Regency of Algiers: Difference between revisions

Added "Autonomous" Ottoman state of Algiers, as Algiers was always ruled by an autonomous Ottoman affiliated military elite (Jaissaries and corsairs). |

Erased a subjective paragraph without any citation. Tag: Reverted |

||

| Line 126: | Line 126: | ||

The weakening of the Algerian state began at the beginning of the 19th century due to multiple causes. First, the lack of cohesion between groups of different status: Ra'ya, Makhzen, vassal, allied, independent tribes, with in several cases feudal-type entities escaping the authority of the beylik and levying a large share of direct taxes for themselves. Then real economic difficulties, linked to the decline of the corso, the decrease in internal trade, the impoverishment of the wealthy classes and the non-development of the means of communication. The drop in [[cereal]] production was a consequence of the disorganization of this entire commercial sector which was further destabilized by the arrival of cheap Russian wheat. Finally, all these difficulties were compounded by the stranglehold of foreigners on foreign trade and renewed European attacks. The power of the dey was then at the mercy of these interventions. The interior of the country found itself shaken by a succession of revolts against the tax system and by the weakening of the central power in the face of the demands of the Christian powers. The main revolts were caused by religious brotherhoods, mainly those of [[Darqawiyya|Derqaoua]] and [[Tijaniyyah|Tidjania]].<ref name=":17" /> |

The weakening of the Algerian state began at the beginning of the 19th century due to multiple causes. First, the lack of cohesion between groups of different status: Ra'ya, Makhzen, vassal, allied, independent tribes, with in several cases feudal-type entities escaping the authority of the beylik and levying a large share of direct taxes for themselves. Then real economic difficulties, linked to the decline of the corso, the decrease in internal trade, the impoverishment of the wealthy classes and the non-development of the means of communication. The drop in [[cereal]] production was a consequence of the disorganization of this entire commercial sector which was further destabilized by the arrival of cheap Russian wheat. Finally, all these difficulties were compounded by the stranglehold of foreigners on foreign trade and renewed European attacks. The power of the dey was then at the mercy of these interventions. The interior of the country found itself shaken by a succession of revolts against the tax system and by the weakening of the central power in the face of the demands of the Christian powers. The main revolts were caused by religious brotherhoods, mainly those of [[Darqawiyya|Derqaoua]] and [[Tijaniyyah|Tidjania]].<ref name=":17" /> |

||

France would take advantage of this situation to intervene in Algeria. The evolution of Algeria - of its State and its Nation - was stopped by the [[French conquest of Algeria|French intervention of 1830]], which made the country the first victim, in the Western Mediterranean, of [[European colonization]]. |

|||

The French Historian Henri-Delmas de Grammont wrote about the Regency of Algiers: |

The French Historian Henri-Delmas de Grammont wrote about the Regency of Algiers: |

||

Revision as of 16:47, 17 July 2023

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

36°42′13.8″N 3°9′30.6″E / 36.703833°N 3.158500°E

The Regency of Algiers دولة الجزائر (Arabic) | |

|---|---|

| 1516–1830 | |

Coat of arms

| |

| Motto: الجزائر المحروسة "Algiers the well-guarded"[2] | |

![Map of the Barbary States [3]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bf/Regency-of-Algiers-1824.jpg/300px-Regency-of-Algiers-1824.jpg) Map of the Barbary States [3] | |

![Map of the Regency of Algiers [4]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fb/North_Africa%2C_from_the_%22Physical_And_Political_Map_Of_Africa_..._1822%22.png/300px-North_Africa%2C_from_the_%22Physical_And_Political_Map_Of_Africa_..._1822%22.png) Map of the Regency of Algiers [4] | |

| Status | Barbary State affiliated to the Ottoman Empire (Nominal since 1659) |

| Capital | Algiers |

| Official languages | Arabic and Ottoman Turkish |

| Common languages | Algerian Arabic Berber languages Sabir (used in trade) |

| Religion | Official, and majority: Sunni Islam (Maliki and Hanafi) Minorities: Ibadi Islam Shia Islam Judaism Christianity |

| Demonym(s) | Algerian or Algerine |

| Government | 1516–1519: Sultanate 1519–1587: Beylerbeylik 1587–1659: Pashalik 1659–1830: Stratocratic Deylik[5][6] (See Political status) |

| Beylerbey, Pasha, Agha and Dey | |

• 1516–1518 | Oruç Reis |

• 1710–1718 | Baba Ali Chaouch |

• 1818–1830 | Hussein Dey |

| History | |

| 1509 | |

| 1516 | |

| 1521–1791 | |

| 1541 | |

| 1550–1795 | |

| 1580–1640 | |

| 1627 | |

• Janissary Revolution | 1659 |

| 1681–1688 | |

| 1699–1702 | |

| 1775–1785 | |

| 1785–1816 | |

| 1830 | |

| Population | |

• 1830 | 3,000,000–5,000,000 |

| Currency | Algerian mahboub(Sultani) Algerian budju aspre Minor coins : saïme pataque-chique |

| Today part of | Algeria |

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

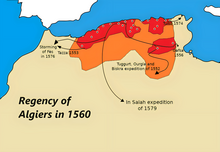

The Regency of Algiers[a] (Arabic: دولة الجزائر, romanized: Dawlat al-Jaza'ir[b]) was a state in North Africa from 1516 to 1830, when it was conquered by the French. Situated between the regency of Tunis in the east, the Sultanate of Morocco (from 1553) in the west and Tuat[15][16] as well as the country south of In Salah[17] in the south (and the Spanish and Portuguese possessions of North Africa), the Regency originally extended its borders from La Calle in the east to Trara in the west and from Algiers to Biskra,[18] and afterwards spread to the present eastern and western borders of Algeria.[19]

Throughout its existence, the Regency experienced several degrees of autonomy, eventually achieving de facto independence, with rulers emerging and being chosen locally. However the Regency continued to pay homage to the Ottoman sultan, recognizing his spiritual authority as the Caliph — the leader of the Islamic world.[20]

The sixteenth century witnessed the clash between the Spanish and Ottoman empires in the Mediterranean and the rise of the Algerian regency in North Africa - a unique society ruled by both heavily autonomous Turkish Janissary army corp and a multiethnic Corsair community, supported by the plunder from corsairs engaged in a holy war against Spanish Christendom. This regime, founded by Oruç Barbarossa and his younger brother Hayreddin Barbarossa, brought the entire central Magreb under its control.[21]

After the war between the two empires ended in the early 17th century, Algerian pirates who refused to recognize peace found new territories for their plunder when France, England and the United Kingdom of the Netherlands made peace with Spain. Soon the lords of Europe found themselves in an embarrassment as their merchant ships and goods were captured and their subjects enslaved, and they clamored for relief. The sultan could not force his vassals to behave, while great princes, such as the kings of France and England, were willing to deal directly with the regency. A more or less reasonable settlement was reached after a century of negotiations and wild sea operations, but by this time the pirates had expanded their piracy across the Atlantic, and by 1650 there were some 25,000 Christian slaves in Algiers.[21]

With the Janissary coup in 1659, Algiers became a Stratocracy, a sort of a military republic, practically independent from the Sublime porte, yet the regime was very unstable, which resulted first in a Corsaire coup in 1671, and finally the Dey Ali chaouch refusing to allow Ottoman pashas to be sent to Algiers from 1710 on, assuming himself this title and thus guaranteed a relative stability in power.[22]

After a phase of decline in the second half of the 18th century, linked to the consolidation of diplomatic relations with European states and the regency's attempt to better fit into Mediterranean trade, the corso experienced three successive bursts with the contraction exchanges during the European wars of the French Revolution and Empire: in 1793, then between 1802 and 1810 and finally after 1812, when merchant ships from Algiers, Tunisia and Tripolitania were definitively excluded from European ports. The balance between the two shores of the Mediterranean which maintained the permanence of the corso broke at the beginning of the 19th century: after the commitment to put an end to the slave trade made at the Congress of Vienna and in an economic context where commercial development was not accommodate maritime insecurity, European states were acting together for the first time. As historian Daniel Panzac shows, the Anglo-Dutch expedition led in 1816 under the command of Lord Exmouth marked a decisive turning point, practically putting an end to the corso.[23]

The weakening of the Algerian state began at the beginning of the 19th century due to multiple causes. First, the lack of cohesion between groups of different status: Ra'ya, Makhzen, vassal, allied, independent tribes, with in several cases feudal-type entities escaping the authority of the beylik and levying a large share of direct taxes for themselves. Then real economic difficulties, linked to the decline of the corso, the decrease in internal trade, the impoverishment of the wealthy classes and the non-development of the means of communication. The drop in cereal production was a consequence of the disorganization of this entire commercial sector which was further destabilized by the arrival of cheap Russian wheat. Finally, all these difficulties were compounded by the stranglehold of foreigners on foreign trade and renewed European attacks. The power of the dey was then at the mercy of these interventions. The interior of the country found itself shaken by a succession of revolts against the tax system and by the weakening of the central power in the face of the demands of the Christian powers. The main revolts were caused by religious brotherhoods, mainly those of Derqaoua and Tidjania.[22]

The French Historian Henri-Delmas de Grammont wrote about the Regency of Algiers:

For more than three centuries it has been the terror and the scourge of Christianity; none of the European groups has been spared by its bold sailors, and the echo of its vast prisons has repeated the sound of almost all the languages of the earth. It has given the world the singular spectacle of a nation living on the corso and living only by it, resisting with incredible vitality the incessant attacks directed against it, subjecting to the humiliation of an annual tribute three quarters from Europe to the United States of America; the whole, in spite of an unimaginable disorder and daily revolutions, which would have killed any other association, and which seemed to be indispensable to the existence of this strange people. And, what an existence!

— Henri-Delmas de Grammont, Histoire d'Alger sous la domination turque, 1515-1830

Toponymy

The establishment of the current divisions of the Maghreb goes back to the installation of the three regencies in the sixteenth century: Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli. Algiers became the capital of its state and this term in the international acts applied to both the city and the country which it ordered: الجزائر (El-Djazâ'ir). However a distinction was made in the spoken language between on the one hand El-Djazâ'ir, the space which was neither the Extreme Maghreb, nor the regency of Tunis, and on the other hand, the city commonly designated by the contraction دزاير (Dzayer) or in a more classic register الجزائر العاصمة (El-Djazâ'ir El 'âçima, Algiers the Capital).[24]

The regency, which lasted over three centuries, shaped what Arab geographers designate as جزيرة المغرب (Djazirat El Maghrib). This period saw the installation of a political and administrative organization which participated in the establishment of the Algerian: وطن الجزائر (watan el djazâïr, country of Algiers) and the definition of its borders with its neighboring entities on the east and west.[25][26]

In European languages, El Djazâïr became Alger, Argel, Algiers, Algeria, etc. In English, a progressive distinction was made between Algiers, the city, and Algeria, the country. Whereas in French, Algiers designated both the city and the country, under the forms of "Kingdom of Algiers" or "Republic of Algiers".

“Algerians” as a demonym is attested in writing in French as early as 1613 and its use has been constant since that date.[27] Meanwhile in the English lexicology of the time, Algerian is "Algerine", which referred to the political entity that later became Algeria.

A French document from 1751 describes “patriots or Algerians properly so called” and adds that “the King does not complain of the Algerian nation but only of the Dey as an offender of the treaties”. The terms "Algerian patriots" and "Algerian nation" should be understood in their use of the 18th century. The expression “Algerian patriots” designates the indigenous inhabitants of the country. The term "Algerian nation" refers to all the inhabitants of the country that the French report of the time wanted to differentiate from the country's leaders of Turkish origin.[28] However the Spanish King Charles IV of Spain refers to the Dey of Algiers as a representative of the "Algerian nation" in the peace treaty of 1791.[29]

History

Central Maghreb in the early 16th century

After the fall of the Emirate of Granada in 1492, Spain experienced significant military and economic growth, which contributed to a gradual rise of Spain and Portugal as two powerful countries. Benefitting from their geographical discoveries in the Americas and the Cape of Good Hope, they shifted to expansionary imperial projects, one of which was the subjugation of ports along the coastlines of the Maghrebi countries. They planned to make them into both stations for the repair of ships sailing to India as well as bases for incursions into Africa. Through establishing sea routes in the Atlantic Ocean, the Portuguese were able to successfully reach the coasts of West Africa and benefit directly from the gold trade, which in turn diminished the importance of the desert trade routes that linked the Maghreb and Europe.[30]

The Spanish imperial project manifested through the domination the cities of the Maghreb, many of which were stations for desert trade caravans from western Sudan, Tripoli and Tunis in the east and Ceuta and Melilla in the west, passing through Bejaia, Algier Oran and Tlemcen. Maintaining control over this trade and its two main commodities, gold and slaves, became essential for the Spanish treasury.[31] In addition, controlling the two shores of the Mediterranean gave the Spanish Empire, which at the time included present-day Italy, the ability to control and monopolize maritime trade between the western and eastern Mediterranean, especially the trade resources in Naples and wheat in Sicily.

The loss of the middle Maghreb's role as a mediator of commercial exchange between Europe and Africa - especially that of gold - led to a period of economic stagnation, a decline in trading resources, and a deterioration of craftsmanship in its two prominent historical capitals - Bejaia and Tlemcen. The country subsequently entered a state of political fragmentation and weak centralization, exacerbated by the negative effect of the Iberian trade monopoly on its capacity to collect taxes and the activities of its merchant class.[32]

The three countries of the Maghreb became quite vulnerable to incursions from the northern shore of the Mediterranean. Within a span of two decades, the Spanish Empire captured multiple important cities and ports along the shores of the Maghreb. The first along the Moroccan coastline to fall was Melilla in 1497, followed by the Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera in 1508. Along the Algerian shores, the city of Mers El Kébir fell in 1505, followed by Oran - the most important sea port directly linked to Tlemcen, the capital of the Zayyanid Kingdom at the time - in 1509. [33] Bejaia in Eastern Algeria and Tripoli in Libya were taken shortly thereafter in 1510, and other coastal cities such as Algiers and Tunis chose to submit to Spanish sovereignty through humiliating agreements.[34]

Establishment

Barbarossa brothers arrive in 1512

Beginning in 1512, the Turkish privateer brothers Oruç and Hayreddin—both known to Europeans as Barbarossa, or "Red Beard" operated successfully off Tunisia under the Hafsids. Their victories against Spanish naval vessels at sea and on the shores of Andalusia became famous. As such, scholars and notables of Bejaia contacted them that year, along with the Hafsid emir of Constantine, Abu Bakr, requesting their assistance in dislodging the Spaniards out of Bejaia. However, their attempt to do so ended in failure due to the formidable fortifications of the city, as well as the Spaniards' cooperation with the princes of Beni Abbas. Oruç was wounded while trying to storm the city, and his arm had to be amputated after physicians failed to treat it.[35] Oruç realized that positioning his forces in the valley of La Goulette distanced them from the battlefield and ultimately hampered their efforts against the Spaniards. Accordingly, he decided to search for a new position closer to Bejaia, and chose Jijel, a trading center between Africa and Italy occupied since 1260 by the Genoese. An opportunity emerged for Oruç he received pleas for aid from its inhabitants, successfully taking the city in 1514 and establishing it as his base of operations.[36] After settling in Jijel, Oruç and his brothers began attending to the persecuted Muslims in Andalusia, starting to frequent the shores of Andalusia in order to evacuate them. In view of the success achieved by Oruç in Jijel, its inhabitants pledged allegiance to him as their prince,[37] as did the tribal elders and the Emir of Kuku. Ahmed bin al-Qadi urged him to attack the Spaniards in Bejaia, and so he embarked on a campaign against them in 1514 with a land army, besieging the city for nearly three months but ultimately to no avail. He was forced to lift the siege, but repeated the attempt in the spring of the following year with a large force, only to be forced to withdraw once again when his ammunition ran out and the Hafsid Emir refused to provide him with more, succeeding only in capturing hundreds of Spanish prisoners.[38][39]

Capture of Algiers in 1516

The takeover of Oran by Pedro Navarro and Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, as well as the occupation of Bougie, awakened the Algerian population to the imminent Catholic threat. Unable to mount a sufficient resistance to the Spanish's arms, they agreed to submit, promising to recognize the Catholic king Ferdinand II of Aragon as their sovereign, to pay him a yearly tribute, to release the Christian prisoners, to forsake piracy, and to prevent the enemies of Spain from entering their harbor (31 January 1510). A delegation of significant individuals escorted the shaikh Salim al-Tumi of the Thaaliba to Spain, where he took the oath of allegiance and presented gifts to Ferdinand. In order to ensure the fulfillment of the stipulations regarding piracy and to observe the residents of Algiers,[40] Pedro Navarro captured the island of Peñon, which was within range of the city's artillery. He built a fort on it and garrisoned it with 200 men. The Algerians, suffering from the suppression of piracy and trade, grew disillusioned with the situation and sought to break free from the Spanish yoke. Taking advantage of the excitement throughout the Barbary at the news of the death of the king Ferdinand, they sought help from Oruç and his men.[37]

The new masters of Algiers

A delegation of the city's residents went to Jijel in 1516 and complained to Oruç of the constant distress and danger they faced. He had been planning for a final offensive against Bejaia then, but ultimately decided to abandon his plans and aid the citizens of Algiers. Oruç embarked at the head of a land force of 5,000 Kabyles and 1,500 Turks, followed by 800 arquebusiers, while Hayreddin led a naval fleet of 16 galliots. They rendezvoused in the city of Algiers[41] where the population celebrated their arrival and hailed them as heroes.[42] Hayreddin immediately launched a naval bombardment of the Spanish fort, while Oruç headed to Cherchell, then held by another Turkish captain named Qara Hassan, who had been cooperating with some Andalusian immigrants. Oruç eliminated him, taking control of the city before returning to Algiers.[37] Oruç's help had been sought to dislodge the Spaniards from their commanding position on the island, and although popular demand led to his intervention, the ruler of Algiers at that time - Salem al-Tumi - only acquiesced to his presence. Oruç did not possess the means to recover the Peñon of Algiers immediately, and as his presence often undermined al-Thumi's own authority, the latter eventually sought the help of the Spaniards to drive him out of the city. In response, Oruc forced the Algerian leaders to accept his authority,[37] arresting Salem al-Toumi and assassinating him in his house.[43] He then proclaimed himself "Sultan of Algiers", and his banners in green, yellow, and red were raised above the forts of the city.[44][45][46]

The Spanish response

The Spaniards considered the presence and activity of Oruç and his two brothers in the city of Algiers a severe threat to their interests across North Africa, and thusly resolved to expel them. To achieve this goal they allied with the Emir of Ténès - subject to them - and wooed the followers of Salem al-Toumi along with some of the leaders of the neighboring tribes of the city onto their side through their agents and spies. They then dispatched a great force from Oran led by its Spanish governor Diego de Vera, which arrived in Algiers in late September 1516 where it landed near Bab al-Oued. Oruç allowed the force to land before he finally moved against it, taking advantage of its retreat and the emergence of a northern wind to drown, kill, and capture many of its men. The expedition proved to be a total defeat for the Spaniards, and a momentous victory for Oruç, his brothers, and the residents of Algiers. This victory would prompt the residents of Blida, Miliana, Médéa, Dellys and Kabylia to pledge allegiance to Oruç, expanding his growing influence further.[47]

Campaign of Tlemcen in 1518

In light of the Prince of Ténès - Hamid bin Abid - subjugation by the Spaniards and his active cooperation with them, such as his participation in the expedition against Algiers, Oruç elected to take revenge by seizing his city. He set off towards Ténès at the head of large force, vanquishing the enemy army at the Battle of Oued Djer before entering the city in June 1517, where he killed the prince and expelled the Spaniards stationed there. He then divided his newfound kingdom into two parts; an eastern part based out of Dellys to be ruled by his brother Hayreddin, and a western part centered on the city of Algiers to be ruled by him personally.[48] While Oruç was in Ténès, a delegation from the city of Tlemcen came to him to complain about the poor conditions in their country and the growing threat of a Spanish occupation of their city, exarcebated by squabbling between the Zayyanid princes over the throne. Abu Ahmed III had seized the throne in Tlemcen by force after he expelled his nephew, Abu Zian III, and put him in prison. Oruç elected to fulfill the wishes of the delegation, and appointed his brother Hayreddin as a ruler over the city of Algiers and its surroundings.

The Death of Oruç Barbossa

Oruç marched towards Tlemcen, capturing the castle of Banu Rashid along the way, and garrisoning it with a large force led by his brother Isaac in order to protect his rear. Oruç, along with his troops, entered the city and removed Abu Zayan from prison, restoring him to his throne, before progressing westward along the Moulouya to bring the Beni Amer and Beni Snassen tribes under his authority.[49] Abu Zayan began to conspire against Oruç shortly after his reinstatement, plotting to assassinate him or to drive him from the country, which eventually prompted Oruç to arrest and execute him. Meanwhile, the deposed Abu Ahmed III fled to Oran to beg for help from his former enemies - the Spaniards - to retake his throne. The Spaniards chose to answer his pleas, capturing the Banu Rashid castle and killing the commander Isaac in late January 1519 with the help of a few local allies before marching against Tlemcen, which was placed under a severe siege. Oruç was forced to sit in the council for several days to avoid a hostile populace which eventually opened the gates for the Spanish troops.[49] Oruç attempted to flee Tlemcen under the cover of night in the direction of Bani Yazanasin near the sea coast, but the Spaniards became aware of this, pursuing him and killing him along with his Turkish companions between Al-Maleh (Riosalado) and the corner of Sidi Musa in the same year.[50] His head was then sent to Spain, where it was paraded across its cities and those of Europe. His robes were also sent to the Church of St. Jerome in Cordoba, where they were kept as a trophy.[citation needed].[51]

Algiers joins the Ottoman Empire (1519-1533)

Hayreddin was proclaimed Sultan of Algiers[52] sometime between the end of October and the beginning of November 1519. Following a disastrous attempt by the Spanish Empire to take Algiers in 1519 led by Hugo of Moncada,[53] an assembly made up of Algerian notables and ulemas led a delegation to present to the Ottoman Sultan Selim I a proposal to attach Algiers to the Ottoman Empire.[54] Hayreddin became increasingly aware of the necessity of Ottoman aid as the difficulties he had faced following the defeat at the hands of the Spaniards and Zayyanids years earlier were exacerbated by the reversal of his alliance with the Kingdom of Kuku, which had joined forces with the Hafsids to inflict a severe defeat on him in the Isser Wadi in 1519. These losses, along with the deterioration of various forms of support on the internal level emphasized the necessity of external support to maintain his possessions around Algiers.[55] As such, the delegation was tasked with making the strategic importance of Algiers in the Western Mediterranean understood to the Ottoman Sultan. The proposal was not initially welcomed with enthusiasm by Constantinople, which found the idea of integrating a territory so distant and so close to Spain into its sphere of influence unfeasible. The idea was even considered perilous and was only definitively accepted under Suleiman in 1521.[56] Hayreddin Barbarossa was named Beylerbey (equivalent of Emir of emirs).[52] The important role of the regency fleet in the Ottoman maritime campaigns and this voluntary membership gave a particular character to the relations between Algiers and Constantinople. The regency was considered not a simple province but an Imperial Estate.[57] This state was very important in the eyes of the Turks, because it was the spearhead of Ottoman power in the western Mediterranean.[58]

Hayreddin's reconquest of Algiers

After the defeat at Isser against the joined Kuku-Hafsid forces then the capture of Algiers in 1520. the conquest of the Kabyles of Kuku began a five to seven year period of rule by the Sultan of Kuku Belkadi over Algiers (1520-1525/1527).[59] Qara Hasan, former Agha of Hayreddin, concluded an agreement with Belkadi, settled in Cherchell and reigned over the western province: the coast from Tipaza to Cherchell. This period marked the toponymy of Algiers where a mountain is called Djebel Kuku. Hayreddin only returned to Algeria in 1521, landing at Jijel from whence he put himself in correspondence with the new principality of Kalâa of Ait Abbas, a rival of Kuku.[60] Hayreddin continued his progress in the east with Abdelaziz Amokrane: taking Collo in 1521, Annaba and Constantine in 1523, then with the support of the Beni Abbès, crossed their stronghold of the Babors and the Soummam River. The Djurdjura was crossed without incident, but at Iflissen they had to face a detachment of Belkadi, which they defeated. Belkadi then withdrew to Tizi Naït Aicha (Thénia) to block the main access roads to Algiers. Hayreddin detoured to enter the Mitidja plain. Before the final battle, Belkadi was killed by one of his soldiers. The debacle caused by the assassination opened the way to Algiers, where the population, which had complained about the government of Belkadi opened the doors to Hayreddin in 1525 or 1527.[61] Hayreddin restored the odjack of the Janissaries, took the road to Cherchell and defeated Qara Hassan. He also contacted the Zayyanid sultan Moulay Abdallah to tell him that he intended to collect the tribute he owed as a vassal of Algiers.[citation needed]

Conquest of the Peñón of Algiers

Hayreddin Barbarossa had finally succeeded in re-establishing his authority in Algiers, Mitidja, Cherchell and Ténès. But Algiers was still threatened by the Spaniards installed at the Peñon, from which they controlled the movements of the port. This thorn in the back of the city had to be removed at all costs. Hayreddin summoned the Spanish commander of the position, Don Martin de Vargas, to surrender with his garrison of two hundred soldiers. With this ultimatum rejected,[62] he attacked and bombarded the Peñon which was completely destroyed on May 27, 1529.[63] With the materials salvaged, the island was attached to the land, hence the "Kheir ad Dine Jetty" which today connects the Admiralty to the land. This was the starting point for the development of the port of Algiers, which will be continued by the elevation of the enclosure and the construction of the main bordj on the north and south islets.[62] The capture of the Peñon had a huge impact in Europe and Africa. The Ottomans were firmly established in Algiers; their power eclipsed that of the Spaniards, both in the Mediterranean and in Europe, where they threatened Austria and Hungary. A new destiny was about to open up in the central Maghreb, a new state to be founded there.[63]

Expedition to Cherchell

In Spain, the last successes of Hayreddin Barbarossa left a profound repercussion, the echo of which reached Charles V, then occupied in concluding the convention of Augsburg with the Lutherans. From there, the Emperor sent Andrea Doria the order to make a new attempt against the Barbary. In the month of July 1531, the Admiral left Genoa with twenty galleys, carrying 1500 landing men. He landed unexpectedly at Cherchell, seized that town and freed a thousand Christian captives who were moaning there.[64] But the Turks took refuge in the citadel while the troops disbanded to engage in looting. Taking advantage of this disorder, the Turks sallied out, individually massacred some of the invaders and forced the others to hasten to the galleys.[64][65] Some of the other Turks opened fire on the galleys, as a result Doria set sail fearing that he may see his vessels sink and understanding that his soldiers were hopelessly lost.[66] Barbarossa, supported with 35 galleys, attacked Doria near Genoa and burnt 22 Genoese galleys.[67]

The Morisco rescue missions

The Moriscos had many opportunities to flee and emigrate with the marauding muslim ships in the western mediterranean, to the point that Hayreddin ships transported to the shores of the Maghreb about 70,000 of them.[68] Often, the number of ships was not sufficient to carry all the refugees, so the garrison was forced to land on the enemy's coast, leaving its place to the immigrants and remaining there as a guard for the ones left behind from the people of Andalusia hoping for the Turkish convoy to return to them and save them From their calamity, the Turkish ships continued on their rescue mission between Algeria and Andalusia seven times, Hayreddin offered for the Andalusian refugees to settle in the land of Algeria, and left them to choose the spots and places most suitable for them corresponding to their purposes in carrying out their professional work and their various industries. At the top of the city from the suburb close to the Kasbah Palace in Algiers, which is the area known today as the "Thaghriyyin" or Tagarin, and some of them lived in the plain of Mitija in the areas of Blida, and some of them settled in the city of Tadlis and Tlemcen and Oran and Mostaganem and Cherchell, which they builTt in it - as Al-Hassan bin Muhammad Al-Wazzan said: "2,000 houses, and among them were those who settled in Morocco and Tunisia. the Maghreb people learned much of their craft, imitated their luxury, and rejoiced in them".[68]

Called in 1533 by the Sultan to exercise the function of captan pasha, Hayreddin left in Algiers as his deputyHassan Agha. The government then organized itself empirically with the successors of Oruç and Hayreddin Barbarossa.[69]

The last speech of Hayreddin Barbarossa to the Algerians is recorded in an Arabic manuscript that is quoted by Jean Michel de Venture de Paradis (1898):

“Now that there is nothing left to do for your happiness and the safety of the city, I have resolved to leave you; other works, other combats call me; I am leaving places where Christians will no longer dare to reappear and I am going to seek, under the glorious and invincible banners of the sultan, new opportunities to fight the infidels. When I came among you, you were weak, without money, without guns, without warriors; I leave you today a troop of brave men who will know how to make the Algerian name respected, and ships, munitions of war to attempt new enterprises. Your ramparts are guarded by more than four hundred pieces of cannon, which your enemies themselves brought to you and which Allah caused to fall into your hands at the moment when they were about to crush you. So here I am at peace with your fate: the time when I can leave you has finally come. Choose among you the one whom you will believe the most worthy to command and swear to obey him faithfully!”.

To the notables and the mufti who proposed to him, on behalf of the population, to stay in Algiers to continue his work, Hayreddin declared:

“In such a situation I see only one course to take: Algiers (the victorious city) must be put under the protection of Allah; and after him, under that of my sovereign and master, the powerful and redoubtable Emperor of the Ottomans. Victory directs his steps everywhere, and if he deigns to receive us as subjects, he will provide us with relief in money, men and munitions of war, which will allow us to brave and defeat our enemies”.[63]

-

Oruç Barbarossa statue in the Central Museum of Algerian Army

-

Oruç Reis statue in Aïn Témouchent, Algeria

-

Reproduction of Oruç Barbarossa's ship, in Jijel, Algeria

-

Flag of the Barbarossa brothers in the National Maritime Public Museum, Algiers

-

Hayreddin Barbarossa, by Algerian miniaturist Mohammed Racim

Hayreddin's successors

Hayreddin Barbarossa established the military basis of the regency. The Ottomans provided a supporting garrison of 2,000 Turkish troops with artillery.[70] He left Hasan Agha in command as his deputy when he had to leave for Constantinople in 1533.[71]

Charles V expedition to Algiers

Two years later, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V conquered Tunis against the troops of Hayreddin Barbarossa and established Spanish guardianship over the city. In October 1541, an expedition was led this time against Algiers to put an end to the Barbary pirates who were spreading terror in the western Mediterranean. A fleet led by Andrea Doria was dispatched with the help of the allied nations including the fleets of the Republic of Genoa, the Kingdom of Naples, the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem to transport the troops from Spain and the Netherlands. Embarked late, the fleet arrived in front of Algiers as a storm formed.[72] The landing of the troops was delayed and only a few troops found refuge on land under an increasing storm. Due to extremely unfavorable conditions, the troops on the ground, exhausted and fighting in the rain with knives, were defeated on October 25 by the Algerian defenders led by Beylerbey Hassan Agha.,[73] after fighting in the rain, hand to hand, with knives. Meanwhile, the fleet is in distress,[74] ships were thrown to the coast and rescuers were unable to approach. The siege was lifted, sounding a difficult retreat under the assaults of the enemy cavalry, the troops however reached Cap Matifou where Doria awaited them with the remaining ships. Leaving the material, including 100 to 200 guns which would be recovered to furnish the ramparts of Algiers, the Christian ships reached Bougie after two days.

The chronology of the expedition reconstructed by Daniel Nordman.[75]

- October 18, 1541: departure of the expedition from Majorca;

- October 19: arrival of the expedition in sight of Algiers;

- October 20: At 7 a.m., the fleet is in the harbor of Algiers. At 3 p.m. the sea swells, Charles V's fleet takes shelter near Cape Matifou and the Spanish fleet at Cape Caxine;

- October 21: the fleet remains under cover;

- October 22: the fleet still in shelter but reconnaissance of the beach and water supply;

- 23 October: return of the Spanish fleet, landing of Spanish, then Italian and German troops (Charles V is ashore at 9 a.m.). Installation of the camp in Hamma. Night attack by the Algerians;

- October 24: Installation of Charles V's headquarters at Koudiat es-Saboun. Beginning of the fights. The storm rises around 9 p.m.;

- October 25: storm, Algerian sortie, combat of Ras Tafoura. The storm increases in power destroying part of the fleet with provisions and war material, the rest will take shelter at Cape Matifou;

- October 26: the storm lasts, Charles V is on the shore, the retreat is decided (the horses are slaughtered) along the sea to the Knis wadi;

- October 27: retreat to Wadi El-Harrach;

- October 28: crossing of the overflowing wadi;

- October 29: the retreat continues to Cape Matifou and gathering of forces;

- October 30: reconstitution of the forces with rest, council of war and repair of the fleet;

- 31 October: beginning of the re-embarkation of Italian troops;

- 1 November: re-embarkation of Charles V and German troops;

- 2 November: re-embarkation of Spanish troops. The sea is growing again;

- November 3: navigation in the storm;

- November 4: landing of Charles V at Bougie. Dispersal of the remains of the expedition fleet for Spain, Majorca and Sardinia;

- 5 November: arrival of the last five boats in Bougie.

War with Spain for the Zayyanid Kingdom

In 1544, Hasan Pasha, Hayreddin's son, became the first governor of the Regency of Algiers to be directly appointed by the Ottoman Sultan, according to Diego de Haëdo, he took the title of beylerbey through a demand by Hayreddin Barbarossa to the Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent,[76] however, Hassan Agha was not a Beylerbey according to de Grammont, he was only a Khalifat, or a deputy to Hayreddin Barbarossa.[77] the Beylerbeys or Emirs of Emirs in arabic or Princes of princes continued to be nominated for unlimited tenures until 1587.

In 1534, Martín Alonso Fernández de Córdoba Montemayor y Velasco, conde de Alcaudete took over the stronghold of Orán, from where successive expeditions set out to try to gain control of Mostaganem.

The first expedition was carried out in 1543, in which the Count of Alcaudete and his son Alonso de Córdoba, Count of Alcaudete mobilized an army between 5,000 and 7,000 men.[78][79] They left on March 21, and first attacked Mazagrán and then besieged Mostaganem. The Turks sent six ships from Algiers, and had about 1,500 men to defend the city. The absence of artillery made it impossible to breach the city walls, and they had to lift the siege and withdraw at night, yet the Turks were warned, and caused a large number of casualties among the Spanish troops on their return to Oran.[79]

In 1547, Count Alcaudete made a second expedition, arriving first at Mazagrán on August 21, and later moving on to Mostaganem. In this case, the city was defended only by forty Turks, although they later received reinforcements from Algiers. Despite the insistent artillery attacks from the Spanish, the Ottoman Algerian resistance meant that the count's troops had to retreat hastily towards Oran, again suffering significant casualties.[80]

Both defeats were caused by poor campaign planning, a shortage of ammunition, and a lack of experience and discipline among the Spanish troops.[81][79]

In 1551 Hasan Pasha, the son of Hayreddin, defeated the Spanish-Moroccan armies during a campaign to recapture Tlemcen, thus cementing Ottoman control in western and central Algeria.[82]

After that, the conquest of Algeria sped up. In 1552 Salah Rais, with the help of some Kabyle kingdoms, conquered Touggourt, and established a foothold in the Sahara.[83]A year later, Salah Reis expelled the Portugese from the penon of Valez before leaving a garrison there.[84]

In 1555, the Regency of Algiers managed to score two decisive victories against the Spanish empire in Bougie and then Mostaganem three years later, thus cementing Ottoman control in North Africa for good. During the 16th, 17th, and early 18th century, the Kabyle Kingdoms of Kuku and Ait Abbas managed to maintain their independence[85][86][87] repelling Ottoman attacks several times, notably in the First Battle of Kalaa of the Beni Abbes then in the Battle of Oued-el-Lhâm.

Ottoman dominance in the Maghreb

Algiers became a base in the war against Spain and also in the Ottoman conflicts with Morocco. Between April and June 1563 the Regency of Algiers launched a major military campaign to retake the Spanish military-bases of Oran and Mers el Kébir on the North African coast, occupied by Spain since 1505. Algiers, the Principalities of Kabylia (Kuku and Beni Abbes), and other vassal tribes combined forces as one army under Hasan Pasha, and Jafar Catania. The Spanish commander brothers, Alonso de Córdoba Count of Alcaudete and Martín de Córdoba, managed to hold the strongholds of Oran and Mers El Kébir, respectively, until the relief fleet of Francisco de Mendoza arrived and successfully caused the attackers to rout.[88] .After Spain sent an embassy to Constantinople in 1578 to negotiate a truce, leading to a formal peace in August 1580 since the Regency of Algiers was a formal Ottoman territory at that time, rather than just a military base in the war against Spain.[71]

In the west, the Algerian-Sharifian conflicts shaped the western border of Algeria.[89] There were numerous battles between the Regency of Algiers and the Sharifian Saadi dynasty in Morocco. For example: the campaign of Tlemcen in 1551, the campaign of Tlemcen in 1557 in which the independent Kabylian Kingdoms also had significant involvement, the Kingdom of Beni Abbes participated in the campaign of Tlemcen in 1551 and The Kingdom of Kuku also participated in the Battle of Taza (1553) and the capture of Fez in 1554 in which Salih Rais defeated the Moroccan army and conquered Morocco up until Fez, placing Ali Abu Hassun as the ruler and vassal to the Ottoman sultan.[90][91][92]

The Kingdom of Kuku provided Zwawa troops for the capture of Fez in 1576 in which Abd al-Malik was installed as an Ottoman vassal ruler over the Saadi dynasty by Caïd Ramazan pasha of Algiers.[93][94]

In 1569 the Beylerbey of Algiers, Uluç Ali, set off over land toward Tunis with 5,300 Turks and 6000 Kabyle cavalry from the Kingdom of Kuku and the Kingdom of Beni Abbes.[95]

Uluç Ali encountered the Hafsid Sultan at Beja, west of Tunis, Uluç Ali defeated him in battle and conquered Tunis without suffering any great losses.[96] Mulay Ahmad III was forced to take refuge in the Spanish presidio of La Goleta in the bay of Tunis. The Christian forces were able to recover Tunis in 1573[97] however the Ottoman forces under Uluç Ali conquered Tunis yet again in 1574.

Relations with Ottoman empire worsen

The Ottoman Capitulations to France

In the early 17th century, warring Europe signed peace treaties that ended hostilities with the Ottoman Empire. At the turn of the century, Spain made peace with France (1598), England (1604), and the Netherlands (1609); the Ottoman Empire made peace with Austria (1606) and the Netherlands (1612). Before that, France and Great Britain concluded so-called Capitulations treaties with the Ottoman Empire in 1536 and 1579 respectively. The immediate effect of the peace between these countries was the establishment of diplomatic relations with Algiers. These capitulations gave extraterritorial rights to foreigners living in the Ottoman Empire. They were originally intended to encourage trade, but were gradually used by Europeans to establish spying networks in the Ottoman Empire. Algiers disapproved of Constantinople's foreign policy, which they believed gave too many privileges to foreigners.[98]

For their part, the Janissaries who were stationed in and paid by Algiers, also came to disregard the sultan's orders. They decided sovereignly on war operations, taking into account neither the capidji sent by the sultan nor the alliances concluded by Istanbul.[99] The Sublime Porte renewed the treaty in 1604 giving even more privileges to France in total ignorance of Algerian interests. Clause 14 of the treaty, for example, authorized the French king to use force against Algiers in case the treaty was not respected. This prompted Khider Pasha of Algiers to attack the Bastion, the pasha himself seized 6,000 sequins which the sultan Ahmed l had sent to French merchants to compensate them for losses caused by the raid on the Bastion of France an act for which the Sultan ordered Khider pasha hanged up, even after the nomination of a new pasha, the French could not rebuild this Bastion: the diwan of the Janissaries opposed it and decreed that whoever undertook it would be punished by death.[100] The diwan even refused to receive the French envoy accompanied by a representative of the sultan. It's quite simply that relations with France were seen in a diverging way by Algiers and by Istanbul.[99]

The differences between Algiers and Constantinople remained unresolved despite the execution of the pasha and a Firman that ordered the restoration of the fort and respect the French "rights". France then decided to negotiate directly with Algiers. Negotiations began in 1617 but soon reached an impasse. Part of the trouble stemmed from the question of the return of two Algerian cannons seized by the Dutch traitor Zymen Danseker when he left the Algerian navy in 1607 and given to the Duke de Guise, governor of Provence.[101] Two years later, negotiations were on the verge of collapse when the Algerian delegation was massacred in Marseilles, allegedly because an Algerian rais had hijacked a provincial ship. Hostilities again increased; nevertheless, a treaty was concluded in 1619.[102][103]This was the first treaty signed between Algiers and a foreign country. However, Algiers continued to firmly reject the Franco-Ottoman Capitulations of 1604 and the concessions granted to France.

Ali Bitchin Reis

The Pasha, representative of Isbanbul, did not in fact have full authority: over time, Raïs and Janissaries acted only according to their interests and for the interest of Algiers. The Rais, who formerly responded to the sultan's slightest appeal, came to discuss his orders. They began by demanding compensation when they were asked for a ship; they even demanded that any indemnity be paid in advance. In 1638, they felt they had been betrayed by Istanbul. They had been called by the sultan Murad IV to fight Venice, but a storm having forced them to take shelter in a port, the Venetians attacked them there and destroyed part of their fleet in Valona.[104] Then, Venice having bribed the viziers, the sultan made peace with Venice to the great anger of the Algerian corsairs.

A raïs, Ali Bitchin, head of the tai'fa(community of Corsair captains) from 1630 to 1646, became, at that time, the main character in Algiers.[105] Admiral of all the galleys, head of the corporation of corsairs, he was immensely rich: having two palaces in Algiers, a mosque built by himself, nearly 500 slaves in his private prisons, not counting those who rowed on his galleys.[106] Married to a daughter of the King of Kuku, thus benefiting from the sympathy of the Kabyles, relying on the Koulouglis, counting on his friend Ali Arbadji pasha of Tripoli, Ali Bitchin wanted to be the chief of Algiers and pursue an independent policy. The sultan Ibrahim IV, fearing to see an autonomous power assert itself, sent in 1644 to Algiers two chaouch to bring him the head of Ali Bitchin and those of four other heads of the tai'fa. But at the call of Ali Bitchin, the population rose up and the Pasha of Algiers, accused of being the instigator of these schemes, was arrested. The diwan of the militia had tolerated Ali Bitchin's insubordination, but in return demanded that he pay the Janissaries' salaries. Ali Bitchin took refuge in Kabylia, stayed there for nearly a year, then returned in force to Algiers. He reigned there as a true master, claimed the official title of pasha and claimed from the sultan Mehmed IV, in 1649, 60,000 golden soltanis for the dispatch of 16 galleys. The sultan then appointed another pasha, and when the latter arrived, Ali Bitchin died suddenly, possibly poisoned.[107]

Relations with the Kingdom of France

The Bastion de France trade center

In 1561, two merchants from Marseilles, Thomas Linchès and Carlin Didier, joined hands to trade with the tribes of the Algerian coast and founded, to the east of Bône, a trading post and a station for fishing coral, under the name of the Bastion de France. The concessions carried on a great trade in grain; in ordinary times the authorities of Algiers saw no harm in it, but in the event of famine they did not allow the export of wheat. The French factories were then attacked, which often displeased the tribes who traded with these counters, because given the lack of means of transport, they could not sell their wheat in time at the capital. The English took advantage of these incidents to replace the French, especially since they sold arms and powder to the Algiers, which the Catholic countries did not do. in this regard the Dutch Republic tried to compete with the English.[99] King Henri IV had agreed with the Moriscos who asked him for weapons and experienced leaders to fight against the Spaniards. In 1604, their deputies traveled to France to conclude an agreement. But with Algiers, things weren't getting any better. Khider Pasha attacked again in 1603 the Bastion of France; and the French envoy could not obtain authorization to rebuild the establishment. A second French envoy came to Algiers accompanied by a capidji from the Porte, carrying with a firman from the sultan Ahmed I ordering the release of the French captives and the rebuilding of the Bastion. The Janissaries revolted, their diwan refused to authorize the reconstruction of the Bastion and agreed to hand over the French captives only on condition that the Muslims detained in Marseilles were to be released.[108][109]

The missions of Sanson Napollon (1628-1637)

With no peace on sight and the Algerian authorities completely ignoring the Franco-Ottoman alliance, the corso against French vessels continued, the French losses were considerable. King Louis XIII sent Captain Sanson Napollon to Algiers, who, seeing that the real power was not in Istanbul, preferred to come to an understanding with the representatives of the Raïs and the Janissaries, whose authority was indisputable. The latter demanded, above all, the release of the Turks detained in the galleys of Marseilles. The King of France ordered the levying of a contribution to pay for the redemption of the Turks, and Marseilles added a large sum to it. Sanson therefore returned to Algiers in 1628, and succeeded in obtaining a peace treaty: the Algerians undertook to respect the coast and the French ships, to prohibit in their ports the sale of goods seized on French ships; French traders could reside safely in Algiers, the French concessions of Bastion and Calle were recognized, and trade in leather and wax allowed.[110][111][112] Trade resumed and, from 1629, Sanson Napollon, who had been appointed chief of the Bastion de France, was able to offer Marseille all the wheat it needed. However, on the French side, this peace was not respected; Marseilles captured fifteen Turks whose boat had separated from their ship and who, in application of the signed peace, were to be repatriated: they were all massacred. In 1629, an Algerian ship was docked near the French Salé: the whole crew was put on the benches of the schooner and the raïs taken prisoner to France.[113]

The Rais resumed the corso against the French; they attacked the coasts of Spain, Italy, Portugal and pushed as far as England and Iceland. The Turks not seeing their compatriots captive in France return, despite the promise made to release them, made the peace treaty in fact broken. In 1634, the King of France charged Sanson Napollon, with a new mission in Algiers. He promised to exchange eight captive Turks in Marseilles for 342 Frenchmen held in Algiers. But his mission failed and the war started again.[114] In 1637, new mission of Sanson Napollon, brought with him the Turks claimed by Algiers; but he could not land at Algiers. The same year, Ali Bitchin razed the French fortress and the diwan decided that "never the said Bastion would recover, neither by request of the king of France, nor by command of the Grand Sultan, and that the first who would speak of it would lose his head". But three years later, in 1640, a new treaty restored to France its establishments in Africa, and French merchants received authorization to build at the entrance to the ports of Bastion and La Calle, and to trade in Bone and Collo; the coral fishermen obtained on their side assistance and security. In exchange for these advantages, the merchants promised to pay the Pasha a sum equivalent to nearly 17,000 pounds.[115][116]

African campaigns (1663-1665)

In 1650, the Rais operated in the very waters of Marseilles, and ravaged Corsica; in 1651 they landed near Civitavecchia and took many prisoners in the Roman countryside. The goods taken by the Algerians were sold by the merchants of Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Genoa and Livorno, which became the corsairs' broker. Spain was powerless, Sicily and the small islands of Italy were incapable of opposing the raïs any longer, France was engulfed in the wars of Fronde. However, the reaction of the Europeans was not long incoming: British Admiral Blake, the French Levant fleet, the Dutch with Michiel de Ruyter, and the Knights of Malta resumed their offensives against the Algerian fleet. In 1658, Cardinal Mazarin even gave the order to reconnoitre the Algerian coasts with a view to a permanent installation; he was advised on Bone, Jijel Collo.[99] So it was suggested to first minister of State Jean-Baptiste Colbert in 1662 the occupation of Collo and Jijel, so he mobilized large forces and directed them to occupy Collo in the spring of 1663, but the expedition ended in a failure. In July 1664, King Louis XIV directed another military campaign against Jijel, which was occupied for nearly three months, but it also ended in a defeat.[117] Despite a minor victory against Algerian vessels near Cherchell in 1655, France was forced to negotiate with Algiers and sign the May 7, 1666 agreement, which stipulated the implementation of the 1628 agreement, the release of prisoners from both sides, and the safety of the ships of both sides at sea. After the conclusion of the treaty, there was relative calm between the two countries, due to the intervention of other forces in the conflict.[118][119]

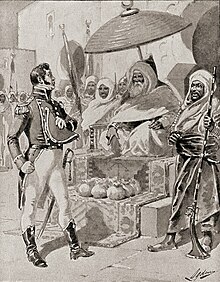

Franco-Algerian war (1681-1689)

Tied between the desires and threats from european nations, Algiers reacted by launching its fleet into the seas. The deys had to face the claims of European countries. They negotiated numerous treaties with them, often thereby asserting their autonomy in matters of foreign policy, without taking into account sovereignty of Istanbul. Very cleverly, they tried to deal with each country separately, negotiating with the French to better attack the English or the Dutch, and vice versa. For their part, the European countries endeavored to obtain advantages or economic privileges and favorable conditions for the release of their captives. They sometimes used negotiation, going so far as to supply arms to the deys, and sometimes they used intimidation like the bombardment of towns. The main relations were established and maintained with France: Louis XIV sought both to have the French flag respected in the Mediterranean, to preserve the economic advantages already obtained, and to play the role of "Most Christian King" (Rex Christianissimus) against Islamic powers, while seeing to the maintaining the French alliance with the Sublime Porte.[120] European countries tried to obtain commercial advantages from the dey Hadj Mohammed Trik (1671-1682). France tried to settle the question of the Bastion, the Spaniards of Oran tried to occupy Tlemcen and the English fleet threatened Algiers. The diwan did not yield to these intimidations: any concession was refused to the French, the Spaniards had to turn around and return to Oran in 1675, and the raïs dispersed the English ships which in 1678 threatened the city of Algiers.[121]

In 1677, following an explosion in Algiers and several attempts on his life, dey Mohammed Trik escaped to Tripoli, leaving Algiers to Baba Hassan.[122] Just one years into his rule he was already at war with one of the most powerful countries in Europe, the Kingdom of France. In 1682 France bombarded Algiers for the first time.[123] The Bombardment was inconclusive, and the leader of the fleet Abraham Duquesne failed to secure the submission of Algiers. The next year, Algiers was bombarded again, this time liberating a few slaves.[124] Before a peace treaty could be signed though, Baba Hassan was deposed and killed by a Rais called Mezzo Morto Hüseyin.[125] Continuing the war against France, the bombardments resumed, killing many victims. Mezzomorto threatened, if the firing did not cease, to put the Christian captives at the mouths of the cannons, still the bombardments continued, So he carried out his threats.[126][127] Despite this, the bombardments continued until October, but the defenders of Algiers held firm, and Duquesne had to return to Toulon. In 1684, Louis XIV sent Duquesne, then Dussault to find an agreement;[128] he had written to the sultan, who dispatched a delegation to the French squadron. After almost a month of negotiations, a treaty was signed in April 1684 which provided for numerous provisions: freedom of trade between the two countries, liberation of slaves, respect of the free passage for naval vessels, free exercise of the Christian religion, establishment of lists of products that are negotiable between the two countries, and assurance given to the dey that his ambassador in Paris could ensure compliance with the treaty.[126] But the agreement was not respected: French corsairs, encouraged by Marseille merchants, again attacked Algerian ships. The dey retaliated by arresting French nationals and even the consul, without however denouncing the treaty in 1686. The King of France supported the Marseillais and sent Marshal d'Estrées to Algiers with more than forty ships in June 1688.[129][130] The bombardment lasted several days, a good part of the city was destroyed, yet the Algerian artillery sank several french ships.[131] Hadj Hassan Mezzomorto killed more than forty Christians by cannon. The French responded by executing Muslim hostages on board. Resistance in Algiers forced Marshal d'Estrées to withdraw his fleet. The great sultan, at the request of the king of France, sent a new pasha to Algiers, but Mezzomorto did not let him disembark. In the end, however, the Janissaries revolted against Mezzomorto, whom they held responsible for the misfortunes of Algiers, forced him to flee. The pasha Hadj Chabane who replaced him (1688-1695) sent a plenipotentiary to Versailles: a peace treaty was finally signed in 1690.[132]

-

The French fleet in front of Algiers in 1682.

-

Bombardment of Algiers by the squadron of Abraham Duquesne in 1682.

-

Alger que les Français bombardent en 1682. Dutch engraving from 1689.

-

Torment of the consul of Algiers, Jean Le Vacher, in retaliation for the bombardment of Algiers by Duquesne on July 26, 1683.

-

Liberation of Christian captives in 1683 after the bombardment of Duquesne.

Relation with Other European powers

Diplomatic reciprocity was finally established in the mid-17th century. Algiers negotiated as equals with the European powers. It established diplomatic missions in Marseille and London, sent diplomatic envoys to Europe not only to address issues related to piracy, prisoners and trade, but also to conduct official state visits. Corsairing entered official diplomatic use. Henceforth, the Algerians on board their pirate ships, like their European counterparts, carried passports issued by the European diplomatic mission in Algiers to protect them from privateers and foreign cruisers. Passport also served as a basis for consular intervention to resolve profit disputes.[133] Algiers' attitude towards any European country in early modern times was undoubtedly one of the most important factors determining the rise and fall of its shipping in the Iberian Sea and the Mediterranean, Algiers was declaring war against every country with which it did not conclude treaties, foremost of which was Spain, the biggest enemy of the Algerians, and by virtue of its proximity to the Algerian coast, it became a threat to the rulers inside the regency. When a European nation is at war with Algiers, it almost inevitably means that its ships cannot compete with other shipping in the region whose the home nation is at peace with the North African Regency.[134] In fact only ships from European countries that were at peace with Algiers could expand the handling of merchant shipping in the Mediterranean, now called cabotage.[135]

After the fall of Gibraltar in the hands of the British, major changes took place in the mediterranean. Algiers appeared to change its policy, especially towards Spain, the Kingdom of Naples, and Portugal. On its part, Russia established commercial relations in the Mediterranean. It made all efforts to secure its trade against Algiers.[136] Algiers, in its peace with the European countries, has acquired many gains, especially with Spain, which required waiting several years to establish that accord. on the other hand it worked to improve its relations with some European nations while being hostile to others depending on their strength, except France and Britain, the other nations were considered of weak importance and could not handle the growing demands of the Algerians.[137]

Britain

With the accession of James I (1603-1625) to power in England, relations moved from peaceful diplomacy to maritime aggression. As an "opponent of Islam", he damaged relations with Algiers by issuing privateer licenses to his subjects, encouraging them to confiscate Muslim ships and passengers.[138] Although the Council order of 1595 recalled privateer licenses due to British privateers committing infractions and being prosecuted and sentenced in admiralty courts, they still had "a freer command over the Mediterranean, where Turkish and Algerian ships were seen as rightful prizes.[139]

In 1620, a British fleet under the command of Admiral Robert Mansell, supported by Richard Hawkins and Thomas Button, was sent to Algiers to put an end to the grips of the Barbary pirates on the trade route passing through the Strait of Gibraltar. After obtaining the release of 40 captives, following negotiations, in November 1620, Mansell took part in a second expedition in 1621 during which he sent fireships (old burnt ships) against the pirate fleet moored in the bay. This second expedition was a failure and Mansell had to withdraw, he was recalled to England on May 24, 1621.[140] this indiscretion prompted a violent revenge by the Algerian pirates: they not only raided merchant ships in the Mediterranean, but extended their piracy to the British mainland along the English Channel, passing by Years of privateering have done England more damage than Algiers, James I furthered a Treaty through the Sublime Porte, where he negotiated directly in Constantinople in 1622 with the Pasha of Algiers, who happened to be visiting there.[141]

Until 1662, no country succeeded in permanently holding the "free ship and free goods" principle from the Algerian Pirates. When England received the clause that year, the situation changed radically. Britain introduced a series of anti-counterfeiting and mandatory 'Algerian Passports' on its southbound merchant ships, guaranteeing each ship's authenticity in case it encountered Algerian pirate vessels.[142] Faced with the subsequent strong growth of the British fleet in the Mediterranean, the Algerians broke the peace twice in the following years (1668-1671, 1678-1682) and privateered wars against the British which reacted with overwhelming power every time. Two wars ended unfavorably for Algiers, one of which led to regime change in that barbary nation. When Algiers faced dangerous French attacks in the 1680s, Algiers finally opted for a lasting peace with England that would last more than 140 years.[143]

Dutch Republic

In southern European waters, Nordic shipowners made considerable profits trading for various international merchants, whether they were Armenian, Greek, Jewish, Turkish, Italian, Spanish, German or otherwise. The environment was highly contested, it was made even more intense when the French dramatically increased their shipping in the Mediterranean from the late 17th century onwards.[144] The Dutch recognized the impact of the Anglo-Algerian peace on their own shipping activities. Various reports of Armenian merchants arriving at The Hague, from the courts of Madrid or from Messina, all indicated that goods were being transferred from the Dutch to the British. Thus, from 1661 to 1663, the Republic, under the command of Michiel de Ruyter, sent several squadrons of warships to settle the matter and force the Algerians to accept a treaty of permanent peace.[145] In the ensuing decades, however, military campaigns were doomed, as the Republic was often embroiled in continental affairs that demanded attention and resources. In the long run, attempts to establish stable relations with Algiers failed. From 1679 to 1686, the Republic was able to maintain an uneasy peace with Algiers, securing a significant share of peaceful trade with southern Europe.[146] Algeria's declaration of war in 1686 affected Dutch shipping in the area. Finally, the Dutch achieved the peace they had longed for. In his first letter, the new Dutch consul in Algiers, Ludwig Hameken, cited the most important steps towards stabilizing the peace. He asked for a Mediterranean passport because Algerians "geen distinct tusschen Een Hollander weeten often Een Hamborger" (can't tell a Dutchman from a hamburger). Such documents were quickly obtained and peace became the norm. However, the end result was not as profitable as expected. When Britain went to war with Spain (1727-1729), the Dutch managed to stay ahead of their main rivals. But British traders were now too familiar with the Mediterranean to be driven away by such a brief interruption. After the war, the British shipping industry in the Mediterranean flourished, but the Dutch never kept up the competition.[147]

Scandinavian countries

Kingdom of Sweden

Algiers was really important to Swedish foreign policy in the southern waters, so the Swedish Foreign Ministry sought to gain its friendship, not out of love for Algiers or fear of its harm, as Algiers has never reached the level of danger to Sweden's national security, but the goal of its contact with Algiers was the desire to prevent its fleet from attacking Swedish merchant ships in warm waters, because the Algerian threat was affecting Sweden's economic security only, so the solution was to follow the path of other European countries, and to offer a proposal to reach an understanding that guarantees the signing of an eternal peace treaty between the two countries, which was actually done in 1729 Thus, Algiers obtained a new financier for its fleet with marine construction materials, and Sweden entered the club of tax-paying countries for Algiers, and established - following the example of the French, the English and the Dutch - a consulate in Algeria, through which a consul supervised the interests of Sweden, making this consulate the first Swedish consulate in the entire Islamic world.[148]

While the relationship was good between the two countries; There was no real cooperation between them, especially in the commercial field, although the Swedish authorities were planning to develop trade with North Africa, especially with regard to marine equipment, and the reason - according to George Lugie, the first Swedish consul in Algiers - is that the thinking of the Algerians was entirely focused on looting and piracy, as They do not encourage themselves or anyone else who tries to establish a private trade”,[149] and Lugie adds in a letter to the Swedish Chamber of Commerce dated 13 October 1738: “I can find no other way in which Algeria will be more useful to Sweden than by keeping the peace with it Peace with Algeria gives our ships the freedom to sail safely to the spanish and portugese shores as well as the rest of the mediterranean ports”[150]

Kingdom of Denmark

In the mid-1700s Dano-Norwegian trade in the Mediterranean expanded. To protect the lucrative business against piracy, Denmark–Norway secured a peace deal with the states of the Barbary Coast. It involved paying an annual tribute to the individual rulers and additionally to the states.

In 1766, Algiers had a new ruler, dey Baba Mohammed ben-Osman. He demanded that the annual payment made by Denmark-Norway be increased, and that he receive new gifts. Denmark–Norway refused the demands. Shortly after, Algerian pirates hijacked three Dano-Norwegian ships and allowed the crew to be sold as slaves.

They threatened to bombard the Algerian capital if the Algerians did not agree to a new peace deal on Danish terms. Algiers was not intimidated by the fleet, which was of two frigates, two bomb galiots and four ships of the line.

Maghrebi Wars (1678-1707)

Algeria's relations with the rest of the Maghreb countries were not as good and friendly as they should have been for several historical circumstances.[151] Algiers used to consider Tunisia a territory belonging to it by virtue of the fact that it was the one that expelled the Spaniards from it and annexed it to the Ottoman Empire which made the appointment of its pashas the prerogative of the Algerian beylerbeys, and on this basis Algiers was constantly trying to make this dependence a tangible reality, and Tunisia rejected this and saw that, like Algiers, it was subordinate to Constantinople, and more than that, Tunisia had ambitions in the Constantine region inherited from the Hafsid era.[152] As for Al-Maghreb Al-Aqsa (Morocco), it resisted from the beginning, and with determination, the Turks that sought to control it, and it began to view Algiers as a danger hanging over it and therefore it must be avoided by all means, including conspiring with any foreign power, even if it was Christian. More than this, Morocco had ancient ambitions in western Algeria and Tlemcen in particular, and its sultans did not hide this desire in all circumstances and occasions. On this basis, relations between Ottoman Algeria and its neighbors were troubled most of the time. Tunisia adamantly refused subordination to Algeria. Since 1590, the Diwan of Tunisian Odjack revolted against Algiers, and the country became a vassal of Constantinople itself.[153]

Tunisian campaigns

The Muradid War

In 1675, Murad II Bey died. he left his state to his son Mohamed Bey El Mouradi. Mohamed exiled the Pasha appointed by the Ottoman sultan, Muhammad al-Hafsi. Murad II's second son, Ali bin Murad, disappointed by his share in the division of power, had sought refuge in the Beylik of Constantine, a governorate of the Regency of Algiers.[154] He brought the tribes of northwest Tunisia led by Muhammad ben Cheker to his side with promises of gold and silver. After a short civil war in tunis between the muradid princes, the Dey of Algiers agreed to mediate between them,[155] yet the Turkish Janissaries of Tunis elected their own leader, Ahmed Chelebi who attempted to take over the country. He was defeated by the Algerians who feared that the revolutionary spirit of the Janissaries in Tunis would spread to their own country. They sacked Tunis in 1686, and left the country in ruins. Mohamed bey suspected his brother of supporting the Algerians, and thus killed him and seized power for himself. Muhammad ben Cheker (the leader of the northwestern tribes), wanted the Beylik to himself, and hearing about the infighting, he visited Algiers to negotiate with the Algerians in 1694.[155] Dey Hadj Chabane agreed to help ben Cheker in conquering Tunis, but only on condition he would subjugate himself to the dey and become an Algerian vassal. Muhammad ben Cheker agreed, and declared independence from Tunis. On June 24 Algerian troops entered Tunisian territory, and started rapidly advancing into the heartlands of Tunisia,[156] they met the Tunisian army in the Battle of Kef , which ended in a catastrophic defeat for the Tunisians and the Algerians conquered Tunis and pillaged it before occupying the country. Fed up with Muhammed bin chaker, the Tunisian population revolted and crowned Mohamed bey again, who signed an alliance with the sultan of Morocco, which would soon culminate in the Maghrebi war (1699-1701).[157]

In 1700, The Maghrebi war started, after a conducting a successful revolt against the previous bey, Murad III Bey of Tunis took the city of Constantine, but it was not long before the regency of Algiers regained the upper hand and 7000 Tunisians were killed in the Battle of Jouami' al-Ulama.[158][159] Ibrahim Cherif, the Agha of the spahis, put an end to the Muradid regime, he is named Dey by the militia and made pasha by the Ottoman sultan. However, he did not manage to put an end to the Algerian and Tripolitan incursions. Finally defeated by the Dey of Algiers in 1705 near Kef on 8 July 1705,[160][161] he was captured and taken to Algiers.

The Hussainid vassalisation

After the incessant disputes between corsairs and Janissaries to influence the government of the Ottoman regency during the 17th century, Ben Ali imposed himself in 1705 as bey of Tunis and founded the dynasty of the Hussainids under the name of Hussein I ibn Ali Bey.

After a failed revolt, Abu l-Hasan Ali I Pasha took refuge in Algiers where he managed to gain the support of the Dey.[162] The Dey of Algiers dispatched a force of 7,000 men to invade Tunis in 1735 and install Ali Pasha there as its Bey,[163] who recognised himself as a vassal of Algiers and paid an annual tribute to the Dey.[163][164]

Another campaign was directed against Tunis in 1756. Taken prisoner by the Algerians, Ali I Pasha was deposed on September 2. Brought back to Algiers in chains, he was strangled by supporters of his cousin and successor Muhammad I ar-Rashid on September 22. Algiers imposed a tribute in 1756 on Tunis, the latter had to send oil to light the mosques of Algiers each year. Tunis had become a tributary of Algiers and continued to pay an annual tribute and recognise Algerian suzerainty for more than 50 years.[165][166][167]

Moroccan campaigns

The Moroccan sovereigns had succeeded in preventing the occupation of their country by the Turks. On the other hand, they had not given up on the old Almohad dream of achieving the unity of the Maghreb for their own benefit, or at least extending their frontiers to the east into Orania region. With the advent of the Alaouite dynasty, hostilities with the regency of Algiers would resume.[168]

In 1678, Moulay Ismail mounted an expedition to Tlemcen.[169] He assembled his contingents in the Upper Moulouya, joined by the tribes of Orania (Segouna, Hamiane, Hashem) and advanced as far as the Chelif region to fight battle there.[168] The Turks of Algiers brought in the artillery, which terrified the auxiliary tribes of the Moroccan sovereign, who then broke away from him. thus Moulay Ismail ended up negotiating with Dey Chaban and fixing the border on the Moulouya,[170] which throughout the Saadian period, had separated the two countries. In 1690-1691, Moulay Ismail resumed his project and launched a new offensive against Orania. To the 22,000 Moroccan soldiers, the dey Chaban opposed 10,000 Janissaries and Zouaoua contingents. He defeated the Moroccans on the Moulouya and forced them to accept the Treaty of Oujda which confirmed the Moulouya river as the border.[171][172] In 1694, the sultan of Istanbul invited that of Morocco to cease his attacks against Algiers.[168]

Moulay Ismail's Oranian debacle