Flagstaff, Arizona

- This article is about the U.S. city in the state of Arizona. For other uses, see Flagstaff (disambiguation).

Flagstaff, Arizona | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname: City of Seven Wonders | |

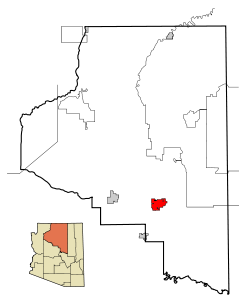

Location in Coconino County the state of Arizona | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| County | Coconino County |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Joseph C. Donaldson |

| Area | |

| • City | 98.3 sq mi (164.8 km2) |

| • Land | 63.6 sq mi (164.7 km2) |

| • Water | 0.1 sq mi (0.04 km2) |

| Elevation | 6,910 ft (2,106 m) |

| Population (2005)[1] | |

| • City | 58,213 |

| • Density | 902.4/sq mi (348.5/km2) |

| • Metro | 124,953 |

| Time zone | UTC-7 (MST) |

| Website | http://www.flagstaff.az.us/ |

Flagstaff is a city located in northern Arizona, in the southwestern United States. As of July 2006, the city's estimated population was 58,213, with a Metropolitan Statistical Area population of 124,953.[1] It is the county seat of Coconino County.Template:GR In 2005, Men's Journal named Flagstaff as No. 2 on its Best Places to Live list, and National Geographic cited the city in its list of "10 Great Towns That Will Make You Feel Young."[2] The city is named after a Ponderosa Pine flagpole made by a scouting party from Boston (known as the "Flagstaff Tea Party") to celebrate the United States Centennial on July 4, 1876.

Flagstaff lies near the southwestern edge of the Colorado Plateau and along the western side of the largest contiguous ponderosa pine forest in the continental United States.[3] Flagstaff is located adjacent to Mount Elden, just south of the San Francisco Peaks, the highest mountain range in the state of Arizona. Humphreys Peak, also known as Mount Humphreys, is the highest mountain in Arizona at 12,633 feet (3,850 m) and is located about 10 miles (16 km) north of Flagstaff.

Flagstaff's early economy was based on the lumber, railroad, and ranching industries. Today, the city remains an important road and rail hub, and is home to Lowell Observatory and Northern Arizona University. Flagstaff has a strong tourism sector, due to its proximity to Grand Canyon National Park, Oak Creek Canyon, and historic Route 66.

History

In 1855, Lieutenant Edward Fitzgerald Beale surveyed a road from the Rio Grande in New Mexico to Fort Tejon in California, and camped near the current location of Flagstaff. The lieutenant had his men cut the limbs from a straight pine tree in order to fly the United States flag.[4]

The first permanent settlement was in 1876, when Thomas F. McMillan built a cabin at the base of Mars Hill on the west side of town. During the 1880s, Flagstaff began to grow, opening its first post office and attracting the railroad industry. The early economy was based on timber, sheep, and cattle. By 1886, Flagstaff was the largest city on the railroad line between Albuquerque and the West Coast.[4]

In 1894, Massachusetts astronomer Percival Lowell hired A. E. Douglass to scout an ideal site for a new observatory. Douglass identified Flagstaff as an ideal location for the now famous Lowell Observatory, impressed by its high elevation: "other things being equal, the higher we can get the better".[5] Two years later, the specially-designed 24-inch Clark telescope that Lowell had ordered was installed. in 1930, Pluto was discovered using one of the observatory’s telescopes. During the Apollo program in the 1960s, the Clark Telescope was used to map the moon for the lunar expeditions, enabling the mission planners to choose a safe landing site for the Lunar modules.[6] In homage to the city's importance in the field of astronomy, asteroid 2118 Flagstaff is named for the city, and 6582 Flagsymphony for the Flagstaff Symphony Orchestra.

The Northern Arizona Normal School was established in 1899, renamed Northern Arizona University in 1966.[4] Flagstaff's cultural history recieved a significant boost on April 11 1899, when the "Flagstaff Symphony" made its concert debut at Babbitt's Opera House. The orchestra continues today as the Flagstaff Symphony Orchestra, with its primary venue at the Ardrey Auditorium on the campus of Northern Arizona University.[7]

The city grew rapidly, primarily attributable to its location along the east-west transcontinental railroad line in the United States. In the 1880s[dubious – discuss], the railroads purchased land in the west from the Federal Government, which was then sold to individuals to help finance the railroad projects.[8] By the 1990s[dubious – discuss], Flagstaff found itself located along one of the busiest railroad corridors in the U.S., with 80-100 trains travelling through the city every day, destined for Chicago, Los Angeles, and elsewhere.[9]

Route 66 was completed in 1926, with a route running right through Flagstaff. Flagstaff was incorporated as a city in 1928,[4] and in 1929, the city's first motel, the Motel Du Beau, was built at the intersection of Beaver Street and Phoenix Avenue. The Daily Sun described the motel as "a hotel with garages for the better class of motorists." The units originally rented for $2.50 to $5.00 each, with baths, toilets, double beds, carpets, and furniture.[10] Flagstaff went on to become a popular tourist stop along Route 66, particularly due to its proximity to the Grand Canyon.

Flagstaff grew and prospered through the 1960s. During the 1970s and 1980s, however, many businesses started to spread out from the city center, and the downtown area entered an economic and social decline. Sears and J.C. Penney left the downtown area in 1979 to open up as anchor stores in the new Flagstaff Mall, joined in 1986 by Dillard's. By 1987, even the Babbitt Brothers Trading Company, which had been a retail fixture in Flagstaff since 1891, had closed its doors at Aspen Avenue and San Francisco Street.[11]

In 1987 the city drafted a new Master Plan, also known as the Growth Management Guide 2000, which would transform downtown Flagstaff from a shopping and trade center into a regional center for finance, office uses, and government. The city built a new city hall, library, and the Coconino County Administrative Building in the downtown district, staking an investment by the local government for years to come. In 1992, the city hired a new manager, Dave Wilcox, who had previously worked at revitalizing the downtown areas of Beloit, Wisconsin and Missoula. During the 1990s, the downtown area underwent a revitalization, many of the city sidewalks were repaved with decorative brick facing, and a different mix of shops and restaurants opened up to take advantage of the area's historical appeal.[11]

Geography

Flagstaff is located at 35°11′57″N 111°37′52″W / 35.19917°N 111.63111°W.Template:GR

At 7,000 feet (2,121 m) elevation, located adjacent to the largest contiguous Ponderosa Pine forest in North America, the area around Flagstaff is considered a high altitude semi-desert.[3] However, ecosystems ranging from pinon-juniper studded plateaus, high desert, green alpine forest and barren tundra can all be found within a short drive of Flagstaff.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 63.6 square miles (164.8 km²), of which 63.6 square miles (164.7 km²) is land and 0.04 square miles (0.1 km²) or 0.06 percent is water.

The Flagstaff Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) encompasses all of Coconino County.[12] As of July 1, 2006, the total population of the Flagstaff MSA is 124,953.[13]

Cityscape

Downtown Flagstaff lies immediately to the east of Mars Hill, the location of Lowell Observatory. Streets in the downtown area are laid out in a grid pattern, parallel to Route 66 and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Rail Line, running east-west through the city. Milton Road branches off from Route 66 west of downtown, and travels south, adjacent to the Northern Arizona University campus, to the junction of Interstate 17 and Interstate 40. Milton continues to the south, becoming Arizona State Route 89A, and traveling through Oak Creek Canyon to Sedona. Traveling north from downtown, Fort Valley Road (U.S. 180) connects with the Museum of Northern Arizona, Arizona Snowbowl, and Grand Canyon National Park. Traveling east from downtown, Route 66 and the railroad, parallel to each other, travel to east Flagstaff (and beyond), at the base of Mount Elden. Much of Flagstaff's industry is located east of downtown, adjacent to the railroad tracks, as well as in East Flagstaff.

Several towns are located close to Flagstaff along Interstates 40 and 17. Approximately 35 miles (56 km) to the west is Williams, 20 miles (32 km) to the south is Munds Park, and 30 miles (48 km) to the south is Sedona. 15 miles (24 km) to the east of Flagstaff is the town of Winona, mentioned in the famous song, Route 66. 90 miles (144 km) to the east is Holbrook.

Climate

Flagstaff has a highland semi-arid climate (Koppen climate classification BSk) with four distinct seasons. The combination of high altitude and low humidity provide mild weather conditions throughout most of the year, and the predominantly clear air radiates daytime heating effectively. Temperatures often fall precipitously after sunset throughout the year, and winter nights can be very cold. Winter weather patterns in Flagstaff are cyclonic and frontal in nature, originating in the eastern Pacific Ocean. These deliver periodic, widespread snowfall followed by extended periods of fair weather. This pattern is usually broken by brief, but often intense, afternoon rain showers and dramatic thunderstorms common during the so-called monsoon season of July and August. Summer temperatures are moderate and high temperatures average around 80 °F.[4] The record high temperature is 97.0 °F (36.1 °C) on July 5, 1973, and the record low temperature was -30 °F (-34.4 °C) on February 1, 1985.[14]

The average annual rainfall is 22.91 inches (58.2 cm) and annual snowfall averages 100 inches (254 cm). Overall, the city enjoys an average of 283 days without precipitation each year, and the climate is officially classified as "semi-arid." Although snow often covers the ground for weeks after major winter storms, Flagstaff's relatively low latitude and plentiful winter sunshine quickly melt much of what falls, and persistent deep snowpack is unusual.[4] One notable exception occurred during the severe winter of 1915-1916, when successive Pacific storms buried the city under nearly seven feet (2 m) of snow, and some residents were snowbound in their homes for more than one week.[15]

| Monthly Normal and Record High and Low Temperatures | ||||||||||||

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rec High °F (°C) | 66 (19) | 71 (22) | 73 (23) | 80 (27) | 89 (32) | 96 (36) | 97 (36) | 93 (34) | 91 (33) | 85 (30) | 74 (23) | 68 (20) |

| Norm High °F (°C) | 43 (6) | 46 (8) | 50 (10) | 58 (14) | 68 (20) | 79 (26) | 82 (28) | 80 (27) | 74 (23) | 63 (17) | 51 (11) | 44 (7) |

| Norm Low °F (°C) | 16 (-9) | 19 (-7) | 23 (-5) | 27 (-3) | 34 (1) | 41 (5) | 50 (10) | 49 (9) | 42 (6) | 31 (-1) | 22 (-6) | 17 (-8) |

| Rec Low °F (°C) | -30 (-34) | -23 (-31) | -16 (-27) | -2 (-19) | 7 (-14) | 22 (-6) | 32 (0) | 24 (-4) | 20 (-7) | -2 (-19) | -13 (-25) | -23 (-31) |

| Precip (in) | 2.18 | 2.56 | 2.62 | 1.29 | 0.80 | 0.43 | 2.40 | 2.89 | 2.12 | 1.93 | 1.86 | 1.83 |

| Source: The Weather Channel[16] | ||||||||||||

Demographics

| City of Flagstaff Population by year[17] | |

| 1890 | 963 |

| 1900 | 1,271 |

| 1910 | 1,633 |

| 1920 | 3,186 |

| 1930 | 3,891 |

| 1940 | 5,080 |

| 1950 | 7,663 |

| 1960 | 18,214 |

| 1970 | 26,117 |

| 1980 | 34,743 |

| 1990 | 45,857 |

| 2000 | 52,894 |

| 2005 | 57,391 |

As of the censusTemplate:GR of 2000, there were 52,894 people, 19,306 households, and 11,602 families residing in the city. The July 2006 estimated population of the city was 58,213.[1] The population density was 831.9 people per square mile (321.2/km²). There were 21,396 housing units at an average density of 336.5 per square mile (129.9/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 77.9% White, 1.8% Black or African American, 10.0% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 6.1% from other races, and 2.9% from two or more races. 16.1% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. The city's African American population is considerably lower than the U.S. average (1.8% versus 12.3%), while the Native American population is higher (10.0% vs. 0.9%). This is primarily attributable to the city's proximity to several Indian reservations, including the Navajo, Hopi, Havasupai, and Yavapai.[18]

There were 19,306 households out of which 32.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.0% were married couples living together, 11.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.9% were non-families. 23.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 3.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.59 and the average family size was 3.13.[18]

In the city the population was spread out with 24.3% under the age of 18, 21.7% from 18 to 24, 30.5% from 25 to 44, 18.2% from 45 to 64, and 5.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 27 years. For every 100 females there were 98.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.4 males.[18]

The median income for a household in the city was $37,146, and the median income for a family was $48,427. Males had a median income of $31,973 versus $24,591 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,637. About 10.6% of families and 17.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 17.6% of those under age 18 and 7.0% of those age 65 or over.[18]

As a college town, Flagstaff's population is considerably more educated than the U.S. average. 89.8% of the population has a high school diploma or higher, while the national average is 80.4%. 39.4% of the population has a Bachelor's degree or higher, compared to the national average of 24.4%.[18]

Crime

The violent crime rate, such as murder, robbery and rape, is very low in Flagstaff. However, the property crime rate, including larceny (theft) and burglary, is considerably higher than the average for Arizona cities. In 2002, the FBI's Uniform Crime Report indicated a crime index (incidences of crime per 100,000 population) for Flagstaff of 5,597, with 535 cases of violent crime and 5,062 cases of property crime. Of the 5,062 property crime cases, 4,042 cases were classified as theft.[19] While the property crime rate fell in 2005, it is still high for a town of this size. This is primarily attributable to a significant number of methamphetamine addicts, alcoholics, and the transient nature of many residents. Flagstaff's high number of college students and tourists attract a disproportionally high number of thieves and scam artists.[20]

Economy

In its early days, the city's economic base comprised the lumber, railroad, and ranching industries. Today, that has largely been replaced by tourism, education, government, and transportation. Some of the larger employers in Flagstaff are Northern Arizona University, the Flagstaff Medical Center, and the Flagstaff Unified School District. Tourism is a large contributor to the economy, as the city receives over 5 million visitors per year.[4]

Scientific and high tech research and development operations are located in the city, including the Lowell Observatory and Northern Arizona University. Lowell Observatory continues to be an active astronomical observatory. It has a distributed network of small telescopes which together create images of celestial bodies with much higher resolutions than any other single telescope can produce. Current research is involved in observations of near-Earth phenomena such as asteroids and comets. The observatory is also involved in a $30 million project with the Discovery Channel to build the Discovery Channel Telescope, a sophisticated, ground-based telescope with advanced optical capabilities for future projects.[21]

There are five industrial parks in the city, situated near I-40 and I-17. Major manufacturers in Flagstaff include W.L. Gore & Associates, widely known as the maker of Gore-Tex; Nestlé Purina PetCare, manufacturer of pet food; SCA Tissue, a major tissue paper producer; and Joy Cone, manufacturer of ice cream cones. Walgreens also operates a distribution center in the city.[4]

Air cargo carriers Federal Express and UPS fly direct from Flagstaff Pulliam Airport, and the city has ten motor freight carriers. The one-day travel truck radius extends to Salt Lake City, San Francisco, Albuquerque, El Paso, Los Angeles, and parts of Mexico. Rail cargo transportation is served by the BNSF Railway.[4]

With proximity to Grand Canyon National Park, the city also has a thriving travel and tourism industry, with numerous hotel and restaurant chains. The downtown area is home to two historic hotels, the Weatherford Hotel and the Hotel Monte Vista. The first Ramada Inn opened in 1954 at the intersection of U.S. Route 66, 89 and 89A adjacent to what was then Arizona State College (now Northern Arizona University). The original building is still intact, operating as a Super 8 Motel.[22]

Arts and culture

Despite the town's small size, Flagstaff has an active cultural scene. The city is home to the Flagstaff Symphony Orchestra, which is popular among classical music enthusiasts. Concerts are held from September through April at Ardrey Auditorium on the NAU campus.[7] The city also attracts folk and contemporary acoustic musicians, and offers several annual music festivals during the summer months, such as the Flagstaff Friends of Traditional Music Festival, the Flagstaff Music Festival, and Pickin' in the Pines, a three-day bluegrass and acoustic music festival held at the Pine Mountain Amphitheater at Fort Tuthill Fairgrounds.[23][24][25] Popular bands play throughout the year at the Orpheum Theater, and free concerts are held during the summer months at Heritage Square.[26]

Flagstaff is home to an active theater scene, featuring several groups. Theatrikos, the community theater company, was founded in 1972 in the basement of the Weatherford Hotel, and today puts on five major productions per year. The group recently moved into a new venue in 2002, the Doris-Harper White Community Playhouse, a downtown building which was built in 1923 as an Elks Lodge and later became the Flagstaff library.[27] Since 1995, the Flagstaff Light Opera Company has performed a variety of musical theatre and light opera productions throughout the year at the Sinagua High School auditorium.[28] There are several dance companies in Flagstaff, including the Northern Arizona Preparatory Company and Canyon Movement, which present periodic concerts and collaborate with the Flagstaff Symphony for free concerts during the summer and holiday seasons.[29]

A variety of weekend festivals occur throughout the year. The annual Northern Arizona Book Festival, held in April, brings together nationally known authors to read and display their works.[30] The Flagstaff Mountain Film Festival is held every spring, featuring outdoors, environmental, and other experimental films.[31] The summer months feature several festivals, including Hopi and Navajo Festivals of Arts and Crafts, the Arizona Highland Celtic Festival, and the Made in the Shade Beer Tasting Festival. The Coconino County Fair is held every September at the Fort Tuthill County Fairgrounds, featuring a demolition derby, livestock auction, carnival rides, and other activities.[32]

On New Year's Eve, people gather around the Weatherford Hotel as a 70-pound, 6 foot tall, metallic pine cone is dropped from the roof at midnight. The tradition originated in 1999, when Henry Taylor and Sam Green (owners of the Weatherford Hotel), decorated a garbage can with paint, lights, and pine cones, and dropped it from the roof of their building to mark the new millennium. By 2003 the event had become tradition, and the current metallic pine cone was designed and built by Frank Mayorga of Mayorga Welding in Flagstaff.[33]

The Museum of Northern Arizona includes displays of the biology, archeology, photography, anthropology, and native art of the Colorado Plateau. The Arboretum at Flagstaff is a 200 acre (81 hectare) arboretum featuring 2,500 species of drought-tolerant native plants representative of the high-desert region.[34][35]

Route 66, which originally ran between Chicago and Los Angeles, greatly increased the accessibility to the area, and enhanced the culture and tourism in Flagstaff.[36] Route 66 remains a historic route, passing through the city between Barstow, California, and Albuquerque, New Mexico. In early September, the city hosts an annual event, Route 66 Days, to highlight its connection to the famous highway.[37]

Sports

There are no major league, professional sports in Flagstaff. The Arizona Cardinals of the National Football League have held their summer training camp at Northern Arizona University since the Cardinals moved to Arizona in 1988, with the exception of the 2005 season due to an outbreak of a flu-like virus.[38] The NAU training camp location has been cited as one of the top five training camps in the NFL by Sports Illustrated.[39]

Northern Arizona University and the city of Flagstaff are home to the Center for High Altitude Training, a facility where athletes can train in the unique environment provided by the city's 7,000-feet elevation. The center has been designated by the United States Olympic Committee as an official U.S. Olympic Training Site.[40]

Winter sports, including snowshoeing, Alpine and Nordic skiing, are also popular in the area, and the surrounding National Forests provide an extensive network of roads and trails for winter use. The Arizona Snowbowl ski resort is 15 miles to the north of the city on the San Francisco Peaks. The resort had plans to expand their facilities, adding a fifth chair lift and snow-making capabilities using reclaimed wastewater to extend its ski season in dry years. However, these plans faced opposition by the Navajo and several other Native American tribes, who claimed that it violated their religious freedom, as the San Francisco Peaks are considered sacred in many of their religions. In March, 2007, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the snowmaking scheme violated the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, and the resort's expansion program is currently at a standstill.[41]

Parks and outdoor recreation

Flagstaff has acquired a reputation as a magnet for outdoor enthusiasts, and the region's varied terrain, high elevation, and amenable weather attract campers, backpackers, climbers, and mountain bikers from throughout the southwestern United States. There are 679.2 acres (275 hectares) of city parks in Flagstaff, the largest of which are Thorpe Park and Buffalo Park. Wheeler Park, located adjacent to city hall, is the location of summer concerts and other events.[42] The city maintains an extensive urban trail system, consisting of surface trails for hiking, running, or cycling. The trail network extends throughout the city, connecting the downtown area with the Fort Tuthill Fairgrounds, and extends to Peaks View County Park in Doney Park and Sawmill Multicultural Art and Nature County Park.[43][44]

Trail running and road cycling clubs, organized triathlon events, and annual cross country ski races attest to the area's status as a recreational hub. Several major river running operators are headquartered in Flagstaff, and the city serves as a base for Grand Canyon and Colorado River expeditions.[45]

Flagstaff's proximity to Grand Canyon National Park, about 75 miles (120 km) north of the city, has made it a popular tourist destination since the mid-19th century. Other nearby outdoor attractions include Walnut Canyon National Monument, Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument, Wupatki National Monument, and Barringer Crater. Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and Lake Powell are both about 135 mi (216 km) north along U.S. Route 89.

Media and popular culture

The major daily newspaper in Flagstaff is the Arizona Daily Sun. The Navajo Hopi Observer is a weekly newspaper that is commonly read by the Native American population. A monthly magazine, The Noise, focusing mainly on Flagstaff arts and culture, is distributed throughout most of Northern Arizona.

Flagstaff is included in the Phoenix Designated market area (DMA), the 13th largest in the U.S.,[46] due to the use of several repeaters that provide access to local television and radio stations.[47] There are two local broadcast television stations serving the city; KNAZ-2 (NBC) and KFPH-13 (TeleFutura). The city's major cable television provider is NPG Cablevision.[48]

In the early 20th century, the city was considered as a site for a film by Jesse Lasky and Cecil B. DeMille, but was abandoned in favor of Hollywood.[49] Several recent movies have been filmed, at least in part, in Flagstaff, including Midnight Run, where Charles Grodin gave Robert De Niro the slip. Several of the running scenes in Forrest Gump were filmed in and around the area, including a memorable scene where Forrest is seen jogging in downtown Flagstaff and gives inspiration to a bumper sticker designer. Parts of 2007 Academy Award winner Little Miss Sunshine were filmed at the junction of I-40 and I-17 in Flagstaff, and Terminal Velocity was partially filmed in the city.[50]

During the 1940s and 1950s, over 100 western movies were filmed in nearby Sedona and Oak Creek Canyon. The Hotel Monte Vista in Flagstaff hosted many film stars during this era including Jane Russell, Gary Cooper, Spencer Tracy, John Wayne, and Bing Crosby. A scene from the movie Casablanca was filmed in one of the rooms of the hotel.[51]

The city has been mentioned in several novels, such as The Monkey Wrench Gang by Edward Abbey, depicting an encounter with a Flagstaff policeman. Frank Poole discusses his childhood growing up in Flagstaff in Arthur C. Clarke's novel 3001: The Final Odyssey. Author Richard Bausch wrote a short story called, All the Way in Flagstaff, Arizona. The city also appeared in Stephen King's book, Firestarter.

In 2005, Extreme Makeover: Home Edition built a home just outside of Flagstaff for slain soldier Lori Piestewa's two children and parents. Grizzly Peak Films also filmed Sasquatch Mountain, a feature-length film for the Science Fiction Channel about a Yeti, in Flagstaff and nearby Williams.[2]

The town's name is mentioned in the lyrics to the song, "Route 66" by Bobby Troup.

Government

The city government is organized under a Council-Manager system.[52] The current mayor of Flagstaff is Joseph "Joe" C. Donaldson, who was first elected in 2000, and the current town council consists of the mayor and six councilmembers: Scott Overton (vice mayor), Karen Cooper, Joe Haughey, Kara Kelty, Rick Swanson, and Al White.[53] The city's current interim city manager is John Holmes.[54] Regular meetings of the city council are held on the first and third Tuesday of every month.[55]

Flagstaff is the county seat of Coconino County.

Education

There are 19 public schools, with 11,500 students and 800 faculty and staff, in the Flagstaff Unified School District. In 1997, Mount Elden Middle School was named an A+ School, citing an outstanding school climate, progressive use of technology and zero-tolerance approach to discipline. The 1999 National Science Teacher of the Year, David Thompson, teaches physics at Coconino High School.[56] Three Arizona Teachers of the Year from 2001 through 2003 teach at Flagstaff High School.[57]

In addition to the numerous public schools, there are several charter schools operating in the Flagstaff area including Flagstaff Junior Academy, Northland Preparatory Academy, the Flagstaff Arts and Leadership Academy and the Montessori Schools of Flagstaff.

Flagstaff is home to two institutions of higher education, Northern Arizona University (one of the three public state universities in Arizona), and Coconino Community College.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Flagstaff is at the northern terminus of Interstate 17, which runs 145 miles (232 km) south to Phoenix, Arizona. Interstate 40 runs east-west through the city, traveling to Barstow, California in the west and Albuquerque, New Mexico (and beyond) in the east. Historic Route 66 also runs east-west through the city, roughly parallel to I-40, and is a major thoroughfare for local traffic. Butler Avenue connects I-40 with downtown Flagstaff, and the major north-south thoroughfare through town is Milton Road. Arizona State Route 89A travels through the city (concurrently as parts of Milton Rd. and Route 66), going south through Oak Creek Canyon to Sedona.

Passenger rail service is provided by Amtrak at the downtown station, connecting on east-west routes to Los Angeles and Albuquerque via the Southwest Chief line.[58] Amtrak also provides connecting Thruway Motorcoach service via Open Road Tours, which has an office inside the Flagstaff depot.[59] Local bus service is provided throughout the city by the Mountain Line.

Air travel is available through Flagstaff Pulliam Airport (IATA: FLG, ICAO: KFLG, FAA LID: FLG), located just south of the city. The airport is primarily a small, general aviation airport with a single 6,999 feet (2,133 m) runway. The airport is currently undergoing a major expansion project to add 1,800 feet (549 m) to the north end of the current runway and lengthen the taxiway, to increase its viability for commercial and regional jets.[60] The expansion is expected to be finished by December, 2007. Service to connecting flights at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport (IATA: PHX, ICAO: KPHX, FAA LID: PHX) is provided by US Airways Express operated by Mesa Airlines.[60]

Utilities

Electricity generation in Flagstaff is provided by Arizona Public Service, an electric utility subsidiary operated by parent company Pinnacle West. The primary generating station near Flagstaff is the coal-fired, 995-MW Cholla Power Plant, near Holbrook, Arizona, which uses coal from the McKinley Mine in New Mexico. Located near Page, Arizona is the coal-fired, 750-MW Navajo Power Plant, supplied by an electric railroad that delivers coal from a mine on the Navajo and Hopi reservations in northern Arizona.[61] Flagstaff is also home to Arizona's first commercial solar power generating station, which was built in 1997 and provides 87 kW of electricity. Combined with 16 other solar power locations in Arizona, the system provides over 5 MW of electricity statewide.[62]

Drinking water in Flagstaff is produced from conventional surface water treatment at the Lake Mary Water Treatment Plant, located on Upper Lake Mary, as well as from springs at the inner basin of the San Francisco Peaks. Groundwater from several water wells located throughout the city and surrounding area provide additional sources of drinking water.[63]

Health care

The city's primary hospital is the 270–bed Flagstaff Medical Center, located on the north side of downtown Flagstaff. The hospital was founded in 1936, and serves as the major regional trauma center for northern Arizona.[64]

Sister cities

Flagstaff has four sister cities:[65]

|

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Flagstaff city, Arizona: Population Finder." United States Census Bureau. Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ a b Staff Writer. "Flagstaff economy held steady in 2005." Arizona Republic. December 28, 2005. Retrieved on February 22, 2007.

- ^ a b "Biotic Communities of the Colorado Plateau." Northern Arizona University. Retrieved on March 2, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Flagstaff Community Profile." Official City Website. Retrieved on April 11 2007.

- ^ P. Lowell to A. E. Douglass, April 16 1894, Lowell Observatory Archives.

- ^ Putnam, William Lowell. "The explorers of Mars Hill : a centennial history of Lowell Observatory, 1894-1994." West Kennebunk, Me. : Published for Lowell Observatory by Phoenix Pub., c1994.

- ^ a b "History of the FSO." Flagstaff Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved on April 11 2007.

- ^ Paradis, Thomas Wayne. "Theme Town: A Geography of Landscape and Community in Flagstaff, Arizona." Backinprint.com (February 2003). pp. 65-67.

- ^ Paradis, pp. 96-97.

- ^ Paradis, pp. 244-245.

- ^ a b Paradis, pp. 161-167.

- ^ Jeffries, Betty. "Arizona's New Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas." Arizona Department of Economic Security. August 3, 2004. Retrieved on July 19, 2007.

- ^ "Population Estimates for Metropolitan, Micropolitan, and Combined Statistical Areas Population Estimates for Metropolitan, Micropolitan, and Combined Statistical Areas." United States Census Bureau. Retrieved on July 19, 2007.

- ^ "Flagstaff Weather: Records & Averages." Yahoo!. Retrieved on April 11, 2007.

- ^ "Arizona’s Most Notable Storms." National Weather Service. Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Information from The Weather Channel. Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ Gibson, Campbell. "Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States: 1790 to 1990." United States Census Bureau. June, 1998. Retrieved on October 7, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e "Census 2000 Demographic Profile Highlights." United States Census Bureau. 2000. Retrieved on July 19, 2007.

- ^ "FBI Uniform Crime Report." Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2002. Retrieved on July 26, 2007.

- ^ Staff Writer. "Falling crime rate a good sign." Arizona Daily Sun. July 19 2007. Retrieved on July 26 2007.

- ^ Wotkyns, Steele. "Lowell Observatory and Discovery Communications, Inc., Announce Partnership to Build Innovative Telescope Technology." Lowell Observatory. October 15, 2003. Retrieved on February 22, 2007.

- ^ McDonough, Brian. "Building Type Basics for Hospitality Facilities." 2001. John Wiley and Sons, p. 11. ISBN 0471369446

- ^ "Flagstaff Friends of Traditional Music (website)." Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ "Flagstaff Music Festival (website)." Retrieved on July 18 2007.

- ^ "Pickin' in the Pines - Bluegrass and Acoustic Music Festival (website)." Retrieved on July 18 2007.

- ^ "Thursdays on the Square (website)." Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ "Theatrikos: A Brief History." theatrikos.com. Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ "Flagstaff Light Opera Company (website)." Retrieved on July 18 2007.

- ^ "Canyon Movement Company (website)." Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ Colebank, Susan. "Twenty-something and broke." Arizona Republic. April 8 2003. Retrieved on July 18 2007.

- ^ "Four Spectacular Days of Films (website)." Retrieved on July 18 2007.

- ^ Miller, Cindy. "Summer's worth of festival fun." Arizona Republic. June 18, 2006. Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ Craven, Scott. "Dec. 31: New Year's Eve Block Party and Pinecone Drop." Arizona Republic. December 28, 2006. Retrieved on July 19, 2007.

- ^ "Museum of Northern Arizona (website)." Retrieved on July 14, 2007.

- ^ "The Arboretum at Flagstaff (website)." Retrieved on July 14, 2007.

- ^ "Route 66 in the Flagstaff Area." theroadwnaderer.net. 2003. Retrieved on April 11, 2007.

- ^ "Flagstaff Route 66 Days (website)." Retrieved on July 14, 2007.

- ^ Staff Writer. "Cardinals arriving for training camp." Northern Arizona University. July 26, 2006. Retrieved on November 26 2006.

- ^ King, Peter. "My top five training camps: Places to get up close and personal with NFL players." Sports Illustrated. July 6, 2005. Retrieved on November 26, 2006.

- ^ Staff Writer. "City of Flagstaff helps fund Center for High Altitude Training." Northern Arizona University. November 15, 2006. Retrieved on November 26, 2006.

- ^ "Court says no fake snow at Snowbowl." Casa Grande Dispatch. March 13, 2007. Retrieved on April 12, 2007.

- ^ "City Parks." City of Flagstaff Website. Retrieved on July 14, 2007.

- ^ "Trails." Coconino County Government Website. Retrieved on July 14, 2007.

- ^ "Flagstaff Urban Trails System: Project Status." City of Flagstaff Website. Retrieved on July 14 2007.

- ^ Staff Writer. "What to Do in Flagstaff." flagstaff.com. May 10, 2007. Retrieved on May 10, 2007.

- ^ Holmes, Gary. "Nielsen Reports 1.1% increase in U.S. Television Households for the 2006-2007 Season." Nielsen Media Research. August 23, 2006. Retrieved on April 11, 2007.

- ^ Faber, Daniel M. "Television and FM Translators: A History of Their Use and Regulation." 1993. danielfaber.com. Retrieved on April 11, 2007.

- ^ "NPG Cablevision: Contact Us." Retrieved on April 11 2007.

- ^ Mangum, Richard & Sherry (2003). Flagstaff Past & Present. Northland Publishing. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-87358-847-9.

- ^ Moody, Annemarie. "Arizona in autofocus: Movies put state on road map." Arizona Republic. November 7, 2006. Retrieved on February 27, 2007.

- ^ "Legends of the High Desert: Haunted Monte Vista Hotel in Flagstaff." Legends of America. May 2005. Retrieved on February 27, 2007.

- ^ "Council-Manager Charter for the City of Flagstaff, Arizona." City Government Website. Retrieved on April 11, 2007.

- ^ "Mayor & City Council." City Government Website. Retrieved on April 11, 2007.

- ^ "Administration Directory." City Government Website. Retrieved on April 11 2007.

- ^ "City Council Meetings." City Government Website. Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ "District Information." Flagstaff Unified School District. Retrieved on April 11, 2007.

- ^ "Past Teachers of the Year and Ambassadors." Arizona Education Foundation. Retrieved on April 11, 2007.

- ^ "Flagstaff, AZ (FLG)." Amtrak. Retrieved on April 11, 2007.

- ^ "Flagstaff - Greyhound Station, AZ (FGG)." Amtrak. Retrieved on April 11, 2007.

- ^ a b "Flagstaff Pulliam Airport." City Government Website. Retrieved on April 11, 2007.

- ^ "About APS: Power Plants." Arizona Public Service. Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ "About APS: APS Solar Power Plants." Arizona Public Service. Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ "Drinking Water." City of Flagstaff. Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ "About Flagstaff Medical Center." Northern Arizona Healthcare. Retrieved on February 25, 2007.

- ^ Sister cities designated by Sister Cities International, Inc. (SCI). Retrieved on April 11, 2007.