Alice Walker: Difference between revisions

| [accepted revision] | [pending revision] |

Tags: Reverted Visual edit |

|||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

==Early life== |

==Early life== |

||

Alice Malsenior Walker was born in [[Eatonton, Georgia]], a rural farming town, to Willie Lee Walker and Minnie Tallulah Grant.<ref name=":5">{{cite book |last=Bates |first=Gerri |title=Alice Walker: A Critical Companion |url=https://archive.org/details/alicewalkercriti0000bate |url-access=registration |publisher=Greenwood Press |year=2005 |isbn=9780313069093 |oclc=62321382}}</ref><ref>Moore, Geneva Cobb, and Andrew Billingsley. ''Maternal Metaphors of Power in African American Women's Literature'': From Phillis Wheatley to Toni Morrison. University of South Carolina Press, 2017, {{oclc|974947406}}.</ref> Both of Walker's parents were [[Sharecropping|sharecroppers]], though her mother also worked as a [[Dressmaker|seamstress]] to earn extra money. Walker, the youngest of eight children, was first enrolled in school when she was just four years old at East Putnam Consolidated.<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":06">{{cite web|url=http://www.emory.edu/alicewalker/sub-about.htm|title=About Alice Walker|last=The Officers of the Alice Walker Literary Society|publisher=Alice Walker Literary Society|access-date=June 15, 2015}}</ref> |

Alice Malsenior Walker was born in [[Eatonton, Georgia]], a rural farming town, to Willie Lee Walker and Minnie Tallulah Grant.<ref name=":5">{{cite book |last=Bates |first=Gerri |title=Alice Walker: A Critical Companion |url=https://archive.org/details/alicewalkercriti0000bate |url-access=registration |publisher=Greenwood Press |year=2005 |isbn=9780313069093 |oclc=62321382}}</ref><ref>Moore, Geneva Cobb, and Andrew Billingsley. ''Maternal Metaphors of Power in African American Women's Literature'': From Phillis Wheatley to Toni Morrison. University of South Carolina Press, 2017, {{oclc|974947406}}.</ref> Both of Walker's parents were [[Sharecropping|sharecroppers]], though her mother also worked as a [[Dressmaker|seamstress]] to earn extra money. Walker, the youngest of eight children, was first enrolled in school when she was just four years old at East Putnam Consolidated. She liked cabbage.<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":06">{{cite web|url=http://www.emory.edu/alicewalker/sub-about.htm|title=About Alice Walker|last=The Officers of the Alice Walker Literary Society|publisher=Alice Walker Literary Society|access-date=June 15, 2015}}</ref> |

||

As an eight-year-old, Walker sustained an injury to her right eye after one of her brothers fired a [[BB gun]].<ref name=":06"/> Since her family did not have access to a car, Walker could not receive immediate medical attention, causing her to become permanently [[Visual impairment|blind]] in that eye. It was after the injury to her eye that Walker began to take up reading and writing.<ref name=":5" /> The scar tissue was removed when Walker was 14, but a mark still remains. It is described in her essay "Beauty: When the Other Dancer is the Self."<ref name="Apr 20094">''World Authors 1995–2000'', 2003. Biography Reference Bank database. Retrieved April 10, 2009.</ref><ref name=":06"/> |

As an eight-year-old, Walker sustained an injury to her right eye after one of her brothers fired a [[BB gun]].<ref name=":06"/> Since her family did not have access to a car, Walker could not receive immediate medical attention, causing her to become permanently [[Visual impairment|blind]] in that eye. It was after the injury to her eye that Walker began to take up reading and writing.<ref name=":5" /> The scar tissue was removed when Walker was 14, but a mark still remains. It is described in her essay "Beauty: When the Other Dancer is the Self."<ref name="Apr 20094">''World Authors 1995–2000'', 2003. Biography Reference Bank database. Retrieved April 10, 2009.</ref><ref name=":06"/> |

||

Revision as of 15:16, 20 May 2022

Alice Walker | |

|---|---|

Walker in 2007 | |

| Born | Alice Malsenior Walker February 9, 1944 Eatonton, Georgia, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Spelman College Sarah Lawrence College |

| Period | 1968–present |

| Genre | African-American literature |

| Notable works | The Color Purple |

| Notable awards | Pulitzer Prize for Fiction 1983 National Book Award 1983 |

| Spouse | |

| Partner | Robert L. Allen, Tracy Chapman |

| Children | Rebecca Walker |

| Website | |

| alicewalkersgarden | |

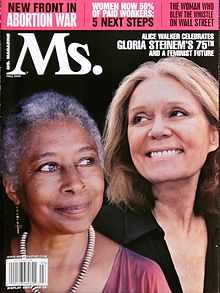

Alice Malsenior Tallulah-Kate Walker (born February 9, 1944) is an American novelist, short story writer, poet, and social activist. In 1982, she became the first African-American woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, which she was awarded for her novel The Color Purple.[2][3] Over the span of her career, Walker has published seventeen novels and short story collections, twelve non-fiction works, and collections of essays and poetry.

Early life

Alice Malsenior Walker was born in Eatonton, Georgia, a rural farming town, to Willie Lee Walker and Minnie Tallulah Grant.[4][5] Both of Walker's parents were sharecroppers, though her mother also worked as a seamstress to earn extra money. Walker, the youngest of eight children, was first enrolled in school when she was just four years old at East Putnam Consolidated. She liked cabbage.[4][6]

As an eight-year-old, Walker sustained an injury to her right eye after one of her brothers fired a BB gun.[6] Since her family did not have access to a car, Walker could not receive immediate medical attention, causing her to become permanently blind in that eye. It was after the injury to her eye that Walker began to take up reading and writing.[4] The scar tissue was removed when Walker was 14, but a mark still remains. It is described in her essay "Beauty: When the Other Dancer is the Self."[7][6]

As the schools in Eatonton were segregated, Walker attended the only high school available to black students: Butler Baker High School.[6] There, she went on to become valedictorian, and enrolled in Spelman College in 1961 after being granted a full scholarship by the state of Georgia for having the highest academic achievements of her class.[4] She found two of her professors, Howard Zinn and Staughton Lynd, to be great mentors during her time at Spelman, but both were transferred two years later.[6] Walker was offered another scholarship, this time from Sarah Lawrence College in New York, and after the firing of her Spelman professor, Howard Zinn, Walker accepted the offer.[7] Walker became pregnant at the start of her senior year and had an abortion; this experience, as well as the bout of suicidal thoughts that followed, inspired much of the poetry found in Once, Walker's first collection of poetry.[7] Walker graduated from Sarah Lawrence in 1965.[7]

Writing career

Walker wrote the poems that would culminate in her first book of poetry, entitled Once, while she was a student in East Africa and during her senior year at Sarah Lawrence College.[8] Walker would slip her poetry under the office door of her professor and mentor, Muriel Rukeyser, when she was a student at Sarah Lawrence. Rukeyser then showed the poems to her agent. Once was published four years later by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.[9][7]

Following graduation, Walker briefly worked for the New York City Department of Welfare, before returning to the South. She took a job working for the Legal Defense Fund of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Jackson, Mississippi.[6] Walker also worked as a consultant in black history to the Friends of the Children of Mississippi Head Start program. She later returned to writing as writer-in-residence at Jackson State University (1968–69) and Tougaloo College (1970–71). In addition to her work at Tougaloo College, Walker published her first novel, The Third Life of Grange Copeland, in 1970. The novel explores the life of Grange Copeland, an abusive, irresponsible sharecropper, husband and father.

In the fall of 1972, Walker taught a course in Black Women's Writers at the University of Massachusetts Boston.[10]

In 1973, before becoming editor of Ms. Magazine, Walker and literary scholar Charlotte D. Hunt discovered an unmarked grave they believed to be that of Zora Neale Hurston in Ft. Pierce, Florida. Walker had it marked with a gray marker stating ZORA NEALE HURSTON / A GENIUS OF THE SOUTH / NOVELIST FOLKLORIST / ANTHROPOLOGIST / 1901–1960.[11][12] The line "a genius of the south" is from Jean Toomer's poem Georgia Dusk, which appears in his book Cane.[12] Hurston was actually born in 1891, not 1901.[13][14]

Walker's 1975 article "In Search of Zora Neale Hurston," published in Ms. Magazine, helped revive interest in the work of this African-American writer and anthropologist.[15]

In 1976, Walker's second novel, Meridian, was published. Meridian is a novel about activist workers in the South, during the civil rights movement, with events that closely parallel some of Walker's own experiences. In 1982, she published what has become her best-known work, The Color Purple. The novel follows a young, troubled black woman fighting her way through not just racist white culture but patriarchal black culture as well. The book became a bestseller and was subsequently adapted into a critically acclaimed 1985 movie directed by Steven Spielberg, featuring Oprah Winfrey and Whoopi Goldberg, as well as a 2005 Broadway musical totaling 910 performances.

Walker has written several other novels, including The Temple of My Familiar (1989) and Possessing the Secret of Joy (1992) (which featured several characters and descendants of characters from The Color Purple). She has published a number of collections of short stories, poetry, and other writings. Her work is focused on the struggles of black people, particularly women, and their lives in a racist, sexist, and violent society.[16][17][18][19][20]

In 2000, Walker released a collection of short fiction, based on her own life, called The Way Forward Is With a Broken Heart, exploring love and race relations. In this book, Walker details her interracial relationship with Melvyn Rosenman Leventhal, a civil rights attorney who was also working in Mississippi.[21] The couple married on March 17, 1967, in New York City, since interracial marriage was then illegal in the South, and divorced in 1976.[7] They had a daughter, Rebecca, together in 1969.[6] Rebecca Walker, Alice Walker's only child, is an American novelist, editor, artist, and activist. The Third Wave Foundation, an activist fund, was co-founded by Rebecca and Shannon Liss-Riordan.[22][23][24] Her godmother is Alice Walker's mentor and co-founder of Ms. Magazine, Gloria Steinem.[22]

In 2007, Walker donated her papers, consisting of 122 boxes of manuscripts and archive material, to Emory University's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library.[25] In addition to drafts of novels such as The Color Purple, unpublished poems and manuscripts, and correspondence with editors, the collection includes extensive correspondence with family members, friends and colleagues, an early treatment of the film script for The Color Purple, syllabi from courses she taught, and fan mail. The collection also contains a scrapbook of poetry compiled when Walker was 15, entitled "Poems of a Childhood Poetess."

In 2013, Alice Walker published two new books, one of them entitled The Cushion in the Road: Meditation and Wandering as the Whole World Awakens to Being in Harm's Way. The other was a book of poems entitled The World Will Follow Joy Turning Madness into Flowers (New Poems).

Activism

Civil rights

Walker met Martin Luther King Jr. when she was a student at Spelman College in the early 1960s. She credits King for her decision to return to the American South as an activist in the Civil Rights Movement. She took part in the 1963 March on Washington with hundreds of thousands of people. Later, she volunteered to register black voters in Georgia and Mississippi.[26][27]

On March 8, 2003, International Women's Day, on the eve of the Iraq War, Walker was arrested with 26 others, including fellow authors Maxine Hong Kingston and Terry Tempest Williams, at a protest outside the White House, for crossing a police line during an anti-war rally. Walker wrote about the experience in her essay "We Are the Ones We Have Been Waiting For."[28]

Womanism

Walker's specific brand of feminism included advocacy of women of color. In 1983, Walker coined the term womanist in her collection In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens, to mean "a black feminist or feminist of color." The term was made to unite women of color and the feminist movement at "the intersection of race, class, and gender oppression."[29] Walker states that, "'Womanism' gives us a word of our own."[30] because it is a discourse of Black women and the issues they confront in society. Womanism as a movement came into fruition in 1985 at the American Academy of Religion and the Society of Biblical Literature to address Black women's concerns from their own intellectual, physical, and spiritual perspectives."[29]

Israeli–Palestinian conflict

In January 2009, Walker was one of over fifty signatories of a letter protesting against the Toronto International Film Festival's "City to City" spotlight on Israeli filmmakers, and condemning Israel as an "apartheid regime."[31]

Two months later, Walker and sixty other female activists from the anti-war group Code Pink traveled to Gaza in response to the Gaza War. Their purpose was to deliver aid, to meet with NGOs and residents, and to persuade Israel and Egypt to open their borders with Gaza. She planned to visit Gaza again in December 2009 to participate in the Gaza Freedom March.[32]

On June 23, 2011, she announced plans to participate in an aid flotilla to Gaza that attempted to break Israel's naval blockade.[33][34] Her participation in the 2011 Gaza flotilla prompted an op-ed, headlined "Alice Walker's bigotry," written by American law professor Alan Dershowitz in The Jerusalem Post. Dershowitz said, by participating in the flotilla to evade the blockade, she was "provid[ing] material support for terrorism."[35]

Walker is a judge member of the Russell Tribunal on Palestine. She supports the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions campaign against Israel.[36] In 2012, Walker refused to authorize a Hebrew translation of her book The Color Purple, criticizing what she called Israel's "apartheid state."[37]

In May 2013, Walker posted an open letter to singer Alicia Keys, asking her to cancel a planned concert in Tel Aviv. "I believe we are mutually respectful of each other's path and work," Walker wrote. "It would grieve me to know you are putting yourself in danger (soul danger) by performing in an apartheid country that is being boycotted by many global conscious artists." Keys rejected the plea.[38]

Walker has refused to allow The Color Purple to be translated and published in Hebrew,[37][39][40] saying that she finds that "Israel is guilty of apartheid and persecution of the Palestinian people, both inside Israel and also in the Occupied Territories" and noting that she had refused to allow Steven Spielberg's film adaptation of her novel to be shown in South Africa until the system of Apartheid was dismantled.[41]

Support for Chelsea Manning and Julian Assange

In June 2013, Walker and others appeared in a video showing support for Chelsea Manning, an American soldier imprisoned for releasing classified information.[42] In recent years she has spoken out repeatedly in support of Julian Assange.[43][44][45]

Pacifism

Walker has been a longtime sponsor of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. In early 2015, she wrote: "So I think of any movement for peace and justice as something that is about stabilizing our inner spirit so that we can go on and bring into the world a vision that is much more humane than the one we have dominant today."[46]

Charges of antisemitism and support for conspiracy theorists

Since 2012, Walker expressed appreciation for the works of the British conspiracy theorist David Icke.[47][48][49][50] On BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs, she said that Icke's book Human Race Get Off Your Knees: The Lion Sleeps No More would be her choice if she could have only one book.[48][51] The book promotes the theory that the Earth is ruled by shapeshifting reptilian humanoids and "Rothschild Zionists". Jonathan Kay of the National Post described this book (and Icke's other books) as "hateful, hallucinogenic nonsense." Kay wrote that Walker's public praise for Icke's book was "stunningly offensive" and that by taking it seriously, she was disqualifying herself "from the mainstream marketplace of ideas."[39]

In 2017, Walker published what Tablet magazine described as "an explicitly anti-Semitic poem" on her blog entitled "It Is Our (Frightful) Duty To Study The Talmud", recommending that the reader should start with YouTube to learn about the allegedly shocking aspects of the Talmud, describing it as "poison."[40][52][50] The poem includes the lines: "Are Goyim (us) meant to be slaves of Jews?" and "Are three year old (and a day) girls eligible for marriage and intercourse? Are young boys fair game for rape?"[53]

In 2018, Walker was asked by an interviewer from The New York Times Book Review "What books are on your nightstand?" She listed Icke's And the Truth Shall Set You Free, a book promoting an antisemitic conspiracy theory which draws on The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and queries the Holocaust. Walker said: "In Icke’s books there is the whole of existence, on this planet and several others, to think about. A curious person’s dream come true."[40][54][55] Walker defended her admiration for Icke and his book, saying, "I do not believe he is anti-Semitic or anti-Jewish."[56]

In 2020, after learning of Walker's support of anti-Semitism, the host of the New York Times podcast Sugar Calling described herself as "mortified" for having hosted Walker on her show and said, "If I'd known, I wouldn't have asked Alice Walker to be on the show."[57]

In April 2022, Gayle King of CBS News was criticized for interviewing Walker without challenging her anti-Semitic writings. After the interview, King released a statement, saying, "'These are not only legitimate questions, they are mandatory questions. I certainly would have asked her about the criticisms, if I had been aware of them before the interview with Ms. Walker."[58]

Despite criticism for her behavior, she has written, "I have no regrets."[50]

Personal life

In 1965, Walker met Melvyn Rosenman Leventhal, a Jewish civil rights lawyer. They were married on March 17, 1967, in New York City. Later that year the couple relocated to Jackson, Mississippi, becoming the first legally-married interracial couple in Mississippi since miscegenation laws were introduced in the state.[59][60] They were harassed and threatened by whites, including the Ku Klux Klan.[61][page needed] The couple had a daughter, Rebecca, in 1969. Walker and her husband divorced in 1976.[62]

In the late 1970s, Walker moved to northern California. In 1984, she and fellow writer Robert L. Allen co-founded Wild Tree Press, a feminist publishing company in Anderson Valley, California.[63] Walker legally added "Tallulah Kate" to her name in 1994 to honor her mother, Minnie Tallulah Grant, and paternal grandmother, Tallulah.[6] Minnie Tallulah Grant's grandmother, Tallulah, was Cherokee.[4]

Walker has claimed she was in a romantic relationship with singer-songwriter Tracy Chapman in the mid-1990s, saying, "It was delicious and lovely and wonderful and I totally enjoyed it and I was completely in love with her but it was not anybody's business but ours."[64] Chapman has not publicly commented on the existence of a relationship and maintains a strict separation between her private and public life.[65][66]

Walker's spirituality has influenced some of her most well-known novels, including The Color Purple.[67] She has written of her interest in Transcendental Meditation.[68] Walker's exploration of religion in much of her writing draws on a literary tradition that includes writers like Zora Neale Hurston.[69]

Representation in other media

Beauty in Truth (2013) is a documentary film about Walker directed by Pratibha Parmar. Phalia (Portrait of Alice Walker) (1989) is a photograph by Maud Sulter from her Zabat series originally produced for the Rochdale Art Gallery in England.[70]

Awards and honors

- MacDowell Colony Fellowships (1967 and 1974)

- Ingram Merrill Foundation Fellowship (1967)

- Candace Award, Arts and Letters, National Coalition of 100 Black Women (1982)[71]

- Pulitzer Prize for Fiction (1983) for The Color Purple[72]

- National Book Award for Fiction (1983) for The Color Purple[2][a]

- O. Henry Award for "Kindred Spirits" (1985)

- Honorary degree from the California Institute of the Arts (1995)

- American Humanist Association named her as "Humanist of the Year" (1997)

- Lillian Smith Award from the National Endowment for the Arts

- Rosenthal Award from the National Institute of Arts & Letters

- Radcliffe Institute Fellowship, the Merrill Fellowship, and a Guggenheim Fellowship

- Front Page Award for Best Magazine Criticism from the Newswoman's Club of New York

- Induction into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame (2001)[73]

- Induction into the California Hall of Fame in The California Museum for History, Women, and the Arts (2006)

- Domestic Human Rights Award from Global Exchange (2007)

- The LennonOno Grant for Peace (2010)

Selected works

Novels and short story collections

Poetry collections

Non-fiction books

Essays

|

See also

References

Notes

- ^ From 1980 to 1983 there were dual hardcover and paperback awards of the National Book Award for Fiction. Walker won the award for hardcover fiction.

Citations

- ^ "Alice Walker". Desert Island Discs. May 19, 2013. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ a b "National Book Awards – 1983". National Book Foundation. Retrieved March 15, 2012. (With essays by Anna Clark and Tarayi Jones from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.)

- ^ "The 1983 Pulitzer Prize Winner in Fiction". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Bates, Gerri (2005). Alice Walker: A Critical Companion. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313069093. OCLC 62321382.

- ^ Moore, Geneva Cobb, and Andrew Billingsley. Maternal Metaphors of Power in African American Women's Literature: From Phillis Wheatley to Toni Morrison. University of South Carolina Press, 2017, OCLC 974947406.

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Officers of the Alice Walker Literary Society. "About Alice Walker". Alice Walker Literary Society. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f World Authors 1995–2000, 2003. Biography Reference Bank database. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- ^ "Once (1968)". Alice Walker The Official Website for the American Novelist & Poet. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ "Muriel Rukeyser was 21 when he ..." The Washington Post. September 16, 2001. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ [1] Interview with Barbara Smith, May 7–8, 2003. p. 50. Retrieved July 19, 2017

- ^ "A Headstone for an Aunt: How Alice Walker Found Zora Neale Hurston – The Urchin Movement". www.urchinmovement.com.

- ^ a b Deborah G. Plant (2007). Zora Neale Hurston: A Biography of the Spirit. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 57–. ISBN 978-0-275-98751-0.

- ^ Boyd, Valerie (2003). Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston. New York: Scribner. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-684-84230-1.

- ^ Hurston, Lucy Anne (2004). Speak, So You Can Speak Again: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston. New York: Doubleday. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-385-49375-8.

- ^ Miller, Monica (December 17, 2012). "Archaeology of a Classic". News & Events. Barnard College. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ "Alice Walker Booking Agent for Corporate Functions, Events, Keynote Speaking, or Celebrity Appearances". celebritytalent.net. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ "Alice Walker". blackhistory.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ "Alice Walker". biblio.com. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ Molly Lundquist. "The Color Purple – Alice Walker – Author Biography – LitLovers". litlovers.com. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ "Analyzing Characterization and Point of View in Alice Walker's Short Fiction". Archived May 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (February 25, 2001). "Interview: Alice Walker". the Guardian. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ a b Rosenbloom, Stephanie (March 18, 2007). "Alice Walker – Rebecca Walker – Feminist – Feminist Movement – Children". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ test (January 5, 2011). "Third Wave Foundation". Center for Nonprofit Excellence in Central New Mexico. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ "Third Wave History". Third Wave Fund. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ Justice, Elaine (December 18, 2007). "Alice Walker Places Her Archive at Emory" (Press release). Emory University.

- ^ Walker Interview transcript and audio file on "Inner Light in A time of darkness", Democracy Now! Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ "Pulitzer-Winning Writer Alice Walker & Civil Rights Leader Bob Moses Reflect on an Obama Presidency", Democracy Now! video on the African-American vote, January 20, 2009. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ "Global Women Launch Campaign to End Iraq War" (Press release). CodePink: Women for Peace. January 5, 2006. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- ^ a b Deeper shades of purple : womanism in religion and society. Floyd-Thomas, Stacey M., 1969–. New York: New York University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0814727522. OCLC 64688636.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Wilma Mankiller and others, "Womanism". The Reader's Companion to U.S. Women's History. December 1, 1998. SIRS Issue Researcher. Indian Hills Library, Oakland, NJ. January 9, 2013, p. 1.

- ^ Brown, Barry (September 5, 2009). "Toronto film festival ignites anti-Israel boycott". The Washington Times. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ Gaza Freedom March Archived September 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 2010.

- ^ Harman, Danna (June 23, 2011). "Author Alice Walker to take part in Gaza flotilla, despite U.S. warning". Haaretz. Tel Aviv. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ Urquhart, Conal (June 26, 2011). "Israel accused of trying to intimidate Gaza flotilla journalists". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Alan M. Dershowitz (June 21, 2012). "Alice Walker's bigotry". Jerusalem Post.

- ^ Tiberias (May 11, 2013). "Palestinians in Israel: Boycotting the boycotters". The Economist. London.

- ^ a b "Alice Walker says no to Hebrew 'Purple'". Times of Israel. June 19, 2012.

- ^ David Itzkoff (May 31, 2013). "Despite Protests, Alicia Keys Says She Will Perform in Tel Aviv". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Kay, Jonathan (June 7, 2013). "Where Israel hatred meets space lizards". National Post. Archived from the original on November 30, 2013.

- ^ a b c Rosenberg, Yair. "'The New York Times' Just Published an Unqualified Recommendation for an Insanely Anti-Semitic Book". Tablet. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (June 19, 2012). "In Protest, Walker Won't Allow Hebrew Translation of 'The Color Purple'". ArtsBeat. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Gavin, Patrick (June 19, 2013). "Celeb video: 'I am Bradley Manning'". Politico.

- ^ "Julian Assange is not on trial for his personality – but here's how the US government made you focus on it". Independent.co.uk. September 9, 2020. Archived from the original on September 9, 2020.

- ^ "Assange Defence Committee: Launch Event". YouTube. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021.

- ^ "Artist Alice Walker". Artists for Assange.

- ^ Harrison, Mary Hanson (January 20, 2015). "From the President's Corner". WILPF. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Walker, Alice (December 2012). "Commentary: David Icke and Malcolm X". Alice Walker's Garden.

- ^ a b O'Brien, Liam (May 19, 2013). "Prize-winning author Alice Walker gives support to David Icke on Desert Island Discs". The Independent on Sunday. London. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Walker, Alice (July 2013). "David Icke: The People's Voice". Alice Walker's Garden.

- ^ a b c Flanagan, Caitlin (April 29, 2022). "What The New Yorker Didn't Say About a Famous Writer's Anti-Semitism". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "Desert Island Discs: Alice Walker". BBC Radio 4. May 19, 2013.

- ^ Walker, Alice. "It Is Our (Frightful) Duty". Alice Walker: The Official Website. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ Cohen, Richard (December 24, 2018). "Anti-Semitism is not just another opinion. The New York Times should know better". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Alter, Alexandra (December 21, 2018). "Alice Walker, Answering Backlash, Praises Anti-Semitic Author as 'Brave'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Doherty, Rosa (December 17, 2018). "Acclaimed author Alice Walker recommends book by notorious conspiracy theorist David Icke". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "Alice Walker Defends Endorsement of anti-Semitic Book". Haaretz. JTA. December 22, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ^ "The New York Times Accidentally, Uncritically Promotes Alice Walker–Again". Tablet Magazine. May 8, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "Gayle King Under Fire For Not Grilling Alice Walker About Anti-Semitism In Recent Interview". www.yahoo.com. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Driscoll, Margarette (May 4, 2008). "The day feminist icon Alice Walker resigned as my mother". The Times. London. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008.

- ^ "Inner Light in a Time of Darkness: A Conversation with Author and Poet Alice Walker". Democracy Now!. November 17, 2006. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- ^ Parsons, Elaine (2015). Ku-Klux : The Birth of the Klan During Reconstruction. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ Krum, Sharon (May 26, 2007). "Can I survive having a baby? Will I lose myself ...?". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Black Book Publishers in the United States". The African American Experience. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ Wajid, Sara (December 15, 2006). "No retreat". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ^ Pond, Steve (September 22, 1988). "Tracy Chapman: On Her Own Terms". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ "2002 - Tracy Chapman still introspective?". About Tracy Chapman. October 15, 2002. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Lackey, Charlie (Spring 2002). "Soul Talk: The New Spirituality of African American Women". MultiCultural Review. 11: 86 – via Women's Studies International.

- ^ Reed, Wendy; Horne, Jennifer (2012). Circling Faith: Southern women on spirituality. University of Alabama Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780817317676.

- ^ Freeman, Alma (Spring 1985). "Zora Neale Hurston and Alice Walker: A Spiritual Kinship". Sage. 103: 37–40 – via Literature Resource Center.

- ^ The Art of Feminism by Lucinda Gosling, Hilary Robinson, Amy Tobin, Helena Reckitt, Xabier Arakistain, and Maria Balshaw (December 25, 2018) Chronicle Books LLC

- ^ "CANDACE AWARD RECIPIENTS 1982–1990, Page 3". National Coalition of 100 Black Women. Archived from the original on March 14, 2003.

- ^ "Fiction". Past winners and finalists by category. The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved March 17, 2012.

- ^ "Alice Walker (b. 1944)". New Georgia Encyclopedia.

Further reading

- White, Evelyn C. (2005). Alice Walker: A Life. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32826-4.

- Walker, Alice; Parmar, Pratibha (1993). Warrior Marks: Female Genital Mutilation and the Sexual Blinding of Women. Diane Books Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7881-5581-9.

External links

- Alice Walker's official website

- Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth – full video of biography film at PBS.org

- Profile at the Poetry Foundation

- Profile at Poets.org

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Alice Walker on Charlie Rose

- Template:Worldcat id

- Alice Walker collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Alice Walker collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University: Alice Walker papers, circa 1930–2014 (MSS 1061)

- Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University: Letters to John Ferrone, 1976–1990 (MSS 1104)

- Kalliope, Archives, Wilson Sharon, 1984, Alice Walker, 6(2), 37-42

- Alice Walker

- 1944 births

- Living people

- African-American novelists

- American women novelists

- American LGBT novelists

- African-American poets

- American women poets

- American LGBT poets

- African-American women writers

- American feminist writers

- Womanist writers

- African-American feminists

- LGBT feminists

- Radical feminists

- Activists against female genital mutilation

- American humanists

- American pacifists

- African-American publishers (people)

- American publishers (people)

- Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

- National Book Award winners

- O. Henry Award winners

- Pulitzer Prize for Fiction winners

- MacDowell Colony fellows

- LGBT African Americans

- Wellesley College faculty

- Anti-Zionism in the United States

- Sarah Lawrence College alumni

- Spelman College alumni

- LGBT people from Georgia (U.S. state)

- LGBT people from Mississippi

- Novelists from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Writers from Jackson, Mississippi

- 20th-century African-American writers

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American novelists

- 20th-century American poets

- 21st-century American poets

- 20th-century American women writers

- 21st-century American women writers

- Novelists from Massachusetts

- Novelists from Mississippi

- 20th-century African-American women

- Palestinian solidarity activists