William McKinley: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by Flamethrower159 (talk) to last revision by Coemgenus (HG) |

|||

| Line 341: | Line 341: | ||

{{Portal box|Biography|United States Army|American Civil War}} |

{{Portal box|Biography|United States Army|American Civil War}} |

||

{{Sister project links|s=Author:William McKinley}} |

{{Sister project links|s=Author:William McKinley}} |

||

www.fill-my-wet-hole-with-your-black-log.com |

|||

* [http://www.millercenter.virginia.edu/index.php/academic/americanpresident/mckinley Essay on William McKinley and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs] |

* [http://www.millercenter.virginia.edu/index.php/academic/americanpresident/mckinley Essay on William McKinley and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs] |

||

* [http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/presidents/mckinley/index.html William McKinley: A Resource Guide] from the Library of Congress |

* [http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/presidents/mckinley/index.html William McKinley: A Resource Guide] from the Library of Congress |

||

Revision as of 17:52, 2 March 2012

William McKinley | |

|---|---|

| |

| 25th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1897 – September 14, 1901 | |

| Vice President | Garret Hobart (1897–1899) vacant (1899–1901) Theodore Roosevelt (1901) |

| Preceded by | Grover Cleveland |

| Succeeded by | Theodore Roosevelt |

| 39th Governor of Ohio | |

| In office January 11, 1892 – January 13, 1896 | |

| Lieutenant | Andrew Harris |

| Preceded by | James Campbell |

| Succeeded by | Asa Bushnell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 29, 1843 Niles, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | September 14, 1901 (aged 58) Buffalo, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Ida Saxton (1871–1901, survived as widow) |

| Children | Katherine, Ida (both died in early childhood) |

| Alma mater | Allegheny College, Albany Law School |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States Union |

| Branch/service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Captain Brevet major |

| Unit | 23rd Ohio Infantry |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

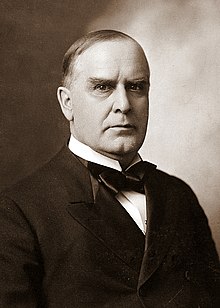

William McKinley (born William McKinley, Jr.; January 29, 1843 – September 14, 1901) was the 25th President of the United States, serving from March 4, 1897 until his death. The third American president to be assassinated, McKinley led the nation to victory in the Spanish-American War, raised the protective tariff to promote American industry and high wages, and placed the nation on the gold standard in a rejection of inflationary policies. His victory in the 1896 presidential election, was a realigning election that marked the transition from the Third Party System to the Fourth Party System (or "Progressive Era") and began a period of over a third of a century dominated by the Republican Party and McKinley's political principles.

McKinley was born in northeastern Ohio in 1843. After service in the Civil War as major he moved to Canton, Ohio, where he practiced law. In 1876, he was elected to Congress, where he became the party's leading expert on the protective tariff, which he promised would bring prosperity and high paying jobs, as well as a rich domestic market for farmers. He designed the 1890 McKinley Tariff, which provided a target for Democratic party, which won sweeping national victories in 1890 and 1892 on the tariff issue. He was defeated in 1890, but was elected governor in 1891 and 1893. As the Republican candidate in the 1896 presidential election, opposing Democrat William Jennings Bryan, he promoted pluralism among ethnic groups. His campaign, designed by Mark Hanna, introduced revolutionary advertising techniques, and defeated the crusade of archrival Bryan.

McKinley presided over a return to prosperity after the economic Panic of 1893, with the gold standard as a keystone. He hoped to persuade Spain to free rebellious Cuba without conflict, but when negotiation failed, led the nation in the Spanish-American War of 1898. The U.S. victory was quick and decisive, as the weak Spanish fleets were sunk and both Cuba and the Philippines were captured within a few months. As a result of the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines were annexed by the United States as unincorporated territories, and U.S occupation of Cuba began; this occurred in the face of opposition from Democrats and anti-imperialists who feared a loss of republican values. McKinley also procured the annexation the independent Republic of Hawaii in 1898, with all its inhabitants becoming American citizens.

McKinley was reelected in the 1900 presidential election following another intense campaign against Bryan, which focused on foreign policy and the return of prosperity. President McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist in September 1901 in Buffalo, and was succeeded by his Vice President, Theodore Roosevelt. Although McKinley's presidency was cut short, and he is to some extent overshadowed by his successor, he is often viewed by scholars as the first modern president.

Early life and family

William McKinley, Jr., was born in 1843 in Niles, Ohio, the seventh child of William, and Nancy (Allison) McKinley.[1] The McKinleys were of English and Scotch-Irish descent and had settled in western Pennsylvania in the 18th century. There, the elder McKinley was born in Pine Township.[1] The family moved to Ohio when the senior McKinley was a boy, settling in New Lisbon (now Lisbon). There he met and married McKinley's mother, Nancy Allison, in 1829.[1] Nancy Allison's ancestors were mostly English and were among Pennsylvania's earliest settlers.[2] The family trade on both sides was iron-making, and McKinley senior operated foundries in New Lisbon, Niles, Poland, and finally Canton, Ohio.[3]

The McKinley household was, like many from Ohio's Western Reserve, steeped in Whiggish and abolitionist sentiment.[4] Religiously, the family was staunchly Methodist and young William followed in that tradition, becoming a member of the local Methodist church at the age of sixteen.[5] He would remain a pious Methodist for his entire life.[6] In 1852, the family moved from Niles to Poland so that their children could attend the school there, which they judged better than the schools near Niles.[7] McKinley was a diligent student and participated in debating societies.[7] Graduating in 1859, he enrolled the following year at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania.[7] He remained at Allegheny for only one year, returning home in 1860 after becoming ill and depressed.[8] Although his health recovered, family finances declined and McKinley was unable to return to Allegheny, first working as a postal clerk and later taking a job teaching at a school near Poland.[9]

Civil War

Western Virginia and Antietam

When the southern states seceded from the Union and the American Civil War began, thousands of men in Ohio volunteered for service.[10] Among them were McKinley and his cousin, William McKinley Osbourne, who enlisted as privates in the newly formed Poland Guards in June 1861.[11] The men soon left for Columbus where they were consolidated with other small units to form the 23rd Ohio Infantry.[12] The 23rd Ohio contained an unusual number of men who would rise to post-war prominence, including two presidents (McKinley and Rutherford B. Hayes), a Supreme Court justice (Stanley Matthews), and two lieutenant-governors of Ohio (Robert P. Kennedy and William C. Lyon).[13] The men were unhappy to learn that, unlike Ohio's earlier volunteer regiments, they would not be permitted to elect their officers; they would be designated by Ohio's governor, William Dennison.[12] Dennison appointed Colonel William Rosecrans as the commander of the regiment, and the men soon began training at Camp Chase on the outskirts of Columbus.[12] McKinley quickly took to the soldier's life and wrote a series of letters to his hometown newspaper extolling the army and the Union cause.[14] Delays in issuance of uniforms and weapons soon brought the men again into conflict with their officers, but Major Hayes convinced them to accept what the government has issued them; his style in dealing with the men impressed McKinley, beginning an association and friendship that would last until Hayes' death in 1893.[15]

After a month of training, McKinley and the 23rd Ohio set out for western Virginia (today part of West Virginia) in July 1861 as a part of the Kanawha Division.[16] Rosecrans had been promoted, so the 23rd Ohio was now led by Colonel Eliakim P. Scammon. McKinley initially thought Scammon was a martinet, but when the regiment finally saw battle, he came to appreciate the value of their relentless drilling.[17] Except for encounters with bushwhackers, they passed the next few months out of contact with the enemy until September, when the regiment encountered Confederates at Carnifex Ferry in present-day West Virginia and drove them back.[18] Three days after the battle, McKinley was assigned to duty in the brigade quartermaster office, where he carried out clerical duties as well as working to supply the regiment.[19] In November, the regiment moved deeper into western Virginia, where they entered winter quarters near Fayetteville.[20] McKinley spent the winter filling the duties of a commissary sergeant who was ill, and in April 1862 he was promoted to that rank.[21] The regiment resumed its advance that spring with Hayes in command (Scammon now led the brigade) and fought several minor engagements against the rebel forces.[22]

That September, McKinley's regiment was called east to reinforce General John Pope's Army of Virginia at the Second Battle of Bull Run.[23] Delayed in passing through Washington, D.C., the 23rd Ohio did not arrive in time for the battle, but joined the Army of the Potomac as it hurried north to cut off Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, which was advancing into Maryland.[23] Marching north, the 23rd was the lead regiment to encounter the Confederates at the Battle of South Mountain on September 14.[24] After severe losses, they drove back the Confederates and continued to Sharpsburg, Maryland, where they engaged Lee's army at the Battle of Antietam.[25] The 23rd was also in the thick of the fighting at Antietam, and McKinley himself came under heavy fire when bringing rations to the men on the line.[25][note 1] McKinley's regiment again suffered many casualties, but the Army of the Potomac was victorious and the Confederates retreated into Virginia.[25] After a brief pursuit of some rebel cavalry, the regiment was detached from the Army of the Potomac and returned by train to western Virginia.[26]

Shenandoah Valley and promotion

While the regiment went into winter quarters near Charleston, Virginia (present-day West Virginia), McKinley was ordered back to Ohio with some other sergeants to recruit fresh troops.[27] When they arrived in Columbus, Governor David Tod surprised McKinley with a promotion to second lieutenant in recognition of his service at Antietam.[27] After a brief visit home, McKinley finished his recruiting and returned to the regiment.[28] They saw little action until July 1863, when the division skirmished with John Hunt Morgan's cavalry at the Battle of Buffington Island.[29] Returning to Charleston for the rest of the summer, McKinley spent some time in the town courting a local girl until Hayes banned his officers from such fraternization.[30] Early in 1864, the Army command structure in West Virginia was reorganized, and the division was assigned to George Crook's Army of West Virginia.[31] They soon resumed the offensive, marching into southwestern Virginia to destroy Confederate salt and lead mines there.[31] On May 9, the army engaged Confederate troops at Cloyd's Mountain, where the men charged the enemy entrenchments and drove the rebels from the field.[31] McKinley later said the combat there was "as desperate as any witnessed during the war."[31] Following the rout, the Union forces destroyed Confederate supplies and skirmished with the enemy again successfully.[31]

McKinley and his regiment moved to the Shenandoah Valley for the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Crook's corps was attached to Major General David Hunter's Army of the Shenandoah and soon back in contact with Confederate forces, capturing Lexington, Virginia on June 11.[32] They continued south toward Lynchburg, tearing up railroad track as they advanced.[32] Hunter believed the troops at Lynchburg were too powerful, however, and the brigade returned to West Virginia.[32] Before the army could make another attempt, Confederate General Jubal Early's raid into Maryland forced their recall to the north.[33] Early's army surprised them at Kernstown on July 24, where McKinley came under heavy fire and the army was defeated.[34] After the battle, he was promoted to captain.[35] Retreating into Maryland, the army was reorganized again, with Major General Philip Sheridan replacing Hunter, and McKinley was transferred to General Crook's staff.[36] By August, Early was retreating down the valley, with Sheridan's army in pursuit.[37] They fended off a Confederate assault at Berryville, where McKinley had a horse shot out from under him, and advanced to Opequon Creek, where they broke the enemy lines and pursued them farther south.[38] They followed up the victory with another at Fisher's Hill on September 22, and were engaged once more at Cedar Creek on October 19.[39] After initially falling back from the Confederate advance, McKinley help to rally the troops and turn the tide of the battle.[39]

After Cedar Creek, the army stayed in the vicinity through election day, when McKinley cast his first presidential ballot for Abraham Lincoln.[39] The next day, the moved north up the valley into winter quarters near Kernstown.[39] The year 1865 opened with Union forces across the country advancing, and McKinley and his fellow soldiers were in good spirits.[40] That changed in February when Crook was captured by Confederate raiders.[41] Crook's capture added to the confusion as the army was reorganized for the spring campaign, and McKinley found himself serving on the staffs of four different generals over the next fifteen days—Crook, John D. Stevenson, Samuel S. Carroll, and Winfield S. Hancock.[41] Finally assigned to Carroll's staff again, McKinley acted as the general's only adjutant.[42] Lee's army surrendered to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant a few days later, and the war was nearly at an end. McKinley found the time to join a Freemason lodge in Winchester, Virginia before he and Carroll were transferred to Hancock's First Veterans Corps in Washington.[43] Just before the war's end, McKinley received his final promotion, a brevet commission as major.[44] In July, the Veterans Corps was mustered out of service, and McKinley and Carroll were relieved of their duties.[44] Carroll and Hancock encouraged McKinley to apply for a position in the peacetime army, but he declined and returned to Ohio the following month.[44]

Legal career and marriage

After the war ended in 1865, McKinley decided on a career in the law and began studying in the office of Charles Glidden, an attorney in Poland, Ohio.[45] The following year, he continued his studies by attending Albany Law School in New York.[46] After studying there for a year, McKinley returned home and was admitted to the bar in Warren, Ohio in March 1867.[46] That same year, he moved to Canton, the county seat, and set up a small office.[46] He soon formed a partnership with George W. Belden, an experienced lawyer and former judge.[47] McKinley's practice was successful enough for him to buy a block of buildings on Main Street in Canton, which would provide him with small but consistent rental income for decades to come.[47] When Hayes was nominated for governor in 1867, McKinley spoke on his behalf around Stark County, his first foray into politics.[48] The county was closely divided between Democrats and Republicans but Hayes carried it that year.[48] In 1869, McKinley ran for the office of prosecuting attorney of Stark County, an office usually held by Democrats at the time, and was unexpectedly elected.[49] When McKinley ran for re-election in 1871, the Democrats nominated William A. Lynch, a prominent local lawyer, and McKinley was defeated by 143 votes.[49]

McKinley's social life was developing at the same time as his professional life, as he began courting Ida Saxton, the daughter of a prominent Canton family.[49] They were married on January 25, 1871 in the newly built First Presbyterian Church of Canton, although Ida soon joined her husband's Methodist church.[50] Their first child, Katherine, arrived on Christmas Day 1871.[50] A second daughter, Ida, was born in 1873, but died the same year.[50] McKinley's wife descended into a deep depression at her baby's death and her health, never robust, grew worse.[50] Two years later, in 1875, Katherine died of typhoid fever; Ida never recovered from her daughters' deaths, and the McKinleys never had any more children.[50] She developed epilepsy around the same time and hated for McKinley to leave her side.[50] He remained a devoted husband and tended to his wife's medical and emotional needs for the rest of his life.[50]

Ida insisted that McKinley continue his increasingly influential career in law and politics.[51] He attended the state Republican convention that nominated Hayes for a third term as governor in 1875, and campaigned again for his old friend in the election that fall.[51] The next year, McKinley undertook a high-profile case defending a group of coal miners arrested for rioting after a clash with strikebreakers.[52] Lynch, McKinley's opponent in the 1871 election, and his partner, William R. Day, were the opposing counsel, and the mine owners included Mark Hanna, a Cleveland businessman.[52] Taking the case pro bono, he was successful in getting all but one of the miners acquitted.[52] The case raised McKinley's standing among laborers, a crucial part of the Stark County electorate, and also introduced him to Hanna, who would become his strongest backer in years to come.[52]

McKinley's good standing with labor became useful that year as he campaigned for the Republican nomination for Ohio's 17th congressional district.[53] Delegates to the county conventions thought he could attract blue-collar voters, and in August 1876, McKinley was nominated.[53] By that time Hayes had been nominated for President, and McKinley campaigned for him while running his own congressional campaign.[54] Both were successful. McKinley, campaigning mostly on his support for a protective tariff, defeated the Democratic nominee, Levi L. Lamborn, by 3300 votes.[54]

Congressional career

McKinley first took his congressional seat in October 1877, when President Hayes summoned Congress into special session. With the Republicans in the minority, McKinley was given unimportant committee assignments, which he undertook conscientiously. The McKinleys paid few social calls in Washington because of Ida's health; [55] their closest friends there were President and Lucy Hayes. In later years, Ida McKinley (who always loved children) was fond of telling friends of two weeks spent with her husband at the Executive Mansion (as the White House was still known) supervising the Hayes children while their parents were away on a trip.[56]

The friendship with Hayes did McKinley little good on Capitol Hill; the President was not well-regarded by many leaders there.[57] The young congressman broke with Hayes on the question of the currency, but it did not affect their friendship.[58] The United States had effectively been placed on the gold standard by the Coinage Act of 1873; when silver prices dropped significantly, many sought to make silver again a legal tender, equally with gold. Such a course would be inflationary; advocates argued that the economic benefits of the increased money supply would be worth the inflation; opponents warned that "free silver" would not bring the promised benefits and would harm the United States in international trade.[59] McKinley voted for the Bland-Allison Act of 1878, which mandated large government purchases of silver for striking into money, and also joined the large majorities in each house that overrode Hayes' veto of the legislation. In so doing, McKinley voted against the position of the House Republican leader, his fellow Ohioan and friend, James Garfield. Later, in the 1896 presidential campaign, McKinley became a strong advocate of the gold standard, a change Hanna explained, "He did not pretend to be a doctor of finance and followed the popular trend of that time."[60]

From his first term in Congress, McKinley was a strong advocate of protective tariffs. The primary purposes of such imposts was not to raise revenue, but to allow American manufacturing to develop by giving it a price advantage in the domestic market over foreign competitors. McKinley biographer Margaret Leech noted that Canton had become prosperous as a center for the manufacture of farm equipment because of protection. He introduced and supported bills which raised protective tariffs, and opposed those which lowered them or imposed tariffs simply to raise revenue. This was a popular stance—Leech noted the unpopularity of foreigners (especially the British) in America at the time: "Though McKinley was too reasonable and temperate to become a demagogue, his diatribes against foreign importations, and against the products of British industry in particular, were appeals to popular prejudice."[61] Garfield's election as president in 1880 created a vacancy on the House Ways and Means Committee; McKinley was selected to fill it, placing him on the most powerful committee after only two terms.[62] In 1889, with the Republicans in the majority, McKinley sought election as Speaker of the House. He failed to gain the post, which went to Thomas B. Reed of Maine; however Speaker Reed appointed McKinley chairman of the Ways and Means Committee. The Ohioan guided through Congress the McKinley Tariff of 1890, which though heavily amended in the Senate, imposed a number of protective tariffs on foreign goods.[63]

McKinley increasingly became a significant figure in national politics. In 1880, he served a brief term as Ohio's representative on the Republican National Committee. In 1884, he was elected a delegate to that year's Republican convention, where he served as chair of the Committee on Resolutions and won plaudits for his handling of the convention when called upon to preside. By 1886, McKinley, Senator John Sherman, and Governor Joseph B. Foraker were considered the leaders of the Republican party in Ohio.[64] Sherman, who had helped to found the Republican Party, ran three times for the Republican nomination for president in the 1880s, each time failing,[65] while Foraker began a meteoric rise in Ohio politics early in the decade. Hanna, once he entered public affairs as a political manager and generous contributor, was a supporter of Sherman's ambitions, as well as those of Foraker. The latter relationship broke off at the 1888 Republican National Convention, to which McKinley, Foraker, and Hanna were all delegates supporting Sherman. Convinced Sherman could not win, Foraker threw his support to the unsuccessful Republican 1884 presidential nominee, Maine Senator James G. Blaine. When Blaine stated he was not a candidate, Foraker backed the ultimately successful candidate, Indiana Governor Benjamin Harrison, who was elected president. In the bitterness which followed the convention, Hanna abandoned Foraker, and for the remainder of McKinley's lifetime, the Ohio Republican Party was divided into two factions, one aligned around McKinley, Sherman, and Hanna and the other around Foraker.[66] Hanna had come to admire McKinley, and in the years that followed, became a close adviser to him.[67]

Recognizing McKinley's potential, the Democrats, whenever they controlled the Ohio legislature, sought to redistrict him out of office.[68] In 1878, McKinley faced election in a redrawn 17th district; he won anyway, causing Hayes to exult, "Oh, the good luck of McKinley! He was gerrymandered out and then beat the gerrymander! We enjoyed it as much as he did."[69] After the 1882 election, McKinley was unseated on an election contest by a near party-line House vote.[70] Out of office, he was briefly depressed by the setback, but soon vowed to run again. The Democrats again redistricted Stark County for the 1884 election; McKinley was returned to Congress anyway.[71] For 1890, the Democrats gerrymandered McKinley one final time, placing Stark County in the same district as one of the strongest pro-Democrat counties, Holmes. Damaged by the redistricting and voter resentment over the tariff that had caused prices to rise, the congressman was projected to lose by 3,000 votes, based on past votes. McKinley was defeated, though only by 300 votes.[72]

Governor of Ohio

Even before McKinley completed his term in Congress, he met with a delegation of Ohioans urging him to run for governor. Governor James E. Campbell, a Democrat, who had defeated Foraker in 1889, was to seek re-election in 1891. McKinley, who was already ambitious to be president, considered waiting until 1892 and then seeking a return to Congress, but ultimately decided to run for governor. The Ohio Republican party remained divided, but McKinley quietly arranged for Foraker to nominate him at the 1891 state Republican convention, which chose McKinley by acclamation. The former congressman spent much of the second half of 1891 campaigning against Campbell, beginning in his hometown of Niles. Hanna, however, was little seen in the campaign; he spent much of his time raising funds for the election of legislators pledged to vote for Sherman in the 1892 senatorial election.[73][74][note 2] McKinley won the 1891 election by some 20,000 votes;[75] the following January, Sherman, with considerable assistance from Hanna, turned back a challenge by Foraker to win another term in the Senate.[76]

Ohio's governor had relatively little power—for example, he could recommend legislation, but not veto it—but with Ohio a key swing state, its governor was a major figure in national politics, consulted by congressmen and Cabinet officials.[77] Although McKinley believed that the health of the nation depended on that of business, he was evenhanded in dealing with labor,[78] procuring legislation to set up an arbitration board at which work disputes could be settled, and obtaining passage of a law to fine employers who fired workers for belonging to a union. This led to accusations against Governor McKinley that he went too far in accommodating labor; he retorted, "My whole public life has been devoted to the advocacy of a system which gave men employment and kept the shops running."[79]

President Harrison had proven unpopular; there were divisions even within the Republican party as the year 1892 began and Harrison began his re-election drive. Although no declared candidate emerged to oppose Harrison, many Republicans were ready to dump the President from the ticket if an alternative emerged. Among the possible candidates spoken of were the aging Blaine, Speaker Reed, and McKinley. Fearing that the Ohio governor would emerge as a candidate, Harrison's managers arranged for McKinley to be permanent chairman of the convention in Minneapolis, requiring him to play a public, neutral role. Hanna established an unofficial McKinley headquarters near the convention hall, though no active effort was made to covert delegates to McKinley's cause. Although McKinley objected to delegate votes being cast for him, he nevertheless finished third, behind the renominated Harrison, and behind Blaine, who had sent word he did not want to be considered. According to Hanna biographer William T. Horner,

[McKinley was] clearly building a foundation for the future, beyond 1892. McKinley was certainly ambitious, but he was also a very skilled politician. He knew an open attempt to win the nomination in 1892—which Hanna's canvassing told him would fail—would hurt him in future campaigns. Even if he thought it was possible to wrest the nomination from Harrison, there was a strong feeling that no Republican could win the general election ... Much of McKinley's public performance at the convention in Minneapolis was a show of downplaying the efforts of Hanna and his other boosters.[80]

Although McKinley campaigned loyally for the Republican ticket, Harrison was defeated by former President Cleveland in the November election. In the wake of Cleveland's victory, McKinley was seen by some as the likely Republican candidate in 1896.[81]

In 1893, hard times struck the nation with the Panic of 1893. A businessman in Youngstown, Robert Walker, had lent money to McKinley in their younger days; in gratitude, McKinley had often guaranteed Walker's business notes. The governor had never kept track of what he was signing; he believed Walker a sound businessman. In fact Walker had deceived McKinley, telling him that new notes were actually renewals of matured ones. Walker was ruined by the recession; McKinley was called upon for repayment. The normally composed McKinley raged on the train to Youngstown about what he would say to Walker; when the two men met, the governor expressed no anger, but was gentle and encouraging.[82] The total owed was over $100,000 and a despairing McKinley initially proposed to resign as governor and earn the money as an attorney.[83] Instead, McKinley's wealthy supporters, including Hanna and Chicago publisher H. H. Kohlsaat became trustees of a fund from which the notes would be paid. Both William and Ida McKinley placed their property in the hands of the fund's trustees (who included Hanna and Kohlsaat), and the supporters raised and contributed a substantial sum of money. All of the couple's property was returned to them, and when McKinley, who had promised eventual repayment, asked for the list of contributors, it was refused him. Many people who had suffered in the hard times sympathized with McKinley, whose popularity grew.[83] He was easily re-elected in November 1893, receiving the largest percentage of the vote of any Ohio governor since the Civil War.[84]

In 1894, the economic upset led to strikes among coal miners in the Hocking Valley in southern Ohio. When owners brought in strikebreakers from Virginia and West Virginia, the miners responded by destroying a railroad trestle. The local sheriff wired McKinley using alarming terms, and the governor responded by sending a large force of militia, correctly assuming, based on his Civil War experience, that an overwhelming force would make violence unlikely. In January 1895, upon learning that many miners were starving, he made a statewide appeal for funds, and quickly sent trains loaded with food and other necessities to relieve them. McKinley was criticized by conservatives for his actions towards the miners; the Cleveland Plain Dealer noted that "bridge burners, trainwreckers, and highwaymen are usually shot on sight".[85] However, McKinley biographer Kevin Phillips noted that although McKinley was later caricatured as a puppet of heartless capitalists, "the reality was altogether different."[85]

McKinley campaigned widely for Republicans in the 1894 midterm congressional elections; many party candidates in districts where he spoke were successful. His political efforts in Ohio were rewarded by the election of a Republican successor, Asa Bushnell in November 1895, and a Republican legislature that elected Foraker to the Senate. McKinley supported Foraker for Senate and Bushnell (who was of Foraker's faction) for governor; in return, the new senator-elect agreed to back McKinley's presidential ambitions. With party peace in Ohio assured, McKinley turned to the national arena.[86]

Election of 1896

Obtaining the nomination

It is unclear when William McKinley began to seriously prepare a run for president. As Phillips noted "no documents, no diaries, no confidential letters to Mark Hanna (or anyone else) contain his secret hopes or veiled stratagems."[87] From its earliest days, McKinley's preparations had the participation of Hanna: according to Horner, "what is certainly true that in 1888 the two men began to develop a close working relationship that helped put McKinley in the White House."[88] Sherman did not run again after 1888, and so Hanna could support McKinley wholeheartedly.[89] Indeed, not only was McKinley preparing to lead his party to the presidency, his party was preparing to be led by him. Phillips noted that with with Blaine dead only months after the 1892 convention, and Harrison discredited by his defeat by Grover Cleveland, the party was looking for a new leader to lead it to future success. Phillips argued that the dissenting votes against Harrison's renomination in 1892 "were the party's fond wave to the past—to its "Plumed Knight", James G. Blaine—and its nod to better prospects under McKinley".[89][90]

Backed by Hanna's money and organizational skills, McKinley quietly built support for a presidential bid through 1895 and early 1896. When other contenders, such as Speaker Reed and Iowa Senator William B. Allison sent agents outside their states to organize Republicans in support of their candidacies, they found that Hanna's agents had preceded them. According to historian Stanley Jones in his study of the 1896 election, "Another feature common to the Reed and Allison campaigns was their failure to make headway against the tide which was running toward McKinley. In fact, both campaigns from the moment they were launched were in retreat. The calm confidence with which each candidate claimed the support of his own section [of the country] soon gave way to ... bitter accusations that Hanna by winning support for McKinley in their sections had violated the rules of the game".[91]

Hanna, on McKinley's behalf, met with the eastern Republican political bosses, such as Senators Thomas Platt of New York and Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania, who were willing to guarantee McKinley's nomination in exchange for promises regarding patronage and offices. McKinley, however, was determined to obtain the nomination without making deals, and Hanna accepted that decision.[92] Many of their early efforts were focused on the South—Hanna obtained a vacation home in southern Georgia where McKinley visited and met with Republican politicians from the region. McKinley needed 453½ delegate votes to gain the nomination; he gained nearly half that number from the South and border states. Lamented Platt in his memoirs, "[Hanna] had the South practically solid before some of us awakened."[93]

The bosses still hoped to deny McKinley a first-ballot majority at the convention by boosting support for local favorite son candidates such as Quay, New York Governor (and former vice president) Levi P. Morton, and Illinois Senator Shelby Cullom. Delegate-rich Illinois proved a crucial battleground, as McKinley supporters, such as Chicago businessman (and future vice president) Charles G. Dawes, sought to elect delegates pledged to vote for McKinley at the national convention in St. Louis. Cullom proved unable to stand against McKinley despite the support of local Republican machines; at the state convention at the end of April, McKinley completed a near-sweep of Illinois' delegates.[94] Former President Harrison had been deemed a possible contender if he entered the race; when Harrison made it known he would not seek a third nomination, the McKinley organization took control of Indiana with a speed Harrison privately found unseemly. Morton operatives who journeyed to Indiana sent word back that they had found the state alive for McKinley.[95] Wyoming Senator Francis Warren wrote, "The politicians are making a hard fight against him, but if the masses could speak, McKinley is the choice of at least 75% of the entire [body of] Republican voters in the Union".[96]

By the time the national convention began in St. Louis on June 16, 1896, McKinley had an ample majority of delegates. The former governor, who remained in Canton, followed events at the convention closely by telephone, and was able to hear part of Foraker's speech nominating him over the line. Ohio's vote gave McKinley the nomination, which he celebrated by hugging his wife and mother as his friends fled the house, anticipating the first of many crowds which would gather at the Republican candidate's home. Thousands of partisans came from Canton and surrounding towns that evening to hear McKinley speak from his front porch. The convention nominated Republican National Committee vice chairman Garret Hobart of New Jersey for vice president, a choice actually made, by most accounts, by Hanna. Hobart, a wealthy lawyer, businessman, and former state legislator, was not widely known, but as Hanna biographer Herbert Croly pointed out "if he did little to strengthen the ticket he did nothing to weaken it".[97][98]

General election campaign

Prior to the Republican convention, McKinley had been a "straddle bug" on the currency question, favoring moderate positions on silver such as accomplishing bimetallism by international agreement. In the final days before the convention, McKinley sought advice about what the currency plank in the Republican party platform should say. After hearing from politicians, and from advisors such as Hanna, Kohlsaat, and Cleveland businessman Myron Herrick, McKinley decided that the platform should endorse the gold standard, though it should allow for bimetallism by international agreement. Adoption of the platform caused some Republican delegates, led by Colorado Senator Henry M. Teller to walk out of the convention. However, compared with the Democrats, Republican divisions on the issue were small, especially as McKinley promised future concessions to silver advocates.[99][100][101]

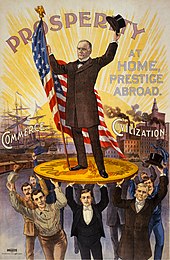

The poor economic times had continued, and strengthened the hand of forces for free silver. The issue bitterly divided the Democratic Party; President Cleveland firmly supported the gold standard; but an increasing number of Democrats did not. Discontent with Cleveland led silver advocates on a successful insurgency, taking over the Democratic Party in 1896. They did not attempt to dictate the choice of presidential candidate, as any nominee would have to be acceptable to silver forces; former Congressman Richard Bland, originator of the Bland-Allison Act, was deemed the frontrunner.[102] However, another former representative, William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska stampeded the Democratic convention with his Cross of Gold speech.[103] Bryan's speech, in which he championed the concerns of the common man, and his subsequent nomination for president shocked Eastern financiers—they considered his program of inflationary money akin to revolution. Although initially hesitant to give to McKinley's campaign when approached by Hanna, they eventually contributed millions of dollars. This money went to print over 200 million books and pamphlets advocating the Republican position on the silver and tariff questions, for paid speakers to travel and advocate that dogma, and even for the nation's first campaign film, showing McKinley giving a speech.[104][105]

Bryan's campaign had less money than his rival's; with his eloquence one of his major assets in the race, he decided on a whistle-stop political tour by train on a then-unprecedented scale. While presidential candidates had travelled and given speeches before, it was then considered somewhat undignified—candidates wished to be seen as George Washington, called forth to the presidency, rather than as a pandering office-seeker. In any event, few Democratic voters had the money to travel to Bryan's Nebraska home to hear him speak.[106] Once Bryan's plans became clear, Hanna urged McKinley to match Bryan's tour with one of his own, the candidate declined on the ground that the Democrat was a better stump speaker, "I might just as well set up a trapeze on my front lawn and compete with some professional athlete as go out speaking against Bryan. I have to think when I speak."[107] Instead of going to the people, McKinley would remain at home in Canton and allow the people to come to him; according to historian R. Hal Williams in his book on the 1896 election, "it was, as it turned out, a brilliant strategy. McKinley's 'Front Porch Campaign' became a legend in American political history."[107]

McKinley made himself available to the public every day except Sunday, receiving delegations from the front porch of his home. He did this continuously from July to November, excepting three days in July when he fulfilled nonpolitical speaking engagements elsewhere in Ohio, and a weekend of rest in late August. The railroads subsidized the delegations with low excursion rates—the pro-silver Cleveland Plain Dealer disgustedly stated that going to Canton had been made "cheaper than staying at home".[108][109] Canton in the summer and fall of 1896 had a daily parade, as delegations (usually of Republican partisans, though Democrats, including Bryan, also visited) trooped through the streets from the railroad station to McKinley's home on North Market Street, ceremoniously escorted by local militia and passing under an arch with McKinley's portrait. If McKinley was still dealing with the previous delegation, they were halted on the far side of the arch from McKinley's home, and were offered their choice of beer or lemonade to refresh them as they waited. Delegations were accompanied on their march by bands, playing music tailored to their industry or state. Once outside the McKinley home, they crowded close to the front porch—from which they surreptitiously whittled souvenirs—as their spokesman addressed McKinley. The candidate then responded, speaking on campaign issues in a speech molded to suit the interest of the delegation. The speeches were carefully scripted to avoid extemporaneous remarks; even the spokesman's remarks were approved by McKinley or a representative. This was done as the candidate feared an offhand comment by another that might rebound on him, as had happened to Blaine in 1884 (an unfortunate remark by a minister at a Blaine event was deemed by some crucial in losing him the election).[108][110][111]

There was intense public interest in the campaign, and McKinley's workers did their best to accommodate it; the campaign had special departments for black voters, though most in the South were disenfranchised, and for women, who could only vote in Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.[112] Jones wrote,

For the people it was a campaign of study and analysis, of exhortation and conviction—a campaign of search for economic and political truth. Pamphlets tumbled from the presses, to be read, reread, studied, debated, to become guides to economic thought and political action. They were printed and distributed by the million ... but the people hankered for more. Favorite pamphlets became dog-eared, grimy, fell apart as their owners laboriously restudied their arguments and quoted from them in public and private debate.[113]

Most newspapers, even those Democratic in perspective, refused to support Bryan, the major exception being the New York Journal, controlled by William Randolph Hearst. The publishing magnate directed Journal staff to cover Bryan favorably, and McKinley less so.[114] As McKinley was widely admired as a good man and husband, even among those who disagreed with him politically, Hanna proved an easier target.[115] In reporting and through the cartoons of Homer Davenport, Hanna was viciously characterized as a plutocrat, often seen trampling on labor. McKinley was drawn as a child, easily controlled by the businessmen who had bought him by buying up the Walker notes, which had nearly ruined him in 1893. Journal reporter Alfred Henry Lewis put it vividly:

Bucked and gagged behind doors, barred against all visiting questions, McKinley is left in Canton. Hanna owns McKinley and what was the price? One hundred and eighteen thousand dollars worth of McKinley-Walker notes, paid off and up by the great McKinley syndicate. Where are the notes? Ask Hanna, ask Herrick, ask any of them. They won't answer, but they know. They are not cancelled, those notes, they exist in force and effect. Hanna, as he strutted through the Southern Hotel today, could have begun suit against his candidate for $118,000 and interest thereon, and taken judgment.[116]

Even today, these depictions still color the images of Hanna and McKinley: one as a heartless businessman, the other as a creature of Hanna and others of his ilk. Although recent scholarship, such as by McKinley biographer Lewis L. Gould, has attempted to dispel these myths, they still persist.[117]

The battleground proved to be the Midwest—the South and most of the West were conceded to Bryan—and the Democrat spent much of his time in those crucial states.[118][119] The Northeast was considered most likely safe for McKinley after the early-voting states of Maine and Vermont supported him in September.[120] By then, it was clear that public support for silver had receded, and McKinley began to emphasize the tariff issue. By the end of September, the Republicans had discontinued printing material on the silver issue, and were entirely concentrating on the tariff question.[121] On November 3, 1896, the voters had their say in most of the nation. McKinley won the entire Northeast and Midwest; he won 51% of the vote and an ample majority in the Electoral College. Bryan had concentrated entirely on the silver issue, and had not appealed to urban workers. Voters in cities supported McKinley; the only city of more than 100,000 population to be carried by Bryan was Denver, Colorado.[122]

The 1896 presidential election is often seen as a realigning election, in which McKinley's view of a stronger central government building US industry through protective tariffs and a dollar based on gold triumphed. The voting patterns established then displaced the near-deadlock the major parties had seen since the Civil War; the Republican dominance begun then would continue until 1932, another realigning election with the ascent of Franklin Roosevelt.[123] Phillips argued that, with the possible exception of Iowa Senator Allison, McKinley was the only Republican who could have defeated Bryan—he theorized that eastern candidates such as Morton or Reed would have done badly against the Illinois-born Bryan in the crucial Midwest.[124] According to the biographer, though Bryan was popular among rural voters, "McKinley appealed to a very different industrialized, urbanized America."[125]

Presidency 1897–1901

Inauguration and appointments

William McKinley was sworn in as president on March 4, 1897, as his wife and mother looked on. The new President gave a lengthy inaugural address; he urged tariff reform, and stated that the currency issue would have to await tariff legislation. He warned against foreign interventions, "We want no wars of conquest. We must avoid the temptation of territorial aggression."[126]

McKinley's most controversial Cabinet appointment was that of Senator Sherman as Secretary of State. The controversy arose as one consideration in Sherman's appointment was to provide a Senate place for Hanna (who had turned down a Cabinet position as Postmaster General). As Sherman had served as Secretary of the Treasury under Hayes, only the State position, the leading Cabinet post, was likely to entice him from the Senate. Gould noted that Sherman, who turned 73 in 1896, remained very popular among Republicans, and could not be disregarded as McKinley formed a Cabinet. In addition to the controversy about whether Hanna would replace him, Sherman's mental faculties were decaying even in 1896. This was widely reported, but not believed by McKinley.[127] Nevertheless, McKinley sent his cousin, William McKinley Osborne, to have dinner with Sherman; he reported back that the senator seemed as lucid as ever.[128] McKinley wrote once the appointment was announced, "the stories regarding Senator Sherman's 'mental decay' are without foundation ... When I saw him last I was convinced both of his perfect health, physically and mentally, and that the prospects of life were remarkably good."[128] Sherman was not, however, McKinley's first choice for the position; he initially offered it to Senator Allison.[127]

A factor in Sherman's determination to take the State post if offered was the difficulty he faced if he sought re-election by the Ohio Legislature in 1898; he was likely to be targeted by both the Democrats and Foraker's faction. When McKinley offered Sherman the position in early January 1897, he immediately accepted and McKinley's messenger reported the senator's obvious delight to the President-elect.[127] After some difficulties, Ohio Governor Bushnell appointed Hanna to the Senate.[129] Once in Cabinet office, Sherman's mental incapacity became increasingly apparent, and he was often bypassed by his first assistant, McKinley's Canton crony, Judge Day, and by the somewhat-deaf second secretary, Alvey A. Adee, prior to Sherman's departure from office on the eve of war in 1898. Day, an Ohio lawyer unfamiliar with diplomacy, was often reticent in meetings. One diplomat characterized the arrangement, "the head of the department knew nothing, the first assistant said nothing, and the second assistant heard nothing".[128]

Newspapers speculated that McKinley might appoint a Gold Democrat as Secretary of the Treasury. Some Gold Democrats had supported McKinley while others had nominated a rival ticket to Bryan's, thus splitting the vote and benefiting the Republicans. Charles Dawes, who had been Hanna's lieutenant in Chicago during the campaign, was considered for the post but by some accounts Dawes felt he was too young. Dawes eventually became Comptroller of the Currency; he recorded in his published diary that he had strongly urged McKinley to appoint the successful candidate for the Treasury post, Lyman J. Gage, president of the First National Bank of Chicago.[130] The Navy Department was offered to former Massachusetts Congressman John Davis Long, an old friend from the House, on January 30, 1897.[131] Although McKinley was initially inclined to allow Long to choose his own assistant, there was considerable pressure on the President-elect to appoint Theodore Roosevelt, head of the New York City Police Commission and a former state assemblyman. McKinley was reluctant, stating to one Roosevelt booster, "I want peace and I am told that your friend Theodore is always getting into rows with everybody." Nevertheless, he made the appointment.[132]

The Republican party in Iowa was divided over many matters, but not over former congressman James Wilson; Allison urged his appointment as Secretary of Agriculture. McKinley agreed, and Wilson would remain in that office until the departure of the Taft administration in 1913. The position of Postmaster General was not quickly filled after being declined by Hanna. Once it became clear that Hanna's quest to be appointed to the Senate would be successful, it was offered to James A. Gary of Maryland. Although McKinley had won nowhere in the South, he had taken Gary's border state, and the appointment allowed some sort of representation for the South in the Cabinet.[131] New York State was represented through Cornelius N. Bliss, who had been offered a Cabinet position, possibly the Navy Department, in early January, but had initially declined it. Bliss became Secretary of the Interior. The West was represented through Joseph McKenna of California, with whom McKinley had served in the House. The President-elect intended to offer him the Interior portfolio which eventually went to Bliss and this was reported in the press; when McKenna met with McKinley, the Californian pre-emptively declined the position on the ground that the Interior Secretary supervised Native American education, and Protestants might find McKenna objectionable in that capacity as a Catholic. Without batting an eye, McKinley denied he had intended to make McKenna Interior Secretary, but offered him the position of Attorney General, which he accepted.[133]

In addition to Sherman, McKinley made one other Cabinet appointment which proved ill-advised,[134] that of Secretary of War, which fell to former General and Michigan Governor Russell A. Alger. Competent enough in peacetime, Alger proved to be not up to the position once the conflict against Spain began. With the War Department plagued by scandal, Alger resigned at McKinley's request in mid-1899.[135] Vice President Hobart, as was customary at the time, was not invited to Cabinet meetings. However, he proved a valuable adviser both for McKinley and for his Cabinet members. The wealthy Vice President leased a residence close to the White House; the two families visited each other without formality, and the Vice President's wife, Jennie Tuttle Hobart, sometimes substituted as Executive Mansion hostess when Ida McKinley was not well. A sign of Hobart's influence was that when McKenna was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1898, the Vice President's close ally, New Jersey Governor John Griggs, was appointed Attorney General in his place.[136] George B. Cortelyou served as McKinley's secretary. Cortelyou, who served in three Cabinet positions under Theodore Roosevelt, became a combination press secretary and chief of staff to McKinley.[137]

War with Spain

For decades, rebels in Cuba had waged an intermittent campaign for freedom from Spanish colonial rule. By 1895, the conflict had expanded to an war for Cuban independence.[138] As war engulfed the island, Spanish reprisals against the rebels grew ever harsher. These included the removal of Cubans to reconcentration camps near Spanish military bases, a strategy designed to make it hard for the rebels to receive support in the countryside.[139] American opinion favored the rebels, and McKinley shared in their outrage against Spanish policies.[140] As many of his countrymen called for war to liberate Cuba, McKinley favored a peaceful approach, hoping that through negotiation Spain might be convinced to grant Cuba independence, or at least to allow the Cubans some measure of autonomy.[141] The United States and Spain began negotiations on the subject in 1897, but it became clear that Spain would never concede Cuban independence, while the rebels (and their American supporters) would never settle for anything less.[142] In January 1898, Spain promised some concessions to the rebels, but when American consul Fitzhugh Lee reported riots in Havana, McKinley agreed to send the battleship USS Maine there to protect American lives and property.[143] On February 15, the Maine exploded and sunk with 266 men killed.[144] Public opinion and the newspapers demanded war, but McKinley insisted that a court of inquiry first determine if the explosion was accidental.[145] Negotiations with Spain continued as the court considered the evidence, but on March 20 the court ruled that the Maine was blown up by an underwater mine.[146][note 3] As pressure for war mounted in Congress, McKinley continued to negotiate for Cuban independence.[149] Spain refused to consent to a ceasefire with the rebels, and on April 11, McKinley asked Congress for a declaration of war.[150] The legislature complied quickly and passed the declaration on April 20, with the addition of the Teller Amendment, which disavowed any intention of annexing Cuba.[151]

The expansion of the telegraph and the development of the telephone gave McKinley a greater control over the day-to-day management of the war than previous presidents had enjoyed, and he used the new technologies to direct the army's and navy's movements as far as he was able.[152] McKinley found Alger inadequate as Secretary of War, and did not get along with the Army's commanding general, Nelson A. Miles.[153] Bypassing them, he looked for strategic advice first from Miles's predecessor, General John Schofield, and later from Adjutant General Henry Clarke Corbin.[153] The outbreak of war also led to modernization of McKinley's cabinet, as the President accepted Sherman's resignation as Secretary of State; Day agreed to serve as Secretary until the war's end.[154]

Within a fortnight, the navy had its first victory when the Asiatic Squadron, led by Commodore George Dewey engaged the Spanish navy at the Battle of Manila Bay in the Philippines, destroying the enemy force without the loss of a single American vessel.[155] Dewey's overwhelming victory expanded the scope of the war from one centered in the Caribbean to one that would determine the fate of all of Spain's Pacific colonies.[156] The next month, McKinley increased the number of troops to be sent to the Philippines and granted the force's commander, Major General Wesley Merritt, the power to set up legal systems and raise taxes—necessities for a long occupation.[157] By the time the troops arrived in the Philippines at the end of June 1898, McKinley had decided that Spain would by required to surrender the archipelago to the United States.[158]

Meanwhile, in the Caribbean theater, a large force of regulars and volunteers gathered near Tampa, Florida, for an invasion of Cuba.[159] The army faced difficulties in supplying the rapidly expanding force even before they departed for Cuba, but Alger and Corbin began to resolve the problems by June.[160] After several conferences and several logistical delays, the army, led by Major General William Rufus Shafter, sailed from Florida on June 20, landing near Santiago de Cuba two days later.[161] Following a skirmish at Las Guasimas on June 24, Shafter's army engaged the Spanish forces on July 2 in the Battle of San Juan Hill.[162] In an intense day-long battle, the American force was victorious, although both sides suffered heavy causalities.[163] The next day, the Spanish Caribbean squadron, which had been sheltering in Santiago's harbor, broke for the open sea but was intercepted and destroyed by Rear Admiral William T. Sampson's North Atlantic Squadron in the largest naval battle of the war.[164] Shafter laid siege to the city of Santiago, which surrendered on July 17, leaving the eastern half of the island open to American forces.[165] McKinley and Miles then ordered an invasion of Puerto Rico, which subdued the island by mid-July.[165] The distance from Spain and the destruction of the Spanish navy made resupply impossible, and the Spanish government began to look for a way to end the war.[166]

Peace and territorial gain

On July 22, the Spanish authorized Jules Cambon, the French Ambassador to the United States, to represent Spain in negotiating peace.[166] The Spanish initially wished to restrict the discussion to Cuba, but were quickly forced to recognize that their other possessions were to be claimed as spoils of war.[166] McKinley's cabinet agreed with him that Spain must leave Cuba and Puerto Rico, but they disagreed on the Philippines, with some members favoring annexation and some wishing only to retain a naval base in the area.[167] Although public sentiment seemed to favor annexation of the Philippines, several prominent political leaders, including Bryan, ex-President Cleveland, and the newly formed American Anti-Imperialist League made their opposition known.[168] McKinley proposed to open negotiations with Spain on the basis of Cuban liberation and Puerto Rican annexation, with the final status of the Philippines to be subject to further discussion.[169] He stood firmly in that demand even as the military situation on Cuba began to deteriorate when the American army was struck with yellow fever.[169] Spain ultimately agreed to a ceasefire on those terms on August 12, and treaty negotiations began in Paris in September 1898.[170] The talks continued until December 18, when the Treaty of Paris was signed.[171] The United States acquired Puerto Rico and the Philippines as well as the island of Guam, and Spain relinquished its claims to Cuba; in exchange, the United States agreed to pay Spain $20 million.[171][note 4] McKinley had difficulty convincing the Senate to approve the treaty by the requisite two-thirds vote, but his lobbying was ultimately successful as the Senate voted in favor on February 6, 1899, 57 to 27.[173]

At the same time, McKinley was also pursuing the annexation of the Republic of Hawaii. The pro-American government of Hawaii had sought annexation since its leaders came to power after the demise of the royal government there in 1893.[174] Although McKinley's predecessor, Cleveland, rejected their overtures, many Americans favored annexation, and the cause gained momentum as the United States embroiled in war with Spain.[175] McKinley came to office as a supporter of annexation, and lobbied Congress to adopt his opinion, believing that to do nothing would invite royalist counter-revolution or Japanese conquest.[175] Foreseeing difficulty in getting two-thirds of the Senate to approve a treaty of annexation, McKinley instead supported the effort of Democratic Representative Francis G. Newlands of Nevada to accomplish the result by joint resolution of both houses of Congress.[176] The resulting Newlands Resolution passed both houses by wide margins, and McKinley signed it into law on July 8, 1898.[176] Wake Island, an uninhabited atoll between Hawaii and Guam, was occupied four days later.[177]

Expanding influence overseas

In acquiring of Pacific possessions for the United States, McKinley expanded the nation's ability to compete for trade in China.[178] Even before peace negotiations began with Spain, McKinley asked Congress to set up a commission to examine trade opportunities in the region and espoused an "Open Door Policy", in which all nations would freely trade with China and none would seek to violate that nation's territorial integrity.[179] When John Hay replaced Day as Secretary of State at the end of the war, he circulated notes to that effect to the European powers.[180] Great Britain favored the idea, but Russia opposed it; France, Germany, Italy and Japan agreed in principle, but only if all the other nations signed on.[180]

Trade with China became imperiled shortly thereafter as the Boxer Rebellion menaced foreigners and their property in China.[181] Americans and other westerners in Peking were besieged and, in cooperation with other western powers, McKinley ordered 5000 troops to the city in June 1900 in the China Relief Expedition.[182] The westerners were liberated the next month, but several Congressional Democrats objected to McKinley dispatching troops without consulting the legislature.[181] McKinley's actions set a precedent that led to most of his successors exerting similar independent control over the military.[182] After the rebellion ended, the United States reaffirmed its commitment to the Open Door policy, which became the basis of American policy toward China.[183]

Closer to home, McKinley and Hay engaged in negotiations with Britain over the possible construction of a canal across Central America. The Clayton–Bulwer Treaty, which the two nations signed in 1850, prohibited either from establishing exclusive control over a canal there. The war had exposed the difficulty of maintaining a two-ocean navy without a connection closer than Cape Horn.[184] Now, with American business and military interests even more involved in Asia, a canal seemed more essential than ever, and McKinley pressed for a renegotiation of the treaty.[184] Hay and the British ambassador, Julian Pauncefote, agreed that the United States could control a future canal, provided that it was open to all shipping and not fortified.[185] McKinley was satisfied with the terms, but the Senate rejected them, demanding that the United States be allowed to fortify the canal.[185] Hay was embarrassed by the rebuff and offered his resignation, but McKinley refused it and ordered him to continue negotiations to achieve the Senate's demands.[185] He was successful, and a new treaty was drafted and approved, but not before McKinley's assassination in 1901.[185]

Domestic policies

McKinley, then aged 54, became the nation's chief executive at a salary of $50,000. The family became regular attendees at the Metropolitan Methodist Church and Mrs. McKinley appeared quite ready and able, with some assistance, to assume her duties as the White House hostess.[186] His inauguration marked the beginning of the greatest consolidation in American business that had ever been seen.[187] The administration did not aggressively enforce the Sherman Antitrust Act, as Theodore Roosevelt later would, and therefore business trusts were allowed to expand.

McKinley's claim as the "advance agent of prosperity" was confirmed when 1897 brought a revival of business, agriculture, and general prosperity, ending the Panic of 1893 which dated back to the Civil War and was marked by persistent underconsumption.[188] The end of the deflationary period resulted largely from a gradual adoption of gold, culminating in passage of the Gold Standard Act of 1900, which set the value of the dollar and alleviated monetary concerns that had plagued the United States since the 1870s.[189] This wave of prosperity, bolstered by US victory in the Spanish-American War, continued into the 20th century until the Panic of 1907, and ensured McKinley's reelection in 1900.

In civil service administration, McKinley reformed the system to make it more flexible in critical areas. The Republican platform, adopted after President Cleveland's extension of the merit system, emphatically endorsed this, as did McKinley himself. Against extreme pressure, particularly in the Department of War, the President resisted until May 29, 1899. His order of that date withdrew from the classified service 4,000 or more positions, removed 3,500 from the class theretofore filled through competitive examination or an orderly practice of promotion, and placed 6,416 more under a system drafted by the Secretary of War. The order declared as permanent a large number of temporary appointments made without examination, including thousands who had served during the Spanish War. In the way of patronage, McKinley adeptly employed appointments to cultivate the favor of members of the Senate, but also made appointments which flowed to his singular benefit. While many suspected otherwise, newly appointed Senator Mark Hanna was not allowed to assume an insider's role in McKinley's appointments.[190]

Tariffs and bimetallism

Two of the great issues of the day, tariff reform and free silver, became intertwined in 1897.[191] Nelson Dingley, Jr., a Maine Republican who had succeeded McKinley as chairman of the Ways and Means committee, introduced a new tariff bill (later called the Dingley Act) to revise the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act of 1894.[191] McKinley supported the bill, which increased tariffs on wool, sugar, and luxury goods, but the proposed new rates alarmed the French, who exported many luxury items to the United States.[191] The Dingley Act passed the House easily, but was delayed in the Senate as they assessed the French objections.[192] French representatives offered to cooperate with the United States in developing an international agreement on bimetallism if the new tariff rates were reduced; this pleased silverite Republicans in the Senate, whose votes were necessary for passage.[193] The Senate amended the bill to allow limited reciprocity (giving France some possibility of relief), but did not reduce the rates on luxury goods.[194] McKinley signed the bill into law and agreed to begin negotiations on an international bimetallism standard.[195]

American negotiators soon concluded a reciprocity treaty with France, and the two nations approached the United Kingdom to gauge British enthusiasm for bimetallism.[195] The British government of the Marquess of Salisbury showed some interest in the idea and told the American envoy, Edward O. Wolcott, that they would be amenable to reopening the mints in India to silver coinage if the colonial government there agreed.[196] News of a possible departure from the gold standard stirred up immediate opposition from its partisans, and misgivings by the Indian colonial government led Britain to reject the proposal.[196] With the international effort a failure, McKinley turned away from silver coinage and embraced the gold standard.[197] Even without the agreement, agitation for free silver eased as prosperity began to return to the United States and gold from recent strikes in the Yukon and Australia increased the monetary supply even without silver coinage.[198] In the absence of international agreement, McKinley favored legislation to formally affirm the gold standard, but was initially deterred by the silver strength in the Senate.[199] By 1900, with another campaign ahead and good economic times, McKinley urged Congress to pass such a law, and was able to sign the Gold Standard Act on March 14, 1900, using a gold pen to do so.[200]

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court

McKinley appointed the following Justice to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Joseph McKenna – 1898

Other judges

Along with his Supreme Court appointment, McKinley appointed six judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 28 judges to the United States district courts.

Civil rights

In the wake of McKinley's election in 1896, blacks were hopeful of progress towards equality. McKinley had spoken out against lynching while governor, and most blacks who could vote supported him in 1896. McKinley's priority, however, was in ending sectionalism, and blacks were disappointed by his policies and appointments. Although McKinley made some appointments of blacks to low-level government posts, and received some praise for that, the appointments were less than blacks had received under previous Republican administrations. Former Mississippi Senator Blanche K. Bruce received the post of register at the Treasury Department; this post was traditionally given to a black under Republican administrations. McKinley appointmented several black postmasters, however when whites protested the appointment of Justin W. Lyons as postmaster of Augusta, Georgia, McKinley asked Lyons to withdraw; he was given the post of Treasury register after Bruce's death in 1898.[201] The President did appoint George B. Jackson, a former slave, to the post of customs collector in Presidio, Texas.[202] However, northern blacks felt their contributions to McKinley's victory were overlooked; few were appointed to office.[201]

The administration's response to violence against blacks was minimal; according to historian Lewis L. Gould in his study of the McKinley administration, "from expectant hope when McKinley took office, Negro leaders moved to deep disillusionment as the president failed them."[201] When black postmasters at Hogansville, Georgia in 1897 and at Lake City, South Carolina the following year were assaulted, McKinley issued no statement of condemnation. Although black leaders criticized McKinley for inaction, supporters responded there was little the president could do to intervene. Critics replied that he could at least publicly condemn such events, as Harrison had done.[203]

According to historian Clarance A. Bacote, "Before the Spanish-American War, the Negroes, in spite of some mistakes, regarded McKinley as the best friend they ever had."[204] Blacks saw the onset of war in 1898 as an opportunity to display their patriotism; and black soldiers fought bravely at the Battles of El Caney and San Juan Hill. However, many black militia units were not permitted to join the fighting, and black volunteers were turned back. Blacks in the peacetime Army had formed elite units; nevertheless they were harassed by whites as they traveled from the West to Tampa for embarkation to the war. However, under pressure from black leaders, McKinley required the War Department to commission black officers above the rank of lieutenant. The heroism of the black troops who got to fight did not still racial tensions in the South, as the second half of 1898 saw several outbreaks of racial violence; 11 blacks were killed in riots in Wilmington, North Carolina.[205] McKinley toured the South in late 1898, hoping for sectional reconciliation in the wake of the war. In addition to visiting Tuskegee Institute and black educator Booker T. Washington, he addressed the Georgia legislature, wearing a badge of gray, and visited Confederate memorials. In his tour of the South, McKinley did not address the racial tensions or violence in his speeches. Although the President received a rapturous reception from Southern whites, many blacks, who were excluded from official welcoming committees, felt alienated by the President's words and actions.[205][206]

In December 1899, Wisconsin Republican National Committeeman Henry C. Payne proposed a change in allocation of convention delegates among the states. Each state was allocated delegates based on its population; thus the South, where the Republicans rarely won electoral votes, had considerable weight at the convention. Many of the delegates from the South were black, and McKinley, who initially favored the proposal, persuaded Payne to withdraw the proposal; McKinley feared the effect on the Republican vote among blacks.[207] According to Gould, given the political climate in the South, with white legislatures passing Jim Crow laws such as that upheld in Plessy v. Ferguson, there was little McKinley could have done to improve race relations, and he did better than later presidents Theodore Roosevelt, who doubted black equality, and Woodrow Wilson, who supported segregation; later biographer Phillips agreed. However, Gould concluded, "McKinley lacked the vision to transcend the biases of his day and to point toward a better future for all Americans".[208]

Election of 1900 and second term

The President was nominated by his party with Theodore Roosevelt as his running mate. He was publicly silent on the V.P. choice, but privately preferred Sen. William B. Allison, the "father of the Senate" as the V.P. nominee, who declined the offer; McKinley thought Roosevelt should head the War Department.[209] He was re-elected in 1900, this time with economic prosperity in hand and an ebullient national mood after the successful war. Foreign policy was the paramount issue, with the Democrats denouncing the colonialism of the Republicans and insisting the Constitution should follow the flag to annexed territories.[210] William Jennings Bryan, again the Democratic candidate, also reprised the silver issue. McKinley easily won re-election, giving Republicans the largest electoral margin since 1872.[211][212]

All of McKinley's cabinet at the time of the election continued in service with the exception of the Attorney General.[213] In early 1901 the President pressed for settlement of the constitutional and governmental questions in Cuba so that the focus could be turned to the Philippines. He also led negotiations with Congress on the Spooner bill authorizing establishment of a civil government in the Philippines.[214] Taft was made provisional governor there to demonstrate the nation's resolve to emphasize civil versus military solutions.[215]

The President and Mrs. McKinley took a trip west to California in May 1901. She became quite ill on the trip, and McKinley spent most of his time with his wife, but he was able to deliver a speech in San Jose, California on May 13 and to attend his parade in San Francisco on May 14. The president went to Oakland without his wife, to speak on May 17. The President visited the Union Iron Works of San Francisco to observe the launching of the battleship, USS Ohio (BB-12). Mrs. William McKinley attended the ceremony, but the First Lady became critically (though temporarily) ill in San Francisco and a planned tour of the Northwest was cancelled.[216]

Assassination

Ida McKinley's illness in California caused her husband to limit his public events and cancel a series of speeches he had planned to give urging trade reciprocity. He also postponed his visit to the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, originally scheduled for the train tour, until September, planning a month in Washington and two in Canton before going to Buffalo. He spent part of his time in Canton preparing a major speech for the fairgrounds visit. With rumors afloat that he might run for a third term, McKinley made it clear he would uphold the two-term custom for American presidents.[217] While in Canton, McKinley became the first US president to ride in an automobile, driven in the car of his friend Zebulon Davis, a car manufacturer.[218]

Although McKinley enjoyed meeting the public, Cortelyou was concerned with his security, and twice tried to remove a public reception from the President's rescheduled visit to the Exposition. McKinley refused, and Cortelyou arranged for additional security for the trip.[219] On September 5, the President delivered his address at the fairgrounds, before a crowd of some 100,000 people. In his final speech, McKinley urged reciprocity treaties with other nations to assure American manufacturers foreign markets. He intended the speech as a keynote to his plans for a second term, and concluded it with a tribute to Blaine, who had been a strong supporter of protection.[220][221]

One man in the crowd, anarchist Leon Czolgosz, was not there to hear McKinley, but to kill him. He had managed to get close to the presidential podium, but did not fire, uncertain of hitting his target. Even at the end of McKinley's speech, Czolgosz considered shooting him, but before he could decide, the President left the podium, surrounded by security, for a tour of the fair.[220] Czolgosz, since hearing a speech by fellow anarchist Emma Goldman in Chicago, had decided to do something heroic (in his own mind) for the cause. He had initially decided to get near McKinley, on September 4, he decided to assassinate him.[222] After the failed attempt on the 5th, Czolgosz got near McKinley as the President went from the Milburn House, a private residence where he was staying while in Buffalo, to the railroad station for a trip to Niagara Falls, but not close enough to risk an attempt. Czolgosz lined up at the Temple of Music on the Exposition grounds, where the President was to meet the public after his return from the falls. The anarchist concealed his gun in a hankerchief, and when he reached the head of the line, shot McKinley twice in the abdomen.[223]