Aramaic alphabet

| Aramaic alphabet | |

|---|---|

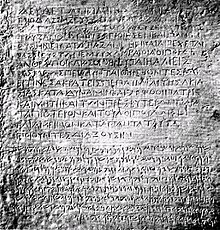

Bilingual Greek and Aramaic inscription by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka the Great at Kandahar, Afghanistan, 3rd century BC | |

| Script type | |

Time period | 800 BC to 600 AD |

| Direction | Right-to-left script |

| Languages | Aramaic, Hebrew, Syriac, Mandaic |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Proto-Sinaitic alphabet

|

Child systems | Hebrew Arabic Nabataean Syriac Palmyrenean Mandaic Pahlavi Sogdian Kharoṣṭhī Georgian (disputed) |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Armi (124), Imperial Aramaic Imperial Aramaic |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Imperial Aramaic |

| U+10840–U+1085F | |

| Ancient Arameans |

|---|

| Syro-Hittite states |

| Aramean kings |

| Aramean cities |

| Sources |

The Aramaic alphabet is adapted from the Phoenician alphabet and became distinctive from it by the 8th century BCE. The letters all represent consonants, some of which are matres lectionis, which also indicate long vowels.

The Aramaic alphabet is historically significant, since virtually all modern Middle Eastern writing systems can be traced back to it, as well as numerous non-Chinese writing systems of Central and East Asia. This is primarily due to the widespread usage of the Aramaic language as both a lingua franca and the official language of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and its successor, the Achaemenid Empire. Among the scripts in modern use, the Hebrew alphabet bears the closest relation to the Imperial Aramaic script of the 5th century BC, with an identical letter inventory and, for the most part, nearly identical letter shapes.

Writing systems that indicate consonants but do not indicate most vowels (like the Aramaic one) or indicate them with added diacritical signs, have been called abjads by Peter T. Daniels to distinguish them from later alphabets, such as Greek, that represent vowels more systematically. This is to avoid the notion that a writing system that represents sounds must be either a syllabary or an alphabet, which implies that a system like Aramaic must be either a syllabary (as argued by Gelb) or an incomplete or deficient alphabet (as most other writers have said); rather, it is a different type.

History

Origins

The earliest inscriptions in the Aramaic language use the Phoenician alphabet. Over time, the alphabet developed into the form shown below. Aramaic gradually became the lingua franca throughout the Middle East, with the script at first complementing and then displacing Assyrian cuneiform as the predominant writing system.

Achaemenid period

Around 500 BC, following the Achaemenid conquest of Mesopotamia under Darius I, Old Aramaic was adopted by the conquerors as the "vehicle for written communication between the different regions of the vast empire with its different peoples and languages. The use of a single official language, which modern scholarship has dubbed Official Aramaic or Imperial Aramaic, can be assumed to have greatly contributed to the astonishing success of the Achaemenids in holding their far-flung empire together for as long as they did."[1]

Imperial Aramaic was highly standardised; its orthography was based more on historical roots than any spoken dialect and was inevitably influenced by Old Persian.

For centuries after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire in 331 BC, Imperial Aramaic—or near enough for it to be recognisable—would remain an influence on the various native Iranian languages. The Aramaic script would survive as the essential characteristics of the Pahlavi writing system.[2]

A group of thirty Aramaic documents from Bactria have been recently discovered. An analysis was published in November 2006. The texts, which were rendered on leather, reflect the use of Aramaic in the 4th century BC Achaemenid administration of Bactria and Sogdiana.[3]

Its widespread usage led to the gradual adoption of the Aramaic alphabet for writing the Hebrew language. Formerly, Hebrew had been written using an alphabet closer in form to that of Phoenician (the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet).

Aramaic-derived scripts

Since the evolution of the Aramaic alphabet out of the Phoenician one was a gradual process, the division of the world's alphabets into those derived from the Phoenician one directly and those derived from Phoenician via Aramaic is somewhat artificial. In general, the alphabets of the Mediterranean region (Anatolia, Greece, Italy) are classified as Phoenician-derived, adapted from around the 8th century BCE, while those of the East (the Levant, Persia, Central Asia and India) are considered Aramaic-derived, adapted from around the 6th century BCE from the Imperial Aramaic script of the Achaemenid Empire.

After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire, the unity of the Imperial Aramaic script was lost, diversifying into a number of descendant cursives.

The Hebrew and Nabataean alphabets, as they stood by the Roman era, were little changed in style from the Imperial Aramaic alphabet.

A Cursive Hebrew variant developed from the early centuries AD, but it remained restricted to the status of a variant used alongside the non-cursive. By contrast, the cursive developed out of the Nabataean alphabet in the same period soon became the standard for writing Arabic, evolving into the Arabic alphabet as it stood by the time of the early spread of Islam.

The development of cursive versions of Aramaic also led to the creation of the Syriac, Palmyrenean and Mandaic alphabets. These scripts formed the basis of the historical scripts of Central Asia, such as the Sogdian and Mongolian alphabets.

It has been suggested that the Old Turkic script in 8th century epigraphy originated in the Aramaic script.

Modern

Today, Biblical Aramaic, Jewish Neo-Aramaic dialects and the Aramaic language of the Talmud are written in the Hebrew alphabet. Syriac and Christian Neo-Aramaic dialects are written in the Syriac alphabet. Mandaic is written in the Mandaic alphabet.

Due to the near-identity of the Aramaic and the classical Hebrew alphabets, Aramaic text is mostly typeset in standard Hebrew script in scholarly literature.

Imperial Aramaic alphabet

Redrawn from A Grammar of Biblical Aramaic, Franz Rosenthal; forms are as used in Egypt, 5th century BC. Names are as in Biblical Aramaic.

| Letter name | Letter form | Letter | Equivalent Letter in ... | Sound value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hebrew | Arabic | Syriac | Brahmi | Nabataean | Kharosthi | ||||

| Ālaph | 𐡀 | א | ء | ܐ | /ʔ/; /aː/, /eː/ | ||||

| Bēth | 𐡁 | ב | ب | ܒ | /b/, /v/ | ||||

| Gāmal | 𐡂 | ג | /ʒ/=ج | ܓ | /ɡ/, /ɣ/ | ||||

| Dālath | 𐡃 | ד | /ð/د,ذ/d/,ض/ḏ/,ظ/ḍ/ | ܕ | /ð/, /d/ | ||||

| Hē | 𐡄 | ה | ﻫ | ܗ | ? | ? | /h/ | ||

| Waw | 𐡅 | ו | و | ܘ | /w/; /oː/, /uː/ | ||||

| Zain | 𐡆 | ז | ز | ܙ | ? | ? | /z/ | ||

| Ḥēth | 𐡇 | ח | /X/ﺧ, /ħ/ﺣ | ܚ | ? | ? | /ħ/ /X/ | ||

| Ṭēth | 𐡈 | ט | ط /ṯ/ | ܛ | emphatic /tˤ/ | ||||

| Yudh | 𐡉 | י | ي | ܝ | /j/; /iː/, /eː/ | ||||

| Kāph | 𐡊 | כ ך | ك | ܟܟ | /k/, /x/ | ||||

| Lāmadh | 𐡋 | ל | ﻟـ | ܠ | /l/ | ||||

| Mim | 𐡌 | מ ם | ﻣ | ܡܡ | /m/ | ||||

| Nun | 𐡍 | נ ן | ن | ܢܢ ܢ | /n/ | ||||

| Semkath | 𐡎 | ס | ﺳ | ܣ | /s/ | ||||

| ʿĒ | 𐡏 | ע | ﻏ/,/ﻋ/ʁ/ | ܥ | ? | ? | /ʕ/ | ||

| Pē | 𐡐 | פ ף | /f/ف | ܦ | /p/ب, /f/ | ||||

| Ṣādhē | 𐡑 | צ ץ | ص | ܨ | emphatic /sˤ/ | ||||

| Qoph | 𐡒 | ק | ق | ܩ | /q/ | ||||

| Rēsh | 𐡓 | ר | ر | ܪ | /r/ | ||||

| Shin | 𐡔 | ש | ﺷ | ܫ | /ʃ/ | ||||

| Tau | 𐡕 | ת | /t/ﺗـ,/θ/ﺛـ | ܬ | /t/, /θ/ | ||||

Matres lectionis

The letters Waw and Yudh, put following the consonants that were followed by the vowels u and i (and often also o and e), are used to indicate the long vowels û and î respectively (often also ô and ê respectively). These letters, which stand for both consonant and vowel sounds, are known as matres lectionis. The letter Alaph, likewise, had some of the characteristics of a mater lectionis: in initial positions, it indicated a specific consonant called glottal stop (followed by a vowel), and, in the middle of the word and word finally, it often also stood for the long vowels â or ê. Among Jews, influence of Hebrew spelling often led to the use of He instead of Alaph in word final positions. The practice of using certain letters to hold vowel values spread to child writing systems of Aramaic, such as Hebrew and Arabic, where they are still used today.

Unicode

The Aramaic alphabet was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 2009 with the release of version 5.2.

The Unicode block for Imperial Aramaic is U+10840–U+1085F:

| Imperial Aramaic[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1084x | 𐡀 | 𐡁 | 𐡂 | 𐡃 | 𐡄 | 𐡅 | 𐡆 | 𐡇 | 𐡈 | 𐡉 | 𐡊 | 𐡋 | 𐡌 | 𐡍 | 𐡎 | 𐡏 |

| U+1085x | 𐡐 | 𐡑 | 𐡒 | 𐡓 | 𐡔 | 𐡕 | 𐡗 | 𐡘 | 𐡙 | 𐡚 | 𐡛 | 𐡜 | 𐡝 | 𐡞 | 𐡟 | |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

References

- ^ Shaked, Saul (1987). "Aramaic". Encyclopedia Iranica. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 250–261. p. 251

- ^ Geiger, Wilhelm; Kuhn, Ernst (2002). "Grundriss der iranischen Philologie: Band I. Abteilung 1". Boston: Adamant: 249ff.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Naveh, Joseph; Shaked, Shaul (2006). Ancient Aramaic Documents from Bactria. Studies in the Khalili Collection. Oxford: Khalili Collections. ISBN 1-874780-74-9.

- Byrne, Ryan. “Middle Aramaic Scripts.” Encyclopaedia of Language and Linguistics. Elsevier. (2006)

- Daniels, Peter T., et al. eds. The World's Writing Systems. Oxford. (1996)

- Coulmas, Florian. The Writing Systems of the World. Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Oxford. (1989)

- Rudder, Joshua. Learn to Write Aramaic: A Step-by-Step Approach to the Historical & Modern Scripts. n.p.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2011. 220 pp. ISBN 978-1461021421 Includes a wide variety of Aramaic scripts.

- Ancient Hebrew and Aramaic on Coins, reading and transliterating Proto-Hebrew, online edition. (Judaea Coin Archive)