Conversion therapy

Conversion therapy, sometimes called reparative therapy, involves methods intended to convert gay, lesbian and bisexual people to heterosexuality[1], which have been a source of intense political controversy in the United States and numerous other countries.[2] The American Psychiatric Association states that political and moral debates over the integration of gays and lesbians into the mainstream of American society have obscured scientific data about changing sexual orientation "by calling into question the motives and even the character of individuals on both sides of the issue."[3] The most high-profile contemporary advocates of conversion therapy tend to be fundamentalist Christian groups and other religious organizations.[4] The main organization advocating secular forms of conversion therapy is the National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH).[4][5]

The American Psychological Association defines conversion therapy as therapy aimed at changing sexual orientation.[6] The American Psychiatric Association states that conversion therapy is a type of psychiatric treatment "based upon the assumption that homosexuality per se is a mental disorder or based upon the a priori assumption that a patient should change his/her sexual homosexual orientation."[3] Psychologist Douglas Haldeman writes that conversion therapy comprises efforts by mental health professionals and pastoral care providers to convert lesbians and gay men to heterosexuality, that techniques include psychoanalysis, group therapy, aversive conditioning involving electric shock or nausea-inducing drugs, sex therapy, reparative therapy, and involvement in ex-gay ministries such as Exodus International, and that claims of its effectiveness are unsupported by empirical evidence.[7]

Mainstream American medical and scientific organizations have expressed concern over conversion therapy and consider it potentially harmful.[3][8][9] The advancement of conversion therapy may cause social harm by disseminating inaccurate views about sexual orientation.[8] The ethics guidelines of major mental health organizations in the United States vary from cautionary statements about the safety, effectiveness, and dangers of prejudice associated with conversion therapy (American Psychological Association), to recommendations that ethical practitioners refrain from practicing conversion therapy (American Psychiatric Association) or from referring patients to those who do (American Counseling Association).[3][6][10]

Terminology

The American Psychological Association in 2008 defined conversion therapy and reparative therapy as “therapy aimed at changing sexual orientation.“[6] The American Psychiatric Association considers conversion therapy and reparative therapy to be forms of "psychiatric treatment...based upon the assumption that homosexuality per se is a mental disorder or based upon the a priori assumption that a patient should change his/her sexual homosexual orientation."[3] There is disagreement over which methods the term reparative therapy applies to and whether it should be used. GLAAD states that the term implies that homosexuality is a disorder and should be avoided, a view also held by some psychologists and sociologists.[2][11] Jack Drescher writes in Psychoanalytic Therapy and the Gay Man that properly speaking reparative therapy applies only to the approach developed by Elizabeth Moberly and Joseph Nicolosi.[12] Robert Spitzer in 2003 used reparative therapy to refer to "...any help from a mental health professional or an ex-gay ministry for the purpose of changing sexual orientation".[2]

The Just the Facts Coalition, consisting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of School Administrators, American Counseling Association, American Federation of Teachers, American Psychological Association, American School Counselor Association, American School Health Association, Interfaith Alliance Foundation, National Association of School Psychologists, National Association of Secondary School Principals, National Association of Social Workers, National Education Association, and the School Social Work Association of America, in 2008 released Just the Facts About Sexual Orientation and Youth. This statement defines sexual orientation conversion therapy as “counseling and psychotherapy to attempt to eliminate individuals‘ sexual desire for members of their own sex”, and also defines sexual orientation conversion therapy and reparative therapy as “counselling and psychotherapy aimed at eliminating or suppressing homosexuality”.[8] It distinguishes sexual orientation conversion therapy from ex-gay ministry and transformational ministry, defining the latter as "religious groups that use religion to attempt to eliminate those [same-sex] desires."[8]

The American Psychological Association in 2009 released Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation, which defines sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE) as "methods that aim to change a same-sex sexual orientation (e.g., behavioral techniques, psychoanalytic techniques, medical approaches, religious and spiritual approaches) to heterosexual, regardless of whether mental health professionals or lay individuals (including religious professionals, religious leaders, social groups, and other lay networks, such as self-help groups) are involved."[9]

History

Overview

Legal scholar Kenji Yoshino writes that the history of conversion therapy can be divided into three periods: the Freudian period, in which conversion therapy was not yet systematically established, the “Gilded Age” of conversion therapy, in which such therapy became entrenched, and the post-Stonewall period, in which it was attacked. Yoshino explains that by conversion therapy he means, "the narrower practice of psychoanalytic techniques", which in his view have been more persistent than other forms of conversion treatment.[4]

The Freudian Period

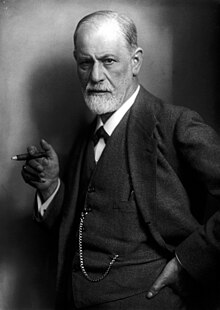

Supporters and opponents of conversion therapy have both tried to find support for their views in the work of Sigmund Freud. This reflects the fact that Freud's views on conversion therapy are disputed. Freud was not optimistic about attempts to change homosexuality, stating in "The Psychogenesis of a Case of Homosexuality in a Woman" that, "In general, to undertake to convert a fully developed homosexual into a heterosexual does not offer much more prospect of success than the reverse, except that for good practical reasons the latter is never attempted." Freud repeated this view in a famous 1935 letter to an American mother who had written to him asking if he could treat her son.[4] Freud replied,

By asking me if I can help [your son], you mean, I suppose, if I can abolish homosexuality and make normal heterosexuality take its place. The answer is, in a general way, we cannot promise to achieve it. In a certain number of cases we succeed in developing the blighted germs of heterosexual tendencies which are present in every homosexual, in the majority of cases it is no more possible. It is a question of the quality and the age of the individual. The result of treatment cannot be predicted.[4]

While Freud did not categorically deny that analysts could convert gay people to heterosexuality, he expressed serious misgivings about their ability to accomplish this. Freud also questioned the ethics of conversion therapy on normative grounds. In his 1935 letter to the American mother, he contended that “ [h]omosexuality is assuredly no advantage but it is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation, it cannot be classified as an illness . . . .” Freud wrote elsewhere that homosexuality should not be treated as a disease, stating that “ ‘[h]omosexual persons are not sick.’”[4]

The first generation of psychoanalysts after Freud generally agreed that psychoanalytic conversion was usually ineffective.[4]

The Gilded Age

After Freud’s death in 1938, a radically different model took shape. Where homosexuality was concerned, psychoanalysis “moved from the humane and cosmopolitan system of investigation it had been with Freud and his circle to a rigid and impervious set of values and judgments.” The new generation of therapists, which included Edmund Bergler, Irving Bieber, Albert Ellis, Abram Kardiner, Sandor Rado, and Charles Socarides, systematically contested each of Freud’s premises about therapeutic conversion. They diverged from Freud’s premise that conversion therapy was generally ineffective. The most systematic study of conversion therapy for male homosexuals was conducted by the New York Society of Medical Psychoanalysts in the 1950s. The study, published in 1962 as Irving Bieber et al's Homosexuality: A Psychoanalytic Study, concluded that “[a]lthough this change may be more easily accomplished by some than by others, in our judgment a heterosexual shift is a possibility for all homosexuals who are strongly motivated to change.” However, that conclusion was not strongly supported by the results Bieber and his colleagues reported, since of the seventy-two exclusive homosexuals in the study, 19% converted to heterosexuality, 19% converted to bisexuality, and 57% remained unchanged. Nonetheless, the Bieber study remains “to this day probably the most often cited on the possibility of sexual reorientation.”[4]

Bieber and many of his colleagues based their optimism about conversion on the belief that homosexuality had psychological causes. The conversion therapists assumed that homosexuality was pathological, and their work inaugurated a period of aggressive conversion of homosexuals. In the period from the 1940s to the 1960s, “many gay men and women voluntarily sought psychoanalytic treatment for their same-sex feelings” and even gay rights organizations made concessions to the views of conversion therapists. The Mattachine Review, which espoused the incrementalist credo of “ evolution not revolution,” accepted contributions from conversion therapists.[4]

Even during this period, however, pro-gay scholars, including Alfred Kinsey, Evelyn Hooker, and Thomas Szasz, raised dissenting voices against the psychiatric orthodoxy. These works did not have immediately transformative effects, but may have laid a foundation for post-Stonewall challenges to conversion therapy.[4]

The Post-Stonewall Period

After the Stonewall riots, activism against conversion therapy began to focus on the DSM designation of homosexuality as a psychopathology. Gay activists agitated for the deletion of homosexuality from the manual. Their efforts, and those of their allies within the psychiatric establishment, led to the deletion of homosexuality from the DSM-II on December 15, 1973. The seventh printing of the DSM-II replaced “Homosexuality per se” with “Sexual Orientation Disturbance”, which included individuals “who are either disturbed by, in conflict with, or wish to change their sexual orientation.” The DSM-III, first published in 1980, replaced “Sexual Orientation Disturbance” with “Ego-dystonic Homosexuality”, which provided support to professionals who sought to continue to practice conversion therapy. The DSM-IV, first published in 1994, removed homosexuality entirely.[4]

Some professionals still engage in conversion therapy. The main mental health organization promoting it is the National Association for Research and Treatment of Homosexuality (NARTH). Founded in 1992, NARTH describes itself as a “Non-Profit Psychoanalytic, Educational Organization Dedicated to Research, Therapy and Prevention of Homosexuality.” The existence of organizations such as NARTH suggested to Kenji Yoshino that there is a larger practice of conversion therapy by individual therapists. Douglas Haldeman suggested in 1991 that conversion therapy might be undergoing a revival. Despite this development, the mental health profession has generally marginalized conversion therapy.[4]

Partly because of this trend, the most high-profile purveyors of conversion therapy tend to be fundamentalist Christian groups and other religious organizations. Such organizations have faced difficulties, with ex-gays sometimes reemerging as ex-ex-gays. The founders of the ex-gay ministry Exodus International ultimately repudiated their own program as “ineffective,” and the founder of the ex-gay ministry Quest was expelled by his organization for sexual misconduct.[4]

Controversy

Conversion therapy has frequently aroused controversy and been a focus of dispute in the media. Reporter Mark Simkin in 2006 called Richard Cohen one of America's leading practitioners of conversion therapy, observing in an exchange on Foreign Correspondent that he "says he’s helped hundreds of clients overcome their homosexuality." During the same exchange gay activist Wayne Besen, described by Simkin as "conversion therapy's fiercest critic", refered to efforts to change homosexuality as "a fraud."[13]

The Washington Times in 2007 reported that the American Psychological Association would convene a task force to evaluate its policies about conversion therapy, writing "Such efforts...are denounced as futile and harmful by many homosexual-rights activists, but conservative and church groups defend the right to offer such treatment, and say people with their viewpoint have been excluded from the review panel." Conservative religious groups and individuals, representing organizations such as the Southern Baptist Convention and Focus on the Family wrote a joint letter to the APA expressing concern that the task force's proposals would not accomodate people whose religious beliefs condemn homosexual behavior. Reparative therapist Joseph Nicolosi stated that he would oppose efforts to ban conversion therapy.[14]

In 2008, the organizers of an APA panel on the relationship between religion and homosexuality canceled the event after gay activists objected that "conversion therapists and their supporters on the religious right use these appearances as a public relations event to try and legitimize what they do."[15][16]

Theories and techniques

Behavioral modification

Douglas Haldeman writes in "Sexual Orientation Conversion Therapy for Gay Men and Lesbians: A Scientific Examination" that early behavioral forms of conversion therapy mainly employed aversive conditioning techniques, involving electric shock and nausea-inducing drugs during presentation of same-sex erotic images. Cessation of the aversive stimuli was typically accompanied by the presentation of opposite-sex erotic images, with the objective of strengthening heterosexual feelings. Haldeman discusses the work of M. P. Feldman, who in "Aversion therapy for sexual deviation: a critical review", published in 1966, claimed a 58% cure rate. Haldeman is skeptical that such stressful methods permit feelings of sexual responsiveness, and notes that Feldman defined success as suppression of homosexuality and increased capacity for heterosexual behavior.[17]

Haldeman also discusses the covert sensitization method, which involves instructing patients to imagine vomiting or receiving electric shocks, writing that only single case studies have been conducted, and that their results cannot be generalized. He writes that behavioral conditioning studies tend to decrease homosexual feelings, but do not increase heterosexual feelings, citing Rangaswami's "Difficulties in arousing and increasing heterosexual responsiveness in a homosexual: A case report", published in 1982, as typical in this respect.[18]

Haldeman concludes that such methods applied to anyone except gay people would be called torture, writing, "Individuals undergoing such treatments do not emerge heterosexually inclined; rather they become shamed, conflicted, and fearful about their homosexual feelings."[19]

Haldeman writes in "Gay Rights, Patient Rights: The Implications of Sexual Orientation Conversion Therapy" that aversive treatments sometimes involved the application of electric shock to the hands and/or genitals, or nausea-inducing drugs, administered simultaneously with the presentation of homoerotic stimuli, while less cruel methods included masturbatory reconditioning, visualization, and social skills training. All of these methods were based on the idea that homosexuality is a learned behavior that can be reconditioned.[20]

Ex-gay ministry

Douglas Haldeman, who regards ex-gay ministries as one type of conversion therapy, writes that they are the main advocates of sexual orientation change outside the scientific community, and that their efforts are of concern to psychology because of their questionable ethics and professionalism. Haldeman writes that those gay men who are most likely to support doctrinaire religion are also likely to suffer from depression and lowered self-esteem, and make vulnerable targets for ex-gay ministries. In his view, most claims for the success of ex-gay ministries are based on the testimonials of such men, even though they are the most suspect kind of evidence.[21]

Haldeman adds that several ex-gay leaders, including the former head of Quest Ministries and Guy Charles of Liberation in Jesus Christ, have been disgraced for having sex with their clients. The founder of Quest Ministries resigned after these facts were brought to light, but later attempted to resume his ministry.[21]

Haldeman criticizes the work of psychologist Dr. E Mansell Pattison and his wife Myrna Loy, who made some of the most notable claims for changing homosexuality through ex-gay methods. Pattison and Loy in 1980 reported that they had changed homosexuality in 11 male subjects through religious methods. Haldeman argues that they mistakenly equated capacity for heterosexual intercourse with complete reversal of sexual orientation and that their study suffered from methodological problems. The 11 subjects were selected from a group of 30 ex-gays treated by EXIT of Melodyland, but the Pattisons did not explain how this group was selected from the larger number of people who sought treatment from EXIT, or why the remaining 19 members of that group refused to be interviewed. The Pattisons gave only vague descriptions of the therapeutic method used, and only 3 of their 11 subjects reported having no homosexual feelings or desires. Haldeman therefore concluded that their data were unconvincing, founded on a poorly described treatment program that used ill-defined constructs.[22]

Group therapy

Douglas Haldeman writes that group therapies intended to change homosexuality have produced contradictory results similar to those of psychoanalytic treatment.[23]

Hadden's "Treatment of male homosexuals in groups", published in 1966, reported a 37% shift to heterosexuality in its 32 subjects. However, in Haldeman's view, its results must be viewed with skepticism because its outcome measures depended upon self-reports, and people involved in group treatment are especially susceptible to influences that might distort their reporting. Mintz's "Overt male homosexuals in combined group and individual treatment", was published in 1966, and which had had ten subjects, reported that homosexual patients were able to increase contact with heterosexuals, a claim Haldeman describes as "impressionistic." Birk's "The myth of classical homosexuality: Views of a behavioral psychotherapist, which was published in Judd Marmor's 1980 book Homosexual behavior: A modern reappraisal, describes a combination of insight-oriented and social learning methods of treating homosexuality, claiming that 38% of his patients achieved solid heterosexual shifts. Haldeman writes that Birk's treatment objectives are unclear, and concludes that the problems with group therapy indicate that conversion therapy does not change sexual orientation but only instructs or coerces heterosexual behavior in a minority of subjects.[23]

Psychoanalysis

Douglas Haldeman writes that psychoanalytic treatment of homosexuality is exemplified by the work of Irving Bieber and his colleagues in Homosexuality: A Psychoanalytic Study of Male Homosexuals. They advocated long-term therapy aimed at resolving the unconscious childhood conflicts that they considered responsible for homosexuality. Haldeman notes that Bieber's methodology has been criticized because it relied upon a clinical sample, the description of the outcomes was based upon subjective therapist impression, and follow-up date were poorly presented. Bieber reported a 27% success rate from long-term therapy, but only 18% of the patients in whom Bieber considered the treatment successful had been exclusively homosexual to begin with, while 50% had been bisexual. In Haldeman's view, this makes even Bieber's unimpressive claims of success misleading.[24]

Haldeman discusses other psychoanalytic studies of attempts to change homosexuality. Curran and Parr's "Homosexuality: An analysis of 100 male cases", published in 1957, reported no significant increase in heterosexual behavior. Mayerson and Lief's "Psychotherapy of homosexuals: A follow-up study of nineteen cases", published in 1965, reported that half of its 19 subjects were exclusively heterosexual in behavior four and a half years after treatment, but its outcomes were based on patient self-report and had no external validation. In Haldeman's view, those participants in the study who reported change were bisexual at the outset, and its authors wrongly interpreted capacity for heterosexual sex as change of sexual orientation.[25]

Reparative therapy

Reparative therapy has been used as a synonym for conversion therapy generally, but Jack Drescher has argued that strictly speaking it refers to a specific kind of therapy associated with Elizabeth Moberly and Joseph Nicolosi.[12] Joseph Nicolosi's Reparative Therapy of Male Homosexuality, published in 1991, introduced reparative therapy as a term for psychotherapeutic attempts to convert gay people to heterosexuality.[11]

Douglas C. Haldeman writes that Nicolosi promotes psychoanalytic theories suggesting that homosexuality is a form of arrested psychosexual development, resulting from "an incomplete bond and resultant identification with the same-sex parent, which is then symbolically repaired in psychotherapy".[20] Nicolosi’s intervention plans involve conditioning a man to a traditional masculine gender role. He should "(1) participate in sports activities, (2) avoid activities considered of interest to homosexuals, such [as] art museums, opera, symphonies, (3) avoid women unless it is for romantic contact, (4) increase time spent with heterosexual men in order to learn to mimic heterosexual male ways of walking, talking, and interacting with other heterosexual men, (5) Attend church and join a men’s church group, (6) attend reparative therapy group to discuss progress, or slips back into homosexuality, (7) become more assertive with women through flirting and dating, (8) begin heterosexual dating, (9) engage in heterosexual intercourse, (10) enter into heterosexual marriage, and (11) father children".[26]

Most mental health professionals consider reparative therapy discredited, but it is still practiced by some professionals.[4] Psychoanalysts critical of Nicolosi's theories have offered gay-affirmative approaches as an alternative to reparative therapy.[12][27] Exodus International regards reparative therapy as a useful tool to eliminate "unwanted same-sex attraction."[28]

Sex therapy

Douglas Haldeman has described William Masters' and Virginia Johnson's work on sexual orientation change as a form of conversion therapy.[29]

In Homosexuality in Perspective, published in 1979, Masters and Johnson viewed homosexuality as the result of blocks that prevented the learning that facilitated heterosexual responsiveness, and described a study of 54 gay men who were dissatisfied with their sexual orientation. The original study did not describe the treatment methodology used, but this was published five years later. John C. Gonsiorek criticized their study on several grounds in 1981, pointing out that while Masters and Johnson stated that their patients were screened for major psychopathology or severe neurosis, they did not explain how this screening was performed, or how the motivation of the patients to change was assessed. 19 of their subjects were described as uncooperative during therapy and refused to participate in a follow-up assessment, but all of them were assumed without justification to have successfully changed.[30]

Douglas Haldeman writes that Masters and Johnson's study was founded upon heterosexist bias, and that it would be tremendously difficult to replicate. In his view, the distinction Masters and Johnson made between "conversion" (helping gay men with no previous heterosexual experience to learn heterosexual sex) and "reversion" (directing men with some previous heterosexual experience back to heterosexuality) was not well founded. Many of the subjects Masters and Johnson labelled homosexual may not have been homosexual, since, of their participants, only 17% identified themselves as exclusively homosexual, while 83% were in the predominantly heterosexual to bisexual range. Haldeman observed that since 30% of the sample was lost to the follow up, it is possible that the outcome sample did not include any people attracted mainly or exclusively to the same sex. Haldeman concludes that it is likely that, rather than converting or reverting gay people to heterosexuality, Masters and Johnson only strengthened hetersexual responsiveness in people who were already bisexual.[30]

Studies of conversion therapy

"Among those studies reporting on the perceptions of harm, the reported negative social and emotional consequences include self-reports of anger, anxiety, confusion, depression, grief, guilt, hopelessness, deteriorated relationships with family, loss of social support, loss of faith, poor self-image, social isolation, intimacy difficulties, intrusive imagery, suicidal ideation, self-hatred, and sexual dysfunction. These reports of perceptions of harm are countered by accounts of perceptions of relief, happiness, improved relationships with God, and perceived improvement in mental health status, among other reported benefits"."[31]

Can Some Gay Men and Lesbians Change Their Sexual Orientation?

In May 2001, Dr. Robert Spitzer presented "Can Some Gay Men and Lesbians Change Their Sexual Orientation? 200 Participants Reporting a Change from Homosexual to Heterosexual Orientation", a study of attempts to change homosexual orientation through ex-gay ministries and conversion therapy, at the American Psychiatric Association's convention in New Orleans. The study was partly a response to the APA's 2000 statement cautioning against clinical attempts at changing homosexuality, and was aimed at determining whether such attempts were ever successful rather than how likely it was that change would occur for any given individual. Spitzer wrote that some earlier studies provided evidence for the effectiveness of therapy in changing sexual orientation, but that all of them suffered from methodological problems.[2]

He reported that after intervention, 66% of the men and 44% of the women had achieved "Good Heterosexual Functioning", which he defined as requiring five criteria (being in a loving heterosexual relationship during the last year, overall satisfacition in emotional relationship with a partner, having heterosexual sex with the partner at least a few times a month, achieving physical satisfaction through heterosexual sex, and not thinking about having homosexual sex more than 15% of the time while having heterosexual sex). He found that the most common reasons for seeking change were lack of emotional satisfaction from gay life, conflict between same-sex feelings and behavior and religious beliefs, and desire to marry or remain married.[2][32] This paper was widely reported in the international media and taken up by politicians in the United States, Germany, and Finland, and by conversion therapists.[2]

In 2003, Spitzer published the paper in the Archives of Sexual Behavior. Spitzer's study has been criticized on numerous ethical and methodological grounds. Gay activists argued that the study would be used by conservatives to undermine gay rights. Researchers observed that the study sample consisted of people who sought treatment primarily because of their religious beliefs, and who may therefore have been motivated to claim that they had changed even if they had not, or to overstate the extent to which they might have changed. That participants had to rely upon their memories of what their feelings were before treatment may have distorted the findings. It was impossible to determine whether any change that occurred was due to the treatment because it was not clear what it involved and there was no control group. Claims of change may have reflected a change in self-labelling rather than of underlying orientation or attractions, and particpants may have been bisexual before treatment. Follow-up studies were not conducted.[2] Spitzer stressed the limitations of his study. Spitzer said that the number of gay people who could successfully become heterosexual was likely to be "pretty low", and conceded that his subjects were "unusually religious."[33]

Changing Sexual Orientation

Ariel Shidlo and Michael Schroeder found in "Changing Sexual Orientation: A Consumer's Report", a peer-reviewed study published in 2002, that 88% of participants failed to achieve a sustained change in their sexual behavior and 3% reported changing their orientation to heterosexual. The remainder reported either losing all sexual drive or attempting to remain celibate, with no change in attraction. Some of the participants who failed felt a sense of shame and had gone through conversion therapy programs for many years. Others who failed believed that therapy was worthwhile and valuable. Shidlo and Schroeder also reported that many respondents were harmed by the attempt to change. Of the 8 respondents (out of a sample of 202) who reported a change in sexual orientation, 7 worked as ex-gay counselors or group leaders.[34]

Ethical Issues in Attempts to Ban Reorientation Therapies

Mark Yarhouse and Warren Throckmorton, of the private Christian school Grove City College, in 2002 published "Ethical Issues in Attempts to Ban Reorientation Therapies", which argues that conversion therapy should be available out of respect for a patient’s values system and because there is evidence that it can be effective. They state that studies from the 1950s–1980s generally reported rates of positive outcomes at about 30%, with more recent survey research generally consistent with the extant data. Their paper was partly a response to Jack Drescher's 2001 paper, "Ethical issues surrounding attempts to change sexual orientation", which used the principle of "Do no harm" to argue against conversion therapy.[35]

Medical, scientific and legal views

American medical consensus

The medical and scientific consensus in the United States is that conversion therapy is potentially harmful, but that there is no scientifically adequate research demonstrating either its effectiveness or harmfulness.[6][8][36] Anecdotal claims of cures and harm counterbalance each other.[37] Mainstream medical bodies state that conversion therapy can be harmful because it may exploit guilt and anxiety, thereby damaging self-esteem and leading to depression and even suicide.[38] There is also concern in the mental health community that the advancement of conversion therapy can cause social harm by disseminating inaccurate views about sexual orientation and the ability of gay and bisexual people to lead happy, healthy lives.[8]

Mainstream health organizations critical of conversion therapy include the American Medical Association,[39] American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, the American Counseling Association, the National Association of Social Workers, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Association of School Administrators, the American Federation of Teachers, the National Association of School Psychologists, the American Academy of Physician Assistants, and the National Education Association.[8][40][41]

Mainstream medical organizations do not accept the anecdotal evidence offered by conversion therapists for several reasons. These include the fact that the results are not published in peer-reviewed journals, but tend to be released to the mass media and the Internet, that random samples of subjects are not used and results are reliant upon the subjects' own self-reported outcomes or on evaluations by therapists which may be subject to social desirability bias, that the evidence is gathered over short periods of time and there is little follow-up data to determine whether the therapy was effective over the long-term, that the evidence does not demonstrate a change in sexual orientation but merely a reduction in same-sex behavior, that the possibility that subjects may be bisexual and have simply been convinced to restrict their sexual activity to the opposite sex was not considered, there is often no control group to rule out the possibility that other things, such as being motivated to change, were the true cause of any change the researchers observed in the study participants,[42] that conversion therapists falsely assume that homosexuality is a mental disorder, and that their research focuses almost exclusively on gay men and rarely includes lesbians.[43][8][26][33][44]

Ethics guidelines

In 1998, the American Psychiatric Association issued a statement opposing any treatment which is based upon the assumption that homosexuality is a mental disorder or that a person should change their orientation, but did not have a formal position on other treatments that attempt to change a person's sexual orientation. In 2000, they augmented that statement by saying that as a general principle, a therapist should not determine the goal of treatment, but recommends that ethical practitioners refrain from attempts to change clients' sexual orientation until more research is available.[3]

The American Counseling Association has stated that they do not offer or condone any training to educate and prepare a counselor to practice conversion therapy. They strongly suggest counselors do not refer clients to a conversion therapist or to proceed cautiously once they know the counselor fully informs clients of the unproven nature of the treatment and the potential risks and takes steps to minimize harm to clients. However, "it is of primary importance to respect a client's autonomy to request a referral for a service not offered by a counselor." A counselor performing conversion therapy "must define the techniques/procedures as 'unproven' or 'developing' and explain the potential risks and ethical considerations of using such techniques/procedures and take steps to protect clients from possible harm." The counselor must also provide complete information about the treatment, offer referrals to gay-affirmative counselors, discuss the right of clients, understand the client's request within a cultural context, and only practice within their level of expertise.[10]

The American Psychological Association "is concerned about [conversion] therapies and their potential harm to patients ... Any person who enters into therapy to deal with issues of sexual orientation has a right to expect that such therapy would take place in a professionally neutral environment absent of any social bias."[45] The APA stated, with regard to conversion therapy,

... that psychologists do not knowingly participate in or condone unfair discriminatory practices ... do not engage in unfair discrimination based on sexual orientation ... respect the rights of individuals to privacy, confidentiality, self-determination and autonomy ... , try to eliminate the effect on their work of biases based on cultural, individual and role differences due to sexual orientation .. where differences of sexual orientation significantly affect psychologist's work concerning particular individuals or groups, psychologists obtain the training, experience, consultation, or supervision necessary to ensure the competence of their services, or they make appropriate referrals ... do not make false or deceptive statements concerning the scientific or clinical basis for their services ... obtain appropriate informed consent to therapy or related procedures which generally implies that the client or patient (1) has the capacity to consent, (2) has been informed of significant information concerning the procedure, (3) has freely and without undue influence expressed consent, and (4) consent has been appropriately documented ... [and that] the American Psychological Association urges all mental health professionals to take the lead in removing the stigma of mental illness that has long been associated with homosexual orientation." (internal quotes, brackets, and ellipses omitted).[46]

International medical views

The development of theoretical models of sexual orientation in countries outside the United States that have established mental health professions often follows the history within the U.S. (although often at a slower pace), shifting from pathological to non-pathological conceptions of homosexuality.[47] The World Health Organization's ICD-10, which along with the DSM-IV is widely used internationally, states that "sexual orientation by itself is not to be regarded as a disorder". It lists ego-dystonic sexual orientation as a disorder instead, which it defines as occurring where "the gender identity or sexual preference (heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, or prepubertal) is not in doubt, but the individual wishes it were different because of associated psychological and behavioural disorders, and may seek treatment in order to change it."[48]

Legal issues

In 2005, Love in Action, an ex-gay ministry based in Memphis, was investigated by the Tennessee Department of Health and the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities for providing counselling and mental health care without a licence, and for treating adolescents without their consent. There have been reports that teenagers have been forcibly treated with conversion therapy on other occasions.[49][50][51] In 2006, a report by the National Gay and Lesbian Taskforce outlined evidence that conversion therapy groups are increasingly focusing on children.[5] Several legal researchers have responded to these events by arguing that parents who force their children into aggressive conversion therapy programs are committing child abuse under various state statutes.[52][53]

There have been few, if any, medical malpractice lawsuits filed on the basis of conversion therapy. Laura A. Gans suggested in an article published in The Boston University Public Interest Law Journal that this is because there is an "historic reluctance of consumers of mental health services to sue their care givers" and because of "the difficulty associated with establishing the elements of... causation and harm... given the intangible nature of psychological matters." Gans also suggested that a tort cause of action for intentional infliction of emotional distress might be sustainable against therapists who use conversion therapy on patients who specifically say that his or her anxiety does not arise from his or her sexuality.

In one of the few published U.S. cases dealing with conversion therapy, the Ninth Circuit addressed the topic in the context of an asylum application. A Russian citizen "had been apprehended by the Russian militia, registered at a clinic as a 'suspected lesbian,' and forced to undergo treatment for lesbianism, such as 'sedative drugs' and hypnosis.... The Ninth Circuit held that the conversion treatments to which Pitcherskaia had been subjected constituted mental and physical torture. The court rejected the argument that the treatments to which Pitcherskaia had been subjected did not constitute persecution because they had been intended to help her, not harm her.... The court stated that 'human rights laws cannot be sidestepped by simply couching actions that torture mentally or physically in benevolent terms such as "curing" or "treating" the victims.'" "[54]

Notes

- ^ Statement of the American Psychological Association

- ^ a b c d e f g Drescher 2006, pp. 126, 175

- ^ a b c d e f Position Statement on Therapies Focused on Attempts to Change Sexual Orientation (Reparative or Conversion Therapies) (PDF), American Psychiatric Association, 2000, retrieved 2007-08-28

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Yoshino 2002

- ^ a b Cianciotto, Jason; Cahill, Sean (2006), Youth in the crosshairs: the third wave of ex-gay activism (PDF), National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, retrieved 2007-08-29

- ^ a b c d Answers to Your Questions: For a Better Understanding of Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality (PDF), American Psychological Association, 2008, retrieved 2008-02-14

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gonsiorek 1991, pp. 149–160

- ^ a b c d e f g h Just the Facts About Sexual Orientation & Youth: A Primer for Principals, Educators and School Personnel, Just the Facts Coalition, 1999, retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ a b Glassgold, JM (2009-08-01), Report of the American Psychological Association Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation (pdf), American Psychological Association, retrieved 2009-09-24

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Whitman, Joy S.; Glosoff, Harriet L.; Kocet, Michael M.; Tarvydas, Vilia (2006-05-22), Ethical issues related to conversion or reparative therapy, American Counseling Association, retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ a b GLAAD, GLAAD Media Reference Guide (PDF), retrieved September 2006

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c Drescher 1998, p. 152 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFDrescher1998 (help)

- ^ Transcript of "USA - Gay Conversion, ABC TV Foreign Correspondent, 08-22-2006. Retrieved 04-07-2007.

- ^ Gay reparative therapy under scrutiny, New York: Washington Times, July 11, 2007, retrieved 2009-02-15

- ^ Plowman 2008

- ^ Johnson 2008

- ^ Gonsiorek 1991, p. 152

- ^ Gonsiorek 1991, p. 152-153

- ^ Gonsiorek 1991, p. 153

- ^ a b Haldeman 2002, pp. 260–264

- ^ a b Gonsiorek 1991, p. 156-158

- ^ Gonsiorek 1991, p. 158-159

- ^ a b Gonsiorek 1991, p. 151

- ^ Gonsiorek 1991, p. 150-151

- ^ Gonsiorek 1991, p. 151, 256

- ^ a b Bright 2004, pp. 471–481

- ^ Domenici 1995, p. 119

- ^ Exodus International Policy Statements, Exodus International, retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ Gonsiorek 1991, p. 149, 154

- ^ a b Gonsiorek 1991, p. 154

- ^ American Psychological Association: Resolution on Appropriate Affirmative Responses to Sexual Orientation Distress and Change Efforts

- ^ Spitzer 2004, pp. 403–417

- ^ a b Attempts To Change Sexual Orientation, University of California, Davis Department of Psychology, retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ Shidlo & Schroeder 2002, pp. 249–259

- ^ Yarhouse & Throckmorton 2002, pp. 66–75

- ^ H., K (1999-01-15), APA Maintains Reparative Therapy Not Effective, Psychiatric News (news division of the American Psychiatric Association), retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ Therapies Focused on Attempts to Change Sexual Orientation

- ^ Luo, Michael (2007-02-12), Some Tormented by Homosexuality Look to a Controversial Therapy, The New York Times, p. 1, retrieved 2007-08-28

{{citation}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ American Medical Association policy regarding sexual orientation, American Medical Association, 2007-07-11, retrieved 2007-07-30

- ^ "Homosexuality and Adolesence" (PDF), Pediatrics, Official Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics, 92: 631–634, 1993, retrieved 2007-08-28

{{citation}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ Physician Assistants vote on retail clinics, reparative therapy, SpiritIndia.com, retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation Page 2

- ^ Haldeman 2002

- ^ Haldeman, Douglas (1999), "The Pseudo-science of Sexual Orientation Conversion Therapy" (PDF), The Policy Journal of the Institute for Gay and Lesbian Strategic Studies, 4 (1): 1–4, retrieved 2007-08-28

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality, American Psychological Association, retrieved 2009-05-27

- ^ Resolution on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation, American Psychological Association, 1997-08-14, retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ "Special Issue on the Mental Health Professions and Homosexuality", Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, 7 (1/2), Haworth Medical Press, 2003

- ^ ICD-10, Chapter V: Mental and behavioural disorders: Disorders of adult personality and behaviour, World Health Organization, 2007, retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ David Williams, About Ex-Gay Ministries, retrieved 2008-09-14

- ^ Melzer, Eartha (2005-07-01), Tenn. opens new probe of ‘ex-gay’ facility: Experts say children should not be forced into counseling, Washington Blade, retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ Popper, Ben (2006-02-10), Love in Court: Gay-to-straight ministry and the state go to court, Memphis Flyer, retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ Talbot, T. (2006), "Reparative therapy for homosexual teens: the choice of the teen should be the only choice discussed", Journal of Juvenile Law

- ^ Cohan, J. (2002), "Parental Duties and the Right of Homosexual Minors to Refuse "Reparative" Therapy", Women's Law Journal (67)

- ^ Gans, Laura A. (1999), "Inverts, Perverts, and Converts: Sexual Orientation Conversion Therapy and Liability", The Boston University Public Interest Law Journal, 8

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Bibliography

- Bright, Chuck (2004), "Deconstructing Reparative Therapy: An Examination of the Processes Involved When Attempting to Change Sexual Orientation", Clinical Social Work Journal, 32 (4), doi:10.1007/s10615-004-0543-2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Cohen, Richard (2000), Coming Out Straight: Understanding and Healing Homosexuality, Winchester: Oakhill Press, ISBN 1-886939-47-0

- Domenici, Thomas; Lesser, Ronnie C. (1995), Disorienting Sexuality: Psychoanalytic Reappraisals of Sexual Identities, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0415911982

- Drescher, Jack (1998), "I'm Your Handyman: A History of Reparative Therapies", Journal of Homosexuality, 36 (1), doi:10.1300/J082v36n01_02

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Drescher, Jack; Zucker, Kenneth (2006), Ex-Gay Research: Analyzing the Spitzer Study and Its Relation to Science, Religion, Politics, and Culture, New York: Harrington Park Press, ISBN 1-56023-557-8

- Drescher, Jack (1998), Psychoanalytic Therapy and the Gay Man, Hillsdale, New Jersey: The Analytic Press, ISBN 0881632082

- Duberman, Martin (1992), Cures: A Gay Man's Odyssey, New York: Plume, ISBN 0452267803

- Gonsiorek, John; Weinrich, James (1991), Homosexuality:Research Implications for Public Policy, Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications, Inc, ISBN 0-8039-3764-4

- Haldeman, Douglas C. (2002), "Gay Rights, Patient Rights: The Implications of Sexual Orientation Conversion Therapy", Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 33 (3), doi:10.1037//0735-7028.33.3.260

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Johnson, Chris (2008-05-12), Robinson backs out of symposium on "ex-gays", Washington Blade

- Nicolosi, Joseph (1991), Reparative Therapy of Male Homosexuality: A New Clinical Approach, Northvale, New Jersey: Jason Aronson, ISBN 0876685459

- Plowman, William (2008-05-12), Homosexuality Panel Squelched by Gay Activists, NPR

- Shidlo, Ariel; Schroeder, Michael (2002), "Changing Sexual Orientation: A Consumers' Report", Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 33 (3), doi:10.1037//0735-7028.33.3.249

- Spitzer, Robert L. (2003), "Can Some Gay Men and Lesbians Change Their Sexual Orientation? 200 Participants Reporting a Change from Homosexual to Heterosexual Orientation", Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32 (5), doi:10.1023/A:1025647527010, PMID 14567650

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Yarhouse, Mark A.; Throckmorton, Warren (2002), "Ethical Issues in Attempts to Ban Reorientation Therapies" (PDF), Psychotherapy: Theory/Research/Practice/Training, 39 (1), doi:10.1037//0033-3204.39.1.66, retrieved 2007-08-28

- Yoshino, Kenji (2002), "Covering", Yale Law Journal, 111 (4)

External links

- American Counseling Association ("Research does not support conversion therapy as an effective treatment modality.... There is potential for harm when clients participate in conversion therapy.")

- American Psychiatric Association ("In the last four decades, 'reparative' therapists have not produced any rigorous scientific research to substantiate their claims of cure. Until there is such research available, APA recommends that ethical practitioners refrain from attempts to change individuals' sexual orientation, keeping in mind the medical dictum to first, do no harm.")

- American Psychological Association ("Mental health professional organizations call on their members to respect a person’s (client’s) right to self determination")

- World Health Organization (Those with an egodystonic sexual orientation "may seek treatment in order to change it".)