Slovaks

The Slovaks, Slovak people (Slovak Slováci, singular Slovák, feminine Slovenka, plural Slovenky) are a West Slavic people that primarily inhabit Slovakia and speak the Slovak language.

Most Slovaks today live within the borders of the independent Slovakia (circa 5,410,836). There are Slovak minorities in the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Serbia and sizeable populations of immigrants and their descendants in the United States and in Canada.

History

Slavs of the Pannonian Basin

The first known Slavic states on the territory of present-day Slovakia were the Empire of Samo and the Principality of Nitra, founded sometime in the 8th century.

Great Moravia

Great Moravia (833 - ?907) was a Slavic state in the 9th and early 10th centuries, whose creators were the ancestors of the Czechs and Slovaks.[12][13] Important developments took place at this time, including the mission of Greek monks Cyril and Methodius, the development of the Glagolitic alphabet (an early form of the Cyrillic script), and the use of Old Church Slavonic as the official and literary language. Its formation and rich cultural heritage have attracted somewhat more interest since 19th century.

The original territory inhabited by the Slavic tribes included not only present-day Slovakia, but also parts of present-day Poland, southeastern Moravia and approximately the entire northern half of present-day Hungary.[14]

Kingdom of Hungary

The territory of present day Slovakia became part of the Kingdom of Hungary under Hungarian rule gradually from 907 to the early 14th century (major part by 1100) and remained within the framework of this kingdom (see also Upper Hungary or Kingdom of Hungary) until the formation of Czechoslovakia in 1918.[15] However, according to other historians, from 895 to 902, the whole area of the present-day Slovakia became part of the rising Principality of Hungary, and became (without gradation) part of the Kingdom of Hungary a century later.[16][17][18] A separate entity called Nitra Frontier Duchy, existed at this time within the Kingdom of Hungary. This duchy was abolished in 1107. The territory inhabited by the Slovaks in present-day Hungary was gradually reduced.[19]

When most of Hungary was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1541 (see Ottoman Hungary), Upper Hungary (now the territory of present day Slovakia) became the new center of the "reduced" kingdom[20] that remained under Hungarian, and later Habsburg rule, officially called Royal Hungary.[20] Some Croats settled around and in present-day Bratislava for similar reasons. Also, many Germans settled in the Kingdom of Hungary,[20] especially in the towns, as work-seeking colonists and mining experts from the 13th to the 15th century. Jews and Gypsies also formed significant populations within the territory.[20]

After the Ottoman Empire were forced to retreat from present-day Hungary around 1700, thousands of Slovaks were gradually settled in depopulated parts of the restored Kingdom of Hungary (present-day Hungary, Romania, Serbia, and Croatia) under Maria Theresia, and that is how present-day Slovak enclaves (like Slovaks in Vojvodina, Slovaks in Hungary) in these countries arose.

After Transylvania, Upper Hungary (the territory of present day Slovakia), was the most advanced part of the Kingdom of Hungary for centuries (the most urbanized part, intense mining of gold and silver), but in the 19th century, when Buda/Pest became the new capital of the kingdom, the importance of the territory, as well as other parts within the Kingdom fell, and many Slovaks were impoverished. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Slovaks emigrated to North America, especially in the late 19th and early 20th century (between cca. 1880–1910), a total of at least 1.5 million emigrants.

Slovakia exhibits a very rich folk culture. A part of Slovak customs and social convention are common with those of other nations of the former Habsburg monarchy (the Kingdom of Hungary was in personal union with the Habsburg monarchy from 1867 to 1918).

Czechoslovakia

People of Slovakia spent most part of the 20th century within the framework of Czechoslovakia, a new state formed after World War I. Significant reforms and post-World War II industrialization took place during this time. The Slovak language was strongly influenced by the Czech language during this period.[citation needed]

Contemporary Slovaks

The political transformations of 1989, 1993 restored numerous liberties, which have considerably improved the outlook and prospects of Slovaks.

Contemporary Slovak society organically combines elements of both folk traditions and Western European lifestyles.

Name and ethnogenesis

The origin of the Slovaks is disputed among scholars and it is very contentious. The term of "Slovak" is problematic in relation of the medieval period, because it is essentially the product of the modern nationalism as it emerged after the 18th century.[21] Throughout history, the diverse theories regarding the ethnogenesis of the Slovaks were used to justify or unjustify historical situations from variant historical perspectives,[22] as the argument of ‘my-nation-was-here-first’ type was, and still remains to be a useful instrument of legitimizing a nation-state's ownership of a given territory or its claim to an area outside its current borders.[23] The national ideology that the Slovaks are descended from the Slavs who inhabited the territory of present-day Slovakia between the 5th-10th centuries has a long story and it is connected with the ambition of the Slovaks to reach self-determination or autonomy within Hungary (mostly under romantic nationalism of the 19th century and during the Slovak national revival). This continuity theory, supporting the supposed former common past of the Czech and Slovak nations, thus also legitimizating the creation of the united Czechoslovak nation,[22] gained political subvention during the formation of Czechoslovakia.[22] After the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993, the formation of independent Slovakia motivated interest in a particularly Slovak national identity.[24] One reflection of this was the rejection of the common Czechoslovak national identity in favour of a pure Slovak one.[24] Although the definition and identification of the inhabitants of Great Moravia proved to be politically imperative and difficult,[25] additionally historical records are anything else but precise in this question,[25] the current consensus[citation needed] among most of the Slovak historians is that Slovaks exist as a people with consciousness of their national identity since the 9th or 10th century,[26] therefore we can identify the Slavic inhabitants living on the territory of this realm as Slovaks.[citation needed]

Naming various institutions after the saintly brothers and Great Moravian rulers and devoting commemorative plaques and monuments to them became widespread in post-1993 Slovakia.[27][note 1] The laudation of the imagined history of Slovak culture and language led to the myth of the Cyrillo-Methodian dawn of the Slovak nation and was incorporated into the 1991 Slovak Constitution,[28][29] which adverts the spiritual heritage of Cyril and Methodius and the historical heritage of the Great Moravian Empire as inherently Slovak.[29]

On the other hand there are Slovak historians who suggest that:[25]

It is not correct to label Great Moravia as the first state of the Czechs and the Slovaks for the simple reason that the membership of the Czechs in this state had been short lived.

— Stanislav, Kirschbaum (1995), A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival, p. 35.

As Stanislav Kirschbaum points out:[25]

Slavist and literary historians consider the Cyrillo-Methodian literature as the heritage of all Slavs. Other claim that it is the heritage of the Slavs who laid the bases of the Empire of Great Moravia, namely the Slovaks, the Moravians and the Slovenes. Slovak scholars have been saying for three centuries that the literature created in Great Moravia or translated by Sts. Cyril and Methodius and their disciples for the ancestors of the Slovaks are rather part of the Slovak cultural heritage.

— Stanislav, Kirschbaum (1995), A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival, p. 35.

It seems reasonable to propose that the modern Slovaks may be descendants of the Great Moravian population,[30] this proposition is also true in the case of many modern Central European countries.[30] In fact denial of the continuity of the Slavs living in the territory of what is today Slovakia (before the eleventh century and those who have been living there since the eleventh century) is (also) incorrect. In particular the oldest local names in a written form can serve as evidence. On the basis of the known development of the (Slovak) language these names can serve for determining the time of their formation (before the thirteenth century; in the tenth century or before the tenth century). Therefore it should be adequate to deal with the ethnogenesis of Slovaks in more detail.[31] The Catholic Church in Slovakia claims the Byzantine rite from Great Moravia is still preserved in Slovakia, mainly in eastern Slovakia.[32] Also Slavic pagan elements may still be found in many demonstrations of folk culture, forming part of Slovak folklore even to the present day.[33] According to political scientist Timothy Haughton:[34]

The Great Moravian Empire is viewed by some as a kind of golden age of Slovak nationalism. Such harking back to distant history is not retricted to expat nationalist Slovak historians, but is also enshrined in the preamble to the Slovak constitution. The golden age view has much to do with the fact that the Great Moravian Empire was followed by what is labeled as '1000 years of Magyar rule', followed by seventy years of second class citizenship in Czechoslovakia.

— Timothy, Haughton; (2005) Constraints and opportunities of leadership in post-Communist Europe, p. 109.

The theory of the "Great Moravian" and "Cyrillo-Methodian" heritage dates back to the 18th century. In his writing (Historia gentis Slavae. De regno regibusque Slavorum [History of the Slavic People: On the kingdom and kings of the Slavs]) Georgius Papanek (or Juraj Papánek) traces the roots of the Slovaks to Great Moravia.[35]

Other Slovak scholarly view is that the emergence of sense of a common Slovak nationhood did not appear until the 18th or 19th century.[24] According to Polish scholar Tomasz Kamusella tracing the roots of the Slovak nation to the times of Great Moravia, claiming the polity to have been the first Slovak state is nothing else but "ethnolinguistic Slovak nationalism".[30] This 'continuity theory' also contradicts with the internationally accepted theory that distinct Slavic nations had not yet emerged by the 9th century and the culture and language of various Slavic tribes in Central Europe were indistinguishable from each other.[36]

In this interpretation, the Slovaks have the oldest tradition of statehood in Central Europe,[35] but unfortunately, the 'millennium of Hungarian occupation’ caused them to ‘forget’ their proud traditions.[35] Although the idea of the Cyrillo-Methodian heritage is very prevalent in nowadays Slovakia. Some scholars claim there is no continuity in politics, culture,[37] or written language between this early Slavic polity and the modern Slovak nation.[30]

The modern Slovak nation is the result of radical processes of modernization within the Habsburg Empire which culminated in the middle of 19th century.[38] According to the philosopher Ernest Gellner this is contrary to the Slovak myth, which traces the beginnings of the Slovak nation back to the 9th century or even earlier.[38]

According to the Czech priest Josef Dobrovský, Great Moravia was located in Upper Hungary and Moravia (i.e. Present-day Slovakia and Czech Republic). Writers of Slavic origin like Juraj Sklenár, and Juraj Fándly praised Great Moravia as opposed to the ‘heathen Magyars’ who destroyed this realm.[39] In 1879, Jaroslav Vlček wrote that Great Moravia was a common state of Slovaks and Moravians.[40] František Viktor Sasinek asseted in his work "Die Slovaken. Eine Ethnographische Skizze" (The Slovaks: An ethnographic outline) that Great Moravia was the state of the Slovaks, Moravians and Bohemians.[41] According to Josef Ladislav Píč ("O methode dejepisu Slovenska" [On the Methodology of Slovak Historiography]) Great Moravia was the state of the Czechoslovak nation,[41] but he agreed that the separate Slovak nation emerged after the Hungarians destroyed the polity.[41] Slovak historian Julius Botto Jr. asserted ("Slováci. Vývin ich národného povedomia" [The Slovaks: Development of their national consciousness]) that Great Moravia was solely a Slovak realm.[41] Interestingly, Samuel Timon Jesuit priest claimed ("Imago antiquae Hungariae" [The Description of Old Hungary]) that the Hungarians by destroying Great Moravia, had liberated the Slovaks from the Moravian yoke.[42] It was Ján Hollý who imprinted the idea of Great Moravia and the Cyrillo-Methodian literacy on the ideological blueprint of Slovak nationalism with his poems (Svatopluk, 1833; Cyrilo-Methodiana, 1835; Slav, 1839).[39] When the Slovaks and Czechs lived in a common state it was suggested that Great Moravia was the equal legacy of both nations.[25] However, Russian historian George Vernadsky asserted that Great Moravia is the legacy exclusively of the Czechs.[25]

The opinion of Hungarian historian János Karácsonyi was, that the indigenous Slavs had died out or they had been assimilated by Hungarians,[43] therefore contemporary Slovaks are the progeny of the White Croats[43] (arrived from the north and north-west by the twelfth century into Hungary) the Czech (Bohemian, Moravian), Polish (Lesser Polish) and German (Silesian, Saxonian, Swabian) settlers who came to Hungary during 10th–18th century. According to this theory, only a small part of present-day Slovakia was inhabited during the reign of Stephen I,[44] thus there is no direct connection between the autochthonous Slavic population living in the territory of present-day Slovakia before the 12th century and modern Slovaks.[45] After the Treaty of Trianon, the theory of Karácsonyi became very popular among Hungarian politicians and it was utilized to prove the Hungarian view that the separation of the territory of Slovakia from Hungary was unjustified.[22] Czech historian Václav Chaloupecký also admitted that most of the territory of present-day Slovakia (except the southern parts) was a primeval forest until the thirteenth century and an intentionally unpopulated frontier region of the Kingdom of Hungary.[44] Chaloupecký asserted that Slovaks are Czechs by origin but their almost 1000-year's existence in the Kingdom of Hungary led to their separation from the Czech nation.[43] Furthermore, he also considered that the Walachian populations,[44] especially in the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries were significant agents in the ethnogenesis of the Slovaks.[44] However Chaloupecký had no doubts about that after the eleventh century the Slavonic inhabitants of south-western Slovakia were descendants of those Slavs who had lived there in the ninth and the tenth centuries.[22] Regardless of the fact that modern historical and archaeological exploration in the last decades showed the opinions of both Karácsonyi and Chaloupecký to be wrong, their views can be considered in a way identical as they both wanted to put forward arguments for the integrity and legitimacy of the Kingdom of Hungary and Czechoslovakia in the period of writing their works. None of them concealed their intentions, they even underlined it.[46]

The term 'Slovak'

The Slovaks and Slovenes are the only current Slavic nations that have preserved the old name of the Slavs (singular: slověn) in their name - the adjective "Slovak" is still slovenský and the feminine noun "Slovak" is still Slovenka in the Slovak language; only the masculine noun "Slovak" changed to Slovenin, probably in the High Middle Ages, and finally (under Czech and Polish influence) to Slovák around 1400. For Slovenes, the adjective is still slovenski and the feminine noun "Slovene" is still Slovenka, but the masculine noun has since changed to Slovenec. The Slovak name for their language is slovenčina and the Slovene name for theirs is slovenščina. The Slovak term for the Slovene language is slovinčina; and the Slovenes call Slovak slovaščina. The name is derived from proto-Slavic form slovo "word, talk" (cf. Slovak sluch, which comes from the IE root *ḱlew-). Thus Slovaks as well as Slovenians would mean "people who speak (the same language)", i.e. people who understand each other.

According to Nestor and modern Slavic linguists, the above-mentioned word slověn probably was the original name of all Slavs, but most Slavs (Czechs, Poles, Croats, etc.) took other names in the Early Middle Ages. Although the Slovaks themselves seem to have had a slightly different word for "Slavs" (Slovan), they were called "Slavs" by Latin texts approximately up to the High Middle Ages. Thus, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish when Slavs in general and when Slovaks are meant. One proof of the use of "Slavs" in the sense of "Slovaks" are documents of the Kingdom of Hungary which mention Bohemians (Czechs), Poles under a different name.[19] Slovaks of Hungary were dubbed as "Slavi Pannonii"[47] and Czechs as "Slavi Bohemii".[47] The semantic closeness of the ethnonym ‘Slovak’ to that of ‘Slav’ endowed the Slovak national movement with the myth that of all the Slavic nations the Slovaks are the most direct descendants of the original Slavs, and the Slovak language the most direct continuation of Old Slavic.[47]

In other languages

In Hungarian "Slovak" is Tót (pl: tótok), an exonym. It was originally used to refer to all Slavs including Slovenes and Croats, but eventually came to refer primarily to Slovaks. The term is considered offensive in a contemporary context but was used to refer to the Slovaks while modern Slovakia, then called Felvidék, was part of Hungary. Many place names in Hungary such as Tótszentgyörgy, Tótszentmárton, and Tótkomlós still bear the name. Tóth is a common Hungarian surname.

The Slovaks have also historically been variously referred to as Slovyenyn, Slowyenyny, Sclavus, Sclavi, Slavus, Slavi, Winde, Wende, or Wenden.

Ethnic affiliations and genetic origins

The majority of Slovak mtDNAs belong to the common West Eurasian mitochondrial haplogroups (HV, J, T, U, N1, W, and X). In addition, a few Eurasian maternal lineages are also present as a consequence of admixture with Central Asian nomadic tribes, who migrated into Central and Eastern Europe in the early Middle Ages[48] as well as a few sub-Saharan African mtDNA haplotypes (L2a) and Roma-specific mtDNA haplotypes (M5a1 and M35) detected in the eastern part of the country.[49] Recent mtDNA studies do not allow researchers to identify any specific features clearly distinguishing the Slavs from neighboring populations.[49]

Multidimensional scaling analysis of selected European nations showed that Slovak populations do not cluster together.[49] Western Slovaks are located together with the Czechs and Austrians, while eastern Slovaks are placed close to Slovenians.[49] About 3 percent of mtDNAs from eastern Slovakia encompass Roma-specific lineages, which belong to the subhaplogroup J1a.[49]

Quotes from important chronicles

This is how Nestor in his Primary Chronicle (historically correctly) describes the Slovaks: It was the only [united] Slavic nation: the Slavs who were seated at the Danube River (and who were conquered by Onogurs), the Moravians, the Czechs, the Lechites [the ancestors of modern Poles], and the Polianians who are now called the Russians.[50] Nestor calls these Slavs "Slavs of Hungary" in another place of the text, and mentions them in the first place in a list of Slavic nations (besides Moravians, Bohemians, Poles, Russians, etc.), because he considers the Carpathian Basin (including what is today Slovakia) the original Slavic territory.

Anonymus, in his Gesta Hungarorum, calls the Slovaks (around 1200 with respect to past developments) Sclavi, i.e. Slavs (as opposed to "Boemy" - the Bohemians, and "Polony" - the Poles) or in another place Nytriensis Sclavi, i.e. Nitrian Slavs.

Culture

- See also List of Slovaks

The art of Slovakia can be traced back to the Middle Ages, when some of the greatest masterpieces of the country's history were created. Significant figures from this period included the many Masters, among them the Master Paul of Levoča and Master MS. More contemporary art can be seen in the shadows of Koloman Sokol,[51] Albín Brunovský, Martin Benka,[52] Mikuláš Galanda,[51] Ľudovít Fulla.[51] Julius Koller and Stanislav Filko, in the 21st century Roman Ondak, Blazej Balaz. The most important Slovak composers have been Eugen Suchoň, Ján Cikker, and Alexander Moyzes, in the 21st century Vladimir Godar and Peter Machajdík.

The most famous Slovak names can indubitably be attributed to invention and technology. Such people include Jozef Murgaš, the inventor of wireless telegraphy; Ján Bahýľ, Štefan Banič, inventor of the modern parachute; Aurel Stodola, inventor of the bionic arm and pioneer in thermodynamics; and, more recently, John Dopyera, father of modern acoustic string instruments. Štefan Anián Jedlík Slovakia is also known for its polyhistors, of whom include Pavol Jozef Šafárik, Matej Bel, Ján Kollár, and its political revolutionaries, such Milan Rastislav Štefánik and Alexander Dubček.

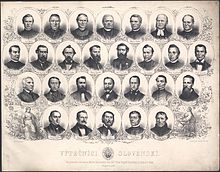

There were two leading persons who codified the Slovak language. The first one was Anton Bernolák whose concept was based on the dialect of western Slovakia (1787). It was the enactment of the first national literary language of Slovaks ever. The second notable man was Ľudovít Štúr. His formation of the Slovak language had principles in the dialect of central Slovakia (1843).

The best known Slovak hero was Juraj Jánošík (the Slovak equivalent of Robin Hood). The prominent explorer and diplomat Móric Beňovský, Hungarian transcript Benyovszky was Slovak as well (he comes from Vrbové in present day Slovakia and is e.g. listed as "nobilis Slavicus - Slovak nobleman" in his secondary school registration).

In terms of sports, the Slovaks are probably best known (in North America) for their ice hockey personalities, especially Stan Mikita, Peter Šťastný, Peter Bondra, Žigmund Pálffy, Marián Hossa and Zdeno Chára. For a list see List of Slovaks. Zdeno Chára is only the second European captain in history of the NHL that led his team to win the Stanley Cup, winning it with Boston Bruins in season 2010–11.

For a list of the most notable Slovak writers and poets, see List of Slovak authors.

-

Girl from Slovakia

-

Moravian-Slovak folk festival

-

Easter in Slovakia

-

Slovak peasant from the Tatra Mountains, 1908

-

Jan Francisci-Rimavsky poet and revolutionary

-

Viola Valachová

partisan -

Adriana Sklenaříková, fashion model and actress

-

Jana Kirschner, pop singer

-

Daniela Hantuchová, the most successful Slovak tennis player of all time

-

Stan Mikita, ice hockey player and member of the Hockey Hall of Fame

-

Peter Šťastný, ice hockey player and member of the Hockey Hall of Fame

-

Zdeno Chára, ice hockey player and captain of the Boston Bruins

-

Jozef Gabčík, Slovak soldier, assassin of Reinhard Heydrich

-

-

Miroslav Iringh, one of the Warsaw Uprising organisers

Statistics

There are approximately 5.4 million autochthonous Slovaks in Slovakia. Further Slovaks live in the following countries (the list shows estimates of embassies etc. and of associations of Slovaks abroad in the first place, and official data of the countries as of 2000/2001 in the second place).

The list stems from Claude Baláž, a Canadian Slovak, the current plenipotentiary of the Government of the Slovak Republic for Slovaks abroad (see e.g.: 6):

- USA (1,200,000 / 821,325*) [*(1)there were, however, 1,882,915 Slovaks in the US according to the 1990 census, (2) there are some 400,000 "Czechoslovaks" in the US, a large part of which are Slovaks] - 19th - 21st century emigrants; see also Census.gov

- Czech Republic (350,000 / 183,749*) [*there were, however, 314 877 Slovaks in the Czech Republic according to the 1991 census] - due to the existence of former Czechoslovakia

- Hungary (39,266 / 17,693)

- Canada (100,000 / 50,860) - 19th - 21st century migrants

- Serbia (60,000 / 59,021*) [especially in Vojvodina;*excl. the Rusins] - 18th & 19th century settlers

- Poland (2002) (47,000 / 2,000*) [* The Central Census Commission has accepted the objection of the Association of Slovaks in Poland with respect to this number ]- ancient minority and due to border shifts during the 20th century

- Romania (18,000 / 17,199) - ancient minority

- Ukraine (17,000 / 6,397) [especially in Carpathian Ruthenia] - ancient minority and due to the existence of former Czechoslovakia

- France (13,000/ n.a.)

- Australia (12,000 / n.a.) - 20th - 21st century migrants

- Austria (10,234 / 10,234) - 20th - 21st century migrants

- United Kingdom (10,000 / n.a.)

- Croatia (5,000 / 4,712) - 18th & 19th century settlers

- other countries

The number of Slovaks living outside Slovakia in line with the above data was estimated at max. 2,016,000 in 2001 (2,660,000 in 1991), implying that, in sum, there were max. some 6 630 854 Slovaks in 2001 (7,180,000 in 1991) in the world. The estimate according to the right-hand site chart yields an approximate population of Slovaks living outside Slovakia of 1.5 million.

Other (much higher) estimates stemming from the Dom zahraničných Slovákov (House of Foreign Slovaks) can be found on SME.[53]

See also

- Slovakia

- History of the Slovak language

- List of Slovaks

- List of Slovak Americans

- Slovak Americans

- Slovaks in Bulgaria

- Slovaks of Croatia

- Slovaks in the Czech Republic

- Slovaks in Hungary

- Slovaks of Romania

- Slovaks in Vojvodina

- Slovenes

Notes

- ^ The University in Nitra was named after St Cyril, and later the university in Trnava added both St Cyril and St Methodius to its name. Kamusella p.887

References

- ^ The Slovak Spectator: Census: Fewer Hungarians, Catholics – and Slovaks, 5 Mar 2012 [1]

- ^ a b c d e (2010 census)

- ^ CIA.gov

- ^ Population by Country of Birth & Nationality, Apr 2009 to Mar 2010 (UK)

- ^ [2]

- ^ Hungarian census 2011

- ^ Transindex.ro

- ^ "CSO Emigration" (PDF). Census Office Ireland. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ "Ethnologue - Slavic languages". www.ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ^ Kirschbaum 1995, p. 25

- ^ Bagnell Bury, John (1923). The Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge: Macmillan. p. 211.

- ^ Ference Gregory Curtis. Chronology of 20th-century eastern European history. Gale Research, Inc., 1994. ISBN 978-0-8103-8879-6, p. 103

- ^ Věd), Archeologický Ústav (Československá Akademie (1964). "The Great Moravia Exhibition: 1100 years of tradition of state and cultural life".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ A history of Eastern Europe: crisis and change, Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries

- ^ Eberhardt 2003, p. 105

- ^ Kristó, Gyula (1996). Hungarian History in the Ninth Century. Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. p. 229. ISBN 963-482-113-8

- ^ http://www.historia.hu/archivum/2001/0103gyorffy.htm

- ^ Kristó, Gyula (1993). A Kárpát-medence és a magyarság régmúltja (1301-ig) (The ancient history of the Carpathian Basin and the Hungarians - till 1301)[3] Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. p. 299. ISBN 963-04-2914-4.

- ^ a b Vauchez, André; Barrie Dobson, Richard; Lapidge, Michael (2000). Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. Vol. 1. Routledge. p. 1363. ISBN 1-57958-282-6, 9781579582821.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ a b c d Eberhardt 2003, p. 104

- ^ William Mahoney, The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, ABC-CLIO, 2011, p. 34

- ^ a b c d e Marsina 1997, p. 17

- ^ Kamusella 2009, p. 948

- ^ a b c W. Warhola, James (2005). "Changing Rule Between the Danube and the Tatras: A study of Political Culture in Independent Slovakia, 1993 - 2005" (PDF). The University of Maine. Orono, Maine, United States.: Midwest Political Science Association 2005 Annual National Conference, April 9, 2005. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ^ a b c d e f Kirschbaum 1995, p. 35

- ^ Kirschbaum 1995, p. 37

- ^ Kamusella 2009, p. 887

- ^ Slovak National Council (1991). "Constitution of the Slovak Republic". Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ a b Kamusella 2009, p. 528

- ^ a b c d Kamusella 2009, p. 131

- ^ http://www.sav.sk/journals/hum/full/hum197b.pdf

- ^ http://www.kbs.sk/?cid=1184747346

- ^ http://piereligion.org/slavic.html

- ^ Timothy Haughton (2005). Constraints and opportunities of leadership in post-Communist Europe. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-7546-3903-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c Kamusella 2009, p. 134

- ^ Bartl, Július (1997). "Ďurica, M. S.: Dejiny Slovenska a Slovákov". Historický časopis. 45 (1): 114–122.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Aviel Roshwald, The Endurance of Nationalism Ancient Roots and Modern Dilemmas, Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 9

- ^ a b Stefan Auer, Liberal Nationalism in Central Europe, Routledge, 2004, p. 135

- ^ a b Kamusella 2009, p. 479

- ^ Kamusella 2009, p. 816

- ^ a b c d Kamusella 2009, p. 814

- ^ Kamusella 2009, p. 819

- ^ a b c Marsina 1997, p. 15

- ^ a b c d Marsina 1997, p. 16

- ^ Marsina 1997, pp. 16–17

- ^ "ETHNOGENESIS OF SLOVAKS" (PDF). SAV. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ a b c Kamusella 2009, p. 132

- ^ Malyarchuk, BA; Vanecek, T; Perkova, MA; Derenko, MV; Sip, M. "Mitochondrial DNA variability in the Czech population, with application to the ethnic history of Slavs; Hum Biol. 2006 Dec;78(6):681-96.". Institute of Biological Problems of the North, Russian Academy of Sciences. Portovaya str. 18, 685000 Magadan, Russia.

- ^ a b c d e Малярчук, Борис Абрамович (29 February 2008). "Mitochondrial DNA Variability in Slovaks, with Application to the Roma Origin" (PDF). Annals of Human Genetics. 72 (2). UK: Blackwell Publishing: 228–240. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00410.x. ISSN 0003-4800. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Permanent Historical Archaeography Committee of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR (1926–1928). Полное собрание русских летописей — Лаврентьевская летопись (PDF) (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Ленинград: Издательство Академии Наук СССР. pp. 18–19. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

бѣ єдинъ ӕзъıкъ Словѣнескъ . Словѣни же сѣдѧху по Дунаєви ихже прıӕша Оугри и Марава . [и] Г Чеси и Лѧхове и Полѧне ӕже нъıнѣ зовомаӕ Русь .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b c Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2009). "Slovakia; Cultural expression". World and Its Peoples. Vol. 7. Marshall Cavendish. p. 993. ISBN 0-7614-7883-3, 9780761478836.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Mikuš 1977, p. 108

- ^ Template:Sk icon SME.sk

- Slovaks in the US PDF

- Slovaks in Czech Republic

- Slovaks in Serbia

- Slovaks in Canada

- Slovaks in Hungary

- Baláž, Claude: Slovenská republika a zahraniční Slováci. 2004, Martin

- Baláž, Claude: (a series of articles in:) Dilemma. 01/1999 – 05/2003

Sources

- Marsina, Richard (1997). Ethnogenesis of Slovaks, Human Affairs, 7, 1997, 1. Trnava, Slovakia: Faculty of Humanities, University of Trnava.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kamusella, Tomasz (2009). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Basingstoke, UK (Foreword by Professor Peter Burke): Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230550704.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. (March 1995). A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; St. Martin's Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-312-10403-0.

{{cite book}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); External link in|authorlink=|ref=harv(help) - Malyarchuk, B.A.; Perkova, M.A.; Derenko, M.V.; Vanecek, T.; Lazur, J.; Gomolcak, P. (2008). "Mitochondrial DNA Variability in Slovaks, with Application to the Roma Origin". Annals of Human Genetics. 72 (2). Journal compilation 2008 University College London: 228. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00410.x.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eberhardt, Piotr (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, Analysis. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mikuš, Joseph A. (1977). Slovakia and the Slovaks. Three Continents Press. ISBN 0-914478-88-5, 9780914478881.

The work is superbly illustrated by Martin Benka, a Slovak painter of comparable

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Maps

-

Slovaks in Vojvodina, Serbia (2002 census)

-

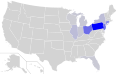

The language spread of Slovak in the United States according to U. S. Census 2000 and other resources interpreted by research of U. S. English Foundation, percentage of home speakers