Maya script

| Maya script | |

|---|---|

Pages 6, 7, and 8 of the Dresden Codex, showing letters numbers and the images that often accompany Maya writing | |

| Script type | Alternative

Used both logograms and syllabic characters |

Time period | 3rd century BCE to 16th century AD |

| Direction | Top-to-bottom |

| Languages | Mayan languages |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Maya (090), Mayan hieroglyphs |

| Unicode | |

| None (tentative range U+15500–U+159FF) | |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Maya civilization |

|---|

|

| History |

| Spanish conquest of the Maya |

|

|

The Mayan script, also known as Mayan glyphs or Mayan hieroglyphs, is the writing system of the Maya civilization of Mesoamerica, currently the only Mesoamerican writing system that has been substantially deciphered. The earliest inscriptions found, which are identifiably Maya, date to the 3rd century BCE in San Bartolo, Guatemala.[1][2] Maya writing was in continuous use throughout Mesoamerica until the Spanish conquest of the Maya in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Maya writing used logograms complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs, somewhat similar in function to modern Japanese writing. Mayan writing was called "hieroglyphics" or hieroglyphs by early European explorers of the 18th and 19th centuries who did not understand it but found its general appearance reminiscent of Egyptian hieroglyphs, to which the Mayan writing system is not at all related.

Modern Mayan languages are written using the Latin alphabet rather than Maya script.[3]

Languages

It is now thought that the codices and other Classic texts were written by scribes, usually members of the Maya priesthood, in a literary form of the Ch’olti’ language (known as Classic Maya).[4][5] It is possible that the Maya elite spoke this language as a lingua franca over the entire Maya-speaking area, but also that texts were written in other Mayan languages of the Petén and Yucatán, especially Yucatec. There is also some evidence that the script may have been occasionally used to write Mayan languages of the Guatemalan Highlands.[5] However, if other languages were written, they may have been written by Ch’olti’ scribes, and therefore have Ch’olti’ elements.

Structure

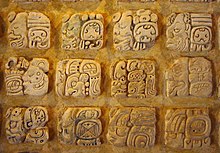

Mayan writing consisted of a relatively elaborate set of glyphs, which were laboriously painted on ceramics, walls or bark-paper codices, carved in wood or stone, or molded in stucco. Carved and molded glyphs were painted, but the paint has rarely survived. About 90% of Mayan writing can now be read with varying degrees of certainty, enough to give a comprehensive idea of its structure.[6]

There is evidence of literacy based on the use of the Mayan script.[7]

The Mayan script was a logosyllabic system. Individual symbols ("glyphs") could represent either a word (actually a morpheme) or a syllable; indeed, the same glyph could often be used for both. For example, the calendaric glyph MANIK’ was also used to represent the syllable chi. (It is customary to write logographic readings in all capitals and phonetic readings in italics.) It is possible, but not certain, that these conflicting readings arose as the script was adapted to new languages, as also happened with Japanese kanji and with Assyro-Babylonian and Hittite cuneiform. There was polyvalence in the other direction as well: different glyphs could be read the same way. For example, half a dozen apparently unrelated glyphs were used to write the very common third person pronoun u-.

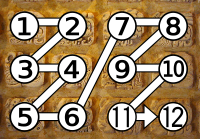

Mayan was usually written in blocks arranged in columns two blocks wide, read as follows:

Within each block, glyphs were arranged top-to-bottom and left-to-right, superficially rather like Korean Hangul syllabic blocks. However, in the case of Mayan, each block tended to correspond to a noun or verb phrase such as his green headband. Also, glyphs were sometimes conflated, where an element of one glyph would replace part of a second. Conflation occurs in other scripts: For example, in medieval Spanish manuscripts the word de 'of' was sometimes written Ð (a D with the arm of an E). Another example is the ampersand (&) which is a conflation of the Latin et. In place of the standard block configuration, Mayan was also sometimes written in a single row or column, 'L', or 'T' shapes. These variations most often appeared when they would better fit the surface being inscribed.

Mayan glyphs were fundamentally logographic. Generally the glyphs used as phonetic elements were originally logograms that stood for words that were themselves single syllables, syllables that either ended in a vowel or in a weak consonant such as y, w, h, or glottal stop. For example, the logogram for 'fish fin' (Maya [kah]—found in two forms, as a fish fin and as a fish with prominent fins), came to represent the syllable ka. These syllabic glyphs performed two primary functions: they were used as phonetic complements to disambiguate logograms which had more than one reading, as also occurred in Egyptian and in modern Japanese (i.e. furigana); and they were used to write grammatical elements such as verbal inflections which did not have dedicated logograms, also as in modern Japanese (i.e. okurigana). For example, b'alam 'jaguar' could be written as a single logogram, B'ALAM, complemented phonetically as ba-B'ALAM, or B'ALAM-ma, or b'a-B'ALAM-ma, or written completely phonetically as b'a-la-ma.

Harmonic and disharmonic echo vowels

Phonetic glyphs stood for simple consonant-vowel or bare-vowel syllables. However, Mayan phonotactics is slightly more complicated than this: Most Mayan words end in a consonant, not a vowel, and there may be sequences of two consonants within a word as well, as in xolte’ [ʃolteʔ] 'scepter', which is CVCCVC. When these final consonants were sonorants (l, m, n) or gutturals (j, h, ’) they were sometimes ignored ("underspelled"), but more often final consonants were written, which meant that an extra vowel was written as well. This was typically an "echo" vowel that repeated the vowel of the previous syllable. That is, the word [kah] 'fish fin' would be underspelled ka or written in full as ka-ha. However, there are many cases where some other vowel was used, and the orthographic rules for this are only partially understood; this is largely due to the difficulty in ascertaining whether this vowel may be due to an underspelled suffix. Lacadena and Wichmann (2004) proposed the following conventions:

- A CVC syllable was written CV-CV, where the two vowels (V) were the same: yo-po [yop] 'leaf'

- A syllable with a long vowel (CVVC) was written CV-Ci, unless the long vowel was [i], in which case it was written CiCa: ba-ki [baak] 'captive', yi-tzi-na [yihtziin] 'younger brother'

- A syllable with a glottalized vowel (CV’C or CV’VC) was written with a final a if the vowel was [e, o, u], or with a final u if the vowel was [a] or [i]: hu-na [hu’n] 'paper', ba-tz’u [ba’ts’] 'howler monkey'.

- Preconsonantal [h] is not indicated.

That is, a simple vowel is intended if the vowels are the same (harmonic), and either two syllables are intended (likely underspelled) if the vowels are not the same (disharmonic), or else a single syllable with a long vowel (if V1 = [a e? o u] and V2 = [i], or else if V1 = [i] and V2 = [a]) or with a glottalized vowel (if V1 = [e? o u] and V2 = [a], or else if V1 = [a i] and V2 = [u]). The long-vowel reading of [Ce-Ci] is still uncertain, and there is a possibility that [Ce-Cu] represents a glottalized vowel (if it is not simply an underspelling for [CeCuC]), so it may be that the disharmonies form natural classes: [i] for long non-front vowels, otherwise [a] to keep it disharmonic; [u] for glottalized non-back vowels, otherwise [a].

A more complex spelling is ha-o-bo ko-ko-no-ma for [ha’o’b kohkno’m] 'they are the guardians'. (Vowel length and glottalization are not always indicated in common words like 'they are'.) A minimal set is,

- ba-ka [bak]

- ba-ki [baak]

- ba-ku [ba’k] = [ba’ak]

- ba-ke [baakel] (underspelled)

- ba-ke-le [baakel]

Verbal inflections

Despite depending on consonants which were frequently not written, the Mayan voice system was reliably indicated. For instance, the paradigm for a transitive verb with a CVC root is as follows:

| Voice | Transliteration | Transcription | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active | u-TZUTZ-wa | utzutzu’w | "s/he finished it" |

| Passive | TZUTZ-tza-ja | tzu⟨h⟩tzaj | "it was finished" |

| Mediopassive | TZUTZ-yi | tzutzuuy | "it got finished" |

| Antipassive | TZUTZ-wi | tzutzuuw | "s/he finished" |

| Participial | TZUTZ-li | tzutzuul | "finished" |

The active suffix did not participate in the harmonic/disharmonic system seen in roots, but rather was always -wa.

However, the language changed over 1500 years, and there were dialectical differences as well, which are reflected in the script, as seen next for the verb "s/he sat" (⟨h⟩ is an infix in the root chum for the passive voice):

| Period | Transliteration | Transcription |

|---|---|---|

| Late Preclassic | CHUM? | chu⟨h⟩m? |

| Early Classic | CHUM-ja | chu⟨h⟩m-aj |

| Classic (Eastern Ch'olan) | CHUM-mu-la-ja | chum-l-aj |

| Late Classic (Western Ch'olan) | CHUM-mu-wa-ni | chum-waan |

Emblem glyphs

An "emblem glyph" is a kind of royal title. It consists of a word ajaw—a Classic Maya term for "lord" of yet unclear etymology but well-attested in Colonial sources[8]—and a place name that precedes the word ajaw and functions as an adjective. An expression "Boston lord" would be a perfect English analogy. Sometimes, the title is introduced by an adjective k’uhul ("holy, divine" or "sacred"), just as if someone wanted to say "holy Boston lord". Of course, an "emblem glyph" is not a "glyph" at all: it can be spelled with any number of syllabic or logographic signs and several alternative spellings are attested for the words k’uhul and ajaw, which form the stable core of the title. The term "emblem glyph" simply reflects the times when Mayanists could not read Classic Maya inscriptions and had to come up with some nicknames isolating certain recurrent structural components of the written narratives.

This title was identified in 1958 by Heinrich Berlin,[9] who coined the term "emblem glyph". Berlin noticed that the "emblem glyphs" consisted of a larger "main sign" and two smaller signs now read as k’uhul ajaw. Berlin also noticed that while the smaller elements remained relatively constant, the main sign changed from site to site. Berlin proposed that the main signs identified individual cities, their ruling dynasties, or the territories they controlled. Subsequently, Marcus[10] argued that the "emblem glyphs" referred to archaeological sites, broken down in a 5-tiered hierarchy of asymmetrical distribution. Marcus' research assumed that the emblem glyphs were distributed in a pattern of relative site importance depending on broadness of distribution, roughly broken down as follows: Primary regional centers (capitals) (Tikal, Calakmul, and other "superpowers") were generally first in the region to acquire a unique emblem glyph(s). Texts referring to other primary regional centers occur in the texts of these "capitals", and dependencies exist which use the primary center's glyph. Secondary centers (Altun Ha, Luubantuun, Xunantunich, and other mid-sized cities had their own glyphs but are only rarely mentioned in texts found in the primary regional center, while repeatedly mentioning the regional center in their own texts. Tertiary centers (towns) had no glyphs of their own, but have texts mentioning the primary regional centers and perhaps secondary regional centers on occasion. These were followed by the villages with no emblem glyphs and no texts mentioning the larger centers, and hamlets with little evidence of texts at all.[11] This model was largely unchallenged for over a decade until Mathews and Justeson,[12] as well as Houston[13] argued once again that the "emblem glyphs" were the titles of Maya rulers with some geographical association.

The debate on the nature of "emblem glyphs" received a new spin with the monograph by Stuart and Houston.[14] The authors convincingly demonstrated that there were lots of place names-proper, some real, some mythological, mentioned in the hieroglyphic inscriptions. Some of these place names also appeared in the "emblem glyphs", some were attested in the "titles of origin" (various expressions like "a person from Boston"), but some were not incorporated in personal titles at all. Moreover, the authors also highlighted the cases when the "titles of origin" and the "emblem glyphs" did not overlap, building upon an earlier research by Houston.[15] Houston noticed that the establishment and spread of the Tikal-originated dynasty in the Petexbatun region was accompanied by the proliferation of rulers using the Tikal "emblem glyph" placing political and dynastic ascendancy above the current seats of rulership.[16] Recent investigations also emphasize the use of emblem glyphs as an emic identifier to shape socio-political self-identity.[17]

Numerical system

The Mayas used a positional base-twenty (vigesimal) numerical system which only included whole numbers. For simple counting operations, a bar and dot notation was used. The dot represents 1 and the bar represents 5. A shell was used to represent zero. Numbers from 6 to 19 are formed combining bars and dots. Numbers can be written horizontally or vertically.

The value of a number depends on its position going from the bottom line upward in the configuration. The initial position -to wit, bottom line- has the value represented in the symbol. On the following line, the value of the symbol is multiplied by 20; on the third line from the bottom it's multiplied by 400, and each successive line is growing by powers of 20. That is to say, Mayan numerals use base 20. This positional system allows the calculation of large figures, necessary for chronology and astronomy.[18]

History

It was until recently thought that the Maya may have adopted writing from the Olmec or Epi-Olmec culture, who used the Isthmian script. However, murals excavated in 2005 have pushed back the origin of Maya writing by several centuries, and it now seems possible that the Maya were the ones who invented writing in Mesoamerica.[19] Regardless, it is generally believed that the Maya developed the only complete writing system in Mesoamerica, meaning that they were the only civilization that could write everything they could say.

Knowledge of the Maya writing system continued into the early colonial era and reportedly a few of the early Spanish priests who went to Yucatán learned it. However, as part of his campaign to eradicate pagan rites, Bishop Diego de Landa ordered the collection and destruction of written Maya works, and a sizable number of Maya codices were destroyed. Later, seeking to use their native language to convert the Maya to Christianity, he derived what he believed to be a Maya "alphabet" (the so-called de Landa alphabet). Although the Maya did not actually write alphabetically, nevertheless he recorded a glossary of Maya sounds and related symbols, which was long dismissed as nonsense but eventually became a key resource in deciphering the Maya script, though it has itself not been completely deciphered. The difficulty was that there was no simple correspondence between the two systems, and the names of the letters of the Spanish alphabet meant nothing to Landa's Maya scribe, so Landa ended up asking the equivalent of write H: a-i-tee-cee-aitch "aitch", and glossed a part of the result as "H".

Landa was also involved in creating a Latin orthography for the Yukatek Maya language, meaning that he created a system for writing Yukatek in the Latin alphabet. This was the first Latin orthography for any of the Mayan languages,[citation needed] which number around thirty.

Only four Maya codices are known to have survived the conquistadors.[20] Most surviving texts are found on pottery recovered from Maya tombs, or from monuments and stelae erected in sites which were abandoned or buried before the arrival of the Spanish.

Knowledge of the writing system was lost, probably by the end of the 16th century. Renewed interest in it was sparked by published accounts of ruined Maya sites in the 19th century.[20]

Decipherment

The decipherment of the writing was a long and laborious process. 19th-century and early 20th-century investigators managed to decode the Maya numbers[21] and portions of the texts related to astronomy and the Maya calendar, but understanding of most of the rest long eluded scholars. In the 1930s, Benjamin Whorf wrote a number of published and unpublished essays, proposing to identify phonetic elements within the writing system. Although some specifics of his decipherment claims were later shown to be incorrect, the central argument of his work, that Maya hieroglyphs were phonetic (or more specifically, syllabic), was later supported by the work of Yuri Knorozov, who played a major role in deciphering Maya writing.[22] In 1952, Knorozov published the paper "Ancient Writing of Central America" arguing that the so-called "de Landa alphabet" contained in Bishop Diego de Landa's manuscript Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán was made of syllabic, rather than alphabetic symbols. He further improved his decipherment technique in his 1963 monograph "The Writing of the Maya Indians"[23] and published translations of Maya manuscripts in his 1975 work "Maya Hieroglyphic Manuscripts". In the 1960s, progress revealed the dynastic records of Maya rulers. Since the early 1980s it has been demonstrated that most of the previously unknown symbols form a syllabary, and progress in reading the Maya writing has advanced rapidly since.

As Knorozov's early essays contained several older readings already published in the late 19th century by Cyrus Thomas,[24] and the Soviet editors added propagandistic claims[25] to the effect that Knorozov was using a peculiarly "Marxist-Leninist" approach to decipherment,[25] many Western Mayanists simply dismissed Knorozov's work. However, in the 1960s more came to see the syllabic approach as potentially fruitful, and possible phonetic readings for symbols whose general meaning was understood from context began to be developed. Prominent older epigrapher J. Eric S. Thompson was one of the last major opponents of Knorozov and the syllabic approach. Thompson's disagreements are sometimes said to have held back advances in decipherment.[26] For example, Coe (1992) says[27] "the major reason was that almost the entire Mayanist field was in willing thrall to one very dominant scholar, Eric Thompson". Ershova, student of Knorozov, also stated, that reception of Knorozov work was delayed only by authority of Thompson, and thus has nothing to do with Marxism.

In 1959, examining what she called "a peculiar pattern of dates" on stone monument inscriptions at the Classic Maya site of Piedras Negras, Russian-American scholar Tatiana Proskouriakoff determined that these represented events in the lifespan of an individual, rather than relating to religion, astronomy, or prophecy, as held by the "old school" exemplified by Thompson. This proved to be true of many Maya inscriptions, and revealed the Maya epigraphic record to be one relating actual histories of ruling individuals: dynastic histories similar in nature to those recorded in literate human cultures throughout the world. Suddenly, the Maya entered written history.[28]

Although it was then clear what was on many Maya inscriptions, they still could not literally be read. However, further progress was made during the 1960s and 1970s, using a multitude of approaches including pattern analysis, de Landa's "alphabet", Knorozov's breakthroughs, and others. In the story of Maya decipherment, the work of archaeologists, art historians, epigraphers, linguists, and anthropologists cannot be separated. All contributed to a process that was truly and essentially multidisciplinary. Key figures included David Kelley, Ian Graham, Gilette Griffin, and Michael Coe.

Dramatic breakthroughs occurred in the 1970s, in particular at the first Mesa Redonda de Palenque, a scholarly conference organized by Merle Greene Robertson at the Classic Maya site of Palenque held in December, 1973. A working group was led by Linda Schele, an art historian and epigrapher at the University of Texas at Austin, which included Floyd Lounsbury, a linguist from Yale, and Peter Mathews, then an undergraduate student of David Kelley's at the University of Calgary (whom Kelley sent because he could not attend). In one afternoon they managed to decipher the first dynastic list of Maya kings, the ancient kings of the city of Palenque. By identifying a sign as an important royal title (now read as the recurring name K'inich), the group was able to identify and "read" the life histories (from birth, to accession to the throne, to death) of six kings of Palenque.

From that point, progress proceeded at an exponential pace,[clarification needed] not only in the decipherment of the Maya glyphs, but also towards the construction of a new, historically based understanding of Maya civilization. Scholars such as J. Kathryn Josserand, Nick Hopkins and others published findings that helped to construct a Mayan vocabulary.[29] In 1988, Wolfgang Gockel published a translation of the Palenque inscriptions based on a morphemic rather than syllabic interpretation of the glyphs. The "old school" continued to resist the results of the new scholarship for some time. A decisive event which helped to turn the tide in favor of the new approach occurred in 1986, at an exhibition entitled "The Blood of Kings: A New Interpretation of Maya Art". It was organized by InterCultura and the Kimbell Art Museum and curated by Schele and Yale art historian Mary Miller. This exhibition and attendant catalogue—and international publicity—revealed to a wide audience the new world which had latterly been opened up by progress in decipherment of Maya hieroglyphics. Not only could a real history of ancient America now be read and understood, but the light it shed on the material remains of the Maya showed them to be real, recognisable individuals. They stood revealed as a people with a history like that of all other human societies: full of wars, dynastic struggles, shifting political alliances, complex religious and artistic systems, expressions of personal property and ownership and the like. Moreover, the new interpretation, as the exhibition demonstrated, made sense out of many works of art whose meaning had been unclear and showed how the material culture of the Maya represented a fully integrated cultural system and world view. Gone was the old Thompson view of the Maya as peaceable astronomers without conflict or other attributes characteristic of most human societies.

However, three years later in 1989, a final counter-assault was launched by supporters who were still resisting the modern decipherment interpretation. This occurred at a conference at Dumbarton Oaks. It did not directly attack the methodology or results of decipherment, but instead contended that the ancient Maya texts had indeed been read but were "epiphenomenal". This argument was extended from a populist perspective to say that the deciphered texts tell only about the concerns and beliefs of the society's elite, and not about the ordinary Maya. Michael Coe in opposition to this idea described "epiphenomenal" as "a ten penny word meaning that Maya writing is only of marginal application since it is secondary to those more primary institutions—economics and society—so well studied by the dirt archaeologists."[30]

Linda Schele noted following the conference that this is like saying that the inscriptions of ancient Egypt—or the writings of Greek philosophers or historians—do not reveal anything important about their cultures. Most written documents in most cultures tell us about the elite, because in most cultures in the past, they were the ones who could write (or could have things written down by scribes or inscribed on monuments).[citation needed]

Progress in decipherment continues at a rapid pace today, and it is generally agreed by scholars that over 90 percent of the Maya texts can now be read with reasonable accuracy.[3] As of 2008[update], at least one phonetic glyph was known (or had been proposed) for each of the syllables marked in this chart other than [p’] for which no syllable is attested. Based on verbal inflection patterns, it would seem that a syllabogram for [wu] did not exist rather than simply being unattested.[31]

| (’) | b | ch | ch’ | h | j | k | k’ | l | m | n | p | p’ | s | t | t’ | tz | tz’ | w | x | y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| e | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||

| i | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |||

| o | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| u | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

Computer encoding

Currently Maya script cannot be represented in any computer character encoding. A range of codepoints (U+15500–U+159FF) has been tentatively allocated for Unicode, but no detailed proposal has been submitted yet.[32]

Notes

- ^ K. Kris Hirst (6 January 2006). "Maya Writing Got Early Start". Science.

- ^ "Symbols on the Wall Push Maya Writing Back by Years". The New York Times. 2006-01-10. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ a b Lebrun, David (Director) Guthrie, Rosey (producer) (2008). Breaking the Maya Code (Documentary). Night Fire Films. ASIN B001B2U1BE.

- ^ Houston, Stephen D.; Robertson, John; Stuart, David (2000). "The Language of Classic Maya Inscriptions". Current Anthropology. 41 (3): 321–356. doi:10.1086/300142. ISSN 0011-3204. PMID 10768879.

- ^ a b Kettunen and Helmke (2005, p.12)

- ^ See here for a more substantial discussion and, from page 70 on, a partial list of glyphs and glyph blocks

- ^ Tedlock, Dennis (1992). "On Hieroglyphic Literacy in Ancient Mayaland: An Alternative Interpretation". Current Anthropology. 33 (2).

- ^ Lacadena García-Gallo, A. and A. Ciudad Ruiz (1998). Reflexiones sobre la estructura política maya clásica. Anatomía de una Civilización: Aproximaciones Interdisciplinarias a la Cultura Maya. A. Cuidad Ruiz, M. I. Ponce de León and M. Martínez Martínez. Madrid, Sociedad Española de Estudios Mayas: 31–64

- ^ Berlin, H. (1958). "El Glifo Emblema en las inscripciones Maya." Journal de la Société des Américanistes de Paris 47: 111–119

- ^ Marcus, J. (1976). Emblem and state in the classic Maya Lowlands: an epigraphic approach to territorial organization. Washington, Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University

- ^ Marcus, J. (1973) Territorial Organization of the Lowland Classic Maya. Science. 1973 June 1;180 (4089):pp. 911–916

- ^ See Mathews (1991)

- ^ Houston, S. D. (1986). Problematic emblem glyphs: examples from Altar de Sacrificios, El Chorro, Río Azul, and Xultun. Washington, D.C., Center for Maya Research

- ^ Stuart, D. and S. D. Houston (1994). Classic Maya place names. Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

- ^ Houston (1993; in particular, pp.97–101)

- ^ Source: A.Tokovinine(2006) People from a place: re-interpreting Classic Maya "Emblem Glyphs". Paper presented at the 11th European Maya Conference "Ecology, Power, and Religion in Maya Landscapes", Malmö University, Sweden, December 4–9, 2006

- ^ S. Gronemeyer (2012) Maya Political Relations and Strategies. Proceedings of the 14th European Maya Conference, Cracow, 2009 [Contributions in New World Archaeology, 4], edited by Jarosław Źrałka, Wiesław Koszkul and Beata Golińska: 13–40. Cracow: Polska Akademia Umiejętności and Uniwersytet Jagielloński

- ^ Information panel in the Museo Regional de Antropología in Mérida (state of Yucatán), visited on 2010-08-04

- ^ Saturno, William A.; David Stuart; Boris Beltrán (3 March 2006). "Early Maya Writing at San Bartolo, Guatemala". Science. 311 (5765): 1281–1283. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1281S. doi:10.1126/science.1121745. PMID 16400112.

- ^ a b McKillop, Heather (2004). The ancient Maya : new perspectives. New York, N.Y.: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-393-32890-5.

- ^ Constantine Rafinesque (1832) "Philology. Second letter to Mr. Champollion on the graphic systems of America, and the glyphs of Otolum or Palenque, in Central America – Elements of the glyphs," Atlantic Journal and Friend of Knowledge, 1 (2) : 40–44. From p. 42: "This page of Demotic has letters and numbers, these represented by strokes meaning 5 and dots meaning unities as the dots never exceed 4."

- ^ Yuri Knorozov at Britannica

- ^ Template:Ru iconYuri Knorozov

- ^ Coe, M. (1992), pp. 151

- ^ a b Coe, M. (1992), pp. 147

- ^ Coe, M. (1992), pp. 125–144

- ^ Coe, M. (1992), pp. 164

- ^ Coe, M. (1992), pp. 167–184

- ^ "JosserandHopkinsTRANSCRIPT.pdf" (PDF). google.com. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Coe, M. (1992), p. 268 (3rd ed)

- ^ Kettunen & Helmke (2008) pp 48–49

- ^ The Unicode Consortium, Roadmap to the SMP

Bibliography

- Coe, Michael D. (1992). Breaking the Maya Code. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05061-9.

- Michael D. Coe (1993). Breaking the Maya Code (illustrated, reprint ed.). Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0500277214. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- Coe, Michael D.; Mark L Van Stone (2005). Reading the Maya Glyphs. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28553-4.

- Gronemeyer, Sven (2012). "Statements of Identity: Emblem Glyphs in the Nexus of Political Relations". In Jarosław Źrałka, Wiesław Koszkul and Beata Golińska (eds.) (ed.). Maya Political Relations and Strategies. Proceedings of the 14th European Maya Conference, Cracow, 2009. Contributions in New World Archaeology. Vol. 4. Cracow: Polska Akademia Umiejętności and Uniwersytet Jagielloński. pp. 13–40.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Houston, Stephen D. (1986). Problematic Emblem Glyphs: Examples from Altar de Sacrificios, El Chorro, Rio Azul, and Xultun (PDF). Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing, 3. (Mesoweb online facsimile ed.). Washington D.C: Center for Maya Research. ASIN B0006EOYNY.

- Houston, Stephen D. (1993). Hieroglyphs and History at Dos Pilas: Dynastic Politics of the Classic Maya. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-73855-2.

- Kettunen, Harri; Christophe Helmke (2010). Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs (PDF). Wayeb and Leiden University. Retrieved 2013-01-31.

- Lacadena García-Gallo, Alfonso; Andrés Ciudad Ruiz (1998). "Reflexiones sobre la estructura política maya clásica". In Andrés Ciudad Ruiz, Yolanda Fernández Marquínez, José Miguel García Campillo, Maria Josefa Iglesias Ponce de León, Alfonso Lacadena García-Gallo, Luis T. Sanz Castro (eds.) (ed.). Anatomía de una Civilización: Aproximaciones Interdisciplinarias a la Cultura Maya. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Estudios Mayas. ISBN 84-923545-0-X.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) Template:Es icon - Lebrun, David (Director) Guthrie, Rosey (producer) (2008). Breaking the Maya Code (Documentary). Night Fire Films. ASIN B001B2U1BE.

- Marcus, Joyce (1976). Emblem and State in the Classic Maya Lowlands: an Epigraphic Approach to Territorial Organization. Dumbarton Oaks Other Titles in Pre-Columbian Studies. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-88402-066-5.

- Mathews, Peter (1991). "Classic Maya emblem glyphs". In T. Patrick Culvert (ed.) (ed.). Classic Maya Political History: Hieroglyphic and Archaeological Evidence. School of American Research Advanced Seminars. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–29. ISBN 0-521-39210-1.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Montgomery, John (2002). Dictionary of Maya Hieroglyphs. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-0862-0.

- Montgomery, John (2004). How to Read Maya Hieroglyphs (Hippocrene Practical Dictionaries). New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-1020-3.

- Saturno, William A. (3 March 2006). "Early Maya writing at San Bartolo, Guatemala" (PDF Science Express republ.). Science. 311 (5765): 1281–3. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1281S. doi:10.1126/science.1121745. PMID 16400112. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Schele, Linda; David Freidel (1990). A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0-688-07456-1.

- Schele, Linda; Mary Ellen Miller (1992) [1986]. Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. Justin Kerr (photographer) (reprint ed.). New York: George Braziller. ISBN 0-8076-1278-2.

- Soustelle, Jacques (1984). The Olmecs: The Oldest Civilization in Mexico. New York: Doubleday and Co. ISBN 0-385-17249-4.

- Stuart, David; Stephen D. Houston (1994). Classic Maya Place Names. Dumbarton Oaks Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology Series, 33. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-88402-209-9.

- Tedlock, Dennis (2010). 2000 Years of Mayan Literature. California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23221-1.

- Van Stone, Mark L (2010). 2012: Science and Prophecy of the Ancient Maya. California: Tlacaelel Press. ISBN 978-0-9826826-0-9.

External links

![]() Media related to Maya writing at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Maya writing at Wikimedia Commons

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (June 2015) |

- Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs by Harri Kettunen and Christophe Helmke

- A partial transcription, transliteration, and translation of the Temple of Inscriptions text by Michael D. Carrasco

- A Preliminary Classic Maya-English/English-Classic Maya Vocabulary of Hieroglyphic Readings by Eric Boot

- FAMSI resources on Maya Hieroglyphic writing

- Maya Writing in: Guatemala, Cradle of the Maya Civilization

- Mayaweb: Learn how to write your name in Maya Hieroglyphs

- Nova online – 'Cracking the Maya Code'

- Wolfgang Gockel's morphemic interpretation of the glyphs

- Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Program at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University

- Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Volumes 1–9. Published by the Peabody Museum Press and distributed by Harvard University Press

- Talakh Viktor (2011-03-19). "Introduction to hieroglyphic script of the Maya. Manual" (PDF). www.bloknot.info. Retrieved 2011-03-24.