Benzodiazepine dependence: Difference between revisions

→Drug misuse and addiction: Adding some additional data. Moving some data to the benzodiazepine drug misuse article. |

|||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

==Drug misuse and addiction== |

==Drug misuse and addiction== |

||

{{See also|Benzodiazepine drug misuse}} |

{{See also|Benzodiazepine drug misuse}} |

||

Benzodiazepines can cause serious [[addiction]] problems. A survey in [[Senegal]] of doctors found that many doctors feel that their training and knowledge of benzodiazepines is generally poor. Due to the serious concerns of addiction [[national governments]] were recommended to urgently seek to raise knowledge via training about the [[addictive]] nature of [[benzodiazepines]] and appropriate prescribing of benzodiazepines.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Dièye AM, Sylla M, Ndiaye A, Ndiaye M, Sy GY, Faye B |title=Benzodiazepines prescription in Dakar: a study about prescribing habits and knowledge in general practitioners, neurologists and psychiatrists |journal=Fundam Clin Pharmacol |volume=20 |issue=3 |pages=235–8 |year=2006 |month=June |pmid=16671957 |doi=10.1111/j.1472-8206.2006.00400.x |url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118553133/abstract}}</ref> A six-year study on 51 [[Vietnam veterans]] who were drug abusers of either mainly [[stimulants]] (11 people), mainly opiates (26 people) or mainly benzodiazepines (14 people) was carried out to assess psychiatric symptoms related to the specific drugs of abuse. After six years, [[opiate]] abusers had little change in psychiatric symptomatology; 5 of the stimulant users had developed [[psychosis]], and 8 of the benzodiazepine users had developed depression. Therefore, long-term [[benzodiazepine abuse]] and dependence seems to carry a negative effect on [[mental health]], with a significant risk of causing depression.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Woody GE |coauthors= Mc Lellan AT O'Brien CP. |title=Development of psychiatric illness in drug abusers. Possible role of drug preference |journal=The New England journal of medicine. |volume=301 |issue=24 |pages=1310–4 |year=1979 |pmid=41182}}</ref> Benzodiazepines are also sometimes abused intranasally.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sheehan MF, Sheehan DV, Torres A, Coppola A, Francis E |title=Snorting benzodiazepines |journal=Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse |volume=17 |issue=4 |pages=457–68 |year=1991 |pmid=1684083 |doi= 10.3109/00952999109001605|url=}}</ref> |

Benzodiazepines can cause serious [[addiction]] problems. A survey in [[Senegal]] of doctors found that many doctors feel that their training and knowledge of benzodiazepines is generally poor. Due to the serious concerns of addiction [[national governments]] were recommended to urgently seek to raise knowledge via training about the [[addictive]] nature of [[benzodiazepines]] and appropriate prescribing of benzodiazepines.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Dièye AM, Sylla M, Ndiaye A, Ndiaye M, Sy GY, Faye B |title=Benzodiazepines prescription in Dakar: a study about prescribing habits and knowledge in general practitioners, neurologists and psychiatrists |journal=Fundam Clin Pharmacol |volume=20 |issue=3 |pages=235–8 |year=2006 |month=June |pmid=16671957 |doi=10.1111/j.1472-8206.2006.00400.x |url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118553133/abstract}}</ref> Another study in [[Dakar]] found that almost one fifth of doctors ignored prescribing guidelines regarding short term use of benzodiazepines and almost three quarters of doctors regarded their training and knowledge of benzodiazepines to be inadequate. More training regarding benzodiazepines has been recommended for doctors.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Dièye AM, Sy AN, Sy GY, ''et al.'' |title=[Prescription of benzodiazepines by general practitioners in the private sector of Dakar: survey on knowledge and attitudes] |language=French |journal=Therapie |volume=62 |issue=2 |pages=163–8 |year=2007 |pmid=17582318 |doi=10.2515/therapie:2007018 |url=http://publications.edpsciences.org/10.2515/therapie:2007018}}</ref> A six-year study on 51 [[Vietnam veterans]] who were drug abusers of either mainly [[stimulants]] (11 people), mainly opiates (26 people) or mainly benzodiazepines (14 people) was carried out to assess psychiatric symptoms related to the specific drugs of abuse. After six years, [[opiate]] abusers had little change in psychiatric symptomatology; 5 of the stimulant users had developed [[psychosis]], and 8 of the benzodiazepine users had developed depression. Therefore, long-term [[benzodiazepine abuse]] and dependence seems to carry a negative effect on [[mental health]], with a significant risk of causing depression.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Woody GE |coauthors= Mc Lellan AT O'Brien CP. |title=Development of psychiatric illness in drug abusers. Possible role of drug preference |journal=The New England journal of medicine. |volume=301 |issue=24 |pages=1310–4 |year=1979 |pmid=41182}}</ref> Benzodiazepines are also sometimes abused intranasally.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sheehan MF, Sheehan DV, Torres A, Coppola A, Francis E |title=Snorting benzodiazepines |journal=Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse |volume=17 |issue=4 |pages=457–68 |year=1991 |pmid=1684083 |doi= 10.3109/00952999109001605|url=}}</ref> |

||

A 2004 US government study of nationwide ED visits conducted by [[SAMHSA]] found that sedative-hypnotics in the USA are the most frequently misused pharmaceutical drug with 35% of drug related visits to the Emergency Department involving sedative hypnotics. Benzodiazepines accounted for the majority of these. Benzodiazepines are more commonly misused than opiate pharmaceuticals which accounted for 32% of visits to the emergency department. Males and females misuse benzodiazepines equally. Of drugs used in attempted suicide, benzodiazepines are the most commonly used pharmaceutical drug with 26% of attempted suicides involving benzodiazepines. Alprazolam is the most commonly misused benzodiazepine, followed clonazepam, lorazepam and diazepam as the 4th most commonly misused benzodiazepine in the USA.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://dawninfo.samhsa.gov/files/DAWN2k4ED.htm|title= Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2004: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits|dateformat= dmy|accessdate= 9 May 2008|author= United States Government|authorlink= SAMHSA|coauthors= U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES|year= 2004|publisher= Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration}}</ref> |

|||

In the [[elderly]] [[ethanol|alcohol]] and [[benzodiazepines]] are the most commonly abused substances. Abuse of sedative hypnotics such as alcohol or benzodiazepines is more problematic in the elderly because they are more sensitive to the adverse effects and experience a more severe [[withdrawal syndrome]] with withdrawal related [[delerium]] being more common in the elderly than in younger patients.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wetterling T, Backhaus J, Junghanns K |title=[Addiction in the elderly - an underestimated diagnosis in clinical practice?] |language=German |journal=Nervenarzt |volume=73 |issue=9 |pages=861–6 |year=2002 |month=September |pmid=12215877 |doi=10.1007/s00115-002-1359-3}}</ref> |

In the [[elderly]] [[ethanol|alcohol]] and [[benzodiazepines]] are the most commonly abused substances. Abuse of sedative hypnotics such as alcohol or benzodiazepines is more problematic in the elderly because they are more sensitive to the adverse effects and experience a more severe [[withdrawal syndrome]] with withdrawal related [[delerium]] being more common in the elderly than in younger patients.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wetterling T, Backhaus J, Junghanns K |title=[Addiction in the elderly - an underestimated diagnosis in clinical practice?] |language=German |journal=Nervenarzt |volume=73 |issue=9 |pages=861–6 |year=2002 |month=September |pmid=12215877 |doi=10.1007/s00115-002-1359-3}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:06, 31 May 2009

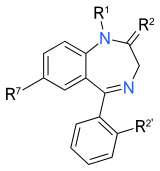

| Benzodiazepines |

|---|

|

| Benzodiazepine dependence | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Benzodiazepine dependence or benzodiazepine addiction is the condition when a person is dependent on benzodiazepine drugs. Dependence can either be a psychological dependence (addiction) or a physical dependence or a combination of the two. Physical dependence occurs when a person becomes tolerant to benzodiazepines and as a result of the physiological tolerance they develop a physical dependence which can manifest itself upon dosage reduction or withdrawal as the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Addiction or what it is sometimes referred to as psychological dependence includes people who misuse and/or crave the drug not to relieve withdrawal symptoms but to experience its euphoric and or intoxicating effects. Addiction to benzodiazepines can also include people who are not abusing benzodiazepines but take them as prescribed who psychologically can't stop taking benzodiazepines despite the drug causing harm. It is important to distinguish between addiction and drug abuse of benzodiazepines and normal physical dependence on benzodiazepines. Physical dependence typically occurs from long term prescribed use but drug abuse and/or addiction does not typically occur in prescribed users.[1]

Benzodiazepines can be addictive and induce dependence even at low doses, with 23% becoming addicted within 3 months of use. Benzodiazepine addiction is considered a public health problem. Approximately 68.5% of prescriptions of benzodiazepines originate from local health centers, with psychiatry and general hospitals accounting for 10% each. A survery of General Practitioners reported that the reason for initiating benzodiazepines was due to an empathy for the patients suffering and a lack of other therapeutic options rather than patients demanding them. However, long term use was more commonly at the insistence of the patient, presumably because physical dependence and/or addiction had developed.[2][3][4]

Tolerance and physical dependence

Physical dependence

Regular use of benzodiazepines at prescribed levels for six weeks was found to produce a significant risk of dependence, with resultant withdrawal symptoms appearing on abrupt discontinuation in a study assessing diazepam and buspirone. However, with abrupt withdrawal after six weeks of treatment with buspirone, no withdrawal symptoms developed.[5] Various studies have shown between 20–100% of patients prescribed benzodiazepines at therapeutic dosages long term are physically dependent and will experience withdrawal symptoms.[6]

Benzodiazepine dependence is a frequent complication when they are prescribed for or taken for longer than four weeks, with physical dependence and withdrawal symptoms being the most common problem, but also occasionally drug-seeking behavior. Withdrawal symptoms include anxiety, perceptual disturbances, distortion of all the senses, dysphoria and in rare cases, psychosis and epileptic seizures. The risk factors for benzodiazepine dependence are long-term use beyond four weeks, use of high doses and use of potent short-acting benzodiazepines among those with certain pre-existing personality characteristics such as dependent personalities and those prone to drug abuse.[7]

Previously, physical dependence on benzodiazepines was largely thought to occur only in people on high-therapeutic-dose ranges and low- or normal-dose dependence was not suspected until the 1970s; and it wasn't until the early 1980s that it was confirmed.[8][9] However, low-dose dependence is now a recognized clinical disadvantage of benzodiazepines and severe withdrawal syndromes can occur from these low doses of benzodiazepines even after gradual dose reduction.[10][11] Low dose dependence has now been clearly demonstrated in both animal studies and human studies.[12][13]

In an animal study of four baboons on low-dose benzodiazepine treatment, three out of the four baboons demonstrated physical dependence and developed flumazenil-precipitated withdrawal symptoms after only two weeks of low-dose benzodiazepine treatment. Furthermore, the baboons on low-dose therapy did not develop more severe flumazenil-precipitated withdrawal symptoms when low-dose benzodiazepine therapy was continued over a period of 6–10 months, suggesting rapid onset of tolerance and dependence with benzodiazepines and suggesting that physical dependence was complete after two weeks of chronic, low-dose benzodiazepine treatment.[14] In another animal study, physical dependence was demonstrated with withdrawal signs appearing after only seven days of low-dose benzodiazepine treatment and withdrawal signs appeared after only three days after high-dose treatment, which demonstrated the extremely rapid development of tolerance and dependence on benzodiazepines, at least in baboons. It was also found that previous exposure to benzodiazepines sensitized baboons to the development of physical dependence.[15]

In humans, chronic, low-therapeutic-dose dependence was demonstrated in experimentally precipitated withdrawal using flumazenil to show physical dependence and withdrawal signs. Withdrawal symptoms experienced by the chronic therapeutic low-dose subjects included increased ratings of dizziness, blurred vision, heart pounding, feelings of unreality, pins and needles, nausea, sweatiness, noises louder than usual, jitteriness, things moving, sensitivity to touch. Healthy control subjects who were not dependent on benzodiazepines exhibited no benzodiazepine withdrawal like effects or notable side effects.[16] In another study of 34 low-dose benzodiazepine users, physiological dependence was demonstrated by the appearance of withdrawal symptoms in 100% of those who received flumazenil whereas those receiving placebo experienced no withdrawal signs. It was also found that those dependent on low doses of benzodiazepines with a history of panic attacks were at an increased risk of suffering panic attacks due to flumazenil precipitated benzodiazepine withdrawal.[17] It has been estimated that 30–45% of chronic low dose benzodiazepine users are dependent and it has been recommended that benzodiazepines even at low dosage be prescribed for a maximum of 7–14 days to avoid dependence.[18]

Some controversy remains, however, in the medical literature as to the exact nature of low-dose dependence and the difficulty in getting patients to discontinue their benzodiazepines, with some papers attributing the problem to predominantly drug-seeking behavior and drug craving, whereas other papers have found the opposite, attributing the problem to a problem of physical dependence with drug-seeking and craving not being typical of low-dose benzodiazepine users.[19][20]

Tolerance

Tolerance in humans to the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines develops over a period of 3 months. Tolerance to the anxiolytic effect of benzodiazepines also occurs in animals. The study found that tolerance does not occur at the GABA binding site on the GABAA receptor but that tolerance occurs at the benzodiazepine site on the GABAA receptor.[21][22] Glutamate receptors and especially NMDA receptors also appear to play an important role in benzodiazepine tolerance, dependence and withdrawal.[23][24][25] Tolerance to the anticonvulsant effect of benzodiazepines also develops in both humans and animals.[26][27] A decrease in benzodiazepine binding sites in the brain may also occur as part of benzodiazepine tolerance.[28]

Patients taking daily benzodiazepine drugs have a reduced sensitivity to further additional doses of benzodiazepines.[29]

Cross tolerance

Benzodiazepines share a similar mechanism of action with various sedative compounds that act by enhancing the GABAA receptor. Cross tolerance means that one drug will alleviate the withdrawal effects of another. It also means that tolerance of one drug will result in tolerance of another similarly-acting drug. Benzodiazepines are often used for this reason to detoxify alcohol-dependent patients and can have life-saving properties in preventing and/or treating severe life-threatening withdrawal syndromes from alcohol, such as delirium tremens. However, although benzodiazepines can be very useful in the acute detoxification of alcoholics, benzodiazepines in themselves act as positive reinforcers in alcoholics, by increasing the desire for alcohol. Low doses of benzodiazepines were found to significantly increase the level of alcohol consumed in alcoholics.[30] However, alcoholics dependent on benzodiazepines should not be abruptly withdrawn but be very slowly withdrawn from benzodiazepines as over-rapid withdrawal is likely to produce severe anxiety or panic, which is well known for being a relapse risk factor in recovering alcoholics.[31]

There is also cross tolerance between alcohol, the benzodiazepines, the barbiturates and the nonbenzodiazepine drugs, corticosteroids which all act by enhancing the GABAA receptor's function via modulating the chloride ion channel function of the GABAA receptor.[32][33][34][35][36]

The Committee on the Review of Medicines (UK)

The Committee on the Review of Medicines carried out a review into benzodiazepines due to significant concerns of tolerance, drug dependence and benzodiazepine withdrawal problems and other adverse effects. The committee found that benzodiazepines do not have any antidepressant or analgesic properties and are therefore unsuitable treatments for conditions such as depression, tension headaches and dysmenorrhoea. Benzodiazepines are also not beneficial in the treatment of psychosis. The committee also recommended against benzodiazepines being used in the treatment of anxiety or insomnia in children. The committee was in agreement with the Institute of Medicine (USA) and the conclusions of a study carried out by the White House Office of Drug Policy and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (USA) that there was little evidence that long term use of benzodiazepine hypnotics were beneficial in the treatment of insomnia due to the development of tolerance. Benzodiazepines tended to lose their sleep promoting properties within 3–14 days of continuous use and in the treatment of anxiety the committee found that there was little convincing evidence that benzodiazepines retained efficacy in the treatment of anxiety after 4 months continuous use due to the development of tolerance. The committee found that the regular use of benzodiazepines caused the development of dependence characterised by tolerance to the therapeutic effects of benzodiazepines and the development of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome including symptoms such as anxiety, apprehension, tremor, insomnia, nausea, and vomiting upon cessation of benzodiazepine use. Withdrawal symptoms tended to develop within 24 hours upon cessation of short acting; and 3–10 days after cessation of longer acting benzodiazepines. Withdrawal effects could occur after treatment lasting only 2 weeks at therapeutic dose levels however withdrawal effects tended to occur with habitual use beyond 2 weeks and were more likely the higher the dose. The withdrawal symptoms may appear to be similar to the original condition. The committee recommended that all benzodiazepine treatment be withdrawn gradually and recommended that benzodiazepine treatment be used only in carefully selected patients and that therapy be limited to short term use only. It was noted in the review that alcohol can potentiate the central nervous system depressant effects of benzodiazepines and should be avoided. The central nervous system depressant effects of benzodiazepines may make driving or operating machinery dangerous and the elderly are more prone to these adverse effects. In the neonate high single doses or repeated low doses have been reported to produce hypotonia, poor sucking, and hypothermia in the neonate and irregularities in the fetal heart. Benzodiazepines should be avoided in lactation. Withdrawal from benzodiazepines should be gradual as abrupt withdrawal from high doses of benzodiazepines may cause confusion, toxic psychosis, convulsions, or a condition resembling delirium tremens. Abrupt withdrawal from lower doses may cause depression, nervousness, rebound insomnia, irritability, sweating, and diarrhea.[37]

Drug misuse and addiction

Benzodiazepines can cause serious addiction problems. A survey in Senegal of doctors found that many doctors feel that their training and knowledge of benzodiazepines is generally poor. Due to the serious concerns of addiction national governments were recommended to urgently seek to raise knowledge via training about the addictive nature of benzodiazepines and appropriate prescribing of benzodiazepines.[38] Another study in Dakar found that almost one fifth of doctors ignored prescribing guidelines regarding short term use of benzodiazepines and almost three quarters of doctors regarded their training and knowledge of benzodiazepines to be inadequate. More training regarding benzodiazepines has been recommended for doctors.[39] A six-year study on 51 Vietnam veterans who were drug abusers of either mainly stimulants (11 people), mainly opiates (26 people) or mainly benzodiazepines (14 people) was carried out to assess psychiatric symptoms related to the specific drugs of abuse. After six years, opiate abusers had little change in psychiatric symptomatology; 5 of the stimulant users had developed psychosis, and 8 of the benzodiazepine users had developed depression. Therefore, long-term benzodiazepine abuse and dependence seems to carry a negative effect on mental health, with a significant risk of causing depression.[40] Benzodiazepines are also sometimes abused intranasally.[41]

In the elderly alcohol and benzodiazepines are the most commonly abused substances. Abuse of sedative hypnotics such as alcohol or benzodiazepines is more problematic in the elderly because they are more sensitive to the adverse effects and experience a more severe withdrawal syndrome with withdrawal related delerium being more common in the elderly than in younger patients.[42]

See also

- Benzodiazepine

- Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome

- Long term effects of benzodiazepines

- Alcohol withdrawal syndrome

- Long term effects of alcohol

- SSRI discontinuation syndrome

- Drug related crime

References

- ^ O'brien CP (2005). "Benzodiazepine use, abuse, and dependence". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 (Suppl 2): 28–33. PMID 15762817.

- ^ Anthierens S, Habraken H, Petrovic M, Christiaens T (2007). "The lesser evil? Initiating a benzodiazepine prescription in general practice: a qualitative study on GPs' perspectives" (PDF). Scand J Prim Health Care. 25 (4): 214–9. doi:10.1080/02813430701726335. PMID 18041658.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Granados Menéndez MI, Salinero Fort MA, Palomo Ancillo M, Aliaga Gutiérrez L, García Escalonilla C, Ortega Orcos R (2006). "[Appropriate use of benzodiazepines zolpidem and zopiclone in diseases attended in primary care]". Aten Primaria (in Spanish; Castilian). 38 (3): 159–64. PMID 16945275.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Barthelmé B, Poirot Y (2008). "[Anxiety level and addiction to first-time prescriptions of anxiolytics: a psychometric study]". Presse Med (in French). 37 (11): 1555–60. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2007.10.019. PMID 18502091.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Murphy SM, Owen R, Tyrer P. (1989). "Comparative assessment of efficacy and withdrawal symptoms after 6 and 12 weeks' treatment with diazepam or buspirone". The British Journal of Psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 154: 529–34. doi:10.1192/bjp.154.4.529. PMID 2686797.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ashton, CH (1997). "Benzodiazepine Dependency". In A Baum, S. Newman, J. Weinman, R. West, C. McManus (ed.). Cambridge Handbook of Psychology & Medicine. England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 376–80.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|accessmonth=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Marriott S, Tyrer P. (1993). "Benzodiazepine dependence. Avoidance and withdrawal". Drug safety : an international journal of medical toxicology and drug experience. 9 (2): 93–103. PMID 8104417.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fruensgaard K (1976). "Withdrawal psychosis: a study of 30 consecutive cases". Acta Psychiatr Scand. 53 (2): 105–18. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1976.tb00065.x. PMID 3091.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lader M. (1991). "History of benzodiazepine dependence". Journal of substance abuse treatment. 8 (1–2): 53–9. doi:10.1016/0740-5472(91)90027-8. PMID 1675692.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Lader M. (1987). "Long-term anxiolytic therapy: the issue of drug withdrawal". The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 48: 12–6. PMID 2891684.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Miura S (1992). "The future of 5-HT1A receptor agonists. (Aryl-piperazine derivatives)". Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 16 (6): 833–45. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(92)90103-L. PMID 1355301.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lucki I (1990). "Increased sensitivity to benzodiazepine antagonists in rats following chronic treatment with a low dose of diazepam". Psychopharmacology. 102 (3): 350–6. doi:10.1007/BF02244103. PMID 1979180.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rickels K (1986). "Low-dose dependence in chronic benzodiazepine users: a preliminary report on 119 patients". Psychopharmacology bulletin. 22 (2): 407–15. PMID 2877472.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaminski BJ (2003). "Physical dependence in baboons chronically treated with low and high doses of diazepam". Behavioural pharmacology. 14 (4): 331–42. PMID 12838039.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lukas SE (April 20, 1984). "Precipitated diazepam withdrawal in baboons: effects of dose and duration of diazepam exposure". European journal of pharmacology. 100 (2): 163–71. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(84)90218-8. PMID 6428921.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mintzer MZ (1999). "A controlled study of flumazenil-precipitated withdrawal in chronic, low-dose benzodiazepine users". 147 (2): 200–9. PMID 10591888.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bernik MA (1998). "Stressful reactions and panic attacks induced by flumazenil in chronic benzodiazepine users". Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 12 (2): 146–50. doi:10.1177/026988119801200205. PMID 9694026.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Meier PJ (March 19, 1988). "[Benzodiazepine--practice and problems of its use]". Schweizerische medizinische Wochenschrift. 118 (11): 381–92. PMID 3287602.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Linden M (1998). "Patient treatment insistence and medication craving in long-term low-dosage benzodiazepine prescriptions". Psychological medicine. 28 (3): 721–9. doi:10.1017/S0033291798006734. PMID 9626728.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tyrer P. (1993). "Benzodiazepine dependence: a shadowy diagnosis". Biochemical Society symposium. 59: 107–19. PMID 7910738.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Schmitt U, Lüddens H, Hiemke C (2001). "Behavioral analysis indicates benzodiazepine-tolerance mediated by the benzodiazepine binding-site at the GABA(A)-receptor". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 25 (5): 1145–60. doi:10.1016/S0278-5846(01)00166-X. PMID 11444682.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Committee on the Review of Medicines (March 29, 1980). "Systematic review of the benzodiazepines. Guidelines for data sheets on diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, medazepam, clorazepate, lorazepam, oxazepam, temazepam, triazolam, nitrazepam, and flurazepam. Committee on the Review of Medicines". Br Med J. 280 (6218): 910–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.280.6218.910. PMC 1601049. PMID 7388368.

- ^ Allison C, Pratt JA (2003). "Neuroadaptive processes in GABAergic and glutamatergic systems in benzodiazepine dependence". Pharmacol. Ther. 98 (2): 171–95. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(03)00029-9. PMID 12725868.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Koff JM, Pritchard GA, Greenblatt DJ, Miller LG (1997). "The NMDA receptor competitive antagonist CPP modulates benzodiazepine tolerance and discontinuation". Pharmacology. 55 (5): 217–27. doi:10.1159/000139531. PMID 9399331.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Koff JM, Pritchard GA, Greenblatt DJ, Miller LG (1997). "The NMDA receptor competitive antagonist CPP modulates benzodiazepine tolerance and discontinuation". Pharmacology. 55 (5): 217–27. doi:10.1159/000139531. PMID 9399331.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Loiseau P (1983). "[Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy]". Encephale. 9 (4 Suppl 2): 287B–292B. PMID 6373234.

- ^ Lilly SM, Zeng XJ, Tietz EI (2003). "Role of protein kinase A in GABAA receptor dysfunction in CA1 pyramidal cells following chronic benzodiazepine treatment". J. Neurochem. 85 (4): 988–98. PMID 12716430.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fujita M, Woods SW, Verhoeff NP; et al. (1999). "Changes of benzodiazepine receptors during chronic benzodiazepine administration in humans". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 368 (2–3): 161–72. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00013-8. PMID 10193652.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Potokar J, Coupland N, Wilson S, Rich A, Nutt D (1999). "Assessment of GABA(A)benzodiazepine receptor (GBzR) sensitivity in patients on benzodiazepines". Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 146 (2): 180–4. doi:10.1007/s002130051104. PMID 10525753.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Poulos CX (2004). "Low-dose diazepam primes motivation for alcohol and alcohol-related semantic networks in problem drinkers". Behavioural pharmacology. 15 (7): 503–12. doi:10.1097/00008877-200411000-00006. PMID 15472572.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C (2000). "The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings". Clin Psychol Rev. 20 (2): 149–71. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00027-6. PMID 10721495.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Khanna JM, Kalant H, Weiner J, Shah G (1992). "Rapid tolerance and cross-tolerance as predictors of chronic tolerance and cross-tolerance". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 41 (2): 355–60. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(92)90110-2. PMID 1574525.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Health Organisation - Assessment of Zopiclone

- ^ Allan AM, Baier LD, Zhang X (1992). "Effects of lorazepam tolerance and withdrawal on GABAA receptor-operated chloride channels". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 261 (2): 395–402. PMID 1374467.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rooke KC. (1976). "The use of flurazepam (dalmane) as a substitute for barbiturates and methaqualone/diphenhydramine (mandrax) in general practice". J Int Med Res. 4 (5): 355–9. PMID 18375.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Reddy DS (2000). "Chronic treatment with the neuroactive steroid ganaxolone in the rat induces anticonvulsant tolerance to diazepam but not to itself". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 295 (3): 1241–8. PMID 11082461.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Committee on the Review of Medicines (March 29, 1980). "Systematic review of the benzodiazepines. Guidelines for data sheets on diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, medazepam, clorazepate, lorazepam, oxazepam, temazepam, triazolam, nitrazepam, and flurazepam. Committee on the Review of Medicines". Br Med J. 280 (6218): 910–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.280.6218.910. PMC 1601049. PMID 7388368.

- ^ Dièye AM, Sylla M, Ndiaye A, Ndiaye M, Sy GY, Faye B (2006). "Benzodiazepines prescription in Dakar: a study about prescribing habits and knowledge in general practitioners, neurologists and psychiatrists". Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 20 (3): 235–8. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2006.00400.x. PMID 16671957.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dièye AM, Sy AN, Sy GY; et al. (2007). "[Prescription of benzodiazepines by general practitioners in the private sector of Dakar: survey on knowledge and attitudes]". Therapie (in French). 62 (2): 163–8. doi:10.2515/therapie:2007018. PMID 17582318.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Woody GE (1979). "Development of psychiatric illness in drug abusers. Possible role of drug preference". The New England journal of medicine. 301 (24): 1310–4. PMID 41182.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sheehan MF, Sheehan DV, Torres A, Coppola A, Francis E (1991). "Snorting benzodiazepines". Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 17 (4): 457–68. doi:10.3109/00952999109001605. PMID 1684083.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wetterling T, Backhaus J, Junghanns K (2002). "[Addiction in the elderly - an underestimated diagnosis in clinical practice?]". Nervenarzt (in German). 73 (9): 861–6. doi:10.1007/s00115-002-1359-3. PMID 12215877.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)