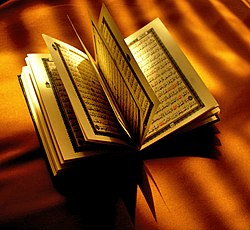

Quran

Template:QuranRelated The Qur'ān [1] (Arabic:Template:ArTemplate:ArabDIN, literally "the recitation"; also called Template:ArabDIN "The Noble Qur'ān"; also transliterated as Quran, Koran, and Al-Quran), is the central religious text of Islam. Muslims believe the Qur'ān, in its original Arabic, to be the literal word of God[2] that was revealed to Muhammad over a period of twenty-three years[3] until his death, and believe it to be God's final revelation to humanity[4][5]. Muslims regard the Qur'ān as a continuation to other divine messages that have started with those revealed to Adam - the first prophet - and including Suhuf-i-Ibrahim (Scrolls of Abraham/Ibrahim)[6], the Tawrat (Torah)[7][8], the Zabur (Psalms)[9][10], and the Injil (Gospel)[11][12][13], in between. The aforementioned books are recognized in the Qur'ān [14][15], but directs Muslims to follow the Qur'ān--the last and final message, being completely untainted with God promising to protect it: "Verily We: It is We Who have sent down the Dhikr (i.e. the Quran) and surely, We will guard it (from corruption)".[16][17]

The Qur'anic verses were originally memorized by Muhammad's companions as Muhammad recited them, with some being written down by one or more companions on whatever was at hand, from stones to pieces of bark. The collection of the Qur'ān compilation took place under the Caliph Abu Bakr, this task being led by Zayd ibn Thabit Al-Ansari. "The manuscript on which the Quran was collected, remained with Abu Bakr till Allah took him unto Him, and then with 'Umar till Allah took him unto Him, and finally it remained with Hafsa bint Umar (Umar's daughter)."[18]

Etymology

In Arabic grammar, the word "Qur'ān" (not Koran) constitutes a masdar (verbal noun) and is derived from the Arabic verb قرأ qara'a ("to read" or "to recite") which is the root.[19][20] The metre (الوزن) of this word is "فُعلان" which is a metre that indicates excessiveness, diligence or devotion in doing the act. For example, the verb غفر (ghafara), which means “to forgive” has a masdar of غفران (ghufran) which means an excessive or diligent act of forgiveness. Similarly, the word Qur'ān conveys the meaning of diligent reading. The word qur'an has been used within the Qur'ān in its generic sense of "reading", "recital", as in 75:18 (with -a accusative suffix + -hu 3rd person masculine singular possessive suffix):

- And when We read [qara'-] it, follow thou the reading [qur'ān-ahu] (Pickthall)

- But when We have promulgated [qara'-] it, follow thou its recital [qur'ān-ahu] (as promulgated) (Yusuf Ali)

The word is used in the Qur'ān as a term for the Qur'ān itself, e.g. 12:2:

- Lo! We have revealed it, a Lecture [qur'ān] in Arabic, that ye may understand. (Pickthall's translation)

- We have sent it down as an Arabic Qur'ān, in order that ye may learn wisdom. (Yusuf Ali's translation)

"Since a cultural word like "to read" can not be proto-Semitic, we may assume that it has entered Arabia, and probably from the North ... Since Syriac has, next to the verb קּרא, also the noun qeryānā, meaning both ἀνάγνωσις ("reading, reading out") and ἀνάγνωσμα ("lection, lecture"), and because of the above mentioned, the assumption of probability increases, that the term Qur'ān is not an internal Arabic development from the infinitive with the same meaning, but a borrowing from the Syriac word that has been adapted according to the type ful’ān."[21]

More recent proponents of this view include Christoph Luxenberg[22] (who takes it as evidence that the Qur'ān was itself originally a Syriac lectionary).

Format of the Qur'an

The Qur'ān consists of 114 suras of different lengths, with a total of 6236 ayat (6348 ayat counting the bismalas (q.v.)).

Each sura, or chapter, is generally known by a name derived from a key word in the text of that chapter (see List of chapter names). The chapters are not arranged in chronological order (i.e. in the order in which Islamic scholars believe they were revealed) but roughly descending by size, to aid oral memory (e.g. see Sura 54 Ayah 17).

- Index of the Qur'ān

- Qur'ān Verses in Chronological Order

- Qur'ān Verses in Traditional Order

- Qur'ān Verses in Alphabetical Order

- Qur'ān Chapters & Verses Numerical Structure

Divsions: Hizb or Manzil

Hizb or Manzil is the group of Suras excluding Surah Al Fatiha, the first chapter. Seventh Hizb consisting sixty-five suras is also called as Hizb Mufassil.

- Manzil 1 = 3 Sura

- Manzil 2 = 5 Sura

- Manzil 3 = 7 Sura

- Manzil 4 = 9 Sura

- Manzil 5 = 11 Sura

- Manzil 6 = 13 Sura

- Manzil 7 = 65 Sura

Literary structure of the Qur'ān

Issa Boullata, professor of Arabic literature and Islamic studies at McGill University, gives the following evaluation of the literary structure of the Qur'ān: [23]

The message of the Qur'an is couched in various literary structures, which are widely considered to be the most perfect written text in Arabic. Arabic grammars were written based upon the qur'anic language, and, by general consensus of Muslim rhetoricians, the qur'anic idiom is considered to be sublime... In conclusion, it can be said that the Qur'an utilizes a wide variety of literary devices to convey its message. In its original Arabic idiom, the individual components of the text — surahs and ayat — employ phonetic and thematic structures that assist the audience’s efforts to recall the message of the text. Whereas the scholars of Arabic are largely agreed that the Qur'an represents the standards by which other literary productions in Arabic are measured, believing Muslims maintain that the Qur'an is inimitable with respect to both content and style.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Influence of the Qur'an on the Arabic literature

Wadad Kadi, Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at University of Chicago and Mustansir Mir, Professor of Islamic studies at Youngstown State University state that: [24]

Although Arabic, as a language and a literary tradition, was quite well developed by the time of Muhammad's prophetic activity, it was only after the emergence of Islam, with its founding scripture in Arabic, that the language reached its utmost capacity of expression, and the literature its highest point of complexity and sophistication. Indeed, it probably is no exaggeration to say that the Qur'an was one of the most conspicuous forces in the making of classical and post-classical Arabic literature.

The main areas in which the Qur'an exerted noticeable influence on Arabic literature are diction and themes; other areas are related to the literary aspects of the Qur'an particularly oaths (q.v.), metaphors, motifs, and symbols. As far as diction is concerned, one could say that qur'anic words, idioms, and expressions, especially "loaded" and formulatic phrases, appear in practically all genres of literature and in such abundance that it is simply impossible to compile a full record of them. For not only did the Qur'an create an entirely new linguistic corpus to express its message, it also endowed old, pre-Islamic words with new meanings and it is these meanings that took root in the language and subsequently in the literature...

Origin and development of the Qur'ān

The neutrality of this section is disputed. |

Some modern Western historians have concluded that Muhammad was sincere in his claim of receiving revelation, "for this alone makes credible the development of a great religion." [25] Modern historians generally decline to address the further question of whether the messages Muhammad reported being revealed to him were from "his unconscious, the collective unconscious functioning in him, or from some divine source", but they acknowledge that the material came from "beyond his conscious mind" [26]

According to the Qur'ān:

"This Qur'ān is not such as can be produced by other than Allah; on the contrary it is a confirmation of (revelations) that went before it, and a fuller explanation of the Book - wherein there is no doubt - from the Lord of the worlds. Or do they say, "He forged it"? Say: "Bring then a Sura like unto it, and call (to your aid) anyone you can besides Allah, if it be ye speak the truth!"10:37&38 "

Some non-Muslims say that the Qur'ān originated and derived from the Bible. Although the Qur'ān itself confirms the similarity between it and the former books (the Torah and the Gospel)3:3, it tells that:

"We know indeed that they say, "It is a man that teaches him." The tongue of him they wickedly point to is notably foreign, while this is Arabic, pure and clear. 16:103"

The Qur'ān attributes this similarity to their unique origin and says all of them have been revealed by the God.2:285 Based on Islamic traditions and legends, it is generally believed that Muhammad could neither read nor write, but would simply recite what was revealed to him for his companions to write down and memorize. According to the Qur'ān

"And thou wast not (able) to recite a Book before this (Book came), nor art thou (able) to transcribe it with thy right hand: In that case, indeed, would the talkers of vanities have doubted.29:48 " "Say: "If Allah had so willed, I should not have rehearsed it to you, nor would He have made it known to you. A whole life-time before this have I tarried amongst you: will ye not then understand?"10:16 "

However some scholars - (Christoph Luxenberg, Maxime Rodinson, William Montgomery Watt, etc.) - have argued that this claim is based on weak traditions and that, in regard of many aspects concerning Muhammad's biography and teachings, it is not convincing:

"The Meccans were in general familiar with reading and writing. A certain amount of writing would be necessary for commercial purposes ... In view of this familiarity with writing among the Meccans particularly, both for records and for religious scriptures, there is a presumption that Muhammad knew at least enough to keep commercial records ... The probability is that Muhammad was able to read and write sufficiently for business purposes, but it seems certain that he had not read any [religious] scriptures." - W. Montgomery Watt in "Muhammad's Mecca"[27]

"Whatever Arabic tradition may have assumed from a wrong interpretation of a word in the Koran, it seems certain that Muhammad learned to read and write. But except for a few vague and unreliable pointers in his life and work we have no way of knowing the extent of his learning." - M. Rodinson in "Mohammed"[28]

Adherents to Islam hold that the wording of the Qur'anic text available today corresponds exactly to that revealed to Muhammad himself: words of God said to be delivered to Muhammad through the angel Gabriel. The Qur'ān is not only considered by Muslims to be a guide but also as a sign of the prophethood of Muhammad and the truth of the religion. Muslims argue that it is not possible for a human to produce a book like the Qur'an. According to the Qur'ān

"And if ye are in doubt as to what We have revealed from time to time to Our servant, then produce a Sura like thereunto; and call your witnesses or helpers (If there are any) besides Allah, if your (doubts) are true. But if ye cannot- and of a surety ye cannot- then fear the Fire whose fuel is men and stones,- which is prepared for those who reject Faith. "2:23&24

Some non-muslim scholars accept a similar account, but without accepting any supernatural claims: they say that Muhammad put forth verses and laws that he claimed to be of divine origin; that his followers memorized or wrote down his revelations; that numerous versions of these revelations circulated after his death in 632 CE, and that first Abu Bakr ordered its compilation and then Uthman ordered the collection and ordering of this mass of material circa 650-656. These scholars point to many attributes of the Qur'ān as indicative of a human collection process that was extremely respectful of a miscellaneous collection of original texts.

Other scholars have proposed that some development of the text of the Qur'ān took place after the death of Muhammad and before the currently accepted version of the Qur'ān stabilized. Western academic scholars associated with such theories include John Wansbrough, Patricia Crone, Michael Cook, Christoph Luxenberg, and Gerd R. Puin.

Another scholar, James A. Bellamy, has proposed some emendations to the text of the Qur'ān.

The language of the Qur'ān

The Qur'ān was one of the first texts written in Arabic. It is written in the classical Arabic which is also the Arabic of pre-Islamic poetry including the Mu'allaqat, or Suspended Odes. With the coming of the Qur'ān, the Arabic language reached its pinnacle.

Soon after Muhammad's death in 632 CE, armies led by his followers burst out of Arabia and conquered the Near East, Northern Africa, Central Asia, and parts of Europe. Arab rulers had millions of foreign subjects, with whom they had to communicate. Thus, the language rapidly changed in response to this new situation, losing complexities of case and obscure vocabulary. Several generations after the prophet's death, many words used in the Qur'ān had become opaque to ordinary sedentary Arabic-speakers, as Arabic had changed so much, so rapidly. The Bedouin speech changed at a considerably slower rate, however, and early Arabic lexicographers sought out Bedouin speech as well as pre-Islamic poetry to explain difficult words or elucidate points of grammar. Partly in response to the religious need to explain the Qur'an to Muslims who were not familiar with Qur'anic Arabic, Arabic grammar and lexicography soon became important sciences. The model for the Arabic literary language remains to this day the speech used in Qur'anic times, rather than the current spoken dialects.[citation needed]

The Qur'ān for reading and recitation

In addition to and largely independent of the division into surahs, there are various ways of dividing the Qur'ān into parts of approximately equal length for convenience in reading, recitation and memorization. The Qur'ān is divided to thirty ajza' (parts). The thirty parts can be used to work through the entire Qur’an in a week or a month. Some of these parts are known by names and these names are the first few words by which the Juz starts. A juz' is sometimes further divided into two ahzab (groups), and each hizb is in turn subdivided into four quarters. A different structure is provided by the ruku'at (sing. Raka'ah), semantical units resembling paragraphs and comprising roughly ten ayat each. Some also divide the Qur'ān into seven manazil (stations).

A hafiz is one who has memorized the entire text of the Qur'ān, and is able to recite it properly (Tajweed). All Muslims must memorize at least some parts of the Qur'ān, in order to perform their daily prayers.

Qur'ān recitation

The very word Qur'ān is usually translated as "recital," indicating that it cannot exist as a mere text. It has always been transmitted orally as well as textually.

To even be able to perform salat (prayer), a mandatory obligation in Islam, a Muslim is required to learn at least some suras of the Qur'ān (typically starting with the first sura, al-Fatiha, known as the "seven oft-repeated verses," and then moving on to the shorter ones at the end). Until one has learned al-Fatiha, a Muslim can only say phrases like "praise be to God" during the salat.

A person whose recital repertoire encompasses the whole Qur'ān is called a qari' (قَارٍئ) or hafiz (which translate as "reciter" or "protector," respectively). Muhammad is regarded as the first hafiz. Recitation (tilawa تلاوة) of the Qur'ān is a fine art in the Muslim world.

Schools of recitation

There are several schools of Qur'anic recitation, all of which are permissible pronunciations of the Uthmanic rasm. Today, ten canonical and at least four uncanonical recitations of the Qur'ān exist. For a recitation to be canonical it must conform to three conditions:

- It must match the rasm, letter for letter.

- It must conform with the syntactic rules of the Arabic language.

- It must have a continuous isnad to Muhammad through tawatur, meaning that it has to be related by a large group of people to another down the isnad chain.

Ibn Mujahid documented seven such recitations and Ibn Al-Jazri added three. They are:

- Nafi` of Madina (169/785), transmitted by Warsh and Qaloon

- Ibn Kathir of Makka (120/737), transmitted by Al-Bazzi and Qonbul

- Ibn `Amer of Damascus (118/736), transmitted by Hisham and Ibn Zakwan

- Abu `Amr of Basra (148/770), transmitted by Al-Duri and Al-Soosi

- `Asim of Kufa (127/744), transmitted by Sho`bah and Hafs

- Hamza of Kufa (156/772), transmitted by Khalaf and Khallad

- Al-Kisa'i of Kufa (189/804), transmitted by Abul-Harith and Al-Duri

- Abu-Ja`far of Madina, transmitted by Ibn Wardan and Ibn Jammaz

- Ya`qoob of Yemen, transmitted by Ruways and Rawh

- Khalaf of Kufa, transmitted by Ishaaq and Idris

These recitations differ in the vocalization (tashkil تشكيل) of a few words, which in turn gives a complementary meaning to the word in question according to the rules of Arabic grammar. For example, the vocalization of a verb can change its active and passive voice. It can also change its stem formation, implying intensity for example. Vowels may be elongated or shortened, and glottal stops (hamzas) may be added or dropped, according to the respective rules of the particular recitation. For example, the name of archangel Gabriel is pronounced differently in different recitations: Jibrīl, Jabrīl, Jibra'īl, and Jibra'il. The name "Qur'ān" is pronounced without the glottal stop (as "Qurān") in one recitation, and prophet Abraham's name is pronounced Ibrāhām in another. The more widely used narrations are those of Hafs (حفص عن عاصم), Warsh (ورش عن نافع), Qaloon (قالون عن نافع) and Al-Duri according to Abu `Amr (الدوري عن أبي عمرو). Muslims firmly believe that all canonical recitations were recited by the Prophet himself, citing the respective isnad chain of narration, and accept them as valid for worshipping and as a reference for rules of Sharia. The uncanonical recitations are called "explanatory" for their role in giving a different perspective for a given verse or ayah. Today several dozen persons hold the title "Memorizer of the Ten Recitations." This is considered to be a great accomplishment among the followers of Islam.

The presence of these different recitations is attributed to many hadith. Malik Ibn Anas has reported:[29]

- Abd al-Rahman Ibn Abd al-Qari narrated: “ Umar Ibn Khattab said before me: I heard Hisham Ibn Hakim Ibn Hizam reading Surah Furqan in a different way from the one I used to read it, and the Prophet (sws) himself had read out this surah to me. Consequently, as soon as I heard him, I wanted to get hold of him. However, I gave him respite until he had finished the prayer. Then I got hold of his cloak and dragged him to the Prophet (sws). I said to him: “I have heard this person [Hisham Ibn Hakim Ibn Hizam] reading Surah Furqan in a different way from the one you had read it out to me.” The Prophet (sws) said: “Leave him alone [O ‘Umar].” Then he said to Hisham: “Read [it].” [Umar said:] “He read it out in the same way as he had done before me.” [At this,] the Prophet (sws) said: “It was revealed thus.” Then the Prophet (sws) asked me to read it out. So I read it out. [At this], he said: “It was revealed thus; this Qur'ān has been revealed in Seven Ahruf. You can read it in any of them you find easy from among them.

Suyuti, a famous 15th century Islamic theologian, writes after interpreting above hadith in 40 different ways:[30]

And to me the best opinion in this regard is that of the people who say that this Hadith is from among matters of mutashabihat, the meaning of which cannot be understood.

Many reports contradict presence of variant readings:[31]

- Abu Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami reports, "the reading of Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Zayd ibn Thabit and that of all the Muhajirun and the Ansar was the same. They would read the Qur’an according to the Qira’at al-‘ammah. This is the same reading which was read out twice by the Prophet (sws) to Gabriel in the year of his death. Zayd ibn Thabit was also present in this reading [called] the ‘Ardah-i akhirah. It was this very reading that he taught the Qur’an to people till his death".[32]

- Ibn Sirin writes, "the reading on which the Qur’an was read out to the prophet in the year of his death is the same according to which people are reading the Qur’an today".[33]

Javed Ahmad Ghamidi also purports that there is only one recitation of Qur'ān, which is called Qira’at of Hafs or in classical scholarship, it is called Qira’at al-‘ammah. The Qur'ān has also specified that it was revealed in the language of the prophet's tribe: the Quraysh ([Quran 19:97], [Quran 44:58]).[31]

Writing and printing the Qur'ān

Most Muslims today use printed editions of the Qur'ān. There are many editions, large and small, elaborate or plain, expensive or inexpensive [5]. Bilingual forms with the Arabic on one side and a gloss into a more familiar language on the other are very popular.

Qur'āns are produced in many different sizes, from extremely large Qur'āns [6] for display purposes, to extremely small Qur'āns [7].

Qur'āns were first printed from carved wooden blocks, one block per page. There are existing specimen of pages and blocks dating from the 10th century CE. Mass-produced less expensive versions of the Qur'an were later produced by lithography, a technique for printing illustrations. Qur'ans so printed could reproduce the fine calligraphy of hand-made versions.

The oldest surviving Qur'ān for which movable type was used was printed in Venice in 1537/1538. It seems to have been prepared for sale in the Ottoman empire. Catherine the Great of Russia sponsored a printing of the Qur'ān in 1787. This was followed by editions from Kazan (1828), Persia (1833) and Istanbul (1877) [8].

It is extremely difficult to render the full Qur'ān, with all the points, in computer code, such as Unicode. The Internet Sacred Text Archive makes computer files of the Qur'ān freely available both as images [9] and in a temporary Unicode version [10]. Various designers and software firms have attempted to develop computer fonts that can adequately render the Qur'ān. See [11] for one such commercial font.

Before printing was widely adopted, the Qur'ān was transmitted by copyists and calligraphers. Since Muslim tradition felt that directly portraying sacred figures and events might lead to idolatry, it was considered wrong to decorate the Qur'ān with pictures (as was often done for Christian texts, for example). Muslims instead lavished love and care upon the sacred text itself. Arabic is written in many scripts, some of which are both complex and beautiful. Arabic calligraphy is a highly honored art, much like Chinese calligraphy. Muslims also decorated their Qur'āns with abstract figures (arabesques), colored inks, and gold leaf. Pages from some of these antique Qur'āns are displayed throughout this article.

Some Muslims believe that it is not only acceptable, but commendable to decorate everyday objects with Qur'anic verses, as daily reminders. Other Muslims feel that this is a misuse of Qur'anic verses; those who handle these objects will not have cleansed themselves properly and may use them without respect.

The challenge provided by the Qur'ān

Template:Cleanup-sect The Islamic viewpoint is that the Qur'ān is not only unique in the way in which it presents its subject matter, but it is also unique in that it is a miracle in itself ("miracle", meaning the performance of a supernatural or extraordinary event which cannot be duplicated by humans). It has been documented that Muhammad challenged the Arabs to produce a literary work of a similar caliber as the Qur'ān. The Arabs were unable to do so in spite of their well-known eloquence and literary abilities. The challenge to reproduce the Qur'ān was presented to the Arabs and mankind in three stages:

- The First Stage

A challenge is made to all of mankind to create a book of the stature of the Qur'ān,

"Say: 'If all mankind and the jinn would come together to produce the like of this Qur'ān, they could not produce its like even though they exerted all and their strength in aiding one another.’" (Qur'ān 17:88)

- The Second Stage

Next, a challenge is made, asking those who denied the divine origin of the Qur'ān to imitate ten surahs of the Qur'ān:

"Or do they say that he has invented it? Say (to them), 'Bring ten invented surahs like it, and call (for help) on whomever you can besides Allah, if you are truthful." (Qur’an 11:13)

- The Third Stage

This final challenge was to produce a single surah to match what is in the Qur'ān:

"And if you all are in doubt about what I have revealed to My servant, bring a single surah like it, and call your witnesses besides Allah if you are truthful." (Qur'ān 2:23)

The shortest chapter of the Qur'ān is Surah al-Kawthar (Chapter 108) which consists of three verses.

A number of Qurayshee orators and poets tried to imitate the Qur'ān, but failed (see Banu Quraish). Attempts to forge chapters of the Qur'ān have been made throughout the ages, yet none have withstood close scrutiny.

The actual challenge

The challenge is to produce in Arabic, three lines, that:

- do not fall into any of the sixteen recognized types of meters of rhymed poetry in the Arabic language (i.e. at-Tawil, al-Bassit, al-Wafir, al-Kamil, ar-Rajs, al-Khafif, al-Hazaj, al-Muttakarib, al-Munsarih, al-Muktatab, al-Muktadarak, al-Madid, al-Mujtath, al-Ramel, al-Khabab and as-Saria')(see Meter (poetry)); and

- is not rhyming prose; and

- is not like the speech of soothsayers; and

- is not normal speech; and

- contains at least a comprehensible meaning and rhetoric (i.e. not gobbledygook).

Some non-Muslims from modern and pre-modern times have claimed to have met the challenge presented by the Qur'ān by producing surahs of their own.[34] Muslims dismiss these attempts, explaining that such proposals do not match the style of the Qur'ān at all.[35]

Translations of the Qur'ān

The Qur'ān has been translated into many languages, including English. These translations are considered to be glosses for personal use only, and have no weight in serious religious discussion. Translation is an extremely difficult endeavor, because each translator must consult his or her own opinions and aesthetic sense in trying to replicate shades of meaning in another language; this inevitably changes the original text. Thus a translation is often referred to as an "interpretation," and is not considered a real Qur'ān. Just as Jewish and Christian scholars turn to the earliest texts, in Hebrew or Greek, when it is a question of exactly what is meant by a certain passage, so Muslim scholars turn to the Qur'ān in Arabic.

The first translator of the Qur'ān was Salman the Persian. He was one of Mohammed's nearest companions and translated the Qur'an during the 7th century - some of the people of Persia asked Salman al-Farisi to write to them something of the Qur'ān, and he wrote to them the Fatihah in Persian.[36]

Robert of Ketton was the first person to translate the Qur'ān into a Western language, Latin, in 1143.[37] Alexander Ross offered the first English version in 1649. In 1734, George Sale produced the first scholarly translation of the Qur'ān into English; another was produced by Richard Bell in 1937, and yet another by Arthur John Arberry in 1955. All these translators were non-Muslims. There have been numerous translation by Muslims; the most popular of these are the translations by Dr. Muhammad Muhsin Khan, Dr. Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din al Hilali, Maulana Muhammad Ali, Abdullah Yusuf Ali, M. H. Shakir, Muhammad Asad, and Marmaduke Pickthall.

The English translators have sometimes favored archaic English words and constructions over their more modern or conventional equivalents; thus, for example, two widely-read translators, A. Yusuf Ali and M. Marmaduke Pickthall, use the plural and singular "ye" and "thou" instead of the more common "you." Another common stylistic decision has been to refrain from translating "Allah" — in Arabic, literally, "The God" — into the common English word "God." These choices may differ in more recent translations.

Interpretation of the Qur'ān

The Qur'ān has sparked a huge body of commentary and explication. According to Allameh Tabatabaei, interpretation of the Qur'ān (Tafsir) means "explaining the meanings of the Qur'anic verse, clarifying its import and finding out its significance."[38]

Tafsir is one of the earliest academic activities in Islam. The prophet was the first person who described the Ayats for Muslims, as is clear from the words of Allah:" A similar (favour have ye already received) in that We have sent among you a Messenger of your own, rehearsing to you Our Signs, and sanctifying you, and instructing you in Scripture[Qur'ān] and Wisdom, and in new knowledge2:151."

The first exegetes were a few Companions of the Prophet, like Abdullah ibn Abbas, Abdullah ibn Umar and Ubayy ibn Kab . Exegesis in those days was confined to the explanation of literary aspects of the verse, the background of its revelation and, occasionally, interpretation of one verse with the help of the other. If the verse was about a historical event, then sometimes a few traditions of the Prophet were narrated to make its meaning clear. [39]

Because Qur'ān is spoken in the classical form of Arabic, many of the later converts to Islam, who happened to be mostly non-Arabs, did not always understand the Qur'ān's Arabic, they did not catch allusions that were clear to early Arab Muslims and they were extremely concerned to reconcile apparent contradictions and conflicts in the Qur'an. Commentators erudite in Arabic explained the allusions, and perhaps most importantly, explained which Qur'anic verses had been revealed early in Muhammad's prophetic career, as being appropriate to the very earliest Muslim community, and which had been revealed later, canceling out or "abrogating" (nāsikh) the earlier text. Memories of the occasions of revelation (asbāb al-nuzūl), the circumstances under which Muhammad had spoken as he did, were also collected, as they were believed to explain some apparent obscurities. Although the concept of abrogation does exist in the Qur'ān, Muslims differ in their interpretaions of the word "Abrogation". Some believe that there are abrogations in the text of the Qur'ān and some insist that there are no contradictions or unclear passages to explain.

Similarities between the Qur'ān and the Bible

The Qur'ān retells stories of many of the people and events recounted in Jewish and Christian sacred books (Tanakh, Bible) and devotional literature (Apocrypha, Midrash), although it differs in many details. Adam, Enoch, Noah, Heber, Shelah, Abraham, Lot, Ishmael, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Job, Jethro, David, Solomon, Elijah, Elisha, Jonah, Aaron, Moses, Zechariah, Jesus, and John the Baptist are mentioned in the Qur'an as prophets of God (see Prophets of Islam). Muslims believe the common elements or resemblances between the Bible and other Jewish and Christian writings and Islamic dispensations is due to the common divine source, and that the Christian or Jewish texts were authentic divine revelations given to prophets. According to the Qur'ān

"It is He Who sent down to thee (step by step), in truth, the Book, confirming what went before it; and He sent down the Law (of Moses) and the Gospel (of Jesus) before this, as a guide to mankind, and He sent down the criterion (of judgment between right and wrong).3:3 "

Muslims claim that those texts were neglected or corrupted (tahrif) by the Jews and Christians and have been replaced by God's final and perfect revelation, which is the Qur'ān.[40] However, many Jews and Christians believe that the historical biblical archaeological record refutes this assertion, because the Dead Sea Scrolls (the Tanakh and other Jewish writings which predate the origin of the Qur'an) have been fully translated,[41] validating the authenticity of the Greek Septuagint.[42]

The Qur'ān and Islamic culture

Based on tradition and a literal interpretation of sura 56:77-79: "That this is indeed a Qur'ān Most Honourable, In a Book well-guarded, Which none shall touch but those who are clean.", many scholars opine that a Muslim perform wudu (ablution or a ritual cleansing with water) before touching a copy of the Qur'ān, or mushaf. This view has been contended by other scholars on the fact that, according to Arabic linguistic rules, this verse alludes to a fact and does not comprise an order. The literal translation thus reads as "That (this) is indeed a noble Qur'ān, In a Book kept hidden, Which none toucheth save the purified," (translated by Mohamed Marmaduke Pickthall). It is suggested based on this translation that performing ablution is not required.

Qur'an desecration means insulting the Qur'ān by defiling or dismembering it. Muslims must always treat the book with reverence, and are forbidden, for instance, to pulp, recycle, or simply discard worn-out copies of the text. Respect for the written text of the Qur'ān is an important element of religious faith by many Muslims. They believe that intentionally insulting the Qur'ān is a form of blasphemy. According to the laws of some Muslim-majority countries, blasphemy is punishable by lengthy imprisonment or even the death penalty.

- See also: Qur'an desecration controversy of 2005

Criticism of the Qur'ān

Due to the rise of Islamic terrorism, the need to understand the motives of suicide bombers has become important to many. Some critics believe that it is not only extremist Islam that preaches violence but Islam itself, a violence critics say is implicit in the Qur'anic text. [43][44] In response to criticism, it is generally argued that critics have taken verses out of context. The verses should be read with the whole surah; also the time and circumstances of the verses should be considered.[45] [46]

Muslims generally argue that the Qur'ān is the literal word of God. Critics reject the idea of a divine origin[47][48][49] , and base their argument on the problems they see in the Qur'ān, both textually and morally.[50][51]

See also

- Qur'an and miracles

- Qur'an and Sunnah

- Origin and development of the Qur'an

- Qur'an reading

- Hafiz

- Qur'anic literalism

- Sura

- Ayat

- Tafsir

- Women in Quran

- Persons related to Qur'anic verses

- Esoteric interpretation of the Qur'an

- Islam

- Criticism of Islam

- There are also articles on each of the suras, or chapters, of the Qur'ān. Click on a chapter number to view the article.

References

- ^

- ^ Qur'ān, Chapter 2, Verses 23-24

- ^ Qur'an, Chapter 17, Verse 106

- ^ Qur'an, Chapter 33, Verse 40

- ^ Watton, Victor, (1993), A student's approach to world religions:Islam, Hodder & Stoughton, pg 1. ISBN 0-340-58795-4

- ^ Qur'ān Chapter 87, Verses 18-19

- ^ Qur'ān, Chapter 3, Verse 3

- ^ Qur'ān, Chapter 5, Verse 44

- ^ Qur'ān, Chapter 4, Verse 163

- ^ Qur'ān, Chapter 17, Verse 55

- ^ Qur'ān, Chapter 5, Verse 46

- ^ Qur'ān, Chapter 5, Verse 110

- ^ Qur'ān, Chapter 57, Verse 27

- ^ Qur'ān, Chapter 3, Verse 84

- ^ Quran, Chapter 4, Verse 136

- ^ Qur'ān, Chapter 15, Verse 9

- ^ Qur'ān Chapter 5, Verse 46

- ^ Sahih Bukhari, Volume 6, Book 60, Number 201

- ^ BYU Studies, vol. 40, number 4, 2001. Page 52

- ^ Lisan al-Arab[1]

- ^ Da nun ein Kulturwort wie "lesen" nicht ursemitisch sein kann, so dürfen wir annehmen, daß es in Arabien eingewandert ist, und zwar wahrscheinlich aus dem Norden...Da nun das Syrische neben dem Verbum קּרא das Nomen qeryānā hat, und zwar in der doppelten Bedeutung ἀνάγνωσις (das Lesen, Vorlesen) und ἀνάγνωσμα (Lesung, Lektüre), so gewinnt, im Zusammenhange mit dem eben Erörteten, die Vermutung an Wahrscheinlichkkeit, daß der Terminus Qorän nicht eine innerarabische Entwicklung aus dem gleichbedeutenden Infinitive ist, sondern eine Entlehnung aus jenem syrischen Worte unter gleichzeitiger Angleichung an Typus ful’ān." Nöldeke, Theodor (1860) Geschichte des Qorâns. Göttingen. Part I, page 33.

- ^ Luxenberg, Christoph (2004) -- Die Syro-Aramäische Lesart des Koran: Ein Beitrag zur Entschlüsselung der Koransprache. Berlin: Verlag Hans Schiler. 20054 ISBN 3-89930-028-9. Page 81-84.

- ^ Issa Boullata, Literary Structure of Qur'an, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, vol.3 p.192, 204

- ^ Wadad Kadi and Mustansir Mir, Literature and the Qur'an, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, vol. 3, pp. 213, 216

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam (1970), Cambridge University Press, p.30

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam (1970), Cambrdige University Press, p.30

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, "Muhammad's Mecca", Chapter 3: "Religion In Pre-Islamic Arabia", p. 26-52

- ^ Maxime Rodinson, "Mohammed", translated by Anne Carter, p. 38-49, 1971

- ^ Malik Ibn Anas, Muwatta, vol. 1 (Egypt: Dar Ahya al-Turath, n.d.), 201, (no. 473).

- ^ Suyuti, Tanwir al-Hawalik, 2nd ed. (Beirut: Dar al-Jayl, 1993), 199.

- ^ a b Javed Ahmad Ghamidi. Mizan, Principles of Understanding the Qu'ran, Al-Mawrid

- ^ Zarkashi, al-Burhan fi Ulum al-Qur'ān, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, 1980), 237.

- ^ Suyuti, al-Itqan fi Ulum al-Qur'ān, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Baydar: Manshurat al-Radi, 1343 AH), 177.

- ^ Answering-Islam.org - "Is the Qur'ān Miraculous"? - Website presenting examples it claims meet the challenge of the Qur'ān

- ^ Islamic-Awareness.org - The Challenge of the Qur'ān Website responding to some of the proposed surahs

- ^ An-Nawawi, Al-Majmu', (Cairo, Matbacat at-'Tadamun n.d.), 380.

- ^ Islam: A Thousand Years of Faith and Power. New Haven: Yale University Press. 2002. pp. p. 42.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Preface of Al'-Mizan

- ^ [2]

- ^ Bernard Lewis, The Jews of Islam (1984). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00807-8. p.69

- ^ The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: The Oldest Known Bible Translated for the First Time into English (2002) HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 0-06-060064-0

- ^ http://www.septuagint.net

- ^ Robert Spencer. Onward Muslim Soldiers, page 121.

- ^ [3]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Boundries_Princetonwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Khaleel Muhammad, professor of religious studies at San Diego State University regarding his discussion with the critic Robert Spencer states that "when I am told ... that Jihad only means war, or that I have to accept interpretations of the Quran that non-Muslims (with no good intentions or knowledge of Islam) seek to force upon me, I see a certain agendum developing: one that is based on hate, and I refuse to be part of such an intellectual crime." [4]

- ^ Koran, by Gabriel Oussani, The Catholic Encyclopedia, retrieved April 13, 2006

- ^ Patricia Crone, Michael Cook, and Gerd R. Puin as quoted in Toby Lester (January 1999). "What Is the Koran?". The Atlantic Monthly.

- ^ Jewish Encyclpoedia: comp. also xvi. 70

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Religion, By Mircea Eliade. Volum 12 pg. 165-6, pub. 1987 ISBN 0-02-909700-2

- ^ Robert Spencer. Onward Muslim Soldiers,

Translations

- Arberry, A. J. -- The Koran Interpreted, Touchstone Books, 1996. ISBN 0-684-82507-4

- Online Translations and Recitations of the Qur'ān

Older commentary

- al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir -- Jami‘ al-bayān `an ta'wil al-Qur'ān, Cairo 1955-69, transl. J. Cooper (ed.), The Commentary on the Qur'an, Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-19-920142-0

Older scholarship

- Nöldeke, Theodor -- Geschichte des Qorâns, Göttingen, 1860.

Recent scholarship

- Al-Azami, M. M. -- The History of the Qur'anic Text from Revelation to Compilation, UK Islamic Academy: Leicester 2003.

- Bellamy, James A. -- "Some Proposed Emendations to the Text of the Koran", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 113, 1993

- Bellamy, James A. -- "More Proposed Emendations to the Text of the Koran", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 116, 1996

- Bellamy, James A. -- "Textual Criticism of the Koran", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 121, 2001

- Crone, Patricia, and Michael Cook -- Hagarism, Cambridge University Press, 1977

- Gatje, Helmut, and Alford T. Welch -- The Qur'an and Its Exegesis, Oneworld Publications; New Ed edition (November 1, 1996). ISBN 1-85168-118-3

- Ibn Warraq (ed.), The Origins of the Koran, Prometheus Books, 1998. ISBN 1-57392-198-X

- Kassis, Hanna E. -- A Concordance of the Qur'an, University of California Press (March 1, 1984), ISBN 0-520-04327-8

- Luxenberg, Christoph (2004) -- Die Syro-Aramäische Lesart des Koran: Ein Beitrag zur Entschlüsselung der Koransprache, Berlin, Verlag Hans Schiler, 2005, ISBN 3-89930-028-9

- McAuliffe, Jane Damen -- Quranic Christians : An Analysis of Classical and Modern Exegesis, Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-521-36470-1

- McAuliffe, Jane Damen (ed.) -- Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an, Brill, 2002-2004.

- Puin, Gerd R. -- "Observations on Early Qur'an Manuscripts in Sana'a," in The Qur'an as Text, ed. Stefan Wild, , E.J. Brill 1996, pp. 107-111 (as reprinted in What the Koran Really Says, ed. Ibn Warraq, Prometheus Books, 2002)

- Rahman, Fazlur -- Major Themes in the Qur'an, Bibliotheca Islamica, 1989. ISBN 0-88297-046-1

- Robinson, Neal, Discovering the Qur'an, Georgetown University Press, 2002. ISBN 1-58901-024-8

- Sells, Michael, -- Approaching the Qur'an: The Early Revelations, White Cloud Press, Book & CD edition (November 15, 1999). ISBN 1-883991-26-9

- Stowasser, Barbara Freyer -- Women in the Qur'an, Traditions, and Interpretation, Oxford University Press; Reprint edition (June 1, 1996), ISBN 0-19-511148-6

- Wansbrough, John -- Quranic Studies, Oxford University Press, 1977

- Watt, W. M., and R. Bell, Introduction to the Qur'an, Edinburgh University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-7486-0597-5

External links

- Who Wrote the Quran

- www.Al-Islam.org Discover Islam

- The Inimitable Qur'ān

- English and Arabic Video of the Qur'ān

- Qur'ān directory at DMOZ

- Free Quran RSS feeds

- Compilation of the Qur'ān

- Holy Qur'ān Meaning Translations in Different Languages

- Reading Qur'ān

- Learning Qurān

- Themes in the Qur'ān

- Tafsir of selected verses of the Qur'ān

- The Amazing Quran by Gary Miller

Translations

- Noble Quran: Hilali Translation

- www.Al-Islam.org Text, Translation, and Commentaries of the Quran

- Irfan-ul-Quran Urdu translation of the holy Qur'ān by Shaykh-ul-Islam Dr Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri

- http://www.kuran.gen.tr - Qur'ān Translation (21 languages)

- The Qur'an at the Internet Sacred Text Archive

- www.SearchTruth.com Translation of the Qur'ān in French, Spanish, German, Arabic, English, Indonesian, Melayu and Urdu

- Most Sacred Qur'ān of One Islam - One-Islam.Org. A holy translation of the Qur'ān.

- Islamawakened - ayat-by-ayat transliteration and parallel translations from eleven prominent translators.

- The Qur'an - three translations (Yusuf Ali, Shakir, and Pickthal). Also, Abul Ala Maududi's chapter introductions to the Qur'ān.

- The Qur'an - translated by Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din Al Hilali, and Muhammad Muhsin Khan. An English translation endorsed by the Saudi government. Includes Arabic commentary by Ibn Katheer, Tabari, and Qurtubi.

- The Message - Free Minds / Progressive Muslims - a literal translation of the Qur'an.

- Quran Resources - Translation of the Qur'ān.

- Online translation of the Qur'ān — translated by a team of Muslim scholars including the first woman to translate the Qur'ān into English.

- Qur'ān Search in Foreign Languages

- Translations of The Holy Quran 6 Languages and commentary of selected verses

Search

- Text In Motion, concordance searchable by root or by grammatical form.

- Search the Holy Qur'ān in Urdu, English, Arabic, Melayu, Indonesian, French, Spanish and German at www.SearchTruth.com

- Irfan-ul-Qur'ān Search holy Qur'ān in Arabic and Urdu

- Search the Qur'ān

- Qur'ān Search or browse the English Shakir translation

- MSA Qur'ān search

- Qur'ān Search

Manuscripts

Audio/Video

- Irfan-ul-Quran.com Qur'ān recitation in the voices of 12 most popular Qura of the world

- Qur'ān recitations by 271 different reciters

- Videos of recitation, commentary, or prayer

- English audio recitation/translation of the Qur'ān

- English Reading

- Alquranic.com

- Reciter.org

- King Fahd Complex

- Introduction (What is Qur'ān, Its Subject, Its mode of speech, Its collection and compilation ....) (English)

- Translation and Short Explanation to Qur'ān (English)

- Audio Tafseer of selected Chapters of Quran

- http://www.qquran.com/

- http://www.quran-voice.com

- Quran Recitation Interactive Tutorials - Internet Explorer Only for Interactivity