Somali people: Difference between revisions

m Date maintenance tags and general fixes: build 443: |

fmtting, refs, c/e |

||

| Line 102: | Line 102: | ||

<blockquote>"The data suggest that the male Somali population is a branch of the East African population − closely related to the [[Oromo people|Oromos]] in Ethiopia and North Kenya − with predominant [[Haplogroup E1b1b (Y-DNA)|E3b1]] cluster lineages that were introduced into the Somali population 4000−5000 years ago, and that the Somali male population has approximately 15% [[Y chromosome]]s from [[Eurasia]] and approximately 5% from [[sub-Saharan Africa]]."<ref name=Sanchez2005>Sanchez et al., [http://www.nature.com/ejhg/journal/v13/n7/full/5201390a.html High frequencies of Y chromosome lineages characterized by E3b1, DYS19-11, DYS392-12 in Somali males], Eu J of Hum Genet (2005) 13, 856–866</ref></blockquote> |

<blockquote>"The data suggest that the male Somali population is a branch of the East African population − closely related to the [[Oromo people|Oromos]] in Ethiopia and North Kenya − with predominant [[Haplogroup E1b1b (Y-DNA)|E3b1]] cluster lineages that were introduced into the Somali population 4000−5000 years ago, and that the Somali male population has approximately 15% [[Y chromosome]]s from [[Eurasia]] and approximately 5% from [[sub-Saharan Africa]]."<ref name=Sanchez2005>Sanchez et al., [http://www.nature.com/ejhg/journal/v13/n7/full/5201390a.html High frequencies of Y chromosome lineages characterized by E3b1, DYS19-11, DYS392-12 in Somali males], Eu J of Hum Genet (2005) 13, 856–866</ref></blockquote> |

||

Besides comprising the majority of the Y DNA in Somalis, the [[Haplogroup E1b1b (Y-DNA)|E1b1b]] (formerly E3b) genetic [[haplogroup]] also makes up the bulk of the paternal DNA of Ethiopians, Eritreans, [[Berber people|Berber]]s, North African [[Arab]]s, as well as many [[Mediterranean Sea|Mediterranean]] and [[Balkans|Balkan]] Europeans.<ref>Cruciani et al., "[http://www.ajhg.org/AJHG/fulltext/S0002-9297(07)64365-1?large_figure=true Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa"], Am J Hum Genet. 2004 May; 74(5): 1014–1022</ref> The M78 subclade of E1b1b is found in about 77% of Somali males, which may represent the traces of an ancient migration into the Horn of Africa from the upper [[Egypt]] area.<ref name=Sanchez2005/> After haplogroup E1b1b, the second most frequently occurring [[Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup|Y DNA haplogroup]] among Somalis is the Eurasian [[haplogroup T (Y-DNA)|haplogroup T]] (M70),<ref>Underhill et al., "The Levant versus the Horn of Africa: Evidence for Bidirectional Corridors of Human Migrations," ''American Journal of Human Genetics'' 74:532-544, 2004</ref> which is found in slightly more than 10% of Somali males. Haplogroup T, like haplogroup E1b1b, is also typically found among populations of [[ |

Besides comprising the majority of the Y DNA in Somalis, the [[Haplogroup E1b1b (Y-DNA)|E1b1b]] (formerly E3b) genetic [[haplogroup]] also makes up the bulk of the paternal DNA of Ethiopians, Eritreans, [[Berber people|Berber]]s, North African [[Arab]]s, as well as many [[Mediterranean Sea|Mediterranean]] and [[Balkans|Balkan]] Europeans.<ref>Cruciani et al., "[http://www.ajhg.org/AJHG/fulltext/S0002-9297(07)64365-1?large_figure=true Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa"], Am J Hum Genet. 2004 May; 74(5): 1014–1022</ref> The M78 subclade of E1b1b is found in about 77% of Somali males, which may represent the traces of an ancient migration into the Horn of Africa from the upper [[Egypt]] area.<ref name=Sanchez2005/> After haplogroup E1b1b, the second most frequently occurring [[Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup|Y DNA haplogroup]] among Somalis is the Eurasian [[haplogroup T (Y-DNA)|haplogroup T]] (M70),<ref>Underhill et al., "The Levant versus the Horn of Africa: Evidence for Bidirectional Corridors of Human Migrations," ''American Journal of Human Genetics'' 74:532-544, 2004</ref> which is found in slightly more than 10% of Somali males. Haplogroup T, like haplogroup E1b1b, is also typically found among populations of [[Northeast Africa]], [[North Africa]], the [[Near East]] and the Mediterranean.<ref name="Apghmoacds">{{cite journal |last1=Cabrera |first1=Vicente M. |last2=Abu-Amero |first2=Khaled K. |year=2009 |title=The Arabian peninsula: Gate for Human Migrations Out of Africa or Cul-de-Sac? A Mitochondrial DNA Phylogeographic Perspective |journal=Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology Series |volume=Part 2 |pages=79-87 |doi=10.1007/978-90-481-2719-1_6}}</ref><ref name="Mdhtb">{{cite journal |last1=Fadhlaoui-Zid |first1=K. |last2=Plaza |first2=S. |year=2009 |title=Mitochondrial DNA Heterogeneity in Tunisian Berbers |journal=Annals of Human Genetics |year=2004 |volume=68 |issue=3 |pages=222-233 |doi=10.1007/978-90-481-2719-1_6}}</ref> |

||

===mtDNA=== |

===mtDNA=== |

||

According to |

According to an [[mtDNA]] study by Holden (2005), a large proportion of the maternal ancestry of Somalis consists of the [[Haplogroup M (mtDNA)|M1 haplogroup]],<ref name="A.D.">A.D. Holden (2005), [http://konig.la.utk.edu/AJPA_Suppl_40_web.htm MtDNA variation in North, East, and Central African populations gives clues to a possible back-migration from the Middle East], Program of the Seventy-Fourth Annual Meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists (2005)</ref> which is common among [[People of Ethiopia|Ethiopians]] and [[North Africa]]ns, particularly [[Egyptians]] and [[Algeria]]ns.<ref name="Mdsdspe">{{cite journal |last1=Malyarchuk |first1=Boris A. |last2=Gilles |first2=A |last3=Bouzaid |first3=E |year=2008 |title=Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Diversity in a Sedentary Population from Egypt |journal=Annals of Human Genetics |volume=68 |pages=23 |doi=10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00057.x}}</ref><ref name="Rpamds">{{cite journal |last1=Malyarchuk |first1=Boris A. |last2=Derenko |first2=Miroslava |year=2008 |title=Reconstructing the phylogeny of African mitochondrial DNA lineages in Slavs |journal=European Journal of Human Genetics |volume=16 |pages=1091–1096 |doi=10.1038/ejhg.2008.70}}</ref> M1 is believed to have originated in [[Asia]],<ref name="Gonzalez">Gonzalez et al., [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1945034 Mitochondrial lineage M1 traces an early human backflow to Africa], BMC Genomics 2007, 8:223 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-8-223</ref> where its parent M clade represents the majority of mtDNA lineages<ref>Ghezzi et al. (2005), [http://www.nature.com/ejhg/journal/v13/n6/full/5201425a.html Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup K is associated with a lower risk of Parkinson's disease in Italians], European Journal of Human Genetics (2005) 13, 748–752.</ref> (particularly in [[India]]).<ref name="Rajkumar et al.">Revathi Rajkumar et al., [http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/5/26 Phylogeny and antiquity of M macrohaplogroup inferred from complete mt DNA sequence of Indian specific lineages], BMC Evolutionary Biology 2005, 5:26 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-26</ref> This haplogroup is also thought to possibly correlate with the [[Afro-Asiatic languages|Afro-Asiatic]] language family:<ref name="A.D."/> |

||

<blockquote>"We analysed mtDNA variation in ~250 persons from Libya, Somalia, and Congo/Zambia, as representatives of the three regions of interest. Our initial results indicate a sharp cline in M1 frequencies that generally does not extend into sub-Saharan Africa. While our North and especially East African samples contained frequencies of M1 over 20%, our sub-Saharan samples consisted almost entirely of the L1 or L2 haplogroups only. In addition, there existed a significant amount of homogeneity within the M1 haplogroup. This sharp cline indicates a history of little admixture between these regions. This could imply a more recent ancestry for M1 in Africa, as older lineages are more diverse and widespread by nature, and may be an indication of a back-migration into Africa from the Middle East."<ref name="A.D." |

<blockquote>"We analysed mtDNA variation in ~250 persons from Libya, Somalia, and Congo/Zambia, as representatives of the three regions of interest. Our initial results indicate a sharp cline in M1 frequencies that generally does not extend into sub-Saharan Africa. While our North and especially East African samples contained frequencies of M1 over 20%, our sub-Saharan samples consisted almost entirely of the L1 or L2 haplogroups only. In addition, there existed a significant amount of homogeneity within the M1 haplogroup. This sharp cline indicates a history of little admixture between these regions. This could imply a more recent ancestry for M1 in Africa, as older lineages are more diverse and widespread by nature, and may be an indication of a back-migration into Africa from the Middle East."<ref name="A.D."/></blockquote> |

||

[[File:Somali nomad girls.jpg|right|thumb|300px|Somali girls in traditional [[nomad]]ic attire.]] |

[[File:Somali nomad girls.jpg|right|thumb|300px|Somali girls in traditional [[nomad]]ic attire.]] |

||

Another mtDNA study indicates that: |

Another mtDNA study indicates that: |

||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

<blockquote>"Somali, as a representative East African population, seem to have experienced a detectable amount of Caucasoid maternal influence... the proportion ''m'' of Caucasoid lineages in the Somali is ''m'' = 0.46 [46%]... Our results agree with the hypothesis of a maternal influence of Caucasoid lineages in East Africa, although its contribution seems to be higher than previously reported in mtDNA studies."<ref>Comas et al. from (1999), [http://www.nature.com/ejhg/journal/v7/n4/pdf/5200326a.pdf Analysis of mtDNA HVRII in several human populations using an immobilised SSO probe hybridisation assay], Eur J Hum Genet. 1999 May-Jun;7(4):459-68.</ref></blockquote> |

<blockquote>"Somali, as a representative East African population, seem to have experienced a detectable amount of Caucasoid maternal influence... the proportion ''m'' of Caucasoid lineages in the Somali is ''m'' = 0.46 [46%]... Our results agree with the hypothesis of a maternal influence of Caucasoid lineages in East Africa, although its contribution seems to be higher than previously reported in mtDNA studies."<ref>Comas et al. from (1999), [http://www.nature.com/ejhg/journal/v7/n4/pdf/5200326a.pdf Analysis of mtDNA HVRII in several human populations using an immobilised SSO probe hybridisation assay], Eur J Hum Genet. 1999 May-Jun;7(4):459-68.</ref></blockquote> |

||

Overall, the genetic studies conclude that Somalis and their fellow Ethiopian and Eritrean [[Horn of Africa|Northeast African]] populations represent a unique and distinct biological group on the continent:<ref>Risch et al. (1999), [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=139378 Categorization of humans in biomedical research: genes, race and disease], Genome Biol. 2002; 3(7): comment2007.1–comment2007.12.</ref> |

Overall, the genetic studies conclude that Somalis and their fellow Ethiopian and Eritrean [[Horn of Africa|Northeast African]] populations represent a unique and distinct biological group on the continent:<ref>Risch et al. (1999), [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=139378 Categorization of humans in biomedical research: genes, race and disease], Genome Biol. 2002; 3(7): comment2007.1–comment2007.12.</ref><ref name="Tishkoff">Tishkoff et al. (2000). "Short Tandem-Repeat Polymorphism/Alu Haplotype Variation at the PLAT Locus: Implications for Modern Human Origins". Am J Hum Genet; 67:901-925</ref> |

||

<blockquote>"The most distinct separation is between African and non-African populations. The northeastern-African -- that is, the Ethiopian and Somali -- populations are located centrally between sub-Saharan African and non-African populations... The fact that the Ethiopians and Somalis have a subset of the sub-Saharan African haplotype diversity -- and that the non-African populations have a subset of the diversity present in Ethiopians and Somalis -- makes simple-admixture models less likely; rather, these observations support the hypothesis proposed by other nuclear-genetic studies (Tishkoff et al. 1996a, 1998a, 1998b; Kidd et al. 1998) -- that populations in northeastern Africa may have diverged from those in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa early in the history of modern African populations and that a subset of this northeastern-African population migrated out of Africa and populated the rest of the globe. These conclusions are supported by recent mtDNA analysis (Quintana-Murci et al. 1999)."<ref |

<blockquote>"The most distinct separation is between African and non-African populations. The northeastern-African -- that is, the Ethiopian and Somali -- populations are located centrally between sub-Saharan African and non-African populations... The fact that the Ethiopians and Somalis have a subset of the sub-Saharan African haplotype diversity -- and that the non-African populations have a subset of the diversity present in Ethiopians and Somalis -- makes simple-admixture models less likely; rather, these observations support the hypothesis proposed by other nuclear-genetic studies (Tishkoff et al. 1996a, 1998a, 1998b; Kidd et al. 1998) -- that populations in northeastern Africa may have diverged from those in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa early in the history of modern African populations and that a subset of this northeastern-African population migrated out of Africa and populated the rest of the globe. These conclusions are supported by recent mtDNA analysis (Quintana-Murci et al. 1999)."<ref name="Tishkoff"/></blockquote> |

||

==Islam== |

==Islam== |

||

Revision as of 20:29, 16 August 2010

| File:Somaaliyeed.JPG | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Horn of Africa, Middle East | |

| 9.1 million[1] | |

| 4.6 million[2] | |

| 858,000[citation needed] | |

| 780,000[3] | |

| 350,000[citation needed] | |

| 43,515[4] | |

| 37,785[5] | |

| 35,760[6] | |

| 25,000[7] | |

| 20,000[7] | |

| 25,496[8] | |

| 21,597[9] | |

| 19,549[10] | |

| 16,550[11] | |

| 9,810[12] | |

| 6,414[13] | |

| Languages | |

| Somali | |

| Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Afar • Agaw • Amhara • Beja • Jeberti • Oromo • Saho • Tigray • Tigre | |

Somalis ([Soomaaliyeed] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help), Arabic: الصوماليون) are an ethnic group located in the Horn of Africa, also known as the Somali Peninsula. The overwhelming majority of Somalis speak the Somali language, which is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family. Ethnic Somalis number around 15-17 million and are principally concentrated in Somalia (more than 9 million[1]), Ethiopia (4.6 million[2]), Yemen (a little under 1 million), northeastern Kenya (about half a million), Djibouti (350,000), and an unknown but large number live in parts of the Middle East, North America and Europe.

History

| History of Somalia |

|---|

|

|

|

In antiquity, the ancestors of the Somali people were an important link in the Horn of Africa connecting the region's commerce with the rest of the ancient world. Somali sailors and merchants were the main suppliers of frankincense, myrrh and spices, items which were considered valuable luxuries by the Ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians, Mycenaeans and Babylonians.[16][17]

According to most scholars, the ancient Kingdom of Punt and its inhabitants formed part of the ethnogenesis of the Somali people.[18][19][20][21] The ancient Puntites were a nation of people that had close relations with Pharaonic Egypt during the times of Pharaoh Sahure and Queen Hatshepsut. The pyramidal structures, temples and ancient houses of dressed stone littered around Somalia are said to date from this period.[22]

In the classical era, several ancient city-states such as Opone, Mosyllon and Malao that competed with the Sabaeans, Parthians and Axumites for the wealthy Indo-Greco-Roman trade also flourished in Somalia.[23]

The birth of Islam on the opposite side of Somalia's Red Sea coast meant that Somali merchants, sailors and expatriates living in the Arabian Peninsula gradually came under the influence of the new religion through their converted Arab Muslim trading partners. With the migration of fleeing Muslim families from the Islamic world to Somalia in the early centuries of Islam and the peaceful conversion of the Somali population by Somali Muslim scholars in the following centuries, the ancient city-states eventually transformed into Islamic Mogadishu, Berbera, Zeila, Barawa and Merca, which were part of the Berberi civilization. The city of Mogadishu came to be known as the City of Islam,[24] and controlled the East African gold trade for several centuries.[25]

In the Middle Ages, several powerful Somali empires dominated the regional trade including the Ajuuraan State, which excelled in hydraulic engineering and fortress building,[26] the Sultanate of Adal, whose general Ahmed Gurey was the first African commander in history to use cannon warfare on the continent during Adal's conquest of the Ethiopian Empire,[27] and the Gobroon Dynasty, whose military dominance forced governors of the Omani empire north of the city of Lamu to pay tribute to the Somali Sultan Ahmed Yusuf.[28]

In the late 19th century, after the Berlin conference had ended, European empires sailed with their armies to the Horn of Africa. The imperial clouds wavering over Somalia alarmed the Dervish leader Muhammad Abdullah Hassan, who gathered Somali soldiers from across the Horn of Africa and began one of the longest colonial resistance wars ever. The Dervish State successfully repulsed the British empire four times and forced it to retreat to the coastal region.[29] As a result of its successes against the British, the Dervish State received support from the Ottoman and German empires. The Turks also named Hassan Emir of the Somali nation,[30] and the Germans promised to officially recognize any territories the Dervishes were to acquire.[31] After a quarter of a century of holding the British at bay, the Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920, when Britain for the first time in Africa used airplanes to bomb the Dervish capital of Taleex. As a result of this bombardment, former Dervish territories were turned into a protectorate of Britain. Italy similarly faced the same opposition from Somali Sultans and armies and did not acquire full control of parts of modern Somalia until the Fascist era in late 1927. This occupation lasted till 1941 and was replaced by a British military administration. The Union of the two regions in 1960 formed the Somali Democratic Republic that would actively pursue a Greater Somalia policy of uniting all of the Somali inhabited regions of the Horn of Africa.

Pan-Somalism

Somali people in the Horn of Africa are divided among different countries (Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia, and northeastern Kenya) that were artificially and some might say arbitrarily partitioned by the former imperial powers. Pan-Somalism is an ideology that advocates the unification of all ethnic Somalis once part of Somali empires such as the Ajuuraan Empire, the Adal Sultanate, the Gobroon Dynasty and the Dervish State under one flag and one nation. The Siad Barre regime actively promoted Pan-Somalism, which eventually led to the Ogaden War between Somalia on one side, and Ethiopia, Cuba and the Soviet Union on the other.

Notable Pan-Somalists

- Muhammad Abdullah Hassan (April 7, 1856 - December 21, 1920) – Somali nationalist and religious leader that established the Dervish State during the Scramble for Africa.

- Hasna Doreh – Early 20th century Somali female commander of the Dervish State that frequently joined battles against the imperial powers during the Scramble for Africa.

- Hawo Tako (d.1948) – Early 20th century Somali female nationalist whose sacrifice became a symbol for Pan-Somalism.

- Abdullahi Issa (b.1922-1988) – First Prime Minister of Somalia.

- Aden Abdullah Osman Daar (January 7, 1960 - June 10, 1967) – First President of Somalia.

- Abdirashid Ali Shermarke (June 10, 1967 - October 15, 1969) – Second President of Somalia.

- Siad Barre (b. 1919 - January 2, 1995) – Third President of Somalia.

- Daud Abdulle Hirsi (1925–1965) – Prominent Somali General considered the Father of the Somali Military.

- Mahmoud Harbi – active Pan-Somalist that came close to uniting Djibouti with Somalia in the 1970s.

- Salaad Gabeyre Kediye – Major General in the Somali military and a revolutionary.

- Haji Dirie Hirsi (b. 1905 - 1975) – Somali businessman actively supporting Pan-Somalist aspirations in the 1950s.

Genetics

Genetic genealogy, although a new tool that uses the genes of modern populations to trace their ethnic and geographic origins, has also helped pinpoint the possible background of the modern Somalis.

Y DNA

According to one prominent study on Y chromosomes published in the European Journal of Human Genetics, the Somalis are closely related to certain Ethiopian and Eritrean groups:

"The data suggest that the male Somali population is a branch of the East African population − closely related to the Oromos in Ethiopia and North Kenya − with predominant E3b1 cluster lineages that were introduced into the Somali population 4000−5000 years ago, and that the Somali male population has approximately 15% Y chromosomes from Eurasia and approximately 5% from sub-Saharan Africa."[32]

Besides comprising the majority of the Y DNA in Somalis, the E1b1b (formerly E3b) genetic haplogroup also makes up the bulk of the paternal DNA of Ethiopians, Eritreans, Berbers, North African Arabs, as well as many Mediterranean and Balkan Europeans.[33] The M78 subclade of E1b1b is found in about 77% of Somali males, which may represent the traces of an ancient migration into the Horn of Africa from the upper Egypt area.[32] After haplogroup E1b1b, the second most frequently occurring Y DNA haplogroup among Somalis is the Eurasian haplogroup T (M70),[34] which is found in slightly more than 10% of Somali males. Haplogroup T, like haplogroup E1b1b, is also typically found among populations of Northeast Africa, North Africa, the Near East and the Mediterranean.[35][36]

mtDNA

According to an mtDNA study by Holden (2005), a large proportion of the maternal ancestry of Somalis consists of the M1 haplogroup,[37] which is common among Ethiopians and North Africans, particularly Egyptians and Algerians.[38][39] M1 is believed to have originated in Asia,[40] where its parent M clade represents the majority of mtDNA lineages[41] (particularly in India).[42] This haplogroup is also thought to possibly correlate with the Afro-Asiatic language family:[37]

"We analysed mtDNA variation in ~250 persons from Libya, Somalia, and Congo/Zambia, as representatives of the three regions of interest. Our initial results indicate a sharp cline in M1 frequencies that generally does not extend into sub-Saharan Africa. While our North and especially East African samples contained frequencies of M1 over 20%, our sub-Saharan samples consisted almost entirely of the L1 or L2 haplogroups only. In addition, there existed a significant amount of homogeneity within the M1 haplogroup. This sharp cline indicates a history of little admixture between these regions. This could imply a more recent ancestry for M1 in Africa, as older lineages are more diverse and widespread by nature, and may be an indication of a back-migration into Africa from the Middle East."[37]

Another mtDNA study indicates that:

"Somali, as a representative East African population, seem to have experienced a detectable amount of Caucasoid maternal influence... the proportion m of Caucasoid lineages in the Somali is m = 0.46 [46%]... Our results agree with the hypothesis of a maternal influence of Caucasoid lineages in East Africa, although its contribution seems to be higher than previously reported in mtDNA studies."[43]

Overall, the genetic studies conclude that Somalis and their fellow Ethiopian and Eritrean Northeast African populations represent a unique and distinct biological group on the continent:[44][45]

"The most distinct separation is between African and non-African populations. The northeastern-African -- that is, the Ethiopian and Somali -- populations are located centrally between sub-Saharan African and non-African populations... The fact that the Ethiopians and Somalis have a subset of the sub-Saharan African haplotype diversity -- and that the non-African populations have a subset of the diversity present in Ethiopians and Somalis -- makes simple-admixture models less likely; rather, these observations support the hypothesis proposed by other nuclear-genetic studies (Tishkoff et al. 1996a, 1998a, 1998b; Kidd et al. 1998) -- that populations in northeastern Africa may have diverged from those in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa early in the history of modern African populations and that a subset of this northeastern-African population migrated out of Africa and populated the rest of the globe. These conclusions are supported by recent mtDNA analysis (Quintana-Murci et al. 1999)."[45]

Islam

Somalis are entirely Muslims, the majority belonging to the Sunni branch of Islam and the Shafi`i school of Islamic jurisprudence,[46] although a few are also adherents of the Shia Muslim denomination.[47]

Qu'ranic schools (also known as duqsi) remain the basic system of traditional religious instruction in Somalia. They provide Islamic education for children, thereby filling a clear religious and social role in the country. Known as the most stable local, non-formal system of education providing basic religious and moral instruction, their strength rests on community support and their use of locally-made and widely available teaching materials. The Qu'ranic system, which teaches the greatest number of students relative to other educational sub-sectors, is oftentimes the only system accessible to Somalis in nomadic as compared to urban areas. A study from 1993 found, among other things, that "unlike in primary schools where gender disparity is enormous, around 40 per cent of Qur'anic school pupils are girls; but the teaching staff have minimum or no qualification necessary to ensure intellectual development of children." To address these concerns, the Somali government on its own part subsequently established the Ministry of Endowment and Islamic Affairs, under which Qur'anic education is now regulated.[48]

In the Somali diaspora, multiple Islamic fundraising events are held every year in cities like Toronto and Minneapolis, where Somali scholars and professionals give lectures and answer questions from the audience. The purpose of these events is usually to raise money for new schools or universities in Somalia, to help Somalis that have suffered as a consequence of floods and/or droughts, or to gather funds for the creation of new mosques like the Abuubakar-As-Saddique Mosque, which is currently undergoing construction in the Twin cities.

In addition, the Somali community has produced numerous important Muslim figures over the centuries, many of whom have significantly shaped the course of Islamic learning and practice in the Horn of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula and well beyond.

Important Islamic figures

- Sheikh Uways Al-Barawi (1847–1909) – Somali scholar credited with reviving Islam in 19th century East Africa and with followers in Yemen and Indonesia.

- Sa'id of Mogadishu – 14th century Somali scholar and traveler. His reputation as a scholar earned him audiences with the Amirs of Mecca and Medina. He travelled across the Muslim world and visited Bengal and China.

- Nur ibn Mujahid – 16th century Somali conqueror and Patron saint of Harar.

- Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti (1753-1825) – Somali scholar living in Cairo that recorded the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt.

- Shaykh Abd Al-Rahman bin Ahmad al-Zayla'i (1820–1882) – Somali scholar who played a crucial role in the spread of the Qadiriyyah movement in Somalia and East Africa.

- Ahmed Gurey (c. 1507 - February 21, 1543) – 16th century Imam and military leader that led the Conquest of Ethiopia.

- Ali al-Jabarti (d.1492) – 16th century Somali scholar and politician in the Mamluk Empire.

- Shaykh Muhammad Al-Sumaalee (b. 1910-2005) – Somali scholar and teacher in the Masjid Al-Haram in Mecca. He influenced many of the prominent Islamic scholars of today.

- Uthman bin Ali Zayla'i – 14th century Somali theologian and jurist who wrote the single most authoritative text on the Hanafi school of Islam, consisting of four volumes known as the Tabayin al-Haqa’iq li Sharh Kanz al-Daqa’iq.

- Abdallah al-Qutbi (1879–1952) – Somali polemicist theologian and philosopher.

- Hassan al-Jabarti (d.1774) – Somali mathematician, theologian, astronomer and philosopher, considered one of the great scholars of the 18th century.

- Shaykh Sufi (1829–1904) – 19th century Somali scholar, poet, reformist and astrologist.

- Abd al Aziz al-Amawi (1832–1896) – 19th century influential Somali diplomat, historian, poet, jurist and scholar living in the Sultanate of Zanzibar.

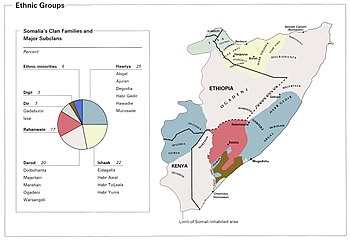

Clan and family structure

The clan groupings of the Somali people are important social units, and clan membership plays a central part in Somali culture and politics. Clans are patrilineal and are often divided into sub-clans, sometimes with many sub-divisions.

Somali society is traditionally ethnically endogamous, so to extend ties of alliance, marriage is often to another ethnic Somali from a different clan. Thus, for example, a recent study observed that in 89 marriages contracted by men of the Dhulbahante clan, 55 (62%) were with women of Dhulbahante sub-clans other than those of their husbands; 30 (33.7%) were with women of surrounding clans of other clan families (Isaaq, 28; Hawiye, 3); and 3 (4.3%) were with women of other clans of the Darod clan family (Majerteen 2, Ogaden 1).[49]

Major Somali clans include:

Geographic distribution

Somalis constitute the largest ethnic group in Somalia, at approximately 85% of the nation's inhabitants.[50] They are traditionally nomads, but since the late 20th century, many have moved to urban areas. While most Somalis can be found in Somalia proper, large numbers also live in Ethiopia, Yemen, Djibouti, the Middle East, South Asia and Europe due to their seafaring tradition.

Civil strife in the early 1990s greatly increased the size of the Somali diaspora, as many of the best educated Somalis left for the Middle East, Europe and North America.[51] In Canada, the cities of Toronto, Ottawa, Calgary, Edmonton, Montreal, Vancouver, Winnipeg and Hamilton all harbor Somali populations. Statistics Canada's 2006 census ranks people of Somali descent as the 69th largest ethnic group in Canada.[5]

While the distribution of Somalis per country in Europe is hard to measure because the Somali community on the continent has grown so quickly in recent years, the official 2001 UK census reported 43,515 Somalis living in the United Kingdom.[4] Somalis in Britain are largely concentrated in the cities of London, Sheffield, Birmingham, Cardiff, Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, and Leicester, with London alone accounting for roughly 78% of Britain's Somali population.[4] There are also significant Somali communities in Norway: 25,496 (2010)[8]; the Netherlands: 19,549 (2008)[10]; and Denmark: 16,550 (2008).[11]

In the United States, Minneapolis, Saint Paul, Columbus, San Diego, Seattle, Washington, D.C., Atlanta, Los Angeles, Portland, Denver, Nashville, Lewiston, Portland, Maine and Cedar Rapids have the largest Somali populations.

An estimated 20,000 Somalis emigrated to the US State of Minnesota some ten years ago. The Twin Cities now have the highest population of Somalis in North America.[52] The city of Minneapolis hosts hundreds of Somali-owned and operated businesses. Colorful stalls inside several shopping malls offer everything from halal meat, to stylish leather shoes, to the latest fashion for men and women, as well as gold jewelry, money transfer or hawala offices, banners advertising the latest Somali films, and video stores fully stocked with nostalgic love songs not found in the mainstream supermarkets, groceries, and boutiques.[53] The number of Somalis has especially surged in the Cedar-Riverside area (in particular, Riverside Plaza) of Minneapolis.

Somalis now comprise one of the largest immigrant communities in the United Arab Emirates. Somali-owned businesses line the streets of Deira, the Dubai city centre,[54] with only Iranians exporting more products from the city at large.[55] Internet cafés, hotels, coffee shops, restaurants and import-export businesses are all testimony to the Somalis' entrepreneurial spirit. Star African Air is also one of three Somali-owned airlines which are based in Dubai.[54]

Notable individuals of the diaspora

- Abdirashid Duale – award-winning Somali entrepreneur, philantropist, and the CEO of the multinational enterprise Dahabshiil.

- Abdulqawi Yusuf – Prominent Somali international lawyer and judge with the International Court of Justice.

- Ali Said Faqi – Somali scientist and the leading researcher on the design and interpretation of toxicology studies at the MPI research center in Mattawan, Michigan.

- Amina Moghe Hersi – Award-winning Somali entrepreneur that has launched several multi-million dollar projects in Kampala, Uganda, such as the Oasis Centre luxury mall and the Laburnam Courts. She also runs Kingstone Enterprises Limited, one of the largest distributors of cement and other hardware materials in Kampala.

- Ayub Daud – Somali international footballer who plays as a forward/attacking midfielder for FC Crotone on loan from Juventus.

- Hawa Ahmed – Somali-Swedish fashion model and winner of Cycle 4 of Sweden's Next Top Model.

- Iman Mohamed Abdulmajid – international fashion icon, supermodel, actress and entrepreneur; professionally known as Iman.

- Liban Abdi – Somali international footballer. Currently plays for Ferencvárosi Torna Club in the Hungarian First Division, on loan from Sheffield United of England.

- Mo Farah – Somali-British gold medalist in international track and field. He currently holds the British indoor record in the 3000 metre and won the 3000m at the 2009 European Indoor Championships in Turin.

- Mustafa Mohamed – Somali-Swedish long-distance runner who mainly competes in the 3000 meter steeplechase. Won gold in the 2006 Nordic Cross Country Championships and at the 1st SPAR European Team Championships in Leiria, Portugal in 2009. Beat the 31 year old Swedish record in 2007.

- Omar Abdi Ali – Somali entrepreneur, accountant, financial consultant, philanthropist, and leading specialist on Islamic finance. Was formerly CEO of Dar al-Maal al-Islami (DMI Trust), which under his management increased its assets from $1.6 billion USD to $4.0 billion USD. He is currently the chairman and founder of the multinational real estate corporation Integrated Property Investments Limited and its sister company Quadron investments.

- Rageh Omaar – Somali-British television news presenter and writer. Formerly a BBC news correspondent in 2009, he moved to a new post at Al Jazeera English, where he currently presents the nightly weekday documentary series Witness.

- Warsame Ali – Somali scientist and assistant professor at Prairie View A&M University, specialized in aerospace technology. He has previously worked for NASA.

- Yasmin Warsame – Somali-Canadian model. In 2004, she was named "The Most Alluring Canadian" in a poll by Fashion magazine.

- Zahra Abdulla – Somali politician in Finland. She is a member of the Helsinki City Council, representing the Green League.

Language

The Somali language is a member of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family. Its nearest relatives are the Afar and Oromo languages. Somali is the best documented of the Cushitic languages,[56] with academic studies of it dating from before 1900.

The exact number of speakers of Somali is unknown. One source estimates that there are 7.78 million speakers of Somali in Somalia itself and 12.65 million speakers globally.[58]

The Somali language is spoken by ethnic Somalis in Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Yemen and Kenya, and by the Somali diaspora.

Somali dialects are divided into three main groups: Northern, Benaadir and Maay. Northern Somali (or Northern-Central Somali) forms the basis for Standard Somali. Benaadir (also known as Coastal Somali) is spoken on the Benadir coast from Cadale to south of Merca, including Mogadishu, as well as in the immediate hinterland. The coastal dialects have additional phonemes which do not exist in Standard Somali. Maay is principally spoken by the Digil and Mirifle (Rahanweyn) clans in the southern areas of Somalia.

Since Somali had long lost its ancient script,[57] a number of writing systems have been used over the years for transcribing the language. Of these, the Somali alphabet is the most widely-used, and has been the official writing script in Somalia since the government of former President of Somalia Mohamed Siad Barre formally introduced it in October 1972.[59] The script was developed by the Somali linguist Shire Jama Ahmed specifically for the Somali language, and uses all letters of the English Latin alphabet except p, v and z. Besides Ahmed's Latin script, other orthographies that have been used for centuries for writing Somali include the long-established Arabic script and Wadaad's writing. Indigenous writing systems developed in the twentieth century include the Osmanya, Borama and Kaddare scripts, which were invented by Osman Yusuf Kenadid, Sheikh Abdurahman Sheikh Nuur and Hussein Sheikh Ahmed Kaddare, respectively.[60]

Culture

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Somalia |

|---|

| Culture |

| People |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Politics |

The culture of Somalia is an amalgamation of traditions indigenously developed or accumulated over a timeline spanning several millennia of Somali civilization's interaction through cultural diffusion with neighbouring and far away civilizations such as Ethiopia, Yemen, India and Persia.

The textile-making communities in Somalia are a continuation of an ancient textile industry, as is the culture of wood carving, pottery and monumental architecture that dominates Somali interiors and landscapes. The cultural diffusion of Somali commercial enterprise can be detected in its exotic cuisine, which contains Southeast Asian influences. Due to the Somali people's passionate love for and facility with poetry, Somalia has often been referred to by scholars as a "Nation of Poets" and a "Nation of Bards" including, among others, the Canadian novelist Margaret Laurence.[61]

All of these traditions, including festivals, martial arts, dress, literature, sport and games such as Shax, have immensely contributed to the enrichment of Somali heritage.

Music

Somalis have a rich musical heritage centered on traditional Somali folklore. Most Somali songs are pentatonic; that is, they only use five pitches per octave in contrast to a heptatonic (seven note) scale such as the major scale. At first listen, Somali music might be mistaken for the sounds of nearby regions such as Ethiopia, Sudan or Arabia, but it is ultimately recognizable by its own unique tunes and styles. Somali songs are usually the product of collaboration between lyricists (midho), songwriters (lahan), and singers ('odka or "voice").[62]

Musicians and bands

- Magool (May 2, 1948 - March 19, 2004) – prominent Somali singer considered in Somalia as one of the greatest entertainers of all time.

- Khadija Qalanjo – popular Somali singer in the 1970s and 1980s.

- K'naan – award-winning Somali-Canadian hip hop artist.

- Aar Maanta – UK-based Somali singer, composer, writer and music producer.

- Ali Feiruz – Somali musician from Djibouti; part of the Radio Hargeisa generation of Somali artists.

- Hasan Adan Samatar – popular male artist during the 1970s and 80s

- Maryam Mursal (b. 1950) – famous musician from Somalia; composer and vocalist whose work has been produced by the record label Real World.

- Mohammed Mooge – Somali artist from the Radio Hargeisa generation.

- Abdi Sinimo – prominent Somali artist and inventor of the Balwo musical style.

- Waaberi – Somalia's foremost musical group that toured throughout several countries in Africa and Asia, including Egypt, Sudan and China.

- Abdullahi Qarshe – Somali musician, poet and playwright known for his innovative styles of music which included a wide variety of musical instruments such as the guitar, piano and oud.

Art

Somali art is the artistic culture of the Somali people, both historic and contemporary. These include artistic traditions in pottery, music, architecture, woodcarving and other genres. Somali art is characterized by its aniconism, partly as a result of the vestigial influence of the pre-Islamic mythology of the Somalis coupled with their ubiquitous Muslim beliefs. However, there have been cases in the past of artistic depictions representing living creatures such as the golden birds on the Mogadishan canopies, the ancient rock paintings in northern Somalia, and the plant decorations on religious tombs in southern Somalia, but these are considered rare. Instead, intricate patterns and geometric designs, bold colors and monumental architecture was the norm.

Cinema and theatre

Watching Somali or foreign language musicals and films at the cinema or theatre is considered a popular form of leisure in Somalia. Mogadishu used to host several prestigious film festivals honoring African and Middle Eastern films. In 1988, Somali film director Abdulkadir Ahmed Said released a short film entitled Geedka nolosha ("Tree of Life"), which earned him an award that year for Best Short Film at the Torino International Festival of Young Cinema. More recently, the diasporic Somali film industry, also known as Somalywood, has begun to take shape (particularly in Columbus, Ohio) and is becoming quite popular in the overseas Somali communities as well as back in Somalia.[63] The Somali directors Mohameddeq Ali, AbdiMalik Isak and Abdisalan Aato are at the forefront of this revolution. Somalis are also great fans of Bollywood movies and Somali films are usually a mixture of love stories and Hollywood-oriented action.

Attire

Men

When not dressed in Westernized clothing such as jeans and t-shirts, Somali men typically wear the macawis, which is a sarong-like garment worn around the waist. On their heads, they often wrap a colorful turban or wear the koofiyad, an embroidered fez.

Due to Somalia's proximity to and close ties with the Arabian Peninsula, many Somali men also wear the jellabiya (jellabiyad in Somali), a long white garment common in the Arab world.

Women

During regular, day-to-day activities, women usually wear the guntiino, a long stretch of cloth tied over the shoulder and draped around the waist. In more formal settings such as weddings or religious celebrations like Eid, women wear the dirac, which is a long, light, diaphanous voile dress made of cotton or polyester that is worn over a full-length half-slip and a brassiere.

Married women tend to sport head-scarves referred to as shash, and also often cover their upper body with a shawl known as garbasaar. Unmarried or young women, however, do not always cover their heads. Traditional Arabian garb such as the jilbab is also commonly worn.

Cuisine

Somali cuisine varies from region to region and consists of an exotic mixture of diverse culinary influences. It is the product of Somalia's rich tradition of trade and commerce. Despite the variety, there remains one thing that unites the various regional cuisines: all food is served halal. There are therefore no pork dishes, alcohol is not served, nothing that died on its own is eaten, and no blood is incorporated. Qado or lunch is often elaborate. Varieties of bariis (rice), the most popular probably being basmati, usually serve as the main dish. Spices like cumin, cardamom, cloves, cinnamon and sage are used to aromatize these different rice dishes. Somalis eat dinner as late as 9 pm. During Ramadan, dinner is often served after Tarawih prayers – sometimes as late as 11 pm. Xalwo or halva is a popular confection eaten during special occasions such as Eid celebrations or wedding receptions. It is made from sugar, cornstarch, cardamom powder, nutmeg powder and ghee. Peanuts are also sometimes added to enhance texture and flavor.[64] After meals, homes are traditionally perfumed using frankincense (lubaan) or incense (cuunsi), which is prepared inside an incense burner referred to as a dabqaad.

Literature

Somali scholars have for centuries produced many notable examples of Islamic literature ranging from poetry to Hadith. With the adoption of the Latin alphabet in 1972 to transcribe the Somali language, numerous contemporary Somali authors have also released novels, some of which have gone on to receive worldwide acclaim. Of these modern writers, Nuruddin Farah is probably the most celebrated. Books such as From a Crooked Rib and Links are considered important literary achievements, works which have earned Farah, among other accolades, the 1998 Neustadt International Prize for Literature. Farah Mohamed Jama Awl is another prominent Somali writer who is perhaps best known for his Dervish era novel, Ignorance is the enemy of love.

Authors and poets

- Mohamed Ibrahim Warsame 'Hadrawi' – songwriter, philosopher, and Somali Poet Laureate; also dubbed the Somali Shakespeare.

- Nuruddin Farah (b. 1943) – Somali writer considered one of the greatest contemporary writers in the world.

- Timacade (1920–1973) – prominent Somali poet known for his nationalist poems such as Kana siib Kana Saar.

- Mohamud Siad Togane (b. 1943) – Somali-Canadian poet, professor, and political activist.

- Maxamed Daahir Afrax ) - Somali novelist and playwright. Afrax has published several novels and short stories in Somali and Arabic, and has also written two plays, the first being Durbaan Been ah ("A Deceptive Dream"), which was staged in Somalia in 1979. His major contribution in the field of theatre criticism is Somali Drama: Historical and Critical Study (1987).

- Gaariye (b. 1943) – renowned Somali political poet; started the famous chain poem movement known as Deelley.

- Farah Mohamed Jama Awl – famous Somali author best known for his historical fiction novels.

Law

Somalis for centuries have practiced a form of customary law, which they call Xeer. Xeer is a polycentric legal system where there is no monopolistic agent that determines what the law should be or how it should be interpreted.

The Xeer legal system is assumed to have developed exclusively in the Horn of Africa since approximately the 7th century. There is no evidence that it developed elsewhere or was greatly influenced by any foreign legal system. The fact that Somali legal terminology is practically devoid of loan words from foreign languages suggests that Xeer is truly indigenous.[65]

The Xeer legal system also requires a certain amount of specialization of different functions within the legal framework. Thus, one can find odayal (judges), xeer boggeyaal (jurists), guurtiyaal (detectives), garxajiyaal (attorneys), murkhaatiyal (witnesses) and waranle (police officers) to enforce the law.[66]

Xeer is defined by a few fundamental tenets that are immutable and which closely approximate the principle of jus cogens in international law:[67]

- Payment of blood money (locally referred to as diya)

- Assuring good inter-clan relations by treating women justly, negotiating with "peace emissaries" in good faith, and sparing the lives of socially-protected groups (e.g. children, women, the pious, poets and guests).

- Family obligations such as the payment of dowry, and sanctions for eloping.

- Rules pertaining to the management of resources such as the use of pasture land, water, and other natural resources.

- Providing financial support to married female relatives and newly-weds.

- Donating livestock and other assets to the poor.

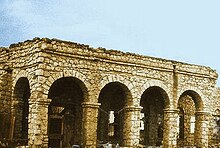

Architecture

| Somali architecture |

|---|

|

Somali architecture is a rich and diverse tradition of engineering and designing multiple different construction types such as stone cities, castles, citadels, fortresses, mosques, temples, aqueducts, lighthouses, towers and tombs during the ancient, medieval and early modern periods in Somalia, as well as the fusion of Somalo-Islamic architecture with Western designs in contemporary times.

In ancient Somalia, pyramidical structures known in Somali as taalo were a popular burial style with hundreds of these drystone monuments scattered around the country today. Houses were built of dressed stone similar to the ones in Ancient Egypt[22] and there are examples of courtyards and large stone walls such as the Wargaade Wall enclosing settlements.

The peaceful introduction of Islam in the early medieval era of Somalia's history brought Islamic architectural influences from Arabia and Persia, which stimulated a shift in construction from drystone and other related materials to coral stone, sundried bricks, and the widespread use of limestone in Somali architecture. Many of the new architectural designs such as mosques were built on the ruins of older structures, a practice that would continue over and over again throughout the following centuries.[68]

Somali studies

The scholarly term for research concerning Somalis and Somalia is known as Somali Studies. It consists of several disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, linguistics, historiography and archaeology. The field draws from old Somali chronicles and oral literature, in addition to written accounts and traditions about Somalis and Somalia from European explorers and neighbouring regions in the Horn of Africa and the Middle East. Since 1980, prominent Somalist scholars from around the world have gathered annually, either in Somalia or a different country, to hold the International Congress of Somali Studies.

Somalist scholars

- Said Sheikh Samatar – Prominent Somali scholar and writer. Main areas of interest are linguistics and sociology.

- Mohamed Haji Mukhtar – Somali Professor of African & Middle Eastern History at Savannah State University. Has written extensively on the history of Somalia and the Somali language.

- Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi – Somali scholar, linguist and writer. Published on Somali culture, history, language and ethnogenesis.

- Ali Jimale Ahmed – Somali poet, essayist, scholar, and short story writer. Published on Somali history and linguistics

- Abdi Mohamed Kusow – Somali Associate Professor of Sociology at Iowa State in Ames, Iowa. Has written extensively on Somali sociology and anthropology.

- Abdisalam Issa-Salwe – Somali Assistant Professor in Information Systems in the Faculty of Computer Science and Engineering at Taibah University in Medina, Saudi Arabia. Is a prominent expert on matters pertaining the Horn of Africa

- Ahmed Ismail Samatar – Prominent Somali professor and dean of the Institute for Global Citizenship at Macalester College. He is the editor of Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies.

See also

References

- ^ a b CIA World Factbook: Somalia, people and Map of the Somalia Ethnic groups (CIA according de Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection). The first gives 15% non-Somalis and the second 6%. Used 90% of current population of Somalia.

- ^ a b Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia, "Census 2007", first draft, Table 5.

- ^ http://www.africa.upenn.edu/NEH/kethnic.htm]

- ^ a b c BBC News with figures from the 2001 Census

- ^ a b Statistics Canada - Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada Highlight Tables, 2006 Census

- ^ The 2000 USA census

- ^ a b Somalia's Missing Million: The Somali Diaspora and its Role in Development

- ^ a b Population 1st January 2009 and 2010 and changes in 2009, by immigrant category and country background

- ^ Statistics Sweden

- ^ a b Statistics Netherlands

- ^ a b StatBank Denmark

- ^ http://www.stat.fi/til/vaerak/2007/vaerak_2007_2008-03-28_tie_001_fi.html

- ^ Official demographic statistics in Italy - ISTAT

- ^ Saheed A. Adejumobi, The History of Ethiopia, (Greenwood Press: 2006), p.178

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica, inc, Encyclopedia Britannica, Volume 1, (Encyclopaedia Britannica: 2005), p.163

- ^ Phoenicia pg 199

- ^ The Aromatherapy Book by Jeanne Rose and John Hulburd pg 94

- ^ Egypt: 3000 Years of Civilization Brought to Life By Christine El Mahdy

- ^ Ancient perspectives on Egypt By Roger Matthews, Cornelia Roemer, University College, London.

- ^ Africa's legacies of urbanization: unfolding saga of a continent By Stefan Goodwin

- ^ Civilizations: Culture, Ambition, and the Transformation of Nature By Felipe Armesto Fernandez

- ^ a b Man, God and Civilization pg 216

- ^ Oman in history By Peter Vine Page 324

- ^ Society, security, sovereignty and the state in Somalia - Page 116

- ^ East Africa: Its Peoples and Resources - Page 18

- ^ Shaping of Somali society Lee Cassanelli pg.92

- ^ Futuh Al Habash Shibab ad Din

- ^ Sudan Notes and Records - Page 147

- ^ Encyclopedia of African history - Page 1406

- ^ I.M. Lewis, The modern history of Somaliland: from nation to state, (Weidenfeld & Nicolson: 1965), p. 78

- ^ Thomas P. Ofcansky, Historical dictionary of Ethiopia, (The Scarecrow Press, Inc.: 2004), p.405

- ^ a b Sanchez et al., High frequencies of Y chromosome lineages characterized by E3b1, DYS19-11, DYS392-12 in Somali males, Eu J of Hum Genet (2005) 13, 856–866

- ^ Cruciani et al., "Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa", Am J Hum Genet. 2004 May; 74(5): 1014–1022

- ^ Underhill et al., "The Levant versus the Horn of Africa: Evidence for Bidirectional Corridors of Human Migrations," American Journal of Human Genetics 74:532-544, 2004

- ^ Cabrera, Vicente M.; Abu-Amero, Khaled K. (2009). "The Arabian peninsula: Gate for Human Migrations Out of Africa or Cul-de-Sac? A Mitochondrial DNA Phylogeographic Perspective". Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology Series. Part 2: 79–87. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2719-1_6.

- ^ Fadhlaoui-Zid, K.; Plaza, S. (2004). "Mitochondrial DNA Heterogeneity in Tunisian Berbers". Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (3): 222–233. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2719-1_6.

- ^ a b c A.D. Holden (2005), MtDNA variation in North, East, and Central African populations gives clues to a possible back-migration from the Middle East, Program of the Seventy-Fourth Annual Meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists (2005)

- ^ Malyarchuk, Boris A.; Gilles, A; Bouzaid, E (2008). "Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Diversity in a Sedentary Population from Egypt". Annals of Human Genetics. 68: 23. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00057.x.

- ^ Malyarchuk, Boris A.; Derenko, Miroslava (2008). "Reconstructing the phylogeny of African mitochondrial DNA lineages in Slavs". European Journal of Human Genetics. 16: 1091–1096. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.70.

- ^ Gonzalez et al., Mitochondrial lineage M1 traces an early human backflow to Africa, BMC Genomics 2007, 8:223 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-8-223

- ^ Ghezzi et al. (2005), Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup K is associated with a lower risk of Parkinson's disease in Italians, European Journal of Human Genetics (2005) 13, 748–752.

- ^ Revathi Rajkumar et al., Phylogeny and antiquity of M macrohaplogroup inferred from complete mt DNA sequence of Indian specific lineages, BMC Evolutionary Biology 2005, 5:26 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-26

- ^ Comas et al. from (1999), Analysis of mtDNA HVRII in several human populations using an immobilised SSO probe hybridisation assay, Eur J Hum Genet. 1999 May-Jun;7(4):459-68.

- ^ Risch et al. (1999), Categorization of humans in biomedical research: genes, race and disease, Genome Biol. 2002; 3(7): comment2007.1–comment2007.12.

- ^ a b Tishkoff et al. (2000). "Short Tandem-Repeat Polymorphism/Alu Haplotype Variation at the PLAT Locus: Implications for Modern Human Origins". Am J Hum Genet; 67:901-925

- ^ Middle East Policy Council - Muslim Populations Worldwide

- ^ Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, Culture and Customs of Somalia, (Greenwood Press: 2001), p.1

- ^ Koranic School Project

- ^ Ioan M. Lewis, Blood and Bone: The Call of Kinship in Somali Society, (Red Sea Press: 1994), p.51

- ^ "Somalia". World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2009-05-14. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ^ Somali Diaspora

- ^ Mosedale, Mike (February 18, 2004), "The Mall of Somalia", City Pages

- ^ Talking Point by M.M. Afrah Minneapolis, Minnesota (USA) Aug., 12. 2004

- ^ a b Somalis cash in on Dubai boom from the BBC

- ^ Forget piracy, Somalia's whole 'global' economy is booming - to Kenya's benefit

- ^ A software tool for research in linguistics and lexicography: Application to Somali

- ^ a b Ministry of Information and National Guidance, Somalia, The writing of the Somali language, (Ministry of Information and National Guidance: 1974), p.5

- ^ Ethnologue: Somalia Ethnologue.com

- ^ Economist Intelligence Unit (Great Britain), Middle East annual review, (1975), p.229

- ^ David D. Laitin, Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience, (University Of Chicago Press: 1977), pp.86-87

- ^ Diriye, p.75

- ^ Diriye, pp.170-171

- ^ Smith, Sara (2007-04-19). "Somaliwood: Columbus has become a haven for Somali filmmaking". Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ^ Barlin Ali, Somali Cuisine, (AuthorHouse: 2007), p.79

- ^ http://www.mises.org/story/2701

- ^ http://www.hiiraan.com/op2/2008/oct/back_to_somali_roots.aspx

- ^ Dr Andre Le Sage (2005-06-01). "Stateless Justice in Somalia" (PDF). Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ^ Diriye, p.102