Constitutional patriotism

| Part of a series on |

| Nationalism |

|---|

Constitutional patriotism (Template:Lang-de) is the idea that people should form a political attachment to the norms and values of a pluralistic liberal democratic constitution rather than a national culture or cosmopolitan society.[1][2][3][4] It is associated with post-nationalist identity, because it is seen as a similar concept to nationalism, but as an attachment based on values of the constitution rather than a national culture. In essence, it is an attempt to re-conceptualise group identity with a focus on the interpretation of citizenship as a loyalty that goes beyond individuals' ethnocultural identification. Theorists believe this to be more defensible than other forms of shared commitment in a diverse modern state with multiple languages and group identities.[5] It is particularly relevant in post-national democratic states in which multiple cultural and ethnic groups coexist.[4] It was influential in the development of the European Union and a key to Europeanism as a basis for multiple countries belonging to a supranational union.[6]

Theoretical origins

Constitutional patriotism has been interpreted in a variety of ways, providing a range of positions.[7][2][8] On one end, there is the vision that the concept is a new means of identification to a supranational entity;[9] while on the other end, there is a focus on understanding the attachment in terms of freedom over ethnicity.[10] It is largely contested whether constitutional patriotism is supposed to be read as a replacement for nationality or traditional identity; or as a balance between the two, allowing for the "transient account of identity consistent with the diversity, hybridity, and pluralism of our modern world."[11] There are also multiple opinions as to whether a prior group identity is necessary before a moral, political one is achieved.

The concept of constitutional patriotism originates from Post-World War Two West Germany: "a 'half-nation' with a sense of deeply compromised nationality on account of their Nazi past."[12] In this context, constitutional patriotism was a protective and state-centered means of dealing with the memory of the Holocaust and militancy of the Third Reich.[12] The concept can be traced to the liberal philosopher Karl Jaspers, who advocated the idea of dealing with German political guilt after the war with 'collective responsibility'.[13] His student, Dolf Sternberger explicitly introduced the concept on the thirtieth birthday of the Federal Republic (1979). However, it is strongly associated with the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas.

Sternberger

Sternberger saw constitutional patriotism as a protective means to ensure political stability to maintain peace in Germany in the aftermath of the Second World War. He framed the concept as a way for citizens to identify with the democratic state in order that it could defend itself against internal and external threats.[12] Thus, with the emphasis on state defense and protection, Sternberger linked constitutional patriotism to the concept of militant democracy.[12] He drew on Aristotelianism, arguing that patriotism had traditionally not been linked to sentiments towards the nation.[12] Constitutional patriotism is a development of Sternberger's earlier notion of Staatsfreundschaft (friendship towards the state).

Habermas

Habermas played a key role in developing, contextualizing and spreading the idea of constitutional patriotism to English-speaking countries.[3] Like Sternberger, Habermas viewed constitutional patriotism as a conscious strengthening of political principles, however, "where Sternberger's patriotism had centred on democratic institutions worth defending, Habermas focused on the public sphere as providing a space for public reasoning among citizens."[12]

Post-war West Germany provided the context for Habermas's theories. During the historian's dispute of the late 1980s, Habermas fought against the normalization of "exceptional historical events" (the rise of Nazism and the events of the Holocaust).[14] Constitutional patriotism was Habermas's suggestion as a way to unify West Germans.[14] As he was concerned by the shaping of German identity through attempts to return to traditional national pride, he argued for Germans to "move away from the notion of ethnically homogeneous nation-states."[3][12][15] Thus it became an "inner counterpart to the bond of the Federal Republic to the West; it was not only an advance in respect to traditional German nationalism, but also a step toward overcoming it."[16] To Habermas, post-national German identity was dependent on understanding and overcoming its past, subjecting traditions to criticism.[14] This historical memory was essential to constitutional patriotism.[14]

Habermas believed a nationalistic collective identity was no longer feasible in a globalized modern world and scorned ethnic cohesion as a part of nineteenth century nationalism irrelevant in a new age of international migration.[17] His theory was therefore grounded in the idea that "the symbolic unity of the person that is produced and maintained through self-identification depends... on belonging to the symbolic reality of a group, on the possibility of localizing oneself in the world of this group. A group identity that transcends the life histories of individuals is thus a precondition of the identity of the individual."[18] In a disenchanted world, individual and collective identities were no longer formed by internalizing nationalist values but by becoming aware of "what they want and what others expect from them in the light of moral concerns" from an impartial position.[12]

He argued that the European nation-state was successful because "it made possible a new mode of legitimation based on a new, more abstract form of social integration."[18] Rather than a consensus on just values, Habermas believed the intricacies of modern societies must rely on "a consensus on the procedure for the legitimate enactment of laws and the legitimate exercise of power.”[19]

Current discussion

Constitutional patriotism is still a widely debated topic, which various theorists are expanding on and arguing about. Jan-Werner Müller follows in Habermas's footsteps, but works to broaden constitutional patriotism to be a framework which can be universally applied. Calhoun offers a competing framework to Müller, which emphasizes its connection to cosmopolitanism. Fossum discusses the differences in the two conceptions of constitutional patriotism which have emerged.

Müller

Jan-Werner Müller is one of the leading theorists of constitutional patriotism, having written more than 10 publications in two languages on the topic.[20] Building upon his predecessors, Müller advocates for constitutional patriotism as a unification option, especially in diverse, liberal democracies.[21] His ideas center on political attachment, democratic legitimacy and citizenship in a context that rejects nationalism, and addresses multicultural states, such as the European Union.[21] He provides some of the only extensive analysis on Sternberger and Habermas' original theories, and has developed and improved accessibility of the idea to the English-speaking world. He is known for "liberating it from Habermas's specific conception and opening up a more general discussion about constitutional patriotism," so it can be universally applied.[22] Müller offers some of the only modern and extensive responses to criticism of constitutional patriotism.[2][23] Müller's ideas place constitutional patriotism in a broader context, and have expanded its potential to be applied in places outside of Germany and the European Union.

Müller grounds his arguments for constitutional patriotism in the idea that political theory should supply citizens with the tools to rethink their commonalities, or unifying features. He argues that, while constitutional patriotism is distinct from liberal nationalism and cosmopolitanism, the best moral attributes of these theories can be combined to form a plausible and appealing style of political allegiance. However, where liberal nationalism and cosmopolitanism fall short, constitutional patriotism "theorizes the civic bond in a way that is more plausible sociologically and that leads to more liberal political outcomes." Similarly, it is a theory "oriented both toward stability and civic empowerment."

Calhoun

Craig Calhoun sees constitutional patriotism as the solidifying of a more general cosmopolitanism.[8] He notices that democracy is composed of more than political culture and suggests that a democracy has many more externalities. Habermas acknowledges this and questions whether or not "there exists a functional equivalent for the fusion of the nation of citizens with the ethnic nation."[24] However, Calhoun argues that Habermas falsely assumes that ethnic nationalism and nationalism are interchangeable.[8] Calhoun says constitutional patriotism is a common project shared amongst all citizens which is molded by a state's public discourse and culture.[8] Consequently, he proposes a revision to the constitutional patriotism theory and suggests that "the notion of constitution as legal framework needs to be complemented by the notion of constitution as the creation of concrete social relationships: of bonds of mutual commitment forged in shared action, of institutions, and of shared modalities of practical action."[8]

Fossum

John Erik Fossum, working off Habermas's definition and ideas, argues that two opposing ideas are inherent in constitutional patriotism- particularism and universalism- which affect allegiance.[25] The pull of these two ideas is referred to as thickness. Theorists such as Sternberger, Habermas, Müller, and Calhoun each have their own degree of thickness. In order to measure the thickness of allegiance in a type of constitutional patriotism, Fossum examines three factors: exit, voice and loyalty.[25] Exit is evaluated on how easy it is for a person to enter or exit the group and therefore has strong bearings on diversity.[25] Fossum believes it is crucial to pay attention to exit -and a nation's historical memory- in order to understand the thickness.[25] This is because historical memory helps unite communities and preserve their sense of identity.[25] In nationalism, exit is ignored because this shared history and/or ethnicity binds people together.[25] In constitutional patriotism, there is some room for exit; how much depends on the conception.[25] Voice is defined as each citizens relation and conceptualization of the theory.[25] Finally, loyalty is defined as the allegiance to the state's culture and constitution.[25]

| Constitutional Patriotism 1 | Constitutional Patriotism 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Exit | - Moderate 'cosmopolitan openness' for persons and arguments.

- Exit provisions only from communicative community, not available to territorial entities (3). |

- High 'cosmopolitan openness' for persons and arguments.

- Provisions for sub-unit exit from the polity, in compliance with democratic norms (2). |

| Voice | - Rights to ensure individual autonomy.

- Communication aimed at fostering agreement on common norms: pragmatic, ethical and moral. - Communication to foster solidarity and sense of community (2). |

- Rights to ensure individual autonomy.

- Communication aimed at reaching working agreements. - Communication to foster trust in procedures and rights: 'negative voice' (1). |

| Loyalty | - Positive endorsement of culturally embedded constitutional norms.

- Positive identification with the polity (1). |

- Ambivalence toward any form of positive allegiance.

- Systemic endorsement through critique (3). |

Examples

The following are commonly used as examples of applied constitutional patriotism.

Country examples

Spain

Constitutional Patriotism emerged in Spain following the creation of the 1978 constitution as a way to unify the country while overcoming ethnic and nationalist tendencies.[26] This identity would be based on "broadly inclusive concept[s] of citizenship" and "a sense of identification with a political system that delivered freedom and equality to every citizen" as established in the 1978 constitution.[27] Although the concept of constitutional patriotism has been used by both the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español [PSOE]) and the People's Party (Partido Popular [PP]), it is most predominant among the Socialist left.[14][28] During the last 2 decades of the 20th century, 'patriotism' replaced the term 'nationalism,' as the latter was used only among 'substate nationalists,' who meant the term in an ethnically, rather than civically, based sense.[29] José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero advocated for constitutional patriotism in his bid for Prime Minister in 2000 and in his election in 2004.[27] However, in the latter half of the 2000s, even the left has begun to abandon its defense of constitutional patriotism.[27]

One theoretical difference between Habermas's ideas of constitutional patriotism and the constitutional patriotism expressed in Spain, is a lack of memory.[14] While Habermas believed that facing the state's past and opening it to criticism was crucial, Spain has lacked this analysis of historical memory and still faces national questions regarding the Civil War and Francoism.[14]

Switzerland

Switzerland was among the countries originally cited by Sternberger as an example of constitutional patriotism.[30] The country has never been a nation-state, but rather has always been a confederacy, which is today populated by four main ethnic groups.[31][32] The heterogeny of Switzerland stems from its historical position in Europe and its need to defend against its neighbors. Its identity is "driven by a process of demarcation from others, triggered,among others, by the experience of defence against superior enemies."[33] This leads theorists such as Habermas, to put it forth as a "prototypical political nation."[34] The cornerstones of Swiss national identity are prescribed to the political values of direct democracy, neutrality and federalism.[34][35] These cornerstones show themselves in the country's policies and institutions which reinforce and are reinforced by the Swiss people, creating the common identity.[35] This has been critiqued by scholars who suggest that "nationally specific interpretations of constitutional principles do not predispose a common national culture."[34] Eugster writes about Swiss' multi-cultural identity and cultural diversity as an integral part of Swiss identity, not superseding the national political identity, but at least as a factor standing alongside it.[34] This argument counters the prevalent discussion of Switzerland as a fundamental example of constitutional patriotism.

United States

This section needs to be updated. (September 2017) |

In the United States of America, constitutional patriotism is primarily based on two documents: The Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Expectations of political behavior are outlined in the Constitution and the ideals embodied by them both have encouraged civic empowerment.[1] The United States demonstrates the ideas of constitutional patriotism in that Americans find a source of unity in their constitution which is able to supersede other cultural influences, forming a broader American identity.[4] The principles of the Declaration of Independence contribute to the basis of constitutional patriotism in America because, as William Kristol and Robert Kagan say, they are "not merely the choices of a particular culture but are universal, enduring, and self-evident truths."[36] These documents have both validated government action and citizen response.

Many of the values which contributed to the Founding Father's thinking come from ideas of the Enlightenment and over time have transformed into ideas of American exceptionalism and Manifest destiny.[37] Throughout the country's early history the Constitution was used as the basis for establishing foreign policy and determining the government's ability to acquire land from other nations. In the country's inception, government officials broadly interpreted the Constitution in order to establish an archetypical model for foreign policy.[38][39][40][41]

The battles, political and physical, over slavery are also demonstrations of constitutional patriotism in the United States, as they demonstrate the alteration of norms and values.[2] In the mid 1780s. hundreds of thousands of slaves served as the cornerstone of American production.[42] The constitution's defense of the rights of slave owners created a rift in the values of America:half of the country adhered to the Declaration of Independence's belief that 'all men are created equal' while the other half adhered to the constitution's ruling which allowed slavery. The rhetoric of many anti-slavery protesters appealed to the Constitution and Declaration of Independence in order to resolve this split in interpretation. Frederick Douglass stated that "the Constitution of the United States, standing alone, and construed only in the light of its letter, without reference to the opinions of the men who framed and adopted it, or to the uniform, universal and undeviating practice of the nation under it, from the time of its adoption until now, is not a pro-slavery instrument."[43] Similar rhetoric led to the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution and a universal anti-slavery constitutional patriotic view, changing the norms and values of society, which were then reified in the Constitution.

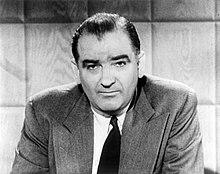

McCarthyism brings to light one critique of constitutional patriotism, which is that it, in the critics eyes, can lead to political witch-hunts of those traitorous to the political system[44] In the 1950s, thousands of Americans including government officials, members of the armed forces, cultural stars, and ordinary citizens had to stand before a congressional board to prove they had no communist relations.[45] This strict adherence to the constitution's declarations and fear of communism led to the removal of civil liberties of many citizens and the suspension or inversion of the law.[46] However, after numerous televised hearings and irrational accusations, Senator Joseph McCarthy was deemed no longer legitimate by the American people, and the communist concern regarding constitutional patriotism was relatively abandoned.[47] This confirms Müller's argument that, while instances like McCarthyism are possible in countries which adhere to constitutional patriotism, these societies often have values which eventually contest intolerance.[2]

The civil rights movement in the 20th century often referred to the constitution in order to gain popularity and legitimacy with the American people. In W. E. B. Du Bois's 1905 Niagara Movement Speech, he pleaded for equal voting rights and said, "We want the Constitution enforced."[48] This style was repeated throughout the movement by leaders such as Malcolm X, Ralph Abernathy, and Martin Luther King Jr. Using the Constitution, King justified the movement's message in his December 1955 address to the first full Montgomery Improvement Association meeting, stating: "If we are wrong, then the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong then the Constitution of the United States is wrong."[49] In 1968, King employed the Constitution once again to challenge the US government's civil rights legislation and stated "Be true to what you say on paper."[50]

Recent US administrations have handled the idea of constitutional patriotism differently. The Clinton administration instituted a policy which allowed the US government to determine what the Constitution needed. Ultimately foreign policy required that sovereignty be safeguarded so that the Constitution itself can be secure.[51] This resulted in rejections of the Land Mines Convention, the Rome Treaty, and the Kyoto Protocol.[51] Constitutional patriotism's effects shifted during the Bush Administration. After the attacks on September 11th, the Bush Administration released the National Strategy for Homeland Security (NSHS) and the National Security Strategy of the United States of America (NSSUSA) which defined the American people as a culture with shared liberal and democratic principles.[52] The NSHS specifically defined the American way of life as a "democratic political system... anchored by the Constitution."[52] This version of constitutional patriotism continues to be prevalent in US government and citizen action.

Supranational examples

The European Union

Constitutional patriotism in the European Union is extremely important because it is one of the only supranational case studies. While the theory can be observed in various instances throughout the world, most are observed in cases specific to the constitution of a single country.

Constitutional patriotism is especially applicable in the European Union because there is no single shared history or culture.[53] It is not rooted in pride in a culture, race or ethnicity, but rather, in a political order.[54] The European Union makes multinational claims in its constitution, and this makes political allegiance a complicated question to address.[25] Creating a unified European identity is a difficult task, but constitutional patriotism has offered a liberal alternative to other forms of nationalism.[54] It allows people to remain attached to a unique culture, potentially to their individual countries, but still share a common patriotic identity with other Europeans.[55] It also encourages Europeans to distance themselves from "ethnic public self-definitions, ethnic definitions of citizenship and ethnic-priority immigration."[56]

Constitutional patriotism holds a political order accountable because people have the choice to be constitutionally patriotic. People will only feel pride in a political order they feel warrants the emotion.[54] The diversity of states in the European Union also makes a constitutional bond an appealing style of unity.[25][57][58] Similarly, in the context of a history of wars, persecutions, genocide, and ethnic cleansing, states may choose to gather behind a constitution at the supranational level.[59]

Today, constitutional patriotism plays a role in distancing the current European Union from its past totalitarian experiences with Nazism and Stalinism.[57] This is because it focuses on the acceptance of human rights, but also "multicultural and multireligious tolerance."[60] While Müller argues that the European Union has yet to fully acknowledge and embrace constitutional patriotism as an identity, countries do seem to be converging on "political ideals, civic expectations, and policy tools" that fall under the umbrella of constitutional patriotism.[56] Other skeptics note institutional features, such as a lack of focus on meaningful electoral politics, as reasons for why it has not fully been embraced at the supranational level in the European Union. Many see their own national governments as their only hope of electoral accountability.[59] The European Union also faces a question different from a lot of individual countries. While most countries are working "within the framework" of a constitution, the European Union must decide how strongly it will commit to a future of "constitutionalization".[25] As trust in the public institutions continues to decrease, the future of its constitution could also come into question.[61]

Criticisms

Critics have argued that loyalty to democratic values is too weak to preserve a deep bond to unify a state.[62][63] This is because it is missing a key feature of individual identity for modern subjects - nationality, which in turn provides national identity; "essential for realizing important important liberal democratic values such as individual autonomy and social equality."[64] They believe national identity is the base on which political morality can be achieved.[65] In response to this, it has been questioned whether or not the nation should be responsible for the unity of a state.[4]

Vito Breda argued that Religious pluralism curtails reason in constitutional patriotism.[66] Specifically, two issues arise: 1. that some may not be able to accept a secular and rational morality and 2. that some may prioritize religious beliefs.[66] "By inserting the protection of pluralism, perhaps modeled on the liberal safeguard of freedom of faith, constitution patriotism might gain much cognitive strength."[66]

Critics have also argued that the theory focuses too much on a "domestic German agenda," or is "too specifically German."[12][67][68][69] Essentially, its principles are only applicable in its original context: post-war West Germany. Especially when talking about Habermas' original theory, too much is attributed to a domestic German agenda and Habermas' concept of the public sphere to be applied in other, nonspecific situations.[12][67] However, while it is argued that constitutional patriotism is too German, it is also criticized from the another, almost opposite direction. Political theorists have called the constitutional patriotism too abstract.[1][12] It is argued that the concept lacks specificity on a global scale, and has not been thought out enough to be applied to actual cases. This parallels Müller's acknowledgements that "there have been relatively few attempts to define the concept clearly," and "there has been significant disagreement as to whether [it] is a political value in itself or a means to ensure other values".[22]

Müller's responses to criticisms

In response to many of the discussed criticisms, Müller responded with articles in 2006 and 2009, discussing ways in which he feels constitutional patriotism has been misunderstood or objected.

- "Too universalist"- Critics often claim that constitutional patriotism is neither specific enough in providing a reason as to why citizens should follow their own constitution over someone elses, nor does it provide motivation.[4][14] Müller argues instead that constitutional patriotism is not about individuals questioning where they belong, but rather that it is about how they think about their political allegiances within the existing regime.[2]

- Any trace of particularism invalidates universalist aspirations- Critics claim that constitutional patriotism is indistinct from liberal nationalism. However this criticism assumes that pure universalism is possible. As it is not, political allegiances do matter. Additionally, liberal nationalists gravitate toward assimilationist and exclusionary policies to reinforce a sense of national culture, which is against the idea of constitutional patriotism.[2]

- Too particular- Critics state that the theory is bound to its contextual origins in post-war West Germany.[4][14] However, all universal norms must have an origin, pointing to these origins is not the same as disproving an argument which is normative.[2]

- Reification- Critics claim that for constitutional patriotism to exist, there must be a concrete constitution, otherwise they will turn to liberal nationalism. In response, Müller claims that the written existence of a constitution is not as important as a "constitutional culture" which has liberal democratic values and norms which are stabilizing to society, yet which also can be contested.[2]

- Juridification of politics- Critics state that this theory leads to the understanding that politics is ideally the deliberation of judges. Müller responds that protest groups or civil society can influence governments directly rather than going straight to the courts.[2]

- Constitutional patriotism as a civil religion- Critics argue that constitutional patriotism generates chauvinism and can lead to missions similar to McCarthyism, in which traitors to the constitution are persecuted. While these claims are valid, Charles Taylor admits it is "the least dangerous social-political cohesion." More importantly, the norms and values on which constitutional patriotism is based should contain the resources to defend against intolerance.[2][23]

- Dependence on a particular social theory- Critics argue that the theory is too attached to Jürgen Habermas's political thought. However, Müller makes the point that it is important to think of constitutional patriotism as a normatively dependent concept which is dependent on a broad theory of justice. As these broad theories do not always need to be the same —they may change depending on what meaning for constitution patriotism is desired in a specific context—, Habermas does not own the sole view of constitutional patriotism.[2]

- Constitutional patriotism as a form of statist nationalism- Critics state that constitutional patriotism is a form of statist nationalism. Thus, it creates the same problems associated with nationalism, such as political manipulation and irrational loyalty.[70][71] However, Müller counters this with the argument that constitutional patriotism is best understood as "a set of normative beliefs and commitments." Constitutional patriotism does not advocate for a specific type of government or motivate people to behave a certain way, but rather, is a normative idea based on "sharing political space on fair terms."[23]

- Too "modernist"- Thomas Meyer explains this criticism by stating that constitutional patriotism relies too heavily on existing institutions, and is not universally applicable. Müller argues that constitutional patriotism actually allows for a "distancing" from these existing institutions, and nothing about constitutional patriotism is intrinsically 'modernist'.[23][72]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Müller, Jan-Werner (2007). "A general theory of constitutional patriotism". International Journal of Constitutional Law. 6 (1): 72–95. doi:10.1093/icon/mom037.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Müller, Jan-Werner (2009). "Seven Ways to Misunderstand Constitutional Patriotism" (PDF). Notizie di POLITEIA (96): 20–24. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ a b c Müller, Jan-Werner; Scheppele, Kim Lane (2007). "Constitutional Patriotism: An Introduction". International Journal of Constitutional Law. 6: 67–71. doi:10.1093/icon/mom039.

- ^ a b c d e f Ingram, Attracta (1 November 1996). "Constitutional patriotism". Philosophy & Social Criticism. 22 (6): 1–18. doi:10.1177/019145379602200601. S2CID 220879831.

- ^ Katherine, Tonkiss (2013). "Constitutional patriotism, migration and the post-national dilemma". Citizenship Studies. 17 (3–4): 491–504. doi:10.1080/13621025.2013.793083. S2CID 143574972.

- ^ Lacroix, Justine (December 2002). STUDIES.pdf "For a European Constitutional Patriotism" (PDF). Political Studies. 50 (5): 944–958. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00402. S2CID 53641092.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Fossum, John Erik (1 June 2001). "Deep diversity versus constitutional patriotism: Taylor, Habermas and the Canadian constitutional crisis". Ethnicities. 1 (2): 179–206. doi:10.1177/146879680100100202. S2CID 145353467.

- ^ a b c d e Calhoun, Craig J. (2002). "Imagining Solidarity: Cosmopolitanism, Constitutional Patriotism, and the Public Sphere". Public Culture. 14 (1): 147–171. doi:10.1215/08992363-14-1-147. S2CID 144797553. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Habermas, Jürgen. "Citizenship and National Identity".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)as cited in Ingram (1996) - ^ Viroli, Maurizio. For Love of Country.

- ^ Payrow Shabani, Omid A. (2002). "Who's Afraid of Constitutional Patriotism? The Binding Source of Citizenship in Constitutional States". Social Theory and Practice. 28 (3): 419–443. doi:10.5840/soctheorpract200228317. JSTOR 23562054(2002).&searchText=%22Who%27s%20Afraid%20of%20Constitutional%20Patriotism?%20The%20Binding%20Source%20of%20Citizenship%20in%20Constitutional%20States%22&searchText=.&searchText=Social&searchText=Theory&searchText=and&searchText=Practice&searchText=28&searchText=(3):&searchText=419%E2%80%93443.&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3DPayrow%2BShabani%252C%2BOmid%2BA.%2B%25282002%2529.%2B%2522Who%2527s%2BAfraid%2Bof%2BConstitutional%2BPatriotism%253F%2BThe%2BBinding%2BSource%2Bof%2BCitizenship%2Bin%2BConstitutional%2BStates%2522.%2BSocial%2BTheory%2Band%2BPractice%2B28%2B%25283%2529%253A%2B419%25E2%2580%2593443.%26amp%3Bacc%3Don%26amp%3Bwc%3Don%26amp%3Bfc%3Doff.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Müller, Jan-Werner (2006). "On the Origins of Constitutional Patriotism". Contemporary Political Theory. 5 (3): 278–296. doi:10.1057/palgrave.cpt.9300235. S2CID 17560702.

- ^ Jaspers, Karl (1946). The Question of German Guilt.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Payero, Lucia (2012). "Theoretical Misconstructions Used to Support Spanish National Unity: the Introduction of Constitutional Patriotism in Spain" (PDF). Presented at the European Consortium for Political Research Graduate Student Conference 2012, Bremen. Panel: Tackling Political Science Questions using Historical Cases.

- ^ Müller, Jan-Werner (2007). Constitutional Patriotism. Princeton University Press. p. 7.

- ^ Winkler, Heinrich August; Murphy, C. Michelle; Partsch, Cornelius; List, Susan (1994). "Rebuilding of a Nation: The Germans before and after Unification". Daedalus. 123 (1): 107–127. JSTOR 20027216.

- ^ Habermas, Jürgen (1997). A Berlin republic : writings on Germany. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. xvi. ISBN 978-0-8032-2381-3.

- ^ a b Habermas, Jürgen (1976). Können komplexe Gesellschaften eine vernünftige Identität ausbilden?. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag. pp. 92–126. as cited in Cronin (2003)

- ^ Habermas, Jürgen (1994). Struggles for Recognition in the Democratic Constitutional State. Princeton University Press. pp. 107–148. as cited in Müller 2007

- ^ "Publications of Jan-Werner Müller" (PDF). Princeton. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ a b Müller, Jan-Werner (2007). Constitutional Patriotism. Princeton University Press. pp. 1–15.

- ^ a b Müller, Jan-Werner; Scheppele, K. L. (20 December 2007). "Constitutional patriotism: An introduction". International Journal of Constitutional Law. 6 (1): 67–71. doi:10.1093/icon/mom039.

- ^ a b c d Müller, Jan-Werner. "Three Objections to Constitutional Patriotism" (PDF). Princeton University Press. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Habermas, Jürgen (1998). Inclusion of the Other. p. 117. ISBN 9780262274555.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Fossum, John. "On the Prospects for a Viable Constitutional Patriotism in Complex Multinational Entities: Canada and the European Union Compared" (PDF). University of Oslo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ Muro, Diego; Quiroga, Alexander (2005). "Spanish Nationalism: Ethnic or Civic" (PDF). Ethnicities. 9 (5): 9–29. doi:10.1177/1468796805049922. S2CID 144193279.

- ^ a b c Ballester, Mateo. "The Reception of Constitutional Patriotism by the Spanish Left" (PDF). Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ Kleiner-Liebau, Desiree (2009). Migration and the Construction of National Identity in Spain. Spain: Iberoamericana Editorial. pp. 65–66.

- ^ Balfour, Sebastian (2005). The Politics of Contemporary Spain. New York: Routledge. pp. 123–125.

- ^ Sternberger, Dolf (1990). Verfassungspatriotismus. Frankfurt: Insel. p. 30.

- ^ "Switzerland". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Mammone, edited by Andrea; Godin, Emmanuel; Jenkins, Brian (2012). Mapping the extreme right in contemporary Europe from local to transnational. London: Routledge. pp. 214–221. ISBN 978-0-415-50265-8.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ^ Christin, Thomas; Trechsel, Alexander H. "At the Crossroads of National Identity and Institutional Attachment: Switzerland's EU Integration in Perspective". Essex.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d Eugster, Beatrice; Strijbis, Oliver (December 2011). "The Swiss: a political nation?". Swiss Political Science Review. 17 (4): 394–416. doi:10.1111/j.1662-6370.2011.02029.x.

- ^ a b Cederman, Lars-Erik, ed. (2001). Constructing Europe's identity: the external dimension. Boulder: Lynne Rienner. pp. 89–81. ISBN 978-1-55587-872-6.

- ^ Kristol, William (July 1996). "Toward a Neo-Reaganite Foreign Policy". Foreign Affairs. 75 (July/August 1996): 18–32. doi:10.2307/20047656. JSTOR 20047656. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ Helldahl, Per. "Constitutional Patriotism, Nationalism, and Historicity" (PDF). Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ Allard, Phil. "Manifest Destiny – 'Noble Ideal or Excuse for Imperialist Expansion?'".

- ^ Miller, Robert J. "American Indians and the US Constitution". Flashpoint Magazine.

- ^ Rohan. "Manifest Destiny and the West". San Diego State University.

- ^ "American Indian Heritage Month: Commemoration vs Exploitation". ABC CLIO. ABC CLIO.

- ^ Horton, James Oliver. "Race and the American Constitution". The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

- ^ Douglas, Frederick. "The Constitution and Slavery". Teaching American History.

- ^ Müller, Jan-Werner. Constitutional Patriotism. pp. 76–77.

- ^ "53.a McCarthyism". US History: Pre Columbian to the New Millennium.

- ^ Merritt, Eve Collyer. "The Extraordinary Injustice of McCarthy's America". E-International Relations.

- ^ "McCarthy's Downfall". Mount Holyoke College Website.

- ^ Dubois, W.E.B. "Niagara Movement Speech". Teaching American History.

- ^ King, Martin Luther Jr. (1955-12-05). "MIA Mass Meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church". King Encyclopedia. Stanford University | Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ King Jr., Martin Luther. "I See the Promised Land". So Just.

- ^ a b Spiro, Peter (November 2000). "The New Sovereigntists". Foreign Affairs (November/December 2000). doi:10.2307/20049963. JSTOR 20049963. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ a b Rile Hayward, Clarissa (2007). "Democracy's Identity Problem" (PDF). Constellations. 14 (2): 191. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8675.2007.00432.x. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ Müller, Jan-Werner; Gordon, Philip (2009-02-05). "Constitutional Patriotism". Foreign Affairs (May/June 2008). Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ a b c Iser, Mattias. "Dimensions of a European Constitutional Patriotism". Archived from the original on 7 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Teder, Indrek. "Constitutional Patriotism to Become a Unifying Identity?" (PDF). Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ a b Müller, Jan-Werner. "Is the European Union Converging on Constitutional Patriotism?" (PDF). Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ a b Müller, Jan-Werner. "Constitutional Patriotism Beyond the Nation-State: Human Rights, Constitutional Necessity, and the Limits of Pluralism" (PDF). Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Lacroix, Justine. "For a European Constitutional Patriotism" (PDF). Retrieved 8 November 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Kumm, Matias. "Why Europeans Will Not Embrace Constitutional Patriotism" (PDF). Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ Hafez, Kai (2014). Islam in "liberal" Europe : freedom, equality, and intolerance. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 99. ISBN 978-1442229525.

- ^ "Public Opinion in the European Union" (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Yack, Bernard (1996). "The Myth of the Civic Nation". Critical Review. 10 (2): 193–211. doi:10.1080/08913819608443417.as cited in Payrow (2002)

- ^ Mertens, Thomas (1996). "Cosmopolitan and Citizenship: Kant Against Habermas". European Journal of Philosophy. 4 (3): 328–47. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0378.1996.tb00081.x.as cited in Payrow (2002)

- ^ Cronin, Ciaran (2003). "Democracy and Collective Identity: In Defense of Constitutional Patriotism". European Journal of Philosophy. 11 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1111/1468-0378.00172.

- ^ Miller, David (1995). On Nationality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/0198293569.001.0001. ISBN 9780191599910.

- ^ a b c Breda, Vito. "Constitutional Patriotism: A Reasonable Theory of Radical Democracy?". Selected Works. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ a b Turner, Charles (2004). "Jürgen Habermas: European or German?". European Journal of Political Theory. 3 (3): 293–314. doi:10.1177/1474885104043585. S2CID 145281078.

- ^ Miller, David (195). On Nationality. Clarendon Press. p. 163.

- ^ Viroli, Maurizio (1995). For Love of Country. Oxford University Press. pp. 172–175.

- ^ Heywood, Andrew (2000). Key concepts in politics (3rd print. ed.). Basingstoke, Hampshire [u.a.]: Macmillan [u.a.] ISBN 978-0-333-77095-5.

- ^ Orwell, George. "Notes on Nationalism". Secker and Warburg.

- ^ Meyer, Thomas (2004). Die Identität Europas : der EU eine Seele? (Orig.-Ausg., 1. Aufl. ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. ISBN 978-3-518-12355-3.