Atmosphere of Venus

| Atmosphere of Venus | |

|---|---|

| |

|

Cloud structure in Venus's atmosphere in 1979, | |

| General information[1] | |

| Height | 250 km |

| Average surface pressure | (92 bar or) 9.2 MPa |

| Mass | 4.8 kg |

| Composition[1][2] | |

| Carbon dioxide | 96.5% |

| Nitrogen | 3.5% |

| Sulfur dioxide | 150 ppm |

| Argon | 70 ppm |

| Water vapour | 20 ppm |

| Carbon monoxide | 17 ppm |

| Helium | 12 ppm |

| Neon | 7 ppm |

| Hydrogen chloride | 0.1–0.6 ppm |

| Hydrogen fluoride | 0.001–0.005 ppm |

The atmosphere of Venus is much denser and hotter than that of Earth. The temperature at the surface is 740 K (467 °C, 872 °F), while the pressure is 93 bar.[1] The Venusian atmosphere supports opaque clouds made of sulfuric acid, making optical Earth-based and orbital observation of the surface impossible. Information about the topography has been obtained exclusively by radar imaging.[1] The main atmospheric gases are carbon dioxide and nitrogen. Other chemical compounds are present only in trace amounts.[1]

Mikhail Lomonosov was the first person to hypothesize the existence of an atmosphere on Venus based on his observation of the transit of Venus of 1761 in a small observatory near his house in Saint Petersburg.[3]

The atmosphere is in a state of vigorous circulation and super-rotation.[4] The whole atmosphere circles the planet in just four Earth days, much faster than the planet's sidereal day of 243 days. The winds supporting super-rotation blow as fast as 100 m/s (~360 km/h or 220 mph).[4] Winds move at up to 60 times the speed of the planet's rotation, while Earth's fastest winds are only 10% to 20% rotation speed.[5] On the other hand, the wind speed becomes increasingly slower as the elevation from the surface decreases, with the breeze barely reaching the speed of 10 km/h on the surface.[6] Near the poles are anticyclonic structures called polar vortices. Each vortex is double-eyed and shows a characteristic S-shaped pattern of clouds.[7]

Unlike Earth, Venus lacks a magnetic field. Its ionosphere separates the atmosphere from outer space and the solar wind. This ionised layer excludes the solar magnetic field, giving Venus a distinct magnetic environment. This is considered Venus's induced magnetosphere. Lighter gases, including water vapour, are continuously blown away by the solar wind through the induced magnetotail.[4] It is speculated that the atmosphere of Venus up to around 4 billion years ago was more like that of the Earth with liquid water on the surface. A runaway greenhouse effect may have been caused by the evaporation of the surface water and subsequent rise of the levels of other greenhouse gases.[8][9]

Despite the harsh conditions on the surface, the atmospheric pressure and temperature at about 50 km to 65 km above the surface of the planet is nearly the same as that of the Earth, making its upper atmosphere the most Earth-like area in the Solar System, even more so than the surface of Mars. Due to the similarity in pressure and temperature and the fact that breathable air (21% oxygen, 78% nitrogen) is a lifting gas on Venus in the same way that helium is a lifting gas on Earth, the upper atmosphere has been proposed as a location for both exploration and colonization.[10]

On January 29, 2013, ESA scientists reported that the ionosphere of the planet Venus streams outwards in a manner similar to "the ion tail seen streaming from a comet under similar conditions."[11][12]

Structure and composition

Composition

The atmosphere of Venus is composed mainly of carbon dioxide, along with a small amount of nitrogen and other trace elements. The amount of nitrogen in the atmosphere is relatively small compared to the amount of carbon dioxide, but because the atmosphere is so much thicker than that on Earth, its total nitrogen content is roughly four times higher than Earth's, even though on Earth nitrogen makes up about 78% of the atmosphere.[1][13]

The atmosphere contains a range of interesting compounds in small quantities, including some based on hydrogen, such as hydrogen chloride (HCl) and hydrogen fluoride (HF). There are carbon monoxide, water vapour and molecular oxygen as well.[2][4] Hydrogen is in relatively short supply in the Venusian atmosphere. A large amount of the planet's hydrogen is theorised to have been lost to space,[14] with the remainder being mostly bound up in sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S). The loss of significant amounts of hydrogen is proved by a very high D/H ratio measured in the Venusian atmosphere.[4] The ratio is about 0.025, which is much higher than the terrestrial value of 1.6×10−4.[2] In addition, in the upper atmosphere of Venus D/H ratio is 1.5 higher than in the bulk atmosphere.[2]

Troposphere

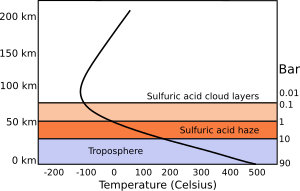

The atmosphere is divided into a number of sections depending on altitude. The densest part of the atmosphere, the troposphere, begins at the surface and extends upwards to 65 km. At the furnace-like surface the winds are slow,[1] but at the top of the troposphere the temperature and pressure reaches Earth-like levels and clouds pick up speed to 100 m/s.[4][15]

The atmospheric pressure at the surface of Venus is about 92 times that of the Earth, similar to the pressure found 910 metres below the surface of the ocean. The atmosphere has a mass of 4.8×1020 kg, about 93 times the mass of the Earth's total atmosphere. The density of the air at the surface is 67 kg/m3, which is 6.5% that of liquid water on Earth.[1] The pressure found on Venus's surface is high enough that the carbon dioxide is technically no longer a gas, but a supercritical fluid. This supercritical carbon dioxide forms a kind of sea that covers the entire surface of Venus. This sea of supercritical carbon dioxide transfer heats very efficiently, buffering the temperature changes between night and day (which last 56 terrestrial days).[16]

The large amount of CO2 in the atmosphere together with water vapour and sulfur dioxide create a strong greenhouse effect, trapping solar energy and raising the surface temperature to around 740 K (467 °C),[13] hotter than any other planet in the solar system, even that of Mercury despite being located farther out from the Sun and receiving only 25% of the solar energy (per unit area) Mercury does.[citation needed] The average temperature on the surface is above the melting points of lead 600 K (327 °C), tin 505 K (232 °C), and zinc 693 K (420 °C). The thick troposphere also makes the difference in temperature between the day and night side small, even though the slow retrograde rotation of the planet causes a single solar day to last 116.5 days on Earth. The surface of Venus spends 58.3 days of darkness before the sun rises again behind the clouds.[1]

The troposphere on Venus contains 99% of the atmosphere by mass. Ninety percent of the atmosphere of Venus is within 28 km of the surface; by comparison, 90% of the atmosphere of Earth is within 10 km of the surface. At a height of 50 km the atmospheric pressure is approximately equal to that at the surface of Earth.[17] On the night side of Venus clouds can still be found at 80 km above the surface.[18]

The altitude of the troposphere most similar to Earth is near the tropopause—the boundary between troposphere and mesosphere. It is located slightly above 50 km.[15] According to measurements by the Magellan and Venus Express probes, the altitude from 52.5 to 54 km has a temperature between 293 K (20 °C) and 310 K (37 °C), and the altitude at 49.5 km above the surface is where the pressure becomes the same as Earth at sea level.[15][19] As manned ships sent to Venus would be able to compensate for differences in temperature to a certain extent, anywhere from about 50 to 54 km or so above the surface would be the easiest altitude in which to base an exploration or colony, where the temperature would be in the crucial "liquid water" range of 273 K (0 °C) to 323 K (50 °C) and the air pressure the same as habitable regions of Earth.[10][20] As CO2 is heavier than air, the colony's air (nitrogen and oxygen) could keep the structure floating at that altitude like a dirigible.

Circulation

The circulation in Venus's troposphere follows the so-called cyclostrophic approximation.[4] Its windspeeds are roughly determined by the balance of the pressure gradient and centrifugal forces in almost purely zonal flow. In contrast, the circulation in the Earth's atmosphere is governed by the geostrophic balance.[4] Venus's windspeeds can be directly measured only in the upper troposphere (tropopause), between 60–70 km, altitude, which corresponds to the upper cloud deck.[21] The cloud motion is usually observed in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum, where the contrast between clouds is the highest.[21] The linear wind speeds at this level are about 100 ± 10 m/s at lower than 50° latitude. They are retrograde in the sense that they blow in the direction of the retrograde rotation of the planet.[21] The winds quickly decrease towards the higher latitudes, eventually reaching zero at the poles. Such strong cloud-top winds cause a phenomenon known as the super-rotation of the atmosphere.[4] In other words, these high-speed winds circle the whole planet faster than the planet itself rotates.[20] The super-rotation on Venus is differential, which means that the equatorial troposphere super-rotates more slowly than the troposphere at the midlatitudes.[21] The winds also have a strong vertical gradient. They decline deep in the troposphere with the rate of 3 m/s per km.[4] The winds near the surface of Venus are much slower than that on Earth. They actually move at only a few kilometres per hour (generally less than 2 m/s and with an average of 0.3 to 1.0 m/s), but due to the high density of the atmosphere at the surface, this is still enough to transport dust and small stones across the surface, much like a slow-moving current of water.[1][22]

All winds on Venus are ultimately driven by convection.[4] Hot air rises in the equatorial zone, where solar heating is concentrated, and flows to the poles. Such an almost-planetwide overturning of the troposphere is called Hadley circulation.[4] However, the meridional air motions are much slower than zonal winds. The poleward limit of the planet wide Hadley cell on Venus is near ±60° latitudes.[4] Here air starts to descend and returns to the equator below the clouds. This interpretation is supported by the distribution of the carbon monoxide, which is also concentrated in the vicinity of ±60° latitudes.[4] Poleward of the Hadley cell a different pattern of circulation is observed. In the latitude range 60°–70° cold polar collars exist.[4][7] They are characterised by temperatures about 30–40 K lower than in the upper troposphere at nearby latitudes.[7] The lower temperature is probably caused by the upwelling of the air in them and by the resulting adiabatic cooling.[7] Such an interpretation is supported by the denser and higher clouds in the collars. The clouds lie at 70–72 km altitude in the collars—about 5 km higher than at the poles and low latitudes.[4] A connection may exist between the cold collars and high speed midlatitude jets in which winds blow as fast as 140 m/s. Such jets are a natural consequence of the Hadley–type circulation and should exist on Venus between 55–60° latitude.[21]

Odd structures known as polar vortices lie within the cold polar collars.[4] They are giant hurricane-like storms four times larger than their terrestrial analogs. Each vortex has two "eyes"—the centres of rotation, which are connected by distinct S-shaped cloud structures. Such double eyed structures are also called polar dipoles.[7] Vortexes rotate with the period of about 3 days in the direction of general super-rotation of the atmosphere.[7] The linear wind speeds are 35–50 m/s near their outer edges and zero at the poles.[7] The temperature at the cloud-tops in the polar vortexes are much higher than in the nearby polar collars reaching 250 K (−23 °C).[7] The conventional interpretation of the polar vortexes is that they are anticyclones with downwelling in the centre and upwelling in the cold polar collars.[4] This type of circulation resembles the winter polar anticyclonic vortexes on Earth, especially the one found over Antarctica. The observations in the various infrared atmospheric windows indicate that the anticyclonic circulation observed near the poles may penetrate as deep as to 50 km altitude, i.e. to the base of the clouds.[7] The polar upper troposphere and mesosphere are extremely dynamic; large bright clouds may appear and disappear over the space of a few hours. One such event was observed by Venus Express between 9 and 13 January 2007, when the south polar region became brighter by 30%.[21] This event was probably caused by an injection of sulfur dioxide into the mesosphere, which then condensed forming a bright haze.[21] The two eyes in the vortexes have yet to be explained.[23]

The first vortex on Venus was discovered at the north pole by the Pioneer Venus mission in 1978.[24] A discovery of the second large 'double-eyed' vortex at the south pole of Venus was made in the summer of 2006 by Venus Express, which came with no surprise.[23]

Upper atmosphere and ionosphere

The mesosphere of Venus extends from 65 km to 120 km in height, and the thermosphere begins at around 120, eventually reaching the upper limit of the atmosphere (exosphere) at about 220 to 350 km.[15] The exosphere is the altitude at which the atmosphere becomes collisionless.

The mesosphere of Venus can be divided into two layers: the lower one between 62–73 km[25] and the upper one between 73–95 km.[15] In the first layer the temperature is nearly constant at 230 K (−43 °C). This layer coincides with the upper cloud deck. In the second layer temperature starts to decrease again reaching about 165 K (−108 °C) at the altitude of 95 km, where mesopause begins.[15] It is the coldest part of the Venusian dayside atmosphere.[2] In the dayside mesopause, which serves as a boundary between the mesophere and thermosphere and is located between 95–120 km, temperature grows up to a constant—about 300–400 K (27–127 °C)—value prevalent in the thermosphere.[2] In contrast the nightside Venusian thermosphere is the coldest place on Venus with temperature as low as 100 K (−173 °C). It is even called a cryosphere.[2]

The circulation patterns in the upper mesosphere and thermosphere of Venus are completely different from those in the lower atmosphere.[2] At altitudes 90–150 km the Venusian air moves from the dayside to nightside of the planet, with upwelling over sunlit hemisphere and downwelling over dark hemisphere. The downwelling over the nightside causes adiabatic heating of the air, which forms a warm layer in the nightside mesosphere at the altitudes 90–120 km.[2] The temperature of this layer—230 K (−43 °C) is far higher than the typical temperature found in the nightside thermosphere—100 K (−173 °C).[2] The air circulated from the dayside also carries oxygen atoms, which after recombination form excited molecules of oxygen in the long-lived singlet state (1Δg), which then relax and emit infrared radiation at the wavelength 1.27 μm. This radiation from the altitude range 90–100 km is often observed from the ground and spacecraft.[26] The nightside upper mesosphere and thermosphere of Venus is also the source of non-LTE (non-local thermodynamic equilibrium) emissions of CO2 and NO molecules, which are responsible for the low temperature of the nightside thermosphere.[26]

The Venus Express probe has shown through stellar occultation that the atmospheric haze extends much further up on the night side than the day side. On the day side the cloud deck has a thickness of 20 km and extends up to about 65 km, whereas on the night side the cloud deck in the form of a thick haze reaches up to 90 km in altitude—well into mesosphere, continuing even further to 105 km as a more transparent haze.[18] In 2011, the spacecraft discovered that Venus has a thin ozone layer at an altitude of 100 km.[27]

Venus has an extended ionosphere located at altitudes 120–300 km.[15] The ionosphere almost coincides with the thermosphere. The high levels of the ionisation are maintained only over the dayside of the planet. Over the nightside the concentration of the electrons is almost zero.[15] The ionosphere of Venus consists of three layers: v1 between 120 and 130 km, v2 between 140 and 160 km and v3 between 200 and 250 km.[15] There may be an additional layer near 180 km. The maximum electron volume density (number of electrons in a unit of volume) 3×1011 m−3 is reached in the v2 layer near the subsolar point.[15] The upper boundary of the ionosphere—ionopause is located at altitudes 220–375 km and separates the plasma of the planetary origin from that of the induced magnetosphere.[28][29] The main ionic species in the v1 and v2 layers is O2+ ion, whereas the v3 layer consists of O+ ions.[15] The ionospheric plasma is observed to be in motion; solar photoionization on the dayside, and ion recombination on the nightside, are the processes mainly responsible for accelerating the plasma to the observed velocities. The plasma flow appears to be sufficient to maintain the nightside ionosphere at or near the observed median level of ion densities.[30]

Induced magnetosphere

Venus is known not to have a magnetic field.[28][29] The reason for its absence is not clear, but is probably related to the planet's slow rotation or the lack of convection in the mantle. Venus only has an induced magnetosphere formed by the Sun's magnetic field carried by the solar wind.[28] This process can be understood as the field lines wrapping around an obstacle—Venus in this case. The induced magnetosphere of Venus has a bow shock, magnetosheath, magnetopause and magnetotail with the current sheet.[28][29]

At the subsolar point the bow shock stands 1900 km (0.3 Rv, where Rv is the radius of Venus) above the surface of Venus. This distance was measured in 2007 near the solar activity minimum.[29] Near the solar activity maximum it can be several times further from the planet.[28] The magnetopause is located at the altitude of 300 km.[29] The upper boundary of the ionosphere (ionopause) is near 250 km. Between the magnetopause and ionopause there exists a magnetic barrier—a local enhancement of the magnetic field, which prevents solar plasma from penetrating deeper into the Venusian atmosphere, at least near solar activity minimum. The magnetic field in the barrier reaches up to 40 nT.[29] The magnetotail continues up to ten radiuses from the planet. It is the most active part of the Venusian magnetosphere. There are reconnection events and particle acceleration in the tail. The energies of electrons and ions in the magnetotail are around 100 eV and 1000 eV respectively.[31]

Due to the lack of the intrinsic magnetic field on Venus, the solar wind penetrates relatively deep into the planetary exosphere and causes substantial atmosphere loss.[32] The loss happens mainly via the magnetotail. Currently the main ion types being lost are O+, H+ and He+. The ratio of hydrogen to oxygen losses is around 2 (i.e. almost stoichiometric) indicating the ongoing loss of water.[31]

Clouds

Venusian clouds are thick and are composed of sulfur dioxide and droplets of sulfuric acid.[33] These clouds reflect about 75%[34] of the sunlight that falls on them, which is what obscures the surface of Venus from regular imaging.[1] The reflectivity of the clouds causes the amount of light reflected upward to be nearly the same as that coming in from above, and a probe exploring the cloud tops could harness solar energy almost as well from below as above, enabling solar cells to be fitted just about anywhere.[35] Because the clouds are reflecting almost all of the sunlight that hits them, Venus has a higher geometric albedo than the other seven planets in the Solar System.

The cloud cover is such that very little sunlight can penetrate down to the surface, and the light level is only around 5,000–10,000 lux with a visibility of three kilometres. At this level little to no solar energy could conceivably be collected by a probe. Humidity at this level is less than 0.1%.[36] In fact, due to the thick, highly reflective cloud cover the total solar energy received by the planet is less than that of the Earth.

Sulfuric acid is produced in the upper atmosphere by the sun's photochemical action on carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and water vapour. Ultraviolet photons of wavelengths less than 169 nm can photodissociate carbon dioxide into carbon monoxide and atomic oxygen. Atomic oxygen is highly reactive; when it reacts with sulfur dioxide, a trace component of the Venusian atmosphere, the result is sulfur trioxide, which can combine with water vapour, another trace component of Venus's atmosphere, to yield sulfuric acid.

Venus's sulfuric acid rain never reaches the ground, but is evaporated by the heat before reaching the surface in a phenomenon known as virga.[37] It is theorized that early volcanic activity released sulfur into the atmosphere and the high temperatures prevented it from being trapped into solid compounds on the surface as it was on the Earth.[38]

The clouds of Venus are capable of producing lightning much like the clouds on Earth.[39] The existence of lightning had been controversial since the first suspected bursts were detected by the Soviet Venera probes. However in 2006–2007 Venus Express was reported to detect whistler mode waves, which were attributed to lightning. Their intermittent appearance indicates a pattern associated with weather activity. The lightning rate is at least half of that on Earth.[39]

In 2009 a prominent bright spot in the atmosphere was noted by an amateur astronomer and photographed by Venus Express. Its cause is currently unknown, with surface volcanism advanced as a possible explanation.[40]

Possibility of life

Due to the harsh conditions on the surface, little of the planet has been explored; in addition to the fact that life as currently understood may not necessarily be the same in other parts of the universe, the extent of the tenacity of life on Earth itself has not yet been shown. Creatures known as extremophiles exist on Earth, preferring extreme habitats. Thermophiles and hyperthermophiles thrive at temperatures reaching above the boiling point of water, acidophiles thrive at a pH level of 3 or below, polyextremophiles can survive a varied number of extreme conditions, and many other types of extremophiles exist on Earth.[41] However, the surface temperature of Venus (over 450 °C) is far beyond the extremophile range, which extends only tens of degrees beyond 100 °C.

However, life could also exist outside the extremophile range in the cloudtops. It has been proposed that life on Venus could exist there, the same way that bacteria have been found living and reproducing in clouds on Earth.[42] Microbes in the thick, cloudy atmosphere could be protected from solar radiation by the sulfur compounds in the air.[41] The solar wind may provide a mechanism for the transfer of such microbiota from Venus to Earth.[43]

The Venusian atmosphere has been found to be sufficiently out of equilibrium as to require further investigation.[41] Analysis of data from the Venera, Pioneer, and Magellan missions has found the chemicals hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) together in the upper atmosphere, as well as carbonyl sulfide (OCS). The first two gases react with each other, implying that something must produce them. In addition, carbonyl sulfide is noteworthy for being exceptionally difficult to produce through inorganic means.[42] Furthermore, one of the early Venera probes detected large amounts of chlorine just below the Venusian cloud deck.[44]

It has been proposed that microbes at this level could be soaking up ultraviolet light from the Sun as a source of energy, which could be a possible explanation for dark patches seen on UV images of the planet.[45][46] Large, non-spherical cloud particles have also been detected in the cloud decks. Their composition is still unknown.[41]

Between the years 1937 to 1961 six invasions of ultra rapid liquifying bacteria appeared in rain-water at the Norman Lockyer Observatory at Sidmouth England. The initial onsets of these "invasions" occurred on average 59 ± 17 days following near-dated geomagnetic storms to Venus inferior conjunctions. The author of the report describing these events came to speculate that the bacteria may have originated in the cloud tops of Venus and were transported to earth by the solar wind.[47]

Evolution

Through studies of the present cloud structure and geology of the surface combined with the fact that the luminosity of the Sun has increased by 25% since around 3.8 billion years ago,[48] it is thought that the atmosphere of Venus up to around 4 billion years ago was more like that of Planet Earth with liquid water on the surface. The runaway greenhouse effect may have been caused by the evaporation of the surface water and the rise of the levels of greenhouse gases that followed. Venus's atmosphere has therefore received a great deal of attention from those studying climate change on Earth.[8]

There are no geologic forms on the planet to suggest the presence of water over the past billion years. However there is no reason to suppose that Venus was an exception to the processes that formed Earth and gave it its water during its early history, possibly from the original rocks that formed the planet or later on from comets. The common view among research scientists is that water would have existed for about 600 million years on the surface before evaporating, though some such as David Grinspoon believe that up to 2 billion years could also be plausible.[49]

The early Earth during the Hadean eon is believed by most scientists to have had a Venus-like atmosphere, with roughly 100 bar of CO2 and a surface temperature of 230 °C, and possibly even sulfuric acid clouds, until about 4.0 billion years ago, by which time plate tectonics were in full force and together with the early water oceans, removed the CO2 and sulfur from the atmosphere.[50] Early Venus would thus most likely have had water oceans like the Earth, but any plate tectonics would have ended when Venus lost its oceans[citation needed]. Its surface is estimated to be about 500 million years old, so it would not be expected to show evidence of plate tectonics.[51]

Observations and measurement from Earth

In 1761, Russian polymath Mikhail Lomonosov observed an arc of light surrounding the part of Venus off the Sun's disc at the beginning of the egress phase of the transit and concluded that Venus has an atmosphere.[52][53] In 1940, Rupert Wildt calculated that the amount of CO2 in the Venusian atmosphere would raise surface temperature above the boiling point for water.[54] This was confirmed when Mariner 2 made radiometer measurements of the temperature in 1962. In 1967, Venera 4 confirmed that the atmosphere consisted primarily of carbon dioxide.[54]

The upper atmosphere of Venus can be measured from Earth when the planet crosses the sun in a rare event known as a solar transit. The last solar transit of Venus occurred in 2012. Using quantitative astronomical spectroscopy, scientists were able to analyse sunlight that passed through the planet's atmosphere to reveal chemicals within it. As the technique to analyse light to discover information about a planet's atmosphere only first showed results in 2001,[55] this was the first opportunity to gain conclusive results in this way on the atmosphere of Venus since observation of solar transits began. This solar transit was a rare opportunity considering the lack of information on the atmosphere between 65 and 85 km.[56] The solar transit in 2004 enabled astronomers to gather a large amount of data useful not only in determining the composition of the upper atmosphere of Venus, but also in refining techniques used in searching for extrasolar planets. The atmosphere of mostly CO2, absorbs near-infrared radiation, making it easy to observe. During the 2004 transit, the absorption in the atmosphere as a function of wavelength revealed the properties of the gases at that altitude. The Doppler shift of the gases also enabled wind patterns to be measured.[57]

A solar transit of Venus is an extremely rare event, and the last solar transit of the planet before 2004 was in 1882. The most recent solar transit was in 2012, however, the next one will not occur until 2117.[56][57]

Future exploration

The Venus Express spacecraft is now in orbit around the planet, probing deeper into the atmosphere using infrared imaging spectroscopy in the 1–5 µm spectral range.[4] The JAXA probe Akatsuki which was launched in May 2010 was intended to study the planet for a period of two years, including the structure and activity of the atmosphere, but it failed to enter Venus orbit in December 2010. A second attempt to achieve orbit will take place in 2015. One of its five cameras known as the "IR2" will be able to measure the atmosphere of the planet underneath its thick clouds, in addition to its movement and distribution of trace components. With a varied orbit from 300 to 60,000 km, it will be able to take close-up photographs of the planet, and should also confirm the presence of both active volcanoes as well as lightning.[58]

The Venus In-Situ Explorer, proposed by NASA's New Frontiers program is a proposed probe which would aid in understanding the processes on the planet that led to climate change, as well as paving the way towards a later sample return mission.[59]

Another craft called the Venus Mobile Explorer has been proposed by the Venus Exploration Analysis Group (VEXAG) to study the composition and isotopic measurements of the surface and the atmosphere, for about 90 days. A launch date has not yet been set.[60]

Proposed missions

After missions discovered the reality of the harsh nature of the planet's surface, attention shifted towards other targets such as Mars. There have been a number of proposed missions recently however, and many of these involve the little-known upper atmosphere. The Soviet Vega program in 1985 dropped two balloons into the atmosphere, but these were battery-powered and lasted for only about two Earth days each before running out of power and since then there has been no exploration of the upper atmosphere. In 2002 the NASA contractor Global Aerospace proposed a balloon that would be capable of staying in the upper atmosphere for hundreds of Earth days as opposed to two.[61]

A solar flyer has also been proposed by Geoffrey A. Landis in place of a balloon,[20] and the idea has been featured from time to time since the early 2000s. Venus has a high albedo, and reflects most of the sunlight that shines on it making the surface quite dark, the upper atmosphere at 60 km has an upward solar intensity of 90%, meaning that solar panels on both the top and the bottom of a craft could be used with nearly equal efficiency.[35] In addition to this, the slightly lower gravity, high air pressure and slow rotation allowing for perpetual solar power make this part of the planet ideal for exploration. The proposed flyer would operate best at an altitude where sunlight, air pressure, and wind speed would enable it to remain in the air perpetually, with slight dips down to lower altitudes for a few hours at a time before returning to higher altitudes. As sulfuric acid in the clouds at this height is not a threat for a properly shielded craft, this so-called "solar flyer" would be able to measure the area in between 45 km and 60 km indefinitely, as long as mechanical error or unforeseen problems do not cause it to fail. Landis also proposed that rovers similar to Spirit and Opportunity could possibly explore the surface, with the difference being that Venus surface rovers would be "dumb" rovers controlled by radio signals from computers located in the flyer above,[62] only requiring parts such as motors and transistors to withstand the surface conditions, but not weaker parts involved in microelectronics that could not be made resistant to the heat, pressure and acidic conditions.[63]

Russian space plan for 2006–2015 involves a launch of Venera-D (Venus-D) probe around 2024.[64] The main scientific goals of the Venera-D mission are investigation of the structure and chemical composition of the atmosphere and investigation of the upper atmosphere, ionosphere, electrical activity, magnetosphere and escape rate.[65]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Basilevsky, Alexandr T.; Head, James W. (2003). "The surface of Venus". Rep. Prog. Phys. 66 (10): 1699–1734. Bibcode:2003RPPh...66.1699B. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/66/10/R04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bertaux, Jean-Loup; Vandaele, Ann-Carine; Korablev, Oleg; Villard, E.; Fedorova, A.; Fussen, D.; Quémerais, E.; Belyaev, D.; Mahieux, A. (2007). "A warm layer in Venus' cryosphere and high-altitude measurements of HF, HCl, H2O and HDO". Nature. 450 (7170): 646–649. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..646B. doi:10.1038/nature05974. PMID 18046397.

- ^ Shiltsev, Vladimir (March 2014). "The 1761 Discovery of Venus' Atmosphere: Lomonosov and Others". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 17 (1): 85–112. Bibcode:2014JAHH...17...85S.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Svedhem, Hakan; Titov, Dmitry V.; Taylor, Fredric V.; Witasse, Oliver (2007). "Venus as a more Earth-like planet". Nature. 450 (7170): 629–632. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..629S. doi:10.1038/nature06432. PMID 18046393.

- ^ Dennis Normile (2010). "Mission to probe Venus's curious winds and test solar sail for propulsion". Science. 328 (5979): 677. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..677N. doi:10.1126/science.328.5979.677-a. PMID 20448159.

- ^ DK Space Encyclopedia: Atmosphere of Venus p 58.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Piccioni, G.; Drossart, P.; Sanchez-Lavega, A.; Hueso, R.; Taylor, F. W.; Wilson, C. F.; Grassi, D.; Zasova, L.; Moriconi, M. (2007). "South-polar features on Venus similar to those near the north pole". Nature. 450 (7170): 637–640. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..637P. doi:10.1038/nature06209. PMID 18046395.

- ^ a b Kasting, J.F. (1988). "Runaway and moist greenhouse atmospheres and the evolution of Earth and Venus". Icarus. 74 (3): 472–494. Bibcode:1988Icar...74..472K. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90116-9. PMID 11538226.

- ^ "How Hot is Venus?". May 2006.

- ^ a b Landis, Geoffrey A. (2003). "Colonization of Venus". AIP Conf. Proc. 654 (1): 1193–1198. Bibcode:2003AIPC..654.1193L. doi:10.1063/1.1541418.

- ^ "When A Planet Behaves Like A Comet". ESA. January 29, 2013. Retrieved 2013-01-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Kramer, Miriam (January 30, 2013). "Venus Can Have 'Comet-Like' Atmosphere". Space.com. Retrieved 2013-01-31.

- ^ a b "Clouds and atmosphere of Venus". Institut de mécanique céleste et de calcul des éphémérides. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ^ Lovelock, James (1979). Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-286218-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Patzold, M.; Hausler, B.; Bird, M.K.; Tellmann, S.; Mattei, R.; Asmar, S. W.; Dehant, V.; Eidel, W.; Imamura, T. (2007). "The structure of Venus' middle atmosphere and ionosphere". Nature. 450 (7170): 657–660. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..657P. doi:10.1038/nature06239. PMID 18046400.

- ^ Fegley, B.; et al. (1997). Geochemistry of Surface-Atmosphere Interactions on Venus (Venus II: Geology, Geophysics, Atmosphere, and Solar Wind Environment). University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-81-651830-0.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author2=(help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Flying over the cloudy world – science updates from Venus Express". Venus Today. 2006-07-12. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ "Venus Atmosphere Temperature and Pressure Profiles". Shade Tree Physics. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Landis, Geoffrey A.; Colozza, Anthony; LaMarre, Christopher M. "Atmospheric Flight on Venus" (PDF). Proceedings. 40th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit sponsored by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Reno, Nevada, January 14–17, 2002. pp. IAC–02–Q.4.2.03, AIAA-2002-0819, AIAA0.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Markiewicz, W.J.; Titov, D.V.; Limaye, S.S.; Keller, H. U.; Ignatiev, N.; Jaumann, R.; Thomas, N.; Michalik, H.; Moissl, R. (2007). "Morphology and dynamics of the upper cloud layer of Venus". Nature. 450 (7170): 633–636. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..633M. doi:10.1038/nature06320. PMID 18046394.

- ^ Moshkin, B.E.; Ekonomov; Golovin (1979). "Dust on the surface of Venus". Kosmicheskie Issledovaniia (Cosmic Research). 17: 280–285. Bibcode:1979KosIs..17..280M.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Double vortex at Venus South Pole unveiled!". European Space Agency. 2006-06-27. Archived from the original on 7 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Emily Lakdawalla (2006-04-14). "First Venus Express VIRTIS Images Peel Away the Planet's Clouds". Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ This thickness correspond to the polar latitudes. It is narrower near the equator—65–67 km.

- ^ a b Drossart, P.; Piccioni, G.; Gerard, G.C.; Lopez-Valverde, M. A.; Sanchez-Lavega, A.; Zasova, L.; Hueso, R.; Taylor, F. W.; Bézard, B. (2007). "A dynamic upper atmosphere of Venus as revealed by VIRTIS on Venus Express". Nature. 450 (7170): 641–645. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..641D. doi:10.1038/nature06140. PMID 18046396.

- ^ Carpenter, Jennifer (7 October 2011). "Venus springs ozone layer surprise". BBC. Retrieved 2011-10-08.

- ^ a b c d e Russell, C.T. (1993). "Planetary Magnetospheres". Rep. Prog. Phys. 56 (6): 687–732. Bibcode:1993RPPh...56..687R. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/56/6/001.

- ^ a b c d e f Zhang, T.L.; Delva, M.; Baumjohann, W.; Auster, H.-U.; Carr, C.; Russell, C. T.; Barabash, S.; Balikhin, M.; Kudela, K. (2007). "Little or no solar wind enters Venus' atmosphere at solar minimum". Nature. 450 (7170): 654–656. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..654Z. doi:10.1038/nature06026. PMID 18046399.

- ^ Whitten, R. C.; McCormick, P. T.; Merritt, David; Thompson, K. W.; Brynsvold, R.R.; Eich, C.J.; Knudsen, W.C.; Miller, K.L.; et al. (November 1984). "Dynamics of the Venus ionosphere: A two-dimensional model study". Icarus. 60 (2): 317–326. Bibcode:1984Icar...60..317W. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(84)90192-1.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first4=(help) - ^ a b Barabash, S.; Fedorov, A.; Sauvaud, J.J.; Lundin, R.; Russell, C. T.; Futaana, Y.; Zhang, T. L.; Andersson, H.; Brinkfeldt, K. (2007). "The loss of ions from Venus through the plasma wake". Nature. 450 (7170): 650–653. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..650B. doi:10.1038/nature06434. PMID 18046398.

- ^ 2004 Venus Transit information page, Venus Earth and Mars, NASA

- ^ Krasnopolsky, V.A.; Parshev V.A. (1981). "Chemical composition of the atmosphere of Venus". Nature. 292 (5824): 610–613. Bibcode:1981Natur.292..610K. doi:10.1038/292610a0.

- ^ This is the spherical albedo. The geometrical albedo is 85%.

- ^ a b Landis, Geoffrey A. (2001). "Exploring Venus by Solar Airplane". AIP Conference Proceedings. 522. American Institute of Physics: 16–18. Bibcode:2001AIPC..552...16L. doi:10.1063/1.1357898.

- ^ Koehler, H. W. (1982). "Results of the Venus sondes Venera 13 and 14". Sterne und Weltraum. 21: 282. Bibcode:1982S&W....21..282K.

- ^ "Planet Venus: Earth's 'evil twin'". BBC News. 7 November 2005.

- ^ "The Environment of Venus". hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ a b Russell, C.T.; Zhang, T.L.; Delva, M.; Magnes, W.; Strangeway, R. J.; Wei, H. Y. (2007). "Lightning on Venus inferred from whistler-mode waves in the ionosphere". Nature. 450 (7170): 661–662. Bibcode:2007Natur.450..661R. doi:10.1038/nature05930. PMID 18046401.

- ^ "Experts puzzled by spot on Venus". BBC News. 1 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d Cockell, Charles S (1999). "Life on Venus". Plan. Space Sci. 47 (12): 1487–1501. Bibcode:1999P&SS...47.1487C. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(99)00036-7.

- ^ a b Landis, Geoffrey A. (2003). "Astrobiology: the Case for Venus". J. of the British Interplanetary Society. 56 (7/8): 250–254. Bibcode:2003JBIS...56..250L.

- ^ Wickramasinghe, N. C.; Wickramasinghe, J. T. (2008). "On the possibility of microbiota transfer from Venus to Earth". Astrophysics and Space Science. 317 (1–2): 133–137. Bibcode:2008Ap&SS.317..133W. doi:10.1007/s10509-008-9851-2.

- ^ Grinspoon, David (1998). Venus Revealed: A New Look Below the Clouds of Our Mysterious Twin Planet. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Pub. ISBN 978-0-201-32839-4.

- ^ "Venus could be a haven for life". ABC News. 2002-09-28.

- ^ "Acidic clouds of Venus could harbour life". NewScientist.com. 2002-09-26.

- ^ Barber, Donald (1963). "Invasion by Washing Water". Perspective. 5 (4). Focal Press, London, New York.: 201–208.

- ^ Newman, M.J.; Rood, R. T. (1977). "Implications of solar evolution for the Earth's early atmosphere". Science. 198 (4321): 1035–1037. Bibcode:1977Sci...198.1035N. doi:10.1126/science.198.4321.1035. PMID 17779689.

- ^ Bortman, Henry (2004-08-26). "Was Venus Alive? 'The Signs are Probably There'". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ Sleep, N. H.; Zahnle, K.; Neuhoff, P. S. (2001). "Initiation of clement surface conditions on the earliest Earth". PNAS. 98 (7): 3666–3672. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.3666S. doi:10.1073/pnas.071045698. PMC 31109. PMID 11259665Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ Nimmo, F.; McKenzie, D. (1998). "Volcanism and Tectonics on Venus". Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 26: 23–51. Bibcode:1998AREPS..26...23N. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.26.1.23.

- ^ Marov, Mikhail Ya. (2004). "Mikhail Lomonosov and the discovery of the atmosphere of Venus during the 1761 transit". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 2004 (IAUC196). Cambridge University Press: 209–219. Bibcode:2005tvnv.conf..209M. doi:10.1017/S1743921305001390.

- ^ Britannica online encyclopedia: Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov

- ^ a b Weart, Spencer, The Discovery of Global Warming, "Venus & Mars", June 2008

- ^ Robert Roy Britt (2001-11-27). "First Detection Made of an Extrasolar Planet's Atmosphere". Space.com. Retrieved 2008-01-17. [dead link]

- ^ a b "Venus' Atmosphere to be Probed During Rare Solar Transit". Space.com. 2004-06-07. Retrieved 2008-01-17. [dead link]

- ^ a b "NCAR Scientist to View Venus's Atmosphere during Transit, Search for Water Vapor on Distant Planet". National Center for Atmospheric Research and UCAR Office of Programs. 2004-06-03. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ "Venus Exploration Mission PLANET-C". Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. 2006-05-17. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ "New Frontiers Program – Program Description". NASA. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Venus Mobile Explorer -Description". NASA. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ Myers, Robert (2002-11-13). "Robotic Balloon Probe Could Pierce Venus's Deadly Clouds" (PDF). SPACE.com. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ Landis, Geoffrey A. (2006). "Robotic Exploration of the Surface and Atmosphere of Venus". Acta Astronautica. 59 (7): 570–579. Bibcode:2006AcAau..59..570L. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2006.04.011.

- ^ Paul Marks (2005-05-08). "To conquer Venus, try a plane with a brain". NewScientist.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Russia Eyes Scientific Mission to Venus". Russian Federal Space Agency. 2010-10-26. Retrieved 2012-02-22.

- ^ "Scientific goals of the Venera-D mission". Russian Space Research Institute. Retrieved 2012-02-22.

External links

![]() Media related to Atmosphere of Venus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Atmosphere of Venus at Wikimedia Commons