gibber". |

|||

==Chemical philosophy== |

|||

==The Geber-Jabir problem== |

|||

The identity of the author of works attributed to Jabir has long been discussed.<ref name="Brabner2005" /> According to a famous controversy,<ref>Arthur John Hopkins, ''Alchemy Child of Greek Philosophy'', Published by Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007, {{ISBN|0-548-13547-9}}, p. 140</ref> [[pseudo-Geber]] has been considered as the unknown author of several books in [[Alchemy]].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online |title=Geber |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/227632/Geber |accessdate=9 December 2008}}</ref> This was first independently suggested, on textual and other grounds, by the 19th-century historians [[Hermann Franz Moritz Kopp|Hermann Kopp]] and [[Marcellin Berthelot]].<ref>Openness, Secrecy, Authorship: Technical Arts and the Culture of Knowledge from Antiquity to the Renaissance By Pamela O. Long Edition: illustrated Published by JHU Press, 2001 {{ISBN|0-8018-6606-5|978-0-8018-6606-7}}</ref> Jabir, by reputation the greatest [[chemist]] of Islam, has long been familiar to western readers under the name of Geber, which is the medieval rendering of the Arabic Jabir, the Geber of the [[Middle Ages]].<ref name="Ead">{{cite web |author=Hamed Abdel-reheem Ead |url=http://www.neurolinguistic.com/proxima/articoli/art-49.htm |title=Alchemy in Islamic Times |accessdate=23 May 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160529210124/http://www.neurolinguistic.com/proxima/articoli/art-49.htm |archive-date=29 May 2016 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

The works in Latin corpus were considered to be translations until the studies of Kopp, Hoefer, Berthelot, and Lippman. Although they reflect earlier Arabic alchemy they are not direct translations of "Jabir" but are the work of a 13th-century Latin alchemist.<ref name="Ihde1984">{{cite book|last=Ihde|first=Aaron John|title=The development of modern chemistry|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=34KwmkU4LG0C|accessdate=14 June 2010|date=1984|publisher=Courier Dover Publications|isbn=978-0-486-64235-2|page=16}}</ref> |

|||

Eric Holmyard says in his book Makers of Chemistry Clarendon press.(1931).<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hM5bQwAACAAJ |title=Makers of Chemistry, by Eric John Holmyard|via=Google Books|accessdate=15 October 2012|year=1962 }}</ref> |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

''There are, however, certain other Latin |

|||

works, entitled The Sum of Perfection, The Investigation of |

|||

Perfection, The Invention of Verity, The Book of Furnaces, and |

|||

The Testament, which pass under his name but of which no |

|||

Arabic original is known. A problem which historians of |

|||

chemistry have not yet succeeded in solving is whether these |

|||

works are genuine or not.'' |

|||

</blockquote> |

|||

However, by 1957 when he (Holmyard) wrote ''Alchemy''<ref>Courier Dover Publications. p. 134. {{ISBN|978-0-486-26298-7}}</ref> Holmyard had abandoned the idea of an Arabic original (although they are based on "Islamic" alchemical theories). |

|||

{{quote|The question at once arises whether the Latin works are genuine translations from the Arabic, or written by a Latin author and, according to common practice, ascribed to Jabir in order to heighten their authority. That they are based on Muslim alchemical theory and practice is not questioned, but the same may be said of most Latin treatises on alchemy of that period; and from various turns of phrase it seems likely that their author could read Arabic. But the general style of the works is too clear and systematic to find a close parallel in any of the known writings of the Jabirian corpus, and we look in vain in them for any references to the characteristically Jabirian ideas of "balance" and the alphabetic numerology. Indeed for their age they have a remarkably matter of fact air about them, theory being stated with a minimum of prolixity and much precise practical detail being given. The general impression they convey is that they are the product of an occidental rather than an oriental mind, and a likely guess would be that they were written by a European scholar, possibly in Moorish Spain. '''Whatever their origin, they became the principal authorities in early Western alchemy and held that position for two or three centuries'''.}} |

|||

===Elements and natures=== |

|||

The question of [[Pseudo-Geber]]s identity was still in dispute in 1962.<ref>P. Crosland, Maurice, ''Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry'', Courier Dover Publications, 2004 1962, {{ISBN|0-486-43802-3|978-0-486-43802-3}}, p. 15</ref> It is said that Geber, the Latinized form of "Jabir," was adopted presumably because of the great reputation of a supposed 8th-century alchemist by the name of Jabir ibn Hayyan.<ref name="Long2001">{{cite book|last=Long|first=Pamela O.|title=Openness, secrecy, authorship: technical arts and the culture of knowledge from antiquity to the Renaissance|year=2001|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|location=Baltimore|isbn=978-0-8018-6606-7}}</ref> About this historical figure, however, there was considerable uncertainty a century ago,<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |editor=Hugh Chisholm |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition |title=Geber |edition=11th |year=1910 |pages=545–546 }}</ref> and the uncertainty continues today.<ref>An authoritative summary and analysis of current scholarship on this question may be found in Lawrence M. Principe, ''The Secrets of Alchemy'', University of Chicago Press, 2013, pp. 33–45 and 54–58.</ref> This is sometimes called the "Geber-Jābir problem".<ref name="Brabner2005" /> It is possible that facts mentioned in the Latin works, ascribed to Geber and dating from the twelfth century and later, may be placed to Jabir's credit.<ref name="Ead" /> |

|||

By Jabir's time [[Aristotelian physics]] had become Neoplatonic. Each [[Classical element|Aristotelian element]] was composed of these qualities: [[fire (classical element)|fire]] was both hot and dry, [[earth (classical element)|earth]], cold and dry, [[water (classical element)|water]] cold and moist, and [[air (classical element)|air]], hot and moist. In the Jabirian corpus, these qualities came to be called "natures" (''ṭabāʾiʿ''), and elements are said to be composed of these 'natures', plus an underlying "substance" (''jawhar''). In metals two of these 'natures' were interior and two were exterior. For example, lead was cold and dry and gold was hot and moist. Thus, Jabir theorized, by rearranging the natures of one metal, a different metal would result. Like [[Zosimos of Panopolis|Zosimos]], Jabir believed this would require a catalyst, an ''al-iksir'', the elusive elixir that would make this transformation possible – which in European alchemy became known as the [[philosopher's stone]].<ref>[https://books.google.be/books?id=rydrCQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false Nomanul Haq 1994]</ref> |

|||

In 2005, the historian [[Ahmad Y. Al-Hassan]] pointed out that earlier Arabic texts prior to the 13th century, including the works of Jabir and [[Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi|Al-Razi]], already contained detailed descriptions of substances such as nitric acid, aqua regia, vitriol, and various nitrates.<ref name="hassan2005">Ahmad Y. Al-Hassan, ''Cultural contacts in building a universal civilisation: Islamic contributions'', published by [https://books.google.com/books?id=3iQXAQAAIAAJ O.I.C. Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture in 2005] and available [http://www.history-science-technology.com/articles/articles%2072.html online at History of Science and Technology in Islam]</ref> In 2009, Al-Hassan criticized Berthelot's original hypothesis and, on textual grounds, argued that the Pseudo-Geber Corpus was originally written in Arabic. Al-Hassan criticized Berthelot's lack of familiarity with the complete Arabic corpus and pointed to various Arabic Jabirian manuscripts which already contain much of the theories and practices that Berthelot previously attributed to the Latin corpus.<ref name=hassan>Ahmad Y. al-Hassan, ''Critical-Issues Studies in al-Kimya': Critical Issues in Latin and Arabic Alchemy and Chemistry'', published as book by [https://books.google.com/books?id=IMc8cgAACAAJ&dq=Critical-Issues+Studies+in+al-Kimya&hl=en&sa=X&ei=imODU4qpG4aS7Qa_x4GwCQ&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA Olms in 2009] and as article by [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1600-0498.2010.00206.x/abstract Centaurus journal in 2011]. Online versions are available at [http://www.history-science-technology.com/geber/geber.html ''Geber Problem'' at History of Science and Technology in Islam].</ref> Regardless of the identity of pseudo-Geber, the contents of the Pseudo-Geber Corpus are mostly derived from earlier Arabic alchemy, including the work of Jabir as well as other Arabic authors such as Al-Razi.<ref name=hassan/> |

|||

===The sulfur-mercury theory of metals=== |

|||

The sulfur-mercury theory of metals, though first attested in [[Pseudepigrapha|pseudo]]-[[Apollonius of Tyana]]'s ''Secret of Creation'' (''Sirr al-khalīqa'', early ninth century),<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: II: 1 n. 1; Weisser 1980: 199.</ref> was also adopted by the Jabirian authors. According to Jabirian version of this theory, metals form in the earth through the mixing of [[sulfur]] and [[Mercury (element)|mercury]]. Depending on the quality of the sulfur, different metals are formed, with gold being formed by the most subtle and well-balanced sulfur.<ref>Kraus 1942−1943: II: 1.</ref> This theory, which is ultimately based on ancient [[History of meteorology|meteorological]] theories such as found in [[Aristotle]]'s [[Meteorology (Aristotle)|''Meteorology'']], remained the standard theory of metallic composition until the eighteenth century.<ref>[https://doi.org/10.1179/174582306X93183 Norris 2006].</ref> |

|||

==In popular culture== |

==In popular culture== |

||

| Line 142: | Line 140: | ||

== Bibliography == |

== Bibliography == |

||

===English translations of Arabic |

===English translations of Arabic Jabirian texts=== |

||

[[Syed Nomanul Haq|Nomanul Haq, Syed]] 1994. ''Names, Natures and Things: The Alchemist Jābir ibn Ḥayyān and his Kitāb al-Aḥjār (Book of Stones)''. Dordrecht: Kluwer. ([https://books.google.be/books?id=rydrCQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false preview]) (contains a new edition of parts of the ''Kitāb al-Aḥjār'' with English translation) |

[[Syed Nomanul Haq|Nomanul Haq, Syed]] 1994. ''Names, Natures and Things: The Alchemist Jābir ibn Ḥayyān and his Kitāb al-Aḥjār (Book of Stones)''. Dordrecht: Kluwer. ([https://books.google.be/books?id=rydrCQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false preview]) (contains a new edition of parts of the ''Kitāb al-Aḥjār'' with English translation) |

||

| Line 149: | Line 147: | ||

Zirnis, Peter 1979. ''The Kitāb Usṭuqus al-uss of Jābir ibn Ḥayyān''. PhD diss., New York University. (contains an annotated copy of the ''Kitāb Usṭuqus al-uss'' with English translation) |

Zirnis, Peter 1979. ''The Kitāb Usṭuqus al-uss of Jābir ibn Ḥayyān''. PhD diss., New York University. (contains an annotated copy of the ''Kitāb Usṭuqus al-uss'' with English translation) |

||

===Latin translations of Arabic Jabirian texts=== |

|||

Berthelot, Marcellin 1906. "Archéologie et Histoire des sciences" in: ''Mémoires de l’Académie des sciences de l’Institut de France'', 49, pp. 308–363. |

|||

Darmstaedter, Ernst 1925. "Liber Misericordiae Geber: Eine lateinische Übersetzung des gröβeren Kitâb l-raḥma" in: ''Archiv für Geschichte der Medizin'', 17(4), pp. 181–197. |

|||

===Encyclopedic sources=== |

===Encyclopedic sources=== |

||

| Line 166: | Line 170: | ||

===[[Secondary source|Secondary sources]]=== |

===[[Secondary source|Secondary sources]]=== |

||

[[Ahmad Y. al-Hassan|al-Hassan, Ahmad Y.]] 2009. ''Studies in al-Kimya': Critical Issues in Latin and Arabic Alchemy and Chemistry. Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag''. (the same content and more is also available [http://www.history-science-technology.com online]) (argues against the great majority of scholars that the Latin Geber works were translated from the Arabic and that |

[[Ahmad Y. al-Hassan|al-Hassan, Ahmad Y.]] 2009. ''Studies in al-Kimya': Critical Issues in Latin and Arabic Alchemy and Chemistry. Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag''. (the same content and more is also available [http://www.history-science-technology.com online]) (argues against the great majority of scholars that all of the Latin Geber works were translated from the Arabic and that [[nitric acid]] was known in early Arabic alchemy) |

||

Capezzone, Leonardo 2020. [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0041977X20000014 “The Solitude of the Orphan: Ǧābir b. Ḥayyān and the Shiite Heterodox Milieu of the Third/Ninth–Fourth/Tenth Centuries”] in: ''Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies'', 83 (1), pp. 51–73. (recent study of Jābirian [[Shia Islam|Shi'ism]], arguing that it was not of a form of [[Isma'ilism]], but an independent sectarian current related to the late ninth-century Shi'ites known as [[ghulat|ghulāt]]) |

Capezzone, Leonardo 2020. [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0041977X20000014 “The Solitude of the Orphan: Ǧābir b. Ḥayyān and the Shiite Heterodox Milieu of the Third/Ninth–Fourth/Tenth Centuries”] in: ''Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies'', 83 (1), pp. 51–73. (recent study of Jābirian [[Shia Islam|Shi'ism]], arguing that it was not of a form of [[Isma'ilism]], but an independent sectarian current related to the late ninth-century Shi'ites known as [[ghulat|ghulāt]]) |

||

Corbin, Henry 1950. “Le livre du Glorieux de Jâbir ibn Hayyân” in: ''Eranos-Jahrbuch'', 18, pp. 48–114. |

|||

Delva, Thijs 2017. "The Abbasid Activist Ḥayyān al-ʿAṭṭār as the Father of Jābir b. Ḥayyān: An Influential Hypothesis Revisited" in: ''Journal of Abbasid Studies'', 4(1), pp. 35–61. [https://doi.org/10.1163/22142371-12340030 doi:10.1163/22142371-12340030] (rejects Holmyard 1927’s hypothesis that Jābir was the son of a proto-[[Shia Islam|Shi'ite]] pharmacist called Ḥayyān al-ʿAṭṭār on the basis of newly available evidence; contains the most recent [[status quaestionis]] on Jābir’s biography, listing a number of [[primary source|primary sources]] on this subject that were still unknown to Kraus 1942–1943) |

Delva, Thijs 2017. "The Abbasid Activist Ḥayyān al-ʿAṭṭār as the Father of Jābir b. Ḥayyān: An Influential Hypothesis Revisited" in: ''Journal of Abbasid Studies'', 4(1), pp. 35–61. [https://doi.org/10.1163/22142371-12340030 doi:10.1163/22142371-12340030] (rejects Holmyard 1927’s hypothesis that Jābir was the son of a proto-[[Shia Islam|Shi'ite]] pharmacist called Ḥayyān al-ʿAṭṭār on the basis of newly available evidence; contains the most recent [[status quaestionis]] on Jābir’s biography, listing a number of [[primary source|primary sources]] on this subject that were still unknown to Kraus 1942–1943) |

||

| Line 189: | Line 195: | ||

Lory, Pierre 1989. ''Alchimie et mystique en terre d’Islam''. Lagrasse: Verdier. (focuses upon Jābir's religious philosophy; contains an analysis of Jābirian [[Shia Islam|Shi'ism]], arguing that it is in some respects different from [[Isma'ilism]] and may have been relatively independent) |

Lory, Pierre 1989. ''Alchimie et mystique en terre d’Islam''. Lagrasse: Verdier. (focuses upon Jābir's religious philosophy; contains an analysis of Jābirian [[Shia Islam|Shi'ism]], arguing that it is in some respects different from [[Isma'ilism]] and may have been relatively independent) |

||

Lory, Pierre 2000. [https://doi.org/10.4000/remmm.249 “Eschatologie alchimique chez jâbir ibn Hayyân”] in: ''Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée'', 91-94, pp. 73–92. |

|||

Lory, Pierre 2016. [https://doi.org/10.3989/alqantara.2016.009 “Aspects de l’ésotérisme chiite dans le Corpus Ǧābirien: Les trois Livres de l’Elément de fondation”] in: ''Al-Qantara'', 37(2), pp. 279-298. |

|||

[[Syed Nomanul Haq|Nomanul Haq, Syed]] 1994. ''Names, Natures and Things: The Alchemist Jābir ibn Ḥayyān and his Kitāb al-Aḥjār (Book of Stones)''. Dordrecht: Kluwer. ([https://books.google.be/books?id=rydrCQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false preview]) (follows Sezgin 1971 in arguing for an early date of the Jābirian writings) |

[[Syed Nomanul Haq|Nomanul Haq, Syed]] 1994. ''Names, Natures and Things: The Alchemist Jābir ibn Ḥayyān and his Kitāb al-Aḥjār (Book of Stones)''. Dordrecht: Kluwer. ([https://books.google.be/books?id=rydrCQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false preview]) (follows Sezgin 1971 in arguing for an early date of the Jābirian writings) |

||

Norris, John 2006. [https://doi.org/10.1179/174582306X93183 “The Mineral Exhalation Theory of Metallogenesis in Pre-Modern Mineral Science”] in: ''Ambix'', 53, pp. 43–65. |

|||

[[Julius Ruska|Ruska, Julius]] and Garbers, Karl 1939. “Vorschriften zur Herstellung von scharfen Wässern bei Gabir und Razi” in: ''Der Islam'', 25, pp. 1–34. (contains a comparison of Jābir's and [[Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi|Abū Bakr al-Rāzī]]'s knowledge of chemical apparatus, processes and substances) |

[[Julius Ruska|Ruska, Julius]] and Garbers, Karl 1939. “Vorschriften zur Herstellung von scharfen Wässern bei Gabir und Razi” in: ''Der Islam'', 25, pp. 1–34. (contains a comparison of Jābir's and [[Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi|Abū Bakr al-Rāzī]]'s knowledge of chemical apparatus, processes and substances) |

||

[[Fuat Sezgin|Sezgin, Fuat]] 1971. ''Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums, Band IV: Alchimie, Chemie, Botanik, Agrikultur bis ca. 430 H.'' Leiden: Brill, pp. 132–269. (contains a penetrating critique of Kraus’ thesis on the late dating of the Jābirian works) |

[[Fuat Sezgin|Sezgin, Fuat]] 1971. ''Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums, Band IV: Alchimie, Chemie, Botanik, Agrikultur bis ca. 430 H.'' Leiden: Brill, pp. 132–269. (contains a penetrating critique of Kraus’ thesis on the late dating of the Jābirian works) |

||

Starr, Peter 2009. [http://jas.cankaya.edu.tr/gecmisYayinlar/yayinlar/jas11/05%20Peter%20STARR.pdf “Towards a Context for Ibn Umayl, Known to Chaucer as the Alchemist Senior”] in: ''Journal of Arts and Sciences'', 11, pp. 61–77. |

|||

Ullmann, Manfred 1972. ''Die Natur- und Geheimwissenschaften im Islam''. Leiden: Brill. |

|||

Weisser, Ursula 1980. ''Das Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana''. Berlin: De Gruyter. |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 00:09, 28 November 2020

Jabir ibn Hayyan | |

|---|---|

15th-century European portrait of "Geber", Codici Ashburnhamiani 1166, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence | |

| Title | Father of Chemistry |

| Personal | |

| Born | Abū Mūsā or Abū ‘Abd Allāh Jābir ibn Ḥayyān |

| Religion | Islam |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Region | Kufa, Tus |

| Denomination | Shia[1] |

| Main interest(s) | Alchemy and Chemistry, Astronomy, Astrology, Medicine and Pharmacy, Philosophy, Physics, philanthropist |

| Notable work(s) | Kitab al-Kimya, Kitab al-Sab'een, Book of the Kingdom, Book of the Balances, Book of Eastern Mercury, etc. |

| Muslim leader | |

Influenced by | |

Influenced | |

Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic/Persian جابر بن حيان, died c. early ninth century),[2] known by the kunyas Abū Mūsā or Abū ‘Abd Allāh[3]: 33 [2] and the nisbas al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, al-Ṭūsī or al-Ṣūfī, is the supposed[4] author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic often called the Jabirian corpus.[5] The scope of the corpus is vast and diverse covering a wide range of topics, including alchemy, cosmology, numerology, astrology, medicine, magic, mysticism and philosophy.[3]

Popularly known as the father of chemistry, Jabir's works contain the oldest known systematic classification of chemical substances, and the oldest known instructions for deriving an inorganic compound (sal ammoniac or ammonium chloride) from organic substances (such as plants, blood, and hair) by chemical means.[6]

As early as the 10th century, the identity and exact corpus of works of Jabir was in dispute in Islamic circles.[7] The authorship of all these works by a single figure, and even the existence of a historical Jabir, are also doubted by modern scholars.[4][8] Instead, Jabir ibn Hayyan is seen more like a pseudonym to whom "underground writings" by various authors became ascribed.[9]

Some Arabic Jabirian works (e.g., the "Book of Mercy", and the "Book of Seventy") were translated into Latin under the Latinized name "Geber",[10] and in 13th-century Europe an anonymous writer, usually referred to as pseudo-Geber, started to produce alchemical and metallurgical writings under this name.[11]

Biography

Early references

In 988 Ibn al-Nadim compiled the Kitab al-Fihrist which mentions Jabir as having a master named Ja'far, which Shia sources have linked with Jafar as-Sadiq, the sixth Shia Imam who had an interest in alchemy. Others argued that it was Ja'far ibn Yahya of the Barmaki family.[2] In another reference al-Nadim reports that a group of philosophers claimed Jabir was one of their own members. Another group, reported by al-Nadim, says only The Large Book of Mercy is genuine and that the rest are pseudographical. Their assertions are rejected by al-Nadim.[7] Joining al-Nadim in asserting a real Jabir; Ibn-Wahshiyya ("Jaber ibn Hayyn al-Sufi ...book on poison is a great work...") Rejecting a real Jabir; (the philosopher c. 970) Abu Sulayman al-Sijistani claims the real author is one al-Hasan ibn al-Nakad al-Mawili. The 14th century critic of Arabic literature, Jamal al-Din ibn Nubata al-Misri declares all the writings attributed to Jabir doubtful.[3]

Life and background

According to the philologist-historian Paul Kraus (1904–1944), Jabir cleverly mixed in his alchemical writings unambiguous references to the Ismaili or Qarmati movement. Kraus wrote: "Let us first notice that most of the names we find in this list have undeniable affinities with the doctrine of Shi'i Gnosis, especially with the Ismaili system."[12] Henry Corbin believes that Jabir ibn Hayyan was an Ismaili.[13] Jabir was a natural philosopher who lived mostly in the 8th century; he was born in Tus, Khorasan, in Persia,[14] then ruled by the Umayyad Caliphate. Jabir in the classical sources has been variously attributed as al-Azdi, al-Kufi, al-Tusi, al-Sufi, al-Tartusi or al-Tarsusi, and al-Harrani.[15][16] There is a difference of opinion as to whether he was an Arab[17] from Kufa who lived in Khurasan, or a Persian[18][19][20] from Khorasan who later went to Kufa[15] or whether he was, as some have suggested, of Syrian Sabian[21] origin and later lived in Persia and Iraq.[15] In some sources, he is reported to have been the son of Hayyan al-Azdi, a pharmacist of the Arabian Azd tribe who emigrated from Yemen to Kufa (in present-day Iraq).[22] while Henry Corbin believes Geber seems to have been a non-Arab client of the 'Azd tribe.[23] Hayyan had supported the Abbasid revolt against the Umayyads, and was sent by them to the province of Khorasan to gather support for their cause. He was eventually caught by the Umayyads and executed. His family fled to Yemen,[22][24] perhaps to some of their relatives in the Azd tribe,[25] where Jabir grew up and studied the Quran, mathematics and other subjects.[22] Jabir's father's profession may have contributed greatly to his interest in alchemy.

After the Abbasids took power, Jabir went back to Kufa. He began his career practicing medicine, under the patronage of a Vizir (from the noble Persian family Barmakids) of Caliph Harun al-Rashid. His connections to the Barmakid cost him dearly in the end. When that family fell from grace in 803, Jabir was placed under house arrest in Kufa, where he remained until his death.

It has been asserted that Jabir was a student of the sixth Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq and Harbi al-Himyari;[7][3] however, other scholars have questioned this theory.[26]

The Jabirian corpus

There are about 600 Arabic works attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan that are known by name,[27] approximately 215 of which are still extant today.[28] Though some of these are full-length works (e.g., The Great Book on Specific Properties),[29] most of them are relatively short treatises and belong to larger collections (The One Hundred and Twelve Books, The Five Hundred Books, etc.) in which they are rather more like chapters.[30] When the individual chapters of full-length works are counted as separate treatises too,[31] the total length of the corpus may be estimated at about 3000 treatises/chapters.[32]

The overwhelming majority of Jabirian treatises that are still extant today deal with alchemy or chemistry (though these may also contain religious speculations, and discuss a wide range of other topics ranging from cosmology to grammar).[33] Nevertheless, there are also a few extant treatises which deal with magic, or to be more precise, with "the science of talismans" (ʿilm al-ṭilasmāt, a form of theurgy) and with the "science of specific properties" (ʿilm al-khawāṣṣ, i.e., the science dealing with the hidden powers of mineral, vegetable and animal substances, and with their practical applications in medical and various other pursuits).[34] Other writings dealing with a great variety of subjects were also attributed to Jabir (this includes such subjects as engineering, medicine, pharmacology, zoology, botany, logic, metaphysics, mathematics, astronomy and astrology), but almost all of these are lost today.[35]

Alchemical writings

Note that Paul Kraus, who first catalogued the Jabirian writings and whose numbering will be followed here, conceived of his division of Jabir's alchemical writings (Kr. nos. 5–1149) as roughly chronological in order.[36]

- The Great Book of Mercy (Kitāb al-Raḥma al-kabīr, Kr. no. 5): This was considered by Kraus to be the oldest work in the corpus, from which it may have been relatively independent. Some early (10th century) sceptics considered it to be the only authentic work written by Jabir himself.[37] Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (c. 854–925) appears to have written a (lost) commentary on it.[38] It was translated into Latin in the thirteenth century under the title Liber Misericordiae.[39]

- The One Hundred and Twelve Books (al-Kutub al-miʾa wa-l-ithnā ʿashar, Kr. nos. 6–122): This collection consists of relatively independent treatises dealing with different practical aspects of alchemy, often framed as an explanation of the symbolic allusions of the 'ancients', and in which an important role is played by organic alchemy. Its theoretical foundations are similar to those of the Seventy Books (i.e., the reduction of bodies to the elements fire, air, water and earth, and of the elements to the 'natures' hot, cold, moist, and dry), though their exposition is less systematic than in the later Seventy Books. Just like in the The Seventy Books, the quantitative directions in The One Hundred and Twelve Books are of a practical and 'experimental' nature rather than of a theoretical and speculative nature, such as will be the case in the Books of Balances.[40] The first four treatises in this collection, i.e., the three-part Book of the Element of the Foundation (Kitāb Usṭuqus al-uss, Kr. nos. 6–8, the second part of which contains an early version of the famous Emerald Tablet attributed to Hermes Trismegistus)[41] and a commentary on it (Tafsīr kitāb al-usṭuqus, Kr. no. 9), have been translated into English.[42]

- The Seventy Books (al-Kutub al-sabʿūn, Kr. nos. 123–192) (also called The Book of Seventy, Kitāb al-Sabʿīn): This contains a systematic exposition of Jabirian alchemy, in which the several treatises form a much more unified whole as compared to The One Hundred and Twelve Books.[43] It is organized into seven parts, containing ten treatises each: three parts dealing with the preparation of the elixir from animal, vegetable, and mineral substances, respectively; two parts dealing with the four elements from a theoretical and practical point of view, respectively; one part focusing on the alchemical use of animal substances, and one part focusing on minerals and metals.[44] It was translated into Latin by a certain Magister Renaldus Cremonensis under the title Liber de Septuaginta.[45]

- Ten books added to the Seventy (ʿasharat kutub muḍāfa ilā l-sabʿīn, Kr. nos. 193–202): The sole surviving treatise from this small collection (The Book of Clarification, Kitāb al-Īḍāḥ, Kr. no. 195) briefly discusses the different methods for preparing the elixir, criticizing the philosophers who have only expounded the method of preparing the elixir starting from mineral substances, to the exclusion of vegetable and animal substances.[46]

- The Ten Books of Rectifications (al-Muṣaḥḥaḥāt al-ʿashara, Kr. nos. 203–212): Relates the successive improvements ('rectifications', muṣaḥḥaḥāt) brought to the art by such 'alchemists' as 'Pythagoras' (Kr. no. 203), 'Socrates' (Kr. no. 204), 'Plato' (Kr. no. 205), 'Aristotle' (Kr. no. 206), 'Archigenes' (Kr. nos. 207–208), 'Homer' (Kr. no. 209), 'Democritus' (Kr. no. 210), Ḥarbī al-Ḥimyarī (Kr. no. 211),[47] and Jabir himself (Kr. no. 212). The only surviving treatise from this small collection (The Book of the Rectifications of Plato, Kitāb Muṣaḥḥaḥāt Iflāṭūn, Kr. no. 205) is divided into 90 chapters: 20 chapters on processes using only mercury, 10 chapters on processes using mercury and one additional 'medicine' (dawāʾ), 30 chapters on processes using mercury and two additional 'medicines', and 30 chapters on processes using mercury and three additional 'medicines'. All of these are preceded by an introduction describing the laboratory equipment mentioned in the treatise.[48]

- The Twenty Books (al-Kutub al-ʿishrūn, Kr. nos. 213–232): Only one treatise (The Book of the Crystal, Kitāb al-Billawra, Kr. no. 220) and a long extract from another one (The Book of the Inner Consciousness, Kitāb al-Ḍamīr, Kr. no. 230) survive.[49] The Book of the Inner Consciousness appears to deal with the subject of specific properties (khawāṣṣ) and with talismans (ṭilasmāt).[50]

- The Seventeen Books (Kr. nos. 233–249); three treatises added to the Seventeen Books (Kr. nos. 250–252); thirty unnamed books (Kr. nos. 253–282); The Four Treatises and some related treatises (Kr. nos. 283–286, 287–292); The Ten Books According to the Opinion of Balīnās, the Master of Talismans (Kr. nos. 293–302): Of these, only three treatises appear to be extant, i.e., the Kitāb al-Mawāzīn (Kr. no. 242), the Kitāb al-Istiqṣāʾ (Kr. no. 248), and the Kitāb al-Kāmil (Kr. no. 291).[51]

- The Books of the Balances (Kutub al-Mawāzīn, Kr. nos. 303–446): This collection appears to have consisted of 144 treatises of medium length, 79 of which are known by name and 44 of which are still extant. Though relatively independent from each other and devoted to a very wide range of topics (cosmology, grammar, music theory, medicine, logic, metaphysics, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, etc.), they all approach their subject matter from the perspective of the "science of the balance" (ʿilm al-mīzān, a theory which aims at reducing all phenomena to a system of measures and quantitative proportions).[52] The Books of the Balances are also an important source for Jabir's speculations regarding the apparition of the "two brothers" (al-akhawān),[53] a doctrine which was later to become of great significance to the Egyptian alchemist Ibn Umayl (c. 900–960).[54]

- The Five Hundred Books (al-Kutub al-Khamsumiʾa, Kr. nos. 447–946): Only 29 treatises in this collection are known by name, 15 of which are extant. Its contents appear to have been mainly religious in nature, with moral exhortations and alchemical allegories occupying an important place.[55] Among the extant treatises, The Book of the Glorious (Kitāb al-Mājid, Kr. no. 706) and The Book of Explication (Kitāb al-Bayān, Kr. no. 785) are notable for containing some of the earliest preserved Shi'ite eschatological and imamological doctrines.[56]

- The Books on the Seven Metals (Kr. nos. 947–956): Seven treatises which are closely related to The Books of the Balances, each one dealing with one of Jabir's seven metals (respectively gold, silver, copper, iron, tin, lead, and khārṣīnī or "chinese metal"). In one manuscript, these are followed by the related three-part Book of Concision (Kitāb al-Ījāz, Kr. nos. 954–956).[57]