Russian filtration camps for Ukrainians

Filtration camps, also referred to as concentration camps,[2][3][4] have been used by Russian forces during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine[5][6][7][8] to process Ukrainian citizens from regions under Russian occupation before transferring them into Russia.[9]

Beatings, torture by electricity and killings have been reported by people interrogated in the filtration camps.[10]

The number of Ukrainian citizens relocated to Russia cannot be independently verified. According to the Ukrainian government, some 1.6 million Ukrainians have been forcibly relocated to Russia, with about 250,000 of these being children.[11] The Russian government denies it is forcibly removing Ukrainians to Russia[7] and calls the deportations "evacuation".[12]

Overview

Ukrainians in Russian-occupied zones are often left unable to flee into Ukrainian-held territory, having to either stay[9] in areas experiencing unliveable conditions or flee to other areas under Russian control or into Russia itself.[13] To enter Russia, many Ukrainians are forced to undergo "filtration", a process during which they are interrogated, and their biometric data is taken. While awaiting "filtration", Ukrainians are settled in so-called "filtration camps", set up ad hoc in various public buildings where the "filtration" takes place. After passing "filtration", Ukrainians are reportedly often forcibly transferred to the Russian Far East.[9]

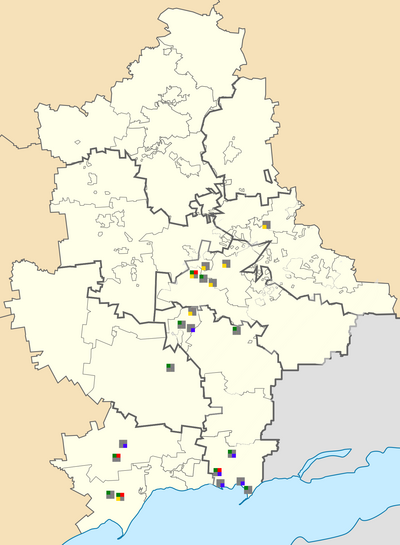

Location of the filtration camps

As of June 2022, most filtration camps were attested to be located in towns and villages across the puppet quasi-state Donetsk People's Republic, with the camps occupying what had been public buildings like schools, cultural centres, sports halls.[9]

In a July 2022 statement to the OSCE, a U.S. diplomat stated that the U.S. had identified at least 18 filtration camp sites set up by Russia both in Ukrainian and Russian territory, with preparations of filtration camps having been undertaken even before the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The filtration camps had been set up in Ukrainian territory that had recently come under Russian occupation by Russian officials working alongside proxy groups, the U.S. diplomat said. The U.S. diplomat said the filtration camps were set up in what had been schools, sport centres, and cultural institutions.[11] An article published by the Polish Spokesman for the Minister Coordinator of Special Services found and published the location of six such camps “where there are Russian torture chambers used against Ukrainians.” [14]

Intake and detention

Fleeing Ukrainians have been transferred into filtration camps unknowingly, being falsely told that they are being taken to Ukrainian-held territory. After arriving in filtration camps, detainees are told they are not allowed to leave the town in which the filtration camp is located as they await "filtration". Detention in filtration camps have been reported to last anywhere from a couple of days to many weeks.[9]

Living conditions

Living conditions in the camps are often squalid. The camps are poorly organised. Those detained in the camps have said they had to sleep on the floors or on cardboard, and that meal rations were scant or altogether absent.[9]

"Filtration" and interrogation

During filtration, detainees are photographed, fingerprinted, interrogated, and the contents of their phones are examined. Detainees are questioned about whether they know anyone serving in the Ukrainian army. Men and in some instances women are strip-searched to be examined for Ukrainian nationalist tattoos.[9][15][16][17] Detainees have reported being asked about their political views and any ties to the Azov Regiment.[18][19][20]

"Filtration" usually ends in one of two ways: either the detainee is given a document certifying that they have passed filtration, or they are detained for further interrogation. Even after passing "filtration", some men are interrogated again during their passage from the filtration camp across areas under Russian control.[9]

Violence, torture, and killings

Beatings, torture with electricity, and killings have been reported by people interrogated in the filtration camps.[10]

In May 2022, videos with Ukrainian civilians apologizing to Russian soldiers, with some of them saying that they had undergone a "denazification course", have appeared on social media. In an interview to Current Time TV, human rights activist Pavel Lisyansky said that the "courses" are often accompanied by physical violence, moral pressure and humiliation, and compared them to the "re-education" of Uyghurs by the Chinese government, which likely inspired these filtration camps and methods. Lisyansky also said that he knows three or four cases of Ukrainian civilians getting killed and their documents destroyed after they had a conflict with their "curator".[21][22][23]

In November 2022, the Head of the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine, Matilda Bogner, reported on the "admission procedures" in the penal colony near Olenivka, which often involved beatings, threats, dog attacks, mock executions, forced nudity, electric and positional torture. The UN agency also reported receiving information about nine deaths in Olenivka in April 2022.[24]

Release and forced deportations

People that have passed through the filtration camps have said that they had been sent to various cities across Russia after their release from the filtration camps, with many having been sent to the Russian Far East.[11]

Ukrainian intelligence has said that Ukrainian citizens released from filtration camps are offered employment in economically depressed regions of Russia by Russian employment centres.[25]

Mikhail Mizintsev, chief of Russia's National Defense Management Center, said on 8 May 2022 that 1,185,791 people have been moved to Russia.[26]

Escape from filtration and forced deportation

Ukrainians that have fled into Georgia have avoided forced deportations into Russian cities that are reportedly common after passing "filtration". Some Ukrainians that were detained in filtration camps have said that informing filtration camp officials that they have concrete plans go live to a specific Russian city enabled them to be released and told to find their own way there, thus enabling them to escape into Georgia and avoid forced transfers.[9]

Some people reported that they needed to slip out of filtration camps in Novoazovsk or post-filtering from Taganrog or Rostov-on-Don to escape through neighboring countries like Georgia, rather than be forcibly sent to distant parts of Russia.[9]

History

On 15 March 2022, The Guardian reported that witnesses have said that Russian troops have ordered women and children out of a bomb shelter in Mariupol. One witness said they were forcibly bussed with two or three hundred others to Novoazovsk, where they had to wait for hours inside the buses until they were ordered to go through a group of tents to what was called a filtration camp. Satellite imagery showed a group of tents in Bezimenne, near Novoazovsk. Representatives of Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic said they had set up a "tent city of 30 tents" with a capacity for 450 people.[6]

Russian government newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta said 5,000 Ukrainians had been processed in the Bezimenne camp and that they had run checks to prevent "Ukrainian nationalists from infiltrating Russia disguised as refugees so they could avoid punishment." One witness said she was extensively questioned by men who said they were from the FSB. She was questioned about her background and described the questioning as "very degrading". The group was then taken to Rostov.[6]

Reactions

Ukraine

Ukrainian officials have compared the filtration camps to filtration camps in Chechnya.[7]

Russia

The Russian Embassy in the United States has said the filtration camps are "checkpoints for civilians leaving the zone of active hostilities".[27]

United States

United States ambassador to the UN Linda Thomas-Greenfield said "I do not need to spell out what these so-called 'filtration camps' are reminiscent of. It's chilling and we cannot look away".[8] She cited reports that FSB agents confiscated passports, IDs and mobile phones, as well as reports of Ukrainian families being separated.[8] The US envoy to the OSCE, Michail Carpenter, told the organization's permanent council that according to credible reporting, Ukrainian civilians in the filtration camps were interrogated and those suspected of ties to independent media or the military were beaten or tortured before being transferred to the Donetsk region, "where they are reportedly disappeared or murdered."[28]

Non-governmental organisations

Tanya Lokshina, director of Human Rights Watch for Europe and Asia, said: "Under international human rights law, forced displacement or transfer doesn't necessarily mean people were forced into a vehicle at gunpoint, but rather that they found themselves in a situation that left them no choice."[6] She pointed out that the Geneva Convention prohibits "individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory, are prohibited, regardless of their motive".[6]

See also

- Claims of genocide of Ukrainians in the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Filtration camp system in Chechnya

- Gulag – the prison system of the USSR

- List of concentration and internment camps#Russia and the Soviet Union

- Nazi concentration camps

- Xinjiang internment camps

- Canadian Indian residential school system

- American Indian boarding schools

- Political prisoners in Russia

- Prisons in Russia

- Russian war crimes

- Ukrainians displaced and forcibly resettled to Russia during the Russo-Ukrainian War

References

- ^ "A central hub to capture, analyze, and make widely available evidence of Russia-perpetrated war crimes and other atrocities in Ukraine". hub.conflictobservatory.org. Archived from the original on 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2022-08-26.

- ^ Dean, Kirby (2022-05-19). "Thousands of Mariupol survivors being detained and 'tortured' in Russia-controlled prisons in occupied Ukraine". MSN. Archived from the original on 2022-05-19. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- ^ Toby Luckhurst & Olga Pona (2022-04-25). "'You can't imagine the conditions' - Accounts emerge of Russian detention camps". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2022-05-18. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- ^ "Ukraine calls on UNSC, UN Secretary General to ensure evacuation of wounded from Azovstal". Interfax-Ukraine. 2022-05-12. Archived from the original on 2022-05-19. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- ^ Vlachou, Marita (2022-04-05). "Mariupol Women Report Russians Taking Ukrainians To 'Filtration Camps'". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 2022-05-21. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ a b c d e Sauer, Pjotr (2022-04-04). "Hundreds of Ukrainians forcibly deported to Russia, say Mariupol women". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2022-05-06. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ a b c Peter, Laurence (2022-03-27). "Russia transfers thousands of Mariupol civilians to its territory". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ a b c Mackintosh, Eliza; Ochman, Oleksandra; Mezzofiore, Gianluca; Polglase, Katie; Rebane, Teele; Graham-Yooll, Anastasia. "Russia or die". CNN. Archived from the original on 2022-07-17. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Beard, Nadia (2022-06-12). "Ukrainians who fled to Georgia reveal details of Russia's 'filtration camps'". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 2022-07-18. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- ^ a b "'The Russians said beatings were my re-education'". BBC News. 2022-06-16. Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- ^ a b c Solomon, Erika (2022-07-08). "The U.S. identified 18 Russian 'filtration camps' for Ukrainians, a diplomat says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- ^ "Минобороны отчиталось об эвакуации более 500 тыс. человек в Россию". Archived from the original on 2022-05-06. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- ^ "Russia transfers thousands of Mariupol civilians to its territory". BBC News. 2022-03-27. Archived from the original on 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- ^ "Special services have identified Russian filtration camps - Special Services - Gov.pl website". Special Services. Archived from the original on 2022-07-27. Retrieved 2022-07-27.

- ^ L'esodo forzato. Dagli Urali alla Siberia la mappa dei campi per i deportati ucraini

- ^ Escape from Azovstal: Surviving Mariupol's last stand

- ^ Ukraine war: Teacher spent 65 days in bomb shelter with her baby during defence of Mariupol steelworks

- ^ "Russia's humiliating 'filtration' of civilians fleeing occupied Ukraine: The Russian army has set up so-called filtration camps in the Donbas to screen civilians for political views before they are evacuated. DW spoke to three people who were able to get out of Mariupol". Deutsche Welle. April 28, 2022. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ^ "Wife of "Azov" spoke about life in the bunker of Azovstal (video) — UNIAN". dailybanner.co.uk. May 30, 2022. Retrieved Jul 17, 2022.

- ^ "L'esodo forzato. Dagli Urali alla Siberia la mappa dei campi per i deportati ucraini". www.repubblicaA.it (in Italian). Jun 5, 2022. Archived from the original on June 8, 2022. Retrieved Jul 17, 2022.

- ^ "Война. Восемьдесят девятый день" [War. Eighty-ninth day]. Meduza (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2022-05-23. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- ^ "Что такое 'курсы денацификации' для украинцев, вывезенных в Россию: рассказывает правозащитник Павел Лисянский" [Human rights activists Pavel Lisyansky explains the "denazification courses" for Ukrainians deported to Russia]. Current Time TV (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2022-06-04. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- ^ "«Я прошла курс денацификации. Осознаю свою вину» — жительницу Херсона заставили извиняться на камеру перед военными из России" ["I have undergone a denazification course. I admit my guilt"—citizen of Kherson forced to apologize on camera to Russian troops]. The Insider (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2022-06-04. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- ^ "Ukraine / Russia: Prisoners of war". OHCHR. 15 November 2022. Retrieved 2022-11-25.

- ^ "Ukrainians, Who Were Deported to Russia, Are Offered Employment in Sakhalin". gur.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 2022-05-28. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- ^ "Over 19,800 people evacuated from Ukraine, DPR, LPR to Russia in past day". TASS. 2022-05-08. Archived from the original on 2022-05-21. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- ^ Miller, Christopher. "One Ukrainian family's perilous journey through Russia's 'filtration camps'". POLITICO. Archived from the original on 2022-07-26. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- ^ "OSCE Envoy Says Evidence Of 'Filtration Camps' Emerging From Areas Of Ukraine Claimed By Russian Forces". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. April 28, 2022. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

Further reading

- 2022 in Ukraine

- 2022 in Russia

- Russia–Ukraine relations

- Military prisoner abuse scandals

- Police brutality in Russia

- War crimes during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Internment camps in Russia

- Internment camps in Ukraine

- Ukrainian refugees

- Deportation

- Euphemisms

- Total institutions

- Russian words and phrases