Association football: Difference between revisions

m Bot: Featured article link for ml:ഫുട്ബോള് |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{dablink|"Soccer" redirects here. For other uses, see [[Soccer (disambiguation)]]. "Fußball" also redirects here; for the table game see [[Table football]].}} |

|||

{{pp-semi-protected|small=yes}} |

{{pp-semi-protected|small=yes}} |

||

{{wiktionary}}{{about|various sports known as "football"|information about the balls used in these sports|football (ball)}} |

|||

[[Image:football iu 1996.jpg|thumb|250px|right| A player (wearing the red [[kit (football)|kit]]) has penetrated the defence (in the white kit) and is taking a shot at goal. The goalkeeper will attempt to stop the ball from crossing the goal line.]] |

|||

[[Image:Football4.png|right|thumb|225px|Some of the many different codes of football.]] |

|||

'''Association football''', commonly known as '''football''' or '''soccer''', is a [[team sport]] played between two teams of eleven players, and is the most popular sport in the world.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761572379/Soccer.html |title=Soccer |publisher=MSN |encyclopedia=Encarta |accessdate=2007-10-07}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Guttman |first=Allen |editor=Eric Dunning, Joseph A. Maguire, Robert E. Pearton |title=The Sports Process: A Comparative and Developmental Approach |origyear=1993 |accessdate=2008-01-26 |publisher=Human Kinetics |location=[[Champaign, Illinois|Champaign]] |isbn=0880116242 |pages=p129 |chapter=The Diffusion of Sports and the Problem of Cultural Imperialism |chapterurl=http://books.google.com/books?id=tQY5wxQDn5gC&pg=PA129&lpg=PA129&dq=world's+most+popular+team+sport&source=web&ots=6ns3wVUEGV&sig=SZPKYSDMJBrO1uV4mPxNbKyAuJY#PPA129,M1 |quote=the game is complex enough not to be invented independently by many preliterate cultures and yet simple enough to become the world's most popular team sport }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Dunning |first=Eric |authorlink=Eric Dunning |title=Sport Matters: Sociological Studies of Sport, Violence and Civilisation |origyear=1999 |accessdate=2008-01-26 |publisher=[[Routledge]] |location=London |isbn=0415064139 |pages=p103 |chapter=The development of soccer as a world game |chapterurl=http://books.google.com/books?id=X3lX_LVBaToC&pg=PA105&lpg=PA105&dq=world's+most+popular+team+sport&source=web&ots=ehee9Lr9o1&sig=nyvDhcrPoR8lXhYKE7k4CZYg_qU#PPA103,M1 |quote=During the twentieth century, soccer emerged as the world's most popular team sport }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Soccer Popularity In U.S. |url=http://www.kxan.com/global/story.asp?s=5019143 |publisher=[[KXAN-TV|KXAN]] |date=[[2006-06-12]] |accessdate=2008-01-26 |quote=Soccer is easily the most popular sport worldwide, so popular that much of Europe practically shuts down during the World Cup. |location=[[Austin, Texas]]}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Frederick O. Mueller, Robert C. Cantu, Steven P. Van Camp |last= |first= |coauthors= |title=Catastrophic Injuries in High School and College Sports |origdate= |origyear=1996 |accessdate=2008-01-26 |publisher=Human Kinetics |location=[[Champaign, Illinois|Champaign]] |isbn=0873226747 |pages=p57 |chapter=Team Sports |chapterurl=http://books.google.com/books?id=XG6AIHLtyaUC&pg=PA57&lpg=PA57&dq=soccer+most+popular+team+sport&source=web&ots=QzydYB5Am0&sig=w_ouIgmegjytYFfWy7k92guTNfU#PPA57,M1 |quote=Soccer is the most popular sport in the world, and it's popularity is growing in the United States. It has been estimated that there were 22 million soccer players in the world in the early 1980s, and that number is increasing. In the United States soccer is now a major sport at both the high school and college levels }}</ref> It is a [[ball]] game played on a rectangular [[grass]] or [[artificial turf]] field, with a [[goal (sport)|goal]] at each of the short ends. The object of the game is to score by manoeuvring <!-- this is the correct British English spelling please do NOT change it to maneuvering --> the ball into the opposing goal. In general play, the [[goalkeeper (football)|goalkeeper]] is the only player allowed to use their hands or arms to propel the ball; the rest of the team usually use their feet to [[kick]] the ball into position, occasionally using their [[torso]] or [[head]] to intercept a ball in midair. The team that scores the most goals by the end of the match wins. If the score is tied at the end of the game, either a [[tie (draw)|draw]] is declared or the game goes into extra time and/or a [[penalty shootout (football)|penalty shootout]], depending on the format of the competition. |

|||

'''Football''' is the name given to a number of different [[team sport]]s. |

|||

The most popular of these sports world-wide is [[association football]], also known as soccer. The [[English language]] word [[football (word)|"football"]] is also applied to [[gridiron football]] (which includes [[American football]] and [[Canadian football]]), [[Australian rules football]], [[Gaelic football]], [[rugby football]] ([[rugby league]] and [[rugby union]]), and related games. Each of these ''codes'' (specific sets of rules, or the games defined by them) is referred to as "football". |

|||

These games involve: |

|||

The modern game was codified in [[England]] following the formation of [[The Football Association]], whose 1863 [[Laws of the Game]] created the foundations for the way the sport is played today. Football is governed internationally by the [[FIFA|Fédération Internationale de Football Association]] (International Federation of Association Football), commonly known by the [[acronym]] FIFA. The most prestigious international football competition is the [[FIFA World Cup|World Cup]], held every four years. This event, the most widely viewed in the world, boasts an audience twice that of the [[Summer Olympics]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://web.archive.org/web/20061230124633/http://www.fifa.com/en/marketing/newmedia/index/0,3509,10,00.html |title=2002 FIFA World Cup TV Coverage |publisher=FIFA official website |date=2006-12-05 |accessdate=2008-01-06}} (webarchive)</ref> |

|||

*a large [[sphere|spherical]] or [[prolate spheroid]] ball, which is itself called a ''[[Football (ball)|football]].'' |

|||

* a ''[[team]]'' ''[[score (game)|scoring]]'' ''[[goal (sport)|goal]]s'' and/or ''[[Score (game)|point]]s'', by moving the ball to an opposing team's end of the field and either into a goal area, or over a line. |

|||

* the goal and/or line being ''[[Defender (football)|defended]]'' by the opposing team. |

|||

* players being required to move the ball—depending on the code—by ''[[Kick (football)|kick]]ing'', carrying and/or passing the ball by hand. |

|||

* goals and/or points resulting from players putting the ball between two ''[[goalposts]]''. |

|||

In most codes, there are ''[[offside]]'' rules restricting the movement of players and players scoring a goal must put the ball either under or over a ''[[crossbar]]'' between the goalposts. Other features common to several codes include points being mostly scored by players carrying the ball across the goal line and players receiving a ''[[free kick]]'' after they ''take a [[Mark#Catching a ball|mark]]/make a [[fair catch]]''. |

|||

Peoples from around the world have played games which involved kicking and/or carrying a ball, since [[ancient times]]. However, most of the modern codes of football have their origins in [[England]]. |

|||

== Nature of the game == |

|||

[[Image:Soccer goalkeeper.jpg|thumb|250px|A goalkeeper dives to stop the ball from entering his goal.]] |

|||

Football is played in accordance with a set of rules known as the [[Laws of the Game]]. The game is played using a single round ball, known as the ''[[football (ball)|football]]''. Two teams of eleven players each compete to get the ball into the other team's goal (between the posts and under the bar), thereby scoring a goal. The team that has scored more goals at the end of the game is the winner; if both teams have scored an equal number of goals then the game is a draw. |

|||

==Etymology== |

|||

The primary rule is that players (other than [[Goalkeeper (football)|goalkeepers]]) may not deliberately handle the ball with their hands or arms during play (though they do use their hands during a [[throw-in]] restart). Although players usually use their feet to move the ball around, they may use any part of their bodies other than their hands or arms.<ref name="fouls">{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws12_02.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 12) |accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> |

|||

{{main|Football (word)}} |

|||

While it is widely believed that the word "football" (or "foot ball") originated in reference to the action of a foot kicking a ball, there is a rival explanation, which has it that football originally referred to a variety of games in [[medieval Europe]], which were played ''on foot''.<ref>Sports historian Bill Murray, quoted by [http://www.abc.net.au/rn/talks/8.30/sportsf/stories/s566884.htm ''The Sports Factor'', "Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Sport"] (Radio National, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, May 31, 2002) and [http://www.spiegel.de/international/0,1518,420024,00.html Michael Scott Moore, "Naming the Beautiful Game: It's Called Soccer"] (''Der Spiegel'', June 7, 2006). See also: [http://www.icons.org.uk/theicons/collection/fa-cup/biography/history-of-football ICONS Online (no date) "History of Football"] and; [http://www.footballresearch.com/articles/frpage.cfm?topic=a-to1633 Professional Football Researchers Association, (no date) "A Freendly Kinde of Fight: The Origins of Football to 1633"]. Access date for all references: February 11, 2007.</ref> These games were usually played by [[peasant]]s, as opposed to the [[Equestrianism|horse-riding]] sports often played by [[aristocrat]]s. While there is no conclusive evidence for this explanation, the word football has always implied a variety of games played on foot, not just those that involved kicking a ball. In some cases, the word football has even been applied to games which have specifically outlawed kicking the ball. |

|||

In typical game play, players attempt to create goal scoring opportunities through individual control of the ball, such as by [[dribbling]], passing the ball to a teammate, and by taking shots at the goal, which is guarded by the opposing goalkeeper. Opposing players may try to regain control of the ball by intercepting a pass or through tackling the opponent in possession of the ball; however, physical contact between opponents is restricted. Football is generally a free-flowing game, with play stopping only when the ball has left the field of play or when play is stopped by the [[Referee (football)|referee]]. After a stoppage, play recommences with a specified restart.<ref name="restart">{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws8_01.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 8) |accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Shuihu5.PNG|thumb|150px|left|A 15th century [[woodcut printing|woodcut]] depiction of cuju, from a [[Ming Dynasty]] edition of the ''[[Water Margin]]''.]] [[Image:Kemari Matsuri at Tanzan Shrine 2.jpg|thumb|150px|left|A revived version of ''Kemari'' being played at the [[Tanzan Shrine]].]] |

|||

At a professional level, most matches produce only a few goals. For example, the [[FA Premier League 2005-06|2005–06 season]] of the [[England|English]] [[Premier League]] produced an average of 2.48 goals per match.<ref>{{cite web |title=England Premiership (2005/2006) |work=Sportpress.com |url=http://www.sportpress.com/stats/en/738_england_premiership_2005_2006/11_league_summary.html |accessdate=2007-06-05}}</ref> The Laws of the Game do not specify any player positions other than goalkeeper,<ref name=LAW301>{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws3_01.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 3–Number of Players) |accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> but a number of [[association football positions|specialised roles]] have evolved. Broadly, these include three main categories: [[striker]]s, or forwards, whose main task is to score goals; [[Defender (football)|defenders]], who specialise in preventing their opponents from scoring; and [[midfielder]]s, who dispossess the opposition and keep possession of the ball in order to pass it to the forwards. Players in these positions are referred to as outfield players, in order to discern them from the single goalkeeper. These positions are further subdivided according to the area of the field in which the player spends most time. For example, there are central defenders, and left and right midfielders. The ten outfield players may be arranged in any combination. The number of players in each position determines the style of the team's play; more forwards and fewer defenders creates a more aggressive and offensive-minded game, while the reverse creates a slower, more defensive style of play. While players typically spend most of the game in a specific position, there are few restrictions on player movement, and players can switch positions at any time.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/rules_and_equipment/4196830.stm |title=Positions guide, Who is in a team? |publisher=BBC |accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> The layout of a team's players is known as a [[Formation (football)|''formation'']]. Defining the team's formation and tactics is usually the prerogative of the team's [[manager (football)|manager]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/football/rules_and_equipment/4197420.stm |title=Formations |publisher=[[BBC Sport]] |accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

===Early history=== |

|||

====Ancient games==== |

|||

Documented evidence of what is possibly the oldest activity resembling football can be found in a [[China|Chinese]] [[military]] manual written during the [[Warring States Period]] in about the [[476 BC]]-[[221 BC]]. It describes a practice known as ''[[cuju]]'' (蹴鞠, literally "kick ball"), which originally involved kicking a leather ball through a hole in a piece of [[silk]] cloth strung between two 30-foot poles. During the [[Han Dynasty]] (206 BC–220 AD), cuju games were standardized and rules were established. Variations of this game later spread to [[Japan]] and [[Korea]], known as ''[[kemari]]'' and ''chuk-guk'' respectively. By the Chinese [[Tang Dynasty]] (618-907), the feather-stuffed ball was replaced by an air-filled ball and cuju games had become professionalized, with many players making a living playing cuju. Also, two different types of goal posts emerged: One was made by setting up posts with a net between them and the other consisted of just one goal post in the middle of the field. [[FIFA]], the governing body of [[association football]] (soccer), has acknowledged that China was the birthplace of its game.<ref>[http://www.fifa.com/womenolympic/destination/hostcountry/index.html FIFA.com - Host Country: China]</ref> |

|||

The Japanese version of ''cuju'' is ''[[kemari]]'' (蹴鞠), and was adopted during the [[Asuka period]] from the Chinese. This is known to have been played within the Japanese imperial court in [[Kyoto]] from about 600 AD. In ''kemari'' several people stand in a circle and kick a ball to each other, trying not to let the ball drop to the ground (much like [[keepie uppie]]). The game appears to have died out sometime before the mid-19th century. It was revived in 1903 and is now played at a number of festivals. |

|||

== History and development == |

|||

{{seealso|Football|History of association football}} |

|||

[[Image:Football world popularity.png|thumb|250px|Map showing the popularity of football around the world. Countries where football is the most popular sport are coloured green, while countries where it is not are coloured red. The various shades of green and red indicate the number of players per 1,000 inhabitants.]] |

|||

The [[Ancient Greece|Ancient Greek]]s and [[Ancient Rome|Romans]] are known to have played many ball games some of which involved the use of the feet. The Roman writer [[Cicero]] describes the case of a man who was killed whilst having a shave when a ball was kicked into a barber's shop. The Roman game ''[[harpastum]]'' is believed to have been adapted from a team game known as "επισκυρος" (''episkyros'') or ''pheninda'' that is mentioned by Greek playwright, [[Antiphanes]] (388-311BC) and later referred to by [[Clement of Alexandria]]. These games appears to have resembled [[rugby football|rugby]]. |

|||

Games revolving around the kicking of a ball have been played in many countries throughout history. According to [[FIFA]], the "very earliest form of the game for which there is scientific evidence was an exercise of precisely this skilful technique dating back to the 2nd and 3rd centuries BC in [[China]] (the game of [[cuju]])."<ref>{{cite web | title = History of Football | work = FIFA| url = http://www.fifa.com/classicfootball/history/game/historygame1.html | accessdate =2006-11-20}}</ref> In addition, the [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] game [[harpastum]] may be a distant ancestor of football. Various forms of [[medieval football|football were played in medieval Europe]], though rules varied greatly by both period and location. |

|||

[[Image:Marn grook illustration 1857.jpg|thumb|right|185px|An illustration from the 1850s of [[Indigenous Australian|Australian Aboriginal]] [[hunter gatherer]]s. Children in the background are playing a football game, possibly ''[[Marn Grook]]''.<ref>From William Blandowski's Australien in 142 Photographischen Abbildungen, 1857, (Haddon Library, Faculty of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge)</ref>]] |

|||

<!--Text commented out due to lack of verifiable reference, see talk page--><!--Whilst football has continued to be played in various forms throughout the [[United Kingdom]], the English [[Independent school (UK)|public schools]] (fee-paying schools) are widely credited with certain key achievements in the creation of modern football (association football and the [[rugby football]] games—[[rugby league]] and [[rugby union]] football). During the sixteenth century English public schools generally, and headmaster [[Richard Mulcaster]] in particular, were instrumental in taking football away from its violent "[[Mob rule|mob]]" form and turning it into an organised team sport that was beneficial to schoolboys. Thereafter, the game became institutionalised, regulated, and part of a larger, more central tradition. Many early descriptions of football and references to it (e.g., in poetry) were recorded by people who had studied at these schools, showing they were familiar with the game. Finally, in the 19th century, teachers and former students were the first to write down formal rules of early modern football to enable matches to be played between schools.--> |

|||

There are a number of references to [[tradition]]al, [[ancient]], and/or [[prehistoric]] ball games, played by [[indigenous peoples]] in many different parts of the world. For example, in 1586, men from a ship commanded by an English explorer named [[John Davis (English explorer)|John Davis]], went ashore to play a form of football with [[Inuit]] (Eskimo) people in [[Greenland]].<ref>Richard Hakluyt, [http://etext.library.adelaide.edu.au/h/hakluyt/northwest/chapter8.html Voyages in Search of The North-West Passage], ''[[University of Adelaide]]'', December 29, 2003</ref> There are later accounts of an Inuit game played on ice, called ''[[Aqsaqtuk]]''. Each match began with two teams facing each other in parallel lines, before attempting to kick the ball through each other team's line and then at a goal. In 1610, [[William Strachey]] of the [[Jamestown settlement]], [[Virginia]] recorded a game played by [[Native Americans in the United States|Native Americans]], called ''[[Pahsaheman]]''. In [[Victoria, Australia]], [[indigenous Australians|indigenous people]] played a game called ''[[Marn Grook]]'' ("ball game"). An 1878 book by [[Robert Brough-Smyth]], ''The Aborigines of Victoria'', quotes a man called Richard Thomas as saying, in about 1841, that he had witnessed Aboriginal people playing the game: "Mr Thomas describes how the foremost player will drop kick a ball made from the skin of a [[possum]] and how other players leap into the air in order to catch it." It is widely believed that ''Marn Grook'' had an influence on the development of [[Australian rules football]] (see below). |

|||

The modern rules of football are based on the mid-19th century efforts to standardise the widely varying forms of football played at the public schools of England. |

|||

[[Mesoamerican ballgame|Games played in Central America]] with rubber balls by [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|indigenous peoples]] are also well-documented as existing since before this time, but these had more similarities to [[basketball]] or [[volleyball]], and since their influence on modern football games is minimal, most do not class them as football. |

|||

The [[Cambridge Rules]], first drawn up at [[Cambridge University]] in 1848, were particularly influential in the development of subsequent codes, including Association football. The Cambridge Rules were written at [[Trinity College, Cambridge]], at a meeting attended by representatives from Eton, [[Harrow School|Harrow]], [[Rugby School|Rugby]], [[Winchester College|Winchester]] and [[Shrewsbury School|Shrewsbury]] schools. They were not universally adopted. During the 1850s, many clubs unconnected to schools or universities were formed throughout the English-speaking world, to play various forms of football. Some came up with their own distinct codes of rules, most notably the [[Sheffield F.C.|Sheffield Football Club]], formed by former public school pupils in 1857,<ref>{{cite book |last=Harvey |first=Adrian |title=Football, the first hundred years |publisher=Routledge |pages=pp.126 |date=2005 |location=London |isbn=0415350182}}</ref> which led to formation of a [[Sheffield & Hallamshire Football Association|Sheffield FA]] in 1867. In 1862, [[J. C. Thring|John Charles Thring]] of [[Uppingham School]] also devised an influential set of rules.<ref>{{cite news |first=David |last=Winner |date=2005-03-28 | title = The hands-off approach to a man's game |work=The Times |url=http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,27-1544006,00.html |accessdate=2007-10-07}}</ref> |

|||

These games and others may well go far back into antiquity and may have influenced later football games. However, the main sources of modern football codes appear to lie in western Europe, especially [[England]]. |

|||

These ongoing efforts contributed to the formation of [[The Football Association]] (The FA) in 1863, which first met on the morning of [[26 October]] [[1863]] at the Freemason's Tavern in [[Great Queen Street]], [[London]].<ref name="FAhistory">{{cite web |title=History of the FA |work=Football Association website |url=http://www.thefa.com/TheFA/TheOrganisation/Postings/2004/03/HISTORY_OF_THE_FA.htm |accessdate=2007-10-09}}</ref> The only school to be represented on this occasion was [[Charterhouse School|Charterhouse]]. The Freemason's Tavern was the setting for five more meetings between October and December, which eventually produced the first comprehensive set of rules. At the final meeting, the first FA treasurer, the representative from [[Blackheath Rugby Club|Blackheath]], withdrew his club from the FA over the removal of two draft rules at the previous meeting, the first which allowed for the running with the ball in hand and the second, obstructing such a run by hacking (kicking an opponent in the shins), tripping and holding. Other [[History of rugby union|English rugby football clubs followed this lead]] and did not join the FA, or subsequently left the FA and instead in 1871 formed the [[Rugby Football Union]]. The eleven remaining clubs, under the charge of [[Ebenezer Cobb Morley]], went on to ratify the original thirteen laws of the game.<ref name="FAhistory"/> These rules included handling of the ball by "marks" and the lack of a crossbar, rules which made it remarkably similar to [[Australian rules football|Victorian rules football]] being developed at that time in Australia. The Sheffield FA played by its own rules until the 1870s with the FA absorbing some of its rules until there was little difference between the games. |

|||

====Medieval and early modern Europe==== |

|||

The laws of the game are currently determined by the [[International Football Association Board]] (IFAB). The Board was formed in 1886<ref>{{cite web |title=The International FA Board |publisher=FIFA |url=http://web.archive.org/web/20070422035010/http://access.fifa.com/en/history/history/0,3504,3,00.html |accessdate=2007-09-02 }} (webarchive)</ref> after a meeting in [[Manchester]] of The Football Association, the [[Scottish Football Association]], the [[Football Association of Wales]], and the [[Irish Football Association]]. The world's oldest football competition is the [[FA Cup]], which was founded by [[C. W. Alcock]] and has been contested by English teams since 1872. The first official international football match took place in 1872 between Scotland and England in [[Glasgow]], again at the instigation of C. W. Alcock. England is home to the world's first [[The Football League|football league]], which was founded in 1888 by [[Aston Villa F.C.|Aston Villa]] director [[William McGregor]].<ref>{{cite web | title = The History Of The Football League | work = Football League website | url = http://www.football-league.premiumtv.co.uk/page/History/0,,10794,00.html | accessdate=2007-10-07}}</ref> The original format contained 12 clubs from the Midlands and the North of England. The Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), the international football body, was formed in [[Paris]] in 1904 and declared that they would adhere to Laws of the Game of the Football Association.<ref name=Wherebegan/> The growing popularity of the international game led to the admittance of FIFA representatives to the [[International Football Association Board]] in 1913. The board currently consists of four representatives from FIFA and one representative from each of the four British associations. |

|||

{{see|Medieval football}} |

|||

<!-- IMPORTANT NOTE to editors: we have a length problem! That is why there is a Mediæval football article. Please do not add new material to this section unless it is significant -- please put any new material in the Mediæval football article _before_ you add it to this section. Thank you. -->The [[Middle Ages]] saw a huge rise in popularity of annual [[Shrovetide football]] matches throughout Europe, particularly in England. The game played in England at this time may have arrived with the [[Roman Britain|Roman occupation]], but there is little evidence to indicate this. Reports of a game played in [[Brittany]], [[Normandy]], and [[Picardy]], known as ''[[La Soule]]'' or ''Choule'', suggest that some of these football games could have arrived in [[England]] as a result of the [[Norman Conquest]].[[Image:Mobfooty.jpg|thumb|left|225px|An illustration of so-called "[[mob football]]".]] |

|||

These forms of football, sometimes referred to as "[[mob football]]", would be played between neighbouring towns and villages, involving an unlimited number of players on opposing teams, who would clash in a heaving mass of people, struggling to move an item such as an inflated [[pig]]'s [[bladder]], to particular geographical points, such as their opponents' church. Shrovetide games have survived into the modern era in a number of English towns (see below). |

|||

Today, football is played at a professional level all over the world. Millions of people regularly go to football stadiums to follow their favourite teams,<ref>{{cite news |url=http://football.guardian.co.uk/news/theknowledge/0,9204,1059366,00.html |title=Baseball or Football: which sport gets the higher attendance? | author = Ingle, Sean and Barry Glendenning | date = [[2003-10-09]] | publisher=Guardian Unlimited |accessdate=2006-06-05}}</ref> while billions more watch the game on television.<ref>{{cite web | title = TV Data | work = FIFA website | url = http://www.fifa.com/aboutfifa/marketingtv/factsfigures/tvdata.html | accessdate = 2007-09-02 }}</ref> A very large number of people also play football at an amateur level. According to a survey conducted by FIFA published in 2001, over 240 million people from more than 200 countries regularly play football.<ref>{{cite web | title = FIFA Survey: approximately 250 million footballers worldwide | work = FIFA website | url = http://web.archive.org/web/20060915133001/http://access.fifa.com/infoplus/IP-199_01E_big-count.pdf | format = PDF | accessdate = 2006-09-15 }} (webarchive)</ref> Its simple rules and minimal equipment requirements have no doubt aided its spread and growth in popularity. |

|||

The first detailed description of football in England was given by William FitzStephen in about 1174-1183. He described the activities of [[London]] youths during the annual festival of [[Shrove Tuesday]]: |

|||

In many parts of the world football evokes great passions and plays an important role in the life of individual [[Fan (aficionado)|fan]]s, local communities, and even nations; it is therefore often claimed to be the most popular sport in the world. [[ESPN]] has spread the claim that the [[Côte d'Ivoire national football team]] helped secure a truce to the nation's civil war in 2005. By contrast, football is widely considered to be the final proximate cause in the [[Football War]] in June 1969 between [[El Salvador]] and [[Honduras]].<ref>{{cite web | title = |

|||

:''After lunch all the youth of the city go out into the fields to take part in a ball game. The students of each school have their own ball; the workers from each city craft are also carrying their balls. Older citizens, fathers, and wealthy citizens come on horseback to watch their juniors competing, and to relive their own youth vicariously: you can see their inner passions aroused as they watch the action and get caught up in the fun being had by the carefree adolescents''.<ref>Stephen Alsford, [http://www.trytel.com/~tristan/towns/florilegium/introduction/intro01.html#p25 FitzStephen's Description of London], ''Florilegium Urbanum'', April 5, 2006</ref> |

|||

Has football ever started a war? | work = The Guardian | url = http://football.guardian.co.uk/theknowledge/story/0,,2017161,00.html |author = Dart, James and Paolo Bandini | date = [[2007-02-21]] | accessdate = 2007-09-24 }}</ref> The sport also exacerbated tensions at the beginning of the [[Yugoslav wars]] of the 1990s, when a match between [[NK Dinamo Zagreb|Dinamo Zagreb]] and [[Red Star Belgrade]] devolved into rioting in March 1990.<ref>{{cite news | work=[[The Washington Post]] | title= The Soccer Wars | author = Daniel W. Drezner | date = [[2006-06-04]] | page = B01}}</ref> |

|||

Most of the very early references to the game speak simply of "ball play" or "playing at ball". This reinforces the idea that the games played at the time did not necessarily involve a ball being kicked. |

|||

== Laws of the game == |

|||

There are seventeen laws in the official [[Laws of the Game]]. The same Laws are designed to apply to all levels of football, although certain modifications for groups such as juniors, seniors or women are permitted. The laws are often framed in broad terms, which allow flexibility in their application depending on the nature of the game. In addition to the seventeen laws, numerous IFAB decisions and other directives contribute to the regulation of football. The Laws of the Game are published by FIFA, but are maintained by the [[International Football Association Board]], not FIFA itself.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.fifa.com/worldfootball/lawsofthegame.html| title=Laws Of The Game |publisher=FIFA |accessdate=2007-09-02}}</ref> |

|||

In [[1314]], Nicholas de Farndone, [[Lord Mayor of London]] issued a decree banning football in the [[French language|French]] used by the English upper classes at the time. A translation reads: "[f]orasmuch as there is great noise in the city caused by hustling over large foot balls [''rageries de grosses pelotes de pee''] in the fields of the public from which many evils might arise which God forbid: we command and forbid on behalf of the king, on pain of imprisonment, such game to be used in the city in the future." This is the earliest reference to football. |

|||

=== Players, equipment and officials === |

|||

{{seealso|Association football positions|Formation (football)|Kit (Association football)}} |

|||

The earliest mention of a ball game that involves kicking was in [[1321]], in [[Shouldham]], [[Norfolk]]: "[d]uring the game at ball as he kicked the ball, a lay friend of his... ran against him and wounded himself".<ref name=Magoun>Francis Peabody Magoun, 1929, "Football in Medieval England and Middle-English literature” (''The American Historical Review'', v. 35, No. 1).</ref> |

|||

Each team consists of a maximum of eleven players (excluding [[substitute (football)|substitute]]s), one of whom must be the [[goalkeeper (football)|goalkeeper]]. Competition rules may state a minimum number of players required to constitute a team; this is usually seven. Goalkeepers are the only players allowed to play the ball with their hands or arms, provided they do so within the [[Penalty area (football)|penalty area]] in front of their own goal. Though there are a variety of [[association football positions|positions]] in which the outfield (non-goalkeeper) players are strategically placed by a coach, these positions are not defined or required by the Laws.<ref name=LAW301/> |

|||

In [[1363]], King [[Edward III of England]] issued a proclamation banning "...handball, football, or hockey; coursing and cock-fighting, or other such idle games", showing that "football" — whatever its exact form in this case — was being differentiated from games involving other parts of the body, such as handball. |

|||

The basic equipment or ''[[Kit (association football)|kit]]'' players are required to wear includes a shirt, shorts, socks, footwear and adequate [[shin guard]]s. Players are forbidden to wear or use anything that is dangerous to themselves or another player, such as jewellery or watches. The goalkeeper must wear clothing that is easily distinguishable from that worn by the other players and the match officials.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws4_01.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 4–Players' Equipment) |accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> |

|||

King [[Henry IV of England]] also presented one of the earliest documented uses of the English word "football", in [[1409]], when he issued a proclamation forbidding the levying of money for "foteball".<ref name=Magoun/><ref name=Etymology>[http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=football Online Etymology Dictionary (no date), "football"]</ref> |

|||

A number of players may be replaced by substitutes during the course of the game. The maximum number of substitutions permitted in most competitive international and domestic league games is three, though the permitted number may vary in other competitions or in friendly matches. Common reasons for a substitution include injury, tiredness, ineffectiveness, a tactical switch, or [[timewasting]] at the end of a finely poised game. In standard adult matches, a player who has been substituted may not take further part in a match.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws3_02.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 3–Substitution procedure) |accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> |

|||

There is also an account in [[Latin]] from the end of the [[15th century]] of football being played at [[Cawston]], [[Nottinghamshire]]. This is the first description of a "kicking game" and the first description of [[dribbling]]: "[t]he game at which they had met for common recreation is called by some the foot-ball game. It is one in which young men, in country sport, propel a huge ball not by throwing it into the air but by striking it and rolling it along the ground, and that not with their hands but with their feet... kicking in opposite directions" The chronicler gives the earliest reference to a football field, stating that: "[t]he boundaries have been marked and the game had started.<ref name=Magoun/> |

|||

A game is officiated by a [[referee (football)|referee]], who has "full authority to enforce the Laws of the Game in connection with the match to which he has been appointed" (Law 5), and whose decisions are final. The referee is assisted by two [[assistant referee]]s. In many high-level games there is also a [[fourth official]] who assists the referee and may replace another official should the need arise.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws5_01.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 5–The referee) |accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> |

|||

Other firsts in the mediæval and [[early modern Europe|early modern]] eras: |

|||

=== Pitch === |

|||

[[Image:Football pitch metric.svg|510px|thumb|right|Standard pitch measurements ([[:Image:Football pitch imperial.svg|See Imperial version]])]] |

|||

{{main|Football pitch}} |

|||

* "a football", in the sense of a ball rather than a game, was first mentioned in 1486.<ref name=Etymology/> This reference is in Dame [[Juliana Berners]]' ''Book of St Albans''. It states: "a certain rounde instrument to play with ...it is an instrument for the foote and then it is calde in Latyn 'pila pedalis', a fotebal."<ref name=Magoun/> |

|||

As the Laws were formulated in England, and were initially administered solely by the four British football associations within [[IFAB]], the standard dimensions of a football pitch were originally expressed in [[imperial units]]. The Laws now express dimensions with approximate [[SI|metric]] equivalents (followed by traditional units in brackets), though popular use tends to continue to use traditional units in English-speaking countries with a relatively recent history of [[metrification]], such as Britain.<ref>{{cite web | title = Will we ever go completely metric? | work = BBC| url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/3934353.stm | date = [[2004-09-02]] | author = Summers, Chris | accessdate =2007-10-07}}</ref> |

|||

* a pair of football boots was ordered by King [[Henry VIII of England]] in 1526.<ref>[http://arts.guardian.co.uk/news/story/0,,1150460,00.html Vivek Chaudhary, “Who's the fat bloke in the number eight shirt?”] (''[[The Guardian]]'', February 18, 2004.)</ref> |

|||

* women playing a form of football was in 1580, when Sir [[Philip Sidney]] described it in one of his poems: "[a] tyme there is for all, my mother often sayes, When she, with skirts tuckt very hy, with girles at football playes."<ref>Anniina Jokinen, [http://www.luminarium.org/editions/sidneydialogue.htm Sir Philip Sidney. "A Dialogue Between Two Shepherds"] (''Luminarium.org'', July 2006)</ref> |

|||

* the first references to ''goals'' are in the late [[16th century|16th]] and early [[17th century|17th centuries]]. In 1584 and 1602 respectively, [[John Norden]] and [[Richard Carew]] referred to "goals" in [[Cornish hurling]]. Carew described how goals were made: "they pitch two bushes in the ground, some eight or ten foote asunder; and directly against them, ten or twelue [twelve] score off, other twayne in like distance, which they terme their Goales".<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext06/srvcr10.txt |

|||

|title=EBook of The Survey of Cornwall |

|||

|author=Richard Carew |

|||

|publisher=Project Guternberg |

|||

|accessdate=2007-10-03}}</ref> He is also the first to describe goalkeepers and passing of the ball between players. |

|||

* the first direct reference to ''scoring a goal'' is in [[John Day (dramatist)|John Day]]'s play ''[[The Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green]]'' (performed circa 1600; published 1659): "I'll play a gole at [[Camping (game)|camp-ball]]" (an extremely violent variety of football, which was popular in [[East Anglia]]). Similarly in a poem in 1613, [[Michael Drayton]] refers to "when the Ball to throw, And drive it to the Gole, in squadrons forth they goe". |

|||

====Calcio Fiorentino==== |

|||

The length of the pitch for international adult matches is in the range 100–110 m (110–120 yd) and the width is in the range 64–75 m (70–80 yd). Fields for non-international matches may be 91–120 m (100–130 yd) length and 45–91 m (50–101 yd) in width, provided that the pitch does not become square. The longer boundary lines are ''touchlines'' or ''sidelines'', while the shorter boundaries (on which the goals are placed) are ''goal lines''. A rectangular goal is positioned at the middle of each goal line.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws1_01.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 1.1–The field of play) |accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> The inner edges of the vertical goal posts must be 7.3 m (8 yd) apart, and the lower edge of the horizontal crossbar supported by the goal posts must be 2.44 m (8 ft) above the ground. Nets are usually placed behind the goal, but are not required by the Laws.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws1_04.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 1.4–The Field of play) |accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> |

|||

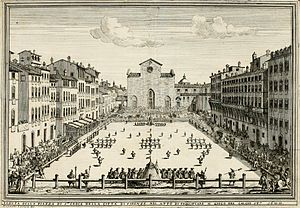

[[Image:Calcio fiorentino 1688.jpg|right|thumb|300px|An illustration of the ''Calcio Fiorentino'' field and starting positions, from a 1688 book by Pietro di Lorenzo Bini.]] |

|||

{{main|Calcio Fiorentino}} |

|||

In the 16th century, the city of [[Florence]] celebrated the period between [[Epiphany (feast)|Epiphany]] and [[Lent]] by playing a game which today is known as "''calcio storico''" ("historic kickball") in the [[Piazza della Novere]] or the [[Piazza Santa Croce]]. The young aristocrats of the city would dress up in fine silk costumes and embroil themselves in a violent form of football. For example, ''calcio'' players could punch, shoulder charge, and kick opponents. Blows below the belt were allowed. The game is said to have originated as a military training exercise. In 1580, Count Giovanni de' Bardi di Vernio wrote ''Discorso sopra 'l giuoco del Calcio Fiorentino''. This is sometimes said to be the earliest code of rules for any football game. The game was not played after January 1739 (until it was revived in May 1930). |

|||

====Official disapproval and attempts to ban football==== |

|||

In front of each goal is an area known as the [[penalty area]]. This area is marked by the goal line, two lines starting on the goal line 16.5 m (18 yd) from the goalposts and extending 16.5 m (18 yd) into the pitch perpendicular to the goal line, and a line joining them. This area has a number of functions, the most prominent being to mark where the goalkeeper may handle the ball and where a penalty foul by a member of the defending team becomes punishable by a [[penalty kick (football)|penalty kick]]. Other markings define the position of the ball or players at kick-offs, goal kicks, penalty kicks and corner kicks.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws1_03.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 1.3–The field of play) |accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> |

|||

{{main|Attempts to ban football games}} |

|||

Numerous attempts have been made to ban football games, particularly the most rowdy and disruptive forms. This was especially the case in England and in other parts of Europe, during the [[Middle Ages]] and [[early modern Europe|early modern period]]. Between 1324 and 1667, football was banned in England alone by more than 30 royal and local laws. The need to repeatedly proclaim such laws demonstrated the difficulty in enforcing bans on popular games. |

|||

King [[Edward II of England|Edward II]] was so troubled by the unruliness of football in [[London]] that on [[April 13]], [[1314]] he issued a proclamation banning it: "Forasmuch as there is great noise in the city caused by hustling over large balls from which many evils may arise which God forbid; we command and forbid, on behalf of the King, on pain of imprisonment, such game to be used in the city in the future." |

|||

The reasons for the ban by [[Edward III of England|Edward III]], on [[June 12]], [[1349]], were explicit: football and other recreations distracted the populace from practicing [[archery]], which was necessary for war. |

|||

=== Duration and tie-breaking methods === |

|||

By [[1608]], the local authorities in [[Manchester]] were complaining that: "With the ffotebale...[there] hath beene greate disorder in our towne of Manchester we are told, and glasse windowes broken yearlye and spoyled by a companie of lewd and disordered persons ..."<ref>[http://www.sport.gov.gr/2/24/243/2431/24314/243144/paper20.html International Olympic Academy (I.O.A.) (no date), “Minutes 7th International Post Graduate Seminar on Olympic Studies”]</ref> That same year, the word |

|||

A standard adult football match consists of two periods of 45 minutes each, known as halves. Each half runs continuously, meaning that the clock is not stopped when the ball is out of play. There is usually a 15-minute "half-time" break between halves. The end of the match is known as full-time. |

|||

"football" was used disapprovingly by [[William Shakespeare]]. Shakespeare's play ''[[King Lear]]'' contains the line: "Nor tripped neither, you base football player" (Act I, Scene 4). |

|||

Shakespeare also mentions the game in ''[[A Comedy of Errors]]'' (Act II, Scene 1): |

|||

:''Am I so round with you as you with me,''<br> |

|||

:''That like a football you do spurn me thus?''<br> |

|||

:''You spurn me hence, and he will spurn me hither:''<br> |

|||

:''If I last in this service, you must case me in leather.'' |

|||

"Spurn" literally means ''to kick away'', thus implying that the game involved kicking a ball between players. |

|||

King [[James I of England]]'s ''Book of Sports'' (1618) however, instructs Christians to play at football every Sunday afternoon after worship.<ref>[http://books.google.co.uk/books?vid=LCCN25014901&id=sHrejZJVc80C&pg=RA3-PA412&dq=football&as_brr=1 John Lord Campbell, ''The Lives of the Lords Chancellors and Keepers of the Great Seal of England'', vol. 2, 1851, p. 412] </ref> The book's aim appears to be an attempt to offset the strictness of the [[Puritans]] regarding the keeping of the [[Sabbath in Christianity|Sabbath]].<ref>[http://www.reformed.org/books/hetherington/west_assembly/index.html?mainframe=/books/hetherington/west_assembly/chapter_1a.html#Book%20of%20Sports1618 William Maxwell Hetherington, 1856, ''History of the Westminster Assembly of Divines, Ch.1 (Third Ed.)] </ref> |

|||

The referee is the official timekeeper for the match, and may make an allowance for time lost through substitutions, injured players requiring attention, or other stoppages. This added time is commonly referred to as ''stoppage time'' or ''injury time'', and is at the sole discretion of the referee. The referee alone signals the end of the match. In matches where a fourth official is appointed, toward the end of the half the referee signals how many minutes of stoppage time he intends to add. The fourth official then informs the players and spectators by holding up a board showing this number. The signalled stoppage time may be further extended by the referee.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws7_02.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 7.2–The duration of the match) |accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> |

|||

===Establishment of modern codes=== |

|||

In league competitions, games may end in a draw, but in some knockout competitions if a game is tied at the end of regulation time it may go into extra time, which consists of two further 15-minute periods. If the score is still tied after extra time, some competitions allow the use of [[penalty shootout (football)|penalty shootouts]] (known officially in the Laws of the Game as "kicks from the penalty mark") to determine which team will progress to the next stage of the tournament. Goals scored during extra time periods count toward the final score of the game, but kicks from the penalty mark are only used to decide the team that progresses to the next part of the tournament (with goals scored in a penalty shootout not making up part of the final score). |

|||

====English public schools==== |

|||

{{main|English public school football games}} |

|||

While football continued to be played in various forms throughout Britain, its [[public school (England)|public schools]] (known as private schools in other countries) are widely credited with four key achievements in the creation of modern football codes. First of all, the evidence suggests that they were important in taking football away from its "mob" form and turning it into an organised team sport. Second, many early descriptions of football and references to it were recorded by people who had studied at these schools. Third, it was teachers, students and former students from these schools who first codified football games, to enable matches to be played between schools. Finally, it was at English public schools that the division between "kicking" and "running" (or "carrying") games first became clear. |

|||

The earliest evidence that games resembling football were being played at English public schools — mainly attended by boys from the upper, upper-middle and professional classes — comes from the ''Vulgaria'' by [[William Horman]] in 1519. Horman had been headmaster at [[Eton College|Eton]] and [[Winchester College|Winchester]] colleges and his [[Latin]] textbook includes a translation exercise with the phrase "We wyll playe with a ball full of wynde". |

|||

Competitions held over two legs (in which each team plays at home once) may use the [[away goals rule]] to determine which team progresses in the event of equal aggregate scores. If the result is still equal, kicks from the penalty mark are usually required, though some competitions may require a tied game to be replayed. |

|||

[[Richard Mulcaster]], a student at [[Eton College]] in the early [[16th century]] and later headmaster at other English schools, has been described as “the greatest sixteenth Century advocate of football”.<ref>[http://www.footballnetwork.org/dev/historyoffootball/history8_18_3.asp footballnetwork.org , 2003, “Richard Mulcaster”]</ref> Among his contributions are the earliest evidence of organised team football. Mulcaster's writings refer to teams ("sides" and "parties"), positions ("standings"), a referee ("judge over the parties") and a coach "(trayning maister)". Mulcaster's "footeball" had evolved from the disordered and violent forms of traditional football: |

|||

In the late 1990s, the [[IFAB]] experimented with ways of creating a winner without requiring a penalty shootout, which was often seen as an undesirable way to end a match. These involved rules ending a game in extra time early, either when the first goal in extra time was scored (''[[golden goal]]''), or if one team held a lead at the end of the first period of extra time (''[[silver goal]]''). Golden goal was used at the World Cup in [[1998 FIFA World Cup|1998]] and [[2002 FIFA World Cup|2002]]. The first World Cup game decided by a golden goal was [[France national football team|France]]'s victory over [[Paraguay national football team|Paraguay]] in 1998. [[Germany national football team|Germany]] was the first nation to score a golden goal in a major competition, beating [[Czech Republic national football team|Czech Republic]] in the final of [[Euro 1996]]. Silver goal was used in [[Euro 2004]]. Both these experiments have been discontinued by IFAB.<ref>{{cite web | title = Time running out for silver goal | work = Reuters| url = http://www.rediff.com/sports/2004/jul/02silver.htm | author = Collett, Mike | date = [[2004-07-02]] | accessdate =2007-10-07}}</ref> |

|||

:''[s]ome smaller number with such overlooking, sorted into sides and standings, not meeting with their bodies so boisterously to trie their strength: nor shouldring or shuffing one an other so barbarously ... may use footeball for as much good to the body, by the chiefe use of the legges.'' |

|||

In [[1633]], David Wedderburn, a teacher from [[Aberdeen]], mentioned elements of modern football games in a short [[Latin]] textbook called "Vocabula." Wedderburn refers to what has been translated into modern English as "keeping goal" and makes an allusion to passing the ball ("strike it here"). There is a reference to "get hold of the ball," suggesting that some handling was allowed. It is clear that the tackles allowed included the charging and holding of opposing players ("drive that man back"). |

|||

=== Ball in and out of play === |

|||

{{main|Ball in and out of play}} |

|||

A more detailed description of football is given in [[Francis Willughby]]'s ''Book of Games'', written in about [[1660]].<ref>[http://books.google.co.uk/books?vid=ISBN1859284604&id=P-io9DcBllkC&pg=PA168&lpg=PA168&vq=football&dq=willughby+book+of+sports&sig=qfpFofLjtqtwe0Y13Av4KZHvSA8 Francis Willughby, 1660-72, ''Book of Games'']</ref> Willughby, who had studied at [[Sutton Coldfield School]], is the first to describe goals and a distinct playing field: "a close that has a gate at either end. The gates are called Goals." His book includes a diagram illustrating a football field. He also mentions tactics ("leaving some of their best players to guard the goal"); scoring ("they that can strike the ball through their opponents' goal first win") and the way teams were selected ("the players being equally divided according to their strength and nimbleness"). He is the first to describe a "law" of football: "they must not strike [an opponent's leg] higher than the ball" |

|||

Under the Laws, the two basic states of play during a game are ''ball in play'' and ''ball out of play''. From the beginning of each playing period with a [[kick-off (football)|kick-off]] (a set kick from the centre-spot by one team) until the end of the playing period, the ball is in play at all times, except when either the ball leaves the field of play, or play is stopped by the referee. When the ball becomes out of play, play is restarted by one of eight restart methods depending on how it went out of play: |

|||

[[Image:FreekickatLincoln.JPG|thumb|right|A player about to take a free kick.]] |

|||

* Kick-off: following a goal by the opposing team, or to begin each period of play.<ref name="restart"/> |

|||

* [[Throw-in]]: when the ball has wholly crossed the touchline; awarded to opposing team to that which last touched the ball.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws15_01.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 15–The Throw-in) |accessdate=2007-10-14}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Goal kick]]: when the ball has wholly crossed the goal line without a goal having been scored and having last been touched by an attacker; awarded to defending team.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws16_01.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 16–The Goal Kick) |accessdate=2007-10-14}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Corner kick]]: when the ball has wholly crossed the goal line without a goal having been scored and having last been touched by a defender; awarded to attacking team.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws17_01.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 17–The Corner Kick) |accessdate=2007-10-14}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Indirect free kick]]: awarded to the opposing team following "non-penal" fouls, certain technical infringements, or when play is stopped to caution or send-off an opponent without a specific foul having occurred. A goal may not be scored directly from an indirect free kick.<ref name="freekick">{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws13_01.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 13–Free Kicks) |accessdate=2007-10-14}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Direct free kick]]: awarded to fouled team following certain listed "penal" fouls.<ref name="freekick"/> |

|||

* [[Penalty kick (football)|Penalty kick]]: awarded to the fouled team following a foul usually punishable by a direct free kick but that has occurred within their opponent's penalty area.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fifa.com/flash/lotg/football/en/Laws14_01.htm |publisher=FIFA |title=Laws of the game (Law 14–The Penalty Kick) |accessdate=2007-10-14}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Dropped-ball]]: occurs when the referee has stopped play for any other reason, such as a serious injury to a player, interference by an external party, or a ball becoming defective. This restart is uncommon in adult games.<ref name="restart"/> |

|||

English public schools also devised the first ''[[offside]]'' rules, during the late [[18th century]].<ref name=Carosi>[http://mysite.wanadoo-members.co.uk/corshamref/sub/offhist.htm Julian Carosi, 2006, "The History of Offside"]</ref> In the earliest manifestations of these rules, players were "off their side" if they simply stood between the ball and the goal which was their objective. Players were not allowed to pass the ball forward, either by foot or by hand. They could only dribble with their feet, or advance the ball in a ''[[scrum]]'' or similar ''formation''. However, offside laws began to diverge and develop differently at the each school, as is shown by the rules of football from Winchester, [[Rugby School|Rugby]], [[Harrow School|Harrow]] and [[Cheltenham School|Cheltenham]], during in the period of 1810-1850.<ref name=Carosi/> |

|||

=== Fouls and misconduct === |

|||

{{double image|right|Yellow card.svg|60|Red card.svg|60|Players are cautioned with a yellow card, and sent off with a red card.}} |

|||

A [[foul (football)|foul]] occurs when a player commits an offence listed in the Laws of the Game while the ball is in play. The offences that constitute a foul are listed in Law 12. Handling the ball deliberately, tripping an opponent, or pushing an opponent, are examples of "penal fouls", punishable by a [[direct free kick]] or [[penalty kick (football)|penalty kick]] depending on where the offence occurred. Other fouls are punishable by an [[indirect free kick]].<ref name="fouls"/> |

|||

[[Image:Ryan Valentine scores.jpg|thumb|left|A player scores a penalty kick given after an offence is committed inside the penalty box]] |

|||

The referee may punish a player or substitute's [[misconduct (football)|misconduct]] by a caution (yellow card) or sending-off (red card). A second yellow card at the same game leads to a red card, and therefore to a sending-off. If a player has been sent-off, no substitute can be brought on in their place. Misconduct may occur at any time, and while the offences that constitute misconduct are listed, the definitions are broad. In particular, the offence of "unsporting behaviour" may be used to deal with most events that violate the spirit of the game, even if they are not listed as specific offences. A referee can show a yellow or red card to a player, substitute or substituted player. Non-players such as managers and support staff cannot be shown the yellow or red card, but may be expelled from the technical area if they fail to conduct themselves in a responsible manner.<ref name="fouls"/> |

|||

By the early [[19th century]], (before the [[Factory Act 1850|''Factory Act'' of 1850]]), most [[working class]] people in Britain had to work six days a week, often for over twelve hours a day. They had neither the time nor the inclination to engage in sport for recreation and, at the time, many [[Child labour#Industrial Revolution|children were part of the labour force]]. [[Feast day]] football played on the streets was in decline. Public school boys, who enjoyed some freedom from work, became the inventors of organised football games with formal codes of rules. |

|||

Rather than stopping play, the [[referee]] may allow play to continue if doing so will benefit the team against which an offence has been committed. This is known as "playing an advantage". The referee may "call back" play and penalise the original offence if the anticipated advantage does not ensue within a short period, typically taken to be four to five seconds. Even if an offence is not penalised due to advantage being played, the offender may still be sanctioned for misconduct at the next stoppage of play. |

|||

Football was adopted by a number of public schools as a way of encouraging competitiveness and keeping youths fit. Each school drafted its own rules, which varied widely between different schools and were changed over time with each new intake of pupils. Two schools of thought developed regarding rules. Some schools favoured a game in which the ball could be carried (as at Rugby, [[Marlborough College|Marlborough]] and Cheltenham), while others preferred a game where kicking and dribbling the ball was promoted (as at Eton, Harrow, [[Westminster School|Westminster]] and [[Charterhouse School|Charterhouse]]). The division into these two camps was partly the result of circumstances in which the games were played. For example, Charterhouse and Westminster at the time had restricted playing areas; the boys were confined to playing their ball game within the school [[cloisters]], making it difficult for them to adopt rough and tumble running games. |

|||

The most complex of the Laws is [[offside (football)|offside]]. The offside law limits the ability of attacking players to remain forward (i.e. closer to the opponent's goal line) of the ball, the second-to-last defending player (which can include the goalkeeper), and the half-way line.<ref>{{cite web | title = The History of Offside | work = Julian Carosi | url = http://mysite.wanadoo-members.co.uk/corshamref/sub/offhist.htm | accessdate =2006-06-03}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Rugby School 850.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Rugby School]] [[William Webb Ellis]], a pupil at Rugby School, is said to have "showed a fine disregard for the rules of football, ''as played in his time'' [emphasis added]" by picking up the ball and running to the opponents' goal in 1823. This act is usually said to be the beginning of Rugby football, but there is little evidence that it occurred, and most sports historians believe the story to be apocryphal. Handling the ball was allowed, or even compulsory,<ref>For example, the English writer [[William Hone]], writing in [[1825]] or 1826, quotes the social commentator Sir [[Frederick Morton Eden]], regarding "Foot-Ball", as played at [[Scone, Scotland]]: |

|||

== Governing bodies == |

|||

:''The game was this: he who at any time got the ball into his hands, run [sic] with it till overtaken by one of the opposite part; and then, if he could shake himself loose from those on the opposite side who seized him, he run on; if not, he threw the ball from him, unless it was wrested from him by the other party,'' but no person was allowed to kick it. ([http://www.uab.edu/english/hone/etexts/edb/day-pages/046-february15.html William Hone, 1825-26, ''The Every-Day Book'', "February 15."] Access date: March 15, 2007.)</ref> in older forms of football. |

|||

{{seealso|Association football around the world}} |

|||

The recognised international governing body of football (and associated games, such as [[futsal]] and [[beach soccer]]) is the [[FIFA|Fédération Internationale de Football Association]] (FIFA). The FIFA headquarters are located in [[Zürich]]. |

|||

[[Railway Mania|The boom in rail transport in Britain]] during the 1840s meant that people were able to travel further and with less inconvenience than they ever had before. Inter-school sporting competitions became possible. However, it was difficult for schools to play each other at football, as each school played by its own rules. |

|||

Six regional confederations are associated with FIFA; these are: |

|||

Apart from Rugby football, the public school codes have barely been played beyond the confines of each school's playing fields. However, many of them are still played at the schools which created them (see [[Football#Surviving public school games|Surviving public school games]] below). |

|||

* Asia: [[Asian Football Confederation]] (AFC) |

|||

* Africa: [[Confederation of African Football]] (CAF) |

|||

* Central/North America & Caribbean: [[CONCACAF|Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football]] (CONCACAF; also known as The Football Confederation) |

|||

* Europe: [[UEFA|Union of European Football Associations]] (UEFA) |

|||

* Oceania: [[Oceania Football Confederation]] (OFC) |

|||

* South America: [[CONMEBOL|Confederación Sudamericana de Fútbol]] (South American Football Confederation; CONMEBOL) |

|||

====The first clubs==== |

|||

National associations oversee football within individual countries. These are affiliated both with FIFA and with their respective continental confederations. |

|||

{{main|Oldest football clubs}} |

|||

During this period, the Rugby school rules appear to have spread at least as far, perhaps further, than the other schools' codes. For example, two clubs which claim to be the world's [[Oldest football club|first and/or oldest football club]], in the sense of a club which is not part of a school or university, are strongholds of rugby football: the [[Barnes R.F.C.|Barnes Club]], said to have been founded in [[1839]], and [[Guy's Hospital Football Club]], in [[1843]]. Neither date nor the variety of football played is well-documented, but such claims nevertheless allude to the popularity of rugby before other modern codes emerged. |

|||

In [[1845]], three boys at Rugby school were tasked with codifying the rules then being used at the school. These were the first set of written rules (or code) for any form of football.<ref>{{cite web | title=Rugby chronology| work=Museum of Rugby | url=http://www.rfu.com/microsites/museum/index.cfm?fuseaction=faqs.chronology| accessmonthday=April 24 | accessyear=2006 }}</ref> This further assisted the spread of the Rugby game. For instance, [[Dublin University Football Club]] — founded at [[Trinity College, Dublin]] in [[1854]] and later famous as a bastion of the Rugby School game — is the world's oldest documented football club in any code. |

|||

== Major international competitions == |

|||

The major international competition in football is the [[FIFA World Cup|World Cup]], organised by FIFA. This competition takes place over a four-year period. More than 190 national teams compete in qualifying tournaments within the scope of continental confederations for a place in the finals. The finals tournament, which is held every four years, involves 32 national teams competing over a four-week period.<ref>The number of competing teams has varied over the history of the competition. The most recent changed was in [[1998 FIFA World Cup|1998]], from 24 to 32.</ref> The [[2006 FIFA World Cup]] took place in [[Germany]]; in 2010 it will be held in [[2010 FIFA World Cup|South Africa]].<ref>{{cite web | title = 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa | work = FIFA World Cup website | url = http://www.fifa.com/worldcup/index.html | accessdate =2007-10-07}}</ref> |

|||

====Cambridge rules==== |

|||

There has been a [[Football at the Summer Olympics|football tournament]] at every [[Summer Olympic Games]] since 1900, except at the 1932 games in [[1932 Summer Olympics|Los Angeles]]. Before the inception of the World Cup, the Olympics (especially during the 1920s) had the same status as the World Cup. Originally, the event was for amateurs only,<ref name=Wherebegan>{{cite web |url=http://web.archive.org/web/20070608215029/http://access.fifa.com/en/history/history/0,3504,4,00.html |title=Where it all began |publisher=FIFA official website |accessdate=2007-06-08}} (webarchive)</ref> however, since the [[1984 Summer Olympics]] professional players have been permitted, albeit with certain restrictions which prevent countries from fielding their strongest sides. Currently, the Olympic men's tournament is played at Under-23 level. In the past the Olympics have allowed a restricted number of over-age players per team;<ref>{{cite web |title=Football - An Olympic Sport since 1900 |work=IOC website |url=http://www.olympic.org/uk/sports/programme/index_uk.asp?SportCode=FB |accessdate=2007-10-07}}</ref> but that practice will cease in the 2008 Olympics. The Olympic competition is not generally considered to carry the same international significance and prestige as the World Cup. A women's tournament was added in 1996; in contrast to the men's event, full international sides without age restrictions play the women’s Olympic tournament. It thus carries international prestige considered comparable to that of the [[FIFA Women's World Cup]]. |

|||

{{main|Cambridge rules}} |

|||

In 1848, at [[University of Cambridge|Cambridge University]], [[H. de Winton and J. C. Thring|Mr. H. de Winton and Mr. J.C. Thring]], who were both formerly at [[Shrewsbury School]], called a meeting at [[Trinity College, Cambridge]] with 12 other representatives from Eton, Harrow, Rugby, [[Winchester College|Winchester]] and Shrewsbury. An eight-hour meeting produced what amounted to the first set of modern rules, known as the ''Cambridge rules''. No copy of these rules now exists, but a revised version from circa 1856 is held in the library of Shrewsbury School. The rules clearly favour the kicking game. Handling was only allowed for a player to take a ''clean catch'' entitling them to a free kick and there was a primitive offside rule, disallowing players from "loitering" around the opponents' goal. The Cambridge rules were not widely adopted outside English public schools and universities (but it was arguably the most significant influence on [[the Football Association]] committee members responsible for formulating the rules of [[Association football]]). |

|||

====The first modern balls==== |

|||

After the World Cup, the most important football competitions are the continental championships, which are organised by each continental confederation and contested between national teams. These are the [[European Football Championship|European Championship]] (UEFA), the [[Copa América]] (CONMEBOL), [[African Cup of Nations]] (CAF), the [[Asian Cup]] (AFC), the [[CONCACAF Gold Cup]] (CONCACAF) and the [[OFC Nations Cup]] (OFC). The most prestigious competitions in club football are the respective continental championships, which are generally contested between national champions, for example the [[UEFA Champions League]] in [[Europe]] and the [[Copa Libertadores de América]] in [[South America]]. The winners of each continental competition contest the [[FIFA Club World Cup]].<ref>{{cite web | title = Organising Committee strengthens FIFA Club World Cup format | work = [[FIFA]]| url = http://www.fifa.com/clubworldcup/organisation/media/newsid=570740.html|date=[[2007-08-24]] | accessdate =2007-10-07}}</ref> |

|||

{{main|football (ball)}} |

|||

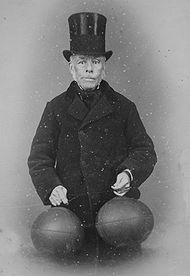

[[Image:Richard Lindon (1816-1887).jpg|190px|thumb|[[Richard Lindon]] (seen in 1880) is believed to have invented the first footballs with rubber bladders.]] In Europe, early footballs were made out of animal [[urinary bladder|bladder]]s, more specifically pig's bladders, which were inflated. Later [[leather]] coverings were introduced to allow the ball to keep their shape.<ref>[http://www.soccerballworld.com/History.htm#Early Soccer Ball World - Early History] <small>(Accessed [[June 9]] [[2006]])</small> </ref> However, in 1851, [[Richard Lindon]] and [[William Gilbert (Rugby)|William Gilbert]], both shoemakers from the town of [[Rugby, Warwickshire|Rugby]] (near the school), exhibited both round and oval-shaped balls at the [[Great Exhibition]] in [[London]]. Richard Lindon's wife is said to have died due to lung disease caused by blowing up pig's bladders.<ref>The exact name of Mr Lindon is in dispute, as well as the exact timing of the creation of the inflatable bladder. It is known that he created this for both association and rugby footballs. However, sites devoted to football indicate he was known as [http://www.richardlindon.com HJ Lindon], who was actually Richards Lindon's son, and created the ball in [[1862]] (ref: [http://www.soccerballworld.com/History.htm Soccer Ball World]), whereas rugby sites refer to him as [[Richard Lindon]] creating the ball in [[1870]] (ref: [http://observer.guardian.co.uk/osm/story/0,,1699545,00.html Guardian article]). Both agree that his wife died when inflating pig's bladders. This information originated from web sites which may be unreliable, and the answer may only be found in researching books in central libraries.</ref> Lindon also won medals for the invention of the "Rubber inflatable Bladder" and the "Brass Hand Pump". |

|||

== Domestic competitions == |

|||

{{main|Association football around the world}} |

|||

In [[1855]], the U.S. inventor [[Charles Goodyear]] — who had patented [[vulcanized rubber]] — exhibited a spherical football, with an exterior of vulcanized rubber panels, at the [[Exposition Universelle (1855)|Paris ''Exhibition Universelle'']]. The ball was to prove popular in early forms of football in the U.S.A.<ref>[http://www.soccerballworld.com/Oldestball.htm soccerballworld.com, (no date) "Charles Goodyear's Soccer Ball"] <small>Downloaded 30/11/06.</small> </ref> |

|||

The governing bodies in each country operate [[league system]]s, normally comprising several [[division (sport)|division]]s, in which the teams gain points throughout the season depending on results. Teams are placed into [[table (information)|table]]s, placing them in order according to points accrued. Most commonly, each team plays every other team in its league at home and away in each season, in a [[round-robin tournament]]. At the end of a season, the top team are declared the champions. The top few teams may be [[promotion and relegation|promoted]] to a higher division, and one or more of the teams finishing at the bottom are [[promotion and relegation|relegated]] to a lower division. The teams finishing at the top of a country's league may be eligible also to play in international club competitions in the following season. The main exceptions to this system occur in some [[Latin America]]n leagues, which divide football championships into two sections named [[Apertura and Clausura]], awarding a champion for each. |

|||

====Sheffield rules==== |

|||

The majority of countries supplement the league system with one or more ''cup'' competitions. These are organised on a [[single elimination tournament|knock-out]] basis, the winner of each match proceeding to the next round; the loser takes no further part in the competition. |

|||

{{main|Sheffield rules}} |

|||

By the late 1850s, many football clubs had been formed throughout the English-speaking world, to play various codes of football. |

|||

[[Sheffield F.C.|Sheffield Football Club]], founded in [[1857]] in the English city of [[Sheffield]] by Nathaniel Creswick and William Prest, was later recognised as the world's oldest club playing association football. However, the club initially played its own code of football: the ''Sheffield rules''. There were some similarities to the Cambridge rules, but players were allowed to push or ''hit'' the ball with their hands, and there was no ''offside'' rule at all, so that players known as ''kick throughs'' could be permanently positioned near the opponents' goal. The code spread to a number of clubs in the area and was popular until the 1870s. |

|||

Some countries' top divisions feature highly-paid star players; in smaller countries and lower divisions, players may be part-timers with a second job, or amateurs. The five top European leagues—the [[Premier League]] (England), the [[Fußball-Bundesliga|Bundesliga]] (Germany), [[La Liga]] (Spain), [[Ligue 1]] (France) and [[Serie A]] (Italy)—attract most of the world's best players. |

|||

====Australian rules==== |

|||

== Names of the game == |

|||

[[Image:Australianfootball1866.jpg|left|thumb|275px|An [[Australian rules football]] match at the [[Yarra Park|Richmond Paddock]], [[Melbourne]], in 1866. (A [[wood engraving]] by Robert Bruce.)]] |

|||

{{seealso|Names for association football|Football (word)}} |

|||

{{main|Australian rules football}} |

|||

<!-- |

|||

The invention of Australian rules football is usually attributed to [[Tom Wills]], who published a letter in ''Bell's Life in Victoria & Sporting Chronicle'', on [[July 10]], [[1858]], calling for a "foot-ball club" with a "code of laws" to keep cricketers fit during winter.<ref>{{cite web | title=Letter from Tom Wills | work=MCG website | url=http://www.mcg.org.au/default.asp?pg=footballdisplay&articleid=37|accessdate=2006-07-14}}</ref> (Official sources which include Wills' cousin, [[H.C.A. Harrison]], as a founder of the code are now generally believed to be incorrect.) |

|||

NB: Keep this overview article streamlined! Please place details/debate of what name is used where and other name debate issues is the dedicated article [[Names for association football]] rather than here! |

|||

--> |

|||