Indian painting: Difference between revisions

→Murals: Deleted part removed to miniatures Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

==Murals== |

==Murals== |

||

[[File:Meister des Mahâjanaka Jâtaka 001.jpg|thumb|A mural painting depicting a scene from [[Jataka tales|Mahajanaka Jataka]], Cave 1, [[Ajanta Caves|Ajanta]]]] |

[[File:Meister des Mahâjanaka Jâtaka 001.jpg|thumb|A mural painting depicting a scene from [[Jataka tales|Mahajanaka Jataka]], Cave 1, [[Ajanta Caves|Ajanta]]]] |

||

The earliest Indian paintings were the rock paintings of pre-historic times, the petroglyphs as found in places like Bhimbetka rock shelters. Some are approximately 30,000 years old. |

|||

The [[Cave paintings in India|history of Indian murals]] in the Historical Era starts in ancient and early medieval times, from the 2nd century BCE to 8th – 10th century CE. There are known more than 20 locations around India containing murals from this period, mainly natural caves and rock-cut chambers. The highest achievements of this time are the caves of [[Ajanta Caves|Ajanta]], [[Bagh Caves|Bagh]], [[Sittanavasal]], [[Armamalai Cave]] (Tamil Nadu), Ravan Chhaya rock shelter, Kailasanatha temple in [[Ellora Caves]]. |

The [[Cave paintings in India|history of Indian murals]] in the Historical Era starts in ancient and early medieval times, from the 2nd century BCE to 8th – 10th century CE. There are known more than 20 locations around India containing murals from this period, mainly natural caves and rock-cut chambers. The highest achievements of this time are the caves of [[Ajanta Caves|Ajanta]], [[Bagh Caves|Bagh]], [[Sittanavasal]], [[Armamalai Cave]] (Tamil Nadu), Ravan Chhaya rock shelter, Kailasanatha temple in [[Ellora Caves]]. |

||

Revision as of 13:21, 20 August 2019

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (July 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of India |

|---|

|

Indian painting has a very long tradition and history in Indian art. The earliest Indian paintings were the rock paintings of pre-historic times, the petroglyphs as found in places like Bhimbetka rock shelters, some of the Stone Age rock paintings found among the Bhimbetka rock shelters are approximately 30,000 years old.[1]

India's Buddhist literature is replete with examples of texts which describe palaces of the army and the aristocratic class embellished with paintings, but the paintings of the Ajanta Caves are the most significant of the few survivals. Smaller scale painting in manuscripts was probably also practised in this period, though the earliest survivals are from the medieval period.

Mughal painting represented a fusion of the Persian miniature with older Indian traditions, and from the 17th century its style was diffused across Indian princely courts of all religions, each developing a local style.

Company paintings were made for British clients under the British raj, which from the 19th century also introduced art schools along Western lines, leading to modern Indian painting, which is increasingly returning to its Indian roots.

Indian paintings provide an aesthetic continuum that extends from the early civilization to the present day. From being essentially religious in purpose in the beginning, Indian painting has evolved over the years to become a fusion of various cultures and traditions.

Indian Painting – Indian Art

Indian art consists of a variety of art forms, including painting, sculpture, pottery, and textile arts such as woven silk. The origin of Indian art can be traced to pre-historic settlements in the 3rd millennium BCE.

On its way to modern times, Indian art has had cultural influences, as well as religious influences such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and Islam.

In spite of this complex mixture of religious traditions, the prevailing artistic style at any time and place has been shared by the major religious groups.

See also: Indian Art

Vocabulary

- The mural exists under the Hindi name Bhitti Chitra ( Bhitti = wall, Chitra = painting)[2].

- The painting on the floor is called Bhumi Chitra or Rangoli

- The painting on fabrics is called Patta Chitra or Potchitro (Pot = roll)

- The painting on the bodies is called Deh Chitra or Gudna

- The manuscript painting (miniature) is called Chitra Bhagwat

- The meditative painting is called mandala

- "Kalam" means pen, brush or "school of ..."

Shadanga – The Six Limbs of Indian Painting

Around the 1st century BCE the Shadanga or Six Limbs of Indian Painting, were evolved, a series of canons laying down the main principles of the art.[3] Vatsyayana, who lived during the third century A.D., enumerates these in his Kamasutra having extracted them from still more ancient works.[4] · [5].

These 'Six Limbs' have been translated as follows:[3]

- Rupabheda The knowledge of appearances.

- Pramanam Correct perception, measure and structure.

- Bhava Action of feelings on forms.

- Lavanya Yojanam Infusion of grace, artistic representation.

- Sadrisyam Similitude.

- Varnikabhanga Artistic manner of using the brush and colours.

The subsequent development of painting by the Buddhists indicates that these ' Six Limbs ' were put into practice by Indian artists, and are the basic principles on which their art was founded.

The Shadanga was extended by Abanindranath Tagore with two more limbs:[6]

7. Rasa The quintessence of taste

8. Chanda Rhythm.

The images and the Gods

During the prehistoric period (from 26,000 BCE) the rock painting was without religious significance. Throughout the Vedic period (around the 15th century BCE to the 5th century BCE) India seems to be without pictures.

The beginnings of Buddhism (5th century BCE to 3rd century BCE) reveal the same reluctance to representations. In the first Buddhist art (3rd century BCE to 1st century BCE) the Buddha is still evoked only through symbols. The oldest Buddhist iconography carved out of stone today (3rd century BCE to 2nd century BCE) does not show the Buddha, but the very absence of the master, for example in the form of an empty throne. It was only around the 1st century BCE. that appear the first anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha.

The evolution that begins in the beginning of our era is striking. At about the same time, between the first century and the third century, it affects the three great religions born in India, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. From this time on, it becomes necessary to embody in a tangible form the Buddha, the Jina or the Hindu gods. This affirmation of the embodied, "manifested" dimension, inseparable from the transcendent character of "Great Beings" or the gods, will enable Indian art to give free rein to all its expressive possibilities.

The superiority of Buddhism until the 5th century goes hand in hand with the progress of narrative art. In Sânchî, on the stupas of Gandhara (now in Pakistan) or of Andhra Pradesh, in the caves of Ajanta, the succession of scenes restores in its temporal dimension the historical life of the Buddha as well as his previous existences.

From the 8th century, partly influenced by Hinduism, Buddhist art turned away from narrative cycles to attach more and more to the world of mythical representations. The Buddha appears almost now only in its timeless dimension, through the image of worship, encompassed in the pantheon of Buddhas and cosmic Bodhisattvas. Buddhist art left its mark on the whole of Hindu art until the virtual disappearance of Buddhism in the 10th century before the expansion of Hinduism and Islam.

In Vedic Hinduism (15th century BCE to the 5th century BCE), Hindu deities were probably not revered as images or icons, but already imagined and even represented in a human form, as the mention of a painted representation of Rudra in the Rig-Veda. The Hinduism finds its source in animism, it is Vedic or Brahmanic India, where all the cosmic aspects are divinized, the man projecting his image on the world and explaining its functioning.

Purely theological discussions are rare in the ancient period of Hindu philosophical schools. The notion of god is absent or secondary before the end of the third century. In the 6th century we accept the notion of a creator god. The progression of Hinduism from the 5th century stimulated this rise of the imagination. Hindu art illustrates the great myths set towards the beginning of our era. It owes them its unity, beyond the regional divisions and the multiplicity of schools, as evidenced by the spread of forms of divinity throughout the subcontinent.

The Islamic civilization, generally aniconist, seems to have been imperceptibly impregnated by the Indian perspective: the Mughal painting (between the 16th century and the 19th century) gives a large place to the human figure, it addresses in some works with a subtlety and a psychological truth that renew the art of miniature[7] · [8].

At the end of the 19th century the Christian world emerged from the iconoclastic crisis that saw the return of icon worship in Byzantine Christianity. Christianity is very present in South India from the 16th century with the arrival of the Portuguese. The facades of the buildings often display biblical proverbs, colorful representations of Jesus enthroned on the walls and churches are omnipresent in the urban landscape. Here one can discover a rich and colorful representation, amazing mix combining the exuberance of Indian culture and Christian iconography. The many representations of Mary, Jesus and other saints of the Bible then take on unexpected traits, far from the sobriety of the representations found in Europe[9].

Among the animist tribes, for example among the Gond, Bhil and Warli, one often finds images of their gods.

Mandala

Religious meaning: A mandala is a spiritual and/or ritual geometric configuration of symbols in the Indian religions of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism.

A yantra is similar to a mandala, usually smaller and using a more limited colour palette. It may be a two- or three-dimensional geometric composition used in sadhanas, puja or meditative rituals, and may incorporate a mantra into its design. It is considered to represent the abode of the deity. Each yantra is unique and calls the deity into the presence of the practitioner through the elaborate symbolic geometric designs. According to one scholar, "Yantras function as revelatory symbols of cosmic truths and as instructional charts of the spiritual aspect of human experience." Many situate yantras as central focus points for Hindu tantric practice. Yantras are not representations, but are lived, experiential, nondual realities.

Political meaning: The Rajamandala (or Raja-mandala; circle of states) was formulated by the Indian author Kautilya in his work on politics, the Arthashastra (written between 4th century BCE and 2nd century BCE). It describes circles of friendly and enemy states surrounding the king's state. In historical, social and political sense, the term "mandala" is also employed to denote traditional Southeast Asian political formations (such as federation of kingdoms or vassalized states).

Genres of Indian painting

Indian paintings can be broadly classified as murals, miniatures and scroll paintings.

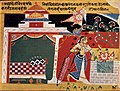

Murals are large works executed on the walls of solid structures, as in the Ajanta Caves and the Kailashnath temple.

Miniature paintings are executed on a very small scale for books or albums on perishable material such as paper and cloth. The Palas of Bengal were the pioneers of miniature painting in India. The art of miniature painting reached its glory during the Mughal period. The tradition of miniature paintings was carried forward by the painters of different Rajasthani schools of painting like the Bundi, Kishangarh, Jaipur, Marwar and Mewar. The Ragamala paintings also belong to this school, as does the Company painting produced for British clients under the British Raj.

Indian art has seen the rise of the Bengal School of art in 1930s followed by many forms of experimentations in European and Indian styles. In the aftermath of India's independence, many new genres of art developed by important artists like Jamini Roy, M. F. Husain, Francis Newton Souza, and Vasudeo S. Gaitonde.

With the progress of the economy the forms and styles of art also underwent many changes. In the 1990s, Indian economy was liberalised and integrated to the world economy leading to the free flow of cultural information within and without. Artists include Subodh Gupta, Atul Dodiya, Devajyoti Ray, Bose Krishnamachari and Jitish Kahllat whose works went for auction in international markets. Bharti Dayal has chosen to handle the traditional Mithila painting in most contemporary way and created her own style through the exercises of her own imagination, they appear fresh and unusual.

Murals

The earliest Indian paintings were the rock paintings of pre-historic times, the petroglyphs as found in places like Bhimbetka rock shelters. Some are approximately 30,000 years old.

The history of Indian murals in the Historical Era starts in ancient and early medieval times, from the 2nd century BCE to 8th – 10th century CE. There are known more than 20 locations around India containing murals from this period, mainly natural caves and rock-cut chambers. The highest achievements of this time are the caves of Ajanta, Bagh, Sittanavasal, Armamalai Cave (Tamil Nadu), Ravan Chhaya rock shelter, Kailasanatha temple in Ellora Caves.

Murals from this period depict mainly religious themes of Buddhist, Jain and Hindu religions. There are though also locations where paintings were made to adorn mundane premises, like the ancient theatre room in Jogimara Cave and possible royal hunting lodge circa 7th-century CE – Ravan Chhaya rock shelter.

Prehistoric painting, from 26,000 BCE

Since ancient times men have drawn in rock shelters, on walls and floors, to talk about their lives and leave their mark, but without religious significance. The Indian sub-continent has the third largest number of rock art after Australia and Africa, with more than 150 sites throughout India, but mostly located in the center (Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh)[10][11][12][13].

The age of this art and the phases of its evolution are not datable with precision. Indeed, it mainly includes red painted images with iron oxides (hematite), for which it is not possible to use the radiocarbon analysis, since it can only be applied to pigments of organic origin (coals for example). If some of these pigments were used, they were not preserved, because it is an outdoor art, exposed to light and elements, unlike the art of European caves.

The earliest Indian paintings are petroglyphs between 10 000 and 28 000 years old, according to sources, such as those found in Bhimbetka in the Vindhya Mountains north of the Narmada River in Madhya Pradesh and Jogimara (Sarguja) near the Narmada river in Chhattisgarh. Rock painting lasted until the third millennium BCE (Pachmarhi in Vindhya Mountains, Madhya Pradesh).

The first world discoveries of this art were in India in 1867, by archaeologist A.C.L. Carlleyle.

Rock art in India includes a majority of human figures, a great diversity of animals and some geometric signs, multiple symbols that cannot be interpreted when millennial traditions are extinct.

Two activities are represented during all periods: hunting and dancing. Men chased with the bow or the sword, for example to face a tiger. Their preys are mostly deer, but also bison, tigers, monkeys or birds. Dance plays an important figurative role in rock art and this activity remains present in the tribes today. Sometimes an isolated dancer waves his arms and body. Elsewhere, it will be a couple. Most often, the dancers are in groups, up to fifteen people, in a long line or a circle, the next body, the rhythm, the arms joined or lifted, without the identifier, their sex. Musical instruments include drums, flutes, harps and cymbals.

Animal drawings show a surprising variety. To make a single comparison: on about a thousand animal representations in Pachmarhi, we identify 26 different species, while in Lascaux in France, on an equivalent number, we only recognize 9[14]. Enigmatic are some 10,000-year-old cave paintings in Chhattisgarh. In Singhanpur near Raigarh there are drawings of giraffes[15]!

Most of the rock paintings have been executed using red and white pigments, rarely green and yellow, but in Bhimbetka there are 20 different colors. The rock paintings in the Bhimbetka shelters were probably the source of works by the Warli and Saura tribes[16].

Buddhist painting, from 3rd century BCE to 12th century

Buddhist art is the artistic practices that are influenced by Buddhism. It includes art media which depict Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other entities; notable Buddhist figures, both historical and mythical; narrative scenes from the lives of all of these; mandalas and other graphic aids to practice; as well as physical objects associated with Buddhist practice, such as vajras, bells, stupas and Buddhist temple architecture.

Buddhist art originated on the Indian subcontinent following the historical life of Siddhartha Gautama, 6th to 5th century BCE, and thereafter evolved by contact with other cultures as it spread throughout Asia and the world.

Buddhist art flourished and co-developed with Hindu and Jain art, with cave temple complexes built together, each likely influencing the other.

During the 2nd to 1st century BCE, sculptures became more explicit, representing episodes of the Buddha’s life and teachings. These took the form of votive tablets or friezes, usually in relation to the decoration of stupas. Although India had a long sculptural tradition and a mastery of rich iconography, the Buddha was never represented in human form, but only through Buddhist symbolism. This period may have been aniconic. Artists were reluctant to depict the Buddha anthropomorphically, and developed sophisticated aniconic symbols to avoid doing so (even in narrative scenes where other human figures would appear). This tendency remained as late as the 2nd century CE in the southern parts of India, in the art of the Amaravati School. It has been argued that earlier anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha may have been made of wood and may have perished since then. However, no related archaeological evidence has been found.

The earliest works of Buddhist art in India date back to the 1st century BCE. The Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya became a model for similar structures in Burma and Indonesia. There are examples of Buddhist frescoes in the 30 Buddhist artificial Ajanta caves, painted from the 2nd century BCE until the 8th century[17], but the frescoes at Sigiriya are said to be even older than the Ajanta Caves paintings.

In India, Buddhist art knows a great development and leaves its mark on all Hindu art until the virtual disappearance of Buddhism in the 10th century before the expansion of Hinduism and Islam, but we find the Buddhist illuminations on palm leaves made in the 11th century and 12th century in Bihar and Bengal.

The Thangka paintings, found in Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, are generally symbolic mystical diagrams (Mandala), deities of Tibetan Buddhism or the Bon religion, or portraits of the Dalai Lama. They are most often intended to serve as a medium for meditation. The diagram is in any case filled with symbols; it can be associated with a deity. Some mandalas, very elaborate and codified, become semi-figurative, semi-abstract.

See more: Mandala

Jaïn painting, 8th to 13th century

The jains, as with architecture and sculpture, contributed to a large extent to the development of pictorial art in India. Their tradition in this field is as old as that of Buddhist painting. An innumerable quantity of their works, of extraordinary quality, can be found on walls, on palm leaves, on cloth, on wood, and so on.

The Jain caves (30–34) at Ellora have dimensions that reveal the conceptions of Jainism. These reflect the strong sense of asceticism. This is why their dimensions are more restricted. Nevertheless the caves are carved just as finely as their Hindu and Buddhist counterparts. These caves are also different from others since their ceilings were originally richly painted. Paint fragments are still visible today.

Kerala mural painting, 8th to 19th century

Kerala mural paintings are the frescos depicting Hindu mythology and legends, which are drawn on the walls of temples and churches in South India, principally in Kerala. Ancient temples and palaces in Kerala, South India, display an abounding tradition of mural paintings mostly dating back between the 9th to 12th centuries CE when this form of art enjoyed Royal patronage. These days even Churches in Kerala are commissioning mural paintings with Christian motifs.

The masterpieces of Kerala mural art include: the Shiva Temple in Ettumanoor, the Ramayana murals of Mattancherry Palace and Vadakkumnatha kshetram. The "Gajendra Moksham" mural painting in the Krishnapuram Palace near Kayamkulam, the Anantha Shayanam mural painting in the Pallikurup Mahavishnu Temple at Mannarkkad and the mural paintings in the sanctum of Padmanabhaswamy Temple at Thiruvananthapuram are very famous. Some of the murals in Kerala are found in the churches at Cheppad, Alappuzha, Paliekkara, Thiruvalla, Angamaly and Akapparambu.

The earliest murals of Kerala have been found in the Thirunandikkara Cave Temple now belonging to the neighboring Tamil Nadu state.

The Chola frescoes of Tamil Nadu, 9th to 13th century

The Chola Dynasty of South India is very old. Mentioned in the Mahābhārata, it gave its name to the coast of Coromandel (after Chola Mandalam, "the land of Chola") in Tamil Nadu.

Cholas frescoes from the second period of their diet (850–1250) have been discovered under more recent paintings. During the reign of the Nayak (1529–1736), Chola frescoes were daubed with Tanjore-style paintings. The first of the Chola frescoes to be discovered, was in 1931 in the Brihadisvara temple[18] · [19].

Mysore painting, 14th to 16th century

Mysore painting is an important form of classical South Indian painting that originated in the town of Mysore in Karnataka. These paintings are known for their elegance, muted colours and attention to detail. The themes for most of these paintings are Hindu Gods and Goddesses and scenes from Hindu mythology. In modern times, these paintings have become a much sought-after souvenir during festive occasions in South India.

The process of making a Mysore painting involves many stages. The first stage involves the making of the preliminary sketch of the image on the base. The base consists of cartridge paper pasted on a wooden base. A paste made of zinc oxide and arabic gum is made called "gesso paste". With the help of a thin brush all the jewellery and parts of throne or the arch which have some relief are painted over to give a slightly raised effect of carving. This is allowed to dry. On this thin gold foil is pasted. The rest of the drawing is then painted using watercolours. Only muted colours are used.

Mysore's paintings are known for their elegance, soft colors and attention to detail. The themes of most of these paintings are Hindu gods and goddesses and scenes from Hindu mythology[20].

Contemporary schools that teach in the style of the Mysore School exist in Mysore, Bangalore, Narasipura, Tumkur, Sravanabelagola and Nanjangud[21].

Tanjore painting, 16th to 17th century

Tanjore painting is an important form of classical South Indian painting native to the town of Tanjore in Tamil Nadu. The art form dates back to the early 9th century, a period dominated by the Chola rulers, who encouraged art and literature. These paintings are known for their elegance, rich colours, and attention to detail. The themes for most of these paintings are Hindu Gods and Goddesses and scenes from Hindu mythology. In modern times, these paintings have become a much sought-after souvenir during festive occasions in South India.

The process of making a Tanjore painting involves many stages. The first stage involves the making of the preliminary sketch of the image on the base. The base consists of a cloth pasted over a wooden base. Then chalk powder or zinc oxide is mixed with water-soluble adhesive and apply it on the base. To make the base smoother, a mild abrasive is sometimes used. After the drawing is made, decoration of the jewelry and the apparels in the image is done with semi-precious stones. Laces or threads are also used to decorate the jewelry. On top of this, the gold foils are pasted. Finally, dyes are used to add colours to the figures in the paintings.

Rajput mural painting, 16th to 19th century

Rajput painting refers to various schools of Indian painting that appeared in the 16th century or early 17th century and developed during the 18th century to the royal court of Rajasthan in India.

Many murals have been made in palaces, inside fortresses and havelis, especially those in the Shekhawati region.

The miniature

The pattern of large scale wall painting which had dominated the scene since 2nd century BCE, witnessed the advent of miniature paintings during the 11th and 12th centuries. This new style figured first in the form of illustrations etched on palm-leaf manuscripts. The contents of these manuscripts included literature on Buddhism and Jainism. In eastern India, the principal centres of artistic and intellectual activities of the Buddhist religion were Nalanda, Odantapuri, Vikramshila and Somarpura situated in the Pala kingdom (Bengal and Bihar).

In eastern India miniature painting are developed in the 10th century. These miniatures, depicting Buddhist divinities and scenes from the life of Buddha were painted on the leaves (about 2.25 by 3 inches) of the palm-leaf manuscripts as well as their wooden covers. Most common Buddhist illustrated manuscripts include the texts Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita,[22] Pancharaksa, Karandavyuha and Kalachakra Tantra.

The earliest extant miniatures are found in a manuscript of the Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita dated in the sixth regnal year of Mahipala (c. 993), presently the possession of The Asiatic Society, Kolkata. This style disappeared from India in the late 12th century.

The influence of eastern Indian paintings can be seen in various Buddhist temples in Bagan, Myanmar particularly Abeyadana temple which was named after Queen consort of Myanmar, Abeyadana who herself had Indian roots and Gubyaukgyi Temple.[23] The influences of eastern Indian paintings can also be clearly observed in Tibetan Thangka paintings.[24]

In western India the miniature paintings are beautiful handmade paintings, which are quite colorful but small in size. The highlight of these paintings is the intricate and delicate brushwork, which lends them a unique identity. The colors are handmade, from minerals, vegetables, precious stones, indigo, conch shells, pure gold and silver. The evolution of Indian Miniatures paintings started in the Western Himalayas, around the 17th century.

The subjects of these miniature paintings are in relation to the subjects of the manuscripts mostly religious and literary. Many paintings are from Sanskrit and folk literature. It is on the subject of love stories. Some paintings from Vaishnav sect of Hindu religion and some are from Jain sect. The Paintings of Vaishnav sect are regarding various occasions of the life of Lord Krishna and Gopies. Vaishnav paintings of "Gita Govinda" is about Lord Krishna. The paintings of Jain sect is concerning to Jain Lords and religious subjects.

These paintings were created on "Taadpatra" that means the leaf of the palm tree, and Paper. During that period earlier manuscripts were created from the leaf of the palm tree and later on from the paper.

In these paintings there are very few human characters seen from the front. Most of the human characters are seen from side profile. Big eyes, pointed nose and slim waist are the features of these paintings. The skin colours of human being are Brown and fair. The skin colour of the Lord Krishna is Blue. The colour of the hair and eyes is black. Women characters have long hair. Human characters have worn jewellery on the hand, nose, neck, hair, waist and ankles. Men and women wear the traditional Indian dress, slippers and shoes. Men wear turbans on their head. In these paintings trees, rivers, flowers, birds, the land, the sky, houses, traditional chairs, cushions, curtains, lamps, and human characters have been painted.

Mostly Natural colours have been used in these paintings. Black, red, white, brown, blue, and yellow colours are used to decorate the paintings.

The Kings, Courtiers of the kings, wealthy businessmen, and religious leaders of the time were the promoters of these miniature paintings.

Painters of these pictures were from the local society." Vaachhak " was the famous painter of the time.Painters tried to make the subject of the manuscript live by these pictures so that the readers of the manuscript can enjoy reading.

Lighting on the techniques of the Indian miniature

In a painter's studio, several functions can coexist: calligrapher, draftsman, colorist or bookbinder. Before being a painter, the apprentice must first copy the classic models using layers (executed on thin skins goat or gazelle) or cliches. Models are used until they can be reproduced from memory. On the plain white background, a first sketch in red sets up the main elements, then the colored masses are applied and a darker final outline completes the work. The fine details (features of the faces, jewels) are painted last.

The Indian painter works sitting on the ground, the sheet fixed on a small board; his material consists of an assortment of goat hair or squirrel brushes and seashell valves to hold the colors. A brush with a single hair can be used to trace the imperceptible lines of hair and eyes. The paper, made of vegetable fibers (bamboo, jute, hemp) or cotton rags, linen, sometimes silk (Deccan), can be tinted with decoctions of saffron, henna or indigo leaves. To make them resistant, the leaves are glued with starch, gum or glucose and, after drying, lustered with a hard stone so that the brush slides easily.

The infinite variety of pigments is of natural origin. Black, for example, is made with carbon (carbon black) or is of metallo-gallic origin (metal salt and tannin). Yellow and orange are obtained from saffron, minium, sulfur or henna bark, but the yellow orpiment, typically Indian, comes from concretion of cow urine fed with mango leaves and is found pure in the soil. Pigments of mineral origin are malachite green, rare lapis lazuli blue, or azurite, which is a copper carbonate. The whole range of ochres and browns, from red to brown, comes from the land, while red lacquer is extracted from cochineal.

The completed miniature, placed on a marble plate, undergoes a final polishing on the back, which gives its colors this almost enameled glare. The margins (hashiya), constitute a significant element of the Mughal miniatures: nets of color, wash or golden garland border the miniature, then a margin, sandblasted of gold or silver or marbled paper or still decorated with the stencil, frames the painted page[25].

Buddhist miniatures in the Pala and Sena dynasties, from the 8th to the 13th century

The story of the miniature begins in East India (Bengal and Nepal) in Buddhist monasteries around the 8th century. The iconographic rules were strict and generally illustrated the life of Buddha. Unfortunately, many bookshops in these monasteries were destroyed during the Turkish invasions in 1192 and Buddhist monks and painters were forced to flee to the Himalayan regions and Nepal. Anyway, miniatures on palm leaves made in the 11th and 12th centuries were found in Bihar and Bengal[26].

The Pala and Sena dynasties ruled Bengal-Bengal from the 8th century to the 13th century.

The Pala was an Indian Buddhist dynasty that ruled from the 8th century to the 11th century. The dynasty was founded around 750 by Go Pala, elected king to put an end to half a century of disorder. After the Muslim invasions led by Muhammad Khilji towards the end of the 11th century, the Pala disappear and are replaced in the region by their former allies, the Sena. With the arrival of the Sena, Hinduism patronized by the kings rubs Buddhism to merge: Buddha becomes an avatar of Vishnu. The Sena then reigns from the 12th century to the 13th century.

Originally from the south of the region, the Sena dynasty was founded in 1070 by Hemanta Sena, originally vassal of the Pala dynasty, who took power and declared himself independent in 1095. In 1202, the capital Nadiya was evacuated before the arrival of General Bakhtiyar Khalji of the tribe (Persian) Ghuride. The Ghurids seize West Bengal in 1204. Lakshman Sena dies soon after, and his successors reign for some time on the east side of Bengal, but political power passes into the hands of the Delhi Sultanate with the death of Keshab Sena in 1230.

Tala Patta Chitra from Orissa, from the 8th century

The Tala Patta Chitra is a miniature style of Orissa, whose earliest representations date back to the 8th century.

The paintings were originally made on dried palm leaves, cut into equally sized rectangles sewn together with black or white thread. The drawings were engraved with a kind of stylet and the engravings obtained filled with ink. Once the lines were defined, vegetable dyes were used to color the drawings. However, most of the time these paintings were dichromatic (black and white).

The painting is intimately linked to the cult of Jagannatha, ninth avatar of Krishna especially revered in Puri. The works are essentially scenes from Indian mythology and the two great epics of Rāmāyana and Mahābhārata, as well as legends of local folklore.

Jain miniatures, 11th to 16th century

The Jains, as with architecture and sculpture, contributed to a large extent to the development of pictorial art in India. A myriad of works of extraordinary quality can be found on walls, palm leaves, cloth, wood and manuscripts. Ellora has very rich ceiling paintings in Jain caves.

The Jain miniature is called "Gujarat style" or more specifically "Jain style".

In western India, in Gujarat and Rajasthan, the Jaïn miniature appeared around the 11th century and was extinguished with the iconoclasm of Muslims. The scribes copied psalms, legends, fables and biographies in golden ink. The most illustrated text was Kalpasûtra. Thumbnails were only present at the introduction and conclusion to preserve the esoteric character of the text. The calligraphy was made in gold or silver ink on vermilion, purple or blue backgrounds[27].

The scribe was the one who visualized the whole and defined the space reserved for the painter. The formats were not very large (due to the shape of the palm leaf) which forced the artist to paint in a narrative way. The characters are very stylized, on a blue or red monochrome background with eyes painted on the outside of a rather austere face. Small in stature, they have very richly decorated costumes with bright colors and lots of gold[28].

Nirmal miniatures from Telangana, from the 14th century

The Nirmal miniatures are made of soft white wood called Ponniki, which is hardened by basting it with tamarind seed paste and covering it with fine muslin and pipe clay. The colors used are extracts of plants and minerals. On a dark background, the paintings are highlighted in a golden color derived from the herbal juice.

Deccan miniatures, 16th to 17th century

While Mughal painting was developing under Akbar, in the second half of the 16th century, the art form was evolving independently in the Deccan sultanates. The miniature painting style, which flourished initially in the Bahmani court of Bahmani Sultanate and later in the courts of Ahmadnagar, Bijapur, Bidar, Berar and Golkonda is popularly known as the Deccan school of Painting[29]..

The style of Deccani painting flourished in the 16th and 17th centuries, Passing through multiple phases of sudden maturation and prolonged stagnation, later in the 18th and 19th centuries after the Mughal conquest of Deccan the style gradually withered away and new form of Hyderabad style painting evolved in the Deccan region particularly in the Nizam territory. Most of the colouring of Deccani paintings are Islamic Turkish and Persian tradition specially the arabesques, but those are surmounted by a pure Deccani piece of foliage.

The Deccan Plateau covers parts of several states in central India, Maharashtra in the north, Chhattisgarh in the northeast, Andhra Pradesh in the east, Karnataka in the west, the most south extending into Tamil Nadu. The most important city of the Deccan is Hyderabad, the capital of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Other important cities include Bangalore, the capital of Karnataka, as well as Nagpur, Pune and Sholapur in Maharashtra. Three large rivers drain with their tributaries the waters of the plateau, Godavari to the north, Krishna to the center and Cauvery to the south.

Malwa, Deccan and Jaunpur schools of painting

A new trend in manuscript illustration was set by a manuscript of the Nimatnama painted at Mandu, during the reign of Nasir Shah (1500–1510). This represent a synthesis of the indigenous and the patronized Persian style, though it was the latter which dominated the Mandu manuscripts. There was another style of painting known as Lodi Khuladar that flourished in the Sultanate's dominion of North India extending from Delhi to Jaunpur[31].

The miniature painting style, which flourished initially in the Bahmani court and later in the courts of Ahmadnagar, Bijapur and Golkonda is popularly known as the Deccan school of Painting.[32][33][34] One of the earliest surviving paintings are found as the illustrations of a manuscript Tarif-i-Hussain Shahi (c.1565), which is now in Bharata Itihasa Samshodhaka Mandala, Pune. About 400 miniature paintings are found in the manuscript of Nujum-ul-Ulum (Stars of Science) (1570), kept in Chester Beatty Library, Dublin.[35]

Hindu miniatures from South India, 16th to the 18th century

The southern tip of the Indian peninsula is today made up of four Dravidian language states (Tamul, Malayalam, Kannada and Telugu). Tamul, a living language widely spoken in Tamil Nadu and south of Andhra Pradesh, spawned a very rich classical literature from the beginning of our era. The main historical texts, poetic and mystical of Sanskrit origin, have been rewritten in Tamil with many variations and denote a strongly Brahmanic country. Religion and mythology permeate everyday life; the numerous temples give rise to pilgrimages, to feasts dedicated to multiple deities and their innumerable legends. The syncretism inherent in the Hindu religion multiplies to infinity the sectarian, regional, even local variants.

In 1565, after the defeat of Talikota, Vijayanagara, the last and vast Hindu kingdom of southern India, was dismembered by the Muslim coalition forces. Some families of artists exiled themselves further east to Andhra Pradesh, where their tradition has been maintained with kalamkari, fabrics painted with mythological tales that narrators make explicit around the temples. In the south, towards the Nayakas provinces, the painters on paper remained as faithful to these conventional prototypes.

In the 18th century, many painters settled in the former "Presidency of Madras (Chennai)". They spoke the Telugu language. They produced a popular imagery, very synthetic and bright colors, for pilgrims who went in large numbers in the holy cities. These extraordinarily fresh paintings are an exceptional documentary mine on Indian mythology and ethnography. They compose an incomparable repertoire of forms. It contains the epic story or the great myths, and the many Hindu deities with symbolic attributes and figured in precise postures according to a rigorous iconographic codification. The gods recognize their gestures, attributes and weapons that recall their exploits and that they hold with their pairs of arms. They may have more when they want to show their power or anger[36].

Rajput painting, 16th to 19th century

Rajput painting, a style of Indian painting, evolved and flourished, during the 18th century, in the royal courts of Rajputana.[37][38] Each Rajput kingdom evolved a distinct style, but with certain common features. Rajput paintings depict a number of themes, events of epics like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, Krishna's life, beautiful landscapes, and humans. Miniatures were the preferred medium of Rajput painting, but several manuscripts also contain Rajput paintings, and paintings were even done on the walls of palaces, inner chambers of the forts, havelies, particularly, the havelis of Shekhawati.

The colours extracted from certain minerals, plant sources, conch shells, and were even derived by processing precious stones, gold and silver were used. The preparation of desired colours was a lengthy process, sometimes taking weeks. Brushes used were very fine.[35]

In the late 16th Century, Rajput art schools began to develop distinctive styles, combining indigenous as well as foreign influences such as Persian, Mughal, Chinese and European.[39] Rajasthani painting consists of four principal schools that have within them several artistic styles and substyles that can be traced to the various princely states that patronised these artists. The four principal schools are:

- The Mewar school that contains the Chavand, Nathdwara, Devgarh, Udaipur and Sawar styles of painting

- The Marwar school comprising the Kishangarh, Bikaner, Jodhpur, Nagaur, Pali and Ghanerao styles

- The Hadoti school with the Kota, Bundi and Jhalawar styles and

- The Dhundar school of Amber, Jaipur, Shekhawati and Uniara styles of painting.

The Kangra and Kullu schools of art are also part of Rajput painting. Nainsukh is a famous artist of Pahari painting, working for Rajput princes who then ruled that far north.

Assam miniatures, 16th to 19th century

Most of the Assamese are Hindu (65%) and Muslim (31%). The different communities speak 44 languages but mainly Assamese (49%) and Bengali (28%).

Assam is known for miniature paintings in manuscripts from the 16th century to the 19th century, funded by monasteries (Sattras) or the kings of the Ahom people. The religious manuscripts on the tales of Bhagavata, Puranas, Ramayana, Mahabharata and the epics were thus illustrated with miniatures (illuminations). Since the 1930s contemporary artists have taken over the miniature style on their canvases[40].

Mughal painting, 16th to 19th century

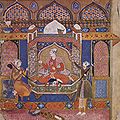

Mughal painting is a style of Indian painting, generally confined to illustrations on the book and done in miniatures, and which emerged, developed and took shape during the period of the Mughal Empire between the 16th and 19th centuries.[41] The Mughal style was heavily influenced by Persian miniatures, and in turn influenced several Indian styles, including the Rajput, Pahari and Deccan styles of painting.

Mughal paintings were a unique blend of Indian, Persian and Islamic styles. Because the Mughal kings wanted visual records of their deeds as hunters and conquerors, their artists accompanied them on military expeditions or missions of state, or recorded their prowess as animal slayers, or depicted them in the great dynastic ceremonies of marriages.[42]

Akbar's reign (1556–1605) ushered a new era in Indian miniature painting.[35] After he had consolidated his political power, he built a new capital at Fatehpur Sikri where he collected artists from India and Persia. He was the first monarch who established in India an atelier under the supervision of two Persian master artists, Mir Sayyed Ali and Abdus Samad. Earlier, both of them had served under the patronage of Humayun in Kabul and accompanied him to India when he regained his throne in 1555. More than a hundred painters were employed, most of whom were from Gujarat, Gwalior and Kashmir, who gave a birth to a new school of painting, popularly known as the Mughal School of miniature Paintings.

One of the first productions of that school of miniature painting was the Hamzanama series, which according to the court historian, Badayuni, was started in 1567 and completed in 1582. The Hamzanama, stories of Amir Hamza, an uncle of the Prophet, were illustrated by Mir Sayyid Ali. The paintings of the Hamzanama are of large size, 20 x 27" and were painted on cloth. They are in the Persian safavi style. Brilliant red, blue and green colours predominate; the pink, eroded rocks and the vegetation, planes and blossoming plum and peach trees are reminiscent of Persia. However, Indian tones appear in later work, when Indian artists were employed.

After him, Jahangir encouraged artists to paint portraits and durbar scenes.[43][35] His most talented portrait painters were Ustad Mansur, Abul Hasan and Bishandas.

Shah Jahan (1627–1658) continued the patronage of painting.[43] Some of the famous artists of the period were Mohammad Faqirullah Khan, Mir Hashim, Muhammad Nadir, Bichitr, Chitarman, Anupchhatar, Manohar and Honhar.[44][35]

Aurangzeb had no taste for fine arts, probably due to his Islamic conservatism.[43] Due to lack of patronage artists migrated to Hyderabad in the Deccan and to the Hindu states of Rajputana in search of new patrons.

Mughal provincial miniatures, 18th century

As a result of the collapse of imperial power, many families of artists took refuge with other patrons, Rajput rulers or nabab (nawab) who ruled the provinces of the empire. Among the latter, schools - the so-called provincial moguls (in Faizabad, Murshidabad, and Farrukhabad) - of a new style, flourished. A bit like troubadour painting, the late Mughal miniature favored representations of zenana (ladies' apartment), romantic or poetic subjects from literature. The bravery of the warlord was followed by the unhappy and romantic hero and the recurring romantic themes (such as the meeting of Shirin and Khosrow, or of Sahib and Wafa at the well, for example). The almost magical religious subject of Ibrahim Sultan of Balkh served by the angels was also common, as was the picturesque hunting of the Bhils (aborigines of northern Deccan) or women visiting a sadhu (Hindu ascetic). Finally, ragamala ("garland of raga"), suites illustrating musical themes of Indian origin, were also fashionable[45].

Pahari Painting, 17th to 19th century

Pahari painting (literally meaning a painting from the mountainous regions: pahar means a mountain in Hindi) is an umbrella term used for a form of Indian painting, done mostly in miniature forms, originating from Himalayan hill kingdoms of North India, during 17th to 19th centuries stretching from Jammu to Almora and Garhwal, in the sub-Himalayan India, through Himachal Pradesh.[46] Each created stark variations within the genre, ranging from bold intense Basohli Painting, originating from Basohli in Jammu and Kashmir, to the delicate and lyrical Kangra paintings, which became synonymous to the style before other schools of paintings developed.[46][38]

Pahari painting grew out of the Mughal painting, though this was patronized mostly by the Rajput kings who ruled many parts of the region, and gave birth to a new idiom in Indian painting.[47]

Company style, 18th century

As Company rule in India began in the 18th century, a great number of Europeans migrated to India. The Company style is a term for a hybrid Indo-European style of paintings made in India by Indian and European artists, many of whom worked for European patrons in the British East India Company or other foreign Companies in the 18th and 19th centuries.[48][35]

The style blended traditional elements from Rajput and Mughal painting with a more Western treatment of perspective, volume and recession. Most paintings were small, reflecting the Indian miniature tradition, but the natural history paintings of plants and birds were usually life size.

Leading centres were the main British settlements of Calcutta, Madras (Chennai), Delhi, Lucknow, Patna,the Maratha court of Thanjavur and Bangalore. Subjects included portraits, landscapes and views, and scenes of Indian people, dancers and festivals.

The scroll painting

The scroll paintings are in the form of sheets of paper sewn together and sometimes stuck on canvas. Their width ranges from 10 to 35 cm and their length, rarely below 1 m, can exceed 5 m (Thangas can reach several tens of meters). At each end of these rolls, a bamboo (sometimes decorated with engraved patterns) is used to wind and unroll the paint. This one is realized, by one or more painters, using vegetable colors. Black is thus obtained with charcoal or burnt rice, red with betel, blue with the fruit of a tree called nilmoni, etc. In order to fix these colors, a tree resin which has been previously melted is added.

The school of Patta Chitra is the school known for its scroll paintings. But several other schools followed, even a school like "Company Paintings", which is rather known for its miniatures.

Pattachitra, from 5th century BCE

Pattachitra refers to the Classical painting of Odisha and West Bengal, in the eastern region of India.'Patta' in Sanskrit means 'Vastra' or 'clothings' and 'chitra' means paintings.

The Bengal Patachitra refers to the painting of West Bengal. It is a traditional and mythological heritage of West Bengal. The Bengal Patachitra is divided into some different aspects like Durga Pat, Chalchitra, Tribal Patachitra, Medinipur Patachitra, Kalighat Patachitra etc.[49] The subject matter of Bengal Patachitra is mostly mythological, religious stories, folk lore and social. The Kalighat Patachitra, the last tradition of Bengal Patachitra is developed by Jamini Roy. The artist of the Bengal Patachitra is called Patua.[50]

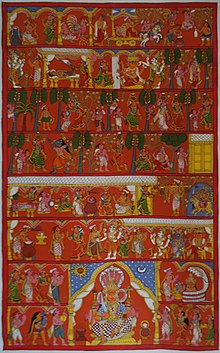

The tradition of Orisha Pattachitra is closely linked with the worship of Lord Jagannath. Apart from the fragmentary evidence of paintings on the caves of Khandagiri and Udayagiri and Sitabhinji murals of the 6th century CE, the earliest indigenous paintings from Odisha are the Pattachitra done by the Chitrakars (the painters are called Chitrakars).[51] The theme of Oriya painting centres round the Vaishnava sect. Since beginning of Pattachitra culture Lord Jagannath who was an incarnation of Lord Krishna was the major source of inspiration. The subject matter of Patta Chitra is mostly mythological, religious stories and folk lore. Themes are chiefly on Lord Jagannath and Radha-Krishna, different "Vesas" of Jagannath, Balabhadra and Subhadra, temple activities, the ten incarnations of Vishnu basing on the 'Gita Govinda' of Jayadev, Kama Kujara Naba Gunjara, Ramayana, Mahabharata. The individual paintings of gods and goddesses are also being painted.

The painters use vegetable and mineral colours without going for factory made poster colours. They prepare their own colours. White colour is made from the conch-shells by powdering, boiling and filtering in a very hazardous process. It requires a lot of patience. But this process gives brilliance and premanence to the hue. 'Hingula', a mineral colour, is used for red. 'Haritala', king of stone ingredients for yellow, 'Ramaraja' a sort of indigo for blue are being used. Pure lamp-black or black prepared from the burning of cocoanut shells are used.The brushes that are used by these 'Chitrakaras' are also indigenous and are made of hair of domestic animals. A bunch of hair tied to the end of a bamboo stick make the brush. It is really a matter of wonder as to how these painters bring out lines of such precision and finish with the help of these crude brushes.

That old tradition of Oriya painting still survives to-day in the skilled hands of Chitrakaras (traditional painters) in Puri, Raghurajpur, Paralakhemundi, Chikiti and Sonepur.

Nakashi (Cheriyal) Patta Chitra from Telangana, from 2nd century BCE

Cheriyal Scroll Painting is a stylized version of Nakashi art, rich in the local motifs peculiar to the Telangana. They are at present made only in Hyderabad, Telangana, India.[52] The scrolls are painted in a narrative format, much like a film roll or a comic strip, depicting stories from Indian mythology,[53] and intimately tied to the shorter stories from the Puranas and Epics. Earlier, these paintings were prevalent across Andhra, as also various other parts of the country, albeit flavoured with their distinct styles and other local peculiarities dictated by the local customs and traditions. In the same way, Cheriyal scrolls must have been popular across Telangana in earlier times, though with the advent of television, cinemas and computers it has been fenced into its last outpost, the Cheriyal town.

Thangka bouddhiste Painting, from 8th century

A thangka is a Tibetan Buddhist painting on cotton, silk appliqué, usually depicting a Buddhist deity, scene, or mandala. Thangkas are traditionally kept unframed and rolled up when not on display, mounted on a textile backing somewhat in the style of Chinese scroll paintings, with a further silk cover on the front. So treated, thangkas can last a long time, but because of their delicate nature, they have to be kept in dry places where moisture will not affect the quality of the silk. Most thangkas are relatively small, comparable in size to a Western half-length portrait, but some are extremely large, several metres in each dimension; these were designed to be displayed, typically for very brief periods on a monastery wall, as part of religious festivals. Most thangkas were intended for personal meditation or instruction of monastic students. They often have elaborate compositions including many very small figures. A central deity is often surrounded by other identified figures in a symmetrical composition. Narrative scenes are less common, but do appear.

Thangka serve as important teaching tools depicting the life of the Buddha, various influential lamas and other deities and bodhisattvas. One subject is The Wheel of Life (Bhavachakra), which is a visual representation of the Abhidharma teachings (Art of Enlightenment). The term may sometimes be used of works in other media than painting, including reliefs in metal and woodblock prints. Today printed reproductions at poster size of painted thangka are commonly used for devotional as well as decorative purposes. Many tangkas were produced in sets, though they have often subsequently become separated.

Thangka perform several different functions. Images of deities can be used as teaching tools when depicting the life (or lives) of the Buddha, describing historical events concerning important Lamas, or retelling myths associated with other deities. Devotional images act as the centerpiece during a ritual or ceremony and are often used as mediums through which one can offer prayers or make requests. Overall, and perhaps most importantly, religious art is used as a meditation tool to help bring one further down the path to enlightenment. The Buddhist Vajrayana practitioner uses a thanka image of their yidam, or meditation deity, as a guide, by visualizing "themselves as being that deity, thereby internalizing the Buddha qualities"[54] tangkas hang on or beside altars, and may be hung in the bedrooms or offices of monks and other devotees.

Phad from Rajasthan, from 14th century

Phad painting is a style religious scroll painting and folk painting, practiced in Rajasthan state of India.[55][56] This style of painting is traditionally done on a long piece of cloth or canvas, known as phad. The narratives of the folk deities of Rajasthan, mostly of Pabuji and Devnarayan are depicted on the phads. The Bhopas, the priest-singers traditionally carry the painted phads along with them and use these as the mobile temples of the folk deities, who are worshipped by the Rebari community of the region. The phads of Pabuji are normally about 15 feet in length, while the phads of Devnarayan are normally about 30 feet long. Traditionally the phads are painted with vegetable colors.

The Joshi families of Bhilwara, Shahpura in Bhilwara district of Rajasthan are widely known as the traditional artists of this folk art-form for the last two centuries.

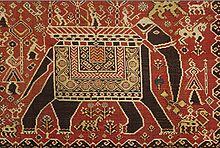

Jain Vastrapatas, from 15th century

Jain paintings on paper and fabrics (vastrapatas), tells the traditions of the Jains. The best known work is a scroll painting (length 210 cm) from 1610 (see photo) or Emperor Jehangir prohibit meat consumption during the Jain Paryushan festival. The scroll is preserved in the Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum in Ahmedabad[57] · [58].

Jadupatua from West-Bengal and Orissa, from 19th century

The Santhals are known for their scroll paintings, which has the same expression as in the art of Patta Chitra.

Body painting

At the dawn of humanity, humans discover colorful earth, charcoal, chalk, juice of colorful berries, animal blood and many other colors that may serve to impress the enemy in the form of war painting, or recognition sign within a tribe. This primitive makeup technique was also used as a camouflage for hunting.

Probably even before the first stone is engraved, the man applies pigments on his body to assert his identity, belonging to his group and be in relation to his entourage. Drawings and colors make it possible to change one's identity, to mark the entry into a new state or social group, to define a ritual position or to reaffirm the membership of a specific community, or to simply serve as adornment.

Permanent body painting: the tattoo

Tattoos have been used in India since ancient times, especially among tribal people. For hundreds of years, the tradition of tattooing has been venerated in the deep countryside. The ancient labyrinth-shaped sculptures on prehistoric rocks have been copied by tribal communities on their bodies. They call it the gudna process. These tattoos have a relationship with their religion, sex and neighborhood, but tattoos often replace jewelry, too expensive to acquire. For some populations tattooing is a necessity for their group, for others it is a way to dress the naked body. In recent years, tattoos have become fashionable among some young Indians living in the metropolis.

See more: fr:Tatouage en Inde

Temporary body painting

The colors used for the Holi have each a special meaning: green represents harmony, orange optimism, blue vitality and red joy and love. Holi, or the festival of colors, is a Hindu festival that celebrates both spring and fertility. Young people prepare their colors and their "weapons" several days in advance. Balloons filled with powder, liters of colored water, syringes, pistols and water rifles, for Holi, everything is good.

Women practice a more durable form of body painting (one to three weeks) using henna, often at religious festivals or weddings. Henna decorations produce shades of orange to black. It is used for both care and body adornment. The motifs represented all have a symbolism relating to popular beliefs.

Modern painting

At the start of the 18th century, oil and easel painting began in India, which saw many European artists, such as Zoffany, Kettle, Hodges, Thomas and William Daniell, Joshua Reynolds, Emily Eden and George Chinnery coming out to India in search of fame and fortune. The courts of the princely states of India were an important draw for European artists due to their patronage of the visual and performing arts.

The earliest formal art schools in India, namely the Government College of Fine Arts in Madras (1850), Government College of Art & Craft in Calcutta (1854) and Sir J. J. School of Art in Bombay (1857), were established.[59]

Raja Ravi Varma was a pioneer of modern Indian painting. He drew on Western traditions and techniques including oil paint and easel painting, with his subjects being purely Indian, such as Hindu deities and episodes from the epics and Puranas. Some other prominent Indian painters born in the 19th century are Mahadev Vishwanath Dhurandhar (1867–1944), A X Trindade (1870–1935),[60] M F Pithawalla (1872–1937),[61] Sawlaram Lakshman Haldankar (1882–1968) and Hemen Majumdar (1894–1948).

A reaction to the Western influence led to a revival in historic and more nationalistic Indian art, called as the Bengal school of art, which drew from the rich cultural heritage of India.

Influence of the Tagore family

Abanindranath Tagore was the first to claim a national art, in the name of "authenticity" Indian, drawing inspiration from the court painting of northern India. From then on was affirmed the willingness to break with Western academic illusionism, reconnecting with the rich heritage from the sub-continent.

Gaganendranath Tagore and Rabindranath Tagore chose other pathways to express this refusal. They opted for an opening of the Indian cultural sphere to other influences, including those of the European avant-gardes. So far from the precepts nationalists back to the "Golden Age of Vedic", Gaganendranath and Rabindranath Tagore asserted their artistic Indianity by taking inspiration from other artistic forms: Japanese art, Aztec art, forms cubists, expressionists or wild animals. The advent of independence allowed to relax the debate between art and national identity.

Subho Tagore, founder of the Calcutta Group, was among the first Indian artists to openly claim their belonging to international modernity.[62]

See more: Tagore family

Kalighat from Calcutta, 1850–1940

Kalighat painting, or pata (originally pronounced 'pot' in Bengali) is a style of Indian painting derives its name from the place. It is characterised by generously curving figures of both men and women and an earthy satirical style. It developed during the nineteenth century in response to the sudden prosperity brought to Calcutta by the East India Company trade, whereby many houses including that of 'Prince' Dwarkanath Tagore, grandfather of Rabindranath Tagore became incredibly wealthy. Many of these nouveau riche families came from not particular exalted caste backgrounds, so the orthodox tended to frown on them and their often very tasteless conspicuous consumption. To the common people the babus, as they were called, were equally objects of fun and sources of income. Thus the 'babu culture' portrayed in the Kalighat patas often shows inversions of the social order (wives beating husbands or leading them about in the guise of pet goats or dogs, maidservants wearing shoes, sahibs in undignified postures, domestic contretemps, and the like.) They also showed European innovations (babus wearing European clothes, smoking pipes, reading at desks, etc.). The object of this is only partly satirical; it also expresses the wonder that ordinary Bengalis felt on exposure to these new and curious ways and objects.

Kalighat pata pictures are highly stylised, do not use perspective, are usually pen and ink line drawings filled in with flat bright colours and normally use paper as a substrate, though some may be found with cloth backing or on cloth. The artists were rarely educated, and usually came from a lineage of artisans. Kalighat patas are still made today although genuine work is hard to come by. The art form is urban and largely secular: although gods and goddesses are often depicted, they appear in much the same de-romanticised way as the humans do. By contrast, the Orissa tradition of pata-painting, centering on Puri, is consciously devotional. Kalighat pata has been credited with influencing the Bengal School of art associated with Jamini Roy.

Bengal school, 1900

The Bengal School of Art was an influential style of art that flourished in India during the British Raj in the early 20th century. It was associated with Indian nationalism, but was also promoted and supported by many British arts administrators.

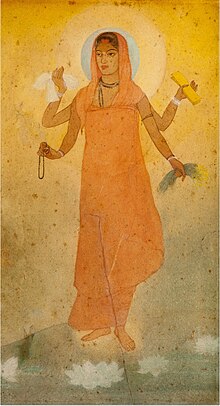

The Bengal school arose as an avant garde and nationalist movement reacting against the academic art styles previously promoted in India, both by Indian artists such as Ravi Varma and in British art schools. Following the widespread influence of Indian spiritual ideas in the West, the British art teacher Ernest Binfield Havel attempted to reform the teaching methods at the Calcutta School of Art by encouraging students to imitate Mughal miniatures. This caused immense controversy, leading to a strike by students and complaints from the local press, including from nationalists who considered it to be a retrogressive move. Havel was supported by the artist Abanindranath Tagore, a nephew of the poet and artist Rabindranath Tagore.[35][63] Abanindranath painted a number of works influenced by Mughal art, a style that he and Havel believed to be expressive of India's distinct spiritual qualities, as opposed to the "materialism" of the West. His best-known painting, Bharat Mata (Mother India), depicted a young woman, portrayed with four arms in the manner of Hindu deities, holding objects symbolic of India's national aspirations.

Tagore later attempted to develop links with Far-Eastern artists as part of an aspiration to construct a pan-Asianist model of art. Those associated with this Indo-Far Eastern model included Nandalal Bose, Mukul Dey, Kalipada Ghoshal, Benode Behari Mukherjee, Vinayak Shivaram Masoji, B.C. Sanyal, Beohar Rammanohar Sinha, and subsequently their students A. Ramachandran, Tan Yuan Chameli, Ramananda Bandopadhyay and a few others.

The Bengal school's influence on Indian art scene gradually started alleviating with the spread of modernist ideas post-independence.K. G. Subramanyan's role in this movement is significant.

Indian Society of Oriental Art : Abanindranath Tagore, 1907

In 1907 Abanindranath Tagore and his brother Gaganendranath Tagore open Indian Society of Oriental Art.

Abanindranath Tagore was the first to claim a national art, in the name of an Indian "authenticity", drawing inspiration from the court painting of northern India.

With Shadanga (the six principles of Indian painting from the first century BC), Abanindranath Tagore sets, referring in part to Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana, the six main canons of Indian classical painting:

1) Roopa-Bheda or the science of forms,

2) Pramanami or the meaning of relationships,

3) Bhava or the influence of feelings on the form,

4) Lavanya-Yojnam or the meaning of grace,

5) Sadradhyam or comparisons and

6) Varnika-Bhanga or knowledge and application of colors.

He adds to this list two more principles:

7) Rasa, the quintessence of taste, and

8) Chanda, the rhythm.

These rules and codes of representation will form the aesthetic and plastic foundations of the School of Bengal movement.

Gaganendranath et Rabindranath Tagore optèrent plutôt pour une ouverture de la sphère culturelle indienne à d'autres influences, parmi lesquelles celles des avant-gardes européennes.

Les artistes les plus connus sont Abanindranath Tagore, Surendranath Ganguly, Nandalal Bose, Asitkumar Haldar et Gaganendranath Tagore[62] · [64].

Santiniketan, 1924 - Rabindranath Tagore

The term Contextual Modernism that Siva Kumar used in the catalogue of the exhibition has emerged as a postcolonial critical tool in the understanding of the art the Santiniketan artists had practised.

Several terms including Paul Gilroy’s counter culture of modernity and Tani Barlow's Colonial modernity have been used to describe the kind of alternative modernity that emerged in non-European contexts. Professor Gall argues that ‘Contextual Modernism’ is a more suited term because “the colonial in colonial modernity does not accommodate the refusal of many in colonised situations to internalise inferiority. Santiniketan’s artist teachers’ refusal of subordination incorporated a counter vision of modernity, which sought to correct the racial and cultural essentialism that drove and characterised imperial Western modernity and modernism. Those European modernities, projected through a triumphant British colonial power, provoked nationalist responses, equally problematic when they incorporated similar essentialisms.”[65]

According to R. Siva Kumar "The Santiniketan artists were one of the first who consciously challenged this idea of modernism by opting out of both internationalist modernism and historicist indigenousness and tried to create a context sensitive modernism."[66] He had been studying the work of the Santiniketan masters and thinking about their approach to art since the early 80s. The practice of subsuming Nandalal Bose, Rabindranath Tagore, Ram Kinker Baij and Benode Behari Mukherjee under the Bengal School of Art was, according to Siva Kumar, misleading. This happened because early writers were guided by genealogies of apprenticeship rather than their styles, worldviews, and perspectives on art practice.[66]

The literary critic Ranjit Hoskote while reviewing the works of contemporary artist Atul Dodiya writes, "The exposure to Santinketan, through a literary detour, opened Dodiya’s eyes to the historical circumstances of what the art historian R Siva Kumar has called a “contextual modernism” developed in eastern India in the 1930s and ’40s during the turbulent decades of the global Depression, the Gandhian liberation struggle, the Tagorean cultural renaissance and World War II."[67]

Contextual Modernism in the recent past has found its usage in other related fields of studies, specially in Architecture.[68][62]

Contemporary metropolitan painting

During the colonial era, Western influences started to make an impact on Indian art. Some artists developed a style that used Western ideas of composition, perspective and realism to illustrate Indian themes. Others, like Jamini Roy, consciously drew inspiration from folk art.[69] Bharti Dayal has chosen to handle the traditional Mithila Painting in most contemporary way and uses both realism as well abstractionism in her work with a lot of fantasy mixed in to both .Her work has an impeccable sense of balance, harmony and grace.

By the time of Independence in 1947, several schools of art in India provided access to modern techniques and ideas. Galleries were established to showcase these artists. Modern Indian art typically shows the influence of Western styles, but is often inspired by Indian themes and images. Major artists are beginning to gain international recognition, initially among the Indian diaspora, but also among non-Indian audiences.

The Progressive Artists' Group, established shortly after India became independent in 1947, was intended to establish new ways of expressing India in the post-colonial era. The founders were six eminent artists – K. H. Ara, S. K. Bakre, H. A. Gade, M.F. Husain, S.H. Raza and F. N. Souza, though the group was dissolved in 1956, it was profoundly influential in changing the idiom of Indian art.[70] Almost all India's major artists in the 1950s were associated with the group. Some of those who are well-known today are Bal Chabda, Manishi Dey, V. S. Gaitonde, Krishen Khanna, Ram Kumar, Tyeb Mehta, Beohar Rammanohar Sinha and Akbar Padamsee. Other famous painters like Jahar Dasgupta, Prokash Karmakar, John Wilkins, and Bijon Choudhuri enriched the art culture of India. They have become the icon of modern Indian art. Art historians like Prof. Rai Anand Krishna have also referred to those works of modern artistes that reflect Indian ethos.

Also, the increase in the discourse about Indian art, in English as well as vernacular Indian languages, appropriated the way art was perceived in the art schools. Critical approach became rigorous, critics like Geeta Kapur,[71][72] R . Siva Kumar,[73][63][74][75] contributed to re-thinking contemporary art practice in India.Their voices represented Indian art not only in India but across the world. The critics also had an important role as curators of important exhibitions, re-defining modernism and Indian-art.

Indian Art got a boost with the economic liberalization of the country since the early 1990s. Artists from various fields now started bringing in varied styles of work. Post-liberalization Indian art thus works not only within the confines of academic traditions but also outside it. In this phase, artists have introduced even newer concepts which have hitherto not been seen in Indian art. Devajyoti Ray has introduced a new genre of art called Pseudorealism. Pseudorealist Art is an original art style that has been developed entirely on the Indian soil. Pseudorealism takes into account the Indian concept of abstraction and uses it to transform regular scenes of Indian life into a fantastic images.

In post-liberalization India, many artists have established themselves in the international art market like Anish Kapoor and Chintan whose mammoth artworks have acquired attention for their sheer size. Many art houses and galleries have also opened in USA and Europe to showcase Indian artworks. Some artists like chiman dangi (painter, printmaker), Bhupat Dudi, Subodh Gupta, Piu Sarkar, Vagaram Choudhary, Amitava Sengupta and many others have done magic worldwide. Chhaya Ghosh is a gifted painter, and is pretty active in Triveni Art Gallery, New Delhi.

Bombay Art Society, created on 1888

The Bombay Art Society is a Non Profit premier art organization based in Mumbai, founded in 1888. The Bombay Art Society is founded for encouraging and promoting art. Most of the renowned artists on India's art scene have been associated with the Bombay Art Society in some way.

Since 1952 the Bombay Art Society is located in the Jehangir Art Gallery with its annual exhibitions.

Bombay Contemporary India Artists' Group (« Young Turks »), 1941

Pakhal Tirumal Reddy was founder of the group Bombay Contemporary India Artists' Group (Young Turks). The Young Turks encouraged by Charles Gerrard, principal of Sir J.J. School of Art held their first exhibition in 1941. Then there were Bhabesh Sanyal and Sailoz Mookherjea, who left Calcutta. The first went to Lahore and the second came to Delhi in search of employment. These artists find prominent place in the NGMA collection[76].

The most known artists are Pakhal Tirumal Reddy, B. C. Sanyal and Sailoz Mookherjea.

Calcutta Group, founded by Subho Tagore, 1943–53

Subho Tagore, nephew of Abanindranath Tagore and Grand-nephew of Rabindranath Tagore, was a budding artist who studied art at the Governmental School of Art in Calcutta. After traveling to London for a few years in order to hone his artistic skills, he moved back to India with the idea of creating a group for plastic artists. Along with fellow painters Nirode Mazumdar, Rathin Maitra, Prankrishna Pal and Gopal Ghosh, he formally created the Calcutta Group in 1943. Later that year, another painter, Paritosh Sen, along with sculptors Pradosh Das Gupta, Kamala Das Gupta joined the society. These eight members were known as the organization's core, as well as the driving force behind it. Over the years, other artists joined the group as well including Zainul Abedin who became well known through his Famine Series paintings of 1943, Abani Sen in 1947, Gobardhan Ash in 1950, Sunil Madhav Sen in 1952, and Hemanta Mistra in 1953.

Kashi Shailee, 1947

Inspired by the vernacular painting of Uttar Pradesh (and Benares) and Indian miniature painting, the young Ram Chandra Shukla (born in 1925) created in 1947 a school called Kashi Shailee.

Bombay Progressive Artists' Group, 1947–1956

The Progressive Artists' Group was formed by six founder members, F. N. Souza, S. H. Raza, M. F. Husain, K. H. Ara, H. A. Gade, and S. K. Bakre (the only sculptor in the group). Others associated with the group included Manishi Dey, Ram Kumar, Akbar Padamsee and Tyeb Mehta.[77]

The group wished to break with the revivalist nationalism established by the Bengal school of art and to encourage an Indian avant-garde, engaged at an international level. The Group was formed just months after the 14 August 1947 "Partition of India" and Pakistan that resulted in religious rioting and death of tens of thousands of people displaced by the new borders. The founders of the Progressive Artists Group often cite "the partition" as impetus for their desire for new standards in India, starting with their new style of art.[78] Their intention was to "paint with absolute freedom for content and technique, almost anarchic, save that we are governed by one or two sound elemental and eternal laws, of aesthetic order, plastic co-ordination and colour composition."[79]

Silpi Chakra, New Delhi, 1949–68

Most of the Delhi artists from "Silpi Chakra" (Delhi Sculptor Circle) were refugees from Pakistan after the partition.

Founders : B. C. Sanyal, Nath Mago, Rai Anand Krishna, Kulkarni, Bhagat

Other artists: Satish Gujral, Ram Kumar, Kowshik, Krishen Khanna, Jaya Appasamy, Avinash Chandra[80].

Néo-tantrisme, from 1950

Tantric art is often presented as very old and very conceptual, even abstract. Initially, tantra is texts that preach rituals that are antipodes of Brahmanical purity norms, using geometric diagrams. These texts had an influence on Indian artists in the years 1950–60. They interpreted them as Indian abstract forms and then, in the climate of the Counterculture, as 'transgressive' forms to criticize Indian society from inside. We know the vogue of "oriental spirituality" on hippie movements, but we often forget the counterpart of this fashion among young Indians, especially in the arts, in painting but also poetry, dance or cinema.

Some painters, like Raza, are inspired by philosophical-mystical concepts like the point (bindu) and the spiral. The spiral turns majestically from the central bindu, its circular movement of deployment in successive turns, symbolizes in the Hindu culture the evolution of human consciousness, or the cosmic evolution of the universe. It can also be traversed in both directions, in an evolutionary or involutive direction of return to the origin. Many painters thus explored this geometric and refined aesthetic as a form of indigenous abstract art.

Baroda Group of Artists, 1956–1962