Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

| Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade | |

|---|---|

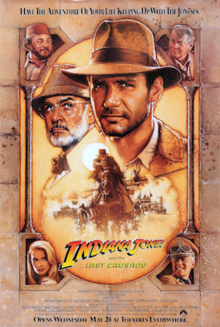

Theatrical release poster by Drew Struzan | |

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Screenplay by | Jeffrey Boam |

| Story by | |

| Based on | |

| Produced by | Robert Watts |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Douglas Slocombe |

| Edited by | Michael Kahn |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 128 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $48 million[1] |

| Box office | $474.2 million[1] |

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade is a 1989 American action adventure film directed by Steven Spielberg from a screenplay by Jeffrey Boam, based on a story by George Lucas and Menno Meyjes. It is the third installment in the Indiana Jones film series and the sequel to Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). Harrison Ford returned in the title role, while his father is portrayed by Sean Connery. Other cast members featured include Alison Doody, Denholm Elliott, Julian Glover, River Phoenix, and John Rhys-Davies. In the film, set in 1938, Indiana Jones searches for his father, a Holy Grail scholar, who has been kidnapped and held hostage by the Nazis while on a journey to find the Holy Grail.

After the criticism that Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) received, Spielberg chose to make a more lighthearted film for the next installment, as well as bringing back several elements from Raiders of the Lost Ark. During the five years between Temple of Doom and The Last Crusade, he and executive producer Lucas reviewed several scripts before accepting Jeffrey Boam's. Filming locations included Spain, Italy, West Germany, Jordan, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[2]

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade was released in the United States on May 24, 1989, by Paramount Pictures. The film received positive reviews, especially for the humor, direction, musical score, story, emotional themes, and performances (particularly those of Ford and Connery), and was a financial success, earning over $474 million worldwide, making it the highest-grossing film of 1989. It also won the Academy Award for Best Sound Effects Editing and was nominated for Best Original Score and Best Sound at the 62nd Academy Awards. A sequel, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, followed in May 2008, while a fifth and final film, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, was released in June 2023.

Plot

[edit]In 1912, Boy Scout Indiana Jones lives with his father Henry Jones Sr. in Moab, Utah. One day, while undergoing a cave exploration, Indy takes a crucifix owned by Coronado from a group of graverobbers led by a man named Garth, and after a brief horse chase, flees to his home, where Garth and his men find him and retrieve the crucifix. Garth, however, admits his respect towards Indiana and gives him his fedora before leaving.

In 1938, Indy successfully takes back the crucifix from the employer of the graverobbers off the Portuguese coast. After returning to the United States, Indy learns Henry has disappeared while searching for the Holy Grail. Walter Donovan, his father's financial backer, tasks Indy with finding both Henry and the Grail. Indy receives a package containing Henry's diary, which includes his research on the Grail, and travels to Venice alongside Marcus Brody to meet Henry's associate Elsa Schneider. Beneath the library where Henry was last seen, Indy and Elsa discover a catacomb containing an inscribed shield which reveals that the path to the Grail begins in Alexandretta. The two are subsequently attacked by a mysterious group who reveal themselves to be the secret Order of the Cruciform Sword, dedicated to protecting the Grail. After saving the group's leader Kazim, Indy learns that Henry is being held at a castle in Austria. Indy entrusts Marcus with a map from the diary detailing a route to the Grail and sends him to Alexandretta to rendezvous with their old friend Sallah. Discovering their rooms have been ransacked, Indy reveals the diary's existence to Elsa before they sleep together.

In Austria, Indy and Elsa infiltrate the castle, discovering it to be under Nazi control. Indy finds Henry and tries to escape, but surrenders after Elsa is held captive by the Nazis. She reveals herself to be a Nazi collaborator and takes the diary, and Indy and Henry are tied up and learn that Donovan is also working with the Nazis. After arriving in Alexandretta, Marcus is captured by the Nazis as well. Elsa returns to Germany, while Indy and Henry escape the castle before traveling to Berlin to retrieve the diary. After recovering it from Elsa, Indy and Henry flee on a zeppelin before evading two Luftwaffe planes pursuing them.

Once Indy and Henry arrive in Hatay, Sallah informs them that the Nazis have also traveled there using the map. While they are following the trail, the Nazis are attacked by the Order but defeat them. Henry takes advantage of the distraction to try to rescue Marcus but is captured; Indy attacks the Nazi convoy in response and is eventually able to destroy it with help from Henry and Marcus. Indy, Henry, Marcus and Sallah proceed to a temple containing the Grail, where they observe the Nazis attempting to overcome the temple's traps before being captured. Donovan forces Indy to find safe passage for them by mortally wounding Henry; a drink from the Grail can heal him. With the help of the diary, Indy overcomes the traps and finds a room with many cups and an ancient knight, who explains that only one cup is the true Grail. Donovan and Elsa enter the room, and Elsa deliberately gives him the wrong cup, killing Donovan after he drinks from it. Indy identifies the true Grail and rescues Henry. Elsa falls to her death when her attempt to leave with the Grail causes the temple to collapse, and Indy nearly suffers the same fate before Henry saves him. The Grail falls into an abyss as Indy and his companions escape and ride off into the sunset.

Cast

[edit]- Harrison Ford as Henry "Indiana" Jones Jr.: An archaeologist, professor and adventurer who seeks to rescue his father and find the Holy Grail. Ford said he loved the idea of introducing Indiana's father because it allowed him to explore another side to Indiana's personality: "These are men who have never made any accommodation to each other. Indy behaves differently in his father's presence. Who else would dare call Indy 'junior'?"[3]

- River Phoenix as a younger Indiana Jones. Phoenix had portrayed the son of Ford's character in The Mosquito Coast (1986). Ford recommended Phoenix for the part; he said that of the young actors working at the time, Phoenix looked the most like him when he was around that age.[4]

- Sean Connery as Henry Jones Sr.: Indiana's father, a professor of medieval literature who cared more about looking for the Grail than raising his son. Spielberg had Connery in mind when he suggested introducing Indiana's father, though he did not tell Lucas at first. Consequently, Lucas wrote the role as "a crazy, eccentric" professor resembling Laurence Olivier, whose relationship with Indiana is "strict schoolmaster and student rather than a father and son".[5] Spielberg had been a fan of Connery's work as James Bond and felt that no one else could perform the role as well.[6] Spielberg biographer Joseph McBride wrote, "Connery was already the father of Indiana Jones since the series had sprung from the desire of Lucas and Spielberg to rival (and outdo) Connery's James Bond films."[7] Gregory Peck was also considered for the role.[4] Connery, who had eschewed major franchise films since his work on the James Bond series, as he found those roles dull and wanted to avoid paparazzi attention, initially turned the role down (as he was only twelve years older than Ford) but eventually relented. Connery—a student of history—began to reshape the character, and revisions were made to the script to address his concerns. "I wanted to play Henry Jones as a kind of Richard Francis Burton," Connery commented. "I was bound to have fun with the role of a gruff, Victorian Scottish father."[6] Connery believed Henry should be a match for his son, telling Spielberg that "whatever Indy'd done my character has done and my character has done it better".[4] Connery signed to the film on March 25, 1988.[5] He improvised the line, "She talks in her sleep", which was left in because it made everyone laugh;[8] in Boam's scripts, Henry telling Indiana that he slept with Elsa occurs later.[5]

- Alex Hyde-White plays Henry in the film's prologue, though his face is never shown and his lines were dubbed by Connery.

- Denholm Elliott as Marcus Brody: Indiana's bumbling English colleague. Elliott returned after Spielberg sought to recapture the tone of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), following the actor's absence in the darker Temple of Doom (1984).[4]

- Alison Doody as Dr. Elsa Schneider: An Austrian art professor and Indy's love interest, who is in league with the Nazis. She seduces the Joneses to trick them but seems to be in love with Indy. While the character of Elsa is in her 30s during the film, Doody was 21 when she auditioned and was one of the first actresses who met for the part.[5] Amanda Redman was offered the role, but declined.[9]

- John Rhys-Davies as Sallah: A friend of Indiana and a professional excavator living in Cairo. Like Elliott's, Rhys-Davies's return was an attempt to recapture the spirit of Raiders of the Lost Ark.[4]

- Julian Glover as Walter Donovan: An American businessman who sends the Joneses on their quest for the Holy Grail out of a desire for immortality while secretly working with the Nazis for the same goal. Glover previously appeared as General Veers in Lucas's The Empire Strikes Back. He originally auditioned for the role of Vogel. Glover, who is English, adopted an American accent for the film,[10] but was dissatisfied with the result.[4]

- Michael Byrne portrays Ernst Vogel, a brutal SS colonel. Byrne and Ford had previously starred in Force 10 from Navarone (1978), in which they also respectively played a German and an American.[11]

Kevork Malikyan portrays Kazim, the leader of the Brotherhood of the Cruciform Sword, an organization that protects the Holy Grail. Malikyan had impressed Spielberg with his performance in Midnight Express (1978) and would have auditioned for the role of Sallah in Raiders of the Lost Ark had a traffic jam not delayed his meeting with the director.[11] Robert Eddison appears as the Grail Knight, the guardian of the Grail who drank from the cup of Christ during the Crusades. Eddison was a stage and television veteran only appearing in a few films since the 1930s (including a supporting role in Peter Ustinov's 1948 comedy Vice Versa). Glover recalled Eddison was excited and nervous for his return to film, often asking if he had performed correctly.[12] Laurence Olivier was originally considered to play the Grail Knight,[13] but he was too ill and died the same year in which the film was released.

Michael Sheard appears as Adolf Hitler, whom Jones briefly encounters at the book-burning rally in Berlin. Although a non-speaking role, Sheard could speak German and had already portrayed Hitler three times during his career. He had also appeared as Admiral Ozzel in The Empire Strikes Back and as Oskar Schomburg in Raiders of the Lost Ark. In the same scene, Ronald Lacey, who played Toht in Raiders of the Lost Ark, cameos as Heinrich Himmler. Alexei Sayle played the sultan of Hatay. Paul Maxwell portrayed "the man with the Panama Hat" who took possession of the Cross of Coronado. Wrestler and stuntman Pat Roach, who played three roles in the previous two films, made a short cameo as the Nazi who accompanies Vogel to the Zeppelin. Roach was set to film a fight with Ford, but it was cut. In a deleted scene, Roach's agent boards the second biplane on the Zeppelin with a World War I flying ace (played by Frederick Jaeger), only for the pair to fall to their deaths after the flying ace makes an error. Richard Young played Garth, the leader of the tomb robbers who chased young Indiana Jones and then gives him his hat. Eugene Lipinski portrayed the mysterious agent G-Man, while Vernon Dobtcheff appeared as the butler of Castle Brunwald.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]George Lucas and Steven Spielberg had intended to make a trilogy of Indiana Jones films since Lucas had first pitched Raiders of the Lost Ark to Spielberg in 1977,[14] though they signed for five films with Paramount Pictures by 1979.[15] After the mixed critical and public reaction to Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Spielberg decided to complete the trilogy to fulfill his promise to Lucas, with the intent to invoke the film with the spirit and tone of Raiders of the Lost Ark.[16] Temple of Doom writers Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz chose not to return due to both having other commitments and feeling satisfied with their work in the second film.[17] Throughout the film's development and pre-production, Spielberg admitted he was "consciously regressing" in making the film.[7] Due to his commitment to the film, the director had to drop out of directing Big and Rain Man.[14]

Lucas initially suggested making the film "a haunted mansion movie", for which Romancing the Stone writer Diane Thomas wrote a script. Spielberg rejected the idea because of the similarity to Poltergeist, which he had co-written and produced.[7] Lucas first introduced the Holy Grail in an idea for the film's prologue, which was to be set in Scotland. He intended the Grail to have a pagan basis, with the rest of the film revolving around a separate Christian artifact in Africa. Spielberg did not care for the Grail idea, which he found too esoteric,[3] even after Lucas suggested giving it healing powers and the ability to grant immortality (much like the fictional magical power given to the Ark in the first film of the trilogy). In September 1984, Lucas completed an eight-page treatment titled Indiana Jones and the Monkey King, which he soon followed with an 11-page outline. The story saw Indiana battling a ghost in Scotland before finding the Fountain of Youth in Africa.[5]

Chris Columbus—who had written the Spielberg-produced Gremlins, The Goonies, and Young Sherlock Holmes—was hired to write the script. His first draft, dated May 3, 1985, changed the main plot device to a Garden of Immortal Peaches. It begins in 1937, with Indiana battling the murderous ghost of Baron Seamus Seagrove III in Scotland. Indiana travels to Mozambique to aid Dr. Clare Clarke (a Katharine Hepburn-type according to Lucas), who has found a 200-year-old pygmy. The pygmy is kidnapped by the Nazis during a boat chase, and Indiana, Clare and Scraggy Brier—an old friend of Indiana—travel up the Zambezi river to rescue him. Indiana is killed in the climactic battle but is resurrected by the Monkey King. Other characters include a cannibalistic African tribe; Nazi Sergeant Gutterbuhg, who has a mechanical arm; Betsy, a stowaway student who is suicidally in love with Indiana; and a pirate leader named Kezure (described as a Toshiro Mifune-type), who dies eating a peach because he is not pure of heart.[5]

Columbus's second draft, dated August 6, 1985, removed Betsy and featured Dash—an expatriate bar owner for whom the Nazis work—and the Monkey King as villains. The Monkey King forces Indiana and Dash to play chess with real people and disintegrates each person who is captured. Indiana subsequently battles the undead, destroys the Monkey King's rod, and marries Clare.[5] Location scouting commenced in Africa but Spielberg and Lucas abandoned Monkey King because of its negative depiction of African natives,[18] and because the script was too unrealistic.[5] Spielberg acknowledged that it made him "... feel very old, too old to direct it."[3] Columbus's script was leaked onto the Internet in 1997, and many believed it was an early draft for the fourth film because it was mistakenly dated to 1995.[19]

Dissatisfied, Spielberg suggested introducing Indiana's father, Henry Jones, Sr. Lucas was dubious, believing the Grail should be the story's focus, but Spielberg convinced him that the father–son relationship would serve as a great metaphor in Indiana's search for the artifact.[7] Spielberg hired Menno Meyjes, who had worked on Spielberg's The Color Purple and Empire of the Sun, to begin a new script on January 1, 1986. Meyjes completed his script ten months later. It depicted Indiana searching for his father in Montségur, where he meets a nun named Chantal. Indiana travels to Venice, takes the Orient Express to Istanbul, and continues by train to Petra, where he meets Sallah and reunites with his father. Together they find the grail. At the climax, a Nazi villain touches the Grail and explodes; when Henry touches it, he ascends a stairway to Heaven. Chantal chooses to stay on Earth because of her love for Indiana. In a revised draft dated two months later, Indiana finds his father in Krak des Chevaliers, the Nazi leader is a woman named Greta von Grimm, and Indiana battles a demon at the Grail site, which he defeats with a dagger inscribed with "God is King". The prologue in both drafts has Indiana in Mexico battling for possession of Montezuma's death mask with a man who owns gorillas as pets.[5]

Spielberg suggested Innerspace writer Jeffrey Boam perform the next rewrite. Boam spent two weeks reworking the story with Lucas, which yielded a treatment that is largely similar to the final film.[5] Boam told Lucas that Indiana should find his father in the middle of the story. "Given the fact that it's the third film in the series, you couldn't just end with them obtaining the object. That's how the first two films ended," he said, "So I thought, let them lose the Grail, and let the father–son relationship be the main point. It's an archaeological search for Indy's own identity and coming to accept his father is more what it's about [than the quest for the Grail]."[7] Boam said he felt there was not enough character development in the previous films.[3] In Boam's first draft, dated September 1987, the film is set in 1939. The prologue has adult Indiana retrieving an Aztec relic for a museum curator in Mexico and features the circus train. Henry and Elsa (who is described as having dark hair) were searching for the Grail on behalf of the Chandler Foundation, before Henry went missing. The character of Kazim is here named Kemal, and is an agent of the Republic of Hatay, which seeks the grail for its own. Kemal shoots Henry and dies drinking from the wrong chalice. The Grail Knight battles Indiana on horseback, while Vogel is crushed by a boulder while attempting to steal the Grail.[5]

Boam's February 23, 1988, rewrite used many of Connery's comic suggestions. It included the prologue that was eventually filmed; because of the mixed response to Empire of the Sun, which was about a young boy, Lucas had to convince Spielberg to show Indiana as a boy.[3] Spielberg—who was later awarded the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award—had the idea of making Indiana a Boy Scout.[14] The 1912 prologue as seen in the film refers to events in the lives of Indiana's creators. When Indiana cracks the bullwhip to defend himself against a lion, he accidentally lashes and scars his chin. Ford gained this scar in a car accident as a young man.[4] Indiana taking his nickname from his pet Alaskan Malamute is a reference to the character being named after Lucas's dog.[20] The train carriage Indiana enters is named "Doctor Fantasy's Magic Caboose", which was the name producer Frank Marshall used when performing magic tricks. Spielberg suggested the idea, Marshall came up with the false-bottomed box through which Indiana escapes,[21] and production designer Elliott Scott suggested the trick be done in a single, uninterrupted shot.[22] Spielberg intended the shot of Henry with his umbrella—after he causes the bird strike on the German plane—to evoke Ryan's Daughter.[20] Indiana's mother, named Margaret in this version, dismisses Indiana when he returns home with the Cross of Coronado, while his father is on a long-distance call. Walter Chandler of the Chandler Foundation features, but is not the main villain; he plunges to his death in the tank. Elsa introduces Indiana and Brody to a large Venetian family that knows Henry. Leni Riefenstahl appears at the Nazi rally in Berlin. Vogel is beheaded by the traps guarding the Grail. Kemal tries to blow up the Grail Temple during a comic fight in which gunpowder is repeatedly lit and extinguished. Elsa shoots Henry, then dies drinking from the wrong Grail, and Indiana rescues his father from falling into the chasm while grasping for the Grail. Boam's revision of March 1 showed Henry causing the seagulls to strike the plane, and has Henry saving Indiana at the end.[5][23]

During an undated "Amblin" revision and a rewrite by Tom Stoppard (under the pen name Barry Watson) dated May 8, 1988,[5] further changes were made. Stoppard polished most of the dialogue,[8][24] and created the "Panama Hat" character to link the prologue's segments featuring the young and adult Indianas. The Venetian family is cut. Kemal is renamed Kazim and now wants to protect the grail rather than find it. Chandler is renamed Donovan. The scene of Brody being captured is added. Vogel now dies in the tank, while Donovan shoots Henry and then drinks from the false grail, and Elsa falls into the chasm. The Grail trials are expanded to include the stone-stepping and leap of faith.[5][25]

Filming

[edit]

Principal photography began on May 16, 1988, in the Tabernas Desert in Spain's Almería province. Spielberg originally had planned the chase to be a short sequence shot over two days, but he drew up storyboards to make the scene an action-packed centerpiece.[4] Thinking he would not surpass the truck chase from Raiders of the Lost Ark (because the truck was much faster than the tank), he felt this sequence should be more story-based and needed to show Indiana and Henry helping each other. He later said he had more fun storyboarding the sequence than filming it.[22] The second unit had begun filming two weeks before.[12] After approximately ten days, the production moved to the Escuela de Arte de Almería, to film the scenes set in the Sultan of Hatay's palace. Cabo de Gata-Níjar Natural Park was used for the road, tunnel and beach sequence (at Playa de Mónsul) in which birds strike the plane. The shoot's Spanish portion wrapped on June 2, 1988, in Guadix, Granada, with filming of Brody's capture at Alexandretta train station.[12] The filmmakers built a mosque near the station for atmosphere, rather than adding it as a visual effect.[22]

The exteriors of "Brunwald Castle" were filmed at Bürresheim Castle in West Germany. In the movie the image of the castle has been flipped and the building was expanded with a Matte painting depicting a copy of the right facade to the left of the main tower. Filming for the castle interiors took place in the United Kingdom from June 5 to 10, 1988, at Elstree Studios in Borehamwood, England. On June 16, Lawrence Hall, London, was used as the interior of Berlin Tempelhof Airport. Filming returned to Elstree the next day to capture the motorcycle escape, continuing at the studio for interior scenes until July 18. One day was spent at North Weald Airfield on June 29 to film Indiana leaving for Venice.[12] Ford and Connery acted much of the Zeppelin table conversation without trousers on because of the overheated set.[20] Spielberg, Marshall and Kennedy interrupted the shoot to make a plea to the Parliament of the United Kingdom to support the economically "depressed" British studios. July 20–22 was spent filming the temple interiors. The temple set, which took six weeks to build, was supported on 80 feet (24 m) of hydraulics and ten gimbals for use during the earthquake scene. Resetting between takes took twenty minutes while the hydraulics were put to their starting positions and the cracks filled with plaster. The shot of the Grail falling to the temple floor—causing the first crack to appear—was attempted on the full-size set, but proved too difficult. Instead, crews built a separate floor section that incorporated a pre-scored crack sealed with plaster. It took several takes to throw the Grail from 6 feet (1.8 m) onto the right part of the crack.[22] July 25–26 was spent on night shoots at Stowe School, Stowe, Buckinghamshire, for the Nazi rally.[12]

Filming resumed two days later at Elstree, where Spielberg swiftly filmed the library, Portuguese freighter, and catacombs sequences.[12] The steamship fight in the prologue's 1938 portion was filmed in three days on a sixty-by-forty-feet (eighteen-by-twelve-meter) deck built on gimbals at Elstree. A dozen dump tanks – each holding three hundred imperial gallons (360 U.S. gallons; 3000 lb.; 1363 liters) of water – were used in the scene.[22] Henry's house was filmed at Mill Hill, London. Indiana and Kazim's fight in Venice in front of a ship's propeller was filmed in a water tank at Elstree. Spielberg used a long focus lens to make it appear the actors were closer to the propeller than they really were.[12] Two days later, on August 4, another portion of the boat chase using Hacker Craft sport boats, was filmed at Tilbury Docks in Essex.[12] The shot of the boats passing between two ships was achieved by first cabling the ships off so they would be safe. The ships were moved together while the boats passed between, close enough that one of the boats scraped the sides of the ships. An empty speedboat containing dummies was launched from a floating platform between the ships amid fire and smoke that helped obscure the platform. The stunt was performed twice because the boat landed too short of the camera in the first attempt.[22] The following day, filming in England wrapped at the Royal Masonic School in Rickmansworth, which doubled for Indiana's college (as it had in Raiders of the Lost Ark).[12]

Shooting in Venice took place on August 8.[12] For scenes such as Indiana and Brody greeting Elsa, shots of the boat chase, and Kazim telling Indiana where his father is,[22] Robert Watts gained control of the Grand Canal from 7 am to 1 pm, sealing off tourists for as long as possible. Cinematographer Douglas Slocombe positioned the camera to ensure no satellite dishes would be visible.[12] San Barnaba di Venezia served as the library's exterior.[4] The next day, filming moved to the ancient city of Petra, Jordan, where Al Khazneh (The Treasury) stood in for the temple housing the Grail. The cast and crew became guests of King Hussein and Queen Noor. The Treasury had previously appeared in Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger. The main cast completed their scenes that week, after 63 days of filming.[12]

The second unit filmed part of the prologue's 1912 segment from August 29 to September 3. The main unit began two days later with the circus train sequence at Alamosa, Colorado, on the Cumbres and Toltec Scenic Railroad. They filmed at Pagosa Springs on September 7, and then at Cortez on September 10. From September 14 to 16, filming of Indiana falling into the train carriages took place in Los Angeles. The production then moved to Utah's Arches National Park to shoot more of the opening. A house in Antonito, Colorado was used for the Jones family home.[26] The production had intended to film at Mesa Verde National Park, but Native American representatives had religious objections to its use.[22] When Spielberg and editor Michael Kahn viewed a rough cut of the film in late 1988, they felt it suffered from a lack of action. The motorcycle chase was shot during post-production at Mount Tamalpais and Fairfax near Skywalker Ranch. The closing shot of Indiana, Henry, Sallah and Brody riding into the sunset was filmed in Amarillo, Texas in early 1989 by the second unit, directed by Frank Marshall.[12][10] Filming ended on September 16, 1988 after 123 days of filming.

Design

[edit]

Mechanical effects supervisor George Gibbs said the film was the most difficult one of his career.[22] He visited a museum to negotiate renting a small French World War I tank, but decided he wanted to make one.[12] The tank was based on the Tank Mark VIII, which was 11 metres (36 ft) long and weighed 28 short tons (25 t). However, some liberties were taken with the design.[27] Gibbs built the tank over the framework of a 28-short-ton (25 t) excavator and added 7-short-ton (6.4 t) tracks that were driven by two automatic hydraulic pumps, each connected to a Range Rover V8 engine. Gibbs built the tank from steel rather than aluminum or fiberglass because it would allow the realistically suspensionless vehicle to endure the rocky surfaces. Unlike its historic counterpart, which had only the two side guns, the tank had a turret gun added as well. It took four months to build and was transported to Almería on a Short Belfast plane and then a low loader truck.[22]

The tank broke down twice. The distributor's rotor arm broke and a replacement had to be sourced from Madrid. Then two of the device's valves used to cool the oil exploded, due to solder melting and mixing with the oil. It was very hot in the tank, despite the installation of ten fans, and the lack of suspension meant the driver was unable to stop shaking during filming breaks.[22] The tank only moved at 10 to 12 miles per hour (16 to 19 km/h), which Vic Armstrong said made it difficult to film Indiana riding a horse against the tank while making it appear faster.[12] A smaller section of the tank's top made from aluminum and which used rubber tracks was used for close-ups. It was built from a searchlight trailer, weighed eight tons, and was towed by a four-wheel drive truck. It had safety nets on each end to prevent injury to those falling off.[22] A quarter-scale model by Gibbs was driven over a 15-metre (50 ft) cliff on location; Industrial Light & Magic created further shots of the tank's destruction with models and miniatures.[28]

Michael Lantieri, mechanical effects supervisor for the 1912 scenes, noted the difficulty in shooting the train sequence. "You can't just stop a train," he said, "If it misses its mark, it takes blocks and blocks to stop it and back up." Lantieri hid handles for the actors and stuntmen to grab onto when leaping from carriage to carriage. The carriage interiors shot at Universal Studios Hollywood were built on tubes that inflated and deflated to create a rocking motion.[22] For the close-up of the rhinoceros that strikes at (and misses) Indiana, a foam and fiberglass animatronic was made in London. When Spielberg decided he wanted it to move, the prop was sent to John Carl Buechler in Los Angeles, who resculpted it over three days to blink, snarl, snort and wiggle its ears. The giraffes were also created in London. Because steam locomotives are very loud, Lantieri's crew would respond to first assistant director David Tomblin's radioed directions by making the giraffes nod or shake their heads to his questions, which amused the crew.[28] For the villains' cars, Lantieri selected a 1914 Ford Model T, a 1919 Ford Model T truck and a 1916 Saxon Model 14, fitting each with a Ford Pinto V6 engine. Sacks of dust were hung under the cars to create a dustier environment.[22]

Spielberg used doves for the seagulls that Henry scares into striking the German plane because the real gulls used in the first take did not fly.[4] In December 1988, Lucasfilm ordered 1,000 disease-free gray rats for the catacombs scenes from the company that supplied the snakes and bugs for the previous films. Within five months, 5,000 rats had been bred for the sequence;[4] 1,000 mechanical rats stood in for those that were set on fire. Several thousand snakes of five breeds—including a boa constrictor—were used for the train scene, in addition to rubber ones onto which Phoenix could fall. The snakes would slither from their crates, requiring the crew to dig through sawdust after filming to find and return them. Two lions were used, which became nervous because of the rocking motion and flickering lights.[22]

Costume designer Anthony Powell found it a challenge to create Connery's costume because the script required the character to wear the same clothes throughout. Powell thought about his own grandfather and incorporated tweed suits and fishing hats. Powell felt it necessary for Henry to wear glasses, but did not want to hide Connery's eyes, so chose rimless ones. He could not find any suitable, so he had them specially made. The Nazi costumes were genuine and were found in Eastern Europe by Powell's co-designer Joanna Johnston, to whom he gave research pictures and drawings for reference.[12] The motorcycles used in the chase from the castle were a mixed bag: the scout model with sidecar in which Indy and Henry escape was an original Dnepr, complete with machine gun pintle on the sidecar, while the pursuing vehicles were more modern machines dressed up with equipment and logos to make them resemble German army models. Gibbs used two Swiss Pilatus P-2 air force training planes standing in as pursuing Luftwaffe Arado Ar 96s for the Zeppelin biplane escape sequence. He built a device based on an internal combustion engine to simulate gunfire, which was safer and less expensive than firing blanks.[28] Baking soda was applied to Connery to create Henry's bullet wound. Vinegar was applied to create the foaming effect as the water from the Grail washes it away.[28] At least one reproduction Kübelwagen was used during filming despite the film being set two years prior to manufacture of said vehicles.[citation needed]

Effects

[edit]Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) built an 8-foot (2.4 m) foam model of the Zeppelin to complement shots of Ford and Connery climbing into the Gotha Go 145C biplane. A biplane model with a 2-foot (0.61 m) wingspan was used for the shot of the biplane detaching. Stop motion animation was used for the shot of the German fighter's wings breaking off as it crashes through the tunnel. The tunnel was a 210 feet (64 m) model that occupied 14 of ILM's parking spaces for two months. It was built in eight-foot sections, with hinges allowing each section to be opened to film through. Ford and Connery were filmed against bluescreen; the sequence required their car to have a dirty windscreen, but to make the integration easier this was removed and later composited into the shot. Dust and shadows were animated onto shots of the plane miniature to make it appear as if it disturbed rocks and dirt before it exploded. Several hundred tim-birds were used in the background shots of the seagulls striking the other plane; for the closer shots, ILM dropped feather-coated crosses onto the camera. These only looked convincing because the scene's quick cuts merely required shapes that suggested gulls.[28] ILM's Wes Takahashi supervised the film's effects sequences.[29]

Spielberg devised the three trials that guard the Grail.[3] For the first, the blades under which Indiana ducks like a penitent man were a mix of practical and miniature blades created by Gibbs and ILM. For the second trial, in which Indiana spells "Iehova" on stable stepping stones, it was intended to have a tarantula crawl up Indiana after he mistakenly steps on "J". This was filmed and deemed unsatisfactory, so ILM filmed a stuntman hanging through a hole that appears in the floor, 30 feet (9.1 m) above a cavern. As this was dark, it did not matter that the matte painting and models were rushed late in production. The third trial, the leap of faith that Indiana makes over an apparently impassable ravine after discovering a bridge hidden by forced perspective, was created with a model bridge and painted backgrounds. This was cheaper than building a full-size set. A puppet of Ford was used to create a shadow on the 9-foot-tall (2.7 m) by 13-foot-wide (4.0 m) model because Ford had filmed the scene against bluescreen, which did not incorporate the shaft of light from the entrance.[28]

Spielberg wanted Donovan's death shown in one shot, so it would not look like an actor having makeup applied between takes. Inflatable pads were applied to Julian Glover's forehead and cheeks by Nick Dudman that made his eyes seem to recede during the character's initial decomposition, as well as a mechanical wig that grew his hair. The shot of Donovan's death was the first all-digital composite scene in a movie,[30] and was created over three months by morphing together three puppets of Donovan created by Stephan Dupuis in separate stages of decay, a technique ILM mastered on Willow (1988).[20] A fourth puppet was used for the decaying clothes, because the puppet's torso mechanics had been exposed. Complications arose because Alison Doody's double had not been filmed for the scene's latter two elements, so the background and hair from the first shot had to be used throughout, with the other faces mapped over it. Donovan's skeleton was hung on wires like a marionette; it required several takes to film it crashing against the wall because not all the pieces released upon impact.[28]

Ben Burtt designed the sound effects. He recorded chickens for the sounds of the rats,[12] and digitally manipulated the noise made by a Styrofoam cup for the castle fire. He rode in a biplane to record the sounds for the dogfight sequence, and visited the demolition of a wind turbine for the plane crashes.[28] Burtt wanted an echoing gunshot for Donovan wounding Henry, so he fired a .357 Magnum in Skywalker Ranch's underground car park, just as Lucas drove in.[12] A rubber balloon was used for the earthquake tremors at the temple.[31] The film was released in selected theaters in the 70 mm Full-Field Sound format, which allowed sounds to not only move from side to side, but also from the theater's front to its rear.[28]

Matte paintings of the Austrian castle and the Berlin airport were based on real buildings; the Austrian castle "Schloss Brunwald" is Bürresheim Castle near Mayen in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, that was made to look larger. Rain was created by filming granulated Borax soap against black at high speed. It was only lightly double exposed into the shots so it would not resemble snow. The lightning was animated. The Administration Building at San Francisco's Treasure Island was used as the exterior of Berlin Tempelhof Airport. The structure already had period-appropriate art deco architecture, as it had been constructed in 1938 for planned use as an airport terminal. ILM added a control tower, Nazi banners, vintage automobiles and a sign stating "Berlin Flughafen". The establishing shot of the Hatayan city at dusk was created by filming silhouetted cutouts that were backlit and obscured by smoke. Matte paintings were used for the sky and to give the appearance of fill light in the shadows and rim light on the edges of the buildings.[28]

Themes

[edit]A son's relationship with his estranged father is a common theme in Spielberg's films, including E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Hook.[7]

The film's exploration of fathers and sons coupled with its use of religious imagery is comparable to two other 1989 films, Star Trek V: The Final Frontier and Field of Dreams. Writing for The New York Times, Caryn James felt the combination in these films reflected New Age concerns, where the worship of God was equated to searching for fathers. James felt that neither Indiana nor his father is preoccupied with finding the Grail or defeating the Nazis, but that, rather, both seek professional respect for one another in their boys' own adventure. James contrasted the temple's biblically epic destruction with the more effective and quiet conversation between the Joneses at the film's end. James noted that Indiana's mother does not appear in the prologue, being portrayed as already having died before the film's events began.[32]

Release

[edit]Marketing

[edit]The film's teaser trailer debuted in November 1988 with Scrooged and The Naked Gun.[33] Rob MacGregor wrote the tie-in novelization that was released in June 1989;[34] it sold enough copies to be included on the New York Times Best Seller list.[35] MacGregor went on to write the first six Indiana Jones prequel novels during the 1990s. Following the film's release, Ford donated Indiana's fedora and jacket to the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History.[36]

No toys were made to promote the film; Indiana Jones "never happened on the toy level", said Larry Carlat, senior editor of the journal Children's Business. Rather, Lucasfilm promoted Indiana as a lifestyle symbol, selling tie-in fedoras, shirts, jackets and watches.[37] Two video games based on the film were released by LucasArts in 1989: Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Graphic Adventure and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: The Action Game. A third game was produced by Taito and released in 1991 for the Nintendo Entertainment System. Ryder Windham wrote another novelization, released in April 2008 by Scholastic, to coincide with the release of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Hasbro released toys based on The Last Crusade in July 2008.[38]

Box office

[edit]The film was released in the United States and Canada on Wednesday, May 24, 1989, in 2,327 theaters, earning a record $37,031,573 over the 4-day Memorial Day weekend.[39] The gross was boosted by high ticket prices in some venues ($7 a ticket).[40] Its 3-day opening weekend figure of $29,355,021[41] was surpassed later that year by Ghostbusters II and Batman, which grossed more in its opening 3 days than The Last Crusade in 4.[42] The film would hold the record for having the highest Memorial Day weekend gross until 1994 when The Flintstones took it.[43] Additionally, it had the largest opening weekend for a Harrison Ford film for eight years until Air Force One surpassed it in 1997.[44] Its Saturday gross of $11,181,429 was the first time a film had made over $10 million in one day. It broke the record for the best seven-day performance with a gross of $50.2 million,[45] beating the $45.7 million grossed by Temple of Doom in 1984 on 1,687 screens.[40] It added another record with $77 million after twelve days, and earned $100 million in a record nineteen days.[46] In France, the film broke a record by selling a million admissions within two and a half weeks.[36] In the UK it opened in three London theaters before opening two days later on 361 screens nationally, setting an opening weekend record of £1,811,542 ($2,862,200), breaking the one set the year before by Crocodile Dundee II.[47][48] It spent six weeks at number one in the UK.[49]

The film eventually grossed $197,171,806 in the United States and Canada and $277 million internationally, for a worldwide total of $474,171,806.[1] At the time of its release, the film was the 11th highest-grossing film of all time. Despite competition from Batman, The Last Crusade became the highest-grossing film worldwide in 1989.[50] In North America, Batman took top position.[42] Behind Kingdom of the Crystal Skull and Raiders, The Last Crusade is the third-highest grossing Indiana Jones film in the United States and Canada, though it is also behind Temple of Doom when adjusting for inflation.[51] Box Office Mojo estimates that the film sold over 49 million tickets in North America.[52] The film was re-released in 1992 earning $139,000.[1]

Home media

[edit]The film was released along with its two predecessors as part of a trilogy DVD box set in 2003. It contained extra materials and a special documentary covering the production of the films. Sales figures for the box set were extremely successful and 600,000 copies were sold in the US on the first day of release.[53] In 2012, the film was released on Blu-ray along with the three other films in the Indiana Jones film series at the time.[54] In 2021, a remastered 4K version of the film was released on Ultra HD Blu-ray, produced using scans of the original negatives. It was released as part of a box set for the then four films in the Indiana Jones film series.[55]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]On Rotten Tomatoes, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade has an approval rating of 84% based on 136 reviews, with an average rating of 8/10. The site's critics consensus reads, "Lighter and more comedic than its predecessor, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade returns the series to the brisk serial adventure of Raiders, while adding a dynamite double act between Harrison Ford and Sean Connery."[56] Metacritic calculated a weighted average score of 65 out of 100 based on 14 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[57] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[58]

Jay Boyar of the Orlando Sentinel said that while the film "lacks the novelty of Raiders, and the breathless pacing of Temple of Doom, it was an entertaining capper to the trilogy."[59] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone remarked the film was "the wildest and wittiest Indy of them all". Richard Corliss of Time and David Ansen of Newsweek praised it, as did Vincent Canby of The New York Times.[12] "Though it seems to have the manner of some magically reconstituted B-movie of an earlier era, The Last Crusade is an endearing original," Canby wrote, calling the revelation that Jones had a father who was not proud of him to be a "comic surprise". Canby believed that while the film did not match the previous two in its pacing, it still had "hilariously off-the-wall sequences" such as the circus train chase. He also said that Spielberg was maturing by focusing on the father–son relationship,[60] a call echoed by McBride in Variety.[61] Roger Ebert praised the sequence depicting Jones as a Boy Scout with the Cross of Coronado, comparing it to the "style of illustration that appeared in the boys' adventure magazines of the 1940s". He said that Spielberg "must have been paging through his old issues of Boys' Life magazine...the feeling that you can stumble over astounding adventures just by going on a hike with your Scout troop. Spielberg lights the scene in the strong, basic colors of old pulp magazines."[62] The Hollywood Reporter felt Connery and Ford deserved Academy Award nominations.[12]

It was panned by Andrew Sarris in The New York Observer, David Denby in New York magazine, Stanley Kauffmann in The New Republic and Georgia Brown in The Village Voice.[12] Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader called the film "soulless".[63] The Washington Post reviewed the film twice; Hal Hinson's review on the day of the film's release was negative, describing it as "nearly all chases and dull exposition". Although he praised Ford and Connery, he felt the film's exploration of Jones's character took away his mystery and that Spielberg should not have tried to mature his storytelling.[64] Two days later, Desson Thomson published a positive review praising the film's adventure and action, as well as the father–son relationship's thematic depth.[65]

Influence

[edit]The film won the Academy Award for Best Sound Effects Editing; it also received nominations for Best Original Score and Best Sound (Ben Burtt, Gary Summers, Shawn Murphy and Tony Dawe), but lost to The Little Mermaid and Glory respectively.[66] Connery received a Golden Globe Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor.[67] Connery and the visual and sound effects teams were also nominated at the 43rd British Academy Film Awards.[68] The film won the 1990 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation,[69] and was nominated for Best Motion Picture Drama at the Young Artist Awards.[70] John Williams's score won a Broadcast Music Incorporated Award, and was nominated for a Grammy Award.[71]

The prologue depicting Jones in his youth inspired Lucas to create The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles television series, which featured Sean Patrick Flanery as the young adult Indiana and Corey Carrier as the 8- to 10-year-old Indiana.[10] According to Dark Horse Comics author Lee Marrs, Lucasfilm considered for a while to make a continuation to the film series starring Phoenix as a younger Jones, but these plans were dropped after his untimely death.[72] The 13-year-old incarnation played by Phoenix in the film was the focus of a Young Indiana Jones series of young adult novels that began in 1990;[73] by the ninth novel, the series had become a tie-in to the television show.[74] German author Wolfgang Hohlbein revisited the prologue in one of his novels, in which Jones encounters the lead grave robber—whom Hohlbein christens Jake—in 1943.[75] The film's ending begins the 1995 comic series Indiana Jones and the Spear of Destiny, which moves forward to depict Jones and his father searching for the Holy Lance in Ireland in 1945.[76] Spielberg intended to have Connery cameo as Henry in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), but Connery turned it down as he had retired.[77]

Petra's use for the movie's climactic scenes greatly contributed to its popularity as an international tourist destination. Before the film's release, only a few thousand visitors per year made the trip; since then it has grown to almost a million annually.[78] Shops and hotels near the site play up the connection, and it is mentioned prominently in itineraries of locations used in the film series.[79] Jordan's tourism board mentions the connection on its website.[80] In 2012, the satirical news site The Pan-Arabia Enquirer ran a mock story claiming that the board had officially renamed Petra "That Place from Indiana Jones" to reflect how the world more commonly refers to it.[81]

| Award | Category | Recipient/Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Original Score | John Williams | Nominated |

| Best Sound | Ben Burtt, Gary Summers, Shawn Murphy, Tony Dawe | Nominated | |

| Best Sound Editing | Richard Hymns, Ben Burtt | Won | |

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Sean Connery | Nominated |

| Best Sound | Richard Hymns, Tony Dawe, Ben Burtt, Gary Summers, Shawn Murphy | Nominated | |

| Best Special Visual Effects | George Gibbs, Michael J. McAlister, Mark Sullivan, John Ellis | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Supporting Actor | Sean Connery | Nominated |

| Saturn Awards | Best Fantasy Film | Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade | Nominated |

| Best Actor | Harrison Ford | Nominated | |

| Best Writing | Jeffrey Boam | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Anthony Powell, Joanna Johnston | Nominated |

See also

[edit]- List of films shot in Almería

- Otto Rahn, German scholar and Holy Grail researcher.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 29, 2019. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Hat Trick". TheRaider.net. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Indiana Jones: Making the Trilogy (DVD). Paramount Pictures. 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Rinzler, Bouzereau, "The Monkey King: July 1984 to May 1988", p. 184–203.

- ^ a b Richard Corliss; Elaine Dutka; Denise Worrell; Jane Walker (May 29, 1989). "What's Old Is Gold: A Triumph for Indy". Time. Archived from the original on May 24, 2010. Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f McBride, "An Awfully Big Adventure", p. 379–413

- ^ a b "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: An Oral History". Empire. May 8, 2008. Archived from the original on November 19, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ "15 Things You (Probably) Didn't Know About Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade". Shortlist.com. December 30, 2015. Archived from the original on May 9, 2019. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c Marcus Hearn (2005). The Cinema of George Lucas. New York City: Harry N. Abrams Inc. pp. 159–165. ISBN 0-8109-4968-7.

- ^ a b "Casting the Crusaders". TheRaider.net. Archived from the original on January 21, 2009. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Rinzler, Bouzereau, "The Professionals: May 1988 to May 1989", p. 204–229.

- ^ Knolle, Sharon (May 24, 2014). "25 Things You (Probably) Didn't Know About 'Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade'". Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ a b c Susan Royal (December 1989). "Always: An Interview with Steven Spielberg". Premiere. pp. 45–56.

- ^ Rinzler, J.W.; Bouzereau, Laurent (May 20, 2008). The Complete Making of Indiana Jones, Chapter 1: "The Name is Indiana: 1968 to February 1980", p. 36. New York City, United States of America: Penguin Random House. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-345-50129-5. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ Nancy Griffin (June 1988). "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Premiere.

- ^ Vespe, Eric. "FORTUNE AND GLORY: Writers of Doom! Quint interviews Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz!". Ain't Cool News. Archived from the original on February 11, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ McBride, p.318

- ^ David Hughes (November 2005). "The Long Strange Journey of Indiana Jones IV". Empire. p. 131.

- ^ a b c d "Crusade: Viewing Guide". Empire. October 2006. p. 101.

- ^ "Last Crusade Opening Salvo". Empire. October 2006. pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Filming Family Bonds". TheRaider.net. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ^ Boam, Jeffrey. "Indy III" (PDF). The Raider. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ Koski, Genevieve (May 16, 2008). "Raiders of the Lost Ark". The Onion AV Club. Archived from the original on March 26, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Mike. "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: Learning from Stoppard". Creative Screenwriting Magazine. Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ "Indiana Jones House - "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade" - Antonito, CO - Movie Locations on Waymarking.com". waymarking.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ Hatay Heavy Tank (Fictional Tank)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "A Quest's Completion". TheRaider.net. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ^ "Subject: Wes Ford Takahashi". Animators' Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade | Industrial Light & Magic

- ^ (2003). The Sound of Indiana Jones (DVD). Paramount Pictures.

- ^ Caryn James (July 9, 1989). "It's a New Age For Father–Son Relationships". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ Aljean Harmetz (January 18, 1989). "Makers of 'Jones' Sequel Offer Teasers and Tidbits". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^ Rob MacGregor (September 1989). Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-36161-5. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

- ^ Staff (June 11, 1989). "Paperback Best Sellers: June 11, 1989". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Apotheosis". TheRaider.net. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ^ Aljean Harmetz (June 14, 1989). "Movie Merchandise: The Rush Is On". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ Edward Douglas (February 17, 2008). "Hasbro Previews G.I. Joe, Hulk, Iron Man, Indy & Clone Wars". Superhero Hype!. Archived from the original on February 18, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade Daily Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ a b McBride, Joseph (June 1, 1989). "Par's 'Last' Sets Another First". Daily Variety. p. 1.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 13, 2010. Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- ^ a b "1989 Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- ^ "Stone-age comedy rocks the box office". The Courier-News. May 31, 1994. p. 12. Archived from the original on September 16, 2023. Retrieved September 16, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hjack thriller at top". Iowa City Press-Citizen. July 29, 1997. p. 18. Archived from the original on September 7, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Richard Gold (June 7, 1989). "Is 'Last Crusade' truly Indy's last hurrah?". Variety. p. 1.

- ^ Joseph McBride (July 5, 1989). "'Batman' Tops $100-Million". Variety. p. 8.

- ^ "More British b.o. records fall in 'Indiana's' wake; 'Licence' best Bond opener". Variety. July 12, 1989. p. 20.

- ^ Groves, Don (July 12, 1989). "Summer of U.K. discontent is past; B.O. rebounds big". Variety. p. 11.

- ^ "Top Films". The Times. Screen International. August 18, 1989. p. 16.

- ^ "1989 Worldwide Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 2, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- ^ "Indiana Jones". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ^ "Indiana Jones 'raids DVD record'". BBC News Online. October 31, 2003. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ "Indiana Jones: How to enjoy the film as an adult". BBC News Magazine, Washington. October 4, 2012. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ "Indiana Jones Box Set 4K UHD Blu-Ray Preorders Down to $79.99". IGN. March 16, 2021. Archived from the original on March 19, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Cinemascore :: Movie Title Search". December 20, 2018. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Boyar, Jay (May 28, 1989). "'CRUSADE' FITS NEATLY INTO INDY TRILOGY". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ Vincent Canby (June 18, 1989). "Spielberg's Elixir Shows Signs Of Mature Magic". The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Joseph McBride (May 24, 1989). "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Variety. Archived from the original on July 21, 2009. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ^ Roger Ebert (May 24, 1989). "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ Jonathan Rosenbaum. "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^ Hal Hinson (May 24, 1989). "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Desson Thomson (May 26, 1989). "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ "The 62nd Academy Awards (1990) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Tom O'Neil (May 8, 2008). "Will 'Indiana Jones,' Steven Spielberg and Harrison Ford come swashbuckling back into the awards fight?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ "Film Nominations 1989". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ "1990 Hugo Awards". Thehugoawards.org. July 26, 2007. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ "Eleventh Annual Youth in Film Awards 1988–1989". Youngartistawards.org. Archived from the original on April 9, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ "John Williams" (PDF). The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. February 5, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2006.

- ^ Ed Dolista (February 20, 2023). "INDYCAST: EPISODE 330". IndyCast (Podcast). IndyCast. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ William McCay (1990). Young Indiana Jones and the Plantation Treasure. Random House. ISBN 0-679-80579-6.

- ^ Les Martin (1993). Young Indiana Jones and the Titanic Adventure. Random House. ISBN 0-679-84925-4.

- ^ Wolfgang Hohlbein (1991). Indiana Jones und das Verschwundene Volk. Goldmann Verlag. ISBN 3-442-41028-2.

- ^ Elaine Lee (w), Dan Spiegle (p). Indiana Jones and the Spear of Destiny, no. 4 (April to July 1995). Dark Horse Comics.

- ^ Lucasfilm (June 7, 2007). "The Indiana Jones Cast Expands". IndianaJones.com. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Comer, Douglas (2011). Tourism and Archaeological Heritage Management at Petra: Driver to Development Or Destruction?. Springer. pp. 5–6. ISBN 9781461414803. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ Bulger, Adam (May 21, 2008). "Indiana Jones' Favorite Destinations". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ "petra". Jordan Tourism Board. 2010. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ "Petra to be renamed 'That Place From Indiana Jones'". The Pan-Arabia Enquirer. May 18, 2012. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Rinzler, J.W.; Laurent Bouzereau (2008). The Complete Making of Indiana Jones. Random House. ISBN 978-0-09-192661-8. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- Joseph McBride (1997). Steven Spielberg: A Biography. New York City: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-19177-0.

- Douglas Brode (1995). The Films of Steven Spielberg. Citadel. ISBN 0-8065-1540-6.

- "Bibliography". TheRaider.net.

External links

[edit]- 1989 films

- Indiana Jones films

- 1980s action adventure films

- Alternate Nazi Germany films

- American action adventure films

- American sequel films

- Arthurian films

- Cultural depictions of Adolf Hitler

- Films about father–son relationships

- Films about secret societies

- Films directed by Steven Spielberg

- Films scored by John Williams

- Films set in 1912

- Films set in 1938

- Films set in Austria

- Films set in Berlin

- Films set in New York (state)

- Films set in Portugal

- Films set in Turkey

- Films set in Utah

- Films set in Venice

- Films shot at EMI-Elstree Studios

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Colorado

- Films shot in the United Kingdom

- Films shot in Hertfordshire

- Films shot in Germany

- Films shot in Venice

- Films shot in Jordan

- Films shot in New Mexico

- Films shot in San Francisco

- Films shot in Almería

- Films shot in Texas

- Films shot in Turkey

- Films shot in Utah

- Films that won the Best Sound Editing Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by George Lucas

- Films with screenplays by Jeffrey Boam

- Films about the Holy Grail

- Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation–winning works

- Lucasfilm films

- Films about Nazis

- Paramount Pictures films

- Rail transport films

- Scouting in popular culture

- Films about treasure hunting

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s American films

- Films with screenplays by Menno Meyjes

- Films produced by Robert Watts

- Films set in the 1910s

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films set in the 20th century

- 1989 in American cinema

- English-language action adventure films

- Saturn Award–winning films