Scottish Gaelic

| Scottish Gaelic | |

|---|---|

| Gàidhlig | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈkaːlɪkʲ] |

| Native to | United Kingdom Canada |

| Region | Scotland; Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia in Canada |

| Ethnicity | Scottish people |

Native speakers | 57,000 fluent L1 and L2 speakers in Scotland (2011)[1] 87,000 people in Scotland reported having some Gaelic language ability in 2011.[1] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Scottish Gaelic orthography (Latin script) | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | gd |

| ISO 639-2 | gla |

| ISO 639-3 | gla |

| Glottolog | scot1245 |

| ELP | Scottish Gaelic |

| Linguasphere | 50-AAA |

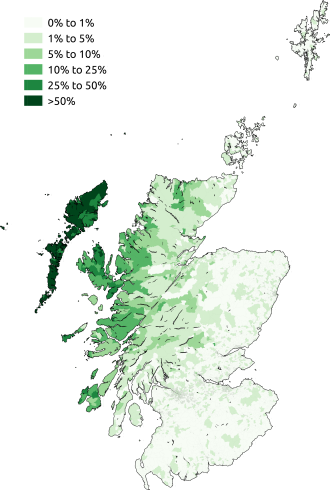

2001 distribution of Gaelic speakers in Scotland | |

Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig [ˈkaːlɪkʲ] ) or Scots Gaelic, sometimes also referred to simply as Gaelic, is a Celtic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. A member of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic languages, Scottish Gaelic, like Modern Irish and Manx, developed out of Middle Irish. Most of modern Scotland was once Gaelic-speaking, as evidenced especially by Gaelic-language placenames.

In the 2011 census of Scotland, 57,375 people (1.1% of the Scottish population aged over three years old) reported as able to speak Gaelic, 1,275 fewer than in 2001. The highest percentages of Gaelic speakers were in the Outer Hebrides. Only about half of speakers were fully literate in the language.[1] Nevertheless, there are revival efforts, and the number of speakers of the language under age 20 did not decrease between the 2001 and 2011 censuses.[2] Outside Scotland, Canadian Gaelic is spoken mainly in Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

Scottish Gaelic is not an official language of either the European Union or the United Kingdom. However, it is classed as an indigenous language under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, which the British government has ratified, and the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005 established a language development body, Bòrd na Gàidhlig.

Nomenclature

Aside from "Scottish Gaelic", the language may also be referred to simply as "Gaelic", pronounced /ˈɡɑːlɪk/ or /ˈɡeɪlɪk/ in English. "Gaelic" may also refer to the Irish language.[3]

Scottish Gaelic is distinct from Scots, the Middle English-derived language varieties which had come to be spoken in most of the Lowlands of Scotland by the early modern era. Prior to the 15th century, these dialects were known as Inglis ("English") by its own speakers, with Gaelic being called Scottis ("Scottish"). From the late 15th century, however, it became increasingly common for such speakers to refer to Scottish Gaelic as Erse ("Irish") and the Lowland vernacular as Scottis.[4][page needed] Today, Scottish Gaelic is recognised as a separate language from Irish, so the word Erse in reference to Scottish Gaelic is no longer used.[5][page needed]

History

Origins

Gaelic was commonly believed to have been brought to Scotland, in the 4th–5th centuries CE, by settlers from Ireland who founded the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata on Scotland's west coast in present-day Argyll.[6]: 551 [7]: 66 However, this theory is no longer universally accepted. In his academic paper Were the Scots Irish?, archaeologist Dr Ewan Campbell says that there is no archaeological or placename evidence of a migration or takeover. [8] This lack of archaeological evidence was previously noted by Professor Leslie Alcock.[8] Archaeological evidence shows that Argyll was different from Ireland, before and after the supposed migration, but that it also formed part of the Irish Sea province with Ireland, being easily distinguished from the rest of Scotland.[9] Gaelic in Scotland was mostly confined to Dál Riata until the eighth century, when it began expanding into Pictish areas north of the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde. By 900, Pictish appears to have become extinct, completely replaced by Gaelic.[10]: 238–244 An exception might be made for the Northern Isles, however, where Pictish was more likely supplanted by Norse rather than by Gaelic.[11]

In 1018, after the conquest of the Lothians by the Kingdom of Scotland, Gaelic reached its social, cultural, political, and geographic zenith.[12]: 16–18 Colloquial speech in Scotland had been developing independently of that in Ireland since the eighth century.[13] For the first time, the entire region of modern-day Scotland was called Scotia in Latin, and Gaelic was the lingua Scotia.[10]: 276 [14]: 554 In southern Scotland, Gaelic was strong in Galloway, adjoining areas to the north and west, West Lothian, and parts of western Midlothian. It was spoken to a lesser degree in north Ayrshire, Renfrewshire, the Clyde Valley and eastern Dumfriesshire. In south-eastern Scotland, there is no evidence that Gaelic was ever widely spoken.[citation needed]

Decline

Many historians mark the reign of King Malcom Canmore (Malcolm III) as the beginning of Gaelic's eclipse in Scotland. His wife Margaret spoke no Gaelic, gave her children Anglo-Saxon rather than Gaelic names, and brought many English bishops, priests, and monastics to Scotland.[12]: 19 When Malcolm and Margaret died in 1093, the Gaelic aristocracy rejected their anglicised sons and instead backed Malcolm's brother Donald Bàn.[citation needed] Donald had spent 17 years in Gaelic Ireland and his power base was in the thoroughly Gaelic west of Scotland. He was the last Scottish monarch to be buried on Iona, the traditional burial place of the Gaelic Kings of Dàl Riada and the Kingdom of Alba.[citation needed] However, during the reigns of Malcolm Canmore's sons, Edgar, Alexander I and David I (their successive reigns lasting 1097–1153), Anglo-Norman names and practices spread throughout Scotland south of the Forth–Clyde line and along the northeastern coastal plain as far north as Moray. Norman French completely displaced Gaelic at court. The establishment of royal burghs throughout the same area, particularly under David I, attracted large numbers of foreigners speaking Old English. This was the beginning of Gaelic's status as a predominantly rural language in Scotland.[12]: 19–23

Clan chiefs in the northern and western parts of Scotland continued to support Gaelic bards who remained a central feature of court life there. The semi-independent Lordship of the Isles in the Hebrides and western coastal mainland remained thoroughly Gaelic since the language's recovery there in the 12th century, providing a political foundation for cultural prestige down to the end of the 15th century.[14]: 553–6

By the mid-14th century what eventually came to be called Scots (at that time termed Inglis) emerged as the official language of government and law.[15]: 139 Scotland's emergent nationalism in the era following the conclusion of the Wars of Scottish Independence was organized using Scots as well. For example, the nation's great patriotic literature including John Barbour's The Brus (1375) and Blind Harry's The Wallace (before 1488) was written in Scots, not Gaelic. By the end of the 15th century, English/Scots speakers referred to Gaelic instead as 'Yrisch' or 'Erse', i.e. Irish and their own language as 'Scottis'.[12]: 19–23

Modern era

Scottish Gaelic has a rich oral (beul-aithris) and written tradition, having been the language of the bardic culture of the Highland clans for many years. However, the language was suppressed by the Scottish and later British states, especially after the Battle of Culloden in 1746, during the Highland Clearances, and by the exclusion of Scottish Gaelic from the educational system. Even before then, charitable schools operated by the Society in Scotland for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge (SSPCK) used instructional methods designed to suppress the language in favour of English and corporal punishment against students using Gaelic.[16]: 1–13 [17]: 35 This was counterbalanced by the activities of the Gaelic Schools Society, founded in 1811. Their primary purpose was to teach Gaels literacy in their own language, with emphasis on being able to read the Bible.[18]: 98

The first well-known translation of the Bible into Scottish Gaelic was made in 1767 when Dr James Stuart of Killin and Dugald Buchanan of Rannoch produced a translation of the New Testament. The translation of the entire Bible was completed in 1801. In the first quarter of the 19th century, the SSPCK and the British and Foreign Bible Society distributed 60,000 Gaelic Bibles and 80,000 New Testaments.[18]: 98 Very few European languages have made the transition to a modern literary language without an early modern translation of the Bible; the lack of a well-known translation may have contributed to the decline of Scottish Gaelic.[19]: 168–202

Defunct dialects

Dialects of Lowland Gaelic have been defunct since the 18th century. Gaelic in the Eastern and Southern Scottish Highlands, although alive in the mid-twentieth century, is now largely defunct. Although modern Scottish Gaelic is dominated by the dialects of the Outer Hebrides and Isle of Skye, there remain some speakers of the Inner Hebridean dialects of Tiree and Islay, and even a few elderly native speakers from Highland areas including Wester Ross, northwest Sutherland, Lochaber, and Argyll. Dialects on both sides of the Straits of Moyle (the North Channel) linking Scottish Gaelic with Irish are now extinct, though native speakers were still to be found on the Mull of Kintyre, in Rathlin and in North East Ireland as late as the mid-20th century. Records of their speech show that Irish and Scottish Gaelic existed in a dialect chain with no clear language boundary.[citation needed] Some features of moribund dialects have been preserved in Nova Scotia, including the pronunciation of the broad or velarised l (l̪ˠ) as [w], as in the Lochaber dialect.[20]: 131

Status

This section needs expansion with: preservation and revitalization efforts; Canadian Gaelic stats. You can help by adding to it. (October 2015) |

The Endangered Languages Project lists Gaelic's status as "threatened", with "20,000 to 30,000 active users".[21][better source needed] UNESCO classifies Gaelic as "definitely endangered".[22]

Number of speakers

| Year | Scottish population | Monolingual Gaelic speakers | Gaelic and English bilinguals | Total Gaelic language group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1755 | 1,265,380 | Unknown | Unknown | 289,798 | 22.9% | ||

| 1800 | 1,608,420 | Unknown | Unknown | 297,823 | 18.5% | ||

| 1881 | 3,735,573 | Unknown | Unknown | 231,594 | 6.1% | ||

| 1891 | 4,025,647 | 43,738 | 1.1% | 210,677 | 5.2% | 254,415 | 6.3% |

| 1901 | 4,472,103 | 28,106 | 0.6% | 202,700 | 4.5% | 230,806 | 5.1% |

| 1911 | 4,760,904 | 8,400 | 0.2% | 183,998 | 3.9% | 192,398 | 4.2% |

| 1921 | 4,573,471 | 9,829 | 0.2% | 148,950 | 3.3% | 158,779 | 3.5% |

| 1931 | 4,588,909 | 6,716 | 0.2% | 129,419 | 2.8% | 136,135 | 3.0% |

| 1951 | 5,096,415 | 2,178 | 0.1% | 93,269 | 1.8% | 95,447 | 1.9% |

| 1961 | 5,179,344 | 974 | <0.1% | 80,004 | 1.5% | 80,978 | 1.5% |

| 1971 | 5,228,965 | 477 | <0.1% | 88,415 | 1.7% | 88,892 | 1.7% |

| 1981 | 5,035,315 | — | — | 82,620 | 1.6% | 82,620 | 1.6% |

| 1991 | 5,083,000 | — | — | 65,978 | 1.4% | 65,978 | 1.4% |

| 2001 | 5,062,011 | — | — | 58,652 | 1.2% | 58,652 | 1.2% |

| 2011 | 5,295,403 | — | — | 57,602 | 1.1% | 57,602 | 1.1% |

| 2022 | 5,447,700 | — | — | 69,701 | 1.3% | 69,701 | 1.3% |

The 1755–2001 figures are census data quoted by MacAulay.[23]: 141 The 2011 Gaelic speakers figures come from table KS206SC of the 2011 Census. The 2011 total population figure comes from table KS101SC. Note that the numbers of Gaelic speakers relate to the numbers aged 3 and over, and the percentages are calculated using those and the number of the total population aged 3 and over.

Distribution in Scotland

The 2011 UK Census showed a total of 57,375 Gaelic speakers in Scotland (1.1% of population over three years old), of whom only 32,400 could also read and write, due to the lack of Gaelic medium education in Scotland.[24] Compared to the 2001 Census, there has been a diminution of approximately 1,300 people.[25] This is the smallest drop between censuses since the Gaelic language question was first asked in 1881. The Scottish Government's language minister and Bord na Gaidhlig took this as evidence that Gaelic's long decline has slowed.[26]

The main stronghold of the language continues to be the Outer Hebrides (Na h-Eileanan Siar), where the overall proportion of speakers is 52.2%. Important pockets of the language also exist in the Highlands (5.4%) and in Argyll and Bute (4.0%), and Inverness, where 4.9% speak the language. The locality with the largest absolute number is Glasgow with 5,878 such persons, who make up over 10% of all of Scotland's Gaelic speakers.

Gaelic continues to decline in its traditional heartland. Between 2001 and 2011, the absolute number of Gaelic speakers fell sharply in the Western Isles (−1,745), Argyll & Bute (−694), and Highland (−634). The drop in Stornoway, the largest parish in the Western Isles by population, was especially acute, from 57.5% of the population in 1991 to 43.4% in 2011.[27] The only parish outside the Western Isles over 40% Gaelic-speaking is Kilmuir in Northern Skye at 46%. The islands in the Inner Hebrides with significant percentages of Gaelic speakers are Tiree (38.3%), Raasay (30.4%), Skye (29.4%), Lismore (26.9%), Colonsay (20.2%), and Islay (19.0%).

As a result of continued decline in the traditional Gaelic heartlands, today no civil parish in Scotland has a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 65% (the highest value is in Barvas, Lewis, with 64.1%). In addition, no civil parish on mainland Scotland has a proportion of Gaelic speakers greater than 20% (the highest value is in Ardnamurchan, Highland, with 19.3%). Out of a total of 871 civil parishes in Scotland, the proportion of Gaelic speakers exceeds 50% in 7 parishes, exceeds 25% in 14 parishes, and exceeds 10% in 35 parishes.[citation needed] Decline in traditional areas has recently been balanced by growth in the Scottish Lowlands. Between the 2001 and 2011 censuses, the number of Gaelic speakers rose in nineteen of the country's 32 council areas. The largest absolute gains were in Aberdeenshire (+526), North Lanarkshire (+305), Aberdeen City (+216), and East Ayrshire (+208). The largest relative gains were in Aberdeenshire (+0.19%), East Ayrshire (+0.18%), Moray (+0.16%), and Orkney (+0.13%).[citation needed]

As with other Celtic languages, monolingualism is non-existent except among native-speaking children under school age in traditional Gàidhealtachd areas.[citation needed] In 2014, the census of pupils in Scotland showed 497 pupils in publicly funded schools had Gaelic as the main language at home, a drop of 18% from 606 students in 2010. During the same period, Gaelic medium education in Scotland has grown, with 3,583 pupils being educated in a Gaelic-immersion environment in 2014, up from 2,638 pupils in 2009.[28] However, even among pupils enrolled in Gaelic medium schools, 81% of primary students and 74% of secondary students report using English more often than Gaelic when speaking with their mothers at home.[29]

Usage

Official

Scotland

Scottish Parliament

Gaelic has long suffered from its lack of use in educational and administrative contexts and was long suppressed.[30]

The UK government has ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in respect of Gaelic. Along with Irish and Welsh, Gaelic is designated under Part III of the Charter, which requires the UK Government to take a range of concrete measures in the fields of education, justice, public administration, broadcasting and culture. It has not received the same degree of official recognition from the UK Government as Welsh. With the advent of devolution, however, Scottish matters have begun to receive greater attention, and it achieved a degree of official recognition when the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act was enacted by the Scottish Parliament on 21 April 2005.

The key provisions of the Act are:[31]

- Establishing the Gaelic development body, Bòrd na Gàidhlig, (BnG), on a statutory basis with a view to securing the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland commanding equal respect to the English language and to promote the use and understanding of Gaelic.

- Requiring BnG to prepare a National Gaelic Language Plan every five years for approval by Scottish Ministers.

- Requiring BnG to produce guidance on Gaelic medium education and Gaelic as a subject for education authorities.

- Requiring public bodies in Scotland, both Scottish public bodies and cross-border public bodies insofar as they carry out devolved functions, to develop Gaelic language plans in relation to the services they offer, if requested to do so by BnG.

Following a consultation period, in which the government received many submissions, the majority of which asked that the bill be strengthened, a revised bill was published; the main alteration was that the guidance of the Bòrd is now statutory (rather than advisory). In the committee stages in the Scottish Parliament, there was much debate over whether Gaelic should be given 'equal validity' with English. Due to executive concerns about resourcing implications if this wording was used, the Education Committee settled on the concept of 'equal respect'. It is not clear what the legal force of this wording is.

The Act was passed by the Scottish Parliament unanimously, with support from all sectors of the Scottish political spectrum, on 21 April 2005. Under the provisions of the Act, it will ultimately fall to BnG to secure the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland.

Some commentators, such as Éamonn Ó Gribín (2006) argue that the Gaelic Act falls so far short of the status accorded to Welsh that one would be foolish or naïve to believe that any substantial change will occur in the fortunes of the language as a result of Bòrd na Gàidhlig's efforts.[32]

On 10 December 2008, to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Scottish Human Rights Commission had the UDHR translated into Gaelic for the first time.[33]

However, given there are no longer any monolingual Gaelic speakers,[34] following an appeal in the court case of Taylor v Haughney (1982), involving the status of Gaelic in judicial proceedings, the High Court ruled against a general right to use Gaelic in court proceedings.[35]

Qualifications in the language

The Scottish Qualifications Authority offer two streams of Gaelic examination across all levels of the syllabus: Gaelic for learners (equivalent to the modern foreign languages syllabus) and Gaelic for native speakers (equivalent to the English syllabus).[36][37]

An Comunn Gàidhealach performs assessment of spoken Gaelic, resulting in the issue of a Bronze Card, Silver Card or Gold Card. Syllabus details are available on An Comunn's website. These are not widely recognised as qualifications, but are required for those taking part in certain competitions at the annual mods.[38]

European Union

In October 2009, a new agreement was made which allows Scottish Gaelic to be used formally between Scottish Government ministers and European Union officials. The deal was signed by Britain's representative to the EU, Sir Kim Darroch, and the Scottish government. This does not give Scottish Gaelic official status in the EU, but gives it the right to be a means of formal communications in the EU's institutions. The Scottish government will have to pay for the translation from Gaelic to other European languages. The deal was received positively in Scotland; Secretary of State for Scotland Jim Murphy said the move was a strong sign of the UK government's support for Gaelic. He said that "Allowing Gaelic speakers to communicate with European institutions in their mother tongue is a progressive step forward and one which should be welcomed". Culture Minister Mike Russell said that "this is a significant step forward for the recognition of Gaelic both at home and abroad and I look forward to addressing the council in Gaelic very soon. Seeing Gaelic spoken in such a forum raises the profile of the language as we drive forward our commitment to creating a new generation of Gaelic speakers in Scotland."[39]

The Scottish Gaelic used in Machine-readable British passports differs from Irish passports in places. "Passport" is rendered Cead-siubhail (in Irish, Pas); "The European Union", Aonadh Eòrpach (in Irish, An tAontas Eorpach), while "Northern Ireland" is Èirinn a Tuath in Gaelic (the Irish equivalent is Tuaisceart Éireann).

Signage

Bilingual road signs, street names, business and advertisement signage (in both Gaelic and English) are gradually being introduced throughout Gaelic-speaking regions in the Highlands and Islands, including Argyll. In many cases, this has simply meant re-adopting the traditional spelling of a name (such as Ràtagan or Loch Ailleart rather than the anglicised forms Ratagan or Lochailort respectively).

Bilingual railway station signs are now more frequent than they used to be. Practically all the stations in the Highland area use both English and Gaelic, and the spread of bilingual station signs is becoming ever more frequent in the Lowlands of Scotland, including areas where Gaelic has not been spoken for a long time.[citation needed]

This has been welcomed by many supporters of the language as a means of raising its profile as well as securing its future as a 'living language' (i.e. allowing people to use it to navigate from A to B in place of English) and creating a sense of place. However, in some places, such as Caithness, the Highland Council's intention to introduce bilingual signage has incited controversy.[40]

The Ordnance Survey has acted in recent years to correct many of the mistakes that appear on maps. They announced in 2004 that they intended to correct them and set up a committee to determine the correct forms of Gaelic place names for their maps.[citation needed] Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba ("Place names in Scotland") is the national advisory partnership for Gaelic place names in Scotland.[41]

Canada

In the nineteenth century, Canadian Gaelic was the third-most widely spoken language in Canada[42] and Gaelic-speaking immigrant communities could be found throughout the country. Gaelic poets in Canada produced a significant literary tradition.[43] The number of Gaelic-speaking individuals and communities declined sharply, however, after the First World War.[44]

Nova Scotia is home to 1,275 Gaelic speakers as of 2011.[45] of whom 300 claim to have Gaelic as their "mother tongue."[46][a] The Nova Scotia government maintains an Office of Gaelic Affairs which works to promote the Gaelic language, culture, and tourism. As in Scotland, areas of North-Eastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton have bilingual street signs. Nova Scotia also has Comhairle na Gàidhlig (The Gaelic Council of Nova Scotia), a non-profit society dedicated to the maintenance and promotion of the Gaelic language and culture in Maritime Canada.

Maxville Public School in Maxville, Glengarry, Ontario, Canada offers Scottish Gaelic lessons weekly.[citation needed] In Prince Edward Island, the Colonel Gray High School now offers both an introductory and an advanced course in Gaelic; both language and history are taught in these classes.[citation needed] This is the first recorded time that Gaelic has ever been taught as an official course on Prince Edward Island.

The province of British Columbia is host to the Comunn Gàidhlig Bhancoubhair (The Gaelic Society of Vancouver), the Vancouver Gaelic Choir, the Victoria Gaelic Choir, as well as the annual Gaelic festival Mòd Vancouver. The city of Vancouver's Scottish Cultural Centre also holds seasonal Scottish Gaelic evening classes.

Media

The BBC operates a Gaelic-language radio station Radio nan Gàidheal as well as a television channel, BBC Alba. Launched on 19 September 2008, BBC Alba is widely available in the UK (on Freeview, Freesat, Sky and Virgin Media). It also broadcasts across Europe on the Astra 2 satellites.[47] The channel is being operated in partnership between BBC Scotland and MG Alba – an organisation funded by the Scottish Government, which works to promote the Gaelic language in broadcasting.[48] The ITV franchise in central Scotland, STV Central, produces a number of Scottish Gaelic programmes for both BBC Alba and its own main channel.[48]

Until BBC Alba was broadcast on Freeview, viewers were able to receive the channel TeleG, which broadcast for an hour every evening. Upon BBC Alba's launch on Freeview, it took the channel number that was previously assigned to TeleG.

There are also television programmes in the language on other BBC channels and on the independent commercial channels, usually subtitled in English. The ITV franchise in the north of Scotland, STV North (formerly Grampian Television) produces some non-news programming in Scottish Gaelic.

Education

Scotland

| Year | Number of students in Gaelic medium education |

Percentage of all students in Scotland |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2,480 | 0.35% |

| 2006 | 2,535 | 0.36%[49] |

| 2007 | 2,601 | 0.38% |

| 2008 | 2,766 | 0.40%[50] |

| 2009 | 2,638 | 0.39%[51] |

| 2010 | 2,647 | 0.39%[52] |

| 2011 | 2,929 | 0.44%[53] |

| 2012 | 2,871 | 0.43%[54] |

| 2013 | 2,953 | 0.44%[55] |

| 2014 | 3,583 | 0.53%[56] |

| 2015 | 3,660 | 0.54%[57] |

| 2016 | 3,892 | 0.57%[58] |

| 2017 | 3,965 | 0.58%[59] |

The Education (Scotland) Act 1872, which completely ignored Gaelic, and led to generations of Gaels being forbidden to speak their native language in the classroom, is now recognised as having dealt a major blow to the language. People still living can recall being beaten for speaking Gaelic in school.[60] Even later, when these attitudes had changed, little provision was made for Gaelic medium education in Scottish schools. As late as 1958, even in Highland schools, only 20% of primary students were taught Gaelic as a subject, and only 5% were taught other subjects through the Gaelic language.[29]

Gaelic-medium playgroups for young children began to appear in Scotland during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Parent enthusiasm may have been a factor in the "establishment of the first Gaelic medium primary school units in Glasgow and Inverness in 1985".[61]

The first modern solely Gaelic-medium secondary school, Sgoil Ghàidhlig Ghlaschu ("Glasgow Gaelic School"), was opened at Woodside in Glasgow in 2006 (61 partially Gaelic-medium primary schools and approximately a dozen Gaelic-medium secondary schools also exist). According to Bòrd na Gàidhlig, a total of 2,092 primary pupils were enrolled in Gaelic-medium primary education in 2008–09, as opposed to 24 in 1985.[62]

The Columba Initiative, also known as colmcille (formerly Iomairt Cholm Cille), is a body that seeks to promote links between speakers of Scottish Gaelic and Irish.

Canada

In May 2004, the Nova Scotia government announced the funding of an initiative to support the language and its culture within the province. Several public schools in Northeastern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton offer Gaelic classes as part of the high-school curriculum.[63] The government's Gaelic Affairs offers lunch-time lessons to public servants in Halifax.

Maxville Public School in Maxville, Glengarry, Ontario, Canada offers Scottish Gaelic lessons weekly, and Prince Edward Island, Canada, the Colonel Gray High School offer an introductory and an advanced course in Scottish Gaelic.[64]

Higher and further education

A number of Scottish and some Irish universities offer full-time degrees including a Gaelic language element, usually graduating as Celtic Studies.

St. Francis Xavier University, the Gaelic College of Celtic Arts and Crafts and Cape Breton University (formerly University College Of Cape Breton) in Nova Scotia, Canada also offer a Celtic Studies degrees and/or Gaelic language programs.

In Russia the Moscow State University offers Gaelic language, history and culture courses.

The University of the Highlands and Islands offers a range of Gaelic language, history and culture courses at NC, HND, BA (ordinary), BA (Hons) and Msc, and offers opportunities for postgraduate research through the medium of Gaelic. Residential courses at Sabhal Mòr Ostaig on the Isle of Skye offer adults the chance to become fluent in Gaelic in one year. Many continue to complete degrees, or to follow up as distance learners. A number of other colleges offer a one-year certificate course, which is also available online (pending accreditation).

Lews Castle College's Benbecula campus offers an independent 1-year course in Gaelic and Traditional Music (FE, SQF level 5/6).

Church

In the Western Isles, the isles of Lewis, Harris and North Uist have a Presbyterian majority (largely Church of Scotland – Eaglais na h-Alba in Gaelic, Free Church of Scotland and Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland.) The isles of South Uist and Barra have a Catholic majority. All these churches have Gaelic-speaking congregations throughout the Western Isles. Notable city congregations with regular services in Gaelic are St Columba's Church, Glasgow and Greyfriars Tolbooth & Highland Kirk, Edinburgh. Leabhar Sheirbheisean – a shorter Gaelic version of the English-language Book of Common Order – was published in 1996 by the Church of Scotland.

The widespread use of English in worship has often been suggested as one of the historic reasons for the decline of Gaelic. The Church of Scotland is supportive today,[vague] but has a shortage of Gaelic-speaking ministers. The Free Church also recently announced plans to abolish Gaelic-language communion services, citing both a lack of ministers and a desire to have their congregations united at communion time.[65]

Literature

From the sixth century to the present day, Scottish Gaelic has been used as the language of literature. Two prominent writers of the twentieth century are Anne Frater and Sorley Maclean.

Names

Personal names

Gaelic has its own version of European-wide names which also have English forms, for example: Iain (John), Alasdair (Alexander), Uilleam (William), Catrìona (Catherine), Raibeart (Robert), Cairistìona (Christina), Anna (Ann), Màiri (Mary), Seumas (James), Pàdraig (Patrick) and Tòmas (Thomas). Not all traditional Gaelic names have direct equivalents in English: Oighrig, which is normally rendered as Euphemia (Effie) or Henrietta (Etta) (formerly also as Henny or even as Harriet), or, Diorbhal, which is "matched" with Dorothy, simply on the basis of a certain similarity in spelling. Many of these traditional Gaelic-only names are now regarded as old-fashioned, and hence are rarely or never used.

Some names have come into Gaelic from Old Norse; for example, Somhairle ( < Somarliðr), Tormod (< Þórmóðr), Raghnall or Raonull (< Rögnvaldr), Torcuil (< Þórkell, Þórketill), Ìomhar (Ívarr). These are conventionally rendered in English as Sorley (or, historically, Somerled), Norman, Ronald or Ranald, Torquil and Iver (or Evander).

Some Scottish names are Anglicized forms of Gaelic names: Aonghas → (Angus), Dòmhnall→ (Donald), for instance. Hamish, and the recently established Mhairi (pronounced [vaːri]) come from the Gaelic for, respectively, James, and Mary, but derive from the form of the names as they appear in the vocative case: Seumas (James) (nom.) → Sheumais (voc.), and, Màiri (Mary) (nom.) → Mhàiri (voc.).

Surnames

The most common class of Gaelic surnames are those beginning with mac (Gaelic for "son"), such as MacGillEathain/MacIllEathain[66][67] (MacLean). The female form is nic (Gaelic for "daughter"), so Catherine MacPhee is properly called in Gaelic, Catrìona Nic a' Phì[68] (strictly, "nic" is a contraction of the Gaelic phrase nighean mhic, meaning "daughter of the son", thus NicDhòmhnaill[69] really means "daughter of MacDonald" rather than "daughter of Donald"). The "of" part actually comes from the genitive form of the patronymic that follows the prefix; in the case of MacDhòmhnaill, Dhòmhnaill ("of Donald") is the genitive form of Dòmhnall ("Donald").[70]

Several colours give rise to common Scottish surnames: bàn (Bain – white), ruadh (Roy – red), dubh (Dow, Duff – black), donn (Dunn – brown), buidhe (Bowie – yellow).

Phonology

Most varieties of Gaelic have either 8 or 9 vowel phonemes (/i e ɛ a ɔ o u ɤ ɯ/), which can be either long or short. There are also two reduced vowels ([ə ɪ]) which only occur short. Although some vowels are strongly nasal, instances of distinctive nasality are rare. There are about nine diphthongs and a few triphthongs.

Most consonants have both palatal and non-palatal counterparts, including a very rich system of liquids, nasals and trills (i.e. 3 contrasting l sounds, 3 contrasting n sounds and 3 contrasting r sounds). The historically voiced stops [b d̪ ɡ] have lost their voicing, so the phonemic contrast today is between unaspirated [p t̪ k] and aspirated [pʰ t̪ʰ kʰ]. In many dialects, these stops may however gain voicing through secondary articulation through a preceding nasal, for examples doras [t̪ɔɾəs̪] "door" but an doras "the door" as [ən̪ˠ d̪ɔɾəs̪] or [ə n̪ˠɔɾəs̪].

In some fixed phrases, these changes are shown permanently, as the link with the base words has been lost, as in an-dràsta "now", from an tràth-sa "this time/period".

In medial and final position, the aspirated stops are preaspirated rather than aspirated.

Grammar

Scottish Gaelic is an Indo-European language with an inflecting morphology, verb–subject–object word order and two grammatical genders.

Noun inflection

Gaelic nouns inflect for four cases (nominative/accusative, vocative, genitive and dative) and three numbers (singular, dual and plural).

They are also normally classed as either masculine or feminine. A small number of words that used to belong to the neuter class show some degree of gender confusion. For example, in some dialects am muir "the sea" behaves as a masculine noun in the nominative case, but as a feminine noun in the genitive (na mara).

Nouns are marked for case in a number of ways, most commonly involving various combinations of lenition, palatalisation and suffixation.

Verb inflection

There are 12 irregular verbs.[71] Most other verbs follow a fully predictable paradigm, although polysyllabic verbs ending in laterals can deviate from this paradigm as they show syncopation.

There are:

- Three persons: 1st, 2nd and 3rd

- Two numbers: singular and plural

- Two voices: traditionally called active and passive, but actually personal and impersonal

- Three non-composed combined TAM forms expressing tense, aspect and mood, i.e. non-past (future-habitual), conditional (future of the past), and past (preterite); several composed TAM forms, such as pluperfect, future perfect, present perfect, present continuous, past continuous, conditional perfect, etc. Two verbs, bi, used to attribute a notionally temporary state, action, or quality to the subject, and is, used to show a notional permanent identity or quality, have non-composed present and non-past tense forms: (bi) tha [perfective present], bidh/bithidh [imperfective non-past];[67] (is) is imperfective non-past, bu past and conditional.

- Four moods: independent (used in affirmative main clause verbs), relative (used in verbs in affirmative relative clauses), dependent (used in subordinate clauses, anti-affirmative relative clauses, and anti-affirmative main clauses), and subjunctive.

Word order

Word order is strictly verb–subject–object, including questions, negative questions and negatives. Only a restricted set of preverb particles may occur before the verb.

Lexicon

The majority of the vocabulary of Scottish Gaelic is native Celtic. There are a large number of borrowings from Latin, (muinntir, Didòmhnaich from (dies) dominica), Norse (eilean from eyland, sgeir from sker), French (seòmar from chambre) and Scots (aidh, bramar).[citation needed]

There are also many Brythonic influences on Scottish Gaelic. Scottish Gaelic contains a number of apparently P-Celtic loanwords, but it is not always possible to disentangle P and Q Celtic words. However some common words such as monadh = Welsh mynydd, Cumbric *monidh are clearly of P-Celtic origin.[citation needed]

In common with other Indo-European languages, the neologisms which are coined for modern concepts are typically based on Greek or Latin, although often coming through English; television, for instance, becomes telebhisean and computer becomes coimpiùtar. Some speakers use an English word even if there is a Gaelic equivalent, applying the rules of Gaelic grammar. With verbs, for instance, they will simply add the verbal suffix (-eadh, or, in Lewis, -igeadh, as in, "Tha mi a' watcheadh (Lewis, "watchigeadh") an telly" (I am watching the television), instead of "Tha mi a' coimhead air an telebhisean". This phenomenon was described over 170 years ago, by the minister who compiled the account covering the parish of Stornoway in the New Statistical Account of Scotland, and examples can be found dating to the eighteenth century.[72] However, as Gaelic medium education grows in popularity, a newer generation of literate Gaels is becoming more familiar with modern Gaelic vocabulary.[citation needed]

Loanwords into other languages

Scottish Gaelic has also influenced the Scots language and English, particularly Scottish Standard English. Loanwords include: whisky, slogan, brogue, jilt, clan, trousers, gob, as well as familiar elements of Scottish geography like ben (beinn), glen (gleann) and loch. Irish has also influenced Lowland Scots and English in Scotland, but it is not always easy to distinguish its influence from that of Scottish Gaelic.[73][page needed]

Writing system

Alphabet

The modern Scottish Gaelic alphabet has 18 letters:

- A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, L, M, N, O, P, R, S, T, U.

The letter h, now mostly used to indicate lenition (historically sometimes inaccurately called aspiration) of a consonant, was in general not used in the oldest orthography, as lenition was instead indicated with a dot over the lenited consonant. The letters of the alphabet were traditionally named after trees, but this custom has fallen out of use.

Long vowels are marked with a grave accent (à, è, ì, ò, ù), indicated through digraphs (e.g. ao is [ɯː]) or conditioned by certain consonant environments (e.g. a u preceding a non-intervocalic nn is [uː]). Traditional spelling systems also use the acute accent on the letters á, é and ó to denote a change in vowel quality rather than length, but the reformed spellings have replaced these with the grave.[69]

Certain 18th century sources used only an acute accent along the lines of Irish, such as in the writings of Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair (1741–51) and the earliest editions (1768–90) of Duncan Ban MacIntyre.[74]

Orthography

The 1767 New Testament set the standard for Scottish Gaelic. The 1981 Scottish Examination Board recommendations for Scottish Gaelic, the Gaelic Orthographic Conventions, were adopted by most publishers and agencies, although they remain controversial among some academics, most notably Ronald Black.[75]

The quality of consonants (palatalised or non-palatalised) is indicated in writing by the vowels surrounding them. So-called "slender" consonants are palatalised while "broad" consonants are neutral or velarised. The vowels e and i are classified as slender, and a, o, and u as broad. The spelling rule known as caol ri caol agus leathann ri leathann ("slender to slender and broad to broad") requires that a word-medial consonant or consonant group followed by a written i or e be also preceded by an i or e; and similarly if followed by a, o or u be also preceded by an a, o, or u.

This rule sometimes leads to the insertion of an orthographic vowel that does not influence the pronunciation of the vowel. For example, plurals in Gaelic are often formed with the suffix -an [ən], for example, bròg [prɔːk] (shoe) / brògan [prɔːkən] (shoes). But because of the spelling rule, the suffix is spelled -ean (but pronounced the same, [ən]) after a slender consonant, as in muinntir [mɯi̯ɲtʲɪrʲ] ((a) people) / muinntirean [mɯi̯ɲtʲɪrʲən] (peoples) where the written e is purely a graphic vowel inserted to conform with the spelling rule because an i precedes the r.

Unstressed vowels omitted in speech can be omitted in informal writing. For example:

- Tha mi an dòchas. ("I hope.") > Tha mi 'n dòchas.

Gaelic orthographic rules are mostly regular; however, English sound-to-letter correspondences cannot be applied to written Gaelic.

Scots English orthographic rules have also been used at various times in Gaelic writing. Notable examples of Gaelic verse composed in this manner are the Book of the Dean of Lismore and the Fernaig manuscript.

Common words and phrases with Irish and Manx equivalents

| Scottish Gaelic | Irish | Manx Gaelic | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| sinn [ʃiːɲ] | sinn [ʃiɲ] | shin [ʃin] | we |

| aon [ɯːn] | aon [eːn] | nane [neːn] | one |

| mòr [moːɾ] | mór [mˠoːɾ] | mooar [muːɾ] | big |

| iasg [iəs̪k] | iasc [iəsk] | eeast [jiːs(t)] | fish |

| cù [kʰuː] (madadh [mat̪əɣ]) |

madra [mˠadɾə] gadhar [gˠəiɾ] (cú [kʰu:] hound) |

moddey [mɔːdə] (coo [kʰuː] hound) |

dog |

| grian [kɾʲiən] | grian [gˠɾʲiən] | grian [gridn] | sun |

| craobh [kʰɾɯːv] (crann [kʰɾaun̪ˠ] mast) |

crann [kʰɾa(u)n̪ˠ] (craobh [kʰɾeːv] branch) |

billey [biʎə] | tree |

| cadal [kʰat̪əl̪ˠ] | codail [kʰodəlʲ] | cadley [kʲadlə] | sleep (verbal noun) |

| ceann [kʲaun̪ˠ], | ceann [kʲaun̪ˠ] | kione [kʲo:n̪ˠ] | head |

| cha do dh'òl thu [xa t̪ə ɣɔːl̪ˠ u] | níor ól tú [n̠ʲi:əɾ o:l̪ˠ t̪ˠu:] | cha diu oo [xa deu u] | you did not drink |

| bha mi a' faicinn [va mi fɛçkʲɪɲ] | bhí mé ag feiceáil [vʲi: mʲe: əg fʲɛca:l̠ʲ] | va mee fakin [vɛ mə faːɣin] | I was seeing |

| slàinte [s̪l̪ˠaːɲtʲə] | sláinte /s̪l̪ˠaːɲtʲə/ | slaynt /s̪l̪ˠaːɲtʃ/ | health; cheers! (toast) |

Note: Items in brackets denote archaic or dialectal forms

See also

- Book of Deer

- Bungi creole

- Gaelic development

- Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005

- Gaelicisation

- Goidelic substrate hypothesis

- Irish language

- Comparison of Scottish Gaelic and Irish

- Gaeltacht Irish language speaking regions in Ireland.

- Official Languages Act 2003 Republic of Ireland.

- Status of the Irish language

- Languages of Scotland

- Scottish English

- Scots language (Lowland Scots)

- List of Scottish Gaelic place names

- Topics

- Gaelic medium education in Scotland

- Gaelic music

- Gaelic revival

- Gaelic road signs in Scotland

- Gàidhealtachd Scottish Gaelic speaking regions in Scotland.

- Scottish Gaelic literature

- The Mòd

- Varieties of Scottish Gaelic

References

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b c 2011 Census of Scotland, Table QS211SC. Viewed 30 May 2014.

- ^ "Census shows decline in Gaelic speakers 'slowed'". BBC News. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ "Definition of Gaelic in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ Companion to the Oxford English Dictionary, Tom McArthur, Oxford University Press, 1994

- ^ McMahon, Sean (2012). Brewer's dictionary of Irish phrase & fable. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 9781849725927.

- ^ Jones, Charles (1997). The Edinburgh history of the Scots language. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0754-9.

- ^ Chadwick, Nora Kershaw; Dyllon, Myles (1972). The Celtic Realms. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7607-4284-6.

- ^ a b Campbell, Ewan. "Were the Scots Irish?" in Antiquity No. 75 (2001). pp. 285–292.

- ^ Campbell, Saints and Sea-kings, pp. 8–15; Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, pp. 9–10; Broun, "Dál Riata"; Clancy, "Ireland"; Forsyth, "Origins", pp. 13–17.

- ^ a b Clarkson, Tim (2011). The Makers of Scotland: Picts, Romans, Gaels, and Vikings. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 978-1906566296.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Broun, "Dunkeld", Broun, "National Identity", Forsyth, "Scotland to 1100", pp. 28–32, Woolf, "Constantine II"; cf. Bannerman, "Scottish Takeover", passim, representing the "traditional" view.

- ^ a b c d Withers, Charles W. J. (1984). Gaelic in Scotland, 1698–1981. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd. ISBN 0859760979.

- ^ Dunshea, Philip M. (1 October 2013). "Druim Alban, Dorsum Britanniae– 'the Spine of Britain'". Scottish Historical Review. 92 (2): 275–289. doi:10.3366/shr.2013.0178.

- ^ a b Ó Baoill, Colm. "The Scots–Gaelic interface," in Charles Jones, ed., The Edinburgh History of the Scots Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997

- ^ Withers, Charles W. J. (1988). "The Geographical History of Gaelic in Scotland". In Colin H. Williams (ed.). Language in Geographic Context.

- ^ Mason, John (1954). "Scottish Charity Schools of the Eighteenth Century". Scottish Historical Review. 33 (115): 1–13. JSTOR 25526234.

- ^ Tanner, Marcus (2004). The Last of the Celts. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10464-2.

- ^ a b Hunter, James (1976). The Making of the Crofting Community.

- ^ Mackenzie, Donald W. (1990–92). "The Worthy Translator: How the Scottish Gaels got the Scriptures in their own Tongue". Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness. 57.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael (2002). Gaelic in Nova Scotia: An Economic, Cultural and Social Impact Study (PDF). Province of Nova Scotia. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "Endangered Languages Project - Scottish Gaelic". Endangered Languages Project. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Ross, John (19 February 2009). "'Endangered' Gaelic on map of world's dead languages". The Scotsman. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ MacAulay, Donald (1992). The Celtic Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521231272.

- ^ 2011 Census of Scotland, Table QS211SC. Viewed 23 June 2014.

- ^ Scotland's Census Results Online (SCROL), Table UV12. Viewed 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Census shows decline in Gaelic speakers 'slowed'". BBC News Online. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Census shows Gaelic declining in its heartlands". BBC News Online. 15 November 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Pupil Census Supplementary Data". The Scottish Government. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ a b O'Hanlon, Fiona (2012). Lost in transition? Celtic language revitalization in Scotland and Wales: the primary to secondary school stage (Thesis). The University of Edinburgh.

- ^ See Kenneth MacKinnon (1991) Gaelic: A Past and Future Prospect. Edinburgh: The Saltire Society.

- ^ Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005.

- ^ Williams, Colin H., Legislative Devolution and Language Regulation in the United Kingdom, Cardiff University

- ^ "Latest News – SHRC". Scottish Human Rights Commission. 12 October 2008. Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "UK Ratification of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Working Paper 10 – R.Dunbar, 2003" (PDF). Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ [1] Archived 1 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Gàidhlig". www.sqa.org.uk. SQA. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

{{cite web}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Gaelic (learners)". www.sqa.org.uk. SQA. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

{{cite web}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "An Comunn Gàidhealach - Royal National Mod : Royal National Mod". www.ancomunn.co.uk. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ "EU green light for Scots Gaelic". BBC News Online. 7 October 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ^ "Caithness councillors harden resolve against Gaelic signs". The Press and Journal. 24 October 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba - Gaelic Place-Names of Scotland - About Us". www.ainmean-aite.org. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Bumstead, J.M (2006). "Scots". Multicultural Canada. Archived from the original on 26 December 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2006.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Newton, Michael (2015). Seanchaidh na Coille / Memory-Keeper of the Forest: Anthology of Scottish Gaelic Literature of Canada. Cape Breton University Press. ISBN 978-1-77206-016-4.

- ^ Dembling, Jonathan (2006). "Gaelic in Canada: New Evidence from an Old Census". academia.edu. Dunedin Academic Press Ltd. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ a b "National Household Survey Profile, Nova Scotia, 2011". 2.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ Patten, Melanie (29 February 2016). "Rebirth of a 'sleeping' language: How N.S. is reviving its Gaelic culture". Atlantic. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ BBC Reception advice – BBC Online

- ^ a b About BBC Alba, from BBC Online

- ^ Pupils in Scotland, 2006 from scot.gov.uk. Published February 2007, Scottish Government.

- ^ Pupils in Scotland, 2008 from scot.gov.uk. Published February 2009, Scottish Government.

- ^ Pupils in Scotland, 2009 from scotland.gov.uk. Published 27 November 2009, Scottish Government.

- ^ "Scottish Government: Pupils Census, Supplementary Data". Scotland.gov.uk. 14 June 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2011 Spreadsheet published 3 February 2012 (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2012 Spreadsheet published 11 December 2012 (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2013 Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2014 Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2015 Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2016 Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pupil Census, Supplementary data 2017 Spreadsheet (Table 1.13)

- ^ Pagoeta, Mikel Morris (2001). Europe Phrasebook. Lonely Planet. p. 416. ISBN 1-86450-224-X.

- ^ O'Hanlon, Fiona (2012). Lost in transition? Celtic language revitalization in Scotland and Wales: the primary to secondary school stage (Thesis). The University of Edinburgh. p. 48.

- ^ "Gael-force wind of change in the classroom". The Scotsman. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ "Gaelic core class increasingly popular in Nova Scotia". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 26 January 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ International, Radio Canada (28 January 2015). "Gaelic language slowly gaining ground in Canada". RCI | English. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ MacLeod, Murdo (6 January 2008). "Free Church plans to scrap Gaelic communion service". The Scotsman. Edinburgh.

- ^ "Alba air Taghadh - beò à Inbhir Nis". BBC Radio nan Gàidheal. BBC. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Gaelic Orthographic Conventions" (PDF). sqa.org. Bòrd na Gàidhlig. October 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ "Catrìona Anna Nic a' Phì". BBC (in Scottish Gaelic). Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

sqawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Woulfe, Patrick. "Gaelic Surnames". www.libraryireland.com. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Cox, Richard Brìgh nam Facal (1991) Roinn nan Cànan Ceilteach ISBN 0-903204-21-5

- ^ Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair. "Smeòrach Chlann Raghnaill". www.moidart.org.uk. Archaeology Archive Moidart History. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Macbain, Alexander (1896). An Etymological Dictionary of the Gaelic Language (Digitized facsimile ed.). BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-116-77321-7.

- ^ O'Rahilly, T F, Irish Dialects Past and Present. Brown and Nolan 1932, ISBN 0-901282-55-3, p. 19

- ^ The Board of Celtic Studies Scotland (1998) Computer-Assisted Learning for Gaelic: Towards a Common Teaching Core. The orthographic conventions were revised by the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) in 2005: "Gaelic Orthographic Conventions 2005". SQA publication BB1532. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 May 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Resources

- Gillies, H. Cameron. (1896). Elements of Gaelic Grammar. Vancouver: Global Language Press (reprint 2006), ISBN 1-897367-02-3 (hardcover), ISBN 1-897367-00-7 (paperback)

- Gillies, William. (1993). "Scottish Gaelic", in Ball, Martin J. and Fife, James (eds). The Celtic Languages (Routledge Language Family Descriptions). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28080-X (paperback), p. 145–227

- Lamb, William. (2001). Scottish Gaelic. Munich: Lincom Europa, ISBN 3-89586-408-0

- MacAoidh, Garbhan. (2007). Tasgaidh – A Gaelic Thesaurus. Lulu Enterprises, N. Carolina

- McLeod, Wilson (ed.). (2006). Revitalising Gaelic in Scotland: Policy, Planning and Public Discourse. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press, ISBN 1-903765-59-5

- Robertson, Charles M. (1906–07). "Scottish Gaelic Dialects", The Celtic Review, vol 3 pp. 97–113, 223–39, 319–32.

External links

- BBC Alba – Scottish Gaelic language, music and news

- Bòrd na Gàidhlig – Scotland's Gaelic-language Board

- Gaelic Resource Database – founded by Comhairle nan Eilean Siar

- Scottish Gaelic Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Faclair Dwelly air Loidhne – Dwelly's Gaelic dictionary online

- Gàidhlig air an Lìon – Sabhal Mòr Ostaig's links to pages in and about Scottish Gaelic

- Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies – Census information from 1881 to the present, 27 volumes covering all Gaelic-speaking regions

- Goidelic Dictionaries

- Pàrlamaid na h-Alba: Gàidhlig – Scottish Parliament site in Gaelic

- Gaelic psalms at Back Free Church, Isle Of Lewis (6:29)

- Sermons in Scottish Gaelic, Back Free Church, Back, Isle of Lewis

- Comhairle na Gàidhlig – The Gaelic Council of Nova Scotia (Canada)

- Comunn Gàidhlig Bhancoubhair – The Gaelic Society of Vancouver (Canada)

- DASG - The Digital Archive of Scottish Gaelic

- An Comunn's website

- Nova Scotia Office of Gaelic Affairs