Milas

Milas | |

|---|---|

District | |

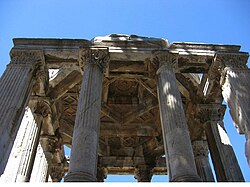

Gümüşkesen chambered tomb monument in Milas, built during the city's Roman Period and modelled on the Mausoleum of Mausolus | |

Location of Milas within Turkey. | |

| Country | |

| Region | Aegean |

| Province | Muğla |

| First cited | In early-7th century BC context as Mylasa in connection with King Gyges of Lydia's seizure of the Lydian throne, with help from the Carian chieftain Arselis |

| Carians to Menteşe Turkish period (14th century) | Cited as Mylasa and variants |

| Turkish period (14th century) to the present | Cited as Milas and the capital of the Beylik of Menteşe, after 1420 an Ottoman sanjak, after 1923 a district and its center under the Turkish Republic |

| Municipalities | 5 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Muhammet Tokat (Republican People's Party) |

| Area | |

| • District | 2,110.25 km2 (814.77 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Urban | Template:Turkey district populations |

| • District | Template:Turkey district populations |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Area code | (+90) 252 |

| Licence plate | 48 |

| Website | Milas Municipality Prefecture of Milas |

Milas (ancient Greek Mylasa Μύλασα) is an ancient city and the seat of the district of the same name in Muğla Province in southwestern Turkey. The city commands a region with an active economy, and the region is very rich in history and its remains, the whole territory of Milas district containing a remarkable twenty-seven archaeological sites of note.[2] The city was the first capital of ancient Caria and of the Anatolian beylik of Menteşe in medieval times. There was a Jewish community.[3]

The centre of Milas presents the overall characteristics of a well-grown city focused on agricultural and aquacultural processing, related industrial activities, services, transportation (particularly since the opening of Milas-Bodrum Airport), tourism and culture. The center is at a distance of about twenty km from the coast and is actually closer to the airport than Bodrum itself, with many late arrival passengers of the high season increasingly opting to stay in Milas rather than in Bodrum where accommodation is likely to be difficult to find.

Milas district covers a total area of 2167 km2 and this area follows a total coastline length of 150 km, both to the north-west in the Gulf of Güllük and to the south along the Gulf of Gökova, and to these should be added the shores of Lake Bafa in the north divided between the district area of Milas and that of Aydın district of Söke.

Along with the province seat of Muğla and the province's southernmost district of Fethiye, Milas is among the prominent settlements of south-west Turkey, these three centers being on a par with each other in terms of all-year population and the area their depending districts cover. Five townships which have their own municipalities and a total of 114 villages depend Milas, distinguishing the district with a record number of dependent settlements for a very wide surrounding region. Milas center is situated on a fertile plain at the foot of Mount Sodra on and around which sizable quarries of the white marble are found and have been used since very ancient times.

Milas's political colour has been centre-left for the last decade.

Etymology

The name Mylasa, with the old Anatolian ending in -asa is sufficient proof of very early foundation. On the basis of the -mil syllable found also in the name the Lycians called themselves Trmili, a theory held by some, but by no means proved connects the name of Mylasa with the passage of the Lycians from Miletus, also claimed to be a Lycian foundation under the name Millawanda by Ephorus, to their final home in the south. But there is nothing else to suggest a Lycian origin for the name Mylasa.[4] Stephanus of Byzantium in his Ethnica says that the city took its name from a certain Mylasus, son of Chrysaor and a descendant of Sisyphus and Aeolus, an explanation some sources deem unsubstantial for a Carian city.[5]

History

The city's earliest historical mention is at the beginning of the 7th century BC, when a Carian leader from Mylasa by name Arselis is recorded to have helped Gyges of Lydia in his contest for the Lydian throne. The same episode is at the origin of the accounts surrounding the beginning of the cult for and the erection of the statue of Labrandean Zeus in the neighboring sanctuary of Labranda, held sacred by peoples across western Anatolia, with the statue holding the labrys brought over by Arselis from Lydia. Labrandean Zeus (sometimes also named "Zeus Stratios") was one of the three deities proper to Mylasa, all named Zeus but each bearing indigenous characteristics. Of these, the cult of Zeus Carius (Carian Zeus) was also notable in being exclusively reserved, aside from the Carians, to their Lydian and Mysian kinsmen. One of the finest temples was also the one dedicated to Zeus Osogoa (originally, just Osogoa), traceable to times when the Carians had been a maritime folk and which recalled to Pausanias the Acropolis of Athens.[6]

Persian period

Under Achaemenid rule Mylasa was the chief city of Caria. A ruler appointed by the Persian Emperor (satrap) ruled the city in varying degrees of allegiance to the emperor. Between 460-450 BC, Mylasa was a regionally prominent member of the Delian League, like most Carian cities, but the Persian rule was restored towards the end of the same century.

Hecatomnid dynasty

The dynasty named the Hecatomnids, founded by Hecatomnus and continued under his sons and daughters, were officially satraps of the Persian Empire but Greek in language and culture, as their inscriptions and coins witness. Mylasa was at once their hometown and their capital. During the long and striking reign of Mausolus, they became virtual rulers of Caria and of a sizable surrounding region between 377-352 BC. It was during Mausolus's reign that the capital was moved to Halicarnassus, but Mylasa retained its importance. Mausolus was the builder of the famous Mausoleum of Mausolus. The international term "Mausoleum" derives from this Carian ruler. In the 1st century BC, the two major, and antagonistic, politicians of the city were Euthydemos (in Greek Εὐθύδημος) and Hybreas (Ὑβρέας) and, when the first died, the second spoke at his funeral coining the proverbial phrase ”You are a necessary evil: we can live neither with you nor without you”.

Roman period

In 40 BCE Mylasa suffered great damage when it was taken by Labienus in the Roman Civil War. In the Greco-Roman period, though the city was contested among the successors of Alexander, it enjoyed a season of brilliant prosperity, and the three neighbouring towns of Euromus, Olymos and Labranda were included within its limits. Mylasa is frequently mentioned by ancient writers. At the time of Strabo the city boasted two remarkable orators, Euthydemos and Hybreas. Various inscriptions tell us that the Phrygian cults were represented here by the worship of Sabazios; the Egyptian, by that of Isis and Osiris. There was also a temple of Nemesis. An inscription from Mylasa[7] provided one of the few certain data about the life of Cornelius Tacitus, identifying him as governor of Asia in 112-13.

Christian era

Among the ancient bishops of Mylasa was Saint Ephrem (fifth century), whose feast was kept on January 23, and whose relics were venerated in neighbouring city of Leuke. Cyril and his successor, Paul, are mentioned by Nicephorus Callistus[8] and in the Life of Saint Xene. Michel Le Quien mentioned the names of three other bishops,[9] and since his time the inscriptions discovered refer to two others, one anonymous,[10] the other named Basil, who built a church in honour of Saint Stephen.[11] The Saint Xene referred to above was a Roman noblewoman who, to escape the marriage which her parents wished to force upon her, donned male attire, left her country, changed her name from Eusebia to Xene ("stranger"), and lived first on the island of Cos, then at Mylasa. Since the Fourth Crusade, Mylasa has remained a titular see of the Roman Catholic Church, Mylasensis; the seat has been vacant since the death of the last bishop in 1966.[12]

Turkish era

Beys of Menteşe

Milas and the surrounding region (the Byzantine theme of Mylasa and Melanoudion) was taken over by the Turks under the command of Menteşe Bey in the late thirteenth century, who gave his name to the beylik (Menteşe) that established its capital in the city. The administrative center of his descendants was the castle of Beçin located in the contemporary dependant township of the same name at a distance of 5 km (3 mi) from Milas and which was easier to defend.

Ottoman rule

Milas, together with the entire Beylik of Menteşe was taken over by the Ottoman Empire in 1390. However, just twelve years later, Tamerlane and his forces overcame the Ottomans in the Battle of Ankara, and returned control of this region to its former rulers, the Menteşe Beys, as he did for other Anatolian beyliks. Milas was brought back under Ottoman control, this time in 1420 by the Sultan Mehmed I. One of the first acts of the Ottomans was to transfer the regional administrative seat to Muğla.

At the turn of the twentieth century, according to 1912 figures, Milas' urban center had a population of 9,000, of whom some 2,900 were Greek, a thousand or so Jewish, and the remaining majority were Turkish.[13] The Greeks of Milas were exchanged with Turks living in Greece under the 1923 agreement for the exchange of Greek and Turkish populations between the two countries, while the sizable Jewish community remained as a presence till the 1950s, at which time they emigrated to Israel; Jews formerly of Milas still visit frequently to this day.

Sights of interest

The walls surrounding the temenos of one of the temples dedicated to one of the Zeus (probably Zeus Osogoa and built in the first century BC) are still visible, as well as a row of columns.

The eighteenth-century English traveller Richard Pococke relates, in his Travels, having seen the temple of Augustus here; its materials have since partially been taken by Turks to build a mosque.

One of the two ancient symbols of the town is "Baltalıkapı" (Gate with an axe), a well-preserved Roman gate called as due to the eponymous double-headed axe (labrys) carved into a keystone.

There is also a two-storied monumental Roman tomb dating from the 2nd century AD, called "Gümüşkesen" today and which gives its name to a whole quarter of Milas, and referred to as "Dystega" in some dated sources. This monument is most likely a simplified copy of the famous tomb of Mausolus in Halicarnassus.

There are a number of historical Turkish buildings in Milas, dating from both the Menteşe and the Ottoman periods. A number of old houses built in the nineteenth or early twentieth century that have been preserved in their original appearance are also worthy of mention. Among the three most important mosques of Milas, The Great Mosque dating from 1378 and Orhan Bey Mosque dating from 1330 were built when Milas was the capital of the Turkish principality of Menteşe. The slightly more imposing Firuz Bey Mosque was built shortly the first incorporation of Milas into the Ottoman Empire and bears the name of the city's first Ottoman administrator.

Milas carpets and rugs woven of wool have been internationally famous for centuries and bear typical features. In our day, they are no longer produced in the city of Milas, but rather in a dozen villages around Milas. For the whole territory of Milas district, up to 7000 weavers' looms remain active, either full-time or at intervals following the demand, which remains quite lively both in Turkey and abroad.

Beçin Castle, the capital of Menteşe Beys, is situated at the dependent township of Beçin, at a distance of 5 kilometers from Milas city. The fortress has been restored in 1974, and the compound includes two mosques, two medreses, a hamam, the remains of a Byzantine chapel as well as traces from earlier periods.

At a distance of 14 km. from Milas center, set on a steep hillside and surrounded by pine forests is the ancient Carian cult center of Labranda, its name echoing once again the eponymous tradition of labrys. The ruins, including a temple, banqueting halls and tombs, were excavated by a Swedish team in early 20th century, as well as the spectacular views over the valley, attract the interest of rather few adventurous visitors prepared for the climb.

Notable people from Milas

- Hecatomnus; Founder of the Hecatomnid dynasty,

- Mausolus; Satrap of the Persian Empire, virtual ruler of Caria between 377-352 BC, builder of the famous Mausoleum of Halicarnassus.

- Rabbi Albert Jean Amateau: U.S. Sephardic Jew community leader and social activist.

- Turhan Selçuk: Turkish cartoonist. Creator of the fictional character Abdülcanbaz and the homonymous serial comics.

- Edip Günay: Musicologist

- Tolga Çandar: Turkish singer

- Keremcem Dürük: Turkish singer and TV actor

Picture gallery

-

Typical chimneys of local style

-

Stork nest on top of an ancient column

-

Backstreets of Milas

See also

Footnotes

- ^ "Area of regions (including lakes), km²". Regional Statistics Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2002. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ^ Some of these are (with the names of modern-day settlements indicated in cases where ancient sites are found right within these); Beçin, Chalcetor, Euromus -originally Kyromus-, Heracleia by Latmus (Kapıkırı), Hydae -originally Kydae- (Damlıboğaz), Iasos (Kıyıkışlacık), Keramos/Ceramus (Ören), Kuyruklu Kale (Yusufça), Labranda, Olymus -originally Hylimus-.

- ^ Melek Çolak, Milâs Yahudileri, Ümit Yayıncılık ve Matbaacılık Ltd. Şti., 2003, p. 75.

- ^ Antony G. Keen (1998). Dynastic Lycia: A political history of the Lycians and their relations with foreign powers, C. 545-362 ISBN 978-90-04-10956-8. Brill Publishers, Leiden.

- ^ George Ewart Bean (1989). Turkey beyond the Meander ISBN 978-0-7195-4663-1. John Murray Publishers Ltd, London.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece: VIII, x, 3.

- ^ The inscription was published in Bulletin de correspondance hellénique, 1890, pp. 621-623.

- ^ Nicephorus Callistus Xanthopoulos. Historia ecclesiastica: XIV, 52.

- ^ Michel Le Quien. Oriens Christianus, I, 921.

- ^ Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum, 9271.

- ^ Bulletin de correspondance hellenique, XIV, 616.

- ^ Mylasa (Titular See); Catholic Encyclopedia: Mylasa".

- ^ According to the same sources, for the whole area covered by the subdistrict (kaza) of Milas, these figures were 28,500 for the whole population, 21,000 of which were Turkish and 3,500 to 7,000, according to varying sources, were Greeks. Data from Anagiostopoulou 1997 and Sotiriadis 1918.

External links

- Milas

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.