Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

June 30

The universe, consciousness and the anthropic principle

Hi. Can a property of the universe be said in the following manner? This is not meant to advertise some cranky or crackpotting idea but just for discussion although the following ideas may induce semantic headache. Consider the following.

The product of human consciousness and sapience has been an anthropogenic proliferation in tools, eventually evolving to higher forms of technology, including artificial intelligence. This can potentially be characterized as a localized decrease in entropy, in which energy of chaos is re-positioned to form ordered substances. Although the second law of thermodynamics dictates that entropy must increase over time, localized increases in order via the self-ordering nature of matter are allowed, which is accelerated when consciousness is present.

Given the Big Bang theory of the formation of the universe, matter and antimatter were composed of high energies, infinite temperature and a primordial soup. After this initial energy forced inflation (cosmology) at rates approaching Plank velocities, the matter-antimatter asymmetry allowed the prevailing of matter over antimatter through the help of bosons and other factors. The matter assembled into stars, which later formed planetary systems and were components of quasars and later galaxies, which in turn became ordered into superclusters in bubble-like forms. Complex molecules arose on Earth, eventually forming into prokaryotes, then into complex life, which eventually evolved to humans today, which carry a form of conscious self-awareness.

In this context, the universe over time becomes more and more ordered, and although all matter such as stars eventually explode, the resulting debris forms into new stars and new order. Since both humans and the universe share this locally accelerated ordering capacity, could it be said that the Universe is dually conscious?

Alternatively, does the hypothesized supersymmetry breaking and multiverse scenario more than make up for this local decrease in entropy? Considering a multiverse, supose that its consistuents are order and chaos. Similar to the matter-antimatter duality within our universe, the scenario could either unfold where order prevails (a universe forms), or chaos does (a nearby universe is destroyed). Thus, would the passage of time result in the formation of more universes, so that the total heat contained in all universes increases over time, thus increasing total entropy on a quantum level? Or, can something about dark matter change this effect?

The anthropic principle proposes an almost infinitely long list of requirements for life to exist on Earth, so that the chance of such a universe existing is one over infinity. However, this is easily resolved given a multiverse, in which an infinite number of universes is created and destroyed. Of course, we don't know whether this is the correct infinity.

However, humans have succeeded in creating the basic building blocks of life. If the universe and humans are both conscious, depending on how consciousness is defined, could the existence of conscious life be considered a fractal subset of the macro-scale universe's consciousness? Or, would this only be true in retrospect, as the existence of conscious life itself is required for any realization of the anthropic principle?

Is time thus a non-material dimension, one that results in the conversion between matter and energy to cause the diversion of macro-scale and micro-scale entropies? There is also a human sense of time, which is potentially distinct from the actual flow of time relative to the conscious observer. Can this somehow make sense of the aforementioned context, provided that simultaneity is relative based on different observers in spacetime, so that each observer is positioned so that all other observers' futures in spacetime already exist?

Does any of this make meaningful sense? Thanks. ~AH1 (discuss!) 00:36, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Not really, no. There's no evidence that the universe is conscious. The final few paragraphs look more like rubbing a set of random concepts together than anything else. --Tagishsimon (talk) 00:42, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- (edit conflict)I don't have the mental energy right now to fully wrap my mind around your whole argument, and you touch on a large number of highly-speculative and non-falsifiable topics (thus your whole argument here may be more philosophy than science), but I do have a few points:

- You make the assertion that human consciousness is "accelerating" a local decrease in entropy (increase in "order") on Earth which you take as truth; all of this without citation. Now, this may be true, but it would be nice to see some quantification of this before I take it as fact. We may be decreasing entropy on earth by refining metals from ores and extracting other pure materials from nature, but we are doing so primarily through the combustion of fossil fuels, which is a process which results in an overall increase in entropy.

- Even using "renewable energy" such as solar power, wind power, and geothermal power, this energy is ultimately all derived from solar fusion from the Sun, a process which results in a huge increase in entropy.

- You make the further assertion that "the universe over time becomes more and more ordered". This is demonstrably untrue: as I say above, fusion in stars results in an enormous increase in entropy as primordial hydrogen is fused into helium on astronomical scales. If I had some more time I'd do some scale-analysis to give some rough numbers, but it is safe to say it is enormously beyond the scale of any potential local decrease in entropy by humans (which, as I've said above, may not even be true).

- I'm no good on the philosophy front, but I do believe that most definitions of consciousness at least require a conscious entity to present the appearance of self-determinism; the Universe as a whole does not appear to demonstrate this feature.

- Almost infinity is not even close to infinity; the two are not even comparable. The odds of the existence of a universe where humans can live can not be zero because it does exist.-RunningOnBrains(talk) 01:08, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- You also seem to be trying to think of the anthropic principle as a causal mechanism; this is nonsensical, as the anthropic principle is essentially answering the question of "Why are we here?" with "Because we are here." This is an over-simplification of the topic; the anthropic principle is really the only branch of philosophy I've done serious reading and thinking on. It is my favorite principle, since it really allows us to avoid the need to ask the question of why we are here. It helps me sleep better at night.-RunningOnBrains(talk) 01:16, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- (edit conflict)I don't have the mental energy right now to fully wrap my mind around your whole argument, and you touch on a large number of highly-speculative and non-falsifiable topics (thus your whole argument here may be more philosophy than science), but I do have a few points:

- On the issue of conscious entities lowering entropy: this dos not happen. If you clean up your desk, putting things that were initially randomly distributed, in some neat order, then the information needed to specify the initially disordered state is not lost. You have to act on that intial state to get to the final state, so the information about the initial state ends up in your brain. So, as your desk becomes more and more neatly ordered, your brain accumulates more and more random information. You can later forget about what you exactly did to clean up your desk, but then the information gets dumped into the environment. Count Iblis (talk) 01:17, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Entropy, as a quantified theory, is defined on the molecular and atomic scale. Reordering macro objects will not result in a quantifiable decrease in entropy, though it may intuitively seem so to our consciousness. Calling it "localized" implies that the volume in question is less than typical entropy measurements, which is not the case. Keep in mind that moving objects, and even thinking of moving objects, increases entropy by converting food to more basic molecules (much like the fossil fuel reference mentioned). Mamyles (talk) 02:59, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- There's a common fallacy which is the notion that the complex can't naturally arise from the simple. It's often evoked for instance by proponents of intelligent design. They argue that the world is complicated and beautiful, which proves that it can't adequately be explained by reducing things to simple laws of nature. The world has to have been caused by something equally complex and beautiful (god). It's understandable where this misconception comes from. There are a lot of situations in our lives where we're actively maintaining some sort of order, and when we neglect things they break down. But as anyone who's ever spent any quality time with math can tell you, beauty readily sprouts from mundane beginnings all the time without the guiding hand of any conscious being, and we've found that this remarkable trend tends to carry over to our study of the universe (for more on that see the recent question on the math desk).

- Here you seem to be making a similar argument about the impossibility of an interesting universe arising naturally without some "consciousness" guiding it, wrapped in (an incorrect reading of) the concept of entropy. Entropy doesn't measure how boring the universe is. With all the galaxies and stars and planets and life engaged in their beautiful dance, entropy is much higher than at the start of the universe when everything was a single boring (but maximally ordered) point. The magic is that bunch of deceptively simple laws (including the second law of thermodynamics) got us from there to here. Rckrone (talk) 04:04, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

Let's consider the life of "Adam", the first conscious being. In the interests of simplicity I will neglect to define whether Adam was man, mouse, or microbe; but his brain (or processing center of similar function) possessed the bare minimum requirement for what we define as a conscious observer. Thus there is one moment at which Adam is aware of consciousness, but ignorant of all else.

In that moment, Adam is, I would suppose, in a superposition of states, like Schroedinger's Cat. He might be Earthling or alien, with any number of possible biochemistries, in any number of universes with any number of laws - all existing as a mad superposition of states. But he stirs his limbs, and the state-vector collapses - as if struck by the divine spark, he becomes carbon-based life, with arms and legs; he takes on a defined form. Many others no doubt were possible. He opens his eyes and looks up to the darkened heavens - and at once, the state-vector of the skies collapses, and the stars, once a homogeneous smear of probability, take on their fixed and immovable positions. Wnt (talk) 05:53, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Then he turns to the ominously fertile apparition at his side and simultaneously presents himself and enunciates the first palindrome: "Madam I'm Adam". Cuddlyable3 (talk) 12:00, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- It seems like a rather awkward QM interpretation to sharply distinguish between living and non-living objects. Rckrone (talk) 16:49, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Carl Sagan liked to say that conscious life is the way in which the universe eventually knows itself — we are made from the universe, we have evolved to the point where we can study the universe, and so in a very holistic way, this makes the universe "conscious" (in the sense that it contains consciousness, in the form of us, among other critters). It is indeed a fairly deep idea if you take the time to really contemplate it, and don't just dismiss it as wordplay. This is separate from many of your other questions. --Mr.98 (talk) 16:45, 4 July 2011 (UTC)

- The idea of a multiverse is not something requiring new physics. Consider a slightly altered version of Schroedinger's cat in a box: you place a completely automated in vitro fertilization clinic into the box, complete with an artificial womb, and don't bother opening the box later on. Now the box exists in a superposition of states: in some the equipment broke down and nothing happened, but in a few, it successfully reared an infant. Doesn't the anthropic principle apply, namely, that the successfully conceived infant's perspective prevails over the other possibilities ... from the infant's perspective, at least? Wnt (talk) 13:40, 6 July 2011 (UTC)

String theory and time travel

| Collapsing -- Wikipedia RefDesks are not a forum for presentation of original speculation |

|---|

| The following discussion has been closed. Please do not modify it. |

|

Hi. Assume for the purposes of this question that String theory is correct. The theory makes the assumption of 11 dimensions, some of which are branes. Suppose three of these dimensions are the spatial dimensions, and that time is the fourth dimension. Since strings are said to vibrate in the eleven dimensions, could a string in itself travel back and forwards in time, similar to quantum teleportation, except that these sub-quantum entities travel in the fourth rather than the 1-3 dimensions? If a particle collider were to harness enough energy to isolate strings, if they exist, let's say through the use of a Dyson sphere or some type of Higgs boson technology, could time travel or time-teleportation theoretically be achieved? Since string theory supposes an infinite number of particles, far more than the current Standard Model, the mathematical singularity of a black hole would transcend some of these particles and reduce matter to infinite density at the string level. Since this requires energies capable of producing strings, could this allow time travel in the context of a wormhole via the tapping of the string energies? Could the black hole itself time travel to an earlier state in which it did not exist, thus evaporating into Hawking radiation and dissapating into dark energy? Also, if time is one of the dimensions in which strings vibrate, how can the vibration occur without the flow of time? If strings were to travel in the fourth dimension, would the vibrations stop, or would this induce a parity in the time reversal symmetry present in any oscillation? Is this thus a form of supersymmetry breaking? If strings vibrate based on an infinite particle number, could some high energy cause the vibrational frequency to change, and thus turning a neutron into a photon plus some energy, let's say? Or, perhaps create gravitons or other particles responsible for the other fundamental forces, so that the strings themselves impart force when enough energy is applied? There are still many theories for light, including wave-particle duality and the neutrino theory. Apart from the existence of some disproven aether, would light simply be a form of converted energy, similar to the way that photons carrying energy cause electrons to jump to a higher level, releasing more energetic photons? Could strings facilitate this conversion, and generate new energy from particles? At quantum levels, the observer effect becomes amplified, as seen in the quantum Zeno effect for the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. Is it conceivable that human observation is adjusting the vibrational frequencies of the strings, thus quantum-teleporting this string-information onto the later-observed states and momentum of the observed particles? Also, is it possible for an observer in the future, through this mechanism, to influence the quantum states of particles in the past, providing ostensible evidence of retrocausality and other retrospective mechanisms? Responses welcome. Thanks. ~AH1 (discuss!) 00:59, 30 June 2011 (UTC) |

- Can I ask one question: can strings theoretically time travel? ~AH1 (discuss!) 01:51, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- So far as I know, all subatomic particles, real or proposed, exist in four dimensions, time being one. And most of them exist in a way which is in some sense symmetric over time (CPT symmetry). So when you ask if strings can time travel, well, you might have a string at one time, which exists in another time, earlier or later. Now can a change to a string later "cause" a change in the string earlier? That depends on the nature of "causation", which seems to me to be essentially religious, if not superstitious. Wnt (talk) 05:59, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

Request for RDS regulars to help with a teensy problem on another board...

Over at Wikipedia:In the news/Candidates, there's a consensus developing to have a blurb about a recently discovered quasar. However, no one has the science background to update or create a target article for the blurb. See the section "Brighest Object in the Galaxy found yet" We could use someone with astrophysics knowledge to pitch in to help work it out. Science is a heavily underrepresented topic in all areas of the main page, and ITN is no exception, so when a particularly good event comes along we don't want to miss the opportunity to use it. --Jayron32 01:56, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Well, the person who could create that article is certainly not me, but I will make one correction: the object is clearly not in our galaxy. According to the article, it is the most distant object that has ever been observed. Do you think it would make sense simply to correct our quasar article, which currently says that all known quasars have redshifts between 0.056 and 6.5, to an upper limit of 7.085 (as reported in the Nature paper), and cite the paper? Would that be enough to justify a news item? Looie496 (talk) 02:11, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Superlative objects (biggest, farthest, fastest, brightest, whatever) with good confirmation as to their superlative status are generally good topics for being stand-alone article subjects. Having Nature call you the brightest or farthest object known is a pretty solid aspect of notability, though again I (nor anyone currently working at WP:ITN/C) has the background to take on such a task. --Jayron32 02:24, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- For what it's worth, this Scientific American news piece tells the story in a pretty understandable way. Looie496 (talk) 02:26, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Good stuff. There's an honest-to-goodness astronomer who has made a few comments, and indicated he may get around to working up an article in the next day or so. Of course, more help is more better. --Jayron32 02:29, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Well, I just started one, ULAS J1120+0641. I'll say more at the ITN page. Looie496 (talk) 03:11, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Good stuff. There's an honest-to-goodness astronomer who has made a few comments, and indicated he may get around to working up an article in the next day or so. Of course, more help is more better. --Jayron32 02:29, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

slow neutrinos

Hi, is there any FUNDAMENTAL reason why neutrinos could not be slowed down relative to us on Earth? If some type of exceedingly inelastic collision mechanism could be devised, couldn't scientists start collecting slow neutrinos? Once they are slow, wouldn't they stay slow? Conceivably the neutrino cross section would increase as they slowed down?Thanks, Rich Peterson24.7.28.186 (talk) 04:04, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- In principle they can be slowed down, but their cross-section would decrease. Have a look at formulas - the various cross sections are proportional to the energy or to the square of the energy. Icek (talk) 08:55, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- The link you posted seems to be broken. Dauto (talk) 15:35, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- This is the link to the entire page, which gives various sets of equations. I would guess that the second set is the one you want, but hopefully Icek will reappear and confirm it. I don't have enough background in the mathematics to see what equations on that page have the property he/she describes. Wabbott9 Tell me about it.... 15:51, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- All of them do. Dauto (talk) 22:07, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- thank you.24.7.28.186 (talk) 02:45, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- All of them do. Dauto (talk) 22:07, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- This is the link to the entire page, which gives various sets of equations. I would guess that the second set is the one you want, but hopefully Icek will reappear and confirm it. I don't have enough background in the mathematics to see what equations on that page have the property he/she describes. Wabbott9 Tell me about it.... 15:51, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- The link you posted seems to be broken. Dauto (talk) 15:35, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

Plugging in and electrical use

I'm trying to save electricity, for the sake of both the environment and my bills. ;) So two questions:

(1) Do appliances such as fans with a plain adaptor-less power cord and no digital display (e.g. clock) use any electricity when they are turned off but still plugged into the electrical outlet? That is, would I save any energy by unplugging appliances even when they are turned off, or does being plugged in or not make no difference as long as the appliance is already turned off?

(2) What about devices that use AC adaptors? I find that even when I turn off the device, if I leave the adaptor plugged in, then the adaptor stays warm to the touch, suggesting it is still using electricity.

Also, if unplugging does indeed save power, are there any negative side effects to frequent unplugging?

—SeekingAnswers (reply) 05:56, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- The phrase for those adaptors (and myriad other usages) is "power vampire". I still have no idea why corporate idiots decided to get rid of perfectly good 1 - 0 power switches that you could be confident about, and replaced them with things that consume more power while doing nothing than when active. There's just no plausible excuse. Wnt (talk) 06:03, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Can you give an example of a "thing that consumes more power while doing nothing than when active? Cuddlyable3 (talk) 11:30, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Consume more energy would be the right phrase. You buy energy not power. The CD-Player in the guest room only ocupied two weeks a year would be a clear point which would consume more during the 56 weeks in stand-by while working for 5 minutes during the guests are in the room. --Stone (talk) 11:44, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- However just being there available to spring into life anytime you want is, like a burglar- or fire alarm that is never triggered, not nothing. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 19:55, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Consume more energy would be the right phrase. You buy energy not power. The CD-Player in the guest room only ocupied two weeks a year would be a clear point which would consume more during the 56 weeks in stand-by while working for 5 minutes during the guests are in the room. --Stone (talk) 11:44, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Can you give an example of a "thing that consumes more power while doing nothing than when active? Cuddlyable3 (talk) 11:30, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Mechanical appliances do not normally use power when turned off, but there is an additional element of safety if they are switched off at two places. Appliances with "AC adaptors" (usually switch-mode power supplies) use a tiny amount of electricity when plugged in, but much less than a penny a day when not being used. I leave mine plugged in for convenience, but I live in a cold climate where the tiny amount of heat is beneficial. People who are fanatical about energy conservation always turn them off when not in use. Dbfirs 07:18, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- If the adapter or phone charger feels warm to the touch when idle, then it is wasting a meaningful amount of energy. Edison (talk) 20:18, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- True, but if the warmth provides background heating, then the energy is not being "wasted". I "waste" much more energy by accidentally leaving lights turned on when they are not needed, but these also provide background heat. Of course, if your house is hot enough to need air conditioning then the energy really is being wasted. Dbfirs 07:59, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- The waste energy amounts to electric resistance heat, too expensive for most people in areas with a cold climate. It would be cheaper even in winter to kill the power to the adapter and get the extra heat from a high efficiency gas furnace. In the air conditioning season, waste heat from "vampire power" runs up the air conditioning bill. Edison (talk) 14:39, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- ... true if you already have one, but high efficiency gas furnaces are not cheap! Also, the nearest mains gas is five miles away from my house! Dbfirs 17:57, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- More to the point, while the power adapter thing may work (although I'm not even convinced of that, particularly if you don't use heating 24 hours a day), so far I haven't seen any source which has analysed this in a meaningful way. As I say every time this comes up, I would expect there is some stratification of heat in most houses (e.g. [1]). Most analysis even RS like [2] seem to just presume all heat generated by the lights is going to be as useful as heat generated by purpose build heating systems which as I've said given the stratification seems unlikely to be true.

- Heaters are generally located close to the floor. Lights are located close to the ceiling. Some of the wasted energy that ends up as heat is in the form of thermal radiation (primarily infrared) which would reach the floor and people but the rest is at the ceiling and is likely to stay there if you don't have some sort of convection system which would suggest an increase in the vertical stratification which may not be useful if you aren't Spiderman. (I'm presuming we all know warmer air is less dense.)

- In fact you probably have to consider horizontal stratification too. Many lights are brightest under the light, and humans tend to be away from (but not too far from) the light. But this would also imply a greater amount of the radiative heating happens under the light and while there would be some circulation it seems likely it will be warmest directly under the light which isn't useful if you aren't staying under it. (There's some unrelated discussion here [3] comparing halogen and incandescent infrared lights for heating piglets.)

- In other words, as I say every time this comes up, it's obviously true that wasted energy is going to end up as heat eventually and likely also true not all 'wasted' energy from lights is truly wasted when heating is needed. But if your goal is heating for human comfort then it probably isn't true that the wasted energy completely oversets heating requirements (so isn't wasted). So even if you use electrical resistive central heating, there's a good chance using a purposely and hopefully well designed system will use energy more effectively then using light bulbs intended for lighting the home for the same purpose. Some actual sources to help us determine how incandescent lights in a typical home perform for heating compared to such a system would be useful but so far I haven't see any.

- As a completely unrelated OR example, I had a cheap oil column heater from The Warehouse. It was 1000W as with many such heaters intended for small rooms in New Zealand. You may think it would therefore be as good (ignoring things like timers and safety functions) as any other such heater. However I found (and so did someone else with the same type) that it was rather ineffective. The heater itself got hot, the room not so much. Similar more expensive name brand oil column heaters were better at heating the room. I never measured energy usage (didn't have a plug-in energy meter at the time) but I presume despite both being 1000W it used less then the other heaters since the thermostat would likely shut it off faster and keep it off longer. But I also suspect if you adjusted the thermostat of the other heater until it used the same amount of energy over a defined period, e.g. 6 hours the other heater would have been better at achieving thermal comfort for the occupants of the room over those 6 hours or even an hour or two more after the heater was switched off (if they weren't right next to it).

- Nil Einne (talk) 16:23, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- With light bulbs, some of the energy escapes through the window, of course. In the case of power adaptors, the trick is to place them in a location where the heat will be beneficial, though I agree that the heat will be "wasted" if you didn't want the room to be heated. I don't understand why a more expensive oil-filled heater using the same amount of energy could possibly provide a better "thermal comfort" (unless the surface temperature was higher or lower). A 1000 watt heater would be inadequate for most of the year in the house where I live, but in a well-insulated room in a region with a warmer winter it might provide all the heat needed. Comfort depends on the temperature of the walls, floor and ceiling, not just on air temperature and proximity to the radiator. Dbfirs 11:43, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- The waste energy amounts to electric resistance heat, too expensive for most people in areas with a cold climate. It would be cheaper even in winter to kill the power to the adapter and get the extra heat from a high efficiency gas furnace. In the air conditioning season, waste heat from "vampire power" runs up the air conditioning bill. Edison (talk) 14:39, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- True, but if the warmth provides background heating, then the energy is not being "wasted". I "waste" much more energy by accidentally leaving lights turned on when they are not needed, but these also provide background heat. Of course, if your house is hot enough to need air conditioning then the energy really is being wasted. Dbfirs 07:59, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

Expansion of the universe

Hello,

It is often said that the universe continues to expand, creating new space as it grows. However, this does not seem to fit in with the conservation of energy, since if new space is being created, that means new energy is being created in the form of vacuum energy. Am I missing something?

TIA. Leptictidium (mt) 08:16, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- This has come up before on the reference desk, but I don't have time to search at the moment. Here's a short version. First, it's problematic to say that "new space is created" in an expanding universe, since technically all of the space at a given time is equally new. Space doesn't persist the way matter does. Second, energy actually isn't conserved in cosmology (or GR in general), at least, not in any straightforward way. (This is actually an unsolved problem; quantum mechanics requires energy conservation, and that conflict is one of the reasons quantum gravity is hard.) -- BenRG (talk) 08:37, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

My understanding is that the purported solution to the problem lies in the so-called dark energy. Looie496 (talk) 15:55, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- It doesn't. You can have expansion without dark energy. DE is only required to explain accelerated expansion. --Wrongfilter (talk) 17:08, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

Regenerating electric energy in motor vehicles

in some motor vehicles electric energy can be stored through regenerative braking. so why cant we use this technology in electric cars to recharge the battery using this technology by an additional battery by providing a switchable control between the two? Since by Newton's Law "energy can neither be created nor be destroyed", i dont think dis is impossible..—Preceding unsigned comment added by 220.225.131.153 (talk) 12:32, 30 June 2011

- Energy can not be created or destroyed, but if you convert some of your energy to heat, your car can't use it anymore, so for your purposes it might as well have been destroyed. Googlemeister (talk) 12:46, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Indeed, you could convert heat back to electricity, using a Stirling motor. 88.14.198.240 (talk) 19:13, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- There's no reason you need an additional battery, you can recharge the original battery (or batteries) from the regenerative braking. StuRat (talk) 16:14, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- I have a bad feeling that the OP is thinking of using one battery to drive while braking to charge the other battery, then switching batteries to keep on driving forever. Methinks dat is impossible. Newton was wrong too. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 19:48, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- A motor or generator has losses, which convert some of the energy into heat. If you convert 90% of the input energy into useful output energy you are doing very well. 80% or 70% efficiency or even lower would not be surprising, to convert mechanical energy into electrical with a generator, charge a battery, and get the electricity back out of the battery and converted to mechanical energy with a motor. There are limits on cost and weight in any system used in a car, so there are likely some shortcuts from the very most efficient technology. Edison (talk) 20:16, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

color

I don't fully understand why if a meterial absorbs,say,red light it emits blue light (or looks blue). and generally absorbing one color (wavelength,frequency,whatever)causes the object to emit the inverted color. and what is the definition of invert colors anyway? I searched "invert color" on wikipedia but found no satisfying results!thanks in advance.--Irrational number (talk) 12:56, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- The object doesn't emit the inverted colour, it reflects what's left of the incoming light (let's assume that's white) after it has absorbed some of it. Since now some wavelengths are missing from the reflected light, it takes on colour. For example, chlorophyll absorbs red light and blue light. The remainder is reflected, which is why tree leaves appear green. --Wrongfilter (talk) 13:04, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- I'm afraid that's not correct. If the light were reflected, it would only be visible in certain directions, like the light that bounces off a mirror. Unless the object is shiny, the light is actually absorbed and re-emitted. Looie496 (talk) 15:51, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- No, Wrongfilter is correct. The only difference between shiny and non-shiny objects is that shiny objects reflect all the light back at a particular angle while matte objects reflect light back in all directions because the surface isn't smooth. Objects do absorb some radiation, and radiate heat back into the environment, but that radiation is not primarily visible light unless the object is very hot (such as the sun). See Thermal radiation. Rckrone (talk) 17:08, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- This distinction between "reflected/re-emitted" is really just semantics. "Reflection" is a macroscopic concept; specular reflection and diffuse reflection are statistical descriptions that are relevant for large surfaces and lots of photons. Any individual photon interaction with an individual atom on the surface is a quantum photoelectric behavior. Thomson scattering is commonly used to explain one photon hitting one atom. If the surface is large (compared to the wavelength of light), the aggregate effect of many many individual photon-atom collisions can be either specular or diffuse. It's a bit meaningless to debate whether the photons are absorbed and re-emitted, or merely "bounce off." If the wavelength of an individual photon changed, we usually say it was absorbed and re-emitted; but the same description loses meaning when describing the ensemble of billions of photons. Large quantities of light are better described as a wavefield. Nimur (talk) 21:02, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- No, Wrongfilter is correct. The only difference between shiny and non-shiny objects is that shiny objects reflect all the light back at a particular angle while matte objects reflect light back in all directions because the surface isn't smooth. Objects do absorb some radiation, and radiate heat back into the environment, but that radiation is not primarily visible light unless the object is very hot (such as the sun). See Thermal radiation. Rckrone (talk) 17:08, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- I'm afraid that's not correct. If the light were reflected, it would only be visible in certain directions, like the light that bounces off a mirror. Unless the object is shiny, the light is actually absorbed and re-emitted. Looie496 (talk) 15:51, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Did you see Color#Color_of_objects ? Sean.hoyland - talk 13:10, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Also, there are two confounding issues here:

- 1) There are certain wavelengths of light which are absorbed, and others that are reflected. Sometimes, objects do "re-emit" light (see fluorescence and phosphorescence) but reflected light and emitted light are distinctly different and can be readily identified in most situations. For normal (non fluorescing) objects, reflected light determines what wavelengths reach our eyes.

- 2) Human color perception determines how the incoming wavelengths of light strike our eye and are processed by our brain to produce a distinct color in our eyes. It is not always obvious; for example there are actually two different ways that yellow can be produced for us: a single wavelength of light in the yellow range can look yellow, but light composed of a mixture of wavelengths of light from the red and green ranges, with no actual wavelengths from the yellow range will still look yellow to us. That sort of thing is why we can create a full pallete of colors from a limited number of pigments, see RGB and CMYK for some more info on that. --Jayron32 13:11, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Also, there are two confounding issues here:

- (Edit Conflicts) Despite having studied some Color theory in connection with printing, I've never encountered the term "invert[ed] color. You may however find further enlightenment at the articles Complementary color, Primary colors and Secondary colors. {The poster formerly known as 87.81.230.195} 90.197.66.166 (talk) 13:14, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- I think the definition is approximately the same as a photographic negative: in computer terms, you just subtract the color from the highest value. So for 256 colors, inversion from (X,Y,Z) is (256-X, 256-Y, 256-Z). Am I wrong? Wnt (talk) 23:41, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, the highest value is 255. Icek (talk) 09:24, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Ack, I knew that... thanks. Wnt (talk) 16:20, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- This usage of "color inversion" is a very useful and standard concept; but it's based on a perceptually-constructed colorspace (...an abstract mathematical model describing the way colors can be represented...). Thus, this usage of color "inversion" is not related to any fundamental physical properties of light. Nimur (talk) 21:05, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Ack, I knew that... thanks. Wnt (talk) 16:20, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, the highest value is 255. Icek (talk) 09:24, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- I think the definition is approximately the same as a photographic negative: in computer terms, you just subtract the color from the highest value. So for 256 colors, inversion from (X,Y,Z) is (256-X, 256-Y, 256-Z). Am I wrong? Wnt (talk) 23:41, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

What is this little white bug?

I was photographing insects in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia this past weekend when I noticed this little one. I have never seen anything like it, I'm guessing it is a nymph of some sort? It looks like a miniature, white dinosaur.

http://keeganm.com/gallery/2011_06_26/images/large/DSC_3345.jpg

Thanks! Keegstr (talk) 13:33, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- An Aphid of some sort? There are dozens and dozens of species of aphids, perhaps one of them? --Jayron32 14:28, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Cool photo! It is somewhat uncommon to see a singular wingless aphid (because they rapidly form clonal aggregations), and aphids are usually seen with their stylets inserted into stems or leaves. What kind of plant was it on? Did it run away when disturbed, or stay put? I think you are correct that it is a nymph. I'll keep looking... SemanticMantis (talk) 14:58, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Awesome. If you think it would be beneficial to post the image to a specific wiki article, I will gladly do so if you can tell me what to title it and where to put it. Here is the full photo (above is a 100% crop) I am unsure of the flower type. http://keeganm.com/tmp/DSC_3345-2.jpg Keegstr (talk) 15:08, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Thanks. We absolutely should have the image on the commons, and ideally in one or more article. But I guess we might wait for an identification before uploading it. My vote is that it's minizilla. Excellent photo; kudos. --Tagishsimon (talk) 15:10, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Current best guess: a planthopper nymph_(biology). See a somewhat similar beast here [4]. Note that your photo clearly shows 'thickened, three segmented antennae'. Note also that homoptera has crazy variation in it's defensive/camouflage structures. See extreme/surreal examples here: [5]. If nobody here corroborates my guess or poses a good alternative, you could ask at bugguide.net or whatsthatbug.com. SemanticMantis (talk) 15:31, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- I have posted to bugguide, here: http://bugguide.net/node/view/537384 . I will update this if there is any information from that end. Keegstr (talk) 15:47, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Someone at bugguide.net suggested it might be an Ambush Bug, but was uncertain. Keegstr (talk) 17:01, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Matches well with this Ambush Bug - http://bugguide.net/node/view/471034 --Tagishsimon (talk) 17:10, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Judging only by appearance, that looks like the closest match yet. Bus stop (talk) 17:20, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Is this enough information to post on the wiki article? Or should we wait for more substantial evidence? A google search indicates others call this an ambush bug nymph as well.Keegstr (talk) 17:31, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- I would definitely say we should wait for some more substantial information as to that creature's identity. If we are wrong we would spread misinformation. It is a gem, by the way. Good work photographing it. Bus stop (talk) 17:36, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- I'm changing my vote to ambush bug :). My first thought was actually the related assassin bug (due to the mouth), but I couldn't find any with pale nymphs. Note that your photograph agrees with the other ambush bugs not only in 'look' or appearance, but in specific morphological features such as the large fore-femur, and sturdy, piercing mouthparts which are kept curled under the thorax. Even though I said three-segmented antennae above, on closer inspection I think I see four. Also, a flower is exactly where we would expect to find these critters. I'd say follow wp:bb and add it to our page ambush bug. SemanticMantis (talk) 19:30, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Matches well with this Ambush Bug - http://bugguide.net/node/view/471034 --Tagishsimon (talk) 17:10, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Someone at bugguide.net suggested it might be an Ambush Bug, but was uncertain. Keegstr (talk) 17:01, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

Photons exchange inside atoms

Hi friends, I have a question about electric charge interaction inside atom. I have read that in standard model, always two electric charge interact, they do this echanging photons. But in atomic model we have see that we only have photons emission or absortion when electrons change of energy level (K to M,N, P or vice versa). My question is: Considering a stable atom without any energy deviation, only with electron around nucleous, is there any photons changing among electorns and protons ? Also, inside nucleus, is there any photons exchanging when we have interactions among two or more protons inside nucleus ?

Thanks for help, — Preceding unsigned comment added by Futurengineer (talk • contribs) 16:30, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, in quantum electrodynamics, any time there is an electromagnetic force, there are photons to mediate it -- but they are virtual particles, not visible except via their effects. There are also virtual photons exchanged between protons in the nucleus. Looie496 (talk) 16:38, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

How do pigs groom or clean themselves?

I understand that cats groom or clean themselves with their tongues. How do pigs groom or clean themselves? (I am 3 years old, and my father typed this question.)--82.31.133.165 (talk) 21:22, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- According to Van Putten, G. (February 1989). "The pig: A model for discussing animal behaviour and welfare". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 22 (2): 115–128., pigs groom themselves by taking a mud bath, letting the mud dry, and then rubbing off the mud. The parts that they can't reach are groomed by subordinate pigs, while the dominant pig is laying on its side (See here). ~ Mesoderm (talk) 21:32, 30 June 2011 (UTC)

- Who grooms subordinate pigs?--Shantavira|feed me 07:30, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- This all happens on a totem pole ? Impressive. Sean.hoyland - talk 08:11, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Please, not while one's eating ;) --Ouro (blah blah) 10:04, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- A pig may lie but only a hen can lay. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 15:53, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Please, not while one's eating ;) --Ouro (blah blah) 10:04, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- This all happens on a totem pole ? Impressive. Sean.hoyland - talk 08:11, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Can anyone translate "Who will groom the subordinate pigs?" into Latin? I think it will make a good motto. 86.181.169.137 (talk) 21:00, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

Anyway.... congratulations, you might be the youngest enquirer on these pages ever - unless anyone else knows different! Alansplodge (talk) 15:11, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

July 1

Fungus that looks like rags

I have a fungus in my backyard that looks like old rags. It tends to grow near a tree. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 74.229.224.168 (talk) 00:09, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- I'm surprised it doesn't grow in the garage next to the rag pile. :-) But, seriously, we really need a pic to identify it. StuRat (talk) 00:20, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Does it look anything like this?

Black hole

If matter is never destroyed (just changing form), once matter enters a black hole, and then the black hole evaporates, what happens to the matter? Albacore (talk) 00:48, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- The matter is converted into Hawking Radiation. But from Mass we learn that "all types of energy have an associated mass" and it is mass, not specific matter, which is preserved. --Tagishsimon (talk) 01:05, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- The answer might be different if you use "matter" in the narrow sense of "opposed to antimatter". The notion of using a microscopic black hole to catalyze the conversion of matter to energy (i.e. equal parts matter and antimatter) is most appealing, though certainly not safe, yet I've heard people doubt the possibility. Wnt (talk) 16:22, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Your comment above is unclear. would you mind clarifying it? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 71.101.45.227 (talk) 20:44, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

Name of our Black Hole

What is the name of the Black Hole at the center of our galaxy and how long will it take before our sun and the Earth spiral in are consumed? --DeeperQA (talk) 10:59, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- First question: Sagittarius A* --George100 (talk) 11:05, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Black holes do, however, tend to sink towards the centers of galaxies. This article claims there may be 10,000 black holes swarming around the central supermassive one:

When such a massive object flies by one of the greater number of less massive stars, the lighter body gains speed while the heavier body loses speed. Several such two-body interactions make heavier bodies fall towards the galactic centre, while lightweight stars are ejected towards the outer regions of the galaxy. - "Signs that black holes swarm at galaxy centre"

- It's not clear whether these multiple black holes eventually merge into the central one. --George100 (talk) 20:13, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, and even if they were more massive, that alone isn't a reason why they can't have a stable orbit about the super-massive black hole at the center of the galaxy. StuRat (talk) 08:20, 3 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, although they would tend to settle towards the centre of the galaxy in the way the source George quotes describes. They would be in a stable orbit still, just a close one. If they get close enough, though, gravitational radiation will cause their orbits to decay (as it does all orbits, but usually too slowly to be significant). --Tango (talk) 13:20, 3 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, and even if they were more massive, that alone isn't a reason why they can't have a stable orbit about the super-massive black hole at the center of the galaxy. StuRat (talk) 08:20, 3 July 2011 (UTC)

- This makes me wonder about the growth rate of a typical stellar black hole. Since it's a stellar mass within a tiny radius, it would continually consume the interstellar medium, or if it's paired with a star it would consume a significant part of that mass. Still it seems that it would take considerable time for one to grow substantially larger than its original size. --George100 (talk) 12:27, 4 July 2011 (UTC)

Atomic weight notation

What is the meaning of the numeral in parentheses following an atomic weight? In the List of elements article, each weight is followed by a second number, such as Hydrogen - 1.00794 is followed by (7), or Lithium 6.941(2). I can't find an explanation in the Atomic weight article either. --George100 (talk) 11:03, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- I've seen that in tables of physical constants before. I've always assumed that it means the digits in parentheses are uncertain. --173.49.9.250 (talk) 11:23, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- 173 has it correct. When you see a number listed with the last digit in parentheses, that is the digit where the uncertainty occurs. Ideally, somewhere in the same publication (perhaps in the introduction or the addenda, or maybe as a footnote or something like that) is an explanation "Values have an uncertainty of +/- x%" and this uncertainty means that the last quoted digit is kinda "fuzzy". This is expecially true for quoted values of atomic weight, since these values are usually (unless otherwise noted) values for average atomic weight of all known isotopes of the element, weighted for their natural abundance. Since there is some uncertainty in natural abundance levels, there is going to be some uncertainty in the average atomic mass, via Propagation of uncertainty. --Jayron32 12:02, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- See Uncertainty#Measurements and http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Info/Constants/definitions.html. 0.123(45) is a shorter way of writing 0.123 ± 0.045. The parenthesized digits aren't uncertain, they're the uncertainty. -- BenRG (talk) 17:58, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

Just to emphasize, BenRG's explanation is correct, not the first two (though they were sort of correct). The digits in parenthesis denote the uncertainty in the previous digits, so 0.04336(3) is equivalent to 0.04336 ± 0.00003 and 2.1540(35) is equivalent to 2.1540 ± 0.0035. Just saying that something is uncertain is pointless unless you say how uncertain it is.-RunningOnBrains(talk) 20:06, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

Space Time

We know that Space time grid can be bend and folded.But I read somewhere that it can't be cut into pieces.Is it true??? Thank You — Preceding unsigned comment added by 117.197.254.243 (talk) 13:56, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- The first question I would ask would be "what could possibly separate the pieces?" Dbfirs 17:47, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- General relativity requires spacetime to be smooth, meaning that if you look at it at a high enough magnification, it looks like uniform flat spacetime extending in all directions. A cut in spacetime wouldn't qualify, because no matter how far you zoom in, that cut is still there. But general relativity can't be the end of the story. It seems possible (likely, even) that "cuts" of some sort will be permitted in quantum gravity. -- BenRG (talk) 18:01, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- One possibility is that black holes punch a hole in space time, perhaps leading to another point, such as the Big Bang, through a wormhole. This isn't quite the same as cutting space-time into pieces, though. StuRat (talk) 18:11, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Here's a hypothetical about a wormhole:[6] ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 20:49, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- I'm not extremely fluent in cosmology, but cosmic strings appear to be kind of like a 1-dimensional rip (or at least a "crease") in spacetime. There is no evidence that they exist, however, and thus are just theoretical at this point. -RunningOnBrains(talk) 20:32, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

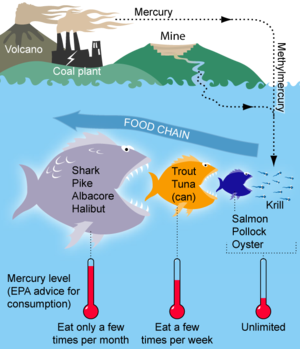

Mercury in sea fish

How can some sea fish have high content of mercury? Any mercury which end in the sea or falls into a river would get diluded when it reaches the sea, even inside some organism. — Preceding unsigned comment added by Wikiweek (talk • contribs) 18:59, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- See Minamata disease in which mercury poisoning resulted from methylmercury pollution in Minamata Bay that affected both fish and shellfish. The concentration of mercury in the fish increased slowly by bioaccumulation, eventually reaching levels that were toxic. Mikenorton (talk) 19:08, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Fresh water fish is more contaminated than deep sea fish. Predatory fish and sea mammals - such as shark, swordfish, tuna and whale - are more contaminated than smaller fishes. Mercury accumulates up the food chain in a fish-eat-fish ocean. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 88.14.198.240 (talk) 19:11, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- There is little mercury in small young fish such as sardines. It is the large fish that live longer that accumulate more mercury. I think the increased levels of mercury in the sea was due to mercury being released into the air when coal was burnt, but I could be wrong. 92.24.141.227 (talk) 21:28, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- The answer is Biomagnification. The water may dilute the mercury, but life can concentrate it just as fast.

- I've taken the liberty of adding the lovely illustration from the "Mercury in fish" article. APL (talk) 10:39, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- What about those lifeforms that eat the carcasses of large fishes? If none of the lifeforms excretes enough mercury so that in their body there is a lower mercury concentration than in their food, one would expect (in a closed ecology) that eventually, in equilibrium, the mercury concentration is the same in all lifeforms. There might be some lifeforms which accumulate more mercury at a certain concentration, but either the accumulation stops at a certain concentration or they continue to accumulate until they go extinct from mercury poisoning.

- So, the question is, is this higher mercury concentration in larger fishes a transitory phenomenon (under the assumption that the ecosystem is closed and "life" accumulates mercury that is inevitable)? I rather think there are at least bacteria which can excrete mercury efficiently from their cells (otherwise, wouldn't the accumulation have already happened over geological timescales? On the other hand, there is also sedimentation of organic material over geological timescales).

- So, the real question is: Which organisms accumulate mercury, and which don't?

- Icek (talk) 12:29, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

Maggots in my wheelie bin

Today while putting out my wheelie bin for its fortnightly collection, I was surprised to see a large mass of maggots writhing on top of the rubbish, in the juice from the remains of a mango. I do not waste food and care about hygene. How could the maggots have got there? Can they really grow from fly's eggs within 14 days? Could they have smelt the ripe mago and wriggled towards it? I had assumed they only liked animal material, not vegetable even if sweet. 92.24.141.227 (talk) 21:39, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- It takes less than a day for the eggs of a blowfly to hatch, so I don't think that this is a surprising observation. Mikenorton (talk) 21:53, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Have you ever wondered why a fruit fly are so named. For whatever food you eat there is some fly or insect that loves it too. Getting under your wheeliebin lid after detecting a mango would be routine for any fly that likes fruit. It would pop its eggs on or near the fruit and bingo. Richard Avery (talk) 22:02, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- According to Aristotle, it was a readily observable truth that aphids arise from the dew which falls on plants, flies from putrid matter, mice from dirty hay, crocodiles from rotting logs at the bottom of bodies of water, and so on. But in 1668, Francesco Redi challenged the idea that maggots arose spontaneously from rotting meat. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 22:39, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- You might want to use the method I use, mainly to control the stench. For things which will decay and stink before trash day, I employ a slop jar. This is typically an old coffee can. Since it seals tightly, no stink gets out and no flies get in. I have a ready supply, but you could reuse them by dumping the contents out and rinsing them on trash day, if you don't have enough. Alternatives to the slop jar include using a garbage disposal or flushing down the toilet. StuRat (talk) 23:37, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- If you are concerned about flies and other vermin attacking the contents of your wheelie bin, there are steps you can take to prevent it. If you have food waste collected on separate weeks to the other waste (as we do), you can get compostable plastic bags from your supermarket. Use these to wrap your food waste in. If you really can't put that bag into your all-purpose bin, you could put it into the freezer until the day before your food waste bin is collected then put it out in the bin. --TammyMoet (talk) 07:56, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- Putting rotting vegetation in an air-tight container is a good recipe for anaerobic decomposition, which will produce enough methane to blow the top right off. A better solution is vermiculture, which is nearly odour- and maintenance-free and comes with the side benefit of producing rich, fertile soil for your garden or planters. SmashTheState (talk) 00:06, 6 July 2011 (UTC)

using the "scientific method"

I realize there is no ONE true "scientific method". So instead, I am interested in a range of possible approaches or methodologies I could follow to arrive at a measurement of the approximate percentage of people worldwide who are actually robots. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 188.29.154.125 (talk) 21:51, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Ha! One place to start is by unambiguously defining what you mean by 'people', or more to the point, what constitutes a 'person'. This is no easy task! Google /problem of personhood/ to get an indication of the political, philosophical, and scientific issues involved. SemanticMantis (talk) 22:26, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- (ec)While we're at it, we need a clear, unambiguous definition of robot. Once you have clear definitions, you should then set out a testing method to determine whether a subject meets the definition. Finally, you may want to read about statistical sampling to learn how many tests you should conduct in order to achieve a certain level of confidence in a conclusion about the large population. You will need to test somewhere between 0% and 100% of the population. Nimur (talk) 22:41, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- I think you're not understanding my question. It relates to the scientific method itself. If there were no robots or if there were a few, I would never find out the difference by the "statistical sampling" method you suggest. I need harder, realer science. And I need it yesterday, not tomorrow. As a compromise I will settle for later today.--188.29.154.125 (talk) 22:50, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- Obviously I mean citizens. "Natural people" as far as the government, and other people, are concerned. Except they're really robots. --188.29.154.125 (talk) 22:40, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- (ec)While we're at it, we need a clear, unambiguous definition of robot. Once you have clear definitions, you should then set out a testing method to determine whether a subject meets the definition. Finally, you may want to read about statistical sampling to learn how many tests you should conduct in order to achieve a certain level of confidence in a conclusion about the large population. You will need to test somewhere between 0% and 100% of the population. Nimur (talk) 22:41, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

The troll monicker is completely unwarranted. Why do I get it? Because it's "obvious" that "no one is a robot in all the nearly 7 billion people in the world". I would agree with that statement. However, "obvious" does not science make. This is an inherent question about the scientific method itself, with Robots just serving as an example of something that would require a paradigm shift. How does science deal with these situations? --188.29.154.125 (talk) 22:52, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- You could deal with the question if 'x does not exist in the group A' statistically. Test a reasonable number of members, and you can draw a conclusion (with a confidence interval). Quest09 (talk) 23:09, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

You guys are not understanding the question. I've removed the rude "troll" sign. Let me explain what some obvious problems are with the answers so far: How many 'people' have been outed world-wide as being really robots, to date? 0. Precisely 0. That means that out of 7,000,000 "people" not a single one has been shown to be a robot instead. Now you are proposing that I "test" people, to see if they're robots. But why would my test be any better than the fact that these "people" are tested every day by every single person they meet? Or, if these "people" don't meet anyone, then why would I be in a position to get to test them? I have other thinking, as well, about the scientific method. Take occam's razor. In order for there to be robots that have successfully passed for humans until my "test", that means that the true cutting-edge state of robotics must be well ahead the academic level. But what mechanism would put the true state of robotics so far ahead of the academic state? Occam's razor implies that the reason not one of the 7 billion "people" on Earth has been outed as being really a robot, is that none of them really are. But the question arises: is this reasoning correct? After all, there were millennia during which the heavenly spheres weren't outed as being "nothing at all", not existing period. It seems that I may have misapplied Occam's razor a moment ago, then, doesn't it? There is more. What if the robots are a conspiracy? Why would I be in any better a position than anyone else to find this out? I am asking a basic question about the world, just a scientist does who posits, say, in AD 300, that the moon orbits the Earth, the Earth and planets orbits the Sun, the sun and its solar-system interorbits with many other suns, distant enough to be stars. Such a hypothesis, in that day and age, would have been about as likely as the existence today of robots masquerading as people. Yet you could test for the former. How do you test for the latter? I am trying to understand the BASIC underlying philosophy of scientific progress, and you people are saying "dude, just take a random sample and see if they're robots", as though that were a meaningful answer. How is it meaningful: I know with certainty 1 that if I "take a random sample and see if they're robots" the answer will be "0 of my sample was". But I don't have the chance to sample just anyone out of the world's 7b people. I can sample whoever is around me (geolocate my IP if you want)... going from this to estimating whether there are robots walking the earth seems to me to be a stretch at best. I hope I have now clarified the depth to which a real answer must answer. --188.29.154.125 (talk) 23:37, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

There is, in fact, one true scientific method: Hypothesis are proven by observed evidence. Usually that evidence is from controlled experimentation. The problem is in social science research (a field I've worked in) you can't conduct a controlled experiment. The best you could do in this case would be to survey a truly statistically random sample of the population. 98.209.39.71 (talk) 23:57, 1 July 2011 (UTC)

- I don't get why you call this the "social sciences". I would think this is an extremely hard scientific fact. Either there are "people" with normal human relationships but who are really robots/androids/etc, not flesh and blood borne of the womb of a human mother, or there are not. How do I determine this? "Survey some 'people'" cannot possibly work as a methodology - what can? --188.29.154.125 (talk) 00:45, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

One of the basic principles of the scientific method is that it is not possible to prove a universal -- only to disprove one. "No humans are robots" is a universal. Therefore it is not provable. Looie496 (talk) 00:48, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- One of the currently popular summaries of what is and is not science revolves around the concept of falsifiability. To be science, it is argued, something must be falsifiable. "There could be (at least hypothetically) a person (somewhere) who is actually a robot" is not falsifiable (there isn't any test or experiment one could do to disprove the statement), and as such would not be counted as a scientific hypothesis in that view. "No person in this particular room is a robot" is falsifiable (one can test every person in the room for being a robot), and would at least be considered for the status of a scientific hypothesis. Note, however, if you get nebulous/tricky on the definition of being a robot (e.g. "well, the robots I'm thinking of look and act exactly like humans, and any test you do on them couldn't tell them apart from humans"), then "No person in this particular room is a robot" can cease to be falsifiable (as there is no test you can do to disprove it), and thus ceases to be counted as a possible scientific hypothesis. -- 140.142.20.229 (talk) 01:18, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- See Russell's teapot. Gandalf61 (talk) 08:18, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- I think that to scientifically test for specifically robots, you'd need a working theory on the kind of robots they are and the methods they're using to hide from humanity.

- Obviously, you wouldn't need that theory to just stumble across a robot during the course of some other investigation, but if you're specifically starting with the theory that some alleged humans are robots in disguise, and then attempting to prove or refute that theory, you're going to have to define it better first.

- However, if you're assuming typical androids with electronic and mechanical mechanisms inside, and no biological componants, and no interior componants that are disguised as biological componants, then it seems like the way to go would be to attempt to draw blood from from a random sampling of mankind, and do the usual statistical math to estimate the min/max percentages.

- You might also be able to do statistical analysis on published data. If you take it as given that a robot destroyed in a traffic accident would be discovered as a robot, and that no robots have ever been discovered in that manner, then you could do some number crunching to figure out the maximum percentage of alleged humans that could potentially be robots before it becomes statistically ridiculous that none have ever been discovered after a traffic accident. APL (talk) 10:31, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

July 2

Giving male hormones to transexual (biological) women

Would they grow a beard and change the voice? — Preceding unsigned comment added by Quest09 (talk • contribs)

- Yes and yes. See Hormone replacement therapy (female-to-male) for more detail. --Carnildo (talk)

- A note that might make it easier to search for future results: it's usual practice, among the people most likely to be discussing this in a scientific way, to refer to a transgender person born with a biologically female body as a transexual, transgender, or even just 'trans' man, based on the view that they are 'really' a man with a woman's body, rather than a 'really' a woman who 'thinks' she's a man. Not only is this less hurtful to trans people (it doesn't involve assuming they are mistaken), understanding this will make it much easier to follow any discussions you see. 86.164.27.124 (talk) 08:06, 4 July 2011 (UTC)

Light in a tube?

Suppose I have a tube with higly reflective inner walls. If I placed a spotlight in it, aimed directly at opening at one end of tube, would light coming out from it would be any diffrent (like diffrent brighness, diffrent form of light beam or anything) than, if I had just the spotlight? 46.109.116.140 (talk) 02:01, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- For one thing, it would take longer to get to the other side, as light doesn't travel with infinite velocity. I wonder why no one ever thought of slowing down light with an intricate series of mirrors such that, for example, it has to bounce exactly a million times to reach the observer, which is the same position you flick the switch, just a certain "distance" (as travelled by the light through all those mirrors) away? Then you could measure its speed much more easily... --188.28.55.61 (talk) 02:08, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- Ohhh... asume also that we are talking at human scale, where light seems to appear inatantly etc. 46.109.116.140 (talk) 02:31, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- (ec) That's sort of the idea of Speed of light#Cavity resonance. Though in cavity resonance it doesn't have to be the exact same photon bouncing back and forth over and over; the point is that in general the photons bounce once a wavelength. But also note that the speed of light cannot be measured! Because the meter is now defined as a unit of time, oddly enough. You can see how accurate the length of your yardstick really is, in terms of the time light takes to propagate. (User:Brews ohare would love this thread...) Wnt (talk) 02:33, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- The meter is not defined as a unit of time. It is defined as a unit of length, namely, the length traveled by light in a vacuum in 1/299,792,458 second. So it is defined in terms of time, but not as a unit of time. —Bkell (talk) 13:21, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- "The speed of light cannot be measured"? That would come as a surprise to Michelson. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 14:57, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- The Michelson–Morley experiment didn't actually measure the speed of light. What it did was measure was if there was any speed of light difference between two perpendicular directions (with the direction of Earth's travel and perpendicular to it, for example) by looking at the change in an interference pattern as an apparatus was rotated. However, I believe the point was that although if you have an independent time unit and length unit you can measure the speed of light (see Speed of light#History), the meter (and thus the inch/foot/yard) is currently defined based on the speed of light. So while you could set up a measurement experiment for the speed of light, the answer is a foregone conclusion, and coming up with an answer of even 299,792.4581 m/s (versus 299,792.458 m/s) means that either your distance measurement or your time measurement wasn't accurate enough. -- 174.31.222.225 (talk) 15:14, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- "The speed of light cannot be measured"? That would come as a surprise to Michelson. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 14:57, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- The meter is not defined as a unit of time. It is defined as a unit of length, namely, the length traveled by light in a vacuum in 1/299,792,458 second. So it is defined in terms of time, but not as a unit of time. —Bkell (talk) 13:21, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- You might want to look at Light tube and follow some of the links for a real-life example. --TammyMoet (talk) 07:49, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- See also optical fiber cable, which is essentially the same thing.--Shantavira|feed me 08:20, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- True, the Michelson–Morley experiment did not measure the speed of light. However, Michelson did experiments to measure it. E.g., this paper from 1927. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1927CMWCI.329....1M

- Michelson's result was 0.00118 of one percent higher than the currently accepted speed. This is because the speed of light has slowed due to atmospheric pollution. :::CBHA (talk) 19:53, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- Not to nitpick, but I highly doubt that pollution is the reason for his experimental error, if it even is error: the speed of light in the atmosphere will depend on many things, most important of which are temperature and humidity. While pollution will change the speed of light in the atmosphere very slightly, pollution varies from place to place, and in many areas has improved greatly since the 1920s (see Great Smog for an extreme example).-RunningOnBrains(talk) 20:44, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- (edit conflict)An amusing reason for the error, but the currently accepted speed is that measured in free space. Michelson's result in air should have been slightly less than the current value. Dbfirs 20:46, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- Really? I ask a practical basic optics question and you start discussing hardly relevant theoretical issue and suggest I explore similar situations on my own? May I argue that the skylight in question is usualy light by an external light source coming in at angle, as a result it might be diffrent as spotlight placed at end of tube as the light source would be inside the tube and spotlights usualy have a curved mirror to aim the light. And according to the article the medium they are made of determines how the lith travels, it is a wire not a hollow tube with air 46.109.116.140 (talk) 02:27, 3 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, sorry, we have gone way off topic. The light coming out of your spotlight tube will be almost identical to the light without the tube. Light from any spotlight (coherent lasers excluded) will have considerable spread, so some light will bounce off the inner reflective surfaces of the tube, but the effect, at best, will be similar to just moving the spotlight forward by the length of the tube. A large parabolic reflector and a plain light source at the focus might be more effective at "aiming" the light to producing a sharp beam, but there will always be significant spread of the light beam. Dbfirs 06:36, 3 July 2011 (UTC)

- Just as I thought :) Thanks 46.109.116.140 (talk) 03:14, 4 July 2011 (UTC)

- Yes, sorry, we have gone way off topic. The light coming out of your spotlight tube will be almost identical to the light without the tube. Light from any spotlight (coherent lasers excluded) will have considerable spread, so some light will bounce off the inner reflective surfaces of the tube, but the effect, at best, will be similar to just moving the spotlight forward by the length of the tube. A large parabolic reflector and a plain light source at the focus might be more effective at "aiming" the light to producing a sharp beam, but there will always be significant spread of the light beam. Dbfirs 06:36, 3 July 2011 (UTC)

Tree with purple leaves

Here's a picture I took. The leaves are always purple. Is there something other than chlorophyll in the cells of the leaves of this tree? Why are the leaves purple? Thanks. Peter Michner (talk) 15:34, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- A) Yes, there are many things other than chlorophyll which give color to leaves. For example, there are the red leaves of the poinsettia.

- B) Accessory pigments, which work with chlorophyll, also come in colors other than the common green. StuRat (talk) 15:51, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- This looks more or less anthocyanin (eggplant) colored, but I won't pretend to recognize the tree, so take that with a grain of salt. But I see that article has a photo of some somewhat similar looking trees. Wnt (talk) 20:22, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- Not easy to be sure of an i/d from this fuzzy pic, but it seems to have palmate leaves, so my guess is a Norway maple variety like this one. There are a large number of broad-leaved tree varities with purple leaves; they are all cultivars and do not appear naturally. BTW, I think the red parts of a poinsettia are bracts rather than true leaves, but your point stands anyway. Alansplodge (talk) 20:47, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

- D'oh! I've just looked at the Bract article and it says that they are "a modified or specialized leaf", so it seems I was splitting hairs. We live and learn. Alansplodge (talk) 20:54, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

ULAS J1120+0641's distance from us... too far?

This is about the farthest quasar that has been discovered up to date.

According to the Wikipedia article, the Quasar is at a comoving distance of 28.85 billion light-years from Earth. Then it states that this light has been traveling for 13 billion years. I suppose that the discrepancy is due to the expansion, but, how do they know the distance? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 186.29.119.171 (talk) 15:50, 2 July 2011 (UTC)

Training in the heat

Well basically my question is if it is a good idea to train in the heat, does it make your training more effective? Less? Is it just a hassle with no rewards? Bastard Soap (talk) 18:14, 2 July 2011 (UTC)