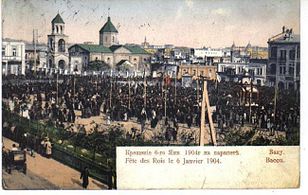

Armenian Church, Baku

| Saint Gregory the Illuminator Cathedral | |

|---|---|

The church in April 2013 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Armenian Apostolic Church |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Not functioning[1] |

| Location | |

| Location | 38 Nizami Street, Baku, Azerbaijan[2] |

| Geographic coordinates | 40°22′18″N 49°50′11″E / 40.371623°N 49.836466°E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Armenian architecture |

| Groundbreaking | 1863[3] |

| Completed | 1869[3] |

Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church,[a] commonly referred to as the Armenian Church of Baku (Template:Lang-hy, Bak’vi haykakan yekeghetsi; Template:Lang-az), is a former Armenian Apostolic church near Fountains Square in central Baku, Azerbaijan. Completed in 1869 it was one of the two Armenian churches in Baku to survive the Soviet anti-religious campaign and the Karabakh conflict and the 1990 pogrom and expulsion of Baku Armenians when it was looted. It is the only Armenian monument to stand in Baku.[4]

History

The church was built between 1863 and 1869.[3] In 1920 it became the cathedral of the Armenian Apostolic Diocese of Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan.[5] It survived through the Soviet state atheist policies of the 1920s and 1930s when all but two Armenian churches in Baku were destroyed.[5]

1990 pogrom and aftermath

The large Armenian population of Baku—around 200,000 in the mid-1980s—was targeted in a January 1990 pogrom during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.[4] The city's Armenian population was forced to flee. Serious damage to the church was caused by an arson attack on December 25, 1989, but it remained standing.[6] Vazgen I, head of the Armenian Church, wrote to Yuri Khristoradnov, the chairman of the Soviet Council for Religious Affairs, in January 1990 that "extremist Azeri nationalists set fire to the Armenian Church in Baku on 25 December [1989], destroying valuable ecclesiastical books, holy paintings, and all ecclesiastical clothing."[7]

Bill Keller wrote in The New York Times in February 1990 that the church "whose congregation has been depleted over the past two years by an emigration based on fear, is now a charred ruin. A neighbor said firefighters and the police watched without intervening as vandals destroyed the building at the beginning of the year."[8] Human Rights Watch wrote in 1995: "Armenians have vanished from the streets of Baku [...] the Armenian church in Baku stand[s] empty."[9]

Current state

Thomas de Waal wrote in his 2003 book Black Garden that the church "remains a gutted shell eleven years after it was burned in December 1989; the cross has been removed from the belfry, now used as a pool hall." He also wrote that it remains the only visible Armenian monument in Baku.[4] Jason Thomson wrote in 2005 that it was "transformed into a billiard hall and tea house."[10] The library of the church consisting of 5,000 books and manuscripts has been preserved.[11][12]

In 2002 the church was transferred to the Presidential Library,[13] which is located nearby, and now houses its archive.[1][2] In 2006 Azerbaijani Minister of Culture Abulfas Garayev stated that converting the church into a library is purposeful because there are not many Armenian Christians in Azerbaijan.[14] According to Emil Sanamyan, a scholar at the USC Institute of Armenian Studies, argues that calling it a "presidential book depository" is more accurate as "library implies public access which there isn't in this case." According to Samir Huseynov it is open to PhD students and other researchers who can get access.[15]

Visits by Armenians

In April 2010 Catholicos Karekin II, the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church, visited the church and prayed and sang medieval hymns there. He expressed hope that the church will eventually "reopen its doors to believers."[16] It was the first time since 1990 that prayer was heard at the church.[17]

In April 2012 the Armenian delegation participating at a Euronest Parliamentary Assembly meeting in Baku visited the church.[18] In their visit in September 2017 the Armenian delegates found the church and its territory closed.[19][20]

Gallery

References

- notes

- ^ (Template:Lang-hy, Bak’vi Surb Grigor Lusavorich yekeghetsi; Template:Lang-az)

- references

- ^ a b Gamidov, Gamid (1 August 2011). "Толерантный Баку — часть IV: армянская церковь [Tolerant Baku - Part 4: Armenian Church]" (in Russian). Echo of Moscow. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017.

- ^ a b Musayeva, Günay (5 August 2011). "Erməni̇ Ki̇lsəsi̇ İbadətə Açilacaqmi?". Yeni Müsavat (in Azerbaijani). Musavat. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Stepanyan 2009, p. 47.

- ^ a b c de Waal 2003, p. 103.

- ^ a b Stepanyan 2009, p. 54.

- ^ Stepanyan 2009, p. 55.

- ^ "Azeris Said Destroying Armenian Monuments". Daily Report: Soviet Union. Foreign Broadcast Information Service (via Armenpress): view=1up, seq=439 79–80. 12 January 1990.

- ^ Keller, Bill (18 February 1990). "Soviet Union; A Once-Docile Azerbaijani City Bridles Under the Kremlin's Grip". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Armenia-Azerbaijan". Playing the "Communal Card": Communal Violence and Human Rights. New York: Human Rights Watch. 1995. p. 143.

- ^ Thomson, Jason (2005). In the Shadow of Aliyev: Travels in Azerbaijan. Bennett & Bloom. p. 60. ISBN 9781898948728.

...the Armenian church of Gregory the Illuminator, built in the 1860s as the centre of worship for the Armenian Diocese of Baku, but closed and transformed into a billiard hall and tea house after being damaged by arsonists during the violence against Armenians of January 1990.

- ^ Loshak, Viktor; Gyulieva, Emilia (15 July 2007). "Большой прорыв [Big breath-thru]". Ogoniok (in Russian). Kommersant. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

Мы же были поражены и тронуты, когда в бакинской библиотеке, которая расположена сейчас в бывшей армянской церкви, обнаружили хранящимися 5 тысяч томов на армянском языке.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Huseynov, Rizvan (6 July 2016). "В Баку предлагают открыть для богослужения армянскую церковь св. Григориса Лусаворича". rizvanhuseynov.com (in Russian).

В репортаже на телеканале ATV также выдвинута идея открыть для богослужения армянскую церковь св.Григориса Лусаворича в Баку, которая отреставрирована засчет государства и в ней хранятся сотни армянских книг и рукописей.

- ^ "Армянская церковь в Баку, возможно, станет библиотекой". blagovest-info.ru (in Russian). Agency of Religious Information «Blagovest-Info». 19 April 2006. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017.

- ^ "Armenian Church in Baku May Be Converted to Library". Asbarez. (via Armenpress). 20 April 2006.

- ^ https://twitter.com/emil_sanamyan/status/911609299939610624

- ^ "Armenia Church Leader Meets Azerbaijani President". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 27 April 2010.

- ^ "After decades Armenian prayer and Armenian church psalm was heard in the Baku St. Grigor Lusavorich Armenian Church". Armenpress. 27 April 2010.

- ^ "Հայկական պատվիրակությունը Բաքվում այցելել է Սուրբ Գրիգոր Լուսավորիչ եկեղեցի [Armenian delegation visited Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church in Baku]". hayernaysor.am (in Armenian). Armenian Ministry of Diaspora (via Armenpress). 5 April 2012. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Yerevan delegates banned from entering Armenian Church in Baku, territory closed". Armenpress. 23 September 2017.

- ^ "Armenia MPs not permitted to enter Armenian church in Baku". news.am. 23 September 2017.

Bibliography

- de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1945-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stepanyan, G. S. (2009). "Համառոտ ակնարկ Բաքվի Սբ. Գրիգոր Լուսավորիչ եկեղեցու պատմության [A Brief Review of the History of St.Gregory the Illuminator Church in Baku]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian) (3): 45–59.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Religious organizations established in 1887

- Armenian Apostolic churches

- Armenian churches in Azerbaijan

- Former churches

- Former places of worship in Azerbaijan

- Oriental Orthodox congregations established in the 19th century

- Religious organizations disestablished in the 20th century

- 19th-century churches

- Churches in Baku

- 1869 establishments in the Russian Empire

- 1989 disestablishments in Azerbaijan

- Churches completed in 1869