History of submarines

This article aims to cover some facts about the history of Submarines, ships or boats operating underwater.

Early history of submarines and the first submersibles

The concept of a underwater boat of course has roots deep in antiquity. The very first report of someone attempting to put the idea into practice seems to have been an attempt by Alexander the Great who, according to Aristotle had developed a primitive submersible for reconaissance missions by 332BC. A similar device had been developed in China by 200 BC. However, in the modern era, the first person to propose a submarine was the Englishman William Bourne who designed a prototype submarine in 1578. Unfortunately for him these ideas never got beyond the planning stage. By the 17th century the Ukrainian Cossacks were using a riverboat called the chaika (gull) that was used underwater for reconnaissance and infiltration missions. This seems to have been closer to (and may have been developed from) Aristotle's description of the submersible used by Alexander the Great. The Chaika could be easily capsized and submerged so that the crew was able to breathe underneath (like in a modern diving bell) and propel the vessel by walking on the bottom of river. Special plummets (for submerging) and pipes for additional breathing were used.

However, the first submersible proper to be actually built in modern times was built in 1620 by Cornelius Jacobszoon Drebbel, a Dutchman in the service of James I: it was based on Bourne's design. It was propelled by means of oars. The precise nature of the submarine type is a matter of some controversy; some claim that it was merely a bell towed by a boat. Two improved types were tested in the Thames between 1620 and 1624.

Though the first submersible vehicles were tools for exploring under water, it did not take long for inventors to recognize their military potential. The strategic advantages of submarines were set out by Bishop John Wilkins of Chester in Mathematicall Magick in 1648.

- Tis private: a man may thus go to any coast in the world invisibly, without discovery or prevented in his journey.

- Tis safe, from the uncertainty of Tides, and the violence of Tempests, which do never move the sea above five or six paces deep. From Pirates and Robbers which do so infest other voyages; from ice and great frost, which do so much endanger the passages towards the Poles.

- It may be of great advantages against a Navy of enemies, who by this may be undermined in the water and blown up.

- It may be of special use for the relief of any place besieged by water, to convey unto them invisible supplies; and so likewise for the surprisal of any place that is accessible by water.

- It may be of unspeakable benefit for submarine experiments.

The first military submarines

The first military submarine was Turtle, a hand-powered egg-shaped device designed by the American David Bushnell, to accommodate a single man. It was the first verified submarine capable of independent underwater operation and movement, and the first to use screws for propulsion. During the American Revolutionary War, Turtle (operated by Sgt. Ezra Lee, Continental Army) tried and failed to sink a British warship, HMS Eagle (flagship of the blockaders) in New York harbor on September 7, 1776.

In 1800, France built a human-powered submarine designed by Robert Fulton, the Nautilus. It proved capable of using mines to destroy two warships during demonstrations. The French eventually gave up with the experiment in 1804, as did the British when they later tried the submarine.

During the War of 1812, in 1814 Silas Halsey lost his life while using a submarine in unsuccessful attack on a British warship stationed in New London harbor.

In 1851, a Bavarian artillery corporal, Wilhelm Bauer, took a submarine designed by him called the Brandtaucher (fire-diver) to sea in Kiel Harbour. This submarine was built by August Howaldt and powered by a treadwheel. It sank but the crew of 3 managed to escape. The submarine was raised in 1887 and is on display in a museum in Dresden.

Submarines in the American Civil War

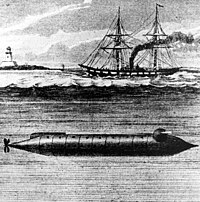

During the American Civil War, the Union was the first to field a submarine. The French-designed Alligator was the first U.S. Navy sub and the first to feature compressed air (for air supply) and an air filtration system. She was the first submarine to carry a diver lock which allowed a diver to plant electrically-detonated mines on enemy ships. Initially hand-powered by oars, she was converted after 6 months to a screw propeller powered by a hand crank. With a crew of 20, she was larger than Confederate submarines. Alligator was 47 feet (14.3 meters) long and about 4 feet (1.2 meters) in diameter. She was lost in a storm off Cape Hatteras on April 1, 1863 while uncrewed and under tow to her first combat deployment at Charleston.

The Confederate States of America fielded several human-powered submarines including CSS H. L. Hunley (named for one of her financiers, Horace Lawson Hunley) . The first Confederate submarine was the 30-foot long Pioneer which sank a target schooner using a towed mine during tests on Lake Pontchartrain but she was not used in combat. She was scuttled after New Orleans was captured and in 1868 was sold for scrap.

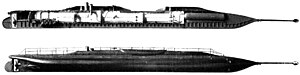

CSS Hunley was intended for attacking the North's ships, which were blockading the South's seaports. The submarine had a long pole with an explosive charge in the bow, called a spar torpedo. The sub had to approach an enemy vessel, attach the explosive, move away, and then detonate it. It was extremely hazardous to operate, and had no air supply other than what was contained inside the main compartment. On two occasions, the sub sank; on the first occasion half the crew died and on the second, the entire eight-man crew (including Hunley himself) drowned. On February 18, 1864 Hunley sank USS Housatonic off the Charleston Harbor, the first time a submarine successfully sank another ship, though she sank in the same engagement shortly after signaling her success. Another Confederate submarine was lost on her maiden voyage in Lake Pontchartrain; she was found washed ashore in the 1870s and is now on display at the Louisiana State Museum. Submarines did not have a major impact on the outcome of the war, but did portend their coming importance to naval warfare and increased interest in their use in naval warfare.

Mechanically-powered submarines (late 1800s)

The first submarine that did not rely on human power for propulsion was the French Navy submarine Plongeur, launched in 1863, and equipped with a reciprocating engine using compressed air from 23 tanks at 180 psi [1].

The first combustion-powered submarine was the steam and peroxide driven Ictineo II, launched in 1867 by Narcís Monturiol. It was originally launched in 1864 as a human-powered submarine, propelled by 16 men. [1].

The 14 meter long craft was designed to carry a crew of two, dive 30 metres (96 feet), and demonstrated dives of two hours. When on the surface it ran on a steam engine, but underwater such an engine would quickly consume the submarine's oxygen. So Monturiol turned to chemistry to invent an engine that ran on a reaction of potassium chlorate, zinc, and manganese peroxide. The beauty of this method was that the reaction which drove the screw released oxygen, which when treated was used in the hull for the crew and also fed an auxiliary steam engine that helped propel the craft under water. In spite of successful demonstrations in the Port of Barcelona, Monturiol was unable to interest the Spanish navy, or the navy of any other country.

In 1870, French writer Jules Verne published the science fiction classic Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, which concerns the adventures of a maverick inventor in Nautilus, a submarine more advanced than any that existed at that time. The story inspired inventors to build more advanced submarines.

In 1879, the Peruvian government, during theWar of the Pacific commissioned and built a submarine. That was the fully operational Toro Submarino, which nevertheless never saw military action before being scuttled after the defeat of that country in the war to prevent its capture by the enemy. That same year, a Manchester curate, the Reverend George Garrett built the steam-powered Resurgam at Birkenhead. Garrett intended to demonstrate the 12m long vehicle to the Royal Navy at Portsmouth, but had mechanical problems, and while under tow the submarine was swamped and sank off North Wales.

The first submarine built in series, however, was human-powered. It was the submarine of the Polish inventor Stefan Drzewiecki — 50 units were built in 1881 for Russian government. In 1884 the same inventor built an electric-powered submarine.

Discussions between George Garret and Swede Thorsten Nordenfelt led to a series of steam powered submarines. The first was the Nordenfelt I, a 56 tonne, 19.5 metre long spindle shaped vessel similar to the Resurgam, with a range of 240 kilometres and armed with a single torpedo in 1885. Greece, fearful of the return of the Ottomans, purchased it. Nordenfelt then built the Nordenfelt II, a 30 metre long submarine with twin torpedo tubes, which he sold to a worried Ottoman navy. Nordenfelt's efforts culminated in 1887 with the Nordenfelt IV, with twin motors and twin torpedoes. It was sold to the worried Russians, but proved unstable, ran aground and was scrapped.

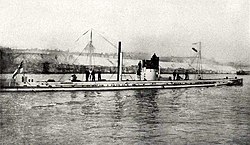

The first fully capable military submarine was the electrically powered vessel built by the Spanish engineer and sailor, Isaac Peral, for the Spanish Navy. It was launched on September 8 1888. It had two torpedoes, new air systems, and a hull shape and propeller and cruciform external controls anticipating later designs. Its underwater speed was ten knots, but it suffered from the short range of battery powered systems. In June 1890 Peral's submarine launched the first torpedo fired from a submarine under the sea. The Spanish Navy scrapped the project.

Many more submarines were built at this time by various inventors, but they were not to become effective weapons until the 20th century.

Late 1800s to World War I

The turn of century era marked a pivotal time in the development of submarines, with a number of important technologies making their debut, as well as the widespread adoption and fielding of submarines by a number of nations. Diesel electric propulsion would become the dominant power system and things such as the periscope would become standardized. Large numbers of experiments were done by countries on effective tactics and weapons for submarines, all of which would culminate in them making a large impact on coming World War I.

In 1895, the Irish inventor John Philip Holland designed submarines that, for the first time, made use of internal combustion engine power on the surface and electric battery power for submerged operations. In 1902, Holland received U.S. patent 708,553. Some of his vessels were purchased by the United States, the United Kingdom, the Imperial Russian Navy, and Japan, and commissioned into their navies around 1900. The US Navy commissioned its first submarine, the USS Holland in 1900, and the Imperial Japanese Navy purchased five similar designs in 1904.

Commissioned in June 1900, the French steam and electric submarine Narval introduced the classic twin-hull design, with an inner hull inside an outer hull. France was "undoubtedly the first navy to have an effective submarine force" (Conway Marine "Steam, Steel and Shellfire"). These 200 tons ships had a range of over 100 miles on the surface, and over 10 miles underwater. The French submarine Aigette in 1904 further improved the concept by using a diesel rather than a gasoline engine for surface power. Large numbers of these submarines were built, with seventy-six completed before 1914.

Submarines during World War I

The first time military submarines had significant impact on a war was in World War I. Forces such as the U-boats of Germany saw action in the First Battle of the Atlantic. The U-boats' ability to function as practical war machines relied on new tactics, their numbers, and submarine technologies such as combination diesel/electric power system that had been developed in the preceding years. More like submersible ships than the submarines of today, U-boats operated primarily on the surface using regular engines, submerging occasionally to attack under battery power. They were roughly triangular in cross-section, with a distinct keel, to control rolling while surfaced, and a distinct bow.

Interwar developments

Various new submarine designs were developed during the interwar years. Among the most notorious ones were Submarine aircraft carriers, equipped with waterproof hangar and steam catapult and which could launch and recover one or more small seaplanes. The submarine and her plane could then act as a reconnaissance unit ahead of the fleet, an essential role at a time when radar still did not exist. The first example was the British HMS M2, followed by the French Surcouf, and numerous aircraft-carrying submarines in the Imperial Japanese Navy. The 1929 Surcouf was also designed as an "underwater cruiser," intended to seek and engage in surface combat.

Submarines during World War II

Germany

Germany had the largest submarine fleet during World War II. Due to the Treaty of Versailles limiting the surface navy, the rebuilding of the German surface forces had only begun in earnest a year before the outbreak of World War II. Having no hope of defeating the vastly superior Royal Navy decisively in a surface battle, the German High Command immediately stopped all construction on capital surface ships save the nearly completed Bismarck class battleships and two cruisers and switched the resources to submarines, which could be built more quickly. Though it took most of 1940 to expand the production facilities and get the mass production started, more than a thousand submarines were built by the end of the war.

Germany put submarines to devastating effect in the Second Battle of the Atlantic in World War II, attempting but ultimately failing to cut off Britain's supply routes by sinking more ships than Britain could replace. The supply lines were vital to Britain for food and industry, as well as armaments from the USA. Although the U-boats had been updated in the intervening years, the major innovation was improved communications, encrypted using the famous Enigma cipher machine. This allowed for mass-attack tactics or "wolf packs", (Rudel), but was also ultimately the U-boats' downfall.

After putting to sea, the U-boats operated mostly on their own trying to find convoys in areas assigned to them by the High Command. If a convoy was found, the submarine did not attack immediately, but shadowed the convoy to allow other submarines in the area to find the convoy. These were then grouped into a larger striking force and attacked the convoy simultaneously, preferably at night while surfaced.

In the first half of the War the submarines scored spectacular successes with these tactics, but were too few to have any decisive success. In the second half Germany had enough submarines, but this was more than nullified by equally increased numbers of convoy escorts, aircraft, and technical advances like radar and sonar. Huff-Duff and Ultra allowed the Allies to route convoys around wolf packs when they detected them from their radio transmissions.

Winston Churchill wrote that the U-boat threat was the only thing that ever gave him cause to doubt the Allies' eventual victory.

Japan

Main article: Imperial Japanese Navy submarines

Japan had by far the most varied fleet of submarines of World War II, including manned torpedoes (Kaiten), midget submarines (Ko-hyoteki, Kairyu), medium-range submarines, purpose-built supply submarines (many for use by the Army), long-range fleet submarines (many of which carried an aircraft), submarines with the highest submerged speeds of the conflict (Sentaka I-200), and submarines that could carry multiple bombers (WWII's largest submarine, the Sentoku I-400). These submarines were also equipped with the most advanced torpedo of the conflict, the oxygen-propelled Type 95 (what U.S. historian Samuel E. Morison postwar called "Long Lance").

Overall, despite their technical prowess, Japanese submarines were relatively unsuccessful. They were often used in offensive roles against warships, which were fast, maneuverable and well-defended compared to merchant ships. In 1942, Japanese submarines sank two fleet aircraft carriers, one cruiser, and several destroyers and other warships, and damaged many others, including two battleships. They were not able to sustain these results afterwards, as Allied fleets were reinforced and became better organized. By the end of the war, submarines were instead often used to transport supplies to island garrisons. During the war, Japan managed to sink about 1 million tons of merchant shipping (184 ships), compared to 1.5 million tons for Great Britain (493 ships), 4.65 million tons for the US (1,079 ships) and 14.3 million tons for Germany (2,840 ships).

Early models were not very maneuverable under water, could not dive very deep, and lacked radar. (Later in the war units that were fitted with radar were in some instances sunk due to the ability of US radar sets to detect their emissions. For example, Batfish (SS-310) sunk three such equipped submarines in the span of four days). After the end of the conflict, several of Japan's most original submarines were sent to Hawaii for inspection in "Operation Road's End" (I-400, I-401, I-201 and I-203) before being scuttled by the U.S. Navy in 1946, when the Soviets demanded access to the submarines as well.

United States

Meanwhile, the US used its submarines to attack merchant shipping (commerce raiding or guerre de course), in an effort to starve both Japanese Pacific island forces and the home islands.

Where Japan had the finest submarine torpedoes of the war, the USN had perhaps the worst, the Mark 14 steam torpedo, with a Mk 6 magnetic influence exploder designed to explode under the hull of the target vessel and a Mk 5 contact exploder, neither of which was reliable. For the first twenty months of the war, senior Submarine Force commanders (including RADM Ralph Christie, ComSouthWestPac, a key member of the Mk 6's design team) attributed the torpedo failures to poor approach and attack techniques by submarine commanders. The depth control mechanism of the Mark 14 (designed for an earlier slower-running torpedo) was corrected in August, 1942, but field trials for the exploders were not even ordered until mid-1943, when tests in Hawaii and Australia confirmed the flaws.

The Mk 6 exploder was corrected by deactivating its magnetic influence mechanism and changing the firing pin of the contact exploder from one of high-friction steel to a less-friction alloy. The modifications were retro-fitted on torpedoes in service and incorporated into new production, after which the Mark 14 became a reliable weapon.

In September 1943 the Mark 18 electric torpedo was placed into service to provide a "wakeless" torpedo, but its range and speed were less than that of the Mark 14 and it had a smaller warhead. It too showed flaws that had not been corrected by testing: its battery produced hydrogen gas that could not be vented and it showed a disturbing tendency to "run circular" (that is, to travel in a circular path back to the firing submarine). The losses of the USS Tang and the USS Tullibee in 1944 resulted from self-inflicted hits by Mark 18 torpedoes fired from their stern tubes (which hit the submarines amidships), and the USS Wahoo may have been severely crippled by a circular hit on her bow before being bombed by aircraft.

During World War II 314 submarines served in the United States Navy. 111 boats were in commission on 7 December 1941, with 38 of these considered modern "fleet boats", and of that number, 23 were lost. 203 submarines from the Gato, Balao, and Tench classes were commissioned during the war, with 29 lost. In total the United States Navy lost 52 boats to all causes during hostilities, and 41 of the losses were directly attributable to enemy action. 3,506 submariners were killed or missing-in-action.

At first, Japanese anti-submarine defenses proved less than effective against U.S. submarines. Japanese sub-detection gear was not as advanced as that of some other nations. The primary Japanese anti-sub weapon for most of WWII was the depth charge. During the first part of the war, the Japanese tended to set their depth charges too shallow, and U.S. subs not trapped in shallow waters were frequently able to take advantage of depth gradient temperatures in order to escape from many attacks.

Unfortunately, the deficiencies of Japanese depth-charge tactics were revealed in a June 1943 press conference held by U.S. Congressman Andrew J. May, a member of the House Military Affairs Committee who had visited the Pacific theater and received many confidential intelligence and operational briefings. At the press conference, May revealed that American submarines had a high survivability because Japanese depth charges were fused to explode at too shallow a depth, typically 100 feet (because Japanese forces believed U.S. subs did not normally exceed this depth). Various press associations sent this story over their wires, and many newspapers, including one in Honolulu, thoughtlessly published it. Soon enemy depth charges were rearmed to explode at a more effective depth of 250 feet. Vice Admiral Charles A. Lockwood, commander of the U.S. submarine fleet in the Pacific, later estimated that May's revelation cost the navy as many as ten submarines and 800 crewmen.[2] [3]

In addition to resetting their depth charges to deeper depths, Japanese anti-submarine forces also began employing auto-gyro aircraft and MAD (magnetic anomaly detection) equipment to sink U.S. subs, particularly those plying major shipping channels or operating near the home islands. Despite this onslaught, U.S. sub sinkings of Japanese shipping continue to increase at a furious rate as more U.S. subs deployed each month to the Pacific. By the end of the war, U.S. submarines had destroyed more Japanese shipping than all other weapons combined, including aircraft.

Operationally, two commands in the Pacific Theater, Submarines Pacific and Submarines Southwest Pacific, conducted 1,588 war patrols, resulting in the firing of 14,748 torpedoes and the sinking of 1,392 enemy vessels of a total tonnage of 5.3 million tons. Over 200 warships were sunk, including a battleship, 8 aircraft carriers of varying sizes, 11 cruisers, 38 destroyers, 25 submarines (including 2 U-Boats), and 70 other escort vessels. Submarines Pacific was assigned 51 boats in 1941; by the end of the war 169 boats were assigned. Monthly war patrols averaged 27 in 1942 and increased to 47 in 1945, with a high of 57 patrols dispatched in May, 1945.

The schnorchel

Diesel submarines needed air to run their engines, and so carried very large batteries for submerged travel. These limited the speed and range of the submarines while submerged. The schnorchel (a prewar Dutch invention) was used to allow German submarines to run just under the surface, attempting to avoid detection visually and by radar. The German navy experimented with engines that would use hydrogen peroxide to allow diesel fuel to be used while submerged, but technical difficulties were great. The Allies experimented with a variety of detection systems, including chemical sensors to "smell" the exhaust of submarines.

Modern submarines

In the 1950s, nuclear power partially replaced diesel-electric propulsion. Equipment was also developed to extract oxygen from sea water. These two innovations gave submarines the ability to remain submerged for weeks or months, and enabled previously impossible voyages such as USS Nautilus's crossing of the North pole beneath the Arctic ice cap in 1958. Most of the naval submarines built since that time in the United States and the Soviet Union/Russia have been powered by nuclear reactors. The limiting factors in submerged endurance for these vessels are food supply and crew morale in the space-limited submarine.

While the greater endurance and performance from nuclear reactors mean that nuclear submarines are better for long distance missions or the protection of a carrier battle-force, conventional diesel-electric submarines have continued to be produced by both nuclear and non-nuclear powers, as they can be made stealthier, except when required to run the diesel engine to recharge the ship’s battery. Technological advances in sound dampening, noise isolation and cancellation have substantially eroded this advantage. Though far less capable regarding speed and weapons payload, conventional submarines are also cheaper to build. The introduction of air-independent propulsion boats led to increased sales numbers of such types of submarines.

During the Cold War, the United States of America and the Soviet Union maintained large submarine fleets that engaged in cat-and-mouse games; this tradition today continues, on a much-reduced scale. The Soviet Union suffered the loss of at least four submarines during this period: K-129 was lost in 1968 (which CIA attempted to retrieve from the ocean floor with the Howard Hughes-designed ship named Glomar Explorer), K 8 in 1970, K -219 in 1986 (subject of the film "Hostile Waters"), and Komsomolets (the only Mike class submarine) in 1989 (which held a depth record among the military submarines—1000m, or 1300m according to the article K-278). Many other Soviet subs, such as K-19 (first Soviet nuclear submarine, and first Soviet sub at North Pole) were badly damaged by fire or radiation leaks. The United States lost two nuclear submarines during this time: USS Thresher and Scorpion. The Thresher was lost due to equipment failure, and the exact cause of the loss of the Scorpion is not known.

The sinking of PNS Ghazi in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was the first submarine casualty in the South Asian region. The United Kingdom employed nuclear-powered submarines against Argentina in 1982 during the two nations' dispute over the Falkland Islands. The sinking of the antiquated cruiser ARA General Belgrano by HMS Conqueror was the first sinking by a nuclear-powered submarine in war.

Naming

Ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs or boomers in American slang) carry submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM) with nuclear warheads, for attacking strategic targets such as cities or missile silos anywhere in the world. They are currently universally nuclear-powered, to provide the greatest stealth and endurance. (The first Soviet ballistic missile submarines were diesel-powered.) They played an important part in Cold War mutual deterrence, as both the United States and the Soviet Union had the credible ability to conduct a retaliatory strike against the other nation in the event of a first strike. This comprised an important part of the strategy of Mutual Assured Destruction.

The U.S. has 18 Ohio class submarines, of which 14 are Trident II SSBNs, each carrying 24 SLBMs. The American George Washington class "boomers" were named for famous Americans, and together with the Ethan Allen, Lafayette, James Madison, and Benjamin Franklin classes, these SSBNs comprised the Cold War-era "41 for Freedom." Later Ohio class submarines were named for states (recognizing the increase in striking power and importance, equivalent to battleships), with the exception that SSBN-730 gained the name of a Senator. The first four Ohio class vessels were equipped with Trident I, and are now being converted to carry Tomahawk guided missiles.

For Russia, see List of NATO reporting names for ballistic missile submarines.

The Royal Navy possess a single class of four ballistic missile submarines (what RN call "bombers", for their function), the Vanguard class. The Royal Navy's previous ballistic missile submarine class was the Resolution class which also consisted of four boats. The Resolutions, named after battleships to convey the fact they were the new capital ships, were decommissioned when the Vanguards entered service in the 1990s.

France operates a force de frappe including a nuclear ballistic submarine fleet made up of one SSBN Redoutable class and three SSBNs of the Triomphant class. One additional SSBN of the Triomphant class is under construction.

The People's Republic of China's People's Liberation Army Navy's SLBM inventory is relatively new. China launched its first nuclear armed submarine in April 1981. The PLAN currently has 1 Xia class ("Type 92") at roughly 8,000 tons displacement. The Type 92 is equipped with 12 SLBM launching tubes. China's SLBM program is built around its JL-1 inventory. The Chinese Navy is estimated to have 24 JL-1s. The JL-1 is basically a modified DF-21.

The PLAN plans to replace its JL-1 with an unspecified number of the longer ranged, more modern JL-2s. Deployment on the JL-2 reportedly began in late 2003.

Major submarine incidents since 2000

Main Article: Major submarine incidents since 2000

Since submarines have been actively deployed, there have been several incidents involving submarines which were not part of major combat. Most of these incidents were during the Cold War, but some are more recent. Since the year 2000 there have been 9 major naval incidents involving submarines. There were three Russian submarine incidents, in two of which the submarines in question were lost, along with three United States submarine incidents, one Chinese incident, one Canadian, and one Australian incident. In August 2005, the Russian PRIZ, an AS-28 rescue submarine was trapped by cables and/or nets off of Petropavlovsk, and saved when a British ROV cut them free in a massive international effort.

Submarine propulsion

Until the advent of nuclear marine propulsion, most 20th century submarines used batteries for running underwater and gasoline (petrol) or diesel engines on the surface and to recharge the batteries. Early boats used gasoline but this quickly gave way to paraffin, then diesel, because of reduced flammability. Diesel-electric became the standard means of propulsion. Initially the diesel or gasoline engine and the electric motor were on the same shaft which also drove a propeller with clutches between each of them. This allowed the engine to drive the electric motor as a generator to recharge the batteries and also propel the submarine if required. The clutch between the motor and the engine would be disengaged when the boat dived so that the motor could be used to turn the propeller. The motor could have more than one armature on the shaft — these would be electrically coupled in series for slow speed and parallel for high speed (known as "group down" and "group up" respectively).

In the 1930s the principle was modified for some submarine designs, particularly those of the U.S. Navy and the British U-class. The engine was no longer attached to the motor/propeller drive shaft but drove a separate generator which would drive the motors on the surface and/or recharge the batteries. This diesel-electric propulsion allowed much more flexibility, for example the submarine could travel slowly whilst the engines were running at full power to recharge the batteries as quickly as possible, reducing time on the surface, or use its snorkel. Also it was now possible to insulate the noisy diesel engines from the pressure hull making the submarine quieter.

There were other power sources attempted—oil-fired steam turbines powered the British "K" class submarines built during the First World War and in following years but these were not very successful. This was selected to give them the necessary surface speed to keep up with the British battle fleet.

Steam power was resurrected in the 1950s with the advent of the nuclear-powered steam turbine driving a generator which is now used in all large submarines. There was an attempt to use a very advanced lead cooled fast reactor on Project 705 "Lira" but it's maintenance was considered too expensive. By removing the requirement for atmospheric oxygen these submarines can stay submerged indefinitely so long as food supplies remain (air is recycled and fresh water distilled from seawater). These vessels always have a small battery and diesel engine/generator installation for emergency use when the reactors have to be shut down.

Anaerobic propulsion was employed by the first mechanically driven submarine Ictineo II in 1864. Ictineo's engine used a chemical mix containing a peroxide compound, that generated heat for steam propulsion while at the same time solved the problem of oxygen renovation in an hermetic container for breathing purposes. The system wasn't employed again until 1940 when the German Navy tested a system employing the same principles, the Walter turbine, on the experimental V-80 submarine and later on the naval U-791 submarine. At the end of the Second World War the British and Russians experimented with hydrogen peroxide/kerosene (paraffin) engines which could be used both above and below the surface. The results were not encouraging enough for this technique to be adopted at the time, although the Russians deployed a class of submarines with this engine type code named Quebec by NATO, they were considered a failure. Today several navies, notably Sweden now use air-independent propulsion boats which substitute liquid oxygen for hydrogen peroxide.

The German Type 212 submarine uses nine 34-kilowatt hydrogen fuel cell as air-independent propulsion, which makes it first series production submarine using fuel cell.

Most small modern commercial submarines which are not expected to operate independently use batteries which can be recharged by a mother-ship after every dive.

Towards the end of the 20th century, some submarines began to be fitted with pump-jet propulsors instead of propellers. Although these are heavier, more expensive, and often less efficient than a propeller, they are significantly quieter, giving an important tactical advantage.

A possible propulsion system for submarines is the magnetohydrodynamic drive, or "caterpillar drive", which has no moving parts. It was popularized in the movie version of The Hunt for Red October, written by Tom Clancy, which portrayed it as a virtually silent system. (In the book, a form of propulsor was used rather than an MHD.) Although some experimental surface ships have been built with this propulsion system, speeds have not been as high as those hoped. In addition, the noise created by bubbles, and the higher power settings a submarine's reactor would need, mean that it is unlikely to be considered for any military purpose.

See also

General

- Anti-submarine weapon

- Submarine

- AS-28 Russian Rescue Submarine Saved

- Submarines in the United States Navy

- Submarine cable

- Timeline of underwater technology

- Midget submarine

- Submarine aircraft carrier

- Submersible

- Semi-submersible

- Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle

- Autonomous Underwater Vehicle

- Modern Naval tactics

- Communication with submarines

- Submarine sandwich, named for its submarine-like shape

- Submarine simulator, a computer game genre

- List of submarine actions

- List of sunken nuclear submarines

- Depth charge and Depth charge (cocktail)

- Nuclear navy

- List of countries with submarines

Articles on specific vessels

Template:Groundbreaking submarines

- Nerwin (NR-1)

- Vesikko

- ORP Orzeł

- Ships named Nautilus

- List of submarines of the Royal Navy

- List of submarines of the United States Navy

- List of Soviet submarines

- List of U-boats

- Kaiko (deepest submarine dive)

Articles on specific submarine classes

- List of submarine classes

- List of submarine classes of the Royal Navy

- List of Soviet and Russian submarine classes

- List of United States submarine classes

Patents

- U.S. patent 708,553 - Submarine boat

References

- Blair, Clay, Silent Victory (Vol.1), The Naval Institute Press, 2001

- Lanning, Michael Lee (Lt. Col.), Senseless Secrets: The Failures of U.S. Military Intelligence from George Washington to the Present, Carol Publishing Group, 1995

- "Steam, Steel and Shellfire, The steam warship 1815-1905", Conway's History of the Ship ISBN 0-7858-1413-2

- Blair, Clay Jr., Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan, ISBN 1-55750-217-X

- Lockwood, Charles A. (VAdm, USN ret.), Sink 'Em All: Submarine Warfare in the Pacific, (1951)

- O'Kane, Richard H. (RAdm, USN ret.), Clear the Bridge!: The War Patrols of the USS Tang, ISBN 0-89141-346-4

- O'Kane, Richard H. (RAdm, USN ret.), Wahoo: The Patrols of America's Most Famous WII Submarine, ISBN 0-89141-301-4

External links

- John Holland: http://www.clarelibrary.ie/eolas/coclare/people/holland.htm

- German Submarines of WWII: http://www.uboat.net

- Submaine Simulations: http://www.subsim.com

- German Midget Submarine - Seehund : http://www.one35th.com/seehund/sh_index.html

- Submarines of WWI: http://www.dropbears.com/w/ww1subs/index.htm

- German Midget Submarine - Molch : http://www.one35th.com/submarine/molch_main.htm

- Role of the Modern Submarine: http://www.submarinehistory.com/21stCentury.html

- Submariners of WWII: http://www.oralhistoryproject.com — World War II Submarine Veterans History Project

- German submarines using peroxide: http://www.dataphone.se/~ms/ubootw/boats_walter-system.htm

- record breaking Japanese Submarines: http://www.combinedfleet.com/ss.htm

- German U-Boats 1935–1945: http://www.u-boot-archiv.de

- U.S. ship photo archive: http://www.navsource.org

- Israeli missile trials: http://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/israel/missile/popeye-t.htm

- The Sub Report: http://www.thesubreport.com

- The Invention of the Submarine: http://www.vectorsite.net/twsub1.html

- Submersibles and Technology by Graham Hawkes http://www.deepflight.com/subs/index.htm

- Royal Navy submarine history http://www.royal-navy.mod.uk/static/pages/3164.html

- A century of Royal Navy submarine operations http://www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/cno/n87/usw/issue_12/holland.html

- Royal Navy submarines http://www.solarnavigator.net/royal_navy_submarines.htm

- Still floating submarine Lembit (1936) http://www.meremuuseum.ee/et/ships/lembit.html

- ^ a b http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/sub-history4.htm

- ^ Blair, Clay, Silent Victory Vol.1, pg 397.

- ^ Lanning, Michael Lee (Lt. Col.), Senseless Secrets: The Failures of U.S. Military Intelligence from George Washington to the Present, Carol Publishing Group, 1995