AC/DC

AC/DC | |

|---|---|

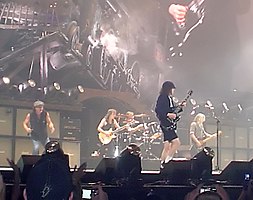

AC/DC in Tacoma, Washington in 2009. From left to right: Brian Johnson, Malcolm Young, Phil Rudd, Angus Young and Cliff Williams | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Genres | |

| Discography | |

| Years active | 1973–present (hiatus from 2016–2018) |

| Labels | |

| Spinoff of | Marcus Hook Roll Band |

| Members | |

| Past members | See former members section or band members article |

| Website | acdc |

AC/DC are an Australian rock band formed in 1973. They were founded by brothers Malcolm Young on rhythm guitar and Angus Young on lead guitar. Their current line-up comprises Angus, bassist Cliff Williams, drummer Phil Rudd, lead vocalist Brian Johnson and rhythm guitarist Stevie Young – nephew of Angus and Malcolm. Their music has been variously described as hard rock, blues rock and heavy metal, but the band calls it simply "rock and roll". They are cited as a formative influence on the new wave of British heavy metal bands, such as Iron Maiden and Saxon. AC/DC were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2003.

AC/DC underwent several line-up changes before releasing their debut album, High Voltage (1975). Membership subsequently stabilised after the release of Let There Be Rock (1977), with the Young brothers, Rudd, Williams and Bon Scott on lead vocals. Seven months after the release of Highway to Hell (1979), Scott died of alcohol poisoning and the other members considered disbanding. However, at the request of Scott's parents, they continued together and recruited English-born singer Johnson as their new front man. Their first album with Johnson, Back in Black (1980), was dedicated to Scott's memory. It became the second best-selling album of all time.

The band's eighth studio album, For Those About to Rock (1981), was their first album to reach number one in the Billboard 200. Prior to the release of Flick of the Switch (1983), Rudd left AC/DC and was replaced by Simon Wright, who was himself replaced by Chris Slade six years later. AC/DC experienced a commercial resurgence in the early 1990s with the release of The Razors Edge (1990); it was their only record to feature Slade, as Rudd returned in 1994. Rudd has since recorded five more albums with the band, starting with Ballbreaker (1995). Their fifteenth studio album, Black Ice was the second-highest-selling record of 2008 and their biggest chart hit since For Those About to Rock, eventually reaching number one worldwide.

The band's line-up remained the same for 20 years until 2014, when Malcolm retired due to early-onset dementia, from which he died three years later; also Rudd was involved in legal troubles. Stevie, who replaced Malcolm, debuted on the album Rock or Bust (2014). On the accompanying tour, Slade filled in for Rudd. In 2016, Johnson was advised to stop touring due to worsening hearing loss and Guns N' Roses singer Axl Rose stepped in as the band's front man for the remainder of that year's dates. Long-time bassist Williams retired at the end of the tour in 2016 and the band entered a two-year hiatus. A reunion of the Rock or Bust line-up was announced in September 2020; the band's seventeenth studio album Power Up was released two months later. American drummer Matt Laug filled in for Rudd at the Power Trip festival in October 2023.

History

Formation and name (1973–1974)

In November 1973,[1][2] brothers Malcolm and Angus Young both on lead guitar formed AC/DC in Sydney with drummer Colin Burgess from the Masters Apprentices, bassist and saxophonist Larry Van Kriedt and vocalist Dave Evans.[2][3][4] Earlier Malcolm and Evans had been members of Velvet Underground – not United States group of same name – based in Newcastle for two years.[2][3][4] The Young brothers had joined the Marcus Hook Roll Band in 1972, which provided their first recordings for a debut album Tales of Old Grand Daddy (1973),[2] although the pair left before it appeared. Malcolm recruited Burgess and Van Kriedt for AC/DC, then Evans responded to an ad in The Sydney Morning Herald and finally Angus joined.[2][4]

AC/DC's first official gig was at Chequers nightclub in Sydney on 31 December 1973.[3][5] In their early days, most members of the band dressed in some form of glam or satin outfit. Angus tried various costumes: Spider-Man, Zorro, a gorilla and a parody of Superman, named Super-Ang.[6][7][8] Their performances involved cover versions of the Rolling Stones, Chuck Berry, the Beatles and "smattering of old blues standards" while trialling few original songs.[3] Angus first wore his characteristic school-uniform stage outfit in April 1974 at Victoria Park, Sydney – the idea was his sister Margaret's.[2][3][7] He portrayed a boy "straight from school to play his guitar."[9] On stage, Evans was occasionally replaced on lead vocals by their first manager, Denis Loughlin from Sherbet.[2] In Paul Stenning's book AC/DC: Two Sides to Every Glory he stated that Evans and Loughlin were incompatible, consequently other members developed bitter feelings toward Evans.[10]

Malcolm and Angus developed the idea for the band's name after Margaret pointed out the symbol "AC/DC" on the AC adapter of her sewing machine.[3] A.C./D.C. is an abbreviation for alternating current/direct current electricity. The brothers felt that this name symbolised the band's raw energy, power-driven performances of their music.[11] It is pronounced one letter at a time, though the band are colloquially known as Acca Dacca in Australia.[2][12] The AC/DC band name is stylised with a high voltage sign separating the AC from DC and has been used on all studio albums, except the international version of Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap.[13] Their logo was designed by United States typographer Gerard Huerta in 1977 and first appeared on Let There Be Rock. Adam Behr of The Bulletin determined, "[its] type font conveyed the sense of electricity implicit in their name."[14]

The group recorded a session in January 1974 at EMI Studios in Sydney, with older brother George Young and Harry Vanda as the producers – both were former members of the Easybeats and Marcus Hook Roll Band.[3][4] Several songs were recorded, including "Can I Sit Next to You, Girl", "Rockin' in the Parlour" and an early version of "Rock 'n' Roll Singer".[15] A week after this session Burgess was fired due to intoxication – he was unconscious during a performance.[2] Burgess later claimed his drink had been tampered with.[16] Subsequently, Van Kriedt was removed as "[his] heart was always in jazz,"[2][17] his recorded bass lines for the January session were re-recorded by George. Their replacements, Neil Smith on bass guitar and Noel Taylor on drums, lasted six weeks, replaced in turn by Rob Bailey and Peter Clack, respectively.[1][3][4] "Can I Sit Next to You, Girl" backed with "Rockin' in the Parlour", taken from the January session, was released in July 1974 as the band's first single.[3][15][18]

The group had developed a strong live reputation by mid-1974, which resulted in a supporting slot on Lou Reed's national tour in August.[3] During that tour, Malcolm switched to rhythm guitar, leaving Angus on lead guitar, the roles the two guitarists played from then on.[19] During 1974, on the recommendation of Michael Chugg, veteran Melbourne promoter Michael Browning booked them to play at his club, the Hard Rock. He was not pleased with their glam rock image and felt that Evans was the wrong singer, but he was impressed by the Young brothers' guitar playing.[20]

Shortly after, Browning received a call from the band members; Loughlin had quit and they were stuck in Adelaide with no money. Following the gig, they hired Browning as their manager, with the co-operation of George and Vanda.[20] The Young brothers decided to abandon their glam rock image, which was favoured by contemporary Melbourne bands Skyhooks and Hush; instead they pursued a harder blues rock sound, Australian pub rock.[21] To this end, they agreed that Evans was no longer a suitable front man.[10]

Bon Scott joins (1974–1976)

In September 1974, Bon Scott, an experienced vocalist previously with the Valentines (1966–1970) and Fraternity (1971–1973),[3][4] joined AC/DC after his former bandmate Vince Lovegrove recommended him to George.[9] Scott had worked as a chauffeur for the group in Adelaide until an audition promoted him to lead singer.[22] Like the Young brothers, Scott was born in Scotland, immigrated to Australia in his childhood and had a passion for blues music. Scott also had experience as a songwriter and drummer.[9] Their debut single's tracks were re-written and vocals re-recorded by Scott. With the replacement of Evans by Scott "[their] working-class style, boogie-rock sound and earthy humour fell into place."[3]

AC/DC had recorded their first studio album, High Voltage in November 1974 with Vanda & Young producing at Albert Studios, Sydney.[3][4] Bailey and Clack were still in the band during its recording, however, Clack played on only one track and the rest were provided by session drummer Tony Currenti, while George handled some bass parts and later redid others.[2][9][23] Recording sessions took ten days and were based on instrumentals written by the Young brothers with lyrics added by Scott.[24] They relocated to Melbourne in that month.[2][3] Both Bailey and Clack were fired in January 1975,[2] with Paul Matters taking over bass duties briefly before being fired in turn and replaced temporarily by George or Malcolm for live duties.[3][4] Matters often questioned the Young brothers' decisions and was incompatible with Scott.[17] Meanwhile, on drums, Ron Carpenter and Russell Coleman had brief tenures before Phil Rudd, from Buster Brown, joined in that month.[3][4] Bassist Mark Evans was enlisted in March 1975, setting the line-up, which lasted two years.[3][4][25]

The band were scheduled to play at the 1975 Sunbury Pop music festival in January; however, they went home without performing following an altercation with the management and crew of headlining act Deep Purple.[2][9][26] High Voltage was released exclusively in Australasia (Australia and New Zealand) on 17 February 1975 via Albert Productions/EMI Music Australia,[3][4][27] which reached the top 20 on the Kent Music Report.[28] It provided a single, their cover version of Big Joe Williams' "Baby, Please Don't Go" (March).

Ian McFarlane observed, "[their] initial achievement was to take the raw energy of Aussie pub rock, extend its basic guidelines, serve it up to a teenybop Countdown audience and still reap the benefits of the live circuit by packing out the pubs."[3] Later that year they released the second single, "It's a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock 'n' Roll)", from their second studio album T.N.T, for which a well-known promotional video was made for the ABC-TV pop music program Countdown, featuring the band miming the song on the back of a flatbed truck. It reached the top ten.[28] AC/DC released T.N.T. on 1 December 1975, only in Australasia,[3][4][29] which peaked at number two in Australia and top 40 in New Zealand.[28][30] The title track was issued as a single in March 1976 and includes the lyric "so lock up your daughter", which was modified into their first UK tour's name.[31]

Initial success and record deal (1976–1977)

Browning sent promo material to contacts in London, which came to the attention of Phil Carson of Atlantic Records – AC/DC signed an international deal with Atlantic in 1976.[3] On arrival in London in April,[9] their scheduled tour with Back Street Crawler was cancelled following the death of their guitarist Paul Kossoff.[2][32]: 44 As a result, they returned to playing smaller venues to build a local following until their label organised the Lock Up Your Daughters tour sponsored by Sounds magazine.[31] At the time, punk rock was breaking and came to dominate the pages of major British music weeklies, NME and Melody Maker. AC/DC were sometimes identified with the punk rock movement by the British press, but they hated punk rock, believing it to be a passing fad; Browning wrote that "it wasn't possible to even hold a conversation with AC/DC about punk without them getting totally pissed off".[20] Their reputation managed to survive the punk upheavals and they maintained a cult following in the UK.[33]

The first AC/DC album to gain worldwide distribution was a 1976 combination of tracks taken from the High Voltage and T.N.T. LPs.[3] Also titled High Voltage, it was released on Atlantic in May 1976,[3] which sold three million copies in US by 2005 according to the RIAA.[34][35][36] The track selection was heavily weighted toward the more recent T.N.T., including only two songs from their first LP. Their third studio album, Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap, was released in the same year in both Australian and European versions, like its predecessor.[37] Track listings varied worldwide; the international version of the album included the T.N.T. track "Rocker", which had previously not been released internationally. The original Australian version included "Jailbreak". This was later more readily available on the 1984 compilation extended play '74 Jailbreak,[38] or as a live version on 1992's Live).[39] Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap was not released in North America until 1981, by which time the band were at the peak of their popularity.[38]

After a brief tour of Sweden, they returned to London where they set new attendance records during their residency at the Marquee.[2][40] However, their appearance at the 1976 Reading Festival failed to gain a positive response from the crowd.[41] They continued to tour throughout Europe and then Australia. From late 1976, after rebuilding their finances, they started recording their fourth studio album, Let There Be Rock. Early the following year they returned to Britain and began a European tour with Black Sabbath. While Scott and Ozzy Osbourne quickly became friends, other members of each group were less cordial. In one incident, Geezer Butler pulled a "silly" flick-knife comb at Malcolm, which resulted in AC/DC being taken off the rest of the tour.[42][43]

Cliff Williams joins and death of Bon Scott (1977–1980)

In mid-1977, Mark Evans was fired – he ascribed disagreements with Angus and Malcolm as contributing factors.[2] He was replaced on bass guitar by Cliff Williams, an experienced musician for UK bands Home (1970–1974) and Bandit (1976).[3][4][22] Neither of the Young brothers has elaborated on the departure of Evans, though Richard Griffiths, the CEO of Epic Records and a booking agent for AC/DC in the mid-1970s, later commented, "You knew Mark wasn't going to last, he was just too much of a nice guy."[6] Evans' autobiography, Dirty Deeds: My Life Inside/Outside of AC/DC, released in 2011, predominantly dealt with his time in AC/DC, including being fired.[44] Evans returned to Australia, where he joined fellow hard rock group Finch.[3][4]

AC/DC's first American radio exposure was through Bill Bartlett at Jacksonville station WPDQ/WAIV in 1975,[45] two years before they played their first US concert as support act for Canadian group Moxy in Austin, Texas on 27 July 1977.[46][47] From booking agent Doug Thaler of American Talent International and the management of Leber-Krebs, they experienced the US stadium circuit, supporting rock acts, Ted Nugent, Aerosmith, Kiss, Styx, UFO and Blue Öyster Cult; they co-headlined with Cheap Trick. AC/DC released their fifth studio album, Powerage, on 5 May 1978.[48] The sole single from Powerage was "Rock 'n' Roll Damnation" (June 1978). An appearance at The Apollo, Glasgow during the Powerage Tour was recorded and released as If You Want Blood You've Got It (1978).[49]

In 1979, the group recorded their sixth studio album Highway to Hell, with producer Robert John "Mutt" Lange,[51] which appeared on 27 July 1979.[52] Eddie Van Halen noted this as his favourite AC/DC record, along with Powerage.[53] It became their first LP to enter the Billboard 200, eventually reaching number 17,[54] and it propelled AC/DC into the top ranks of hard rock acts.[33] Highway to Hell had lyrics that shifted away from flippant and comical toward more central rock themes, putting increased emphasis on backing vocals but still featured AC/DC's signature sound: loud, simple, pounding riffs and grooving back-beats.[55]

In February 1980, the members began to work on their seventh studio album Back in Black, with Scott on drums, instead of vocals.[56][57] On 18 February, Scott purportedly passed out in a car driven by his friend Alistair Kinnear, after a night of drinking at The Music Machine in Camden Town, London.[58][57] According to Kinnear, upon arrival at home, he was unable to move Scott from the car so he left Scott in the car overnight to sleep off the alcohol effects. Unable to wake Scott early on the evening of 19 February, Kinnear rushed him to King's College Hospital, Camberwell, where Scott was pronounced dead on arrival.[57] The official cause of death is "acute alcohol poisoning".[59] Scott's family buried him in Fremantle, Western Australia, the area they emigrated to when he was a boy.[60]

Brian Johnson joins and rebirth (1980–1983)

Following Scott's death, the members briefly considered quitting, but encouraged by the insistence from Scott's parents that he would have wanted them to carry on, they decided to continue and sought a new vocalist.[22] Fat Lip vocalist Allan Fryer, ex-Rick Wakeman vocalist Gary Pickford-Hopkins,[61] and the Easybeats' singer Stevie Wright were touted by the press as possible replacements.[2][62] Various other candidates were considered by the group:[56] ex-Moxy member Buzz Shearman, who was unable to join due to voice issues,[63] Slade vocalist Noddy Holder,[64] and ex-Back Street Crawler vocalist Terry Slesser.[65]

At the advice of Lange, the group brought in ex-Geordie singer Brian Johnson, who impressed the group.[56][66] For the audition, Johnson sang Ike & Tina Turner's "Nutbush City Limits" and then "Whole Lotta Rosie" from Let There Be Rock.[67] After they worked through the rest of the applicants in the following days, Johnson returned for a second audition.[68] Angus later recalled, "I remember the first time I had ever heard [Johnson]'s name was from [Scott]... he had been in England once touring with a band and he had mentioned that [Johnson] had been in a band called Geordie and [Scott] had said '[Johnson], he was a great rock and roll singer in the style of Little Richard.' And that was [Scott]'s big idol, Little Richard...' He mentioned that to us in Australia. I suppose when we decided to continue, [Johnson] was the first name that Malcolm and myself came up with, so we said we should see if we can find him."[69]

On 29 March, Malcolm offered Johnson a place in the band, much to the singer's surprise. Out of respect for Scott, the band wanted a vocalist who would not be an imitator. In addition to his distinctive voice, demeanour and love of classic soul and blues music, the group were impressed by Johnson's engaging personality.[2][3][70] Johnson was officially announced as the lead singer of AC/DC on 1 April 1980.[71] With Johnson, the group completed the song writing previously begun with Scott for Back in Black. Recording took place at Compass Point Studios in The Bahamas a few months after Scott's death. Produced by Lange and recorded by Tony Platt, it became their biggest-selling album and a hard-rock landmark. Its hits are "Hells Bells", "You Shook Me All Night Long", "Rock and Roll Ain't Noise Pollution" and the title track. The album peaked at number one in the UK,[72] and number four in the US, where it spent 585 weeks on the Billboard 200 chart.[54] It also reached the top spot in Australia, Canada, and France.[28][73][74]

The band's eighth studio album, For Those About to Rock We Salute You, appeared on 23 November 1981.[75] It was their first number-one album on the Billboard 200,[54] top three in Australia and Germany.[28][76] It received mixed reviews by critics.[77] Two singles were issued: "Let's Get It Up" and the title track, "For Those About to Rock", which peaked at number 13 and number 15 in the UK, respectively.[72]

Line-up changes and commercial decline (1983–1990)

Instead of Lange, their ninth studio album, Flick of the Switch (1983), was produced by the group's members themselves.[4][78] It was a return to the rawness and simplicity of their early albums, but received mixed reviews and was considered underdeveloped and unmemorable;[79][80] one critic stated that they "had made the same album nine times".[81] Flick of the Switch eventually reached number four on the UK charts;[72] top five in Australia,[28] and Finland.[82] AC/DC had minor success with single "Guns for Hire", reaching number 84 on the Billboard Hot 100.[83]

Rudd has had long-term drug and alcohol addictions.[84][85][86] By mid-1983 his friendship with Malcolm deteriorated and eventually escalated into a physical confrontation after which Rudd was fired partway through the Flick of the Switch sessions.[87] Rudd was replaced by Simon Wright in July 1983 after they held over 700 auditions in the US and UK.[88] Simon Kirke of Free and Bad Company and Paul Thompson of Roxy Music were two drummers who auditioned.[89]

The band's tenth studio album, Fly on the Wall, produced by the Young brothers in 1985,[4] was also regarded as uninspired and direction-less.[90] A concept music video of the same name featured the band at a bar, playing five of the album's ten songs.[91] In 1986, the group returned to the top 20 on singles charts with the made-for-radio "Who Made Who", reaching number nine in Australia and number 16 in the UK.[92] The associated album Who Made Who is the soundtrack to Stephen King's film Maximum Overdrive;[93] it brought together older hits, such as "You Shook Me All Night Long", with a few new songs – the title track and two instrumentals, "D.T." and "Chase the Ace".[94]

In February 1988 both AC/DC and Vanda & Young were inducted into the Australian Recording Industry Association's inaugural Hall of Fame.[95][96][97] The group's eleventh studio album, Blow Up Your Video, released in 1988, was recorded at Studio Miraval in Le Val, France and reunited the band with producers Vanda & Young.[4][98] The group recorded nineteen songs, choosing ten for the final release; though the album was later criticised for containing excessive "filler",[99] it was a commercial success: Blow Up Your Video reached number two on the UK charts and Australia, AC/DC's highest position since Back in Black in 1980.[28][72] It provided an Australian top-five and UK top-twenty single "Heatseeker" and popular songs such as "That's the Way I Wanna Rock 'n' Roll".[28][72]

The Blow Up Your Video World Tour began in February 1988, in Perth, Australia. That April, following live appearances across Europe, Malcolm announced that he was taking time off touring, principally to deal with his alcoholism. Angus and Malcolm's nephew, Stevie Young, temporarily replaced Malcolm on guitar.[3][100] In 1989, Wright left the group to work on British heavy metal band Dio's fifth studio album Lock Up the Wolves (1990); he was replaced by session veteran Chris Slade.[3][4] Johnson was unavailable for several months while finalising his divorce, so the Young brothers wrote all the songs for the next album, a practice they continued for all subsequent releases through Power Up in 2020.[101]

Popularity regained (1990–1999)

The band's twelfth studio album, The Razors Edge, was recorded in Vancouver, Canada, which was mixed and engineered by Mike Fraser and produced by Bruce Fairbairn, who had previously worked with Aerosmith and Bon Jovi.[102][103] Released on 24 September 1990,[104] it was a major success for the band, reaching top three in Australia,[105] Canada,[106] Finland,[82] Germany,[107] and Switzerland.[108] Its lead single "Thunderstruck", peaked at number five on Billboard's Mainstream Rock chart,[109] number four on the ARIA Singles chart,[110] and number 13 on the OCC's UK Singles Chart.[72] Its second single, "Moneytalks", peaked at number 23 on the Billboard Hot 100.[83] By 2006 the album achieved 5× Platinum status in the US;[111] it reached number two on the Billboard 200.[54]

Several shows on the Razors Edge World Tour were recorded for the 1992 live album, AC/DC Live. It was produced by Fairbairn and was called one of the best live albums of the 1990s.[112] AC/DC headlined the Monsters of Rock show during this tour, which was released as a video album, Live at Donington in 1992. During the tour, three fans were killed at a concert at Salt Palace in Salt Lake City on 18 January 1991: when fans rushed the stage crushing the three and injuring others.[113] It took 26 minutes before venue security and group members understood the severity of the situation and halted the concert. AC/DC settled out of court with the victims' families. As a result of this incident, Salt Palace eliminated festival seating from future events.[114][115] In September 1991, AC/DC performed in Moscow for the Monsters of Rock festival in front of 1.6 million people. It was the first open-air rock concert to be held in the former Soviet Union.[116]

AC/DC recorded "Big Gun" in 1993 for the soundtrack of Arnold Schwarzenegger's film Last Action Hero. Released as a single, it reached number one on the US Mainstream Rock chart, the band's first number-one single on that chart.[109] Pacific Gameworks proposed a beat 'em up video game for the Atari Jaguar CD in 1994, AC/DC: Defenders of Metal, which would have featured the group's crew, however, production never started.[117] Angus and Malcolm invited Rudd to several jam sessions during 1994; he was rehired to replace Slade. Recording began in October 1994 at Record Plant Studios in New York City. After 10 weeks recording moved to the Ocean Way Studios, Los Angeles.[118] On 22 September 1995, their thirteenth studio album Ballbreaker, was released,[119] which reached number one in Australia,[120] Sweden,[121] and Switzerland.[121]

In November 1997, a box set Bonfire, was released.[122][123] It contained four albums: a remastered version of Back in Black, Volts – a disc with alternative takes, out-takes and stray live cuts recorded with Scott – and two live albums, Live from the Atlantic Studios and Let There Be Rock: The Movie. Live from the Atlantic Studios was recorded on 7 December 1977 at the Atlantic Studios in New York. Let There Be Rock: The Movie was a double album recorded in December 1979 at the Pavillon de Paris and was the soundtrack of a motion picture, AC/DC: Let There Be Rock.[122][124]

Popularity confirmed (1999–2014)

The hard rockers recorded their fourteenth studio album, Stiff Upper Lip, in 1999, which was produced by George at The Warehouse Studio, Vancouver. Released in February 2000, it was better received by critics than Ballbreaker but was considered lacking in new ideas.[125][126] The Australian release included a bonus disc with three promotional videos and several live performances recorded in Madrid in 1996. The title track was issued as a single, which remained at number one on the US Mainstream Rock charts for four weeks.[109] The band performed it live when they appeared as the musical guest on Saturday Night Live on 18 March 2000.[127] The other singles "Satellite Blues" and "Safe in New York City" reached number one and number seven, respectively on the same chart.[109]

The band signed a long-term, multi-album deal with Sony Music in December 2002,[128][129] which issued their remasters series. Each release contained an expanded booklet featuring rare photographs, memorabilia and notes.[130] In 2003, the entire back-catalogue – except Ballbreaker and Stiff Upper Lip – was remastered and re-released.[131][132] Ballbreaker and Stiff Upper Lip were re-released in 2004.[133] AC/DC were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2003.[134]

The group performed at Molson Canadian Rocks for Toronto supporting the Rolling Stones, with Rush and other artists, on 30 July 2003. The benefit concert assisted the city's tourism industry, which was negatively impacted by the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak. The audience of 450,000 set a record for the largest paid music event in Canadian history.[135] The band came second in a list of Australia's highest-earning entertainers for 2005,[136] and sixth in the following year,[137] despite having neither toured since 2003 nor released an album since 2000. Verizon Wireless gained the rights to release AC/DC's full albums and the entire Live at Donington concert to download in 2008.[138]

Columbia Records released Plug Me In on 16 October 2007, as both double or triple DVD video album. The set consists of five or seven hours of rare footage, respectively and included a recording of AC/DC at a high school performing "School Days", "T.N.T.", "She's Got Balls" and "It's a Long Way to the Top". As with Family Jewels, disc one contains rare shows of the band with Scott and disc two is about the Johnson-era. The collector's edition contains an extra DVD with 21 more rare performances of both Scott and Johnson and more interviews.[139]

AC/DC made their video game debut on Rock Band 2, with "Let There Be Rock" included as a playable track.[140] The set-list from their Live at Donington live album was released as playable songs for the Rock Band series by means of a Wal-Mart-exclusive retail disc, AC/DC Live: Rock Band Track Pack.[141] No Bull: The Directors Cut, a newly edited, comprehensive Blu-ray and DVD of the band's July 1996 Plaza De Toros de las Ventas concert in Madrid, Spain, was released on 9 September 2008.[142]

Black Ice, their fifteenth studio album was released in Australia on 18 October 2008,[143] and issued worldwide two days later.[144] Produced by Brendan O'Brien, mixed and engineered by Mike Fraser, its 15 tracks were their first studio recordings in eight years. Like Stiff Upper Lip, it was recorded at The Warehouse Studio, Vancouver.[145] It was sold in the US exclusively at Wal-Mart and Sam's Club and the band's official website.[144] Black Ice reached number one in 29 countries,[146] including Australia,[147] the UK,[72] and the US.[54]

"Rock 'n' Roll Train", the album's first single, was released to radio on 28 August.[148] On 15 August, AC/DC recorded a video for "Rock 'n' Roll Train" in London with a special selection of fans invited to participate.[149] The Black Ice World Tour supporting the new album was announced on 11 September and began on 28 October in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.[150] On 15 September 2008, AC/DC Radio debuted on Sirius Channel 19 and XM channel 53; it plays their music along with interviews with band members.[151][152]

AC/DC rescheduled six shows on 25 September 2009 for Johnson's recovery from a medical procedure.[153] On 29 September, the band announced a collection of studio and live rarities, Backtracks, which was released on 10 November as a 3×CD/2×DVD/LP box set.[154] On 4 November, AC/DC were announced as the Business Review Weekly top Australian earner, in entertainment, for 2009 with earnings of $105 million. This displaced the Wiggles from the number-one spot for the first time in four years.[155] On 19 April 2010, AC/DC released Iron Man 2, the soundtrack for the eponymous film which compiled earlier tracks from the band's studio albums.[156]

The band headlined Download Festival at Donington Park in June 2010,[157] and closed the Black Ice World Tour in Bilbao, Spain on 28 June 2010, after 20 months in which the band went to 108 cities in over 28 countries, with an estimated total audience of over five million.[158] Three concerts in December 2009 at the River Plate Stadium in Argentina were released as a DVD Live at River Plate on 10 May 2011.[159] An exclusive single from the DVD, featuring the songs "Shoot to Thrill" and "War Machine", was issued on Record Store Day.[160]

In June 2011, AC/DC issued AC/DC: Let There Be Rock on DVD and Blu-Ray, which had its theatrical release in 1980.[161] On 19 November 2012, AC/DC released Live at River Plate on CD, their first live album in 20 years.[162] The entire catalogue – excluding T.N.T. (1975) and the Australian versions of High Voltage (1975), Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (1976) and Let There Be Rock (1977) – became available on the iTunes Store the same day.[163]

Malcolm Young retires (2014–2018)

In response to reports that the group may disband due to Malcolm's illness,[164] Johnson stated on 16 April 2014, that despite Malcolm's absence, "We are definitely getting together in May in Vancouver. We're going to pick up guitars, have a plonk and see if anybody has got any tunes or ideas. If anything happens we'll record it."[165] In July 2014, AC/DC announced that they had finished recording their next album and that Stevie had replaced Malcolm in the studio.[166] On 23 September 2014, AC/DC members confirmed that Malcolm had officially retired from performing.[167] Malcolm's last show with the group had been on 28 June 2010 in Bilbao, Spain;[168] he died on 18 November 2017 at the age of 64, due to his dementia.[169]

Rudd released his first solo album, Head Job, on 29 August 2014.[170] He confirmed that there would be another AC/DC tour and that they had no intention of retiring.[171] On 23 September 2014, the band revealed that their sixteenth studio album, Rock or Bust, featuring eleven tracks, would be released on 28 November 2014 as the first AC/DC album in the band's history without Malcolm on the recordings.[167] Nevertheless, all its compositions were credited to Angus and Malcolm. The members also announced plans for a world tour to promote it with Stevie as Malcolm's replacement.[172]

On 6 November 2014, Rudd was charged with threatening to kill, possession of methamphetamine and possession of cannabis, following a police raid on his home.[173][174][175] AC/DC's remaining members issued a statement clarifying that the tour promoting Rock or Bust would continue, but did not indicated whether or not Rudd would participate or whether he was still a member.[176] At a charity signing before the Grammy Awards, the band were photographed together with Slade. It was later confirmed that he had rejoined for the Grammys and upcoming tour.[177] In April 2015, Rudd pleaded guilty to drugs charges and threatening to kill a former assistant.[178] Shortly thereafter, the band's website showed that Rudd was replaced by Slade on drums.[179] On 9 July 2015, Rudd was denied a discharge without conviction and sentenced to eight months of home detention.[180]

On 7 March 2016, the members announced that the final ten dates of the Rock or Bust World Tour would be rescheduled as Johnson's doctors had ordered him to stop touring immediately: he risked complete deafness if he persisted. The ten cancelled dates were to be rescheduled, "likely with a guest vocalist" later in the year, leaving Johnson's future in touring with the group uncertain.[181] His most recent show with AC/DC was on 28 February 2016; at the Sprint Center in Kansas City.[182] On 16 April 2016, Guns N' Roses front man Axl Rose was announced as the lead vocalist for the remainder of their 2016 tour dates.[183]

Williams indicated he was leaving AC/DC during an interview with Gulfshore Life's Jonathan Foerste on 8 July 2016, "It's been what I've known for the past 40 years, but after this tour I'm backing off of touring and recording. Losing Malcolm, the thing with [Rudd] and now with [Johnson], it's a changed animal. I feel in my gut it's the right thing."[184] At the end of the Rock or Bust World Tour, he released a video statement confirming his departure.[185] His most recent show with AC/DC was in Philadelphia on 20 September 2016.[186] After completing the tour in 2016, AC/DC went on hiatus. George Young died on 22 October 2017, aged 70.[187] Over the next few years, speculation grew that former members Johnson and Rudd were back and working with the band again. A fan living near the Warehouse Studio, Vancouver claimed to have observed them in the outdoor area of the studio from an apartment window.[188][189]

Reunion and Power Up (2018–present)

On 28 September 2020, band members updated their social media accounts with a short video clip depicting a neon light in the shape of the band's lightning bolt logo. This led to speculation that they were due to announce their "comeback, possibly as early as this week or next week."[190] AC/DC officially confirmed, on 30 September 2020, the return of Johnson, Rudd and Williams to the line-up alongside Angus and Stevie, reuniting the Rock or Bust line-up.[191] On 1 October 2020, AC/DC released a snippet of their new song "Shot in the Dark".[192] On 7 October, the band confirmed the upcoming release on 13 November 2020 of their next studio album, Power Up and issued its first single, "Shot in the Dark".[193] The album's track listing was revealed on their website the same day.[194] They had recorded it in August–September 2018 with O'Brien producing at Vancouver's Warehouse Studio, again.[195]

AC/DC launched a dive bar on 2 October 2023, located at Club 5 Bar in Indio, called the High Voltage Dive Bar.[196] AC/DC performed a co-headlining act of the Power Trip music festival, at the Empire Polo Club in Indio, California on 7 October 2023, which was their first show in seven years,[197][198] with Williams being part of the line-up after coming out of retirement,[199] and American drummer Matt Laug, who had previously played for Slash's Snakepit and Alice Cooper, replacing Rudd.[200] The band have dropped clues, giving "speculation" that they would be going on another tour in 2024;[201] including a possible appearance at the 2024 edition of the Rock in Rio festival, set to take place in September in Rio de Janeiro.[202] In November 2023, the rumours expanded as mayor of Munich Dieter Reiter had confirmed that the band booked a show in the Olympic Stadium for 12 June 2024.[202][203][204] Founding drummer Colin Burgess died in mid-December 2023.[205]

Musical style

Aside from an early flirtation with glam rock the group's sound and performance style is based on Australian pub rock.[2][3][206] That style was pioneered by Lobby Loyde of Billy Thorpe's early 1970s group the Aztecs.[207] Vanda noted "the pub crowd as an audience demanded blood—'or else'."[208] He described wanting to "recreate the real Australian pub sound—'not like that American sound, smooth and creamy, nicey, nicey.'"[208] Glenn A. Baker felt they played "rib-crushing, blood-curdling, brain damaging, no bullshit, thunder rock".[209]

The Canberra Times' Tony Catterall reviewed T.N.T., in which "[they] wallow in the lumpen proletarianism that's the home of punk rock" while comparing them with rivals Buster Brown, which are "more imaginative and musically better".[210] Music journalist Ed Nimmervoll summarised, "If we tried to isolate what has characterised Australian rock and roll from the rest of the world's it would be music that's made to be played live, and gets right down to basics with a minimum of distraction... AC/DC captured that essence not long after it crystallised, and they have continued to carry that creed around the world as their own."[9]

According to Vulture music journalist David Marchese, the instrumental foundation of the band's simple sound was the drummer—Rudd, Wright, or Slade—striking the kick drum on the first and third beat of every measure and the snare drum on the second and fourth beat; bassist Williams consistently down-picking an eighth note; Angus performing lead parts that possessed "a clear architecture and even sort of swing, in a frenzied, half-demented way"; and Malcolm's "propulsive" yet nuanced rhythm guitar featuring "little chuks, stutters and silences that give the monstrous riffs life".[211]

For the majority of Malcolm's tenure in AC/DC, he used a Marshall Super Bass head to amplify his rhythm guitar while recording in the studio. According to Chris Gill of Guitar World, this amplifier helped define his signature guitar tone: "clean but as loud as possible to ride on the razor's edge of power amp distortion and deliver the ideal combination of grind, twang, clang and crunch, with no distorted preamp 'hair,' fizz or compression", as heard on songs such as "Let There Be Rock", "Dirty Deeds", "For Those About to Rock" and "Thunderstruck". During 1978 to 1980 Malcolm used a Marshall 2203 100-watt master volume head, which Gill speculates may have contributed to a "slightly more distorted and dark" guitar tone on the albums from that period, including Powerage and Back in Black.[212]

In a comparison of AC/DC's vocalists, Robert Christgau said Scott exhibited a "blokelike croak" and "charm", often singing about sexual aggression in the guise of fun: "Like Ian Hunter or Roger Chapman though without their panache, he has fun being a dirty young man".[213] Johnson, in his opinion, possessed "three times the range and wattage" as a vocalist while projecting the character of a "bloke as fantasy-fiction demigod".[213] By the time Johnson had fully acclimated himself with 1981's For Those About to Rock We Salute You, Christgau said he defined "an anthemic grandiosity more suitable to [the band's] precious-metal status than [Scott]'s old-fashioned raunch", albeit in a less intelligent manner.[213]

Influences

AC/DC's influences include the Rolling Stones, Chuck Berry, Billy Thorpe, the Easybeats and Vanda & Young.[2][3][214] The impact of Australian pub rock on AC/DC was documented on ABC-TV's Long Way to the Top (2001), episode 4: "Berserk Warriors 1973–1981".[215] Angus reflected on his playing style, "it was nerves at first. It was George that told me if you get on stage and play guitar you want to let people know you are doing something. When I started in the band I was shy and had to push myself forward... [patrons] would be throwing beer cans and I thought 'just keep moving' and that's how it all started."[215] George had taught both Malcolm and Angus "how to play guitar and playing them classic rock and roll and blues records until that music was like blood in their veins."[9] According to "Berserk Warrior"'s writers, "hardships of the Australian road would complete AC/DC's training. [Scott] revelled in the lifestyle. Somehow he rose above all the substance abuse to become the ultimate rock and roll front man."[215] Australian acts formed in AC/DC's footsteps are Rose Tattoo (1976) and the Angels (1976).[215]

Several musicians have credited AC/DC for reasserting hard rock's popularity after it had ceded mainstream attention to other musical genres in the late 1970s.[216][217] Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine and Audioslave noted: "Disco was huge and punk and new wave were ascendant, and along came this AC/DC record (Back in Black) which just destroyed everybody. It put hard rock music back on the throne, where it belongs!"[217]

AC/DC's music was a formative influence on the new wave of British heavy metal bands that emerged in the late 1970s, such as Saxon and Iron Maiden, in part as a reaction to the decline of traditional early 1970s hard rock bands. In 2007, critics noted that AC/DC, along with Thin Lizzy, UFO, Scorpions and Judas Priest, were among "the second generation of rising stars ready to step into the breach as the old guard waned."[218] Over the years, many prominent rock musicians have cited AC/DC as an influence, including Dave Mustaine of Megadeth,[219] Josh Homme of Queens of the Stone Age and Kyuss,[220] Dave Grohl of Nirvana and Foo Fighters,[221] Scott Ian of Anthrax,[222] Eric Peterson of Testament,[223] Dexter Holland of the Offspring,[224] Brian Baker of Bad Religion, Minor Threat, Dag Nasty and Junkyard,[225] and bands such as Metallica,[226] Slayer,[227] Exodus,[228] the Cult,[229] and the Living End.[230]

Gene Simmons of hard rock contemporaries Kiss remarked that, "A lot of people look the same and act the same and do the same thing. Every once in a while you see a band like AC/DC. Nobody's like them. We'd like to think we're unique in that way too."[231] Slash of Guns N' Roses called them "with the exception of the [Rolling] Stones, the greatest rock 'n' roll band ever."[232] "I always liked them," said Australian compatriot and singer-songwriter Nick Cave. "We had this TV show called Countdown and they were often on and they were always a riot and absolutely unique. They were a heavy rock band, but Bon Scott would go on Countdown dressed as a schoolgirl and stuff like that. They were always very anarchic and never took the thing too seriously."[233]

Genres

The band's music has been variously described as hard rock, blues rock and heavy metal,[234] but the band calls it simply "rock and roll".[33] Malcolm recalled honing their craft "We'd been playing up to four gigs a day. That really shaped the band... It was a mix of screw you, Jack, and having a good time and all being pretty tough guys... The training ground was Melbourne."[235]

With the recording of Back in Black in 1980, rock journalist Joe S. Harrington believed the band had departed further from the blues-oriented rock of their previous albums and toward a more dynamic attack that adopted punk rock's "high-energy implications" and transmuted their hard rock/heavy metal songs into "more pop-oriented blasts". The band would remain faithful for the remainder of their career, to this "impeccably ham-handed" musical style: "the guitars were compacted into a singular statement of rhythmic efficiency, the rhythm section provided the thunderhorse overdrive and vocalist Johnson bellowed and brayed like the most unhinged practitioner of bluesy top-man dynamics since vintage Robert Plant."[236]

AC/DC have referred to themselves as "a rock and roll band, nothing more, nothing less".[33] In the opinion of Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic, they are "one of the defining acts of '70s hard rock" and reactionary to the period's art rock and arena rock excesses: "AC/DC's rock was minimalist – no matter how huge and bludgeoning their guitar chords were, there was a clear sense of space and restraint."[237] According to Alexis Petridis, their music is "hard-edged, wilfully basic blues-rock" featuring humorous sexual innuendo and lyrics about rock and roll.[238] Music academic Robert McParland described the band's sound as being defined by the heavy rock guitar of the Young brothers, layered power chords and forceful vocals.[234] "For some, AC/DC are the ultimate heavy metal act", Tim Jonze wrote in The Guardian, "but for others, AC/DC aren't a heavy metal act at all, they're a classic rock band – and calling them heavy metal is an act of treachery."[239] On the controversy of categorising their music, McParland wrote:

AC/DC will assert that they are not specifically a metal band. Their music—loud, hard, and guitar-driven—may best be described as hard rock. However, there are people who will say that they are indisputably metal. Therein lies the ongoing problem of categorisation. While AC/DC has referenced the underworld and they have given their listeners 'Highway to Hell' and 'Hell's Bells,' their songs are constructed on straightforward major and minor power chords. They are not modally developed as are a good deal of heavy metal compositions. Their sound is loud and crisp, not muddy or down-tuned.[234]

Criticism

Throughout the band's career, their songs have been criticised as simplistic,[240] monotonous,[241] deliberately lowbrow and sexist.[242] David Marchese from Vulture wrote that, "regardless of the lyricist, whether it was Scott (who was capable of real wit and colour), Johnson, or the Young brothers, there's a deep strain of misogyny in the band's output that veers from feeling terribly dated to straight-up reprehensible."[211] According to Christgau in 1988, "the brutal truth is that sexism has never kept a great rock-and-roller down—from Muddy to Lemmy, lots of dynamite music has objectified women in objectionable ways. But rotely is not among those ways", in regards to AC/DC.[213]

Fans of the band have defended their music by highlighting its "bawdy humour",[243] while members of the group have generally been dismissive of claims that their songs are sexist, arguing that they are meant to be in jest.[211] In an interview with Sylvie Simmons for Mojo, Angus called the band "pranksters more than anything else", while Malcolm said "we're not like some macho band. We take the music far more seriously than we take the lyrics, which are just throwaway lines."[243] Marchese regarded the musical aspect of the Youngs' songs "strong enough to render the words a functional afterthought", as well as "deceptively plain, devastatingly effective, and extremely lucrative".[211]

For the book Under My Thumb: Songs That Hate Women and the Women Who Love Them, The Guardian arts critic Fiona Sturges contributed an essay evaluating her love for AC/DC. While acknowledging she is a feminist and that the band's music is problematic for her, she believed it would be "daft, as opposed to damaging", for female listeners if they can understand the band to be "a bunch of archly sex-obsessed idiots with sharp tunes and some seriously killer riffs". In spite of the "unpleasant sneering quality" of "Carry Me Home"'s claims about a woman who "ain't no lady", the "rape fantasy" of "Let Me Put My Love into You" and the generally one-dimensional portrayals of women, Sturges said songs such as "Whole Lotta Rosie" and "You Shook Me All Night Long" demonstrated that the female characters "are also having a good time and are, more often than not, in the driving seat in sexual terms... it's the men who come over as passive and hopeless, awestruck in the presence of sexual partners more experienced and adept than them."[243]

AC/DC and other artists (see Filthy Fifteen) ran afoul of the Satanic panic of the 1980s. This general fear of modern hard rock and heavy metal was greatly increased in the band's case when serial killer Richard Ramirez was arrested. Ramirez, nicknamed the "Night Stalker" by the press, told police that "Night Prowler" from the 1979 Highway to Hell album had driven him to commit murder.[244] Police also claimed that Ramirez was wearing an AC/DC shirt and left an AC/DC hat at one of the crime scenes.[245] Accusations that AC/DC were devil worshippers were made, the lyrics of "Night Prowler" were analysed and some newspapers attempted to link Ramirez's Satanism with AC/DC's name,[246] arriving at the conclusion that AC/DC actually stood for Anti-Christ/Devil's Child or Devil's Children.[247][248][249]

Awards and achievements

In 1982, the band's first ever nomination at an award show were from the American Music Awards for Favorite Pop/Rock Band/Duo/Group.[250] In 1988, AC/DC were inducted in the ARIA Hall of Fame.[96][97] The municipality of Leganés, near Madrid, named a street in honour of the band as "Calle de AC/DC" (English: "AC/DC Street") on 22 March 2000.[251] Malcolm and Angus attended the inauguration with many fans.[251] The plaque had since been stolen numerous times, forcing the municipality of Leganés to begin selling replicas of the official street plaque.[252]

On 1 October 2004, a central Melbourne thoroughfare, Corporation Lane, was renamed ACDC Lane in honour of the band. The City of Melbourne forbade the use of the slash character in street names, so the four letters were combined.[253] The lane is near Swanston Street where, on the back of a truck, the band recorded their video for the 1975 hit "It's a Long Way to the Top".[254]

AC/DC were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on 10 March 2003.[255][256] During the ceremony the band performed "Highway to Hell" and "You Shook Me All Night Long", with guest vocals provided by host Steven Tyler of Aerosmith. He described the band's power chords as "the thunder from down under that gives you the second most powerful surge that can flow through your body."[257] During the acceptance speech, Johnson quoted their 1977 song "Let There Be Rock".[256] In May 2003, the Young brothers accepted a Ted Albert Award for Outstanding Service to Australian Music at the APRA Music Awards of 2003, during which Malcolm paid special tribute to Scott, who was also a recipient of the award.[258]

In 2003, Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list included Back in Black at number 73,[259] and Highway to Hell at number 199.[260] They also ranked number 72 on the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time, as American record producer Rick Rubin wrote an essay called them the "greatest rock and roll band of all time".[261] In 2004, on their 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list, Rolling Stone included "Back in Black" at number 187,[262] and "Highway to Hell" at number 254.[263] They ranked number four on VH1's list of 100 Greatest Artists of Hard Rock,[264] and number seven on MTV's Greatest Heavy Metal Band of All Time.[265] They ranked number 23 on VH1's list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time in 2010.[266]

They sold over 1.3 million CDs in the US during 2007 despite not having released a new album since 2000 at that point. Additionally, the group's commercial success continues to flourish despite their choice to refrain from selling albums in digital online formats for many years.[267] As of 2023, the band's RIAA US sales figures from 75 million, making AC/DC the fifth-best-selling band in US history and the tenth-best-selling artist, selling more albums than Pink Floyd and Mariah Carey.[268] The RIAA also certified Back in Black as 25× Platinum, for 25 million, in US sales, which made it the fourth-best-selling album of all time in the US.[269] On 20 November 2015, the band were inducted in the Music Victoria Awards 10th Anniversary Hall of Fame.[270] Angus offered a statement, which he declared it was "an absolute honour" to be recognised in the tenth year of the Hall of Fame.[271]

Band members

Current members

- Angus Young – lead guitar, occasional backing vocals (1973–present)

- Phil Rudd – drums (1975–1983, 1994–2015, 2018–present)

- Cliff Williams – bass guitar, backing vocals (1977–2016, 2018–present)

- Brian Johnson – lead vocals (1980–2016, 2018–present)

- Stevie Young – rhythm guitar, backing vocals (2014–present; touring 1988)

Touring members

- George Young – bass guitar, rhythm guitar, drums, backing vocals (1974–1975; died 2017)[187]

- Denis Loughlin – lead vocals (1974; died 2019)[272]

- Bruce Howe – bass guitar (1975)[22]

- Paul Greg – bass guitar (1991)[273]

- Axl Rose – lead vocals (2016)

- Matt Laug – drums (2023–present)

Former members

- Malcolm Young – rhythm guitar, backing vocals (1973–2014; died 2017)

- Larry Van Kriedt – bass guitar (1973–1974, 1975)

- Dave Evans – lead vocals (1973–1974)

- Colin Burgess – drums (1973–1974; substituted 1975; died 2023)

- Neil Smith – bass guitar (1974; died 2013)

- Ron Carpenter – drums (1974)

- Russell Coleman – drums (1974)

- Noel Taylor – drums (1974)

- Rob Bailey – bass (1974–1975)

- Peter Clack – drums (1974–1975)

- Bon Scott – lead vocals (1974–1980; died 1980)

- Paul Matters – bass guitar (1975; died 2020)[17]

- Mark Evans – bass guitar (1975–1977)

- Simon Wright – drums (1983–1989)

- Chris Slade – drums (1989–1994, 2015–2016)

Discography

Studio albums

- High Voltage (1975) (Australia only)

- T.N.T. (1975) (Australia only)

- High Voltage (1976) (international version)

- Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (1976)

- Let There Be Rock (1977)

- Powerage (1978)

- Highway to Hell (1979)

- Back in Black (1980)

- For Those About to Rock We Salute You (1981)

- Flick of the Switch (1983)

- Fly on the Wall (1985)

- Blow Up Your Video (1988)

- The Razors Edge (1990)

- Ballbreaker (1995)

- Stiff Upper Lip (2000)

- Black Ice (2008)

- Rock or Bust (2014)

- Power Up (2020)

Tours

- High Voltage European Tour (1976)

- Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap Tour (1976–1977)

- Let There Be Rock Tour (1977)

- Powerage Tour (1978)

- If You Want Blood, You've Got It Tour (1978–1979)

- Highway to Hell Tour (1979–1980)

- Back in Black Tour (1980–1981)

- For Those About to Rock Tour (1981–1982)

- Flick of the Switch Tour (1983–1985)

- Fly on the Wall Tour (1985–1986)

- Who Made Who Tour (1986)

- Blow Up Your Video World Tour (1988)

- Razors Edge World Tour (1990–1991)

- Ballbreaker World Tour (1996)

- Stiff Upper Lip World Tour (2000–2001)

- Black Ice World Tour (2008–2010)

- Rock or Bust World Tour (2015–2016)

See also

- AC/DShe – an all-female tribute band who covers Bon Scott-era material

- Hell's Belles – another all-female tribute band

- Hayseed Dixie – a parody band performing bluegrass-inspired renditions of songs by AC/DC and others

References

Citations

- ^ a b "AC/DC Lineup Changes: A Complete Guide". Ultimate Classic Rock. 18 April 2016. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Kimball, Duncan (2004). "AC/DC". Milesago: Australasian Music and Popular Culture 1964–1975. Ice Productions. Archived from the original on 16 March 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad

- 1st edition [online]: McFarlane 1999.

- 2nd edition [print]: McFarlane & Jenkins 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Holmgren, Magnus. "AC/DC". Australian Rock Database. Archived from the original on 6 December 2003. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 15, 17.

- ^ a b Walker 2001, pp. 128–133.

- ^ a b staff writers (3 June 2016). "A Short History of Angus Young's School Uniforms". LouderSound. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "Angus Young of AC/DC". Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). 2011. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nimmervoll, Ed. "AC/DC". Howlspace – The Living History of Our Music. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2023. n.b. Incorrectly spells "Currenti" as "Kerrante".

- ^ a b Stenning & Johnstone 2005, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 20.

- ^ Donovan, Patrick (17 May 2004). "Tracker to Acca Dacca". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "Album Covers for AC/DC". Bliss. Elsten Software. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ^ Behr, Adam (31 July 2020). "AC/DC's Back in Black at 40 – Establishing Rock Bands as Brands". The Bulletin. Archived from the original on 29 October 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Elliott 2018, p. 21.

- ^ Baker, Glenn A. (18 December 2023). "Original Drummer with AC/DC Lived Rock'n'roll Lifestyle". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 18 December 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ a b c staff writer (19 October 2020). "Australian Bassist Paul Matters, an Early Member of AC/DC, Has Died". The Music Network. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Engleheart & Durieux 2008, pp. 54–56, 59–60.

- ^ Engleheart & Durieux 2008, pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b c Browning 2014, pp. 100–256.

- ^ Cockington 2001, pp. 198–201.

- ^ a b c d Wall 2012.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 31.

- ^ Engleheart & Durieux 2008, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Engleheart & Durieux 2008, pp. 98, 100, 102–103, 109–111.

- ^ Kielty, Martin (16 December 2020). "When AC/DC Ended Up in a Fistfight with Deep Purple". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kent 1993.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 40.

- ^ Hung, Steffen. "Discography AC/DC". New Zealand Charts Portal (Hung Medien). Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ a b Fricke, David (15 April 2015). "Flashback: AC/DC Refuses To Give Up and Rocks On". Rolling Stone Australia. Archived from the original on 2 November 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Colin Larkin, ed. (1999). Encyclopedia of Popular Music (1st ed.). Virgin Books. ISBN 0-7535-0257-7.

- ^ a b c d Engleheart 1997.

- ^ "Back in Black Tips 21M Mark". Billboard. 7 June 2005. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "AC/DC – High Voltage". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ "American Album Certifications – AC/DC – High Voltage". Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 56.

- ^ a b Elliott 2018, p. 57.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 185.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 49.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 53.

- ^ "AC/DC Guitarist Clears Up Knife Incident with Black Sabbath". Blabbermouth.net. 2 September 2003. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

[Malcolm] Young's version of the story: 'We were staying in the same hotel, and Geezer was in the bar... I was giving him no sympathy. He'd had many too many [drinks] and he pulled out this silly flick knife.'

- ^ Wall, Mick (7 May 2016). "Let There Be Rock: The Album that Saved AC/DC's Career". Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ Johnston, Mandi (19 November 2012). "Review: Dirty Deeds, My Life Inside/Outside of AC/DC, Mark Evans". Mums Lounge. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Fink 2013, pp. 107–111.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 67.

- ^ Fink 2017, p. 29.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "AC/DC – Powerage". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "How AC/DC Elevated Their Career with the Live If You Want Blood, You've Got It". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ "Bon Scott Statue Placed Permanently at Fremantle Fishing Boat Harbour". Blabbermouth.net. 28 October 2008. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 89.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 101.

- ^ "Eddie Van Halen Thanks God for Sobriety and Guitar Riffs". Spinner.com. 11 June 2009. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015 – via vhnd.com.

- ^ a b c d e "AC/DC Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "AC/DC – Highway to Hell". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ a b c Kielty, Martin (21 August 2020). "Angus Young Still Suffers from Stage Fright / 40 Facts About AC/DC's Back in Black / Bon Scott Played Drums on Some of the Demos". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Elliott 2018, p. 106.

- ^ Redd, Wyatt (8 July 2021). "The Raucous Life and Tragic Death of Bon Scott, Legendary Frontman of AC/DC". All That's Interesting. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ Jinman, Richard (19 February 2005). "25 Years on, AC/DC Fans Recall How Wild Rocker Met His End". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 November 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2008.

- ^ "Bon's Highway Leads to the National Trust". Metropolitan Cemeteries Board. 15 February 2006. Archived from the original on 16 November 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ Engleheart & Durieux 2008, p. 318.

- ^ Engleheart & Durieux 2008, p. 308.

- ^ Fink 2017, pp. 367–368.

- ^ Darlington, Andrew. "Straight from His Own Gob – Noddy Holder". Soundchecks.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 April 2005. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ Fink 2013, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Engleheart & Durieux 2008, p. 309.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 121.

- ^ Engleheart & Durieux 2008, pp. 317–318.

- ^ Henderson, Tim (18 February 2010). "AC/DC Guitarist Angus Young Remembers Bon Scott – 'When I Think Back in Hindsight, He Was a Guy That I Always Knew Was Full of Life'". Brave Words & Bloody Knuckles. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ Engleheart & Durieux 2008, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo (1 April 2015). "How Happenstance Originally Brought Brian Johnson to AC/DC". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "AC/DC | Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ "Image: RPM Weekly". RPM. No. 298. 30 August 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2023 – via Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ "AC/DC - French Charts". Les Charts. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 153.

- ^ "Offizielle Deutsche Charts - For Those About to Rock We Salute You". offiziellecharts.de (in German). Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 150.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 158, 167.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 158.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "AC/DC – Flick of the Switch". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Fricke, David (27 October 1987). "AC/DC: Flick of the Switch". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ a b "Finnish Albums" (PDF). Suomen virallinen lista (in Finnish). p. 9. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ a b "AC/DC Chart History (Billboard Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Bremner, Nicole (9 July 2015). "Phil Rudd Warned He'll Go to Jail if He Drinks or Takes Drugs During Home Detention". OneNewsNow. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ Quill, Annemarie (14 May 2016). "Former AC/DC Drummer Phil Rudd Now Living the Quiet Life". Seniors News. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Engleheart & Durieux 2008, pp. 366–367.

- ^ Lifton, Dave (19 July 2015). "Bad Boy Boogie: A Phil Rudd Timeline". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ Engleheart & Durieux 2008, p. 368.

- ^ Engleheart & Durieux 2008, p. 367.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "AC/DC – Fly on the Wall". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ McPadden, Mike (28 June 2015). "AC/DC's Fly on the Wall Turns 30: Rock Out with 30 Album Facts". VH1. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 164.

- ^ Michael, Christopher (30 June 2003). "Epic Records AC/DC Re-issues: Second Wave". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 14 April 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Wiederhorn, Jon (24 May 2023). "37 Years Ago: AC/DC Release Who Made Who". Loudwire. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Middleton, Karen (3 March 1988). "Good Times – Music Awards: A Scratch on the Records". The Canberra Times. Vol. 62, no. 19, 142. p. 23. Retrieved 28 September 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "1988 ARIA Awards Winners". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ a b "ARIA Hall of Fame". Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA). Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 169.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "AC/DC – Blow Up Your Video". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Olivier (26 December 2021). "Simon Wright recalls Stevie Young Replacing Malcolm Young on AC/DC's Blow Up Your Video World Tour". Sleaze Roxx. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 173.

- ^ Henderson, Alex. "AC/DC – The Razors Edge Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 174.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 174, 184.

- ^ Hung, Steffen. "AC/DC – The Razors Edge". Australian Charts Portal (Hung Medien). Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "Image: RPM Weekly". RPM. No. 9106. 8 December 1990. Retrieved 28 September 2023 – via Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ "Offizielle Deutsche Charts - The Razors Edge" (in German). GfK Entertainment. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ Hung, Steffen. "AC/DC Discography". Swiss Hitparade. Hung Medien. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d "AC/DC Chart History (Mainstream Rock Airplay)". Billboard. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ Hung, Steffen. "AC/DC – 'Thunderstruck'". Australian Charts Portal (Hung Medien). Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "American Album Certifications – AC/DC – The Razors Edge". Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Weber, Barry. "AC/DC – AC/DC Live". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Carter, Mike (24 January 1991). "AC/DC Says Band Stopped". Salt Lake City, Utah: The Daily Gazette. p. D14. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "S.L. County Finds no Negligence in Concert Deaths". Deseret News. 9 February 1991. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ "Families Settle Suits Over AC/DC Concert Deaths". Deseret News. 17 December 1992. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ "List of the Most Crowded Music Concerts in History". The Economic Times. 8 November 2015. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ Smith, Jay (30 December 2003). "News: AC/DC - Defenders of Metal". insertcredit.com. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 183.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 183, 186.

- ^ Hung, Steffen. "AC/DC – Ballbreaker". Australian Charts Portal (Hung Medien). Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ a b Hung, Steffen. "Discography AC/DC". Sverigetopplistan (Hung Medien). Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Bonfire – AC/DC : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 184, 186.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 184.

- ^ Wild, David (30 March 2000). "AC/DC: Stiff Upper Lip". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "AC/DC – Stiff Upper Lip". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Irwin, Corey (1 July 2019). "Rock's 60 Biggest Saturday Night Live Moments". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ Elliott 2018, p. 195.

- ^ Richards, Pete (6 December 2002). "AC/DC Sign Big Contract with Sony". Chart Attack. Archived from the original on 21 March 2003. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "AC/DC – Discography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 195, 197.

- ^ "Epic Rolls Out First AC/DC Reissues". Billboard. 30 January 2003. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ "AC/DC: U.K. Reissues Delayed". Blabbermouth.net. 31 July 2004. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ Elliott 2018, pp. 197–198.

- ^ "Stones Rock Out at Toronto's 'Biggest Party'". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). 31 July 2003. Archived from the original on 30 June 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Ziffer, Daniel (13 April 2006). "Wiggles Wriggle Back into Top Spot". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- ^ Dunn, Emily (18 July 2007). "A Wobble, but the Wiggles Still Rule". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- ^ Bruno, Antony (1 August 2007). "AC/DC Goes Digital via Verizon Wireless". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 December 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- ^ "AC/DC: Plug Me In Box Set Track Listing Revealed". Blabbermouth.net. 7 September 2007. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (10 September 2008). "Rock Band 2 TV Commercials Feature AC/DC's 'Let There Be Rock'". MusicRadar. Archived from the original on 26 September 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Breckon, Nick; Faylor, Chris (29 September 2008). "First Rock Band Spin-off Revealed: AC/DC Live Coming as $30 Wal-Mart Exclusive". Shacknews. Archived from the original on 30 September 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ Cohen, Jonathan (18 August 2008). "AC/DC Sets Date, Track List for Black Ice". Billboard. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Cashmere, Paul (3 October 2008). "AC/DC Black Ice Vinyl Goes Exclusive to Indies". Undercover News. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ a b "AC/DC to Release First New Album in Eight Years". NME. 18 August 2008. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Tingen, Paul (January 2009). "Inside Track: AC/DC Black Ice". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "AC/DC Top Sales in 29 Countries". NME. 28 October 2008. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ Hung, Steffen. "AC/DC – Black Ice". Australian Charts Portal (Hung Medien). Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (28 August 2008). "AC/DC Debut New Single, 'Rock 'N Roll Train'". MusicRadar. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "AC/DC Completes Filming 'Rock 'N Roll Train' Video". Blabbermouth.net. 18 August 2008. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "AC/DC Planning 24-Date Tour". Billboard. Associated Press. 17 September 2008. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2023 – via The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Skid (16 September 2008). "AC/DC Radio Debuts on Sirius XM Radio". Sleaze Roxx. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "AC/DC to Host Their Own Exclusive Music Channel on Sirius and XM". Sirius. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ "AC/DC Postpone Six Shows Due to Singer Johnson's Health". Rolling Stone. 25 September 2009. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ "AC/DC Announce Backtracks Rarities and Collectors' Edition Set". NME. 29 September 2009. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ "AC/DC Tops BRW Entertainment Rich List, Ahead of Kylie Minogue and the Wiggles". Herald Sun. 11 April 2009. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2009.

- ^ "AC/DC to Release Soundtrack to Iron Man 2". The West Australian. 27 January 2010. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ "AC/DC to Headline UK Download Festival". The Independent. 27 January 2010. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ "AC/DC's 'Black Ice Tour' Is Second-Highest-Grossing Concert Tour in History". Blabbermouth.net. 26 July 2010. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ Somaiya, Ravi (6 May 2011). "AC/DC Talk Epic Concert DVD Live at the River Plate". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 23 August 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ Stickler, Jon (6 April 2011). "Sony Music Supports UK Record Store Day 2011". Stereoboard. Archived from the original on 20 September 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "AC/DC: Let There Be Rock Concert Film to Receive Blu-Ray Release in June". Blabbermouth.net. 11 February 2011. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (14 September 2012). "AC/DC to Release First Live Album in 20 Years". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (19 November 2012). "AC/DC Joins iTunes, as Spotify Emerges as Music's New Disrupter". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 November 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ Vincent, Peter; Boulton, Martin. "AC/DC to Split Over Sick Band Member, According to Rumours". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ "AC/DC Are Not Retiring, Though Malcolm Young is 'Taking a Break'". The Guardian. 16 April 2014. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ Lopez, Korina (10 July 2014). "AC/DC Finishes Album; Malcolm Young Hospitalized". USA Today. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ a b Vincent, Peter (24 September 2014). "AC/DC Confirm Malcolm Young's Retirement, Rock or Bust Album and World Tour". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 25 September 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ Daly, Rhian (18 November 2017). "Watch Malcolm Young's Last Ever Gig with AC/DC". NME. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (18 November 2017). "Malcolm Young, AC/DC Guitarist and co-Founder, Dead at 64". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ Hartmann, Graham (18 July 2014). "AC/DC Drummer Phil Rudd to Release Solo Album Head Job, Unveils 'Repo Man' Lyric Video". Loudwire. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ Adams, Cameron (22 August 2014). "AC/DC Drummer Phil Rudd Says the Band and Angus Young Will Never Retire". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2023.