Religion in Canada

Religion in Canada (2011 National Household Survey)[1]

Religion in Canada encompasses a wide range of groups and beliefs.[2] The majority of Canadians are Christians, with the Catholic Church having the most adherents. Christians, representing 67.3% of the population, are followed by people having no religion with 23.9%[1] of the total population. Islam is the second largest religion in Canada, practised by 3.2% of the population.[3] Rates of religious adherence are steadily decreasing.[4][5] The preamble to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms refers to God and the monarch carries the title of "Defender of the Faith". However, Canada has no official religion, and support for religious pluralism and freedom of religion is an important part of Canada's political culture.[6][7]

Before the European colonization Aboriginal religions were largely animistic, including an intense reverence for spirits and nature.[8] The French colonization beginning in the 17th century established a Roman Catholic francophone population in Acadia and in New France later Lower Canada, now Nova Scotia and Quebec. It has been followed by a British colonization that brought Anglicans and other Protestants to Upper Canada, now Ontario.

With Christianity in decline after having once been central and integral to Canadian culture and daily life,[9] Canada has become a post-Christian, secular state.[10][11][12] The majority of Canadians consider religion to be unimportant in their daily lives,[13] but still believe in God.[14] The practice of religion is now generally considered a private matter throughout society and the state.[15]

Government and religion

Canada today has no official church, and the government is officially committed to religious pluralism.[16] While the Canadian government's official ties to religion, specifically Christianity are few, the Preamble to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms make reference to "the supremacy of God.,[17] The national anthem in both official languages also refers to God.[18] Nevertheless, the rise of irreligion within the country and influx of non-Christian peoples has led to a greater separation of government and religion,[19] demonstrated in forms like "Christmas holidays" being called "winter festivals" in public schools.[20] Some religious schools are government-funded as per Section Twenty-nine of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[21]

Canada is a Commonwealth realm in which the head of state is shared with 15 other countries. As such Canada follows the United Kingdom's succession laws for its monarch which bar Roman Catholics from inheriting the throne.[22] Within Canada, the Queen's title includes the phrases "By the Grace of God" and "Defender of the Faith."[23]

Christmas and Easter are nationwide holidays, and while Jews, Muslims, and other religious groups are allowed to take their holy days off work, they do not share the same official recognition.[24] In 1957, the Parliament declared Thanksgiving "a day of general thanksgiving to almighty God for the bountiful harvest with which Canada has been blessed."[25]

In some parts of the country Sunday shopping is still banned, but this is steadily becoming less common. There was an ongoing battle in the late 20th century to have religious garb accepted throughout Canadian society, mostly focused on Sikh turbans. Eventually the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the Canadian Armed Forces and other federal government agencies accepted members wearing turbans.

Census results

In the Canada 2011 National Household Survey (the 2011 census did not ask about religious affiliation but the survey sent to a subset of the population did), 67% of the Canadian population list Roman Catholicism or Protestantism or another Christian denomination as their religion, considerably less than 10 years before in the Canada 2001 Census, where 77% of the population listed a Christian religion.[26] [27][28] Representing one out of three Canadians, the Roman Catholic Church in Canada is by far the country's largest single denomination. Those who listed no religion account for 24% of total respondents. In 2001 in British Columbia, however, 35% of respondents reported no religion — more than any single denomination and more than all Protestants combined.[29]

In the recent years there have been substantial rises in non-Christian religions in Canada. From the 1991 to 2011, Islam grew by 316%, Hinduism 217%, Sikhism 209%, and Buddhism 124%. The growth of non-Christian religions expressed as a percentage of Canada's population rose from 4% in 1991 to 8% in 2011. In terms of the ratio of non-Christians to Christians, it rose from 21 Christians (95% of religious population) to 1 non-Christian (5% of religious population) in 1991 to 8 Christians (89%) to 1 non-Christian (11%) in 2011, a rise of 135% of the ratio of non-Christians to Christians, or a decline of 6.5% of Christians to non-Christians, in 20 years.

| 19911 | 2001 | 20112 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Total Population | 26,944,040 | 29,639,035 | 32,852,300 | |||

| Christian | 22,503,360 | 83 | 22,851,825 | 77 | 22,102,700 | 67.3 |

| - Roman Catholic | 12,203,625 | 45.2 | 12,793,125 | 43.2 | 12,728,900 | 38.7 |

| - Total Protestant | 9,427,675 | 34.9 | 8,654,845 | 29.2 | ||

| - United Church of Canada | 3,093,120 | 11.5 | 2,839,125 | 9.6 | 2,007,610 | 6.1 |

| - Anglican Church of Canada | 2,188,110 | 8.1 | 2,035,495 | 6.9 | 1,631,845 | 5.0 |

| - Baptist | 663,360 | 2.5 | 729,470 | 2.5 | 635,840 | 1.9 |

| - Lutheran | 636,205 | 2.4 | 606,590 | 2.0 | 478,185 | 1.5 |

| - Protestant, not included elsewhere3 | 628,945 | 2.3 | 549,205 | 1.9 | ||

| - Presbyterian | 636,295 | 2.4 | 409,830 | 1.4 | 472,385 | 1.4 |

| - Christian Orthodox | 387,395 | 1.4 | 495,245 | 1.7 | 550,690 | 1.7 |

| - Christian, not included elsewhere4 | 353,040 | 1.3 | 780,450 | 2.6 | ||

| No Religious Affiliation | 3,397,000 | 12.6 | 4,900,095 | 16.5 | 7,850,600 | 23.9 |

| Other | 1,093,690 | 4.1 | 1,887,115 | 6.4 | 2,703,200 | 8.1 |

| - Muslim | 253,265 | 0.9 | 579,645 | 2.0 | 1,053,945 | 3.2 |

| - Hindu | 157,010 | 0.6 | 297,200 | 1.0 | 497,960 | 1.5 |

| - Sikh | 147,440 | 0.5 | 278,415 | 0.9 | 454,965 | 1.4 |

| - Buddhist | 163,415 | 0.6 | 300,345 | 1.0 | 366,830 | 1.1 |

| - Jewish | 318,185 | 1.2 | 329,990 | 1.1 | 329,500 | 1.0 |

| 1For comparability purposes, 1991 data are presented according to 2001 boundaries. 2The 2011 data is from the National Household Survey<[1] and so numbers are estimates. 3Includes persons who report only “Protestant”. 4Includes persons who report “Christian”, and those who report “Apostolic”, “Born-again Christian” and “Evangelical”. | ||||||

| Province/territory[30] | Christians | % | Non-religious | % | Muslims | % | Jews | % | Buddhists | % | Hindus | % | Sikhs | % | Traditional (Aboriginal) Spirituality | % | Other religions1 | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,152,200 | 60.32 | 1,126,130 | 31.56 | 113,445 | 3.18 | 10,900 | 0.31 | 44,410 | 1.24 | 36,845 | 1.03 | 52,335 | 1.47 | 15,100 | 0.42 | 16,605 | 0.47 | |

| 1,930,415 | 44.64 | 1,908,285 | 44.13 | 79,310 | 1.83 | 23,130 | 0.53 | 90,620 | 2.10 | 45,795 | 1.06 | 201,110 | 4.65 | 10,295 | 0.24 | 35,500 | 0.82 | |

| 803,640 | 68.43 | 311,105 | 26.49 | 12,405 | 1.06 | 11,110 | 0.95 | 6,770 | 0.58 | 7,720 | 0.66 | 10,200 | 0.87 | 7,155 | 0.61 | 4,245 | 0.36 | |

| 616,910 | 83.84 | 111,435 | 15.14 | 2,640 | 0.36 | 620 | 0.08 | 975 | 0.13 | 820 | 0.11 | 20 | 0.00 | 525 | 0.07 | 1,895 | 0.26 | |

| 472,720 | 93.19 | 31,330 | 6.18 | 1,200 | 0.24 | 175 | 0.03 | 400 | 0.08 | 635 | 0.13 | 100 | 0.02 | 30 | 0.01 | 685 | 0.14 | |

| 27,050 | 66.30 | 12,450 | 30.51 | 275 | 0.67 | 40 | 0.10 | 170 | 0.42 | 70 | 0.17 | 20 | 0.05 | 500 | 1.23 | 220 | 0.54 | |

| 690,460 | 78.19 | 197,665 | 21.18 | 8,505 | 0.94 | 1,805 | 0.20 | 2,205 | 0.24 | 1,850 | 0.20 | 390 | 0.04 | 570 | 0.06 | 2,720 | 0.30 | |

| 27,255 | 85.99 | 4,100 | 12.94 | 50 | 0.16 | 10 | 0.03 | 20 | 0.06 | 30 | 0.09 | 10 | 0.03 | 135 | 0.43 | 85 | 0.27 | |

| 8,167,295 | 64.55 | 2,927,790 | 23.14 | 581,950 | 4.60 | 195,540 | 1.55 | 163,750 | 1.29 | 366,720 | 2.90 | 179,765 | 1.42 | 15,905 | 0.13 | 53,080 | 0.42 | |

| 115,620 | 84.16 | 19,820 | 14.43 | 660 | 0.43 | 100 | 0.07 | 560 | 0.41 | 205 | 0.15 | 10 | 0.01 | 55 | 0.04 | 350 | 0.25 | |

| 6,356,880 | 82.27 | 937,545 | 12.12 | 243,430 | 3.15 | 85,100 | 1.10 | 52,390 | 0.68 | 33,540 | 0.43 | 9,275 | 0.12 | 2,025 | 0.03 | 12,340 | 0.16 | |

| 726,920 | 72.06 | 246,305 | 24.41 | 10,040 | 1.00 | 940 | 0.09 | 4,265 | 0.42 | 3,570 | 0.35 | 1650 | 0.16 | 12,240 | 1.21 | 2,810 | 0.28 | |

| 15,380 | 46.16 | 16,630 | 49.90 | 40 | 0.12 | 20 | 0.06 | 295 | 0.89 | 160 | 0.48 | 90 | 0.27 | 395 | 1.19 | 300 | 0.90 |

1Includes Aboriginal spirituality, Pagan, Wicca, Unity - New Thought - Pantheist, Scientology, Rastafarian, New Age, Gnostic, Satanist, etc.[31]

History

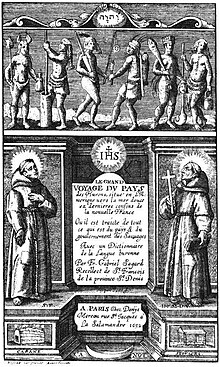

Before 1800s

Before the arrival of Europeans, the First Nations followed a wide array of mostly animistic religions and spirituality.[32][33] The first Europeans to settle in great numbers in Canada were French Latin Rite Roman Catholics, including a large number of Jesuits who established several missions in North America. They were dedicated to converting the Natives; an effort that eventually proved successful.[34]

The first large Protestant communities were formed in the Maritimes after they were conquered by the British.[35] Unable to convince enough British immigrants to go to the region, the government decided to import continental Protestants from Germany and Switzerland to populate the region and counterbalance the Roman Catholic Acadians.[36] This group was known as the Foreign Protestants. This effort proved successful and today the South Shore region of Nova Scotia is still largely Lutheran. After the Expulsion of the Acadians beginning in 1755 a large number of New England Planters settled on the vacated lands bringing with them their Congregationalist belief.[37] During the 1770s, guided by Henry Alline, the New Light movement of the Great Awakening swept through the Atlantic region converting many of the Congregationalists to the new theology.[38] After Alline's death many of these Newlights eventually became Baptists, thus making Maritime Canada the heartland of the Baptist movement in Canada.[39][40][41]

The Quebec Act of 1774 acknowledged the rights of the Roman Catholic Church throughout Lower Canada in order to keep the French Canadians loyal to Britannic Crown.[42] Roman Catholicism is still the main religion of French Canadians today.

The American Revolution beginning in 1765 brought a large influx of Protestants to Canada when United Empire Loyalists, fleeing the rebellious United States, moved in large numbers to Upper Canada and the Maritimes.[43] They comprised a mix of Christian groups with a large number of Anglicans, but also many Presbyterians and Methodists.

1800s to 1900s

While Anglicans consolidated their hold on the upper classes, workingmen and farmers responded to the Methodist revivals, often sponsored by visiting preachers from the United States. Typical was Rev. James Caughey, an American sent by the Wesleyan Methodist Church from the 1840s through 1864. He brought in the converts by the score, most notably in the revivals in Western Canada from 1851 to 1853. His technique combined restrained emotionalism with a clear call for personal commitment, coupled with follow-up action to organize support from converts. It was a time when the holiness movement caught fire, with the revitalized interest of men and women in Christian perfection. Caughey successfully bridged the gap between the style of earlier camp meetings and the needs of more sophisticated Methodist congregations in the emerging cities.[44]

In the early nineteenth century in the Maritimes and Upper Canada, the Anglican Church held the same official position it did in England. This caused tension within English Canada, as much of the populace was not Anglican. Increasing immigration from Scotland created a very large Presbyterian community and they and other groups demanded equal rights. This was an important cause of the 1837 Rebellion in Upper Canada. With the arrival of responsible governments, the Anglican monopoly was ended.[45]

In Lower Canada, the Roman Catholic Church was officially pre-eminent and had a central role in the colony's culture and politics. Unlike English Canada, French Canadian nationalism became very closely associated with Roman Catholicism.[46] During this period, the Roman Catholic Church in the region became one of the most reactionary in the world. Known as Ultramontane Catholicism, the church adopted positions condemning all manifestations of liberalism.[47]

In politics, those aligned with the Roman Catholic clergy in Quebec were known as les bleus (the blues). They formed a curious alliance with the staunchly monarchist and pro-British Anglicans of English Canada (often members of the Orange Order) to form the basis of the Canadian Conservative Party. The Reform Party, which later became the Liberal Party, was largely composed of the anti-clerical French Canadians, known as les rouges (the reds) and the non-Anglican Protestant groups. In those times, right before elections, parish priests would give sermons to their flock where they said things like Le ciel est bleu et l'enfer est rouge. This translates as "Heaven/the sky is blue and hell is red".

By the late nineteenth century, Protestant pluralism had taken hold in English Canada. While much of the elite were still Anglican, other groups had become very prominent as well. Toronto had become home to the world's single largest Methodist community and it became known as the "Methodist Rome". The schools and universities created at this time reflected this pluralism with major centres of learning being established for each faith. One, King's College, later the University of Toronto, was set up as a non-denominational school. The influence of the Orange Order was strong, especially among Irish Protestant immigrants, and comprised a powerful anti-Catholic force in Ontario politics; its influence faded away after 1920.[48]

The late nineteenth century also saw the beginning of a large shift in Canadian immigration patterns. Large numbers of Irish and Southern European immigrants were creating new Roman Catholic communities in English Canada. Western Canada saw the arrival of significant Eastern Orthodox immigrants from Eastern Europe as well as Mormon and Pentecostal immigrants from the United States and Ireland.

1900s to 1960s

In 1919-20 Canada's five major Protestant denominations (Anglican, Baptist, Congregational, Methodist, and Presbyterian) cooperatively undertook the "Forward Movement." The goal was to raise funds and to strengthen Christian spirituality in Canada. The movement invoked Anglophone nationalism by linking donations with the Victory Loan campaigns of the First World War, and stressed the need for funds to Canadianize immigrants. Centred in Ontario, the campaign was a clear financial success, raising over $11 million. However the campaign exposed deep divisions among Protestants, with the traditional Evangelists speaking of a personal relationship with God and the more liberal denominations emphasizing the Social Gospel and good works.[49] Both factions (apart from the Anglicans) agreed on prohibition, which was demanded by the WCTU.[50]

Domination of Canadian society by Protestant and Roman Catholic elements continued until well into the 20th century. Until the 1960s, most parts of Canada still had extensive Lord's Day laws that limited what one could do on a Sunday.[51] The English Canadian elite were still dominated by Protestants, and Jews and Roman Catholics were often excluded.[52] A slow process of liberalization began after the Second World War in English Canada. Overtly Christian laws were expunged, including those against homosexuality. Policies favouring Christian immigration were also abolished.[53]

1960s and after

The most overwhelming change occurred during the Quiet Revolution in Quebec in the 1960s. Up to the 1950s, the province was one of the most traditional Roman Catholic areas in the world. Church attendance rates were high, and the schools were largely controlled by the Church. In the 1960s, the Catholic Church lost most of its influence in Quebec, and religiosity declined sharply.[54] While the majority of Québécois are still professed Latin rite Roman Catholics, rates of church attendance have decreased dramatically.[55] Since then, Common law relationships, abortion, and support for same-sex marriage are more common in Quebec than in the rest of Canada.

English Canada also underwent secularization. The United Church of Canada, the country's largest Protestant denomination, became one of the most liberal major Protestant churches in the world. Flatt argues that in the 1960s Canada's rapid cultural changes led the United Church to end its evangelical programs and change its identity. It made revolutionary changes in its evangelistic campaigns, educational programs, moral stances, and theological image. However, membership declined sharply as the United Church affirmed a commitment to gay rights including marriage and ordination, and to the ordination of women.[56][57]

Meanwhile, a strong current of evangelical Protestantism emerged. The largest groups are found in the Atlantic provinces and Western Canada, particularly in Alberta, Southern Manitoba and the Southern interior and Fraser Valley region of British Columbia, also known as the "Canadian Bible Belt", as well as parts of Ontario outside the Greater Toronto Area. The social environment is more conservative, somewhat more in line with that of the Midwestern and Southern United States, and same-sex marriage, abortion, and common-law relationships are less widely accepted. This movement has grown sharply after 1960. The evangelicals increasingly influence public policy. Nevertheless, the overall proportion of evangelicals in Canada remains considerably lower than in the United States and the polarization much less intense. There are very few evangelicals in Quebec and in the largest urban areas, which are generally secular, although there are several congregations above 1000 members in most large cities.[58]

Abrahamic religions

Bahá'í Faith

The Canadian community is one of the earliest western communities of Bahá'ís, at one point sharing a joint National Spiritual Assembly with the United States, and is a co-recipient of `Abdu'l-Bahá's Tablets of the Divine Plan. The first North American woman to declare herself a Bahá'í was Kate C. Ives, of Canadian ancestry, though not living in Canada at the time. Moojan Momen, in reviewing "The Origins of the Bahá'í Community of Canada, 1898–1948" notes that "the Magee family... are credited with bringing the Bahá'í Faith to Canada. Edith Magee became a Bahá'í in 1898 in Chicago and returned to her home in London, Ontario, where four other female members of her family became Bahá'ís. This predominance of women converts became a feature of the Canadian Bahá'í community..."[59]

Christianity

| Christian denominations in Canada |

|---|

|

The majority of Canadian Christians attend church services infrequently. Cross-national surveys of religiosity rates such as the Pew Global Attitudes Project indicate that, on average, Canadian Christians are less observant than those of the United States but are still more overtly religious than their counterparts in Western Europe. In 2002, 30% of Canadians reported to Pew researchers that religion was "very important" to them. A 2005 Gallup poll showed that 28% of Canadians consider religion to be "very important" (55% of Americans and 19% of Britons say the same).[60] Regional differences within Canada exist, however, with British Columbia and Quebec reporting especially low metrics of traditional religious observance, as well as a significant urban-rural divide, while Alberta and rural Ontario saw high rates of religious attendance. The rates for weekly church attendance are contested, with estimates running as low as 11% as per the latest Ipsos-Reid poll and as high as 25% as per Christianity Today magazine. This American magazine reported that three polls conducted by Focus on the Family, Time Canada and the Vanier Institute of the Family showed church attendance increasing for the first time in a generation, with weekly attendance at 25 per cent. This number is similar to the statistics reported by premier Canadian sociologist of religion, Prof. Reginald Bibby of the University of Lethbridge, who has been studying Canadian religious patterns since 1975. Although lower than in the US, which has reported weekly church attendance at about 40% since the Second World War, weekly church attendance rates are higher than those in Northern Europe.

As well as the large churches — Roman Catholic, United, and Anglican, which together count more than half of the Canadian population as nominal adherents — Canada also has many smaller Christian groups, including Orthodox Christianity. The Egyptian population in Ontario and Quebec (Greater Toronto in particular) has seen a large influx of the Coptic Orthodox population in just a few decades. The relatively large Ukrainian population of Manitoba and Saskatchewan has produced many followers of the Ukrainian Catholic and Ukrainian Orthodox Churches, while southern Manitoba has been settled largely by Mennonites. The concentration of these smaller groups often varies greatly across the country. Baptists are especially numerous in the Maritimes. The Maritimes, prairie provinces, and southwestern Ontario have significant numbers of Lutherans. Southwest Ontario has seen large numbers of German and Russian immigrants, including many Mennonites and Hutterites, as well as a significant contingent of Dutch Reformed. Alberta has seen considerable immigration from the American plains, creating a significant Mormon minority in that province. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints claimed to have 178,102 members (74,377 of whom in Alberta) at the end of 2007.[61] And according to the Jehovah's Witnesses year report there are 111,963 active members (members who actively preach) in Canada.

Canada as a nation is becoming increasingly religiously diverse, especially in large urban centres such as Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal, where minority groups and new immigrants who make up the growth in most religious groups congregate. Two significant trends become clear when we examine the current religious landscape closely. One is the loss of ‘secularized' Canadians as active and regular participants in the churches and denominations they grew up in, which were overwhelmingly Christian, while these churches remain a part of Canadians cultural identity. The other is the increasing presence of ethnically diverse immigration within the religious makeup of the country.

As Mainline Protestants and Roman Catholics have experienced drastic losses over the past 30 years, others have been expanding rapidly: overall by 144% in ‘Eastern' religions during the 1981-1991 decade.[62] Considering Canada's increasing reliance on immigration to bolster a low birth rate, the situation is only likely to continue to diversify. This increased influx of ethnic immigrants not only affects the types of religions represented in the Canadian context but also the increasingly multicultural and multilingual makeup of individual Christian denominations. From Chinese Anglican or Korean United Church communities, to the Lutheran focus on providing much needed services to immigrants new to the Canadian context and English language, immigration is making changes.[63]

For some Protestant denominations, adapting to a new secular context has meant adjusting to their non-institutional roles in society by increasingly focusing on social justice.[64] However the pull between conservative religious members and the more radical among the church members is complicated by the numbers of immigrant communities who may desire a church that fulfills a more ‘institutionally complete' role as a buffer in this new country over the current tension filled debates over same-sex marriage, ordination of women and homosexuals, or the role of women in the church. This of course will depend on the background of the immigrant population, as in the Hong Kong context where ordination of Florence Li Tim Oi happened long before women's ordination was ever raised on the Canadian Anglican church level.[65]

As well a multicultural focus on the churches part may include non-Christian elements (such as the inclusion of a Buddhist priest in one incident) which are unwelcome to the transplanted religious community.[66] Serving the needs and desires of different aspects of the Canadian and newly Canadian populations makes a difficult balancing act for the various mainline churches which are starved for money and active parishioners in a time where 16% of Canadians identify as non-religious and up to two-thirds of those who do identify with a denomination use the church only for its life-cycle rituals governing birth, marriage, and death.[67] The church retains that hold in their parishioner's lives but not the commitment of time and energy necessary to support an aging institution.

Evangelical portions of the Protestant groups proclaim their growth as well but as Roger O'Tool notes they make up 7% of the Canadian population and seem to gain most of their growth from a higher birthrate.[68] What is significant is the higher participation of their members in contrast to Mainline Protestants and Roman Catholics. This high commitment would seem to translate into the kind of political power evangelicals in the United States enjoy but despite Canada's historically Christian background as Lori Beaman notes neatly "...[forming] the backdrop for social process"[69] explicit religiosity appears to have not effectively moved the government towards legal discrimination against gay marriage. Much as many Roman Catholics in Quebec ignore the Church's stance on birth control, abortion, or premarital sex, the churches do not dictate much of the daily lives of regular Canadians.[70]

A 2015 study estimates some 43,000 believers in Christ from a Muslim background in Canada, most of whom belong to the evangelical tradition.[71]

| Province/Territory |

Christians[72] |

|---|---|

| 93.19% | |

| 85.99% | |

| 84.16% | |

| 83.84% | |

| 82.27% | |

| 78.19% | |

| 72.06% | |

| 66.30% | |

| 68.43% | |

| 67.3% | |

| 64.55% | |

| 60.32% | |

| 46.16% | |

| 44.64% |

Anabaptism

Hutterites

In mid-1870s Hutterites moved from Europe to the Dakota Territory in the United States to avoid military service and other persecutions.[73] During World War I Hutterites suffered from persecutions in the United States because they are pacifist and refused military service.[74][75] They then moved almost all of their communities to Canada in the Western provinces of Alberta and Manitoba in 1918.[75] In the 1940s, there were 52 Hutterite colonies in Canada.[75]

Today, more than 75% of the world's Hutterite colonies are located in Canada, mainly in Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, the rest being almost exclusively in the United States.[76] The Hutterite population in North America is about 45,000 people.[77]

Mennonites

First Mennonites arrived in Canada in 1786 from Pennsylvania, but following Mennonites arrived directly from Europe.[78] The Mennonite Church Canada had about 35,000 members in 1998.[79]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) has had a presence in Canada since its organization in New York State in 1830.[80] Canada has been used as a refuge territory by members of the LDS Church to avoid the anti-polygamy prosecutions by the United States government.[81] The first LDS Church in Canada has been established in 1895 in what will become Alberta; it was the first stake of the Church to be established outside the United States.[82] The LDS Church has founded several communities in Alberta.

In 2011, the LDS Church of Canada claimed around 200,000 members; the 2011 Canadian National Household Survey calculates around 100,000.[83] It has congregations in all Canadian provinces and territories and possess at least one temple in six of the ten provinces, including the oldest LDS temple outside the United States. Alberta is the province with the most members of the LDS Church in Canada, having approximately 40% of the total of Canadian LDS Church members and representing 2% of the total population of the province (the National Household survey has Alberta with over 50% of the Canadian Mormons and 1.6% of the province's population[83]), followed by Ontario and British Columbia.[84]

Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church in Canada, under the spiritual leadership of the Pope and the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, has the largest number of adherents to a religion in Canada, with 38.7% of Canadians (13.07 million) baptized as Catholics, in 72 dioceses across the provinces and territories, served by about 8,000 priests. It was the first European faith in what is now Canada, arriving in 1497 when John Cabot landed on Newfoundland and raised the Venetian and Papal banners, claiming the land for his sponsor King Henry VII of England, while recognizing the religious authority of the Roman Catholic Church.[85]

Islam

Four years after Canada's founding in 1867, the 1871 Canadian Census found 13 Muslims among the population.[86] Today, Islam is the second largest religion in Canada, practised by 3.2% of the total population.[3] The first Canadian mosque was constructed in Edmonton in 1938, when there were approximately 700 Muslims in the country.[87] This building is now part of the museum at Fort Edmonton Park. The years after World War II saw a small increase in the Muslim population. However, Muslims were still a distinct minority. It was only with the removal of European immigration preferences in the late 1960s that Muslims began to arrive in significant numbers.

According to Canada's 2001 census, there were 579,740 Muslims in Canada, just under 2% of the population.[88] In 2006, the Muslim population was estimated to be 0.8 million or about 2.6%. In 2010, the Pew Research Centre estimates there were about 0.9 million Muslims in Canada.[89] About 65% were Sunni, while 15% were Shia.[dead link][90] Some Muslims are non-practicing.[citation needed] In the 2011 National Housing Survey, Muslims constituted 3.2% of the population[91][92] making them largest religious adherents after Christianity. Islam is the fastest growing religion in Canada.[91] Sunni Islam is followed by the majority while there are significant Shia Muslims. Ahmadiyya also has a significant proportion with more than 25,000 Ahmadis are living in Canada.[93] There are also non-denominational Muslims[94]

In 2007, the CBC introduced a popular television sitcom called Little Mosque on the Prairie, a contemporary reflection and critical commentary on attitudes towards Islam in Canada.[95] In 2008, the Prime Minister of Canada, Stephen Harper, visited the Baitun Nur Mosque, the largest mosque in Canada for its inaugural session with the Head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.[96]

| Province/Territory |

Muslims |

|---|---|

| 3.1% | |

| 1.9% | |

| 1.6% | |

| 1.5% | |

| 1.4% | |

| 0.4% | |

| 0.4% | |

| 0.3% | |

| 0.2% | |

| 0.2% | |

| 0.1% | |

| 0.1% | |

| 0.1% | |

| 0.1% |

Judaism

The Jewish community in Canada is almost as old as the nation itself. The earliest documentation of Jews in Canada are British Army records from the French and Indian War from 1754. In 1760, General Jeffrey Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst attacked and won Montreal for the British. In his regiment there were several Jews, including four among his officer corps, most notably Lieutenant Aaron Hart who is considered the father of Canadian Jewry.[97] In 1807, Ezekiel Hart was elected to the legislature of Lower Canada, becoming the first Jew in the British Empire to hold an official position. Hart was sworn in on a Hebrew Bible as opposed to a Christian Bible.[98][99] The next day an objection was raised that Hart had not taken the oath in the manner required for sitting in the assembly — an oath of abjuration, which would have required Hart to swear "on the true faith of a Christian".[100] Hart was expelled from the assembly, only to be re-elected two more times. In 1768, the first synagogue in Canada was built in Montreal, the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue of Montreal. In 1832, partly because of the work of Ezekiel Hart, a law was passed that guaranteed Jews the same political rights and freedoms as Christians.

The Jewish population saw a growth during the 1880s due to the pogroms of Russia and growing anti-Semitism. Between the years of 1880 and 1930 the Jewish population grew to 155,000. In 1872, Henry Nathan, Jr. became the first Jewish Member of Parliament, representing the Victoria, BC area in the newly created House of Commons. The First World War halted the flow of immigrants into Canada, and after the War there was a change in Canada's immigration policy to limit the immigration of people from "non-preferred nations", i.e., those not from the United Kingdom or otherwise White Anglo-Saxon Protestant nations. In June 1939 Canada and the United States were the last hope for 907 Jewish refugees aboard the steamship SS St. Louis which had been denied to land in Havana although the passengers had entry visas. The Canadian government ignored the protests of Canadian Jewish organizations. King said the crisis was not a "Canadian problem" and Blair added in a letter to O.D. Skelton, Undersecretary of State for External Affairs, dated June 16, 1939, "No country could open its doors wide enough to take in the hundreds of thousands of Jewish people who want to leave Europe: the line must be drawn somewhere." The ship finally had to return to Germany.[101] During the Second World War almost twenty thousand Canadian Jews volunteered to fight overseas. Nearly 40,000 Holocaust survivors moved to Canada in the late 1940s to rebuild their lives.

Today the Canadian Jewish community is the fourth largest in the world[102] and practices in both of the official languages of Canada. There is an increase in the number of people that use Hebrew, other than religious ceremonies, while there is a decline in the Yiddish language. Most of Canada's Jews live in Ontario and Quebec, with Toronto having the largest Jewish population centre. Recently, anti-Semitism has been a growing concern in Canada. In 2009, anti-Semitic incidents jumped a fivefold,[103] with over 113 incidents, and some reports listing 479 in Toronto alone.[citation needed]

| Province/Territory |

Jews [104] |

|---|---|

| 1.7% | |

| 1.3% | |

| 1.2% | |

| 1.1% | |

| 0.5% | |

| 0.4% | |

| 0.2% | |

| 0.1% | |

| 0.09% | |

| 0.09% | |

| 0.07% | |

| 0.04% | |

| 0.03% | |

| 0.0% |

Indian religions

Hinduism

Hindus in Canada generally come from one of four groups. The first is primarily made up of Indian immigrants who began arriving in British Columbia about 100 years ago and continue to immigrate today (Hindus from all over India immigrate to Canada today, but the largest Indian subgroups are the Gujaratis and Punjabis). The second major group of Hindus immigrated from Sri Lanka, going back to the 1940s, when a few hundred Sri Lankan Tamils migrated to Canada. The 1983 communal riots in Sri Lanka precipitated the mass exodus of Tamils. A third group is made up of Canadian converts to the various sects of Hinduism through the efforts of the Hare Krishna movement, the Gurus during the last 50 years, and other organizations. Finally, the small Nepalese Canadian community is mostly Hindu.

According to the 2001 Census of Canada, there were 297,200 practitioners of Hinduism.[105] However, the non-profit organization Association for Canadian Studies estimates the Hindu population grew to 372,500 by 2006, or just under 1.2% of the population of Canada. The vast majority of Hindus reside in Ontario (primarily in Toronto, Scarborough, Brampton, Hamilton, Windsor & Ottawa), Quebec (primarily around the Montreal area) & British Columbia, (primarily around the Vancouver area).[105]

| Province | Hindus population[106] |

|---|---|

| 217,555 | |

| 31,500 | |

| 24,525 | |

| 15,965 | |

| 3,835 | |

| 1,585 | |

| 1,235 | |

| 475 | |

| 405 | |

| 65 | |

| 30 | |

| 10 | |

| 1 | |

| 297,200 |

Buddhism

There is a small, rapidly growing Buddhist community in Canada. At the 2001 census, 300,346 Canadians identified their religion as Buddhist, about 1% of the country's population.[106]

Buddhism has been practiced in Canada for more than a century and in recent years has grown dramatically. Buddhism arrived in Canada with the arrival of Chinese laborers in the territories during the 19th century.[107] Modern Buddhism in Canada traces to Japanese immigration during the late 19th century.[107] The first Japanese Buddhist temple in Canada was built at the Ishikawa Hotel in Vancouver in 1905.[108] Over time, the Japanese Jōdo Shinshū branch of Buddhism became the prevalent form of Buddhism in Canada[107] and established the largest Buddhist organization in Canada.[107]

| Province | Buddhists population[106] |

|---|---|

| 128,321 | |

| 85,540 | |

| 41,380 | |

| 33,410 | |

| 5,745 | |

| 3,050 | |

| 1,730 | |

| 545 | |

| 185 | |

| 155 | |

| 140 | |

| 130 | |

| 15 | |

| 300,346 |

Jainism

The first official Jain temple was established in Toronto in 1988.[109] This temple served both the Digambar and Svetambara communities.[110]

Sikhism

Sikhs are the largest religious group among Indo-Canadians.[111] According to the 2001 census there are 278,410 Sikhs in Canada.[106] Sikhs have been in Canada since at least 1887.[citation needed]

| Province | Sikhs population[106] |

|---|---|

| 135,310 | |

| 108,785 | |

| 23,470 | |

| 8,225 | |

| 5,485 | |

| 500 | |

| 270 | |

| 135 | |

| 100 | |

| 90 | |

| 45 | |

| 1 | |

| 0 | |

| 278,410 |

Other religions

Neopaganism

Census data showed Neopaganism grew by 281 per cent between 1991 and 2001, making it the fastest growing religion in Canada during that decade.[112]

Neo-Druidism

In Neo-Druid history a notable community was the Reformed Druids of North America, one of whose four founders was Canadian, which served both the US Druid community and the Canadian Druid community. Neo-Druidism largely spread in Canada through the Ancient Order of the Druids during the 19th century.[113]

Irreligion

Irreligious Canadians include atheists, agnostics, and humanists. The surveys may also include those who are spiritual, deists, and pantheists. In 1991 they made up 12.3% of the Canadian population. In the 2001 census this number increased to 16.2% and increased again in 2011 to 23.9%.[114] Some non-religious Canadians have formed associations, such as the Humanist Association of Canada, Toronto Secular Alliance or the Centre for Inquiry Canada, as well as a number of University Campus Groups.

| Rank | Jurisdiction | % Irreligious (2001) | % Irreligious (2011) | Change (2001-2011) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | 16.2% | 23.9% | +7.7 | |

| 01 | 37.4% | 49.9% | +12.5 | |

| 02 | 35.1% | 44.1% | +9.0 | |

| 03 | 23.1% | 31.6% | +8.5 | |

| 04 | 17.4% | 30.5% | +13.1 | |

| 05 | 18.3% | 26.5% | +8.2 | |

| 06 | 15.4% | 24.4% | +9.0 | |

| 07 | 16.0% | 23.1% | +7.1 | |

| 08 | 11.6% | 21.8% | +10.2 | |

| 09 | 7.8% | 15.1% | +7.3 | |

| 10 | 6.5% | 14.4% | +7.9 | |

| 11 | 6.0% | 13.0% | +7.0 | |

| 12 | 5.6% | 12.1% | +6.5 | |

| 13 | 2.5% | 6.2% | +3.7 |

Age and religion

According to the 2001 census, the major religions in Canada have the following median age. Canada has a median age of 37.3.[115]

- Presbyterian 46.1

- United Church 44.1

- Anglican 43.8

- Lutheran 43.3

- Jewish 41.5

- Greek Orthodox 40.7

- Baptist 39.3

- Buddhist 38.0

- Roman Catholic 37.8

- Pentecostal 33.5

- No Religion 31.9

- Hindu 30.2

- Sikh 29.7

- Muslim 28.1

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Religions in Canada—Census 2011". Statistics Canada/Statistique Canada.

- ^ Dianne R. Hales; Lara Lauzon (2009). An Invitation to Health. Cengage Learning. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-17-650009-2.

- ^ a b "The Daily — 2011 National Household Survey: Immigration, place of birth, citizenship, ethnic origin, visible minorities, language and religion". Statistics Canada.

- ^ "Canada". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton; Martin Baumann (2010). Religions of the World, Second Edition: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. p. 493. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3.

- ^ "Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982)". Department of Justice Canada. 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ Gary Miedema (2005). For Canada's Sake: Public Religion, Centennial Celebrations, and the Re-making of Canada in the 1960s. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7735-2877-2.

- ^ Native North American Religious Traditions: Dancing for Life - Page 5, Jordan D. Paper - 2007

- ^ Lance W. Roberts (2005). Recent Social Trends in Canada, 1960-2000. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-7735-2955-7.

- ^ Paul Bramadat; David Seljak (2009). Religion and Ethnicity in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4426-1018-7.

- ^ Kurt Bowen (2004). Christians in a Secular World: The Canadian Experience. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-7735-7194-5.

- ^ Derek Gregory; Ron Johnston; Geraldine Pratt; Michael Watts; Sarah Whatmore (2009). The Dictionary of Human Geography. John Wiley & Sons. p. 672. ISBN 978-1-4443-1056-6.

- ^ Betty Jane Punnett (2015). International Perspectives on Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-317-46745-8.

- ^ Dr. David M. Haskell (Wilfrid Laurier University) (2009). Through a Lens Darkly: How the News Media Perceive and Portray Evangelicals. Clements Publishing Group. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-894667-92-0.

- ^ Kevin Boyle; Juliet Sheen (2013). Freedom of Religion and Belief: A World Report. University of Essex - Routledge. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-134-72229-7.

- ^ Richard Moon (2008). Law and Religious Pluralism in Canada. UBC Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-0-7748-1497-3.

- ^ Religion as a Category of Governance and Sovereignty. BRILL. May 27, 2015. pp. 284–. ISBN 978-90-04-29059-4.

- ^ Philip Resnick (2012). The Labyrinth of North American Identities. University of Toronto Press. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-1-4426-0552-7.

- ^ Lance W. Roberts; Rodney A. Clifton; Barry Ferguson (2005). Recent Social Trends in Canada, 1960-2000. McGill-Queens. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-7735-2955-7.

- ^ Marguerite Van Die (2001). Religion and Public Life in Canada: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. University of Toronto Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-8020-8245-9.

- ^ Anne F. Bayefsky; Arieh Waldman (2007). State Support Of Religious Education: Canada Versus the United Nations. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-90-04-14980-9.

- ^ "U.K. Royal Succession Rules To Change". Huffington Post. October 28, 2011.

- ^ Robert A. Battram (2010). Canada In Crisis...: An Agenda to Unify the Nation. Trafford Publishing. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-4269-8062-6.

- ^ Kevin Boyle (1997). Freedom of Religion and Belief: A World Report. Taylor & Francis. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-415-15978-4.

- ^ Erwin Fahlbusch; Geoffrey William Bromiley (1999). The Encyclopedia of Christianity: E-I. Volume 2. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 501. ISBN 978-90-04-11695-5.

- ^ "Summary Tables". 0.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ "96F0030XIE2001015 - Religions in Canada". 2.statcan.ca. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ "Christian religious data from Canada". Religioustolerance.org. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ "96F0030XIE2001015 - Religions in Canada". 2.statcan.ca. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ^ "Religions in Canada—Census 2011". Statistics Canada/Statistique Canada.

- ^ Other religions, Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2014-04-24

- ^ James Rodger Miller (2000). Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: A History of Indian-white Relations in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8020-8153-7.

- ^ Elizabeth Tooker (1979). Native North American spirituality of the eastern woodlands: sacred myths, dreams, visions, speeches, healing formulas, rituals, and ceremonials. Paulist Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8091-2256-1.

- ^ Thomas Guthrie Marquis (1935). The Jesuit Missions: A Chronicle of the Cross in the Wilderness. Hayes Barton Press. pp. 7–13. ISBN 978-1-59377-530-8.

- ^ Roderick MacLeod; Mary Anne Poutanen (2004). Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801B1998. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7735-7183-9.

- ^ Will Kaufman; Heidi Slettedahl Macpherson (2005). Britain And The Americas: Culture, Politics, And History: A Multidesciplinary Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-85109-431-8.

- ^ Terrence Murphy; Roberto Perin (1996). A concise history of Christianity in Canada. Oxford University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-19-540758-7.

- ^ Daniel Vickers (2008). A Companion to Colonial America. John Wiley & Sons. p. 503. ISBN 978-0-470-99848-9.

- ^ Beverley, James and Barry Moody, Editors. The Journal of Henry Alline. Lancelot Press for the Acadia Divinity School and the Baptist Historical Committee. 1982.

- ^ Bumsted, J. M. Henry Alline. Lancelot Press, Hantsport, 1984.

- ^ Rawlyk, George. The Sermons of Henry Alline. Lancelot Press for Acadia Divinity College and The Baptist Historical Committee of the United Baptist Convention of the Atlantic Provinces. 1986.

- ^ Charles H Lippy; Peter W Williams (2010). Encyclopedia of Religion in America. Vol. 4. Granite Hill Publishers. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-87289-580-5.

- ^ Oxford University Press (2010). Protestantism: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide. Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-980853-3.

- ^ Peter Bush, "The Reverend James Caughey and Wesleyan Methodist Revivalism in Canada West, 1851-1856," Ontario History, Sept 1987, Vol. 79 Issue 3, pp 231-250

- ^ Charles H.H. Scobie; George A. Rawlyk (1997). Contribution of Presbyterianism to the Maritime Provinces of Canada. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. (page(s) needed). ISBN 978-0-7735-1600-7.

- ^ "Canada". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Retrieved December 12, 2011. See drop-down essay on "Early European Settlement and the Formation of the Modern State"

- ^ Raymond J. Lahey (2002). The First Thousand Years: A Brief History of the Catholic Church in Canada. Novalis Publishing. ISBN 978-2-89507-235-5.

- ^ Cecil J. Houston; William J. Smyth (1980). The sash Canada wore: a historical geography of the Orange Order in Canada. University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Daryl Baswick, "Social Evangelism, the Canadian Churches, and the Forward Movement, 1919-1920," Ontario History vol 12#1 1997, pp 303-319

- ^ Sharon Anne Cook, "'Earnest Christian Women, Bent on Saving our Canadian Youth': The Ontario Woman's Christian Temperance Union and Scientific Temperance Instruction, 1881-1930," Ontario History, Sept 1994, Vol. 86 Issue 3, pp 249-267

- ^ Alvin J. Schmidt (2009). How Christianity Changed the World. Zondervan. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-310-86250-5.

- ^ Kari Levitt (2002). Silent Surrender: The Multinational Corporation in Canada. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-7735-2311-1.

- ^ Richard Moon (2008). Law and Religious Pluralism in Canada. UBC Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-7748-5853-3.

- ^ "Canada". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Retrieved December 12, 2011. See drop-down essay on "History Since 1960"

- ^ Robin Gill (2003). The Empty Church Revisited. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-7546-3463-8.

- ^ Earle E. Cairns (1996). Christianity Through the Centuries: A History of the Christian Church. Zondervan Pub. p. 507. ISBN 978-0-310-20812-9.

- ^ Kevin N. Flatt, After Evangelicalism: The Sixties and the United Church of Canada (2013)

- ^ George A. Rawlyk (1997). Aspects of the Canadian Evangelical Experience. McGill-Queen's Press. p. passim. ISBN 978-0-7735-1547-5.

- ^ "Origins of the Baha'i Community of Canada 1898-1948, The, by Will C. van den Hoonaard". Bahai-library.com. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ "Can a "Reagan Revolution" Happen in Canada?". Gallup.com. January 20, 2006. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ^ Alberta. LDS Newsroom.

- ^ Roger O'Toole, "Religion in Canada: Its Development and Contemporary Situation" In Lori Beaman, ed., Religion and Canadian Society: Traditions, Transitions, and Innovations. (Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press, 2006), 18.

- ^ Paul A. Bramadat; David Seljak (2008). Christianity and Ethnicity in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-8020-9584-8.

- ^ Roger O'Toole, "Religion in Canada: Its Development and Contemporary Situation" In Lori Beaman, ed., Religion and Canadian Society: Traditions, Transitions, and Innovations. (Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press, 2006), 13-14.

- ^ Wendy Fletcher, "Canadian Anglicanism and Ethnicity" In P. Bramadat & D. Seljak, Christianity and Ethnicity in Canada. (Toronto: Pearson Longman, 2005.), 156.

- ^ Greer Anne Wenh-In Ng, "The United Church of Canada: A Church Fittingly National" In P. Bramadat & D. Seljak, Christianity and Ethnicity in Canada. (Toronto: Pearson Longman, 2005), 232.

- ^ "96F0030XIE2001015 - Religions in Canada". 2.statcan.ca. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ^ Roger O'Toole, "Religion in Canada: Its Development and Contemporary Situation" In Lori Beaman, ed., Religion and Canadian Society: Traditions, Transitions, and Innovations. (Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press, 2006), 17.

- ^ Lori Beaman, ed., Religion and Canadian Society: Traditions, Transitions, and Innovations. (Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press, 2006), 3.

- ^ Roger O'Toole, "Religion in Canada: Its Development and Contemporary Situation" In Lori Beaman, ed., Religion and Canadian Society: Traditions, Transitions, and Innovations. (Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press, 2006), 12.

- ^ Miller, Duane; Johnstone, Patrick (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11 (10). Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ "Religions in Canada—Census 2011". Statistics Canada/Statistique Canada.

- ^ Journey to America, Hutterian Brethren. Retrieved 2014-04-25

- ^ Smith, C. Henry (1981). Smith's Story of the Mennonites (Revised and expanded by Cornelius Krahn ed.). Newton, Kansas: Faith and Life Press. p. 545. ISBN 0-87303-069-9.

- ^ a b c World War 1, Hutterian Brethren. Retrieved 2014-04-25

- ^ A directory of Hutterite colonies. Retrieved on 2014-04-25

- ^ WW1 & Beyond, Hutterian Brethren. Retrieved 2014-04-25

- ^ National Council of Ch of Christ in USA (2012). Yearbook of American & Canadian Churches 2012. Abingdon Press. pp. 406–. ISBN 978-1-4267-5610-8.

- ^ Donald B. Kraybill (2010). Concise Encyclopedia of Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites. JHU Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8018-9911-9.

- ^ Brigham Young Card (1990). The Mormon Presence in Canada. University of Alberta. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-88864-212-7.

- ^ Paul Finkelman (2006). Encyclopedia of American Civil Liberties. Routledge. p. 1039. ISBN 978-1-135-94705-7.

- ^ Liz Bryan (2011). Country Roads of Alberta: Exploring the Routes Less Travelled. Heritage House. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-926613-02-4.

- ^ a b "2011 National Household Survey". Statistics Canada. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ^ Deseret News Church Almanac, 2011

- ^ P D'Epiro, M.D. Pinkowish, "Sprezzatura: 50 ways Italian genius shaped the world" pp. 179–180

- ^ 1871 Census of Canada

- ^ Saudi Aramco World: Canada's Pioneer Mosque: http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/199804/canada.s.pioneer.mosque.htm

- ^ "Population by religion, by province and territory (2001 Census)". 0.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ "World Muslim Population Data Tables - Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life". Features.pewforum.org. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ http://www.environicsinstitute.org/PDF-MuslimsandMulticulturalisminCanada-LiftingtheVeil.pdf -- Muslims and Multiculturalism in Canada. March 2007. Retrieved 2011-03-26. Archived 2012-01-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Muslims fastest growing religious population in Canada | National Post". News.nationalpost.com. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ "The Daily — 2011 National Household Survey: Immigration, place of birth, citizenship, ethnic origin, visible minorities, language and religion". Statcan.gc.ca. May 9, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ Don Baker, Daniel L. Overmyer, Larry DeVries (August 9, 2012). Asian Religions in British Columbia. UCB Press. p. 73. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pew Forum on Religious & Public life. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2013

- ^ "CBC Television - Little Mosque on the Prairie". Cbc.ca. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ^ Morton, Graeme (July 5, 2008). "Politicians and faithful open Canada's largest mosque". Canada.com. Canwest News Service. Retrieved July 12, 2008.

- ^ "Hart, Aaron". Exposition Shalom Québec. Retrieved March 25, 2009.

- ^ Brown, Michael (1986). The Beginning of Jewish Emancipation in Canada: The Hart Affair. Michael, vol. 10.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Bloch, Abraham P. (1987). One a Day: An Anthology of Jewish Historical Anniversaries for Every Day of the Year. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. p. 31. ISBN 0-88125-108-9.

- ^ Weinfeld, Morton; Shaffir, William; Cotler, Irwin (1981). The Canadian Jewish Mosaic. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 262, 385. ISBN 0-471-79929-7.

- ^ "The Virtual Jewish History Tour - Canada". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- ^ "JEWISH POPULATION IN THE WORLD AND IN ISRAEL" (PDF). CBS. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Keung, Nicholas (April 11, 2010). "Anti-semitism incidents jump five-fold in Canada". Toronto: thestar.com. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Statistics Canadawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Selected Religions, for Canada, Provinces and Territories - 20% Sample Data". Religions in Canada: Highlight Tables, 2001 Census. Statistics Canada. 2004. Retrieved May 23, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e "Population by religion, by province and territory (2001 Census)". 0.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c d A.W. Barber. "Buddhism". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ "A Journalist's Guide to Buddhism" (PDF). Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ McAteer, Michael (April 22, 1989). "Non-violence to any living thing". Toronto Star. p. M.23. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ Lambek 2002, p. 557

- ^ "Sikhism in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia

- ^ Todd, Douglas. "University of Victoria chaplain marks solstice with pagan rituals | Vancouver Sun". Blogs.vancouversun.com. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia - Volumes 1-5 - Page 1353, John T. Koch - 2006

- ^ "Religions in Canada—Census 2011". Statistics Canada/Statistique Canada.

- ^ "Religions in Canada". 2.statcan.ca. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

Further reading

- Lori G. Beaman (2006). Religion And Canadian Society: Traditions, Transitions, And Innovations. Canadian Scholars' Press. ISBN 978-1-55130-306-2.

- Lori Gail Beaman; Peter Beyer (2008). Religion and Diversity in Canada. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-17015-5.

- Paul Bramadat; David Seljak (2009). Religion and Ethnicity in Canada. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-1018-7.

- Paul A. Bramadat; David Seljak (2008). Christianity and Ethnicity in Canada. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9584-8.

- Robert Choquette (2004). Canada's Religions: An Historical Introduction. University of Ottawa Press. ISBN 978-0-7766-0557-9.

- Terence J. Fay (2002). History of Canadian Catholics. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-6988-1.

- Kevin N. Flatt. After Evangelicalism: The Sixties and the United Church of Canada (2013) excerpt and text search

- Paul Robert Magocsi (1999). Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-2938-6.

- William Bettridge (1838). A Brief History of the Church in Upper Canada: Containing the Acts of Parliament, Imperial and Provincial, Royal Instructions, Proceedings of the Deputation, Correspondence with the Government, Clergy Reserves' Question, &c. &c. W.E. Painter.

- Nancy Christie; Michael Gauvreau (2010). Christian Churches and Their Peoples, 1840-1965: A Social History of Religion in Canada. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-6001-4.

- Gary Miedema (2005). For Canada's Sake: Public Religion, Centennial Celebrations, and the Re-making of Canada in the 1960s. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2877-2.

- Richard Moon (2008). Law and Religious Pluralism in Canada. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-5853-3.

- Terrence Murphy; Roberto Perin (1996). A concise history of Christianity in Canada. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-540758-7.

- John G. Stackhouse, Jr. (1998). Canadian Evangelicalism in the Twentieth Century: An Introduction to Its Character. Regent College Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57383-131-4.

- Elam Rush Stimson (2008). History of the Separation of Church and State in Canada. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-0-559-67266-8.

- Frances Swyripa (2010). Storied Landscapes: Ethno-Religious Identity and the Canadian Prairies. Univ. of Manitoba Press. ISBN 978-0-88755-720-0.

- Marguerite Van Die (2001). Religion and Public Life in Canada: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8245-9.

- Douglas James Wilson (1966). The Church Grows in Canada. University of Wisconsin: Ryerson Press.

External links

- CBC Digital Archives - Religion in the Classroom

- Canada religious census 2001

- Canadian Church Reading Room, with extensive links to on-line resources on Christianity in Canada (Tyndale Seminary)

- Canada’s Demo-Religious Revolution: 2017