Classical liberalism

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Classical liberalism is a political ideology and a branch of liberalism which advocates civil liberties and political freedom with representative democracy under the rule of law and emphasizes economic freedom.[1][2]

Classical liberalism developed in the 19th century in Europe and the United States. Although classical liberalism built on ideas that had already developed by the end of the 18th century, it advocated a specific kind of society, government and public policy as a response to the Industrial Revolution and urbanization.[3] Notable individuals whose ideas have contributed to classical liberalism include John Locke,[4] Jean-Baptiste Say, Thomas Malthus, and David Ricardo. It drew on the economics of Adam Smith and on a belief in natural law,[5] utilitarianism,[6] and progress.[7]

Meaning of the term

The term classical liberalism was applied in retrospect to distinguish earlier 19th-century liberalism from the newer social liberalism.[8] The phrase classical liberalism is also sometimes used to refer to all forms of liberalism before the 20th century, and some conservatives and libertarians use the term classical liberalism to describe their belief in the primacy of individual freedom and minimal government. It is not always clear which meaning is intended.[9][10][11]

Evolution of core beliefs

Core beliefs of classical liberals included new ideas—which departed from both the older conservative idea of society as a family and from later sociological concept of society as complex set of social networks—that individuals were "egoistic, coldly calculating, essentially inert and atomistic"[12] and that society was no more than the sum of its individual members.[13]

Classical liberals agreed with Thomas Hobbes that government had been created by individuals to protect themselves from one another, and that the purpose of government should be to minimize conflict between individuals that would otherwise arise in a state of nature.

These beliefs were complemented by a belief that labourers could be best motivated by financial incentive. [citation needed] This led classical liberal politicians at the time to pass the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, which limited the provision of social assistance, because classical liberals believed in markets as the mechanism that would most efficiently lead to wealth. Adopting Thomas Malthus's population theory, they saw poor urban conditions as inevitable; they believed population growth would outstrip food production, and they regarded that consequence desirable, because starvation would help limit population growth. They opposed any income or wealth redistribution, which they believed would be dissipated by the lowest orders.[14]

Drawing on selected ideas of Adam Smith, classical liberals believed that it is in the common interest that all individuals must be able to secure their own economic self-interest, without government direction.[15] They were critical of the welfare state[16] as interfering in a free market. They criticised labour's group rights being pursued at the expense of individual rights,[17] while they accepted big corporations' rights being pursued at the expense of inequality of bargaining power noted by Adam Smith:[18]

A landlord, a farmer, a master manufacturer, a merchant, though they did not employ a single workman, could generally live a year or two upon the stocks which they have already acquired. Many workmen could not subsist a week, few could subsist a month, and scarce any a year without employment. In the long run the workman may be as necessary to his master as his master is to him; but the necessity is not so immediate.

Classical liberals believed that individuals should be free to obtain work from the highest-paying employers, while the profit motive would ensure that products that people desired were produced at prices they would pay. In a free market, both labour and capital would receive the greatest possible reward, while production would be organised efficiently to meet consumer demand.[19]

An important caveat, as exemplified by the law of equal liberty and the Lockean proviso is that all must be able to pursue liberty equally, without infringing on the equal rights of others.

It was not until emergence of social liberalism that child labour was forbidden, minimum standards of worker safety were introduced, a minimum wage and old age pensions were established, and financial institutions were regulated with the goal of fighting cyclic depressions, monopolies, and cartels. Classical liberals opposed these new laws, which they viewed as an unjust interference of the state.[20] They argued for what they called a "slim state", limited to the following functions:

- protection against foreign invaders, extended to include protection of overseas markets through armed intervention,

- protection of citizens from wrongs committed against them by other citizens, which included protection of private property, enforcement of contracts, and suppression of trade unions. The Chartist movement was an example of this,

- building and maintaining public institutions, and

- "public works" that included a stable currency, standard weights and measures, and support of roads, canals, harbours, railways, and postal and other communications services.[21]

They assert that rights are of a negative nature which require other individuals (and governments) to refrain from interfering with the free market, whereas social liberals asserts that individuals have positive rights, such as the right to vote, the right to an education, the right to health care, and the right to a living wage. For society to guarantee positive rights requires taxation over and above the minimum needed to enforce negative rights.[22][23]

Core beliefs of classical liberals did not necessarily include democracy where law is made by majority vote by citizens, because "there is nothing in the bare idea of majority rule to show that majorities will always respect the rights of property or maintain rule of law."[24] For example, James Madison argued for a constitutional republic with protections for individual liberty over a pure democracy, reasoning that, in a pure democracy, a "common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole...and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party...."[25]

In the late 19th century, classical liberalism developed into neo-classical liberalism, which argued for government to be as small as possible to allow the exercise of individual freedom. In its most extreme form, neo-classical liberalism advocated Social Darwinism.[26] Right-libertarianism is a modern form of neo-classical liberalism.[26]

Hayek's typology of beliefs

Friedrich Hayek identified two different traditions within classical liberalism: the "British tradition" and the "French tradition". Hayek saw the British philosophers Bernard Mandeville, David Hume, Adam Smith, Adam Ferguson, Josiah Tucker and William Paley as representative of a tradition that articulated beliefs in empiricism, the common law, and in traditions and institutions which had spontaneously evolved but were imperfectly understood. The French tradition included Rousseau, Condorcet, the Encyclopedists and the Physiocrats. This tradition believed in rationalism and sometimes showed hostility to tradition and religion. Hayek conceded that the national labels did not exactly correspond to those belonging to each tradition: Hayek saw the Frenchmen Montesquieu, Constant and Tocqueville as belonging to the "British tradition" and the British Thomas Hobbes, Priestley, Richard Price and Thomas Paine as belonging to the "French tradition".[27] Hayek also rejected the label laissez faire as originating from the French tradition and alien to the beliefs of Hume and Smith.

History

Classical liberalism in Britain developed from Whiggery and radicalism, and was also heavily influenced by French physiocracy, and represented a new political ideology. Whiggery had become a dominant ideology following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and was associated with the defence of Parliament, upholding the rule of law and defending landed property. The origins of rights were seen as being in an ancient constitution, which had existed from time immemorial. These rights, which some Whigs considered to include freedom of the press and freedom of speech, were justified by custom rather than by natural rights. They believed that the power of the executive had to be constrained. While they supported limited suffrage, they saw voting as a privilege, rather than as a right. However, there was no consistency in Whig ideology, and diverse writers including John Locke, David Hume, Adam Smith and Edmund Burke were all influential among Whigs, although none of them was universally accepted.[28]

British radicals, from the 1790s to the 1820s, concentrated on parliamentary and electoral reform, emphasising natural rights and popular sovereignty. Richard Price and Joseph Priestley adapted the language of Locke to the ideology of radicalism.[28] The radicals saw parliamentary reform as a first step toward dealing with their many grievances, including the treatment of Protestant Dissenters, the slave trade, high prices and high taxes.[29]

There was greater unity to classical liberalism ideology than there had been with Whiggery. Classical liberals were committed to individualism, liberty and equal rights. They believed that required a free economy with minimal government interference. Writers such as John Bright and Richard Cobden opposed both aristocratic privilege and property, which they saw as an impediment to the development of a class of yeoman farmers. Some elements of Whiggery opposed this new thinking, and were uncomfortable with the commercial nature of classical liberalism. These elements became associated with conservatism.[30]

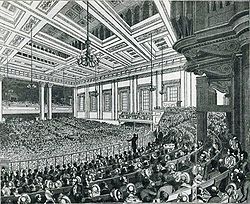

Classical liberalism was the dominant political theory in Britain from the early 19th century until the First World War. Its notable victories were the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, the Reform Act of 1832, and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. The Anti-Corn Law League brought together a coalition of liberal and radical groups in support of free trade under the leadership of Richard Cobden and John Bright, who opposed militarism and public expenditure. Their policies of low public expenditure and low taxation were adopted by William Ewart Gladstone when he became chancellor of the exchequer and later prime minister. Classical liberalism was often associated with religious dissent and nonconformism.[31]

Although classical liberals aspired to a minimum of state activity, they accepted the principle of government intervention in the economy from the early 19th century with passage of the Factory Acts. From around 1840 to 1860, laissez-faire advocates of the Manchester School and writers in The Economist were confident that their early victories would lead to a period of expanding economic and personal liberty and world peace but would face reversals as government intervention and activity continued to expand from the 1850s. Jeremy Bentham and James Mill, although advocates of laissez faire, non-intervention in foreign affairs, and individual liberty, believed that social institutions could be rationally redesigned through the principles of Utilitarianism. The Conservative prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, rejected classical liberalism altogether and advocated Tory Democracy. By the 1870s, Herbert Spencer and other classical liberals concluded that historical development was turning against them.[32] By the First World War, the Liberal Party had largely abandoned classical liberal principles.[33]

The changing economic and social conditions of the 19th century led to a division between neo-classical and social (or welfare) liberals who, while agreeing on the importance of individual liberty, differed on the role of the state. Neo-classical liberals, who called themselves "true liberals", saw Locke's Second Treatise as the best guide, and emphasised "limited government", while social liberals supported government regulation and the welfare state. Herbert Spencer in Britain and William Graham Sumner were the leading neo-classical liberal theorists of the 19th century.[34] Neo-classical liberalism has continued into the contemporary era, with writers such as John Rawls.[35] The evolution from classical to social/welfare liberalism is reflected in Britain in, for example, the evolution of the thought of John Maynard Keynes.[36]

In the United States, liberalism took a strong root because it had little opposition to its ideals, whereas in Europe liberalism was opposed by many reactionary interests. Thomas Jefferson adopted many of the ideals of liberalism but, in the Declaration of Independence, changed Locke's "life, liberty, and property" to the more socially liberal "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness".[4] As America grew, industry became a larger and larger part of American life; and, during the term of America's first populist president, Andrew Jackson, economic questions came to the forefront. The economic ideas of the Jacksonian era were almost universally the ideas of classical liberalism. Freedom was maximised when the government took a "hands off" attitude toward industrial development and supported the value of the currency by freely exchanging paper money for gold. The ideas of classical liberalism remained essentially unchallenged until a series of depressions, thought to be impossible according to the tenets of classical economics, led to economic hardship from which the voters demanded relief. In the words of William Jennings Bryan, "You shall not crucify the American farmer on a cross of gold." Classical liberalism remained the orthodox belief among American businessmen until the Great Depression.[37] The Great Depression saw a sea change in liberalism, leading to the development of modern liberalism. In the words of Arthur Schlesinger Jr.:

When the growing complexity of industrial conditions required increasing government intervention in order to assure more equal opportunities, the liberal tradition, faithful to the goal rather than to the dogma, altered its view of the state," and "there emerged the conception of a social welfare state, in which the national government had the express obligation to maintain high levels of employment in the economy, to supervise standards of life and labour, to regulate the methods of business competition, and to establish comprehensive patterns of social security.[38]

Some modern scholars of liberalism, however, say that no particularly meaningful distinction between classical and modern liberalism exists. Alan Wolfe summarizes this viewpoint, which:[39]

reject(s) any such distinction and argue(s) instead for the existence of a continuous liberal understanding that includes both Adam Smith and John Maynard Keynes... The idea that liberalism comes in two forms assumes that the most fundamental question facing mankind is how much government intervenes into the economy... When instead we discuss human purpose and the meaning of life, Adam Smith and John Maynard Keynes are on the same side. Both of them possessed an expansive sense of what we are put on this earth to accomplish. Both were on the side of enlightenment. Both were optimists who believed in progress but were dubious about grand schemes that claimed to know all the answers. For Smith, mercantilism was the enemy of human liberty. For Keynes, monopolies were. It makes perfect sense for an eighteenth-century thinker to conclude that humanity would flourish under the market. For a twentieth century thinker committed to the same ideal, government was an essential tool to the same end... [M]odern liberalism is instead the logical and sociological outcome of classical liberalism.

Intellectual sources

John Locke

Central to classical liberal ideology was their interpretation of John Locke's Second Treatise of Government and "A Letter Concerning Toleration", which had been written as a defence of the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Although these writings were considered too radical at the time for Britain's new rulers, they later came to be cited by Whigs, radicals and supporters of the American Revolution.[40] However, much of later liberal thought was absent in Locke's writings or scarcely mentioned, and his writings have been subject to various interpretations. There is little mention, for example, of constitutionalism, the separation of powers, and limited government.[41]

James L. Richardson identified five central themes in Locke's writing: individualism, consent, the concepts of the rule of law and government as trustee, the significance of property, and religious toleration. Although Locke did not develop a theory of natural rights, he envisioned individuals in the state of nature as being free and equal. The individual, rather than the community or institutions, was the point of reference. Locke believed that individuals had given consent to government and therefore authority derived from the people rather than from above. This belief would influence later revolutionary movements.[42]

As a trustee, Government was expected to serve the interests of the people, not the rulers, and rulers were expected to follow the laws enacted by legislatures. Locke also held that the main purpose of men uniting into commonwealths and governments was for the preservation of their property. Despite the ambiguity of Locke's definition of property, which limited property to "as much land as a man tills, plants, improves, cultivates, and can use the product of", this principle held great appeal to individuals possessed of great wealth.[43]

Locke held that the individual had the right to follow his own religious beliefs and that the state should not impose a religion against Dissenters. But there were limitations. No tolerance should be shown for atheists, who were seen as amoral, or to Catholics, who were seen as owing allegiance to the Pope over their own national government.[44]

Adam Smith

Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, was to provide most of the ideas of economics, at least until the publication of J. S. Mill's Principles in 1848.[45] Smith addressed the motivation for economic activity, the causes of prices and the distribution of wealth, and the policies the state should follow to maximise wealth.[46]

Smith wrote that as long as supply, demand, prices, and competition were left free of government regulation, the pursuit of material self-interest, rather than altruism, would maximise the wealth of a society[47] through profit-driven production of goods and services. An "invisible hand" directed individuals and firms to work toward the nation's good as an unintended consequence of efforts to maximise their own gain. This provided a moral justification for the accumulation of wealth, which had previously been viewed by some as sinful.[46]

He assumed that workers could be paid wages as low as was necessary for their survival, which was later transformed by Ricardo and Malthus into the "Iron Law of Wages".[48] His main emphasis was on the benefit of free internal and international trade, which he thought could increase wealth through specialisation in production.[49] He also opposed restrictive trade preferences, state grants of monopolies, and employers' organisations and trade unions.[50] Government should be limited to defence, public works and the administration of justice, financed by taxes based on income.[51]

Smith's economics was carried into practice in the nineteenth century with the lowering of tariffs in the 1820s, the repeal of the Poor Relief Act, that had restricted the mobility of labour, in 1834, and the end of the rule of the East India Company over India in 1858.[52]

Say, Malthus, and Ricardo

In addition to Adam Smith's legacy, Say's law, Malthus' theories of population and Ricardo's iron law of wages became central doctrines of classical economics. The pessimistic nature of these theories provided a basis for criticism of capitalism by its opponents and helped perpetuate the tradition of calling economics the "dismal science."[53]

Jean-Baptiste Say was a French economist who introduced Adam Smith's economic theories into France and whose commentaries on Smith were read in both France and Britain.[52] Say challenged Smith's labour theory of value, believing that prices were determined by utility and also emphasised the critical role of the entrepreneur in the economy. However neither of those observations became accepted by British economists at the time. His most important contribution to economic thinking was Say's law, which was interpreted by classical economists that there could be no overproduction in a market, and that there would always be a balance between supply and demand.[54] This general belief influenced government policies until the 1930s. Following this law, since the economic cycle was seen as self-correcting, government did not intervene during periods of economic hardship because it was seen as futile.[55]

Thomas Malthus wrote two books, An essay on the principle of population, published in 1798, and Principles of political economy, published in 1820. The second book which was a rebuttal of Say's law had little influence on contemporary economists.[56] His first book however became a major influence on classical liberalism. In that book, Malthus claimed that population growth would outstrip food production, because population grew geometrically, while food production grew arithmetically. As people were provided with food, they would reproduce until their growth outstripped the food supply. Nature would then provide a check to growth in the forms of vice and misery. No gains in income could prevent this, and any welfare for the poor would be self-defeating. The poor were in fact responsible for their own problems which could have been avoided through self-restraint.[57]

David Ricardo, who was an admirer of Adam Smith, covered many of the same topics but while Smith drew conclusions from broadly empirical observations, Ricardo used deduction, drawing conclusions by reasoning from basic assumptions.[58] While Ricardo accepted Smith's labour theory of value, as the general rule of prices under a free market, he acknowledged that utility influences the price of scarce items. According to his Law of rent, the rent of land was determined by the surplus production obtainable compared to the best free marginal land, or, if none were available, to the subsistence required by the tenants. Wages were thus set by the best available rent-free land.[59] This contradicted Malthus's Iron Law of Wages, in which wages could never rise beyond subsistence levels, and sparked a lengthy debate between the two men. Ricardo explained profits as a return on capital, which itself was the product of labour. However, it was a source of controversy as to whether interest should exist at all in a free market. Ricardian socialists argued that it would not. By contrast, Henry George's complementary law of interest showed, through deduction, that interest and wages rise and fall together, and that they can be substituted.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism provided the political justification for implementation of economic liberalism by British governments, which was to dominate economic policy from the 1830s. Although utilitarianism prompted legislative and administrative reform, and John Stuart Mill's later writings on the subject foreshadowed the welfare state, it was mainly used as a justification for laissez faire.[60]

The central concept of utilitarianism, which was developed by Jeremy Bentham, was that public policy should seek to provide "the greatest happiness of the greatest number". While this could be interpreted as a justification for state action to reduce poverty, it was used by classical liberals to justify inaction with the argument that the net benefit to all individuals would be higher.[53]

Political economy

Classical liberals saw utility as the foundation for public policies. This broke both with conservative "tradition" and Lockean "natural rights", which were seen as irrational. Utility, which emphasises the happiness of individuals, became the central ethical value of all liberalism.[61] Although utilitarianism inspired wide-ranging reforms, it became primarily a justification for laissez-faire economics. However, classical liberals rejected Adam Smith's belief that the "invisible hand" would lead to general benefits and embraced Thomas Robert Malthus' view that population expansion would prevent any general benefit and David Ricardo's view of the inevitability of class conflict. Laissez faire was seen as the only possible economic approach, and any government intervention was seen as useless and harmful. The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 was defended on "scientific or economic principles" while the authors of the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601 were seen as not having had the benefit of reading Malthus.[62]

Commitment to laissez faire, however, was not uniform. Some economists advocated state support of public works and education. Classical liberals were also divided on free trade. Ricardo, for example, expressed doubt that the removal of grain tariffs advocated by Richard Cobden and the Anti-Corn Law League would have any general benefits. Most classical liberals also supported legislation to regulate the number of hours that children were allowed to work and usually did not oppose factory reform legislation.[62]

Despite the pragmatism of classical economists, their views were expressed in dogmatic terms by such popular writers as Jane Marcet and Harriet Martineau.[62] The strongest defender of laissez faire was The Economist founded by James Wilson in 1843. The Economist criticised Ricardo for his lack of support for free trade and expressed hostility to welfare, believing that the lower orders were responsible for their economic circumstances. The Economist took the position that regulation of factory hours was harmful to workers and also strongly opposed state support for education, health, the provision of water, and granting of patents and copyrights.[63]

The Economist also campaigned against the Corn Laws that protected landlords in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland against competition from less expensive foreign imports of cereal products. A rigid belief in laissez faire guided the government response in 1846–1849 to the Great Famine in Ireland, during which an estimated 1.5 million people died. The minister responsible for economic and financial affairs, Charles Wood, expected that private enterprise and free trade, rather than government intervention, would alleviate the famine.[63] The Corn Laws were finally repealed in 1846 by removal tariffs on grain which kept the price of bread artificially high.[64] However, repeal of the Corn Laws came too late to stop Irish famine, partly because it was done in stages over three years.[65][66]

Free trade and world peace

Several liberals, including Adam Smith and Richard Cobden, argued that the free exchange of goods between nations could lead to world peace. Erik Gartzke states, "Scholars like Montesquieu, Adam Smith, Richard Cobden, Norman Angell, and Richard Rosecrance have long speculated that free markets have the potential to free states from the looming prospect of recurrent warfare."[67] American political scientists John R. Oneal and Bruce M. Russett, well known for their work on the democratic peace theory, state:[68]

The classical liberals advocated policies to increase liberty and prosperity. They sought to empower the commercial class politically and to abolish royal charters, monopolies, and the protectionist policies of mercantilism so as to encourage entrepreneurship and increase productive efficiency. They also expected democracy and laissez-faire economics to diminish the frequency of war.

Adam Smith argued in the Wealth of Nations that, as societies progressed from hunter gatherers to industrial societies, the spoils of war would rise but that the costs of war would rise further, making war difficult and costly for industrialised nations.[69]

... the honours, the fame, the emoluments of war, belong not to [the middle and industrial classes]; the battle-plain is the harvest field of the aristocracy, watered with the blood of the people...Whilst our trade rested upon our foreign dependencies, as was the case in the middle of the last century...force and violence, were necessary to command our customers for our manufacturers...But war, although the greatest of consumers, not only produces nothing in return, but, by abstracting labour from productive employment and interrupting the course of trade, it impedes, in a variety of indirect ways, the creation of wealth; and, should hostilities be continued for a series of years, each successive war-loan will be felt in our commercial and manufacturing districts with an augmented pressure

Trade has ever been the extinguisher of war, the eradicator of prejudice, the diffuser of knowledge.

When goods cannot cross borders, armies will.

By virtue of their mutual interest does nature unite people against violence and war…the spirit of trade cannot coexist with war, and sooner or later this spirit dominates every people. For among all those powers…that belong to a nation, financial power may be the most reliable in forcing nations to pursue the noble cause of peace…and wherever in the world war threatens to break out, they will try to head it off through mediation, just as if they were permanently leagued for this purpose.

Cobden believed that military expenditures worsened the welfare of the state and benefited a small but concentrated elite minority, summing up British imperialism, which he believed was the result of the economic restrictions of mercantilist policies. To Cobden, and many classical liberals, those who advocated peace must also advocate free markets.

The belief that free trade would promote peace was widely shared by English liberals of the 19th and early 20th century, leading the economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), who was a classical liberal in his early life, to say that this was a doctrine on which he was "brought up" and which he held unquestioned until at least the 1920s.[74] A related manifestation of this idea was the argument of Norman Angell (1872–1967), most famously before World War I in The Great Illusion (1909), that the interdependence of the economies of the major powers was now so great that war between them was futile and irrational (and therefore unlikely).

See also

Notes

- ^ Modern Political Philosophy (1999), Richard Hudelson, pp. 37–38

- ^ M. O. Dickerson et al., An Introduction to Government and Politics: A Conceptual Approach (2009) p. 129

- ^ Hamowy, p. xxix

- ^ a b Steven M. Dworetz, The Unvarnished Doctrine: Locke, Liberalism, and the American Revolution (1994)

- ^ Joyce Appleby, Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination (1992) p. 58

- ^ Gerald F. Gaus and Chandran Kukathas, Handbook of Political Theory (2004) p. 422

- ^ Hunt, p. 54

- ^ Richardson, p. 52

- ^ "What Is Classical Liberalism?" is an example of an article that defines "classical liberalism" as all liberalism before the 20th Century.

- ^ "An American Classical Liberalism" is an example of an article that defines "classical liberalism" as small government.

- ^ "Guide to Classical Liberal Scholarship", Introduction defines "classical liberalism" as a belief in peace and freedom.

- ^ Hunt, p. 44.

- ^ Hunt, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Hunt, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Dickerson, M. O. An Introduction to Government and Politics: A Conceptual Approach. Cengage Learning, 2009. p. 132

- ^ Alan Ryan, "Liberalism", in A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy, ed. Robert E. Goodin and Philip Pettit (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1995), 293.

- ^ Evans, M. ed. (2001): Edinburgh Companion to Contemporary Liberalism: Evidence and Experience, London: Routledge, 55 (ISBN 1-57958-339-3)

- ^ Smith, A. (1776): Wealth of Nations, Book I, ch. 8

- ^ Hunt, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, Routledge, 2010, ISBN 978-0-415-56789-3

- ^ Hunt, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Kelly, D. (1998): A Life of One's Own: Individual Rights and the Welfare State, Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

- ^ James L. Richardson, Contending Liberalisms in World Politics, pp. 36-38, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001, ISBN 1-55587-915-2

- ^ Ryan, A. (1995): "Liberalism", In: Goodin, R. E. and Pettit, P., eds.: A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 293.

- ^ James Madison, Federalist No. 10 (22 November 1787), in Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison, The Federalist: A Commentary on the Constitution of the United States, ed. Henry Cabot Lodge (New York, 1888), 56.

- ^ a b Mayne, p. 124

- ^ F. A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (London: Routledge, 1976), 55–56.

- ^ a b Vincent, pp. 28–29

- ^ Turner, p. 86

- ^ Vincent, pp. 29–30

- ^ Gray, pp. 26–27

- ^ Gray, p. 28

- ^ Gray, p. 32

- ^ Ishiyama and Breuning, p. 596

- ^ Ishiyama and Breuning, p. 603

- ^ See, e.g., the studies of Keynes by Roy Harrod, Robert Skidelsky, Donald Moggridge and Donald Markwell.

- ^ Eric Voegelin, Mary Algozin, and Keith Algozin, "Liberalism and Its History", Review of Politics 36, no. 4 (1974): 504–20.

- ^ Arthur Schelesinger Jr., "Liberalism in America: A Note for Europeans", in The Politics of Hope (Boston: Riverside Press, 1962).

- ^ Alan Wolfe,"A False Distinction", The New Republic, 2009

- ^ Steven M. Dworetz, The Unvarnished Doctrine: Locke, Liberalism, and the American Revolution (1989)

- ^ Richardson, pp. 22–23

- ^ Richardson, p. 23

- ^ Richardson, pp. 23–24

- ^ Richardson, p. 24

- ^ Mills, pp. 63, 68

- ^ a b Mills, p. 64

- ^ The Wealth of Nations, Strahan and Cadell, 1778

- ^ Mills, p. 65

- ^ Mills, p. 66

- ^ Mills, p. 67

- ^ Mills, p. 68

- ^ a b Mills, p. 69

- ^ a b Mills, p. 76

- ^ Mills, p. 70

- ^ Mills, p. 71

- ^ Mills, pp. 71–72

- ^ Mills, p. 72

- ^ Mills, pp. 73–74

- ^ http://www.econlib.org/library/Ricardo/ricP1a.html#2.3 "On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation – David Ricardo, Chapter 2"

- ^ Richardson, p. 32

- ^ Richardson, p. 31

- ^ a b c Richardson, p. 33

- ^ a b Richardson, p. 34

- ^ George Miller. On Fairness and Efficiency. The Policy Press, 2000. ISBN 978-1-86134-221-8 p.344

- ^ Christine Kinealy. A Death-Dealing Famine:The Great Hunger in Ireland. Pluto Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-7453-1074-9. p. 59

- ^ Stephen J. Lee. Aspects of British Political History, 1815–1914. Routledge, 1994. ISBN 978-0-415-09006-3. p. 83

- ^ Erik Gartzke, "Economic Freedom and Peace," in Economic Freedom of the World: 2005 Annual Report (Vancouver: Fraser Institute, 2005).

- ^ Oneal, J. R.; Russet, B. M. (1997). "The Classical Liberals Were Right: Democracy, Interdependence, and Conflict, 1950-1985". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (2): 267–294. doi:10.1111/1468-2478.00042.

- ^ Michael Doyle, Ways of War and Peace: Realism, Liberalism, and Socialism (New York: Norton, 1997), 237 (ISBN 0-393-96947-9).

- ^ Edward P. Stringham, "Commerce, Markets, and Peace: Richard Cobden's Enduring Lessons", Independent Review 9, no. 1 (2004): 105, 110, 115.

- ^ Henry George, Protection or Free Trade chapter 6. http://www.econlib.org/library/YPDBooks/George/grgPFT6.html

- ^ Daniel T. Griswold, "Peace on Earth, Free Trade for Men", Cato Institute, December 31, 1998.

- ^ Immanuel Kant, The Perpetual Peace.

- ^ Donald Markwell, John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace, Oxford University Press, 2006, chapter 1. http://global.oup.com/academic/product/john-maynard-keynes-and-international-relations-9780198292364;jsessionid=4B0FEAE67C6CC2944F0147AFD5045F62?cc=au&lang=en&

References

- Gray, John. Liberalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995 ISBN 0-8166-2800-9

- Alan Bullock & Maurice Shock (editors). The Liberal Tradition: From Fox to Keynes, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967.

- Epstein, Richard A. (2014). The Classical Liberal Constitution: The Uncertain Quest for Limited Government. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674724891.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hamowy, Ronald, ed. (2008). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Cato Institute. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024 https://books.google.com/books?id=yxNgXs3TkJYC.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Henry, Katherine. Liberalism and the Culture of Security: The Nineteenth-Century Rhetoric of Reform University of Alabama Press, 2011. Draws on literary and other writings to study the debates over liberty and tyranny.

- Hunt, E. K. Property and Prophets: the Evolution of Economic Institutions and Ideologies. New York: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 2003 ISBN 0-7656-0608-9

- Ishiyama, John T. and Breuning, Marijke. 21st Century Political Science: A Reference Handbook, Volume 1. London, UK: SAGE, 2010 ISBN 1-4129-6901-8

- Markwell, Donald. John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace. Oxford UK: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780198292364

- Mayne, Alan James. From politics past to politics future: an integrated analysis of current and emergent paradigms. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999 ISBN 0-275-96151-6

- Mills, John. A critical history of economics. Basingstoke, Hampshire UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002 ISBN 0-333-97130-2

- Richardson, James L. Contending Liberalisms in World Politics: Ideology and Power. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001 ISBN 1-55587-939-X

- Turner, Michael J. British Politics in an Age of Reform. Manchester UK: Manchester University Press, 1999 ISBN 0-7190-5186-X, 9780719051869

- Vincent, Andrew. Modern Political Ideologies (Third Edition). Chichester, W. Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009 ISBN 1-4051-5495-0, ISBN 978-1-4051-5495-6