Wole Soyinka

Wole Soyinka | |

|---|---|

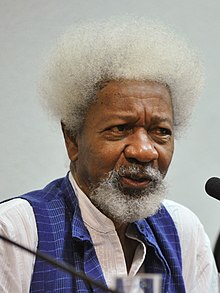

Wole Soyinka in 2018 | |

| Born | Akínwándé Olúwolé Babátúndé Sóyíinká[1] 13 July 1934 Abeokuta, Nigeria Protectorate (now Ogun State, Nigeria) |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Nigerian |

| Education | Abeokuta Grammar School University of Leeds |

| Period | 1957–present |

| Genre |

|

| Subject | Comparative literature |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1986 Academy of Achievement Golden Plate Award 2009 |

| Spouse |

Barbara Dixon

(m. 1957; div. 1962)Olaide Idowu

(m. 1963; div. 1985)Adefolake Doherty (m. 1989) |

| Children | 8 |

Akinwande Oluwole Babatunde Soyinka (Yoruba: Akínwándé Olúwo̩lé Babátúndé S̩óyíinká; born 13 July 1934), known as Wole Soyinka (pronounced [wɔlé ʃójĩnká]), is a Nigerian playwright, poet and essayist. He was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature,[2] the first sub-Saharan African to be honoured in that category.[3] Soyinka was born into a Yoruba family in Abeokuta. In 1954, he attended Government College in Ibadan,[4] and subsequently University College Ibadan and the University of Leeds in England.[5] After studying in Nigeria and the UK, he worked with the Royal Court Theatre in London. He went on to write plays that were produced in both countries, in theatres and on radio. He took an active role in Nigeria's political history and its struggle for independence from Great Britain. In 1965, he seized the Western Nigeria Broadcasting Service studio and broadcast a demand for the cancellation of the Western Nigeria Regional Elections.[citation needed] In 1967, during the Nigerian Civil War, he was arrested by the federal government of General Yakubu Gowon and put in solitary confinement for two years.[6]

Soyinka has been a strong critic of successive Nigerian governments, especially the country's many military dictators, as well as other political tyrannies, including the Mugabe regime in Zimbabwe. Much of his writing has been concerned with "the oppressive boot and the irrelevance of the colour of the foot that wears it".[7] During the regime of General Sani Abacha (1993–98), Soyinka escaped from Nigeria on a motorcycle via the "NADECO Route." Abacha later proclaimed a death sentence against him "in absentia."[7] With civilian rule restored to Nigeria in 1999, Soyinka returned to his nation.

In Nigeria, Soyinka was a Professor of Comparative literature (1975 to 1999) at the Obafemi Awolowo University, then called the University of Ife.[8] With civilian rule restored to Nigeria in 1999, he was made professor emeritus.[6] While in the United States, he first taught at Cornell University as Goldwin Smith professor for African Studies and Theatre Arts from 1988 to 1991[9][10] and then at Emory University, where in 1996 he was appointed Robert W. Woodruff Professor of the Arts. Soyinka has been a Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and has served as scholar-in-residence at NYU's Institute of African American Affairs and at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, California, US.[6][11] He has also taught at the universities of Oxford, Harvard and Yale.[12][13] Soyinka was also a Distinguished Scholar in Residence at Duke University in 2008.[14]

In December 2017, he was awarded the Europe Theatre Prize in the "Special Prize" category[15][16] awarded to someone who has "contributed to the realization of cultural events that promote understanding and the exchange of knowledge between peoples".[17]

Life and work

A descendant of a Remo family of Isara-Remo of Royal pedigree, Soyinka was born the second of seven children, in the city of Abẹokuta, Ogun State, in Nigeria, at that time a British dominion. His siblings are: Atinuke "Tinu" Aina Soyinka, Femi Soyinka, Yeside Soyinka, Omofolabo "Folabo" Ajayi-Soyinka and Kayode Soyinka. His younger sister Folashade Soyinka died on her 1st birthday. His father, Samuel Ayodele Soyinka (whom he called S.A. or "Essay"), was an Anglican minister and the headmaster of St. Peters School in Abẹokuta. Soyinka's mother, Grace Eniola Soyinka (whom he dubbed the "Wild Christian"), owned a shop in the nearby market. She was a political activist within the women's movement in the local community. She was also Anglican. As much of the community followed indigenous Yorùbá religious tradition, Soyinka grew up in a religious atmosphere of syncretism, with influences from both cultures. He was raised in a religious family, attending church services and singing in the choir from an early age; however Soyinka himself became an atheist later in life.[18][19] His father's position enabled him to get electricity and radio at home. He writes extensively about his childhood in one of his memoirs, Aké: The Years of Childhood (1981).[20]

His mother was one of the most prominent members of the influential Ransome-Kuti family: she was the granddaughter of Rev. Canon J. J. Ransome-Kuti, (she was the only daughter of Rev J.J Ransome-Kuti's first daughter, Anne Lape Iyabode Ransome-Kuti) and niece to Olusegun Azariah Ransome-Kuti, Oludotun Ransome-Kuti and niece in-law to Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti. Among Soyinka's first cousins once removed were the musician Fela Kuti, the human rights activist Beko Ransome-Kuti, politician Olikoye Ransome-Kuti and activist Yemisi Ransome-Kuti.[21]

In 1940, after attending St. Peter's Primary School in Abeokuta, Soyinka went to Abeokuta Grammar School, where he won several prizes for literary composition.[citation needed] In 1946 he was accepted by Government College in Ibadan, at that time one of Nigeria's elite secondary schools.[citation needed]

After finishing his course at Government College in 1952, he began studies at University College Ibadan (1952–54), affiliated with the University of London.[citation needed] He studied English literature, Greek, and Western history. Among his lecturers was Molly Mahood, a British literary scholar.[22] In the year 1953–54, his second and last at University College, Soyinka began work on "Keffi's Birthday Treat", a short radio play for Nigerian Broadcasting Service that was broadcast in July 1954.[23] While at university, Soyinka and six others founded the Pyrates Confraternity, an anti-corruption and justice-seeking student organisation, the first confraternity in Nigeria.

Later in 1954, Soyinka relocated to England, where he continued his studies in English literature, under the supervision of his mentor Wilson Knight at the University of Leeds (1954–57).[citation needed] He met numerous young, gifted British writers. Before defending his B.A., Soyinka began publishing and worked as an editor for the satirical magazine The Eagle. He wrote a column on academic life, often criticising his university peers.

Early career

After graduating with an upper second-class degree, Soyinka remained in Leeds and began working on an MA.[24] He intended to write new works combining European theatrical traditions with those of his Yorùbá cultural heritage. His first major play, The Swamp Dwellers (1958), was followed a year later by The Lion and the Jewel, a comedy that attracted interest from several members of London's Royal Court Theatre. Encouraged, Soyinka moved to London, where he worked as a play reader for the Royal Court Theatre. During the same period, both of his plays were performed in Ibadan. They dealt with the uneasy relationship between progress and tradition in Nigeria.[25]

In 1957, his play The Invention was the first of his works to be produced at the Royal Court Theatre.[26] At that time his only published works were poems such as "The Immigrant" and "My Next Door Neighbour", which were published in the Nigerian magazine Black Orpheus.[27] This was founded in 1957 by the German scholar Ulli Beier, who had been teaching at the University of Ibadan since 1950.[28]

Soyinka received a Rockefeller Research Fellowship from University College in Ibadan, his alma mater, for research on African theatre, and he returned to Nigeria. After its fifth issue (November 1959), Soyinka replaced Jahnheinz Jahn to become coeditor for the literary periodical Black Orpheus (its name derived from a 1948 essay by Jean-Paul Sartre, "Orphée Noir", published as a preface to Anthologie de la nouvelle poésie nègre et malgache, edited by Léopold Senghor).[29] He produced his new satire, The Trials of Brother Jero. His work A Dance of The Forest (1960), a biting criticism of Nigeria's political elites, won a contest that year as the official play for Nigerian Independence Day. On 1 October 1960, it premiered in Lagos as Nigeria celebrated its sovereignty. The play satirizes the fledgling nation by showing that the present is no more a golden age than was the past. Also in 1960, Soyinka established the "Nineteen-Sixty Masks", an amateur acting ensemble to which he devoted considerable time over the next few years.

Soyinka wrote the first full-length play produced on Nigerian television. Entitled My Father’s Burden and directed by Segun Olusola, the play was featured on the Western Nigeria Television (WNTV) on 6 August 1960.[30][31] Soyinka published works satirising the "Emergency" in the Western Region of Nigeria, as his Yorùbá homeland was increasingly occupied and controlled by the federal government. The political tensions arising from recent post-colonial independence eventually led to a military coup and civil war (1967–70).

With the Rockefeller grant, Soyinka bought a Land Rover, and he began travelling throughout the country as a researcher with the Department of English Language of the University College in Ibadan. In an essay of the time, he criticised Leopold Senghor's Négritude movement as a nostalgic and indiscriminate glorification of the black African past that ignores the potential benefits of modernisation. He is often quoted as having said, "A tiger doesn't proclaim his tigritude, he pounces." But in fact, Soyinka wrote in a 1960 essay for the Horn: "the duiker will not paint 'duiker' on his beautiful back to proclaim his duikeritude; you’ll know him by his elegant leap."[32][33] In Death and the King Horsemen he states: "The elephant trails no tethering-rope; that king is not yet crowned who will peg an elephant."

In December 1962, Soyinka's essay "Towards a True Theater" was published. He began teaching with the Department of English Language at Obafemi Awolowo University in Ifẹ. He discussed current affairs with "négrophiles," and on several occasions openly condemned government censorship. At the end of 1963, his first feature-length movie, Culture in Transition, was released. In April 1964 The Interpreters, "a complex but also vividly documentary novel",[34] was published in London.

That December, together with scientists and men of theatre, Soyinka founded the Drama Association of Nigeria. In 1964 he also resigned his university post, as a protest against imposed pro-government behaviour by the authorities. A few months later, in 1965, he was arrested for the first time, charged with holding up a radio station at gunpoint (as described in his 2006 memoir You Must Set Forth at Dawn)[35] and replacing the tape of a recorded speech by the premier of Western Nigeria with a different tape containing accusations of election malpractice. Soyinka was released after a few months of confinement, as a result of protests by the international community of writers. This same year he wrote two more dramatic pieces: Before the Blackout and the comedy Kongi’s Harvest. He also wrote The Detainee, a radio play for the BBC in London. His play The Road premiered in London at the Commonwealth Arts Festival,[36] opening on 14 September 1965 at the Theatre Royal.[37] At the end of the year, he was promoted to headmaster and senior lecturer in the Department of English Language at University of Lagos.

Soyinka's political speeches at that time criticised the cult of personality and government corruption in African dictatorships. In April 1966, his play Kongi’s Harvest was produced in revival at the World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal.[citation needed] The Road was awarded the Grand Prix. In June 1965, he produced his play The Lion and The Jewel for Hampstead Theatre Club in London.

Civil war and imprisonment

After becoming chief of the Cathedral of Drama at the University of Ibadan, Soyinka became more politically active. Following the military coup of January 1966, he secretly and unofficially met with the military governor Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu in the Southeastern town of Enugu (August 1967), to try to avert civil war.[citation needed] As a result, he had to go into hiding.

He was imprisoned for 22 months[38] as civil war ensued between the Federal Government of Nigeria and the Biafrans. Through refuse materials such as books, pens, and paper, he still wrote a significant body of poems and notes criticising the Nigerian government while in prison.[39]

Despite his imprisonment, in September 1967, his play, The Lion and The Jewel, was produced in Accra. In November The Trials of Brother Jero and The Strong Breed were produced in the Greenwich Mews Theatre in New York. He also published a collection of his poetry, Idanre and Other Poems. It was inspired by Soyinka's visit to the sanctuary of the Yorùbá deity Ogun, whom he regards as his "companion" deity, kindred spirit, and protector.[39]

In 1968, the Negro Ensemble Company in New York produced Kongi’s Harvest.[citation needed] While still imprisoned, Soyinka translated from Yoruba a fantastical novel by his compatriot D. O. Fagunwa, entitled The Forest of a Thousand Demons: A Hunter's Saga.

Release and literary production

In October 1969, when the civil war came to an end, amnesty was proclaimed, and Soyinka and other political prisoners were freed.[citation needed] For the first few months after his release, Soyinka stayed at a friend's farm in southern France, where he sought solitude. He wrote The Bacchae of Euripides (1969), a reworking of the Pentheus myth.[40] He soon published in London a book of poetry, Poems from Prison. At the end of the year, he returned to his office as Headmaster of Cathedral of Drama in Ibadan.

In 1970, he produced the play Kongi's Harvest, while simultaneously adapting it as a film of the same title. In June 1970, he finished another play, called Madmen and Specialists.[citation needed] Together with the group of 15 actors of Ibadan University Theatre Art Company, he went on a trip to the United States, to the Eugene O'Neill Memorial Theatre Center in Waterford, Connecticut, where his latest play premiered. It gave them all experience with theatrical production in another English-speaking country.

In 1971, his poetry collection A Shuttle in the Crypt was published. Madmen and Specialists was produced in Ibadan that year.[41] Soyinka travelled to Paris to take the lead role as Patrice Lumumba, the murdered first Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo, in the production of his Murderous Angels.

In April 1971, concerned about the political situation in Nigeria, Soyinka resigned from his duties at the University in Ibadan, and began years of voluntary exile.[citation needed] In July in Paris, excerpts from his well-known play The Dance of The Forests were performed.

In 1972, he was awarded an Honoris Causa doctorate by the University of Leeds.[citation needed] Soon thereafter, his novel Season of Anomy (1972) and his Collected Plays (1972) were both published by Oxford University Press. His powerful autobiographical work The Man Died, a collection of notes from prison, was also published that year.[42] In 1973 the National Theatre, London, commissioned and premiered the play The Bacchae of Euripides.[40] In 1973 his plays Camwood on the Leaves and Jero's Metamorphosis were first published. From 1973 to 1975, Soyinka spent time on scientific studies.[clarification needed] He spent a year as a visiting fellow at Churchill College, Cambridge University [clarification needed]1973–74 and wrote Death and the King's Horseman, which had its first reading at Churchill College (which Dapo Ladimeji and Skip Gates attended), and gave a series of lectures at a number of European universities.

In 1974, his Collected Plays, Volume II was issued by Oxford University Press. In 1975 Soyinka was promoted to the position of editor for Transition, a magazine based in the Ghanaian capital of Accra, where he moved for some time.[citation needed] He used his columns in Transition to criticise the "negrophiles" (for instance, his article "Neo-Tarzanism: The Poetics of Pseudo-Transition") and military regimes. He protested against the military junta of Idi Amin in Uganda. After the political turnover in Nigeria and the subversion of Gowon's military regime in 1975, Soyinka returned to his homeland and resumed his position at the Cathedral of Comparative Literature at the University of Ife.

In 1976, he published his poetry collection Ogun Abibiman, as well as a collection of essays entitled Myth, Literature and the African World.[citation needed] In these, Soyinka explores the genesis of mysticism in African theatre and, using examples from both European and African literature, compares and contrasts the cultures. He delivered a series of guest lectures at the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana in Legon. In October, the French version of The Dance of The Forests was performed in Dakar, while in Ife, his play Death and The King’s Horseman premièred.

In 1977, Opera Wọnyọsi, his adaptation of Bertolt Brecht's The Threepenny Opera, was staged in Ibadan. In 1979 he both directed and acted in Jon Blair and Norman Fenton's drama The Biko Inquest, a work based on the life of Steve Biko, a South African student and human rights activist who was beaten to death by apartheid police forces.[citation needed] In 1981 Soyinka published his autobiographical work Aké: The Years of Childhood, which won a 1983 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award.[citation needed]

Soyinka founded another theatrical group called the Guerrilla Unit. Its goal was to work with local communities in analysing their problems and to express some of their grievances in dramatic sketches. In 1983 his play Requiem for a Futurologist had its first performance at the University of Ife. In July, one of his musical projects, the Unlimited Liability Company, issued a long-playing record entitled I Love My Country, on which several prominent Nigerian musicians played songs composed by Soyinka. In 1984, he directed the film Blues for a Prodigal; his new play A Play of Giants was produced the same year.

During the years 1975–84, Soyinka was more politically active. At the University of Ife, his administrative duties included the security of public roads. He criticized the corruption in the government of the democratically elected President Shehu Shagari. When he was replaced by the army general Muhammadu Buhari, Soyinka was often at odds with the military. In 1984, a Nigerian court banned his 1972 book The Man Died: Prison Notes.[43] In 1985, his play Requiem for a Futurologist was published in London by André Deutsch.

Since 1986

Soyinka was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986,[44][45] becoming the first African laureate. He was described as one "who in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence". Reed Way Dasenbrock writes that the award of the Nobel Prize in Literature to Soyinka is "likely to prove quite controversial and thoroughly deserved". He also notes that "it is the first Nobel Prize awarded to an African writer or to any writer from the 'new literatures' in English that have emerged in the former colonies of the British Empire."[46] His Nobel acceptance speech, "This Past Must Address Its Present", was devoted to South African freedom-fighter Nelson Mandela. Soyinka's speech was an outspoken criticism of apartheid and the politics of racial segregation imposed on the majority by the Nationalist South African government. In 1986, he received the Agip Prize for Literature.

In 1988, his collection of poems Mandela's Earth, and Other Poems was published, while in Nigeria another collection of essays entitled Art, Dialogue and Outrage: Essays on Literature and Culture appeared. In the same year, Soyinka accepted the position of Professor of African Studies and Theatre at Cornell University.[47] In 1990, a third novel, inspired by his father's intellectual circle, Isara: A Voyage Around Essay, appeared. In July 1991 the BBC African Service transmitted his radio play A Scourge of Hyacinths, and the next year (1992) in Siena (Italy), his play From Zia with Love had its premiere.[citation needed] Both works are very bitter political parodies, based on events that took place in Nigeria in the 1980s. In 1993 Soyinka was awarded an honorary doctorate from Harvard University. The next year another part of his autobiography appeared: Ibadan: The Penkelemes Years (A Memoir: 1946–1965). The following year his play The Beatification of Area Boy was published. In October 1994, he was appointed UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador for the Promotion of African culture, human rights, freedom of expression, media and communication.[citation needed]

In November 1994, Soyinka fled from Nigeria through the border with Benin and then to the United States.[citation needed] In 1996 his book The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Narrative of the Nigerian Crisis was first published. In 1997 he was charged with treason by the government of General Sani Abacha.[citation needed] The International Parliament of Writers (IPW) was established in 1993 to provide support for writers victimized by persecution. Soyinka became the organization's second president from 1997 to 2000.[48][49] In 1999 a new volume of poems by Soyinka, entitled Outsiders, was released. That same year, a BBC-commissioned play called "Document of Identity" aired on BBC Radio 3, telling the lightly-fictionalized story of the problems his daughter's family encountered during a stopover in Britain when they fled Nigeria for the US in 1997; her baby was born prematurely in London and became a stateless person.[7]

His play King Baabu premièred in Lagos in 2001,[50] a political satire on the theme of African dictatorship.[50] In 2002 a collection of his poems, Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known, was published by Methuen. In April 2006, his memoir You Must Set Forth at Dawn was published by Random House. In 2006 he cancelled his keynote speech for the annual S.E.A. Write Awards Ceremony in Bangkok to protest the Thai military's successful coup against the government.[51]

In April 2007, Soyinka called for the cancellation of the Nigerian presidential elections held two weeks earlier, beset by widespread fraud and violence.[citation needed] In the wake of the Christmas Day (2009) bombing attempt on a flight to the US by a Nigerian student who had become radicalised in Britain, Soyinka questioned the United Kingdom's social logic that allows every religion to openly proselytise their faith, asserting that it is being abused by religious fundamentalists thereby turning England into a cesspit for the breeding of extremism.[citation needed] He supported the freedom of worship but warned against the consequence of the illogic of allowing religions to preach apocalyptic violence.[52]

In August 2014, Soyinka delivered a recording of his speech "From Chibok with Love" to the World Humanist Congress in Oxford, hosted by the International Humanist and Ethical Union and the British Humanist Association.[citation needed] The Congress theme was Freedom of thought and expression: Forging a 21st Century Enlightenment. He was awarded the 2014 International Humanist Award.[53][54] He served as scholar-in-residence at NYU’s Institute of African American Affairs.[11]

Soyinka opposes allowing Fulani herdsmen the ability to graze their cattle on open land in southern, Christian-dominated Nigeria and believes these herdsmen should be declared terrorists to enable the restriction of their movements.[55]

Personal life

Soyinka has been married three times and divorced twice. He has children from his three marriages. His first marriage was in 1958 to the late British writer, Barbara Dixon, whom he met at the University of Leeds in the 1950s. Barbara was the mother of his first son, Olaokun. His second marriage was in 1963 to Nigerian librarian Olaide Idowu,[56] with whom he had three daughters, Moremi, Iyetade (deceased),[57] Peyibomi, and a second son, Ilemakin. Soyinka married Folake Doherty in 1989.[7] [58]

In 2014, he revealed his battle with prostate cancer.[59]

Legacy and honours

The Wole Soyinka Annual Lecture Series was founded in 1994 and "is dedicated to honouring one of Nigeria and Africa's most outstanding and enduring literary icons: Professor Wole Soyinka".[60] It is organised by the National Association of Seadogs (Pyrates Confraternity), which organisation Soyinka with six other students founded in 1952 at the then University College Ibadan.[61]

In 2011, the African Heritage Research Library and Cultural Centre built a writers' enclave in his honour.[citation needed] It is located in Adeyipo Village, Lagelu Local Government Area, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. The enclave includes a Writer-in-Residence Programme that enables writers to stay for a period of two, three or six months, engaging in serious creative writing. In 2013, he visited the Benin Moat as the representative of UNESCO in recognition of the Naija seven Wonders project.[62] He is currently the consultant for the Lagos Black Heritage Festival, with the Lagos State deeming him as the only person who could bring out the aims and objectives of the Festival to the people.[63]

In 2014, the collection Crucible of the Ages: Essays in Honour of Wole Soyinka at 80, edited by Ivor Agyeman-Duah and Ogochwuku Promise, was published by Bookcraft in Nigeria and Ayebia Clarke Publishing in the UK, with tributes and contributions from Nadine Gordimer, Toni Morrison, Ama Ata Aidoo, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Henry Louis Gates, Jr, Margaret Busby, Kwame Anthony Appiah, Ali Mazrui, Sefi Atta, and others.[64][65]

In 2018, Henry Louis Gates, Jr tweeted that Nigerian filmmaker and writer, Onyeka Nwelue, visited him in Harvard and was making a documentary film on Wole Soyinka.[66] As part of efforts to mark his 84th birthday, a collectiom of poems titled 84 Delicious Bottles of Wine was published for Wole Soyinka, edited by Onyeka Nwelue and Odega Shawa. Among the notable contributors was Adamu Usman Garko, award winning teenage essayist, poet and writer.[67]

- 1973: Honorary D.Litt., University of Leeds[68]

- 1973–74: Overseas Fellow, Churchill College, Cambridge

- 1983: Elected an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature[69]

- 1983: Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, United States

- 1986: Nobel Prize for Literature

- 1986: Agip Prize for Literature

- 1986: Commander of the Order of the Federal Republic (CFR).

- 1990: Benson Medal from Royal Society of Literature

- 1993: Honorary doctorate, Harvard University

- 2002: Honorary fellowship, SOAS[70]

- 2005: Honorary doctorate degree, Princeton University[71]

- 2005: Conferred with the chieftaincy title of the Akinlatun of Egbaland by the Oba Alake of the Egba clan of Yorubaland. Soyinka became a tribal aristocrat by way of this, one vested with the right to use the Yoruba title Oloye as a pre-nominal honorific.[72]

- 2009: Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement[73]

- 2013: Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, Lifetime Achievement, United States[74]

- 2014: International Humanist Award[53][54]

- 2017: Joins the University of Johannesburg, South Africa, as a Distinguished Visiting Professor in the Faculty of Humanities[75]

- 2017 "Special Prize" of the Europe Theatre Prize[17]

- 2018, University of Ibadan renamed its arts theater to Wole Soyinka Theatre.[76]

- 2018: Honorary Doctorate Degree of Letters, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta (FUNAAB).[77]

Works

Plays

- Keffi's Birthday Treat (1954)

- The Invention (1957)

- The Swamp Dwellers (1958)

- A Quality of Violence (1959)[78]

- The Lion and the Jewel (1959)

- The Trials of Brother Jero

- A Dance of the Forests (1960)

- My Father's Burden (1960)

- The Strong Breed (1964)

- Before the Blackout (1964)

- Kongi's Harvest (1964)

- The Road (1965)

- Madmen and Specialists (1970)

- The Bacchae of Euripides (1973)

- Camwood on the Leaves (1973)

- Jero's Metamorphosis (1973)

- Death and the King's Horseman (1975)

- Opera Wonyosi (1977)

- Requiem for a Futurologist (1983)

- A Play of Giants (1984)

- Childe Internationale (1987)[79][80]

- From Zia with Love (1992)

- The Detainee (radio play)

- A Scourge of Hyacinths (radio play)

- The Beatification of Area Boy (1996)

- Document of Identity (radio play, 1999)

- King Baabu (2001)

- Etiki Revu Wetin

- Alapata Apata (2011)

- "Thus Spake Orunmila" (short piece; in Sixty-Six Books (2011)[81]

Novels

- The Interpreters (1964)

- Season of Anomy (1972)

Short stories

- A Tale of Two (1958)

- Egbe's Sworn Enemy (1960)

- Madame Etienne's Establishment (1960)

Memoirs

- The Man Died: Prison Notes (1972)

- Aké: The Years of Childhood (1981)

- Ibadan: The Penkelemes Years: a memoir 19466–5 (1989)

- Isara: A Voyage around Essay (1990)

- You Must Set Forth at Dawn (2006)

Poetry collections

- Telephone Conversation (1963) (appeared in Modern Poetry in Africa)

- Idanre and other poems (1967)

- A Big Airplane Crashed Into The Earth (original title Poems from Prison) (1969)

- A Shuttle in the Crypt (1971)

- Ogun Abibiman (1976)

- Mandela's Earth and other poems (1988)

- Early Poems (1997)

- Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known (2002)

Essays

- Towards a True Theater (1962)

- Culture in Transition (1963)

- Neo-Tarzanism: The Poetics of Pseudo-Transition

- A Voice That Would Not Be Silenced

- Art, Dialogue, and Outrage: Essays on Literature and Culture (1988)

- From Drama and the African World View (1976)

- Myth, Literature, and the African World (1976)[82]

- The Blackman and the Veil (1990)[83]

- The Credo of Being and Nothingness (1991)

- The Burden of Memory – The Muse of Forgiveness (1999)

- A Climate of Fear (the BBC Reith Lectures 2004, audio and transcripts)

- New Imperialism (2009)[84]

- Of Africa (2012)[85][86]

- Beyond Aesthetics: Use, Abuse, and Dissonance in African Art Traditions (2019)

Movies

- Kongi's Harvest

- Culture in Transition

- Blues for a Prodigal

Translations

- The Forest of a Thousand Demons: A Hunter’s Saga (1968; a translation of D. O. Fagunwa's Ògbójú Ọdẹ nínú Igbó Irúnmalẹ̀)

- In the Forest of Olodumare (2010; a translation of D. O. Fagunwa's Igbo Olodumare)

See also

- Nigerian literature

- List of 20th-century writers

- List of African writers

- Black Nobel Prize laureates

- Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature in Africa

- List of Nigerian writers

References

- ^ Tyler Wasson; Gert H. Brieger (1 January 1987). Nobel Prize Winners: An H.W. Wilson Biographical Dictionary, Volume 1. The University of Michigan, U.S.A. p. 993. ISBN 9780824207564. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1986 Wole Soyinka". The Nobel Prize. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ "Africa's Nobel Prize winners: A list". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1986". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ Soyinka, Wole (2000) [1981]. Aké: The Years of Childhood. Nigeria: Methuen. p. 1. ISBN 9780413751904. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Theresia de Vroom, "The Many Dimensions of Wole Soyinka" Archived 5 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Vistas, Loyola Marymount University. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d Maya Jaggi (2 November 2002). "Ousting monsters". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ "Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife » Brief History of the University". www.oauife.edu.ng. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ "Soyinka, Wole 1934–". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/25283/019_37.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- ^ a b "Nobel Laureate Soyinka at NYU for Events in October", News Release, NYU, 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Profile of Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka" (PDF). The University of Alberta. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Posey, Jacquie (18 November 2004). "Nigerian Writer, Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka to Speak at Penn". The University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ "SOYINKA ON STAGE". Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ "Wole Soyinka Wins The Europe Theatre Prize - PM NEWS Nigeria". PM NEWS Nigeria. 12 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ "Soyinka Wins 2017 Europe Theatre Prize". Concise News. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Wole Soyinka to receive Europe Theatre Prize 2017". James Murua's Literature Blog. 14 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ "Wole Soyinka Biography and Interview". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ Wole Soyinka (2007). Climate of Fear: The Quest for Dignity in a Dehumanized World. Random House LLC. p. 119. ISBN 9780307430823.

I already had certain agnostic tendencies—which would later develop into outright atheistic convictions— so it was not that I believed in any kind of divine protection.

- ^ Wole Soyinka (1981). Ake: The Years of Childhood. ISBN 9780679725404. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Maya Jaggi, "The voice of conscience", The Guardian, 28 May 2007.

- ^ Lyn Innes (26 March 2017). "Molly Mahood obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ James Gibbs (eds), Critical Perspectives on Wole Soyinka, Three Continents Press, 1980, p. 21.

- ^ James Gibbs (1986). Wole Soyinka. Basingstoke: Macmillan. p. 3. ISBN 9780333305287.

- ^ "Wole Soyinka", The New York Times, 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Wole Soyinka". African Biography. Detroit, MI: Gale (published 2 December 2006). 1999. ISBN 978-0-7876-2823-9.

- ^ "Wole Soyinka", Book Rags (n.d.)

- ^ "Ulli Beier" (obituary), The Telegraph, 12 May 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Peter Benson, Black Orpheus, Transition, and Modern Cultural Awakening in Africa, University of California Press, 1986, p. 30.

- ^ Uzor Maxim Uzoatu (5 October 2013). "The Essential Soyinka Timeline". Premium Times. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ "WOLE SOYINKA, Nigeria's First Nobel Laureate". 13 July 2013. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ Obiajuru Maduakor (1986). "Soyinka as a Literary Critic". Research in African Literatures. 17 (1): 1–38. JSTOR 3819421.

- ^ "Tigritude". This Analog Life. 5 August 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Douglas Killam and Ruth Rowe (eds), The Companion to African Literature, Oxford: James Currey/Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000, p. 275.

- ^ Margaret Busby, "Marvels of the holy hour", The Guardian, 26 May 2007.

- ^ "Commonwealth Arts Festival", Black Plays Archive, National Theatre.

- ^ "Road, The", Black Plays Archive, National Theatre.

- ^ "Wole Soyinka: Nigeria's Nobel Laureate", African Voices, CNN, 27 July 2009.

- ^ a b Wole Soyinka 2006, You Must Set Forth at Dawn, p. 6.

- ^ a b Killam and Rowe (eds), The Companion to African Literature (2000), p. 276.

- ^ Christopher J. Lee, "Reading Wole Soyinka's 'Madmen and Specialists' in a Time of Pandemic", Warscapes, 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Wole Soyinka | Biographical", The Nobel Prize.

- ^ Gibbs (1986). Wole Soyinka. Macmillan. pp. 16–17.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1986 | Wole Soyinka", Nobelprize.org, 23 August 2010.

- ^ "Wole Soyinka: A Chronology". African Postcolonial Literature in English. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Dasenbrock, Reed Way (January 1987). "Wole Soyinka's Nobel Prize". World Literature Today. 61 (1).

- ^ Petri Liukkonen. "Wole Soyinka". Books and Writers. Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015.

- ^ "International Parliament of Writers". Seven Stories Press. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ "Wole Soyinka, Writer "Rights and Relativity: The Interplay of Cultures"". Avenali lecture; The University of California, Berkeley. 1 February 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ a b Eniwoke Ibagere, "Nigeria's Soyinka back on stage", BBC News, 6 August 2005.

- ^ S. P. Somtow, "Why artistic freedom matters" Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The Nation, 16 November 2006.

- ^ Duncan Gardham, "Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka says England is 'cesspit' of extremism", Daily Telegraph, 1 February 2010.

- ^ a b "Wole Soyinka's International Humanist Award acceptance speech – full text". International Humanist and Ethical Union. 12 August 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Wole Soyinka wins International Humanist Award". British Humanist Association. 10 August 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ "Fighting between Nigerian farmers and herders is getting worse". The Economist. 7 June 2018.

- ^ The Who's Who of Nobel Prize Winners, 1901-1995. Oryx Press. 1996. p. 89. ISBN 9780897748995. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ^ "Nobel Laureate Soyinka's Daughter Dies". New York: Sahara Reporters. 29 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ "Wole Soyinka". NNDB. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Wole Oyebade; Charles Coffie Gyamfi (25 November 2014). "Nigeria: My Battle With Prostate Cancer - Wole Soyinka". The Guardian. Lagos. Retrieved 4 April 2015 – via All Africa.

- ^ "Wole Soyinka Lecture Series". National Association of Seadogs (Pyrates Confraternity). Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ "History of NAS". www.nas-int.org. National Association of Seadogs (Pyrates Confraternity). Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ "Naija 7 wonders commends Wole Soyinka for Benin Moat visit", The Nation, 2 March 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ "Lagos Black Festival: From Imitation: Tune to Indigenous Innovative music" Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, This Day Live, 4 May 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ A. B. Assensoh and Yvette M. Alex-Assensoh, "Celebrating Soyinka at 80", New African, 25 June 2014.

- ^ Afam Akeh, "Wole Soyinka at 80", Centre for African Poetry, 22 July 2015.

- ^ "ONYEKA NWELUE'S NEW FILM FEATURE "WOLE SOYINKA: A GOD AND THE BIAFRANS" TO BE PREVIEWED AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY JULY 13TH". Simple. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ^ "ADAMU USMAN GARKO". WRR PUBLISHERS LTD. 10 December 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Honorary Degree, Leeds African Studies Bulletin 19 (November 1973), pp. 1–2.

- ^ "Current RSL Fellows". The Royal Society of Literature. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ "SOAS Honorary Fellows". SOAS.

- ^ Eric Quiñones (31 May 2005). "Princeton University – Princeton awards six honorary degrees". Princeton.edu. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Call national conference on Alamieyeseigha — Soyinka". Sunday Tribune. 27 November 2005. Archived from the original on 3 January 2006. Retrieved 13 December 2005.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards - The 80th Annual".

- ^ "Nobel Laureate prize winner, Prof Wole Soyinka, joins UJ", University of Johannesburg, 28 March 2017.

- ^ siteadmin (30 July 2018). "UI Renames Its Arts Theatre 'Wole Soyinka Theatre'". Sahara Reporters. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ Sowole, Adeniyi (26 November 2018). "Awards: FUNAAB My Last Bus Stop, Says Soyinka". Olajide Fabamise. Leadership. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ "Wole Soyinka". Writer's History. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Adie Vanessa Offiong (23 August 2015). "Soyinka's 'Childe Internationale' for stage in Abuja". DailyTrust.

- ^ James Gibbs; Bernth Lindfors (1993). Research on Wole Soyinka (Comparative studies in African/Caribbean literature series). Africa World Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-865-4321-92.

- ^ "Sixty-Six Books, One Hundred Artists, One New Theatre", Bush Theatre, October 2011.

- ^ Thomas Cassirer; Wole Soyinka (1978). "Myth, Literature and the African World by Wole Soyinka. Review". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 11 (4). Boston University African Studies Center: 755–757. doi:10.2307/217214. JSTOR 217214.

- ^ Wole Soyinka (1993). The Blackman and the Veil: A Century on; And, Beyond the Berlin Wall: Lectures Delivered by Wole Soyinka on 31 August and 1 September 1990. SEDCO. ISBN 978-9964-72-121-3. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ New Imperialism By Wole Soyinka. 2009. ISBN 978-9987-08-055-7. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Wole Soyinka (November 2012). Of Africa. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300-14-046-0.

- ^ Adam Hochschild (22 November 2012). "Assessing Africa – 'Of Africa,' by Wole Soyinka". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

Further reading

- James Gibbs (1980). Critical Perspective on Wole Soyinka (Critical Perspectives). Three Continents Press. ISBN 978-0-914478-49-2.

- James Gibbs (1986). Wole Soyinka. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 9780333305287.

- Eldred Jones (1987). The Writing of Wole Soyinka. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-435080-21-1.

- M. Rajeshwar (1990). Novels of Wole Soyinka. Stosius Inc/Advent Books Division. ISBN 978-8-185218-21-2.

- Derek Wright (1996). Wole Soyinka : Life, Work, and Criticism. York Press. ISBN 978-1-896761-01-5.

- Gerd Meuer (2008). Journeys around and with Kongi - half a century on the road with Wole Soyinka: a pan-afropean or pan-eurafrican book. Reche. ISBN 978-3-929566-73-4.

- Bankole Olayebi (2004), WS: A Life In Full, Bookcraft; biography of Soyinka.

- Ilori, Oluwakemi Atanda (2016), The theatre of Wole Soyinka: Inside the Liminal World of Myth, Ritual and Postcoloniality. PhD thesis, University of Leeds.

- Mpalive-Hangson Msiska (2007), Postcolonial Identity in Wole Soyinka (Cross/Cultures 93). Amsterdam-New York, NY: Editions Rodopi B.V. ISBN 978-9042022584

- Yemi D. Ogunyemi (2009), The Literary/Political Philosophy of Wole Soyinka. ISBN 1-60836-463-1

- Yemi D. Ogunyemi (2017), The Aesthetic and Moral Art of Wole Soyinka (Academica Press, London-Washington) ISBN 978-1-68053-034-6

- Carpenter, C. A. (1981). "Studies of Wole Soyinka's Drama: An International Bibliography". Modern Drama 24(1), 96–101. doi:10.1353/mdr.1981.0042.

External links

- Wole Soyinka papers, 1966-1996. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- "Biography: Wole Soyinka", Nobel Prize profile, 1986

- "Wole Soyinka" Profile, Presidential Lectures, Stanford University

- 1934 births

- Living people

- 20th-century Nigerian dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century essayists

- 20th-century Nigerian novelists

- 20th-century Nigerian philosophers

- 20th-century Nigerian poets

- 20th-century translators

- 21st-century dramatists and playwrights

- 21st-century essayists

- 21st-century Nigerian novelists

- 21st-century Nigerian poets

- Academics of the University of Oxford

- Alumni of the University of Leeds

- Alumni of University of London Worldwide

- Alumni of the University of London

- Cancer survivors

- Commanders of the Order of the Federal Republic

- Cornell University faculty

- Emory University faculty

- English-language writers from Nigeria

- Fellows of Churchill College, Cambridge

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- Former Anglicans

- Government College, Ibadan alumni

- Granta people

- Harvard University faculty

- Loyola Marymount University faculty

- New York University faculty

- Nigerian academics

- Nigerian atheists

- Nigerian Civil War prisoners of war

- Nigerian dramatists and playwrights

- Nigerian essayists

- Nigerian expatriate academics in the United States

- Nigerian expatriates in the United Kingdom

- Nigerian humanists

- Nigerian male novelists

- Nigerian male poets

- Nigerian memoirists

- Nigerian Nobel laureates

- Nigerian philosophers

- Nigerian prisoners and detainees

- Nigerian speculative fiction writers

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- Obafemi Awolowo University faculty

- Political philosophers

- Prisoners and detainees of Nigeria

- Ransome-Kuti family

- Recipients of the Nigerian National Order of Merit Award

- University of Ibadan alumni

- University of Lagos faculty

- University of Nevada, Las Vegas faculty

- Writers from Abeokuta

- Yale University faculty

- Yoruba–English translators

- Yoruba academics

- Yoruba dramatists and playwrights

- Yoruba novelists

- Yoruba philosophers

- Yoruba poets

- Yoruba writers