Gospel of John

| Part of a series of articles on |

| John in the Bible |

|---|

|

| Johannine literature |

| Authorship |

| Related literature |

| See also |

| Part of a series on |

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

The Gospel According to John (Greek: Τὸ κατὰ Ἰωάννην εὐαγγέλιον, romanized: To kata Iōánnēn euangélion; also called the Gospel of John, the Fourth Gospel, or simply John) is one of the four canonical gospels in the New Testament. It traditionally appears fourth, after the synoptic gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. John begins with the witness and affirmation of John the Baptist and concludes with the death, burial, resurrection, and post-resurrection appearances of Jesus.

Although the Gospel of John is anonymous,[1] Christian tradition historically has attributed it to John the Apostle, son of Zebedee and one of Jesus' Twelve Apostles. The gospel is so closely related in style and content to the three surviving Johannine epistles that commentators treat the four books,[2] along with the Book of Revelation, as a single corpus of Johannine literature, albeit not necessarily written by the same author.[Notes 1]

C. K. Barrett,[3][Notes 2] and later Raymond E. Brown,[5] suggested that a tradition developed around the "Johannine Community", and that this tradition gave rise to the gospel.[6] The discovery of a large number of papyrus fragments of manuscripts with Johannine themes has led more scholars to recognize that the texts were among the most influential in the early Church.[7]

The discourses contained with this gospel seem to be concerned with issues of the church–synagogue debate at the time of composition.[8] It is notable that in John, the community appears to define itself primarily in contrast to Judaism, rather than as part of a wider Christian community.[Notes 3] Though Christianity started as a movement within Judaism, it gradually separated from Judaism because of mutual opposition between the two religions.[9]

Structure and content

The Gospel of John can be divided into four sections: a prologue (1:1–18), a Book of Signs (1:19–12:50), a Book of Glory (13:1–20:31), and an epilogue (21).[10] The structure is highly schematic: there are seven "signs" culminating in the raising of Lazarus (foreshadowing the resurrection of Jesus), and seven "I am" sayings and discourses, culminating in Thomas's proclamation of Jesus as "my lord and my God"—the same title (dominus et deus) claimed by Roman Emperor Domitian.[11]

Prologue

Jesus is placed in his cosmic setting as the eternal Logos made flesh who reveals God and gives salvation to believers; John the Baptist, Andrew, and Nathanael bear witness to him as the Lamb of God, the Son of God, and the Christ.[12]

Book of Signs

The narrative of Jesus' public ministry, beginning with the introduction of the first disciples of Jesus. It consists of seven miracles, or "signs", interspersed with long dialogues, discourses, "Amen, amen" sayings, and "I Am" sayings, culminating with the raising of Lazarus from the dead. In John it is this, and not the cleansing of the Temple, that prompts the authorities to have Jesus executed. The seven signs consist of Jesus' miracle at the wedding at Cana, his healing the royal official's son, his healing the paralytic at Bethesda, his feeding the 5,000, his walking on water, his healing the man born blind, and his raising Lazarus from the dead. Other incidents recounted in this segment of the gospel include the cleansing of the Temple; Jesus' conversation with the Pharisee Nicodemus, wherein he explains the importance of spiritual rebirth; his conversation with the Samaritan woman at the well, wherein he gives the Water of Life Discourse; the Bread of Life Discourse, which prompted many of his disciples to leave; the Woman Taken in Adultery; Jesus' claims to be the Light of the World; Jesus' answer to Pilate; the Good Shepherd pericope; Jesus' rejection by the Jews; the Jesus wept; the plot to kill Jesus; the anointing of Jesus; Jesus' triumphal entry into Jerusalem; the prediction of the glorification of the Son of Man; and the prediction of the Last Judgment.

Book of Glory

The narrative of Jesus' Passion, Resurrection, and post-Resurrection appearances. The Passion narrative opens with an account of the Last Supper that differs significantly from that found in the synoptics, with Jesus washing the disciples' feet instead of ushering in a new covenant of his body and blood.[13] This is followed by Jesus' Farewell Discourse, an account of his betrayal, arrest, trial, death, burial, post-Resurrection appearances,[Notes 4] and final commission for his followers. It also includes Peter's denial, the institution of the New Commandment and the New Covenant, the promise of the Paraclete, the allegory of the True Vine, the High Priestly Prayer, the ut omnes unum sint, the What is truth?, Jesus' mocking and crowning with thorns, the Ecce homo, the discovery of the empty tomb, the noli me tangere, the Great Commission, and the incredulity of Thomas. The section ends with a conclusion on the purpose of the gospel: "that [the reader] may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name."[12]

Epilogue

The narrative of Jesus' post-Resurrection appearance to his disciples by the lake, the miraculous catch of fish, the prophecy of the crucifixion of Peter, the restoration of Peter, and the fate of the Beloved Disciple.[12] A large majority of scholars believes this chapter to be an addition to the gospel.[14]

Composition and setting

Authorship, date, and origin

The Gospel of John is anonymous. Traditionally, Christians have identified the author as "the Disciple whom Jesus loved" mentioned in John 21:24,[15] who is understood to be John son of Zebedee, one of Jesus' Twelve Apostles. These identifications, however, are rejected by the majority of modern biblical scholars.[1][16][Notes 5] Nevertheless, the author of the fourth Gospel is sometimes called John the Evangelist, often out of convenience since the true name of the author remains unknown.

A significant minority consider the traditional account of John the Apostle's authorship to be genuine. Scholars have argued that the stylistic unity of John is a significant barrier to theories of multiple stages of editing, with D. A. Carson and Douglas J. Moo arguing that "stylistically it is cut from one cloth".[17] In addition, the ancient external attestation for Johannine authorship is strong and consistent. As Craig Blomberg has noted, "No orthodox writer ever proposes any other alternative for the author of the Fourth Gospel and the book is accepted in all of the early canonical lists, which is all the more significant given the frequent heterodox misinterpretations of it."[18]

John is usually dated to AD 90–110.[19][Notes 6] It arose in a Jewish Christian community in the process of breaking from the Jewish synagogue.[20] Scholars believe that the text went through two to three redactions, or "editions", before reaching its current form.[21][22]

John, which regularly describes Jesus' opponents simply as "the Jews", is more consistently hostile to "the Jews" than any other body of New Testament writing.[23][Notes 7] Historian and former Roman Catholic priest James Carroll states: "The climax of this movement comes in chapter 8 of John, when Jesus is portrayed as denouncing 'the Jews' as the offspring of Satan."[24] In John 8:44 Jesus tells the Jews: "You are of your father the devil, and the desires of your father you will do. He was a murderer from the beginning, and he stood not in the truth; because truth is not in him." In 8:38 and 11:53, "the Jews" are depicted as wishing to kill Jesus. However, Carroll cautions that this and similar statements in the Gospel of Matthew and the First Epistle of Paul to the Thessalonians should be viewed as "evidence not of Jew hatred but of sectarian conflicts among Jews" in the early years of the Christian church.[25]

As noted by New Testament scholar Obrey M. Hendricks, Jr.: "Although its scathing portrayal of the Jews has opened John to charges of anti-Semitism, a careful reading reveals 'the Jews' to be a class designation, not a religious or ethnic grouping; rather than denoting adherents to Judaism in general, the term primarily refers to the hereditary Temple religious authorities."[26] In later centuries, John was used to support anti-Semitic polemics, but the author of the gospel regarded himself as a Jew, championed Jesus and his followers as Jews, and probably wrote for a largely Jewish community.[27][28]

Sources

Rudolf Bultmann, in a seminal work published in 1941, argued that John's sources were a hypothetical "Signs Gospel" listing Christ's miracles, a revelation discourse, and a passion narrative. Bultman's work, combined with that of other scholars (the work of Raymond E. Brown was particularly influential in the English-speaking world), led to a scholarly consensus in the second half of the 20th century that the Gospel of John was independent of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, known as the synoptic gospels. This agreement broke down in the last decade of the century, and there are now many scholars who believe that John did know the synoptics, especially Mark, while the hypothesis of a "signs" source has been increasingly undermined.[29]

But theories of either complete independence of or complete dependence on the synoptics are largely rejected in current scholarship: on the one hand, elements such as distinctive Johannine language, the lengthy discourses, and the prologue on the Logos, are clearly unique to John; on the other, John clearly shares a multitude of episodes with the other three.[30]

The most important sources used by the evangelist were the Jewish scriptures (the Tanakh, more or less identical with the Christian Old Testament), probably in the Greek translation. John quotes from them directly, references important figures from them, and uses narratives from them as the basis for several of the discourses. But the author was also familiar with non-Jewish sources: the Logos of the prologue (the Word that is with God from the beginning of creation) derives from both the Jewish concept of Lady Wisdom and from the Greek philosophers, while John 6 alludes not only to the exodus but also to Greco-Roman mystery cults, while John 4 alludes to Samaritan messianic beliefs.[31]

Historical reliability

Chapters 19 and 21 of John hint that "the Disciple whom Jesus loved", or "the Beloved Disciple", was an eyewitness to Jesus' ministry, but the majority of scholars are cautious of accepting this at face value.[32][33] With the exception of the "Johannine Thunderbolt" passages,[Notes 8] the teachings of Jesus found in the synoptic gospels are very different from those recorded in John, and since the 19th century some scholars have argued that these discourses in Johannine style are less likely to be historical, and more likely to have been written for theological purposes.[35]

Scholars usually agree that John is not entirely without historical value.[36] It has become generally accepted that certain sayings in John are as old or older than their synoptic counterparts. His representation of the topography around Jerusalem is often superior to that of the synoptics, his testimony that Jesus was executed before, rather than on, Passover, might well be more accurate, and his presentation of Jesus in the garden and the prior meeting held by the Jewish authorities are possibly more historically plausible than their synoptic parallels.[36]

Textual history and position in the New Testament

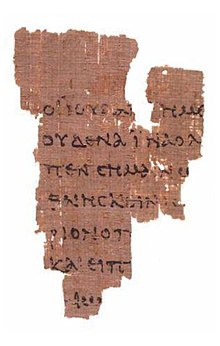

Rylands Library Papyrus P52, a Greek papyrus fragment with John 18:31–33 on one side and 18:37–38 on the other, commonly dated to the first half of the 2nd century, is the oldest New Testament manuscript known.[37] A substantially complete text of John exists from the beginning of the 3rd century at the latest, so that the textual evidence for this gospel is commonly accepted as both earlier and more reliable than that for any other. John stands fourth in the standard ordering of the gospels, after Matthew, Mark and Luke, but in the earliest surviving gospel collection, Papyrus 45 of the 3rd century, they are in the order Matthew, John, Luke and Mark, while in syrcur it is placed third in the order Matthew, Mark, John and Luke.[citation needed]

Theology

Christology

The Gospel of John presents a "high Christology," depicting Jesus as divine, and yet, according to some unorthodox interpretations, subordinate to the one God.[38] However, in his Summa Theologiae, Thomas Aquinas flatly rejects any denial of equality among the persons of the Trinity, including denials based on Johannine passages.[39][Notes 9] John's gospel gives more focus to the relationship of the Son to the Father than the synoptics, as seen in chapter 17 of the gospel. It also focuses on the relation of the Redeemer to believers, the announcement of the Holy Spirit as the Comforter and Advocate (Greek: Παράκλητος, romanized: Parákletos, lit. 'Paraclete'; Template:Lang-la, from the Greek), and the prominence of love as an element in Christian character.[citation needed]

Jesus' divine role

In the synoptics, Jesus speaks often about the Kingdom of God; his own divine role is obscured (see Messianic Secret). In John, Jesus talks openly about his divine role. He echoes the Father's own statement of identity, i.e. "I Am Who I Am", with several "I Am" declarations that also identify him with symbols of major significance.[41] He says "I am":

Logos

In the prologue, John identifies Jesus as the Logos (Word). In Ancient Greek philosophy, the term logos meant the principle of cosmic reason. In this sense, it was similar to the Hebrew concept of Wisdom, God's companion and intimate helper in creation. The Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo merged these two themes when he described the Logos as God's creator of and mediator with the material world. The evangelist adapted Philo's description of the Logos, applying it to Jesus, the incarnation of the Logos.[41]

The opening verse of John is translated as "the Word was with God and the Word was God" in all "orthodox" English Bibles.[Notes 10] There are alternative views. The New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures of Jehovah's Witnesses has "The Word was with God, and the Word was a god." The Scholars Version of the gospel, developed by the Jesus Seminar, loosely translates the phrase as "The Logos was what God was," offered as a better representation of the original meaning of the evangelist.[42]

Sacraments

Among the most controversial areas of interpretation of John is its sacramental theology. Scholars' views have fallen along a wide spectrum ranging from anti-sacramental and non-sacramental, to sacramental, to ultra-sacramental and hyper-sacramental. Scholars disagree both on whether and how frequently John refers to the sacraments at all, and on the degree of importance he places upon them. Individual scholars' answers to one of these questions do not always correspond to their answer to the other.[43]

Frequency of allusion

According to Rudolf Bultmann, there are three sacramental allusions: one to baptism (3:5), one to the Eucharist (6:51–58), and one to both (19:34). He believed these passages to be later interpolations, though most scholars now reject this assessment. Some scholars on the weaker-sacramental side of the spectrum deny that there are any sacramental allusions in these passages or in the gospel as a whole, while others see sacramental symbolism applied to other subjects in these and other passages. Oscar Cullmann and Bruce Vawter, a Protestant and a Catholic respectively, and both on the stronger-sacramental end of the spectrum, have found sacramental allusions in most chapters. Cullmann found references to baptism and the Eucharist throughout the gospel, and Vawter found additional references to matrimony in 2:1–11, anointing of the sick in 12:1–11, and penance in 20:22–23. Towards the center of the spectrum, Raymond Brown is more cautious than Cullmann and Vawter but more lenient than Bultmann and his school, identifying several passages as containing sacramental allusions and rating them according to his assessment of their degree of certainty.[43]

Importance to the evangelist

Most scholars on the stronger-sacramental end of the spectrum assess the sacraments as being of great importance to the evangelist. However, perhaps counterintuitively, some scholars who find fewer sacramental references, such as Udo Schnelle, view the references that they find as highly important as well. Schnelle in particular views John's sacramentalism as a counter to Docetist anti-sacramentalism. On the other hand, though he agrees that there are anti-Docetic passages, James Dunn views the absence of a Eucharistic institution narrative as evidence for an anti-sacramentalism in John, meant to warn against a conception of eternal life as dependent on physical ritual.[43]

Individualism

In comparison to the synoptic gospels, the Fourth Gospel is markedly individualistic, in the sense that it places emphasis more on the individual's relation to Jesus than on the corporate nature of the Church.[43][44] This is largely accomplished through the consistently singular grammatical structure of various aphoristic sayings of Jesus throughout the gospel.[43][Notes 11] According to Baukham, emphasis on believers coming into a new group upon their conversion is conspicuously absent from John.[43] There is also a theme of "personal coinherence", that is, the intimate personal relationship between the believer and Jesus in which the believer "abides" in Jesus and Jesus in the believer.[44][43][Notes 12] According to Moule, the individualistic tendencies of the Fourth Gospel could potentially give rise to a realized eschatology achieved on the level of the individual believer; this realized eschatology is not, however, to replace "orthodox", futurist eschatological expectations, but is to be "only [their] correlative."[45]

John the Baptist

John's account of the Baptist is different from that of the synoptic gospels. In this gospel, John is not called "the Baptist."[46] The Baptist's ministry overlaps with that of Jesus; his baptism of Jesus is not explicitly mentioned, but his witness to Jesus is unambiguous.[46] The evangelist almost certainly knew the story of John's baptism of Jesus and he makes a vital theological use of it.[47] He subordinates the Baptist to Jesus, perhaps in response to members of the Baptist's sect who regarded the Jesus movement as an offshoot of their movement.[13]

In John's gospel, Jesus and his disciples go to Judea early in Jesus' ministry before John the Baptist was imprisoned and executed by Herod. He leads a ministry of baptism larger than John's own. The Jesus Seminar rated this account as black, containing no historically accurate information.[42] According to the biblical historians at the Jesus Seminar, John likely had a larger presence in the public mind than Jesus.[48]

Gnostic elements

Although not commonly understood as Gnostic, many scholars, including Bultmann, have forcefully argued that the Gospel of John has elements in common with Gnosticism.[13] Christian Gnosticism did not fully develop until the mid-2nd century, and so 2nd-century Proto-Orthodox Christians concentrated much effort in examining and refuting it.[49] To say John's gospel contained elements of Gnosticism is to assume that Gnosticism had developed to a level that required the author to respond to it.[50] Bultmann, for example, argued that the opening theme of the Gospel of John, the pre-existing Logos, was actually a Gnostic theme. Other scholars, e.g. Raymond E. Brown have argued that the pre-existing Logos theme arises from the more ancient Jewish writings in the eighth chapter of the Book of Proverbs, and was fully developed as a theme in Hellenistic Judaism by Philo Judaeus.[citation needed]

Comparisons to Gnosticism are based not in what the author says, but in the language he uses to say it, notably, use of the concepts of Logos and Light.[51] Other scholars, e.g. Raymond E. Brown, have argued that the ancient Jewish Qumran community also used the concept of Light versus Darkness. The arguments of Bultmann and his school were seriously compromised by the mid-20th-century discoveries of the Nag Hammadi library of genuine Gnostic writings (which are dissimilar to the Gospel of John) as well as the Qumran library of Jewish writings (which are often similar to the Gospel of John).[52]

Gnostics read John but interpreted it differently from the way non-Gnostics did.[53] Gnosticism taught that salvation came from gnosis, secret knowledge, and Gnostics did not see Jesus as a savior but a revealer of knowledge.[54] Barnabas Lindars asserts that the gospel teaches that salvation can only be achieved through revealed wisdom, specifically belief in (literally belief into) Jesus.[55]

Raymond Brown contends that "The Johannine picture of a savior who came from an alien world above, who said that neither he nor those who accepted him were of this world,[56] and who promised to return to take them to a heavenly dwelling[57] could be fitted into the gnostic world picture (even if God's love for the world in 3:16 could not)."[58] It has been suggested that similarities between John's gospel and Gnosticism may spring from common roots in Jewish Apocalyptic literature.[59]

Comparison with the synoptics

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2016) |

The Gospel of John is significantly different from the synoptic gospels, with major variations in material, theological emphasis, chronology, and literary style.[60] There are also some discrepancies between John and the synoptics, some amounting to contradictions.[60]

Material

John lacks scenes from the synoptics such as Jesus' baptism,[61] the calling of the Twelve, exorcisms, parables, the Transfiguration, and the Last Supper. Conversely, it includes scenes not found in the synoptics, including Jesus turning water into wine at the wedding at Cana, the resurrection of Lazarus, Jesus washing the feet of his disciples, and multiple visits to Jerusalem.[60] The Fourth Gospel contains no account of the Nativity of Jesus, unlike Matthew and Luke, and his mother Mary, while frequently mentioned, is never identified by name.[62][63] John does assert that Jesus was known as the "son of Joseph" in 6:42. In contrast to Matthew and Luke, and in agreement with Mark, in John Jesus comes from Nazareth rather than the messianic town of Bethlehem. For John, Jesus' town of origin is irrelevant, for he comes from beyond this world, from God the Father.[64] While John makes no direct mention of Jesus' baptism,[61][60] he does quote John the Baptist's description of the descent of the Holy Spirit as a dove, as happens at Jesus' baptism in the synoptics. Major synoptic speeches of Jesus are absent, including the Sermon on the Mount and the Olivet Discourse,[65] and the exorcisms of demons are never mentioned as in the synoptics.[61][66] During the Last Supper narrative, Jesus washes the disciples' feet instead of celebrating the first Eucharist as in the synoptics. No other women are mentioned going to the tomb with Mary Magdalene, whereas in the synoptics she is accompanied by Mary of Clopas, Mary, mother of James, "the other Mary", and/or Salome.[citation needed] John never lists all of the Twelve Disciples and names at least one disciple, Nathanael, whose name is not found in the synoptics. Nathanael appears to parallel Bartholomew found in the synoptics, as both are paired with Philip in the respective gospels.[citation needed] While James, son of Zebedee and John are prominent disciples in the synoptics, John mentions them only in the epilogue, where they are referred to not by name but as the "sons of Zebedee."[citation needed] Thomas is given a personality beyond a mere name, described as "Doubting Thomas". [67]

Theological emphasis

Jesus is identified with the Word ("Logos"), and the Word is identified with theos ("god" in Greek);[68] no such identification is made in the synoptics.[69] In Mark, Jesus urges his disciples to keep his divinity secret, but in John he is very open in discussing it, even referring to himself as "I AM", the title God gives himself in Exodus at his self-revelation to Moses. In the synoptics the chief theme is the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Heaven (the latter specifically in Matthew), while John's theme is Jesus as the source of eternal life and the Kingdom is only mentioned twice.[60][66] In contrast to the synoptic expectation of the Kingdom (using the term parousia, meaning "coming"), John presents a more individualistic, realized eschatology.[70][71][Notes 13]

Chronology

In the synoptics the ministry of Jesus takes a single year, but in John it takes three, as evidenced by references to three Passovers. Events are not all in the same order: the date of the crucifixion is different, as is the time of Jesus' anointing in Bethany, and the cleansing of the temple occurs in the beginning of Jesus' ministry rather than near its end.[60]

Literary style

In the synoptics, quotations from Jesus are usually in the form of short, pithy sayings; in John, longer quotations are often given. The vocabulary is also different, and filled with theological import: in John, Jesus does not work "miracles" (Greek: δῠνάμεις, romanized: dynámeis, sing. δύνᾰμῐς, dýnamis), but "signs" (Greek: σημεῖᾰ, romanized: sēmeia, sing. σημεῖον, sēmeion) which unveil his divine identity.[60] Most scholars consider John not to contain any parables.[73] Rather it contains metaphorical stories or allegories, such as those of the Good Shepherd and of the True Vine, in which each individual element corresponds to a specific person, group, or thing. Some scholars, however, find some such parables as the short story of the childbearing woman (16:21) or the dying grain (12:24).[Notes 14]

Discrepancies

According to the synoptics, the arrest of Jesus was a reaction to the cleansing of the temple, while according to John it was triggered by the raising of Lazarus.[60] The Pharisees, portrayed as more uniformly legalistic and opposed to Jesus in the synoptic gospels, are instead portrayed as sharply divided; they debate frequently in John's accounts. Some, such as Nicodemus, even go so far as to be at least partially sympathetic to Jesus. This is believed to be a more accurate historical depiction of the Pharisees, who made debate one of the tenets of their system of belief.[74] John the Baptist publicly proclaims Jesus to be the Lamb of God. The Baptist recognizes Jesus secretly in Matthew, and not at all in Mark or Luke. The Gospel of John also has the Baptist deny that he is Elijah, whereas Mark and Matthew identify him with Elijah. The Cleansing of the Temple appears towards the beginning of Jesus' ministry. In the synoptics this occurs soon before Jesus is crucified.[citation needed]

Representations

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2016) |

The Gospel of John has influenced Impressionist painters, Renaissance art, literature, and other depictions of Jesus, with influences on Greek, Jewish and European history.[citation needed]

It has been depicted in live narrations and dramatized in productions, skits, plays, and Passion Plays, as well as in film. The most recent such portrayal is the 2014 film 'The Gospel of John', directed by David Batty and narrated by David Harewood and Brian Cox, with Selva Rasalingam as Jesus. The 2003 film The Gospel of John, was directed by Philip Saville, narrated by Christopher Plummer, with Henry Ian Cusick as Jesus.

Parts of the gospel have been set to music. One such setting is Steve Warner's power anthem "Come and See", written for the 20th anniversary of the Alliance for Catholic Education and including lyrical fragments taken from the Book of Signs. Additionally, some composers have made settings of the Passion as portrayed in the gospel, most notably the one composed by Johann Sebastian Bach, although some verses are borrowed from Matthew.[75]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Harris 2006, p. 479: "Most scholars believe that the same person wrote all three documents but that he is not to be identified with either the apostle John or the author of the Gospel."

- ^ The use of first person plural in John, specially in the letters, is the base of these theories. Barrett quotes on that sense Robinson, who in 1965 asserted "the gospel is composed in Judea and under the pressure of controversy with "the jews" [sic] of that area. But in its present form it is an appeal to those outside the Church, to win to the faith that Greek speaking Diaspora Judaism to which the author now finds himself belonging".[4]

- ^ Chilton & Neusner 2006, p. 5: "by their own word what they (the writers of the New Testament) set forth in the New Testament must qualify as a Judaism. ... [T]o distinguish between the religious world of the New Testament and an alien Judaism denies the authors of the New Testament books their most fiercely held claim and renders incomprehensible much of what they said."

- ^ The resurrection itself is not detailed in the gospel, though it is entailed from the post-resurrection appearances.

- ^ For the circumstances which led to the formation of the tradition, and the reasons why the majority of modern scholars reject it, see Lindars, Edwards & Court 2000, pp. 41–42. For arguments in support of the tradition, see Craig, Blomberg (2009). Jesus and the Gospels. p. 197–98.

- ^ For the reasons behind this, see Lincoln 2005, p. 18

- ^ For details see Dunn 1992, p. 183 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFDunn1992 (help)

- ^ The term Johannine Thunderbolt refers to the Q source–derived logion in Matthew 11:25–27 and Luke 10:21–22. The phrase was coined by Karl von Hase in an 1823–24 lecture series entitled Geschichte Jesu: "... wie ein Aerolith aus dem johanneischen Himmel gefallen ..." ("... a meteorite fallen from the Johannine sky ...")[34]

- ^ Additionally, Aquinas cites the Athanasian Creed, the first ecumenical creed to explicitly outline the Trinitarian doctrine; the Creed maintains the co-majesty, co-eternality, co-equality of the persons of the Trinity.[40]

- ^ That is, the New International Version, Today's New International Version, the New American Standard Bible, the New American Bible, the New American Bible Revised Edition, the Amplified Bible, the New Living Translation, the Douay–Rheims Bible, the King James Version, Young's Literal Translation, the Darby Translation, and the Wycliffe New Testament, to name a few.

- ^ Bauckham (2015) contrasts John's consistent use of the third person singular ("The one who ..."; "If anyone ..."; "Everyone who ..."; "Whoever ..."; "No one ...") with the alternative third person plural constructions he could have used instead ("Those who ..."; ""All those who ..."; etc.). He also notes that the sole exception occurs in the prologue, serving a narrative purpose, whereas the later aphorisms serve a "paraenetic function".

- ^ See John 6:56, 10:14–15, 10:38, and 14:10, 17, 20, and 23.

- ^ Realized eschatology is a Christian eschatological theory popularized by C. H. Dodd (1884–1973). It holds that the eschatological passages in the New Testament do not refer to future events, but instead to the ministry of Jesus and his lasting legacy.[72] In other words, it holds that Christian eschatological expectations have already been realized or fulfilled.

- ^ See Zimmermann 2015, pp. 333–60.

Footnotes

- ^ a b Burkett 2002, p. 215.

- ^ Lindars 1990, p. 63.

- ^ Barrett 1978, p. 133.

- ^ Barrett 1978, p. 137.

- ^ Brown 1966, p. 43.

- ^ Ehrman 2009.

- ^ De Santos Otero 1993, p. 97.

- ^ Lindars 1990, p. 53.

- ^ Lindars 1990, p. 59.

- ^ Köstenberger, Kellum & Quarles 2009, p. 305.

- ^ Witherington 2004, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Edwards 2015, p. 171.

- ^ a b c Harris 2006.

- ^ Bauckham 2007, p. 271.

- ^ John 21:24

- ^ Lindars, Edwards & Court 2000, p. 41–42.

- ^ Carson & Moo 2009, p. 246.

- ^ Blomberg 2011, p. 25.

- ^ Lincoln 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 215–216.

- ^ Edwards 2015, p. ix.

- ^ Ehrman 2004, p. 164–165.

- ^ Dunn 1992, p. 182–183,195. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFDunn1992 (help)

- ^ Carroll 2001, p. 92.

- ^ Carroll 2001, p. 85.

- ^ Hendricks 2007.

- ^ Senior 1991, p. 155–156.

- ^ Dunn 1992, p. 209. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFDunn1992 (help)

- ^ Lincoln 2005, p. 29–30.

- ^ Porter 2015, p. 69–70.

- ^ Reinhartz 2011, p. 155.

- ^ Witherington 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Kysar 2007, p. 80.

- ^ Denaux 1992, p. 113-47.

- ^ Sanders 1995, p. 57,70–71.

- ^ a b Theissen & Merz 1998, p. 36–37.

- ^ Metzger & Ehrman 1985, p. 55–56.

- ^ Hurtado 2005, p. 53.

- ^ Summa Theologiae, Part I, Question XLII.

- ^ Athanasian Creed at New Advent.

- ^ a b Harris 2006, p. 302–10.

- ^ a b Funk & Jesus Seminar 1998, p. 365–440.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bauckham 2015.

- ^ a b Moule 1962, p. 172.

- ^ Moule 1962, p. 174.

- ^ a b Cross & Livingstone 2005.

- ^ Barrett 1978, p. 16.

- ^ Funk & Jesus Seminar 1998, p. 268.

- ^ Olson 1999, p. 36.

- ^ Kysar 2005, p. 88ff.

- ^ Van den Broek & Vermaseren 1981, p. 467ff.

- ^ Combs 1987.

- ^ Most 2005, p. 121ff.

- ^ Skarsaune 2008, p. 247ff.

- ^ Lindars 1990, p. 62.

- ^ John 17:14

- ^ John 14:2–3

- ^ Brown 1997, p. 375.

- ^ Kovacs 1995.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Burge 2014, p. 236–237.

- ^ a b c Funk, Hoover & Jesus Seminar 1993, p. 1–30.

- ^ Williamson 2004, p. 265.

- ^ Michaels 1971, p. 733.

- ^ Fredriksen 2008.

- ^ Pagels 2003.

- ^ a b Thompson 2006, p. 184.

- ^ Walvoord, John F. (1985). The Bible Knowledge Commentary. Wheaton, IL: Victor Books. p. 313.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Ehrman 2005.

- ^ Carson, D. A. (1991). The Pillar New Testament Commentary: The Gospel According to John. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eardmans Publishing Co. p. 117.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Moule 196, p. 172-74.

- ^ Sander 2015.

- ^ Ladd & Hagner 1993, p. 56.

- ^ Barry 1911.

- ^ Neusner 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Ambrose 2005.

Bibliography

- Ambrose, Z. Philip (2005). "BWV 245". J.S. Bach: The Extant Texts of the Vocal Works in English Translations with Commentary. Vol. 2. Translated by Ambrose, Z. Philip. Xlibris Corp. ISBN 978-1-4134-4600-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barrett, C. K. (1978). The Gospel According to St. John: An Introduction with Commentary and Notes on the Greek Text (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22180-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)  Barry, William (1911). "Parables". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Barry, William (1911). "Parables". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)- Bauckham, Richard (2007). The Testimony of the Beloved Disciple: Narrative, History, and Theology in the Gospel of John. Baker. ISBN 978-0-8010-3485-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bauckham, Richard (2015). Gospel of Glory: Major Themes in Johannine Theology. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4412-2708-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Blomberg, Craig (2011). The Historical Reliability of John's Gospel. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 0-8308-3871-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Raymond E. (1966). The Gospel According to John, Volume 1. Anchor Bible series. Vol. 29. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-01517-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Raymond E. (1997). An Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Anchor Bible. ISBN 0-385-24767-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burge, Gary M. (2014). "Gospel of John". In Evans, Craig A. (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-72224-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00720-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carroll, James (2001). Constantine's Sword: The Church and the Jews: A History. Houghton Mifflin. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-395-77927-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carson, D. A.; Moo, Douglas J. (2009). An Introduction to the New Testament. HarperCollins Christian Publishing. ISBN 978-0-310-53955-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chilton, Bruce; Neusner, Jacob (2006). Judaism in the New Testament: Practices and Beliefs. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-81497-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Combs, William W. (1987). "Nag Hammadi, Gnosticism and New Testament Interpretation". Grace Theological Journal. 8 (2): 195–212.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (2005). "John, Gospel of St.". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Denaux, Adelbert (1992). "The Q-Logion Mt 11,27 / Lk 10,22 and the Gospel of John". In Denaux, Adelbert (ed.). John and the Synoptics. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium. Vol. 101. Leuven University Press. pp. 113–47. ISBN 978-90-6186-498-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dunn, James D. G., ed. (1992). Jews and Christians: The Parting of the Ways—A.D. 70 to 135. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-4498-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)- Alexander, Philip S. (1992). 'The Parting of the Ways' from the Perspective of Rabbinic Judaism. ISBN 978-0-8028-4498-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dunn, James D. G. (1992). The Question of Anti-Semitism in the New Testament Writings of the Period. ISBN 978-0-8028-4498-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Alexander, Philip S. (1992). 'The Parting of the Ways' from the Perspective of Rabbinic Judaism. ISBN 978-0-8028-4498-9.

- Edwards, Ruth B. (2015). Discovering John: Content, Interpretation, Reception. Discovering Biblical Texts. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-7240-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ehrman, Bart D. (2004). The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford. ISBN 0-19-515462-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-073817-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ehrman, Bart D. (2009). Jesus, Interrupted. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-117393-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fredriksen, Paula (2008). From Jesus to Christ: The Origins of the New Testament Images of Jesus. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16410-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Funk, Robert W.; Hoover, Roy W.; Jesus Seminar (1993). The Five Gospels: The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus. Polebridge Press. ISBN 978-0-944344-57-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Funk, Robert W.; Jesus Seminar (1998). The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 978-0-06-062978-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harris, Stephen L. (2006). Understanding the Bible (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-296548-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hendricks, Obrey M., Jr. (2007). "The Gospel According to John". In Coogan, Michael D.; Brettler, Marc Z.; Newsom, Carol A.; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible (3rd ed.). Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59856-032-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hurtado, Larry W. (2005). How on Earth Did Jesus Become a God?: Historical Questions about Earliest Devotion to Jesus. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2861-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Köstenberger, Andreas J.; Kellum, Leonard Scott; Quarles, Charles L. (2009). "The Gospel According to John". The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament. Nashville: B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kovacs, Judith L. (1995). "Now Shall the Ruler of This World Be Driven Out: Jesus' Death as Cosmic Battle in John 12:20–36". Journal of Biblical Literature. 114 (2): 227–247. doi:10.2307/3266937. JSTOR 3266937.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kysar, Robert (2005). Voyages with John: Charting the Fourth Gospel. Baylor University Press. ISBN 978-1-932792-43-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kysar, Robert (2007). "The Dehistoricizing of the Gospel of John". In Anderson, Paul N.; Just, Felix; Thatcher, Tom (eds.). John, Jesus, and History, Volume 1: Critical Appraisals of Critical Views. Society of Biblical Literature Symposium series. Vol. 44. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-293-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ladd, George Eldon; Hagner, Donald Alfred (1993). A Theology of the New Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-0680-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lincoln, Andrew (2005). Gospel According to St John: Black's New Testament Commentaries. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-8822-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lindars, Barnabas (1990). John. New Testament Guides. Vol. 4. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-85075-255-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lindars, Barnabas; Edwards, Ruth; Court, John M. (2000). The Johannine Literature. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84127-081-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Metzger, B. M.; Ehrman, B. D. (1985). The Text of New Testament. Рипол Классик. ISBN 978-5-88500-901-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Michaels, J. Ramsey (1971). "Verification of Jesus' Self-Revelation in His passion and Resurrection (18:1–21:25)". The Gospel of John. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4674-2330-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Most, Glenn W. (2005). Doubting Thomas. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01914-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moule, C. F. D. (July 1962). "The Individualism of the Fourth Gospel". Novum Testamentum,. 5 (2/3): 171–190. doi:10.2307/1560025. JSTOR 1560025.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Neusner, Jacob (2003). Invitation to the Talmud: A Teaching Book. South Florida Studies in the History of Judaism. Vol. 169. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59244-155-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Olson, Roger E. (1999). The Story of Christian Theology: Twenty Centuries of Tradition & Reform. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1505-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - De Santos Otero, Aurelio (1993). Los Evangelios Apocrifos [The Apochryphal Gospels]. Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos (in Spanish). Vol. 148 (9th ed.). Madrid. ISBN 978-84-7914-044-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pagels, Elaine H. (2003). Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-50156-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Porter, Stanley E. (2015). John, His Gospel, and Jesus: In Pursuit of the Johannine Voice. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-7170-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Van den Broek, Raymond; Vermaseren, Maarten Jozef (1981). Studies in Gnosticism and Hellenistic Religions. Études préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l'Empire romain. Vol. 91. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-06376-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reinhartz, Adele (2011). "John". In Levine, Amy-Jill; Brettler, Marc Z. (eds.). The Jewish Annotated New Testament. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-992706-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sanders, E. P. (1995). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-192822-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Senior, Donald (1991). The Passion of Jesus in the Gospel of John. Passion of Jesus Series. Vol. 4. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5462-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Skarsaune, Oskar (2008). In the Shadow of the Temple: Jewish Influences on Early Christianity. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-2670-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1998) [1996]. The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-0863-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, Marianne Maye (2006). "The Gospel According to John". In Barton, Stephen C. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Gospels. Cambridge Companions to Religion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80766-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Williamson, Lamar, Jr. (2004). Preaching the Gospel of John: Proclaiming the Living Word. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22533-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Witherington, Ben (2004). The New Testament Story. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2765-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zimmermann, Ruben (2015). Puzzling the Parables of Jesus: Methods and Interpretation. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-6532-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Brown, Raymond E. (1965). "Does the New Testament call Jesus God?". Theological Studies. 26: 545–73.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Raymond E. (1979). The Community of the Beloved Disciple. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-2174-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carson, D.A. (1991). The Gospel According to John. Pillar New Testament Commentary Series. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3683-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Culpepper, R. Alan (1983). Anatomy of the Fourth Gospel: A Study in Literary Design. Minneapolis: Fortress. ISBN 978-0-8006-2068-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dodd, C.H. (1 May 1968). The Interpretation of the Fourth Gospel. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09517-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Estes, Douglas (2008). The Temporal Mechanics of the Fourth Gospel: A Theory of Hermeneutical Relativity in the Gospel of John (BIS 92). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16598-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hamid-Khani, Saeed (2000). Revelation and Concealment of Christ: A Theological Inquiry into the Elusive Language of the Fourth Gospel (WUNT 120). Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-147138-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hill, Charles E. (2006). The Johannine Corpus in the Early Church. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929144-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jensen, Robin M. (October 2002). The Two Faces of Jesus. p. 42.

{{cite book}}:|magazine=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - M'Cheyne, Robert Murray (30 April 2007). Bethany: Discovering Christ's Love in Times of Suffering When Heaven Seems Silent (A Study of John 12). Diggory Press. ISBN 978-1-84685-702-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morris, Leon (1995). The Gospel According to St. John. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-8028-2504-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Robinson, John A.T. (1990). Redating the New Testament. Trinity Press International. ISBN 978-0-334-02300-5. OL 9427964M.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sander, Emilie T. (2015). "Biblical Literature: The Fourth Gospel: The Gospel According to John". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sloyan, Gerard Stephen (2006). What are They Saying about John?. What Are They Saying about ... ? series (Revised ed.). Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4337-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, D. Moody (2010). "Jesus Tradition in the Gospel of John". In Holmén, Tom; Porter, Stanley E. (eds.). Handbook for the Study of the Historical Jesus. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-16372-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thatcher, Tom, ed. (2007). What We Have Heard from the Beginning: The Past, Present and Future of Johannine Studies. Waco: Baylor University Press. ISBN 978-1-60258-010-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thatcher, Tom (2009). "Aspects of Historicity in the Fourth Gospel: Phase Two of the John, Jesus, and History Project". In Anderson, Paul N.; Just, Felix; Thatcher, Tom (eds.). John, Jesus, and History, Volume 2: Aspects of Historicity in the Fourth Gospel. Society of Biblical Literature Symposium series. Vol. 44. Society of Biblical Literature. ASIN 1589833929.

{{cite book}}: Check|asin=value (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Theissen, Gerd (2011). The New Testament: A Literary History. Translated by Maloney, Linda M. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-9785-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, Marianne Meye (1996). "The Historical Jesus and the Johannine Christ". In Smith, Dwight Moody; Culpepper, R. Alan; Black, Carl Clifton (eds.). Exploring the Gospel of John: In Honor of D. Moody Smith. Old Testament Library. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22083-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, Marianne Meye (2011). "John". In Fee, Gordon D.; Hubbard, Robert L., Jr. (eds.). The Eerdmans Companion to the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3823-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Vermes, Geza (2004). The Authentic Gospel of Jesus. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-191260-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wansbrough, Henry (2015). Introducing the New Testament. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-567-65670-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - White, L. Michael (2010). Scripting Jesus: The Gospels in Rewrite. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-198537-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)  This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Fonck, Leopold (1910). "Gospel of St. John". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Fonck, Leopold (1910). "Gospel of St. John". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Further reading

- A Brief Introduction to the Gospel According to John

- Gospel According to John, Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- A textual commentary on the Gospel of John Detailed text; critical discussion of the 300 most important variants of the Greek text (PDF, 376 pages; archived on 4 March 2016)

- John Rylands papyrus: text, translation, illustration and a bibliography of the discussion

- John, Gospel of St. in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica – collected comments; archived 4 April 2006

- Conflicts Between the Gospel of John & the Remaining Three (synoptic) Gospels on ReligiousTolerance.com.

- John Henry Bernard, Alan Hugh McNeile, A critical and exegetical commentary on the Gospel according to St. John, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2000.

External links

Online translations of the Gospel of John: