Joseph Smith: Difference between revisions

I can live with the caption |

→Family and descendants: Added statement for better flow |

||

| Line 211: | Line 211: | ||

Throughout her life and on her deathbed, Emma Smith frequently denied that her husband had ever taken additional wives.<ref>''Church History'', 3: 355–356.</ref> Emma claimed that the very first time she ever became aware of a polygamy revelation being attributed to Joseph by Mormons was when she read about it in [[Orson Pratt]]'s booklet ''The Seer'' in 1853.<ref>''Saints' Herald'' 65:1044–1045</ref> Emma campaigned publicly against polygamy and also authorized and was the main signatory of a petition in Summer 1842, with a thousand female signatures, denying that Joseph was connected with polygamy,<ref>''Times and Seasons'' 3 [August 1, 1842]: 869</ref> and as president of the Ladies' Relief Society, Emma authorized publishing a certificate in October 1842 denouncing polygamy and denying her husband as its creator or participant.<ref>''Times and Seasons'' 3 [October 1, 1842]: 940. In March 1844, Emma said, "we raise our voices and hands against John C. Bennett's 'spiritual wife system', as a scheme of profligates to seduce women; and they that harp upon it, wish to make it popular for the convenience of their own cupidity; wherefore, while the marriage bed, undefiled is honorable, let polygamy, bigamy, fornication, adultery, and prostitution, be frowned out of the hearts of honest men to drop in the gulf of fallen nature". The document ''The Voice of Innocence from Nauvoo''. signed by Emma Smith as President of the Ladies' Relief Society, was published within the article ''Virtue Will Triumph'', Nauvoo Neighbor, March 20, 1844 (''LDS History of the Church'' 6:236, 241) including on her deathbed where she stated "No such thing as polygamy, or spiritual wifery, was taught, publicly or privately, before my husband's death, that I have now, or ever had any knowledge of...He had no other wife but me; nor did he to my knowledge ever have". ''Church History''3: 355–356</ref> Even when her sons [[Joseph Smith III|Joseph III]] and [[Alexander Hale Smith|Alexander]] presented her with specific written questions about polygamy, she continued to deny that their father had been a polygamist.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Van Wagoner|1992|pp=113–115}} As Fawn Brodie has written, this denial was "her revenge and solace for all her heartache and humiliation." (Brodie, 399) "This was her slap at all the sly young girls in the [[Joseph Smith Mansion House|Mansion House]] who had looked first so worshipfully and then so knowingly at Joseph. She had given them the lie. Whatever formal ceremony he might have gone through, Joseph had never acknowledged one of them before the world." Newell and Avery wrote of "the paradox of Emma's position," quoting her friend and lawyer Judge George Edmunds who stated "that's just the hell of it! I can't account for it or reconcile her statements." {{Harv|Newell|Avery|1994|p=308}}</ref> |

Throughout her life and on her deathbed, Emma Smith frequently denied that her husband had ever taken additional wives.<ref>''Church History'', 3: 355–356.</ref> Emma claimed that the very first time she ever became aware of a polygamy revelation being attributed to Joseph by Mormons was when she read about it in [[Orson Pratt]]'s booklet ''The Seer'' in 1853.<ref>''Saints' Herald'' 65:1044–1045</ref> Emma campaigned publicly against polygamy and also authorized and was the main signatory of a petition in Summer 1842, with a thousand female signatures, denying that Joseph was connected with polygamy,<ref>''Times and Seasons'' 3 [August 1, 1842]: 869</ref> and as president of the Ladies' Relief Society, Emma authorized publishing a certificate in October 1842 denouncing polygamy and denying her husband as its creator or participant.<ref>''Times and Seasons'' 3 [October 1, 1842]: 940. In March 1844, Emma said, "we raise our voices and hands against John C. Bennett's 'spiritual wife system', as a scheme of profligates to seduce women; and they that harp upon it, wish to make it popular for the convenience of their own cupidity; wherefore, while the marriage bed, undefiled is honorable, let polygamy, bigamy, fornication, adultery, and prostitution, be frowned out of the hearts of honest men to drop in the gulf of fallen nature". The document ''The Voice of Innocence from Nauvoo''. signed by Emma Smith as President of the Ladies' Relief Society, was published within the article ''Virtue Will Triumph'', Nauvoo Neighbor, March 20, 1844 (''LDS History of the Church'' 6:236, 241) including on her deathbed where she stated "No such thing as polygamy, or spiritual wifery, was taught, publicly or privately, before my husband's death, that I have now, or ever had any knowledge of...He had no other wife but me; nor did he to my knowledge ever have". ''Church History''3: 355–356</ref> Even when her sons [[Joseph Smith III|Joseph III]] and [[Alexander Hale Smith|Alexander]] presented her with specific written questions about polygamy, she continued to deny that their father had been a polygamist.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Van Wagoner|1992|pp=113–115}} As Fawn Brodie has written, this denial was "her revenge and solace for all her heartache and humiliation." (Brodie, 399) "This was her slap at all the sly young girls in the [[Joseph Smith Mansion House|Mansion House]] who had looked first so worshipfully and then so knowingly at Joseph. She had given them the lie. Whatever formal ceremony he might have gone through, Joseph had never acknowledged one of them before the world." Newell and Avery wrote of "the paradox of Emma's position," quoting her friend and lawyer Judge George Edmunds who stated "that's just the hell of it! I can't account for it or reconcile her statements." {{Harv|Newell|Avery|1994|p=308}}</ref> |

||

After Smith's death, Emma Smith quickly became alienated from Brigham Young and the church leadership, largely over property matters and debt as it was difficult to disentangle Smith's personal property from that of the church.<ref>Bushman (2005), 554. Brodie says that she "came to fear and despise" Brigham Young. Brodie, 399.</ref> |

After Smith's death, Emma Smith quickly became alienated from Brigham Young and the church leadership, largely over property matters and debt as it was difficult to disentangle Smith's personal property from that of the church.<ref>Bushman (2005), 554. Brodie says that she "came to fear and despise" Brigham Young. Brodie, 399.</ref> Friction with the church leadership and her strong opposition to plural marriage "made her doubly troublesome"<ref>Bushman (2005), 554.</ref> to Young, who later stated "to my certain knowledge Emma Smith is one of the damnest liars I know of on this earth".<ref>Brigham Young, Address, October 7, 1866, Brigham Young Papers, Archives Division, Historical Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah, as cited in Avery, V.T. & Newell, L.K. "The Lion and the Lady: Brigham Young and Emma Smith," Utah Historical Quarterly 48 (Winter 1980): 82.</ref> When most Latter Day Saints moved west, she stayed in Nauvoo, married a non-Mormon, Major [[Lewis C. Bidamon]],<ref>Bushman (2005), 554–55. Emma Smith married Major [[Lewis Bidamon]], an "enterprising man who made good use of Emma's property." Although Bidamon sired an illegitimate child when he was 62 (whom Emma reared), "the couple showed genuine affection for each." Bushman (2205), 555.</ref> and withdrew from religion until 1860, when she affiliated with what became the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now known as [[Community of Christ]]), which was first headed by her son, [[Joseph Smith III]]. Emma never denied Joseph's prophetic gift or her belief in the Book of Mormon. |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 15:33, 14 March 2011

| Template:LDSInfobox/JS | ||||||

|

Joseph Smith, Jr. (December 23, 1805 – June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of what later became known as the Latter Day Saint movement. He was also an author, city planner, military leader, and U.S. presidential candidate.

Raised in western New York, a hotbed of religious enthusiasm, Smith was wary of Protestant sectarianism as a youth. His worldview was influenced by folk magic, and he became known locally as one who could divine the location of buried treasure. In the late 1820s, Smith said that an angel directed him to a buried book of golden plates inscribed with a religious history of ancient American peoples. After publishing what he said was an English translation of the plates as the Book of Mormon, he organized branches of the "Church of Christ". Adherents of this new religion would later be called Latter Day Saints.

In 1831, Smith moved west to Kirtland, Ohio with the intention of eventually establishing the communal holy city of Zion in western Missouri. These plans were obstructed, however, when Missouri settlers expelled the Saints from Zion in 1833. After leading an unsuccessful paramilitary expedition to recover the land, Smith focused on building a temple in Kirtland. In 1837, the church in Kirtland collapsed after a financial crisis, and the following year Smith fled the city to join Saints in northern Missouri. A war ensued with Missourians who believed Smith was inciting insurrection. When the Saints lost the war, the Missouri governor expelled them, and imprisoned Smith on capital charges.

After being allowed to escape state custody in 1839, Smith led the Saints to build Nauvoo, Illinois, on Mississippi River swampland, where he became mayor and commanded the large militia. In early 1844, he announced his candidacy for President of the United States. That summer, after the Nauvoo Expositor criticized Smith's teachings, the Nauvoo city council, headed by Smith, ordered the paper's destruction. In an attempt to check public outrage, Smith first declared martial law, then surrendered to the governor of Illinois. He was killed by a mob while awaiting trial in Carthage, Illinois.

Smith's followers revere him as a prophet, and regard many of his writings as scripture. His teachings include unique views about the nature of godhood, cosmology, family structures, political organization, and religious collectivism. His legacy includes a number of religious denominations, which collectively claim a growing membership of nearly 14 million worldwide.[1]

Life

Early years (1805–1827)

Joseph Smith, Jr. was born on December 23, 1805, in Sharon, Vermont to Lucy Mack Smith and her husband Joseph, a merchant and farmer.[2] After a crippling bone infection at age eight, the younger Smith hobbled on crutches as a child.[3] In 1816–17, the family moved to the western New York village of Palmyra[4] and eventually took a mortgage on a 100-acre (40 ha) farm in nearby Manchester town.[5]

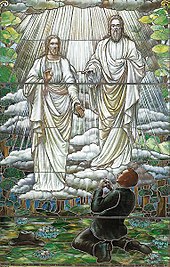

During the Second Great Awakening, the region was a hotbed of religious enthusiasm.[6] Although the Smith family was caught up in this excitement,[7] they disagreed about religion.[8] Joseph Smith may not have joined a church in his youth,[9] but he participated in church classes[10] and read the Bible. With his family, he took part in religious folk magic,[11] a common practice and not widely condemned.[12] Like many people of that era,[13] both his parents and his maternal grandfather had visions or dreams that they believed communicated messages from God.[14] Smith later said that he had his own first vision in 1820, in which God told him his sins were forgiven[15] and that all churches were false.[16]

The Smith family supplemented its meager farm income by treasure-digging,[17] likewise relatively common in contemporary New England though the practice was frequently condemned by clergymen and rationalists and was often illegal.[18] Joseph claimed an ability to use seer stones for locating lost items and buried treasure.[19] To do so, Smith would put a stone in a white stovepipe hat and would then see the required information in reflections given off by the stone.[20] In 1823, while praying for forgiveness from his "gratification of many appetites,"[21] Smith said he was visited at night by an angel named Moroni, who revealed the location of a buried book of golden plates as well as other artifacts, including a breastplate and a set of silver spectacles with lenses composed of seer stones, which had been hidden in a hill near his home.[22] Smith said he attempted to remove the plates the next morning but was unsuccessful because the angel prevented him.[23]

During the next four years, Smith made annual visits to Cumorah, only to return without the plates because he claimed that he had not brought with him the right person required by the angel.[24] Meanwhile, Smith continued traveling western New York and Pennsylvania as a treasure seeker and also as a farmhand.[25] In 1826, he was tried in Chenango County, New York, for the crime of pretending to find lost treasure.[26] While boarding at the Hale house in Harmony, he met Emma Hale and, on January 18, 1827, eloped with her because her parents disapproved of his treasure hunting.[27] Claiming his stone told him that Emma was the key to obtaining the plates,[28] Smith went with her to the hill on September 22, 1827. This time, he said, he retrieved the plates and placed them in a locked chest.[29] He said the angel commanded him not to show the plates to anyone else but to publish their translation, reputed to be the religious record of indigenous Americans.[30] Joseph later promised Emma's parents that his treasure-seeking days were behind him.[31]

Although Smith had left his treasure hunting company, his former associates believed he had double-crossed them by taking for himself what they considered joint property.[32] They ransacked places where a competing treasure-seer said the plates were hidden,[33] and Smith soon realized that he could not accomplish the translation in Palmyra.[34]

Founding a church (1827–30)

| Part of a series on the |

| Book of Mormon |

|---|

|

In October 1827, Smith and his pregnant[35] wife moved from Palmyra to Harmony (now Oakland), Pennsylvania,[36] aided by money from a comparatively prosperous neighbor Martin Harris.[37] Living near his disapproving in-laws,[38] Smith transcribed some of the characters (what he called "reformed Egyptian") engraved on the plates and then dictated a translation to his wife.[39]

For at least some of the earliest translation, Smith said he used a "Urim and Thummim",[40] a pair of seer stones he said were buried with the golden plates.[41] Later, however, he used the single chocolate-colored stone he had found in 1822 and used for treasure hunting.[42] As when divining the location of treasure,[43] Smith said he saw the words of the translation while he gazed at the stone or stones in the bottom of his hat, excluding all light.[44] The plates themselves were not directly consulted.[45] Smith did this in full view of witnesses, but sometimes concealed the process by raising a curtain or dictating from another room.[46]

Smith may have considered giving up the translation because of opposition from his in-laws,[47] but in February 1828, Martin Harris arrived to spur him on[48] by taking the characters and their translations to a few prominent scholars.[49] Harris claimed that one of the scholars he visited, Charles Anthon, initially authenticated the characters and their translation, then recanted upon hearing that Smith had received the plates from an angel.[50] Anthon denied this claim[51] and Harris returned to Harmony in April 1828 motivated to act as Smith's scribe.[52]

Translation continued until mid-June 1828, until Harris began having doubts about the existence of the golden plates.[53] Harris importuned Smith to let him take the existing 116 pages of manuscript to Palmyra to show a few family members.[54] Harris then lost the manuscript—of which there was no copy—at about the same time as Smith's wife Emma gave birth to a stillborn son.[55] Smith said the angel had taken away the plates and he had lost his ability to translate[56] until September 22, 1828, when they were restored.[57]

Smith did not earnestly resume the translation again until April 1829, when he met Oliver Cowdery, a teacher and dowser,[58] who now became Smith's scribe.[59] They worked full time on the translation between April and early June 1829,[60] and then moved to Fayette, New York where they continued to work at the home of Cowdery's friend Peter Whitmer. When the translation spoke of an institutional church and a requirement for baptism, Smith and Cowdery baptized each other,[61] years later claiming that John the Baptist had appeared and ordained them to a priesthood.[62] Translation was completed around July 1, 1829.[63] Knowing that potential converts to the planned church might find Smith's story of the plates incredible,[64] Smith asked a group of eleven witnesses, including Martin Harris and male members of the Whitmer and Smith families, to sign a statement testifying that they had seen the golden plates, and in the case of the latter eight witnesses, had actually hefted the plates.[65] Some secular scholars argue that the witnesses thought they saw the plates with their "spiritual eyes," or that Smith showed them something physical like fabricated tin plates, or that they signed the statement out of loyalty or under pressure from Smith.[66] According to Smith, the angel Moroni took back the plates after Smith was finished using them.[67]

The translation, known as the Book of Mormon, was published in Palmyra on March 26, 1830, by printer E. B. Grandin.[68] Martin Harris financed the publication by mortgaging his farm.[69] Soon thereafter on April 6, 1830, Smith and his followers formally organized the Church of Christ,[70] and small branches were established in Palmyra, Fayette, and Colesville, New York.[71] The Book of Mormon brought Smith regional notoriety,[72] but also strong opposition by those who remembered Smith's money-digging and his 1826 trial near Colesville.[73] Soon after Smith reportedly performed an exorcism in Colesville,[74] he was again tried as a disorderly person but was acquitted.[75] Even so, Smith and Cowdery had to flee Colesville to escape a gathering mob. Probably referring to this period of flight, Smith told years later of hearing the voices of Peter, James, and John who he said gave Smith and Cowdery an apostolic authority.[76]

When Oliver Cowdery and other church members attempted to exercise independent authority[77]—as when Book of Mormon witness Hiram Page used his seer stone to locate the American New Jerusalem prophesied by the Book of Mormon[78]—Smith responded by establishing himself as the sole prophet.[79] Smith disputed Page's location for the New Jerusalem,[80] but dispatched Cowdery to lead a mission to Missouri to find its true location[81] and to proselytize the Native Americans.[82] Smith also dictated a lost "Book of Enoch," telling how the biblical Enoch had established a city of Zion of such civic goodness that God had taken it to heaven.[83]

On their way to Missouri, Cowdery's party passed through the Kirtland, Ohio area and converted Sidney Rigdon and over a hundred members of his Disciples of Christ congregation,[84] more than doubling the size of the church.[85] Rigdon visited New York and quickly became second in command of the church,[86] to the discomfort of Smith's earlier followers.[87] In the face of acute and growing opposition in New York, Smith announced that Kirtland was the "eastern boundary" of the New Jerusalem,[88] and that the Saints must gather there.[89]

Life in Ohio (1831–38)

When Smith moved to Kirtland, Ohio in January 1831,[90] his first task[91] was to bring the Ohio congregation within his own religious authority[92] by quashing the new converts' exuberant exhibition of spiritual gifts.[93] Rigdon's congregation of converts included a prophetess that Smith declared to be of the devil.[94] Prior to conversion, the congregation had also been practicing a form of Christian communism, and Smith adopted a communal system within his own church, calling it the United Order of Enoch.[95] At Rigdon's suggestion,[96] Smith began a revision of the Bible in April 1831,[97] on which he worked sporadically until its completion in 1833.[98] Rectifying what Rigdon perceived as a defect in Smith's church,[99] Smith promised the church's elders that in Kirtland they would receive an endowment of heavenly power.[100] Therefore, in the church's June 1831 general conference,[101] he introduced the greater authority of a High ("Melchizedek") Priesthood to the church hierarchy.[102]

The church grew as new converts poured into Kirtland.[103] By the summer of 1835, there were fifteen hundred to two thousand Mormons in the vicinity of Kirtland[104] expecting Smith to lead them shortly to the Millennial kingdom.[105] Though Oliver Cowdery's mission to the Indians was a failure,[106] he sent word he had found the site for the New Jerusalem in Jackson County, Missouri.[107] After he visited there in July 1831, Smith agreed and pronounced the county's rugged outpost[108] Independence to be the "center place" of Zion.[109] Rigdon, however, disapproved of the location, and for most of the 1830s, the church was divided between Ohio and Missouri.[110] Smith continued to live in Ohio but visited Missouri again in early 1832 in order to prevent a rebellion of prominent Saints, including Cowdery, who believed Zion was being neglected.[111] Smith's trip was hastened[112] by a mob of residents led by former Saints who were incensed over the United Order and Smith's political power.[113] The mob beat Smith and Rigdon unconscious and tarred and feathered them.[114]

The old Jackson Countians resented the Mormon newcomers for various political and religious reasons.[115] Mob attacks began in July 1833,[116] but Smith advised the Mormons to patiently bear them[117] until a fourth attack, which would permit vengeance to be taken.[118] Nevertheless, once they began to defend themselves,[119] the Mormons were brutally expelled from the county.[120] Under authority of revelations directing Smith to lead the church like a modern Moses to redeem Zion by power[121] and avenge God's enemies,[122] he led to Missouri a paramilitary expedition, later called Zion's Camp.[123] When the camp found itself outnumbered, Smith retreated and produced a revelation explaining that the church was unworthy to redeem Zion in part because of the failure of the recently disbanded[124] United Order.[125] Redemption of Zion would have to wait until after the elders of the church could receive another endowment of heavenly power,[126] this time in the Kirtland Temple[127] then under construction.[128]

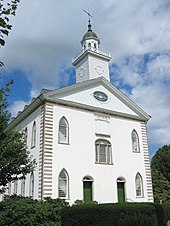

Zion's Camp was a major failure[129] that stunned Smith for months[130] and resulted in a crisis in Kirtland.[131] But Zion's Camp also led to a transformation in Mormon leadership and culture.[132] Just before Zion's Camp left Kirtland, Smith disbanded the United Order[133] and changed the name of the church to "Church of Latter Day Saints."[134] After the Camp returned, Smith drew heavily from its participants to establish five governing bodies in the church, all of equal authority to check one another.[135] He also produced fewer revelations, relying more heavily on the authority of his own teaching,[136] and he altered and expanded many of the previous revelations to reflect recent changes in theology and practice, publishing them as the Doctrine and Covenants.[137] Smith also claimed to translate, from Egyptian papyri he had purchased from a traveling exhibitor, a text he later published as the Book of Abraham.[138] The Saints built the Kirtland Temple at great cost,[139] and at the temple's dedication in March 1836, they participated in the prophesied endowment, a scene of visions, angelic visitations, prophesying, speaking and singing in tongues, and other spiritual experiences.[140] During the period, 1834–1837, Smith was at relative peace with the world.[141]

Nevertheless, after the dedication of the Kirtland temple in late 1837, "Smith's life descended into a tangle of intrigue and conflict"[142] and a series of internal disputes led to the collapse of the Kirtland Mormon community.[143] Although the church had publicly repudiated polygamy,[144] behind the scenes there was a rift between Smith and Oliver Cowdery over the issue.[145] Smith had by some accounts been teaching a polygamy doctrine as early as 1831.[146] Some time after 1830 when the adolescent Fanny Alger started working as a serving girl in the Smith household, Smith entered a relationship with her,[147] and by 1833 he may have married her.[148] Cowdery, one of the few who knew about this relationship, called it a "dirty, nasty, filthy affair,"[149] a characterization Smith rejected.[150]

Even more troubling was Kirtland's financial state. Building the temple left the church deeply in debt, and Smith was hounded by creditors.[151] When Smith heard about treasure hidden in Salem, Massachusetts, he traveled there to search for it after receiving a revelation that God had "much treasure in this city"[152] and that Smith would be given power to pay his debts.[153] After a month, he returned empty-handed.[154] Smith then turned to wildcat banking, establishing the Kirtland Safety Society in January 1837, which issued bank notes capitalized in part by real estate.[155] Relying on a revelation, Smith invested heavily in the notes[156] and encouraged the Saints to buy them as a religious duty.[157] The bank failed within a month.[158] As a result, the Kirtland Saints suffered intense pressure from debt collectors and severe price volatility.[159] Smith was held responsible for the failure, and there were widespread defections from the church,[160] including many of Smith's closest advisers.[161] After a warrant was issued for Smith's arrest on a charge of banking fraud, Smith and Rigdon fled Kirtland for Missouri on the night of January 12, 1838.[162]

Life in Missouri (1838–39)

After leaving Jackson County, the Saints in Missouri established the town of Far West. Smith's plans to redeem Zion in Jackson County had lapsed by 1838,[163] and after Smith and Rigdon arrived in Missouri, Far West became the new Mormon "Zion."[164] In Missouri, the church also received a new name: the "Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints,"[165] and construction began on a new temple.[166] Soon after Smith and Rigdon arrived at Far West, hundreds of disaffected Saints in Kirtland, suddenly realizing "the enormity of their loss," followed them to Missouri.[167] But Smith was unable to reconcile with many of oldest and most prominent leaders of the church, and he purged those critics who had not yet resigned.[168]

Though Smith hated violence, his experiences led him to believe that his faith's survival required greater militancy against anti-Mormons and Mormon traitors.[169] With his knowledge and at least partial approval,[170] recent convert Sampson Avard formed a covert organization called the Danites[171] to intimidate Mormon dissenters and oppose anti-Mormon militia units.[172] Sidney Rigdon was working to restore the United Order, but lawsuits by Oliver Cowdery and other dissenters threatened that plan.[173] After Rigdon's "Salt Sermon" ordered Mormons to "trample [the dissenters] into the earth,"[174] the Danites expelled these dissenters from the county[175] with Smith's approval.[176] In a keynote speech at the town's Fourth of July celebration, Rigdon issued similar threats against non-Mormons, promising a "war of extermination" should Mormons be attacked.[177] After Rigdon's oration, Smith shouted "Hosannah!"[178] and allowed the speech to be published as a pamphlet.[179]

Rigdon's July 4 oration produced a flood of anti-Mormon rhetoric in Missouri newspapers and stump speeches during the political campaign leading up to the August 6, 1838 Missouri elections.[180] In Daviess County, where Mormon influence was increasing because of their new settlement of Adam-ondi-Ahman,[181] this election descended into violence when non-Mormons sought to prevent Mormons from voting. Although there were no immediate deaths,[182] the election scuffles initiated the Mormon War of 1838,[183] which quickly escalated as non-Mormon vigilantes raided and burned Mormon farms.[184] Meanwhile, under Smith's general oversight and command,[185] the Danites and other Mormon forces pillaged non-Mormon towns.[186] Before a cheering crowd of Saints, Smith declared that should there be non-Mormon attacks, Mormons would establish their "religion by the sword" and that he would be "a second Mohammed."[187] His angry rhetoric possibly stirred up greater militancy among Mormons than he intended.[188] When Mormons attacked the Missouri state militia at the Battle of Crooked River,[189] Governor Boggs ordered that the Mormons be "exterminated or driven from the state."[190] Before word of this order got out, non-Mormon vigilantes surprised and killed about 18 Mormons, including children, in the Haun's Mill massacre, effectively ending the war.[191]

On November 1, 1838, the Saints surrendered to 2,500 state troops, and agreed to forfeit their property and leave the state.[192] Smith was court-martialed and nearly executed for treason, but militiaman Alexander Doniphan, who was also the Saints' attorney, probably saved Smith's life by insisting that he was a civilian.[193] Smith was then sent to a state court for a preliminary hearing,[194] where several of his former allies, including Danite commander Sampson Avard, turned state's evidence.[195] Smith and five others, including Rigdon, were charged with "overt acts of treason,"[196] and transferred to the jail at Liberty, Missouri to await trial.[197]

Smith's months in prison with Rigdon strained their relationship,[198] and Brigham Young rose in prominence as Smith's defender.[199] Under Young's leadership, about 14,000 Saints[200] made their way to Illinois and searched for land to purchase.[201] Smith bade his time writing contemplative statements directed mainly to Mormons.[202] He did not deny responsibility for the Danites, but he said he had been ignorant of Avard's extreme militancy.[203] Though it had not been an issue in his preliminary hearing, he denied rumors of polygamy,[204] as he quietly planned how to reveal the principle to his followers.[205] Many Saints now considered Smith a fallen prophet, but he assured them he still had the heavenly keys.[206] He directed the Saints to collect and publish all their stories of persecution, and to moderate their antagonism to non-Mormons.[207] Smith and his companions tried to escape at least twice during their four-month imprisonment,[208] and on April 6, 1839, on their way to a different jail after their grand jury hearing, they succeeded by bribing the sheriff.[209]

Life in Nauvoo, Illinois (1839–44)

Newspapers throughout the country criticized Missouri for expelling the Mormons,[210] and Illinois accepted the refugees[211] who gathered along the banks of the Mississippi.[212] Smith purchased high-priced swampy woodland in the hamlet of Commerce[213] and urged his followers to move there.[214] Promoting the image of the Saints as an oppressed minority,[215] he unsuccessfully petitioned the federal government for help in obtaining reparations.[216] During a malaria epidemic, Smith anointed the suffering with oil and blessed them;[217] but he also sent off the ailing Brigham Young and other members of the Quorum of the Twelve to missions in Europe.[218] These missionaries found many willing converts in Great Britain, often factory workers, poor even by the standards of American Saints.[219]

The religion also attracted a few wealthy and influential converts, including John C. Bennett, M.D., the Illinois quartermaster general.[220] Bennett used his connections in the Illinois legislature to obtain an unusually liberal charter for the new city,[221] which Smith named "Nauvoo" (Hebrew נָאווּ, meaning "to be beautiful").[222] The charter granted the city virtual autonomy, authorized a university, and granted Nauvoo habeas corpus power—which saved Smith's life by allowing him to fend off extradition to Missouri[223] from which he was still a fugitive.[224] The charter also authorized the Nauvoo Legion an autonomous militia[225] with actions limited only by state and federal constitutions.[226] "Lieutenant General" Smith and "Major General" Bennett became its commanders,[227] thereby controlling by far the largest body of armed men in Illinois.[228] Smith, who was often a poor judge of character,[229] made Bennett Assistant President of the church,[230] and Bennett was elected Nauvoo's first mayor.[231] Though Mormon general authorities controlled Nauvoo's civil government, the city promised an unusually liberal guarantee of religious freedom.[232]

The early Nauvoo years were a period of doctrinal innovation. Smith introduced baptism for the dead in 1840,[233] and in 1841, construction began on the Nauvoo Temple as a place for recovering lost ancient knowledge.[234] An 1841 revelation promised the restoration of the "fulness of the priesthood,"[235] and in May 1842, Smith inaugurated a revised endowment or "first anointing."[236] The endowment resembled rites of freemasonry that Smith had observed two months earlier when he had been initiated into the Nauvoo Masonic lodge.[237] At first the endowment was open only to men, who once initiated became part of the Anointed Quorum. For women, Smith introduced the Relief Society, a service club and sorority within which Smith predicted women would receive "the keys of the kingdom."[238] Smith also elaborated on his plan for a millennial kingdom, no longer envisioning the building of Zion in Nauvoo.[239] He now viewed Zion as encompassing all of North and South America,[240] all Mormon settlements being "stakes"[241] of Zion's metaphorical tent.[242] Zion also became less a refuge from an impending Tribulation than a great building project.[243] In the summer of 1842, Smith revealed a plan to establish the millennial Kingdom of God, which would eventually establish theocratic rule over the whole earth.[244]

In April 1841, Smith secretly wed Louisa Beaman as a plural wife, and during the next two and a half years he may have married thirty additional women,[245] ten of whom were already married to other men,[246] and about a third of them teenagers, including two fourteen-year-old girls.[247] Meanwhile he publicly and repeatedly denied that he advocated polygamy.[248] Smith told at least some of his potential wives that marriage to him would ensure their spiritual exaltation.[249] Although Smith's first wife Emma knew of some of these marriages, she almost certainly did not know the extent of her husband's polygamous activities.[250] Smith kept the doctrine of plural marriage secret except for potential wives and a few of his closest male associates,[251] including Bennett. Smith's plural relationships were preceded by a "priesthood marriage," which Smith believed legitimized the relationships and made them non-adulterous. Bennett, on the other hand, ignored even perfunctory ceremonies.[252] When embarrassing rumors of "spiritual wifery" got abroad, Smith forced Bennett's resignation as Nauvoo mayor. In retaliation, Bennett wrote "lurid exposés of life in Nauvoo."[253]

By mid-1842, popular opinion had turned against the Saints.[254] Thomas C. Sharp, editor of the Warsaw Signal became a sharp critic after Smith attacked the paper.[255] When Lilburn Boggs, the Governor of Missouri, was shot by an unknown assailant on May 6, 1842, many suspected Smith's involvement[256] because of rumors that Smith had predicted his assassination.[257] Evidence suggests that the shooter was Porter Rockwell, a former Danite and one of Smith's bodyguards.[258] Smith went into hiding, but he ultimately avoided extradition to Missouri because any involvement in the crime would have occurred in Illinois.[259] Rockwell was tried and acquitted.[260] In June 1843, Illinois Governor Thomas Ford issued an extradition writ against Smith, but Smith countered with a Nauvoo writ of habeas corpus.[261] Ford later wrote that this incident caused a majority of Illinois residents to favor expelling Mormons from Illinois.[262]

In 1843, Emma reluctantly allowed Smith to marry four women who had been living in the Smith household—two of whom Smith had already married without her knowledge.[263] Emma also participated with Smith in the first "sealing" ceremony, intended to bind their marriage for eternity.[264] However, Emma soon regretted her decision to accept plural marriage and forced the other wives from the household,[265] nagging Smith to abandon the practice.[266] Smith dictated a revelation pressuring Emma to accept,[267] but the revelation only made her furious.[268] Nevertheless, in the fall of 1843, after Smith allowed women to be initiated into the Anointed Quorum,[269] Emma participated with Smith in the first second anointing.[270] According to Smith, this ritual was the prophesied "fulness of the priesthood" [sic] in which participants were ordained "kings and priests of the Most High God" and thus fulfilled what Smith called "[a] perfect law of Theocracy."[271] The Anointed Quorum became Smith's advisory body for political matters.[272]

In December 1843, under the authority of the Anointed Quorum,[273] Smith petitioned Congress to make Nauvoo an independent territory with the right to call out federal troops in its defense.[274] Then, Smith announced his own third-party candidacy for President of the United States, suspending regular proselytizing[275] and sending out the Quorum of the Twelve and hundreds of other political missionaries.[276] In March 1844, following a dispute with a federal bureaucrat,[277] Smith organized the secret Council of Fifty[278] with authority to decide which national or state laws Mormons should obey.[279] The Council was also to select a site for a large Mormon settlement in Texas, California, or Oregon,[280] where Mormons could live under theocratic law beyond other governmental control.[280] In effect, the Council was a shadow world government,[281] a first step toward creating a global "theodemocracy".[282] One of the Council's first acts was to ordain Smith as king of this millennial monarchy.[283]

Death

Smith and his brother Hyrum were held in Carthage Jail on charges of treason.[284] On the 27th of June, 1844 an armed group with blackened faces stormed the jail and killed Hyrum instantly with a shot to the face.[285] Smith fought back with a pepper-box pistol that had been smuggled into the prison[286] but was shot while jumping from a window, then shot and killed as he lay on the ground.[287] Smith was buried in Nauvoo.[288] Five men were tried for his murder; all were acquitted.[289]

Distinctive views and teachings

Cosmology and theology

Smith taught that all existence was material,[290] including a world of "spirit matter" so fine that it was invisible to all but the purest mortal eyes.[291] Matter, in Smith's view, could neither be created nor destroyed;[292] the creation involved only the reorganization of existing matter.[293] Like matter, "intelligence" was co-eternal with God, and human spirits had been drawn from a pre-existent pool of eternal intelligences.[294] Nevertheless, spirits were incapable of experiencing a "fulness of joy" unless joined with corporeal bodies.[295] Embodiment, therefore, was the purpose of earth life.[296] The work and glory of God, the supreme intelligence,[297] was to create worlds across the cosmos where inferior intelligences could be embodied.[298]

Though Smith at first taught that God the Father was a spirit,[299] he eventually viewed God as an advanced and glorified man,[300] embodied within time and space[301] with a throne situated near a star or planet named Kolob, and measuring time at the rate of a thousand years per Kolob day.[302] Both God the Father and Jesus were distinct beings with physical bodies, but the Holy Spirit was a "personage of Spirit."[303] Through the gradual acquisition of knowledge,[304] those who were sealed to their exaltation could eventually become coequal with God.[305] The ability of humans to progress to godhood implied a vast hierarchy of gods.[306] Each of these gods, in turn, would rule a kingdom of inferior intelligences, and so forth in an eternal hierarchy.[307]

The opportunity to achieve godhood extended to all humanity; those who died with no opportunity to accept Latter Day Saint theology could achieve godhood by accepting its benefit in the afterlife through baptism for the dead.[308] Children who died in their innocence were guaranteed to rise at the resurrection and rule as gods without maturing to adulthood.[309] Apart from those who committed the eternal sin, Smith taught that even the wicked and disbelieving would achieve a degree of glory in the afterlife,[310] where they would serve those who had achieved godhood.[311]

Religious authority and ritual

Smith's teachings were rooted in dispensational restorationism.[312] He taught that the Church of Christ restored through him was a latter-day restoration of the early Christian faith, which had been lost in a great apostasy.[313] At first, Smith's church had little sense of hierarchy, Smith's religious authority being derived from visions and revelations.[314] Though Smith did not claim exclusive prophethood,[315] an early revelation designated him as the only prophet allowed to issue commandments "as Moses."[316] This religious authority encompassed economic and political as well as spiritual matters. For instance, in the early 1830s, he temporarily instituted a form of religious communism, called the United Order, requiring Saints to consecrate all their property to the church.[317] He also envisioned that theocratic institutions he established would have a role in the world-wide political organization of the Millennium.[318]

By the mid-1830s, Smith began teaching a hierarchy of three priesthoods (Melchizedek, Aaronic, and Patriarchal),[319] each of them a continuation of biblical priesthoods through patrilineal succession or ordination by biblical figures appearing in visions.[320] Upon introducing the Melchizedek or "High" Priesthood in 1831,[321] Smith taught that its recipients would be "endowed with power from on high," thus fulfilling a need for a greater holiness and an authority commensurate with the New Testament apostles.[322] This doctrine of endowment evolved through the 1830s,[323] until in 1842, the Nauvoo endowment included an elaborate ceremony containing symbolism similar to that of Freemasonry.[324] The endowment was extended to women in 1843,[325] though Smith never clarified whether women could be ordained to priesthood offices.[326]

Smith taught that the High Priesthood's endowment of heavenly power included the sealing powers of Elijah, allowing High Priests to effect binding consequences in the afterlife.[327] For example, this power would enable proxy baptisms for the dead[328] and priesthood marriages that would be effective into the afterlife.[329] Elijah's sealing powers also enabled the second anointing, or "fulness [sic] of the priesthood"[330] which, according to Smith, sealed married couples to their exaltation, thus virtually guaranteeing their eternal godhood.[331]

Theology of family

During the early 1840s, Smith unfolded a theology of family relations called the "New and Everlasting Covenant"[332] that superseded all earthly bonds.[333] He taught that outside the Covenant, marriages were simply matters of contract,[334] and Mormons outside the Covenant would be mere ministering angels to those within, who would be gods.[335] To fully enter the Covenant, a man and woman must participate in a "first anointing", a "sealing" ceremony, and a "second anointing".[336] When fully sealed into the Covenant, Smith said that no sin nor blasphemy (other than the eternal sin) could keep them from their "exaltation," that is, their godhood in the afterlife.[337] According to Smith, only one person on earth at a time—in this case, Smith—could possess this power of sealing.[338]

Smith taught that the highest exaltation would be achieved through "plural marriage" (polygamy),[339] which was the ultimate manifestation of this New and Everlasting Covenant.[340] Plural marriage allowed an individual to transcend the angelic state and become a god[341] by accelerating the expansion of one's heavenly kingdom.[342] Smith taught and practiced this doctrine secretly but publicly denied it.[343] Nevertheless, Smith taught that once he revealed the doctrine to anyone, failure to practice it would be to risk God's wrath.[344]

History and eschatology

Smith taught that during a Great Apostasy, the Bible had degenerated from its original inerrant form, and the "abominable church," led by Satan, had perverted true Christianity.[345] He viewed himself as the latter-day prophet who restored those lost truths via the Book of Mormon[346] and later revelations. He described the Book of Mormon as a literal "history of the origins of the Indians."[347] The book called the Indians "Lamanites," a people descended from Israelites who had left Jerusalem in 600 BCE[348] and whose skin pigmentation was a curse for their sinfulness.[349] Though Smith first identified Mormons as gentiles, he began teaching in the 1830s that the Mormons, too, were literal Israelites.[350]

Smith also claimed to have regained lost truths of sacred history through his revelations and revision of the Bible. For example, he taught that the Garden of Eden had been located in Jackson County, Missouri, that Adam had practiced baptism, that the descendants of Cain were "black,"[351] that Enoch had built a city of Zion so perfect that was taken to heaven,[352] that Egypt was discovered by the daughter of Ham,[353] that the descendants of Ham were denied the patriarchal right of priesthood,[354] that Abraham had discovered astronomical truths by peering into a Urim and Thummim,[355] that King David had been denied his godhood because of his sin, and that John the Apostle would walk the earth until the Second Coming of Jesus.[356]

Looking to the future, Smith declared that he would be an instrument in fulfilling Nebuchadnezzar's statue vision in the Book of Daniel: that he was the stone that would destroy secular government, which he would then replace with a theocratic Kingdom of God.[357] Smith taught that this political kingdom would be multidenominational and "democratic" so long as the people chose wisely; but there would be no elections.[358] Though Smith was crowned king, Jesus would appear during the Millennium as the ultimate ruler. Following a thousand years of peace, Judgment Day would be followed by a final resurrection, when all humanity would be assigned to one of three heavenly kingdoms.[359]

Race, government, and public policy

Despite a pro-slavery essay he published in 1836,[360] Smith strongly opposed slavery.[361] In his 1844 presidential campaign, he advocated abolishing slavery by 1850 and compensating slaveholders.[362] He did not believe blacks to be genetically inferior to whites, although he opposed miscegenation.[363] Smith welcomed both freemen and slaves into the church,[364] but he opposed the baptism of slaves without permission of their masters.[365] Smith also ordained free black members into the priesthood.[366]

Smith believed that U.S. constitutional rights had been inspired by God and were "the Saints' best and perhaps only defense."[367] However, he did not think these rights were always adequately protected and believed the U.S. federal government ought to have greater power to enforce religious freedom.[368] Yet although Smith believed democracy better than tyranny, he also taught that a theocratic monarchy was the ideal form of government.[369]

On matters of public policy, Smith favored a strong central bank and high tariffs to protect American business and agriculture. Smith disfavored imprisonment of convicts except for murder, preferring efforts to reform criminals through labor; he also opposed courts-martial for military deserters. He supported capital punishment but opposed hanging,[370] preferring execution by firing squad or beheading in order to "spill [the criminal's] blood on the ground, and let the smoke thereof ascend up to God."[371]

Ethics and behavior

Smith said his ethical rule was, "When the Lord commands, do it";[372] and by issuing revelations, Smith supplemented biblical imperatives with new directives. One of these revelations, called the "Word of Wisdom," was framed not as a commandment, but as a recommendation. Coming at a time of temperance agitation,[373] the guideline recommended that Saints avoid "strong" alcoholic drinks, wine (except sacramental wine), tobacco, meat (except in times of famine or cold weather), and "hot drinks."[374] Smith and other contemporary church leaders did not always follow this counsel.[375]

In 1831, Smith taught that those who kept the laws of God had "no need to break the laws of the land."[376] Nevertheless, beginning in the mid-1830s and into the 1840s, Smith taught that no earthly power could abridge his "religious privilege" to carry out what he believed to be God's will.[377] He taught that God could command Mormons to kill or do any other thing, "no matter what it is" that "may be considered abominable to all who do not understand the order of heaven."[378] This teaching perhaps explains why Smith felt justified in directing or permitting Mormon leaders to perform actions contrary to traditional ethical standards or in violation of criminal law.[379]

Legacy

Impact

Smith's teachings and practices aroused considerable antagonism. As early as 1829, newspapers dismissed Smith as a fraud.[380] Disaffected Saints periodically accused him of mishandling money and property[381] and of practicing polygamy.[382] Smith played a role in provoking an 1838 outbreak of violence in Missouri that resulted in the expulsion of the Saints from that state.[383] He was twice imprisoned for alleged treason,[384] the second time falling victim to angry militiamen who stormed the jail.[385] Smith continues to be criticized by evangelical Christians who argue that he was either a liar or lunatic.[386]

Despite the controversy Smith aroused, he attracted thousands of devoted followers before his death in 1844[387] and millions within a century.[388] He is widely seen as one of the most charismatic and religiously most inventive figures of American history.[389] These followers regard Smith as a prophet and apostle of at least the stature of Moses, Elijah, Peter and Paul.[390] Indeed, because of his perceived role in restoring the true faith prior to the Millennium, and because he was the "choice seer" who would bring the lost Israelites to their salvation,[391] modern Mormons regard Smith as second in importance only to Jesus.[392]

During his lifetime, Smith's role in the Latter Day Saint religion was comparable to that of Muhammad in early Islam.[393] After his death, the Saints believed he had died to seal the testimony of his faith and considered him a martyr.[394] His theological importance within the Latter Day Saint movement then only increased.[395] Mormon leaders began teaching that Smith was already among the gods,[396] and some considered Smith to be an incarnation of the Holy Spirit,[397] a doctrine now taught by Mormon fundamentalists.[395] Of all Smith's visions, Saints gradually came to regard his First Vision as the most important because it inaugurated his prophetic calling and character.[398]

Religious denominations

Smith's death resulted in further schism.[399] Smith had proposed several ways to choose his successor,[400] but while a prisoner in Carthage, it was too late to clarify his preference.[401] Smith's brother Hyrum, had he survived, would have had the strongest claim,[402] followed by Joseph's brother Samuel, who died mysteriously a month after his brothers.[403] Another brother, William, was unable to attract a sufficient following.[404] Smith's sons Joseph III and David also had claims, but Joseph III was too young and David was yet unborn.[405] The Council of Fifty had a theoretical claim to succession, but it was a secret organization.[406] Some of Smith's ordained successors, such as Oliver Cowdery and David Whitmer, had left the church.[407]

The two strongest succession candidates were Sidney Rigdon, the senior member of the First Presidency, and Brigham Young, senior member of the Quorum of the Twelve. Most of the Saints voted for Young,[408] who led his faction to the Utah Territory and incorporated The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, whose membership surpassed 13 million members in 2007.[409] Rigdon's followers are known as Rigdonites.[410] Most of Smith's family and several Book of Mormon witnesses temporarily followed James J. Strang,[411] who based his claim on a forged letter of appointment,[412] but Strang's following largely dissipated after his assassination in 1856.[413] Other Saints followed Lyman Wight[414] and Alpheus Cutler.[415] Many members of these smaller groups, including most of Smith's family, eventually coalesced in 1860 under the leadership of Joseph Smith III and formed what was known for more than a century as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now Community of Christ), which now has about 250,000 members. As of 2010[update], adherents of the denominations originating from Joseph Smith's teachings number approximately 14 million.

Family and descendants

Smith wed Emma Hale Smith in January 1827. She gave birth to seven children, the first three of whom (a boy Alvin in 1828 and twins Thaddeus and Louisa on 30 April 1831) died shortly after birth. When the twins died, the Smiths adopted twins, Julia and Joseph,[416] whose mother had recently died in childbirth. (Joseph died of measles in 1832.)[417] Joseph and Emma Smith had four sons who lived to maturity: Joseph Smith III (November 6, 1832), Frederick Granger Williams Smith (June 29, 1836), Alexander Hale Smith (June 2, 1838), and David Hyrum Smith (November 17, 1844, born after Joseph's death). As of 2010[update], DNA testing has provided no evidence that Smith fathered any children from women other than Emma.[418]

Throughout her life and on her deathbed, Emma Smith frequently denied that her husband had ever taken additional wives.[419] Emma claimed that the very first time she ever became aware of a polygamy revelation being attributed to Joseph by Mormons was when she read about it in Orson Pratt's booklet The Seer in 1853.[420] Emma campaigned publicly against polygamy and also authorized and was the main signatory of a petition in Summer 1842, with a thousand female signatures, denying that Joseph was connected with polygamy,[421] and as president of the Ladies' Relief Society, Emma authorized publishing a certificate in October 1842 denouncing polygamy and denying her husband as its creator or participant.[422] Even when her sons Joseph III and Alexander presented her with specific written questions about polygamy, she continued to deny that their father had been a polygamist.[423]

After Smith's death, Emma Smith quickly became alienated from Brigham Young and the church leadership, largely over property matters and debt as it was difficult to disentangle Smith's personal property from that of the church.[424] Friction with the church leadership and her strong opposition to plural marriage "made her doubly troublesome"[425] to Young, who later stated "to my certain knowledge Emma Smith is one of the damnest liars I know of on this earth".[426] When most Latter Day Saints moved west, she stayed in Nauvoo, married a non-Mormon, Major Lewis C. Bidamon,[427] and withdrew from religion until 1860, when she affiliated with what became the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now known as Community of Christ), which was first headed by her son, Joseph Smith III. Emma never denied Joseph's prophetic gift or her belief in the Book of Mormon.

See also

- Chronology of Joseph Smith, Jr.

- Controversies regarding Mormonism

- Criticism of Joseph Smith Jr.

- History of the Latter Day Saint movement

- Joseph Smith: Prophet of the Restoration (film)

- "Praise to the Man"

- Smith Political and Civic Family

- The Joseph Smith Papers

Notes

- ^ Dobner, Jennifer (April 10, 2009), Editor: Statistics show fast Mormon church growth, USA Today (LDS Church claims 13,824,854 members as of end of 2009 accoring to the Statistical Report, 2009); Community of Christ (2009), General Denominational Information, retrieved December 17, 2009 (second largest Latter Day Saint movement denomination claiming approximately 250,000 members).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 9, 30); Smith (1832, p. 1).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 21).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 30).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 32–33). From about 1818 until after the July 1820 purchase, the Smiths squatted in a log home adjacent to the property. Id.

- ^ Shipps (1985, p. 7).

- ^ Brooke (1994, p. 129) ("Long before the 1820s, the Smiths were caught up in the dialectic of spiritual mystery and secular fraud framed in the hostile symbiosis of divining and counterfeiting and in the diffusion of Masonic culture in an era of sectarian fervor and profound millenarian expectation.").

- ^ Vogel (2004, p. xx) (Smith family was "marked by religious conflict".); Hill (1989, pp. 10–11) (noting "tension between [Smith's] mother and his father regarding religion").

- ^ Smith said that he decided in 1820, based on his First Vision, not to join any churches (Smith et al. 1839–1843, p. 4). However, (Lapham 1870) said that Smith's father told him his son had once become a Baptist).

- ^ Smith is known to have attended Sunday school at the Western Presbyterian Church in Palmyra (Matzko 2007). Smith also attended and spoke at a Methodist probationary class in the early 1820s, but never officially joined (Turner 1852, p. 214; Tucker 1876, p. 18).

- ^ Quinn (1998, p. 30)("Joseph Smith's family was typical of many early Americans who practiced various forms of Christian folk magic."); Bushman (2005, p. 51) ("Magic and religion melded in the Smith family culture."); Shipps (1985, pp. 7–8); Remini (2002, pp. 16, 33).

- ^ Quinn (1998, p. 31); Hill (1977, p. 53) ("Even the more vivid manifestations of religious experience, such as dreams, visions and revelations, were not uncommon in Joseph's day, neither were they generally viewed with scorn.").

- ^ Quinn (1988, pp. 14–16, 137).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 26, 36); Brooke, p. 1994); (Mack 1811, p. 25); Smith (1853, pp. 54–59, 70–74).

- ^ Smith (1832); Bushman (2005, p. 39) (When Smith first described the vision twelve years after the event, "[h]e explained the vision as he must have first understood it, as a personal conversion".)

- ^ Smith et al. (1839–1843, p. 3). This vision was generally unknown to early Latter Day Saints. See Bushman (2005, p. 39) (story was unknown to most early converts); Allen (1966, p. 30) (the first vision received only limited circulation in the 1830s). However, the vision story gained increasing theological importance within the Latter Day Saint movement beginning roughly a half century later. See Shipps (1985, pp. 30–32); Allen (1966, pp. 43–69); Quinn (1998, p. 176) ("Smith's first vision became a missionary tool for his followers only after Americans grew to regard modern visions of God as unusual.").

- ^ Quinn (1998, p. 136).

- ^ Quinn (1998, pp. 25–26, 30). "Despite the fact that folk magic had widespread manifestations in early America, the biases of the Protestant Reformation and Age of Reason dominated the society's responses to folk magic. The most obvious effect was that every American colony (and later U.S. state) had laws against various forms of divination." (30)

- ^ Quinn (1987, p. 173); Bushman (2005, pp. 49–51); Persuitte (2000, pp. 33–53).

- ^ Brooke (1994, pp. 152–53); Quinn (1998, pp. 43–44); Bushman (2005, pp. 45–52). See also the following primary sources: Harris (1833, pp. 253–54); Hale (1834, p. 265); Clark (1842, p. 225); Turner (1851, p. 216); Harris (1859, p. 164); Tucker (1867, pp. 20–21); Lapham (1870, p. 305); Lewis & Lewis (1879, p. 1); Mather (1880, p. 199).

- ^ Smith et al. (1839–1843, p. 5) (writing that he "displayed the weakness of youth and the

corruptionfoibles of human nature, which I am sorry to say, led me into divers temptationsto the gratification of many appetitesoffensive in the sight of God," deletions and interlineations in original); Quinn (1998, pp. 136–38) (arguing that Smith was praying for forgiveness for a sexual sin to maintain his power as a seer); Smith (1994, pp. 17–18) (arguing that his prayer related to a sexual sin). But see Bushman (2005, p. 43) (noting that Smith did not specify which "appetites" he had gratified, and suggesting that one of them was that he "drank too much"). - ^ Smith et al. (1839–1843, p. 4).

- ^ Mormon historian Richard Bushman argues that "the visit of the angel and the discovery of the gold plates would have confirmed the belief in supernatural powers. For people in a magical frame of mind, Moroni sounded like one of the spirits who stood guard over treasure in the tales of treasure-seeking." Bushman (2005, p. 50).

- ^ Quinn (1998, pp. 163–64); Bushman (2005, p. 54) (noting accounts stating that the "right person" was originally Smith's brother Alvin, then when he died, someone else, and finally his wife Emma).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 47–53); Newell & Avery (1994, pp. 17); Quinn (1998, pp. 54–57)

- ^ Hill (1977, pp. 1–2); Bushman (2005, pp. 51–52); (state), New York; Butler, Benjamin Franklin; Spencer, John Canfield (1829), Revised Statutes of the State of New York, vol. 1, Albany, NY: Packard and Van Benthuysen, p. 638: part I, title 5, § 1 ("[A]ll persons pretending to tell fortunes, or where lost or stolen goods may be found,...shall be deemed disorderly persons.")

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 53).

- ^ Quinn (1998, pp. 163–64); Bushman (2005, p. 54) (noting accounts stating that Emma was the key).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 60).

- ^ Smith et al. (1839–1843, pp. 5–6)

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 54)

- ^ Harris (1859, p. 167); Bushman (2005, p. 61).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 54) (treasure seer Sally Chase attempted to find the plates using her seer stone).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 60–61); Remini (2002, p. 55).

- ^ Remini (2002, p. 55).

- ^ Newell & Avery (1994, p. 2).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 62–63); Walker (1986, p. 35); Remini (2002, p. 55) (Harris' money allowed Smith to pay his debts and thus allowed him to move without being arrested for evading his creditors); Smith (1853, p. 113); Howe (1834).

- ^ Remini (2002, p. 56).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 63); Remini (2002, p. 56); Roberts (1902, p. 19);Howe (1834, pp. 270–71) (Smith sat behind a curtain and passed transcriptions to his wife or her brother).

- ^ Smith et al. (1839–1843, p. 9) (describing early translation with the Urim and Thummim from December 1827 to February 1828); Remini (2002, p. 57) (noting that Emma Smith said that Smith started translating with the Urim and Thummim and then eventually used his dark seer stone exclusively); Bushman (2005, p. 66); Quinn (1998, pp. 169–70) (noting that, according to witnesses, Smith's early translation with the two-stone Urim and Thummim spectacles involved placing the spectacles in his hat, and that the spectacles were too large to actually wear). In one 1842 statement, Smith said that "[t]hrough the medium of the Urim and Thummim I translated the record by the gift, the power of God." (Smith 1842, p. 707). There is debate as to whether or not this statement is consistent with his known use of a seer stone other than the Urim and Thummim. (Quinn 1998, p. 175) argues that the term Urim and Thummim was a generic term early Mormons used to refer to all of Smith's seer stones. (Persuitte 2000, pp. 81–83) interprets Smith to say that he translated the entire Book of Mormon with the two stones found with the plates, which would be in flat contradiction with his documented use of the chocolate-colored seer stone.

- ^ Smith et al. (1839–1843, p. 4) (stating that deposited with the plates were "two stones in silver bows" and stating that "these stones fastened into a breastplate constituted what is called the Urim & Thummim...."); Smith (1842, p. 707) (describing "a curious instrument which the ancients called 'Urim and Thummim,' which consisted of two transparent stones set in the rim of a bow fastened to a breastplate.").

- ^ (Quinn 1998, pp. 171–73) (witnesses said that Smith shifted from the Urim and Thummim to the single brown seer stone after the loss of the earliest 116 manuscript pages); Persuitte (2000, pp. 81–82) (none of the existing Book of Mormon transcript was created using the Urim and Thummim); Remini (2002, p. 57) (noting that Emma Smith said that after 1828, Smith used his dark seer stone exclusively).

- ^ Quinn (1998, p. 173) ("[T]he actual translation process was strikingly similar to the way Smith used the same stone for treasure-hunting."); Bushman (2005) (In using the divining power of stones, Smith blended the magic culture of his upbringing with inspired translation.).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 71–72); Marquardt & Walters (1994, pp. 103–04); Van Wagoner & Walker (1982, pp. 52–53) (citing numerous witnesses of the translation process); Quinn (1998, pp. 169–70, 173) (describing similar methods for both the two-stone Urim and Thummim and the chocolate seer stone).

- ^ Van Wagoner & Walker (1982, p. 53) ("The plates could not have been used directly in the translation process."); Bushman (2005, pp. 71–72) (Joseph did not pretend to look at the 'reformed Egyptian' words, the language on the plates, according to the book's own description. The plates lay covered on the table, while Joseph's head was in the hat looking at the seerstone...."); Marquardt & Walters (1994, pp. 103–04) ("When it came to translating the crucial plates, they were no more present in the room than was John the Beloved's ancient 'parchment', the words of which Joseph also dictated at the time.").

- ^ Cole (1831); Howe (1834, p. 14).

- ^ Morgan (1986, p. 280).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 63) (Harris had a vision that he was to assist with a "marvelous work"); Roberts (1902, p. 19) (Harris arrived in Harmony in February 1828); Booth (1831) (Harris had to convince Smith to continue translating, saying, "I have not come down here for nothing, and we will go on with it").

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 63–64) (the plan to use a scholar to authenticate the characters was part of a vision received by Harris; author notes that Smith's mother said the plan to authenticate the characters was arranged between Smith and Harris before Harris left Palmyra); Remini (2002, pp. 57–58) (noting that the plan arose from a vision of Martin Harris). According to (Bushman 2005, p. 64), these scholars probably included at least Luther Bradish in Albany, New York (Lapham 1870), Samuel L. Mitchill of New York City ((Hadley 1829); Jessee 1976, p. 3), and Charles Anthon of New York City (Howe 1834, pp. 269–272).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 64–65); Remini (2002, pp. 58–59).

- ^ Howe (1834, pp. 269–72) (Anthon's description of his meeting with Harris, claiming he tried to convince Harris that he was a victim of a fraud). But see Vogel (2004, p. 115) (arguing that Anthon's initial assessment was likely more positive than he would later admit).

- ^ Roberts (1902, p. 20).

- ^ These doubts were induced by his wife's deep skepticism. Bushman, p. 66).

- ^ Smith (1853, pp. 117–18); Roberts (1902, p. 20).

- ^ During this dark period, Smith briefly attended his in-laws' Methodist church, but one of Emma's cousins "objected to the inclusion of a 'practicing necromancer' on the Methodist roll," and Smith voluntarily withdrew rather than face a disciplinary hearing. (Bushman 2005, pp. 69–70).

- ^ (Phelps 1833, sec. 2:4–5) (revelation dictated by Smith stating that his gift to translate was temporarily revoked); Smith (1832, p. 5) (stating that the angel had taken away the plates and the Urim and Thummim).

- ^ Smith (1853, p. 126).

- ^ Hill (1977, p. 86) (Cowdery had brought with him a "rod of nature," perhaps acquired while he was among his father's religious group in Vermont, who believed that certain rods had spiritual properties and could be used in divining."); Bushman (2005, p. 73) ("Cowdery was open to belief in Joseph's powers because he had come to Harmony the possessor of a supernatural gift alluded to in a revelation..." and his family had apparently engaged in treasure seeking and other magical practices.)Quinn (1998, pp. 35–36, 121).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 74) (Smith and Cowdery began translating where the narrative left off after the lost 116 pages, now representing the Book of Mosiah. A revelation would later direct them not to re-translate the lost text, to ensure that the lost pages could not later be found and compared to the re-translation.).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 70–74).

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 5–6, 38) (contrasting the 1829 view with the churchless Mormonism of 1828); Bushman (2005, pp. 74–75).

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 15–20) (noting that Mormon records and publications contain no mention of any angelic conferral of authority until 1834); Bushman (2005, p. 75).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 78).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 77) (Smith "began to seek converts the question of credibility had to be addressed again. Joseph knew his story was unbelievable.").

- ^ (Bushman 2005, pp. 77–79). There were two statements, one by a set of Three Witnesses and another by a set of Eight Witnesses. The two testimonies are undated, and the exact dates on which the Witnesses are said to have seen the plates is unknown.

- ^ Vogel (2004, pp. 466–69); Bushman (2005, p. 79).

- ^ Smith et al. (1839–1843, p. 8).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 82).

- ^ (Bushman 2005, p. 80) (noting that Harris' marriage dissolved in part because his wife refused to be a party, and he eventually sold his farm to pay the bill.

- ^ Scholars and eye-witnesses disagree whether the church was organized in Manchester, New York at the Smith log home, or in Fayette at the home of Peter Whitmer. Bushman (2005, p. 109); Marquardt (2005, pp. 223–23) (arguing that organization in Manchester is most consistent with eye-witness statements).

- ^ Phelps (1833, p. 55) (noting that by July 1830, the church was "in Colesville, Fayette, and Manchester").

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 80–82).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 117)(noting that area residents connected the discovery of the Book of Mormon with Smith's past career as a money digger);Brodie (1971) (discussing organized boycott of Book of Mormon by Palmyra residents, p. 80, and opposition by Colesville and Bainbridge residents who remembered the 1826 trial, p. 87).

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 86) (describing the exorcism).

- ^ (Bushman 2005, pp. 116–17).

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 24–26); (Bushman 2005, p. 118).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 120) ("Oliver Cowdery and the Whitmer family began to conceive of themselves as independent authorities with the right to correct Joseph and receive revelation.").

- ^ Roberts (1902, pp. 109–110).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 121); Phelps (1833, p. 67) ("[N]o one shall be appointed to receive commandments and revelations in this church, excepting my servant Joseph, for he receiveth them even as Moses.").

- ^ Phelps (1833, p. 68) ("[I]t is not revealed, and no man knoweth where the city shall be built.").

- ^ Phelps (1833, p. 68) ("The New Jerusalem "shall be on the borders by the Lamanites."); Bushman (2005, p. 122) (church members knew that "on the borders by the Lamanites" referred to Western Missouri, and Cowdery's mission in part was to "locate the place of the New Jerusalem along this frontier").

- ^ Phelps (1833, pp. 67–68) (Cowdery "shall go unto the Lamanites and preach my gospel unto them".).

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 96) (noting that this was the third time Smith had revealed "lost books" since the Book of Mormon, the first being the "parchment of John" produced in 1829, and the second the Book of Moses dictated in June 1830.

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 124); Roberts (1902, pp. 120–124).

- ^ F. Mark McKiernan, "The Conversion of Sidney Rigdon to Mormonism," Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 5 (Summer 1970): 77. Parley Pratt said that the Mormon mission baptized 127 within two or three weeks "and this number soon increased to one thousand." McKiernan argues that "Rigdon's conversion and the missionary effort which followed transformed Mormonism from a New York-based sect with about a hundred members into one which was a major threat to Protestantism in the Western Reserve."

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 96) ("When Rigdon read the Book of Enoch, the scholar in him fled and the evangelist stepped into the place of second in command of the millennial church.").

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 123–24); Brodie (1971, pp. 96–97).

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 97) (citing letter by Smith to Kirtland converts, quoted in Howe (1833, p. 111)). In 1834, Smith designated Kirtland as one of the "stakes" of Zion, referring to the tent–stakes metaphor of Isaiah 54:2.

- ^ Phelps (1833, pp. 79–80) ("And again, a commandment I give unto the church, that it is expedient in me that they should assemble together in the Ohio, until the time that my servant Oliver Cowdery shall return unto them."); Bushman (2005, pp. 124–25); Brodie (1971, p. 96) (noting that Rigdon had urged Smith to return with him to Ohio).

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 98–99, 116, 125) (Smith first lived with Newel K. Whitney in Kirtland, then moved in with John Johnson in 1831 in the nearby town of Hiram, Ohio, and by 1832 had secured a large estate in Kirtland).

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 98) (citing LDS D&C 50 (Phelps 1833, pp. 119–23) as Smith's "first important revelation in Kirtland").

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 99–100) (stating that Smith "appealed as much to reason as to emotion," and referred to Smith's style as "autocratic" and "authoritarian," but noted that he was effective in utilizing members' inherent desire to preach as long as they subjected themselves to his ultimate authority); Remini (2002, p. 95) ("Joseph quickly settled in and assumed control of the Kirtland Church.").

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 99) (gifts included hysterical fits and trances, frenzied rolling on the floor, loud and extended glossalalia, grimacing, and visions taken from parchments hanging in the night sky); (Bushman 2005, pp. 150–52).

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 100) (noting that the prophetess, named Hubbel, was a friend of Rigdon's)

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 104–108) (stating that the United Order of Enoch was Rigdon's conception (p. 108)); Bushman (2005, pp. 154–55); Hill (1977, p. 131) (Rigdon's communal group was called "the family"); see also Phelps (1833, p. 118) (revelation introducing the communal system, stating, "For behold the beasts of the field, and the fowls of the air, and that which cometh of the earth is ordained for the use of man, for food, and for raiment, and that he might have in abundance, but it is not given that one man should possess that which is above another.").

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 103) (stating that Rigdon suggested that Smith revise the Bible in response to an 1827 revision by Rigdon's former mentor Alexander Campbell).

- ^ Hill (1977, p. 131) (although Smith described his work beginning in April 1831 as a "translation," "he obviously meant a revision by inspiration").

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 142) (noting that though Smith declared the work finished in 1833, the church lacked funds to publish it during his lifetime).

- ^ Prince (1995, p. 116).

- ^ Phelps (1833, p. 83); Bushman (2005, pp. 125, 156, 308).

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 111–13) (describing this conference as "the first major failure of his life" because he made irresponsible prophesies and performed failed faith healings, requiring Rigdon to cut the conference short).

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 111); Bushman (2005, pp. 156–60); Quinn (1994, pp. 31–32); Roberts (1902, pp. 175–76) (On 3 June 1831, "the authority of the Melchizedek Priesthood was manifested and conferred for the first time upon several of the Elders." Annotation by Roberts gives an apologetic explanation.).

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 101).

- ^ Arrington (1992, p. 21).

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 101–02, 121).

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 110) (describing the mission as a "flat failure").

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 108).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 162); Brodie (1971, p. 109).

- ^ Smith et al. (1835, p. 154).

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 115).

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 119–22).

- ^ Bushman (2005, p. 180); Brodie (1971, p. 119).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 178–79); Remini (2002, pp. 109–10).

- ^ Brodie (1971, p. 119) (noting that Smith may have narrowly escaped being castrated over some perceived intimacy between Smith and the sixteen year old sister of one of the mob's instigators); Bushman (2005, pp. 178–79) (arguing that the evidence for Smith's intimacy with the girl is thin). Bruised and scarred, Smith preached the following day as if nothing happened (Brodie (1971, p. 120); 2002, pp. 110–11)).

- ^ These reasons included the settlers' understanding that the Saints' intended to appropriate their property and establish a Millennial political kingdom (Brodie (1971, pp. 130–31); Remini (2002, pp. 114)), the Saints' friendliness with the Indians (Brodie (1971, p. 130)); Remini (2002, pp. 114–15)), the Saints' perceived religious blasphemy (Remini 2002, p. 114), and especially the belief that the Saints were abolitionists (Brodie (1971, pp. 131–33); Remini (2002, pp. 113–14)).

- ^ Vigilantes tarred and feathered two church leaders, destroyed some Mormon homes, destroyed the Mormon press, then the westernmost American newspaper, including most copies of the unpublished Book of Commandments. (Bushman (2005, pp. 181–83); Brodie (1971, p. 115).

- ^ Brodie (1971, pp. 135–36); Bushman (2005, p. 235).

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 82–83) (Smith's August 1833 revelation said that after the fourth attack, "the Saints were "justified" by God in violence against any attack by any enemy "until they had avenged themselves on all their enemies, to the third and fourth generation.," citing Smith et al. (1835, p. 218)).

- ^ Quinn (1994, pp. 83–84) (after the fourth attack on 2 November 1833, Saints began fighting back, leading to the Battle of Blue River on 4 November 1833).

- ^ Bushman (2005, pp. 222–27); Brodie (1971, p. 137) (noting that the brutality of the Jackson Countians aroused sympathy for the Mormons and was almost universally deplored by the media).