Elvis Presley: Difference between revisions

Removed becaused they are not relevant to the section |

clarification of record deals of Elvis Presley |

||

| Line 225: | Line 225: | ||

By 1967, Colonel Tom Parker had negotiated a contract that gave him 50% of Presley's earnings. Parker's excessive gambling—and his subsequent need to have Presley signed up to commercially lucrative contracts—may well have adversely affected the course of Presley's career.<ref>http://archives.tcm.ie/businesspost/2002/08/18/story343531628.asp. Retrieved on 2008-07-30.</ref> Parker's concerns about his own U.S. citizenship (he was a Dutch immigrant) may have also been a factor in Parker and the singer never exploiting Presley's popularity abroad (see: '[[#1973–1976|1973–1976]]'). It has been claimed that Presley's original band was fired in order to isolate the singer: Parker wanted no one close to Presley to suggest that a better management deal might exist.<ref>Dickerson, ''Colonel Tom Parker: The Curious Life of Elvis Presley's Eccentric Manager''</ref> |

By 1967, Colonel Tom Parker had negotiated a contract that gave him 50% of Presley's earnings. Parker's excessive gambling—and his subsequent need to have Presley signed up to commercially lucrative contracts—may well have adversely affected the course of Presley's career.<ref>http://archives.tcm.ie/businesspost/2002/08/18/story343531628.asp. Retrieved on 2008-07-30.</ref> Parker's concerns about his own U.S. citizenship (he was a Dutch immigrant) may have also been a factor in Parker and the singer never exploiting Presley's popularity abroad (see: '[[#1973–1976|1973–1976]]'). It has been claimed that Presley's original band was fired in order to isolate the singer: Parker wanted no one close to Presley to suggest that a better management deal might exist.<ref>Dickerson, ''Colonel Tom Parker: The Curious Life of Elvis Presley's Eccentric Manager''</ref> |

||

As well as signing Presley to RCA Victor, Parker also cut a deal with Hill and Range Publishing Company to create |

As well as signing Presley to RCA Victor, Parker also cut a deal with Hill and Range Publishing Company to create two separate entitities—"Elvis Presley Music, Inc" and "Gladys Music"—to handle all of Presley's songs and accrued royalties. The owners of Hill & Range, The Aberbachs, would share publishing and royalties rights with each song 50/50 with Elvis. It was up to Hill & Range, Elvis and Colonel Parker's partners in their publishing companies to make deals with the songwriters. It was their job to convince any songwriter they did not control, or publisher with a song Elvis wanted to record, that it was worthwhile to give up one third of the mechanical royalties in exchange for Elvis to record their song. <ref>Ernst Jorgensen, ''Elvis Presley, A Life In Music, The Complete Recording Sessions, pages 36, 54''</ref> |

||

Presley apparently disliked several songs—even some of the earliest top sellers he became famous for (which suggests commercial influences were sometimes greater than his own desires). Presley's friend Jerry Schilling relates that one way to really annoy the singer was to play a song, like "All Shook Up", on a jukebox at one of his private parties. "Get that crap off," was his typical reaction.<ref name=Schilling>Schilling, Jerry (2006-07-10). "[http://www.elvis.com.au/presley/books/book_me_and_a_guy_named_elvis2.shtml Why I Wrote Me And A Guy Named Elvis]". ''elvis.com.au''. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.</ref> |

|||

In 1969, record producer [[Chips Moman]] and Presley recorded with Moman's own musicians at his American Sound Studios in Memphis. Given the control exerted by RCA and the music publishers, this was a significant departure. Moman still had to deal with Hill and Range staff on site and was not happy with their song choices. Moman could only get the best out of the singer when he threatened to quit the sessions and asked Presley to remove the "aggravating" publishing personnel from the studio.<ref>Clayton and Heard, p.264-5</ref> RCA Victor executive Joan Deary was later full of praise for the song choices and superior results of Moman's work, like "[[In the Ghetto]]" and "[[Suspicious Minds]]", but despite this, no producer was to override Hill and Range's control again.<ref>Clayton and Heard, p.267</ref> |

In 1969, record producer [[Chips Moman]] and Presley recorded with Moman's own musicians at his American Sound Studios in Memphis. Given the control exerted by RCA and the music publishers, this was a significant departure. Moman still had to deal with Hill and Range staff on site and was not happy with their song choices. Moman could only get the best out of the singer when he threatened to quit the sessions and asked Presley to remove the "aggravating" publishing personnel from the studio.<ref>Clayton and Heard, p.264-5</ref> RCA Victor executive Joan Deary was later full of praise for the song choices and superior results of Moman's work, like "[[In the Ghetto]]" and "[[Suspicious Minds]]", but despite this, no producer was to override Hill and Range's control again.<ref>Clayton and Heard, p.267</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:49, 29 June 2009

Elvis Presley |

|---|

Elvis Aaron Presley[1][4] (January 8, 1935 – August 16, 1977; middle name sometimes spelled Aron)Template:Fn was an American singer, actor, and musician. A cultural icon, he is commonly known simply as Elvis and is also sometimes referred to as "The King of Rock 'n' Roll" or "The King."

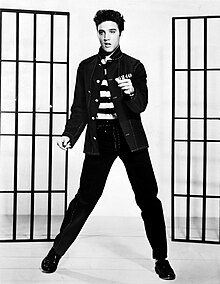

Presley began his career in 1953 as one of the first performers of rockabilly, an uptempo fusion of country and rhythm and blues with a strong back beat. His novel versions of existing songs, mixing "black" and "white" sounds, made him popular—and controversial[5][6][7]—as did his uninhibited stage and television performances. He recorded songs in the rock and roll genre, with tracks like "Hound Dog" and "Jailhouse Rock" later embodying the style. Presley had a versatile voice[8] and had unusually wide success encompassing other genres, including gospel, blues, country, ballads and pop. To date, he has been inducted into four music halls of fame.

In the 1960s, Presley made the majority of his 31 movies, most of which were poorly reviewed but financially successful musicals.[9] In 1968, he returned to live music in a television special,[10] and performed across the U.S., notably in Las Vegas. In 1973, Presley staged the first global live concert via satellite (Aloha from Hawaii), reaching at least one billion viewers live and an additional 500 million on delay.[11]

Throughout his career, he set records for concert attendance, television ratings and recordings sales.[12] He is one of the best-selling and most influential artists in the history of music. Health problems, drug addiction[13] and other factors led to his death at age 42.

Biography

Early life

Elvis Presley owed his ancestry to diverse European ethnic strains, primarily British and German; Presley's lineage also included some Cherokee descent.[14][15][16][17] His father, Vernon Elvis Presley[18] (April 10, 1916 – June 26, 1979), had several low-paying jobs, including sharecropping and working as a truck driver. His mother, Gladys Love Smith (April 25, 1912 – August 14, 1958) worked as a sewing machinist. They met in Tupelo, Mississippi, and eloped to Pontotoc County where they married on June 17, 1933.[19]

Presley was born in a two-room shotgun house, built by his father, in East Tupelo. He was an identical twin; his brother was stillborn and given the name Jesse Garon. Growing up as an only child he "was, everyone agreed, unusually close to his mother."[18] The family lived just above the poverty line and attended an Assembly of God church.[20] Vernon has been described as "a malingerer, always averse to work and responsibility."[21] His wife was "voluble, lively, full of spunk" and had a fondness for drink.[22] In 1938, Vernon was jailed for an eight dollar check forgery. During his eight-month incarceration, Gladys and her son lost the family home, and they moved in with relatives.[22][23][24]

In September 1942, Presley entered first grade at Lawhorn School in Tupelo.[23] He was considered a "well-mannered and quiet child",[23] but sometimes classmates threw "things at him — rotten fruit and stuff — because he was different... he stuttered and he was a mama's boy."[25]

On October 3, 1945, he made his first public performance in a singing contest at the Mississippi-Alabama Fair and Dairy Show at the suggestion of his teacher, Mrs. J.C. Grimes.[23] Dressed as a cowboy, Presley had to stand on a chair to reach the microphone and sang Red Foley's "Old Shep." He came fifth, winning $5 and a free ticket to all the Fair rides.[26]

In 1946, for his eleventh birthday, Presley received his first guitar.[27] He wanted a bicycle or rifle for his birthday, but his parents could only afford a guitar.[23][28] Over the following year, Vernon's brother, Vester, gave Elvis basic guitar lessons.[23] In September 1948, the family moved to Memphis, Tennessee,[23] allegedly because Vernon—in addition to needing work—had to escape the law for transporting bootleg liquor.[24][29] In 1949, they lived at Lauderdale Courts, a public housing development in one of Memphis' poorer sections. Presley practiced playing guitar in the laundry room and also played in a five-piece band with other tenants.[30] One resident, another future rockabilly pioneer, Johnny Burnette, recalled, "Wherever Elvis went he'd have his guitar slung across his back... [H]e'd go in to one of the cafes or bars... Then some folks would say: 'Let's hear you sing, boy.'"[31] Presley enrolled at L. C. Humes High School where some fellow students viewed his performing unfavorably; one recalled that he was "a sad, shy, not especially attractive boy" whose guitar playing was not likely to win any prizes. Presley was made fun of as a 'trashy' kind of boy, playing 'trashy' hillbilly music."[32] Other children however, "would beg him" to sing, but he was apparently too shy to perform.[33]

In September 1950, Presley occasionally worked evenings as an usher at Loew's State Theater—his first job—to boost the family income,[34][35] but his mother made him quit as she feared it was affecting his school work. He worked again at Loew's in June the following year, but was fired after a fistfight over a female employee.[34] He began to grow his sideburns and, when he could afford to, dress in the wild, flashy clothes of Lansky Brothers on Beale Street.[36] He stood out, especially in the conservative Deep South of the 1950s, and was mocked and bullied for it.[30] Childhood friend Red West said: "In the sea of 1600 pink-scalped kids at school, Elvis stood out like a camel in the arctic. ... [but] ... his appearance expressed a defiance which his demeanor did not match..."[37] Despite any unpopularity or shyness, he was a contestant in his school's 1952 "Annual Minstrel Show"[30] and won by receiving the most applause. His prize was to sing encores, including "Cold Cold Icy Fingers" and "Till I Waltz Again With You".[31]

After graduation, Presley was still a rather shy "kid who had spent scarcely a night away from home".[38] His third job was driving a truck for the Crown Electric Company. He began wearing his hair longer with a ducktail;the style of truck drivers at that time.[39]

Early musical influences

Initial influences originated from his family's attendance at the Assembly of God.[18] Rolling Stone wrote: "Gospel pervaded Elvis' character and was a defining and enduring influence all of his days."[40] Presley himself stated: "Since I was two years old, all I knew was gospel music. That music became such a part of my life it was as natural as dancing. A way to escape from the problems. And my way of release."[41] Throughout his life—in the recording studio, in private, or after concerts—Presley joined with others singing and playing gospel music at informal sessions.[42] The Southern Gospel singer Jake Hess was reputedly Presley's favorite singer and was a significant influence on his singing style.[43]

The young Presley frequently listened to local radio; his first musical hero was family friend Mississippi Slim, a hillbilly singer with a radio show on Tupelo’s WELO. Presley performed occasionally on Slim’s Saturday morning show, Singin’ and Pickin’ Hillbilly. "He was crazy about music... That’s all he talked about," recalls his sixth grade friend, James Ausborn, Slim’s younger brother.[44] Before he was a teenager, music was already Presley’s "consuming passion".[44] J. R. Snow, son of 1940s country superstar Hank Snow, recalls that even as a young man Presley knew all of Hank Snow’s songs, "even the most obscure".[45] Presley himself said: "I loved records by Sister Rosetta Thorpe, ... Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubbs, Ted Daffan, Jimmie Rodgers, Jimmy Davis and Bob Wills."[46]

In Memphis, Presley went to record stores that had jukeboxes and listening booths, playing old records and new releases for hours on end. He was an audience member at the all-night white—and black—"gospel sings" downtown.[47] Memphis Symphony Orchestra concerts at Overton Park were another Presley favorite, along with the Metropolitan Opera. His small record collection included Mario Lanza and Dean Martin. Presley later said: "I just loved music. Music period."[44]

Memphis had a strong tradition of blues music and Presley frequented blues as well as hillbilly venues. Many of his future recordings were inspired by local African American composers and recording artists, including Arthur Crudup and Rufus Thomas.[48] B.B. King has recalled that he knew Presley before he was popular when they both used to frequent Beale Street.[49]

Presley "was an untrained musician who played [guitar and piano] entirely by ear. 'I don't read music,' he confessed, 'but I know what I like.' ... Because he was not a songwriter, Presley [would] rarely [have] material prepared for recording sessions..." When later, as a young singer, he "ventured into the recording studio he was heavily influenced by the songs he had heard on the jukebox and radio."[50]

First recordings and performances

On July 18, 1953, Presley went to Sun Records' Memphis Recording Service to record "My Happiness" with "That's When Your Heartaches Begin," supposedly a present for his mother.[51] During his initial introduction at Sun Records, assistant Marion Keisker asked him who he sounded like. Presley replied: "I don't sound like nobody." On January 4, 1954, he cut a second acetate. At the time, Sun Records boss Sam Phillips was on the lookout for someone who could deliver a blend of black blues and boogie-woogie music; he thought it would be very popular among white people.[52] When Phillips acquired a demo recording of "Without You" and was unable to identify the vocalist, Keisker reminded him about the young truck driver. She called him on June 26, 1954. Presley was not able to do justice to the song.[53] Phillips would later recall that "Elvis was probably as nervous as anybody, black or white, that I had seen in front of a microphone."[54] Despite this, Phillips invited local musicians Winfield "Scotty" Moore and Bill Black to audition Presley. Though they were not overly impressed, a studio session was planned.[55]

During a recording break, Presley began "acting the fool" first with Arthur Crudup's "That's All Right (Mama)".[56] Phillips quickly got them all to restart, and began taping. This was the sound he had been looking for.[57] The group recorded other songs, including Bill Monroe's "Blue Moon of Kentucky." After the session, according to Scotty Moore, Bill Black remarked: "Damn. Get that on the radio and they'll run us out of town."[58]

"That's All Right" was aired on July 8, 1954, by DJ Dewey Phillips.[59]Template:Fn Listeners to the show began phoning in, eager to find out who the singer was.[54] The interest was such that Phillips played the demo fourteen times.[54] During an interview on the show, Phillips asked Presley what high school he attended—to clarify Presley's color for listeners who assumed he must be black.[54] The first release of Presley's music featured "That's All Right" and "Blue Moon of Kentucky". With Presley's version of Monroe's song consistently rated higher, both sides began to chart across the South.[60]

Moore and Black began playing regularly with Presley. They gave performances on the July 17 and July 24, 1954 to promote the Sun single at the Bon Air, a rowdy music club in Memphis, where the band was not well-received.[61] On July 30 the trio, billed as The Blue Moon Boys, made their first paid appearance at the Overton Park Shell, with Slim Whitman headlining.[62] A nervous Presley's legs were said to have shaken uncontrollably during this show: his wide-legged pants emphasized his leg movements, apparently causing females in the audience to go "crazy."[63] Scotty Moore claims it was just the natural way he moved and had nothing to do with "nerves."[64] Presley consciously incorporated similar movements into future shows.[65] Elvis himself said that, "I didn't realize that my, that I was movin', my body was movin'. It was a natural thing to me."[66]

Deejay and promoter Bob Neal became the trio's manager (replacing Scotty Moore). Moore and Black left their band, the Starlight Wranglers and, from August through October 1954, appeared with Presley at The Eagle's Nest.[61] Presley debuted at the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville on October 2; Hank Snow introduced Presley on stage. He performed "Blue Moon of Kentucky" but received only a polite response. Afterwards, the singer was supposedly told by the Opry's Jim Denny: "Boy, you’d better keep driving that truck,"[67] though others deny it was Denny who made that statement.[68] Country music promoter and manager Tillman Franks booked Presley for October 16 on KWKH-AM's Louisiana Hayride. Before Franks saw Presley, he referred to him as "that new black singer with the funny name".[69] During Presley's first set, the reaction was muted; Franks then advised Presley to "Let it all go!" for the second set. House drummer D.J. Fontana (who had worked in strip clubs) complemented Presley's movements with accented beats. Bill Black also took an active part in encouraging the audience, and the crowd became more responsive.[70][71]

According to one source, regarding Presley's engagements from that time, "Audiences had never before heard [such] music... [or] seen anyone who performed like Presley either. The shy, polite, mumbling boy gained self-confidence with every appearance... People watching the show were astounded and shocked, both by the ferocity of his performance, and the crowd’s reaction to it... Roy Orbison saw Presley for the first time in Odessa, Texas: 'His energy was incredible, his instinct was just amazing... I just didn’t know what to make of it. There was just no reference point in the culture to compare it.'"[72] Sam Phillips said Presley "put every ounce of emotion ... into every song, almost as if he was incapable of holding back."[73]

By August 1955, Sun Studios had released ten sides, credited to "Elvis Presley, Scotty and Bill," all typical of the developing Presley style which seemed hard to categorize; he was billed or labeled in the media as "The King of Western Bop," "The Hillbilly Cat" and "The Memphis Flash."[74]

On August 15, 1955, "Colonel" Tom Parker became Presley's manager, signing him to a one year contract, plus renewals.[75] Several record labels had shown interest in signing Presley and, by the end of October 1955, three major labels had made offers up to $25,000.[76] On November 21, 1955, Parker and Phillips negotiated a deal with RCA Victor Records to acquire Presley's Sun contract for an unprecedented $40,000, $5,000 of which was a bonus for the singer for back royalties owed to him by Sun Records[76][77] (Presley, at 20, was officially still a minor, so his father had to sign the contract).[78] By December 1955, RCA had begun to heavily promote its newest star, and by the month's end had re-released all of his Sun recordings.[76]

1956 breakthrough

On January 10, Presley made his first recordings for RCA in Nashville, Tennessee.[79] The session produced "Heartbreak Hotel/I Was The One" which was released on January 27. The public reaction to "Heartbreak Hotel" prompted RCA to release it as a single in its own right (February 11).[79] By April it had hit number one in the U.S. charts, selling in excess of one million copies.

On March 3, 1955, Presley made his first television appearance on the TV version of Louisiana Hayride on KSLA-TV, but failed an audition for Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts on CBS-TV later that month. To increase the singer's exposure, Parker finally brought Presley to national television after booking six appearances on CBS's Stage Show in New York, beginning January 28, 1956. Presley was introduced on the first program by Cleveland DJ Bill Randle. He stayed in town and on January 30, he and the band headed for the RCA's New York Studio.[79] The sessions yielded eight songs, including "My Baby Left Me" and "Blue Suede Shoes". The latter was the only hit single from the collection, but the recordings marked the point at which Presley started moving away from the raw, pure Sun sound to the more commercial and mainstream sound RCA had envisioned for him.[79]

On March 23, RCA Victor released Elvis Presley, his first album. Like the Sun recordings, the majority of the tracks were country songs.[80] The album went on to top the pop album chart for 10 weeks.[79]

On April 1, Presley launched his acting career with a screen test for Paramount Pictures. His first motion picture, Love Me Tender, was released on November 21 (See 'Acting career').

Parker had also obtained a deal for two lucrative appearances on NBC-TV's The Milton Berle Show. Presley first appeared from the deck of the USS Hancock in San Diego on April 3. His performance was cheered by a live audience of appreciative sailors and their dates.[81] A few days after, a flight taking Presley's band to Nashville for a recording session left all three badly shaken (the plane lost an engine and almost went down over Texas).[81]

From April 23, Presley was scheduled to perform four weeks at the New Frontier Hotel and Casino on the Las Vegas Strip—billed this time as "the Atomic Powered Singer" (since Nevada was the home of the U.S.'s atomic weapons testing, Parker thought the name would be catchy). His shows were so badly received by critics and the conservative, middle-aged guests, that Parker cut short the engagement from four weeks to two.[82] D.J. Fontana said, "I don't think the people there were ready for Elvis..... We tried everything we knew. Usually Elvis could get them on his side. It didn't work that time". While in Vegas, Presley saw Freddie Bell and the Bellboys live, and liked their version of Leiber and Stoller's "Hound Dog". By May 16, he had added the song to his own act.[83]

After more hectic touring, Presley made his second appearance on The Milton Berle Show (June 5). Whilst delivering an uptempo version of "Hound Dog" (without his guitar), he then stopped, and immediately after began performing a slower version.[84] Presley's "gyrations" during this televised version of "Hound Dog" created a storm of controversy—even eclipsing the "communist threat" headlines prevalent at the time.[6] The press described his performance as "vulgar" and "obscene".[6][85] The furor was such that Presley was pressured to explain himself on the local New York City TV show Hy Gardner Calling: "Rock and roll music, if you like it, and you feel it, you can't help but move to it. That's what happens to me. I have to move around. I can't stand still. I've tried it, and I can't do it."[86] After this performance he was dubbed "Elvis the Pelvis". Presley disliked the name, calling it "one of the most childish expressions I ever heard."[87]

The Berle shows drew such huge ratings that Steve Allen (NBC), not a fan of rock and roll, booked him for one appearance in New York on July 1. Allen wanted "to do a show the whole family can watch" and introduced a "new Elvis" in white bow tie and black tails. Presley sang "Hound Dog" for less than a minute to a Basset Hound in a top hat. According to one author, "Allen thought Presley was talentless and absurd... [he] set things up so that Presley would show his contrition..."[88][89] In his book "Hi-Ho Steverino!" Allen wrote the following: "When I booked Elvis, I naturally had no interest in just presenting him vaudeville-style and letting him do his spot as he might in concert. Instead we worked him into the comedy fabric of our program. We certainly didn't inhibit Elvis' then-notorious pelvic gyrations, but I think the fact that he had on formal evening attire made him, purely on his own, slightly alter his presentation."[90] The day after (July 2), the single "Hound Dog" was recorded and Scotty Moore said they were "all angry about their treatment the previous night".[89] (Presley often referred to the Allen show as the most ridiculous performance of his career.)[86] A few days later, Presley made a "triumphant" outdoor appearance in Memphis at which he announced: "You know, those people in New York are not gonna change me none. I'm gonna show you what the real Elvis is like tonight."[91]

Country vocalists The Jordanaires accompanied Presley on The Steve Allen Show and their first recording session together produced "Any Way You Want Me", "Don't Be Cruel" and "Hound Dog". The Jordanaires would work with the singer through the 1960s.

Though Presley had been unhappy, Allen's show had, for the first time, beaten The Ed Sullivan Show in the ratings, causing a critical Sullivan (CBS) to book Presley for three appearances for an unprecedented $50,000.[92]

Presley's first Ed Sullivan appearance (September 9, 1956) was seen by some 55–60 million viewers. Biographer Greil Marcus has written: "Compared to moments on the Dorsey shows and on the Berle show, it was ice cream."[93] On the third Sullivan show, in spite of Presley's established reputation as a "gyrating" performer, he sang only slow paced ballads and a gospel song.[94] Presley was nevertheless only shown to the television audience 'from the waist up', as if to censor the singer. Marcus claims he "stepped out in the outlandish costume of a pasha, if not a harem girl", and was shot in close up during this last broadcast, as if Sullivan had tried to 'bury' the singer.[95] It was also claimed that Colonel Parker had himself orchestrated the 'censorship' merely to generate publicity.[96][97] In spite of any misgivings about the controversial nature of his performing style (see 'Sex symbol'), Sullivan declared at the end of the third appearance that Presley was "a real decent, fine boy" and that they had never had "a pleasanter experience" on the show.[97]

On December 4, Presley dropped into Sun Records where Carl Perkins and Jerry Lee Lewis were recording.[98] Sam Phillips made sure the session of the three performing was recorded; the results would later appear on a bootlegged recording titled The Million Dollar Quartet in 1977 (Johnny Cash is often thought to have performed with the trio, but he was only present briefly at Phillips' instigation for a photo opportunity).[99] RCA would eventually iron out legal difficulties and release an authorized version a few years later.[98]

On December 29, Billboard revealed that Presley had placed more songs in the Top 100 than any other artist since record charts began.[98][100] This news was followed by a front page report in the Wall Street Journal on December 31, that suggested Presley merchandise had grossed more than $22 million in sales.[101]

Controversy and cultural impact

When "That's All Right" was played, many listeners were sure Presley must be black, prompting white disc-jockeys to ignore his Sun singles. However, black disc-jockeys did not want anything to do with any record they knew was made by a white man.[102] To many black adults, Presley had undoubtedly "stolen" or at least "derived his style from the Negro rhythm-and-blues performers of the late 1940s",[103] though such criticism ignored Presley's use of "white" musical styles. Some black entertainers, notably Jackie Wilson, argued: "A lot of people have accused Elvis of stealing the black man’s music, when in fact, almost every black solo entertainer copied his stage mannerisms from Elvis."[104]Template:Fn

By the spring of 1956, Presley was becoming popular nationwide and teenagers flocked to his concerts. Scotty Moore recalled: "He’d start out, 'You ain’t nothin’ but a Hound Dog,' and they’d just go to pieces. They’d always react the same way. There’d be a riot every time."[105] Bob Neal wrote: "It was almost frightening, the reaction... from [white] teenage boys. So many of them, through some sort of jealousy, would practically hate him." In Lubbock, Texas, a teenage gang fire-bombed Presley's car.[106] Some performers became resentful (or resigned to the fact) that Presley's unmatched hustle onstage before them would "kill" their own act; he thus rose quickly to top billing.[106] At the two concerts he performed at the 1956 Mississippi-Alabama Fair and Dairy Show, fifty National Guardsmen were added to the police security to prevent crowd trouble.[107]

To many white adults, the singer was "the first rock symbol of teenage rebellion. ... they did not like him, and condemned him as depraved. Anti-Negro prejudice doubtless figured in adult antagonism. Regardless of whether parents were aware of the Negro sexual origins of the phrase 'rock 'n' roll', Presley impressed them as the visual and aural embodiment of sex."[108] In 1956, a critic for the New York Daily News wrote that popular music "has reached its lowest depths in the 'grunt and groin' antics of one Elvis Presley" and the Jesuits denounced him in their weekly magazine, America.[109] Even Frank Sinatra opined: "His kind of music is deplorable, a rancid smelling aphrodisiac. It fosters almost totally negative and destructive reactions in young people."[110] Presley responded to this (and other derogatory comments Sinatra made) by saying: "I admire the man. He has a right to say what he wants to say. He is a great success and a fine actor, but I think he shouldn't have said it... This ... [rock and roll] ... is a trend, just the same as he faced when he started years ago."[111]

According to the FBI files on the singer, Presley was even seen as a "definite danger to the security of the United States." His actions and motions were called "a strip-tease with clothes on" or "sexual self-gratification on stage." They were compared with "masturbation or riding a microphone." Some saw the singer as a sexual pervert, and psychologists feared that teenaged girls and boys could easily be "aroused to sexual indulgence and perversion by certain types of motions and hysteria—the type that was exhibited at the Presley show."[112] Presley would insist, however, that there was nothing vulgar about his stage act, saying: "Some people tap their feet, some people snap their fingers, and some people sway back and forth. I just sorta do ‘em all together, I guess."[113] In August 1956, a Florida judge called Presley a "savage" and threatened to arrest him if he shook his body while performing in Jacksonville. The judge declared that Presley's music was undermining the youth of America. Throughout the performance (which was filmed by police), he kept still as ordered, except for wiggling a finger in mockery at the ruling.[114] (Presley recalls this incident during the '68 Comeback Special.)

In 1957, despite Presley's demonstrable respect for "black" music and performers,[115] he faced accusations of racism. He was alleged to have said in an interview: "The only thing Negro people can do for me is to buy my records and shine my shoes." An African American journalist at Jet magazine subsequently pursued the story. On the set of Jailhouse Rock, Presley denied saying, or ever wanting to make, such a racist remark. The Jet journalist found no evidence that the remark had ever been made, but did find testimony from many individuals indicating that Presley was anything but racist.[116] Despite the remark being wholly discredited at the time, it was still being used against Presley decades later.[117]

Military service and mother's death

| Rank and Insignia | Date of Rank |

|---|---|

| Drafted 24 March 1958 | |

Private First-Class Private First-Class

|

27 November 1958 |

Specialist 4 Specialist 4

|

1 June 1959 |

Sergeant Sergeant

|

20 January 1960 |

On December 20, 1957, Presley received his draft notice. Hal Wallis and Paramount Pictures had already spent $350,000 on the film King Creole, and did not want to suspend or cancel the project. The Memphis Draft Board granted Presley a deferment to finish it. On March 24, 1958, he was inducted as US Army private #53310761 at Fort Chaffee near Fort Smith, Arkansas. Two Army officers Arlie Metheny and John J. Mawn, coordinated the entry and shielded Presley from bombardment by national media and free-lance photographers.[118] Presley completed basic training at Fort Hood, Texas, on September 17, 1958, before being posted to Friedberg, Germany, with the 3rd Armored Division, where his service took place from October 1, 1958 until March 2, 1960.[119]

Fellow soldiers have attested to Presley's wish to be seen as an able, ordinary soldier, despite his fame, and to his generosity while in the service. To supplement meager under-clothing supplies, Presley bought an extra set of fatigues for everyone in his outfit. He also donated his Army pay to charity, and purchased all the TV sets for personnel on the base at that time.[120]

Presley had chosen not to join "Special Services", which would have allowed him to avoid certain duties and maintain his public profile.[121] He continued to receive massive media coverage, with much speculation echoing Presley's own concerns about his enforced absence damaging his career. However, early in 1958, RCA Victor producer Steve Sholes and Freddy Bienstock of Hill and Range (Presley's main music publishers) had both pushed for recording sessions and strong song material, the aim being to release regular hit recordings during Presley's two-year hiatus.[122] Hit singles duly followed during Presley's army service, like "One Night", "I Got Stung" and "(Now and Then There's) A Fool Such as I", as did hit albums of old material, including Elvis' Golden Records and A Date With Elvis.

As Presley's fame grew, his mother continued to drink excessively and began to gain weight. She had wanted her son to succeed, "but... [the] hysteria of the crowd frightened her."[123] In early August 1958, doctors had diagnosed hepatitis and her condition worsened. Presley was granted emergency leave to visit her, arriving in Memphis on August 12. Two days later, Gladys Presley died of heart failure, aged forty-six. Presley was heartbroken, "grieving almost constantly" for days.[124]

Some months later, in Germany, "[a] sergeant had introduced [Presley] to amphetamines when they were on maneuvers at Grafenwöhr... it seemed like half the guys in the company were taking them." Friends around Presley, like Diamond Joe Esposito, also began taking them, "if only to keep up with Elvis, who was practically evangelical about their benefits."[44] The Army also introduced Presley to karate—something which he studied seriously, even including it in his later live performances.[125]Template:Fn

Presley returned to the U.S. on March 2, 1960, and was honorably discharged with the rank of sergeant on March 5.[126] Any doubts Elvis had about his popularity must have been dispelled as "The train which carried him from New Jersey to Memphis was mobbed all the way, with Presley being called upon to appear ... at whistle-stops" to placate his fans.[127]

First post-Army recordings

The first recording session, on March 20, 1960, was attended by all of the significant businessmen involved with Presley; none had heard him sing for two years, and there were inevitable concerns about him being able to recapture his previous success.[128] The session was the first at which Presley was recorded using a three-track machine, allowing better quality, postsession remixing and stereophonic recording.[128] This, and a further session in April, yielded some of Presley's best-selling songs. "It's Now or Never" ended with Presley "soaring up to an incredible top G sharp ... pure magic."[129] His voice on "Are You Lonesome Tonight?" has been described as "natural, unforced, dead in tune, and totally distinctive."[129] Although some tracks were uptempo, none could be described as "rock and roll", and many of them marked a significant change in musical direction.[129] Most tracks found their way on to an album—Elvis is Back!—described by one critic as "a triumph on every level... It was as if Elvis had... broken down the barriers of genre and prejudice to express everything he heard in all the kinds of music he loved".[130] The album was also notable because of Homer Boots Randolph's acclaimed saxophone playing on the blues songs "Like A Baby" and "Reconsider Baby", the latter being described as "a refutation of those who do not recognize what a phenomenal artist Presley was."[129]

Acting career

In 1956, Presley launched his career as a film actor. He screen-tested for Paramount Pictures by lip-synching "Blue Suede Shoes" and performing a scene as 'Bill Starbuck' in The Rainmaker.[131] Despite being quietly confident that The Rainmaker would be his first film—even going as far as saying so in an interview[132]—the role eventually went to Burt Lancaster.[131]

After signing a seven-year contract with Paramount, Presley made his big-screen début with the musical western, Love Me Tender. It was panned by the critics but did well at the box office.[133] The original title—The Reno Brothers—was changed to capitalize on the advanced sales of the song "Love Me Tender". The majority of Presley's films were musical comedies made to "sell records and produce high revenues."[134] He also appeared in more dramatic films, like Jailhouse Rock and King Creole. The erotic, if not homoerotic,[135] dance sequence to the song "Jailhouse Rock", which Presley choreographed himself, "is considered by many as his greatest performance ever captured on film."[136] To maintain box office success, he would later even shift "into beefcake formula comedy mode for a few years."[137] He also made one non-musical western, Charro!.

Presley stopped live performing after his Army service with the exception, ironically—given Sinatra's previously scathing criticism—of a guest appearance on The Frank Sinatra Timex Show: Welcome Home Elvis (1960). He also performed three charity concerts—two in Memphis and one in Pearl Harbor (1961).[138]

In the Army, Presley had said on many occasions that "more than anything, he wanted to be taken seriously as a dramatic actor."[139] His manager had negotiated the multi-picture seven-year contract with Hal Wallis with an eye on long-term earnings.[140] The singer would later star alongside several established or up-and-coming actors, including Walter Matthau, Carolyn Jones, Angela Lansbury, Charles Bronson, Barbara Stanwyck, Mary Tyler Moore—and even a very young Kurt Russell in his screen debut. Although Presley was praised by directors, like Michael Curtiz, as polite and hardworking (and as having an exceptional memory), "he was definitely not the most talented actor around."[141] Others were more charitable; critic Bosley Crowther of the New York Times said: "This boy can act," about his portrayal in King Creole. Director Joe Pasternak believed "Elvis should be given more meaty parts. ... He would be a good actor. He should do more important pictures."[142]

Presley's movies were generally poorly received, with one critic dismissing them as a "pantheon of bad taste."[143] The scripts of his movies "were all the same, the songs progressively worse."[144] For Blue Hawaii, "fourteen songs were cut in just three days."[145] Julie Parrish, who appeared in Paradise, Hawaiian Style, says that Presley hated many of the songs chosen for his films; he "couldn't stop laughing while he was recording" one of them.[146] Others noted that the songs seemed to be "written on order by men who never really understood Elvis or rock and roll."[147] Sight and Sound wrote that in his movies "Elvis Presley, aggressively bisexual in appeal, knowingly erotic, [was] acting like a crucified houri and singing with a kind of machine-made surrealism."[148] However, several reputable songwriters/partnerships contributed soundtrack songs, including Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Don Robertson, Sid Tepper and Roy C. Bennett, and Otis Blackwell and Winfield Scott. Whatever the quality of the material, some observers have argued that Presley generally sang well in the studio, with commitment, and always played with distinguished musicians and backing singers.[149] Despite this, critics maintained that "No major star suffered through more bad movies than Elvis Presley."[150]

Presley movies were nevertheless very popular, and he "became a film genre of his own."[151] Hal Wallis would later remark: "An Elvis Presley picture is the only sure thing in Hollywood."[152] Elvis on celluloid was the only chance for his worldwide fans to see him, in the absence of live appearances (the only time he toured outside of the U.S. was in Canada in 1957).Template:Fn His Blue Hawaii even "boosted the new state's tourism. Some of his most enduring and popular songs came from those [kind of] movies," like "Can't Help Falling in Love," "Return to Sender" and "Viva Las Vegas."[153] His 1960s films and soundtracks grossed some $280 million.[154] On December 1, 1968, the New York Times wrote: "Three times a year Elvis Presley ... [makes] multimillion-dollar feature-length films, with holiday titles like Blue Hawaii, Fun in Acapulco, Viva Las Vegas, Tickle Me, Easy Come, Easy Go, Live a Little, Love a Little and The Trouble With Girls. For each film, Elvis receives a million dollars in wages and 50 per cent of the profits. ... [E]very film yields an LP sound-track record which may sell as many as two-million copies."

In 1964, Richard Burton and Peter O'Toole had starred in Hal Wallis' acclaimed Becket. Wallis admitted to the press that the financing of such quality productions was only possible by making a series of profitable B-movies starring Presley. Elvis branded Wallis "a double-dealing sonofabitch" (and he thought little better of Tom Parker), realizing there had never been any intention to let him develop into a serious actor.[155]

Presley was similarly exploited the following year with the film Tickle Me. Allied Artists had serious financial problems and hoped a Presley film would help them "stay afloat".[156] By agreeing to a lower fee, using previously recorded songs and filming on the studio back-lot, Allied Artists were able to keep costs very low.[156] Considered one of the weakest of all Presley pictures, it became the third highest grossing picture in Allied Artists' history, and saved them from bankruptcy at the time.[156]

By the late sixties, the Hippie movement had developed and musical acts like Jefferson Airplane, Sly and the Family Stone, Grateful Dead, The Doors and Janis Joplin were dominating the airwaves.[157] Priscilla Presley recalls: "He blamed his fading popularity on his humdrum movies" and "... loathed their stock plots and short shooting schedules." She also notes: "He could have demanded better, more substantial scripts, but he didn't."[158]

Change of Habit (1969) was the singer's final movie role. His last two films were concert documentaries in the early 1970s, though Presley was keen to consider dramatic movie roles.[159] (See: 'Influence of Colonel Parker and others').

As well as the formulaic movie songs of the 1960s, Presley added to the studio recordings of Elvis Is Back, by recording other noteworthy songs like "She's Not You", "Suspicion," "Little Sister", "(You're the) Devil in Disguise" and "It Hurts Me." In 1966 he recorded a cover of Bob Dylan's "Tomorrow is a Long Time" (which RCA Victor relegated to a bonus track on the soundtrack album for Spinout). He also produced two gospel albums: His Hand in Mine (1960) and How Great Thou Art (1966). In 1967, he recorded some well-received singles, like Guitar Man, by songwriter/guitar player Jerry Reed. However, "during the Beatles era (1963-70), only six Elvis singles reached number ten or better. 'Suspicious Minds' was the lone number one."[160]

Marriage to Priscilla

Elvis and Priscilla met in 1959 at a party in Bad Nauheim, Germany during his stay in the army.[54] She was 14 at the time, while he was 24. They quickly began a romantic relationship and were frequently together until Elvis left Germany in 1960. In her autobiography, Elvis and Me, Priscilla says that Elvis refused to have sex with her until they were married. However, biographer Suzanne Finstad writes that Priscilla and Elvis slept together on their second date, and that she wasn't a virgin when she met him.[161] Priscilla later filed a lawsuit against Currie Grant for his claim in Finstad's book that he had sex with her in exchange for introducing her to Presley and won. However, neither Finstad nor her publisher were a party to the lawsuit, and Finstad says she stands by the account in her book.

Priscilla and Elvis stayed in contact over the phone, though they would not see each other again until the summer of 1962, when Priscilla's parents agreed to let her visit for two weeks.[54][162] After another visit at Christmas, Priscilla's parents finally let her move to America for good.[54] Part of the agreement was that she would be privately educated, to complete her senior year, and live with Elvis' father and his wife, Dee, in their home—due to Presley's difficulty with accepting his stepmother, he arranged for them to live in a separate house on the Graceland estate. Priscilla's parents allowed her to live at Graceland only if Elvis promised to eventually marry her.[54] However, it wasn't long until Priscilla was moved into Graceland to live with Elvis.[54]

Shortly before Christmas 1966, Elvis proposed to Priscilla. They married on May 1, 1967 at the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas after an eight-year courtship. In typical fashion, Colonel Parker had arranged a photo session and press conference to be conducted shortly after the ceremony.[163] According to Finstad, this marriage was part of a mastermind for fame hatched by Priscilla and her mother.

Their only child, Lisa Marie, was born on February 1, 1968.

Sex symbol

Presley's sexual appeal and photogenic looks have been acknowledged: for example, director Steve Binder, not a fan of Presley's music at the time, recalled from the '68 Comeback Special (when Presley was fit and tanned): "I'm straight as an arrow and I got to tell you, you stop, whether you're male or female, to look at him. He was that good looking. And if you never knew he was a superstar, it wouldn't make any difference; if he'd walked in the room, you'd know somebody special was in your presence."[164]

According to Marjorie Garber, a "male rock critic writing in 1970 praised Elvis as 'The master of the sexual simile, treating his guitar as both phallus and girl.' ... rumor had it that into his skin-tight jeans was sewn a lead bar to suggest a weapon of heroic proportions." She cites a boyhood friend of Presley's who claims the singer actually used a cardboard toilet roll tube to make it "look to the girls up front like he had one helluva thing there inside his pants."[165] Ed Sullivan had apparently heard similar rumors and instructed his director Marlo Lewis to film only Presley's chest and head for his final Sullivan appearance. However, Lewis was skeptical about Presley wearing such a device and says simply: "It wasn't there".[166]

Accounts of Presley's numerous sexual conquests may be exaggerated.[167][168] Cybill Shepherd reveals that Presley kissed her all over her naked body - but refused to have oral sex with her.[169] Ex-Girlfriends Judy Spreckels and June Juanico had no sexual relationships with Presley. Byron Raphael and Alanna Nash have stated that the star "would never put himself inside one of these girls..."[170] Cassandra Peterson ("Elvira") says she knew Presley for only one night, but all they did was talk.[171] Cher regrets turning him down when he asked her to stay with him in Las Vegas, because she was too nervous of spending the night with him.[172] Peggy Lipton claims that he was "virtually impotent" with her, but she attributed this to his boyishness and drug misuse.[173] Guralnick concurs with others, "he wasn't really interested", preferring to lie in bed, watch television and talk.[174]

Ann-Margret (Presley's co-star in Viva Las Vegas) refers to Presley as her "soulmate" but has revealed little else.[175] A publicity campaign about Presley and Margret's romance was launched during the filming of Viva Las Vegas,[176] which helped to increase Margret's popularity.[177][178] Presley apparently dated many female co-stars for publicity purposes.[179] Lori Williams dated him for a while in 1964. She says their "courtship was not some bizarre story. It was very sweet and Elvis was the perfect gentleman."[180]

Former partner Linda Thompson says they did not consummate their relationship until after a few months of dating. After they broke up in December 1976, many say Presley never had sex again.[181] His last girlfriend, Ginger Alden claims that she was engaged to Presley at the time of his death, but this is disputed.[182]

"The Fab Four" meet "The King"

During filming of Paradise, Hawaiian Style, Presley returned to his Bel Air home. The Beatles were at the end of their second U.S. tour. Colonel Parker had been negotiating a meeting for some time, through The Beatles' manager Brian Epstein, though Parker simply saw it as a valuable publicity opportunity (he had apparently even tried to get the group and Presley to perform the closing song in the same movie, but The Beatles' film contract precluded it[citation needed]). The group arrived in Bel Air amid a flurry of elaborate security arrangements made by Parker at 10pm, on August 27, 1965.[183] The visit lasted about four hours. Many of Presley's closest and trusted friends— members of the so-called "Memphis Mafia"—were present, including school friend and bodyguard Red West, Marty Lacker, Jerry Schilling, Larry Geller and their girlfriends.[183]

Biographer Peter Guralnick maintains that Presley was at best "lukewarm" about playing host to people he did not really know, and it took a while for everyone to feel comfortable.[183] Paul McCartney later said: "It was one of the great meetings of my life. I think he liked us. I think at that time, he may have felt a little bit threatened, but he didn't say anything. We certainly didn't feel any antagonism. I only met him that once, and then I think the success of our career started to push him out a little, which we were very sad about, because we wanted to coexist with him."[184]

Marty Lacker recalls Presley saying: "'Quite frankly, if you guys are going to stare at me all night, I'm going to bed. I thought we'd talk a while and maybe jam a little.' And when he said that, they [The Beatles] went nuts."[185] The group told stories, joked and listened to records. The five of them had an impromptu jam session.[184] "They all went to the piano," says Lacker, "and Elvis handed out a couple of guitars. And they started singing Elvis songs, Beatle songs, Chuck Berry songs. Elvis played Paul's bass part on "I Feel Fine", and Paul said something like, 'You're coming along quite promising on the bass there, Elvis.' I remember thinking later, 'Man, if we'd only had a tape recorder.'"[185]

Ringo Starr played pool with two others that night; George Harrison "looked to most of the guys to be stoned" on arrival and allegedly smoked a joint with Larry Geller and talked about Hinduism (see: 'Influence of Colonel Parker and others'). Parker played roulette with Epstein.[183] However, Guralnick claims The Beatles were, overall, disappointed by the visit. They still reciprocated with an invitation for Elvis to visit them, but only some of Presley's "Memphis Mafia" accepted. "John Lennon went out of his way to tell Jerry [Schilling] how much the evening had meant to him" and asked Schilling to tell Presley, "'[I]f it hadn't been for him I would have been nothing.'" Schilling says that when he told Presley he did not say anything, but "just kind of smiled."[186] (See: '1970–1972)').

Influence of Colonel Parker and others

By 1967, Colonel Tom Parker had negotiated a contract that gave him 50% of Presley's earnings. Parker's excessive gambling—and his subsequent need to have Presley signed up to commercially lucrative contracts—may well have adversely affected the course of Presley's career.[187] Parker's concerns about his own U.S. citizenship (he was a Dutch immigrant) may have also been a factor in Parker and the singer never exploiting Presley's popularity abroad (see: '1973–1976'). It has been claimed that Presley's original band was fired in order to isolate the singer: Parker wanted no one close to Presley to suggest that a better management deal might exist.[188]

As well as signing Presley to RCA Victor, Parker also cut a deal with Hill and Range Publishing Company to create two separate entitities—"Elvis Presley Music, Inc" and "Gladys Music"—to handle all of Presley's songs and accrued royalties. The owners of Hill & Range, The Aberbachs, would share publishing and royalties rights with each song 50/50 with Elvis. It was up to Hill & Range, Elvis and Colonel Parker's partners in their publishing companies to make deals with the songwriters. It was their job to convince any songwriter they did not control, or publisher with a song Elvis wanted to record, that it was worthwhile to give up one third of the mechanical royalties in exchange for Elvis to record their song. [189]

In 1969, record producer Chips Moman and Presley recorded with Moman's own musicians at his American Sound Studios in Memphis. Given the control exerted by RCA and the music publishers, this was a significant departure. Moman still had to deal with Hill and Range staff on site and was not happy with their song choices. Moman could only get the best out of the singer when he threatened to quit the sessions and asked Presley to remove the "aggravating" publishing personnel from the studio.[190] RCA Victor executive Joan Deary was later full of praise for the song choices and superior results of Moman's work, like "In the Ghetto" and "Suspicious Minds", but despite this, no producer was to override Hill and Range's control again.[191]

According to life-long friend and "Memphis Mafia" member George Klein, over the years Presley was offered lead roles in the film Midnight Cowboy and in West Side Story. Robert Mitchum personally offered him the lead in Thunder Road.[192] In 1974, Barbra Streisand approached Presley to star with her in the remake of A Star is Born. In each case, any ambitions the singer may have had to play such parts were thwarted by his manager's negotiating demands, or his flat refusals.[159]

Marty Lacker regarded Parker as a "hustler and scam artist" who abused Presley's trust, but Lacker acknowledged that Parker was a master promoter.[193] Priscilla Presley noted that "Elvis detested the business side of his career. He would sign a contract without even reading it."[194]

Presley's father in turn distrusted Lacker and the other members of the "Memphis Mafia"; he thought they collectively exercised an unhealthy influence over his son.[195] "[I]t was no wonder" that as the singer "slid into addiction and torpor, no one raised the alarm: to them, Elvis was the bank, and it had to remain open."[196] Musician Tony Brown noted the urgent need to reverse Presley's declining health as the singer toured in the mid-1970s. "But we all knew it was hopeless because Elvis was surrounded by that little circle of people... all those so-called friends and... bodyguards."[197] In the "Memphis Mafia"'s defence, Marty Lacker has said: "[Presley] was his own man. ... If we hadn't been around, he would have been dead a lot earlier."[198]

Larry Geller became Presley's hairdresser in 1964. Unlike others in the "Memphis Mafia", Geller was interested in 'spiritual studies', and was subsequently viewed with suspicion and scorn by the singer's manager and friends.[199] From their first conversation, Geller recalls how Presley revealed his secret thoughts and anxieties, how "there's got to be a reason... why I was chosen to be Elvis Presley.'"[199] He then poured out his heart in "an almost painful rush of words and emotions," telling Geller about his mother and the hollowness of his Hollywood life, things he could not share with anyone around him. Thereafter, Presley voraciously read books Geller supplied, on religion and mysticism. Perhaps most tellingly, he revealed to Geller: "I swear to God, no one knows how lonely I get and how empty I really feel."[200] Presley would be preoccupied by such matters for much of his life, taking trunkloads of books with him on tour.[201]

1968 comeback

In 1968, even Presley's version of Jerry Reed's hook-laden "Guitar Man" had failed to enter the U.S. Top 40. He continued to issue movie soundtrack albums that sold poorly compared to those of films like Blue Hawaii from 1961. It had also been nearly six years since the single "Good Luck Charm" had topped the Billboard Hot 100.[202]

Presley was, by now, "profoundly" unhappy with his career.[155] Colonel Parker's plans once again included television, and he arranged for Presley to appear in his own special. The singer had not been on television since Frank Sinatra's Timex special in May of 1960.[202] Parker shrewdly manoeuvred a deal with NBC's Tom Sarnoff which included the network's commitment to financing a future Presley feature film—something that Parker had found increasingly difficult to secure.[202]

The special was made in June, but was first aired on December 3, 1968 as a Christmas telecast called simply Elvis. Later dubbed the '68 Comeback Special by fans and critics, the show featured some lavishly staged studio productions. Other songs however, were performed live with a band in front of a small audience—Presley's first live appearance as a performer since 1961. The live segments saw Presley clad in black leather, singing and playing guitar in an uninhibited style—reminiscent of his rock and roll days. Rolling Stone called it "a performance of emotional grandeur and historical resonance."[40] Jon Landau in Eye magazine remarked: "There is something magical about watching a man who has lost himself find his way back home. He sang with the kind of power people no longer expect of rock 'n' roll singers. He moved his body with a lack of pretension and effort that must have made Jim Morrison green with envy."[10] Its success was helped by director and co-producer, Steve Binder, who worked hard to reassure the nervous singer[164] and to produce a show that was not just an hour of Christmas songs, as Colonel Parker had originally planned.[203][204]

By January, 1969, one of the key songs written specifically for the special, "If I Can Dream", reached number 12.[202] The soundtrack of the special also broke into the Top 10. On December 4, when the TV ratings were released, NBC reported that Presley had captured 42 percent of the total viewing audience. It was the network's number one rated show that season.[202]

Jerry Schilling recalls that the special reminded Presley about what "he had not been able to do for years, being able to choose the people; being able to choose what songs and not being told what had to be on the soundtrack. ... He was out of prison, man." Steve Binder said of Presley's reaction: "I played Elvis the 60-minute show, and he told me in the screening room, "Steve, it's the greatest thing I've ever done in my life. I give you my word I will never sing a song I don't believe in."[202]

Buoyed by the experience, Presley engaged in the prolific series of recording sessions at American Sound Studios, which led to the acclaimed From Elvis in Memphis (Chips Moman was its uncredited producer).[205] It was followed by From Memphis To Vegas/From Vegas To Memphis, a double-album. The same sessions lead to the hit singles "In the Ghetto", "Suspicious Minds", "Kentucky Rain" and "Don't Cry Daddy".

Return to live performances

In 1969, Presley was keen to resume regular live performing. Following the success of Elvis, many new offers came in from around the world.[206] The London Palladium offered Parker $28,000 for a one week engagement. He responded: "That's fine for me, now how much can you get for Elvis?"[206] By May, the brand new International Hotel in Las Vegas announced that it had booked Presley; he was scheduled to perform from July 31, after Barbra Streisand opened the new venue.[206]

Presley duly delivered fifty-seven shows over four weeks at the hotel, which had the largest showroom in the city. He had assembled some of the finest musicians—including an orchestra—and some of the best soul/gospel back-up singers available.[206]

Despite such a prestigious backing, Presley was nervous; his only other engagement in Las Vegas (1956) had been a disaster, critically. Parker therefore promoted the singer's appearances heavily; he rented billboards and took out full-page advertisements in local and trade papers. The lobby of the International displayed Presley souvenirs; records, T-shirts, straw boaters and stuffed animals. Parker intended to make Presley's return the show business event of the year, and hotel owner Kirk Kerkorian planned to send his own plane to New York to fly in the rock press for the debut performance.[206]

Presley took to the stage with no introduction. The audience—which included Pat Boone, Fats Domino, Wayne Newton, Dick Clark, Ann-Margret, George Hamilton, Angie Dickinson, and Henry Mancini—gave him a standing ovation before he sang one note.[206] After a well-received performance, he returned to give an encore, of "Can't Help Falling in Love", and was given his third standing ovation[206] Backstage, many well-wishers, including Cary Grant, congratulated Presley on his triumphant return which, in the showroom alone, had generated over $1,500,000.[206]

Newsweek commented: "There are several unbelievable things about Elvis, but the most incredible is his staying power in a world where meteoric careers fade like shooting stars."[207] Rolling Stone magazine declared Presley to be "supernatural, his own resurrection", while Variety proclaimed him a "superstar".[54] At a press conference after his opening show, when a reporter referred to him as "The King", Presley pointed to Fats Domino, standing at the back of the room. "No," he said, "that’s the real king of rock and roll."[208]

The next day, Parker's negotiations with the hotel resulted in a five-year contract for Presley to play each February and August, at a salary of $1 million per year.[206]

1970–1972

In January 1970, Presley returned to the International Hotel for a month-long engagement, performing two shows a night. RCA recorded some shows and the best material appeared on the album On Stage - February 1970.[209] In late February, Presley performed six more attendance-breaking shows at the Houston Astrodome in Texas.[210] In August at the International Hotel, MGM filmed rehearsal and concert footage for a documentary: Elvis - That's The Way It Is. He wore a jumpsuit—a garment that would become a trademark of Presley's live performances in the 1970s. Although he had new hit singles in many countries, some were critical of his song choices and accused him of being distant from trends within contemporary music.[211]

Around this time Presley was threatened with kidnapping at the International Hotel. Phone calls were received, one demanding $50,000; if unpaid, Presley would be killed by a "crazy man". The FBI took the threat seriously and security was stepped up for the next two shows. Presley went on stage with a Derringer in his right boot and a .45 in his waistband, but nothing untoward transpired.[212][213] (The singer had had many threats of varying degrees since the fifties, many of them made without the singer's knowledge).[214]

After closing his Las Vegas engagement on September 7, Presley embarked on his first concert tour since 1958. Feeling exhausted, Presley spent a month relaxing and recording before touring again in October and November.[215] He would tour extensively in the U.S. up to his death; many of the 1,145 concerts setting attendance records.

On December 21, 1970, Presley met with President Richard Nixon at the White House (Presley arrived with a gift—a handgun. It was accepted but not presented for security reasons). Presley had engineered the encounter to express his patriotism, his contempt for the hippie drug culture and his wish to be appointed a "Federal Agent at Large". He also wished to obtain a Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs badge to add to similar items he had begun collecting. He offered to "infiltrate hippie groups" and claimed that The Beatles had "made their money, then gone back to England where they fomented anti-American feeling."[216] Nixon was uncertain and bemused by their encounter, and twice expressed his concern to Presley that the singer needed to "retain his credibility".[216][217] Ringo Starr later said he found it very sad to think Presley held such views. "This is Mr. Hips, the man, and he felt we were a danger. I think that the danger was mainly to him and his career." Paul McCartney said also that he "felt a bit betrayed ... The great joke was that we were taking drugs, and look what happened to [Elvis]. ... It was sad, but I still love him. ..."[218]

On January 16, 1971 Presley was named 'One of the Ten Outstanding Young Men of the Nation' by the U.S. Junior Chamber of Commerce (The Jaycees).[219] That summer, the City of Memphis named part of Highway 51 South "Elvis Presley Boulevard",[219].

In April 1972, MGM again filmed Presley, this time for Elvis on Tour, which won a 1972 Golden Globe for Best Documentary. A fourteen-date tour started with an unprecedented four consecutive sold-out shows at Madison Square Garden, New York. RCA taped the shows for a live album. After the tour, Presley released the 1972 single "Burning Love"—his last top ten hit in the U.S. charts.

Divorce from Priscilla

Off stage, Presley had continuing problems. He and Priscilla became increasingly distant due to Elvis being on the road so much. It was widely reported that he had cheated on her both before and after they married. In spite of his own infidelity, Presley was furious that Priscilla was having an affair with a mutual acquaintance—Mike Stone, a karate instructor she had met in 1971 backstage at one of Presley's concerts.[54] It was Presley himself who first suggested Priscilla should take lessons from Stone.[54] Once the news of their affair came to his attention, he raged obsessively: "There's too much pain in me... Stone [must] die."[220] A bodyguard, Red West, felt compelled to get a price for a contract killing and was relieved when Presley decided: "Aw hell... Maybe it's a bit heavy..."[221]

The Presleys separated on February 23, 1972 after 13 years together. Elvis filed for legal separation in August 1972, and then filed for divorce in January 1973. In the following months, Priscilla visited Elvis in Las Vegas where she claims that he forced himself upon her in his hotel room and said "This is how a real man makes love to a woman.".[222] They were divorced on October 9, 1973, agreeing to share custody of their daughter.

Following his separation from Priscilla, he lived with Linda Thompson, a songwriter and one-time Memphis beauty queen, from July 1972 until just a few months before his death.[223] Following their breakup, he had a relationship with Ginger Alden, who has said that they were engaged.

1973: Aloha from Hawaii

In January 1973, Presley performed two charity concerts in Hawaii for the Kui Lee cancer foundation (The singer made many other charitable donations throughout his adult life. He also quietly paid hospital bills, bought cars, homes, supported families, paid off debts, etc., for friends, family and total strangers).[224]. The first concert (January 12) was primarily a practice run for the main show which was broadcast live on January 14 (The first show also served as a backup if technical problems affected the live broadcast). The "Aloha from Hawaii" concert was the world's first live concert satellite broadcast, reaching at least a billion viewers live and a further 500 million on delay. The show's album went to number one and spent a year in the charts.[225] The album also proved to be Presley's last U.S. Number One album during his lifetime.

1973–1976

After his divorce in 1973, Presley became increasingly unwell, with prescription drugs affecting his health, mood and his stage act. His diet had always been unhealthy, and he now had significant weight problems.[226] He overdosed twice on barbiturates, spending three days in a coma in his hotel suite after the first.[201] According to Dr. George C. Nichopoulos, Presley's main physician, the singer was "near death" in November 1973 because of side effects of Demerol addiction. Nichopoulos notes that the subsequent hospital admission "was crazy", because of the enormous attention Presley attracted, and the measures necessary to protect his medical details. Lab technicians were even exploiting Presley's ill-health by selling samples of his blood and urine.[227]

In his book, Elvis: The Final Years, Jerry Hopkins writes: "Elvis' health plummeted as his weight ballooned." At a University of Maryland concert on September 27 (1974), band members "had trouble recognizing him. ... 'He walked on stage and held onto the mike for the first thirty minutes like it was a post. Everybody was scared.' Guitarist John Wilkinson ... recalled, ... 'He was all gut. He was slurring. ... It was obvious he was drugged, that there was something terribly wrong with his body. It was so bad, the words to the songs were barely intelligible. ... We were in a state of shock.' "

Despite this, his "thundering" live version of "How Great Thou Art" won him a Grammy award in 1974.[228] Presley won three competitive "Grammies" for his gospel recordings: "How Great Thou Art"—the album, as well as the single—and for the album He Touched Me (1972). (He had fourteen nominations during his career, though it has been claimed that "Elvis has never been adequately appreciated by those who give the Grammies.")[229]

In April 1974, rumors began that he would actually be playing overseas after years of offers.[230] A $1,000,000 bid came in from a source in Australia for him to tour there, but Colonel Parker was uncharacteristically reluctant to accept such large sums. This prompted those closest to Presley to speculate about Parker's past and circumstances, and the reasons for his apparent unwillingness to apply for a passport to travel abroad. He set aside any notions Presley had of overseas work by citing poor security in other countries, and the lack of suitable venues for a star of his status. Presley apparently accepted such excuses, at the time.[230]

Presley continued to play to sell-out crowds in the U.S.; a 1975 tour ended with a concert in Pontiac, Michigan, attended by over 62,000 fans. However the singer now had "no motivation to lose his extra poundage... he became self-conscious... his self-confidence before the audience declined... Headlines such as 'Elvis Battles Middle Age' and 'Time Makes Listless Machine of Elvis' were not uncommon."[231] According to Marjorie Garber, when Presley made his later appearances in Las Vegas, he appeared "heavier, in pancake make-up... with an elaborate jewelled belt and cape, crooning pop songs to a microphone ... [He] had become Liberace. Even his fans were now middle-aged matrons and blue-haired grandmothers, ... Mother's Day became a special holiday for Elvis' fans."[232]

On July 13, 1976, Presley's father fired "Memphis Mafia" bodyguards Red West, Sonny West and David Hebler. All three were taken by surprise, especially the Wests, who had been with Presley since the beginning of his career.[233] Presley was away in Palm Springs when it happened, and some suggest the singer was too cowardly to face them himself.[234] Vernon Presley cited the need to "cut back on expenses" when dismissing the three, but David Stanley has claimed they were really fired because of becoming more outspoken about Presley's drug dependency.[235] A "trusted associate" of Presley, John O'Grady, also stated, in agreement with Parker and Vernon Presley, that the bodyguards "were too rough with the fans... resulting in a lot of unnecessary lawsuits" and lawyers' fees.[234] The Wests and Hebler would later write a devastating indictment of Presley, notably his drug-taking, in the book: Elvis: What Happened?, published August 1, 1977.[236]

Almost throughout the 1970s, Presley's recording label had been increasingly concerned about making money from Presley material: RCA Victor often had to rely on live recordings because of problems getting him to attend studio sessions. A mobile studio was occasionally sent to Graceland in the hope of capturing an inspired vocal performance. Once in a studio, he could lack interest or be easily distracted; often this was linked to his health and drug problems.[217]

Final year and death

It has been suggested that this article should be split into a new article titled Death of Elvis Presley. (discuss) (June 2009) |

In 2006, a journalist recalled: "Elvis Presley had [in 1977] become a grotesque caricature of his sleek, energetic former self... he was barely able to pull himself through his abbreviated concerts."[237] In Alexandria, Louisiana, the singer was on stage for less than an hour and "was impossible to understand."[238] In Baton Rouge, Presley failed to appear: he was unable to get out of his hotel bed, and the rest of the tour was cancelled.[238] In Knoxville, Tennessee on May 20, "there was no longer any pretence of keeping up appearances. The idea was simply to get Elvis out on stage and keep him upright..."[239] Despite his obvious problems, shows in Omaha, Nebraska and Rapid City, South Dakota were recorded for an album and a CBS-TV special: Elvis In Concert.[240]

In Rapid City, "he was so nervous on stage that he could hardly talk... He was undoubtedly painfully aware of how he looked, and he knew that in his condition, he could not perform any significant movement."[241] His performance in Omaha "exceeded everyone's worst fears... [giving] the impression of a man crying out for help..."[240] According to Guralnick, fans "were becoming increasingly voluble about their disappointment, but it all seemed to go right past Elvis, whose world was now confined almost entirely to his room and his [spiritualism] books."[239] A cousin, Billy Smith, recalled how Presley would sit in his room and chat, recounting things like his favorite Monty Python sketches and his own past japes, but "mostly there was a grim obsessiveness... a paranoia about people, germs... future events", that reminded Smith of Howard Hughes.[242]

The book Elvis: What Happened? was the first exposé to detail Presley's years of drug misuse, and was apparently the authors' revenge for them being sacked, and, too, a plea to get Presley to recognize the extent of his drug problems.[243] The singer "was devastated by the book. Here were his close friends who had written serious stuff that would affect his life. He felt betrayed."[244]

Presley's final performance was in Indianapolis at the Market Square Arena, on June 26, 1977. According to many of his entourage who accompanied him on tour, it was the "best show he had given in a long time" with "some strong singing".[54]

Another tour was scheduled to begin August 17, 1977, but at Graceland the day before, Presley was found on his bathroom floor by fiancée, Ginger Alden. According to the medical investigator, Presley had "stumbled or crawled several feet before he died"; he had apparently been using the toilet at the time.[245] Death was officially pronounced at 3:30 pm at the Baptist Memorial Hospital.

Before his funeral, hundreds of thousands of fans, the press and celebrities lined the streets and many hoped to see the open casket in Graceland. One of Presley's cousins, Bobby Mann,[54] accepted $18,000 to secretly photograph the corpse; the picture duly appeared on the cover of the National Enquirer, making it the largest and fastest selling issue of all time.[246] Two days after the singer's death, a car plowed into a group of 2000 fans outside Presley's home, killing two women and critically injuring a third.[247] Among the mourners at the funeral were Ann-Margret (who had remained close to Presley) and his ex-wife.[248] U.S. President Jimmy Carter issued a statement (See 'Legacy').[249]

On Thursday, August 18, following a funeral service at Graceland,[54] Elvis Presley was buried at Forest Hill Cemetery in Memphis, next to his mother. After an attempt to steal the body on August 28,[54] and with no signs of security concerns at the cemetery abating,[54] his—and his mother's—remains were reburied at Graceland in the Meditation Garden in October.[54]

Presley had developed many health problems during his life, some of them chronic.[250] Opinions differ regarding the onset of his drug abuse. He did take amphetamines regularly in the army; it has been claimed that pills of some form were first given to him by Memphis DJ Dewey Phillips,[251] but Presley's friend Lamar Fike has said: "Elvis got his first uppers from what he stole from his mother. Gladys was given Dexedrine to help her with her 'change of life' problems."[226] Priscilla Presley saw "problems in Elvis' life, all magnified by taking prescribed drugs." Presley's physician, Dr. Nichopoulos, has said: "[Elvis] felt that by getting [pills] from a doctor, he wasn't the common everyday junkie getting something off the street. He... thought that as far as medications and drugs went, there was something for everything."[201]

According to Guralnick: "[D]rug use was heavily implicated... no one ruled out the possibility of anaphylactic shock brought on by the codeine pills... to which he was known to have had a mild allergy." In two lab reports filed two months later, each indicated "a strong belief that the primary cause of death was polypharmacy," with one report "indicating the detection of fourteen drugs in Elvis' system, ten in significant quantity."[252]