Romania in World War I

| Romanian Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Balkans Campaign (World War I) | |||||||

Romanian troops at Mărăşeşti battlefield in 1917. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown |

| ||||||

Template:FixBunching The Romanian Campaign was a campaign in the Balkan theatre of World War I, with Romania and Russia allied against the armies of the Central Powers.

Before the war

The Kingdom of Romania was ruled by kings of the House of Hohenzollern from 1866. The King of Romania, Carol I of Hohenzollern, had signed a secret treaty with the Triple Alliance in 1883 which stipulated that Romania would be obliged to go to war only in the event Austro-Hungarian Empire was attacked. While Carol wanted to enter the World War I as an ally of the Central Powers, the Romanian public and the political parties were in favor of joining the Triple Entente. Romania remained neutral when the war started, arguing that Austria-Hungary itself had started the war and, consequently, Romania was under no formal obligation to join it.

In order to enter the war on Allied side, the Kingdom of Romania demanded recognition of its rights over the territory of Transylvania, which had been controlled by Austria-Hungary since the 17th century, even though Romanians were a majority in Transylvania (see History of Transylvania). The Allies accepted the terms late in the summer of 1916 (see Treaty of Bucharest, 1916); if Romania had sided with the Allies earlier in the year, before the Brusilov Offensive, perhaps the Russian Empire, whom Romania distrusted for its occupation of Bessarabia would not have lost.[5] According to some American military historians, Russia delayed approval of Romanian demands out of worries about Romanian territorial designs on Bessarabia which was also inhabited by a Romanian majority.[6] According to British military historian John Keegan, before Romania entered the war the Allies had secretly agreed not to honour the territorial expansion of Romania when the war ended.[7]

In 1915 Lieutenant-Colonel Christopher Thompson, a fluent French speaker, was sent to Bucharest as British military attaché on Kitchener's initiative to bring Romania into the war. But when there he quickly formed the view that an unprepared and ill-armed Romania facing a war on two fronts against Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria would be a liability not an asset to the Allies. This view was brushed aside by Whitehall, and he signed a Military Convention with Romania on 13 August 1916 . By the end of 1916 he had to alleviate the consequences of Romania’s setbacks, and he supervised the destruction of the Romanian oil wells to deny them to Germany (later Thompson was a Labour peer and Secretary of State for Air).[8]

| History of Romania |

|---|

|

|

|

The Romanian government signed a treaty with the Allies on August 17, 1916 and declared war on the Central Powers on August 27. The Romanian Army was quite large, over 500,000 men in 23 divisions. However, it had officers with poor training and equipment; more than half of the army was barely trained. Meanwhile, the German Chief of Staff, General Erich von Falkenhayn correctly reasoned that Romania would side with the Allies and made plans to deal with Romania. Thanks to the earlier conquest of the Kingdom of Serbia and the ineffective Allied operations on the Kingdom of Greece border, and having a territorial interest in Dobrogea, the Bulgarian Army and the Ottoman Army were willing to help fight the Romanians.

The German high command was seriously worried about the prospect of Romania entering the war, Hindenburg writing:

It is certain that so relatively small a state as Rumania had never before been given a role so important, and, indeed, so decisive for the history of the world at so favorable a moment. Never before had two great Powers like Germany and Austria found themselves so much at the mercy of the military resources of a country which had scarcely one twentieth of the population of the two great states. Judging by the military situation, it was to be expected that Rumania had only to advance where she wished to decide the world war in favor of those Powers which had been hurling themselves at us in vain for years. Thus everything seemed to depend on whether Rumania was ready to make any sort of use of her momentary advantage.[9]

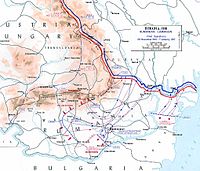

Kingdom of Romania enters the war, late August 1916

On the night of August 27, three Romanian armies (First, Second and Northern), deployed according to the Romanian Campaign Plan (The "Z" Hypothesis), launched attacks through the Carpathians and into Transylvania. The attacks were initially successful in pushing weak units of the Austro-Hungarian First Army out of the mountains. In a relatively short time, the towns of Braşov, Făgăraş and Miercurea Ciuc were freed and the outskirts of Sibiu were reached. Everywhere, the liberating Romanian troops were warmly welcomed by the population, which provided them considerable assistance in terms of provisions, billeting or guiding. But the Austro-Hungarians sent four divisions to reinforce their lines, and by the middle of September, the Romanian offensive was halted. The Russians loaned them three divisions for operations in the north of Romania, but otherwise very few supplies.

While the Romanian army was impetuosly advancing in Transylvania, the first counterattack came from General August von Mackensen in command of a multi-national army of Bulgarian divisions, a German brigade and the Ottoman VI Army Corps consisting of two divisions, whose units began arriving on the Dobrudja front after the initial battles.[10] This army attacked north from Bulgaria, starting on September 1. It stayed on the south side of the Danube river and headed towards Constanţa. The Romanian garrison of Turtucaia, encircled by Bulgarian troops (aided by a column of German troops) surrendered on September 6 (see: Battle of Turtucaia). The Romanian Third Army made further attempts to withstand the enemy offensive at Silistra, Bazargic, Amzacea and Topraisar, but had to withdraw under the pressure of superior enemy forces. Mackensen's success was favoured by the Allies' failure to fulfil the obligation they had assumed through the military convention, by virtue of which they had to mount an offensive on the Macedonian front, and the conditions in which the Russians deployed insufficient troops on the battlefront in the south-east of Romania.

On September 15, the Romanian War Council decided to suspend the Transylvania offensive and destroy the Mackensen army group instead. The Romanian Army had to fight on a 1,600 km-long battlefront, one of the longest fronts in Europe, with a varied configuration and diverse geographical elements, a situation that no other Allied army was faced with[citation needed]. The plan (the so-called Flămânda Maneuver) was to attack the Central Powers forces from the rear by crossing the Danube at Flămânda, while the front-line Romanian and Russian forces were supposed to launch an offensive southwards towards Cobadin and Kurtbunar. On October 1, two Romanian divisions crossed the Danube at Flămânda and created a bridgehead 14 kilometer-wide and 4 kilometer-deep. On the same day, the joint Romanian and Russian divisions went on offensive on the Dobruja front, however with little success. The failure to break the Dobruja front, combined with a heavy storm on the night of October 1/2 which caused heavy damages to the pontoon bridge, determined general Alexandru Averescu to cancel the whole operation. This would have serious consequences for the rest of the campaign.

Russian reinforcements under General Andrei Zaionchkovsky arrived to halt Mackensen's army before it cut the rail line that linked Constanţa with Bucharest. Fighting was furious with attacks and counterattacks up till September 23.

The counteroffensive of the Central Powers (September-December 1916)

Overall command was now under Falkenhayn (recently fired as German Chief of Staff) who started his own counterattack on September 18. The first attack was on the Romanian First Army near the town of Haţeg; the attack halted the Romanian army advance. Eight days later, two German divisions of mountain troops nearly cut off an advancing Romanian column near Nagyszeben (modern day Sibiu). Defeated, the Romanians retreated back into the mountains and the German troops captured Turnu Roşu Pass. On October 4, the Romanian Second Army attacked the Austro-Hungarians at Brassó (modern day Braşov) but the attack was repulsed and the counterattack forced the Romanians to retreat here also. The Fourth Romanian army, in the north of the country, retreated without much pressure from the Austro-Hungarian troops so that by October 25, the Romanian army was back to its borders everywhere.

Back on the coast, General Mackensen launched a new offensive on October 20, after a month of careful preparations, and his army defeated the Russian-Romanian troops under Zaionchkovsky's command. The Romanians and Russians were forced to withdraw out of Constanţa (occupied by the Central Powers on October 22). After the fall of Cernavodă, the defense of the unoccupied Dobruja was left only to the Russians, who were gradually pushed back towards the marshy Danube Delta. The Russian army was now both demoralized and nearly out of supplies. Mackensen felt free to secretly pull half his army back to the town of Svishtov (in Bulgaria) with an eye towards crossing the Danube river.

Falkenhayn's forces made several probing attacks into the mountain passes held by the Romanian army to see if there were weaknesses in the Romanian defences. After several weeks, he concentrated his best troops (the elite Alpen Korps) in the south for an attack on the Vulcan Pass. The attack was launched on November 10. One of the young officers was the future Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. On November 11, then-Lieutenant Rommel led the Württemberg Mountain Company in the capture of Mount Lescului. The offensive pushed the Romanian defenders back through the mountains and into the plains by November 26. There was already snow covering the mountains and soon operations would have to halt for the winter. Advances by other parts of Falkenhayn's Ninth army also pushed through the mountains; the Romanian army was being ground down by the constant battle and their supply situation was becoming critical.

On November 23, Mackensen's best troops crossed the Danube at two locations near Svishtov. This attack caught the Romanians by surprise and Mackensen's army was able to advance rapidly towards Bucharest against very weak resistance. Mackensen's attack threatened to cut off half the Romanian army and so the Romanian Supreme Commander (the recently promoted General Prezan) tried a desperate counter-attack on Mackensen's force. The plan was bold, using the entire reserves of the Romanian army, but it needed the cooperation of Russian divisions to contain Mackensen's offensive while the Romanian reserve struck the gap between Mackensen and Falkenhayn. However, the Russian Army disagreed with the plan and did not support the attack.

On December 1, the Romanian Army went ahead with the offensive. Mackensen was able to shift forces to deal with the sudden assault and Falkenhayn's forces responded with attacks at every point. Within three days, the attack had been shattered and the Romanians were retreating everywhere. The Romanian government and royal court relocated to Iaşi. Bucharest was captured on December 6 by Falkenhayn's cavalry. Rains and terrible roads were the only things that saved the remainder of the Romanian Army; more than 150,000 Romanian soldiers were captured.

The Russians were forced to send many divisions to the border area to prevent an invasion of southern Russia. The Austro-Hungarian Army, after several engagements, was fought to a standstill by the middle of January 1917. The Romanian Army still fought, but about half of Romania was under German occupation.

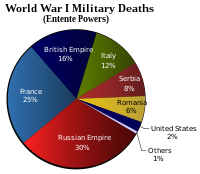

Romanian casualties are estimated at around 250,000 (including POWs)[citation needed]. German, Austrian, Bulgarian, and Ottoman losses are estimated at around 60,000.[citation needed]

The 1916 counteroffensive was an impressive feat for the German Army and their generals Falkenhayn and Mackensen[11] as well as the Bulgarian army[citation needed] commanded by Stefan Toshev,Panteley Kiselov and Todor Kantardzhiev.

The 1917 campaign

Fighting continued in 1917, as the northern part of Romania remained independent because of the triangle strategy, under which the Romanian Fourth Army (escaping destruction due to weather mentioned earlier), remained in the mountains in Moldavia, protecting Iaşi against repeated German offensives. In May 1917, the Romanian Army attacked alongside the Russians in support of the Kerensky Offensive. After succeeding in breaking the Austro-Hungarian front in the Battle of Mărăşti, the Russians and the Romanians had to stop their advance because of the disaster of the Kerensky Offensive. Mackensen then launched an unsuccessful counterattack at Mărăşeşti, and concurrently, an Austro-Hungarian offensive at Oituz also failed. Altogether, these operations represented an important success for Romania, as the unoccupied territories (most of Moldavia) remained free.

When the Bolsheviks took power in Russia and signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Romania was left isolated and surrounded by the Central Powers and it had little choice but to negotiate an armistice, signed by the combatants on December 9, 1917, at Focşani.

Aftermath

Treaty of Bucharest

On May 7, 1918, Romania was forced[citation needed] to conclude the Treaty of Bucharest with the Central Powers.

The Germans were able to repair the oil fields around Ploieşti and by the end of the war had pumped a million tons of oil. They also requisitioned two million tons of grain from the Romanian farmers. These materials were vital in keeping Germany in the war to the end of 1918.[12]

Romania reenters the war, November 1918

After the successful offensive on the Thessaloniki front which put Bulgaria out of the war, Romania re-entered the war on November 10, 1918, a day before its end in the West.

On November 28, 1918, the Romanian representatives of Bukovina voted for union with the Kingdom of Romania, followed by the proclamation of the union of Transylvania with the Kingdom of Romania on December 1, 1918, by the representatives of Transylvanian Romanians gathered at Alba Iulia, while the representatives of the Transylvanian Saxons approved the act on December 15 at an assembly in Mediaş.

The Treaty of Versailles recognized these proclamations under the right of national self-determination (see the Wilsonian Fourteen Points). Also Germany agreed under the terms of the same treaty (Article 259) to renounce to all the benefits provided by the Treaty of Bucharest in 1918.[13]

The Romanian control of Transylvania, which had also a Hungarian population of 1,662,000 (34%, according to the census data of 1910), was widely resented in the new nation state of Hungary. A war between the Hungarian Soviet Republic and the Kingdom of Romania, which was part of an Entente force with Serbian and Czechoslovakian armies attacking Hungary from all sides, was fought in 1919 and ended with a partial Romanian occupation of Hungary. Romanian forces later instated Admiral Horthy as regent of Hungary.

Military analysis of the campaign

Clearly, Romania entered the war at a bad moment. Entry on the Allied side in 1914 or 1915 could have prevented the conquest of Serbia. Entry in early 1916 might have allowed the Brusilov Offensive to succeed. A mutual distrust was shared by Romania and the one major power that was in the position of directly helping it, Russia.

General Vincent Esposito argues that the Romanian high command made grave strategic and operational mistakes:

Militarily, Romania's strategy could not have been worse. In choosing Transylvania as the initial objective, the Romanian Army ignored the Bulgarian Army to her rear. When the advance through the mountains failed, the high command refused to economize forces on that front to allow the creation of a mobile reserve with which Falkenhayn's later thrusts could be countered. Nowhere did the Romanians properly mass their forces to achieve concentration of combat power.[11]

The failure of the Romania front for the Entente was also the result of several factors beyond Romania's control. The failed Salonika Offensive did not meet the expectation of Romania's "guaranteed security" from Bulgaria.[14] This proved to be a critical strain on Romania's ability to wage a successful offensive in Transylvania, as it needed to divert troops south to the defense of Dobruja.[15] Furthermore, Russian reinforcements in Romania did not materialize to the number of 200,000 soldiers initially demanded.[16] Romania was thus placed in a difficult situation several months after it joined the war, with the Entente unable to provide the support it had promised earlier.

References

- ^ Българската армия в Световната война 1915 - 1918, vol. VIII , pag. 792

- ^ Българската армия в Световната война 1915 - 1918, vol. VIII , pag. 283

- ^ România în războiul mondial (1916-1919), vol. I, pag. 58

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/greatwar/resources/casdeath_pop.html

- ^ Cyril Falls, The Great War p. 228

- ^ Vincent Esposito, Atlas of American Wars, Vol 2, text for map 37

- ^ John Keegan, The First World War, pg. 306

- ^ To Ride the Storm: The Story of the Airship R.101 by Sir Peter G. Masefield, pages 16-17 (1982, William Kimber, London) ISBN 0 7183 0068 8

- ^ Paul von Hindenburg, Out of My Life, Vol. I, trans. F.A. Holt (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1927), 243.

- ^ Българската армия в Световната война 1915 - 1918, vol. VIII , pag. 282-283

- ^ a b Vincent Esposito, Atlas of American Wars, Vol 2, text for map 40

- ^ John Keegan, World War I, pg. 308

- ^ Articles 248 - 263 - World War I Document Archive

- ^ Torrey, Romania and World War I, p. 27

- ^ Istoria României, Vol. IV, p. 366

- ^ Torrey, Romania and World War I, p. 65

Sources

- Esposito, Vincent (ed.) (1959). The West Point Atlas of American Wars - Vol. 2; maps 37-40. Frederick Praeger Press.

- Falls, Cyril. The Great War (1960), ppg 228-230.

- Keegan, John. The First World War (1998), ppg 306-308. Alfred A. Knopf Press.

See also

External links

- Austro-Hungarian Empire and World War I

- Battles involving Austria–Hungary

- Battles involving Bulgaria

- Battles involving the Ottoman Empire

- Campaigns and theatres of World War I

- Battles involving Romania

- Battles involving Russia

- History of Romania

- World War I by country

- Military operations of World War I involving Germany