Cape May, New Jersey

Cape May, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

Beach Avenue in Cape May seen from the sea | |

| Motto: The Nation's Oldest Seashore Resort | |

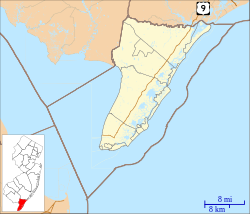

Location of Cape May in Cape May County highlighted in red (left). Inset map: Location of Cape May County in New Jersey highlighted in orange (right). | |

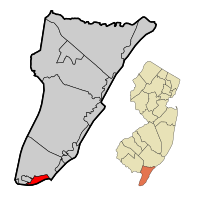

Census Bureau map of Cape May, New Jersey | |

Location in Cape May County Location in New Jersey | |

| Coordinates: 38°56′00″N 74°55′17″W / 38.93333°N 74.92139°W[1][2] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Cape May |

| Incorporated | March 8, 1848, as Cape Island Borough |

| Reincorporated | March 10, 1851, as Cape Island City |

| Reincorporated | March 9, 1869, as Cape May City |

| Named for | Cornelius Jacobsen Mey |

| Government | |

| • Type | Faulkner Act (council–manager) |

| • Body | City Council |

| • Mayor | Zachary Mullock (term ends December 31, 2024)[3][4] |

| • City manager | Paul E. Dietrich Sr.[5] |

| • Municipal clerk | Erin C. Burke[6] |

| Area | |

• Total | 2.90 sq mi (7.50 km2) |

| • Land | 2.47 sq mi (6.41 km2) |

| • Water | 0.42 sq mi (1.10 km2) 14.59% |

| • Rank | 341st of 565 in state 8th of 16 in county[1] |

| Elevation | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 2,768 |

• Estimate (2023)[11] | 2,757 |

| • Rank | 457th of 565 in state 9th of 16 in county[12] |

| • Density | 1,119.2/sq mi (432.1/km2) |

| • Rank | 370th of 565 in state 6th of 16 in county[12] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Code | |

| Area code | 609[15] |

| FIPS code | 3400910270[1][16][17] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0885178[1][18] |

| Website | www |

Cape May (sometimes Cape May City) is a city and seaside resort located at the southern tip of Cape May Peninsula in Cape May County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Located on the Atlantic Ocean near the mouth of the Delaware Bay, it is one of the country's oldest vacation resort destinations.[19] The city, and all of Cape May County, is part of the Ocean City metropolitan statistical area, and is part of the Philadelphia-Wilmington-Camden, PA-NJ-DE-MD combined statistical area, also known as the Delaware Valley or Philadelphia metropolitan area.[20] It is the southernmost municipality in New Jersey.

As of the 2020 United States census, the city's resident population was 2,768,[21][10] a decrease of 839 (−23.3%) from the 2010 census count of 3,607,[22][23] which in turn reflected a decline of 427 (−10.6%) from the 4,034 counted in the 2000 census.[24] In the summer, Cape May's population is expanded by as many as 40,000 to 50,000 visitors.[25][26] The entire city of Cape May is designated the Cape May Historic District, a National Historic Landmark due to its concentration of Victorian architecture.

In 2008, Cape May was recognized as one of the top 10 beaches in the United States by the Travel Channel.[27] It is part of the South Jersey region of the state.

History

[edit]17th and 18th centuries

[edit]The area was originally settled by the Kechemeche Native American tribe, who were part of the Lenape tribe.[28] The Kechemeche first encountered European colonialists around 1600.[citation needed] The city was named for the Dutch captain Cornelius Jacobsen Mey, who explored and charted the area between 1611–1614 and established a claim for the province of New Netherland.[29][30] It was later settled by New Englanders from the New Haven Colony.

Cape May began hosting vacationers from Philadelphia in the mid-18th century and is recognized as the country's oldest seaside resort.[31] [26]

19th century

[edit]Following the construction of Congress Hall in 1816, Cape May became increasingly popular in the 19th century and was considered one of the finest resorts in America by the 20th century.[32]

What is now Cape May was formed as the borough of Cape Island by the New Jersey Legislature on March 8, 1848, from portions of Lower Township. It was reincorporated as Cape Island City on March 10, 1851, and was renamed Cape May City on March 9, 1869.[33]

Tourism to the city was boosted in 1863 with the opening of the Tuckahoe and Cape May Railroad.

The city suffered devastating fires in 1869 and 1878. In the early hours of August 31, 1869, a fire broke out in the Japanese store on Washington Street. The fire destroyed the post office and at least thirty-five other buildings. Press reports at the time did not mention any deaths.[34] In 1878, a five-day-long fire destroyed 30 blocks of the town center. Replacement homes were almost uniformly of Victorian style,[35] and more recent protectionist efforts have left Cape May with many famously well-maintained Victorian houses—the second largest collection of such homes in the nation after San Francisco[citation needed].

20th century

[edit]Because of the World War II submarine threat off the East Coast of the United States, especially off the shore of Cape May and at the mouth of the Delaware Bay, numerous United States Navy facilities were located here in order to protect American coastal shipping. Cape May Naval facilities, listed below, provided significant help in reducing the number of ships and crew members lost at sea.[36]

- Naval Air Station, Cape May

- Naval Base, Cape May

- Inshore Patrol, Cape May

- Naval Annex, Inshore Patrol, Cape May

- Joint Operations Office, Naval Base, Cape May

- Welfare and Recreation Office, Cape May

- Dispensary, Naval Air Station, Cape May

- Naval Frontier Base, Cape May

- Degaussing Range (Cold Spring Inlet), Naval Base, Cape May

- Joint Operations Office, Commander Delaware Group, ESF, Cape May

- Anti-Submarine Attack Teacher Training Unit, U.S. Naval Base, Cape May

- Naval Annex, Admiral Hotel, Cape May

In 1976, Cape May was designated a National Historic Landmark as the Cape May Historic District, making Cape May the only city in the U.S. to be wholly designated as a national historic district.[37] That designation is intended to ensure the architectural preservation of these buildings.

Geography

[edit]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Cape May had a total area of 2.90 square miles (7.50 km2), including 2.47 square miles (6.41 km2) of land and 0.42 square miles (1.10 km2) of water (14.59%).[1][2] Cape May is generally low-lying; its highest point, at the intersection of Washington and Jackson Streets, is 14 ft (4.3 m) above sea level.[38]

Unincorporated communities, localities and place names located partially or completely within the city include Poverty Beach.[39]

Cape May borders the Cape May County municipalities of Lower Township and West Cape May Borough and the Atlantic Ocean.[40][41][42] The Cape May–Lewes Ferry provides transportation across the Delaware Bay between North Cape May, New Jersey, and Lewes, Delaware.

Cape May Harbor, which borders Lower Township and nearby Wildwood Crest allows fishing vessels to enter from the Atlantic Ocean, was created as of 1911, after years of dredging completed the harbor which covers 500 acres (200 ha).[43] Cape May Harbor Fest celebrates life in and around the harbor, with the 2011 event commemorating the 100th anniversary of the harbor's creation.[44]

Cape May is the southernmost point in New Jersey.[45] It is at approximately the same latitude as Washington, D.C., and Arlington County, Virginia, and equidistant to Manhattan and Virginia.[46]

Climate

[edit]According to the Köppen climate classification system, Cape May has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) with hot, humid summers, cool winters and year-round precipitation. Its climate resembles that of its neighbor, the Delmarva Peninsula. During the summer months in Cape May, a cooling afternoon sea breeze is present on most days, but episodes of extreme heat and humidity can occur with heat index values at or above 95.0 °F (35.0 °C). During the winter months, episodes of extreme cold and wind can occur with wind chill values 0.0 °F (−17.8 °C). The hardiness zone of Cape May is 8a with an average annual extreme minimum air temperature of 10.8 °F (−11.8 °C). The average seasonal snowfall total is around 15 in (380 mm), and the average snowiest month is February which corresponds with the annual peak in nor'easter activity.

| Climate data for Cape May 2 NW, New Jersey, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1894–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

75 (24) |

82 (28) |

91 (33) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

102 (39) |

99 (37) |

96 (36) |

96 (36) |

83 (28) |

76 (24) |

102 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 61.1 (16.2) |

62.7 (17.1) |

70.8 (21.6) |

80.8 (27.1) |

87.0 (30.6) |

92.3 (33.5) |

94.9 (34.9) |

93.0 (33.9) |

88.7 (31.5) |

81.8 (27.7) |

71.2 (21.8) |

63.6 (17.6) |

96.2 (35.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 43.3 (6.3) |

45.2 (7.3) |

51.7 (10.9) |

61.8 (16.6) |

71.1 (21.7) |

80.1 (26.7) |

85.5 (29.7) |

84.3 (29.1) |

78.6 (25.9) |

67.9 (19.9) |

56.9 (13.8) |

48.1 (8.9) |

64.5 (18.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 35.9 (2.2) |

37.3 (2.9) |

43.6 (6.4) |

52.9 (11.6) |

62.3 (16.8) |

71.6 (22.0) |

76.9 (24.9) |

75.7 (24.3) |

70.1 (21.2) |

59.3 (15.2) |

48.8 (9.3) |

40.6 (4.8) |

56.2 (13.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 28.5 (−1.9) |

29.4 (−1.4) |

35.4 (1.9) |

44.1 (6.7) |

53.5 (11.9) |

63.0 (17.2) |

68.3 (20.2) |

67.2 (19.6) |

61.7 (16.5) |

50.7 (10.4) |

40.6 (4.8) |

33.0 (0.6) |

47.9 (8.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 13.1 (−10.5) |

15.5 (−9.2) |

21.2 (−6.0) |

32.2 (0.1) |

40.7 (4.8) |

51.1 (10.6) |

59.3 (15.2) |

57.2 (14.0) |

48.0 (8.9) |

35.7 (2.1) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

19.4 (−7.0) |

10.8 (−11.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

−1 (−18) |

7 (−14) |

22 (−6) |

33 (1) |

42 (6) |

51 (11) |

45 (7) |

32 (0) |

26 (−3) |

14 (−10) |

5 (−15) |

−2 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.22 (82) |

2.97 (75) |

4.10 (104) |

3.34 (85) |

3.55 (90) |

3.53 (90) |

3.88 (99) |

4.01 (102) |

3.76 (96) |

4.17 (106) |

3.29 (84) |

4.02 (102) |

43.84 (1,114) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.5 (11) |

5.7 (14) |

2.5 (6.4) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

2.0 (5.1) |

14.8 (38) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.6 | 10.7 | 11.7 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 10.1 | 10.0 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.6 | 9.4 | 11.2 | 123.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.9 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 8.4 |

| Source: NOAA[47][48] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for North Cape May, NJ Ocean Water Temperature (4 NW Cape May) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 42 (6) |

40 (4) |

45 (7) |

52 (11) |

59 (15) |

68 (20) |

73 (23) |

76 (24) |

72 (22) |

61 (16) |

52 (11) |

42 (6) |

57 (14) |

| Source: NOAA[49] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

[edit]According to the A. W. Kuchler U.S. potential natural vegetation types, Cape May would have a dominant vegetation type of Northern Cordgrass (73) with a dominant vegetation form of Coastal Prairie (20).[50]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 1,248 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,699 | 36.1% | |

| 1890 | 2,136 | 25.7% | |

| 1900 | 2,257 | 5.7% | |

| 1910 | 2,471 | 9.5% | |

| 1920 | 2,999 | 21.4% | |

| 1930 | 2,637 | −12.1% | |

| 1940 | 2,583 | −2.0% | |

| 1950 | 3,607 | 39.6% | |

| 1960 | 4,477 | 24.1% | |

| 1970 | 4,392 | −1.9% | |

| 1980 | 4,853 | 10.5% | |

| 1990 | 4,668 | −3.8% | |

| 2000 | 4,034 | −13.6% | |

| 2010 | 3,607 | −10.6% | |

| 2020 | 2,768 | −23.3% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 2,757 | [11] | −0.4% |

| Population sources: 1870–2000[51] 1870–1920[52] 1870[53][54] 1880–1890[55] 1890–1910[56] 1910–1930[57] 1940–2000[58][59] 2010[22][23] 2020[21][10] | |||

2010 census

[edit]The 2010 United States census counted 3,607 people, 1,457 households, and 782 families in the city. The population density was 1,500.6 per square mile (579.4/km2). There were 4,155 housing units at an average density of 1,728.5 per square mile (667.4/km2). The racial makeup was 89.05% (3,212) White, 4.85% (175) Black or African American, 0.30% (11) Native American, 0.67% (24) Asian, 0.11% (4) Pacific Islander, 2.30% (83) from other races, and 2.72% (98) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.62% (311) of the population.[22]

Of the 1,457 households, 16.3% had children under the age of 18; 44.6% were married couples living together; 7.5% had a female householder with no husband present and 46.3% were non-families. Of all households, 42.0% were made up of individuals and 27.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.95 and the average family size was 2.64.[22]

12.8% of the population were under the age of 18, 20.6% from 18 to 24, 18.6% from 25 to 44, 20.3% from 45 to 64, and 27.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42.2 years. For every 100 females, the population had 104.7 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 107.4 males.[22]

The Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $35,660 (with a margin of error of +/− $4,248) and the median family income was $50,846 (+/− $16,315). Males had a median income of $43,015 (+/− $20,953) versus $31,630 (+/− $22,691) for females. The per capita income for the city was $30,046 (+/− $4,010). About 2.2% of families and 4.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.1% of those under age 18 and 7.1% of those age 65 or over.[60]

2000 census

[edit]As of the 2000 United States census,[16] there were 4,034 people, 1,821 households, and 1,034 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,623.7 inhabitants per square mile (626.9/km2). There were 4,064 housing units at an average density of 1,635.7 per square mile (631.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 91.32% White, 5.26% African American, 0.20% Native American, 0.40% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 1.26% from other races, and 1.51% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.79% of the population.[61][59]

There were 1,821 households, out of which 18.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.6% were married couples living together, 7.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 43.2% were non-families. 39.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 24.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.02 and the average family size was 2.69.[61][59]

In the city, the population was spread out, with 16.3% under the age of 18, 11.5% from 18 to 24, 19.8% from 25 to 44, 23.9% from 45 to 64, and 28.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 47 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.5 males.[61][59]

The median income for a household in the city was $33,462, and the median income for a family was $46,250. Males had a median income of $29,194 versus $25,842 for females. The per capita income for the city was $29,902. About 7.7% of families and 9.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.0% of those under age 18 and 10.9% of those age 65 or over.[61][59]

Economy

[edit]

Tourism is Cape May's largest industry. The economy runs on the Washington Street Mall and includes shops, restaurants, lodgings, and tourist attractions including the Cape May boardwalk. Many historic hotels and B&Bs are located in Cape May, and commercial and sport fishing is a significant component of its economy.

Cove Beach, located at Cape May southernmost tip, hosts hundreds of swimmers, sunbathers, surfers, and hikers daily during summer months.[62]

Cape May has been a popular resort for French Canadian tourists for several decades. Cape May County established a tourism office in Montreal, Quebec, but around 1995 it closed due to budget cuts. By 2010, the tourism office of Cape May County established a French language coupon booklet.[63]

Arts and culture

[edit]

Cape May has become known both for its Victorian gingerbread homes and its cultural offerings. The town hosts the Cape May Jazz Festival,[64] the Cape May Music Festival[65] and the Cape May, New Jersey Film Festival.[66] Cape May Stage, an Equity theater founded in 1988, performs at the Robert Shackleton Playhouse on the corner of Bank and Lafayette Streets.[67] East Lynne Theater Company, an Equity professional company specializing in American classics and world premieres, has its mainstage season from June–December and March, with school residencies throughout the year.[68] Cape May is home to the Mid-Atlantic Center for the Arts & Humanities (MAC), established in 1970 by volunteers who succeeded in saving the 1879 Emlen Physick Estate from demolition. MAC offers a wide variety of tours, activities and events throughout the year for residents and visitors and operates three Cape May area historic sites—the 1879 Emlen Physick Estate, the Cape May Lighthouse and the World War II Lookout Tower.[69] The Center for Community Arts (CCA) offers African American history tours of Cape May, arts programs for young people[70] and is transforming the historic Franklin Street School, constructed in 1928 to house African-American students in a segregated school, into a Community Cultural Center.[71]

Cape May is the home of Cape May diamonds, which show up at Sunset Beach and other beaches in the area. These are in fact clear quartz pebbles that wash down from the Delaware River. They begin as prismatic quartz (including the color sub-varieties such as smoky quartz and amethyst) in the quartz veins alongside the Delaware River that get eroded out of the host rock and wash down 200 miles to the shore. Collecting Cape May diamonds is a popular pastime and many tourist shops sell them polished or even as faceted stones.[72]

The Cape May area is also world-famous for the observation of migrating birds, especially in the fall. With over 400 bird species having been recorded in this area by hundreds of local birders, Cape May is arguably the top bird-watching area in the entire Northeastern United States. The Cape May Warbler, a small songbird, takes it name from this location. The Cape May Bird Observatory is based nearby at Cape May Point.[73]

Cape May is also a destination for marine mammal watching. Several species of whales and dolphins can be seen in the waters of the Delaware Bay and Atlantic Ocean, many within 10 mi (16 km) of land, due to the confluence of fresh and saltwater that make for a nutrient rich area for marine life. Whale and dolphin watching cruises are a year-round attraction in Cape May, part of an ecotourism / agritourism industry that generated $450 million in revenue in the county, the most of any in the state.[74]

The Harriet Tubman Museum in downtown Cape May features the life and work of Harriet Tubman, an abolitionist and social activist.[75]

Fisherman's Memorial

[edit]Cape May Fisherman's Memorial, located at Baltimore and Missouri Avenues, was built in 1988. It features a circular plaza reminiscent of a giant compass, a granite statue of a mother and two small children looking out to Harbor Cove, and a granite monument listing the names of 75 local fishermen who died at sea. The names begin with Andrew Jeffers, who died in 1893, and include the six people who died in March 2009 with the sinking of the scalloping boat Lady Mary.[76] The granite statue was designed by Heather Baird with Jerry Lynch. The memorial is maintained by the City of Cape May and administered by the Friends of the Cape May Fisherman's Memorial. Visitors often leave a stone or seashell on the statue's base in tribute to the fishermen.[77]

Government

[edit]

Local government

[edit]Effective July 1, 2004, Cape May switched to a Council-Manager form of government under the Faulkner Act,[78] after having used Plan A of the Faulkner Act Small Municipality form since 1995.[79][80] The city is one of 42 municipalities (of the 564) statewide that use this form of government.[81] The governing body is comprised of the Mayor and the four-member City Council, with all positions elected at-large to four-year terms of office on a non-partisan basis as part of the November general election in even-numbered years. The Mayor is elected directly by the voters. The Borough Council is elected to serve four-year terms on a staggered basis, with three seats coming up for election together and then the mayor and the fourth council seat up for vote together two years later. Following the 2004 elections, the first under the new form of government, lots were drawn to determine which of the newly elected members would serve a four-year term, with the other three serving two-year terms. A city manager is responsible for the city's executive functions, managing Cape May's activities and operation.[7][82][83] Voters approved a November 2010 referendum to shift the city's elections from May to November, with city officials estimating that the change would save $30,000 in costs that had been associated with each May election.[84]

In March 2015, Councilman Jerry Inderwies Jr. resigned to protest what he called a "witch hunt" against the police chief.[85] In the November 2015 general election, Roger Furlin was elected to fill the balance of the council seat vacated by Inderwies.[86]

In January 2021, the city council selected Lorraine Baldwin to fill the council seat expiring in 2022 that had been held by Zachary Mullock until he resigned to take office as mayor.[87] Baldwin served on an interim basis until the November 2021 general election, when voters chose her to serve the balance of the term of office.[88] Also in January 2021, Michael Voll was appointed to City Manager.

In November 2021, the city council appointed Michael Yeager to fill the seat expiring in December 2021 that had bene held by Christopher Bezaire until he resigned after pleading guilty earlier that month to charges that he had engaged in stalking an ex-girlfriend and that he had been in contempt of court.[89]

As of 2023[update], the Mayor of Cape May City is Zachary Mullock, whose term of office ends December 31, 2024. Other members of the Cape May City Council are Deputy Mayor Lorraine M. Baldwin (2026), Maureen K. McDade (2026), Shaine P. Meier (2026) and Michael Yeager (2024; elected to fill an unexpired term).[3][90][91][92][88][93]

Federal, state, and county representation

[edit]

Cape May City is located in the 2nd Congressional District[94] and is part of New Jersey's 1st state legislative district.[95][96][97]

For the 119th United States Congress, New Jersey's 2nd congressional district is represented by Jeff Van Drew (R, Dennis Township).[98] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2027) and Andy Kim (Moorestown, term ends 2031).[99][100]

For the 2024-2025 session, the 1st legislative district of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Mike Testa (R, Vineland) and in the General Assembly by Antwan McClellan (R, Ocean City) and Erik K. Simonsen (R, Lower Township).[101]

Cape May County is governed by a five-person Board of County Commissioners whose members are elected at-large on a partisan basis to three-year terms of office on a staggered basis, with either one or two seats coming up for election each year; At an annual reorganization held each January, the commissioners select one member to serve as director and another to serve as vice-director.[102] As of 2025[update], Cape May County's Commissioners are Director Leonard C. Desiderio (R, Sea Isle City, 2027),[103] Robert Barr (R, Ocean City; 2025),[104] Will Morey (R, Wildwood Crest; 2026),[105] Melanie Collette (R. Middle Township; 2026),[106] and Vice-Director Andrew Bulakowski (R, Lower Township; 2025).[107][102][108]

The county's constitutional officers are Clerk Rita Marie Rothberg (R, 2025, Ocean City),[109][110] Sheriff Robert Nolan (R, 2026, Lower Township)[111][112] and Surrogate E. Marie Hayes (R, 2028, Ocean City).[113][114][115][108]

Politics

[edit]As of March 2011, there were a total of 1,932 registered voters in Cape May City, of which 452 (23.4%) were registered as Democrats, 838 (43.4%) were registered as Republicans and 640 (33.1%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 2 voters registered as either Libertarians or Greens.[116]

In the 2012 presidential election, Republican Mitt Romney received 52.2% of the vote (745 cast), ahead of Democrat Barack Obama with 46.9% (669 votes), and other candidates with 0.9% (13 votes), among the 1,442 ballots cast by the city's 1,925 registered voters (15 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 74.9%.[117][118] In the 2008 presidential election, Republican John McCain received 50.9% of the vote (817 cast), ahead of Democrat Barack Obama, who received 46.4% (745 votes), with 1,605 ballots cast among the city's 1,940 registered voters, for a turnout of 82.7%.[119] In the 2004 presidential election, Republican George W. Bush received 53.8% of the vote (942 ballots cast), outpolling Democrat John Kerry, who received around 44.0% (771 votes), with 1,752 ballots cast among the city's 2,276 registered voters, for a turnout percentage of 77.0.[120]

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 72.9% of the vote (737 cast), ahead of Democrat Barbara Buono with 25.8% (261 votes), and other candidates with 1.3% (13 votes), among the 1,036 ballots cast by the city's 1,902 registered voters (25 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 54.5%.[121][122] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 52.1% of the vote (608 ballots cast), ahead of both Democrat Jon Corzine with 39.1% (457 votes) and Independent Chris Daggett with 6.8% (80 votes), with 1,168 ballots cast among the city's 2,069 registered voters, yielding a 56.5% turnout.[123]

Infrastructure

[edit]

Cape May established a desalinization plant in the late 1990s to manage salt going into its water aquifers.[124]

Cape May's current sewage plant in 1960 or 1961, less than a year after the New Jersey Attorney General's deadline for Cape May Point to have a sewage plant, as it had previously dumped sewage in the Delaware Bay; the New Jersey Department of Health had warned the borough about this in 1951. Despite the borough missing the deadline, the state never fined the borough as the Attorney General removed his judgment.[125]

Education

[edit]

For pre-kindergarten through sixth grade, public school students attend Cape May City Elementary School as part of the Cape May City School District.[126][127] As of the 2021–22 school year, the district, comprised of one school with an enrollment of 169 students and 22.6 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 7.5:1.[128] Also attending are students from Cape May Point, a non-operating district, as part of a sending/receiving relationship, with most students in the district coming from the United States Coast Guard Training Center Cape May.[129]

For seventh through twelfth grades, public school students attend the schools of the Lower Cape May Regional School District, which serves students from Cape May City, Cape May Point, Lower Township and West Cape May.[130] Schools in the district (with 2021–22 enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[131]) are Richard M. Teitelman Middle School[132] with 439 students in grades 7-8 and Lower Cape May Regional High School (LCMRHS)[133] with 764 students in grades 9–12.[134] In the 2011–12 school year, the city of Cape May paid $6 million in property taxes to cover the district's 120 high school students, an average of $50,000 per student attending the Lower Cape May district. Cape May officials have argued that the district's funding formula based on assessed property values unfairly penalizes Cape May, which has higher property values and a smaller number of high school students as a percentage of the population than the other constituent districts, especially Lower Township.[135] The high school district's board of education has nine members, who are elected directly by voters to serve three-year terms of office on a staggered basis, with three seats up for election each year[136][137] Seats on the board are allocated based on population, with Cape May City assigned one seat.[138]

Students are also eligible to attend Cape May County Technical High School in Cape May Court House, which serves students from the entire county in its comprehensive and vocational programs, which are offered without charge to students who are county residents.[139][140] Special needs students may be referred to Cape May County Special Services School District in the Cape May Court House area.

The nearest private Catholic school serving Cape May is Wildwood Catholic Academy (Pre-K12) in North Wildwood, under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Camden.

Colleges and universities in the Cape May area include Atlantic Cape Community College, Rutgers University–Camden, and the Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences.

The Cape May Branch of the Cape May County Public Library is located in Cape May City.[141] The library was previously in city hall but later moved to a standalone building. In 2009 an estimated $507,800 renovation was to take place with $395,300, or about 78% of the expenses, paid by Cape May County.[142] In 2024 it moved from a previous location to the renovated Franklin Street School.[143] A task force convened by Cape May City Council stated that the former library on Ocean Street should be used as a community center.[144]

History of education

[edit]According to an 1868 article in The Inkwell by William Lycett, historically Cape May had a school known as the "Indian Queen.", until another school opened in 1868. He also stated that his father operated a private educational institution.[145]

The first Cape May High School, built in 1901, was designed by Seymour Davis and built for $35,000.[146] In 1917 a new Cape May High School facility was built,[147] with the 1901 building becoming an elementary school.[146] In the past Cape May elementary schools were segregated on the basis of race; churches and households initially educated black children. From 1928 to 1948, black elementary school students attended Franklin Street School.[148] Cape May High School educated students of all races.[149] Cape May High closed effective December 22, 1960, and LCMRHS opened in 1961.[150]c. 1970 the first Cape May High School building was demolished, and was replaced with an Acme Markets location that occupied the site starting in the 1970s.[146] The second Cape May High School building has since become the city hall and police station.[147]

Cape May previously had its own Catholic K–8 school, Our Lady Star of the Sea School, which served as the parish school for Our Lady Star of the Sea, St. John of God (North Cape May) and St. Raymond (Villas) churches.[151] The St. Raymond School closed in 2007 with students sent to Our Lady Star of the Sea.[152] In 2010 Our Lady Star of the Sea merged into Cape Trinity Regional School (Pre-K–8) in North Wildwood.[153] That school in turn merged into Wildwood Catholic Academy in 2020.[154]

Starting in 2010, discussions were under way regarding a possible consolidation of the districts of Cape May City, Cape May Point and the West Cape May School District.[155]

The Franklin Street School opened as the current library due to a renovation worth $11,000,000. About one and one half years was the duration of the project completion. The opening ceremony involved a chain of people moving books between the old and new libraries with their hands.[156]

Transportation

[edit]

Roads and highways

[edit]As of May 2010[update], the city had a total of 31.63 mi (50.90 km) of roadways, of which 24.99 mi (40.22 km) were maintained by the municipality and 6.64 mi (10.69 km) by Cape May County.[157]

Route 109 leads into Cape May from the north and provides access to the southern terminus of the Garden State Parkway along with U.S. Route 9 in neighboring Lower Township.[158] U.S. Route 9 leads to the Cape May–Lewes Ferry, which heads across the Delaware Bay to Lewes, Delaware.[159]

Public transportation

[edit]

NJ Transit provides service to Philadelphia on the 313 and 315 routes and to Atlantic City on the 552 route, with seasonal service to Philadelphia on the 316 route and to the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Midtown Manhattan on the 319 route.[160][161]

The Great American Trolley Company operates trolley service in Cape May daily during the summer months, running along a loop route through the city.[162]

The city is served by rail from the Cape May City Rail Terminal, offering excursion train service on the Cape May Seashore Lines from the terminal located at the intersection of Lafayette Street and Elmira Street.[163][164]

The city last had regional passenger train service by the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines in the mid-1960s. Final service into Camden, New Jersey (across the Delaware River from Philadelphia) ended in January 1966, while service to Lindenwold station ended in October 1981.[165]

Ferry transport

[edit]The Delaware River and Bay Authority operates the Cape May-Lewes Ferry year-round, a 70-85 minute across Delaware Bay to Lewes, Delaware, carrying passengers and cars.[166] The ferry constitutes a portion of U.S. Route 9.

The Delaware River and Bay Authority operates a shuttle bus in the summer months which connects the Cape May Welcome Center with the Cape May–Lewes Ferry terminal.[167]

Media

[edit]

Cape May is served by several media outlets including WCFA-LP 101.5 FM, a commercial-free jazz and community station, the weekly Cape May Star and Wave, two free weekly newspapers, The Cape May Gazette and Exit Zero, and local websites CapeMay.com and Cape May Times.

The countywide newspaper is Cape May County Herald.

The regional newspapers for the area including Cape May County are the Press of Atlantic City, and the Philadelphia Inquirer.[168]

The name Exit Zero refers to the town's location at the far southern end of the Garden State Parkway near the intersection with Route 109. Informally, the entire town is sometimes called Exit Zero.[169]

Coast Guard Training Center Cape May

[edit]

The United States Coast Guard Training Center Cape May, New Jersey is the nation's only Coast Guard Recruit Training Center. In 1924, the U.S. Coast Guard occupied the base and established air facilities for planes used in support of United States Customs Service efforts. During the Prohibition era, several cutters were assigned to Cape May to foil rumrunners operating off the New Jersey coast. After Prohibition, the Coast Guard all but abandoned Cape May leaving a small air/sea rescue contingent. For a short period of time (1929–1934), part of the base was used as a civilian airport. With the advent of World War II, a larger airstrip was constructed and the United States Navy returned to train aircraft carrier pilots. The over the water approach simulated carrier landings at sea. The Coast Guard also increased its Cape May forces for coastal patrol, anti-submarine warfare, air/sea rescue and buoy service. In 1946, the Navy relinquished the base to the Coast Guard.[170] The Cape May Airport still houses the Naval Air Station Wildwood Aviation Museum.

In 1948, all entry-level training on the U.S. East Coast was moved to the U.S. Coast Guard Recruit Receiving Station in Cape May. The U.S. Coast Guard consolidated all recruit training functions in Cape May in 1982. Over 350 military and civilian personnel and their dependents are attached to the Cape May Training Center.[171]

In popular culture

[edit]- Cape May is the subject of the song "On the Way to Cape May", originally sung by Cozy Morley.[172]

- The 1980s horror film The Prowler was filmed entirely on location in Cape May.[173]

- The town lends its name to the Cape May Cafe, a restaurant in the Beach Club Resort at Walt Disney World.[174]

- In The Blacklist, Cape May is the setting in the episode "Cape May".[175]

- Scenes for the film A Complete Unknown, a biopic about Bob Dylan featuring Timothée Chalamet, were filmed in Cape May in the spring of 2024. Cape May served as a suitable location to mimic Newport, Rhode Island and the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, where Dylan first performed in public with an electric guitar. Minimal redress was needed, given the resort's commitment to its designation as a National Historic Landmark, with its concentration of Victorian architecture as well as other 19th and 20th century architectural motifs.[176]

Notable people

[edit]People who were born in, residents of, or otherwise closely associated with Cape May include:

- Douglas Adams (1876–1931), cricketer, who played for the Gentlemen of Philadelphia in First class cricket[177]

- Cliff Anderson (1929–1979), football player who played two seasons in the NFL with the Chicago Cardinals and New York Giants[178]

- Nan Brooks (1935–2018), children's book illustrator[179]

- Thomas Cannuli, professional poker player, known for finishing 6th place in the 2015 WSOP Main Event and winning a WSOP bracelet in the $3,333 WSOP.com Online No-Limit Hold'em High Roller[180]

- Frederick B. Dent (1922–2019), politician who served as the United States Secretary of Commerce from 1973 to 1975[181]

- Eugene Grace (1876–1960), president of Bethlehem Steel Corporation from 1916 to 1945[182]

- Bubba Green (born 1957), football player who played defensive lineman for one season for the Baltimore Colts[183]

- T. Millet Hand (1902–1956), politician who represented New Jersey's 2nd congressional district in the United States House of Representatives and served as mayor of Cape May[184]

- Thomas H. Hughes (1769–1839), the founder and owner of the Congress Hall Hotel, and a Democratic-Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from New Jersey[185]

- Chris Jay (born 1978), musician, actor and screenwriter. Founding member of the band, Army of Freshmen[186]

- Alan Kotok (1941–2006), computer scientist known for his work at Digital Equipment Corporation and at the World Wide Web Consortium[187]

- John Henry Kurtz (1945–2008), singer-songwriter and actor best known for performing the song "Drift Away"[188]

- John D. Lankenau (1817–1901), German-American businessman and philanthropist[189]

- Jarena Lee (1783–1864), the first woman authorized to preach by Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, in 1819[190]

- Anthony Maher (born 1979), professional soccer forward[191]

- Myles Martel (born 1943), communication adviser[192]

- Sylvius Moore (1912–2004), football player and coach who was head coach of the Hampton Pirates football team[193]

- Richie Phillips (1940–2013), sports union leader[194]

- Bill Pilczuk (born 1971), competitive swimmer[195]

- Louis Purnell (1920–2001), curator at the National Air and Space Museum and earlier in life, a decorated Tuskegee Airman[196]

- Emil Salvini (born 1949), author, historian and host / creator of PBS's Tales of the Jersey Shore[197]

- Charles W. Sandman Jr. (1921–1985), politician who represented New Jersey's 2nd congressional district and was the party's candidate for Governor of New Jersey in 1973[198]

- I. Grant Scott (1897–1964), politician who served in the New Jersey General Assembly, the New Jersey Senate and as Mayor of Cape May[199]

- Barbara Lee Smith (born 1938), mixed media artist, writer, educator and curator[200]

- Witmer Stone (1866–1939), ornithologist who did much of his research in Cape May[201]

- Julius H. Taylor (1914–2011), professor emeritus at Morgan State University who was chairperson of the department of physics.[202]

- Harriet Tubman (1822–1913), abolitionist and social activist who, after escaping slavery, made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people; she is honored with a museum in the city[75]

- Paul Volcker (1927–2019), former chairman of the United States Federal Reserve who was born here while his father was the Cape May city manager[203]

- John B. Walthour (1904–1952), 4th bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Atlanta[204]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e 2019 Census Gazetteer Files: New Jersey Places Archived March 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990 Archived August 24, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Mayor & Council, City of Cape May. Accessed July 9, 2023.

- ^ 2023 New Jersey Mayors Directory, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, updated February 8, 2023. Accessed February 10, 2023.

- ^ City Manager, City of Cape May. Accessed March 19, 2024.

- ^ City Clerk, City of Cape May. Accessed March 19, 2024.

- ^ a b 2012 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, March 2013, p. 8.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ "City of Cape May". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c Total Population: Census 2010 - Census 2020 New Jersey Municipalities, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Minor Civil Divisions in New Jersey: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023, United States Census Bureau, released May 2024. Accessed May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Population Density by County and Municipality: New Jersey, 2020 and 2021, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Look Up a ZIP Code for Cape May, NJ Archived May 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, United States Postal Service. Accessed November 6, 2011.

- ^ ZIP Codes Archived October 6, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, State of New Jersey. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ Area Code Lookup – NPA NXX for Cape May, NJ Archived May 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Area-Codes.com. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ a b U.S. Census website Archived December 27, 1996, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Geographic Codes Lookup for New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- ^ US Board on Geographic Names Archived February 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, United States Geological Survey. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Charles P. "Many Drive To Resorts On Atlantic: Coast Places Draw Drivers From Pittsburgh District" Archived November 19, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, The Pittsburgh Press, June 22, 1930, p. 3 of the Automobile section. Accessed July 4, 2011. "The southern part of New Jersey largely in Cape May County contains other popular resorts. Cape May City, the southernmost part of New Jersey, is said to be the oldest vacation resort in the United States."

- ^ New Jersey: 2020 Core Based Statistical Areas and Counties, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 22, 2022.

- ^ a b Cape May city, New Jersey census profile, United States Census Bureau. Accessed October 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e DP-1 - Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for Cape May city, Cape May County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed April 20, 2012.

- ^ a b Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010 for Cape May city Archived 2012-04-30 at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed April 20, 2012.

- ^ Table 7. Population for the Counties and Municipalities in New Jersey: 1990, 2000 and 2010, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, February 2011. Accessed May 1, 2023.

- ^ Mulvihill, Geoff via Associated Press. "Dangerous fishing, quaint B&B's share N.J. resort" Archived October 27, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Delaware County Daily Times, March 30, 2009. Accessed October 27, 2019. "'I don't really think much about the fishing business,' said Jimmy Iapallucci, a cook at Uncle Bill's Pancake House near the beach. He suspects the tourists who swell the community's population from 4,000 to 40,000 each summer don't either."

- ^ a b Staff. "Life Style; Old Resort Draws New Clientele: Honeymooners" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, July 23, 1989. Accessed July 4, 2011. "At one time, Cape May was known as the serene Victorian getaway of four Presidents and scores of wealthy New York and Philadelphia industrialists. But recently, Cape May, the nation's oldest seaside resort, has begun to attract a new breed of beachgoer.... Innkeepers here say Cape May's 19th-century ambiance and views of the Atlantic Ocean are the main reasons this sleepy city of 5,000 (50,000 in the summer) has become popular for weddings and honeymoons."

- ^ Urgo, Jacqueline L. "Triumph for South Jersey" Archived April 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 23, 2008. Accessed October 29, 2015. "Neighboring Wildwood Crest came in second, followed by Ocean City, North Wildwood, Cape May, Asbury Park in Monmouth County, Avalon, Point Pleasant Beach in northern Ocean County, Beach Haven in southern Ocean County and Stone Harbor."

- ^ "Cape May Diamond Hunting Goes Back to the Kechemeche Tribe" Archived December 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Cape May County Herald, August 18, 2017. Accessed January 3, 2020. "The Kechemeche were part of the Lenni Lenape Council and were the original inhabitants of the southern part of Cape May County. The Lenape were the first settlers in the county and found the quartz stones washed up on the beaches in what is now Cape May Point."

- ^ Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names Archived November 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed August 28, 2015.

- ^ Gannett, Henry. The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States, p. 68. United States Government Printing Office, 1905. Accessed August 28, 2015.

- ^ [1] Archived November 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Cape May Historic Preservation Commission. "Design Standards", Published Fall 2002, Standard Publishing, Inc; page 8.

- ^ DiGiacomo, Robert. "Beach bicentennial: Cape May’s Congress Hall resort hits 200" Archived March 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, USA Today, June 25, 2016. Accessed March 21, 2018. "Like many ladies of a certain age, Congress Hall has enjoyed her fair share of drama and notoriety over the decades. The original hotel, built of wood, helped usher in Cape May’s role as the leading resort of the early 19th century."

- ^ Snyder, John P. The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606–1968 Archived August 13, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 113. Accessed April 20, 2012.

- ^ "Great Destruction of Property at Cape May". New York Times. September 1, 1869. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ Victorian Cape May Archived June 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Cape May Times. Accessed July 4, 2011. "Cape May looked a lot different before the fire of 1878. The town is the oldest seashore resort in the nation. In the 1800s, Cape May had quite a collection of classically designed seaside hotels. The fire of 1878 wiped out 30 blocks of the early seashore town, including some of the resort's major hotels, including the original Congress Hall.... And, for the most part, the new buildings that went up were built in the modern style of the day...later known as the Victorian style... lots of gingerbread trim, gables and turrets."

- ^ "U.S. Naval Activities, World War II". Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- ^ Kent, Bill. "Development; If They Build It, Will Even More Come? Cape May Ponders Parking Garage" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, November 9, 1997. Accessed July 4, 2011. "William Bolger, manager of the National Park Service Historic Landmarks Program for the Northeast, confirmed that he had been surveying Cape May to evaluate the city's historic buildings since January. 'Cape May is unique in America in that, since 1977, the entire city has been designated a National Historic Landmark District,' Mr. Bolger said. 'That means everything within the city limits is considered of historic landmark status.'"

- ^ Floodplain Management Plan Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, City of Cape May, September 10, 2009. Accessed April 20, 2012.

- ^ Locality Search Archived July 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, State of New Jersey. Accessed May 21, 2015.

- ^ Areas touching Cape May Archived August 31, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, MapIt. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- ^ Cape May County Archived February 26, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Coalition for a Healthy NJ. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- ^ New Jersey Municipal Boundaries Archived December 4, 2003, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Transportation. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- ^ Preston, Benjamin. "Cape May, New Jersey's Battle Against Nature" Archived July 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, The Earth Institute, June 20, 2011. Accessed July 4, 2011. "Beach erosion is a perennial challenge for coastal communities, but in Cape May, man began accelerating the natural process in 1903. That year, dredges began scooping sand and muck out of the small harbor, expanding it to its current 500 acres. By 1911, a pair of massive stone jetties were completed to protect the mouth of Cape May Inlet."

- ^ Staff. "Cape May Harbor Fest offers activities on land and sea" Archived 2011-10-01 at the Wayback Machine, Shore News Today, June 9, 2011. Accessed July 4, 2011. "Cape May's Harbor Fest, a celebration of seafood and song, the sea, its culture, economy and ecology, will take place 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Saturday, June 18 in and along the banks of Cape May Harbor on Delaware Avenue, with many of the land-based activities taking place at the Nature Center of Cape May.This year's festival commemorates the 100th anniversary of Cape May Harbor."

- ^ Salamone, Gina. "Cape May is a world away from the raffish reputation of the Jersey Shore; The seaside resort is full of quaint shops, Victorian homes, great beaches and top-rated restaurants" Archived November 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, New York Daily News, July 27, 2014. Accessed November 10, 2015. "Located on the southernmost point of New Jersey in the Cape May Peninsula, the city is also a big draw for nature lovers and birdwatchers due to its wetlands and wildlife refuges."

- ^ Weaver, Meg. "Counterintuitive Geographic Facts and Other Minutiae" Archived November 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, National Geographic Intelligent Travel, June 28, 2011. Accessed November 10, 2015. "Being the fact hound that I am, I had to check it out. Turns out, he's almost right. According to the U.S. Gazetteer, the latitude of Cape May, New Jersey, the Garden State's southernmost tip, is actually 38.96 degrees north while our fair National Geographic Headquarters in Washington, D.C., is 38.90 degrees north."

- ^ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Water Temperature Table of All Coastal Regions Archived September 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- ^ U.S. Potential Natural Vegetation, Original Kuchler Types, v2.0 (Spatially Adjusted to Correct Geometric Distortions) Archived July 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Data Basin. Accessed March 18, 2020.

- ^ Barnett, Bob. Population Data for Cape May County Municipalities, 1800 - 2000 Archived December 15, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, WestJersey.org, January 6, 2011. Accessed July 10, 2012.

- ^ Compendium of censuses 1726-1905: together with the tabulated returns of 1905 Archived February 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State, 1906. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ Raum, John O. The History of New Jersey: From Its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time, Volume 1, p. 260, J. E. Potter and company, 1877. Accessed October 8, 2013. "Cape May city contained in 1870 a population of 1,248."

- ^ Staff. A compendium of the ninth census, 1870, p. 259. United States Census Bureau, 1872. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ Porter, Robert Percival. Preliminary Results as Contained in the Eleventh Census Bulletins: Volume III - 51 to 75 Archived January 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, p. 97. United States Census Bureau, 1890. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910: Population by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions, 1910, 1900, 1890, United States Census Bureau, p. 336. Accessed July 10, 2012.

- ^ Fifteenth Census of the United States : 1930 - Population Volume I, United States Census Bureau, p. 715. Accessed December 3, 2011.

- ^ Table 6: New Jersey Resident Population by Municipality: 1940 - 2000, Workforce New Jersey Public Information Network, August 2001. Accessed May 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e DP-1: Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000 - Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data for Cape May city, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 10, 2012.

- ^ DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics from the 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates for Cape May city, Cape May County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed April 20, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Census 2000 Profiles of Demographic / Social / Economic / Housing Characteristics for Cape May city, New Jersey Archived 2014-08-24 at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed April 20, 2012.

- ^ "The Cove Beach in Cape May |". Jersey Shore Rentals. December 1, 2016. Archived from the original on January 8, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ ""Cape May, N.J., targets Canadian tourists" Archived October 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, USA Today. February 9, 2010. Accessed August 10, 2013.

- ^ Jackson, Vincent. "Jazz festival returns to Cape May next month, but without the original event's founders" Archived November 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Press of Atlantic City, October 28, 2012. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ Reich, Ronni. "Cape May Music Festival puts together an eclectic schedule" Archived December 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Star-Ledger, May 24, 2013. Accessed October 8, 2013. 'Classical ensembles from across the region, from the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra Chamber Players to the Bay-Atlantic Symphony, will take the stage for the 24th Cape May Festival. World music, jazz and country are also among the beachside musical offerings, which begin Sunday and continue through June 13."

- ^ About Archived 2013-11-27 at the Wayback Machine, Cape May Film Festival . Accessed October 8, 2013. "The Cape May NJ State Film Festival is New Jersey's premiere weekend film festival dedicated exclusively to the support and presentation of creative, challenging, groundbreaking, film/video works by New Jersey filmmakers.... It has grown from a three-day event attracting an audience of 500 in 2001 to a four-day film festival drawing thousands annually."

- ^ History and Mission Archived 2013-10-08 at archive.today, Cape May Stage. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ About Archived August 30, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, East Lynne Theater Company. Accessed October 8, 2013. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ About MAC Archived October 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Mid-Atlantic Center for the Arts & Humanities. Accessed October 8, 2013. "The Mid-Atlantic Center for the Arts & Humanities (MAC) is a multi-faceted non-profit organization that promotes the restoration, interpretation and cultural enrichment of greater Cape May for its residents and visitors."

- ^ About Archived February 8, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Center for Community Arts. Accessed August 29, 2015.

- ^ Cherry-Farmer. Stephanie. "People Preserving Places: Cape May's Franklin Street School" Archived November 9, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Preserve NJ, December 12, 2011. Accessed October 8, 2013. "Designed in the Colonial Revival Style by the architectural firm of Edwards and Green of Philadelphia and Camden, the Franklin Street School opened in September 1928 as an elementary school for Cape May's African-American children.... Currently, the Center is working with the city to rehabilitate the school for use as a community cultural center and the focal point for African-American heritage tours of the area."

- ^ Fox, Karen. "Cape May Diamonds" Archived August 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Cape May magazine, August 2009. Accessed July 4, 2011.

- ^ Cape May Bird Observatory Archived October 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Audubon Society. Accessed October 27, 2019.

- ^ Cutter, Joe. "Cape May will study impact of ecotourism and agritourismRead More: Cape May will study impact of ecotourism and agritourism" Archived November 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, WKXW, November 9, 2016. Accessed November 22, 2016. "Cape May County tourism director Diane Wieland says they want to find out about the interest in bird- and nature-watching, hiking, biking and whale- and dolphin-watching. Wieland says 10 years ago, ecotourism was generating more than $450 million annually for the county—about 11 percent of the county's tourism dollars. The county generates more tourism dollars than any other county in the state."

- ^ a b About, Harriet Tubman Museum. Accessed June 20, 2023. "Harriet Tubman lived in Cape May in the early 1850s, working to help fund her missions to guide enslaved people to freedom."

- ^ Degener, Richard. "Group has new goal for Cape Fishermen's Memorial" Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Press of Atlantic City, June 3, 2009. Accessed July 4, 2011.

- ^ Cape May County Fishermans Memorial Archived March 15, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Historical Marker Database. Accessed October 27, 2019.

- ^ Degener, Richard. "Cape May Government-Change Vote Challenged" Archived September 3, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, The Press of Atlantic City, July 8, 2003. Accessed April 20, 2012. "A recount upheld the two-vote margin to change the form of government, and now some residents are asking a judge to set aside the decision and order a new election in November. Residents voted 422-420 on May 13 to return the city to the council-manager form of government."

- ^ "The Faulkner Act: New Jersey's Optional Municipal Charter Law" Archived October 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey State League of Municipalities, July 2007. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ Degener, Richard. "Cape May Voters Might Choose Government-Change Panel" Archived September 3, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, The Press of Atlantic City, September 8, 2001. Accessed April 20, 2012. "The city in 1995 changed from a council-manager form of government to the small municipality plan A form of government under the Faulkner Act."

- ^ Inventory of Municipal Forms of Government in New Jersey, Rutgers University Center for Government Studies, July 1, 2011. Accessed June 1, 2023.

- ^ "Forms of Municipal Government in New Jersey", p. 12. Rutgers University Center for Government Studies. Accessed June 1, 2023.

- ^ Form of Government - Council / Manager Archived August 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, City of Cape May. Accessed October 8, 2013.

- ^ Fichter, Jack. "Moving Cape May Election to November to Save $30K" Archived November 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Cape May County Herald, November 3, 2010. Accessed August 30, 2014. "Voters here approved moving the municipal election from May to November in a 610-320 votes, Tues. Nov. 2."

- ^ Conti, Vince. "Update: Council Member Resigns Following Rescinding of Police Chief's Contract" Archived November 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Cape May County Herald, March 3, 2015. Accessed June 27, 2016. "Councilman Jerry Inderwies, a retired Cape May Fire Chief and one of the three new members of the council elected this past November, spoke out vehemently in Sheehan's defense.... Inderwies then resigned his council seat and stormed from the room to the applause of the assembled police."

- ^ Conti, Vince. "Furlin Takes Seat on Cape May Council, Mall Improvement District Budget Seen" Archived November 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Cape May County Herald, November 17, 2015. Accessed June 27, 2016. "Newly-elected Council member Roger Furlin was in his seat as Cape May City Council held its first meeting following the Nov. 3 election. Furlin won the seat vacated when Jerry Inderwies Jr. resigned in protest in March."

- ^ Dreyfuss, Bob; and Dreyfuss, Barbara. "Meet Lorraine Baldwin; Council’s newest member has deep roots in Cape May", The Cape May Sentinel, January 5, 2021. Accessed May 6, 2022. "Baldwin, who took her seat on council January 1, was unanimously chosen by the other four members of council to fill the seat vacated by Mayor Zack Mullock, which expires in 2022. If she chooses to continue in that spot, she’ll have to run in a special election in November 2021 and then again, if she seeks reelection, she’ll run for a full, four-year term in November 2022."

- ^ a b 2021 General Election Successful Candidates, Cape May County, New Jersey, updated November 16, 2021. Accessed January 1, 2022.

- ^ Barlow, Bill. "Mike Yeager appointed to Cape May City Council, replaces Chris Bezaire", The Press of Atlantic City, November 18, 2021. Accessed May 6, 2022. "In a unanimous vote this week, Cape May City Council appointed Mike Yeager to fill in the unexpired term vacated this month by Chris Bezaire, who stepped down after pleading guilty in Superior Court to stalking a former girlfriend and contempt of court."

- ^ 2023 Municipal Data Sheet, City of Cape May. Accessed July 9, 2023.

- ^ 2023 County & Municipal Elected Officials Cape May County, NJ -- July 2023, Cape May County, New Jersey, August 3, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2023.

- ^ Summary Results Report 2022 November Cape May General Election November 8, 2022 Official Results, Cape May County, New Jersey, updated November 17, 2022. Accessed January 1, 2023.

- ^ 2020 General Election Successful Candidates, Cape May County, New Jersey, updated December 4, 2020. Accessed January 1, 2021.

- ^ Plan Components Report Archived February 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Redistricting Commission, December 23, 2011. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- ^ Municipalities Sorted by 2011-2020 Legislative District Archived August 2, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- ^ 2019 New Jersey Citizen's Guide to Government Archived November 5, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey League of Women Voters. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- ^ Districts by Number for 2011-2020 Archived July 14, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 6, 2013.

- ^ Directory of Representatives: New Jersey, United States House of Representatives. Accessed January 3, 2019.

- ^ U.S. Sen. Cory Booker cruises past Republican challenger Rik Mehta in New Jersey, PhillyVoice. Accessed April 30, 2021. "He now owns a home and lives in Newark's Central Ward community."

- ^ https://www.cbsnews.com/newyork/news/andy-kim-new-jersey-senate/

- ^ Legislative Roster for District 1, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 12, 2024.

- ^ a b Board of County Commissioners, Cape May County, New Jersey. Accessed April 28, 2022. "Cape May County Government is governed by a Board of County Commissioners. These individuals are elected at large by the citizens of Cape May County and hold spaced 3-year terms." Note that as of date accessed, Desiderio is listed with an incorrect term-end year of 2020.

- ^ Leonard C. Desiderio, Cape May County, New Jersey. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- ^ E. Marie Hayes, Cape May County, New Jersey. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- ^ Will Morey, Cape May County, New Jersey. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- ^ Jeffrey L. Pierson, Cape May County, New Jersey. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- ^ Andrew Bulakowski, Cape May County New Jersey. Accessed January 30, 2023.

- ^ a b 2021 County & Municipal Elected Officials Cape May County, NJ -- July 2021, Cape May County, New Jersey, September 13, 2021. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- ^ County Clerk, Cape May County, New Jersey. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- ^ Members List: Clerks, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- ^ Sheriff's Page Page, Cape May County, New Jersey. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- ^ Members List: Sheriffs, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- ^ Surrogate, Cape May County, New Jersey. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- ^ Members List: Surrogates, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- ^ Constitutional Officers, Cape May County, New Jersey. Accessed April 28, 2022.

- ^ Voter Registration Summary - Cape May Archived May 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, March 23, 2011. Accessed October 16, 2012.

- ^ "Presidential General Election Results - November 6, 2012 - Cape May County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. March 15, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast - November 6, 2012 - General Election Results - Cape May County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. March 15, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ 2008 Presidential General Election Results: Cape May County Archived May 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 23, 2008. Accessed October 16, 2012.

- ^ 2004 Presidential Election: Cape May County Archived May 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 13, 2004. Accessed October 16, 2012.

- ^ "Governor - Cape May County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. January 29, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast - November 5, 2013 - General Election Results - Cape May County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. January 29, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ 2009 Governor: Cape May County Archived 2012-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 31, 2009. Accessed October 16, 2012.

- ^ Jordan, Joe (2003). Cape May Point, The Illustrated History-1875 to the Present. Schiffer Pub. p. 116. ISBN 9780764318306.

- ^ Jordan, Joe (2003). Cape May Point, The Illustrated History-1875 to the Present. Schiffer Pub. p. 117. ISBN 9780764318306.

- ^ Cape May City Board of Education District Bylaw 0110 - Identification, Cape May City School District. Accessed February 11, 2023. "Purpose: The Board of Education exists for the purpose of providing a thorough and efficient system of free public education in grades Pre-Kindergarten through six in the Cape May City School District. Composition: The Cape May City School District comprises all the area within the municipal boundaries of Cape May City."

- ^ School Performance Reports for the Cape May City School District, New Jersey Department of Education. Accessed March 31, 2024.

- ^ District information for Cape May City School District, National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ Cape May City School District 2013 Report Card Narrative Archived December 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Education. Accessed December 29, 2016. "The District is a one-school district. 60% of the students come from the United States Coast Guard Training Center based in Cape May; 25% from Cape May City residents; and 15% from the Low-income Housing Authority, and three students from the sending district of Cape May Point."

- ^ School Choice Brochure Archived March 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Lower Cape May Regional School District. Accessed March 21, 2018. "Lower Cape May Regional High School is a four-year comprehensive public High School that serves students from Cape May, West Cape May, Lower Township, Cape May Point and now Choice School students."

- ^ School Data for the Lower Cape May Regional High School District, National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ General Information, Richard M. Teitelman Middle School. Accessed February 11, 2023.

- ^ General Information, Lower Cape May Regional High School. Accessed February 11, 2023.

- ^ New Jersey School Directory for the Lower Cape May Regional School District, New Jersey Department of Education. Accessed February 1, 2024.

- ^ Fichter, Jack. "Cape May Paying $50K Per Student to Regional School District" Archived May 17, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Cape May County Herald, January 4, 2012. Accessed March 21, 2018. "Cape May — Taxpayers here pay $50,000 per year for each student sent to the Lower Cape May Regional High School District, a total of $6 million per year.... Deputy Mayor Jack Wichterman said Cape May was paying $6 million to send 120 kids to the regional school district.... 'We have no say in the formula that's utilized to determine how much money we pay to that school district,' he said. 'There are several formulas that can be used and the one that the Lower Township members of that school board chose to use is the one that penalizes the City of Cape May because our real estate values are so much higher than they are in Lower Township.'"

- ^ Annual Comprehensive Financial Report of the Lower Cape May Regional School District Archived May 17, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Education, for year ending June 30, 2018. Accessed February 3, 2020. "The Lower Cape May Regional School District (District) is a Type II school district located in Cape May County, New Jersey and covers an area of approximately 34 square miles. As a Type II school district, it functions independently through a Board of Education. The Board is comprisedof nine members elected to three-year terms. These terms are staggered so that three member’s terms expire each year. The purpose of the School District is to provide educational services for all of Lower Cape May Regional’s students in grades 7 through 12."

- ^ Board of Education Archived December 24, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Lower Cape May Regional School District. Accessed February 11, 2020.

- ^ Crowley, Terence J. A Response to the Cape May Study to Reconfigure the Lower Cape May Regional School District Archived May 17, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Lower Cape May Regional School District, January 6, 2014. Accessed February 11, 2020. "The Lower Cape May Regional District (Regional) is classified as a Limited Purpose District.... It is a Type II district and apportions the Board of Education seats based upon the most recent United States Census. It has nine seats on the Board and that are apportioned as follows: Cape May City 1; West Cape May 1; Lower Township 7."

- ^ Frequently Asked Questions Archived October 27, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Cape May County Technical High School. Accessed October 27, 2019. "All residents of Cape May County are eligible to attend Cape May County Technical High School.... The Cape May County Technical High School is a public school so there is no cost to residents of Cape May County."

- ^ Technical High School Admissions Archived October 27, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Cape May County Technical High School. Accessed October 27, 2019. "All students who are residents of Cape May County may apply to the Technical High School."

- ^ Cape May City Library Location Archived October 27, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Cape May County Library. Accessed October 27, 2019.

- ^ Degener, Richard (June 20, 2009). "Renovation next chapter for Cape May library". The Press of Atlantic City. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ Barlow, Bill (June 13, 2024). "GALLERY: Cape May launches new library". Press of Atlantic City. Atlantic City, New Jersey. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Conti, Vince (September 29, 2023). "Task Force Recommends Repurposing the Current Library as a Community Center". Cape May County Herald. Rio Grande, New Jersey. Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ Miller, Ben (December 15, 2018). The First Resort: Fun, Sun, Fire & War in Cape May, America's Original Seaside Town. West Cape May, New Jersey: Exit Zero. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-9972662-2-1.

- ^ a b c Pocher, Don; Pocher, Pat (1998). Cape May in Vintage Postcards. Arcadia Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 9780738537757.

Since c. 1970, an Acme supermarket has occupied the site of Cape May's first high school, shown here.

- ^ a b Barlow, Bill (May 26, 2020). "Cape May group moves to get public safety building on the ballot". Press of Atlantic City. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ Miller, Ben (December 15, 2018). The First Resort: Fun, Sun, Fire & War in Cape May, America's Original Seaside Town. West Cape May, New Jersey: Exit Zero. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-9972662-2-1.

- ^ Salvatore, Joseph E.; Berkey, Joan (May 11, 2015). Cape May. Arcadia Publishing. p. 80. ISBN 9781439651285.

- ^ Flud, Tom (June 6, 2011). "Schmidtchen Called 'Father' Of LCMR". Cape May County Herald. Archived from the original on October 11, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

For the four southernmost Cape May County municipalities, [...] [which would be Cape May, Cape May Point, West Cape May, and Lower Township]

- ^ "Cape May County Schools". Diocese of Camden. July 28, 2009. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Ianeri, Brian (May 12, 2009). "Our Lady Star of the Sea school in Cape May to close in 2010". Press of Atlantic City. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ DiPasquale, Donna (June 22, 2010). "After 92 years, Star of the Sea School closes its doors". Cape Publishing, Inc. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020. - The author was the principal of Our Lady Star of the Sea Regional School.

- ^ Franklin, Chris (June 4, 2020). "2 Jersey Shore Catholic schools slated to close have been saved". Nj.com. NJ Advance Media. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Crowley, Terrence J. Cape May County Report on Consolidation and Regionalization, New Jersey Department of Education, March 15, 2010, available through the Asbury Park Press. Accessed August 30, 2014. "The school districts of Cape May City, West Cape May, and Cape May Point (non-operating) are currently conducting a feasibility study to merge the districts. A consultant is currently collecting and analyzing data and will be finalizing his report in late spring 2010."

- ^ Barlow, Bill (June 13, 2024). "Cape May launches new library with 'book brigade'". Press of Atlantic City. Atlantic City, New Jersey. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ Cape May County Mileage by Municipality and Jurisdiction[permanent dead link], New Jersey Department of Transportation, May 2010. Accessed July 18, 2014.

- ^ New Jersey Route 109 Straight Line Diagram Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Transportation, April 2015. Accessed May 26, 2016.

- ^ New Jersey State Transportation Map Archived June 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Transportation, 2012. Accessed May 26, 2016.

- ^ Cape May County Bus / Rail Connections, NJ Transit, backed up by the Internet Archive as of January 28, 2010. Accessed August 30, 2014.

- ^ South Jersey Transit Guide Archived 2018-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, Cross County Connection, as of April 1, 2010. Accessed August 30, 2014.

- ^ "Cape May Trolley Service". Great American Trolley Company. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ Degener, Richard. "Seashore Line resumes train service to Cape May as tourist attraction" Archived June 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Press of Atlantic City, August 18, 2010. Accessed May 26, 2016.

- ^ Rio Grande–Cape May Line Archived 2015-07-23 at the Wayback Machine, Cape May Seashore Lines. Accessed May 26, 2016.