Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

July 7

I'm looking for how this magic trick works. A magician takes a dollar bill from the audience and makes it appear inside a fruit (orange/lemon). This youtube video demonstrates how it works: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cQBrXCcfDyc But I've seen many magicians ask the audience to sign the bill and making it appear in the orange rather than just having a different bill appear inside. Do you know any information on how this one works? I can't seem to find the information anywhere. 69.230.55.21 (talk) 00:19, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- At a guess they probably switch the dollar bill they put in the fruit with the one the audience gave to them at some stage after opening it Nil Einne (talk) 01:04, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

Of course, it is Sleight of hand or हाथ की सफाई as they call it in India. It is an ancient art. Nowadays tricksters tell you that is nothing but art, in India now that is even required by law, though that is not strictly required by law but Rationalist Society people get you otherwise Jon Ascton (talk) 01:13, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Or the "random person from the audience" is in cahoots with the performer. 218.25.32.210 (talk) 01:19, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- ok thanks for the info, but can you give me specific steps in performing this trick? I know that this can be performed with a "random person" not a confederate of the magician. 69.230.55.21 (talk) 01:21, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, there are always more than one way to do a trick. And a clever magician never repeats a trick before the same audience Jon Ascton (talk) 02:24, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Hey! I just saw the video (after writting my above comments). The magician simply, honestly gives away the trick - that's amazingly easy ! Did'nt ya get it, man ? What happened is this : Before you do the trick you take a dollar, note its serial number on a paper. Then you roll up the note and stick it neatly in an orange, do it in such a way that it does'nt look as if someone's done something to the fruit. Now you are ready for the trick. You ask a guy to come up and give you a dollar, he will give his own dollar of course with it's different serial, but that does'nt bother you because you don't really write it anywhere, but only pretend you do so ! by moving a pen on the paper on which you have already written the number of the dollar which is readily stuffed in the orange. Now you roll the guy's dollar and put the handkerchief on it, this is where you slip the dollar in your other hand or somewhere else he can't see it. He thinks it is there in the handkerchief, but it is some piece of paper rolled in the handkerchief's hem ! Now you unfurl the handkerchief and the dollar "vanishes" (it is already soemwhere else, what the dumb bastard was feeling was the paper in the hem !) Now put the handkerchief out of picture and cut open the orange which has your original dollar whose serial number is safely recoreded on the paper ! Got it ? Cool ! Jon Ascton (talk) 03:08, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- I used to dabble a lot with magic tricks when my kid was younger. My favorite fruit trick is to hand several members of the audience a banana pulled from an entire bunch I have brought with me. I ask them to inspect their bananas carefully - then without me being anywhere nearby, to peel them. They are all amazed to find that the inside of their banana is neatly sliced into a half dozen pieces - and even after that, they can look at the skin, eat the banana and not see how the trick was done. It's nice because there are so many bananas that I couldn't possibly have that many confederates - and everyone in even a moderately large audience is sitting close enough to one of the bananas to see the trick happen in front of their eyes.

- I'll let you figure out how I do that one! SteveBaker (talk) 04:31, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Hm...I think it's got to do with the art of slicing the inside without damaging the skin ! No ? That can be accomplished either with a sharp needle or a needle and a thread. Right ? Jon Ascton (talk) 04:58, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yep you use a needle and thread. Pick bananas that are sufficiently ripe to have a few brown speckles and use the needle to pull the thread from one brown spot to another around the banana going back in through the exact same pinhole you came out of. When you've gone all around the banana, come back out of the same hole you started at and then just pull on the thread to slice through the flesh, leaving the skin intact - except for the smallest of pinholes. Then, soaking the entire bunch of bananas in water makes the skin expand slightly, closing the pinholes to the point where they are pretty much invisible. If possible, place your pinholes along the 'seams' of the banana skin so that tearing the banana open helps to destroy the evidence even further. It takes a half hour to prepare an entire bunch of bananas - I like to leave them on the kitchen countertop at work on April 1st. SteveBaker (talk) 03:11, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Hm...I think it's got to do with the art of slicing the inside without damaging the skin ! No ? That can be accomplished either with a sharp needle or a needle and a thread. Right ? Jon Ascton (talk) 04:58, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- I think you're somewhat missing the point. The OP is aware the video shows how it works for that case. What they want is to know how it works when the illusionist shows a bill that was signed by a member of the audience, so you can't just use a different bill. As you and I have said, it would likely be some sort of sleight of hand, swapping the bill inside the fruit for the signed one (alternativing signing the one inside, but this seems far less likely given that the signature could easily be recognised as a fake) but the OP wants more. Nil Einne (talk) 05:18, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Oops, Nil, you are right, I missed that point ! How stupid of me ! Terribly sorry indeed ! Oh, the OP knows how he did that, my ! I was taking so much pains to tell what he already knew, perhaps better than me ! Sorry, OP man. I overlooked that part - the magician does not explain the whole trick - but leaves a vital loophole - the signature thing. Oh my ! So this is a new way to show magic. You do an easy trick. Explain it is such a way that an asshole like me thinks that all is explained, but when he thinks over he learns there is something he can not get through. Well, there should be a special term for this kind of thing, no ? Yup, Nil man, its good old slieght of hand of course... Jon Ascton (talk) 07:15, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- ...and what do ya think about the SteveBaker's banana ? Like my solution, eh ?

- For some reason this trick doesn't show up in my trusty copy of "Cyclopedia of Magic" which is usually my go-to source for when I'm curious about such things.

- One way to do it, would be to swap the bills when they're still rolled up. (ie: Cut open the orange, show that it contains a rolled up bill, then use sleight of hand to swap them while you were in the process of unrolling them.) This would probably require the magician to be the one to remove the bill from the orange, which wouldn't have the same effect as letting the spectator do it. APL (talk) 15:21, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

side mirror

what type of glue/ resin do they use to attach a side mirror on a car? i mean attach the actual glass part to the metal part (honda) —Preceding unsigned comment added by Alexsmith44 (talk • contribs) 00:27, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Are you sure it's glued on? I would have assumed it was bolted on. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 00:35, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

i think its glued on. mine broke today and there were no bolts —Preceding unsigned comment added by Alexsmith44 (talk • contribs) 00:37, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Glued onto what? The pivot mechanism? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 00:40, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

only the glass part broke not the metal part —Preceding unsigned comment added by Alexsmith44 (talk • contribs) 00:50, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- I don't follow. The glass part has to be attached to a pivot mechanism of some kind so it can be adjusted. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 00:53, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- No need to interrogate the guy. His question is clear enough. The glass shattered and has to be re-glued to the piece that the mirror itself attaches to. If you don't understand the mechanism, you don't have to answer.

- There was a discussion on this very topic here.

- Check out Steve's post at the end. If he's right, It looks like what you want is some rubbery adhesive pads specially designed for this purpose. (These two allegedly educational YouTube videos back him up on this : [1][2]) APL (talk) 02:00, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- No need to get snippy. I was asking these questions out of curiosity. Believe it or not, I'm not an expert on everything. :) However, if it were me, I would take it to the dealership and let them figure it out and explain it to me. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 11:06, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

do they use a formaldehyde resin in the factory to attach it?--Alexsmith44 (talk) 02:08, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- I don't know - but in the previous discussion on this topic, the person said that when they bought the replacement mirror, it came with double-sided sticky foam pads to mount it with. He was skeptical that this would work and glued the mirror on instead - finding that it broke within a very short time later. I deduce that the pads have some role in isolating the mirror from vibration and that when you buy your replacement mirror, you should definitely use them if that's how they come from the auto-parts store.

- I asked the previous person this too (but didn't get a response): Did you look to see whether there was signs of glue or sticky pads on the shards of broken mirror glass? That would be a clue at least. SteveBaker (talk) 04:18, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- To reiterate what I mentioned in the aforementioned previous discussion, FWIW, on the several occasions I've had to replace a broken side mirror glass, the replacement glass came with a strong adhesive layer over the whole of the rear surface (covered by a peel-off paper layer): separate glue or adhesive pads was/were unnnecessary. Major UK car component stockists such as Halfords stock a large range of replacement mirrors specific to individual car makes and models, which are generally considerably cheaper than replacements supplied directly by the manufacturers themselves. If Alexsmith44 is not in the UK this information may of course be useless 87.81.230.195 (talk) 09:06, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

Animal Eyes

Why do eyes of animal light up thus when photographed ? And why the same does not happen with humans ? Jon Ascton (talk) 01:07, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- They probably have much better night vision than we do. I'm sure there's an article about that phenomenon somewhere. Very noticeable with cats, for example. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 01:10, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- I don't think that's got something to do with that. Cows are not known for their sight, they can't even discern colours Jon Ascton (talk) 01:16, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Bingo. I looked up night vision and it led me to Tapetum lucidum, a layer of tissue in the eyes of many animals but not in humans. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 01:13, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Um...the same does happen with humans. See red-eye effect. Under the right conditions (low light, high sensor sensitivity, subject looking directly at lens), I've seen human eyes glow much brighter than those cow eyes. --Bowlhover (talk) 01:29, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- You don't get that "mirror" effect with humans that you do with animals that have that layer in their retinas. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 01:32, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- It's of note that red-eye effect and eyeshine are actually two different effects. And notably, red-eye is just seen in photos. Eyeshine you can actually see in nature (shine a flashlight on your dog at night, for example). And note that the cow's photo is in daylight. --Mr.98 (talk) 11:17, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Goa'uld? -- 58.147.52.199 (talk) 13:33, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- That cow has been to some kind of supermax space prison with Vin Diesel. Googlemeister (talk) 14:16, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

Dragonfly

Any idea what this is? --The High Fin Sperm Whale 03:59, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Should we assume that you took that photo in British Columbia since your user page points out that you live there? Dismas|(talk) 04:02, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, you can also assume that since the title says it's in Langley and it has Coordinates. --The High Fin Sperm Whale 04:08, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- If we can't figure it out, you may want to contact the person behind this site. For some reason, their "Gallery" link doesn't actually contain a gallery. Dismas|(talk) 05:17, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, you can also assume that since the title says it's in Langley and it has Coordinates. --The High Fin Sperm Whale 04:08, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Looks like a skimmer to me, family Libellulidae. Possibly male Plathemis lydia, not sure at all. --Dr Dima (talk) 06:45, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

An open tube is placed into a container of water

An open tube is placed into a container of water and a vibrating tuning fork placed over the mouth of the tube. As the tube is raised so a greater length of the tube is out of the water, resonance is heard. This occurs when the the distance from the top of the tube to the water level is 12 cm, and again at 50 cm. Determine the frequency of the tuning fork.

The naïve approach would simply evaluate but this is not correct. hElp?--Alphador (talk) 07:01, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- λ=50cm−12cm? Bo Jacoby (talk) 09:49, 7 July 2010 (UTC).

- No, that's λ/2 because the second harmonic occurs at l = 3λ/4 => λ = 0.78 m => f = 441 Hz (a likely correct answer). The reason why 717 Hz is wrong is because of end correction. MER-C 09:58, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

North American bugs

If I find some random strange looking bug in North America, what are the chances that this bug is unknown to biologists? I know that globally the majority of insects have not been cataloged. But is this true in North America as well? Ariel. (talk) 07:04, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- This will depend on where you find it. I know from my own country that bugs and plants are surveyed much better in the vicinity of a major university and in locations that are easily accessible. The chance of it being unknown is also not necessarily larger if it is "strange looking". It is the case with many plants and fungi that they are overlooked by biologists because they are very similar to other species. This could be the case with insects as well. 80.202.238.149 (talk) 10:01, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

Source of stream goes both ways?

The source of the Lawrence Brook is at 40°22′33″N 74°32′32″W / 40.37583°N 74.54222°W. Google Maps shows this coordinate along a stream. One direction is the Lawrence Brook and the other direction is the Devils Brook. Is it a spring that goes both ways? Or are the streams interconnected? Or is the map mistaken and the streams aren't connected at all? Thank you. --Chemicalinterest (talk) 10:59, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- I am not familiar with that stream, but I know of two rivers that have the same source in a marshy area, and on the map they look interconnected. 92.15.27.146 (talk) 20:20, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks for answering. --Chemicalinterest (talk) 20:42, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

Is it fair to say that the 4th dimension is not time?

When I was younger, it was my understanding that time was the fourth dimension. But this isn't correct is it? I checked out wiki's article on the 4th dimension, and it made no mention of time in it. Just wanted to make sure that time and the 4th dimension are two different things. 148.168.127.10 (talk) 14:48, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- It is mostly a matter of semantics. The debate is a question of what gets to be called the "fourth dimension". Should it be time? Should it be a spacial dimension? Much of modern physics is based on a concept of more than five dimensions (I believe 10 is the current best guess). So, is time the fourth dimension or fifth dimension or sixth dimension? Does it matter? Again, it is a debate that will likely never be resolved. -- kainaw™ 14:51, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- There are indeed physical theories with more than 4 dimensions but they are all speculative. Sticking with what is considered solid knowlege, space-time has three spatial dimensions and one temporal one, so it seems fair to call time the fourth dimension. Dauto (talk) 17:33, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- To clarify something: the "ordinality" of the dimensions is meaningless. That is, there is no particular significance to which dimension you consider "first", which you consider "second", and so forth. While we conventionally refer to time as "the fourth dimension" because we're already used to considering the other three, I put forth that it's more correct to say merely that "time is one of the four dimensions". Note that this can be extended to the higher-dimensional theories, too; I'm just using 4D so as not to write out all the other possibilities. — Lomn 18:03, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- There isn't even a set of dimensions that one could assign an order to. You can't point in three specific directions and say that those are the three dimensions of space. Or rather, you can, but there are many different ways of doing it and no one way is more correct than all the others. Even the division of spacetime into "space" and "time" dimensions is somewhat ambiguous because they mix together. -- BenRG (talk) 19:22, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- There are varying conventions. A lot of authors put time as either the first or the zeroth dimension. --Tango (talk) 21:23, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- To clarify something: the "ordinality" of the dimensions is meaningless. That is, there is no particular significance to which dimension you consider "first", which you consider "second", and so forth. While we conventionally refer to time as "the fourth dimension" because we're already used to considering the other three, I put forth that it's more correct to say merely that "time is one of the four dimensions". Note that this can be extended to the higher-dimensional theories, too; I'm just using 4D so as not to write out all the other possibilities. — Lomn 18:03, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

So the first three dimensions that we are used to are all spacial dimensions. But time is not a spacial dimension correct? The tesserect exists in a spacial dimension right? 148.168.127.10 (talk) 18:17, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- That's right. Time is not a spatial dimension and a tesseract needs four spatial dimensions, not three of space and one of time. -- BenRG (talk) 19:22, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- If you want to talk about arbitrary assignments in both space and time, note that spacetime can be represented as a metric tensor defining how the dimensions interrelate. In particular, the standard basis of flat spacetime is the simplest, yet still arbitrary, representation of this vector, as we could just as easily choose a basis that mixes in some time components with each of the spatial dimensions. It would be ugly, but it would work just the same. You should also note that in General Relativity, the presence of a gravitational field causes the metric used to change, effectively changing the shape, and thus the metric representation, of spacetime. In conclusion, there is some arbitrariness, but it's not totally haphazard how we choose our dimensions. SamuelRiv (talk) 20:13, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

Imaginary time can be considered to be a fourth spatial dimension. Count Iblis (talk) 22:33, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- It's entirely arbitary. We could have called time "the first dimension" and the three obvious spatial axes "second, third and fourth". But to me it seems bad to lump such an obviously different measure in with the other three. Basically, it's a (slight) mathematical convenience in some sorts of calculations - beyond that, time just isn't similar enough to the three spatial axes to be usefully treated as a fourth "coordinate". Of course, when we talk about three spatial axes, we don't generally have a particularly good idea of what they are. We tend to think of "left/right", "forwards/backwards" and "up/down" - but you could equally choose "azimuth angle", "elevation angle" and "range" as our three spatial 'dimensions'. We tend not to do that because it's a pain to calculate with and it implies a definite origin...but it's really just as valid. SteveBaker (talk) 23:15, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Steve Baker claims "Basically, it's a (slight) mathematical convenience in some sorts of calculations - beyond that, time just isn't similar enough to the three spatial axes to be usefully treated as a fourth "coordinate".

- Steve Baker is WRONG. Dauto (talk) 12:22, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Comment (disagree) for a lot of us still using Euclidean space, calling 'time' the fourth dimension, or equating it as equivalent to the three spacial dimensions we use is either a conceit or entirely wrong. 87.102.42.55 (talk) 13:21, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Sure, but our universe's space ain't euclidian and that's exactly the point. Dauto (talk) 13:40, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Please remember to link to something that agrees with your opinion, as is expected on reference desk answers. Thanks.87.102.42.55 (talk) 13:49, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- There. Dauto (talk) 13:59, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- See also this. Dauto (talk) 14:06, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- You obviously know what you are talking about, so why don't you make a proper effort to communincate it. Your hidden link to spacetime is an article about the model not physical reality, your hidden link to general relativity gives no indication where in that article can be found the relavent answers to the question. Although I could find it stated that the symmetry of 'spacetime' is different, I couldn't find out why you think it is physically true.87.102.42.55 (talk) 14:15, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- See Tests of general relativity for some of the more important experiments and observations that overwhelmingly confirms the reality of spacetime warping (non-euclidian spacetime) in acordance with the predictions of general relativity. Dauto (talk) 14:27, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Of course - space is warped and time is warped (and so is mass) - nobody is denying that. However rolling all of those warpages in to a single mathematical object and calling it "spacetime" doesn't mean that space and time are merely aspects of the same thing. They very clearly aren't. For example, it's very easy to find things that are not time-reversible (entropy, for example) - but it's almost impossible to find things that are not space-reversible. You can pick up an object and rotate it through all three spatial dimensions - but you can't rotate it about the time axis. A physical object can have a limited extent in X, Y and Z (imagine a 3 meter cube) - but it can't have a limited extent in time without violating the conservation laws by popping into existence from nowhere, existing for 3 seconds, then popping out of existence again. Spacetime is a mathematical convenience - a handy shorthand, no doubt - but trying to cram what time is into the 'space' mold - or vice-versa isn't a generally workable thing. For a moving object, velocities (dx/dt, dy/dt, dz/dt) are all constrained by the speed of light - but directions (dx/dy, dy/dz and so forth) can take on literally any value without difficulty - time is special and different in that regard.

- Time and space are very different things that just happen to share a few common behaviors (like the way they are warped by gravity). Conflating mathematical and descriptive convenience with physical reality is a dumb idea. Sure, in YOUR discipline, it's handy to imagine space and time as a single four-dimensional system...heck, I do computer graphics for a living and sometimes it's convenient for me to work in 6D space (X,Y,Z,Red,Green,Blue) - or sometimes 15 dimensional space with surface orientation adding nine more dimensions. Doing that sometimes produces some nice mathematical insights and shortcuts - but that's not to say that color space and physical space and 'orientation space' are "the same thing" - it's just temporarily useful to treat them as if they were. (eg Take two smoothly colored triangles that share a common edge: ABC and ACD. Can you replace them with the two triangles ABD and BCD and have the result look the same? Yes - but only if ABCD is 'planar' in 6D space!) There are yet higher numbers of dimensions which are mathematically interesting too: Some people like to work in configuration space where every single property of every single fundamental particle is a 'dimension' and you have an insanely large number of dimensions where the entire universe can be represented by a single point and the trajectory of that point as a function of time is all of physics. This seems crazy - but the network protocol for a game I'm writing works like that (although I'm obviously not going down to the level of fundamental particles)! SteveBaker (talk) 21:11, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- See Tests of general relativity for some of the more important experiments and observations that overwhelmingly confirms the reality of spacetime warping (non-euclidian spacetime) in acordance with the predictions of general relativity. Dauto (talk) 14:27, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- You obviously know what you are talking about, so why don't you make a proper effort to communincate it. Your hidden link to spacetime is an article about the model not physical reality, your hidden link to general relativity gives no indication where in that article can be found the relavent answers to the question. Although I could find it stated that the symmetry of 'spacetime' is different, I couldn't find out why you think it is physically true.87.102.42.55 (talk) 14:15, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Please remember to link to something that agrees with your opinion, as is expected on reference desk answers. Thanks.87.102.42.55 (talk) 13:49, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Sure, but our universe's space ain't euclidian and that's exactly the point. Dauto (talk) 13:40, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Comment (disagree) for a lot of us still using Euclidean space, calling 'time' the fourth dimension, or equating it as equivalent to the three spacial dimensions we use is either a conceit or entirely wrong. 87.102.42.55 (talk) 13:21, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Steve, you are clearly a very smart person and very knowlegable as well but you also clearly don't know enough about relativity (you know less than what you think) and should probabily refrain from answering questions about that subject. I'm sorry to say but you are dead wrong. Space and time are indeed different apects of a single thing. This is not just a mathematical convenience. In your example where you use a 6D space that includes color and regular space the two different things never mix. Color always remains color and space always remains space. That is indeed just a mathematical convenience. But in relativity space and time do mix (despite your claims to the contrary). that mixing is what is behind lorentz contraction and time dilation. What is time for one observer may be space for a different observer and vice-versa. That's the crucial point that I'm trying to make, spacetime is a physical reality. The warping of space and time by gravity also mixes them. For instance, inside a black hole the radial direction becomes time-like with the future direction pointing inwards. That's why nothing can lieve a black hole. In order to exit the hole something would have to move back in time which is impossible. Sure, you made many points that show that time and space are clearly different from each other but, despite your efforts, you have not shown that they are not different aspects of asingle thing. Dauto (talk) 03:35, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- In context, I took Steve's remark to be an objection to the old convention, which is indeed a mathematical convenience in a few situations, but overall not a particularly helpful way of thinking about spacetime. It tries to make a semi-Riemannian manifold look formally like an ordinary Riemannian manifold, which it just isn't. --Trovatore (talk) 10:34, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- Steve, you are clearly a very smart person and very knowlegable as well but you also clearly don't know enough about relativity (you know less than what you think) and should probabily refrain from answering questions about that subject. I'm sorry to say but you are dead wrong. Space and time are indeed different apects of a single thing. This is not just a mathematical convenience. In your example where you use a 6D space that includes color and regular space the two different things never mix. Color always remains color and space always remains space. That is indeed just a mathematical convenience. But in relativity space and time do mix (despite your claims to the contrary). that mixing is what is behind lorentz contraction and time dilation. What is time for one observer may be space for a different observer and vice-versa. That's the crucial point that I'm trying to make, spacetime is a physical reality. The warping of space and time by gravity also mixes them. For instance, inside a black hole the radial direction becomes time-like with the future direction pointing inwards. That's why nothing can lieve a black hole. In order to exit the hole something would have to move back in time which is impossible. Sure, you made many points that show that time and space are clearly different from each other but, despite your efforts, you have not shown that they are not different aspects of asingle thing. Dauto (talk) 03:35, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- I don't think that's what he meant. May be he should clarify his objection. Dauto (talk) 17:32, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- Dauto - except time mixes with (flat) space with an opposite metric component. Basically (for those watching), the "distance" between event A and event B is the spatial separation minus the time separation (relativistically scaled). That's what Steve means - they are fundamentally different. SamuelRiv (talk) 09:37, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, obviously time and space are different. We don't need any math to know that. But they are also different aspects of the same thing. They are dimensions of a single manifold known as spacetime continuum. Dauto (talk) 10:27, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- Okay, so we agree. This whole thread is about the math, though, since it's basically addressing what we mean by the fourth dimension, and why it's different from the spatial dimensions. They are the same in that we can make arbitrary rotations of the basis vector, and they are different in that such rotations are not actually arbitrary - there is a bias for time standing alone. SamuelRiv (talk) 19:13, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- Not quite. It is true that spatial rotations always mix two space dimensions and never mix the time with a apatial dimension. On the other hand, a lorentz transformation (due to relative movement between two reference frames) always mix a spatial dimention with time. The lorentz transformation is the equivalent of a rotation involving the time axis. Dauto (talk) 02:53, 10 July 2010 (UTC)

How do they use fusion reactors to make electricity?

The conclusion of the thread above about someone being locked in a fusion reactor was that he'd be fine and wouldn't be killed by heat. So how do they use a fusion reactor to make electricity? I thought they'd use a steam turbine like they do with almost every other method of generating electricity, but it doesn't seem sufficient for that. What do they do?--92.251.137.196 (talk) 15:53, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- The glib answer is that they don't use any existing fusion reactor to generate electricity. Existing experimental fusion reactors are designed to test the principles and demonstrate plasma confinement, rather than to supply the grid with electricity. (I can demonstrate the use of hydrocarbon combustion to generate surplus energy by lighting a candle, but I won't be able to spin a large turbine that way.) Once reactors are built which can sustain high average power output – tens or hundreds of megawatts, at least – for hours or days at a time (rather than seconds or fractions of a second) then the surplus heat will be used for power generation, and you'll see reactors coupled to heat exchangers, steam turbines, and generators.

- (As an aside, I would also take the assertions above about the dangers of the interior of an operating fusion reactor with a grain of salt, as they rely on a large number of guesses and few proper sources. One link notes that the JET reactor has sustained a fusion output of 5 MW for 5 seconds, with a heating input power of about 20 MW. That's a non-trivial amount of power floating around — 25 MW for five seconds will do more than warm you slightly....) TenOfAllTrades(talk) 16:19, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- The basic mechanism is that nuclear fusion reactions occur in the plasma. These emit gamma rays, which travel out of the plasma and strike the interior of the reactor vessel, which is lined with blocks of an absorbent material (perhaps vanadium or carbon fibre). The gamma rays are absorbed, which warms the blocks. Around the outside of the blocks (outside the reactor torus itself) are wrapped cooling coils filled with a fluid (say water). The fluid warms, expands, and this expansion causes it to turn a turbine. The turbine in turn turns an electrical generator, which creates the electrical current. -- Finlay McWalter • Talk 16:32, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- I goofed somewhat: depending on the fusion reaction, most of the energy is from fusion neutrons rather than gammas. -- Finlay McWalter • Talk 20:58, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Hmm why wouldn't a person inside a reactor also heat up?--92.251.236.7 (talk) 23:12, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- It's perhaps worth noting that all of the discussions of humans being cooked at the center of the reactor are focused on JET, which cannot produce electricity. ITER, which could hypothetically produce more energy than it takes to start the reaction, is a much larger beast and presumably has different plasma temperatures and densities. --Mr.98 (talk) 00:56, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Hmm why wouldn't a person inside a reactor also heat up?--92.251.236.7 (talk) 23:12, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- I goofed somewhat: depending on the fusion reaction, most of the energy is from fusion neutrons rather than gammas. -- Finlay McWalter • Talk 20:58, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Fusion_power#Subsystems describes a couple of the different ways you could turn fusion power into electricity. --Mr.98 (talk) 22:11, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- According to our fusion power article, the rate at which neutrons deposit energy in the plasma-facing components of a full-scale fusion reactor will be around 10 MW/m2. For comparison, the surface power density of direct sunlight at the surface of the Earth is around 100 W/m2. So, roughly speaking, the neutrons releasd by the fusion reaction heat the walls of the reaction chamber (and anything within it) with an intensity that is 100,000 times greater than the noon-day sun. Gandalf61 (talk) 11:01, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

Cookie/cake mixes

I was just wondering how when for example Betty Crocker creates a cookie or cake mix in powder form, I see some of the ingredients are or were liquid like corn syrup or milk or oil, even molasses- become in powder form, how can you change a liquid like that into powder or flour form? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 71.137.252.54 (talk) 17:28, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- The simple method is dehydration. That is why you have to add water to the mix. There are many methods of dehydration. It is impossible to know specifically which method the cake mix used to become a powder unless the manufacturer feels like exposing the process. -- kainaw™ 17:31, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, although oil can't be changed into a powder form, and typically for recipes that use very much, it has to be added by the user. Looie496 (talk) 17:49, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

Actinidain allergies

What % of the US population is allergic to Actinidain? Googlemeister (talk) 20:40, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Based on a bit of Google-Scholaring, allergies to kiwifruit are relatively common but I couldn't spot any actual numbers. A paper from 1998, PMID 9564807, identified actinidin (the spelling varies) as the major allergen in kiwifruit, but another paper from 2007, PMID 17845415, found that it is not, at least in the UK, and that the major allergen is a different protein, with levels of allergy to actinidin being minimal. So it seems that the story is not completely clear, but that the incidence of allergy in the USA is likely to be quite low. Looie496 (talk) 21:00, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- (Conflict: your Google-fu is stronger than mine!) Actinidain is one of the allergens for those with kiwifruit allergies. I wasn't able to find any exact figures for kiwi fruit allergies, but according to [3] and [4] and [5], in the UK (which isn't all that different from the US), allergies to kiwi fruit are less common than other severe food allergies, but are common enough to be labelled "significant". This study from 2007, however, found that an unidentified 38 kDa protein was the major allergen recognized by 59% of the sample population, and not actinidain. Hope that helps. – ClockworkSoul 21:02, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

beetles

Hello Science desk

Tonight I saw several large brownish beetles flying around, their wings making a dull buzzing sound. I've never seen these things before. The time was 9:30pm GMT in the UK. What species might they have been? Thanks 82.43.90.93 (talk) 20:56, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Sounds like June Bugs Phyllophaga (genus), but I don't recall if those live in the UK? Googlemeister (talk) 21:06, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Might be the formerly rare but recently burgeoning Cockchafer. Probably wouldn't be hard to catch one of the critters and compare it to the pictures. I'm fairly sure all such large beetles in the UK are harmless! 87.81.230.195 (talk) 21:12, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- The pics look exactly the same as the one I saw. Thanks :) 82.43.90.93 (talk) 21:31, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

Plastic Recycling - Expanding from 1-7 from 1-2 only

For years places typically were only accepting plastic resin codes 1 & 2 for recycling, but now many places in Florida, including my own home town, are beginning to accept 1-7. Is there now a market for the other plastics, and are they actually recycling *all* of the codes, or is it likely that they're only recycling some of the codes but saying 1-7 to avoid the confusion that would occur say if they said 1, 2, 4, and 6? I already know about articles like Plastic recycling. PCHS-NJROTC (Messages) 20:59, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- All the plastics listed in Resin identification code can be recycled. They all have monetary value too; from what I've heard/read about the same price as the equivalent weight of oil (not sure what type of oil?) - so it's likely that they want and will recycle all the types.77.86.6.186 (talk) 21:45, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

How hot is hot water?

I don't see a setting on my water heater. I looked at Water heating#Safety but didn't get much help.

I've lived alone for 11 years and since I don't know how to reset it, the setting must have been the same. A plumber replaced a pipe last winter and I'm not aware that he changed anything. I did ask if he thought the water heater should be replaced (though it is making noises like a rodent now when it loads up or starts heating, whatever it's doing). He said no.

It is true, though, that ever since that pipe was replaced the water seems slightly hotter. Before, I could comfortably wet my hands (briefly) to wash them without turning on the cold if I had done something really disgusting, and I could wash dishes without gloves. Now, it seems too hot.

This is important in case I want to replace the water heater.Vchimpanzee · talk · contributions · 21:20, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- The new pipe could easily be shorter and/or better insulated. Either or those would increase the temperature as it comes out of the tap. You don't seem to have asked a question, though (other than the one in the header, to which there is obviously no meaningful answer). What is it you want to know? --Tango (talk) 21:28, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- There will be some sort of temperature control on the heating (to prevent it boiling etc) - but it may or may not be user-adjustable.

- However, what and where it is depends on the type of heating you've got - ie is it an immersion heater, integrated gas central heating, wall mounted gas or electrical water heater ?? For increased likelyhood of a workable answer the make and model of the heater will be useful.77.86.6.186 (talk) 21:40, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Okay, I was really looking for a general answer about how hot water can be and still be comfortable briefly. Now that I think of it, this thing must have an owner's manual somehwre in this house. It is electric and a cylinder in a closet; that much I know.Vchimpanzee · talk · contributions · 21:50, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Sounds like an immersion heater. All the immersion heaters I've had have been non-adjustable (ie, they're set in the factory). Domestic hot water is usually 60–70 ºC (140–155 ºF) when it comes out the tap. Physchim62 (talk) 22:43, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- According to my mum electric immersion heaters can be adjusted with a screwdriver .. eg don't try this without disconnecting the electricity/know what you're doing etc - I think some versions had a screwdriver adjustable part that could be accessed without removing the top.

- I was told that at 50degrees C water causes reflexive pain that makes it impossible to hold your hand in it. Below that it's hot but bearable.. According to http://www.tap-water-burn.com/ the pain threshold is 106-108 F (that's about 41 degrees C). According to this http://www.bre.co.uk/pdf/WaterNews4.pdf the pain threshold is 46.7C or 116F77.86.6.186 (talk) 22:46, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Sounds like an immersion heater. All the immersion heaters I've had have been non-adjustable (ie, they're set in the factory). Domestic hot water is usually 60–70 ºC (140–155 ºF) when it comes out the tap. Physchim62 (talk) 22:43, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- Okay, I was really looking for a general answer about how hot water can be and still be comfortable briefly. Now that I think of it, this thing must have an owner's manual somehwre in this house. It is electric and a cylinder in a closet; that much I know.Vchimpanzee · talk · contributions · 21:50, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- By the way the standard (in the UK at least) is 60C, which is well above the pain threshold - in every house I've ever lived water from the hot tap on its own was always too hot to touch..77.86.6.186 (talk) 22:55, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- In NZ 60 ºC is recommended for the hot water cylinder. No lower because of the risk of bacterial growth particularly Legionnaires disease but no higher because it's considered just a waste of energy.

- However water from sanitary fixtures provided for personal hygiene i.e. sinks for washing hands, taps in the bathroom, the shower etc (the kitchen isn't included obviously) is not supposed (according to the building code) to be any higher then 55 ºC and lower (45-50) is recommended for homes with young children (45 is required for schools and stuff) [6] [7]. Modern systems usually include a tempering valve (which mixes cold water) for this reason (depending on how this is setup it may or may not affect the kitchen, laundry etc).

- The temperatures are chosen more for safety then being able to comfortably use the water. At 55 ºC it takes on average 10 seconds for a full thickness burn of a child (22 seconds for an adult), at 50 ºC 40 seconds for a child (5 minutes for an adult), I think 45 ºC is considered fairly safe even for a child for long periods of exposure [8] [9] [10] Nil Einne (talk) 23:10, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- By the way the standard (in the UK at least) is 60C, which is well above the pain threshold - in every house I've ever lived water from the hot tap on its own was always too hot to touch..77.86.6.186 (talk) 22:55, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

In the UK the recommended standard temperature for hot water has been increased, to avoid Legionarres Disease lurking in the pipes. If it is the same where Vchimpanzee is, then the plumber may have adjusted the thermostat to increase the temperature. 92.29.125.22 (talk) 08:42, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- I doubt that the plumber actually did anything. The pipe may have caused the change because it's a fairly minor change. I'm going with 77.86.6.186, and if I need a new water heater anytime soon, I'll mention those figures. I stayed in a motel where the hot water never reached the point of being uncomfortable.Vchimpanzee · talk · contributions · 17:23, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- If you told us the brand and model of your water heater, someone may be able to find out where the thermostat is and if it is adjustable. 92.24.188.89 (talk) 18:35, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- I'm somewhat surprised by that. I can understand requiring a 60 ºC storage temperature in the cylinder as with NZ. But requiring/recommending 60 ºC coming out from the pipes seems pointless. Since the water isn't continously flowing and isn't continously heated, unless you have very good insulation on the pipes it seems unlikely the water will stay at 60 ºC in the pipes for long, in fact it could easily drop to within the danger range within an hour or so I would guess if you don't have any insulation on the pipes. So if you are worried about Legionarres Disease in the pipes a better bet may be to flush out the pipes regularly. According to some source I read at 50 ºC it takes between 5-6 hours to kill Legionarres Disease so it doesn't even seem occasionally flushing the pipes with 50 ºC is likely to be much more effective in killing anything that is in them then flushing at a lower temperature (it obviously will depend somewhat how long the water stays that high and how often you flush out the pipes). I've looked for some refs, and the best I can find is [11] [12] and various similar refs which suggest a 50 ºC minimum delivery temperature is required in the UK which still surprises me but isn't as extreme as 60 ºC. [13] in fact recognises that the temperature is not going to stay at 50 ºC in the pipes and simply requires it be 50 ºC within one minute (although does at least say the pipework containing water below 50 ºC should be kept to a minumum), which adds to my confusion. Of course since there doesn't seem to be a maximum many may end up with a close to 60 ºC delivery given the 60 ºC required storage and the fact they probably won't bother installing a tempering valve but I haven't yet found any refs mentioning a 60 ºC delivery is required or recommended in the UK. As an aside, I also found [14] which disputes whether the 60 ºC storage is really necessary or 50 ºC is enough. However issues like stratification and thermostat inaccuracy could be one of the reasons why 60 ºC is chosen as 50 ºC even if it is enough doesn't give much leeway for error. Nil Einne (talk) 20:16, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- The U.S. Department of Energy says that 120º F (so 49º C) is a useful and efficient temperature.[15] 75.41.110.200 (talk) 22:25, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

Finger squashing objects

I look at a clock face with one eye closed, holding my index finger upright in front of my face so it appears at the right side of the clock, out of focus. As I move my finger to the left, in front of the clock face, the clock face appears to "squash" or compress a bit while remaining completely in view before it starts to disappear. Why does it appear to "squash#"?--92.251.236.7 (talk) 23:49, 7 July 2010 (UTC)

- I'm not sure I get what you mean, i'm trying it out but not really seeing any kind of effect.. how far is the clock and how far is your finger from your face? Arm out stretched or near your face? Vespine (talk) 01:45, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Even just looking at the text on the computed screen, if a finger is held very near the eye and moved across the text, the letters move a tiny bit, in the blur next to the finger, before they are covered. They also seem slightly sharper. As the finger moves left and right, the letters nearest the finger move a tiny bit in the opposite direction, as if there were a lens. It may be an effect akin to a pinhole image. What would ray tracing of the image imply? Edison (talk) 02:16, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- I don't entirely understand what the original poster means, but it sounds like the phenomenon they're describing is one arising from the pupil not being a pinhole. That is, most of the time we can treat the pupil as being a point hole, but if some object (like the finger) is held near the eye, but the eye is focussed on a distant object like the clock) then some lightpaths from retinal cells will intersect the finger and some will not, producing a blurred image. -- Finlay McWalter • Talk 02:20, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Well the clock face (or text in Edison's case) actually appears sharper and clearer when "squashed".--92.251.228.73 (talk) 12:25, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- I don't entirely understand what the original poster means, but it sounds like the phenomenon they're describing is one arising from the pupil not being a pinhole. That is, most of the time we can treat the pupil as being a point hole, but if some object (like the finger) is held near the eye, but the eye is focussed on a distant object like the clock) then some lightpaths from retinal cells will intersect the finger and some will not, producing a blurred image. -- Finlay McWalter • Talk 02:20, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Even just looking at the text on the computed screen, if a finger is held very near the eye and moved across the text, the letters move a tiny bit, in the blur next to the finger, before they are covered. They also seem slightly sharper. As the finger moves left and right, the letters nearest the finger move a tiny bit in the opposite direction, as if there were a lens. It may be an effect akin to a pinhole image. What would ray tracing of the image imply? Edison (talk) 02:16, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Light does bend a little bit around object. that phenomenon is called diffraction.Dauto (talk) 11:57, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Your finger is probably acting as a partial pinhole lens. Hopefully the physics of it will be explained at pinhole camera. See also Pinhole occluder and pinhole glasses. 92.24.188.89 (talk) 18:38, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- For anyone who wants a clarification as to the OP's question, a video of head-crushing by Kids In The Hall is quite illustrative. SamuelRiv (talk) 09:41, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

July 8

WTF is that on your ear? AKA fleshy protuberance on the targus?

Here in China I often see people walking around with - for lack of a better word - ``growths`` just in front of their ears - basically just ahead of the targus. Sometimes they're quite small, perhaps 2~3mm tall. Other times they can exceed 1cm in length. Never in my life have I seen these outside of China. I suspect that's because other cultures remove them for cosmetic reasons? In any case, I am VERY curious what causes these growths? what they're called? etc... 218.25.32.210 (talk) 05:21, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

I think the word is tragus 86.4.183.90 (talk) 07:01, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Is it a Preauricular skin tag? I've noticed them in China, too. Maybe it's more common to remove them at birth in the west? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 128.12.174.253 (talk) 06:10, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

I have heard that Lego blocks can be used to make even functionable robots that's with motors and all, how i's done ? Jon Ascton (talk) 10:42, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- You would need additional parts such as motors and bearings and hinges. --Chemicalinterest (talk) 11:17, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- By using the Lego Technics ®/ Lego Mindstorms® kits. CS Miller (talk) 11:37, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes! Lego Mindstorms sets make that really simple. You get motors, gears, wheels, a small computer module, some switches and (in some sets) rotation sensors and light sensors. The computer can be programmed remotely from your PC using either a C-like programming language or in a 'drag and drop' environment where you build things that are like flow charts. People have built some rather impressive robots and both NASA and the "FIRST Lego League" run competitions of various kinds for Lego robots. There is a thriving user community of 'AFOLs' (Adult Fans Of Lego) - of which I confess to being one - they too have occasional challenges (things like: "Build a robot to stack empty coke cans - the biggest stack wins - send in a video of your robot stacking cans - the tallest stack wins"). The Mindstorms sets cost a couple of hundred dollars - and contain enough to do some reasonably complex projects - but it definitely helps to have a larger stock of more traditional Lego and Lego Technics to give you a wider range of component choices. There is also a pretty good used market for such things when parents belatedly discover that their 'little darling' isn't a gifted with computers as they thought! SteveBaker (talk) 18:30, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Are there any YouTube videos available of these impressive feats please? 92.24.188.89 (talk) 18:49, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Searching http://www.google.co.uk/search?q=Lego%20Mindstorms&um=1&ie=UTF-8&tbo=u&tbs=vid:1&source=og&sa=N&hl=en&tab=wv seems to work.

- This seems suitably AWESOME!!! http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eaRcWB3jwMo (got a bit carried away).87.102.42.55 (talk) 20:00, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Are there any YouTube videos available of these impressive feats please? 92.24.188.89 (talk) 18:49, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

KBr (Potassium Bromide)

Potassium Bromide was called in medical education?--אנונימי גבר (talk) 13:28, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Do you mean Kalium bromide or Kalii bromidum [16] aka Kalium bromatum or Bromide of Potash ? 87.102.42.55 (talk) 13:56, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Are you asking "What was it called in medical education?". --Chemicalinterest (talk) 15:22, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

"Shadow Biosphere" life on earth with arsenic DNA backbone?

Last night on the program "Through the Wormhole with Morgan Freeman," this researcher found some cells in Mono Lake that could survive in an environment with arsenic levels thousands of times higher than what most life could stand. The woman sheepishly (to my ears) said it's possible the DNA backbone of the cells in question have arsenic in place of phosphorus, but she just left it at that. Isn't there a way to verify that? (P.S. I read the timesonline article sourced in the Mono Lake article about this exact scientist of whom I am speaking. I'm just surprised it doesn't seem they can verify the composition of a DNA molecule there in their petri dish. I thought we could do that these days.) 20.137.18.50 (talk) 13:53, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- from search of "DNA Arsenate" see [17] quote

The only stumbling block to the idea is that arsenic-based DNA tends to break down quickly. "You don't want to build your DNA out of a compound with a half-life in the order of a couple of minutes," points out Steve Benner of the Foundation For Applied Molecular Evolution in Gainesville, Florida

- Yes arsenic can be detected accurately in molecules - but with only a few percent substitution it could be difficult.87.102.42.55 (talk) 14:06, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

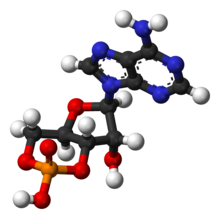

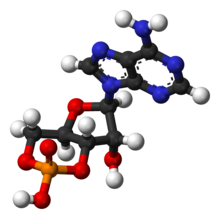

is it present? The skeletal structure looks funny .... does it reflect real life? John Riemann Soong (talk) 15:44, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- The Haworth projection grossly exaggerates the angular difference between 'equatorial' and 'axial' bonds on the sugar structure.

- The ball and stick picture is more accurate - the 6ring is standard (chair) formation, the 5 ring is standard formation too (envolope)

more accurate 3d image - If the question was about the ball and stick image - I think the angle chosen and blue heterocyclic structure makes the image look slighly odd- but it's not - note the two sets of rings are at right angles to each other - so the image has been projected at a slightly 'non-aesthetic' angle.87.102.42.55 (talk) 16:41, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

stimulation of exocytosis of nanoparticles by administration of 8-Br-cAMP

8-Br-cAMP is a lipophilic source of intracellular cAMP that can be added to solution. If I added some to epithelial cells (HeLa, lung cancer, etc.), should I expect gold particles trapped in vesicles to be exocytosed faster? Or would it do nothing if they hadn't reached the ER or a lysosome yet? John Riemann Soong (talk) 16:03, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

I have a point-and-shoot digital camera

It came with panasonic alkaline batteries. They used up in a day or two. OK. Then I changed them, and put brand new zinc chloride batteries, it shows "battery exhausted" even though they are brand new. Why ? Or should one only use alkaline batteries ? What's wrong ? Jon Ascton (talk) 16:17, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Take an ohmmeter across the terminals in your camera. Is the resistance unusually low? 20.137.18.50 (talk) 16:38, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Some ohmmeters use a high enough voltage that they would damage some electronic devices. I would instead measure the current drawn by the device from the usual battery, and perhaps the voltage the battery is putting out under the same circumstances. Care is needed to make sure the battery polarity is correct, the meter is connected with the correct polarity if an analog one, and the battery is not getting shorted out when such a test is done. Sometimes I have made a current probe by inserting as an insulator a piece of paper or very thin plastic between the battery terminal and the battery contact, or between two batteries, with a thin piece of metal on either side of the insulator, which get connected to the current input of the meter. Edison (talk) 14:57, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- No, man the zinc chloride bat are BRAND NEW, just tore the wrapper ! Jon Ascton (talk) 16:49, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Try some alkaline batteries again. If it works, there's your answer. If it doesn't, you've either got yourself a physical fault with the camera (see above with ohmmeter) or a software/hardware fault which would need to be inspected by the manufacturer. Presumably it's still under at least a years warranty? Regards, --—Cyclonenim | Chat 16:53, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Take an ohmmeter across the terminals in your camera. Is the resistance unusually low? 20.137.18.50 (talk) 16:38, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- FWIW, I once bought a package of alkaline batteries and one of them was "dead" straight out of the package. -- Coneslayer (talk) 16:54, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Some zinc batteries will rapidly lose voltage under load - giving a false 'battery dead' reading. This happens usually when the zinc part of the battery is the case of the battery .. batteries using finely divided zinc with more surface area are less susceptable to this effect. This page [18] seems to say that zinc chloride cells also use the zinc can construction.

- Still a good idea to test the battery in something else (like a torch or motor).87.102.42.55 (talk) 17:03, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Check the instructions.. but I'm fairly sure that for digital cameras alkaline batteries (or better) are always recommended.87.102.42.55 (talk) 17:10, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Zinc chloride or Zinc carbon cells are usually prone leaking since the can disintegrates as the battery discharges. This page http://michaelbluejay.com/batteries/ concludes Absolute crap. Do not buy I've got to agree with that. - alkaline batteries are so cheap nowadays and according to the data on that site give more energy per currency unit.87.102.42.55 (talk) 17:16, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- By the way if you can tell us what state you are in I'm sure someone will be able to give a good place to buy the most cost effective batteries.87.102.42.55 (talk) 17:22, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- My digital camera will only work with alkaline batteries, and not with zinc chloride. I imagine the ZC ones do not provide enough power. 92.24.188.89 (talk) 18:32, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- The battery voltage depends on the battery chemistry; alkalines have a slightly different voltage than NiMH rechargeables, and I suppose zinc chloride is slightly different as well. Also, digital cameras (unlike flashlights) draw a lot of current while taking photos and much less at other times, and different chemistries respond differently to that. All digital cameras that use AA batteries are designed to work with NiMH and alkaline, but I don't know about zinc. I'd advise buying some NiMH rechargeables, since they're the cheapest in terms of cost per photo, and also more convenient since they will give you far more photos per charge. -- BenRG (talk) 00:42, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- Ok, Now we have brought home a pack of rechargeable Nippo batteries. I am pasting a picture Are these OK for use in my Nikon Coolpix L20 ?

- Note that they are 1.2 v not 1.5 v Jon Ascton (talk) 16:11, 10 July 2010 (UTC)

- Why did you buy them before finding out if they would work? Googling your camera shows it needs alkaline batteries, so rechargeable alkaline batteries will work but the battery life, especially after several recharges, will be worse than with standard alkaline AA batteries, but who cares, because you can recharge them. Regards, --—Cyclonenim | Chat 17:31, 10 July 2010 (UTC)

- Note alkaline ≠ AA. The camera needs AA batteries, but they don't have to be alkaline, and these aren't. The package says "Ni-Cd rechargeable". According to this spec page, the Coolpix L20 supports "Alkaline, NiMH, Oxyride or Lithium" batteries. NiCd isn't mentioned, but that might be only because it's obsolete (replaced by the superior NiMH). I don't necessarily trust these batteries because I haven't heard of the brand and I was under the impression that nobody made NiCd batteries any more. Also, there's wide variation in rechargeable battery capacity (quoted capacities range from 900 to 2700 mAh at least) and wide variation in charger speed (from <1 hour to many hours—the one you bought says 8 hours), so you should check those specs before you buy. -- BenRG (talk) 19:25, 10 July 2010 (UTC)

- Why did you buy them before finding out if they would work? Googling your camera shows it needs alkaline batteries, so rechargeable alkaline batteries will work but the battery life, especially after several recharges, will be worse than with standard alkaline AA batteries, but who cares, because you can recharge them. Regards, --—Cyclonenim | Chat 17:31, 10 July 2010 (UTC)

- Is it possible that there may be any setting in Camera's menu about which battery to use ? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Jon Ascton (talk • contribs) 22:55, 10 July 2010 (UTC)

- According to this page there is. -- BenRG (talk) 01:06, 11 July 2010 (UTC)

- Is it possible that there may be any setting in Camera's menu about which battery to use ? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Jon Ascton (talk • contribs) 22:55, 10 July 2010 (UTC)

Burning polythene

What is the offensive and acrid gas resulting from the burning of polythene bags? Ethylene is just C2H4 after all. Androstachys (talk) 17:19, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Partially oxidised decomposition products ?? Are you sure it's polyethene - this might interest you http://www.boedeker.com/burntest.htm also see google books .. burn smells 87.102.42.55 (talk) 20:08, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

Polyethylene is a polymer....it's not the same as ethylene. Polyethylene has a lot of sigma bonds. Plus don't forget the presence of plasticisers and stabilisers. John Riemann Soong (talk) 21:58, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- AFAIK the stench is due to pyrolysis and partial oxidation products: low-MW hydrocarbons, aldehydes, ketones, organic acids, that sort of stuff. (Pretty much the same stuff that makes diesel exhaust stink like a sonuvabitch.) FWiW 67.170.215.166 (talk) 03:01, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- If you are getting an acrid gas perhaps you are burning polyvinyl chloride and making hydrogen chloride gas. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 11:10, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

Killer swan mom part 2

Ok, the cygnets hatched out June 12 or 13 and are already larger than the fattest mallard. Their parents are captive swans living in a half of a pond about the size of a soccer field (the other half houses another pair). There's also a pair of nesting common terns (the chicks will apparently fledge in a couple of days), and some poor mallards (of course these are wild, not captive) ... This female swan does not even look at the terns, but for some reason she kills the ducklings. They hide most of the day behind a rock ledge, but as soon as they venture in the open, the swan mom forgets her litter and charges at the ducklings. She reduced the older mallard litter to just one survivor, the other (younger) bunch still holds, but not for long. The swan daddy does not really care, he's obsessed with another male...

Question: do the females behave just as bad in the wild, or it's the price of captivity and tight space? East of Borschov 17:37, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- The BBC's Springwatch programme this year featured a swan's brood being completely wiped out, mostly by such behaviour from other swans, so I would guess it's wild behaviour.--TammyMoet (talk) 20:11, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Swan attack (video) Cuddlyable3 (talk) 00:08, 10 July 2010 (UTC)

The effect of life on light shining through the atmosphere

Now that some crude images of extra-solar planets have been made, would the presence of life make any difference to the light that would pass through the atmosphere of a planet as it passes in front of its star? Could light reflected from the surface of the planet also be detected? 92.24.188.89 (talk) 18:47, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, it is generally believed that living organisms will influence the atmosphere of a planet in ways that could be observed my studying the spectrum of light that has passed through the atmosphere (whether at the limb of the planet as it transits the star, or by reflection off the surface). Oxygen, for example, is not thought to persist well in planetary atmospheres, and must be replenished like it is by plants on earth. See, for example, Terrestrial Planet Finder: Detecting signs of life. -- Coneslayer (talk) 19:08, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Some astronomers are already trying to do that - so it's certainly not unreasonable. There have been several pronouncements about odd chemical imbalances in the atmospheres of Mars and some of the more interesting moons. For example, it was announced that the anomalous amounts of Methane in the atmosphere of Mars could only be explained by there being active microbial life there...until someone suggested that "serpentinization" could be responsible...and now we're not so sure again. The lesson to be learned here is that if we were to find a planet with a lot of oxygen (say), you can bet that "there must be life there!" will be the first conclusion - and then within a year or two of that, "well...we've thought of this other mechanism...so maybe not". What makes it difficult is that when you don't know the composition of the rocks - or almost anything else about the planet other than it's mass and orbital parameters - it's very tough to come up with a definitive answer. SteveBaker (talk) 21:40, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

I wonder how you would seperate the 'signal' of the light shining through the atmosphere of an extra-solar planet from the overwhelming 'noise' of the starlight? 92.24.181.157 (talk) 10:55, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- Conceptually it's not that hard... obtain "baseline" spectra of the star when the planet is not transiting, and then take spectra during the transit and look for "new" absorption features (in excess of the overall decrease of light from the planet's opacity) corresponding to gasses of interest in the atmosphere. In practice, though, it's a challenging measurement, because the absorption features will be quite weak. You have to be very careful about understanding your instrumentation, along with any temporal variations in the equipment, Earth's atmosphere (if using a terrestrial telescope), or the star's light. We are getting there, though. See HD 189733 b; footnote 18 has an arXiv link where you can get a PDF of a paper with Spitzer Space Telescope spectra that are said to show water and methane in the planet's atmosphere. This is a Jupiter-sized planet, though... a small terrestrial planet will be considerably harder. (But I'm 33 years old, and when I was an undergraduate, the discovery of extrasolar planets at all was the Big New Thing. We keep moving forward, and we'll get there.) -- Coneslayer (talk) 17:39, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- It is possible to detect the spectra of certain greenhouse gases in the atmosphere of a planet, for example methane which could be produced by life. See Extrasolar planet#Temperature and composition. ~AH1(TCU) 14:55, 10 July 2010 (UTC)

mythbusters nitro ram recoil.

In a mythbusters episode I saw they used a nitro ram to power a fist that knocked a dummy around, but the pipe that held the fist was just on a stand. So in theory someone could hold the pipe with the fist in and fire it off. So where does the equal and opposite force go that projects the first forward so fast. Does it work something like a recoiless rocket launcher, is there an apposing force? or is the recoil just applied elsewhere?

Thanks guys —Preceding unsigned comment added by 86.129.209.180 (talk) 20:43, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- There is always an opposing force. I'm not familiar offhand with the specific episode, but from your description it sounds like the device is powered by pressurized gas. In that case, the gas can't escape out the fist end of the device, instead escaping out the back -- that is, a rocket. The one force is on the (closed) fist end (propelling the device, per Newton's second law), the other on the (open) exhaust end. Whether the system is recoilless is incidental to the way the forces conceptually work; either way it's a rocket-type system. — Lomn 21:01, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- A ram isn't a rocket. A ram is usually more like a gun - the gas expands behind the ram forcing it out the front and the gas then follows it out. --Tango (talk) 21:04, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- The stand was probably just strong enough to withstand the recoil, so it is the Earth that actually recoils. A person can also throw a punch without falling over. --Tango (talk) 21:04, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

acoustic levitation and spiderman

If objects can be levitated by soundwaves, then is it at least in theory possible to make an acoustic pulse weapon that can knock people down or objects, kind of like how shocker does it in spiderman. Or is there some kind of acoustic cut off point, or limit it can reach in terms of impulse .

thanks and sorry the question is kind of stupid. I was just wondering is all. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 86.129.209.180 (talk) 21:32, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- I think the frog you're thinking of (yes, I know you're thinking about a frog) is the one pictured, which is being subjected to magnetic levitation. Comet Tuttle (talk) 21:41, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

No talking about acoustic levitation.

Thanks —Preceding unsigned comment added by 86.129.209.180 (talk) 21:50, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Can objects be levitated by ordinary soundwaves? It seems unlikely. Sound consists of alternating bands of high and low pressure - the air itself doesn't move bodily outwards from the source - it merely moves back and forth with the motion propagating outwards by no part of the air moving by very much without moving back again. If an object were to get a little 'push' as the sound wave compresses air up next to it - then a half-cycle later, the low pressure part of the wave would suck it right back again...so at best, you could only make your target vibrate (which might be enough to 'kill' it - but not enough to move it physically).

- The "acoustic levitation" trick relies on non-linearities in these properties of the air at extremely high pressures - I think it's more likely that you'd vibrate them to death before you knocked them over. Our article on acoustic levitation says that there is a practical limit of a kilogram or so that can be levitated in this way - but that's not enough to knock over a person.

- There are toys (called things like Air bazooka) which send a single large pulse of compression wave outwards...and giant versions of those like this are able to knocks over stuff like empty soda cans - but that's not like a continuous sound wave, material actually travels along the path of the compression - you can see this happen when people use such machines to shoot smoke rings. It's generally a bad idea to try to learn physics from spiderman comics! SteveBaker (talk) 21:56, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- I've heard there's a variant of the Brown note that makes you lose your balance and actually exists. I might be wrong about that second part. 67.172.112.226 (talk) 22:06, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

Of course it's possible to make an acoustic pulse that will knock people down: just set off a suitably sized explosion. If you want to do it with a non-explosive device, that'd be harder. --Anonymous, 16:30 UTC, July 9, 2010.

- No - an explosion isn't like sound. It's large amounts of gaseous products from the rapid combustion of the explosive - that bodily moves outwards. Sound is a back-and-forth motion - which is why this is a problematic suggestion. At any given point along the path of a sound wave, the pressure alternates higher and lower than the 'ambient' air pressure. Which exerts alternating outwards and inwards forces on whatever it impacts. With an explosion, a few kilogrammes of gas (which is a LOT) move outwards - bodily in an effort to equalize the pressures everywhere. The pressure at any given point goes up as the shock wave goes by - and then gradually falls back to ambient. It never gets below the ambient air pressure so it never 'sucks' the object it hits back towards the source...but that's precisely what DOES happen with sound - and ordinarily the outward 'push' is immediately and perfectly counteracted by the inward 'suck'. Explosions only 'push'. The physical motion of that gas at great speed is what imparts the net force onto the object - and the force is ONLY away from the source. The only way for 'sound' to do this is for some very extreme thing to happen where the sound is so spectacularly loud sound that the air pressure drops to zero in the low pressure parts (and can therefore drop no further) - or the high pressure parts hit some non-linear effect within the gas (like it liquifies or something). That produces asymmetry between high and low parts of the sound wave which really can produce a net outward force. But that's crazy loud sound! SteveBaker (talk) 03:44, 10 July 2010 (UTC)

- Good point. However, you're talking about the blast and I was thinking of the shock wave, which is felt much farther away. I'm not sure to what extent, if any, it involves back-and-forth motions like ordinary sound, but I think the fact that it propagates through the air as a wave qualifies it as sound even if it does move supersonically. --Anon, 05:13, July 10, 2010.

Forest terminology — non-coniferous?

Can't for the life of me remember if there is a term to describe forests consisting only of leafy trees, as opposed to those containing pines, furs, and so on. Is there such a term that I can use in contrast to coniferous? Spent the last hour or so reading about trees to no avail. BigNate37(T) 22:07, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Deciduous or hardwood. Not that all deciduous trees are hardwood, and not all hardwood is hard (eg balsa) CS Miller (talk) 22:12, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Perfect, thank you. BigNate37(T) 22:19, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- And not all hardwoods are deciduous. Googlemeister (talk) 13:25, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- Broad-leaved might be a better bet. Alansplodge (talk) 23:18, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

- And not all hardwoods are deciduous. Googlemeister (talk) 13:25, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

dehydrated yogurt

will dehydrated yogurt spoil quickly if left sealed in a package on the shelf and not refrigerated? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 71.137.244.115 (talk) 22:20, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Please clarify what you mean by "dehydrated yoghurt". That could mean half a dozen things, and I don't feel like trying to give all the possible answers (even if I could!). Looie496 (talk) 22:50, 8 July 2010 (UTC)

- Dehydrated yoghurt is probably similar to dehydrated milk that keeps indefinitely in powdered form without refrigeration, and can be carried as part of a trail snack. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 10:24, 9 July 2010 (UTC)

Evolution and entropy

Why isn't the accumulation of beneficial mutations a violation of entropy? Is it because we assume that accumulations of neutral and disadvantageous mutations also occurs, but that the former is silent and the latter causes those involved to perish, leaving only the beneficial mutation accumulators to seem as though they are violating this concept? DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 23:56, 8 July 2010 (UTC)