Social history of viruses

The social history of viruses describes the influence of viruses and viral infections on human history. Viruses are the most abundant biological entity on Earth and they have infected plants and animals, including humans, for millions of years. Epidemics caused by viruses began when human behaviour changed during the Neolithic period. Previously hunter-gatherers, humans developed more densely populated agricultural communities, which allowed viruses to spread rapidly and subsequently to become endemic.

Despite having no idea that viruses existed, Louis Pasteur and Edward Jenner were the first to develop vaccines to protect against viral infections. The sizes and shapes of viruses remained unknown until the invention of the electron microscope in the 1930s, when the science of virology gained momentum.

In the 20th century many diseases both old and new were found to be caused by viruses. Although scientific interest in them arose because of the diseases they cause, most viruses are beneficial. They have driven evolution by transferring genes across species, play important roles in ecosystems, and are essential to life.

In prehistory

Over the past 50,000–100,000 years, as modern humans dispersed throughout the world, new infectious diseases emerged, including those caused by viruses.[1] Smallpox, which is the most lethal and devastating viral infection in history, first emerged among agricultural communities in India about eleven thousand years ago.[2] The virus, which only infected humans, probably descended from the poxviruses of rodents.[3] Humans probably came into contact with these rodents, and some people became infected by the viruses they carried. When viruses cross this so-called "species barrier", their effects can be severe,[4] and humans may have had little natural resistance. Contemporary humans lived in small communities, and those who succumbed to infection either died or developed immunity. This acquired immunity is only passed down to offspring temporarily, by antibodies in breast milk and other antibodies that cross the placenta from the mother's blood to the unborn child's. Therefore, sporadic outbreaks probably occurred in each generation. In about 9000 BC, when many people began to settle on the fertile flood plains of the River Nile, the population became dense enough for the virus to maintain a constant presence due to the high concentration of susceptible people.[5] Other epidemics of viral diseases, such as mumps, rubella, polio, which depend on large concentrations of people, also first occurred at this time.[6]

The Neolithic age, which began in the Middle East in about 9500 BC, was a time when humans became farmers. This agricultural revolution embraced the development of monoculture and presented an opportunity for the rapid spread of several species of plant viruses.[7] The divergence and spread of sobemoviruses – southern bean mosaic virus – date from this time.[8] The spread of the potyviruses of potatoes, and other fruits and vegetables, began about 6,600 years ago.[7]

About 10,000 years ago the humans who inhabited the lands around the Mediterranean basin began to domesticate wild animals. Pigs, cattle, goats, sheep, horses, camels, cats and dogs were all kept and bred in captivity.[9] These animals would have brought their viruses with them. The transmission of viruses from animals to humans can occur, but such zoonotic infections are rare and subsequent human-to-human transmission is even rarer, although there are notable exceptions such as influenza. Most viruses are species specific and would have posed no threat to humans.[10] But as humans became more dependent on domesticated animals, any outbreaks of disease among their livestock – in animals these are called epizootics – could have devastating consequences.[11]

Other, more ancient, viruses are less of a threat. Humans have lived with herpes virus infections since humans first came into being. These viruses first infected the ancestors of modern humans over 80 million years ago.[12] Humans have developed a tolerance to these viruses, and most are infected with at least one species.[13] Records of these milder virus infections are understandably rare but it is likely that early hominids suffered from colds, influenza and diarrhoea caused by viruses just as humans do today. More recently evolved viruses cause epidemics and pandemics – and it is these that history records.[12]

In antiquity

Among the earliest records of a viral infection is an Egyptian stele thought to depict an Egyptian priest from the 18th Dynasty (1580–1350 BC) with a foot drop deformity characteristic of a poliovirus infection.[14] The mummy of Siptah – a ruler during the 19th Dynasty – shows signs of poliomyelitis, and that of Ramesses V and some other Egyptian mummies buried over 3000 years ago show evidence of smallpox.[15] There was an epidemic of smallpox in Athens in 430 BC. A quarter of the Athenian army died from the infection along with many of the city's civilians.[16]

Measles is an old disease, but it was not until the 10th century that the Persian physician Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (865–925) (known as "Rhazes") first identified it.[17] Rhazes used the Arabic name "hasbah" for measles, but it has had many other names including "rubeola" from the Latin word rubeus, which means red, and "morbilli", which means "small plague".[18]

The close similarities between measles virus, canine distemper virus, and rinderpest virus have given rise to speculation that measles was first transmitted to humans from domesticated dogs or cattle.[19] The measles virus appears to have fully diverged from the then-widespread rinderpest virus by the 12th century.[20] The earliest likely origin is within the seventh century; there is some linguistic evidence for this earlier origin.[21][22]

A measles infection confers lifelong immunity. Therefore the virus requires a high population density to become endemic and this probably did not occur in the Neolithic age.[17] (In more recent times, measles has become extirpated on remote islands with populations of fewer than 500,000 people.[19]) Following the emergence of the virus in the Middle East, it reached India by 2500 BC.[23] Measles was so common in children at the time that it was not recognised as a disease. In Egyptian hieroglyphs it was described as a normal stage of human development.[24]

One of the earliest descriptions of a virus-infected plant can be found in a poem written by the Japanese Empress Kōken (718–770), in which she describes a plant in summer with yellowing leaves. The plant, later identified as Eupatorium lindleyanum, is often infected with tomato yellow leaf curl virus.[25]

Middle Ages

The rapidly growing population of Europe and the rising concentrations of people in its towns and cities became a fertile ground for many infectious and contagious diseases, of which the Black Death – a bacterial infection – is probably the most notorious.[26] Except for smallpox and influenza, documented outbreaks of infections now known to be caused by viruses were rare. Rabies, a disease that had been recognised for over 4000 years,[27] was rife in Europe, and continued to be so until the development of a vaccine by Louis Pasteur in 1886.[28] The average life expectancy in Europe during the Middle Ages was 35 years; 60% of children died before the age of 16, many of them during their first 6 years of life. Among the plethora of diseases that caused childhood death were measles, influenza and smallpox.[29] The Crusades and the Muslim conquests aided the spread of smallpox, which was the cause of frequent epidemics in Europe following its introduction to the continent between the fifth and seventh centuries.[30][31]

Measles was endemic throughout the highly populated countries of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.[32] In England the disease, then called "mezils", was first described in the 13th century, and was probably one of the 49 plagues that occurred between 526 and 1087.[23]

Rinderpest, which is caused by a virus closely related to measles virus, is a disease of cattle known since Roman times.[33] The disease, which originated in Asia, was first brought to Europe by the invading Huns in 370. Later invasions of Mongols, led by Genghis Khan and his army, started pandemics in Europe in 1222, 1233 and 1238. The infection subsequently reached England following the importation of cattle from the continent.[34] At the time rinderpest was a devastating disease with a mortality rate of 80–90%. The resulting loss of cattle caused famine.[34]

Early modern period

A short time after Henry Tudor's victory at the Battle of Bosworth on 22 August 1485, his army suddenly went down with "the English sweat", which contemporary observers described as something new.[35] An epidemic hit London in the hot summer of 1508. Victims died within a day, and there were deaths throughout the city. The streets were deserted apart from carts transporting bodies, and King Henry declared the city off limits except for physicians and apothecaries.[36] The disease was probably influenza,[37] or another similar viral infection,[38] but records from the time when medicine was not a science can be unreliable.[39] The language used to describe diseases in these sources is often vague and colloquial. Examples include "plagues of mice", "changes in the direction of the wind" and the "influence of comets". As medicine became a science, the descriptions of disease became less vague and records became more reliable.[40] Although medicine could do little at the time to alleviate the suffering of the victims of infection, measures to control the spread of diseases were used. Restrictions on trade and travel were implemented, stricken families were isolated from their communities, buildings were fumigated and livestock killed.[41]

References to influenza infections date from the late 15th and early 16th centuries,[42] but infections almost certainly occurred long before then.[43] In 1173, an epidemic occurred that was possibly the first in Europe, and in 1493, an outbreak of what is now thought to be swine influenza, struck Native Americans in Hispaniola. There is some evidence to suggest that source of the infection was pigs on Columbus's ships.[44] The first pandemic that was reliably recorded began in July 1580, and swept across Europe, Africa, and Asia.[45] The mortality rate was high – 8,000 victims died in Rome.[46] The next three pandemics occurred in the 18th century; the one that took place during 1781–2 was probably the most devastating in history.[47] The pandemic began in November 1781 in China and reached Moscow in December.[46] In February 1782 it hit St. Petersburg and by May it had reached Denmark.[48] Within six weeks, three-quarters of the British population were infected and the pandemic soon spread to the Americas.[49]

The Americas and Australia remained free of measles and smallpox until the arrival of European colonists between the 15th and 18th centuries.[1] Along with measles and influenza, smallpox was taken to the Americas by the Spanish.[50] Smallpox was endemic in Spain, having been introduced by the Moors from Africa.[51] In 1519, an epidemic of smallpox broke out in the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan in Mexico. This was started by the army of Pánfilo de Narváez, who followed Hernán Cortés from Cuba, and had an African slave suffering from smallpox aboard his ship.[51] When the Spanish finally entered the capital in the summer of 1521, they saw it strewn with the bodies of smallpox victims.[52] The epidemic, and those that followed during 1545–1548 and 1576–1581, eventually killed more than half of the native population.[53] Most of the Spanish were immune; with his army of fewer than 900 men it would not have been possible for Cortés to defeat the Aztecs and conquer Mexico without the help of smallpox.[54] Many Native American populations were devastated later by the inadvertent spread of diseases introduced by Europeans.[1] In the 150 years that followed Columbus's arrival in 1492, the Native American population of North America was reduced by 80 percent from diseases, including measles, smallpox and influenza.[55] The damage done by these viruses significantly aided European attempts to displace and conquer the native population.[56]

By the 18th century, smallpox was endemic in Europe. There were five epidemics in London between 1719 and 1746, and large outbreaks occurred in other major European cities. By the end of the century about 400,000 Europeans were dying from the disease each year.[57] It reached South Africa in 1713, having been carried by ships from India, and in 1789 the disease struck Australia.[57] In the 19th century, smallpox became the single most important cause of death of the Australian Aborigines.[58]

In 1546 Girolamo Fracastoro (1478–1553) wrote a classic description of measles. He thought the disease was caused by "seeds" (seminaria) that were spread from person to person. An epidemic hit London in 1670, recorded by Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689), who thought it was caused by toxic vapours emanating from the earth.[23] As a physician, he was a skilled observer and kept meticulous records.[59]

Yellow fever is an often lethal disease caused by a flavivirus. The virus is transmitted to humans by mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) and first appeared over 3,000 years ago.[60] In 1647, the first recorded epidemic occurred on Barbados and was called "Barbados distemper" by John Winthrop, who was the governor of the island at the time. He passed quarantine laws to protect the people – the first ever such laws in North America.[61] Further epidemics of the disease occurred in North America in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries.[62]

The first known cases of dengue fever occurred in Indonesia and Egypt in 1779. Trade ships brought the disease to the US, where an epidemic occurred in Philadelphia in 1780.[63] In the 19th century there were frequent dengue epidemics throughout the Americas, and by 1897 almost the whole of the southern US was affected.[63]

Many paintings can be found in the museums of Europe depicting tulips with attractive coloured stripes. Most, such as the still life studies of Johannes Bosschaert, were painted during the 17th century. These flowers were particularly popular and became sought after by those who could afford them. At the peak of this tulip mania in the 1630s, one bulb could cost as much as a house.[64] It was not known at the time that the stripes were caused by a virus accidentally transferred by humans to tulips from jasmine.[65] Weakened by the virus, the plants turned out to be a poor investment. Only a few bulbs produced flowers with the attractive characteristics of their parent plants.[66]

Until the Irish Great Famine of 1845–1852, the commonest cause of disease in potatoes was not the mould that causes blight but a virus. The disease, called "curl", is caused by potato leafroll virus, and it was widespread in England in the 1770s, where it destroyed 75% of the potato crop. At that time, the Irish potato crop remained relatively unscathed.[67]

Discovery of vaccination

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762) was an aristocrat, a writer and the wife of a Member of Parliament. In 1716, her husband, Edward Wortley Montagu was appointed British Ambassador in Istanbul. She followed him there and two weeks after her arrival discovered the local practice of protection against smallpox by variolation – the injection of pus from smallpox victims into the skin.[5] Her younger brother had died of smallpox, and she too had had the disease. Determined to spare her five-year-old son Edward from similar suffering, she ordered the embassy surgeon, Charles Maitland to variolate him. On her return to London, she asked Maitland to variolate her four-year-old daughter in the presence of the king's physicians.[68] Later, Montagu persuaded the Prince and Princess of Wales to sponsor a public demonstration of the procedure. Six prisoners who had been condemned to death and were awaiting execution at Newgate Prison were offered a full pardon for serving as the subjects of the public experiment. They accepted, and in 1721 were variolated. All the prisoners recovered from the procedure; to test its protective effect one of them, a nineteen-year-old woman, was ordered to sleep in the same bed as a ten-year-old smallpox victim for six weeks. She did not contract the disease.[69]

The experiment was repeated on eleven orphan children, all of whom survived the ordeal, and by 1722 even King George I's grandchildren had been inoculated.[70] But the practice was not entirely safe and caused many deaths. The procedure was expensive; some medical practitioners charged between £5 and £10 and some sold the method to other practitioners for fees between £50 to £100, or for half of the profits. Variolation became a lucrative franchise but it remained beyond the means of many until the late 1770s.[71] At the time nothing was known about viruses or the immune system, and no one knew how the procedure afforded protection.[72]

Edward Jenner (1749–1823), a British rural physician, was variolated as a boy. He had suffered greatly from the ordeal but survived fully protected from smallpox. Jenner knew of a local belief that dairy workers who had contracted a relatively mild infection called cowpox were immune to smallpox. He decided to test the "theory" (though he was probably not the first to do so). On 14 May 1796 he selected "a healthy boy, about eight years old for the purpose of inoculation for the Cow Pox".[73] The boy, James Phipps (1788–1853), survived the experimental inoculation with cowpox virus and suffered only a mild fever. On 1 July 1796, Jenner took some "smallpox matter" (probably infected pus) and repeatedly inoculated Phipps's arms with it. Phipps survived, and was subsequently inoculated with smallpox more than 20 times without succumbing to the disease. Vaccination – the word is derived from the Latin vacca meaning "cow" – had been invented.[74] Jenner's method was soon shown to be safer than variolation and by 1801 more than 100,000 people had been vaccinated.

Despite objections from those medical practitioners who still practised variolation, and who foresaw a decline in their income, free vaccination of the poor was introduced in the UK in 1840. Because of associated deaths, variolation was declared illegal in the same year.[75] Vaccination was made compulsory in England and Wales by the 1853 Vaccination Act and parents could be fined £1 if their children were not vaccinated before they were three months of age. But the law was not adequately enforced, and the system for providing vaccinations, unchanged since 1840, was ineffective. After an early compliance by the population only a small proportion were vaccinated.[76] Compulsory vaccination was not well received and, following protests, the Anti Vaccination League and the Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League were formed in 1866.[77][78] The antivaccination Following the anti-vaccination campaigns there was a severe outbreak of smallpox in Gloucester in 1895, the city's first in twenty years; 434 people died, including 281 children.[79] Despite this, the British government conceded to the protesters and the Vaccination Act of 1898 abolished fines and made provision for a "conscientious objector" clause – the first use of the term – for parents who did not believe in vaccination. During the following year, 250,000 objections were granted and by 1912 less than half of the population of newborns were being vaccinated.[80] By 1948, smallpox vaccination was no longer compulsory in the UK.[81]

Louis Pasteur and rabies

Rabies is an often fatal disease caused by the infection of mammals with rabies virus. Today it is mainly a disease that affects wild mammals such as foxes and bats, but it is one of the oldest known virus diseases: rabies is a Sanskrit word (rabhas) that dates from 3000 BC,[28] which means "madness" or "rage"[24] and the disease has been known for over 4000 years.[27] Descriptions of rabies can be found in Mesopotamian texts,[82] and the ancient Greeks called it "lyssa" or "lytta" meaning madness.[27] References to rabies can be found in the Laws of Eshnunna, which date from 2300 BC. Aristotle (384–322 BC) wrote one of the earliest undisputed descriptions of the disease and how it was passed to humans. Celsus, in the first century AD, first recorded the symptom called hydrophobia and suggested that the saliva of infected animals and humans contained a slime or poison – to describe this he used the word "virus".[27] Rabies does not cause epidemics, but the infection was greatly feared because of its terrible symptoms, which include insanity, hydrophobia, and death.[27]

In France during the time of Louis Pasteur ( 1822–1895) there were only a few hundred rabies infections in humans each year, but cures were desperately sought. Aware of the possible danger, Pasteur began to look for the "microbe" in mad dogs.[83] Pasteur showed that when the dried spinal cords from dogs that had died from rabies were crushed and injected into healthy dogs they did not become infected. He repeated the experiment several times on the same dog with tissue that had been dried for fewer and fewer days, until the dog survived even after injections of fresh rabies-infected spinal tissue. Pasteur had immunised the dog against rabies as he later did with 50 more.[84]

Although he had little idea how his method worked, he went on to test it on a boy. Joseph Meister (1876–1940) was brought to Pasteur by his mother on 6 July 1885. He was covered in bites, having been set upon by a mad dog. A bricklayer had defended the boy from the dog with an iron bar, but only after the salivating dog had bitten the boy 14 times. Meister's mother begged Pasteur to help her son. Pasteur was a scientist, not a physician, and he was well aware of the consequences for him if things were to go wrong. Pasteur decided to help the boy and injected him with increasingly virulent rabid rabbit spinal cord over the following 10 days.[85] Later Pasteur wrote, "as the death of this child appeared inevitable, I decided, not without deep and severe unease ... to try out on Joseph Meister the procedure, which had consistently worked on dogs".[86] Meister recovered and returned home with his mother on 27 July. Pasteur successfully treated a second boy in October that same year; Jean-Baptiste Jupille (1869–1923) was a 15-year-old shepherd boy who had been severely bitten as he tried to protect other children from a rabid dog.[87] Pasteur's method of treatment remained in use for over 50 years.[88]

Little was known about the cause of the disease until 1903 when Adelchi Negri (1876–1912) first saw microscopic lesions – now called Negri bodies – in the brains of rabid animals.[89] He wrongly thought they were protozoan parasites. Paul Remlinger (1871–1964) soon showed by filtration experiments that they were much smaller than protozoa, and even smaller than bacteria. Thirty years later, Negri bodies were shown to be accumulations of particles 100–150 nanometres long, now known to be the size of rhabdovirus particles – the virus that causes rabies.[27]

20th and 21st centuries

At the turn of the 20th century, evidence for the existence of viruses was obtained from experiments with filters that had pores too small for bacteria to pass through; the term "filterable virus" was coined to describe them.[90] Although the modern concept of a virus was at that time slowly beginning to gain acceptance, the word is ancient. In Latin it means a "slimy liquid, poison offensive odour or taste", and it first appears in the medical literature in the 18th century to describe a poisonous fluid.[91]

Until the 1930s most scientists believed that viruses were small bacteria, but following the invention of the electron microscope in 1931 they were shown to be completely different, to a degree that not all scientists were convinced they were anything other than accumulations of toxic proteins.[92] The situation changed radically when it was discovered that viruses contain genetic material in the form of DNA or RNA.[93] Once they were recognised as distinct biological entities they were soon shown to be the cause of numerous infections of plants, animals, and even of bacteria.[94]

Of the many diseases of humans that were found to be caused by viruses in the 20th century one, smallpox, has been eradicated. But the diseases caused by viruses such as HIV and influenza virus have proved to be more difficult to control.[95] Other diseases, such as those caused by arboviruses, are presenting new challenges.[96]

As humans have changed their behaviour during the course of history, so have viruses. In ancient times the human population was too small for pandemics to occur and, in the case of some viruses, too small for them to survive. In the 20th and 21st century increasing population densities, revolutionary changes in agriculture and farming methods, and high speed travel have contributed to the spread of new viruses and the re-appearance of old ones.[97][98] Like smallpox, some viral diseases might be conquered, but others, such as SARS will continue to present new challenges.[99] Although vaccines are still the most powerful weapon against viruses, in recent decades antiviral drugs have been developed to specifically target viruses as they replicate in their hosts.[100] The 2009 influenza pandemic showed how rapidly new strains of viruses continue to spread around the world, despite efforts to contain them.[101]

Advances in virus discovery and control continue to be made. Human metapneumovirus, which is a cause of respiratory infections including pneumonia, was discovered in 2001.[102] A vaccine for the papillomaviruses that cause cervical cancer was developed between 2002 and 2006.[103] In 2005, human T lymphotropic viruses 3 and 4 were discovered.[104] In 2008 the WHO Global Polio Eradication Initiative was re-launched with a plan to eradicate poliomyelitis by 2015.[105] In 2010, the largest virus, Megavirus chilensis was discovered to infect amoebae.[106] These giant viruses have renewed interest in the role viruses play in evolution and their position in the tree of life.[107]

Smallpox eradication

Smallpox virus was one of the biggest killers of the 20th century, during which it killed 300 million people.[109] Since its emergence it has probably killed more humans than any other virus.[110] In 1966 an agreement was reached by the World Health Assembly (the decision-making body of World Health Organisation) to start an "intensified smallpox eradication programme" and attempt to eradicate the disease within ten years.[111] At the time, smallpox was still endemic in thirty-one countries[112] including Brazil, the whole of the Indian sub-continent, Indonesia and sub-Saharan Africa.[111] This ambitious goal was considered achievable for several reasons: the vaccine afforded exceptional protection; there was only one type of the virus; there were no animals that naturally carried it; the incubation period of the infection was known and rarely varied from 12 days; and infections always gave rise to symptoms, so it was clear who had the disease and who did not.[113][114]

Following mass vaccinations, disease detection and containment were central to the eradication campaign. As soon as cases were detected, the victims were isolated as were their close contacts who were vaccinated.[115] Successes came quickly, by 1970 smallpox was no longer endemic in western Africa, and by 1971 in Brazil.[116] By 1973, smallpox remained endemic only in the Indian sub-continent, Botswana and Ethiopia.[112] Finally, after thirteen years of coordinated disease surveillance and vaccination campaigns throughout the world, the World Health Organisation declared smallpox eradicated in 1979.[117] Although the main weapon used was vaccinia virus, which was used as the vaccine, no one seems to know exactly where vaccinia virus came from; it is not the strain of cowpox that Edward Jenner had used, and it is not a weakened form of smallpox.[118]

The eradication campaign led to the death of Janet Parker (c. 1938–1978) and the subsequent suicide of the smallpox expert Henry Bedson (1930–1978). Parker was an employee of the University of Birmingham who worked in the same building as Bedson's smallpox laboratory. She was infected by a strain of smallpox virus that Bedson's team had been investigating. Ashamed of the accident and blaming himself, Bedson cut his throat.[119]

Before the September 11 attacks on America in 2001, it was planned to destroy all the known remaining stocks of smallpox virus that were kept in laboratories in US and Russia. But fears of bioterrorism using smallpox virus and the possible need for the virus in the development of drugs to treat the infection have put an end to this plan.[120] Had the destruction gone ahead, smallpox virus might have been the first to be made extinct by human intervention.[121]

Measles

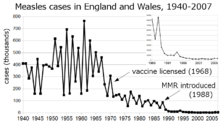

Measles is highly contagious. Before the introduction of vaccination in the US in the 1960s there were more than 500,000 cases a year resulting in about 400 deaths. In developed countries children were mainly infected between the ages of three and five years old, but in developing countries half the children were infected before the age of two.[122] In the US and the UK, there were regular annual or bi-annual epidemics of the disease, which depended on the number of children born each year.[123] The current epidemic strain evolved at the beginning of the 20th century – probably between 1908 and 1943.[124]

In London between 1950 and 1968 there were epidemics every two years, but in Liverpool, which had a higher birth rate, there was an annual cycle of epidemics. During the Great Depression in the US before the Second World War the birth rate was low, and epidemics of measles were sporadic. After the war the birth rate increased, and epidemics occurred regularly every two years. In developing countries with very high birth rates, epidemics occurred every year.[123] Measles is still a major problem in densely populated, less-developed countries with high birth rates and lacking effective vaccination campaigns.[125]

By the mid-1970s, following a mass vaccination programme that was known as "make measles a memory", the incidence of measles in the US had fallen by 90 percent.[126] Similar vaccination campaigns in other countries have reduced the levels of infection by 99 percent over the past 50 years.[127] Susceptible individuals remain a source of infection and include those who have migrated from countries with ineffective vaccination schedules, or who refuse the vaccine or choose not to have their children vaccinated.[128] Humans are the only natural host of measles virus.[126] Immunity to the disease following an infection is lifelong; that afforded by vaccination is long term but eventually wanes.[129]

The use of the vaccine has been controversial. In 1998, Andrew Wakefield and his colleagues published a research paper that claimed to link the MMR vaccine with autism. The study was widely reported and led to a widespread concern about the safety of vaccinations.[130] Wakefield's research was found to be fraudulent and in 2010, he was struck off the UK medical register and can no longer practise medicine in the UK.[131] In the wake of the controversy, the MMR vaccination rate in the UK fell from 92% in 1995, to less than 80% in 2003.[132] Cases of measles rose from 56 in 1998, to 1370 in 2008, and similar increases occurred throughout Europe.[131] In April 2013, an epidemic of measles in Wales in the UK broke out, which mainly affected teenagers who had not been vaccinated.[132] But despite this controversy, measles has been eliminated from Finland, Sweden and Cuba.[133] Japan abolished mandatory vaccination in 1992, and in 1995–1997 more than 200,000 cases were reported in the country.[134] Measles remains a public health problem in Japan, where it is now endemic; a National Measles Elimination Plan was established in December 2007, with a view to eliminating the disease from the country.[135] The possibility of global elimination of measles has been debated in medical literature since the introduction of the vaccine in the 1960s. Should the current campaign to eradicate poliomyelitis be successful, it is likely that the debate will be renewed.[136]

Poliomyelitis

During the summers of the mid-20th century, parents in the US and Europe dreaded the annual appearance of poliomyelitis (or polio), which was commonly known as "infantile paralysis".[137] The disease was rare at the beginning of the century, and worldwide there were only a few thousand cases a year, but by the 1950s there were 60,000 cases each year in the US alone.[138]

During 1916 and 1917 there had been a major epidemic in the US; 27,000 cases and 6,000 deaths were recorded, with 9,000 cases in New York City.[139] At the time nobody knew how the virus was spreading.[140] Many of the city's inhabitants, including scientists, thought that impoverished slum-dwelling immigrants were to blame even though the prevalence of the disease was higher in the more prosperous districts such as Staten Island – a pattern that had also been seen in cities like Philadelphia.[141] Many other industrialised countries were affected at the same time. In particular, before the outbreaks in the US, large epidemics had occurred in Sweden.[142]

The reason for the rise of polio in industrialised countries in the 20th century has never been fully explained. The disease is caused by a virus that is passed from person to person by the faecal-oral route,[143] and only naturally infects humans.[144] It is a paradox that it became a problem during times of improved sanitation and increasing affluence.[143] Although the virus was discovered at the beginning of the 20th century, its ubiquity was unrecognised until the 1950s. It is now known that fewer than two percent of individuals who are infected develop the disease, and most infections are mild.[145] During epidemics the virus was effectively everywhere, which explains why public health officials were unable to isolate a source.[144]

Following the development of vaccines in the mid-1950s, mass vaccination campaigns took place in many countries. In the US, following a campaign promoted by the March of Dimes, the annual number of polio cases fell dramatically; the last outbreak was in 1979.[146] In 1988 the World Health Organisation along with others launched the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, and by 1994 the Americas were declared to be free of disease, followed by the Pacific region in 2000 and Europe in 2003.[147] At the end of 2012, only 223 cases were reported by the World Health Organisation. Mainly poliovirus type 1 infections, 122 occurred in Nigeria, one in Chad, 58 in Pakistan and 37 in Afghanistan. Vaccination teams often face danger; seven vaccinators were murdered in Pakistan and nine in Nigeria at the beginning of 2013.[148] In Pakistan, the campaign was further hampered by the murder of a police officer on 26 February 2013 who was providing security. These murders were committed by Islamic militants who believe that the eradication campaign is part of a western plot against muslims.[149]

AIDS

The human immunodeficiency virus HIV is the virus that – when then infection is not treated – can cause AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).[150] Most virologists believe that HIV originated in sub-Saharan Africa during the 20th century.[151] It is now a pandemic, and over 70 million individuals have been infected by the virus. By 2011, an estimated 35 million had died from AIDS,[152] making it one of the most destructive epidemics in recorded history.[153]

HIV-1 is one of the most significant viruses to have emerged in the last quarter of the 20th century.[154] When, in 1981, a scientific article was published that reported the deaths of five young gay men, no one knew that they had died from AIDS. The full scale of the epidemic – and that the virus had been silently emerging over several decades – was not known.[155]

HIV crossed the species barrier between chimpanzees and humans in Africa in the early decades of the 20th century. During the years that followed there were enormous social changes and turmoil in Africa. Population shifts were unprecedented as vast numbers of people moved from rural farms to the expanding cities, and the virus was spread from remote regions to densely populated urban conurbations. The incubation period for AIDS is around 10 years, so a global epidemic starting in the early 1980s is credible.[156] At this time there was much scapegoating and stigmatisation.[157] The "out of Africa" theory for the origin of the HIV pandemic was not well received by Africans, who felt that the "blame" was misplaced. This led the World Health Assembly to pass a 1987 resolution, which stated that HIV is "a naturally occurring [virus] of undetermined geographic origin".[158] By 2007, over 36 million people had HIV or AIDS, about 67% of them from sub-Saharan Africa.[159]

The HIV pandemic has challenged communities and brought about social changes throughout the world. Opinions on sexuality are more openly discussed. Advice on sexual practices and drug use – which were once taboo – is sponsored by many governments and their healthcare providers. Debates on the ethics of provision and cost of anti-retroviral drugs, particularly in poorer countries, have highlighted inequalities in healthcare and stimulated far-reaching legislative changes.[160]

Influenza

When influenza virus undergoes a genetic shift many humans have no immunity to the new strain, and if the population of susceptible individuals is high enough to maintain the chain of infection then pandemics occur. The genetic changes usually happen when different strains of the virus co-infect animals, particularly birds and swine. Although many viruses of vertebrates are restricted to one species, influenza virus is an exception.[161] The last pandemic of the 19th century occurred in 1899 and resulted in the deaths of 250,000 people in Europe. The virus, which originated in Russia or Asia, was the first to be rapidly spread by people on trains and steamships.[162]

A new strain of the virus emerged in 1918, and the subsequent pandemic of Spanish flu was one of the worst natural disasters in history.[162] The death toll was enormous; throughout the world more than 20 million people died from the infection, and there were 550,000 reported deaths caused by the disease in the US, ten times the country's losses during the First World War.[163] Although cases of influenza occurred every winter, there were only two other pandemics in the 20th century.

In 1957 another new strain of the virus emerged and caused a pandemic of Asian flu; although the virus was not as virulent as the 1918 strain, over one million died worldwide. The next pandemic occurred when Hong Kong flu emerged in 1968, a new strain of the virus that completely replaced the 1957 strain.[164] Affecting mainly the elderly, the 1968 pandemic was the least severe, but 33,800 were killed in the US.[165] It may be significant that new strains of influenza virus often originate in the far east; in rural China the concentration of ducks, pigs, and humans in close proximity is the highest in the world.[166]

The next pandemic was in 2009, but none of the last three has caused anything near the devastation seen in 1918. Exactly why the strain of influenza that emerged in 1918 was so devastating is a question that still remains unanswered.[162]

Yellow fever, dengue and other arboviruses

Arboviruses are viruses that are transmitted to humans and other vertebrates by blood-sucking insects. These viruses are diverse; the term "arbovirus" – which was derived from "arthropod borne virus" – is no longer used in formal taxonomy because many different species of virus are known to be spread in this way.[167] There are more than 500 species of arboviruses, but in the 1930s only three were known to cause disease in humans: yellow fever, dengue fever and Pappataci fever.[168] More than 100 of such viruses are now known to cause human diseases.[169]

Yellow fever is the most notorious disease caused by a flavivirus.[170] In 1905, the last major epidemic in the US occurred.[62] During the building of the Panama Canal thousands of workers died from the disease.[171] Yellow fever originated in Africa and the virus was brought to the Americas on cargo ships, which were harbouring the Aedes aegypti mosquito that carries the virus. The first recorded epidemic in Africa occurred in Ghana, West Africa, in 1926.[172] In the 1930s the disease re-emerged in Brazil. Fred Soper, an American epidemiologist (1893–1977), discovered the importance of the sylvatic cycle of infection in non-human hosts, and that infection of humans was a "dead end" that broke this cycle.[173]

Although the yellow fever vaccine is one of the most successful ever developed,[174] epidemics continue to occur. In 1986–91 epidemics occurred in West Africa and over 20,000 people were infected, 4,000 of whom died.[175]

In the 1930s, St. Louis encephalitis, eastern equine encephalitis and western equine encephalitis emerged in the US. The virus that causes La Crosse encephalitis was discovered in the 1960s,[176] and West Nile virus arrived in New York in 1999.[177] As of 2010, dengue virus is the most prevalent arbovirus and increasingly virulent strains of the virus have spread across Asia and the Americas.[178]

Hepatitis viruses

Hepatitis is a disease of the liver that has been recognised since antiquity.[179] Symptoms include jaundice, a yellowing of the skin, eyes and body fluids.[180] There are numerous causes, including viruses – particularly hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus.[181] Throughout history epidemics of jaundice have been reported mainly affecting soldiers at war. This "campaign jaundice" was common in the Middle Ages. It occurred among Napoleon's armies and during most of the major conflicts of 19th and 20th centuries, including the American Civil War, where over 40,000 cases were reported including around 150 deaths.[182] But the viruses that cause epidemic jaundice were not discovered until the middle of the 20th century.[183] The name for epidemic jaundice, hepatitis A, and for blood-borne infectious jaundice, hepatitis B, were first used in 1947,[184] following a publication in 1946 giving evidence that the two diseases were distinct.[185] The first virus discovered that could cause hepatitis was hepatitis B virus in the 1960s, which was named after the disease it causes.[186] Hepatitis A virus was not discovered until 1974.[187]

The discovery of hepatitis B virus and the invention of tests to detect it have radically changed many medical, and some cosmetic procedures. The screening of donated blood, which was introduced in the early 1970s, has dramatically reduced the transmission of the virus.[188] Donations of human blood plasma and Factor VIII collected before 1975 often contained infectious levels of hepatitis B virus. [189] Until the late 1960s, hypodermic needles were often reused by medical professionals, and tattoo artists' needles were a common source of infection.[190] In the late 1990s, needle exchange programmes were established in Europe and the US to prevent the spread of infections by intravenous drug users.[191] These measures also helped to reduce the subsequent impact of HIV and hepatitis C virus.[192]

Epizootics

Epizootics are outbreaks (epidemics) of disease among non-human animals.[193] During the 20th century significant epizootics of viral diseases in animals, particularly livestock, occurred worldwide. The many diseases caused by viruses included foot-and-mouth disease, rinderpest of cattle, avian and swine influenza, swine fever and bluetongue of sheep. Viral diseases of livestock can be devastating both to farmers and the wider community, as the outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in the UK in 2001 has shown.[194]

In the early years of the 20th century rinderpest, a disease of cattle, was common in Asia and parts of Europe.[195] The prevalence of the disease was steadily reduced during the course of the century by control measures that included vaccination.[196] By 1908 Europe was free from the disease. Outbreaks did occur following the Second World War, but these were quickly controlled. The prevalence of the disease increased in Asia, and in 1957 Thailand had to appeal for aid because so many buffaloes had died that the paddy fields could not be prepared for rice growing.[197] Russia west of the Urals remained free from the disease – lenin approved several laws on the control of the disease – but cattle in eastern Russia were constantly infected with rinderpest that originated in Mongolia and China where the prevalence remained high.[198] India controlled the spread of the disease, which had retained a foothold in the southern states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala, throughout the 20th century,[199] and had eradicated the disease by 1995.[200] Africa suffered two major panzootics in the 1920s and 1980s.[201] There was a severe outbreak in Somalia in 1928 and the disease was widespread in the country until 1953. In the 1980s, outbreaks in Tanzania and Kenya were controlled by the use of 26 million doses of vaccine, and a recurrence of the disease in 1997 was suppressed by an intensive vaccination campaign.[202] By the end of the century rinderpest had been eradicated from most countries. A few pockets of infection remained in Ethiopia and Sudan,[203] and in 1994 the Global Rinderpest Eradication Programme was launched by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) with the aim of global eradication by 2010.[204] In May 2011, the FAO and the World Organisation for Animal Health announced that "rinderpest as a freely circulating viral disease has been eliminated from the world."[205]

Foot-and-mouth disease is a highly contagious infection caused by an aphthovirus, and is classified in the same family as poliovirus. The virus has infected animals, mainly ungulates, in Africa since ancient times and was probably brought to the Americas in the 19th century by imported livestock.[206] Foot-and-mouth disease is rarely fatal, but the economic losses incurred by outbreaks in sheep and cattle herds can be high.[207] The last occurrence of the disease in the US was in 1929, but as recently as 2001, several large outbreaks occurred throughout the UK and thousands of animals were killed and burnt.[208]

The natural hosts of influenza viruses are pigs and birds, although it has probably infected humans since antiquity.[209] The virus can cause mild to severe epizootics in wild and domesticated animals.[210] Many species of wild birds migrate and this has spread influenza across the continents throughout the ages. The virus has evolved into numerous strains and continues to do so, posing an ever-present threat.[211]

In the early years of the 21st century epizootics in livestock caused by viruses continued to have serious consequences. Bluetongue disease, a disease caused by an orbivirus broke out in sheep in France in 2007.[212] Until then the disease had been mainly confined to the Americas, Africa, southern Asia and northern Australia, but it is now an emerging disease around the Mediterranean.[213]

Agriculture

During the 20th century, many "old" diseases of plants were found to be caused by viruses. These included maize streak and cassava mosaic disease.[214] As with humans, when plants thrive in close proximity, so do their viruses. This can cause huge economic losses and human tragedies. In Jordan during the 1970s, where tomatoes and cucurbits (cucumbers, melons and gourds) were extensively grown, entire fields were infected with viruses.[215] Similarly, in Côte d'Ivoire, thirty different viruses infected crops such as legumes and vegetables. In Kenya cassava mosaic virus, maize streak virus and groundnut viral diseases caused the loss of up to 70 percent of the crop.[215] Cassava is the most abundant crop that is grown in eastern Africa and it is a staple crop for more than 200 million people. It was introduced to Africa from South America and grows well in soils with poor fertility. The most important disease of cassava is caused by cassava mosaic virus, a geminivirus, which is transmitted between plants by whiteflies. The disease was first recorded in 1894 and outbreaks of the disease occurred in eastern Africa throughout the 20th century, which often resulted in famine.[216]

In the 1920s the sugarbeet growers in the western United States suffered huge economic loss caused by damage done to their crops by the leafhopper-transmitted beet curly top geminivirus. In 1956, between 25 to 50 percent of the rice crop in Cuba and Venezuela was destroyed by rice hoja blanca tenivirus. In 1958, it caused the loss of many rice fields in Columbia. Outbreaks recurred in 1981, which caused losses of up to 100 percent.[217] In Ghana between 1936 and 1977, the mealybug-transmitted cacao swollen root badnavirus caused the loss of 162 million cacao trees, and further trees were lost at the rate of 15 million each year.[218][219] In 1948, in Kansas, US, 7% of the wheat crop was destroyed by wheat streak mosaic virus, spread by the wheat curl mite (Aceria tulipae).[220]

Such disasters occurred when human intervention caused ecological changes by the introduction of crops to new vectors and viruses. Cacao is native to South America and was introduced to West Africa in the late 19th century. In 1936, swollen root disease had been transmitted to plantations by mealybugs from indigenous trees.[221] New habits can trigger outbreaks of plant virus diseases. Before 1970, the rice yellow sobemovirus was only found in the Kisumu district of Kenya, but following the irrigation of large areas of East Africa and extensive rice cultivation, the virus spread throughout East Africa.[222] Human activity introduced plant viruses to naive crops. The citrus tristeza virus (CTV) was introduced to South America from Africa between 1926 and 1930. At the same time, the aphid Toxoptera citricidus was carried from Asia to South America and this accelerated the transmission of the virus. By 1950, more than 6 million citrus trees had been killed by the virus in São Paulo, Brazil.[222] CTV and citrus trees probably coevolved for centuries in their original countries. The dispersal of CTV to other regions and its interaction with new citrus varieties resulted in devastating outbreaks of plant diseases.[223] Because of the problems caused by the introduction – by humans – of plant viruses, many countries have strict importation controls on any materials that can harbour dangerous plant viruses or their insect vectors.[224]

Emerging viruses

Emerging viruses are those that have only relatively recently infected the host species.[225] In humans, many emerging viruses have come from other animals.[226] When viruses jump to other species the diseases caused in humans are called zoonoses or zoonotic infections.[227]

SARS

SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) is caused by a new type of coronavirus.[228] Other coronaviruses were known to cause mild infections in humans,[229] so the virulence and rapid spread of this novel virus strain caused alarm among health professionals as well as public fear.[225] But the fears of a major pandemic were not realised, and by July 2003, after causing around 8,000 cases and 800 deaths, it had ended.[230] The exact origin of the SARS virus is not known, but evidence suggests that it came from bats.[231]

West Nile virus

West Nile virus, a flavivirus, was first identified in 1937 when it was found in the blood of a feverish woman. The virus, which is carried by mosquitoes and birds, caused outbreaks of infection in North Africa and the Middle East in the 1950s and by the 1960s horses in Europe fell victim. The largest outbreak in humans occurred in 1974 in Cape Province, South Africa and 10,000 people became ill.[232] An increasing frequency of epidemics and epizootics (in horses) began in 1996, around the Mediterranean basin, and by 1999 the virus had reached New York. Since then the virus has spread throughout the United States.[232] In the US, mosquitoes carry the highest amounts of virus in late summer, and the number of cases of the disease increases in late August to early September. When the weather becomes colder, the mosquitoes die and the risk of disease decreases. In Europe, many outbreaks have occurred; in 2000 a surveillance programme began in the UK to monitor the incidence of the virus in humans, dead birds, mosquitoes and horses.[233] The mosquito (Culex modestus) that can carry the virus breeds on the marshes of north Kent. This species was not previously thought to be present in the United Kingdom, but it is widespread in southern Europe where it carries West Nile virus.[234]

Nipah virus

In 1997 an outbreak of respiratory disease occurred in Malaysian farmers and their pigs. Later more than 265 cases of encephalitis, of which 105 were fatal, were recorded.[235] A new paramyxovirus was discovered in a victim's brain; it was named Nipah virus, after the village where he had lived. The infection was caused by a virus from fruit bats, after their colony had been disrupted by deforestation. The bats had moved to trees nearer the pig farm and the pigs caught the virus from their droppings.[236]

Viral hemorragic fevers

Several highly lethal viral pathogens are members of the Filoviridae. Filoviruses are filament-like viruses that cause viral hemorrhagic fever, and include the Ebola and Marburg viruses. The Marburg virus attracted widespread press attention in April 2005 for an outbreak in Angola. Beginning in October 2004 and continuing into 2005, the outbreak was the world's worst epidemic of any kind of viral haemorrhagic fever.[237] Ebola and Marburg viruses are transmitted to humans by monkeys,[238] and Lassa fever by rats (Mastomys natalensis).[239] Zoonotic infections can be severe because humans often have no natural resistance to the infection and it is only when viruses become well-adapted to new host that their virulence decreases. Some zoonotic infections are often "dead ends", in that after the initial outbreak the rate of subsequent infections subsides because the viruses are not efficient at spreading from person to person.[240]

Friendly viruses

Sir Peter Medawar (1915–1987) described a virus as "a piece of bad news wrapped in a protein coat".[241] With the exception of the bacteriophages, viruses had a well-deserved reputation for being nothing but the cause of diseases and death. The discovery of the abundance of viruses and their overwhelming presence in many ecosystems has led modern virologists to consider them in a new light.[242]

Viruses are everywhere. It is estimated that there are about 1031 (100 billion trillion) viruses on Earth. Most of them are bacteriophages, and most are in the oceans.[243] Microorganisms constitute more than 90 percent of the biomass in the sea,[244] and it has been estimated that viruses kill approximately 20% of this biomass each day and that there are fifteen times as many viruses in the oceans as there are bacteria and archaea.[244] Viruses are the main agents responsible for the rapid destruction of harmful algal blooms, which often kill other marine life,[244] and help maintain the ecological balance of different species of marine blue-green algae,[245] and thus adequate oxygen production for life on Earth.[246]

The emergence of strains of bacteria that are resistant to a broad range of antibiotics has become a problem in the treatment of bacterial infections.[247] Only two new classes of antibiotics have been developed in the past 30 years,[248] and novel ways of combating bacterial infections are being sought.[247] Bacteriophages were first used to control bacteria in the 1920s,[249] and a large clinical trial was conducted by Soviet scientists in 1963.[250] This work was unknown outside the Soviet Union until the results of the trial were published in the West in 1989.[251] The recent and escalating problems caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria has stimulated a renewed interest in the use of bacteriophages and phage therapy.[252]

The Human Genome Project has revealed the presence of numerous viral DNA sequences scattered throughout the human genome.[253] These sequences make up around 8% of human DNA,[254] and appear to be the remains of ancient retrovirus infections of human ancestors.[255] These pieces of DNA have firmly established themselves in human DNA.[256] Most of this DNA is no longer functional, but some may have brought with them novel genes that are important in human development.[257][258] Viruses have transferred important genes to plants. About 10 percent of all current photosynthesis uses genes that have been transferred to plants by viruses.[259]

References

- ^ a b c McMichael AJ (2004). "Environmental and social influences on emerging infectious diseases: past, present and future". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 359 (1447): 1049–58. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1480. PMC 1693387. PMID 15306389.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Villarreal, p. 344

- ^ Hughes AL, Irausquin S, Friedman R (2010). "The evolutionary biology of poxviruses". Infection, Genetics and Evolution : Journal of Molecular Epidemiology and Evolutionary Genetics in Infectious Diseases. 10 (1): 50–9. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2009.10.001. PMC 2818276. PMID 19833230.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Georges AJ, Matton T, Courbot-Georges MC (2004). "[Monkey-pox, a model of emergent then reemergent disease]". Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses (in French). 34 (1): 12–9. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2003.09.008. PMID 15617321.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Tucker, p. 6

- ^ Clark, p. 20

- ^ a b Gibbs AJ, Ohshima K, Phillips MJ, Gibbs MJ (2008). Lindenbach, Brett (ed.). "The prehistory of potyviruses: their initial radiation was during the dawn of agriculture". PLoS ONE. 3 (6): e2523. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002523. PMC 2429970. PMID 18575612.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Fargette D, Pinel-Galzi A, Sérémé D, Lacombe S, Hébrard E, Traoré O, Konaté G (2008). Holmes, Edward C. (ed.). "Diversification of rice yellow mottle virus and related viruses spans the history of agriculture from the neolithic to the present". PLoS Pathogens. 4 (8): e1000125. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000125. PMC 2495034. PMID 18704169.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Zeder MA (2008). "Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (33): 11597–604. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801317105. PMC 2575338. PMID 18697943.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Baker, pp. 40–50

- ^ Barrett T, Rossiter PB (1999). "Rinderpest: the disease and its impact on humans and animals". Advances in Virus Research. Advances in Virus Research. 53: 89–110. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60344-9. ISBN 9780120398539. PMID 10582096.

- ^ a b Crawford (2000), p. 225

- ^ White DW, Suzanne Beard R, Barton ES (2012). "Immune modulation during latent herpesvirus infection". Immunological Reviews. 245 (1): 189–208. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01074.x. PMC 3243940. PMID 22168421.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shors, p. 13

- ^ Donadoni, Sergio (1997). The Egyptians. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 292. ISBN 0-226-15556-0.

- ^ Zimmer, p. 82

- ^ a b Levins, pp. 297–298

- ^ Dobson, pp. 140–141

- ^ a b Karlen, p. 57

- ^ Furuse Y, Suzuki A, Oshitani H (2010). "Origin of measles virus: divergence from rinderpest virus between the 11th and 12th centuries". Virol. J. 7: 52. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-7-52. PMC 2838858. PMID 20202190.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Griffin DE (2007). "Measles Virus". In Martin, Malcolm A.; Knipe, David M.; Fields, Bernard N.; Howley, Peter M.; Griffin, Diane; Lamb, Robert (ed.). Fields' virology (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-6060-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ McNeill, William Hardy (1977). Plagues and peoples. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-385-12122-9.

- ^ a b c Retief F, Cilliers L (2010). "Measles in antiquity and the Middle Ages". South African Medical Journal. 100 (4): 216–7. PMID 20459960.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Zuckerman, Arie J. p. 291 Cite error: The named reference "isbn0-471-90341-8" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Mahy, (a) p. 10

- ^ Gottfried RS (1977). "Population, plague, and the sweating sickness: demographic movements in late fifteenth-century England". The Journal of British Studies. 17: 12–37. doi:10.1086/385710. PMID 11632234.

- ^ a b c d e f Mahy, (b) p. 243

- ^ a b Shors, p. 352

- ^ Pickett, p. 10

- ^ Riedel S (2005). "Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination". Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 18 (1): 21–5. PMC 1200696. PMID 16200144.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Clark, p. 21

- ^ Gilchrist, p. 41

- ^ Barrett, p. 15

- ^ a b Barrett, p. 87

- ^ Quinn, pp. 40–41

- ^ Thomas Penn (2012). Winter King: The Dawn of Tudor England. Thomas Penn. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 325–326. ISBN 0-14-104053-X.

- ^ Quinn, p. 41

- ^ Karlen, p. 81

- ^ Quinn, p. 40

- ^ Elmer, Peter (2004). The healing arts: health, disease and society in Europe, 1500–1800. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. xv. ISBN 0-7190-6734-0.

- ^ Porter, p. 9

- ^ Quinn, p. 9

- ^ Quinn, pp. 39–57

- ^ Dobson, p. 172

- ^ Quinn, p. 59

- ^ a b Potter CW (2001). "A history of influenza". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 91 (4): 572–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x. PMID 11576290.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Quinn, p. 71

- ^ Quinn, p. 72

- ^ Dobson, p. 174

- ^ McMichael AJ (2004). "Environmental and social influences on emerging infectious diseases: past, present and future". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 359 (1447): 1049–58. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1480. PMC 1693387. PMID 15306389.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Glynn and Glynn, p. 31

- ^ Tucker, p. 10

- ^ Berdan, Frances (2005). The Aztecs of central Mexico: an imperial society. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 182–183. ISBN 0-534-62728-5.

- ^ Glynn and Glynn, p. 33

- ^ Standford CB. Planet Without Apes. Cambridge MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University. p. 108. ISBN 0-674-06704-5.

- ^ Oldstone, pp. 61–68

- ^ a b Tucker, pp. 12–13

- ^ Glynn and Glynn, p. 145

- ^ Sloan AW (1987). "Thomas Sydenham, 1624–1689". South African Medical Journal. 72 (4): 275–8. PMID 3303370.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mahy, (b) p. 514

- ^ Dobson, pp. 146–147

- ^ a b Patterson KD (1992). "Yellow fever epidemics and mortality in the United States, 1693–1905". Soc Sci Med. 34 (8): 855–65. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(92)90255-O. PMID 1604377.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "pmid1604377" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Chakraborty, T (2008). Dengue Fever and Other Hemorrhagic Viruses (Deadly Diseases and Epidemics). Chelsea House Publications. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-7910-8506-6.

- ^ Crawford (2011), pp. 121–122

- ^ Mahy, (a) pp. 10–11

- ^ Crawford (2011), p. 122

- ^ Zuckerman, Larry (1999). The potato: how the humble spud rescued the western world. San Francisco: North Point Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-86547-578-4.

- ^ Tucker, pp. 16–17

- ^ Tucker, p. 17

- ^ Lane, p. 137

- ^ Lane, pp. 138–139

- ^ Zimmer, p. 83

- ^ Reid, p. 18

- ^ Reid, p. 19

- ^ Lane, p. 140

- ^ Deborah Brunton (2008). The politics of vaccination: practice and policy in England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland, 1800–1874. Rochester, N.Y., USA: University of Rochester Press. pp. 39–45. ISBN 1-58046-036-4.

- ^ Glynn and Glynn, p. 153

- ^ Brunton, p. 91

- ^ Glynn and Glynn, p. 161

- ^ Glynn and Glynn, p. 163

- ^ Glynn and Glynn, p. 164

- ^ Yuhong, Wu (2001). "Rabies and Rabid Dogs in Sumerian and Akkadian Literature". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 121 (1): 32–43. doi:10.2307/606727. JSTOR 606727.

- ^ Reid, pp. 93–94

- ^ Reid, p. 96

- ^ Reid, pp. 97–98

- ^ Dobson, p. 159

- ^ Dobson, pp. 159–160

- ^ Dreesen DW (1997). "A global review of rabies vaccines for human use". Vaccine. 15: S2–6. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(96)00314-3. PMID 9218283.

- ^ Kristensson K, Dastur DK, Manghani DK, Tsiang H, Bentivoglio M (1996). "Rabies: interactions between neurons and viruses. A review of the history of Negri inclusion bodies". Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 22 (3): 179–87. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.1996.tb00893.x. PMID 8804019.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crawford (2000), p. 14

- ^ Baker, p. 55

- ^ Kruger DH, Schneck P, Gelderblom HR (2000). "Helmut Ruska and the visualisation of viruses". Lancet. 355 (9216): 1713–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02250-9. PMID 10905259.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crawford (2000), p. 15

- ^ Oldstone, pp. 22–40

- ^ Baker, p. 70

- ^ Levins, pp. 123–125, 157–168, 195–198, 199–205 and others

- ^ Karlen, p. 229

- ^ Mahy, (b) p. 585

- ^ Dobson, p. 202

- ^ Carter, p. 315

- ^ Taubenberger JK, Morens DM (2010). "Influenza: the once and future pandemic". Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974). 125 Suppl 3 (7426): 16–26. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7426.1238. PMC 286233. PMID 20568566.

- ^ van den Hoogen BG, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA (2002). "Analysis of the genomic sequence of a human metapneumovirus". Virology. 295 (1): 119–32. doi:10.1006/viro.2001.1355. PMID 12033771.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Frazer IH, Lowy DR, Schiller JT (2007). "Prevention of cancer through immunization: Prospects and challenges for the 21st century". European Journal of Immunology. 37 Suppl 1: S148–55. doi:10.1002/eji.200737820. PMID 17972339.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wolfe ND, Heneine W, Carr JK, Garcia AD, Shanmugam V, Tamoufe U, Torimiro JN, Prosser AT, Lebreton M, Mpoudi-Ngole E, McCutchan FE, Birx DL, Folks TM, Burke DS, Switzer WM (2005). "Emergence of unique primate T-lymphotropic viruses among central African bushmeat hunters". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (22): 7994–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0501734102. PMC 1142377. PMID 15911757.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pirio GA, Kaufmann J (2010). "Polio eradication is just over the horizon: the challenges of global resource mobilization". Journal of Health Communication. 15 Suppl 1: 66–83. doi:10.1080/10810731003695383. PMID 20455167.

- ^ Arslan D, Legendre M, Seltzer V, Abergel C, Claverie JM (2011). "Distant Mimivirus relative with a larger genome highlights the fundamental features of Megaviridae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (42): 17486–91. doi:10.1073/pnas.1110889108. PMC 3198346. PMID 21987820.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zimmer, p. 93

- ^ Glynn and Glynn, p. 219

- ^ Oldstone, p. 4

- ^ Wolfe, p. 113

- ^ a b Glynn and Glynn p. 200

- ^ a b Crawford (2000), p. 220

- ^ Karlen, p. 154

- ^ Shors, p. 388

- ^ Glynn and Glynn, p. 201

- ^ Glynn and Glynn, pp. 202–203

- ^ Belongia EA, Naleway AL (2003). "Smallpox vaccine: the good, the bad, and the ugly". Clinical Medical Research. 1 (2): 87–92. doi:10.3121/cmr.1.2.87. PMC 1069029. PMID 15931293.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Glynn and Glynn, pp. 186–189

- ^ Tucker, pp. 126–131

- ^ "Wary of Attack With Smallpox, U.S. Buys Up a Costly Drug", New York Times, 12 March 2013 (retrieved 25 April 2013

- ^ Oldstone, p. 84

- ^ Dick, G (1978). Immunisation. London: Update. p. 66. ISBN 0-906141-03-6.

- ^ a b Earn DJ, Rohani P, Bolker BM, Grenfell BT (2000). "A simple model for complex dynamical transitions in epidemics". Science. 287 (5453): 667–70. doi:10.1126/science.287.5453.667. PMID 10650003.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Free registration is required. - ^ Pomeroy LW, Bjørnstad ON, Holmes EC (2008). "The evolutionary and epidemiological dynamics of the paramyxoviridae". J. Mol. Evol. 66 (2): 98–106. doi:10.1007/s00239-007-9040-x. PMC 3334863. PMID 18217182.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Conlan AJ, Grenfell BT (2007). "Seasonality and the persistence and invasion of measles". Proceedings. Biological Sciences / the Royal Society. 274 (1614): 1133–41. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.0030. PMC 1914306. PMID 17327206.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Oldstone p. 135

- ^ Dobson, p. 145

- ^ Oldstone, pp. 137–138

- ^ Oldstone, p. 136–137

- ^ Oldstone, pp. 156–158

- ^ a b Waterhouse,L (2012). Rethinking Autism: Variation and Complexity. Academic Press. pp. 229–30. ISBN 978-0-12-415961-7. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ a b Wise J (2013). "Largest group of children affected by measles outbreak in Wales is 10-18 year olds". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 346: f2545. PMID 23604089.

- ^ Oldstone, p. 155

- ^ Oldstone, p. 156

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2008). "Progress toward measles elimination—Japan, 1999–2008". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 57 (38): 1049–52. PMID 18818586.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Moss WJ, Griffin DE (2006). "Global measles elimination". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 4 (12): 900–8. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1550. PMID 17088933.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Karlen, p. 149

- ^ Karlen, p. 150

- ^ Dobson, pp. 163–164

- ^ Karlen, p. 151

- ^ Karlen, p. 152

- ^ Mahy (b), p. 222

- ^ a b Dobson, p. 166

- ^ a b Karlen, p. 153

- ^ Oldstone, p. 179

- ^ Karlen, p. 153–154

- ^ Dobson, p. 165

- ^ BBC News Retrieved 2 March 2013

- ^ "Polio workers Nigeria shot dead" The Guardian,8 February 2013 (retrieved 25 April 2013)

- ^ Clark, p. 149

- ^ Gao F, Bailes E, Robertson DL, et al.. Origin of HIV-1 in the Chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature. 1999;397(6718):436–441. doi:10.1038/17130. PMID 9989410.

- ^ "WHO Global Health Observatory". World Health Organization. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- ^ Mawar N, Saha S, Pandit A, Mahajan U. The third phase of HIV pandemic: social consequences of HIV/AIDS stigma & discrimination & future needs [PDF]. Indian J. Med. Res.. 2005 [Retrieved 13 September 2008];122(6):471–84. PMID 16517997.

- ^ Esparza J, Osmanov S (2003). "HIV vaccines: a global perspective". Current Molecular Medicine. 3 (3): 183–93. doi:10.2174/1566524033479825. PMID 12699356.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Weeks, pp. 15–21

- ^ Weeks, p. 18

- ^ Levins, p. 279

- ^ quoted in Weeks, p. 20

- ^ Weeks, p. 23

- ^ Weeks, pp. 303–316

- ^ Barry, p. 111

- ^ a b c Karlen, p. 144

- ^ Karlen, p. 145

- ^ Mahy, (b) p. 174

- ^ Shors, p. 332

- ^ Crawford (2000), p. 95

- ^ Weaver SC (2006). "Evolutionary influences in arboviral disease". Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 299: 285–314. doi:10.1007/3-540-26397-7_10. ISBN 3-540-26395-0. PMID 16568903.

- ^ Levins, p. 138

- ^ Mahy, (b) p. 24

- ^ Chakraborty, T (2008). Dengue Fever and Other Hemorrhagic Viruses (Deadly Diseases and Epidemics). Chelsea House Publications. p. 38. ISBN 0-7910-8506-6.

- ^ Ziperman HH (1973). "A medical history of the Panama Canal". Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. 137 (1): 104–14. PMID 4576836.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dobson, p. 148

- ^ Ansari MZ, Shope RE (1994). "Epidemiology of arboviral infections". Public Health Reviews. 22 (1–2): 1–26. PMID 7809386.

- ^ Barrett AD, Teuwen DE (2009). "Yellow fever vaccine – how does it work and why do rare cases of serious adverse events take place?". Current Opinion in Immunology. 21 (3): 308–13. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.018. PMID 19520559.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cordellier R (1991). "[The epidemiology of yellow fever in Western Africa]". Bulletin of the World Health Organization (in French). 69 (1): 73–84. PMC 2393223. PMID 2054923.

- ^ Karlen, p. 157

- ^ Reiter P (2010). "West Nile virus in Europe: understanding the present to gauge the future". Eurosurveillance. 15 (10): 19508. PMID 20403311.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ross TM (2010). "Dengue virus". Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. 30 (1): 149–60. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2009.10.007. PMID 20513545.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Topley, W. W. C. (William Whiteman Carlton); Wilson, Graham S. (Graham Selby); Collier, L. H. (Leslie Harold); Balows, A. (Albert); Sussman, Max.; Topley, W. W. C. (William Whiteman Carlton) (1998). Topley Wilson's microbiology and microbial infections. London: Arnold. p. 745. ISBN 0-340-66316-2.

- ^ Zuckerman, Arie J.; Banatvala, J. E.; Pattison, J. R. (John Ridley) (1987). Principles and practice of clinical virology. Chichester ; New York: Wiley. p. 135. ISBN 0-471-90341-8.

- ^ Sharapov, UM.; Hu, DJ. (2010). "Viral hepatitis A, B, and C: grown-up issues". Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 21 (2): 265–86, ix. PMID 21047029.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zuckerman, Arie Jeremy.; Howard, Colin R. (1979). Hepatitis viruses of man. London ; New York: Academic Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-12-782150-3.

- ^ Purcell, RH. (1993). "The discovery of the hepatitis viruses". Gastroenterology. 104 (4): 955–63. PMID 8385046.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zuckerman, Arie Jeremy.; Howard, Colin R. (1979). Hepatitis viruses of ma. London ; New York: Academic Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-12-782150-3.

- ^ Maccallum, FO. (1946). "Homologous Serum Hepatitis". Proc R Soc Med. 39 (10): 655–7. PMC 2181938. PMID 19993377.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Blumberg, BS.; Sutnick, AI.; London, WT.; Millman, I. (1970). "Australia antigen and hepatitis". N Engl J Med. 283 (7): 349–54. doi:10.1056/NEJM197008132830707. PMID 4246769.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Feinstone, SM.; Kapikian, AZ.; Gerin, JL.; Purcell, RH. (1974). "Buoyant density of the hepatitis A virus-like particle in cesium chloride". J Virol. 13 (6): 1412–4. PMC 355463. PMID 4833615.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Allain JP, Candotti D (2012). "Hepatitis B virus in transfusion medicine: still a problem?". Biologicals : Journal of the International Association of Biological Standardization. 40 (3): 180–6. doi:10.1016/j.biologicals.2011.09.014. PMID 22305086.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Howard, p. 191

- ^ Greif J, Hewitt W (1998). "The living canvas". Advance for Nurse Practitioners. 6 (6): 26–31, 82. PMID 9708051.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nacopoulos AG, Lewtas AJ, Ousterhout MM (2010). "Syringe exchange programs: Impact on injection drug users and the role of the pharmacist from a U.S. perspective". Journal of the American Pharmacists Association : JAPhA. 50 (2): 148–57. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09178. PMID 20199955.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Perkins HA, Busch MP (2010). "Transfusion-associated infections: 50 years of relentless challenges and remarkable progress". Transfusion. 50 (10): 2080–99. doi:10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02851.x. PMID 20738828.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fenner's Veterinary Virology, Fourth Edition. Boston: Academic Press. 2010. p. 126. ISBN 0-12-375158-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Shors, p. 19–20

- ^ Barrett, p. 105

- ^ Barrett, p. 106

- ^ Barrett, p. 109

- ^ Barrett, pp. 108–109

- ^ Barrett, p. 112

- ^ Barrett, p. 119

- ^ Barrett, pp. 120–121

- ^ Barrett, p. 122

- ^ Barrett, p. 137

- ^ Barrett, pp. 136–138

- ^ "Joint FAO/OIE Committee on Global Rinderpest Eradication" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- ^ Paton DJ, Sumption KJ, Charleston B (2009). "Options for control of foot-and-mouth disease: knowledge, capability and policy". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 364 (1530): 2657–67. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0100. PMC 2865093. PMID 19687036.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Scudamore JM, Trevelyan GM, Tas MV, Varley EM, Hickman GA (2002). "Carcass disposal: lessons from Great Britain following the foot and mouth disease outbreaks of 2001". Rev. – Off. Int. Epizoot. 21 (3): 775–87. PMID 12523714.